Foreign Relations of the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The diplomatic foreign relations of the United Kingdom are conducted by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, headed by the

The diplomatic foreign relations of the United Kingdom are conducted by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, headed by the

Following the formation of the

Following the formation of the

The 100 years were generally peaceful--a sort of

The 100 years were generally peaceful--a sort of

Vivid memories of the horrors and deaths of the First World War inclined many Britons—and their leaders in all parties—to pacifism in the interwar era. This led directly to the

Vivid memories of the horrors and deaths of the First World War inclined many Britons—and their leaders in all parties—to pacifism in the interwar era. This led directly to the

Economically in dire straits in 1945 (saddled with debt and dealing with widespread destruction of its infrastructure), Britain systematically reduced its overseas commitments. It pursued an alternate role as an active participant in the

Economically in dire straits in 1945 (saddled with debt and dealing with widespread destruction of its infrastructure), Britain systematically reduced its overseas commitments. It pursued an alternate role as an active participant in the

Foreign policy initiatives of UK governments since the 1990s have included military intervention in conflicts and for peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance programmes and increased aid spending, support for establishment of the

Foreign policy initiatives of UK governments since the 1990s have included military intervention in conflicts and for peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance programmes and increased aid spending, support for establishment of the

* 1972–1973 –

* 1972–1973 –

* Spain claims the British overseas territory of

* Spain claims the British overseas territory of

The UK has varied relationships with the countries that make up the Commonwealth of Nations which originated from the

The UK has varied relationships with the countries that make up the Commonwealth of Nations which originated from the

excerpt and text search

* Daddow, Oliver, and Jamie Gaskarth, eds. ''British foreign policy: the New Labour years'' (Palgrave, 2011) * Daddow, Oliver. "Constructing a ‘great’ role for Britain in an age of austerity: Interpreting coalition foreign policy, 2010–2015." ''International Relations'' 29.3 (2015): 303-318. * Dickie, John. ''The New Mandarins: How British Foreign Policy Works'' (2004) * Dumbrell, John. ''A special relationship: Anglo-American relations from the Cold War to Iraq'' (2006) * Finlan, Alastair. ''Contemporary Military Strategy and the Global War on Terror: US and UK Armed Forces in Afghanistan and Iraq 2001-2012'' (2014) * Honeyman, V. C. "From Liberal Interventionism to Liberal Conservatism: the short road in foreign policy from Blair to Cameron." ''British Politics'' (2015)

abstract

* Lane, Ann. ''Strategy, Diplomacy and UK Foreign Policy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) * Leech, Philip, and Jamie Gaskarth. "British Foreign Policy and the Arab Spring." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 26#1 (2015). * Lunn, Jon, Vaughne Miller, Ben Smith. "British foreign policy since 1997 - Commons Library Research Paper RP08/56" (UK House of Commons, 2008) 123p

online

* Magyarics, Tamas

Balancing in Central Europe: Great Britain and Hungary in the 1920s

* Seah, Daniel. "The CFSP as an aspect of conducting foreign relations by the United Kingdom: With Special Reference to the Treaty of Amity & Cooperation in Southeast Asia]" ''International Review of Law'' (2015)

online

* Robert William Seton-Watson, Seton-Watson, R. W. ''Britain in Europe (1789–1914): A Survey of Foreign Policy'' (1937)

online

* Stephens, Philip. '' Britain Alone: The Path from Suez to Brexit'' (2021

excerpted

* Whitman, Richard G. "The calm after the storm? Foreign and security policy from Blair to Brown." ''Parliamentary Affairs'' 63.4 (2010): 834–848.

online

* Williams, Paul. ''British Foreign Policy under New Labour'' (2005)

Foreign and Commonwealth OfficeDepartment for International Development

{{DEFAULTSORT:Foreign Relations Of The United Kingdom

Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

. The prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

and numerous other agencies play a role in setting policy, and many institutions and businesses have a voice and a role.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

was the world's foremost power during the 19th and early 20th centuries, most notably during the so-called "Pax Britannica

''Pax Britannica'' (Latin for "British Peace", modelled after '' Pax Romana'') was the period of relative peace between the great powers during which the British Empire became the global hegemonic power and adopted the role of a "global poli ...

"a period of totally unrivaled supremacy and unprecedented international peace during the mid-to-late 1800s. The country continued to be widely considered a superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural ...

until the Suez crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of 1956, and this embarrassing incident coupled with the loss of the empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

left the UK's dominant role in global affairs to be gradually diminished. Nevertheless, the United Kingdom remains a great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

and a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

, a founding member of the G7, G8, G20, NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

, AUKUS, OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate ...

, WTO, Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a p ...

, OSCE, and the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

, the latter being a legacy of the British Empire. The UK had been a member state of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

(and a member of its predecessors) since 1973. However, due to the outcome of a 2016 membership referendum, proceedings to withdraw from the EU began in 2017 and concluded when the UK formally left the EU on 31 January 2020, and the transition period

The Brexit withdrawal agreement, officially titled Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, is a treaty between the European Uni ...

on 31 December 2020 with an EU trade agreement. Since the vote and the conclusion of trade talks with the EU, policymakers have begun pursuing new trade agreements with other global partners.

History

Following the formation of the

Following the formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

(which united England and Scotland) in 1707, British foreign relations largely continued those of the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

. British foreign policy initially focused on achieving a balance of power within Europe, with no one country achieving dominance over the affairs of the continent. This policy remained a major justification for Britain's wars against Napoleon, and for British involvement in the First and Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

s. Secondly Britain continued the expansion of its colonial "First British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts ...

" by migration and investment.

France was the chief enemy until the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. It had a much larger population and a more powerful army, but a weaker navy. The British were generally successful in their many wars. The notable exception, the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783), saw Britain, without any major allies, defeated by the American colonials who had the support of France, the Netherlands and (indirectly) Spain. A favoured British diplomatic strategy involved subsidising the armies of continental allies (such as Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

), thereby turning London's enormous financial power to military advantage. Britain relied heavily on its Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

for security, seeking to keep it the most powerful fleet afloat, eventually with a full complement of bases across the globe. British dominance of the seas was vital to the formation and maintaining of the British Empire, which was achieved through the support of a navy larger than the next two largest navies combined, prior to 1920. The British generally stood alone until the early 20th century, when it became friendly with the U.S. and made alliances with Japan, France and Russia. Germany was now the main antagonist.

1814–1914

The 100 years were generally peaceful--a sort of

The 100 years were generally peaceful--a sort of Pax Britannica

''Pax Britannica'' (Latin for "British Peace", modelled after '' Pax Romana'') was the period of relative peace between the great powers during which the British Empire became the global hegemonic power and adopted the role of a "global poli ...

enforced by the Royal Navy. There were two important wars, both limited in scope. The Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

(1853–1856) saw the defeat of Russia and its threat to the Ottoman Empire. The Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

(1899–1902) saw the defeat of the two Boer republics in South Africa. London became the world's financial centre

A financial centre ( BE), financial center ( AE), or financial hub, is a location with a concentration of participants in banking, asset management, insurance or financial markets with venues and supporting services for these activities to ta ...

, and commercial enterprise expanded across the globe. The "Second British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts ...

" was built with a base in Asia (especially India) and Africa.

First World War

1920s

After 1918 Britain was a "troubled giant" that was less of a dominant diplomatic force in the 1920s than before. It often had to give way to the United States, which frequently exercised its financial superiority. The main themes of British foreign policy included a leading role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920, whereLloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

worked hard to moderate French demands for revenge on Germany. He was partly successful, but Britain soon had to moderate French policy toward Germany further, as in the Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, during 5 to 16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central a ...

of 1925. Furthermore, Britain obtained "mandates" that allowed it and its dominions to govern most of the former German and Ottoman colonies.

Britain became an active member of the new League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, but its list of major achievements was slight.

Disarmament was high on the agenda, and Britain played a major role following the United States in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921 in working toward naval disarmament of the major powers. By 1933 disarmament agreements had collapsed and the issue became rearming for a war against Germany.

Britain was partially successful in negotiating better terms with United States regarding the large war loans which Britain was obliged to repay. Britain supported the American solution to German reparations through the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan. Thereby, Germany paid its annual reparations using money borrowed from New York banks, and Britain used the money received to pay Washington. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

starting in 1929 put enormous pressure on the British economy. Britain revived Imperial Preference

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the members of the Commonwealth of ...

, which meant low tariffs within the British Empire and higher barriers to trade with outside countries. The flow of money from New York dried up, and the system of reparations and payment of debt died in 1931.

In domestic British politics, the emerging Labour Party had a distinctive and suspicious foreign policy based on pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace camp ...

. Its leaders believed that peace was impossible because of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

, secret diplomacy, and the trade in armaments. Labour stressed material factors that ignored the psychological memories of the Great War and the highly emotional tensions regarding nationalism and the boundaries of countries. Nevertheless, party leader

In a governmental system, a party leader acts as the official representative of their political party, either to a legislature or to the electorate. Depending on the country, the individual colloquially referred to as the "leader" of a political ...

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

devoted much of his attention to European policies.

1930s

Vivid memories of the horrors and deaths of the First World War inclined many Britons—and their leaders in all parties—to pacifism in the interwar era. This led directly to the

Vivid memories of the horrors and deaths of the First World War inclined many Britons—and their leaders in all parties—to pacifism in the interwar era. This led directly to the appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

of dictators (notably of Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until Fall of the Fascist re ...

and of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

) in order to avoid their threats of war.

The challenge came from those dictators, first from Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, Duce of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, then from Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, Führer

( ; , spelled or ''Fuhrer'' when the umlaut is not available) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler.

Nazi Germany cultivated the ("leader princip ...

of a much more powerful Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. The League of Nations proved disappointing to its supporters; it failed to resolve any of the threats posed by the dictators. British policy involved "appeasing" them in the hopes they would be satiated. By 1938 it was clear that war was looming, and that Germany had the world's most powerful military. The final act of appeasement came when Britain and France sacrificed Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

to Hitler's demands at the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

of September 1938. Instead of satiation, Hitler menaced Poland, and at last Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

dropped appeasement and stood firm in promising to defend Poland (31 March 1939). Hitler however cut a deal with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

to divide Eastern Europe (23 August 1939); when Germany did invade Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war, and the British Commonwealth followed London's lead.

Second World War

Having signed the Anglo-Polish military alliance in August 1939, Britain and France declared war against Germany in September 1939 in response to Germany's invasion of Poland. This declaration included theCrown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Council ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, which Britain directly controlled. The dominions were independent in foreign policy, though all quickly entered the war against Germany. After the French defeat in June 1940, Britain and its empire stood alone in combat against Germany, until June 1941. The United States gave diplomatic, financial and material support, starting in 1940, especially through Lend Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

, which began in 1941 and attain full strength during 1943. In August 1941, Churchill and Roosevelt met and agreed on the Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

, which proclaimed "the rights of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live" should be respected. This wording was ambiguous and would be interpreted differently by the British, Americans, and nationalist movements.

Starting in December 1941, Japan overran British possessions in Asia, including Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

, Malaya, and especially the key base at Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

. Japan then marched into Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

, headed toward India. Churchill's reaction to the entry of the United States into the war was that Britain was now assured of victory and the future of the empire was safe, but the rapid defeats irreversibly harmed Britain's standing and prestige as an imperial power. The realisation that Britain could not defend them pushed Australia and New Zealand into permanent close ties with the United States.

Postwar

Economically in dire straits in 1945 (saddled with debt and dealing with widespread destruction of its infrastructure), Britain systematically reduced its overseas commitments. It pursued an alternate role as an active participant in the

Economically in dire straits in 1945 (saddled with debt and dealing with widespread destruction of its infrastructure), Britain systematically reduced its overseas commitments. It pursued an alternate role as an active participant in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

against communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

, especially as a founding member of NATO in 1949.

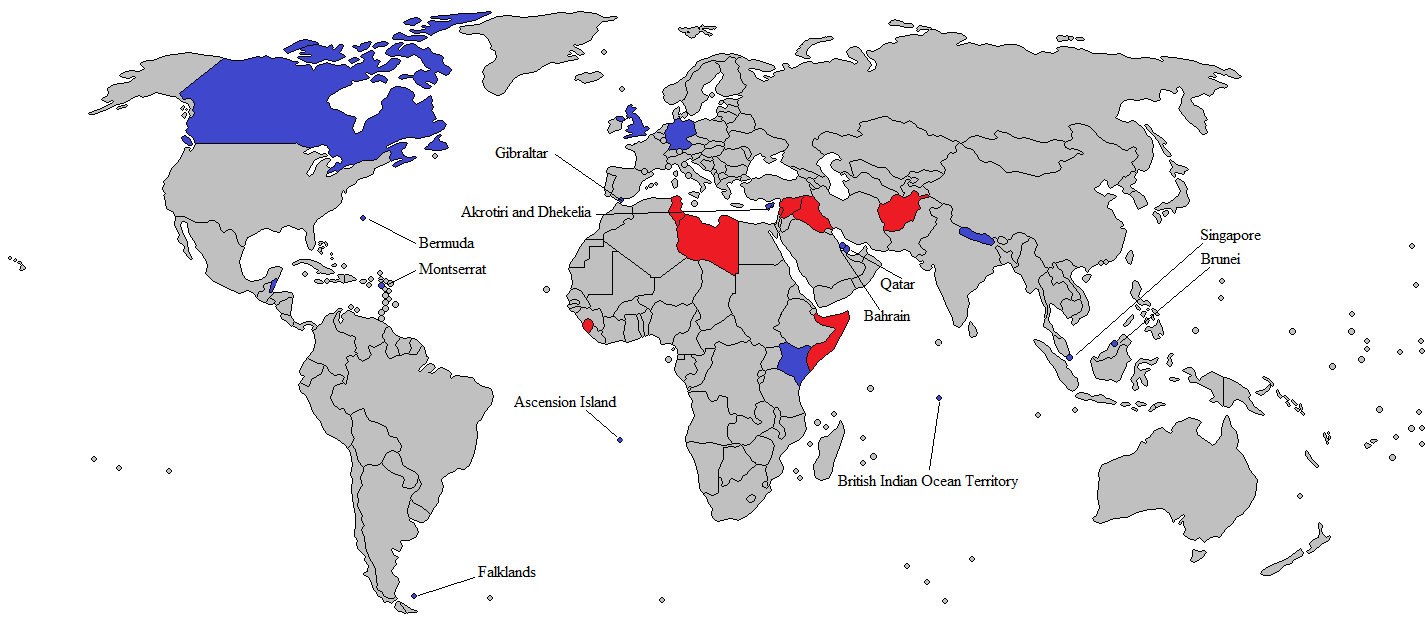

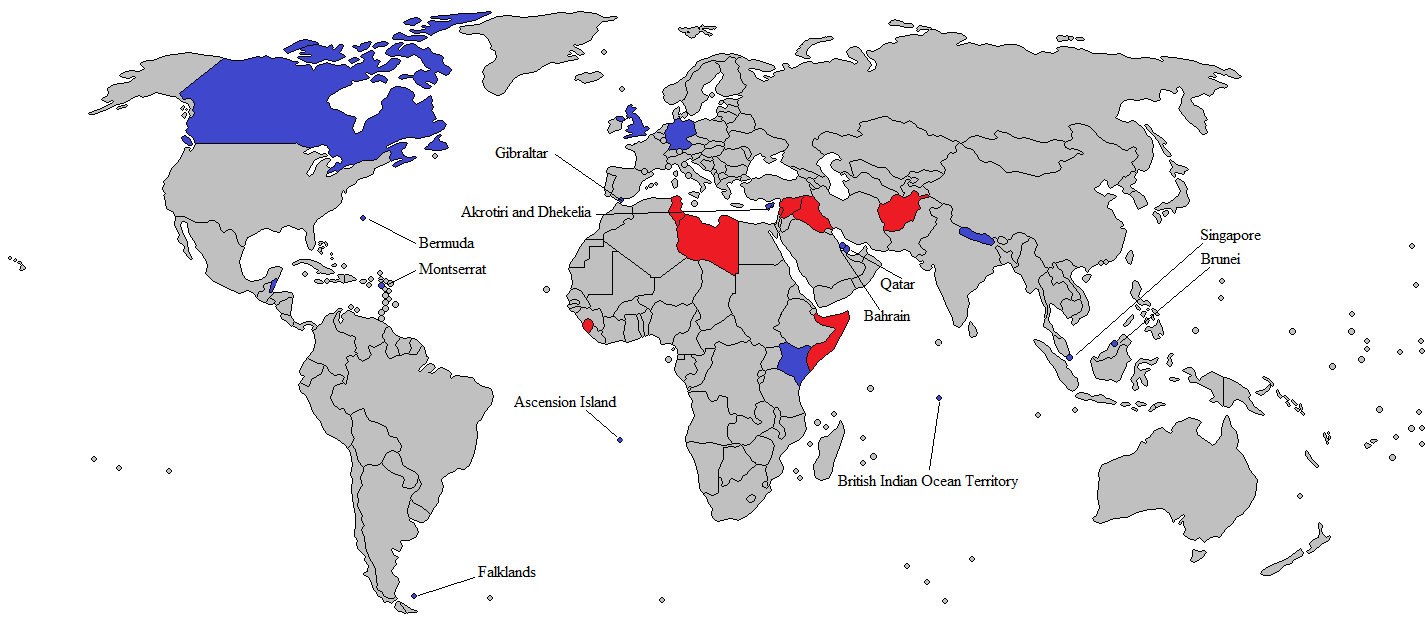

The British had built up a very large worldwide Empire, which peaked in size in 1922, after more than half a century of unchallenged global supremacy. The cumulative costs of fighting two world wars, however, placed a heavy burden upon the home economy, and after 1945 the British Empire rapidly began to disintegrate, with all the major colonies gaining independence. By the mid-to-late 1950s, the UK's status as a superpower was gone in the face of the United States and the Soviet Union. Most former colonies joined the "Commonwealth of Nations", an organisation of fully independent nations now with equal status to the UK. However it attempted no major collective policies. The last major colony, Hong Kong, was handed over to China in 1997. Fourteen British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remnants of the former Bri ...

maintain a constitutional link to the UK, but are not part of the country per se.

Britain slashed its involvements in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

after the humiliating Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of 1956. However Britain did forge close military ties with the United States, France, and Germany, through the NATO military alliance. After years of debate (and rebuffs), Britain joined the Common Market in 1973; which became the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

in 1993. However it did not merge financially, and kept the pound separate from the Euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

, which partly isolated it from the EU financial crisis of 2011. In June 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU.

21st century

Foreign policy initiatives of UK governments since the 1990s have included military intervention in conflicts and for peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance programmes and increased aid spending, support for establishment of the

Foreign policy initiatives of UK governments since the 1990s have included military intervention in conflicts and for peacekeeping, humanitarian assistance programmes and increased aid spending, support for establishment of the International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and International court, international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to pro ...

, debt relief for developing countries, prioritisation of initiatives to address climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, and promotion of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

. The British approach has been described as "spread the right norms and sustain NATO".

Lunn et al. (2008) argue:

:Three key motifs of Tony Blair's 10-year premiership were an activist philosophy of 'interventionism', maintaining a strong alliance with the US and a commitment to placing Britain at the heart of Europe. While the 'special relationship' and the question of Britain's role in Europe have been central to British foreign policy since the Second World War...interventionism was a genuinely new element.

The GREAT campaign of 2012 was one of the most ambitious national promotion efforts ever undertaken by any major nation. It was scheduled take maximum advantage of the worldwide attention to the Summer Olympics in London

Summer is the Heat, hottest of the four temperate seasons, occurring after Spring (season), spring and before autumn. At or centred on the summer solstice, the earliest sunrise and latest sunset occurs, daylight hours are longest and dark h ...

. The goals were to make British more culture visible in order to stimulate trade, investment and tourism. The government partnered with key leaders in culture, business, diplomacy and education. The campaign unified many themes and targets, including business meetings; scholarly conventions; recreational vehicle dealers; parks and campgrounds; convention and visitors bureaus; hotels; bed and breakfast inns; casinos; and hotels.

In 2013, the government of David Cameron described its approach to foreign policy by saying:

:For any given foreign policy issue, the UK potentially has a range of options for delivering impact in our national interest. ... have a complex network of alliances and partnerships through which we can work.... These include – besides the EU – the UN and groupings within it, such as the five permanent members of the Security Council (the “P5”); NATO; the Commonwealth; the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; the G8 and G20 groups of leading industrialised nations; and so on.

The UK began establishing air and naval facilities in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

, located in the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia (Middle East, The Middle East). It is ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and a ...

and Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

in 2014–15. The Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 The National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 was published by the British government during the second Cameron ministry on 23 November 2015 to outline the United Kingdom's defence strategy up to 2025. It identified ...

highlighted a range of foreign policy initiatives of the UK government. Edward Longinotti notes how current British defence policy is grappling with how to accommodate two major commitments, to Europe and to an ‘east of Suez

East of Suez is used in British military and political discussions in reference to interests beyond the European theatre, and east of the Suez Canal, and may or may not include the Middle East.

’ global military strategy, within a modest defence budget that can only fund one. He points out that Britain's December 2014 agreement to open a permanent naval base in Bahrain underlines its gradual re-commitment east of Suez. By some measures, Britain remains the second most powerful country in the world by virtue of its soft power

In politics (and particularly in international politics), soft power is the ability to co-opt rather than coerce (contrast hard power). In other words, soft power involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. A defi ...

and "logistical capability to deploy, support and sustain ilitaryforces overseas in large numbers." Although commentators have questioned the need for global power projection, the concept of “Global Britain” put forward by the Conservative government in 2019 signalled more military activity in the Middle East and Pacific, outside of NATO's traditional sphere of influence.

At the end of January 2020, the United Kingdom left the European Union, with a subsequent trade agreement with the EU in effect from 1 January 2021, setting out the terms of the UK-EU economic relationship and what abilities the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office can use in foreign relations related to trade.

Major international disputes since 1945

* 1946–1949 – involved inGreek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος}, ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom and ...

* 1945–1948 – administration of the Mandate for Palestine, ending with the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. British forces often faced conflict with Arab nationalists and Jewish Zionist militia, including those who in 1946 blew up the King David Hotel, which was British administrative and military HQ, killing 91 people.

* 1947–1991 – Cold War with Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

* 1948–1949 – Berlin Blockade – dispute with USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

over access to West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

and general Soviet expansionism in Eastern Europe

* 1948–1960 – Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War was a guerrilla war fought in British Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the military forces ...

– armed conflict against the politically isolated Communist forces of the Malayan National Liberation Army

* 1950–1953 – Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

– war with North Korea

* 1951–1954 – Abadan Crisis

The Abadan Crisis ( ''Bohrân Nafti Irân'', "Iran Oil Crisis") occurred from 1951 to 1954, after Iran nationalised the Iranian assets of the BP controlled Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) and expelled Western companies from oil refineries in th ...

– dispute with Iran over expropriated oil assets

* 1956–1957 – Suez Crisis – armed conflict with Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

over its seizure of the Suez Canal Zone

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a po ...

, and dispute with most of international community

The international community is an imprecise phrase used in geopolitics and international relations to refer to a broad group of people and governments of the world.

As a rhetorical term

Aside from its use as a general descriptor, the term is t ...

* 1958 – First Cod War

The Cod Wars ( is, Þorskastríðin; also known as , ; german: Kabeljaukriege) were a series of 20th-century confrontations between the United Kingdom (with aid from West Germany) and Iceland about fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Each of ...

– fishing dispute with Iceland

* 1962–1966 – Konfrontasi – war with Indonesia * 1972–1973 –

* 1972–1973 – Second Cod War

The Cod Wars ( is, Þorskastríðin; also known as , ; german: Kabeljaukriege) were a series of 20th-century confrontations between the United Kingdom (with aid from West Germany) and Iceland about fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Each of ...

– fishing dispute with Iceland

* 1975–1976 – Third Cod War

The Cod Wars ( is, Þorskastríðin; also known as , ; german: Kabeljaukriege) were a series of 20th-century confrontations between the United Kingdom (with aid from West Germany) and Iceland about fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Eac ...

– fishing dispute with Iceland

* 1982 – Falklands War

The Falklands War ( es, link=no, Guerra de las Malvinas) was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial ...

– war with Argentina over the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

and other British South Atlantic territory.

* 1983 – Condemnation of the United States over its invasion of Grenada

The United States invasion of Grenada began at dawn on 25 October 1983. The United States and a coalition of six Caribbean nations invaded the island nation of Grenada, north of Venezuela. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury by the U.S. military ...

.

* 1984 – dispute with Libya after a policewoman

The integration of women into law enforcement positions can be considered a large social change. A century ago, there were few jobs open to women in law enforcement. A small number of women worked as correctional officers, and their assignment ...

is shot dead in London by a gunman from within the Libyan embassy and considerable Libyan support for the IRA in Northern Ireland.

* 1988 – further dispute with Libya over the 1988 bombing of a Pan Am flight over the Scottish town of Lockerbie

Lockerbie (, gd, Locarbaidh) is a small town in Dumfries and Galloway, south-western Scotland. It is about from Glasgow, and from the border with England. The 2001 Census recorded its population as 4,009. The town came to international atte ...

* 1991 – Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

with Iraq

* 1995 – under UN mandate, military involvement in former Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

(specifically Bosnia)

* 1997 – Hong Kong handover to Chinese rule. Britain secures guarantees for a "special status" that would continue capitalism and protect existing British property.

* 1999 – involvement in NATO bombing campaign against Yugoslavia over Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a international recognition of Kosovo, partiall ...

* 2000 – British action in saving the UN peacekeeping force from collapse and defeating the anti-government rebellion during the Sierra Leone Civil War

* 2001 – UN-sponsored war against, and subsequent occupation of, Afghanistan

* 2003 – Collaborate with US and others in war and occupation of, Iraq Over 46,000 British troops subsequently occupy Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

and Southern Iraq

* 2007 – (ongoing) diplomatic dispute with Russia over the death of Alexander Litvinenko

Alexander Valterovich "Sasha" Litvinenko (30 August 1962 ( at WebCite) or 4 December 1962 – 23 November 2006) was a British-naturalised Russian defector and former officer of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) who specialised i ...

Additional matters have strained British-Russian relations; continued espionage, Russian human rights violations and support of regimes hostile to the west (Syria, Iran)

* 2009 – (ongoing) Dispute with Iran over its alleged nuclear weapons programme, including sanctions and Iranian condemnation of the British government culminating in a 2011 attack on the British Embassy in Iran

The 2011 attack on the British Embassy in Iran was a mob action on 29 November 2011 by a crowd of Iranian protesters who stormed the embassy and another British diplomatic compound in Tehran, Iran, ransacking offices and stealing documents. One s ...

.

* 2011 – under UN mandate, UK Armed Forces participated in enforcing the Libyan No-Fly Zone as part of Operation Ellamy

Operation Ellamy was the codename for the United Kingdom participation in the 2011 military intervention in Libya. The operation was part of an international coalition aimed at enforcing a Libyan no-fly zone in accordance with the United Natio ...

* 2013 – support to French forces in the Malian civil war, including training and equipment to African peacekeeping and Malian government forces.

* 2015 – support to US-led coalition against the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant.

* 2016 – P5+1 and EU implement a deal with Iran intended to prevent the country gaining access to nuclear weapons.

* 2018 – Sanctions on Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

following the poisoning of Sergei Skripal

On 4 March 2018, Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military officer and double agent for the British intelligence agencies, and his daughter, Yulia Skripal, were poisoned in the city of Salisbury, England. According to UK sources and the Orga ...

using a nerve agent in Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

, England included the expulsions of 23 diplomats, the largest ever since the Cold War, an act that was retaliated by Russia. A further war of words entailed and relations are deteriorating.

* 2019 – The sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago is disputed between the United Kingdom and Mauritius. In February 2019, the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordan ...

in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

ruled that the United Kingdom must transfer the islands to Mauritius as they were not legally separated from the latter in 1965. On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

debated and adopted a resolution that affirmed that the Chagos archipelago “forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius.” The UK does not recognise Mauritius' sovereignty claim over the Chagos Islands. Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth

Pravind Kumar Jugnauth (born 25 December 1961) is a Mauritian politician serving as the prime minister of Mauritius since January 2017. Jugnauth has been the leader of the Militant Socialist Movement (MSM) party since April 2003. He has held a n ...

described the British and American governments as "hypocrites" and "champions of double talk" over their response to the dispute.

* 2019 – The Persian Gulf crisis escalated in July 2019, when Iranian oil tanker was seized by Britain in the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

on the grounds that it was shipping oil to Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

in violation of European Union sanctions. Iran later captured a British oil tanker and its crew members in the Persian Gulf.

Sovereignty disputes

* Spain claims the British overseas territory of

* Spain claims the British overseas territory of Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

.

* The entire Chagos Archipelago

The Chagos Archipelago () or Chagos Islands (formerly the Bassas de Chagas, and later the Oil Islands) is a group of seven atolls comprising more than 60 islands in the Indian Ocean about 500 kilometres (310 mi) south of the Maldives arc ...

in the British Indian Ocean Territory

The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) is an Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom situated in the Indian Ocean, halfway between Tanzania and Indonesia. The territory comprises the seven atolls of the Chagos Archipelago with over 1,000 ...

is claimed

"Claimed" is the eleventh episode of the fourth season of the post-apocalyptic horror television series '' The Walking Dead'', which aired on AMC on February 23, 2014. The episode was written by Nichole Beattie and Seth Hoffman, and directed ...

by Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

and the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipelag ...

. The claim includes the island of Diego Garcia used as a joint UK/US military base since the 1970s when the inhabitants were forcibly removed, Blenheim Reef, Speakers Bank and all the other features.

* There are conflicting claims over the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oc ...

, controlled by the United Kingdom but claimed by Argentina. The dispute escalated into the Falklands War in 1982 over the islands' sovereignty, in which Argentina was defeated.

* There is a territorial claim in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, the British Antarctic Territory, which overlaps with areas claimed by Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

and Argentina.

Commonwealth of Nations

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. Charles III of the United Kingdom

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

is Head of the Commonwealth and is King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

of 15 of its 56 member states. Those that retain the King as head of state are called Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonwealt ...

s. Over time several countries have been suspended from the Commonwealth for various reasons. Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and ...

was suspended because of the authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

rule of its President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

and so too was Pakistan, but it has since returned. Countries which become republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

s are still eligible for membership of the Commonwealth so long as they are deemed democratic. Commonwealth nations such as Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

enjoyed no export duties in trade with the UK before the UK concentrated its economic relationship with EU member states.

The UK was once a dominant colonial power in many countries on the continent of Africa and its multinationals remain large investors in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

. Nowadays the UK, as a leading member of the Commonwealth of Nations, seeks to influence Africa through its foreign policies. Current UK disputes are with Zimbabwe over human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

violations. Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of t ...

set up the Africa Commission and urged rich countries to cease demanding developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

repay their large debts. Relationships with developed (often former dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

) nations are strong with numerous cultural, social and political links, mass inter-migration trade links as well as calls for Commonwealth free trade.

From 2016 to 2018, the Windrush scandal occurred, where the UK deported a number British Citizens with Commonwealth heritage back to their Commonwealth country on claims they were "illegal immigrants".

Africa

Americas

Asia

Europe

The UK maintained good relations with Western Europe since 1945, and Eastern Europe since end of the Cold War in 1989. After years of dispute with France it joined the European Economic Community in 1973, which eventually evolved into the European Union through theMaastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve member states of the European Communities, it announced "a new stage in the ...

twenty years later. Unlike the majority of European countries, the UK does not use the euro as its currency and is not a member of the Eurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU pol ...

. During the years of its membership of the European Union, the United Kingdom had often been referred to as a "peculiar" member, due to its occasional dispute in policies with the organisation. The United Kingdom regularly opted out of EU legislation and policies. Through differences in geography, culture and history, national opinion polls have found that of the 28 nationalities in the European Union, British people have historically felt the least European. On 23 June 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union and formally left on 31 January 2020.

European Union

Oceania

Overseas Territories

International organisations

The United Kingdom is a member of the following international organisations: * ADB - Asian Development Bank (nonregional member) *AfDB

The African Development Bank Group (AfDB) or (BAD) is a multilateral development finance institution headquartered in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, since September 2014. The AfDB is a financial provider to African governments and private companies i ...

- African Development Bank (nonregional member)

* Arctic Council

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments and the indigenous people of the Arctic. At present, eight countries exercise sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic Circle, ...

(observer)

* Australia Group

* BIS - Bank for International Settlements

* Commonwealth of Nations

* CBSS - Council of the Baltic Sea States (observer)

* CDB - Caribbean Development Bank

* Council of Europe

* CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN (; ; ), is an intergovernmental organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, it is based in a northwestern suburb of Gen ...

- European Organization for Nuclear Research

* EAPC - Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council

* EBRD - European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

* EIB - European Investment Bank

* ESA - European Space Agency

* FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization

* FATF - Financial Action Task Force

* G-20 - Group of Twenty

* G-5 - Group of Five

* G7 - Group of Seven

* G8 - Group of Eight

* G-10 - Group of Ten (economics)

* IADB - Inter-American Development Bank

* IAEA

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 195 ...

- International Atomic Energy Agency

* IBRD - International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (also known as the World Bank)

* ICAO

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO, ) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that coordinates the principles and techniques of international air navigation, and fosters the planning and development of international a ...

- International Civil Aviation Organization

* ICC - International Chamber of Commerce

* ICCt - International Criminal Court

* ICRM - International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

* IDA - International Development Association

* IEA - International Energy Agency

* IFAD - International Fund for Agricultural Development

* IFC - International Finance Corporation

* IFRCS - International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

* IHO - International Hydrographic Organization

* ILO

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and ol ...

- International Labour Organization

* IMF

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glob ...

- International Monetary Fund

* IMO - International Maritime Organization

* IMSO - International Mobile Satellite Organization

* Interpol

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO; french: link=no, Organisation internationale de police criminelle), commonly known as Interpol ( , ), is an international organization that facilitates worldwide police cooperation and cr ...

- International Criminal Police Organization

* IOC - International Olympic Committee

* IOM - International Organization for Migration

* IPU - Inter-Parliamentary Union

* ISO - International Organization for Standardization

* ITSO - International Telecommunications Satellite Organization

* ITU

The International Telecommunication Union is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for many matters related to information and communication technologies. It was established on 17 May 1865 as the International Telegraph Union ...

- International Telecommunication Union

* ITUC - International Trade Union Confederation

* MIGA

The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) is an international financial institution which offers political risk insurance and credit enhancement guarantees. These guarantees help investors protect foreign direct investments against ...

- Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency

* MONUSCO

The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or MONUSCO, an acronym based on its French name , is a United Nations peacekeeping force in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) which was estab ...

- United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

* NATO - North Atlantic Treaty Organization

* NEA - Nuclear Energy Agency

* NSG - Nuclear Suppliers Group

* OAS - Organization of American States (observer)

* OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate ...

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

* OPCW

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is an intergovernmental organisation and the implementing body for the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which entered into force on 29 April 1997. The OPCW, with its 193 member s ...

- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons

* OSCE - Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

* Paris Club

* PCA - Permanent Court of Arbitration

* PIF - Pacific Islands Forum (partner)

* SECI - Southeast European Cooperative Initiative (observer)

* UN - United Nations

* UNSC - United Nations Security Council

* UNCTAD - United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

* UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

* UNFICYP

The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) is a United Nations peacekeeping force that was established under United Nations Security Council Resolution 186 in 1964 to prevent a recurrence of fighting following intercommunal violen ...

- United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus

* UNHCR

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrat ...

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

* UNIDO - United Nations Industrial Development Organization

* UNMIS

The United Nations Mission in the Sudan (UNMIS) was established by the UN Security Council under Resolution 1590 of 24 March 2005, in response to the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the government of the Sudan and the Suda ...

- United Nations Mission in Sudan

* UNRWA

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is a UN agency that supports the relief and human development of Palestinian refugees. UNRWA's mandate encompasses Palestinians displaced by the 1948 P ...

- United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

* UPU

Upu or Apu, also rendered as Aba/Apa/Apina/Ubi/Upi, was the region surrounding Damascus of the 1350 BC Amarna letters. Damascus was named ''Dimašqu'' / ''Dimasqu'' / etc. (for example, "Dimaški"-(see: Niya (kingdom)), in the letter corresponde ...

- Universal Postal Union

* WCO - World Customs Organization

* WHO - World Health Organization

* WIPO - World Intellectual Property Organization

* WMO

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology and geophysics.

The WMO originated from the Internatio ...

- World Meteorological Organization

* WTO - World Trade Organization

* Zangger Committee The Zangger Committee, also known as the Nuclear Exporters Committee, sprang from Article III.2 of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) which entered into force on March 5, 1970. Under the terms of Article III.2 International ...

- (also known as the) Nuclear Exporters Committee

See also

* Timeline of British diplomatic history *Timeline of European imperialism

This Timeline of European imperialism covers episodes of imperialism by western nations since 1400; for other countries, see .

Pre-1700

* 1402 Castillian invasion of Canary Islands.

* 1415 Portuguese conquest of Ceuta.

* 1420-1425 Portuguese ...

* Anglophobia

* British diaspora

* History of the United Kingdom

* Soft power#United Kingdom

* Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office

* Heads of United Kingdom Missions

* List of diplomatic missions of the United Kingdom

* European Union–United Kingdom relations

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

* Latin America–United Kingdom relations

* United Kingdom–Crown Dependencies Customs Union

References

Bibliography

* Casey, Terrence. ''The Blair Legacy: Politics, Policy, Governance, and Foreign Affairs'' (2009excerpt and text search

* Daddow, Oliver, and Jamie Gaskarth, eds. ''British foreign policy: the New Labour years'' (Palgrave, 2011) * Daddow, Oliver. "Constructing a ‘great’ role for Britain in an age of austerity: Interpreting coalition foreign policy, 2010–2015." ''International Relations'' 29.3 (2015): 303-318. * Dickie, John. ''The New Mandarins: How British Foreign Policy Works'' (2004) * Dumbrell, John. ''A special relationship: Anglo-American relations from the Cold War to Iraq'' (2006) * Finlan, Alastair. ''Contemporary Military Strategy and the Global War on Terror: US and UK Armed Forces in Afghanistan and Iraq 2001-2012'' (2014) * Honeyman, V. C. "From Liberal Interventionism to Liberal Conservatism: the short road in foreign policy from Blair to Cameron." ''British Politics'' (2015)

abstract

* Lane, Ann. ''Strategy, Diplomacy and UK Foreign Policy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) * Leech, Philip, and Jamie Gaskarth. "British Foreign Policy and the Arab Spring." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 26#1 (2015). * Lunn, Jon, Vaughne Miller, Ben Smith. "British foreign policy since 1997 - Commons Library Research Paper RP08/56" (UK House of Commons, 2008) 123p

online

* Magyarics, Tamas

Balancing in Central Europe: Great Britain and Hungary in the 1920s

* Seah, Daniel. "The CFSP as an aspect of conducting foreign relations by the United Kingdom: With Special Reference to the Treaty of Amity & Cooperation in Southeast Asia]" ''International Review of Law'' (2015)

online

* Robert William Seton-Watson, Seton-Watson, R. W. ''Britain in Europe (1789–1914): A Survey of Foreign Policy'' (1937)

online

* Stephens, Philip. '' Britain Alone: The Path from Suez to Brexit'' (2021

excerpted

* Whitman, Richard G. "The calm after the storm? Foreign and security policy from Blair to Brown." ''Parliamentary Affairs'' 63.4 (2010): 834–848.

online

* Williams, Paul. ''British Foreign Policy under New Labour'' (2005)

Primary sources

* Blair, Tony. ''A Journey: My Political Life'' (2010)External links

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

{{DEFAULTSORT:Foreign Relations Of The United Kingdom