Totentanz Maria im Fels Beram.JPG on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

), also called the Dance of Death, is an artistic genre of allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death.

The ''Danse Macabre'' consists of the dead, or a personification of death

Death is frequently imagined as a personified force. In some mythologies, a character known as the Grim Reaper (usually depicted as a berobed skeleton wielding a scythe) causes the victim's death by coming to collect that person's soul. Other b ...

, summoning representatives from all walks of life to dance along to the grave, typically with a pope, emperor, king, child

A child ( : children) is a human being between the stages of birth and puberty, or between the developmental period of infancy and puberty. The legal definition of ''child'' generally refers to a minor, otherwise known as a person younger ...

, and laborer

A laborer (or labourer) is a person who works in manual labor types in the construction industry workforce. Laborers are in a working class of wage-earners in which their only possession of significant material value is their labor. Industries e ...

. The effect was both frivolous, and terrifying; beseeching its audience to react emotionally. It was produced as ''memento mori

''Memento mori'' (Latin for 'remember that you ave todie'

The earliest recorded visual example is the lost mural on the South wall of the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents in Paris. It was painted in 1424–25 during the regency of John, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435). It features an emphatic inclusion of a dead crowned king at a time when France did not have a crowned king. The mural may well have had a political subtext.

There were also painted schemes in Basel (the earliest dating from ); a series of paintings on canvas by Bernt Notke (1440–1509) in Lübeck (1463); the initial fragment of the original Bernt Notke painting ''Danse Macabre (Notke), Danse Macabre'' (accomplished at the end of the 15th century) in the St. Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, St Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, Estonia; the painting at the back wall of the chapel of Sv. Marija na Škrilinama in the Istrian town of Beram (1474), painted by Vincent of Kastav; the painting in the Holy Trinity Church (Hrastovlje), Holy Trinity Church of Hrastovlje, Istria by John of Kastav (1490).

The earliest recorded visual example is the lost mural on the South wall of the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents in Paris. It was painted in 1424–25 during the regency of John, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435). It features an emphatic inclusion of a dead crowned king at a time when France did not have a crowned king. The mural may well have had a political subtext.

There were also painted schemes in Basel (the earliest dating from ); a series of paintings on canvas by Bernt Notke (1440–1509) in Lübeck (1463); the initial fragment of the original Bernt Notke painting ''Danse Macabre (Notke), Danse Macabre'' (accomplished at the end of the 15th century) in the St. Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, St Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, Estonia; the painting at the back wall of the chapel of Sv. Marija na Škrilinama in the Istrian town of Beram (1474), painted by Vincent of Kastav; the painting in the Holy Trinity Church (Hrastovlje), Holy Trinity Church of Hrastovlje, Istria by John of Kastav (1490).

A notable example was painted on the cemetery walls of the Dominican Abbey, in Bern, by Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484–1530) in 1516/7. This work of art was destroyed when the wall was torn down in 1660, but a 1649 copy by Albrecht Kauw (1621–1681) is extant. There was also a ''Dance of Death'' painted around 1430 and displayed on the walls of Pardon Churchyard at Old St Paul's Cathedral, London, with texts by John Lydgate (1370–1451) known as the 'Dance of (St) Poulys', which was destroyed in 1549.

The deathly crisis of the Late Middle Ages, horrors of the 14th century such as recurring famines, the Hundred Years' War in France, and, most of all, the Black Death, were culturally assimilated throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penance, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The ''Danse Macabre'' combines both desires: in many ways similar to the medieval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didacticism, didactic dialogue poem to remind people of the inevitability of death and to advise them strongly to be prepared at all times for death (see ''

A notable example was painted on the cemetery walls of the Dominican Abbey, in Bern, by Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484–1530) in 1516/7. This work of art was destroyed when the wall was torn down in 1660, but a 1649 copy by Albrecht Kauw (1621–1681) is extant. There was also a ''Dance of Death'' painted around 1430 and displayed on the walls of Pardon Churchyard at Old St Paul's Cathedral, London, with texts by John Lydgate (1370–1451) known as the 'Dance of (St) Poulys', which was destroyed in 1549.

The deathly crisis of the Late Middle Ages, horrors of the 14th century such as recurring famines, the Hundred Years' War in France, and, most of all, the Black Death, were culturally assimilated throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penance, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The ''Danse Macabre'' combines both desires: in many ways similar to the medieval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didacticism, didactic dialogue poem to remind people of the inevitability of death and to advise them strongly to be prepared at all times for death (see ''

Background

Historian Francis Rapp (1926–2020) writes that "''Christians were moved by the sight of the Infant Jesus playing on his mother's knee; their hearts were touched by the Pietà; and patron saints reassured them by their presence. But, all the while, the danse macabre urged them not to forget the end of all earthly things.''" This ''Danse Macabre'' was enacted at village pageants and at Masque, court masques, with people "''dressing up as corpses from various strata of society''", and may have been the origin of costumes worn during Allhallowtide. In her thesis, ''The Black Death and its Effect on 14th and 15th Century Art'' Anna Louise Des Ormeaux describes the effect of the Black Death on art, mentioning the ''Danse Macabre'' as she does so:''Some plague art contains gruesome imagery that was directly influenced by the mortality of the plague or by the medieval fascination with the macabre and awareness of death that were augmented by the plague. Some plague art documents psychosocial responses to the fear that plague aroused in its victims. Other plague art is of a subject that directly responds to people's reliance on religion to give them hope.''The cultural impact of mass outbreaks of disease, of pandemics, are not fleeting or temporary. The effect can endure past the initial stages of outbreak, in its deep etching upon the culture and society. This can be seen in the artworks and motifs of ''Danse Macabre'' as people attempted to cope with the death surrounding them.

Paintings

The earliest recorded visual example is the lost mural on the South wall of the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents in Paris. It was painted in 1424–25 during the regency of John, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435). It features an emphatic inclusion of a dead crowned king at a time when France did not have a crowned king. The mural may well have had a political subtext.

There were also painted schemes in Basel (the earliest dating from ); a series of paintings on canvas by Bernt Notke (1440–1509) in Lübeck (1463); the initial fragment of the original Bernt Notke painting ''Danse Macabre (Notke), Danse Macabre'' (accomplished at the end of the 15th century) in the St. Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, St Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, Estonia; the painting at the back wall of the chapel of Sv. Marija na Škrilinama in the Istrian town of Beram (1474), painted by Vincent of Kastav; the painting in the Holy Trinity Church (Hrastovlje), Holy Trinity Church of Hrastovlje, Istria by John of Kastav (1490).

The earliest recorded visual example is the lost mural on the South wall of the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents in Paris. It was painted in 1424–25 during the regency of John, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435). It features an emphatic inclusion of a dead crowned king at a time when France did not have a crowned king. The mural may well have had a political subtext.

There were also painted schemes in Basel (the earliest dating from ); a series of paintings on canvas by Bernt Notke (1440–1509) in Lübeck (1463); the initial fragment of the original Bernt Notke painting ''Danse Macabre (Notke), Danse Macabre'' (accomplished at the end of the 15th century) in the St. Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, St Nicholas' Church, Tallinn, Estonia; the painting at the back wall of the chapel of Sv. Marija na Škrilinama in the Istrian town of Beram (1474), painted by Vincent of Kastav; the painting in the Holy Trinity Church (Hrastovlje), Holy Trinity Church of Hrastovlje, Istria by John of Kastav (1490).

A notable example was painted on the cemetery walls of the Dominican Abbey, in Bern, by Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484–1530) in 1516/7. This work of art was destroyed when the wall was torn down in 1660, but a 1649 copy by Albrecht Kauw (1621–1681) is extant. There was also a ''Dance of Death'' painted around 1430 and displayed on the walls of Pardon Churchyard at Old St Paul's Cathedral, London, with texts by John Lydgate (1370–1451) known as the 'Dance of (St) Poulys', which was destroyed in 1549.

The deathly crisis of the Late Middle Ages, horrors of the 14th century such as recurring famines, the Hundred Years' War in France, and, most of all, the Black Death, were culturally assimilated throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penance, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The ''Danse Macabre'' combines both desires: in many ways similar to the medieval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didacticism, didactic dialogue poem to remind people of the inevitability of death and to advise them strongly to be prepared at all times for death (see ''

A notable example was painted on the cemetery walls of the Dominican Abbey, in Bern, by Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484–1530) in 1516/7. This work of art was destroyed when the wall was torn down in 1660, but a 1649 copy by Albrecht Kauw (1621–1681) is extant. There was also a ''Dance of Death'' painted around 1430 and displayed on the walls of Pardon Churchyard at Old St Paul's Cathedral, London, with texts by John Lydgate (1370–1451) known as the 'Dance of (St) Poulys', which was destroyed in 1549.

The deathly crisis of the Late Middle Ages, horrors of the 14th century such as recurring famines, the Hundred Years' War in France, and, most of all, the Black Death, were culturally assimilated throughout Europe. The omnipresent possibility of sudden and painful death increased the religious desire for penance, but it also evoked a hysterical desire for amusement while still possible; a last dance as cold comfort. The ''Danse Macabre'' combines both desires: in many ways similar to the medieval mystery plays, the dance-with-death allegory was originally a didacticism, didactic dialogue poem to remind people of the inevitability of death and to advise them strongly to be prepared at all times for death (see ''memento mori

''Memento mori'' (Latin for 'remember that you ave todie'

File:Totentanz Maria im Fels Beram.JPG, The fresco at the back wall of the chapel of Sv. Marija na Škrilinama in the Istrian town of Beram (1474), painted by Vincent of Kastav, Croatia

File:Hrastovlje Dans3.jpg, Johannes de Castua: Detail of the ''Dance Macabre fresco'' (1490) in the Holy Trinity Church (Hrastovlje), Holy Trinity Church in Hrastovlje, Slovenia

File:Dance of Death (replica of 15th century fresco; National Gallery of Slovenia).jpg, ''Dance of Death'' (replica of 15th century fresco; National Gallery of Slovenia)

File:Totentanz in Hrastovlje.JPG, The famous ''Danse Macabre'' in Hrastovlje in the Holy Trinity Church (Hrastovlje), Holy Trinity Church

File:Trionfo della morte - Chiesa S. Maria Annunciata - Bienno (ph Luca Giarelli).jpg, ''Danse Macabre'' in St Maria in Bienno, 16th century

In his preface to the work Jean de Vauzèle, the Prior of Montrosier, addresses Jehanne de Tourzelle, the Abbess of the Convent at St. Peter at Lyons, and names Holbein's attempts to capture the ever-present, but never directly seen, abstract images of death "simulachres." He writes: "''[…] simulachres les dis ie vrayement, pour ce que simulachre vient de simuler, & faindre ce que n'est point.''" ("Simulachres they are most correctly called, for simulachre derives from the verb to simulate and to feign that which is not really there.") He next employs a trope from the

In his preface to the work Jean de Vauzèle, the Prior of Montrosier, addresses Jehanne de Tourzelle, the Abbess of the Convent at St. Peter at Lyons, and names Holbein's attempts to capture the ever-present, but never directly seen, abstract images of death "simulachres." He writes: "''[…] simulachres les dis ie vrayement, pour ce que simulachre vient de simuler, & faindre ce que n'est point.''" ("Simulachres they are most correctly called, for simulachre derives from the verb to simulate and to feign that which is not really there.") He next employs a trope from the

Mural paintings

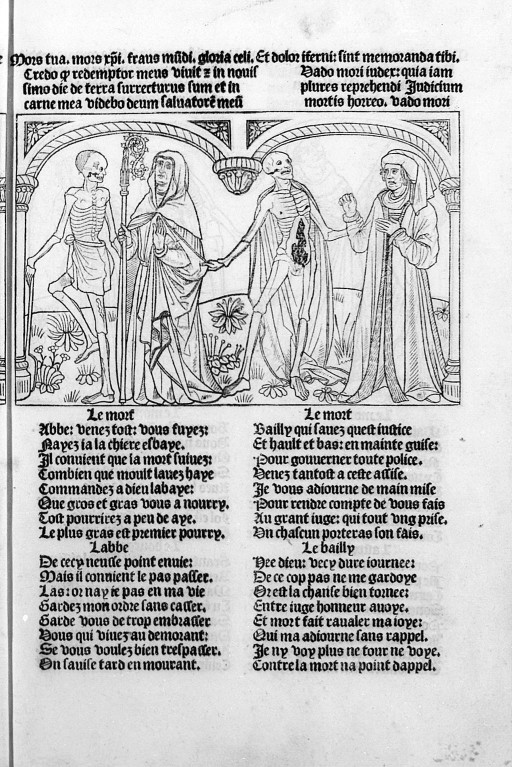

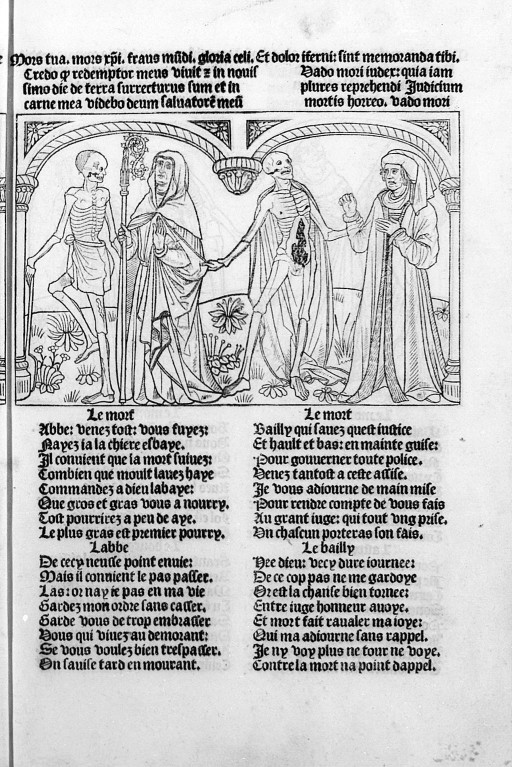

Frescoes and murals dealing with death had a long tradition, and were widespread. For example, the legend of the ''Three Living and the Three Dead.'' On a ride or hunt, three young gentlemen meet three cadavers (sometimes described as their ancestors) who warn them, ''Quod fuimus, estis; quod sumus, vos eritis'' ("What we were, you are; what we are, you will be"). Numerous mural versions of that legend from the 13th century onwards have survived (for instance, in the :de:Heiligen-Geist-Hospital (Wismar), Hospital Church of Wismar or the residential Longthorpe Tower outside Peterborough). Since they showed pictorial sequences of men and corpses covered with shrouds, those paintings are sometimes regarded as cultural precursors of the new genre. A ''Danse Macabre'' painting may show a round dance headed by Death or, more usually, a chain of alternating dead and live dancers. From the highest ranks of the mediaeval hierarchy (usually pope and emperor) descending to its lowest (beggar, peasant, and child), each mortal's hand is taken by an animated skeleton or cadaver. The famous ''Totentanz'' by Bernt Notke in St. Mary's Church, Lübeck (destroyed during the Allied bombing of Lübeck in World War II), presented the dead dancers as very lively and agile, making the impression that they were actually dancing, whereas their living dancing partners looked clumsy and passive. The apparent class distinction in almost all of these paintings is completely neutralized by Death as the ultimate equalizer, so that a sociocritical element is subtly inherent to the whole genre. The ''Totentanz'' of Metnitz, for example, shows how a pope crowned with his tiara is being led into Hell by Death. Usually, a short dialogue is attached to each pair of dancers, in which Death is summoning him (or, more rarely, her) to dance and the summoned is moaning about impending death. In the first printed ''Totentanz'' textbook (Anon.: ''Vierzeiliger oberdeutscher Totentanz'', Heidelberger Blockbuch, ), Death addresses, for example, the emperor: At the lower end of the ''Totentanz'', Death calls, for example, the peasant to dance, who answers: Various examples of ''Danse Macabre'' in Slovenia and Croatia below:Hans Holbein's woodcuts

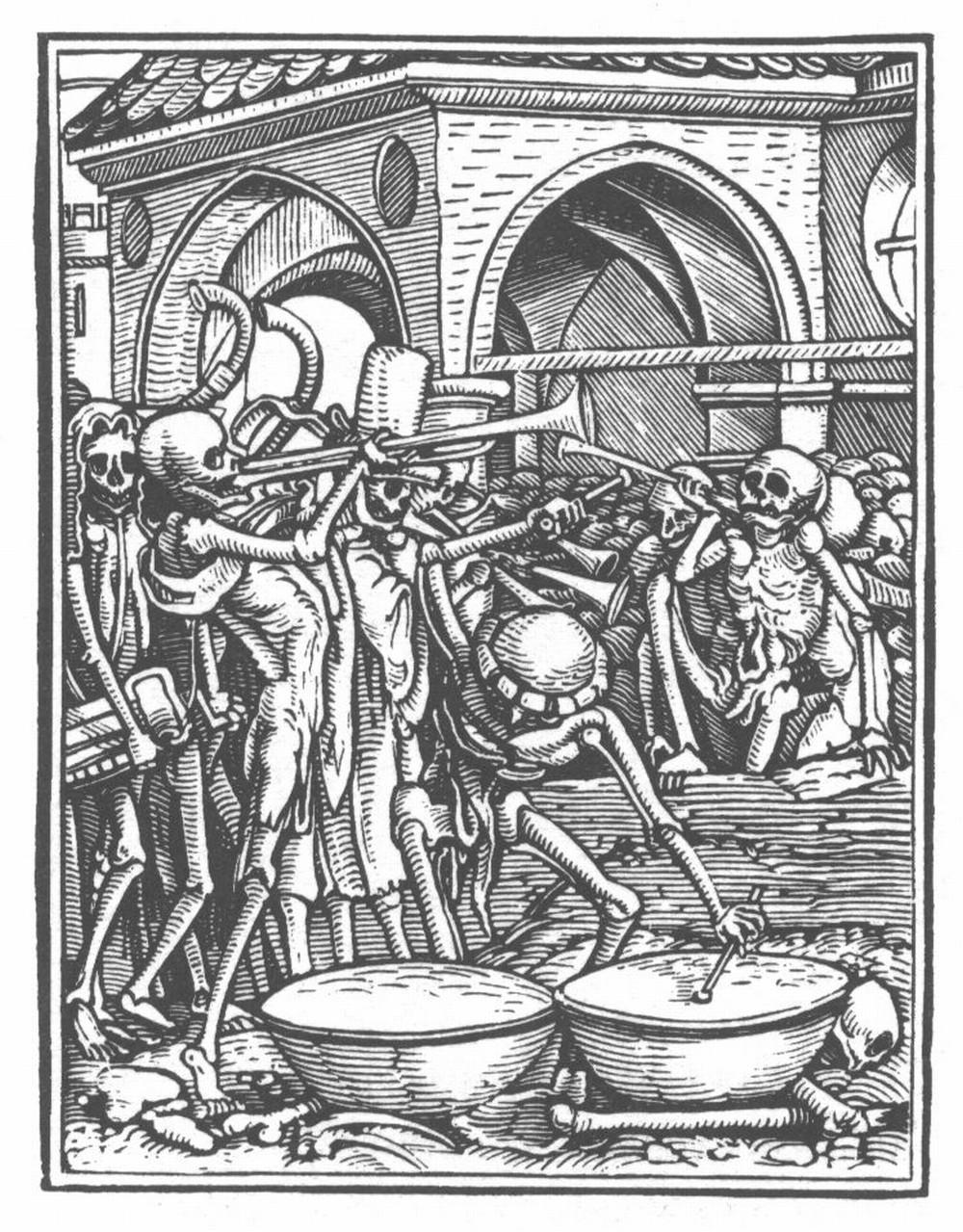

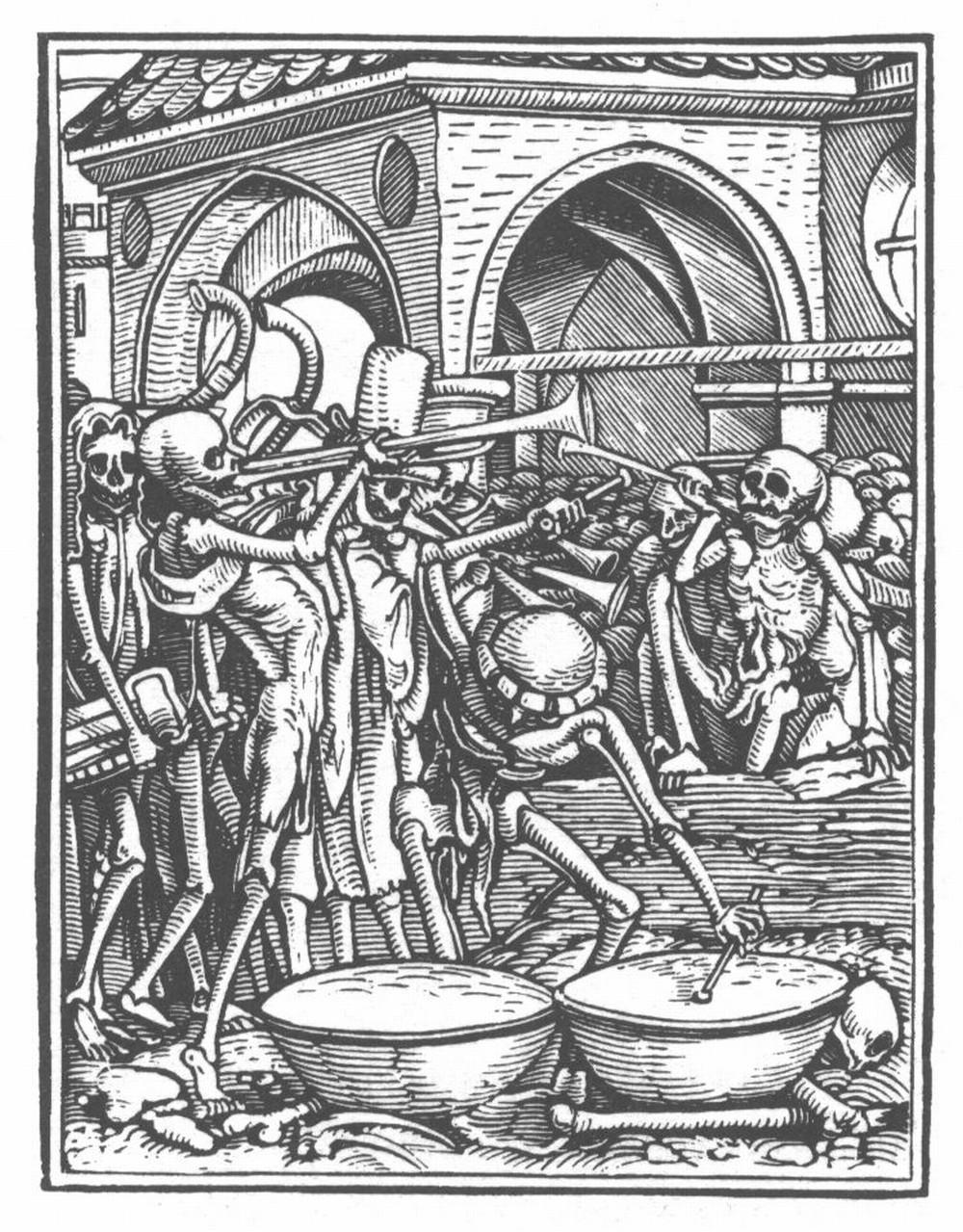

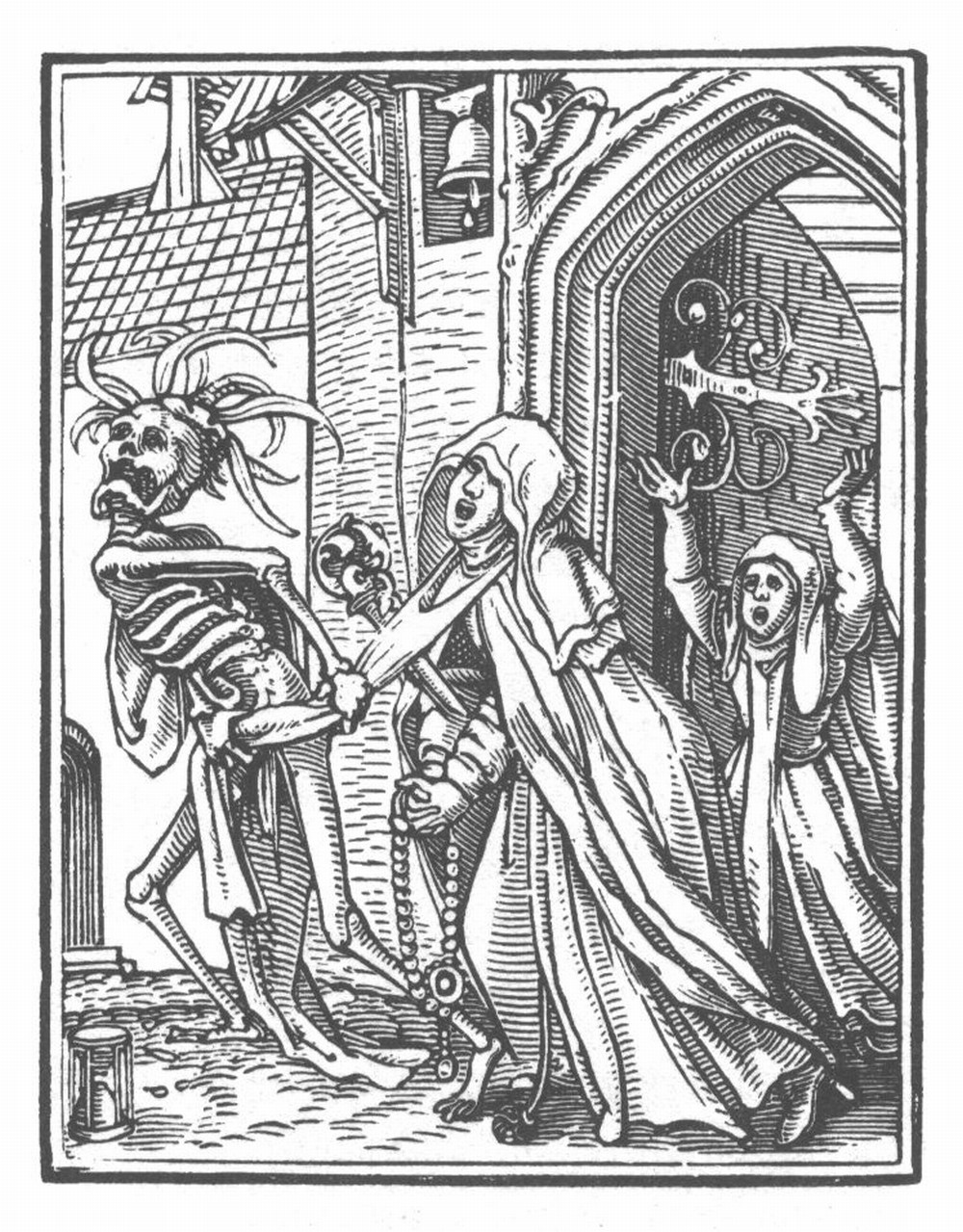

Renowned for his ''Dance of Death'' series, the famous designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) were drawn in 1526 while he was in Basel. They were cut in wood by the accomplished Formschneider (block cutter) Hans Lützelburger. William Ivins (quoting W. J. Linton) writes of Lützelburger's work wrote: "''Nothing indeed, by knife or by graver, is of higher quality than this man's doing.' For by common acclaim the originals are technically the most marvelous woodcuts ever made''." These woodcuts soon appeared in proofs with titles in German. The first book edition, containing forty-one woodcuts, was published at Lyons by the Treschsel brothers in 1538. The popularity of the work, and the currency of its message, are underscored by the fact that there were eleven editions before 1562, and over the sixteenth century perhaps as many as a hundred unauthorized editions and imitations. Ten further designs were added in later editions. The ''Dance of Death'' (1523–26) refashions the late-medievalallegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

of the ''Danse Macabre'' as a reformist satire, and one can see the beginnings of a gradual shift from traditional to reformed Christianity. That shift had many permutations however, and in a study Natalie Zemon Davis has shown that the contemporary reception and afterlife of Holbein's designs lent themselves to neither purely Catholic or Protestant doctrine, but could be outfitted with different surrounding prefaces and sermons as printers and writers of different political and religious leanings took them up. Most importantly, "''The pictures and the Bible quotations above them were the main attractions […] Both Catholics and Protestants wished, through the pictures, to turn men's thoughts to a Christian preparation for death.''".

The 1538 edition which contained Latin quotations from the Bible above Holbein's designs, and a French quatrain below composed by Gilles Corrozet (1510–1568) actually did not credit Holbein as the artist. It bore the title: Les simulachres & / HISTORIEES FACES / DE LA MORT, AUTANT ELE/gammēt pourtraictes, que artifi/ciellement imaginées. / A Lyon. / Soubz l'escu de COLOIGNE. / M.D. XXXVIII. ("Images and Illustrated facets of Death, as elegantly depicted as they are artfully conceived.") These images and workings of death as captured in the phrase "histories faces" of the title "are the particular exemplification of the way death works, the individual scenes in which the lessons of mortality are brought home to people of every station."

In his preface to the work Jean de Vauzèle, the Prior of Montrosier, addresses Jehanne de Tourzelle, the Abbess of the Convent at St. Peter at Lyons, and names Holbein's attempts to capture the ever-present, but never directly seen, abstract images of death "simulachres." He writes: "''[…] simulachres les dis ie vrayement, pour ce que simulachre vient de simuler, & faindre ce que n'est point.''" ("Simulachres they are most correctly called, for simulachre derives from the verb to simulate and to feign that which is not really there.") He next employs a trope from the

In his preface to the work Jean de Vauzèle, the Prior of Montrosier, addresses Jehanne de Tourzelle, the Abbess of the Convent at St. Peter at Lyons, and names Holbein's attempts to capture the ever-present, but never directly seen, abstract images of death "simulachres." He writes: "''[…] simulachres les dis ie vrayement, pour ce que simulachre vient de simuler, & faindre ce que n'est point.''" ("Simulachres they are most correctly called, for simulachre derives from the verb to simulate and to feign that which is not really there.") He next employs a trope from the memento mori

''Memento mori'' (Latin for 'remember that you ave todie'

Holbein's series shows the figure of "Death" in many disguises, confronting individuals from all walks of life. None escape Death's skeletal clutches, not even the pious. As Davis writes, "Holbein's pictures are independent dramas in which Death comes upon his victim in the midst of the latter's own surroundings and activities. This is perhaps nowhere more strikingly captured than in the wonderful blocks showing the plowman earning his bread by the sweat of his brow only to have his horses speed him to his end by Death. The Latin from the 1549 Italian edition pictured here reads: "In sudore vultus tui, vesceris pane tuo." ("Through the sweat of thy brow you shall eat your bread"), quoting Genesis 3.19. The Italian verses below translate: ("Miserable in the sweat of your brow,/ It is necessary that you acquire the bread you need eat,/ But, may it not displease you to come with me,/ If you are desirous of rest."). Or there is the nice balance in composition Holbein achieves between the heavy-laden traveling salesman insisting that he must still go to market while Death tugs at his sleeve to put down his wares once and for all: "Venite ad me, qui onerati estis." ("Come to me, all ye who [labor and] are heavy laden"), quoting Matthew 11.28. The Italian here translates: ("Come with me, wretch, who are weighed down,/ Since I am the dame who rules the whole world:/ Come and hear my advice,/ Because I wish to lighten you of this load.").

Holbein's series shows the figure of "Death" in many disguises, confronting individuals from all walks of life. None escape Death's skeletal clutches, not even the pious. As Davis writes, "Holbein's pictures are independent dramas in which Death comes upon his victim in the midst of the latter's own surroundings and activities. This is perhaps nowhere more strikingly captured than in the wonderful blocks showing the plowman earning his bread by the sweat of his brow only to have his horses speed him to his end by Death. The Latin from the 1549 Italian edition pictured here reads: "In sudore vultus tui, vesceris pane tuo." ("Through the sweat of thy brow you shall eat your bread"), quoting Genesis 3.19. The Italian verses below translate: ("Miserable in the sweat of your brow,/ It is necessary that you acquire the bread you need eat,/ But, may it not displease you to come with me,/ If you are desirous of rest."). Or there is the nice balance in composition Holbein achieves between the heavy-laden traveling salesman insisting that he must still go to market while Death tugs at his sleeve to put down his wares once and for all: "Venite ad me, qui onerati estis." ("Come to me, all ye who [labor and] are heavy laden"), quoting Matthew 11.28. The Italian here translates: ("Come with me, wretch, who are weighed down,/ Since I am the dame who rules the whole world:/ Come and hear my advice,/ Because I wish to lighten you of this load.").

treasure 4

* Meinolf Schumacher (2001), "Ein Kranz für den Tanz und ein Strich durch die Rechnung. Zu Oswald von Wolkenstein 'Ich spür ain tier' (Kl 6)", ''Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur'', vol. 123 (2001), pp. 253–273. * Ann Tukey Harrison (1994), with a chapter by Sandra L. Hindman, ''The Danse Macabre of Women: Ms.fr. 995 of the Bibliothèque Nationale'', Kent State University Press. . *Wilson, Derek (2006) ''Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man.'' London: Pimlico, Revised Edition.

Goethe and the "Totentanz"

''The Journal of English and Germanic Philology'' 48:4 Goethe Bicentennial Issue 1749–1949. 48:4, 582–587. * Hans Georg Wehrens (2012) ''Der Totentanz im alemannischen Sprachraum. "Muos ich doch dran - und weis nit wan"''. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg . * Elina Gertsman (2010), The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages. Image, Text, Performance. ''Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages'', 3. Turnhout, Brepols Publishers. *Sophie Oosterwijk (2004),

Of corpses, constables and kings: the Danse Macabre in late-medieval and renaissance culture

, ''The Journal of the British Archaeological Association'', 157, 61–90. * Sophie Oosterwijk (2006),

Muoz ich tanzen und kan nit gân?

Death and the infant in the medieval Danse Macabre', ''Word & Image'', 22:2, 146–64. * Sophie Oosterwijk (2008),

For no man mai fro dethes stroke fle

. Death and Danse Macabre iconography in memorial art', ''Church Monuments'', 23, 62–87, 166-68 * Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knoell (2011),

Mixed Metaphors. The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

'. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. . * Marek Żukow-Karczewski (1989), "Taniec śmierci (Dance macabre"), Życie Literackie (''Literary Life'' - literary review magazine), 43, 4. * Maricarmen Gómez Muntané (2017), ''El Llibre Vermell. Cantos y danzas de fines del Medioevo'', Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica, (chapter "Ad mortem festinamus' y la Danza de la Muerte").

A collection of historical images of the Danse Macabre

at Cornell's ''The Fantastic in Art and Fiction''

The Danse Macabre of Hrastovlje, Slovenia

''Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort: commonly called "The dance of death'

- 1869 photographic reproduction of original by Holbein Society with woodcuts, plus English translations and a biography of Holbein.

Sophie Oosterwijk (2009), '"Fro Paris to Inglond"? The danse macabre in text and image in late-medieval England', Doctoral thesis Leiden University available online.

Images of ''Danse Macabre'' (2001)

Conceptual performance by Antonia Svobodová and Mirek Vodrážka in Čajovna Pod Stromem Čajovým in Prague 22 May 2001'. *

Dance of Death, Chorea, ab eximio Macabro versibus Alemanicis edita et a Petro Desrey ... nuper emendata.

Paris, Gui Marchand, for Geoffroy de Marnef, 15 Oct. (Id. Oct.) 1490. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the Library of Congress

An introduction to the Dance of Death

Art & Design Library, Central Library, Edinburgh {{DEFAULTSORT:Dance Of Death Visual arts genres Caricature Dance in arts Death customs Fantastic art Horror fiction Iconography Medieval art Medieval drama Memento mori Skulls in art Epidemics in art

Holbein's series shows the figure of "Death" in many disguises, confronting individuals from all walks of life. None escape Death's skeletal clutches, not even the pious. As Davis writes, "Holbein's pictures are independent dramas in which Death comes upon his victim in the midst of the latter's own surroundings and activities. This is perhaps nowhere more strikingly captured than in the wonderful blocks showing the plowman earning his bread by the sweat of his brow only to have his horses speed him to his end by Death. The Latin from the 1549 Italian edition pictured here reads: "In sudore vultus tui, vesceris pane tuo." ("Through the sweat of thy brow you shall eat your bread"), quoting Genesis 3.19. The Italian verses below translate: ("Miserable in the sweat of your brow,/ It is necessary that you acquire the bread you need eat,/ But, may it not displease you to come with me,/ If you are desirous of rest."). Or there is the nice balance in composition Holbein achieves between the heavy-laden traveling salesman insisting that he must still go to market while Death tugs at his sleeve to put down his wares once and for all: "Venite ad me, qui onerati estis." ("Come to me, all ye who [labor and] are heavy laden"), quoting Matthew 11.28. The Italian here translates: ("Come with me, wretch, who are weighed down,/ Since I am the dame who rules the whole world:/ Come and hear my advice,/ Because I wish to lighten you of this load.").

Holbein's series shows the figure of "Death" in many disguises, confronting individuals from all walks of life. None escape Death's skeletal clutches, not even the pious. As Davis writes, "Holbein's pictures are independent dramas in which Death comes upon his victim in the midst of the latter's own surroundings and activities. This is perhaps nowhere more strikingly captured than in the wonderful blocks showing the plowman earning his bread by the sweat of his brow only to have his horses speed him to his end by Death. The Latin from the 1549 Italian edition pictured here reads: "In sudore vultus tui, vesceris pane tuo." ("Through the sweat of thy brow you shall eat your bread"), quoting Genesis 3.19. The Italian verses below translate: ("Miserable in the sweat of your brow,/ It is necessary that you acquire the bread you need eat,/ But, may it not displease you to come with me,/ If you are desirous of rest."). Or there is the nice balance in composition Holbein achieves between the heavy-laden traveling salesman insisting that he must still go to market while Death tugs at his sleeve to put down his wares once and for all: "Venite ad me, qui onerati estis." ("Come to me, all ye who [labor and] are heavy laden"), quoting Matthew 11.28. The Italian here translates: ("Come with me, wretch, who are weighed down,/ Since I am the dame who rules the whole world:/ Come and hear my advice,/ Because I wish to lighten you of this load.").

Musical settings

Musical settings of the motif include: * ''Mattasin oder Toden Tanz'', 1598, by August Nörmiger * ''Totentanz (Liszt), Totentanz. Paraphrase on "Dies irae."'' by Franz Liszt, 1849, a set of variations based on the plainsong melody "Dies Irae". * ''Danse macabre (Saint-Saëns), Danse Macabre'' by Camille Saint-Saëns, 1874 * ''Songs and Dances of Death'', 1875–77, by Modest Mussorgsky * ''Symphony No. 4 (Mahler), Symphony No. 4'', 2nd Movement, 1901, by Gustav Mahler * ''Totentanz der Prinzipien'', 1914, by Arnold Schönberg * ''The Green Table'', 1932, ballet by Kurt Jooss * ''Totentanz (Distler), Totentanz'', 1934, by Hugo Distler, inspired by the ''Lübecker Totentanz'' * "Scherzo (Dance of Death)," in Op. 14 ''Ballad of Heroes'', 1939, by Benjamin Britten * ''Piano Trio No. 2 (Shostakovich), Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor'', Op. 67, 4th movement, "Dance of Death," 1944, by Dmitri Shostakovich * ''Der Kaiser von Atlantis, Der Kaiser von Atlantis, oder Die Tod-Verweigerung'', 1944, by Viktor Ullmann and Peter Kien * ''Le Grand Macabre'', opera written by György Ligeti (Stockholm 1978) * ''Danse Macabre'', song, 1984, by Celtic Frost, Swiss Extreme metal music, extreme metal band * ''Danse_Macabre_(album), Dance Macabre'', 2001, album by The Faint * ''Dance of Death (album), Dance of Death'', 2003, an album and a song by Iron Maiden, Heavy metal music, heavy metal band * ''Cortège & Danse Macabre'' from the symphonic suite Cantabile (symphonic suite), ''Cantabile'', 2009, by Frederik Magle * ''Totentanz (Adès)'' by Thomas Adès, 2013, a piece for voices and orchestra based on the 15th century text. * ''La Danse Macabre'', song on the Shovel Knight soundtrack, 2014, by Jake Kaufman * ''Dance Macabre'', 2018, by Ghost (Swedish band), Swedish Heavy metal music, heavy metal band * La danse macabre, song, 2019, by Clément Belio, French multi-instrumentalistTextual examples of the Danse Macabre

The ''Danse Macabre'' was a frequent motif in poetry, drama and other written literature in the Middle Ages in several areas of western Europe. There is a Spanish , a French , and a German with various Latin manuscripts written during the 14th century. Printed editions of books began appearing in the 15th century, such as the ones produced by Guy Marchant of Paris. Similarly to the musical or artistic representations, the texts describe living and dead persons being called to dance or form a procession with Death. ''Danse Macabre'' texts were often, though not always, illustrated with illuminations and woodcuts. There is one danse macabre text devoted entirely to women: ''The Danse Macabre of Women''. This work survives in five manuscripts, and two printed editions. In it, 36 women of various ages, in Paris, are called from their daily lives and occupations to join the Dance with Death. An English translation of the French manuscript was published by Ann Tukey Harrison in 1994.Literary influence

The "Death and the Maiden (motif), Death and the Maiden motif", known from paintings since the early 16th century, is related to, and may have been derived from, the ''Danse Macabre''. It has received numerous treatments in various mediamost prominently Schubert's lied "Der Tod und das Mädchen" (1817) and the String Quartet No. 14 (Schubert), String Quartet No. 14 ''Death and the Maiden'', partly derived from its musical material. Further developments of the ''Danse Macabre'' motif include: * ''Godfather Death'', a fairy tale, collected by the Brothers Grimm (first published in 1812). * "After Holbein" (1928), short story by Edith Wharton, first published in the ''The Saturday Evening Post, Saturday Evening Post'' in May 1928; republished in ''Certain People'' (1930) and in ''The New York Stories of Edith Wharton'', ed. Roxana Robinson (New York Review Books, 2007). * "Death and the Compass" (original title: "La muerte y la brújula", 1942), short story by Jorge Luis Borges. * A Danse Macabre scene is depicted near the end of Ingmar Bergman's 1957 film ''The Seventh Seal''. * "Death and the Senator", short story (1961) by Arthur C. Clarke. * "Dance Cadaverous" is a song written and performed by Wayne Shorter (released 1966). * ''Death and the King's Horseman'', play by Wole Soyinka (premiered 1975). * ''Dance with Death (album), Dance with Death'', a jazz album released in 1980 by Andrew Hill (jazz musician), Andrew Hill. * ''Danse Macabre (book), Danse Macabre'', a 1981 non-fiction work by Stephen King. * ''The Graveyard Book'', a 2008 novel by Neil Gaiman. Chapter five, "Danse Macabre", depicts the ghosts of the Graveyard dancing with the inhabitants of the Old Town. * "Death Dance" (2016), a song written and performed by American rock band, Sevendust. * "Dance Macabre (song), Dance Macabre", a song written and performed by Swedish metal or hard rock band Ghost (Swedish band), Ghost on their 2018 album ''Prequelle'', concentrating on the Black Death plague of the 14th century.See also

* Dancing Pallbearers * ''La Calavera Catrina'' * Medieval dance * ''Memento mori'' * ''The Skeleton Dance'' * ''Vanitas''Notes

References

*Bätschmann, Oskar, & Pascal Griener (1997), ''Hans Holbein.'' London: Reaktion Books. * Israil Bercovici (1998) ''O sută de ani de teatru evriesc în România'' ("One hundred years of Yiddish/Jewish theater in Romania"), 2nd Romanian-language edition, revised and augmented by Constantin Măciucă. Editura Integral (an imprint of Editurile Universala), Bucharest. . * James M. Clark (1947), ''The Dance of Death by Hans Holbein'', London. * James M. Clark (1950) ''The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages and Renaissance''. * André Corvisier (1998) ''Les danses macabres'', Presses Universitaires de France. . * Natalie Zemon Davis (1956), "Holbein's Pictures of Death and the Reformation at Lyons," ''Studies in the Renaissance'', vol. 3 (1956), pp. 97–130. * Rolf Paul Dreier (2010) ''Der Totentanz - ein Motiv der kirchlichen Kunst als Projektionsfläche für profane Botschaften (1425–1650)'', Leiden, with CD-ROM: Verzeichnis der Totentänze * Werner L. Gundersheimer (1971), ''The Dance of Death by Hans Holbein the Younger: A Complete Facsimile of the Original 1538 Edition of Les simulachres et histoirees faces de la Mort''. New york: Dover Publications, Inc. * William M. Ivins Jr. (1919), "Hans Holbein's Dance of Death," ''The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin'', vol. 14, no. 11 (Nov., 1919). pp. 231–235. * Landau, David, & Peter Parshall (1996), ''The Renaissance Print'', New Haven (CT): Yale, 1996. * Francesc Massip & Lenke Kovács (2004), ''El baile: conjuro ante la muerte. Presencia de lo macabro en la danza y la fiesta popular''. Ciudad Real, CIOFF-INAEM, 2004. * Sophie Oosterwijk (2008), 'Of dead kings, dukes and constables. The historical context of the Danse Macabre in late-medieval Paris', ''Journal of the British Archaeological Association'', 161, 131–62. * Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knoell (2011), ''Mixed Metaphors. The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe'', Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. . * Romania, National Library of ... - Illustrated Latin translation of the'' Danse Macabre'', late 15th centurytreasure 4

* Meinolf Schumacher (2001), "Ein Kranz für den Tanz und ein Strich durch die Rechnung. Zu Oswald von Wolkenstein 'Ich spür ain tier' (Kl 6)", ''Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur'', vol. 123 (2001), pp. 253–273. * Ann Tukey Harrison (1994), with a chapter by Sandra L. Hindman, ''The Danse Macabre of Women: Ms.fr. 995 of the Bibliothèque Nationale'', Kent State University Press. . *Wilson, Derek (2006) ''Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man.'' London: Pimlico, Revised Edition.

Further reading

* Henri Stegemeier (1939) ''The Dance of Death in Folksong, with an Introduction on the History of the Dance of Death.'' University of Chicago. * Henri Stegemeier (1949Goethe and the "Totentanz"

''The Journal of English and Germanic Philology'' 48:4 Goethe Bicentennial Issue 1749–1949. 48:4, 582–587. * Hans Georg Wehrens (2012) ''Der Totentanz im alemannischen Sprachraum. "Muos ich doch dran - und weis nit wan"''. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg . * Elina Gertsman (2010), The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages. Image, Text, Performance. ''Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages'', 3. Turnhout, Brepols Publishers. *Sophie Oosterwijk (2004),

Of corpses, constables and kings: the Danse Macabre in late-medieval and renaissance culture

, ''The Journal of the British Archaeological Association'', 157, 61–90. * Sophie Oosterwijk (2006),

Muoz ich tanzen und kan nit gân?

Death and the infant in the medieval Danse Macabre', ''Word & Image'', 22:2, 146–64. * Sophie Oosterwijk (2008),

For no man mai fro dethes stroke fle

. Death and Danse Macabre iconography in memorial art', ''Church Monuments'', 23, 62–87, 166-68 * Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knoell (2011),

Mixed Metaphors. The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

'. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. . * Marek Żukow-Karczewski (1989), "Taniec śmierci (Dance macabre"), Życie Literackie (''Literary Life'' - literary review magazine), 43, 4. * Maricarmen Gómez Muntané (2017), ''El Llibre Vermell. Cantos y danzas de fines del Medioevo'', Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica, (chapter "Ad mortem festinamus' y la Danza de la Muerte").

External links

A collection of historical images of the Danse Macabre

at Cornell's ''The Fantastic in Art and Fiction''

The Danse Macabre of Hrastovlje, Slovenia

''Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort: commonly called "The dance of death'

- 1869 photographic reproduction of original by Holbein Society with woodcuts, plus English translations and a biography of Holbein.

Sophie Oosterwijk (2009), '"Fro Paris to Inglond"? The danse macabre in text and image in late-medieval England', Doctoral thesis Leiden University available online.

Images of ''Danse Macabre'' (2001)

Conceptual performance by Antonia Svobodová and Mirek Vodrážka in Čajovna Pod Stromem Čajovým in Prague 22 May 2001'. *

Dance of Death, Chorea, ab eximio Macabro versibus Alemanicis edita et a Petro Desrey ... nuper emendata.

Paris, Gui Marchand, for Geoffroy de Marnef, 15 Oct. (Id. Oct.) 1490. From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the Library of Congress

An introduction to the Dance of Death

Art & Design Library, Central Library, Edinburgh {{DEFAULTSORT:Dance Of Death Visual arts genres Caricature Dance in arts Death customs Fantastic art Horror fiction Iconography Medieval art Medieval drama Memento mori Skulls in art Epidemics in art