Filipinos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Filipinos ( tl, Mga Pilipino) are the people who are citizens of or native to the

The Tabon Cave remains (along with the

The Tabon Cave remains (along with the  Austronesians from the Philippines also later settled Guam and the other islands of

Austronesians from the Philippines also later settled Guam and the other islands of

Naturales 4.png, Tagalog ''maharlika'', c.1590

The Philippines was settled by the

The Philippines was settled by the

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines, especially through the commencement of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade that connected the

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines, especially through the commencement of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade that connected the

A total of 110 Manila galleon, Manila-Acapulco galleons set sail between 1565 and 1815, during the Philippines trade with Mexico. Until 1593, three or more ships would set sail annually from each port bringing with them the riches of the archipelago to Spain. European ''criollos'', ''mestizos'' and Portuguese, French and Mexican descent from the Americas, mostly from Latin America came in contact with the Filipinos. Japanese people, Japanese, Indian people, Indian and Demographics of Cambodia, Cambodian Christians who fled from religious persecutions and killing fields also settled in the Philippines during the 17th until the 19th centuries. The Mexicans especially were a major source of military migration to the Philippines and during the Spanish period they were referred to as guachinangos"Intercolonial Intimacies Relinking Latin/o America to the Philippines, 1898–1964 Paula C. Park" Page 100 and they readily intermarried and mixed with native Filipinos. Bernal, the author of the book "Mexico en Filipinas" contends, that they were middlemen, the guachinangos in contrast to the Spanish and criollos, known as Castila, that had positions in power and were isolated, the guachinangos in the meantime, had interacted with the natives of the Philippines, while in contrast, the exchanges between Castila and native were negligent. Following Bernal, these two groups—native Filipinos and the Castila—had been two “mutually unfamiliar castes” that had “no real contact.” Between them, he clarifies however, were the Chinese traders and the guachinangos (Mexicans).

With the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1867, Spain opened the

A total of 110 Manila galleon, Manila-Acapulco galleons set sail between 1565 and 1815, during the Philippines trade with Mexico. Until 1593, three or more ships would set sail annually from each port bringing with them the riches of the archipelago to Spain. European ''criollos'', ''mestizos'' and Portuguese, French and Mexican descent from the Americas, mostly from Latin America came in contact with the Filipinos. Japanese people, Japanese, Indian people, Indian and Demographics of Cambodia, Cambodian Christians who fled from religious persecutions and killing fields also settled in the Philippines during the 17th until the 19th centuries. The Mexicans especially were a major source of military migration to the Philippines and during the Spanish period they were referred to as guachinangos"Intercolonial Intimacies Relinking Latin/o America to the Philippines, 1898–1964 Paula C. Park" Page 100 and they readily intermarried and mixed with native Filipinos. Bernal, the author of the book "Mexico en Filipinas" contends, that they were middlemen, the guachinangos in contrast to the Spanish and criollos, known as Castila, that had positions in power and were isolated, the guachinangos in the meantime, had interacted with the natives of the Philippines, while in contrast, the exchanges between Castila and native were negligent. Following Bernal, these two groups—native Filipinos and the Castila—had been two “mutually unfamiliar castes” that had “no real contact.” Between them, he clarifies however, were the Chinese traders and the guachinangos (Mexicans).

With the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1867, Spain opened the  In the 1860s to 1890s, in the urban areas of the Philippines, especially at Manila, according to burial statistics, as much as 3.3% of the population were pure European Spaniards and the pure Chinese were as high as 9.9%. The Spanish Filipino and Chinese Filipino Mestizo populations also fluctuated. Eventually, many families belonging to the non-native categories from centuries ago beyond the late 19th century diminished because their descendants intermarried enough and were assimilated into and chose to self-identify as Filipinos while forgetting their ancestor's roots since during the Philippine Revolution to modern times, the term "Filipino" was expanded to include everyone born in the Philippines coming from any race, as per the

In the 1860s to 1890s, in the urban areas of the Philippines, especially at Manila, according to burial statistics, as much as 3.3% of the population were pure European Spaniards and the pure Chinese were as high as 9.9%. The Spanish Filipino and Chinese Filipino Mestizo populations also fluctuated. Eventually, many families belonging to the non-native categories from centuries ago beyond the late 19th century diminished because their descendants intermarried enough and were assimilated into and chose to self-identify as Filipinos while forgetting their ancestor's roots since during the Philippine Revolution to modern times, the term "Filipino" was expanded to include everyone born in the Philippines coming from any race, as per the

After the defeat of Spain during the Spanish–American War in 1898, Filipino general, Emilio Aguinaldo declared Philippine Declaration of Independence, independence on June 12 while General Wesley Merritt became the first American Governor-General of the Philippines#United States Military Government (1898–1901), governor of the Philippines. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris (1898), Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, with Spain ceding the Philippines and other colonies to the United States in exchange for $20 million.

After the defeat of Spain during the Spanish–American War in 1898, Filipino general, Emilio Aguinaldo declared Philippine Declaration of Independence, independence on June 12 while General Wesley Merritt became the first American Governor-General of the Philippines#United States Military Government (1898–1901), governor of the Philippines. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris (1898), Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, with Spain ceding the Philippines and other colonies to the United States in exchange for $20 million.

The Philippine–American War resulted in the deaths of at least 200,000 Filipino civilians. Some estimates for total civilian dead reach up to 1,000,000. After the Philippine–American War, the United States civil governance was established in 1901, with William Howard Taft as the first American Governor-General of the Philippines#United States Colonial Government (1901-1935), Governor-General. A number of Americans settled in the islands and thousands of interracial marriages between Americans and Filipinos have taken place since then. Owing to the strategic location of the Philippines, as many as 21 bases and 100,000 military personnel were stationed there since the United States first colonized the islands in 1898. These bases were decommissioned in 1992 after the end of the Cold War, but left behind thousands of Amerasian children. The country gained independence from the United States in 1946. The Green Hills Farm, Pearl S. Buck International Foundation estimates there are 52,000 Amerasians scattered throughout the Philippines. However, according to the center of Amerasian Research, there might be as many as 250,000 Amerasians scattered across the cities of New Clark City, Clark, Angeles City,

The Philippine–American War resulted in the deaths of at least 200,000 Filipino civilians. Some estimates for total civilian dead reach up to 1,000,000. After the Philippine–American War, the United States civil governance was established in 1901, with William Howard Taft as the first American Governor-General of the Philippines#United States Colonial Government (1901-1935), Governor-General. A number of Americans settled in the islands and thousands of interracial marriages between Americans and Filipinos have taken place since then. Owing to the strategic location of the Philippines, as many as 21 bases and 100,000 military personnel were stationed there since the United States first colonized the islands in 1898. These bases were decommissioned in 1992 after the end of the Cold War, but left behind thousands of Amerasian children. The country gained independence from the United States in 1946. The Green Hills Farm, Pearl S. Buck International Foundation estimates there are 52,000 Amerasians scattered throughout the Philippines. However, according to the center of Amerasian Research, there might be as many as 250,000 Amerasians scattered across the cities of New Clark City, Clark, Angeles City,

People classified as 'blancos' (whites) were the insulares or "Filipinos" (a person born in the Philippines of pure Spanish descent), peninsulares (a person born in Spain of pure Spanish descent), Español mestizos (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian and Spanish ancestry) and tornatrás (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian, Chinese and Spanish ancestry).

People classified as 'blancos' (whites) were the insulares or "Filipinos" (a person born in the Philippines of pure Spanish descent), peninsulares (a person born in Spain of pure Spanish descent), Español mestizos (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian and Spanish ancestry) and tornatrás (a person born in the Philippines of mixed Austronesian, Chinese and Spanish ancestry).  People who lived outside

People who lived outside  The term ''negrito'' was coined by the Spaniards based on their appearance. The word 'negrito' would be misinterpreted and used by future European scholars as an ethnoracial term in and of itself. Both Christianized negritos who lived in the colony and un-Christianized negritos who lived in tribes outside the colony were classified as 'negritos'. Christianized negritos who lived in Manila were not allowed to enter Intramuros and lived in areas designated for indios.

A person of mixed Negrito and Austronesian ancestry were classified based on patrilineal descent; the father's ancestry determined a child's legal classification. If the father was 'negrito' and the mother was 'India' (Austronesian), the child was classified as 'negrito'. If the father was 'indio' and the mother was 'negrita', the child was classified as 'indio'. Persons of Negrito descent were viewed as being outside the social order as they usually lived in tribes outside the colony and resisted conversion to Christianity.

This legal system of racial classification based on patrilineal descent had no parallel anywhere in the Spanish-ruled colonies in the Americas. In general, a son born of a sangley male and an indio or mestizo de sangley female was classified as mestizo de sangley; all subsequent male descendants were mestizos de sangley regardless of whether they married an India or a mestiza de sangley. A daughter born in such a manner, however, acquired the legal classification of her husband, i.e., she became an India if she married an indio but remained a mestiza de sangley if she married a mestizo de sangley or a sangley. In this way, a chino mestizo male descendant of a paternal sangley ancestor never lost his legal status as a mestizo de sangley no matter how little percentage of Chinese blood he had in his veins or how many generations had passed since his first Chinese ancestor; he was thus a mestizo de sangley in perpetuity.

However, a 'mestiza de sangley' who married a blanco ('Filipino', 'mestizo de español', 'peninsular' or 'americano') kept her status as 'mestiza de sangley'. But her children were classified as tornatrás. An 'India' who married a blanco also kept her status as India, but her children were classified as mestizo de español. A mestiza de español who married another blanco would keep her status as mestiza, but her status will never change from mestiza de español if she married a mestizo de español, Filipino or peninsular. In contrast, a mestizo (de sangley or español) man's status stayed the same regardless of whom he married. If a mestizo (de sangley or español) married a filipina (woman of pure Spanish descent), she would lose her status as a 'filipina' and would acquire the legal status of her husband and become a mestiza de español or sangley. If a 'filipina' married an 'indio', her legal status would change to 'India', despite being of pure Spanish descent.

The social stratification system based on class that continues to this day in the country had its beginnings in the Spanish Philippines, Spanish colonial area with a discriminating caste system.

The Spanish colonizers reserved the term ''Filipino'' to refer to Spaniards born in the Philippines. The use of the term was later extended to include Spanish and Chinese mestizos or those born of mixed Chinese-indio or Spanish-indio descent. Late in the 19th century, José Rizal popularized the use of the term ''Filipino'' to refer to all those born in the Philippines, including the Indios. When ordered to sign the notification of his death sentence, which described him as a Chinese mestizo, Rizal refused. He went to his death saying that he was ''indio puro''.

After the Philippines' independence from Spain in 1898 and the word Filipino 'officially' expanded to include the entire population of the Philippines regardless of racial ancestry, as per the

The term ''negrito'' was coined by the Spaniards based on their appearance. The word 'negrito' would be misinterpreted and used by future European scholars as an ethnoracial term in and of itself. Both Christianized negritos who lived in the colony and un-Christianized negritos who lived in tribes outside the colony were classified as 'negritos'. Christianized negritos who lived in Manila were not allowed to enter Intramuros and lived in areas designated for indios.

A person of mixed Negrito and Austronesian ancestry were classified based on patrilineal descent; the father's ancestry determined a child's legal classification. If the father was 'negrito' and the mother was 'India' (Austronesian), the child was classified as 'negrito'. If the father was 'indio' and the mother was 'negrita', the child was classified as 'indio'. Persons of Negrito descent were viewed as being outside the social order as they usually lived in tribes outside the colony and resisted conversion to Christianity.

This legal system of racial classification based on patrilineal descent had no parallel anywhere in the Spanish-ruled colonies in the Americas. In general, a son born of a sangley male and an indio or mestizo de sangley female was classified as mestizo de sangley; all subsequent male descendants were mestizos de sangley regardless of whether they married an India or a mestiza de sangley. A daughter born in such a manner, however, acquired the legal classification of her husband, i.e., she became an India if she married an indio but remained a mestiza de sangley if she married a mestizo de sangley or a sangley. In this way, a chino mestizo male descendant of a paternal sangley ancestor never lost his legal status as a mestizo de sangley no matter how little percentage of Chinese blood he had in his veins or how many generations had passed since his first Chinese ancestor; he was thus a mestizo de sangley in perpetuity.

However, a 'mestiza de sangley' who married a blanco ('Filipino', 'mestizo de español', 'peninsular' or 'americano') kept her status as 'mestiza de sangley'. But her children were classified as tornatrás. An 'India' who married a blanco also kept her status as India, but her children were classified as mestizo de español. A mestiza de español who married another blanco would keep her status as mestiza, but her status will never change from mestiza de español if she married a mestizo de español, Filipino or peninsular. In contrast, a mestizo (de sangley or español) man's status stayed the same regardless of whom he married. If a mestizo (de sangley or español) married a filipina (woman of pure Spanish descent), she would lose her status as a 'filipina' and would acquire the legal status of her husband and become a mestiza de español or sangley. If a 'filipina' married an 'indio', her legal status would change to 'India', despite being of pure Spanish descent.

The social stratification system based on class that continues to this day in the country had its beginnings in the Spanish Philippines, Spanish colonial area with a discriminating caste system.

The Spanish colonizers reserved the term ''Filipino'' to refer to Spaniards born in the Philippines. The use of the term was later extended to include Spanish and Chinese mestizos or those born of mixed Chinese-indio or Spanish-indio descent. Late in the 19th century, José Rizal popularized the use of the term ''Filipino'' to refer to all those born in the Philippines, including the Indios. When ordered to sign the notification of his death sentence, which described him as a Chinese mestizo, Rizal refused. He went to his death saying that he was ''indio puro''.

After the Philippines' independence from Spain in 1898 and the word Filipino 'officially' expanded to include the entire population of the Philippines regardless of racial ancestry, as per the

File:Indios, detail from Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas 1734.jpg, Native Filipinos as illustrated in the ''Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas'' (1734)

File:A Spaniard, a Criollo, Aetas, and a cockfight, detail from Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas (1734).jpg, A Spaniard and Criollo talking, while Indios are cockfight with Aetas in the background. detail from Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas.

File:Mestizo de luto by José Honorato Lozano.jpg, "''Mestizo de luto''" (A Native Filipino Mestizo) by José Honorato Lozano

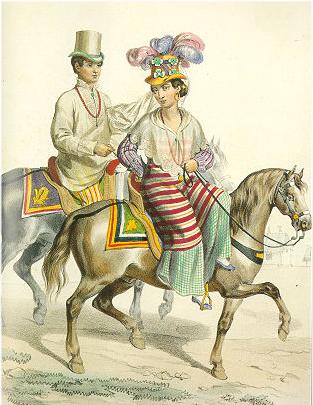

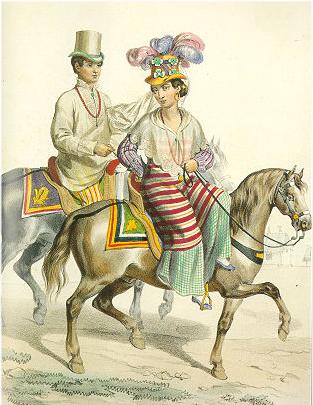

File:Indio A Caballo by José Honorato Lozano.jpg, Native riding a horse by José Honorato Lozano

File:Cuadrillero by José Honorato Lozano.jpg, Cuadrillero by José Honorato Lozano

File:Gobernadorcillo de Naturales by José Honorato Lozano.jpg, A Gobernadorcillo, mostly of Indio descent. Painting by José Honorato Lozano

File:Chino Pansitero by José Honorato Lozano.jpg, Sangley Pancit vendor by José Honorato Lozano

File:Damian domingo.png, Damián Domingo, A mestizo de Sangley soldier and artist.

File:Tampuhan by Juan Luna.jpg, Filipino couple in Tampuhan (painting), Tampuhan by Juan Luna

File:A family belonging to the Principalia.JPG, Typical costume of a ''

Austronesian languages have been spoken in the Philippines for thousands of years. According to a 2014 study by Mark Donohue of the Australian National University and Tim Denham of Monash University, there is no linguistic evidence for an orderly north-to-south dispersal of the Austronesian languages from Taiwan through the Philippines and into Island Southeast Asia (ISEA). Many adopted words from Sanskrit and Tamil were incorporated during the strong wave of Hinduism in the Philippines, Indian (Hindu-Buddhist) cultural influence starting from the 5th century BC, in common with its Southeast Asian neighbors. Chinese languages were also commonly spoken among the traders of the archipelago. However, with the advent of Islam, Arabic and Persian soon came to supplant Sanskrit and Tamil as holy languages. Starting in the second half of the 16th century, Spanish was the official language of the country for the more than three centuries that the islands were governed through

Austronesian languages have been spoken in the Philippines for thousands of years. According to a 2014 study by Mark Donohue of the Australian National University and Tim Denham of Monash University, there is no linguistic evidence for an orderly north-to-south dispersal of the Austronesian languages from Taiwan through the Philippines and into Island Southeast Asia (ISEA). Many adopted words from Sanskrit and Tamil were incorporated during the strong wave of Hinduism in the Philippines, Indian (Hindu-Buddhist) cultural influence starting from the 5th century BC, in common with its Southeast Asian neighbors. Chinese languages were also commonly spoken among the traders of the archipelago. However, with the advent of Islam, Arabic and Persian soon came to supplant Sanskrit and Tamil as holy languages. Starting in the second half of the 16th century, Spanish was the official language of the country for the more than three centuries that the islands were governed through

La persecución del uso oficial del idioma español en Filipinas

Retrieved July 8, 2010.) An additional 60% is said to have spoken Spanish as a second language until World War II, but this is also disputed as to whether this percentage spoke "kitchen Spanish", which was used as marketplace lingua compared to those who were actual fluent Spanish speakers. In 1863 a Spanish decree introduced universal education, creating free public schooling in Spanish, yet it was never implemented, even before the advent of American annexation. It was also the language of the Philippine Revolution, and the 1899 Malolos Constitution proclaimed it as the "official language" of the

According to National Statistics Office (NSO) as of 2010, over 92% of the population were Christianity in the Philippines, Christians, with 80.6% professing Roman Catholicism in the Philippines, Roman Catholicism. The latter was introduced by the Spanish beginning in 1521, and during their 300-year Spanish colonization of the Philippines, colonization of the islands, they managed to convert a vast majority of Filipinos, resulting in the Philippines becoming the largest Catholic country in Asia. There are also large groups of Protestantism in the Philippines, Protestant denominations, which either grew or were founded following the Secular state, disestablishment of the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines, Catholic Church during the American Colonial Period (Philippines), American Colonial period. The Iglesia ni Cristo is currently the single largest church whose headquarters is in the Philippines, followed by United Church of Christ in the Philippines. The Iglesia Filipina Independiente (also known as the Aglipayan Church) was an earlier development, and is a national church directly resulting from the Philippine Revolution, 1898 Philippine Revolution. Other Christian groups such as the Victory Christian Fellowship, Victory Church, Jesus Miracle Crusade, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Philippines, Mormonism, Philippine Orthodox Church, Orthodoxy, and the Jehovah's Witnesses have a visible presence in the country.

The second largest religion in the country is Islam, estimated to account for 5% to 8% of the population. Islam in the Philippines is mostly concentrated in southwestern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago which, though part of the Philippines, are very close to the neighboring Muslim world, Islamic countries of Malaysia and Indonesia. The Muslims call themselves ''Moros'', a Spanish language in the Philippines, Spanish word that refers to the Moors (albeit the two groups have little cultural connection other than Islam).

Historically, ancient Filipinos held animist religions that were influenced by Hinduism in the Philippines, Hinduism and Buddhism in the Philippines, Buddhism, which were brought by traders from neighbouring Asian states. These indigenous Philippine folk religions continue to be present among the populace, with some communities, such as the Aeta, Igorot, and Lumad, having some strong adherents and some who mix beliefs originating from the indigenous religions with beliefs from Christianity or Islam.

, religious groups together constituting less than five percent of the population included Sikhism,

According to National Statistics Office (NSO) as of 2010, over 92% of the population were Christianity in the Philippines, Christians, with 80.6% professing Roman Catholicism in the Philippines, Roman Catholicism. The latter was introduced by the Spanish beginning in 1521, and during their 300-year Spanish colonization of the Philippines, colonization of the islands, they managed to convert a vast majority of Filipinos, resulting in the Philippines becoming the largest Catholic country in Asia. There are also large groups of Protestantism in the Philippines, Protestant denominations, which either grew or were founded following the Secular state, disestablishment of the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines, Catholic Church during the American Colonial Period (Philippines), American Colonial period. The Iglesia ni Cristo is currently the single largest church whose headquarters is in the Philippines, followed by United Church of Christ in the Philippines. The Iglesia Filipina Independiente (also known as the Aglipayan Church) was an earlier development, and is a national church directly resulting from the Philippine Revolution, 1898 Philippine Revolution. Other Christian groups such as the Victory Christian Fellowship, Victory Church, Jesus Miracle Crusade, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Philippines, Mormonism, Philippine Orthodox Church, Orthodoxy, and the Jehovah's Witnesses have a visible presence in the country.

The second largest religion in the country is Islam, estimated to account for 5% to 8% of the population. Islam in the Philippines is mostly concentrated in southwestern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago which, though part of the Philippines, are very close to the neighboring Muslim world, Islamic countries of Malaysia and Indonesia. The Muslims call themselves ''Moros'', a Spanish language in the Philippines, Spanish word that refers to the Moors (albeit the two groups have little cultural connection other than Islam).

Historically, ancient Filipinos held animist religions that were influenced by Hinduism in the Philippines, Hinduism and Buddhism in the Philippines, Buddhism, which were brought by traders from neighbouring Asian states. These indigenous Philippine folk religions continue to be present among the populace, with some communities, such as the Aeta, Igorot, and Lumad, having some strong adherents and some who mix beliefs originating from the indigenous religions with beliefs from Christianity or Islam.

, religious groups together constituting less than five percent of the population included Sikhism,

There are currently more than 10 million Filipinos who live overseas. Filipinos form a minority ethnic group in the Americas, Europe, Oceania, the Middle East, and other regions of the world.

There are an estimated four million Filipino American, Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 300,000 American citizens in the Philippines. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, immigrants from the Philippines made up the second largest group after Mexico that sought family reunification.Castles, Stephen and Mark J. Miller. (July 2009).

There are currently more than 10 million Filipinos who live overseas. Filipinos form a minority ethnic group in the Americas, Europe, Oceania, the Middle East, and other regions of the world.

There are an estimated four million Filipino American, Americans of Filipino ancestry in the United States, and more than 300,000 American citizens in the Philippines. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, immigrants from the Philippines made up the second largest group after Mexico that sought family reunification.Castles, Stephen and Mark J. Miller. (July 2009).

Migration in the Asia-Pacific Region

". ''Migration Information Source''. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved December 17, 2009. Filipinos make up over a third of the entire population of the Northern Marianas Islands, an American territory in the North Pacific Ocean, and a large proportion of the populations of Guam, Palau, the British Indian Ocean Territory, and Sabah.

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. The majority of Filipinos today come from various Austronesian ethnolinguistic groups, all typically speaking either Filipino

Filipino may refer to:

* Something from or related to the Philippines

** Filipino language, standardized variety of 'Tagalog', the national language and one of the official languages of the Philippines.

** Filipinos, people who are citizens of th ...

, English and/or other Philippine languages

The Philippine languages or Philippinic are a proposed group by R. David Paul Zorc (1986) and Robert Blust (1991; 2005; 2019) that include all the languages of the Philippines and northern Sulawesi, Indonesia—except Sama–Bajaw (languag ...

. Currently, there are more than 185 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines; each with its own language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

, identity, culture and history.

Names

The name ''Filipino'', as a demonym, was derived from the term ''Las Islas Filipinas'' ("the Philippine Islands"), the name given to the archipelago in 1543 by the Spanish explorer and Dominican priestRuy López de Villalobos

Ruy López de Villalobos (; ca. 1500 – April 4, 1546) was a Spanish explorer who sailed the Pacific from Mexico to establish a permanent foothold for Spain in the East Indies, which was near the Line of Demarcation between Spain and Portugal a ...

, in honor of Philip II of Spain (Spanish: ''Felipe II''). During the Spanish colonial period, natives of the Philippine islands were usually known by the generic terms ''indio'' (" Indian") or ''indigenta'' ("indigents"). However, during the early Spanish colonial period the term ''Filipinos'' or ''Philipinos'' was sometimes used by Spanish writers to distinguish the ''indio'' natives of the Philippine archipelago from the ''indios'' of the Spanish colonies in other parts of the world. The term ''Indio Filipino'' appears as a term of self-identification beginning in the 18th century.

In 1955, Agnes Newton Keith wrote that a 19th-century edict prohibited the use of the word "Filipino" to refer to indios. This reflected popular belief, although no such edict has been found. The idea that the term ''Filipino'' was not used to refer to ''indios'' until the 19th century has also been mentioned by historians such as Salah Jubair and Renato Constantino

Renato Constantino (March 10, 1919 – September 15, 1999) was a Filipino historian known for being part of the leftist tradition of Philippine historiography. Apart from being a historian, Constantino was also engaged in foreign service, working ...

. However, in a 1994 publication the historian William Henry Scott identified instances in Spanish writing where "Filipino" did refer to "indio" natives. Instances of such usage include the ''Relación de las Islas Filipinas'' (1604) of Pedro Chirino, in which he wrote chapters entitled "Of the civilities, terms of courtesy, and good breeding among the Filipinos" (Chapter XVI), "Of the Letters of the Filipinos" (Chapter XVII), "Concerning the false heathen religion, idolatries, and superstitions of the Filipinos" (Chapter XXI), "Of marriages, dowries, and divorces among the Filipinos" (Chapter XXX), while also using the term "Filipino" to refer unequivocally to the non-Spaniard natives of the archipelago like in the following sentence:

In the ''Crónicas'' (1738) of Juan Francisco de San Antonio, the author devoted a chapter to "The Letters, languages and politeness of the Philippinos", while Francisco Antolín argued in 1789 that "the ancient wealth of the Philippinos is much like that which the Igorots have at present". These examples prompted the historian William Henry Scott to conclude that during the Spanish colonial period:

While the Philippine-born Spaniards during the 19th century began to be called ''españoles filipinos'', logically contracted to just ''Filipino'', to distinguish them from the Spaniards born in Spain, they themselves resented the term, preferring to identify themselves as ''"hijo/s del país"'' ("sons of the country").

In the latter half of the 19th century, '' illustrados'', an educated class of ''mestizos

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though thei ...

'' (both Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

mestizos

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though thei ...

and Sangley Chinese mestizos

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though thei ...

, especially Chinese mestizos) and ''indios'' arose whose writings are credited with building Philippine nationalism

Filipino nationalism refers to the establishment and support of a political identity associated with the modern nation-state of the Philippines, leading to a wide-ranging campaign for political, social, and economic freedom in the Philippines. ...

. These writings are also credited with transforming the term ''Filipino'' to one which refers to everyone born in the Philippines, especially during the Philippine Revolution and American Colonial Era and the term shifting from a geographic designation to a national one as a citizenship nationality by law. Historian Ambeth Ocampo

Ambeth R. Ocampo (born 1961 in Manila) is a Filipino public historian, academic, cultural administrator, journalist, author, and independent curator. He is best known for his definitive writings about Philippines' national hero José Rizal and o ...

has suggested that the first documented use of the word ''Filipino'' to refer to Indios was the Spanish-language poem ''A la juventud filipina

''A la juventud filipina'' (English Translation: ''To The Philippine Youth)'' is a poem written in Spanish language, Spanish by Filipino people, Filipino writer and patriot José Rizal, first presented in 1879 in Manila, while he was studying at ...

'', published in 1879 by José Rizal. Writer and publisher Nick Joaquin

Nicomedes "Nick" Marquez Joaquin (; May 4, 1917 – April 29, 2004) was a Filipino writer and journalist best known for his short stories and novels in the English language. He also wrote using the pen name Quijano de Manila. Joaquin was conferr ...

has asserted that Luis Rodríguez Varela was the first to describe himself as ''Filipino'' in print. Apolinario Mabini (1896) used the term ''Filipino'' to refer to all inhabitants of the Philippines. Father Jose Burgos earlier called all natives of the archipelago as ''Filipinos''. In Wenceslao Retaña's ''Diccionario de filipinismos'', he defined ''Filipinos'' as follows,

American authorities during the American Colonial Era also started to colloquially use the term ''Filipino'' to refer to the native inhabitants of the archipelago, but despite this, it became the official term for all citizens of the sovereign independent Republic of the Philippines, including non-native inhabitants of the country as per the Philippine Nationality Law

Philippine nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of the Philippines. The two primary pieces of legislation governing these requirements are the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines and the 1939 Revised Naturali ...

. However, the term has been rejected as an identification in some instances by minorities who did not come under Spanish control, such as the Igorot and Muslim Moros

In Greek mythology, Moros /ˈmɔːrɒs/ or Morus /ˈmɔːrəs/ (Ancient Greek: Μόρος means 'doom, fate') is the 'hateful' personified spirit of impending doom, who drives mortals to their deadly fate. It was also said that Moros gave peop ...

.

The lack of the letter "''F''" in the 1940-1987 standardized Tagalog alphabet ( Abakada) caused the letter "''P''" to be substituted for "''F''", though the alphabets and/or writing scripts of some non-Tagalog ethnic groups included the letter "F". Upon official adoption of the modern, 28-letter Filipino

Filipino may refer to:

* Something from or related to the Philippines

** Filipino language, standardized variety of 'Tagalog', the national language and one of the official languages of the Philippines.

** Filipinos, people who are citizens of th ...

alphabet in 1987, the term ''Filipino'' was preferred over ''Pilipino''. Locally, some still use "Pilipino" to refer to the people and "Filipino" to refer to the language, but in international use "Filipino" is the usual form for both.

A number of Filipinos refer to themselves colloquially as "'' Pinoy''" (feminine: "''Pinay''"), which is a slang word formed by taking the last four letters of "''Filipino''" and adding the diminutive suffix "''-y''".

In 2020, the neologism ''Filipinx'' appeared; a demonym applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora and specifically referring to and coined by Filipino-Americans imitating ''Latinx

''Latinx'' is a neologism in American English which is used to refer to people of Latin American cultural or ethnic identity in the United States. The gender-neutral suffix replaces the ending of ''Latino'' and ''Latina'' that are typical o ...

'', itself a recently coined gender-inclusive alternative to ''Latino'' or ''Latina''. An online dictionary made an entry of the term, applying it to all Filipinos within the Philippines or in the diaspora. In actual practice, however, the term is unknown among and not applied to Filipinos living in the Philippines, and ''Filipino'' itself is already treated as gender-neutral. The dictionary entry resulted in confusion, backlash and ridicule from Filipinos residing in the Philippines who never identified themselves with the foreign term.

Native Filipinos were also called Manilamen (or Manila men) or Tagalas by English-speaking regions during the colonial era. They were mostly sailors and pearl-divers and established communities in various ports around the world. One of the notable settlements of Manilamen is the community of Saint Malo, Louisiana

Saint Malo () was a small fishing village that existed along the shore of Lake Borgne in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana as early as the mid-eighteenth century until it was destroyed by the 1915 New Orleans hurricane. Located along Bayou Saint Malo ...

, founded at around 1763 to 1765 by escaped slaves and deserters from the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

. There were also significant numbers of Manilamen in Northern Australia

The unofficial geographic term Northern Australia includes those parts of Queensland and Western Australia north of latitude 26° and all of the Northern Territory. Those local government areas of Western Australia and Queensland that lie p ...

and the Torres Strait Islands in the late 1800s who were employed in the pearl hunting industries.

In Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

(especially in the Mexican states of Guerrero

Guerrero is one of the 32 states that comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 81 municipalities and its capital city is Chilpancingo and its largest city is Acapulcocopied from article, GuerreroAs of 2020, Guerrero the pop ...

and Colima

Colima (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Colima ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Colima), is one of the 31 states that make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It shares its name with its capital and main city, Colima.

Colima i ...

), Filipino immigrants arriving to New Spain during the 16th and 17th centuries via the Manila galleon

fil, Galyon ng Maynila

, english_name = Manila Galleon

, duration = From 1565 to 1815 (250 years)

, venue = Between Manila and Acapulco

, location = New Spain (Spanish Empire ...

s were called ''chino'', which led to the confusion of early Filipino immigrants with that of the much later Chinese immigrants to Mexico from the 1880s to the 1940s. A genetic study in 2018 has also revealed that around one-third of the population of Guerrero have 10% Filipino ancestry.

History

Prehistory

The oldestarchaic human

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

remains in the Philippines are the " Callao Man" specimens discovered in 2007 in the Callao Cave in Northern Luzon. They were dated in 2010 through uranium-series dating to the Late Pleistocene, c. 67,000 years old. The remains were initially identified as modern human, but after the discovery of more specimens in 2019, they have been reclassified as being members of a new species - ''Homo luzonensis

''Homo luzonensis'', also locally called "Ubag" after a mythical caveman, is an extinct, possibly pygmy peoples, pygmy, species of archaic human from the Late Pleistocene of Luzon, the Philippines. Their remains, teeth and phalanges, are known on ...

''.

The oldest indisputable modern human ('' Homo sapiens'') remains in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

are the "Tabon Man

Tabon Man refers to remains discovered in the Tabon Caves in Lipuun Point in Quezon, Palawan in the Philippines. They were discovered by Robert B. Fox, an American anthropologist of the National Museum of the Philippines, on May 28, 1962. The ...

" fossils discovered in the Tabon Caves in the 1960s by Robert B. Fox, an anthropologist from the National Museum. These were dated to the Paleolithic, at around 26,000 to 24,000 years ago. The Tabon Cave complex also indicates that the caves were inhabited by humans continuously from at least 47,000 ± 11,000 years ago to around 9,000 years ago. The caves were also later used as a burial site by unrelated Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

and Metal Age cultures in the area.

Niah Cave

Niah National Park, located within Miri Division, Sarawak, Malaysia, is the site of the Niah Caves limestone cave and archeological site.

History

Alfred Russel Wallace lived for 8 months at Simunjan District with a mining engineer, Robert Co ...

remains of Borneo and the Tam Pa Ling remains of Laos) are part of the "First Sundaland People", the earliest branch of anatomically modern humans

Early modern human (EMH) or anatomically modern human (AMH) are terms used to distinguish '' Homo sapiens'' (the only extant Hominina species) that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from exti ...

to reach Island Southeast Asia via the Sundaland land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

. They entered the Philippines from Borneo via Palawan

Palawan (), officially the Province of Palawan ( cyo, Probinsya i'ang Palawan; tl, Lalawigan ng Palawan), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in t ...

at around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. Their descendants are collectively known as the Negrito people

The term Negrito () refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations often described as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples (including the Great Andamanese, the Ong ...

, although they are highly genetically divergent from each other. Philippine Negritos show a high degree of Denisovan Admixture, similar to Papuans

The indigenous peoples of West Papua in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, commonly called Papuans, are Melanesians. There is genetic evidence for two major historical lineages in New Guinea and neighboring islands: a first wave from the Malay Arch ...

and Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

, in contrast to Malaysian and Andamanese Negritos (the Orang Asli). This indicates that Philippine Negritos, Papuans, and Indigenous Australians share a common ancestor that admixed with Denisovans at around 44,000 years ago. Negritos comprise around 0.03% of the total Philippine population today, they include ethnic groups like the Aeta

The Aeta (Ayta ), Agta, or Dumagat, are collective terms for several Filipino indigenous peoples who live in various parts of the island of Luzon in the Philippines. They are considered to be part of the Negrito ethnic groups and share common ...

(including the Agta, Arta, Dumagat, etc.) of Luzon, the Ati of Western Visayas, the Batak of Palawan

Palawan (), officially the Province of Palawan ( cyo, Probinsya i'ang Palawan; tl, Lalawigan ng Palawan), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in t ...

, and the Mamanwa of Mindanao. Today they comprise just 0.03% of the total Philippine population.

After the Negritos, were two early Paleolithic migrations from East Asian (basal Austric

The Austric languages are a proposed language family that includes the Austronesian languages spoken in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Madagascar, as well as the Austroasiatic languages spoken in Mainland Southeast ...

, an ethnic group which includes Austroasiatics) people, they entered the Philippines at around 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, respectively. Like the Negritos, they entered the Philippines via the Sundaland land bridge in the last ice age. They retain partial genetic signals among the Manobo people and the Sama-Bajau people

The Sama-Bajau include several Austronesian ethnic groups of Maritime Southeast Asia. The name collectively refers to related people who usually call themselves the Sama or Samah (formally A'a Sama, "Sama people"); or are known by the exo ...

of Mindanao.

The last wave of prehistoric migrations to reach the Philippines was the Austronesian expansion which started in the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

at around 4,500 to 3,500 years ago, when a branch of Austronesians from Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

(the ancestral Malayo-Polynesian-speakers) migrated to the Batanes Islands and Luzon. They spread quickly throughout the rest of the islands of the Philippines and became the dominant ethnolinguistic group. They admixed with the earlier settlers, resulting in the modern Filipinos - which though predominantly genetically Austronesian still show varying genetic admixture with Negritos (and vice versa for Negrito ethnic groups which show significant Austronesian admixture). Austronesians possessed advanced sailing technologies and colonized the Philippines via sea-borne migration, in contrast to earlier groups. Austronesians from the Philippines also later settled Guam and the other islands of

Austronesians from the Philippines also later settled Guam and the other islands of Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

, and parts of Mainland Southeast Asia. From there, they colonized the rest of Austronesia, which in modern times include Micronesia, coastal New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

, Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology an ...

, Polynesia, and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, in addition to Maritime Southeast Asia and Taiwan.

The connections between the various Austronesian peoples have also been known since the colonial era due to shared material culture and linguistic similarities of various peoples of the islands of the Indo-Pacific, leading to the designation of Austronesians as the "Malay race

The concept of a Malay race was originally proposed by the German physician Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), and classified as a brown race. ''Malay'' is a loose term used in the late 19th century and early 20th century to describe the ...

" (or the " Brown race") during the age of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He ...

. Due to the colonial American education system in the early 20th century, the term "Malay race" is still used incorrectly in the Philippines to refer to the Austronesian peoples, leading to confusion

In medicine, confusion is the quality or state of being bewildered or unclear. The term "acute mental confusion"

with the non-indigenous Melayu people.

Archaic epoch (to 1565)

Since at least the 3rd century, various ethnic groups established several communities. These were formed by the assimilation of various native Philippine kingdoms.South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

n and East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

n people together with the people of the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay Peninsula, traded with Filipinos and introduced Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

and Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

to the native tribes of the Philippines. Most of these people stayed in the Philippines where they were slowly absorbed into local societies.

Many of the ''barangay

A barangay (; abbreviated as Brgy. or Bgy.), historically referred to as barrio (abbreviated as Bo.), is the smallest administrative division in the Philippines and is the native Filipino term for a village, district, or ward. In metropolita ...

'' (tribal municipalities) were, to a varying extent, under the ''de jure'' jurisprudence of one of several neighboring empires, among them the Malay Srivijaya, Javanese Majapahit, Brunei, Malacca, Tamil Chola, Champa and Khmer empires, although ''de facto'' had established their own independent system of rule. Trading links with Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

, Malay Peninsula, Indochina, China, Japan, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

. A thalassocracy had thus emerged based on international trade.

Even scattered barangays, through the development of inter-island and international trade, became more culturally homogeneous by the 4th century. Hindu- Buddhist culture and religion flourished among the noblemen in this era.

In the period between the 7th to the beginning of the 15th centuries, numerous prosperous centers of trade had emerged, including the Kingdom of Namayan

Namayan (Baybayin: Pre-Kudlit: or (''Sapa''), Post-Kudlit: ), also called Sapa,Locsin, Leandro V. and Cecilia Y. Locsin. 1967. ''Oriental Ceramics Discovered in the Philippines.'' Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company. Maysapan or Nasapan, an ...

which flourished alongside Manila Bay, Cebu

Cebu (; ceb, Sugbo), officially the Province of Cebu ( ceb, Lalawigan sa Sugbo; tl, Lalawigan ng Cebu; hil, Kapuroan sang Sugbo), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and 16 ...

, Iloilo

Iloilo (), officially the Province of Iloilo ( hil, Kapuoran sang Iloilo; krj, Kapuoran kang Iloilo; tl, Lalawigan ng Iloilo), is a province in the Philippines located in the Western Visayas region. Its capital is the City of Iloilo, the ...

, Butuan

Butuan (pronounced ), officially the City of Butuan ( ceb, Dakbayan sa Butuan; Butuanon: ''Dakbayan hong Butuan''; fil, Lungsod ng Butuan), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in the region of Caraga, Philippines. It is the ''de facto'' c ...

, the Kingdom of Sanfotsi situated in Pangasinan, the Kingdom of Luzon now known as Pampanga which specialized in trade with most of what is now known as Southeast Asia and with China, Japan and the Kingdom of Ryukyu

The Ryukyu Kingdom, Middle Chinese: , , Classical Chinese: (), Historical English names: ''Lew Chew'', ''Lewchew'', ''Luchu'', and ''Loochoo'', Historical French name: ''Liou-tchou'', Historical Dutch name: ''Lioe-kioe'' was a kingdom in the ...

in Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

.

From the 9th century onwards, a large number of Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

traders from the Middle East settled in the Malay Archipelago and intermarried with the local Malay, Bruneian, Malaysian, Indonesian and Luzon and Visayas indigenous populations.

In the years leading up to 1000 AD, there were already several maritime societies existing in the islands but there was no unifying political state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

encompassing the entire Philippine archipelago. Instead, the region was dotted by numerous semi-autonomous '' barangays'' (settlements ranging is size from villages to city-states) under the sovereignty of competing thalassocracies ruled by datus, rajah

''Raja'' (; from , IAST ') is a royal title used for South Asian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in South Asia and Southeast Asia, being attested fr ...

s or sultans or by upland agricultural societies ruled by "petty plutocrats". States such as the Wangdoms of Ma-i

Ma-i or Maidh (also spelled Ma'I, Mai, Ma-yi or Mayi; Baybayin: ; Hanunoo: ; Hokkien ; Mandarin ) was an ancient sovereign state located in what is now the Philippines.

Its existence was first documented in 971 in the Song dynasty documents ...

and Pangasinan, Kingdom of Maynila

In early Philippine history, the Tagalog Bayan ("country" or "city-state") of Maynila ( tl, Bayan ng Maynila; Pre-virama Baybayin: ) was a major Tagalog city-state on the southern part of the Pasig River delta, where the district of Intramu ...

, Namayan

Namayan (Baybayin: Pre-Kudlit: or (''Sapa''), Post-Kudlit: ), also called Sapa,Locsin, Leandro V. and Cecilia Y. Locsin. 1967. ''Oriental Ceramics Discovered in the Philippines.'' Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company. Maysapan or Nasapan, an ...

, the Kingdom of Tondo

In early Philippine history, the Tagalog settlement at Tondo (; Baybayin: ) was a major trade hub located on the northern part of the Pasig River delta, on Luzon island.Abinales, Patricio N. and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Phi ...

, the Kedatuans of Madja-as and Dapitan, the Rajahnates of Butuan

Butuan (pronounced ), officially the City of Butuan ( ceb, Dakbayan sa Butuan; Butuanon: ''Dakbayan hong Butuan''; fil, Lungsod ng Butuan), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in the region of Caraga, Philippines. It is the ''de facto'' c ...

and Cebu

Cebu (; ceb, Sugbo), officially the Province of Cebu ( ceb, Lalawigan sa Sugbo; tl, Lalawigan ng Cebu; hil, Kapuroan sang Sugbo), is a province of the Philippines located in the Central Visayas region, and consists of a main island and 16 ...

and the sultanates of Maguindanao, Lanao and Sulu existed alongside the highland societies of the Ifugao and Mangyan. Some of these regions were part of the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit and Brunei.

Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Naturales 5.png, Tagalog ''maginoo'', c.1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Visayans 3.png, Visayan

Visayans ( Visayan: ''mga Bisaya''; ) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. When taken as a single ethnic group ...

''kadatuan'', c.1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Naturales 2.png, Native commoner women (likely Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

in Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

at the time), c.1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Visayans 2.png, Visayan

Visayans ( Visayan: ''mga Bisaya''; ) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. When taken as a single ethnic group ...

''timawa'', c.1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Visayans 1.png, Visayan

Visayans ( Visayan: ''mga Bisaya''; ) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. When taken as a single ethnic group ...

''pintados'' (tattooed), c. 1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Naturales 1.png, Visayan

Visayans ( Visayan: ''mga Bisaya''; ) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. When taken as a single ethnic group ...

''uripon'' (slaves), c. 1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Native of Visayan origin.jpg, ''Binukot

Binukot, also spelled Binokot, is a pre-colonial Visayan tradition from the Philippines that secludes a young woman with the expectation that seclusion will result in a higher value placed on the girl by marital suitors in the future. It original ...

'' from Visayas, c. 1590 Boxer Codex

The ''Boxer Codex'' is a late sixteenth century Spanish manuscript that was produced in the Philippines. The document contains seventy-five colored illustrations of the peoples of China, the Philippines, Java, the Moluccas, the Ladrones, and Sia ...

Historic caste systems

Datu – The Tagalog ''maginoo

The Tagalog ''maginoo'', the Kapampangan ''ginu'', and the Visayan ''tumao'' were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the ''tumao'' were further distinguished from the immediate ...

'', the Kapampangan ''ginu'' and the Visayan

Visayans ( Visayan: ''mga Bisaya''; ) or Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group or metaethnicity native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao. When taken as a single ethnic group ...

''tumao'' were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the tumao were further distinguished from the immediate royal families or a ruling class.

Timawa – The timawa class were free commoners of Luzon and the Visayas who could own their own land and who did not have to pay a regular tribute to a maginoo, though they would, from time to time, be obliged to work on a datu's land and help in community projects and events. They were free to change their allegiance to another datu if they married into another community or if they decided to move.

Maharlika – Members of the Tagalog warrior class known as maharlika had the same rights and responsibilities as the timawa, but in times of war they were bound to serve their datu in battle. They had to arm themselves at their own expense, but they did get to keep the loot they took. Although they were partly related to the nobility, the maharlikas were technically less free than the timawas because they could not leave a datu's service without first hosting a large public feast and paying the datu between 6 and 18 pesos in gold – a large sum in those days.

Alipin – Commonly described as "servant" or "slave". However, this is inaccurate. The concept of the alipin relied on a complex system of obligation and repayment through labor in ancient Philippine society, rather than on the actual purchase of a person as in Western and Islamic slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Members of the alipin class who owned their own houses were more accurately equivalent to medieval European serfs and commoners.

By the 15th century, Arab and Indian missionaries and traders from Malaysia and Indonesia brought Islam to the Philippines, where it both replaced and was practiced together with indigenous religions. Before that, indigenous tribes of the Philippines practiced a mixture of Animism, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

and Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

. Native villages, called ''barangays'' were populated by locals called Timawa (Middle Class/freemen) and Alipin (servants and slaves). They were ruled by Rajah

''Raja'' (; from , IAST ') is a royal title used for South Asian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in South Asia and Southeast Asia, being attested fr ...

s, Datus and Sultans, a class called Maginoo

The Tagalog ''maginoo'', the Kapampangan ''ginu'', and the Visayan ''tumao'' were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the ''tumao'' were further distinguished from the immediate ...

(royals) and defended by the Maharlika (Lesser nobles, royal warriors and aristocrats). These Royals and Nobles are descended from native Filipinos with varying degrees of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian, which is evident in today's DNA analysis among South East Asian Royals. This tradition continued among the Spanish and Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

traders who also intermarried with the local populations.

Hispanic settlement and rule (1521–1898)

The Philippines was settled by the

The Philippines was settled by the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

. The arrival of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

( pt, Fernão de Magalhães, italic=no) in 1521 began a period of European colonization. During the period of Spanish colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

, the Philippines was part of the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

alty of New Spain, which was governed and administered from Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital city, capital and primate city, largest city of Mexico, and the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North Amer ...

. Early Spanish settlers were mostly explorers, soldiers, government officials and religious missionaries born in Spain and Mexico. Most Spaniards who settled were of Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

ancestry, but there were also settlers of Andalusian, Catalan, and Moorish descent. The ''Peninsulares'' (governors born in Spain), mostly of Castilian ancestry, settled in the islands to govern their territory. Most settlers married the daughters of rajah

''Raja'' (; from , IAST ') is a royal title used for South Asian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in South Asia and Southeast Asia, being attested fr ...

s, datus and sultans to reinforce the colonization of the islands. The ''Ginoo'' and ''Maharlika'' castes (royals and nobles) in the Philippines prior to the arrival of the Spanish formed the privileged ''Principalía

The ''principalía'' or noble class was the ruling and usually educated upper class in the ''pueblos'' of Spanish Philippines, comprising the ''gobernadorcillo'' (later called the c''apitán municipal'' and had functions similar to a town mayo ...

'' (nobility) during the early Spanish period.

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines, especially through the commencement of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade that connected the

The arrival of the Spaniards to the Philippines, especially through the commencement of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade that connected the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

through Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

to Acapulco in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, attracted new waves of immigrants from China, as Manila was already previously connected to the Maritime Silk Road

The Maritime Silk Road or Maritime Silk Route is the Maritime history, maritime section of the historic Silk Road that connected Southeast Asia, China, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian peninsula, Somalia, Egypt and Europe. It began by the 2n ...

and Maritime Jade Road, as shown in the Selden Map, from Quanzhou and/or Zhangzhou in Southern Fujian

Minnan, Banlam or Minnan Golden Triangle (), refers to the coastal region in Southern Fujian Province, China, which includes the prefecture-level cities of Xiamen, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. The region accounts for 40 percent of the GDP of Fujian Pro ...

to Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, maritime trade flourished during the Spanish period, especially as Manila was connected to the ports of Southern Fujian

Minnan, Banlam or Minnan Golden Triangle (), refers to the coastal region in Southern Fujian Province, China, which includes the prefecture-level cities of Xiamen, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. The region accounts for 40 percent of the GDP of Fujian Pro ...

, such as Yuegang (the old port of Haicheng in Zhangzhou, Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its cap ...

). The Spanish recruited thousands of Chinese migrant workers from "''Chinchew''" ( Quanzhou), "''Chiõ Chiu''" ( Zhangzhou), "''Canton''" (Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

), and Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a p ...

called '' sangleys'' (from Hokkien ) to build the colonial infrastructure in the islands. Many Chinese immigrants converted to Christianity, intermarried with the locals, and adopted Hispanized names and customs and became assimilated, although the children of unions between Filipinos and Chinese that became assimilated continued to be designated in official records as '' mestizos de sangley''. The Chinese mestizos were largely confined to the Binondo area until the 19th century. However, they eventually spread all over the islands and became traders, landowners and moneylenders. Today, their descendants still comprise a significant part of the Philippine population especially its bourgeois, who during the late Spanish Colonial Era in the late 19th century, produced a major part of the ''ilustrado

The Ilustrados (, "erudite", "learned" or "enlightened ones") constituted the Filipino educated class during the Spanish colonial period in the late 19th century. Elsewhere in New Spain (of which the Philippines were part), the term ''gente de ...

'' intelligentsia of the late Spanish Colonial Philippines, that were very influential with the creation of Filipino nationalism

Filipino nationalism refers to the establishment and support of a political identity associated with the modern nation-state of the Philippines, leading to a wide-ranging campaign for political, social, and economic freedom in the Philippines. ...

and the sparking of the Philippine Revolution as part of the foundation of the First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Republic ( es, República Filipina), now officially known as the First Philippine Republic, also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was established in Malolos, Bulacan during the Philippine Revolution against ...

and subsequent sovereign independent Philippines