Tzfat cheese.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Safed (known in

accessed 9 December 2016 Safed is mentioned in the

''Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered,''

Random House, 2013 p. 190. In the estimation of modern historian Havré Barbé, the ''castellany'' of Safed comprised approximately . According to Barbé, its western boundary straddled the domains of Acre, including the fief of St. George de la Beyne, which included

152

/ref> Saladin ultimately allowed its residents to relocate to Tyre. He granted Safed and Tiberias as an ''

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the Mamluks in 1250 and the Mamluk sultan Baybars entered Syria with his army in 1261. Thereafter, he led a series of campaigns over several years against Crusader strongholds across the Syrian coastal mountains. Safed, with its position overlooking the Jordan River and allowing the Crusaders early warnings of Muslim troop movements in the area, had been a consistent aggravation for the Muslim regional powers. After a six-week siege,Luz 2014, p. 35. Baybars captured Safed in July 1266, after which he had nearly the entire garrison killed.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 758. The siege occurred during a Mamluk military campaign to subdue Crusader strongholds in Palestine and followed a failed attempt to capture the Crusaders' coastal stronghold of Acre. Unlike the Crusader fortresses along the coastline, which were demolished upon their capture by the Mamluks, Baybars spared the fortress of Safed.Drory 2004, p. 165. He likely preserved it because of the strategic value stemming from its location on a high mountain and its isolation from other Crusader fortresses. Moreover, Baybars determined that in the event of a renewed Crusader invasion of the coastal region, a strongly fortified Safed could serve as an ideal headquarters to confront the Crusader threat. In 1268, he had the fortress repaired, expanded and strengthened. He commissioned numerous building works in the town of Safed, including caravanserais, markets and baths, and converted the town's church into a mosque.Drory 2004, p. 166. The mosque, called Jami al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), was completed in 1275. By the end of Baybars's reign, Safed had developed into a prosperous town and fortress.

Baybars assigned fifty-four

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the Mamluks in 1250 and the Mamluk sultan Baybars entered Syria with his army in 1261. Thereafter, he led a series of campaigns over several years against Crusader strongholds across the Syrian coastal mountains. Safed, with its position overlooking the Jordan River and allowing the Crusaders early warnings of Muslim troop movements in the area, had been a consistent aggravation for the Muslim regional powers. After a six-week siege,Luz 2014, p. 35. Baybars captured Safed in July 1266, after which he had nearly the entire garrison killed.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 758. The siege occurred during a Mamluk military campaign to subdue Crusader strongholds in Palestine and followed a failed attempt to capture the Crusaders' coastal stronghold of Acre. Unlike the Crusader fortresses along the coastline, which were demolished upon their capture by the Mamluks, Baybars spared the fortress of Safed.Drory 2004, p. 165. He likely preserved it because of the strategic value stemming from its location on a high mountain and its isolation from other Crusader fortresses. Moreover, Baybars determined that in the event of a renewed Crusader invasion of the coastal region, a strongly fortified Safed could serve as an ideal headquarters to confront the Crusader threat. In 1268, he had the fortress repaired, expanded and strengthened. He commissioned numerous building works in the town of Safed, including caravanserais, markets and baths, and converted the town's church into a mosque.Drory 2004, p. 166. The mosque, called Jami al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), was completed in 1275. By the end of Baybars's reign, Safed had developed into a prosperous town and fortress.

Baybars assigned fifty-four

xii

/ref> one of seven ''mamlakas'' (provinces), whose governors were typically appointed from The geographer

The geographer

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the

pp. 95–96

/ref> In 1553/54, the population consisted of 1,121 Muslim households, 222 Muslim bachelors, 54 Muslim religious leaders, 716 Jewish households, 56 Jewish bachelors, and 9 disabled persons. At least in the 16th century, Safed was the only ''kasaba'' (city) in the sanjak and in 1555 was divided into nineteen ''mahallas'' (quarters), seven Muslim and twelve Jewish.Rhode 1979, p. 34. The total population of Safed rose from 926 households in 1525–26 to 1,931 households in 1567–1568. Among these, the Jewish population rose from a mere 233 households in 1525 to 945 households in 1567–1568.Petersen (2001), Gazetteer 6, s,v

Ṣafad

/ref> The Muslim quarters were Sawawin, located west of the fortress; Khandaq (the moat); Ghazzawiyah, which had likely been settled by Gazans; Jami' al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), located south of the fortress and named for the local mosque; al-Akrad, which dated to the Middle Ages and continued to exist through the 19th century,Ebied and Young 1976, p. 7. and whose inhabitants were mostly In the 15th and 16th centuries there were a number of well-known Sufi (Muslim mysticism) followers of

In the 15th and 16th centuries there were a number of well-known Sufi (Muslim mysticism) followers of

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602 the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon,

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602 the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon,

256

destroyed all fourteen of its synagogues and prompted the flight of 600

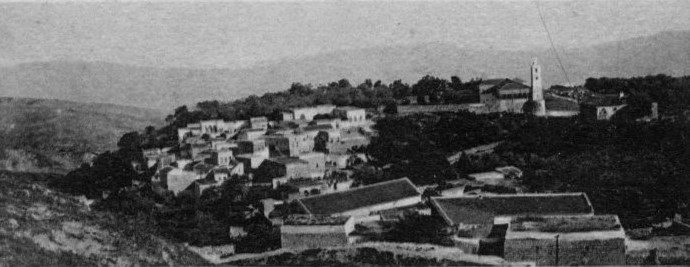

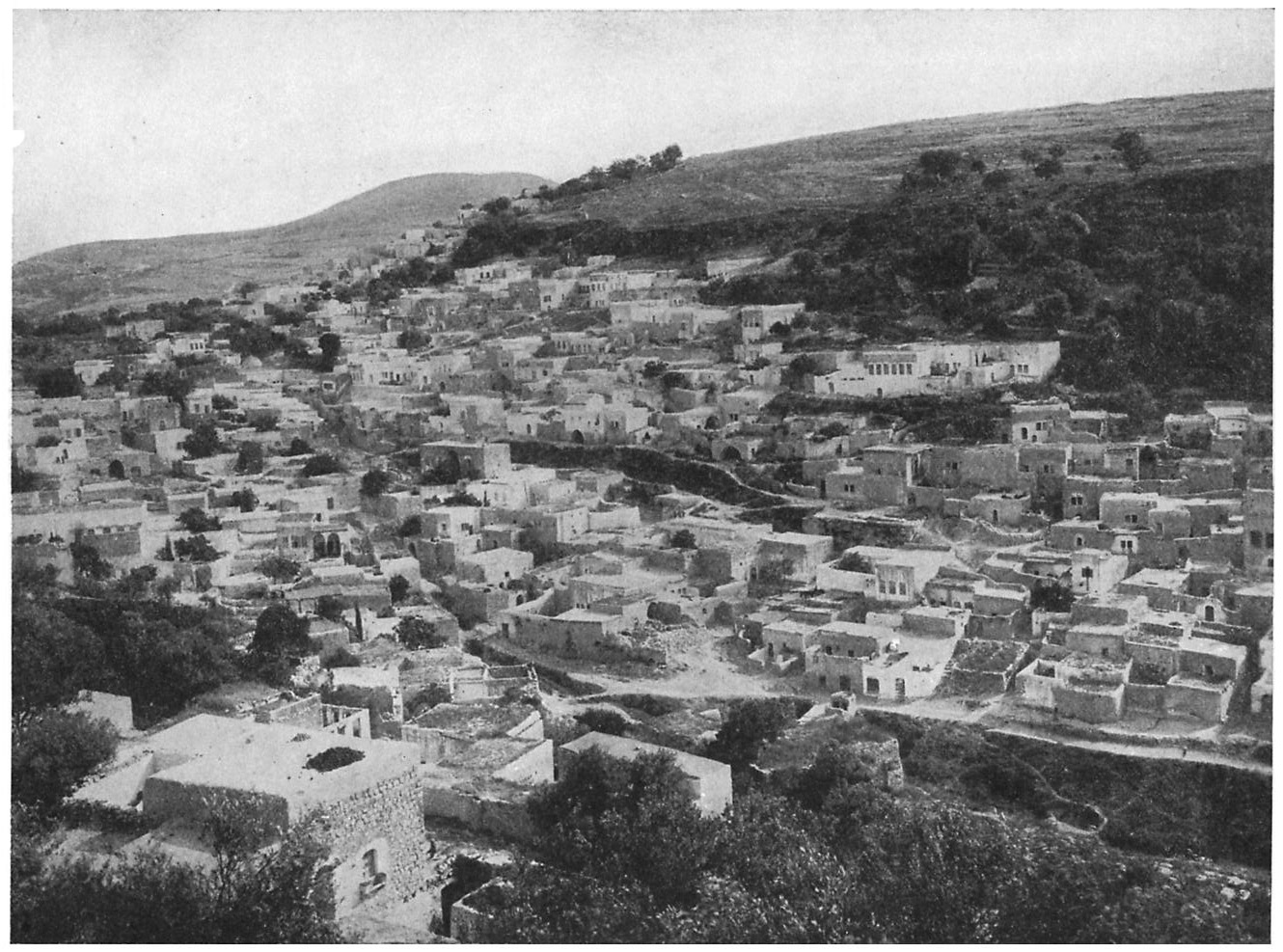

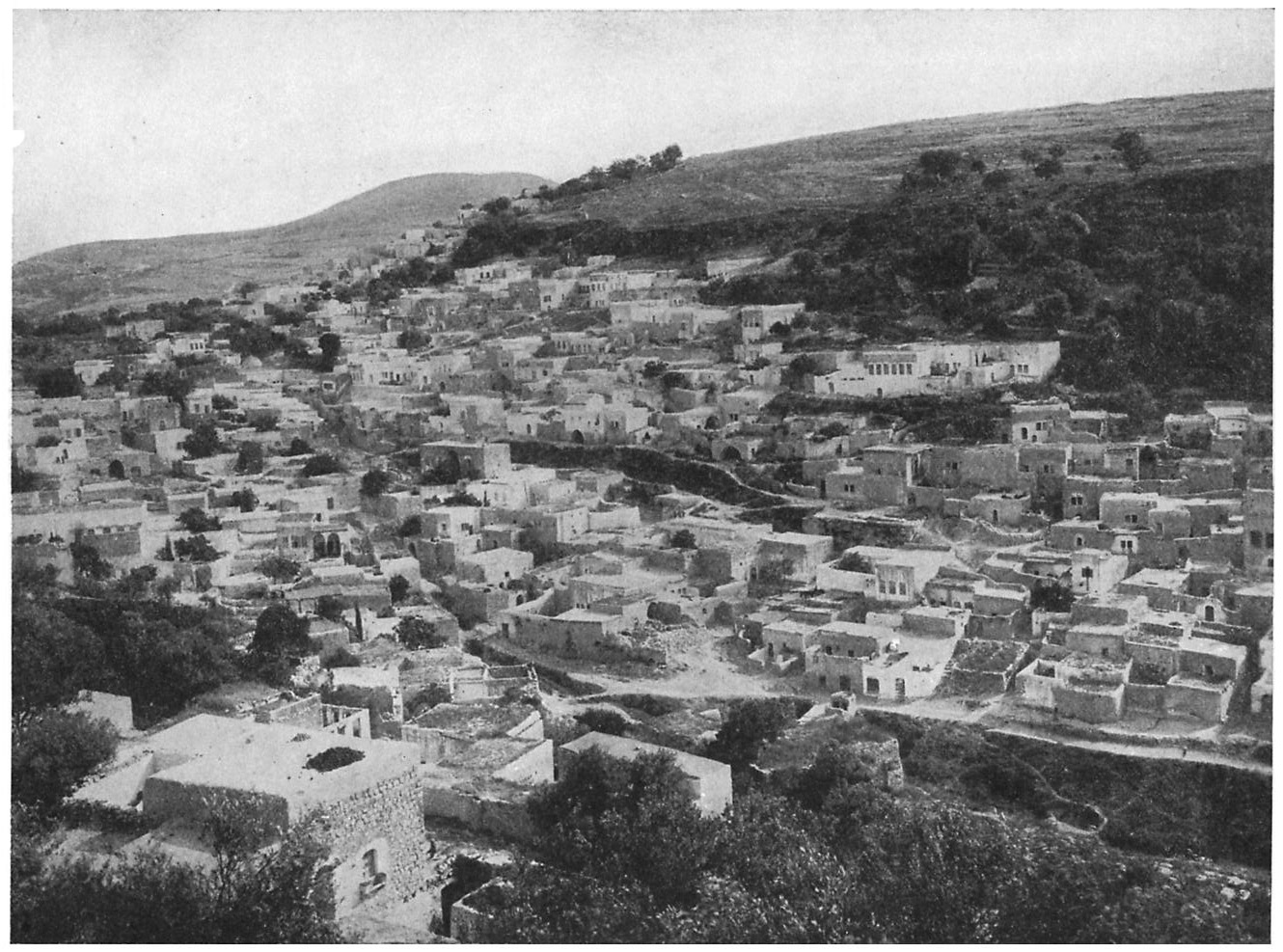

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide Tanzimat reforms, which were first adopted in the 1840s, brought about a steady rise in Safed's population and economy. In 1849 Safed had a total estimated population of 5,000, of whom 2,940-3,440 were Muslims, 1,500-2,000 were Jews and 60 were Christians.Abbasi 2003, p. 52. The population was estimated at 7,000 in 1850–1855, of whom 2,500-3,000 were Jews. The Jewish population increased in the last half of the 19th century by immigration from

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide Tanzimat reforms, which were first adopted in the 1840s, brought about a steady rise in Safed's population and economy. In 1849 Safed had a total estimated population of 5,000, of whom 2,940-3,440 were Muslims, 1,500-2,000 were Jews and 60 were Christians.Abbasi 2003, p. 52. The population was estimated at 7,000 in 1850–1855, of whom 2,500-3,000 were Jews. The Jewish population increased in the last half of the 19th century by immigration from  In 1878 the municipal council of Safed was established. In 1888 the Acre Sanjak, including the Safed Kaza, became part of the new province of Beirut Vilayet, an administrative state of affairs which persisted until the Empire's fall in 1918. The centralization and stability brought by the imperial reforms solidified the political status and practical influence of Safed in the Upper Galilee.Abbasi 2003, p. 51. The Ottomans developed Safed into a center for Sunni Islam to counterbalance the influence of non-Muslim communities in its environs and the Shia Muslims of Jabal Amil.Abbasi 2003, p. 53. Along with the three major landowning families, the Muslim ''ulema'' (religious scholarly) families of Nahawi, Qadi, Mufti and Naqib comprised the urban elite (''a'yan'') of the city. The Sunni courts of Safed arbitrated over cases in Akbara, Ein al-Zeitun and as far away as Mejdel Islim. The government settled Algerian and Circassian exiles in the countryside of Safed in the 1860s and 1878, respectively, possibly in an effort to strengthen the Muslim character of the area. At least two Muslim families in the city itself, Arabi and Delasi, were of Algerian origin, though they accounted for a small proportion of the city's overall Muslim population. According to the late 19th-century account of British missionary E. W. G. Masterman, the Muslim families of Safed originated from Damascus, Transjordan and the villages around Safed. When Baybars conquered Safed in 1266 he settled many Damascenes in the city. Until the late 19th century the Muslims of Safed maintained strong social and cultural connections with Damascus. Masterman noted that the Muslims of Safed were conservative, "active and hardy", who "dress dwell and move about more than the people from the region of southern Palestine". They lived mainly in three quarters of the city: al-Akrad, whose residents were mostly laborers, Sawawin, home to the Muslim ''a'yan'' households and the city's Catholic community, and al-Wata, whose inhabitants were largely shopkeepers and minor traders.Schumacher, 1888, p

In 1878 the municipal council of Safed was established. In 1888 the Acre Sanjak, including the Safed Kaza, became part of the new province of Beirut Vilayet, an administrative state of affairs which persisted until the Empire's fall in 1918. The centralization and stability brought by the imperial reforms solidified the political status and practical influence of Safed in the Upper Galilee.Abbasi 2003, p. 51. The Ottomans developed Safed into a center for Sunni Islam to counterbalance the influence of non-Muslim communities in its environs and the Shia Muslims of Jabal Amil.Abbasi 2003, p. 53. Along with the three major landowning families, the Muslim ''ulema'' (religious scholarly) families of Nahawi, Qadi, Mufti and Naqib comprised the urban elite (''a'yan'') of the city. The Sunni courts of Safed arbitrated over cases in Akbara, Ein al-Zeitun and as far away as Mejdel Islim. The government settled Algerian and Circassian exiles in the countryside of Safed in the 1860s and 1878, respectively, possibly in an effort to strengthen the Muslim character of the area. At least two Muslim families in the city itself, Arabi and Delasi, were of Algerian origin, though they accounted for a small proportion of the city's overall Muslim population. According to the late 19th-century account of British missionary E. W. G. Masterman, the Muslim families of Safed originated from Damascus, Transjordan and the villages around Safed. When Baybars conquered Safed in 1266 he settled many Damascenes in the city. Until the late 19th century the Muslims of Safed maintained strong social and cultural connections with Damascus. Masterman noted that the Muslims of Safed were conservative, "active and hardy", who "dress dwell and move about more than the people from the region of southern Palestine". They lived mainly in three quarters of the city: al-Akrad, whose residents were mostly laborers, Sawawin, home to the Muslim ''a'yan'' households and the city's Catholic community, and al-Wata, whose inhabitants were largely shopkeepers and minor traders.Schumacher, 1888, p

188

/ref> The entire Jewish population lived in the Gharbieh (western) quarter. Safed's population reached over 15,000 in 1879, 8,000 of whom were Muslims and 7,000 Jews. A population list from about 1887 showed that Safad had 24,615 inhabitants; 2,650 Jewish households, 2,129 Muslim households and 144 Roman Catholic households. Arab families in Safed whose social status rose as a result of the Tanzimat reforms included the Asadi, whose presence in Safed dated to the 16th century, Hajj Sa'id, Hijazi, Bisht, Hadid, Khouri, a Christian family whose progenitor moved to the city from Mount Lebanon during the 1860 civil war, and Sabbagh, a long-established Christian family in the city related to Zahir al-Umar's fiscal adviser Ibrahim al-Sabbagh; many members of these families became officials in the civil service, local administrations or businessmen. When the Ottomans established a branch of the Agricultural Bank in the city in 1897, all of its board members were resident Arabs, the most influential of whom were Husayn Abd al-Rahim Effendi, Hajj Ahmad al-Asadi, As'ad Khouri and Abd al-Latif al-Hajj Sa'id. The latter two also became board members of the Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture branch opened in Safed in 1900. In the last decade of the 19th century, Safed contained 2,000 houses, four mosques, three churches, two public bathhouses, one caravanserai, two public '' sabils'', nineteen mills, seven olive oil presses, ten bakeries, fifteen coffeehouses, forty-five stalls and three shops.

6

/ref> Safed remained a mixed city during the British Mandate for Palestine and ethnic tensions between Jews and Arabs rose during the 1920s. During the 1929 Palestine riots, Safed and Hebron became major clash points. In the Safed massacre 20 Jewish residents were killed by local Arabs. Safed was included in the part of Palestine recommended to be included in the proposed Jewish state under the

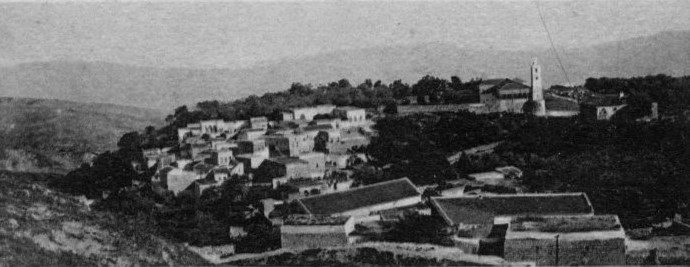

File:Zoltan Kluger. Safed.jpg, Safad 1937

File:Safed iv.jpg, Mandate Police station at Mount Canaan, above Safed (1948)

File:Safed 1948.jpg, Safed (1948)

File:Safed citadel.jpg, Safed Citadel (1948)

File:Safad v.jpg, Safad Municipal Police Station after the battle (1948)

File:Safad i.jpg, Bussel House, Safad, 11 April 1948:

According to CBS, the city has 25 schools and 6,292 students. There are 18 elementary schools with a student population of 3,965, and 11 high schools with a student population of 2,327. 40.8% of Safed's 12th graders were eligible for a matriculation (

According to CBS, the city has 25 schools and 6,292 students. There are 18 elementary schools with a student population of 3,965, and 11 high schools with a student population of 2,327. 40.8% of Safed's 12th graders were eligible for a matriculation (

;Artists' colony

In the 1950s and 1960s, Safed was known as Israel's art capital. An artists' colony established in the old Arab quarter was a hub of creativity that drew artists from around the country, among them

;Artists' colony

In the 1950s and 1960s, Safed was known as Israel's art capital. An artists' colony established in the old Arab quarter was a hub of creativity that drew artists from around the country, among them

access date: 24/1/2018

/ref> ;Music In the 1960s, Safed was home to the country's top nightclubs, hosting the debut performances of

;Citadel Hill

The Citadel Hill, in Hebrew HaMetzuda, rises east of the Old City and is named after the huge Crusader and then Mamluk castle built there during the 12th and 13th centuries, which continued in use until being totally destroyed by the 1837 earthquake. Its ruins are still visible. On the western slope beneath the ruins stands the former British police station, still pockmarked by bullet holes from the 1948 war.

;Old Jewish Quarter

Before 1948, most of Safed's Jewish population used to live in the northern section of the old city. Currently home to 32 synagogues, it is also referred to as the synagogue quarter and includes synagogues named after prominent rabbis of the town: the Abuhav, Alsheich, Karo and two named for Rabbi

;Citadel Hill

The Citadel Hill, in Hebrew HaMetzuda, rises east of the Old City and is named after the huge Crusader and then Mamluk castle built there during the 12th and 13th centuries, which continued in use until being totally destroyed by the 1837 earthquake. Its ruins are still visible. On the western slope beneath the ruins stands the former British police station, still pockmarked by bullet holes from the 1948 war.

;Old Jewish Quarter

Before 1948, most of Safed's Jewish population used to live in the northern section of the old city. Currently home to 32 synagogues, it is also referred to as the synagogue quarter and includes synagogues named after prominent rabbis of the town: the Abuhav, Alsheich, Karo and two named for Rabbi

File:Meron 181.jpg, Monument to the Israeli soldiers who fought in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

File:Safed 2009.jpg, Safed in 2009

File:Safed view 02.JPG, View of Safed

File:Safed view 01.jpg, View of Safed

File:Safed 01.JPG, Houses in Safed

File:SafedDSCN4022.JPG, Doorway in Beit Castel gallery, Safed

City Council websitezefat.net

Nefesh B' Nefesh Community Guide for Tzfat

* Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4

IAAWikimedia commons

Safed on the PEF Map {{Authority control Holy cities Cities in Northern District (Israel) Jewish pilgrimage sites Crusader castles Castles and fortifications of the Kingdom of Jerusalem Castles and fortifications of the Knights Templar Castles in Israel Ancient Jewish settlements of Galilee Ottoman clock towers Clock towers in Israel Holy cities of Judaism

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew

Sephardi Hebrew (or Sepharadi Hebrew; he, עברית ספרדית, Ivrit S'faradít, lad, Hebreo Sefardíes) is the pronunciation system for Biblical Hebrew favored for liturgical use by Sephardi Jewish practice. Its phonology was influenced by ...

& Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew ( he, עברית חדשה, ''ʿivrít ḥadašá ', , '' lit.'' "Modern Hebrew" or "New Hebrew"), also known as Israeli Hebrew or Israeli, and generally referred to by speakers simply as Hebrew ( ), is the standard form of the H ...

: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew

Ashkenazi Hebrew ( he, הגייה אשכנזית, Hagiyya Ashkenazit, yi, אַשכּנזישע הבֿרה, Ashkenazishe Havara) is the pronunciation system for Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew favored for Jewish liturgical use and Torah study by Ash ...

: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. Located at an elevation of , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with ''Sepph,'' a fortified town in the Upper Galilee

The Upper Galilee ( he, הגליל העליון, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; ar, الجليل الأعلى, ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical-political term in use since the end of the Second Temple period. It originally referred to a mounta ...

mentioned in the writings of the Roman Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

. The Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud ( he, תַּלְמוּד יְרוּשַׁלְמִי, translit=Talmud Yerushalmi, often for short), also known as the Palestinian Talmud or Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century ...

mentions Safed as one of five elevated spots where fires were lit to announce the New Moon and festivals during the Second Temple period. Safed attained local prominence under the Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

, who built a large fortress there in 1168. It was conquered by Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

20 years later, and demolished by his grandnephew al-Mu'azzam Isa in 1219. After reverting to the Crusaders in a treaty in 1240, a larger fortress was erected, which was expanded and reinforced in 1268 by the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

sultan Baybars, who developed Safed into a major town and the capital of a new province spanning the Galilee. After a century of general decline, the stability brought by the Ottoman conquest in 1517 ushered in nearly a century of growth and prosperity in Safed, during which time Jewish immigrants from across Europe developed the city into a center for wool and textile production and the mystical Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "receiver"). The defin ...

movement. It became known as one of the Four Holy Cities of Judaism. As the capital of the Safad Sanjak

Safed Sanjak ( ar, سنجق صفد; tr, Safed Sancağı) was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Damascus Eyalet ( Ottoman province of Damascus) in 1517–1660, after which it became part of the Sidon Eyalet (Ottoman province of Sidon). The sanjak was ce ...

, it was the main population center of the Galilee, with large Muslim and Jewish communities.

Besides the fortunate governorship of Fakhr al-Din II

Fakhr al-Din ibn Qurqumaz Ma'n ( ar, فَخْر ٱلدِّين بِن قُرْقُمَاز مَعْن, Fakhr al-Dīn ibn Qurqumaz Maʿn; – March or April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II ( ar, فخر الدين ال ...

in the early 17th century, the city underwent a general decline and was eclipsed by Acre by the mid-18th century. Its Jewish residents were targeted in Druze and local Muslim raids in the 1830s, and most of them perished in an earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, fr ...

in that same decade. Safed's conditions improved considerably in the late 19th century, with its municipal council founded along with a number of banks, though the city's jurisdiction was limited to the Upper Galilee. Its population reached 24,000 toward the end of the century; it was a mixed city, divided roughly equally between Jews and Muslims with a small Christian community. Its Muslim merchants played a key role as middlemen in the grain trade between the local farmers and the traders of Acre, while the Ottomans promoted the city as a center of Sunni jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

. Through the philanthropy of Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, aft ...

, its Jewish synagogues and homes were rebuilt. Around the start of British Mandatory rule, in 1922, Safed's population had dropped to around 8,700, roughly 60% Muslim, 33% Jewish and the remainder Christians. Amid rising ethnic tension throughout Palestine, Safed's Jews were attacked in an Arab riot in 1929. The city's population had risen to 13,700 by 1948, overwhelmingly Arab, though the city was proposed to be part of a Jewish state in the 1947 UN Partition Plan

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as ...

. During the 1948 war, Jewish paramilitary forces captured the city after heavy fighting, precipitating the flight of all of Safed's Palestinian Arabs, such that today the city has an almost exclusively Jewish population.

Safed has a large Haredi

Haredi Judaism ( he, ', ; also spelled ''Charedi'' in English; plural ''Haredim'' or ''Charedim'') consists of groups within Orthodox Judaism that are characterized by their strict adherence to ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions, in oppos ...

community and remains a center for Jewish religious studies. Due to its high elevation, the city has warm summers and cold, often snowy, winters. Its mild climate and scenic views have made Safed a popular holiday resort frequented by Israelis and foreign visitors. In it had a population of .

Biblical reference

Legend has it that Safed was founded by a son of Noah after theGreat Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval ...

. According to the Book of Judges

The Book of Judges (, ') is the seventh book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. In the narrative of the Hebrew Bible, it covers the time between the conquest described in the Book of Joshua and the establishment of a kingdom ...

(), the area where Safed is located was assigned to the tribe of Naphtali

The Tribe of Naphtali () was one of the northernmost of the twelve tribes of Israel. It is one of the ten lost tribes.

Biblical narratives

In the biblical account, following the completion of the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites, Joshua al ...

.

It has been suggested that Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

' assertion that "a city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden" may have referred to Safed.

History

Antiquity

Safed has been identified with ''Sepph,'' a fortified town in theUpper Galilee

The Upper Galilee ( he, הגליל העליון, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; ar, الجليل الأعلى, ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical-political term in use since the end of the Second Temple period. It originally referred to a mounta ...

mentioned in the writings of the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

.Geography of Israel: Safedaccessed 9 December 2016 Safed is mentioned in the

Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud ( he, תַּלְמוּד יְרוּשַׁלְמִי, translit=Talmud Yerushalmi, often for short), also known as the Palestinian Talmud or Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century ...

as one of five elevated spots where fires were lit to announce the New Moon and festivals during the Second Temple period.

Crusader era

Pre-Crusader village and tower

There is scarce information about Safed before the Crusader conquest.Drory 2004, p. 163. A document from theCairo Geniza

The Cairo Geniza, alternatively spelled Genizah, is a collection of some 400,000 Jewish manuscript fragments and Fatimid administrative documents that were kept in the ''genizah'' or storeroom of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat or Old Cairo, ...

, composed in 1034, mentions a transaction made in Tiberias in 1023 by a certain Jew, Musa ben Hiba ben Salmun with the ''nisba

The Arabic language, Arabic word nisba (; also transcribed as ''nisbah'' or ''nisbat'') may refer to:

* Arabic nouns and adjectives#Nisba, Nisba, a suffix used to form adjectives in Arabic grammar, or the adjective resulting from this formation

**c ...

'' (Arabic descriptive suffix) "al-Safati" (of Safed), indicating the presence of a Jewish community living alongside Muslims in Safed in the 11th century.Barbé 2016, p. 63. According to the Muslim historian Ibn Shaddad (d. 1285), at the beginning of the 12th century, a "flourishing village" beneath a tower called Burj Yatim had existed at the site of Safed on the eve of the Crusaders' capture of the area in 1101–1102 and that "nothing" about the village was mentioned in "the early Islamic history books".Ellenblum 2007, p. 179, note 15. Although Ibn Shaddad mistakenly attributes the tower's construction to the Knights Templar, the modern historian Ronnie Ellenblum

Ronnie Ellenblum (born June 21, 1952, Haifa, Israel; died January 7, 2021, Jerusalem, Israel) was an Israeli professor at the department of geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humaniti ...

asserts that the tower was likely built during the early Muslim period (mid-7th–11th centuries).

First Crusader period

The Frankish chroniclerWilliam of Tyre

William of Tyre ( la, Willelmus Tyrensis; 113029 September 1186) was a medieval prelate and chronicler. As archbishop of Tyre, he is sometimes known as William II to distinguish him from his predecessor, William I, the Englishman, a former ...

noted the presence of a ''burgus

A ''burgus'' (Latin, plural ''burgi '') or ''turris'' ("tower") is a small, tower-like fort of the Late Antiquity, which was sometimes protected by an outwork and surrounding ditches. Darvill defines it as "a small fortified position or w ...

'' (tower) in Safed, which he called "Castrum Saphet" or "Sephet", in 1157.Ellenblum 2007, p. 179, note 16. Safed was the seat of a '' castellany'' (area governed by a castle) by at least 1165, when its ''castellan'' (appointed castle governor) was Fulk, constable of Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

. The castle of Safed was purchased from Fulk by King Amalric of Jerusalem

Amalric or Amaury I ( la, Amalricus; french: Amaury; 113611 July 1174) was King of Jerusalem from 1163, and Count of Jaffa and Ascalon before his accession. He was the second son of Melisende and Fulk of Jerusalem, and succeeded his older brot ...

in 1168. He subsequently reinforced the castle and transferred it to the Templars in the same year. Theoderich the Monk, describing his visit to the area in 1172, noted that the expanded fortification of the castle of Safed was meant to check the raids of the Turks (the Turkic Zengid dynasty

The Zengid dynasty was a Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia on behalf of the Seljuk Empire and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripol ...

ruled the area east of the Kingdom). Testifying to the considerable expansion of the castle, the chronicler Jacques de Vitry (d. 1240) wrote that it was practically built anew. The remains of Fulk's castle can now be found under the citadel excavations, on a hill above the old city.Howard M. Sacha''Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered,''

Random House, 2013 p. 190. In the estimation of modern historian Havré Barbé, the ''castellany'' of Safed comprised approximately . According to Barbé, its western boundary straddled the domains of Acre, including the fief of St. George de la Beyne, which included

Sajur

Sajur (; ) is a Druze citizens of Israel, Druze town (local council (Israel), local council) in the Galilee region of northern Israel, with an area of 3,000 dunams (3 km²). It achieved recognition as an independent local council in 1992. In ...

and Beit Jann

Beit Jann ( ar, بيت جن; he, בֵּיתּ גַ'ן) is a Druze village on Mount Meron in northern Israel. At 940 meters above sea level, Beit Jann is one of the highest inhabited locations in the country. In it had a population of .

Etymol ...

, and the fief of Geoffrey le Tor, which included Akbara and Hurfeish, and in the southwest ran north of Maghar and Sallama

Sallama ( ar, سلامة; he, סלאמה) is a Bedouin village in northern Israel. Located in the Galilee near the Tzalmon Stream, it falls under the jurisdiction of Misgav Regional Council. In its population was . The village was recognized by ...

. Its northern boundary was marked by the Nahal Dishon (Wadi al-Hindaj) stream, its southern boundary was likely formed near Wadi al-Amud, separating it from the fief of Tiberias, while its eastern limits were the marshes of the Hula Valley

The Hula Valley ( he, עמק החולה, translit. ''Emek Ha-Ḥula''; also transliterated as Huleh Valley, ar, سهل الحولة) is an agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water, which used to be Lake Hula, prior to ...

and upper Jordan Valley

The Jordan Valley ( ar, غور الأردن, ''Ghor al-Urdun''; he, עֵמֶק הַיַרְדֵּן, ''Emek HaYarden'') forms part of the larger Jordan Rift Valley. Unlike most other river valleys, the term "Jordan Valley" often applies just to ...

. There were several Jewish communities in the ''castellany'' of Safed, as testified in the accounts of Jewish pilgrims and chroniclers between 1120 and 1293. Benjamin of Tudela, who visited the town in 1170, does not record any Jews living in Safed proper.

Ayyubid interregnum

Safed was captured by theAyyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

led by Sultan Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

in 1188 after a month-long siege, following the Battle of Hattin in 1187.Sharon 2007, p152

/ref> Saladin ultimately allowed its residents to relocate to Tyre. He granted Safed and Tiberias as an ''

iqta

An iqta ( ar, اقطاع, iqṭāʿ) and occasionally iqtaʿa ( ar, اقطاعة) was an Islamic practice of tax farming that became common in Muslim Asia during the Buyid dynasty. Iqta has been defined in Nizam-al-Mulk's Siyasatnama. Administrat ...

'' (akin to a fief) to Sa'd al-Din Mas'ud ibn Mubarak (d. 1211), the son of his niece, after which it was bequeathed to Sa'd al-Din's son Ahmad.Drory 2004, p. 164. Samuel ben Samson Samuel ben Samson (also Samuel ben Shimshon) was a rabbi who lived in France and made a pilgrimage to Israel in 1210, visiting a number of villages and cities there, including Jerusalem. Amongst his companions were Jonathan ben David ha-Cohen

Rabbi ...

, who visited the town in 1210, mentions the existence of a Jewish community of at least fifty there. He also noted that two Muslims guarded and maintained the cave tomb of a rabbi, Hanina ben Horqano, in Safed. The ''iqta'' of Safed was taken from the family of Sa'd al-Din by the Ayyubid emir of Damascus, al-Mu'azzam Isa, in 1217.Luz 2014, p. 34. Two years later, during the Crusader siege of Damietta, al-Mu'azzam Isa had the Safed castle demolished to prevent its capture and reuse by potential future Crusaders.

Second Crusader period

As an outcome of the treaty negotiations between the Crusader leaderTheobald I of Navarre

Theobald I (french: Thibaut, es, Teobaldo; 30 May 1201 – 8 July 1253), also called the Troubadour and the Posthumous, was Count of Champagne (as Theobald IV) from birth and King of Navarre from 1234. He initiated the Barons' Crusade, was famou ...

and the Ayyubid emir of Damascus, al-Salih Isma'il, in 1240 Safed once again passed to Crusader control. Afterward, the Templars were tasked with rebuilding the town's fortress, with efforts spearheaded by Benoît d'Alignan, Bishop of Marseille. The rebuilding is recorded in a short treatise, ''De constructione castri Saphet

''De constructione castri Saphet'' ("On the Construction of the Castle of Ṣafad") is a short anonymous Latin account of the re-building of the fortress of Ṣafad by the Knights Templar between 1241 and 1244. There is no other account of its k ...

'', from the early 1260s. The reconstruction was completed at the considerable expense of 40,000 bezant

In the Middle Ages, the term bezant (Old French ''besant'', from Latin ''bizantius aureus'') was used in Western Europe to describe several gold coins of the east, all derived ultimately from the Roman ''solidus''. The word itself comes from th ...

s in 1243.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 757. The new fortress was larger than the original, with a capacity for 2,200 soldiers in time of war, and with a resident force of 1,700 in peacetime. The garrison's goods and services were provided by the town or large village growing rapidly beneath the fortress, which, according to Benoit's account, contained a market, "numerous inhabitants" and was protected by the fortress. The settlement also benefited from trade with travelers on the route between Acre and the Jordan Valley, which passed through Safed.

Mamluk period

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the Mamluks in 1250 and the Mamluk sultan Baybars entered Syria with his army in 1261. Thereafter, he led a series of campaigns over several years against Crusader strongholds across the Syrian coastal mountains. Safed, with its position overlooking the Jordan River and allowing the Crusaders early warnings of Muslim troop movements in the area, had been a consistent aggravation for the Muslim regional powers. After a six-week siege,Luz 2014, p. 35. Baybars captured Safed in July 1266, after which he had nearly the entire garrison killed.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 758. The siege occurred during a Mamluk military campaign to subdue Crusader strongholds in Palestine and followed a failed attempt to capture the Crusaders' coastal stronghold of Acre. Unlike the Crusader fortresses along the coastline, which were demolished upon their capture by the Mamluks, Baybars spared the fortress of Safed.Drory 2004, p. 165. He likely preserved it because of the strategic value stemming from its location on a high mountain and its isolation from other Crusader fortresses. Moreover, Baybars determined that in the event of a renewed Crusader invasion of the coastal region, a strongly fortified Safed could serve as an ideal headquarters to confront the Crusader threat. In 1268, he had the fortress repaired, expanded and strengthened. He commissioned numerous building works in the town of Safed, including caravanserais, markets and baths, and converted the town's church into a mosque.Drory 2004, p. 166. The mosque, called Jami al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), was completed in 1275. By the end of Baybars's reign, Safed had developed into a prosperous town and fortress.

Baybars assigned fifty-four

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the Mamluks in 1250 and the Mamluk sultan Baybars entered Syria with his army in 1261. Thereafter, he led a series of campaigns over several years against Crusader strongholds across the Syrian coastal mountains. Safed, with its position overlooking the Jordan River and allowing the Crusaders early warnings of Muslim troop movements in the area, had been a consistent aggravation for the Muslim regional powers. After a six-week siege,Luz 2014, p. 35. Baybars captured Safed in July 1266, after which he had nearly the entire garrison killed.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 758. The siege occurred during a Mamluk military campaign to subdue Crusader strongholds in Palestine and followed a failed attempt to capture the Crusaders' coastal stronghold of Acre. Unlike the Crusader fortresses along the coastline, which were demolished upon their capture by the Mamluks, Baybars spared the fortress of Safed.Drory 2004, p. 165. He likely preserved it because of the strategic value stemming from its location on a high mountain and its isolation from other Crusader fortresses. Moreover, Baybars determined that in the event of a renewed Crusader invasion of the coastal region, a strongly fortified Safed could serve as an ideal headquarters to confront the Crusader threat. In 1268, he had the fortress repaired, expanded and strengthened. He commissioned numerous building works in the town of Safed, including caravanserais, markets and baths, and converted the town's church into a mosque.Drory 2004, p. 166. The mosque, called Jami al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), was completed in 1275. By the end of Baybars's reign, Safed had developed into a prosperous town and fortress.

Baybars assigned fifty-four mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s, at the head of whom was Emir Ala al-Din Kandaghani, to oversee the management of Safed and its dependencies.Barbé 2016, pp. 71–72. From the time of its capture, the city was made the administrative center of Mamlakat Safad,Sharon, 1997, pxii

/ref> one of seven ''mamlakas'' (provinces), whose governors were typically appointed from

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

, which made up Mamluk Syria. Initially, its jurisdiction corresponded roughly with the Crusader ''castellany''. After the fall of the Montfort Castle

Montfort ( he, מבצר מונפור, Mivtzar Monfor; ar, قلعة القرين, ''Qal'at al-Qurain'' or ''Qal'at al-Qarn'' - "Castle of the Little Horn" or "Castle of the Horn") is a ruined Crusader castle in the Upper Galilee region in north ...

to the Mamluks in 1271, the castle and its dependency, the Shaghur district, were incorporated into Mamlakat Safad. The territorial jurisdiction of the ''mamlaka'' eventually spanned the entire Galilee and the lands further south down to Jenin.

The geographer

The geographer al-Dimashqi The Arabic '' nisbah'' (attributive title) Al-Dimashqi ( ar, الدمشقي) denotes an origin from Damascus, Syria.

Al-Dimashqi may refer to:

* Al-Dimashqi (geographer): a medieval Arab geographer.

* Abu al-Fadl Ja'far ibn 'Ali al-Dimashqi: 12th- ...

, who died in Safed in 1327, wrote around 1300 that Baybars built a "round tower and called it Kullah ..." after leveling the old fortress. The tower was built in three stories, and provided with provisions, halls, and magazines. Under the structure, a cistern collected enough rainwater to regularly supply the garrison. The governor of Safed, Emir Baktamur al-Jukandar (the Polomaster; ), built a mosque later called after him in the northeastern section of the city. The geographer Abu'l Fida

Ismāʿīl b. ʿAlī b. Maḥmūd b. Muḥammad b. ʿUmar b. Shāhanshāh b. Ayyūb b. Shādī b. Marwān ( ar, إسماعيل بن علي بن محمود بن محمد بن عمر بن شاهنشاه بن أيوب بن شادي بن مروان ...

(1273–1331), the ruler of Hama, described Safed as follows:afedwas a town of medium size. It has a very strongly built castle, which dominates the Lake of Tabariyyah ea of Galilee There are underground watercourses, which bring drinking-water up to the castle-gate...Its suburbs cover three hills... Since the place was conquered by Al Malik Adh Dhahir aybarsfrom the Franks rusaders it has been made the central station for the troops who guard all the coast-towns of that district."The native ''

qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

'' (Islamic head judge) of Safed, Shams al-Din al-Uthmani, composed a text about Safed called ''Ta'rikh Safad'' (the History of Safed) during the rule of its governor Emir Alamdar (). The extant parts of the work consisted of ten folios largely devoted to Safed's distinguishing qualities, its dependent villages, agriculture, trade and geography, with no information about its history. His account reveals the city's dominant features were its citadel, the Red Mosque and its towering position over the surrounding landscape. He noted Safed lacked "regular urban planning", ''madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , pl. , ) is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary instruction or higher learning. The word is variously transliterated '' ...

s'' (schools of Islamic law), ''ribat

A ribāṭ ( ar, رِبَـاط; hospice, hostel, base or retreat) is an Arabic term for a small fortification built along a frontier during the first years of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb to house military volunteers, called ''murabitun'' ...

s'' (hostels for military volunteers) and defensive walls, and that its houses were clustered in disarray and its streets were not distinguishable from its squares. He attributed the city's shortcomings to the dearth of generous patrons.Luz 2014, p. 180. A device for transporting buckets of water called the ''satura'' existed in the city mainly to supply the soldiers of the citadel; surplus water was distributed to the city's residents. Al-Uthmani praised the natural beauty of Safed, its therapeutic air, and noted that its residents took strolls in the surrounding gorges and ravines.

The Black Death brought about a decline in the population in Safed from 1348 onward. There is little available information about the city and its dependencies during the last century of Mamluk rule (), though travelers' accounts describe a general decline precipitated by famine, plagues, natural disasters and political instability.

Ottoman era

Sixteenth-century prosperity

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the Battle of Marj Dabiq

The Battle of Marj Dābiq ( ar, مرج دابق, meaning "the meadow of Dābiq"; tr, Mercidabık Muharebesi), a decisive military engagement in Middle Eastern history, was fought on 24 August 1516, near the town of Dabiq, 44 km north of ...

in northern Syria in 1516.Rhode 1979, p. 18. Safed's inhabitants sent the keys of the town citadel to Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

after he captured Damascus.Layish 1987, p. 67. No fighting was recorded around Safed, which was bypassed by Selim's army on the way to Mamluk Egypt. The sultan had placed the district of Safed under the jurisdiction of the Mamluk governor of Damascus, Janbirdi al-Ghazali

Janbirdi al-Ghazali ( ar, جان بردي الغزالي; ''Jān-Birdi al-Ghazāli''; died 1521) was the first governor of Damascus Province under the Ottoman Empire from February 1519 until his death in February 1521.

Career Viceroy of Hama and ...

, who defected to the Ottomans. Rumors in 1517 that Selim was slain by the Mamluks precipitated a revolt against the newly-appointed Ottoman governor by the townspeople of Safed, which resulted in wide-scale killings, many of which targeted the city's Jews, who were viewed as sympathizers of the Ottomans. Safed became the capital of the Safed Sanjak

Safed Sanjak ( ar, سنجق صفد; tr, Safed Sancağı) was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Damascus Eyalet ( Ottoman province of Damascus) in 1517–1660, after which it became part of the Sidon Eyalet (Ottoman province of Sidon). The sanjak was ce ...

, roughly corresponding with Mamlakat Safad but excluding most of the Jezreel Valley and the area of Atlit

Atlit ( he, עַתְלִית, ar, عتليت) is a coastal town located south of Haifa, Israel. The community is in the Hof HaCarmel Regional Council in the Haifa District of Israel.

Off the coast of Atlit is a submerged Neolithic village. At ...

, part of the larger province of Damascus Eyalet

ota, ایالت شام

, conventional_long_name = Damascus Eyalet

, common_name = Damascus Eyalet

, subdivision = Eyalet

, nation = the Ottoman Empire

, year_start = 1516

, year_end ...

.Abbasi 2003, p. 50.

In 1525/26, the population of Safed consisted of 633 Muslim families, 40 Muslim bachelors, 26 Muslim religious persons, nine Muslim disabled, 232 Jewish families, and 60 military families. In 1549, under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

, a wall was constructed and troops were garrisoned to protect the city.Abraham David, 2010pp. 95–96

/ref> In 1553/54, the population consisted of 1,121 Muslim households, 222 Muslim bachelors, 54 Muslim religious leaders, 716 Jewish households, 56 Jewish bachelors, and 9 disabled persons. At least in the 16th century, Safed was the only ''kasaba'' (city) in the sanjak and in 1555 was divided into nineteen ''mahallas'' (quarters), seven Muslim and twelve Jewish.Rhode 1979, p. 34. The total population of Safed rose from 926 households in 1525–26 to 1,931 households in 1567–1568. Among these, the Jewish population rose from a mere 233 households in 1525 to 945 households in 1567–1568.Petersen (2001), Gazetteer 6, s,v

Ṣafad

/ref> The Muslim quarters were Sawawin, located west of the fortress; Khandaq (the moat); Ghazzawiyah, which had likely been settled by Gazans; Jami' al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), located south of the fortress and named for the local mosque; al-Akrad, which dated to the Middle Ages and continued to exist through the 19th century,Ebied and Young 1976, p. 7. and whose inhabitants were mostly

Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ira ...

; al-Wata (the lower), the southernmost quarter of Safed and situated below the city; and al-Suq, named after the market or mosque located within the quarter.Rhode 1979, pp. 34–35. The Jewish quarters were all situated west of the fortress. Each quarter was named for the place of origin of its inhabitants: Purtuqal (Portugal), Qurtubah ( Cordoba), Qastiliyah ( Castille), Musta'rib (Jews of local, Arabic-speaking origin), Magharibah (northwestern Africa), Araghun ma' Qatalan ( Aragon and Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

), Majar (Hungary), Puliah ( Apulia), Qalabriyah ( Calabria), Sibiliyah (Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

), Taliyan (Italian) and Alaman (German).

In the 15th and 16th centuries there were a number of well-known Sufi (Muslim mysticism) followers of

In the 15th and 16th centuries there were a number of well-known Sufi (Muslim mysticism) followers of Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

living in Safed. The Sufi sage Ahmad al-Asadi (1537–1601) established a '' zawiya'' (Sufi lodge) called Sadr Mosque in the city. Safed became a center of Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "receiver"). The defin ...

(Jewish mysticism) during the 16th century.

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, many prominent rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s found their way to Safed, among them the Kabbalists Isaac Luria

Isaac ben Solomon Luria Ashkenazi (1534 Fine 2003, p24/ref> – July 25, 1572) ( he, יִצְחָק בן שלמה לוּרְיָא אשכנזי ''Yitzhak Ben Sh'lomo Lurya Ashkenazi''), commonly known in Jewish religious circles as "Ha'ARI" (mea ...

and Moshe Kordovero; Joseph Caro

Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, also spelled Yosef Caro, or Qaro ( he, יוסף קארו; 1488 – March 24, 1575, 13 Nisan 5335 A.M.), was the author of the last great codification of Jewish law, the '' Beit Yosef'', and its popular analogue, the ''Shu ...

, the author of the Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulchan Aruch'' ( he, שֻׁלְחָן עָרוּך , literally: "Set Table"), sometimes dubbed in English as the Code of Jewish Law, is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Judaism. It was authored in Safed (today in I ...

and Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, composer of the Sabbath hymn "Lecha Dodi

Lekha Dodi ( he, לכה דודי) is a Hebrew-language Jewish liturgical song recited Friday at dusk, usually at sundown, in synagogue to welcome the Sabbath prior to the evening services. It is part of Kabbalat Shabbat.

The refrain of ''Lek ...

". The influx of Sephardi Jews

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

—reaching its peak under the rule of Sultans Suleiman the Magnificent and Selim II—made Safed a global center for Jewish learning and a regional center for trade throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. Sephardi Jews and other Jewish immigrants by then outnumbered the indigenous (Musta'rib) Jews in the city. During this period, the Jews developed the textile industry in Safed, transforming the town into an important and lucrative centre for wool production and textile manufacturing. There were more than 7,000 Jews in Safed in 1576 when Murad III issued an edict for the forced deportation of 1,000 wealthy Jewish families to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

to boost the island's economy. There is no evidence that the edict, or a second one issued the following year for the removal of 500 families, was enforced. A Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

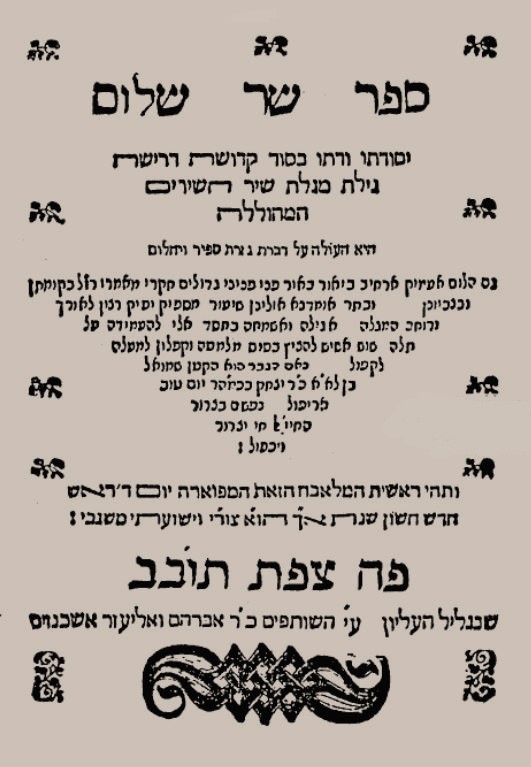

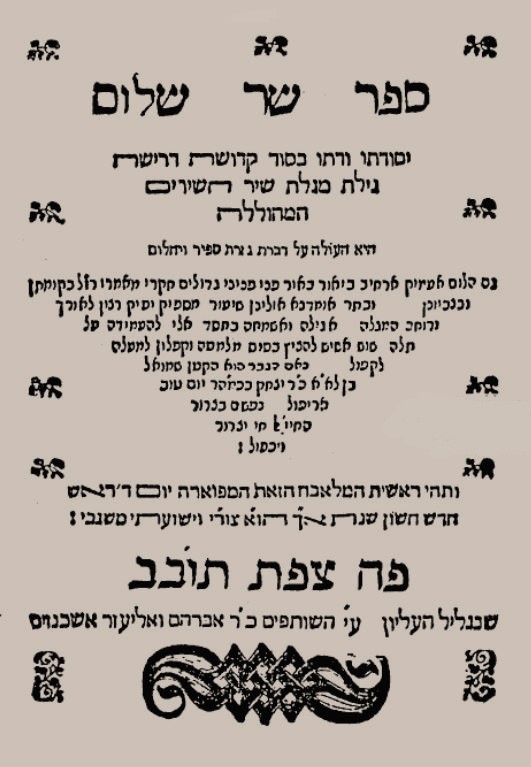

printing press, the first in Western Asia, was established in Safed in 1577 by Eliezer Ashkenazi and his son, Isaac of Prague. In 1584, there were 32 synagogues registered in the town.

Political decline, attacks and natural disasters

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602 the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon,

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602 the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon, Fakhr al-Din Fakhr al-Din ( ar, فخر الدين ) is an Arabic male given name and (in modern usage) a surname, meaning ''pride of the religion''. Alternative transliterations include Fakhruddin , Fakhreddin, Fakhreddine, Fakhraddin, Fakhruddin, Fachreddin, ...

of the Ma'n dynasty

The Ma'n dynasty ( ar, ٱلْأُسْرَةُ ٱلْمَعْنِيَّةُ, Banū Maʿn, alternatively spelled ''Ma'an''), also known as the Ma'nids; ( ar, ٱلْمَعْنِيُّونَ), were a family of Druze chiefs of Arab stock based in the ...

, was appointed the sanjak-bey

''Sanjak-bey'', ''sanjaq-bey'' or ''-beg'' ( ota, سنجاق بك) () was the title given in the Ottoman Empire to a bey (a high-ranking officer, but usually not a pasha) appointed to the military and administrative command of a district (''sanjak ...

(district governor) of Safed, in addition to his governorship of neighboring Sidon-Beirut Sanjak

Sidon-Beirut Sanjak was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Sidon Eyalet (Province of Sidon) of the Ottoman Empire. Prior to 1660, the Sidon-Beirut Sanjak had been part of Damascus Eyalet, and for brief periods in the 1590s, Tripoli Eyalet.

Territory and ...

to the north. In the preceding years, the Safed Sanjak had entered a state of ruin and desolation, and was often the scene of conflict between the local Druze and Shia Muslim peasants and the Ottoman authorities. By 1605 Fakhr al-Din had established peace and security in the sanjak, with highway brigandage and Bedouin raids having ceased under his watch. Trade and agriculture consequently thrived and the population prospered. He formed close relations with the city's Sunni Muslim ''ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' (religious scholars), particularly the mufti

A Mufti (; ar, مفتي) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion (''fatwa'') on a point of Islamic law (''sharia''). The act of issuing fatwas is called ''iftāʾ''. Muftis and their ''fatwas'' played an important role ...

Ahmad al-Khalidi of the Hanafi

The Hanafi school ( ar, حَنَفِية, translit=Ḥanafiyah; also called Hanafite in English), Hanafism, or the Hanafi fiqh, is the oldest and one of the four traditional major Sunni schools ( maddhab) of Islamic Law (Fiqh). It is named a ...

''fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

'' (school of jurisprudence), who became his practical court historian. Fakhr al-Din was driven into European exile by the Ottomans in 1613, but his son Ali became governor in 1615. Fakhr al-Din returned to his domains in 1618 and five years later regained the governorship of Safed, which the Ma'ns had lost, after his victory against the governor of Damascus at the Battle of Anjar

The Battle of Anjar was fought on 1 November 1623 between the army of Fakhr al-Din II and an coalition army led by the governor of Damascus Mustafa Pasha.

Background

In 1623, Yunus al-Harfush prohibited the Druze of the Chouf from cultivatin ...

. In , the orientalist Quaresmius spoke of Safed being inhabited "chiefly by Hebrews, who had their synagogues and schools, and for whose sustenance contributions were made by the Jews in other parts of the world." According to the historian Louis Finkelstein, the Jewish community of Safed was plundered by the Druze under Mulhim ibn Yunus, nephew of Fakhr al-Din.Finkelstein 1960, p. 63. Five years later, Fakhr al-Din was routed by the Ottoman governor of Damascus, Mulhim abandoned Safed, and its Jewish residents returned.

The Druze again attacked the Jews of Safed in 1656. During the power struggle between Fakhr al-Din's heirs (1658–1667), each faction attacked Safed. In 1660, in the turmoil following the death of Mulhim, the Druze destroyed Safed with only a few of the former Jewish residents returning to the city by 1662.Joel Rappel. ''History of Eretz Israel from Prehistory up to 1882'' (1980), Vol.2, p.531. "In 1662 Sabbathai Sevi arrived to Jerusalem. It was the time when the Jewish settlements of Galilee were destroyed by the Druze: Tiberias was completely desolate and only a few of former Safed residents had returned..."Barnai, Jacob. ''The Jews in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: under the patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine'' (University of Alabama Press 1992) ; p. 14 Safed Sanjak and the neighboring Sidon-Beirut Sanjak

Sidon-Beirut Sanjak was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Sidon Eyalet (Province of Sidon) of the Ottoman Empire. Prior to 1660, the Sidon-Beirut Sanjak had been part of Damascus Eyalet, and for brief periods in the 1590s, Tripoli Eyalet.

Territory and ...

to the north were administratively separated from Damascus in 1660 to form the Sidon Eyalet

ota, ایالت صیدا

, common_name = Eyalet of Sidon

, subdivision = Eyalet

, nation = the Ottoman Empire

, year_start = 1660

, year_end = 1864

, date_start =

, date_end =

, ev ...

, of which Safed was briefly the capital.Salibi 1988, p. 66. The province was created by the imperial government to check the power of the Druze of Mount Lebanon, as well as the Shia of Jabal Amil

Jabal Amil ( ar, جبل عامل, Jabal ʿĀmil), also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila, is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Musl ...

.

As nearby Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

remained desolate for several decades, Safed gained the key position among Galilean Jewish communities. In 1665, the Sabbatai Sevi

Sabbatai Zevi (; August 1, 1626 – c. September 17, 1676), also spelled Shabbetai Ẓevi, Shabbeṯāy Ṣeḇī, Shabsai Tzvi, Sabbatai Zvi, and ''Sabetay Sevi'' in Turkish, was a Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turk ...

movement is said to have arrived in the town. In the 1670s, the account of the Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

recorded that Safed contained three caravanserais, several mosques, seven Sufi lodges and six public bathhouses. The Red Mosque was restored by Safed's governor Salih Bey in 1671/72, at which point it measured about , had all masonry interior, a cistern to collect rain water in the winter for drinking and a tall minaret over its southern entrance; the minaret had been destroyed before the end of the 17th century.

The Tiberias-based sheikh Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Pale ...

of the local Arab Zaydan clan, whose father Umar al-Zaydani

Umar al-Zaydani (died 1706) was the '' multazem'' (tax farmer) of Safad and Tiberias, and surrounding villages, between 1697 and 1706 and the '' sanjak-bey'' (district governor) of Safad between 1701 and 1706.Joudah 1987, pp. 20-21. He was appointe ...

had been the governor and tax farmer of Safed in 1702–1706, wrested control of Safed and its tax farm

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or n ...

from its native strongman, Muhammad Naf'i, through military pressure and diplomacy by 1740. The Naf'i, Shahin, and Murad families continued to farm the taxes of Safed and its countryside into the 1760s as Zahir's subordinates. By the 1760s, Zahir entrusted Safed to his son Ali, who made the town his headquarters. After Zahir was killed by Ottoman imperial forces, the governor of Sidon, Jazzar Pasha

Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar ( ar, أحمد باشا الجزّار; ota, جزّار أحمد پاشا; ca. 1720–30s7 May 1804) was the Acre-based Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet from 1776 until his death in 1804 and the simultaneous governor of D ...

, moved to oust Zahir's sons from their Galilee strongholds. Ali made a final, unsuccessful stand against Jazzar Pasha from Safed, which was afterward captured and garrisoned by the governor. The concomitant rise of Acre, established by Zahir as his capital in 1750 and which served as the capital of the Sidon Eyalet under Jazzar Pasha (1775–1804) and his successors, Sulayman Pasha al-Adil (1805–1819) and Abdullah Pasha (1820–1831), contributed to the political decline of Safed. It became a subdistrict center with limited local influence, belonging to the Acre Sanjak .

Underdevelopment and a series of natural disasters further contributed to Safed's decline during the 17th–mid-19th centuries. An outbreak of plague decimated the population in 1742 and the Near East earthquakes of 1759 left the city in ruins, killing 200 residents. An influx of Russian Jews in 1776 and 1781, and of Lithuanian Jew

Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks () are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern Suwałki and Białystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent areas o ...

s of the Perushim

The ''perushim'' ( he, פרושים) were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria under Otto ...

movement in 1809 and 1810, reinvigorated the Jewish community. In 1812, another plague killed 80% of the Jewish population.Franco 1916, p. 633. Following Abdullah Pasha of Acre's ordered killing of his Jewish vizier Haim Farhi

Haim Farhi ( he, חיים פרחי}, ; ar, حيم فارحي, also known as Haim "El Mu'allim" ar, المعلم lit. "The Teacher"), (1760 – August 21, 1820) was an adviser to the governors of the Galilee in the days of the Ottoman Empire. A ...

, who served the same post under Jazzar and Sulayman, the governor imprisoned the Jewish residents of Safed on 12 August 1820, accusing them of tax evasion under the concealment of Farhi; they were released upon paying a ransom. The war between Abdullah Pasha and the influential Farhi brothers in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

and Damascus in 1822–1823 prompted Jewish flight from the Galilee in general, though by 1824 Jewish immigrants were steadily moving to the city.

The Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

forces of Muhammad Ali wrested control of the Levant from the Ottomans in 1831 and in the same year many Jews who had fled the Galilee, including Safed, under Abdullah Pasha returned as a result of Muhammad Ali's liberal policies toward Jews. Safed was raided by Druze in 1833 at the approach of Ibrahim Pasha, the Egyptian governor of the Levant. In the following year, the Muslim notables of the city, led by Salih al-Tarshihi, opposed to the Egyptian policy of conscription, joined the peasants' revolt in Palestine

The Peasants' Revolt was a rebellion against Egyptian conscription and taxation policies in Palestine. While rebel ranks consisted mostly of the local peasantry, urban notables and Bedouin tribes also formed an integral part of the revolt, wh ...

. During the revolt, rebels plundered the city for over thirty days. Emir Bashir Shihab II

Emir Bashir Shihab II () (also spelled "Bachir Chehab II"; 2 January 1767–1850) was a Lebanese emir who ruled Ottoman Lebanon in the first half of the 19th century. Born to a branch of the Shihab family which had converted from Sunni Islam, th ...

of Mount Lebanon and his Druze fighters entered its environs in support of the Egyptians and compelled Safed's leaders to surrender. The Galilee earthquake of 1837

The Galilee earthquake of 1837, often called the Safed earthquake, shook the Galilee on January 1 and is one of a number of moderate to large events that have occurred along the Dead Sea Transform (DST) fault system that marks the boundary of t ...

killed about half of Safed's 4,000-strong Jewish community,Lieber 1992, p256

destroyed all fourteen of its synagogues and prompted the flight of 600

Perushim

The ''perushim'' ( he, פרושים) were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria under Otto ...

for Jerusalem; the surviving Sephardic and Hasidic Jews mostly remained. Among the 2,158 residents of Safed who had died, 1,507 were Ottoman subjects, the rest foreign citizens. The Jewish community, whose quarter was situated on the hillside, had been particularly hard hit, the southern, Muslim section of the town experiencing considerably less damage. The following year, in 1838, Druze rebels and local Muslims raided Safed for three days.

Tanzimat reforms and revival

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide Tanzimat reforms, which were first adopted in the 1840s, brought about a steady rise in Safed's population and economy. In 1849 Safed had a total estimated population of 5,000, of whom 2,940-3,440 were Muslims, 1,500-2,000 were Jews and 60 were Christians.Abbasi 2003, p. 52. The population was estimated at 7,000 in 1850–1855, of whom 2,500-3,000 were Jews. The Jewish population increased in the last half of the 19th century by immigration from

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide Tanzimat reforms, which were first adopted in the 1840s, brought about a steady rise in Safed's population and economy. In 1849 Safed had a total estimated population of 5,000, of whom 2,940-3,440 were Muslims, 1,500-2,000 were Jews and 60 were Christians.Abbasi 2003, p. 52. The population was estimated at 7,000 in 1850–1855, of whom 2,500-3,000 were Jews. The Jewish population increased in the last half of the 19th century by immigration from Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

, and Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, aft ...

(d. 1885) visited Safed seven times and financed much of the rebuilding of Safed's synagogues and Jewish houses.

In 1864 the Sidon Eyalet was absorbed into the new province of Syria Vilayet. In the new province, Safed remained part of the Acre Sanjak and served as the center of a kaza

A kaza (, , , plural: , , ; ota, قضا, script=Arab, (; meaning 'borough')

* bg, околия (; meaning 'district'); also Кааза

* el, υποδιοίκησις () or (, which means 'borough' or 'municipality'); also ()

* lad, kaza

, ...

(third-level subdivision), whose jurisdiction covered the villages around the city and the subdistrict of Mount Meron

Mount Meron ( he, הַר מֵירוֹן, ''Har Meron''; ar, جبل الجرمق, ''Jabal al-Jarmaq'') is a mountain in the Upper Galilee region of Israel. It has special significance in Jewish religious tradition and parts of it have been decla ...

(Jabal Jarmaq). In the Ottoman survey of Syria in 1871, Safed had 1,395 Muslim households, 1,197 Jewish households and three Christian households. The survey recorded a relatively high number of businesses in the city, namely 227 shops, fifteen mills, fourteen bakeries and four olive oil factories, an indicator of Safed's long-established role as an economic hub for the people of the Upper Galilee, the Hula Valley

The Hula Valley ( he, עמק החולה, translit. ''Emek Ha-Ḥula''; also transliterated as Huleh Valley, ar, سهل الحولة) is an agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water, which used to be Lake Hula, prior to ...

, the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between di ...

and parts of modern-day South Lebanon

Southern Lebanon () is the area of Lebanon comprising the South Governorate and the Nabatiye Governorate. The two entities were divided from the same province in the early 1990s. The Rashaya and Western Beqaa Districts, the southernmost distric ...

.Abbasi 2003, p. 54. Through the late 19th century, Safed's merchants served as middlemen in the Galilee grain trade, selling the wheat, pulses and fruit grown by the peasants of the Galilee to the traders of Acre, who in turn exported at least part of the merchandise to Europe. Safed also maintained extensive trade with the port of Tyre. The bulk of trade in Safed, which was traditionally dominated by the city's Jews, largely passed to its Muslim merchants during the late 19th century, particularly trade with the local villagers; Muslim traders offered higher credit to the peasants and were able to obtain government assistance for debt repayments. The wealth of Safed's Muslims increased and a number of the city's leading Muslim families made an opportunity from the Ottoman Land Code of 1858 to purchase extensive tracts around Safed.Abbasi 2003, p. 56. The major Muslim landowning clans were the Soubeh, Murad and Qaddura. The latter owned about 50,000 dunams toward the end of the century, including eight villages around Safed.

In 1878 the municipal council of Safed was established. In 1888 the Acre Sanjak, including the Safed Kaza, became part of the new province of Beirut Vilayet, an administrative state of affairs which persisted until the Empire's fall in 1918. The centralization and stability brought by the imperial reforms solidified the political status and practical influence of Safed in the Upper Galilee.Abbasi 2003, p. 51. The Ottomans developed Safed into a center for Sunni Islam to counterbalance the influence of non-Muslim communities in its environs and the Shia Muslims of Jabal Amil.Abbasi 2003, p. 53. Along with the three major landowning families, the Muslim ''ulema'' (religious scholarly) families of Nahawi, Qadi, Mufti and Naqib comprised the urban elite (''a'yan'') of the city. The Sunni courts of Safed arbitrated over cases in Akbara, Ein al-Zeitun and as far away as Mejdel Islim. The government settled Algerian and Circassian exiles in the countryside of Safed in the 1860s and 1878, respectively, possibly in an effort to strengthen the Muslim character of the area. At least two Muslim families in the city itself, Arabi and Delasi, were of Algerian origin, though they accounted for a small proportion of the city's overall Muslim population. According to the late 19th-century account of British missionary E. W. G. Masterman, the Muslim families of Safed originated from Damascus, Transjordan and the villages around Safed. When Baybars conquered Safed in 1266 he settled many Damascenes in the city. Until the late 19th century the Muslims of Safed maintained strong social and cultural connections with Damascus. Masterman noted that the Muslims of Safed were conservative, "active and hardy", who "dress dwell and move about more than the people from the region of southern Palestine". They lived mainly in three quarters of the city: al-Akrad, whose residents were mostly laborers, Sawawin, home to the Muslim ''a'yan'' households and the city's Catholic community, and al-Wata, whose inhabitants were largely shopkeepers and minor traders.Schumacher, 1888, p