Trireme 1.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

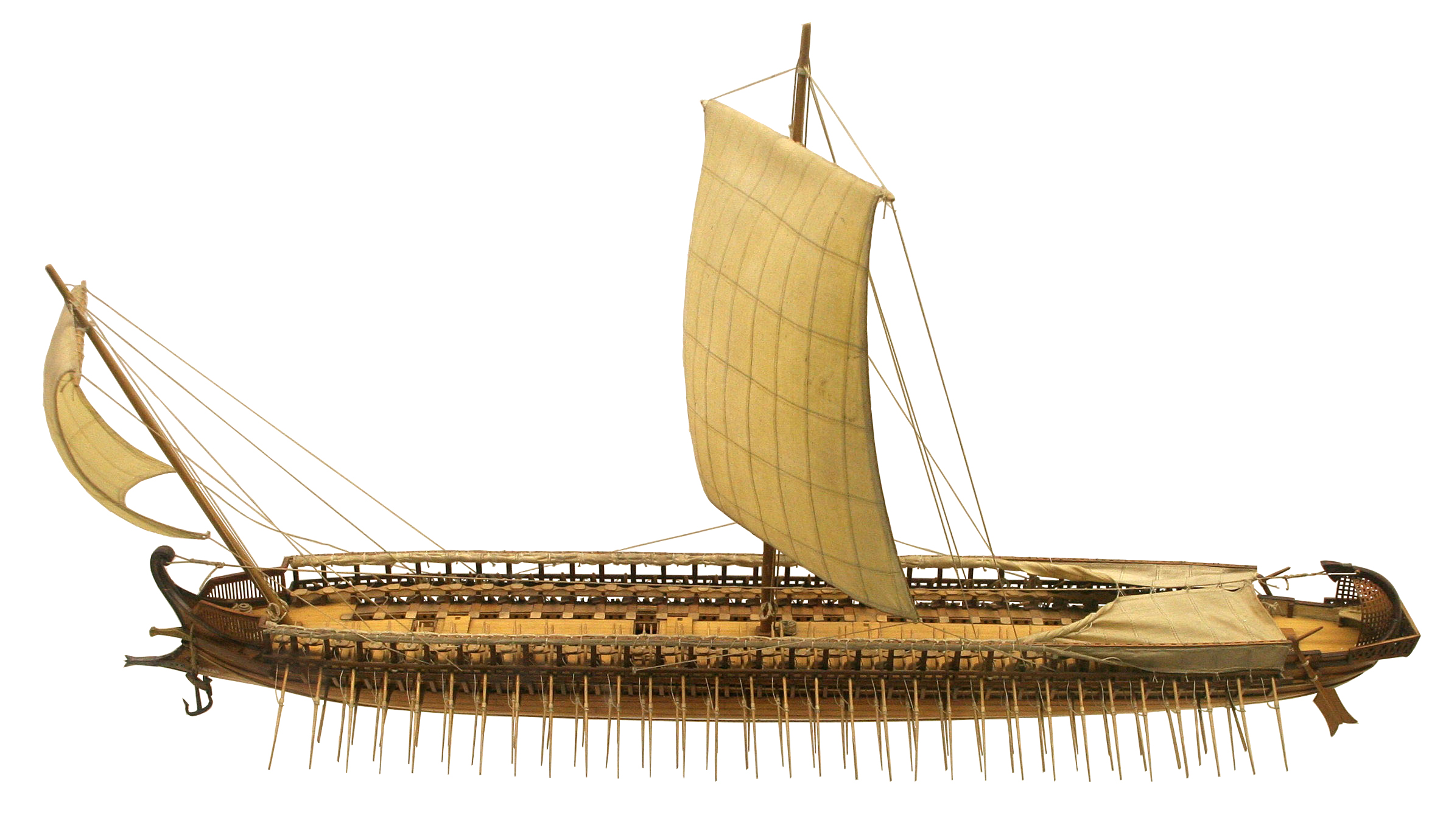

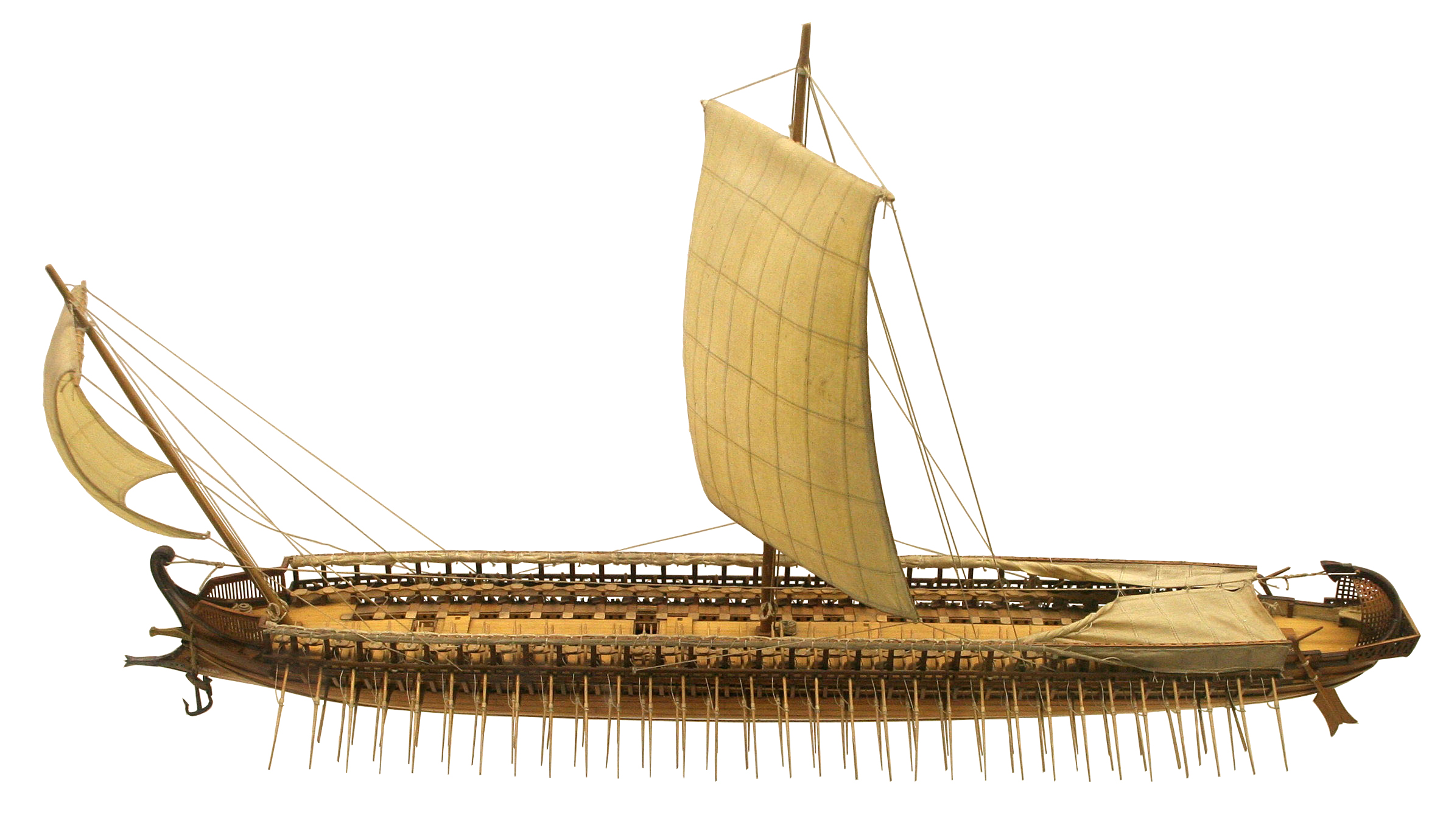

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the

Depictions of two-banked ships (

Depictions of two-banked ships (

Athens was at that time embroiled in a conflict with the neighbouring island of

Athens was at that time embroiled in a conflict with the neighbouring island of

Based on all archeological evidence, the design of the trireme most likely pushed the technological limits of the ancient world. After gathering the proper timbers and materials it was time to consider the fundamentals of the trireme design. These fundamentals included accommodations, propulsion, weight and waterline, centre of gravity and stability, strength, and feasibility. All of these variables are dependent on one another; however a certain area may be more important than another depending on the purpose of the ship.

The arrangement and number of oarsmen is the first deciding factor in the size of the ship. For a ship to travel at high speeds would require a high oar-gearing, which is the ratio between the outboard length of an oar and the inboard length; it is this arrangement of the oars which is unique and highly effective for the trireme. The ports would house the oarsmen with a minimal waste of space. There would be three files of oarsmen on each side tightly but workably packed by placing each man outboard of, and in height overlapping, the one below, provided that thalamian tholes were set inboard and their ports enlarged to allow oar movement.

Thalamian, zygian, and thranite are the English terms for ''thalamios'' (θαλάμιος), ''zygios'' (ζύγιος), and ''thranites'' (θρανίτης), the Greek words for the oarsmen in, respectively the lowest, middle, and uppermost files of the triereis.

Tholes were pins that acted as fulcrums to the oars that allowed them to move. The center of gravity of the ship is low because of the overlapping formation of the files that allow the ports to remain closer to the ships walls. A lower center of gravity would provide adequate stability.

The trireme was constructed to maximize all traits of the ship to the point where if any changes were made the design would be compromised. Speed was maximized to the point where any less weight would have resulted in considerable losses to the ship's integrity. The center of gravity was placed at the lowest possible position where the Thalamian tholes were just above the waterline which retained the ship's resistance to waves and the possible rollover. If the center of gravity were placed any higher, the additional beams needed to restore stability would have resulted in the exclusion of the Thalamian tholes due to the reduced hull space. The purpose of the area just below the center of gravity and the waterline known as the ''hypozomata'' (ὑποζώματα) was to allow bending of the hull when faced with up to 90 kN of force. The calculations of forces that could have been absorbed by the ship are arguable because there is not enough evidence to confirm the exact process of jointing used in ancient times. In a modern reconstruction of the ship, a polysulphide sealant was used to compare to the caulking that evidence suggests was used; however this is also contentious because there is simply not enough evidence to authentically reproduce the triereis seams.

Triremes required a great deal of upkeep in order to stay afloat, as references to the replacement of ropes, sails, rudders, oars and masts in the middle of campaigns suggest.Hanson (2006), p. 260Fields (2007), p. 10 They also would become waterlogged if left in the sea for too long. In order to prevent this from happening, ships would have to be pulled from the water during the night. The use of lightwoods meant that the ship could be carried ashore by as few as 140 men.'' IG'' I.153 Beaching the ships at night, however, would leave the troops vulnerable to surprise attacks. While well-maintained triremes would last up to 25 years, during the Peloponnesian War, Athens had to build nearly 20 triremes a year to maintain their fleet of 300.

The Athenian trireme had two great cables of about 47 mm in diameter and twice the ship's length called ''hypozomata'' (undergirding), and carried two spares. They were possibly rigged fore and aft from end to end along the middle line of the hull just under the main beams and tensioned to 13.5 tonnes force. The ''hypozomata'' were considered important and secret: their export from Athens was a capital offense. This cable would act as a stretched tendon straight down the middle of the hull, and would have prevented hogging. Additionally, hull plank butts would remain in compression in all but the most severe sea conditions, reducing working of joints and consequent leakage. The ''hypozomata'' would also have significantly braced the structure of the trireme against the stresses of ramming, giving it an important advantage in combat. According to material scientist

Based on all archeological evidence, the design of the trireme most likely pushed the technological limits of the ancient world. After gathering the proper timbers and materials it was time to consider the fundamentals of the trireme design. These fundamentals included accommodations, propulsion, weight and waterline, centre of gravity and stability, strength, and feasibility. All of these variables are dependent on one another; however a certain area may be more important than another depending on the purpose of the ship.

The arrangement and number of oarsmen is the first deciding factor in the size of the ship. For a ship to travel at high speeds would require a high oar-gearing, which is the ratio between the outboard length of an oar and the inboard length; it is this arrangement of the oars which is unique and highly effective for the trireme. The ports would house the oarsmen with a minimal waste of space. There would be three files of oarsmen on each side tightly but workably packed by placing each man outboard of, and in height overlapping, the one below, provided that thalamian tholes were set inboard and their ports enlarged to allow oar movement.

Thalamian, zygian, and thranite are the English terms for ''thalamios'' (θαλάμιος), ''zygios'' (ζύγιος), and ''thranites'' (θρανίτης), the Greek words for the oarsmen in, respectively the lowest, middle, and uppermost files of the triereis.

Tholes were pins that acted as fulcrums to the oars that allowed them to move. The center of gravity of the ship is low because of the overlapping formation of the files that allow the ports to remain closer to the ships walls. A lower center of gravity would provide adequate stability.

The trireme was constructed to maximize all traits of the ship to the point where if any changes were made the design would be compromised. Speed was maximized to the point where any less weight would have resulted in considerable losses to the ship's integrity. The center of gravity was placed at the lowest possible position where the Thalamian tholes were just above the waterline which retained the ship's resistance to waves and the possible rollover. If the center of gravity were placed any higher, the additional beams needed to restore stability would have resulted in the exclusion of the Thalamian tholes due to the reduced hull space. The purpose of the area just below the center of gravity and the waterline known as the ''hypozomata'' (ὑποζώματα) was to allow bending of the hull when faced with up to 90 kN of force. The calculations of forces that could have been absorbed by the ship are arguable because there is not enough evidence to confirm the exact process of jointing used in ancient times. In a modern reconstruction of the ship, a polysulphide sealant was used to compare to the caulking that evidence suggests was used; however this is also contentious because there is simply not enough evidence to authentically reproduce the triereis seams.

Triremes required a great deal of upkeep in order to stay afloat, as references to the replacement of ropes, sails, rudders, oars and masts in the middle of campaigns suggest.Hanson (2006), p. 260Fields (2007), p. 10 They also would become waterlogged if left in the sea for too long. In order to prevent this from happening, ships would have to be pulled from the water during the night. The use of lightwoods meant that the ship could be carried ashore by as few as 140 men.'' IG'' I.153 Beaching the ships at night, however, would leave the troops vulnerable to surprise attacks. While well-maintained triremes would last up to 25 years, during the Peloponnesian War, Athens had to build nearly 20 triremes a year to maintain their fleet of 300.

The Athenian trireme had two great cables of about 47 mm in diameter and twice the ship's length called ''hypozomata'' (undergirding), and carried two spares. They were possibly rigged fore and aft from end to end along the middle line of the hull just under the main beams and tensioned to 13.5 tonnes force. The ''hypozomata'' were considered important and secret: their export from Athens was a capital offense. This cable would act as a stretched tendon straight down the middle of the hull, and would have prevented hogging. Additionally, hull plank butts would remain in compression in all but the most severe sea conditions, reducing working of joints and consequent leakage. The ''hypozomata'' would also have significantly braced the structure of the trireme against the stresses of ramming, giving it an important advantage in combat. According to material scientist

Construction of the trireme differed from modern practice. The construction of a trireme was expensive and required around 6,000 man-days of labour to complete. The ancient Mediterranean practice was to build the outer hull first, and the ribs afterwards. To secure and add strength to the hull, cables (''hypozōmata'') were employed, fitted in the keel and stretched by means of windlasses. Hence the triremes were often called "girded" when in commission.

The materials from which the trireme was constructed were an important aspect of its design. The three principal timbers included fir, pine, and cedar. Primarily the choice in timber depended on where the construction took place. For example, in Syria and Phoenicia, triereis were made of cedar, because pine was not readily available. Pine is stronger and more resistant to decay, but it is heavy, unlike fir, which was used because it was lightweight. The frame and internal structure would consist of pine and fir for a compromise between durability and weight.

Another very strong type of timber is oak; this was primarily used for the hulls of triereis, to withstand the force of hauling ashore. Other ships would usually have their hulls made of pine, because they would usually come ashore via a port or with the use of an anchor. It was necessary to ride the triereis onto the shores because there simply was no time to anchor a ship during war and gaining control of enemy shores was crucial in the advancement of an invading army. (Petersen) The joints of the ship required finding wood that was capable of absorbing water but was not completely dried out to the point where no water absorption could occur. There would be gaps between the planks of the hull when the ship was new, but, once submerged, the planks would absorb the water and expand, thus forming a watertight hull.

Problems would occur, for example, when shipbuilders would use green wood for the hull; when green timber is allowed to dry, it loses moisture, which causes cracks in the wood that could cause catastrophic damage to the ship. The sailyards and masts were preferably made from fir, because fir trees were naturally tall, and provided these parts in usually a single piece. Making durable rope consisted of using both papyrus and white flax; the idea to use such materials is suggested by evidence to have originated in Egypt. In addition, ropes began being made from a variety of

Construction of the trireme differed from modern practice. The construction of a trireme was expensive and required around 6,000 man-days of labour to complete. The ancient Mediterranean practice was to build the outer hull first, and the ribs afterwards. To secure and add strength to the hull, cables (''hypozōmata'') were employed, fitted in the keel and stretched by means of windlasses. Hence the triremes were often called "girded" when in commission.

The materials from which the trireme was constructed were an important aspect of its design. The three principal timbers included fir, pine, and cedar. Primarily the choice in timber depended on where the construction took place. For example, in Syria and Phoenicia, triereis were made of cedar, because pine was not readily available. Pine is stronger and more resistant to decay, but it is heavy, unlike fir, which was used because it was lightweight. The frame and internal structure would consist of pine and fir for a compromise between durability and weight.

Another very strong type of timber is oak; this was primarily used for the hulls of triereis, to withstand the force of hauling ashore. Other ships would usually have their hulls made of pine, because they would usually come ashore via a port or with the use of an anchor. It was necessary to ride the triereis onto the shores because there simply was no time to anchor a ship during war and gaining control of enemy shores was crucial in the advancement of an invading army. (Petersen) The joints of the ship required finding wood that was capable of absorbing water but was not completely dried out to the point where no water absorption could occur. There would be gaps between the planks of the hull when the ship was new, but, once submerged, the planks would absorb the water and expand, thus forming a watertight hull.

Problems would occur, for example, when shipbuilders would use green wood for the hull; when green timber is allowed to dry, it loses moisture, which causes cracks in the wood that could cause catastrophic damage to the ship. The sailyards and masts were preferably made from fir, because fir trees were naturally tall, and provided these parts in usually a single piece. Making durable rope consisted of using both papyrus and white flax; the idea to use such materials is suggested by evidence to have originated in Egypt. In addition, ropes began being made from a variety of  Once the triremes were seaworthy, it is argued that they were highly decorated with, "eyes, nameplates, painted figureheads, and various ornaments". These decorations were used both to show the wealth of the patrician and to make the ship frightening to the enemy. The home port of each trireme was signaled by the wooden statue of a deity located above the bronze ram on the front of the ship.Hanson (2006), p. 239 In the case of Athens, since most of the fleet's triremes were paid for by wealthy citizens, there was a natural sense of competition among the patricians to create the "most impressive" trireme, both to intimidate the enemy and to attract the best oarsmen. Of all military expenditure, triremes were the most labor- and (in terms of men and money) investment-intensive.

Once the triremes were seaworthy, it is argued that they were highly decorated with, "eyes, nameplates, painted figureheads, and various ornaments". These decorations were used both to show the wealth of the patrician and to make the ship frightening to the enemy. The home port of each trireme was signaled by the wooden statue of a deity located above the bronze ram on the front of the ship.Hanson (2006), p. 239 In the case of Athens, since most of the fleet's triremes were paid for by wealthy citizens, there was a natural sense of competition among the patricians to create the "most impressive" trireme, both to intimidate the enemy and to attract the best oarsmen. Of all military expenditure, triremes were the most labor- and (in terms of men and money) investment-intensive.

In the ancient navies, crews were composed not of

In the ancient navies, crews were composed not of

Squadrons of triremes employed a variety of tactics. The ''periplous'' ( Gk., "sailing around") involved outflanking or encircling the enemy so as to attack them in the vulnerable rear; the ''diekplous'' (Gk., "Sailing out through") involved a concentrated charge so as to break a hole in the enemy line, allowing galleys to break through and then wheel to attack the enemy line from behind; and the ''kyklos'' (Gk., "circle") and the ''mēnoeidēs kyklos'' (Gk. "half-circle"; literally, "moon-shaped (i.e. crescent-shaped) circle"), were defensive tactics to be employed against these manoeuvres. In all of these manoeuvres, the ability to accelerate faster, row faster, and turn more sharply than one's enemy was very important.

Athens' strength in the Peloponnesian War came from its navy, whereas Sparta's came from its land-based Hoplite army. As the war progressed however the Spartans came to realize that if they were to undermine

Squadrons of triremes employed a variety of tactics. The ''periplous'' ( Gk., "sailing around") involved outflanking or encircling the enemy so as to attack them in the vulnerable rear; the ''diekplous'' (Gk., "Sailing out through") involved a concentrated charge so as to break a hole in the enemy line, allowing galleys to break through and then wheel to attack the enemy line from behind; and the ''kyklos'' (Gk., "circle") and the ''mēnoeidēs kyklos'' (Gk. "half-circle"; literally, "moon-shaped (i.e. crescent-shaped) circle"), were defensive tactics to be employed against these manoeuvres. In all of these manoeuvres, the ability to accelerate faster, row faster, and turn more sharply than one's enemy was very important.

Athens' strength in the Peloponnesian War came from its navy, whereas Sparta's came from its land-based Hoplite army. As the war progressed however the Spartans came to realize that if they were to undermine

During the

During the

''A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890)'', entry on "Warships"

Hellenic Navy web page for the reconstructed ''Olympias'' trireme

from the Centre for Maritime Archaeology of the

Merchant ships page

The Trireme Trust

{{Authority control Ancient ships Galleys Ships of ancient Greece Naval history of ancient Greece Navy of ancient Athens Navy of ancient Rome Naval warfare of antiquity Achaemenid navy Transport in Phoenicia

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, especially the Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

, ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

and Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

.

The trireme derives its name from its three rows of oar

An oar is an implement used for water-borne propulsion. Oars have a flat blade at one end. Rowers grasp the oar at the other end.

The difference between oars and paddles is that oars are used exclusively for rowing. In rowing the oar is connecte ...

s, manned with one man per oar. The early trireme was a development of the penteconter

The penteconter (alt. spelling pentekonter, pentaconter, pentecontor or pentekontor; el, πεντηκόντερος, ''pentēkónteros'', "fifty-oared"), plural penteconters, was an ancient Greek galley in use since the archaic period.

In an ...

, an ancient warship with a single row of 25 oars on each side (i.e., a single-banked boat), and of the bireme

A bireme (, ) is an ancient oared warship (galley) with two superimposed rows of oars on each side. Biremes were long vessels built for military purposes and could achieve relatively high speed. They were invented well before the 6th century BC a ...

( grc, διήρης, ''diērēs''), a warship with two banks of oars, of Phoenician origin. The word dieres does not appear until the Roman period. According to Morrison and Williams, "It must be assumed the term pentekontor covered the two-level type". As a ship, it was fast and agile and was the dominant warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster ...

in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

from the 7th to the 4th centuries BC, when it was largely superseded by the larger quadrireme

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the Mediterranean Sea, superseding the trireme and transforming naval warfare. Ships became increasingly large and heavy, including some of the largest wooden ships hitherto con ...

s and quinqueremes. Triremes played a vital role in the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

, the creation of the Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

maritime empire and its downfall during the Peloponnesian War.

Medieval and early modern galleys with three files of oarsmen per side are sometimes referred to as triremes.

History

Origins

Depictions of two-banked ships (

Depictions of two-banked ships (bireme

A bireme (, ) is an ancient oared warship (galley) with two superimposed rows of oars on each side. Biremes were long vessels built for military purposes and could achieve relatively high speed. They were invented well before the 6th century BC a ...

s), with or without the ''parexeiresia'' (the outriggers

An outrigger is a projecting structure on a boat, with specific meaning depending on types of vessel. Outriggers may also refer to legs on a wheeled vehicle that are folded out when it needs stabilization, for example on a crane that lifts ...

, see below), are common in 8th century BC and later vases and pottery fragments, and it is at the end of that century that the first references to three-banked ships are found. Fragments from an 8th-century relief at the Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

n capital of Nineveh depicting the fleets of Tyre and Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

show ships with rams

In engineering, RAMS (reliability, availability, maintainability and safety)Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

or Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

, and the exact time it developed into the foremost ancient fighting ship. Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen an ...

in the 2nd century, drawing on earlier works, explicitly attributes the invention of the trireme (''trikrotos naus'', "three-banked ship") to the Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

ians. According to Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, the trireme was introduced to Greece by the Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians ( grc, Α΄ ᾽Επιστολὴ πρὸς Κορινθίους) is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-aut ...

in the late 8th century BC, and the Corinthian Ameinocles built four such ships for the Samians

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

. This was interpreted by later writers, Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

and Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, to mean that triremes were ''invented'' in Corinth, the possibility remains that the earliest three-banked warships originated in Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

.

Early use and development

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

mentions that the Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

pharaoh Necho II

Necho II (sometimes Nekau, Neku, Nechoh, or Nikuu; Greek: Νεκώς Β'; ) of Egypt was a king of the 26th Dynasty (610–595 BC), which ruled from Sais. Necho undertook a number of construction projects across his kingdom. In his reign, accordi ...

(610–595 BC) built triremes on the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

, for service in the Mediterranean, and in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

, but this reference is disputed by modern historians, and attributed to a confusion, since "triērēs" was by the 5th century used in the generic sense of "warship", regardless its type. The first definite reference to the use of triremes in naval combat dates to ca. 525 BC, when, according to Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

, the tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to re ...

Polycrates

Polycrates (; grc-gre, Πολυκράτης), son of Aeaces, was the tyrant of Samos from the 540s BC to 522 BC. He had a reputation as both a fierce warrior and an enlightened tyrant.

Sources

The main source for Polycrates' life and activit ...

of Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greece, Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a se ...

was able to contribute 40 triremes to a Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

invasion of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

(Battle of Pelusium

The Battle of Pelusium was the first major battle between the Achaemenid Empire and Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, Egypt. This decisive battle transferred the throne of the Pharaohs to Cambyses II of Persia, marking the beginning of the Achaemenid ...

). Thucydides meanwhile clearly states that in the time of the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

, the majority of the Greek navies consisted of (probably two-tiered) penteconters and ''ploia makrá'' ("long ships").

In any case, by the early 5th century, the trireme was becoming the dominant warship type of the eastern Mediterranean, with minor differences between the "Greek" and "Phoenician" types, as literary references and depictions of the ships on coins make clear. The first large-scale naval battle where triremes participated was the Battle of Lade

The Battle of Lade ( grc, Ναυμαχία τῆς Λάδης, translit=Naumachia tēs Ladēs) was a naval battle which occurred during the Ionian Revolt, in 494 BC. It was fought between an alliance of the Ionian cities (joined by the Lesbi ...

during the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisf ...

, where the combined fleets of the Greek Ionian cities were defeated by the Persian fleet, composed of squadrons from their Phoenician, Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined ...

n, and Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

subjects.

The Persian Wars

Athens was at that time embroiled in a conflict with the neighbouring island of

Athens was at that time embroiled in a conflict with the neighbouring island of Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and ...

, which possessed a formidable navy. In order to counter this, and possibly with an eye already at the mounting Persian preparations, in 483/2 BC the Athenian statesman Themistocles

Themistocles (; grc-gre, Θεμιστοκλῆς; c. 524–459 BC) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As ...

used his political skills and influence to persuade the Athenian assembly

The ecclesia or ekklesia ( el, ) was the assembly of the citizens in city-states of ancient Greece.

The ekklesia of Athens

The ekklesia of ancient Athens is particularly well-known. It was the popular assembly, open to all male citizens as so ...

to start the construction of 200 triremes, using the income of the newly discovered silver mines at Laurion

Laurium or Lavrio ( ell, Λαύριο; grc, Λαύρειον (later ); before early 11th century BC: Θορικός ''Thorikos''; from Middle Ages until 1908: Εργαστήρια ''Ergastiria'') is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Gree ...

. The first clash with the Persian navy was at the Battle of Artemisium

The Battle of Artemisium or Artemision was a series of naval engagements over three days during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle took place simultaneously with the land battle at Thermopylae, in August or September 480 BC, off t ...

, where both sides suffered great casualties. However, the decisive naval clash occurred at Salamis, where Xerxes' invasion fleet was decisively defeated.

After Salamis and another Greek victory over the Persian fleet at Mycale

Mycale (). also Mykale and Mykali ( grc, Μυκάλη, ''Mykálē''), called Samsun Dağı and Dilek Dağı (Dilek Peninsula) in modern Turkey, is a mountain on the west coast of central Anatolia in Turkey, north of the mouth of the Maeander an ...

, the Ionian cities were freed, and the Delian League was formed under the aegis of Athens. Gradually, the predominance of Athens turned the League effectively into an Athenian Empire. The source and foundation of Athens' power was her strong fleet, composed of over 200 triremes. It not only secured control of the Aegean Sea and the loyalty of her allies, but also safeguarded the trade routes and the grain shipments from the Black Sea, which fed the city's burgeoning population. In addition, as it provided permanent employment for the city's poorer citizens, the fleet played an important role in maintaining and promoting the radical Athenian form of democracy. Athenian maritime power is the first example of thalassocracy

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy sometimes also maritime empire, is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples ...

in world history. Aside from Athens, other major naval powers of the era included Syracuse, Corfu and Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

.

In the subsequent Peloponnesian War, naval battles fought by triremes were crucial in the power balance between Athens and Sparta. Despite numerous land engagements, Athens was finally defeated through the destruction of her fleet during the Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a devas ...

, and finally, at the Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since ...

, at the hands of Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

and her allies.

Design

Based on all archeological evidence, the design of the trireme most likely pushed the technological limits of the ancient world. After gathering the proper timbers and materials it was time to consider the fundamentals of the trireme design. These fundamentals included accommodations, propulsion, weight and waterline, centre of gravity and stability, strength, and feasibility. All of these variables are dependent on one another; however a certain area may be more important than another depending on the purpose of the ship.

The arrangement and number of oarsmen is the first deciding factor in the size of the ship. For a ship to travel at high speeds would require a high oar-gearing, which is the ratio between the outboard length of an oar and the inboard length; it is this arrangement of the oars which is unique and highly effective for the trireme. The ports would house the oarsmen with a minimal waste of space. There would be three files of oarsmen on each side tightly but workably packed by placing each man outboard of, and in height overlapping, the one below, provided that thalamian tholes were set inboard and their ports enlarged to allow oar movement.

Thalamian, zygian, and thranite are the English terms for ''thalamios'' (θαλάμιος), ''zygios'' (ζύγιος), and ''thranites'' (θρανίτης), the Greek words for the oarsmen in, respectively the lowest, middle, and uppermost files of the triereis.

Tholes were pins that acted as fulcrums to the oars that allowed them to move. The center of gravity of the ship is low because of the overlapping formation of the files that allow the ports to remain closer to the ships walls. A lower center of gravity would provide adequate stability.

The trireme was constructed to maximize all traits of the ship to the point where if any changes were made the design would be compromised. Speed was maximized to the point where any less weight would have resulted in considerable losses to the ship's integrity. The center of gravity was placed at the lowest possible position where the Thalamian tholes were just above the waterline which retained the ship's resistance to waves and the possible rollover. If the center of gravity were placed any higher, the additional beams needed to restore stability would have resulted in the exclusion of the Thalamian tholes due to the reduced hull space. The purpose of the area just below the center of gravity and the waterline known as the ''hypozomata'' (ὑποζώματα) was to allow bending of the hull when faced with up to 90 kN of force. The calculations of forces that could have been absorbed by the ship are arguable because there is not enough evidence to confirm the exact process of jointing used in ancient times. In a modern reconstruction of the ship, a polysulphide sealant was used to compare to the caulking that evidence suggests was used; however this is also contentious because there is simply not enough evidence to authentically reproduce the triereis seams.

Triremes required a great deal of upkeep in order to stay afloat, as references to the replacement of ropes, sails, rudders, oars and masts in the middle of campaigns suggest.Hanson (2006), p. 260Fields (2007), p. 10 They also would become waterlogged if left in the sea for too long. In order to prevent this from happening, ships would have to be pulled from the water during the night. The use of lightwoods meant that the ship could be carried ashore by as few as 140 men.'' IG'' I.153 Beaching the ships at night, however, would leave the troops vulnerable to surprise attacks. While well-maintained triremes would last up to 25 years, during the Peloponnesian War, Athens had to build nearly 20 triremes a year to maintain their fleet of 300.

The Athenian trireme had two great cables of about 47 mm in diameter and twice the ship's length called ''hypozomata'' (undergirding), and carried two spares. They were possibly rigged fore and aft from end to end along the middle line of the hull just under the main beams and tensioned to 13.5 tonnes force. The ''hypozomata'' were considered important and secret: their export from Athens was a capital offense. This cable would act as a stretched tendon straight down the middle of the hull, and would have prevented hogging. Additionally, hull plank butts would remain in compression in all but the most severe sea conditions, reducing working of joints and consequent leakage. The ''hypozomata'' would also have significantly braced the structure of the trireme against the stresses of ramming, giving it an important advantage in combat. According to material scientist

Based on all archeological evidence, the design of the trireme most likely pushed the technological limits of the ancient world. After gathering the proper timbers and materials it was time to consider the fundamentals of the trireme design. These fundamentals included accommodations, propulsion, weight and waterline, centre of gravity and stability, strength, and feasibility. All of these variables are dependent on one another; however a certain area may be more important than another depending on the purpose of the ship.

The arrangement and number of oarsmen is the first deciding factor in the size of the ship. For a ship to travel at high speeds would require a high oar-gearing, which is the ratio between the outboard length of an oar and the inboard length; it is this arrangement of the oars which is unique and highly effective for the trireme. The ports would house the oarsmen with a minimal waste of space. There would be three files of oarsmen on each side tightly but workably packed by placing each man outboard of, and in height overlapping, the one below, provided that thalamian tholes were set inboard and their ports enlarged to allow oar movement.

Thalamian, zygian, and thranite are the English terms for ''thalamios'' (θαλάμιος), ''zygios'' (ζύγιος), and ''thranites'' (θρανίτης), the Greek words for the oarsmen in, respectively the lowest, middle, and uppermost files of the triereis.

Tholes were pins that acted as fulcrums to the oars that allowed them to move. The center of gravity of the ship is low because of the overlapping formation of the files that allow the ports to remain closer to the ships walls. A lower center of gravity would provide adequate stability.

The trireme was constructed to maximize all traits of the ship to the point where if any changes were made the design would be compromised. Speed was maximized to the point where any less weight would have resulted in considerable losses to the ship's integrity. The center of gravity was placed at the lowest possible position where the Thalamian tholes were just above the waterline which retained the ship's resistance to waves and the possible rollover. If the center of gravity were placed any higher, the additional beams needed to restore stability would have resulted in the exclusion of the Thalamian tholes due to the reduced hull space. The purpose of the area just below the center of gravity and the waterline known as the ''hypozomata'' (ὑποζώματα) was to allow bending of the hull when faced with up to 90 kN of force. The calculations of forces that could have been absorbed by the ship are arguable because there is not enough evidence to confirm the exact process of jointing used in ancient times. In a modern reconstruction of the ship, a polysulphide sealant was used to compare to the caulking that evidence suggests was used; however this is also contentious because there is simply not enough evidence to authentically reproduce the triereis seams.

Triremes required a great deal of upkeep in order to stay afloat, as references to the replacement of ropes, sails, rudders, oars and masts in the middle of campaigns suggest.Hanson (2006), p. 260Fields (2007), p. 10 They also would become waterlogged if left in the sea for too long. In order to prevent this from happening, ships would have to be pulled from the water during the night. The use of lightwoods meant that the ship could be carried ashore by as few as 140 men.'' IG'' I.153 Beaching the ships at night, however, would leave the troops vulnerable to surprise attacks. While well-maintained triremes would last up to 25 years, during the Peloponnesian War, Athens had to build nearly 20 triremes a year to maintain their fleet of 300.

The Athenian trireme had two great cables of about 47 mm in diameter and twice the ship's length called ''hypozomata'' (undergirding), and carried two spares. They were possibly rigged fore and aft from end to end along the middle line of the hull just under the main beams and tensioned to 13.5 tonnes force. The ''hypozomata'' were considered important and secret: their export from Athens was a capital offense. This cable would act as a stretched tendon straight down the middle of the hull, and would have prevented hogging. Additionally, hull plank butts would remain in compression in all but the most severe sea conditions, reducing working of joints and consequent leakage. The ''hypozomata'' would also have significantly braced the structure of the trireme against the stresses of ramming, giving it an important advantage in combat. According to material scientist J.E. Gordon

James Edward Gordon (UK, 1913–1998) was one of the founders of materials science and biomechanics, and a well-known author of three books on structures and materials, which have been translated in many languages and are still widely used in scho ...

: "The ''hupozoma'' was therefore an essential part of the hulls of these ships; they were unable to fight, or even to go to sea at all, without it. Just as it used to be the practice to disarm modern warships by removing the breech-blocks from the guns, so, in classical times, disarmament commissioners used to disarm triremes by removing the ''hupozomata''."

Dimensions

Excavations of the ship sheds (''neōsoikoi'', νεώσοικοι) at the harbour of Zea inPiraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saron ...

, which was the main war harbour of ancient Athens, were first carried out by Dragatsis and Wilhelm Dörpfeld

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (26 December 1853 – 25 April 1940) was a German architect and archaeologist, a pioneer of stratigraphic excavation and precise graphical documentation of archaeological projects. He is famous for his work on Bronze Age site ...

in the 1880s. These have provided us with a general outline of the Athenian trireme. The sheds were ca. 40 m long and just 6 m wide. These dimensions are corroborated by the evidence of Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

, whereby the individual space allotted to each rower was 2 cubits

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding No ...

. With the Doric cubit of 0.49 m, this results in an overall ship length of just under 37 m. The height of the sheds' interior was established as 4.026 metres, leading to estimates that the height of the hull above the water surface was ca. 2.15 metres. Its draught was relatively shallow, about 1 metre, which, in addition to the relatively flat keel and low weight, allowed it to be beached easily.

Construction

esparto

Esparto, halfah grass, or esparto grass is a fiber produced from two species of perennial grasses of north Africa, Spain and Portugal. It is used for crafts, such as cords, basketry, and espadrilles. '' Stipa tenacissima'' and '' Lygeum spart ...

grass in the later third century BC.

The use of light woods meant that the ship could be carried ashore by as few as 140 men, but also that the hull soaked up water, which adversely affected its speed and maneuverability. But it was still faster than other warships.

Once the triremes were seaworthy, it is argued that they were highly decorated with, "eyes, nameplates, painted figureheads, and various ornaments". These decorations were used both to show the wealth of the patrician and to make the ship frightening to the enemy. The home port of each trireme was signaled by the wooden statue of a deity located above the bronze ram on the front of the ship.Hanson (2006), p. 239 In the case of Athens, since most of the fleet's triremes were paid for by wealthy citizens, there was a natural sense of competition among the patricians to create the "most impressive" trireme, both to intimidate the enemy and to attract the best oarsmen. Of all military expenditure, triremes were the most labor- and (in terms of men and money) investment-intensive.

Once the triremes were seaworthy, it is argued that they were highly decorated with, "eyes, nameplates, painted figureheads, and various ornaments". These decorations were used both to show the wealth of the patrician and to make the ship frightening to the enemy. The home port of each trireme was signaled by the wooden statue of a deity located above the bronze ram on the front of the ship.Hanson (2006), p. 239 In the case of Athens, since most of the fleet's triremes were paid for by wealthy citizens, there was a natural sense of competition among the patricians to create the "most impressive" trireme, both to intimidate the enemy and to attract the best oarsmen. Of all military expenditure, triremes were the most labor- and (in terms of men and money) investment-intensive.

Propulsion and capabilities

The ship's primary propulsion came from the 170 oars (''kōpai''), arranged in three rows, with one man per oar. Evidence for this is provided by Thucydides, who records that theCorinthian Corinthian or Corinthians may refer to:

*Several Pauline epistles, books of the New Testament of the Bible:

**First Epistle to the Corinthians

**Second Epistle to the Corinthians

**Third Epistle to the Corinthians (Orthodox)

*A demonym relating to ...

oarsmen carried "each his oar, cushion (''hypersion'') and oarloop". The ship also had two masts, a main (''histos megas'') and a small foremast (''histos akateios''), with square sails, while steering was provided by two steering oars at the stern (one at the port side, one to starboard).

Classical sources indicate that the trireme was capable of sustained speeds of ca. 6 knots at relatively leisurely oaring. There is also a reference by Xenophon of a single day's voyage from Byzantium to Heraclea Pontica

__NOTOC__

Heraclea Pontica (; gr, Ἡράκλεια Ποντική, Hērakleia Pontikē), known in Byzantine and later times as Pontoheraclea ( gr, Ποντοηράκλεια, Pontohērakleia), was an ancient city on the coast of Bithynia in Asi ...

, which translates as an average speed of 7.37 knots. These figures seem to be corroborated by the tests conducted with the reconstructed '' Olympias'': a maximum speed of 8 knots and a steady speed of 4 knots could be maintained, with half the crew resting at a time. Given the imperfect nature of the reconstructed ship, as well as the fact that it was manned by totally untrained modern men and women, it is reasonable to suggest that ancient triremes, expertly built and navigated by trained men, would attain higher speeds.

The distance a trireme could cover in a given day depended much on the weather. On a good day, the oarsmen, rowing for 6–8 hours, could propel the ship between . There were rare instances, however, when experienced crews and new ships were able to cover nearly twice that distance (Thucydides mentions a trireme travelling 300 kilometres in one day). The commanders of the triremes also had to stay aware of the condition of their men. They had to keep their crews comfortably paced, so as not to exhaust them before battle.

Crew

The total complement (''plērōma'') of the ship was about 200. These were divided into the 170 rowers (''eretai''), who provided the ship's motive power, the deck crew headed by the trierarch and a marine detachment. For the crew of Athenian triremes, the ships were an extension of their democratic beliefs. Rich and poor rowed alongside each other.Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson (born September 5, 1953) is an American commentator, classicist, and military historian. He has been a commentator on modern and ancient warfare and contemporary politics for ''The New York Times'', ''Wall Street Journal'', ...

argues that this "served the larger civic interest of acculturating thousands as they worked together in cramped conditions and under dire circumstances."

During the Peloponnesian War, there were a few variations to the typical crew layout of a trireme. One was a drastically reduced number of oarsmen, so as to use the ship as a troop transport. The thranites would row from the top benches while the rest of the space, below, would be filled with hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The f ...

. In another variation, the Athenians used 10 or so trireme for transporting horses. Such triremes had 60 oarsmen, and rest of the ship was for horses.

The trireme was designed for day-long journeys, with no capacity to stay at sea overnight, or to carry the provisions needed to sustain its crew overnight. Each crewman required 2 gallons (7.6 l) of fresh drinking water to stay hydrated each day, but it is unknown quite how this was stored and distributed. This meant that all those aboard were dependent upon the land and peoples of wherever they landed each night for supplies. Sometimes this would entail traveling up to eighty kilometres in order to procure provisions. In the Peloponnesian War, the beached Athenian fleet was caught unawares on more than one occasion, while out looking for food ( Battle of Syracuse and Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since ...

). Cities visited, which suddenly found themselves needing to provide for large numbers of sailors, usually did not mind the extra business, though those in charge of the fleet had to be careful not to deplete them of resources.

Trierarch

In Athens, the ship's captain was known as thetrierarch

Trierarch ( gr, τριήραρχος, triērarchos) was the title of officers who commanded a trireme (''triēres'') in the classical Greek world.

In Classical Athens, the title was associated with the trierarchy (τριηραρχία, ''triēr ...

(''triērarchos''). He was a wealthy Athenian citizen (usually from the class of the '' pentakosiomedimnoi''), responsible for manning, fitting out and maintaining the ship for his liturgical year at least; the ship itself belonged to Athens. The ''triērarchia'' was one of the liturgies

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

of ancient Athens; although it afforded great prestige, it constituted a great financial burden, so that in the 4th century, it was often shared by two citizens, and after 397 BC it was assigned to special boards.

Deck crew

The deck and command crew (''hypēresia'') was headed by the helmsman, the ''kybernētēs'', who was always an experienced seaman and was often the commander of the vessel. These experienced sailors were to be found on the upper levels of the triremes. Other officers were the bow lookout (''prōreus'' or ''prōratēs''), the boatswain (''keleustēs''), the quartermaster (''pentēkontarchos''), the shipwright (''naupēgos''), the piper (''aulētēs'') who gave the rowers' rhythm and two superintendents (''toicharchoi''), in charge of the rowers on each side of the ship. What constituted these sailors' experience was a combination of superior rowing skill (physical stamina and/or consistency in hitting with a full stroke) and previous battle experience. The sailors were likely in their thirties and forties. In addition, there were ten sailors handling the masts and the sails.Rowers

galley slave

A galley slave was a slave rowing in a galley, either a convicted criminal sentenced to work at the oar (''French'': galérien), or a kind of human chattel, often a prisoner of war, assigned to the duty of rowing.

In the ancient Mediterranean ...

s but of free men. In the Athenian case in particular, service in ships was the integral part of the military service provided by the lower classes, the '' thētai'', although metics

In ancient Greece, a metic ( Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a foreign resident of Athens, one who did not have citizen rights in their Greek city-state ('' polis'') of residence.

Origin

The history of foreign ...

and hired foreigners were also accepted. Although it has been argued that slaves formed part of the rowing crew in the Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a devas ...

, a typical Athenian trireme crew during the Peloponnesian War consisted of 80 citizens, 60 metics and 60 foreign hands. Indeed, in the few emergency cases where slaves were used to crew ships, these were deliberately set free, usually before being employed. For instance, the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse

Dionysius I or Dionysius the Elder ( 432 – 367 BC) was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse, in Sicily. He conquered several cities in Sicily and southern Italy, opposed Carthage's influence in Sicily and made Syracuse the most powerful of the Western Gre ...

once set all slaves of Syracuse free to man his galleys, employing thus freedmen, but otherwise relied on citizens and foreigners as oarsmen.

In the Athenian navy, the crews enjoyed long practice in peacetime, becoming skilled professionals and ensuring Athens' supremacy in naval warfare. The rowers were divided according to their positions in the ship into ''thranitai'', ''zygitai'', and ''thalamitai''. According to the excavated Naval Inventories, lists of ships' equipment compiled by the Athenian naval boards, there were:

* 62 ''thranitai'' in the top row (''thranos'' means "deck"). They rowed through the ''parexeiresia'', an outrigger which enabled the inclusion of the third row of oars without significant increase to the height and loss of stability of the ship. Greater demands were placed upon their strength and synchronization than on those of the other two rows.Fields (2007), p. 13

* 54 ''zygitai'' in the middle row, named after the beams (''zygoi'') on which they sat.

* 54 ''thalamitai'' or ''thalamioi'' in the lowest row, (''thalamos'' means "hold"). Their position was certainly the most uncomfortable, being underneath their colleagues and also exposed to the water entering through the oarholes, despite the use of the ''askōma'', a leather sleeve through which the oar emerged.

Most of the rowers (108 of the 170 - the ''zygitai'' and ''thalamitai''), due to the design of the ship, were unable to see the water and therefore, rowed blindly,Hanson (2006), p. 240 therefore coordinating the rowing required great skill and practice. It is not known exactly how this was done, but there are literary and visual references to the use of gestures and pipe playing to convey orders to rowers. In the sea trials of the reconstruction '' Olympias'', it was evident that this was a difficult problem to solve, given the amount of noise that a full rowing crew generated. In Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his for ...

' play ''The Frogs

''The Frogs'' ( grc-gre, Βάτραχοι, Bátrakhoi, Frogs; la, Ranae, often abbreviated ''Ran.'' or ''Ra.'') is a comedy written by the Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. It was performed at the Lenaia, one of the Festivals of Dionysus in ...

'' two different rowing chants can be found: "''ryppapai''" and "''o opop''", both corresponding quite well to the sound and motion of the oar going through its full cycle.

Marines

A varying number of marines (''epibatai''), usually 10–20, were carried aboard for boarding actions. At the Battle of Salamis, each Athenian ship was recorded to have 14hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The f ...

and 4 archers (usually Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

mercenaries) on board, but Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

narrates that the Chiots had 40 hoplites on board at Lade Lade may refer to:

People

* Brendon Lade (born 1976), an Australian rules footballer

* Sir John Lade (1759–1838), a baronet and Regency horse-breeder

* Heinrich Eduard von Lade (1817–1904), a German banker and amateur astronomer

* The Jarls ...

and that the Persian ships carried a similar number. This reflects the different practices between the Athenians and other, less professional navies. Whereas the Athenians relied on speed and maneuverability, where their highly trained crews had the advantage, other states favored boarding, in a situation that closely mirrored the one that developed during the First Punic War. Grappling hooks would be used both as a weapon and for towing damaged ships (ally or enemy) back to shore. When the triremes were alongside each other, marines would either spear the enemy or jump across and cut the enemy down with their swords.Hanson (2006), p. 254 As the presence of too many heavily armed hoplites on deck tended to destabilize the ship, the ''epibatai'' were normally seated, only rising to carry out any boarding action. The hoplites belonged to the middle social classes, so that they came immediately next to the trierarch in status aboard the ship.

Tactics

In the ancient world, naval combat relied on two methods: boarding andramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege weapon used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus, ...

. Artillery in the form of ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant ...

s and catapults

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of store ...

was widespread, especially in later centuries, but its inherent technical limitations meant that it could not play a decisive role in combat. The method for boarding was to brush alongside the enemy ship, with oars drawn in, in order to break the enemy's oars and render the ship immobile (which disables the enemy ship from simply getting away), then to board the ship and engage in hand to hand combat.

Rams (''embola'') were fitted to the prows of warships, and were used to rupture the hull of the enemy ship. The preferred method of attack was to come in from astern, with the aim not of creating a single hole, but of rupturing as big a length of the enemy vessel as possible. The speed necessary for a successful impact depended on the angle of attack; the greater the angle, the lesser the speed required. At 60 degrees, 4 knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainme ...

was enough to penetrate the hull, while it increased to 8 knots at 30 degrees. If the target for some reason was in motion in the direction of the attacker, even less speed was required, and especially if the hit came amidships. The Athenians especially became masters in the art of ramming, using light, un- decked (''aphraktai'') triremes.

In either case, the masts and railings of the ship were taken down prior to engagement to reduce the opportunities for opponents' grappling hooks.

On-board forces

Unlike the naval warfare of other eras, boarding an enemy ship was not the primary offensive action of triremes. Triremes' small size allowed for a limited number ofmarines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

to be carried aboard. During the 5th and 4th centuries, the trireme's strength was in its maneuverability and speed, not its armor or boarding force. That said, fleets less confident in their ability to ram were prone to load more marines onto their ships.

On the deck of a typical trireme in the Peloponnesian War there were 4 or 5 archers and 10 or so marines.Hanson (2006), p. 242 These few troops were peripherally effective in an offensive sense, but critical in providing defense for the oarsmen. Should the crew of another trireme board, the marines were all that stood between the enemy troops and the slaughter of the men below. It has also been recorded that if a battle were to take place in the calmer water of a harbor, oarsmen would join the offensive and throw stones (from a stockpile aboard) to aid the marines in harassing/attacking other ships.

Naval strategy in the Peloponnesian War

Squadrons of triremes employed a variety of tactics. The ''periplous'' ( Gk., "sailing around") involved outflanking or encircling the enemy so as to attack them in the vulnerable rear; the ''diekplous'' (Gk., "Sailing out through") involved a concentrated charge so as to break a hole in the enemy line, allowing galleys to break through and then wheel to attack the enemy line from behind; and the ''kyklos'' (Gk., "circle") and the ''mēnoeidēs kyklos'' (Gk. "half-circle"; literally, "moon-shaped (i.e. crescent-shaped) circle"), were defensive tactics to be employed against these manoeuvres. In all of these manoeuvres, the ability to accelerate faster, row faster, and turn more sharply than one's enemy was very important.

Athens' strength in the Peloponnesian War came from its navy, whereas Sparta's came from its land-based Hoplite army. As the war progressed however the Spartans came to realize that if they were to undermine

Squadrons of triremes employed a variety of tactics. The ''periplous'' ( Gk., "sailing around") involved outflanking or encircling the enemy so as to attack them in the vulnerable rear; the ''diekplous'' (Gk., "Sailing out through") involved a concentrated charge so as to break a hole in the enemy line, allowing galleys to break through and then wheel to attack the enemy line from behind; and the ''kyklos'' (Gk., "circle") and the ''mēnoeidēs kyklos'' (Gk. "half-circle"; literally, "moon-shaped (i.e. crescent-shaped) circle"), were defensive tactics to be employed against these manoeuvres. In all of these manoeuvres, the ability to accelerate faster, row faster, and turn more sharply than one's enemy was very important.

Athens' strength in the Peloponnesian War came from its navy, whereas Sparta's came from its land-based Hoplite army. As the war progressed however the Spartans came to realize that if they were to undermine Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelo ...

' strategy of outlasting the Peloponnesians by remaining within the walls of Athens indefinitely (a strategy made possible by Athens' Long Walls

Although long walls were built at several locations in ancient Greece, notably Corinth and Megara, the term Long Walls ( grc, Μακρὰ Τείχη ) generally refers to the walls that connected Athens main city to its ports at Piraeus and Phal ...

and fortified port of Piraeus), they were going to have to do something about Athens superior naval force. Once Sparta gained Persia as an ally, they had the funds necessary to construct the new naval fleets necessary to combat the Athenians. Sparta was able to build fleet after fleet, eventually destroying the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since ...

. The Spartan General Brasidas summed up the difference in approach to naval warfare between the Spartans and the Athenians: "Athenians relied on speed and maneuverability on the open seas to ram at will clumsier ships; in contrast, a Peloponnesian armada might win only when it fought near land in calm and confined waters, had the greater number of ships in a local theater, and if its better-trained marines on deck and hoplites on shore could turn a sea battle into a contest of infantry." In addition, compared to the high-finesse of the Athenian navy (superior oarsmen who could outflank and ram enemy triremes from the side), the Spartans (as well as their allies and other enemies of Athens) would focus mainly on ramming Athenian triremes head on. It would be these tactics, in combination with those outlined by Brasidas, that led to the defeat of the Athenian fleet at the Second Battle of Syracuse during the Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a devas ...

.

Casualties

Once a naval battle was under way, for the men involved, there were numerous ways for them to meet their end. Drowning was perhaps the most common way for a crew member to perish. Once a trireme had been rammed, the ensuing panic that engulfed the men trapped below deck no doubt extended the amount of time it took the men to escape. Inclement weather would greatly decrease the crew's odds of survival, leading to a situation like that off Cape Athos in 411 (12 of 10,000 men were saved). An estimated 40,000 Persians died in the Battle of Salamis. In the Peloponnesian War, after theBattle of Arginusae

The naval Battle of Arginusae took place in 406 BC during the Peloponnesian War near the city of Canae in the Arginusae islands, east of the island of Lesbos. In the battle, an Athenian fleet commanded by eight strategoi defeated a Spartan fle ...

, six Athenian generals were executed for failing to rescue several hundred of their men clinging to wreckage in the water.

If the men did not drown, they might be taken prisoner by the enemy. In the Peloponnesian War, "Sometimes captured crews were brought ashore and either cut down or maimed - often grotesquely, by cutting off the right hand or thumb to guarantee that they could never row again." The image found on an early-5th-century black-figure

Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic ( grc, , }), is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE, although there are ...

, depicting prisoners bound and thrown into the sea being pushed and prodded under water with poles and spears, shows that enemy treatment of captured sailors in the Peloponnesian War was often brutal.Hanson (2006), p. 248 Being speared amid the wreckage of destroyed ships was likely a common cause of death for sailors in the Peloponnesian War.

Naval battles were far more of a spectacle than the hoplite battles on land. Sometimes the battles raging at sea were watched by thousands of spectators on shore. Along with this greater spectacle, came greater consequences for the outcome of any given battle. Whereas the average percentage of fatalities from a land battle were between 10 and 15%, in a sea battle, the forces engaged ran the risk of losing their entire fleet. The number of ships and men in battles was sometimes very high. At the Battle of Arginusae

The naval Battle of Arginusae took place in 406 BC during the Peloponnesian War near the city of Canae in the Arginusae islands, east of the island of Lesbos. In the battle, an Athenian fleet commanded by eight strategoi defeated a Spartan fle ...

for example, 263 ships were involved, making for a total of 55,000 men, and at the Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since ...

more than 300 ships and 60,000 seamen were involved.Hanson (2006), p. 264 In Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since ...

, the city-state of Athens lost what was left of its navy: the once 'invincible' thalassocracy

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy sometimes also maritime empire, is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples ...

lost 170 ships (costing some 400 talents), and the majority of the crews were either killed, captured or lost.

Changes of engagement and construction

During the

During the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, the light trireme was supplanted by larger warships in dominant navies, especially the pentere/ quinquereme. The maximum practical number of oar banks a ship could have was three. So the number in the type name did not refer to the banks of oars any more (as for biremes and triremes), but to the number of rowers per vertical section, with several men on each oar. The reason for this development was the increasing use of armour on the bows of warships against ramming attacks, which again required heavier ships for a successful attack. This increased the number of rowers per ship, and also made it possible to use less well-trained personnel for moving these new ships. This change was accompanied by an increased reliance on tactics like boarding, missile skirmishes and using warships as platforms for artillery