Tanystropheus NT small.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tanystropheus'' (Greek ~ 'long' + 'hinged') is an extinct

Vertebrate Palaeontology at Milano University. Retrieved 2007-02-19. In 1886, Francesco Bassani interpreted the unusual fossil as a Well-preserved ''T. longobardicus'' fossils continue to be recovered from Monte San Giorgio up to the present day.

Well-preserved ''T. longobardicus'' fossils continue to be recovered from Monte San Giorgio up to the present day.

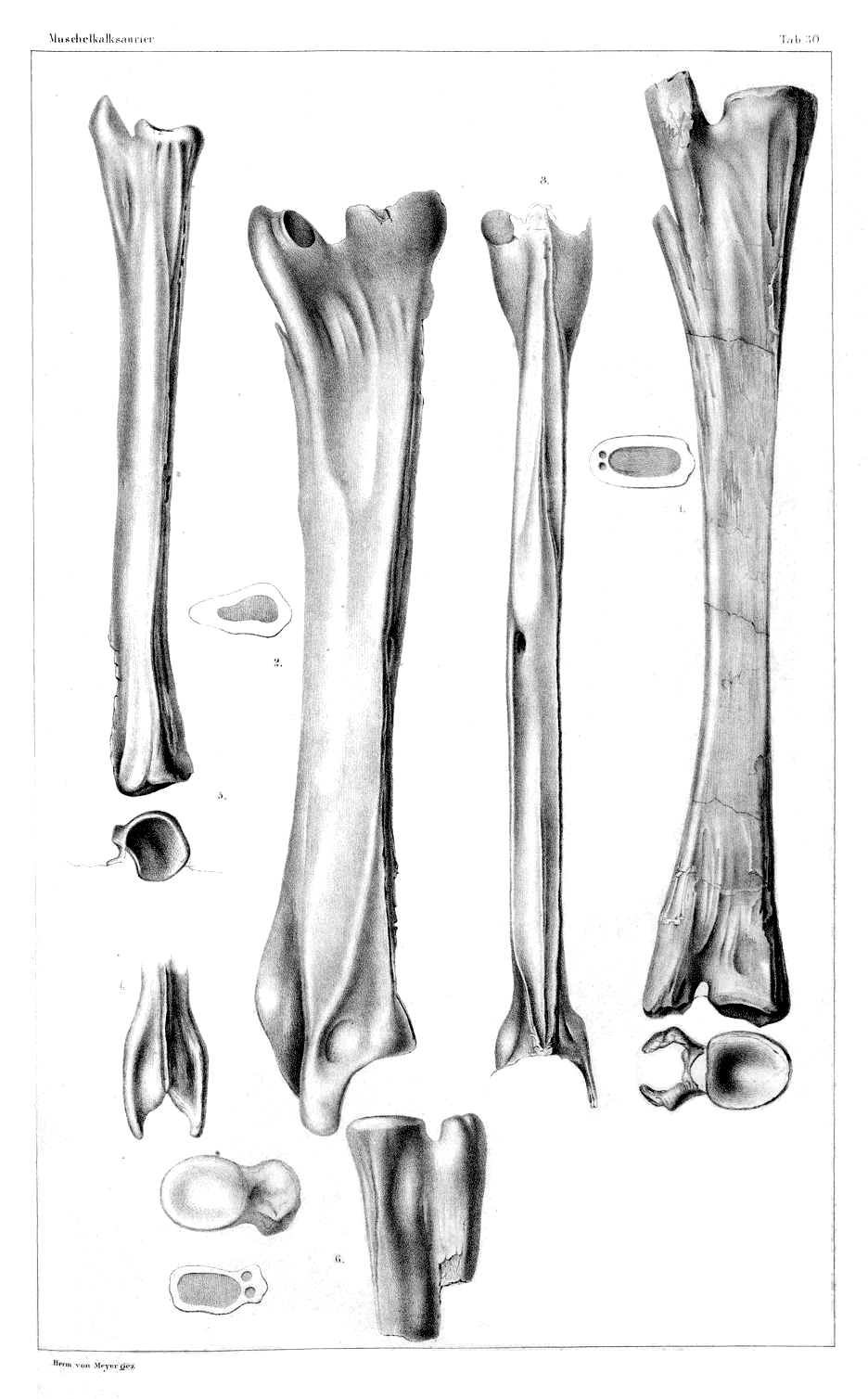

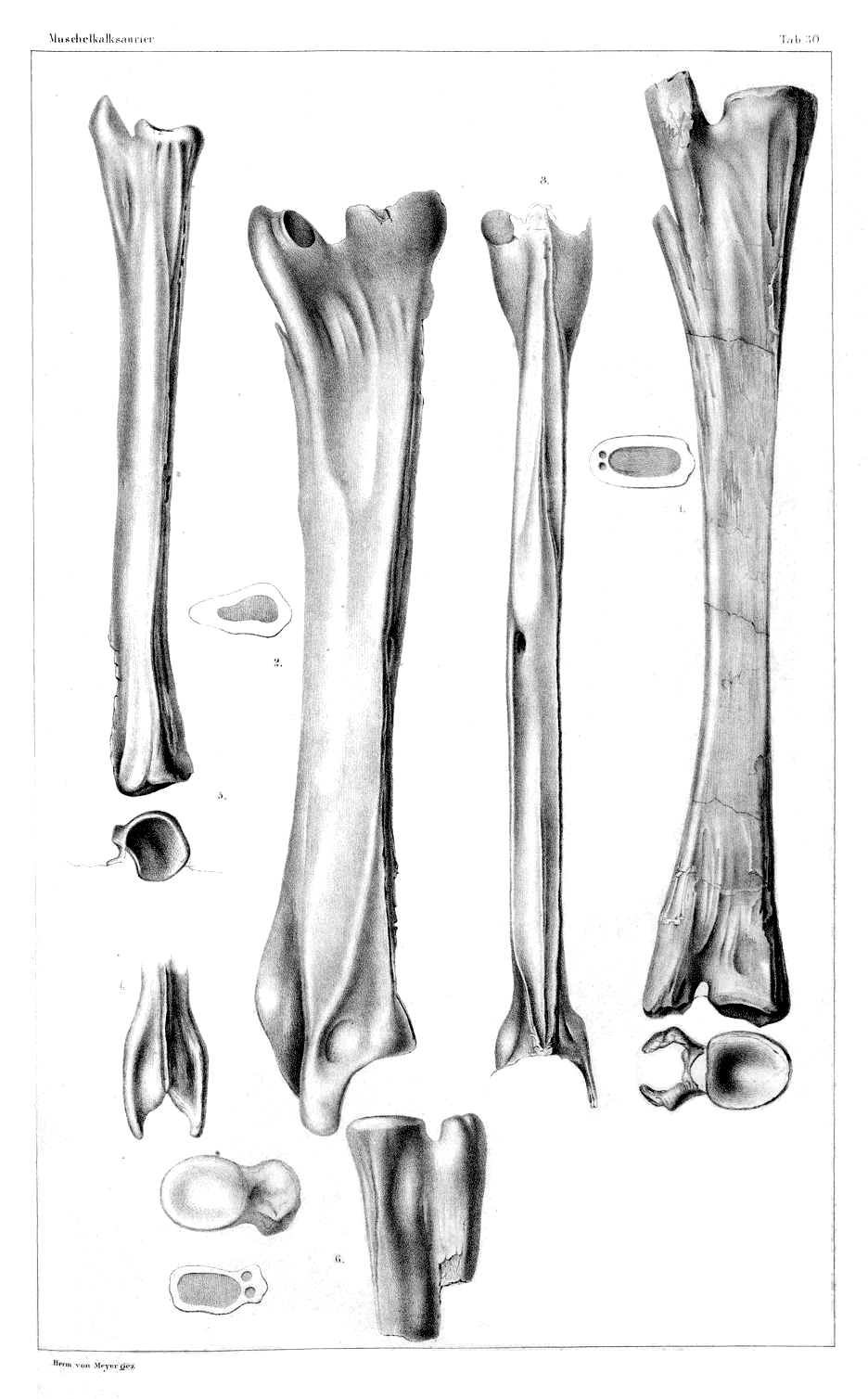

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were several large vertebrae found in the mid-19th century. They were recovered from the Upper

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were several large vertebrae found in the mid-19th century. They were recovered from the Upper

The third to eleventh cervicals are hyperelongate in ''T. longobardicus'' and ''T. hydroides'', ranging from three to 15 times longer than tall. They are somewhat less elongated in ''T. antiquus'', less than 6 times longer than tall. The cervicals gradually increase in size and proportional length, with the ninth cervical typically being the largest vertebra in the skeleton. In general structure, the elongated cervicals resemble the axial pleurocentrum. However, the axis also has a keel on its underside and an incomplete neural canal, unlike its immediate successors. In the rest of the cervicals, all but the front of each neural spine is so low that it is barely noticeable as a thin ridge. The zygapophyses are closely set and tightly connected between vertebrae. The epipophyses develop into hooked spurs. The cervicals are also compressed from the side, so they are taller than wide. Many specimens have a longitudinal lamina (ridge) on the side of each cervical. Ventral keels return to vertebrae in the rear half of the neck. The 12th cervical and its corresponding ribs, though still longer than tall, are notably shorter than their predecessors. The 12th cervical has a prominent neural spine and robust zygapophyses, also unlike its predecessors. The 13th vertebra has long been assumed to be the first dorsal (torso) vertebra. This was justified by its general stout shape and supposedly dichocephalous (two-headed) rib facets, unlike the cervicals. However, specimen GMPKU-P-1527 has shown that the 13th vertebra’s rib simply possessed a single wide articulation and an unconnected forward branch, more similar to the cervical ribs than the dorsal ribs.

All cervicals, except potentially the atlas, connected to holocephalous (single-headed) cervical ribs via facets at their front lower corner. Each cervical rib had a short stalk connecting to two spurs running parallel to their vertebrae. The forward-projecting spurs were short and stubby, while the rear-projecting spurs were extremely narrow and elongated, up to three times longer than their respective vertebrae. This bundle of rod-like bones running along the neck afforded a large degree of rigidity.

The third to eleventh cervicals are hyperelongate in ''T. longobardicus'' and ''T. hydroides'', ranging from three to 15 times longer than tall. They are somewhat less elongated in ''T. antiquus'', less than 6 times longer than tall. The cervicals gradually increase in size and proportional length, with the ninth cervical typically being the largest vertebra in the skeleton. In general structure, the elongated cervicals resemble the axial pleurocentrum. However, the axis also has a keel on its underside and an incomplete neural canal, unlike its immediate successors. In the rest of the cervicals, all but the front of each neural spine is so low that it is barely noticeable as a thin ridge. The zygapophyses are closely set and tightly connected between vertebrae. The epipophyses develop into hooked spurs. The cervicals are also compressed from the side, so they are taller than wide. Many specimens have a longitudinal lamina (ridge) on the side of each cervical. Ventral keels return to vertebrae in the rear half of the neck. The 12th cervical and its corresponding ribs, though still longer than tall, are notably shorter than their predecessors. The 12th cervical has a prominent neural spine and robust zygapophyses, also unlike its predecessors. The 13th vertebra has long been assumed to be the first dorsal (torso) vertebra. This was justified by its general stout shape and supposedly dichocephalous (two-headed) rib facets, unlike the cervicals. However, specimen GMPKU-P-1527 has shown that the 13th vertebra’s rib simply possessed a single wide articulation and an unconnected forward branch, more similar to the cervical ribs than the dorsal ribs.

All cervicals, except potentially the atlas, connected to holocephalous (single-headed) cervical ribs via facets at their front lower corner. Each cervical rib had a short stalk connecting to two spurs running parallel to their vertebrae. The forward-projecting spurs were short and stubby, while the rear-projecting spurs were extremely narrow and elongated, up to three times longer than their respective vertebrae. This bundle of rod-like bones running along the neck afforded a large degree of rigidity.

There are 12 dorsal (torso) vertebrae, which are smaller and less specialised than the cervicals. Though their neural spines are taller than those of the cervicals, they are still usually rather short. The dorsal ribs are double-headed close to the shoulder and single-headed in the rest of the torso, sitting on stout transverse processes in the front half of each vertebra. More than 20 angled rows of

There are 12 dorsal (torso) vertebrae, which are smaller and less specialised than the cervicals. Though their neural spines are taller than those of the cervicals, they are still usually rather short. The dorsal ribs are double-headed close to the shoulder and single-headed in the rest of the torso, sitting on stout transverse processes in the front half of each vertebra. More than 20 angled rows of

The

The

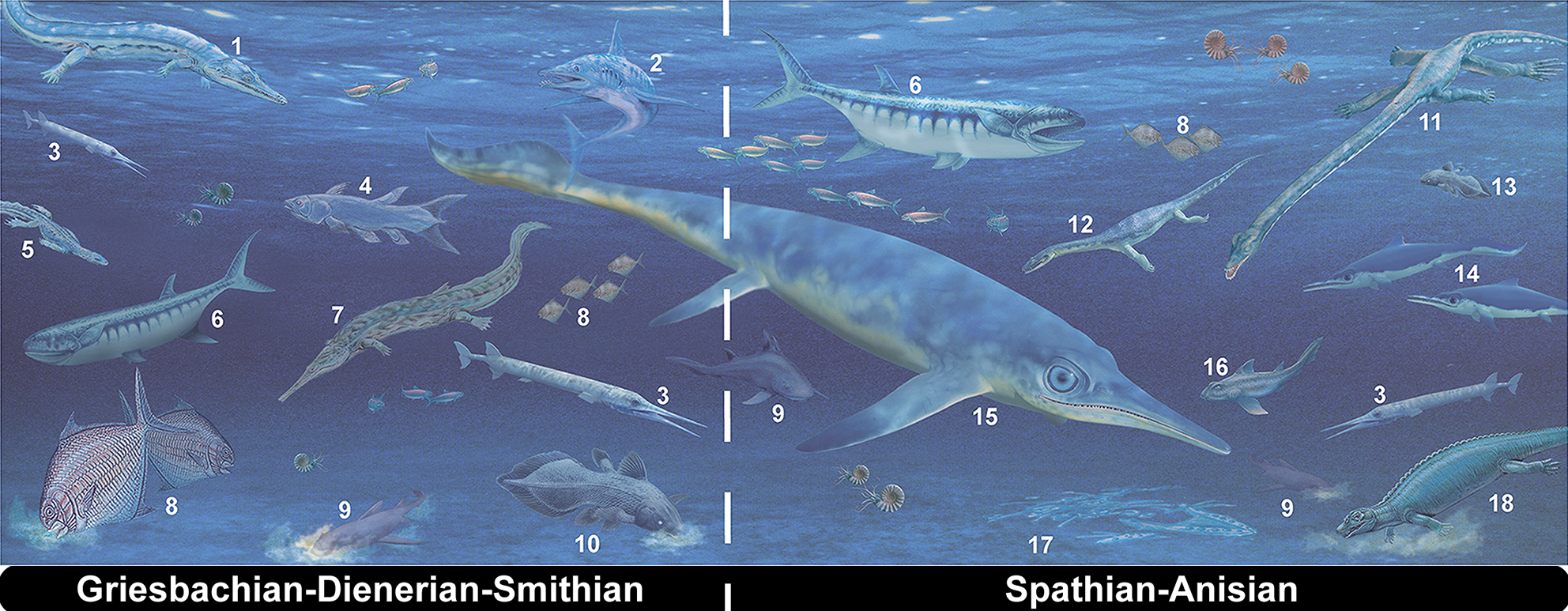

The diet of ''Tanystropheus'' has been controversial in the past, although most recent studies consider it a

The diet of ''Tanystropheus'' has been controversial in the past, although most recent studies consider it a  The most likely function of these teeth, as explained by Nosotti (2007), was that they assisted the piscivorous diet of the reptile by helping to grip slippery prey such as fish or squid. Several modern species of seals, such as the

The most likely function of these teeth, as explained by Nosotti (2007), was that they assisted the piscivorous diet of the reptile by helping to grip slippery prey such as fish or squid. Several modern species of seals, such as the

Major studies on ''Tanystropheus'' anatomy and ecology by

Major studies on ''Tanystropheus'' anatomy and ecology by

In the 1980s, various studies suggested that ''Tanystropheus'' lacked the musculature to raise its neck above the ground, and that it was likely completely aquatic, swimming by undulating its body and tail side-to-side like a snake or crocodile.

Renesto and Saller (2018) argued that the hind limbs would have been quite flexible and powerful according to muscle correlations on the legs, pelvis, and tail vertebrae. They argued that ''Tanystropheus'', despite its apparent lack of adaptations for typical swimming styles, utilised a more unusual mode of underwater movement. Namely, a ''Tanystropheus'' could extend its hind limbs forward and then simultaneously retract them, creating a powerful 'jump' forward. Further support for this hypothesis is based on the

In the 1980s, various studies suggested that ''Tanystropheus'' lacked the musculature to raise its neck above the ground, and that it was likely completely aquatic, swimming by undulating its body and tail side-to-side like a snake or crocodile.

Renesto and Saller (2018) argued that the hind limbs would have been quite flexible and powerful according to muscle correlations on the legs, pelvis, and tail vertebrae. They argued that ''Tanystropheus'', despite its apparent lack of adaptations for typical swimming styles, utilised a more unusual mode of underwater movement. Namely, a ''Tanystropheus'' could extend its hind limbs forward and then simultaneously retract them, creating a powerful 'jump' forward. Further support for this hypothesis is based on the

George Olshevsky expands on the history of "P." ''exogyrarum''

on the Dinosaur Mailing List * Huene, 1902. "Übersicht über die Reptilien der Trias" eview of the Reptilia of the Triassic ''Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen''. 6, 1-84. * Fritsch, 1905. "Synopsis der Saurier der böhm. Kreideformation" ynopsis of the saurians of the Bohemian Cretaceous formation ''Sitzungsberichte der königlich-böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften'', II Classe. 1905(8), 1-7. {{Taxonbar, from=Q131782 Tanystropheids Prehistoric reptile genera Olenekian genus first appearances Anisian genera Ladinian genera Carnian genus extinctions Triassic reptiles of Europe Triassic Italy Fossils of Italy Triassic Switzerland Fossils of Switzerland Fossil taxa described in 1852 Taxa named by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer

archosauromorph

Archosauromorpha ( Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, l ...

reptile from the Middle and Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch of the Triassic Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch and followed by the Early Jurassic Epoch. ...

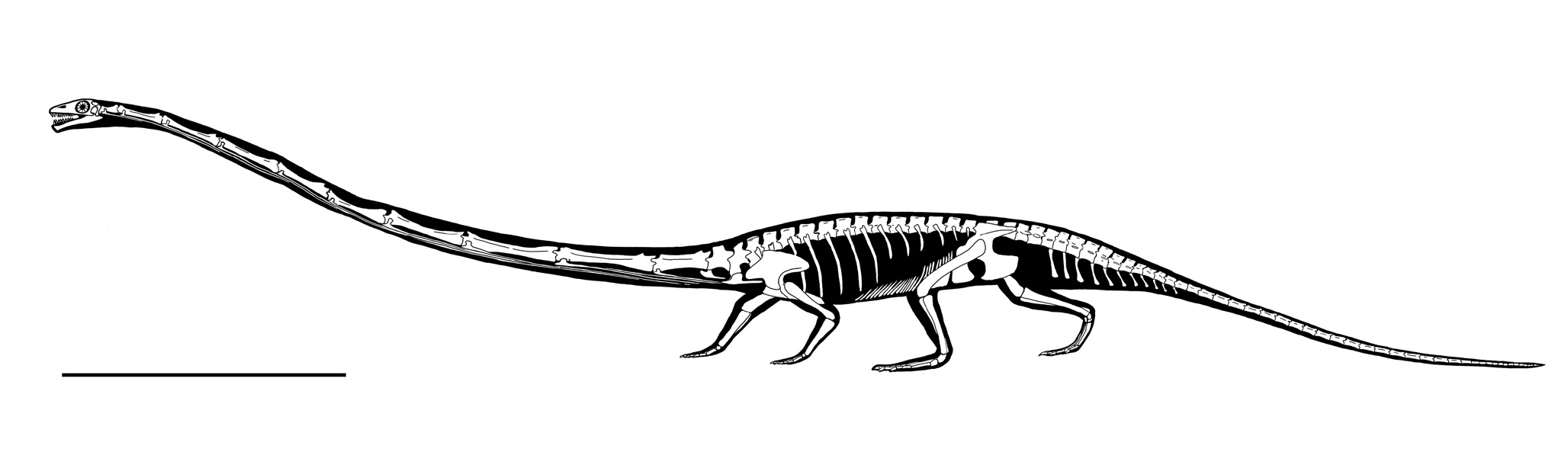

epochs. It is recognisable by its extremely elongated neck, which measured long—longer than its body and tail combined. The neck was composed of 12–13 extremely elongated vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

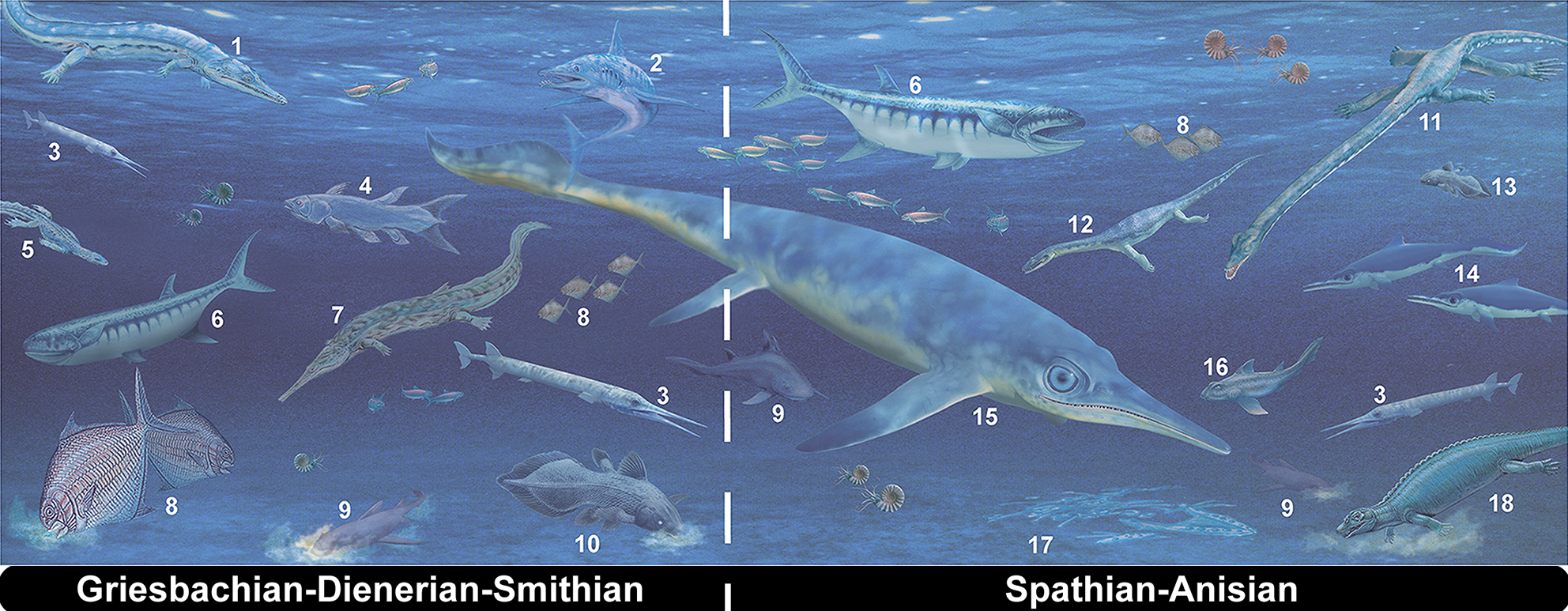

e. With its very long but relatively stiff neck, ''Tanystropheus'' has been often proposed and reconstructed as an aquatic or semi-aquatic reptile, a theory supported by the fact that the creature is most commonly found in semi-aquatic fossil sites wherein known terrestrial reptile remains are scarce. Fossils have been found in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

. Complete skeletons of small individuals are common in the Besano Formation

The Besano Formation is a geological formation in the southern Alps of northwestern Italy and southern Switzerland. This formation, a short but fossiliferous succession of dolomite and black shale, is famous for its preservation of Middle Triassic ...

at Monte San Giorgio

Monte San Giorgio is a mountain and UNESCO World Heritage Site on the border between Switzerland and Italy. It is part of the Lugano Prealps, overlooking Lake Lugano in the Swiss Canton of Ticino.

Monte San Giorgio is a wooded mountain, rising ...

in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Switzerland; other fossils have been found in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

and China, dating from the Middle Triassic to the early part of the Late Triassic (Anisian

In the geologic timescale, the Anisian is the lower stage or earliest age of the Middle Triassic series or epoch and lasted from million years ago until million years ago. The Anisian Age succeeds the Olenekian Age (part of the Lower Triassic ...

, Ladinian

The Ladinian is a stage and age in the Middle Triassic series or epoch. It spans the time between Ma and ~237 Ma (million years ago). The Ladinian was preceded by the Anisian and succeeded by the Carnian (part of the Upper or Late Triassic ...

, and Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227 m ...

stages).Dal Sasso, C. and Brillante, G. (2005). ''Dinosaurs of Italy''. Indiana University Press. , .

History

Monte San Giorgio specimens

19th century excavations atMonte San Giorgio

Monte San Giorgio is a mountain and UNESCO World Heritage Site on the border between Switzerland and Italy. It is part of the Lugano Prealps, overlooking Lake Lugano in the Swiss Canton of Ticino.

Monte San Giorgio is a wooded mountain, rising ...

, on the Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

- Switzerland border, revealed a fragmentary fossil of an animal with three-cusped teeth and elongated bones. Monte San Giorgio preserves the Besano Formation

The Besano Formation is a geological formation in the southern Alps of northwestern Italy and southern Switzerland. This formation, a short but fossiliferous succession of dolomite and black shale, is famous for its preservation of Middle Triassic ...

(also known as the Grenzbitumenzone), a Anisian

In the geologic timescale, the Anisian is the lower stage or earliest age of the Middle Triassic series or epoch and lasted from million years ago until million years ago. The Anisian Age succeeds the Olenekian Age (part of the Lower Triassic ...

-Ladinian

The Ladinian is a stage and age in the Middle Triassic series or epoch. It spans the time between Ma and ~237 Ma (million years ago). The Ladinian was preceded by the Anisian and succeeded by the Carnian (part of the Upper or Late Triassic ...

formation recognised for its spectacular fossils.''Tanystropheus''Vertebrate Palaeontology at Milano University. Retrieved 2007-02-19. In 1886, Francesco Bassani interpreted the unusual fossil as a

pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

, which he named ''Tribelesodon longobardicus''. It would take more than 40 years for this misconception to be resolved. Though this holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

specimen of ''Tribelesodon longobardicus'' was destroyed in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, excavations by Bernhard Peyer Bernhard Peyer (25 July 1885 – 23 February 1963) was a Swiss paleontologist and anatomist who served as a professor at the University of Zurich. A major contribution was on the evolution of vertebrate teeth.

Peyer was born in Schaffhausen, Switze ...

in the late 1920s and 1930s revealed many other complete specimens from Monte San Giorgio.

Peyer's discoveries allowed ''Tribelesodon longobardicus'' to be recognised as a non-flying reptile, with its supposed elongated finger bones recognized as neck vertebrae. These vertebrae were compared favorable with those previously described as ''Tanystropheus'' from Germany and Poland. Thus, ''Tribelesodon longobardicus'' was renamed to ''Tanystropheus longobardicus'' and its anatomy was revised into a long-necked, non-pterosaur reptile. Specimen PIMUZ T 2791, which was discovered in 1929, has been designated as the neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes the ...

of the species.Rupert Wild

Rupert may refer to:

People

* Rupert (name), various people known by the given name or surname "Rupert"

Places Canada

*Rupert, Quebec, a village

* Rupert Bay, a large bay located on the south-east shore of James Bay

*Rupert River, Quebec

* Ruper ...

reviewed and redescribed all specimens known at the time via several large monographs in 1973/4 and 1980. In 2005, Dr. Silvio Renesto described a ''T. longobardicus'' specimen from Switzerland which preserved the impressions of skin and other soft tissue. Five new specimens of ''T. longobardicus'' were described by Stefania Nosotti in 2007, allowing for a more comprehensive view of the anatomy of the species.

A small but well-preserved skull and neck, specimen PIMUZ T 3901, was found in the slightly younger Meride Limestone

Meride is a village and former municipality in the district of Mendrisio in the canton of Ticino in Switzerland. On 14 April 2013 the former municipalities of Besazio, Ligornetto and Meride merged into the municipality of Mendrisio.

at Monte San Giorgio. It was given a new species, ''T. meridensis'', in 1980. The specimen was later referred to ''T. longobardicus'', rendering ''T. meridensis'' a junior synonym of that species. A 2019 revision of ''Tanystropheus'' found that ''T. longobardicus'' and ''T. antiquus'' were the only valid species in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

. In 2020, large ''Tanystropheus'' specimens from Monte San Giorgio originally assigned to ''T. longobardicus'' were given a new species, ''T. hydroides''.

Other specimens

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were several large vertebrae found in the mid-19th century. They were recovered from the Upper

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were several large vertebrae found in the mid-19th century. They were recovered from the Upper Muschelkalk

The Muschelkalk (German for "shell-bearing limestone"; french: calcaire coquillier) is a sequence of sedimentary rock, sedimentary rock strata (a lithostratigraphy, lithostratigraphic unit) in the geology of central and western Europe. It has a Mid ...

of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Lower Keuper of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. Though initially given the name ''Macroscelosaurus'' by Count Georg Zu Münster, the publication containing this name is lost and its genus is considered a '' nomen oblitum''. In 1855, Hermann von Meyer

Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer (3 September 1801 – 2 April 1869), known as Hermann von Meyer, was a German palaeontologist. He was awarded the 1858 Wollaston medal by the Geological Society of London.

Life

He was born at Frankfurt am Ma ...

supplied the name ''Tanystropheus conspicuus'', the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specime ...

of ''Tanystropheus'', to the fossils. They were later regarded as ''Tanystropheus'' fossils undiagnostic relative to other species, rendering ''T. conspicuus'' a '' nomen dubium'' possibly synonymous with ''T. hydroides''. In the 1880s, E.D. Cope named three supposed new ''Tanystropheus'' species from the southwest United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. However, these fossils were later determined to belong to theropod dinosaurs, which were given the new genus ''Coelophysis

''Coelophysis'' ( traditionally; or , as heard more commonly in recent decades) is an extinct genus of coelophysid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 228 to 201.3 million years ago during the latter part of the Triassic Period fro ...

''.

In the 1900s, Friedrich von Huene named several ''Tanystropheus'' species from Germany and Poland. ''T. posthumus'', from the Norian of Germany, was later considered an indeterminate theropod vertebra and a ''nomen dubium''. ''T. antiquus'', from the Gogolin Formation of Poland, was based on cervical vertebrae which were proportionally shorter than those of other ''Tanystropheus'' species. Long considered destroyed in World War II, several ''T. antiquus'' fossils were rediscovered in the late 2010s. ''T. antiquus'' is currently considered one of the few valid species of ''Tanystropheus.'' As the Gogolin Formation is upper Olenekian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age in the Early Triassic epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage in the Lower Triassic series. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). The Olenekian is sometimes divided i ...

to lower Anisian in age, ''T. antiquus'' fossils are likely the oldest in the genus. Specimens likely referable to ''T. antiquus'' are also known from Germany and The Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. Several more von Huene species, including "''Procerosaurus cruralis''", "''Thecodontosaurus

''Thecodontosaurus'' ("socket-tooth lizard") is a genus of herbivorous basal sauropodomorph dinosaur that lived during the late Triassic period ( Rhaetian age).

Its remains are known mostly from Triassic "fissure fillings" in South England. ''Th ...

latespinatus''", and "''Thecodontosaurus primus''", have been reconsidered as indeterminate material of ''Tanystropheus'' or other archosauromorphs

Archosauromorpha (Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, liz ...

.

''Tanystropheus'' specimens from the Makhtesh Ramon in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

were described as a new species, ''T. haasi'', in 2001. However, this species may be dubious due to the difficulty of distinguishing its vertebrae from ''T. conspicuus'' or ''T. longobardicus''. Another new species, ''T. biharicus'', was described from Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

in 1975. It has also been considered possibly synonymous with ''T. longobardicus''. The most complete ''Tanystropheus'' fossils outside of Monte San Giorgio come from the Guizhou

Guizhou (; formerly Kweichow) is a landlocked province in the southwest region of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Guiyang, in the center of the province. Guizhou borders the autonomous region of Guangxi to the ...

province of China, as described by Li (2007) and Rieppel (2010). They are also the youngest and easternmost fossils in the genus, hailing from the upper Ladinian or lower Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227 m ...

Zhuganpo Formation

The Zhuganpo Formation is a Triassic geologic unit found in southern China. It has historically been known as the Zhuganpo Member of the Falang Formation. A diverse fossil assemblage known as the Xingyi biota or Xingyi Fauna can be found in the up ...

. They include a large morphotype (''T. hydroides'') specimen, GMPKU-P-1527, and an indeterminate juvenile skeleton, IVPP V 14472. In 2015, a large ''Tanystropheus'' cervical vertebra was described from the Anisian to Carnian Economy Member of the Wolfville Formation, in the Bay of Fundy of Nova Scotia, Canada

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. Indeterminate ''Tanystropheus'' remains are also known from the Jilh Formation of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

and various Anisian-Ladinian sites in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

?, Italy, and Switzerland. One of the youngest ''Tanystropheus'' fossils is a vertebra from the lower Carnian Fusea site in Friuli, Italy.

Several new tanystropheid genera have been named from former ''Tanystropheus'' fossils. In 2006, possible ''Tanystropheus'' material from the Anisian Röt Formation in Germany was named as '' Amotosaurus''. In 2011, fossils from the Lipovskaya Formation of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

were given the genus '' Augustaburiana'' by A.G. Sennikov. He also named the new genus '' Protanystropheus'' for ''T. antiquus,'' but other authors continue to keep that species within ''Tanystropheus''. ''Tanystropheus fossai,'' from the Norian-age Argillite di Riva di Solto in Italy, was given its own genus ''Sclerostropheus

''Sclerostropheus'' is an extinct genus of tanystropheid archosauromorph from the Late Triassic of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in ...

'' in 2019.

Anatomy

Neck

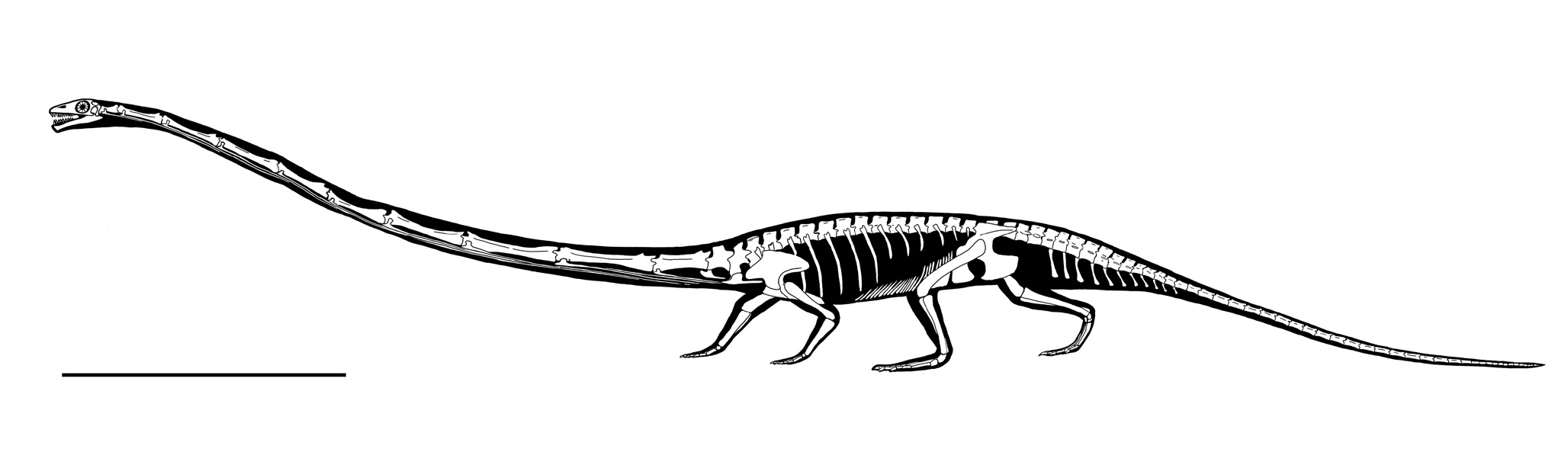

By far the most recognisable feature of ''Tanystropheus'' is its hyperelongate neck, equivalent to the combined length of the body and tail. ''Tanystropheus'' had 13 massive cervical (neck) vertebrae, though the first two were smaller and less strongly developed. Theatlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geograp ...

(first cervical), which connects to the skull, is a small, four-part bone complex. It consists of an atlantal intercentrum (small lower component) and pleurocentrum (large lower component), and a pair of atlantal neural arches (prong-like upper components). There does not appear to be a proatlas, which slots between the atlas and skull in some other reptiles. The intercentrum and pleurocentrum are not fused to each other, unlike the fused atlas of allokotosaurs. The tiny crescent-shaped intercentrum is overlain by a semicircular pleurocentrum, which acts as a base to the backswept neural arches. The axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

(second cervical) is larger, with a small axial intercentrum followed by a much larger axial pleurocentrum. The axial pleurocentrum is longer than tall, has a low neural spine

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic ...

set forwards, and small prezygapophyses (front articular plates). The large postzygophyses (rear articular plates) are separated by a broad trough and support pointed epipophyses (additional projections). The third to eleventh cervicals are hyperelongate in ''T. longobardicus'' and ''T. hydroides'', ranging from three to 15 times longer than tall. They are somewhat less elongated in ''T. antiquus'', less than 6 times longer than tall. The cervicals gradually increase in size and proportional length, with the ninth cervical typically being the largest vertebra in the skeleton. In general structure, the elongated cervicals resemble the axial pleurocentrum. However, the axis also has a keel on its underside and an incomplete neural canal, unlike its immediate successors. In the rest of the cervicals, all but the front of each neural spine is so low that it is barely noticeable as a thin ridge. The zygapophyses are closely set and tightly connected between vertebrae. The epipophyses develop into hooked spurs. The cervicals are also compressed from the side, so they are taller than wide. Many specimens have a longitudinal lamina (ridge) on the side of each cervical. Ventral keels return to vertebrae in the rear half of the neck. The 12th cervical and its corresponding ribs, though still longer than tall, are notably shorter than their predecessors. The 12th cervical has a prominent neural spine and robust zygapophyses, also unlike its predecessors. The 13th vertebra has long been assumed to be the first dorsal (torso) vertebra. This was justified by its general stout shape and supposedly dichocephalous (two-headed) rib facets, unlike the cervicals. However, specimen GMPKU-P-1527 has shown that the 13th vertebra’s rib simply possessed a single wide articulation and an unconnected forward branch, more similar to the cervical ribs than the dorsal ribs.

All cervicals, except potentially the atlas, connected to holocephalous (single-headed) cervical ribs via facets at their front lower corner. Each cervical rib had a short stalk connecting to two spurs running parallel to their vertebrae. The forward-projecting spurs were short and stubby, while the rear-projecting spurs were extremely narrow and elongated, up to three times longer than their respective vertebrae. This bundle of rod-like bones running along the neck afforded a large degree of rigidity.

The third to eleventh cervicals are hyperelongate in ''T. longobardicus'' and ''T. hydroides'', ranging from three to 15 times longer than tall. They are somewhat less elongated in ''T. antiquus'', less than 6 times longer than tall. The cervicals gradually increase in size and proportional length, with the ninth cervical typically being the largest vertebra in the skeleton. In general structure, the elongated cervicals resemble the axial pleurocentrum. However, the axis also has a keel on its underside and an incomplete neural canal, unlike its immediate successors. In the rest of the cervicals, all but the front of each neural spine is so low that it is barely noticeable as a thin ridge. The zygapophyses are closely set and tightly connected between vertebrae. The epipophyses develop into hooked spurs. The cervicals are also compressed from the side, so they are taller than wide. Many specimens have a longitudinal lamina (ridge) on the side of each cervical. Ventral keels return to vertebrae in the rear half of the neck. The 12th cervical and its corresponding ribs, though still longer than tall, are notably shorter than their predecessors. The 12th cervical has a prominent neural spine and robust zygapophyses, also unlike its predecessors. The 13th vertebra has long been assumed to be the first dorsal (torso) vertebra. This was justified by its general stout shape and supposedly dichocephalous (two-headed) rib facets, unlike the cervicals. However, specimen GMPKU-P-1527 has shown that the 13th vertebra’s rib simply possessed a single wide articulation and an unconnected forward branch, more similar to the cervical ribs than the dorsal ribs.

All cervicals, except potentially the atlas, connected to holocephalous (single-headed) cervical ribs via facets at their front lower corner. Each cervical rib had a short stalk connecting to two spurs running parallel to their vertebrae. The forward-projecting spurs were short and stubby, while the rear-projecting spurs were extremely narrow and elongated, up to three times longer than their respective vertebrae. This bundle of rod-like bones running along the neck afforded a large degree of rigidity.

Other vertebrae

gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In thes ...

extend along the belly, each gastral element represented by a pair of segmented rods which intermingle at the midline.

The two sacral (hip) vertebrae are low but robust, bridging over to the hip with expanded sacral ribs. The latter sacral rib is a single unit without a bifurcated structure. The tail is long, with at least 30 and possible up to 50 caudal vertebrae. The first few caudals are large, with closely interlinked zygapophyses and widely projecting pleurapophyses (transverse processes without ribs). The length of the pleurapophyses decreases until they disappear between the eighth and thirteenth caudal. The height of the neural spines also decreases gradually down the tail. Two pairs of large, curved bones, known as heterotopic ossifications, sit behind the hips in about half of known specimens preserving the area. These bones are possibly sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, and have also been reported in '' Tanytrachelos''. They may be linked to reproductive biology, supporting reproductive organs (if they belong to males) or an egg pouch (if they belong to females). A row of long chevrons is present under a short portion of the tail, behind the heterotopic bones or the space they would have occupied.

Pectoral girdle and forelimbs

The

The clavicle

The clavicle, or collarbone, is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on the left and one on the r ...

s have a fairly standard form, as curved and slightly twisted rods. They lie on the interclavicle

An interclavicle is a bone which, in most tetrapods, is located between the clavicles. Therian mammals (marsupials and placentals) are the only tetrapods which never have an interclavicle, although some members of other groups also lack one. In t ...

, a bone which has a rhombic (broad, diamond-shaped) front part followed by a long stalk. The interclavicle is rarely preserved and its connections to the rest of the pectoral (shoulder) girdle are mostly inferred from ''Macrocnemus''. The scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

has the form of a large semicircular plate on a short, broad stalk, similar to other tanystropheids. The coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek κόραξ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

is a large oval-shaped plate with a broad glenoid facet (shoulder socket).

The humerus is straight and slightly constricted at the middle. Near the elbow it is expanded and twisted, with ectepicondylar groove on its outer edge. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

is slender and somewhat curved, while the ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

is similar in shape to the humerus and lacks a distinct olecranon

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony eminence of the ulna, a long bone in the forearm that projects behind the elbow. It forms the most pointed portion of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit. The olecranon ...

. There are four carpals

The carpal bones are the eight small bones that make up the wrist (or carpus) that connects the hand to the forearm. The term "carpus" is derived from the Latin carpus and the Greek καρπός (karpós), meaning "wrist". In human anatomy, th ...

(wrist bones): the ulnare, radiale

''Radiale'' is the fifth studio album by Italian band Zu, in collaboration with Spaceways Inc., released in 2004.http://www.sentireascoltare.com/recensione/4741/zu-radiale.html

The album received an A grade from The Village Voice and was pl ...

, and two distal carpals. The ulnare and radiale are large and cuboid, enclosing a small foramen between them. The larger outer distal carpal connects to metacarpals

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpal bones ar ...

III and IV, while the much smaller inner one connects to metacarpals II and III. Metacarpals III and IV are the largest bones in the hand, followed closely by metacarpal II. Metacarpals I and V are both short. The hand’s phalangeal formula (joints per finger) is 2-3-4-4-3. The terminal phalanges (fingertips) would have formed thick, blunt claws.

Hip and hindlimbs

The components of the pelvis (hip) are proportionally small, though their shape is fairly standard for tanystropheids. The ilium is low and extends to a tapered point at the rear. The pubis is vertically oriented, with a small but distinctobturator foramen

The obturator foramen (Latin foramen obturatum) is the large opening created by the ischium and pubis bones of the pelvis through which nerves and blood vessels pass.

Structure

It is bounded by a thin, uneven margin, to which a strong membran ...

and a concave rear edge. The lower edge of the large, fan-shaped ischium converges towards (but does not contact) the pubis, nearly encompassing a large gap known as the thyroid foramen.

The hindlimbs are significantly larger than the forelimbs, though similar in overall structure and proportions. The femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

is long, slender, and sigmoid (curved at both ends). It has a longitudinal muscle scar (the internal trochanter) on its underside and a broad joint at the acetabulum (hip socket). The tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

and fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity i ...

are straight, with the former much thicker and expanded at the knee. The large proximal tarsals (ankle bones) include a rounded calcaneum

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is the point of the hock.

...

and a blocky astragalus

''Astragalus'' is a large genus of over 3,000 species of herbs and small shrubs, belonging to the legume family Fabaceae and the subfamily Faboideae. It is the largest genus of plants in terms of described species. The genus is native to tempe ...

, which meet along a straight or shallowly indented contact in most specimens. Unlike most early archosauromorphs, ''Tanystropheus'' has only two pebble-like distal tarsals: the larger fourth distal tarsal and minuscule third distal tarsal. There are five closely-appressed metatarsals

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the me ...

, with the fourth and third being the longest. Though the first four metatarsals are slender and similar in length, the fifth (outermost) is very stout and subtly hooked, slotting into the ankle along a smooth joint. The estimated phalangeal formula is 2-3-4-5-4, and first phalange of the fifth toe was very long, filling a metatarsal-like role as seen in other tanystropheids.

Paleoecology

Diet

piscivorous

A piscivore () is a carnivorous animal that eats primarily fish. The name ''piscivore'' is derived . Piscivore is equivalent to the Greek-derived word ichthyophage, both of which mean "fish eater". Fish were the diet of early tetrapod evoluti ...

(fish-eating) reptile. The teeth at the front of the narrow snout were long, conical, and interlocking, similar to those of nothosaur

Nothosaurs (order Nothosauroidea) were Triassic marine sauropterygian reptiles that may have lived like seals of today, catching food in water but coming ashore on rocks and beaches. They averaged about in length, with a long body and tail.F. ...

s and plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared i ...

. This was likely an adaptation for catching aquatic prey. Additionally, hooklets from cephalopod tentacles and what may be fish scales have been found near the belly regions of some specimens, further support for a piscivorous lifestyle.

However, small specimens of the genus possess an additional, more unusual form of teeth. This form of teeth, which occurred in the rear part of the jaws behind the interlocking front teeth, were tricuspid (three-pronged), with a long and pointed central cusp

A cusp is the most pointed end of a curve. It often refers to cusp (anatomy), a pointed structure on a tooth.

Cusp or CUSP may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Cusp (singularity), a singular point of a curve

* Cusp catastrophe, a branch of bifurc ...

and smaller cusps in front of and behind the central cusp. Wild (1974) considered these three-cusped teeth to be an adaptation for gripping insects. Cox (1985) noted that marine iguana

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine rept ...

s also had three-cusped teeth, and that ''Tanystropheus'' likely fed on marine algae like that species of lizard. Taylor (1989) rejected both of these hypotheses, as he considered the neck of ''Tanystropheus'' to be too inflexible for the animal to be successful at either diet. The most likely function of these teeth, as explained by Nosotti (2007), was that they assisted the piscivorous diet of the reptile by helping to grip slippery prey such as fish or squid. Several modern species of seals, such as the

The most likely function of these teeth, as explained by Nosotti (2007), was that they assisted the piscivorous diet of the reptile by helping to grip slippery prey such as fish or squid. Several modern species of seals, such as the hooded seal

The hooded seal (''Cystophora cristata'') is a large phocid found only in the central and western North Atlantic, ranging from Svalbard in the east to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the west. The seals are typically silver-grey or white in color, w ...

and crabeater seal

The crabeater seal (''Lobodon carcinophaga''), also known as the krill-eater seal, is a true seal with a circumpolar distribution around the coast of Antarctica. They are medium- to large-sized (over 2 m in length), relatively slender and pale-c ...

, also have multi-cusped teeth which assist their diet to a similar effect. Similar teeth patterns have also been found in the pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

''Eudimorphodon

''Eudimorphodon'' was a pterosaur that was discovered in 1973 by Mario Pandolfi in the town of Cene, Italy and described the same year by Rocco Zambelli. The nearly complete skeleton was retrieved from shale deposited during the Late Triassic (m ...

'' and the fellow tanystropheid '' Langobardisaurus'', both of whom are considered piscivores. Large individuals of ''Tanystropheus'', over in length, lack these three-cusped teeth, instead possessing typical conical teeth at the back of the mouth. They also lack teeth on the pterygoid Pterygoid, from the Greek for 'winglike', may refer to:

* Pterygoid bone, a bone of the palate of many vertebrates

* Pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone

** Lateral pterygoid plate

** Medial pterygoid plate

* Lateral pterygoid muscle

* Medi ...

and palatine

A palatine or palatinus (in Latin; plural ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times.

bones on the roof of the mouth, which possess teeth in smaller specimens. The two morphotypes were originally considered to represent juvenile and adult specimens of ''T. longobardicus''. However, histology

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vi ...

of the small specimens and restudy of the large specimens has shown that they each represent adult forms of two different species. The larger one-cusped morphotype was given a new species, ''T. hydroides'', while the smaller tricuspid morphotype retained the name ''T. longobardicus''.

Soft tissue

The specimen described by Renesto in 2005 displayed an unusual "black material" around the rear part of the body, with smaller patches in the middle of the back and tail. Although most of the material could not have its structure determined, the portion just in front of the hip seemingly preserved scale impressions, indicating that the black material was the remnants of soft tissue. The scales seem to be semi-rectangular and do not overlap with each other, similar to the integument reported in a juvenile '' Macrocnemus'' described in 2002. The portion of the material at the base of the tail is particularly thick and rich inphosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phosph ...

. Many small spherical structures are also present in this portion, which upon further preparation were revealed to be composed of calcium carbonate. These chemicals suggest that the black material was formed as a product of the specimen's proteins decaying in a warm, stagnant, and acidic environment. As in ''Macrocnemus'', the concentration of this material at the base of the tail suggests that the specimen had a quite noticeable amount of muscle behind its hips.

Lifestyle

The lifestyle of ''Tanystropheus'' is controversial, with different studies favoring a terrestrial or aquatic lifestyle for the animal.Terrestrial habits and locomotion

Major studies on ''Tanystropheus'' anatomy and ecology by

Major studies on ''Tanystropheus'' anatomy and ecology by Rupert Wild

Rupert may refer to:

People

* Rupert (name), various people known by the given name or surname "Rupert"

Places Canada

*Rupert, Quebec, a village

* Rupert Bay, a large bay located on the south-east shore of James Bay

*Rupert River, Quebec

* Ruper ...

in the 1970s argued that it was an active terrestrial predator, keeping its head held high with an S-shaped flexion.Wild, R. 1973. Tanystropheus longbardicus (Bassani) (Neue Egerbnisse). in Kuhn-Schnyder, E., Peyer, B. (eds) — Triasfauna der Tessiner Kalkalpen XXIII. Schweiz. Paleont. Abh. Vol. 95 Basel, Germany. Though this interpretation is not wholly consistent with its proposed biomechanics, more recent studies have found some support for land-based movement in ''Tanystropheus''.

Renesto (2005) argued that ''Tanystropheus'' lacked clear adaptations for underwater swimming. The tail of ''Tanystropheus'' was compressed vertically (from top-to-bottom) at the base and thinned towards the tip, so that it would have been useless for lateral (side-to-side) movement. The long neck and short front limbs compared to the long hind limbs would have made four-limbed swimming inefficient and unstable if that was the preferred form of locomotion. Thrusting with only the hind limbs, as in swimming frogs, was also considered an inefficient form of locomotion for a large animal such as ''Tanystropheus,'' although a later study found support for this hypothesis.

Renesto's study also found that the neck was lighter than previously suggested, and that the entire front half of the body was more lightly-built than the rear half, which would have possessed a large amount of muscle mass. In addition to strengthening the hind limbs, the large hip and tail muscles would have shifted the animal's center of mass rearwards, stabilizing the animal as it maneuvered its elongated neck. Weak development of cervical spines suggest that epaxial musculature was underdeveloped in ''Tanystropheus'', and that intrinsic back muscles (e.g., ''m. longus cervicis'') were the driving force behind neck movement. The horizontal overlap between zygapophyses would have limited lateral movement of the neck, while cervical ribs would have formed a brace along the underside of the neck. The long cervical ribs may have played a similar role to ossified tendons of many large dinosaurs, transmitting the forces from the weight of head and neck down to the pectoral girdle, as well as providing passive support by limiting dorsoventral flexion.Tschanz, K. 1988. Allometry and Heterochrony in the Growth of the Neck of Triassic Prolacertiform Reptiles. Paleontology. 31:997–1011.

Renesto's conclusions were the basis for later investigations of the genus. In 2015, paleoartist Mark Witton estimated that the neck made up only 20% of the entire animal's mass due to its light and hollow vertebrae. By comparison, the heads and necks of pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

s of the family Azhdarchidae made up almost 50% of the animal's mass, yet they were clearly land based carnivores. The animal was also poorly equipped for aquatic life, with the only adaptation being a lengthened fifth toe, which suggests that it visited the water some of the time, though was not wholly dependent on it. Witton proposed that ''Tanystropheus'' would have hunted prey from the seashore, akin to a heron. Terrestrial or semi-terrestrial habits are supported by taphonomic evidence, which indicates that the preservation of ''Tanystropheus'' specimens is more similar to the terrestrial '' Macrocnemus'' than the aquatic ''Serpianosaurus

''Serpianosaurus'' is an extinct genus of pachypleurosaurs known from the Middle Triassic (late Anisian and early Ladinian stages) deposits of Switzerland and Germany. It was a small reptile, with the type specimen of ''S. mirigiolensis'' meas ...

'' where all three co-occur. Renesto and Franco Saller's 2018 follow-up to Renesto (2005)'s study offered more information on the reconstructed musculature of ''Tanystropheus''. This study determined that the first few tail vertebrae of ''Tanystropheus'' would have housed powerful tendons and ligaments that would have made the body more stiff, keeping the belly off the ground and preventing the neck from pulling the body over.

Aquatic habits and locomotion

In the 1980s, various studies suggested that ''Tanystropheus'' lacked the musculature to raise its neck above the ground, and that it was likely completely aquatic, swimming by undulating its body and tail side-to-side like a snake or crocodile.

Renesto and Saller (2018) argued that the hind limbs would have been quite flexible and powerful according to muscle correlations on the legs, pelvis, and tail vertebrae. They argued that ''Tanystropheus'', despite its apparent lack of adaptations for typical swimming styles, utilised a more unusual mode of underwater movement. Namely, a ''Tanystropheus'' could extend its hind limbs forward and then simultaneously retract them, creating a powerful 'jump' forward. Further support for this hypothesis is based on the

In the 1980s, various studies suggested that ''Tanystropheus'' lacked the musculature to raise its neck above the ground, and that it was likely completely aquatic, swimming by undulating its body and tail side-to-side like a snake or crocodile.

Renesto and Saller (2018) argued that the hind limbs would have been quite flexible and powerful according to muscle correlations on the legs, pelvis, and tail vertebrae. They argued that ''Tanystropheus'', despite its apparent lack of adaptations for typical swimming styles, utilised a more unusual mode of underwater movement. Namely, a ''Tanystropheus'' could extend its hind limbs forward and then simultaneously retract them, creating a powerful 'jump' forward. Further support for this hypothesis is based on the ichnogenus

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxa'' comes from the Greek ίχνος, ''ichnos'' meaning ''track'' and ταξις, ''taxis'' meaning ...

(trackway fossil) '' Gwyneddichnium'', which was likely created by small tanystropheids such as '' Tanytrachelos''. Some ''Gwyneddichnium'' tracks seem to represent a succession of paired footprints that can be assigned to the hind limbs, without any hand prints. These tracks were almost certainly created by the same form of movement which Renesto and Saller hypothesised was the preferred form of swimming in ''Tanystropheus''.

Under their hypothesis, the most likely lifestyle for ''Tanystropheus'' was that the animal was a shallow-water predator which used its long neck to stealthily approach schools of fish or squid without disturbing its prey due to its large body size. Upon selecting a suitable prey item, it would have dashed forward by propelling itself along the seabed or through the water, with both hind limbs pushing off at the same time. However, this style of swimming is most common in amphibious creatures such as frogs, and likewise ''Tanystropheus'' would also have been capable of walking around on land. The proposal that ''Tanystropheus'' evolved this form of swimming over much more efficient and specialised styles is evidence that it did not live an exclusively aquatic life, in contrast to longer-lasting marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs or plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared i ...

.

A 2020 digital reconstruction of ''Tanystropheus'' skulls suggested that members of the genus, especially ''Tanystropheus hydroides'', were semiaquatic because of the position of the nostrils. And the poor hydrodynamic profile and limited adaptions to swimming in the limbs suggested it lived in shallow coastal areas even in freshwater.

References

Bibliography

George Olshevsky expands on the history of "P." ''exogyrarum''

on the Dinosaur Mailing List * Huene, 1902. "Übersicht über die Reptilien der Trias" eview of the Reptilia of the Triassic ''Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen''. 6, 1-84. * Fritsch, 1905. "Synopsis der Saurier der böhm. Kreideformation" ynopsis of the saurians of the Bohemian Cretaceous formation ''Sitzungsberichte der königlich-böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften'', II Classe. 1905(8), 1-7. {{Taxonbar, from=Q131782 Tanystropheids Prehistoric reptile genera Olenekian genus first appearances Anisian genera Ladinian genera Carnian genus extinctions Triassic reptiles of Europe Triassic Italy Fossils of Italy Triassic Switzerland Fossils of Switzerland Fossil taxa described in 1852 Taxa named by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer