Tyrannosaurus muscle mass.png on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosaurus'' lived throughout what is now western North America, on what was then an island continent known as Laramidia. ''Tyrannosaurus'' had a much wider range than other Tyrannosauridae, tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of geologic formation, rock formations dating to the Maastrichtian Age (geology), age of the Upper Cretaceous Period (geology), period, 68 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago. It was the last known member of the tyrannosaurids and among the last non-aves, avian dinosaurs to exist before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

Like other tyrannosaurids, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was a bipedal carnivore with a massive skull balanced by a long, heavy tail. Relative to its large and powerful hind limbs, the forelimbs of ''Tyrannosaurus'' were short but unusually powerful for their size, and they had two clawed digits. The most complete specimen measures up to in length; however, according to most modern estimates, ''T. rex'' could grow to lengths of over , up to tall at the hips, and in body mass. Although other theropods rivaled or exceeded ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' in dinosaur size, size, it is still among the largest known land predators and is estimated to have exerted the strongest bite force among all terrestrial animals. By far the largest carnivore in its environment, ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' was most likely an apex predator, preying upon hadrosaurs, juvenile armored herbivores like ceratopsians and ankylosaurs, and possibly sauropods. Some experts have suggested the dinosaur was primarily a scavenger. The question of whether ''Tyrannosaurus'' was an apex predator or a pure scavenger was among the longest debates in paleontology. Most paleontologists today accept that ''Tyrannosaurus'' was both an active predator and a scavenger.

Specimens of Tyrannosaurus, Specimens of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' include some that are nearly complete skeletons. Soft tissue and proteins have been reported in at least one of these specimens. The abundance of fossil material has allowed significant research into many aspects of its biology, including its life history and biomechanics. The feeding habits, physiology, and potential speed of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' are a few subjects of debate. Its Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy is also controversial, as some scientists consider ''Tarbosaurus, Tarbosaurus bataar'' from Asia to be a second ''Tyrannosaurus'' species, while others maintain ''Tarbosaurus'' is a separate genus. Several other genera of North American tyrannosaurids have also been synonym (biology), synonymized with ''Tyrannosaurus''.

As the archetypal theropod, ''Tyrannosaurus'' has been one of the best-known dinosaurs since the early 20th century and has been featured in film, advertising, postal stamps, and many other media.

Teeth from what is now documented as a ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' were found in 1874 by Arthur Lakes near Golden, Colorado. In the early 1890s, John Bell Hatcher collected postcranial elements in eastern Wyoming. The fossils were believed to be from the large species ''Ornithomimus, Ornithomimus grandis'' (now ''Deinodon'') but are now considered ''T. rex'' remains.

In 1892, Edward Drinker Cope found two vertebral fragments of a large dinosaur. Cope believed the fragments belonged to an "agathaumid" (Ceratopsidae, ceratopsid) dinosaur, and named them ''Manospondylus gigas'', meaning "giant porous vertebra", in reference to the numerous openings for blood vessels he found in the bone. The ''M. gigas'' remains were, in 1907, identified by Hatcher as those of a theropod rather than a ceratopsid.

Henry Fairfield Osborn recognized the similarity between ''Manospondylus gigas'' and ''T. rex'' as early as 1917, by which time the second vertebra had been lost. Owing to the fragmentary nature of the ''Manospondylus'' vertebrae, Osborn did not synonymize the two genera, instead considering the older genus indeterminate. In June 2000, the Black Hills Institute found around 10% of a ''Tyrannosaurus'' skeleton (Black Hills Institute, BHI 6248) at a site that might have been the original ''M. gigas'' locality.

Teeth from what is now documented as a ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' were found in 1874 by Arthur Lakes near Golden, Colorado. In the early 1890s, John Bell Hatcher collected postcranial elements in eastern Wyoming. The fossils were believed to be from the large species ''Ornithomimus, Ornithomimus grandis'' (now ''Deinodon'') but are now considered ''T. rex'' remains.

In 1892, Edward Drinker Cope found two vertebral fragments of a large dinosaur. Cope believed the fragments belonged to an "agathaumid" (Ceratopsidae, ceratopsid) dinosaur, and named them ''Manospondylus gigas'', meaning "giant porous vertebra", in reference to the numerous openings for blood vessels he found in the bone. The ''M. gigas'' remains were, in 1907, identified by Hatcher as those of a theropod rather than a ceratopsid.

Henry Fairfield Osborn recognized the similarity between ''Manospondylus gigas'' and ''T. rex'' as early as 1917, by which time the second vertebra had been lost. Owing to the fragmentary nature of the ''Manospondylus'' vertebrae, Osborn did not synonymize the two genera, instead considering the older genus indeterminate. In June 2000, the Black Hills Institute found around 10% of a ''Tyrannosaurus'' skeleton (Black Hills Institute, BHI 6248) at a site that might have been the original ''M. gigas'' locality.

Barnum Brown, assistant curator of the American Museum of Natural History, found the first partial skeleton of ''T. rex'' in eastern Wyoming in 1900. Brown found another partial skeleton in the Hell Creek Formation in Montana in 1902, comprising approximately 34 fossilized bones. Writing at the time Brown said "Quarry No. 1 contains the femur, pubes, humerus, three vertebrae and two undetermined bones of a large Carnivorous Dinosaur not described by Othniel Charles Marsh, Marsh.... I have never seen anything like it from the Cretaceous". Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, named the second skeleton ''T. rex'' in 1905. The generic name is derived from the Greek language, Greek words ''τύραννος'' (''tyrannos'', meaning "tyrant") and ''wikt:σαῦρος, σαῦρος'' (''sauros'', meaning "lizard"). Osborn used the Latin language, Latin word ''rex'', meaning "king", for the specific name. The full Binomial nomenclature, binomial therefore translates to "tyrant lizard the king" or "King Tyrant Lizard", emphasizing the animal's size and perceived dominance over other species of the time.

Barnum Brown, assistant curator of the American Museum of Natural History, found the first partial skeleton of ''T. rex'' in eastern Wyoming in 1900. Brown found another partial skeleton in the Hell Creek Formation in Montana in 1902, comprising approximately 34 fossilized bones. Writing at the time Brown said "Quarry No. 1 contains the femur, pubes, humerus, three vertebrae and two undetermined bones of a large Carnivorous Dinosaur not described by Othniel Charles Marsh, Marsh.... I have never seen anything like it from the Cretaceous". Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, named the second skeleton ''T. rex'' in 1905. The generic name is derived from the Greek language, Greek words ''τύραννος'' (''tyrannos'', meaning "tyrant") and ''wikt:σαῦρος, σαῦρος'' (''sauros'', meaning "lizard"). Osborn used the Latin language, Latin word ''rex'', meaning "king", for the specific name. The full Binomial nomenclature, binomial therefore translates to "tyrant lizard the king" or "King Tyrant Lizard", emphasizing the animal's size and perceived dominance over other species of the time.

Osborn named the other specimen ''Dynamosaurus imperiosus'' in a paper in 1905. In 1906, Osborn recognized that the two skeletons were from the same species and selected ''Tyrannosaurus'' as the preferred name. The original ''Dynamosaurus'' material resides in the collections of the Natural History Museum, London, Natural History Museum, London. In 1941, the ''T. rex'' type specimen was sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for $7,000. ''Dynamosaurus'' would later be honored by the 2018 description of another species of tyrannosaurid by Andrew McDonald and colleagues, ''Dynamoterror dynastes'', whose name was chosen in reference to the 1905 name, as it had been a "childhood favorite" of McDonald's.

From the 1910s through the end of the 1950s, Barnum's discoveries remained the only specimens of ''Tyrannosaurus'', as the Great Depression and wars kept many paleontologists out of the field.

Osborn named the other specimen ''Dynamosaurus imperiosus'' in a paper in 1905. In 1906, Osborn recognized that the two skeletons were from the same species and selected ''Tyrannosaurus'' as the preferred name. The original ''Dynamosaurus'' material resides in the collections of the Natural History Museum, London, Natural History Museum, London. In 1941, the ''T. rex'' type specimen was sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for $7,000. ''Dynamosaurus'' would later be honored by the 2018 description of another species of tyrannosaurid by Andrew McDonald and colleagues, ''Dynamoterror dynastes'', whose name was chosen in reference to the 1905 name, as it had been a "childhood favorite" of McDonald's.

From the 1910s through the end of the 1950s, Barnum's discoveries remained the only specimens of ''Tyrannosaurus'', as the Great Depression and wars kept many paleontologists out of the field.

Beginning in the 1960s, there was renewed interest in ''Tyrannosaurus'', resulting in the recovery of 42 skeletons (5–80% complete by bone count) from Western North America. In 1967, Dr. William MacMannis located and recovered the skeleton named "MOR 008", which is 15% complete by bone count and has a reconstructed skull displayed at the Museum of the Rockies. The 1990s saw numerous discoveries, with nearly twice as many finds as in all previous years, including two of the most complete skeletons found to date: Sue (dinosaur), Sue and Stan (dinosaur), Stan.

Sue Hendrickson, an amateur paleontologist, discovered the most complete (approximately 85%) and largest ''Tyrannosaurus'' skeleton in the Hell Creek Formation on August 12, 1990. The specimen Sue, named after the discoverer, was the object of a legal battle over its ownership. In 1997, the litigation was settled in favor of Maurice Williams, the original land owner. The fossil collection was purchased by the Field Museum of Natural History at auction for $7.6 million, making it the most expensive dinosaur skeleton until the sale of Stan for $31.8 million in 2020. From 1998 to 1999, Field Museum of Natural History staff spent over 25,000 hours taking the rock off the bones. The bones were then shipped to New Jersey where the mount was constructed, then shipped back to Chicago for the final assembly. The mounted skeleton opened to the public on May 17, 2000, in the Field Museum of Natural History. A study of this specimen's fossilized bones showed that Sue reached full size at age 19 and died at the age of 28, the longest estimated life of any tyrannosaur known.

Beginning in the 1960s, there was renewed interest in ''Tyrannosaurus'', resulting in the recovery of 42 skeletons (5–80% complete by bone count) from Western North America. In 1967, Dr. William MacMannis located and recovered the skeleton named "MOR 008", which is 15% complete by bone count and has a reconstructed skull displayed at the Museum of the Rockies. The 1990s saw numerous discoveries, with nearly twice as many finds as in all previous years, including two of the most complete skeletons found to date: Sue (dinosaur), Sue and Stan (dinosaur), Stan.

Sue Hendrickson, an amateur paleontologist, discovered the most complete (approximately 85%) and largest ''Tyrannosaurus'' skeleton in the Hell Creek Formation on August 12, 1990. The specimen Sue, named after the discoverer, was the object of a legal battle over its ownership. In 1997, the litigation was settled in favor of Maurice Williams, the original land owner. The fossil collection was purchased by the Field Museum of Natural History at auction for $7.6 million, making it the most expensive dinosaur skeleton until the sale of Stan for $31.8 million in 2020. From 1998 to 1999, Field Museum of Natural History staff spent over 25,000 hours taking the rock off the bones. The bones were then shipped to New Jersey where the mount was constructed, then shipped back to Chicago for the final assembly. The mounted skeleton opened to the public on May 17, 2000, in the Field Museum of Natural History. A study of this specimen's fossilized bones showed that Sue reached full size at age 19 and died at the age of 28, the longest estimated life of any tyrannosaur known.

Another ''Tyrannosaurus'', nicknamed Stan (BHI 3033), in honor of amateur paleontologist Stan Sacrison, was recovered from the Hell Creek Formation in 1992. Stan is the second most complete skeleton found, with 199 bones recovered representing 70% of the total. This tyrannosaur also had many bone pathologies, including broken and healed ribs, a broken (and healed) neck, and a substantial hole in the back of its head, about the size of a ''Tyrannosaurus'' tooth.

In 1998, Bucky Derflinger noticed a ''T. rex'' toe exposed above ground, making Derflinger, who was 20 years old at the time, the youngest person to discover a ''Tyrannosaurus''. The specimen, dubbed Specimens of Tyrannosaurus#"Bucky": TCM 2001.90.1, Bucky in honor of its discoverer, was a young adult, tall and long. Bucky is the first ''Tyrannosaurus'' to be found that preserved a furcula (wishbone). Bucky is permanently displayed at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis.

Another ''Tyrannosaurus'', nicknamed Stan (BHI 3033), in honor of amateur paleontologist Stan Sacrison, was recovered from the Hell Creek Formation in 1992. Stan is the second most complete skeleton found, with 199 bones recovered representing 70% of the total. This tyrannosaur also had many bone pathologies, including broken and healed ribs, a broken (and healed) neck, and a substantial hole in the back of its head, about the size of a ''Tyrannosaurus'' tooth.

In 1998, Bucky Derflinger noticed a ''T. rex'' toe exposed above ground, making Derflinger, who was 20 years old at the time, the youngest person to discover a ''Tyrannosaurus''. The specimen, dubbed Specimens of Tyrannosaurus#"Bucky": TCM 2001.90.1, Bucky in honor of its discoverer, was a young adult, tall and long. Bucky is the first ''Tyrannosaurus'' to be found that preserved a furcula (wishbone). Bucky is permanently displayed at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis.

In the summer of 2000, crews organized by Jack Horner (paleontologist), Jack Horner discovered five ''Tyrannosaurus'' skeletons near the Fort Peck Reservoir. In 2001, a 50% complete skeleton of a juvenile ''Tyrannosaurus'' was discovered in the Hell Creek Formation by a crew from the Burpee Museum of Natural History. Dubbed Jane (BMRP 2002.4.1), the find was thought to be the first known skeleton of a pygmy tyrannosaurid, ''Nanotyrannus'', but subsequent research revealed that it is more likely a juvenile ''Tyrannosaurus'', and the most complete juvenile example known; Jane is exhibited at the Burpee Museum of Natural History. In 2002, a skeleton named Wyrex, discovered by amateur collectors Dan Wells and Don Wyrick, had 114 bones and was 38% complete. The dig was concluded over 3 weeks in 2004 by the Black Hills Institute with the first live online ''Tyrannosaurus'' excavation providing daily reports, photos, and video.

In 2006, Montana State University revealed that it possessed the largest ''Tyrannosaurus'' skull yet discovered (from a specimen named MOR 008), measuring long. Subsequent comparisons indicated that the longest head was (from specimen LACM 23844) and the widest head was (from Sue).

In the summer of 2000, crews organized by Jack Horner (paleontologist), Jack Horner discovered five ''Tyrannosaurus'' skeletons near the Fort Peck Reservoir. In 2001, a 50% complete skeleton of a juvenile ''Tyrannosaurus'' was discovered in the Hell Creek Formation by a crew from the Burpee Museum of Natural History. Dubbed Jane (BMRP 2002.4.1), the find was thought to be the first known skeleton of a pygmy tyrannosaurid, ''Nanotyrannus'', but subsequent research revealed that it is more likely a juvenile ''Tyrannosaurus'', and the most complete juvenile example known; Jane is exhibited at the Burpee Museum of Natural History. In 2002, a skeleton named Wyrex, discovered by amateur collectors Dan Wells and Don Wyrick, had 114 bones and was 38% complete. The dig was concluded over 3 weeks in 2004 by the Black Hills Institute with the first live online ''Tyrannosaurus'' excavation providing daily reports, photos, and video.

In 2006, Montana State University revealed that it possessed the largest ''Tyrannosaurus'' skull yet discovered (from a specimen named MOR 008), measuring long. Subsequent comparisons indicated that the longest head was (from specimen LACM 23844) and the widest head was (from Sue).

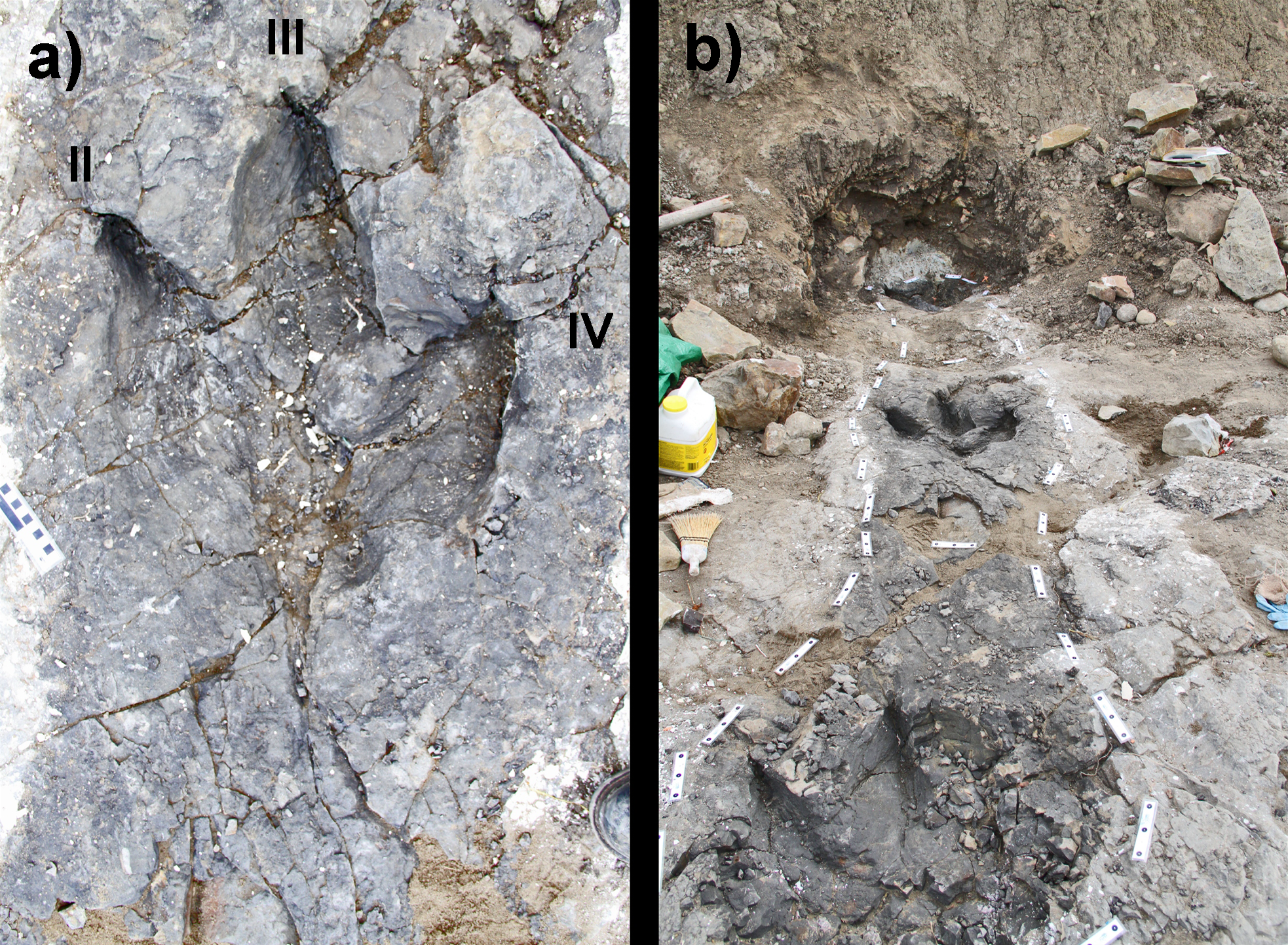

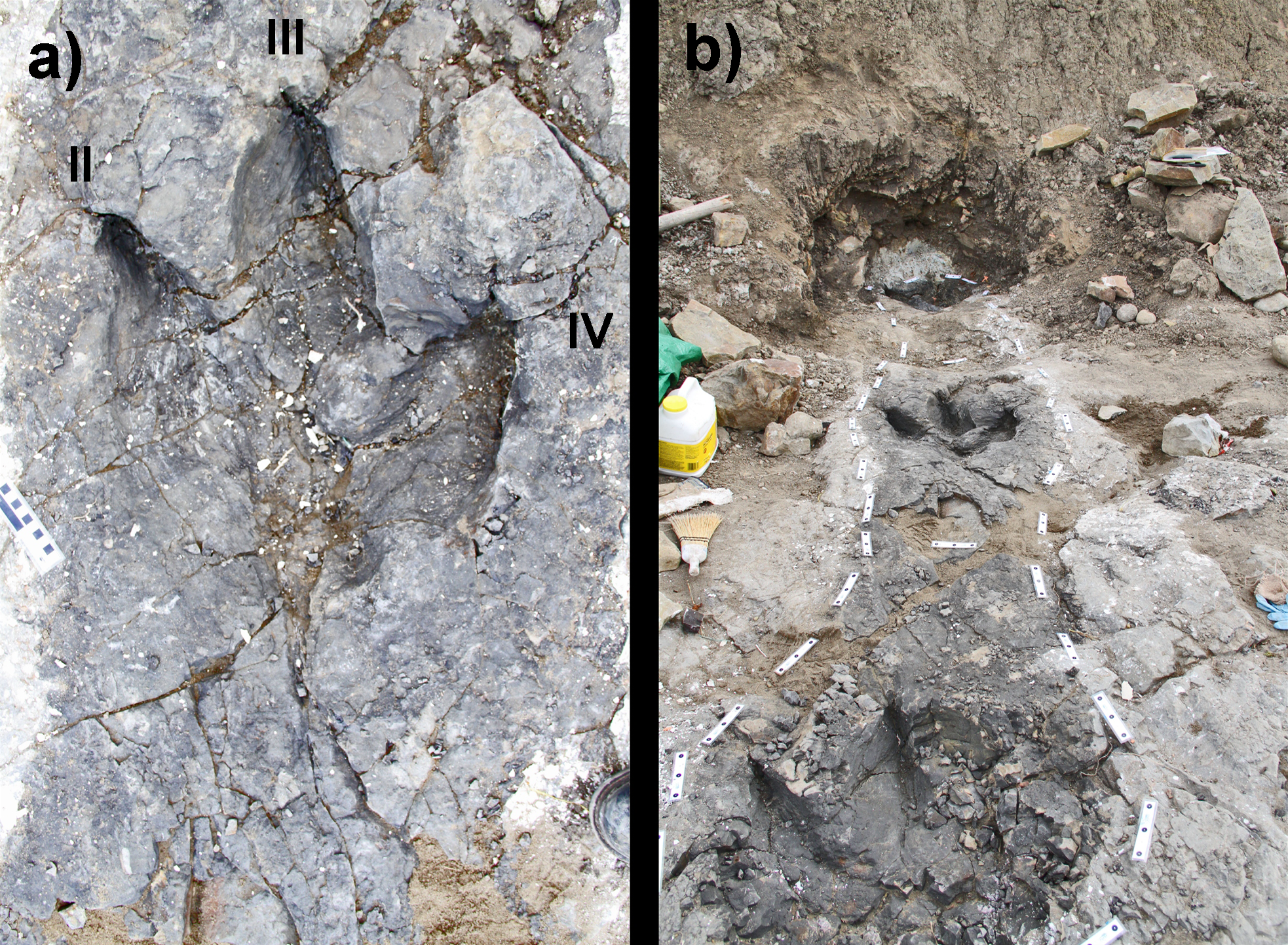

Two isolated fossilized footprints have been tentatively assigned to ''T. rex''. The first was discovered at Philmont Scout Ranch, New Mexico, in 1983 by American geologist Charles Pillmore. Originally thought to belong to a hadrosaurid, examination of the footprint revealed a large 'heel' unknown in ornithopod dinosaur tracks, and traces of what may have been a hallux, the dewclaw-like fourth digit of the tyrannosaur foot. The footprint was published as the ichnogenus ''Tyrannosauripus pillmorei'' in 1994, by Martin Lockley and Adrian Hunt. Lockley and Hunt suggested that it was very likely the track was made by a ''T. rex'', which would make it the first known footprint from this species. The track was made in what was once a vegetated wetland mudflat. It measures long by wide.

A second footprint that may have been made by a ''Tyrannosaurus'' was first reported in 2007 by British paleontologist Phil Manning, from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana. This second track measures long, shorter than the track described by Lockley and Hunt. Whether or not the track was made by ''Tyrannosaurus'' is unclear, though ''Tyrannosaurus'' is the only large theropod known to have existed in the Hell Creek Formation.

A set of footprints in Glenrock, Wyoming dating to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous and hailing from the Lance Formation were described by Scott Persons, Phil Currie and colleagues in 2016, and are believed to belong to either a juvenile ''T. rex'' or the dubious tyrannosaurid ''Nanotyrannus lancensis''. From measurements and based on the positions of the footprints, the animal was believed to be traveling at a walking speed of around 2.8 to 5 miles per hour and was estimated to have a hip height of to . A follow-up paper appeared in 2017, increasing the speed estimations by 50–80%.

Two isolated fossilized footprints have been tentatively assigned to ''T. rex''. The first was discovered at Philmont Scout Ranch, New Mexico, in 1983 by American geologist Charles Pillmore. Originally thought to belong to a hadrosaurid, examination of the footprint revealed a large 'heel' unknown in ornithopod dinosaur tracks, and traces of what may have been a hallux, the dewclaw-like fourth digit of the tyrannosaur foot. The footprint was published as the ichnogenus ''Tyrannosauripus pillmorei'' in 1994, by Martin Lockley and Adrian Hunt. Lockley and Hunt suggested that it was very likely the track was made by a ''T. rex'', which would make it the first known footprint from this species. The track was made in what was once a vegetated wetland mudflat. It measures long by wide.

A second footprint that may have been made by a ''Tyrannosaurus'' was first reported in 2007 by British paleontologist Phil Manning, from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana. This second track measures long, shorter than the track described by Lockley and Hunt. Whether or not the track was made by ''Tyrannosaurus'' is unclear, though ''Tyrannosaurus'' is the only large theropod known to have existed in the Hell Creek Formation.

A set of footprints in Glenrock, Wyoming dating to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous and hailing from the Lance Formation were described by Scott Persons, Phil Currie and colleagues in 2016, and are believed to belong to either a juvenile ''T. rex'' or the dubious tyrannosaurid ''Nanotyrannus lancensis''. From measurements and based on the positions of the footprints, the animal was believed to be traveling at a walking speed of around 2.8 to 5 miles per hour and was estimated to have a hip height of to . A follow-up paper appeared in 2017, increasing the speed estimations by 50–80%.

''T. rex'' was one of the largest land carnivores of all time. One of the largest and the most complete specimens, nicknamed Sue (dinosaur), Sue (FMNH PR2081), is located at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Sue measured long, was tall at the hips, and according to the most recent studies, using a variety of techniques, maximum body masses have been estimated approximately . A specimen nicknamed Scotty (T. rex), Scotty (RSM P2523.8), located at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, is reported to measure in length. Using a mass estimation technique that extrapolates from the circumference of the femur, Scotty was estimated as the largest known specimen at in body mass.

Not every adult ''Tyrannosaurus'' specimen recovered is as big. Historically average adult mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from as low as , to more than , with most modern estimates ranging between and .

''T. rex'' was one of the largest land carnivores of all time. One of the largest and the most complete specimens, nicknamed Sue (dinosaur), Sue (FMNH PR2081), is located at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Sue measured long, was tall at the hips, and according to the most recent studies, using a variety of techniques, maximum body masses have been estimated approximately . A specimen nicknamed Scotty (T. rex), Scotty (RSM P2523.8), located at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, is reported to measure in length. Using a mass estimation technique that extrapolates from the circumference of the femur, Scotty was estimated as the largest known specimen at in body mass.

Not every adult ''Tyrannosaurus'' specimen recovered is as big. Historically average adult mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from as low as , to more than , with most modern estimates ranging between and .

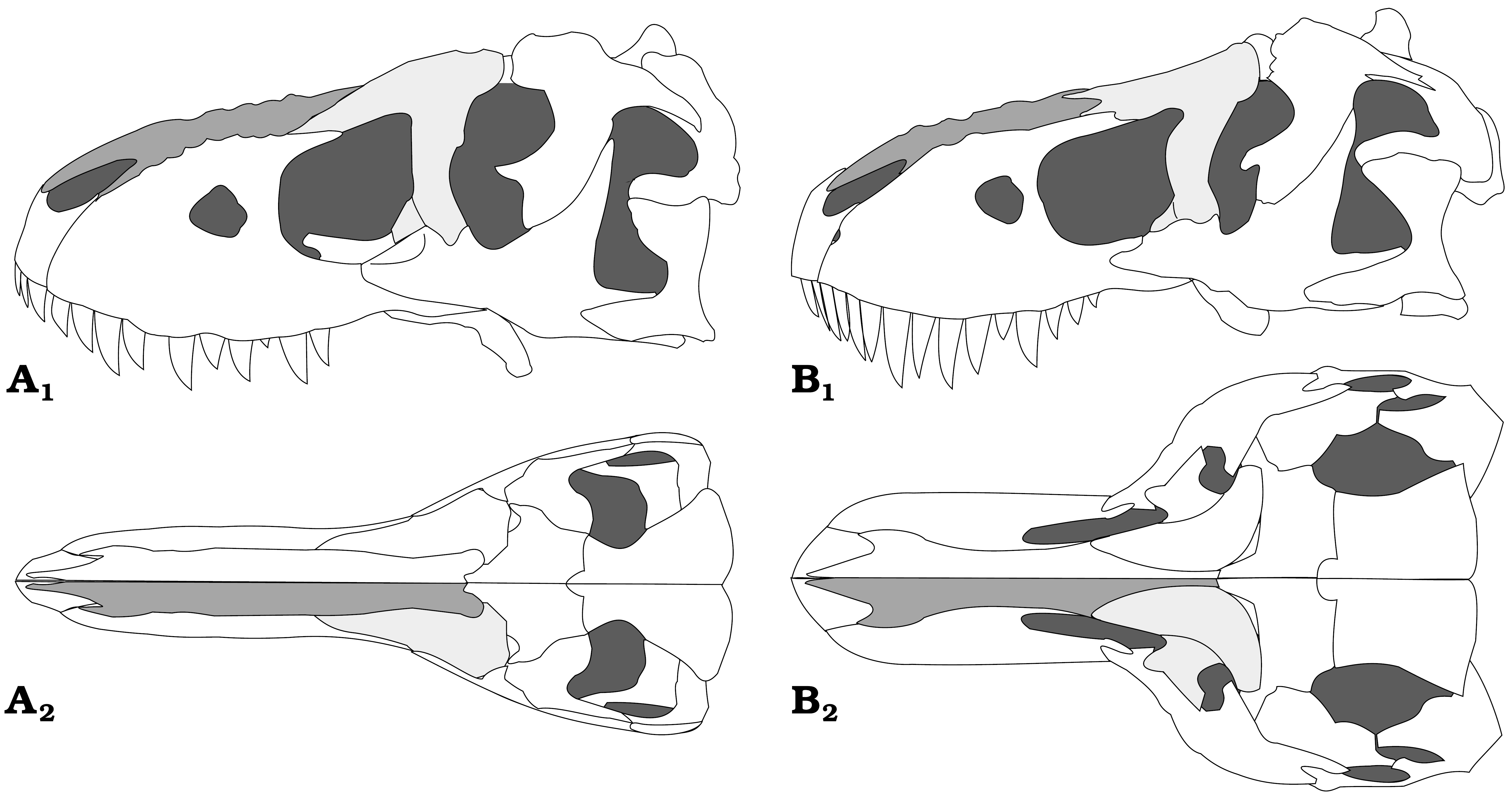

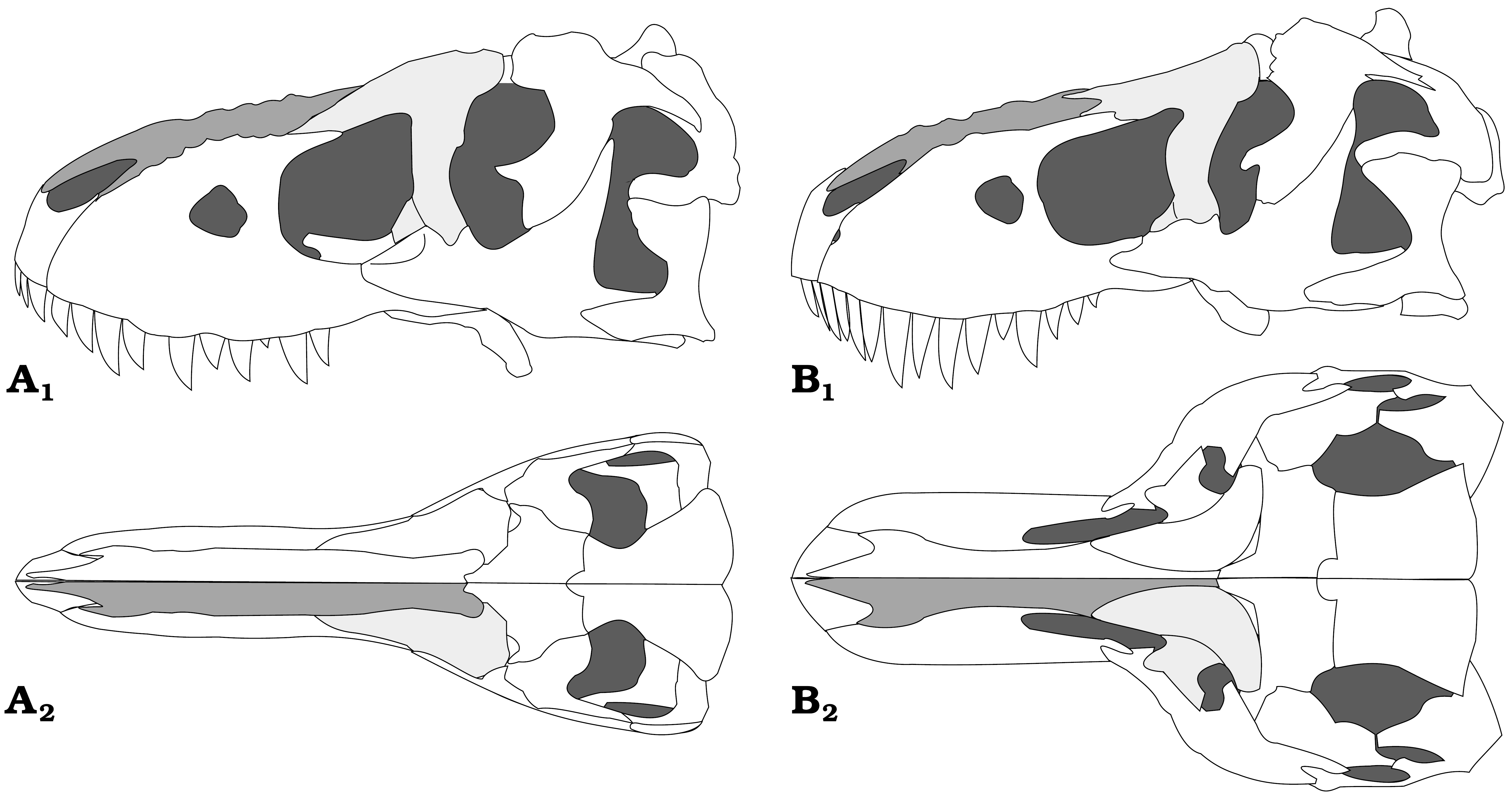

The largest known ''T. rex'' skulls measure up to in length. Large Fenestra (anatomy), fenestrae (openings) in the skull reduced weight, as in all carnivorous theropods. In other respects ''Tyrannosaurus''

The largest known ''T. rex'' skulls measure up to in length. Large Fenestra (anatomy), fenestrae (openings) in the skull reduced weight, as in all carnivorous theropods. In other respects ''Tyrannosaurus''' s skull was significantly different from those of large non-tyrannosaurid theropods. It was extremely wide at the rear but had a narrow snout, allowing unusually good binocular vision. The skull bones were massive and the nasal bone, nasals and some other bones were fused, preventing movement between them; but many were Pneumatized bones, pneumatized (contained a "honeycomb" of tiny air spaces) and thus lighter. These and other skull-strengthening features are part of the tyrannosaurid trend towards an increasingly powerful bite, which easily surpassed that of all non-tyrannosaurids. The tip of the upper jaw was U-shaped (most non-tyrannosauroid carnivores had V-shaped upper jaws), which increased the amount of tissue and bone a tyrannosaur could rip out with one bite, although it also increased the stresses on the front teeth.

The teeth of ''T. rex'' displayed marked heterodonty (differences in shape). The premaxillary teeth, four per side at the front of the upper jaw, were closely packed, ''D''-shaped in cross-section, had reinforcing ridges on the rear surface, were Incisor, incisiform (their tips were chisel-like blades) and curved backwards. The ''D''-shaped cross-section, reinforcing ridges and backwards curve reduced the risk that the teeth would snap when ''Tyrannosaurus'' bit and pulled. The remaining teeth were robust, like "lethal bananas" rather than daggers, more widely spaced and also had reinforcing ridges. Those in the upper jaw, twelve per side in mature individuals, were larger than their counterparts of the lower jaw, except at the rear. The largest found so far is estimated to have been long including the root when the animal was alive, making it the largest tooth of any carnivorous dinosaur yet found. The lower jaw was robust. Its front dentary bone bore thirteen teeth. Behind the tooth row, the lower jaw became notably taller. The upper and lower jaws of ''Tyrannosaurus'', like those of many dinosaurs, possessed numerous Foramen, foramina, or small holes in the bone. Various functions have been proposed for these foramina, such as a crocodile-like sensory system or evidence of Integument, extra-oral structures such as scales or potentially lips.

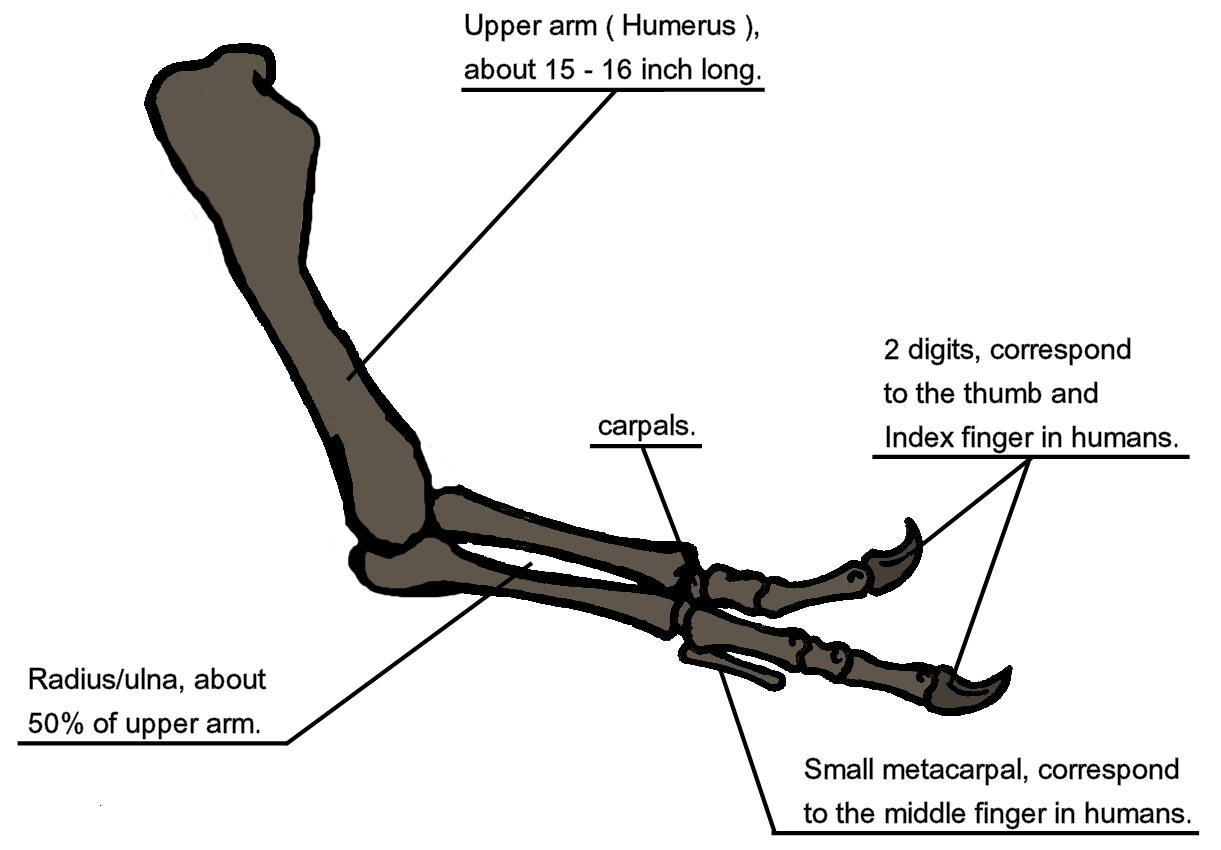

The shoulder girdle was longer than the entire forelimb. The shoulder blade had a narrow shaft but was exceptionally expanded at its upper end. It connected via a long forward protrusion to the coracoid, which was rounded. Both shoulder blades were connected by a small furcula. The paired breast bones possibly were made of cartilage only.

The forelimb or arm was very short. The upper arm bone, the humerus, was short but robust. It had a narrow upper end with an exceptionally rounded head. The lower arm bones, the ulna and radius, were straight elements, much shorter than the humerus. The second metacarpus, metacarpal was longer and wider than the first, whereas normally in theropods the opposite is true. The forelimbs had only two clawed fingers, along with an additional splint-like small third metacarpus, metacarpal representing the remnant of a third digit.

The shoulder girdle was longer than the entire forelimb. The shoulder blade had a narrow shaft but was exceptionally expanded at its upper end. It connected via a long forward protrusion to the coracoid, which was rounded. Both shoulder blades were connected by a small furcula. The paired breast bones possibly were made of cartilage only.

The forelimb or arm was very short. The upper arm bone, the humerus, was short but robust. It had a narrow upper end with an exceptionally rounded head. The lower arm bones, the ulna and radius, were straight elements, much shorter than the humerus. The second metacarpus, metacarpal was longer and wider than the first, whereas normally in theropods the opposite is true. The forelimbs had only two clawed fingers, along with an additional splint-like small third metacarpus, metacarpal representing the remnant of a third digit.

The pelvis was a large structure. Its upper bone, the Ilium (bone), ilium, was both very long and high, providing an extensive attachment area for hindlimb muscles. The front pubic bone ended in an enormous pubic boot, longer than the entire shaft of the element. The rear ischium was slender and straight, pointing obliquely to behind and below.

In contrast to the arms, the hindlimbs were among the longest in proportion to body size of any theropod. In the foot, the metatarsus was "arctometatarsalian", meaning that the part of the third metatarsal near the ankle was pinched. The third metatarsal was also exceptionally sinuous. Compensating for the immense bulk of the animal, many bones throughout the skeleton were hollowed, reducing its weight without significant loss of strength.

The pelvis was a large structure. Its upper bone, the Ilium (bone), ilium, was both very long and high, providing an extensive attachment area for hindlimb muscles. The front pubic bone ended in an enormous pubic boot, longer than the entire shaft of the element. The rear ischium was slender and straight, pointing obliquely to behind and below.

In contrast to the arms, the hindlimbs were among the longest in proportion to body size of any theropod. In the foot, the metatarsus was "arctometatarsalian", meaning that the part of the third metatarsal near the ankle was pinched. The third metatarsal was also exceptionally sinuous. Compensating for the immense bulk of the animal, many bones throughout the skeleton were hollowed, reducing its weight without significant loss of strength.

''Tyrannosaurus'' is the Type (biology), type genus of the superfamily Tyrannosauroidea, the Family (biology), family Tyrannosauridae, and the subfamily Tyrannosaurinae; in other words it is the standard by which paleontologists decide whether to include other species in the same group. Other members of the tyrannosaurine subfamily include the North American ''Daspletosaurus'' and the Asian ''Tarbosaurus'', both of which have occasionally been synonymized with ''Tyrannosaurus''. Tyrannosaurids were once commonly thought to be descendants of earlier large theropods such as Spinosauroidea, megalosaurs and Carnosauria, carnosaurs, although more recently they were reclassified with the generally smaller Coelurosauria, coelurosaurs.

Many phylogeny, phylogenetic analyses have found ''Tarbosaurus bataar'' to be the sister taxon of ''T. rex''. The discovery of the tyrannosaurid ''Lythronax'' further indicates that ''Tarbosaurus'' and ''Tyrannosaurus'' are closely related, forming a clade with fellow Asian tyrannosaurid ''Zhuchengtyrannus'', with ''Lythronax'' being their sister taxon. A further study from 2016 by Steve Brusatte, Thomas Carr and colleagues, also indicates that ''Tyrannosaurus'' may have been an immigrant from Asia, as well as a possible descendant of ''Tarbosaurus''.

Below is the cladogram of Tyrannosauridae based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Loewen and colleagues in 2013.

''Tyrannosaurus'' is the Type (biology), type genus of the superfamily Tyrannosauroidea, the Family (biology), family Tyrannosauridae, and the subfamily Tyrannosaurinae; in other words it is the standard by which paleontologists decide whether to include other species in the same group. Other members of the tyrannosaurine subfamily include the North American ''Daspletosaurus'' and the Asian ''Tarbosaurus'', both of which have occasionally been synonymized with ''Tyrannosaurus''. Tyrannosaurids were once commonly thought to be descendants of earlier large theropods such as Spinosauroidea, megalosaurs and Carnosauria, carnosaurs, although more recently they were reclassified with the generally smaller Coelurosauria, coelurosaurs.

Many phylogeny, phylogenetic analyses have found ''Tarbosaurus bataar'' to be the sister taxon of ''T. rex''. The discovery of the tyrannosaurid ''Lythronax'' further indicates that ''Tarbosaurus'' and ''Tyrannosaurus'' are closely related, forming a clade with fellow Asian tyrannosaurid ''Zhuchengtyrannus'', with ''Lythronax'' being their sister taxon. A further study from 2016 by Steve Brusatte, Thomas Carr and colleagues, also indicates that ''Tyrannosaurus'' may have been an immigrant from Asia, as well as a possible descendant of ''Tarbosaurus''.

Below is the cladogram of Tyrannosauridae based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Loewen and colleagues in 2013.

In 1955, Soviet paleontology, paleontologist Evgeny Maleev named a new species, ''Tyrannosaurus bataar'', from Mongolia. By 1965, this species was renamed as a distinct genus, ''Tarbosaurus bataar''. While most palaeontologists continue to maintain the two as distinct genera, some authors such as Thomas Holtz, Kenneth Carpenter, and Thomas Carr (paleontologist), Thomas Carr argue that the two species are similar enough to be considered members of the same genus, with the Mongolian taxon having the resulting binomial nomenclature, binomial of ''Tyrannosaurus bataar''.

In 2001, various tyrannosaurid teeth and a metatarsal unearthed in a quarry near Zhucheng, China were assigned by Chinese paleontologist Hu Chengzhi to the newly erected species ''Tyrannosaurus zhuchengensis''. However, in a nearby site, a right maxilla and left jawbone were assigned to the newly erected tyrannosaurid genus ''Zhuchengtyrannus'' in 2011. It is possible that ''T. zhuchengensis'' is synonym (taxonomy), synonymous with ''Zhuchengtyrannus''. In any case, ''T. zhuchengensis'' is considered to be a ''nomen dubium'' as the holotype lacks diagnosis (taxonomy), diagnostic features below the level Tyrannosaurinae.

In a 2022 study, Gregory S. Paul and colleagues argued that ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', as traditionally understood, actually represents three species: the type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', and two new species: ''T. imperator'' (meaning "tyrant lizard emperor") and ''T. regina'' (meaning "tyrant lizard queen"). The holotype of the former (''T. imperator'') is the Sue specimen, and the holotype of the latter (''T. regina'') is Wankel rex. The division into multiple species was primarily based on the observation of a very high degree of variation in the proportions and robusticity of the femur (and other skeletal elements) across catalogued ''T. rex'' specimens, more so than that observed in other theropods recognized as one species. Differences of general body proportions representing robust and gracile morphotypes was also used as a line of evidence, in addition to the number of small, slender incisiform teeth in the dentary, as based on tooth sockets. Specifically, the paper's ''T. rex'' was distinguished by robust anatomy, a moderate ratio of femur length vs circumference, and the possession of a singular slender incisiform dentary tooth; ''T. imperator'' was considered to be robust with a small femur length to circumference ratio and two of the slender teeth; and ''T. regina'' was a gracile form with a high femur ratio and one of the slender teeth. It was observed that variation in proportions and robustness became more extreme higher up in the sample, Stratigraphy, stratigraphically. This was interpreted as a single earlier population, ''T. imperator'', speciating into more than one taxon, ''T. rex'' and ''T. regina''.

However, several other leading paleontologists, including Stephen Brusatte, Thomas Carr (paleontologist), Thomas Carr, Thomas Holtz, David Hone, Jingmai O'Connor, and Lindsay Zanno, criticized the study or expressed skepticism of its conclusions when approached by various media outlets for comment. Their criticism was subsequently published in a technical paper.Carr T.D., Napoli J.G., Brusatte S.L., Holtz T.R., Hone D.W.E., Williamson T.E. & Zanno L.E. (2022). “Insufficient Evidence for Multiple Species of Tyrannosaurus in the Latest Cretaceous of North America: A Comment on “The Tyrant Lizard King, Queen and Emperor: Multiple Lines of Morphological and Stratigraphic Evidence Support Subtle Evolution and Probable Speciation Within the North American Genus Tyrannosaurus””. ''Evolutionary Biology'' 49(3): p. 314-341: doi.org/10.1007/s11692-022-09573-1 Holtz and Zanno both remarked that it was plausible that more than one species of ''Tyrannosaurus'' existed, but felt the new study was insufficient to support the species it proposed. Holtz remarked that, even if ''Tyrannosaurus imperator'' represented a distinct species from ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', it may represent the same species as ''Nanotyrannus lancensis'' and would need to be called ''Tyrannosaurus lancensis''. O'Connor, a curator at the Field Museum, where the ''T. imperator'' holotype Sue is displayed, regarded the new species as too poorly-supported to justify modifying the exhibit signs. Brusatte, Carr, and O'Connor viewed the distinguishing features proposed between the species as reflecting natural variation within a species. Both Carr and O'Connor expressed concerns about the study's inability to determine which of the proposed species several well-preserved specimens belonged to. Another paleontologist, Philip J. Currie, originally co-authored the study but withdrew from it as he did not want to be involved in naming the new species.

In 1955, Soviet paleontology, paleontologist Evgeny Maleev named a new species, ''Tyrannosaurus bataar'', from Mongolia. By 1965, this species was renamed as a distinct genus, ''Tarbosaurus bataar''. While most palaeontologists continue to maintain the two as distinct genera, some authors such as Thomas Holtz, Kenneth Carpenter, and Thomas Carr (paleontologist), Thomas Carr argue that the two species are similar enough to be considered members of the same genus, with the Mongolian taxon having the resulting binomial nomenclature, binomial of ''Tyrannosaurus bataar''.

In 2001, various tyrannosaurid teeth and a metatarsal unearthed in a quarry near Zhucheng, China were assigned by Chinese paleontologist Hu Chengzhi to the newly erected species ''Tyrannosaurus zhuchengensis''. However, in a nearby site, a right maxilla and left jawbone were assigned to the newly erected tyrannosaurid genus ''Zhuchengtyrannus'' in 2011. It is possible that ''T. zhuchengensis'' is synonym (taxonomy), synonymous with ''Zhuchengtyrannus''. In any case, ''T. zhuchengensis'' is considered to be a ''nomen dubium'' as the holotype lacks diagnosis (taxonomy), diagnostic features below the level Tyrannosaurinae.

In a 2022 study, Gregory S. Paul and colleagues argued that ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', as traditionally understood, actually represents three species: the type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', and two new species: ''T. imperator'' (meaning "tyrant lizard emperor") and ''T. regina'' (meaning "tyrant lizard queen"). The holotype of the former (''T. imperator'') is the Sue specimen, and the holotype of the latter (''T. regina'') is Wankel rex. The division into multiple species was primarily based on the observation of a very high degree of variation in the proportions and robusticity of the femur (and other skeletal elements) across catalogued ''T. rex'' specimens, more so than that observed in other theropods recognized as one species. Differences of general body proportions representing robust and gracile morphotypes was also used as a line of evidence, in addition to the number of small, slender incisiform teeth in the dentary, as based on tooth sockets. Specifically, the paper's ''T. rex'' was distinguished by robust anatomy, a moderate ratio of femur length vs circumference, and the possession of a singular slender incisiform dentary tooth; ''T. imperator'' was considered to be robust with a small femur length to circumference ratio and two of the slender teeth; and ''T. regina'' was a gracile form with a high femur ratio and one of the slender teeth. It was observed that variation in proportions and robustness became more extreme higher up in the sample, Stratigraphy, stratigraphically. This was interpreted as a single earlier population, ''T. imperator'', speciating into more than one taxon, ''T. rex'' and ''T. regina''.

However, several other leading paleontologists, including Stephen Brusatte, Thomas Carr (paleontologist), Thomas Carr, Thomas Holtz, David Hone, Jingmai O'Connor, and Lindsay Zanno, criticized the study or expressed skepticism of its conclusions when approached by various media outlets for comment. Their criticism was subsequently published in a technical paper.Carr T.D., Napoli J.G., Brusatte S.L., Holtz T.R., Hone D.W.E., Williamson T.E. & Zanno L.E. (2022). “Insufficient Evidence for Multiple Species of Tyrannosaurus in the Latest Cretaceous of North America: A Comment on “The Tyrant Lizard King, Queen and Emperor: Multiple Lines of Morphological and Stratigraphic Evidence Support Subtle Evolution and Probable Speciation Within the North American Genus Tyrannosaurus””. ''Evolutionary Biology'' 49(3): p. 314-341: doi.org/10.1007/s11692-022-09573-1 Holtz and Zanno both remarked that it was plausible that more than one species of ''Tyrannosaurus'' existed, but felt the new study was insufficient to support the species it proposed. Holtz remarked that, even if ''Tyrannosaurus imperator'' represented a distinct species from ''Tyrannosaurus rex'', it may represent the same species as ''Nanotyrannus lancensis'' and would need to be called ''Tyrannosaurus lancensis''. O'Connor, a curator at the Field Museum, where the ''T. imperator'' holotype Sue is displayed, regarded the new species as too poorly-supported to justify modifying the exhibit signs. Brusatte, Carr, and O'Connor viewed the distinguishing features proposed between the species as reflecting natural variation within a species. Both Carr and O'Connor expressed concerns about the study's inability to determine which of the proposed species several well-preserved specimens belonged to. Another paleontologist, Philip J. Currie, originally co-authored the study but withdrew from it as he did not want to be involved in naming the new species.

Other tyrannosaurid fossils found in the same formations as ''T. rex'' were originally classified as separate taxa, including ''Aublysodon'' and ''Albertosaurus megagracilis'', the latter being named ''Dinotyrannus megagracilis'' in 1995. These fossils are now universally considered to belong to juvenile ''T. rex''. A small but nearly complete skull from Montana, long, might be an exception. This skull, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, CMNH 7541, was originally classified as a species of ''Gorgosaurus'' (''G. lancensis'') by Charles W. Gilmore in 1946. In 1988, the specimen was re-described by Robert T. Bakker, Philip J. Currie, Phil Currie, and Michael Williams, then the curator of paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where the original specimen was housed and is now on display. Their initial research indicated that the skull bones were fused, and that it therefore represented an adult specimen. In light of this, Bakker and colleagues assigned the skull to a new genus named ''Nanotyrannus'' (meaning "dwarf tyrant", for its apparently small adult size). The specimen is estimated to have been around long when it died. However, In 1999, a detailed analysis by Thomas Carr (paleontologist), Thomas Carr revealed the specimen to be a juvenile, leading Carr and many other paleontologists to consider it a juvenile ''T. rex'' individual.

Other tyrannosaurid fossils found in the same formations as ''T. rex'' were originally classified as separate taxa, including ''Aublysodon'' and ''Albertosaurus megagracilis'', the latter being named ''Dinotyrannus megagracilis'' in 1995. These fossils are now universally considered to belong to juvenile ''T. rex''. A small but nearly complete skull from Montana, long, might be an exception. This skull, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, CMNH 7541, was originally classified as a species of ''Gorgosaurus'' (''G. lancensis'') by Charles W. Gilmore in 1946. In 1988, the specimen was re-described by Robert T. Bakker, Philip J. Currie, Phil Currie, and Michael Williams, then the curator of paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where the original specimen was housed and is now on display. Their initial research indicated that the skull bones were fused, and that it therefore represented an adult specimen. In light of this, Bakker and colleagues assigned the skull to a new genus named ''Nanotyrannus'' (meaning "dwarf tyrant", for its apparently small adult size). The specimen is estimated to have been around long when it died. However, In 1999, a detailed analysis by Thomas Carr (paleontologist), Thomas Carr revealed the specimen to be a juvenile, leading Carr and many other paleontologists to consider it a juvenile ''T. rex'' individual.

In 2001, a more complete juvenile tyrannosaur (nicknamed "Jane (dinosaur), Jane", catalog number BMRP 2002.4.1), belonging to the same species as the original ''Nanotyrannus'' specimen, was uncovered. This discovery prompted a conference on tyrannosaurs focused on the issues of ''Nanotyrannus'' validity at the Burpee Museum of Natural History in 2005. Several paleontologists who had previously published opinions that ''N. lancensis'' was a valid species, including Currie and Williams, saw the discovery of "Jane" as a confirmation that ''Nanotyrannus'' was, in fact, a juvenile ''T. rex''.Currie, Henderson, Horner and Williams (2005). "On tyrannosaur teeth, tooth positions and the taxonomic status of ''Nanotyrannus lancensis''." In "The origin, systematics, and paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae", a symposium hosted jointly by Burpee Museum of Natural History and Northern Illinois University.Henderson (2005). "Nano No More: The death of the pygmy tyrant." In "The origin, systematics, and paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae", a symposium hosted jointly by Burpee Museum of Natural History and Northern Illinois University. Peter Larson continued to support the hypothesis that ''N''. ''lancensis'' was a separate but closely related species, based on skull features such as two more teeth in both jaws than ''T. rex''; as well as proportionately larger hands with phalanges on the third metacarpal and different Furcula, wishbone anatomy in an undescribed specimen. He also argued that ''Stygivenator'', generally considered to be a juvenile ''T. rex'', may be a younger ''Nanotyrannus'' specimen.Larson (2005). "A case for ''Nanotyrannus''." In "The origin, systematics, and paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae", a symposium hosted jointly by Burpee Museum of Natural History and Northern Illinois University.Larson P (2013), "The validity of Nanotyrannus Lancensis (Theropoda, Lancian – Upper Maastrichtian of North America)", Society of Vertebrate Paleontology: 73rd annual meeting, ''Abstracts with Programs'', p. 159. Later research revealed that other tyrannosaurids such as ''Gorgosaurus'' also experienced reduction in tooth count during growth, and given the disparity in tooth count between individuals of the same age group in this genus and ''Tyrannosaurus'', this feature may also be due to individual variation. In 2013, Carr noted that all of the differences claimed to support ''Nanotyrannus'' have turned out to be individually or ontogenetically variable features or products of Taphonomy, distortion of the bones.

In 2001, a more complete juvenile tyrannosaur (nicknamed "Jane (dinosaur), Jane", catalog number BMRP 2002.4.1), belonging to the same species as the original ''Nanotyrannus'' specimen, was uncovered. This discovery prompted a conference on tyrannosaurs focused on the issues of ''Nanotyrannus'' validity at the Burpee Museum of Natural History in 2005. Several paleontologists who had previously published opinions that ''N. lancensis'' was a valid species, including Currie and Williams, saw the discovery of "Jane" as a confirmation that ''Nanotyrannus'' was, in fact, a juvenile ''T. rex''.Currie, Henderson, Horner and Williams (2005). "On tyrannosaur teeth, tooth positions and the taxonomic status of ''Nanotyrannus lancensis''." In "The origin, systematics, and paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae", a symposium hosted jointly by Burpee Museum of Natural History and Northern Illinois University.Henderson (2005). "Nano No More: The death of the pygmy tyrant." In "The origin, systematics, and paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae", a symposium hosted jointly by Burpee Museum of Natural History and Northern Illinois University. Peter Larson continued to support the hypothesis that ''N''. ''lancensis'' was a separate but closely related species, based on skull features such as two more teeth in both jaws than ''T. rex''; as well as proportionately larger hands with phalanges on the third metacarpal and different Furcula, wishbone anatomy in an undescribed specimen. He also argued that ''Stygivenator'', generally considered to be a juvenile ''T. rex'', may be a younger ''Nanotyrannus'' specimen.Larson (2005). "A case for ''Nanotyrannus''." In "The origin, systematics, and paleobiology of Tyrannosauridae", a symposium hosted jointly by Burpee Museum of Natural History and Northern Illinois University.Larson P (2013), "The validity of Nanotyrannus Lancensis (Theropoda, Lancian – Upper Maastrichtian of North America)", Society of Vertebrate Paleontology: 73rd annual meeting, ''Abstracts with Programs'', p. 159. Later research revealed that other tyrannosaurids such as ''Gorgosaurus'' also experienced reduction in tooth count during growth, and given the disparity in tooth count between individuals of the same age group in this genus and ''Tyrannosaurus'', this feature may also be due to individual variation. In 2013, Carr noted that all of the differences claimed to support ''Nanotyrannus'' have turned out to be individually or ontogenetically variable features or products of Taphonomy, distortion of the bones.

In 2016, analysis of limb proportions by Persons and Currie suggested ''Nanotyrannus'' specimens to have differing cursoriality levels, potentially separating it from ''T. rex''. However, paleontologist Manabu Sakomoto has commented that this conclusion may be impacted by low Sample size determination, sample size, and the discrepancy does not necessarily reflect taxonomic distinction. In 2016, Joshua Schmerge argued for ''Nanotyrannus''

In 2016, analysis of limb proportions by Persons and Currie suggested ''Nanotyrannus'' specimens to have differing cursoriality levels, potentially separating it from ''T. rex''. However, paleontologist Manabu Sakomoto has commented that this conclusion may be impacted by low Sample size determination, sample size, and the discrepancy does not necessarily reflect taxonomic distinction. In 2016, Joshua Schmerge argued for ''Nanotyrannus''

The identification of several specimens as juvenile ''T. rex'' has allowed scientists to document ontogeny, ontogenetic changes in the species, estimate the lifespan, and determine how quickly the animals would have grown. The smallest known individual (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, LACM 28471, the "Jordan theropod") is estimated to have weighed only , while the largest, such as Field Museum of Natural History, FMNH PR2081 (Sue) most likely weighed about . Histology, Histologic analysis of ''T. rex'' bones showed LACM 28471 had aged only 2 years when it died, while Sue was 28 years old, an age which may have been close to the maximum for the species.

Histology has also allowed the age of other specimens to be determined. Growth curves can be developed when the ages of different specimens are plotted on a graph along with their mass. A ''T. rex'' growth curve is S-shaped, with juveniles remaining under until approximately 14 years of age, when body size began to increase dramatically. During this rapid growth phase, a young ''T. rex'' would gain an average of a year for the next four years. At 18 years of age, the curve plateaus again, indicating that growth slowed dramatically. For example, only separated the 28-year-old Sue from a 22-year-old Canadian specimen (Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, RTMP 81.12.1). A 2004 histological study performed by different workers corroborates these results, finding that rapid growth began to slow at around 16 years of age.

The identification of several specimens as juvenile ''T. rex'' has allowed scientists to document ontogeny, ontogenetic changes in the species, estimate the lifespan, and determine how quickly the animals would have grown. The smallest known individual (Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, LACM 28471, the "Jordan theropod") is estimated to have weighed only , while the largest, such as Field Museum of Natural History, FMNH PR2081 (Sue) most likely weighed about . Histology, Histologic analysis of ''T. rex'' bones showed LACM 28471 had aged only 2 years when it died, while Sue was 28 years old, an age which may have been close to the maximum for the species.

Histology has also allowed the age of other specimens to be determined. Growth curves can be developed when the ages of different specimens are plotted on a graph along with their mass. A ''T. rex'' growth curve is S-shaped, with juveniles remaining under until approximately 14 years of age, when body size began to increase dramatically. During this rapid growth phase, a young ''T. rex'' would gain an average of a year for the next four years. At 18 years of age, the curve plateaus again, indicating that growth slowed dramatically. For example, only separated the 28-year-old Sue from a 22-year-old Canadian specimen (Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, RTMP 81.12.1). A 2004 histological study performed by different workers corroborates these results, finding that rapid growth began to slow at around 16 years of age.

A study by Hutchinson and colleagues in 2011 corroborated the previous estimation methods in general, but their estimation of peak growth rates is significantly higher; it found that the "maximum growth rates for T. rex during the exponential stage are 1790 kg/year". Although these results were much higher than previous estimations, the authors noted that these results significantly lowered the great difference between its actual growth rate and the one which would be expected of an animal of its size. The sudden change in growth rate at the end of the growth spurt may indicate physical maturity, a hypothesis which is supported by the discovery of medullary tissue in the femur of a 16 to 20-year-old ''T. rex'' from Montana (Museum of the Rockies, MOR 1125, also known as B-rex). Medullary tissue is found only in female birds during ovulation, indicating that B-rex was of reproductive age. Further study indicates an age of 18 for this specimen. In 2016, it was finally confirmed by Mary Higby Schweitzer and Lindsay Zanno and colleagues that the soft tissue within the femur of MOR 1125 was medullary tissue. This also confirmed the identity of the specimen as a female. The discovery of medullary bone tissue within ''Tyrannosaurus'' may prove valuable in determining the sex of other dinosaur species in future examinations, as the chemical makeup of medullary tissue is unmistakable. Other tyrannosaurids exhibit extremely similar growth curves, although with lower growth rates corresponding to their lower adult sizes.

An additional study published in 2020 by Woodward and colleagues, for the journal ''Science Advances'' indicates that during their growth from juvenile to adult, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was capable of slowing down its growth to counter environmental factors such as lack of food. The study, focusing on two juvenile specimens between 13 and 15 years old housed at the Burpee Museum in Illinois, indicates that the rate of maturation for ''Tyrannosaurus'' was dependent on resource abundance. This study also indicates that in such changing environments, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was particularly well-suited to an environment that shifted yearly in regards to resource abundance, hinting that other midsize predators might have had difficulty surviving in such harsh conditions and explaining the niche partitioning between juvenile and adult tyrannosaurs. The study further indicates that ''Tyrannosaurus'' and the dubious genus ''Nanotyrannus'' are synonymous, due to analysis of the growth rings in the bones of the two specimens studied.

Over half of the known ''T. rex'' specimens appear to have died within six years of reaching sexual maturity, a pattern which is also seen in other tyrannosaurs and in some large, long-lived birds and mammals today. These species are characterized by high infant mortality rates, followed by relatively low mortality among juveniles. Mortality increases again following sexual maturity, partly due to the stresses of reproduction. One study suggests that the rarity of juvenile ''T. rex'' fossils is due in part to low juvenile mortality rates; the animals were not dying in large numbers at these ages, and thus were not often fossilized. This rarity may also be due to the incompleteness of the fossil record or to the bias of fossil collectors towards larger, more spectacular specimens. In a 2013 lecture, Thomas Holtz Jr. suggested that dinosaurs "lived fast and died young" because they reproduced quickly whereas mammals have long life spans because they take longer to reproduce. Gregory S. Paul also writes that ''Tyrannosaurus'' reproduced quickly and died young, but attributes their short life spans to the dangerous lives they lived.

A study by Hutchinson and colleagues in 2011 corroborated the previous estimation methods in general, but their estimation of peak growth rates is significantly higher; it found that the "maximum growth rates for T. rex during the exponential stage are 1790 kg/year". Although these results were much higher than previous estimations, the authors noted that these results significantly lowered the great difference between its actual growth rate and the one which would be expected of an animal of its size. The sudden change in growth rate at the end of the growth spurt may indicate physical maturity, a hypothesis which is supported by the discovery of medullary tissue in the femur of a 16 to 20-year-old ''T. rex'' from Montana (Museum of the Rockies, MOR 1125, also known as B-rex). Medullary tissue is found only in female birds during ovulation, indicating that B-rex was of reproductive age. Further study indicates an age of 18 for this specimen. In 2016, it was finally confirmed by Mary Higby Schweitzer and Lindsay Zanno and colleagues that the soft tissue within the femur of MOR 1125 was medullary tissue. This also confirmed the identity of the specimen as a female. The discovery of medullary bone tissue within ''Tyrannosaurus'' may prove valuable in determining the sex of other dinosaur species in future examinations, as the chemical makeup of medullary tissue is unmistakable. Other tyrannosaurids exhibit extremely similar growth curves, although with lower growth rates corresponding to their lower adult sizes.

An additional study published in 2020 by Woodward and colleagues, for the journal ''Science Advances'' indicates that during their growth from juvenile to adult, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was capable of slowing down its growth to counter environmental factors such as lack of food. The study, focusing on two juvenile specimens between 13 and 15 years old housed at the Burpee Museum in Illinois, indicates that the rate of maturation for ''Tyrannosaurus'' was dependent on resource abundance. This study also indicates that in such changing environments, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was particularly well-suited to an environment that shifted yearly in regards to resource abundance, hinting that other midsize predators might have had difficulty surviving in such harsh conditions and explaining the niche partitioning between juvenile and adult tyrannosaurs. The study further indicates that ''Tyrannosaurus'' and the dubious genus ''Nanotyrannus'' are synonymous, due to analysis of the growth rings in the bones of the two specimens studied.

Over half of the known ''T. rex'' specimens appear to have died within six years of reaching sexual maturity, a pattern which is also seen in other tyrannosaurs and in some large, long-lived birds and mammals today. These species are characterized by high infant mortality rates, followed by relatively low mortality among juveniles. Mortality increases again following sexual maturity, partly due to the stresses of reproduction. One study suggests that the rarity of juvenile ''T. rex'' fossils is due in part to low juvenile mortality rates; the animals were not dying in large numbers at these ages, and thus were not often fossilized. This rarity may also be due to the incompleteness of the fossil record or to the bias of fossil collectors towards larger, more spectacular specimens. In a 2013 lecture, Thomas Holtz Jr. suggested that dinosaurs "lived fast and died young" because they reproduced quickly whereas mammals have long life spans because they take longer to reproduce. Gregory S. Paul also writes that ''Tyrannosaurus'' reproduced quickly and died young, but attributes their short life spans to the dangerous lives they lived.

The discovery of feathered dinosaurs led to debate regarding whether, and to what extent, ''Tyrannosaurus'' might have been feathered. Filamentous structures, which are commonly recognized as the precursors of feathers, have been reported in the small-bodied, basal tyrannosauroid ''Dilong paradoxus'' from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China in 2004. Because integumentary impressions of larger tyrannosauroids known at that time showed evidence of scale (anatomy), scales, the researchers who studied ''Dilong'' speculated that insulating feathers might have been lost by larger species due to their smaller surface-to-volume ratio. The subsequent discovery of the giant species ''Yutyrannus huali'', also from the Yixian, showed that even some large tyrannosauroids had feathers covering much of their bodies, casting doubt on the hypothesis that they were a size-related feature. A 2017 study reviewed known skin impressions of tyrannosaurids, including those of a ''Tyrannosaurus'' specimen nicknamed "Wyrex" (BHI 6230) which preserves patches of mosaic scales on the tail, hip, and neck. The study concluded that feather covering of large tyrannosaurids such as ''Tyrannosaurus'' was, if present, limited to the upper side of the trunk.

A conference abstract published in 2016 posited that theropods such as ''Tyrannosaurus'' had their upper teeth covered in lips, instead of bare teeth as seen in crocodilians. This was based on the presence of Tooth enamel, enamel, which according to the study needs to remain hydrated, an issue not faced by aquatic animals like crocodilians. A 2017 analytical study proposed that tyrannosaurids had large, flat scales on their snouts instead of lips. However, there has been criticism where it favors the idea for lips. Crocodiles do not really have flat scales but rather cracked keratinized skin; by observing the hummocky rugosity of tyrannosaurids, and comparing it to extant lizards they found that tyrannosaurids had squamose scales rather than a crocodillian-like skin.

The discovery of feathered dinosaurs led to debate regarding whether, and to what extent, ''Tyrannosaurus'' might have been feathered. Filamentous structures, which are commonly recognized as the precursors of feathers, have been reported in the small-bodied, basal tyrannosauroid ''Dilong paradoxus'' from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China in 2004. Because integumentary impressions of larger tyrannosauroids known at that time showed evidence of scale (anatomy), scales, the researchers who studied ''Dilong'' speculated that insulating feathers might have been lost by larger species due to their smaller surface-to-volume ratio. The subsequent discovery of the giant species ''Yutyrannus huali'', also from the Yixian, showed that even some large tyrannosauroids had feathers covering much of their bodies, casting doubt on the hypothesis that they were a size-related feature. A 2017 study reviewed known skin impressions of tyrannosaurids, including those of a ''Tyrannosaurus'' specimen nicknamed "Wyrex" (BHI 6230) which preserves patches of mosaic scales on the tail, hip, and neck. The study concluded that feather covering of large tyrannosaurids such as ''Tyrannosaurus'' was, if present, limited to the upper side of the trunk.

A conference abstract published in 2016 posited that theropods such as ''Tyrannosaurus'' had their upper teeth covered in lips, instead of bare teeth as seen in crocodilians. This was based on the presence of Tooth enamel, enamel, which according to the study needs to remain hydrated, an issue not faced by aquatic animals like crocodilians. A 2017 analytical study proposed that tyrannosaurids had large, flat scales on their snouts instead of lips. However, there has been criticism where it favors the idea for lips. Crocodiles do not really have flat scales but rather cracked keratinized skin; by observing the hummocky rugosity of tyrannosaurids, and comparing it to extant lizards they found that tyrannosaurids had squamose scales rather than a crocodillian-like skin.

As the number of known specimens increased, scientists began to analyze the variation between individuals and discovered what appeared to be two distinct body types, or ''morphs'', similar to some other theropod species. As one of these morphs was more solidly built, it was termed the 'robust' morph while the other was termed 'Wikt:gracile, gracile'. Several morphology (biology), morphological differences associated with the two morphs were used to analyze sexual dimorphism in ''T. rex'', with the 'robust' morph usually suggested to be female. For example, the pelvis of several 'robust' specimens seemed to be wider, perhaps to allow the passage of Egg (biology), eggs. It was also thought that the 'robust' morphology correlated with a reduced chevron (anatomy), chevron on the first tail vertebra, also ostensibly to allow eggs to pass out of the reproductive system, reproductive tract, as had been erroneously reported for crocodiles.

In recent years, evidence for sexual dimorphism has been weakened. A 2005 study reported that previous claims of sexual dimorphism in crocodile chevron anatomy were in error, casting doubt on the existence of similar dimorphism between ''T. rex'' sexes. A full-sized chevron was discovered on the first tail vertebra of Sue, an extremely robust individual, indicating that this feature could not be used to differentiate the two morphs anyway. As ''T. rex'' specimens have been found from Saskatchewan to New Mexico, differences between individuals may be indicative of geographic variation rather than sexual dimorphism. The differences could also be age-related, with 'robust' individuals being older animals.

Only a single ''Tyrannosaurus'' specimen has been conclusively shown to belong to a specific sex. Examination of B-rex demonstrated the preservation of soft tissue within several bones. Some of this tissue has been identified as a medullary tissue, a specialized tissue grown only in modern birds as a source of calcium for the production of eggshell during ovulation. As only female birds lay eggs, medullary tissue is only found naturally in females, although males are capable of producing it when injected with female reproductive hormones like estrogen. This strongly suggests that B-rex was female and that she died during ovulation. Recent research has shown that medullary tissue is never found in crocodiles, which are thought to be the closest living relatives of dinosaurs, aside from birds. The shared presence of medullary tissue in birds and theropod dinosaurs is further evidence of the close evolutionary relationship between the two.

As the number of known specimens increased, scientists began to analyze the variation between individuals and discovered what appeared to be two distinct body types, or ''morphs'', similar to some other theropod species. As one of these morphs was more solidly built, it was termed the 'robust' morph while the other was termed 'Wikt:gracile, gracile'. Several morphology (biology), morphological differences associated with the two morphs were used to analyze sexual dimorphism in ''T. rex'', with the 'robust' morph usually suggested to be female. For example, the pelvis of several 'robust' specimens seemed to be wider, perhaps to allow the passage of Egg (biology), eggs. It was also thought that the 'robust' morphology correlated with a reduced chevron (anatomy), chevron on the first tail vertebra, also ostensibly to allow eggs to pass out of the reproductive system, reproductive tract, as had been erroneously reported for crocodiles.

In recent years, evidence for sexual dimorphism has been weakened. A 2005 study reported that previous claims of sexual dimorphism in crocodile chevron anatomy were in error, casting doubt on the existence of similar dimorphism between ''T. rex'' sexes. A full-sized chevron was discovered on the first tail vertebra of Sue, an extremely robust individual, indicating that this feature could not be used to differentiate the two morphs anyway. As ''T. rex'' specimens have been found from Saskatchewan to New Mexico, differences between individuals may be indicative of geographic variation rather than sexual dimorphism. The differences could also be age-related, with 'robust' individuals being older animals.

Only a single ''Tyrannosaurus'' specimen has been conclusively shown to belong to a specific sex. Examination of B-rex demonstrated the preservation of soft tissue within several bones. Some of this tissue has been identified as a medullary tissue, a specialized tissue grown only in modern birds as a source of calcium for the production of eggshell during ovulation. As only female birds lay eggs, medullary tissue is only found naturally in females, although males are capable of producing it when injected with female reproductive hormones like estrogen. This strongly suggests that B-rex was female and that she died during ovulation. Recent research has shown that medullary tissue is never found in crocodiles, which are thought to be the closest living relatives of dinosaurs, aside from birds. The shared presence of medullary tissue in birds and theropod dinosaurs is further evidence of the close evolutionary relationship between the two.

Like many bipedal dinosaurs, ''T. rex'' was historically depicted as a 'living tripod', with the body at 45 degrees or less from the vertical and the tail dragging along the ground, similar to a kangaroo. This concept dates from Joseph Leidy's 1865 reconstruction of ''Hadrosaurus'', the first to depict a dinosaur in a bipedal posture. In 1915, convinced that the creature stood upright, Henry Fairfield Osborn, former president of the American Museum of Natural History, further reinforced the notion in unveiling the first complete ''T. rex'' skeleton arranged this way. It stood in an upright pose for 77 years, until it was dismantled in 1992.

By 1970, scientists realized this pose was incorrect and could not have been maintained by a living animal, as it would have resulted in the Dislocation (medicine), dislocation or weakening of several joints, including the hips and the articulation between the head and the spinal column. The inaccurate AMNH mount inspired similar depictions in many films and paintings (such as Rudolph F. Zallinger, Rudolph Zallinger's famous mural ''The Age of Reptiles'' in Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History) until the 1990s, when films such as ''Jurassic Park (film), Jurassic Park'' introduced a more accurate posture to the general public. Modern representations in museums, art, and film show ''T. rex'' with its body approximately parallel to the ground with the tail extended behind the body to balance the head.

To sit down, ''Tyrannosaurus'' may have settled its weight backwards and rested its weight on a pubic boot, the wide expansion at the end of the pubis in some dinosaurs. With its weight rested on the pelvis, it may have been free to move the hindlimbs. Getting back up again might have involved some stabilization from the diminutive forelimbs. The latter known as Newman's pushup theory has been debated. Nonetheless, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was probably able to get up if it fell, which only would have required placing the limbs below the center of gravity, with the tail as an effective counterbalance. Healed stress fractures in the forelimbs have been put forward both as evidence that the arms cannot have been very useful and as evidence that they were indeed used and acquired wounds,Stevens K.A., Larson P, Willis E.D. & Anderson A. "Rex, sit: digital modeling of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' at rest". In Larson P & Carpenter K (eds.). ''Tyrannosaurus rex, the tyrant king'' (Indiana University Press, 2008). p. 192-203 like the rest of the body.

Like many bipedal dinosaurs, ''T. rex'' was historically depicted as a 'living tripod', with the body at 45 degrees or less from the vertical and the tail dragging along the ground, similar to a kangaroo. This concept dates from Joseph Leidy's 1865 reconstruction of ''Hadrosaurus'', the first to depict a dinosaur in a bipedal posture. In 1915, convinced that the creature stood upright, Henry Fairfield Osborn, former president of the American Museum of Natural History, further reinforced the notion in unveiling the first complete ''T. rex'' skeleton arranged this way. It stood in an upright pose for 77 years, until it was dismantled in 1992.

By 1970, scientists realized this pose was incorrect and could not have been maintained by a living animal, as it would have resulted in the Dislocation (medicine), dislocation or weakening of several joints, including the hips and the articulation between the head and the spinal column. The inaccurate AMNH mount inspired similar depictions in many films and paintings (such as Rudolph F. Zallinger, Rudolph Zallinger's famous mural ''The Age of Reptiles'' in Yale University's Peabody Museum of Natural History) until the 1990s, when films such as ''Jurassic Park (film), Jurassic Park'' introduced a more accurate posture to the general public. Modern representations in museums, art, and film show ''T. rex'' with its body approximately parallel to the ground with the tail extended behind the body to balance the head.

To sit down, ''Tyrannosaurus'' may have settled its weight backwards and rested its weight on a pubic boot, the wide expansion at the end of the pubis in some dinosaurs. With its weight rested on the pelvis, it may have been free to move the hindlimbs. Getting back up again might have involved some stabilization from the diminutive forelimbs. The latter known as Newman's pushup theory has been debated. Nonetheless, ''Tyrannosaurus'' was probably able to get up if it fell, which only would have required placing the limbs below the center of gravity, with the tail as an effective counterbalance. Healed stress fractures in the forelimbs have been put forward both as evidence that the arms cannot have been very useful and as evidence that they were indeed used and acquired wounds,Stevens K.A., Larson P, Willis E.D. & Anderson A. "Rex, sit: digital modeling of ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' at rest". In Larson P & Carpenter K (eds.). ''Tyrannosaurus rex, the tyrant king'' (Indiana University Press, 2008). p. 192-203 like the rest of the body.

When ''T. rex'' was first discovered, the humerus was the only element of the forelimb known. Retrieved October 6, 2008. For the initial mounted skeleton as seen by the public in 1915, Osborn substituted longer, three-fingered forelimbs like those of ''Allosaurus''. A year earlier, Lawrence Lambe described the short, two-fingered forelimbs of the closely related ''Gorgosaurus''. This strongly suggested that ''T. rex'' had similar forelimbs, but this hypothesis was not confirmed until the first complete ''T. rex'' forelimbs were identified in 1989, belonging to MOR 555 (the "Wankel rex"). The remains of Sue also include complete forelimbs. ''T. rex'' arms are very small relative to overall body size, measuring only long, and some scholars have labelled them as vestigial organs, vestigial. However, the bones show large areas for muscle attachment, indicating considerable strength. This was recognized as early as 1906 by Osborn, who speculated that the forelimbs may have been used to grasp a mate during copulation (zoology), copulation. Newman (1970) suggested that the forelimbs were used to assist ''Tyrannosaurus'' in rising from a prone position. Since then, other functions have been proposed, although some scholars find them implausible. Padian (2022) argued that the reduction of the arms in tyrannosaurids did not serve a particular function but was a secondary adaptation; stating that as tyrannosaurids developed larger and more powerful skulls and jaws, the arms got smaller to avoid being bitten or torn by other individuals, particularly during group feedings.Padian K (2022)

When ''T. rex'' was first discovered, the humerus was the only element of the forelimb known. Retrieved October 6, 2008. For the initial mounted skeleton as seen by the public in 1915, Osborn substituted longer, three-fingered forelimbs like those of ''Allosaurus''. A year earlier, Lawrence Lambe described the short, two-fingered forelimbs of the closely related ''Gorgosaurus''. This strongly suggested that ''T. rex'' had similar forelimbs, but this hypothesis was not confirmed until the first complete ''T. rex'' forelimbs were identified in 1989, belonging to MOR 555 (the "Wankel rex"). The remains of Sue also include complete forelimbs. ''T. rex'' arms are very small relative to overall body size, measuring only long, and some scholars have labelled them as vestigial organs, vestigial. However, the bones show large areas for muscle attachment, indicating considerable strength. This was recognized as early as 1906 by Osborn, who speculated that the forelimbs may have been used to grasp a mate during copulation (zoology), copulation. Newman (1970) suggested that the forelimbs were used to assist ''Tyrannosaurus'' in rising from a prone position. Since then, other functions have been proposed, although some scholars find them implausible. Padian (2022) argued that the reduction of the arms in tyrannosaurids did not serve a particular function but was a secondary adaptation; stating that as tyrannosaurids developed larger and more powerful skulls and jaws, the arms got smaller to avoid being bitten or torn by other individuals, particularly during group feedings.Padian K (2022)

"Why tyrannosaurid forelimbs were so short: An integrative hypothesis"

''Acta Palaeontologica Polonica'' 67(1): p. 63-76 Another possibility is that the forelimbs held struggling prey while it was killed by the tyrannosaur's enormous jaws. This hypothesis may be supported by biomechanics, biomechanical analysis. ''T. rex'' forelimb bones exhibit extremely thick Bone#Structure, cortical bone, which has been interpreted as evidence that they were developed to withstand heavy loads. The biceps brachii muscle of an adult ''T. rex'' was capable of lifting by itself; other muscles such as the brachialis would work along with the biceps to make elbow flexion even more powerful. The M. biceps muscle of ''T. rex'' was 3.5 times as powerful as the human equivalent. A ''T. rex'' forearm had a limited range of motion, with the shoulder and elbow joints allowing only 40 and 45 degrees of motion, respectively. In contrast, the same two joints in ''Deinonychus'' allow up to 88 and 130 degrees of motion, respectively, while a human arm can rotate 360 degrees at the shoulder and move through 165 degrees at the elbow. The heavy build of the arm bones, strength of the muscles, and limited range of motion may indicate a system evolved to hold fast despite the stresses of a struggling prey animal. In the first detailed scientific description of ''Tyrannosaurus'' forelimbs, paleontologists Kenneth Carpenter and Matt Smith dismissed notions that the forelimbs were useless or that ''Tyrannosaurus'' was an obligate scavenger.