Pinochet muerto.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, Interview with Attorney Hugo Gutierrez, by ''Memoria y Justicia'',21 February 2002 Pinochet resigned from his senatorial seat shortly after the Supreme Court's July 2002 ruling. In May 2004, the Supreme Court overturned its precedent decision, and ruled that he was capable of standing trial. In arguing their case, the prosecution presented a recent TV interview Pinochet had given to journalist

,

, 8 September 2006. as well as for the 1995 assassination of the DINA biochemist

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (, , , ; 25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean

Las consecuencias del caso Pinochet en la política chilena

Centro de. Estudios de la Realidad Contemporánea. Augusto Pinochet rose through the ranks of the

Furies of the Andes

." Pp. 239–275 in ''A Century of Revolution'', edited by G. M. Joseph and G. Grandin. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. . Retrieved 14 January 2014. Kornbluh, Peter. 2013. '' The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability''.

, ''

'', 1 December 2000 Guzmán advanced the charge of kidnapping as the 75 were officially "general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, first as the leader of the Military Junta of Chile from 1973 to 1981, being declared President of the Republic by the junta in 1974 and becoming the ''de facto'' dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in tim ...

of Chile, and from 1981 to 1990 as ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' President after a new Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

, which confirmed him in the office, was approved by a referendum in 1980. His rule remains the longest of any Chilean leader in history. Huneeus, Carlos (2007)Las consecuencias del caso Pinochet en la política chilena

Centro de. Estudios de la Realidad Contemporánea. Augusto Pinochet rose through the ranks of the

Chilean Army

The Chilean Army ( es, Ejército de Chile) is the land arm of the Military of Chile. This 80,000-person army (9,200 of which are conscripts) is organized into six divisions, a special operations brigade and an air brigade.

In recent years, and ...

to become General Chief of Staff in early 1972 before being appointed its Commander-in-Chief on 23 August 1973 by President Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (, , ; 26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean physician and socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 3 November 1970 until his death on 11 September 1973. He was the fir ...

. On 11 September 1973,

Pinochet seized power in Chile in a coup d'état, with the support of the US, Winn, Peter. 2010.Furies of the Andes

." Pp. 239–275 in ''A Century of Revolution'', edited by G. M. Joseph and G. Grandin. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. . Retrieved 14 January 2014. Kornbluh, Peter. 2013. '' The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability''.

The New Press

The New Press is an independent non-profit public-interest book publisher established in 1992 by André SchiffrinQureshi, Lubna Z. 2009. ''Nixon, Kissinger, and Allende: U.S. Involvement in the 1973 Coup in Chile.'' Lexington Books. . that toppled Allende's democratically elected left-wing Unidad Popular government and ended civilian rule. In December 1974, the ruling

.

The

The

The junta members originally planned that the presidency would be held for a year by the commanders-in-chief of each of the four military branches in turn. However, Pinochet soon consolidated his control, first retaining sole chairmanship of the military junta, and then proclaiming himself "Supreme Chief of the Nation" (''de facto'' provisional president) on 27 June 1974. He officially changed his title to "President" on 17 December 1974. General Leigh, head of the Air Force, became increasingly opposed to Pinochet's policies and was forced into retirement on 24 July 1978, after contradicting Pinochet on that year's plebiscite (officially called Consulta Nacional, or National Consultation, in response to a UN resolution condemning Pinochet's government). He was replaced by General

The junta members originally planned that the presidency would be held for a year by the commanders-in-chief of each of the four military branches in turn. However, Pinochet soon consolidated his control, first retaining sole chairmanship of the military junta, and then proclaiming himself "Supreme Chief of the Nation" (''de facto'' provisional president) on 27 June 1974. He officially changed his title to "President" on 17 December 1974. General Leigh, head of the Air Force, became increasingly opposed to Pinochet's policies and was forced into retirement on 24 July 1978, after contradicting Pinochet on that year's plebiscite (officially called Consulta Nacional, or National Consultation, in response to a UN resolution condemning Pinochet's government). He was replaced by General

Many other important officials of Allende's government were tracked down by the DINA in the frame of Operation Condor. General

Many other important officials of Allende's government were tracked down by the DINA in the frame of Operation Condor. General

, ''

Italian pdf.

In 1976,

Businesses recovered most of their lost industrial and agricultural holdings, for the junta returned properties to original owners who had lost them during expropriations, and sold other industries expropriated by Allende's Popular Unity government to private buyers. This period saw the expansion of business and widespread speculation. Financial conglomerates became major beneficiaries of the liberalized economy and the flood of foreign bank loans. Large foreign banks reinstated the credit cycle, as debt obligations, such as resuming payment of principal and interest installments, were honored. International lending organizations such as the

Political advertising was legalized on 5 September 1987, as a necessary element for the campaign for the "NO" to the referendum, which countered the official campaign, which presaged a return to a Popular Unity government in case of a defeat of Pinochet. The Opposition, gathered into the '' Concertación de Partidos por el NO'' ("Coalition of Parties for NO"), organized a colorful and cheerful campaign under the slogan '' La alegría ya viene'' ("Joy is coming"). It was formed by the Christian Democracy, the

Political advertising was legalized on 5 September 1987, as a necessary element for the campaign for the "NO" to the referendum, which countered the official campaign, which presaged a return to a Popular Unity government in case of a defeat of Pinochet. The Opposition, gathered into the '' Concertación de Partidos por el NO'' ("Coalition of Parties for NO"), organized a colorful and cheerful campaign under the slogan '' La alegría ya viene'' ("Joy is coming"). It was formed by the Christian Democracy, the

Chilean governmental website of the votes, against 44.01% of "YES" votes. In the wake of his electoral defeat, Pinochet attempted to implement a plan for an auto-coup. He attempted to implement efforts to orchestrate chaos and violence in the streets to justify his power grab, however, the Carabinero police refused an order to lift the cordon against street demonstrations in the capital, according to a CIA informant. In his final move, Pinochet convened a meeting of his junta at Thereafter, Aylwin won the December 1989 presidential election with 55% of the votes, against less than 30% for the right-wing candidate,

Thereafter, Aylwin won the December 1989 presidential election with 55% of the votes, against less than 30% for the right-wing candidate,

, ''

'', 25 March 2000

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of judge Juan Guzmán's request in August 2000, and Pinochet was indicted on 1 December 2000 for the kidnapping of 75 opponents in the Caravan of Death case.Pinochet charged with kidnappingmilitary junta

A military junta () is a government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the national and local junta organized by the Spanish resistance to Napoleon's invasion of Spain in ...

appointed Pinochet Supreme Head of the nation by joint decree, although without the support of one of the coup's instigators, Air Force General Gustavo Leigh

Air General Gustavo Leigh Guzmán (September 19, 1920 – September 29, 1999) was a Chilean general, who represented the Air Force in the 1973 Chilean coup d'état and, for a time, in the ruling junta that followed. Leigh was forced out of th ...

. After his rise to power, Pinochet persecuted leftists, socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

, and political critics, resulting in the executions of 1,200 to 3,200 people, the internment of as many as 80,000 people, and the torture of tens of thousands. According to the Chilean government, the number of executions and forced disappearance

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a State (polity), state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or po ...

s was at least 3,095. Operation Condor

Operation Condor ( es, link=no, Operación Cóndor, also known as ''Plan Cóndor''; pt, Operação Condor) was a United States–backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence operations and assassination of op ...

, a U.S.-supported terror operation focusing on South America, was founded at the behest of the Pinochet regime in late November 1975, his 60th birthday.

Under the influence of the free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

-oriented " Chicago Boys", Pinochet's military government implemented economic liberalization

Economic liberalization (or economic liberalisation) is the lessening of government regulations and restrictions in an economy in exchange for greater participation by private entities. In politics, the doctrine is associated with classical liber ...

following neoliberalism

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

, including currency stabilization, removed tariff protections for local industry, banned trade unions, and privatized

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

social security and hundreds of state-owned enterprises. Some of the government properties were sold below market price to politically connected buyers, including Pinochet's own son-in-law. The regime used censorship of entertainment as a way to reward supporters of the regime and punish opponents. These policies produced high economic growth, but critics state that economic inequality

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of ...

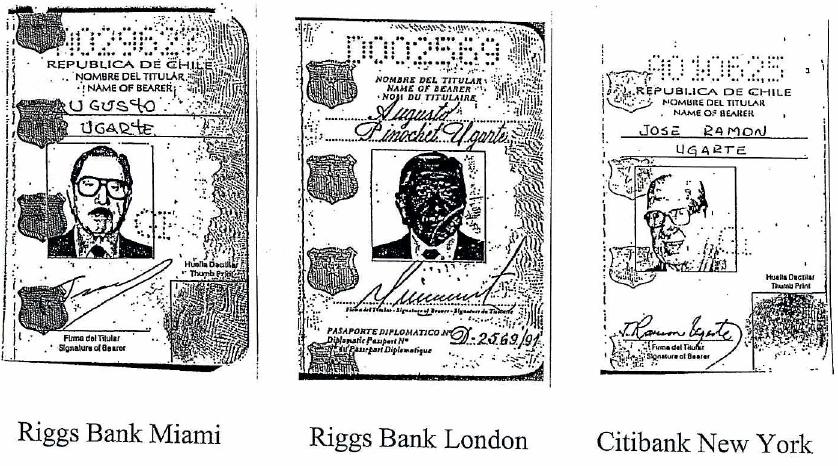

dramatically increased and attribute the devastating effects of the 1982 monetary crisis on the Chilean economy to these policies. For most of the 1990s, Chile was the best-performing economy in Latin America, though the legacy of Pinochet's reforms continues to be in dispute.Leonard, Thomas M. ''Encyclopedia Of The Developing World.'' Routledge. . p. 322 His fortune grew considerably during his years in power through dozens of bank accounts secretly held abroad and a fortune in real estate. He was later prosecuted for embezzlement, tax fraud, and for possible commissions levied on arms deals.

Pinochet's 17-year rule was given a legal framework through a controversial 1980 plebiscite, which approved a new constitution drafted by a government-appointed commission. In a 1988 plebiscite, 56% voted against Pinochet's continuing as president, which led to democratic elections for the presidency and Congress. After stepping down in 1990, Pinochet continued to serve as Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Army until 10 March 1998, when he retired and became a senator-for-life in accordance with his 1980 Constitution. However, Pinochet was arrested under an international arrest warrant on a visit to London on 10 October 1998 in connection with numerous human rights violations

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hum ...

. Following a legal battle, he was released on grounds of ill-health and returned to Chile on 3 March 2000. In 2004, Chilean Judge Juan Guzmán Tapia

Juan Salvador Guzmán Tapia (; 22 April 1939 – 22 January 2021) was a Chilean judge. He was the first Chilean judge to lead investigations and prosecute Augusto Pinochet for violations of human rights during his dictatorship between 1973 an ...

ruled that Pinochet was medically fit to stand trial and placed him under house arrest. By the time of his death on 10 December 2006, about 300 criminal charges were still pending against him in Chile for numerous human rights violations during his 17-year rule, as well as tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the tax ...

and embezzlement during and after his rule. He was also accused of having corruptly amassed at least US$28 million.

Early life and education

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte was born inValparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

on 25 November 1915. He was the son and namesake of Augusto Pinochet Vera (1891–1944), a descendant of an 18th century French Breton immigrant from Lamballe

Lamballe (; ; Gallo: ''Lanball'') is a town and a former commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department in Brittany in northwestern France. On 1 January 2019, it was merged into the new commune Lamballe-Armor.

It lies on the river Gouessant east-s ...

, and Avelina Ugarte Martínez (1895–1986), a woman of Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

heritage whose family had been in Chile since the 17th century.

Pinochet went to primary and secondary school at the San Rafael Seminary of Valparaíso, the Rafael Ariztía Institute (Marist Brothers

The Marist Brothers of the Schools, commonly known as simply the Marist Brothers, is an international community of Catholic religious institute of brothers. In 1817, St. Marcellin Champagnat, a Marist priest from France, founded the Marist Brothe ...

) in Quillota

Quillota is a city located in the Aconcagua River valley in central Chile's Valparaíso Region. It is the capital and largest city of Quillota Province, where many inhabitants live in the outlying farming areas of San Isidro, La Palma, Pococ ...

, the French Fathers' School of Valparaíso, and then to the Military School in Santiago, which he entered in 1931. In 1935, after four years studying military geography

Military geography is a sub-field of geography that is used by the military, as well as academics and politicians, to understand the geopolitical sphere through the military lens. To accomplish these ends, military geographers consider topics fro ...

, he graduated with the rank of ''alférez'' ( Second Lieutenant) in the infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

.

Military career

In September 1937, Pinochet was assigned to the "Chacabuco" Regiment, in Concepción. Two years later, in 1939, then with the rank of Sub-lieutenant, he moved to the "Maipo" Regiment, garrisoned in Valparaíso. He returned to Infantry School in 1940. On 30 January 1943, Pinochet married Lucía Hiriart Rodríguez, with whom he had five children: Inés Lucía, María Verónica, Jacqueline Marie, Augusto Osvaldo and Marco Antonio. By late 1945, Pinochet had been assigned to the "Carampangue" Regiment in the northern city ofIquique

Iquique () is a port city and commune in northern Chile, capital of both the Iquique Province and Tarapacá Region. It lies on the Pacific coast, west of the Pampa del Tamarugal, which is part of the Atacama Desert. It has a population of 191, ...

. Three years later, he entered the Chilean War Academy but had to postpone his studies because, being the youngest officer, he had to carry out a service mission in the coal zone of Lota. In 1948, Pinochet was initiated in the regular Masonic Lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

''Victoria n°15'' of San Bernardo, affiliated to the Grand Lodge of Chile. He received the Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the S ...

degree of companion, but he is thought not to have ever become a Grand Master.

The following year he returned to his studies in the academy, and after obtaining the title of Officer Chief of Staff, in 1951, he returned to teach at the Military School. At the same time, he worked as a teachers' aide at the War Academy, giving military geography and geopolitics classes. He was also the editor of the institutional magazine ''Cien Águilas'' ('One Hundred Eagles'). At the beginning of 1953, with the rank of major, he was sent for two years to the "Rancagua" Regiment in Arica

Arica ( ; ) is a commune and a port city with a population of 222,619 in the Arica Province of northern Chile's Arica y Parinacota Region. It is Chile's northernmost city, being located only south of the border with Peru. The city is the capita ...

. While there, he was appointed professor of the Chilean War Academy, and returned to Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

to take up his new position.

In 1956, Pinochet and a group of young officers were chosen to form a military mission to collaborate in the organization of the War Academy of Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

in Quito. He remained with the Quito mission for four-and-a-half years, during which time he studied geopolitics, military geography

Military geography is a sub-field of geography that is used by the military, as well as academics and politicians, to understand the geopolitical sphere through the military lens. To accomplish these ends, military geographers consider topics fro ...

and military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

. At the end of 1959 he returned to Chile and was sent to General Headquarters of the 1st Army Division, based in Antofagasta

Antofagasta () is a port city in northern Chile, about north of Santiago. It is the capital of Antofagasta Province and Antofagasta Region. According to the 2015 census, the city has a population of 402,669.

After the Spanish American wars ...

. The following year, he was appointed commander of the "Esmeralda" Regiment. Due to his success in this position, he was appointed Sub-director of the War Academy in 1963. In 1968, he was named Chief of Staff of the 2nd Army Division, based in Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

, and at the end of that year, he was promoted to brigadier general and Commander in Chief of the 6th Division, garrisoned in Iquique. In his new function, he was also appointed Intendent of the Tarapacá

San Lorenzo de Tarapacá, also known simply as Tarapacá, is a town in the region of the same name in Chile.

History

The town has likely been inhabited since the 12th century, when it formed part of the Inca trail. When Spanish explorer Diego ...

Province.

In January 1971, Pinochet was promoted to division general and was named General Commander of the Santiago Army Garrison. On 8 June 1971, following the assassination of Edmundo Perez Zujovic Edmundo is a common name that is used by many individuals including:

* Edmundo Alves de Souza Neto, former Brazilian football player

* Edmundo Farolan, Filipino writer

* Edmundo Ros, Trinidadian musician

* Edmundo Rivero, Argentine singer

* Edmundo ...

by left-wing radicals, Allende appointed Pinochet a supreme authority of Santiago province, imposing a military curfew in the process, which was later lifted. However, on 2 December 1971, following a series of peaceful protests against economic policies of Allende, the curfew was re-installed, all protests prohibited, with Pinochet leading the crackdown on anti-Allende protests. At the beginning of 1972, he was appointed General Chief of Staff of the Army. With rising domestic strife in Chile, after General Prats resigned his position, Pinochet was appointed commander-in-chief of the Army on 23 August 1973 by President Salvador Allende just one day after the Chamber of Deputies of Chile approved a resolution

Resolution(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Resolution (debate), the statement which is debated in policy debate

* Resolution (law), a written motion adopted by a deliberative body

* New Year's resolution, a commitment that an individual mak ...

asserting that the government was not respecting the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

. Less than a month later, the Chilean military deposed Allende.

Military coup of 1973

On 11 September 1973, the combined Chilean Armed Forces (the Army, Navy, Air Force, andCarabineros

The was an armed carabiniers force of Spain under both the monarchy and the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic. The formal mission of this paramilitary gendarmerie was to patrol the coasts and borders of the country, operating against ...

) overthrew Allende's government in a coup, during which the presidential palace, La Moneda

Palacio de La Moneda (, ''Palace of the Mint''), or simply La Moneda, is the seat of the President of the Republic of Chile. It also houses the offices of three cabinet ministers: Interior, General Secretariat of the Presidency and General Secre ...

, was shelled and where Allende was said to have committed suicide. While the military claimed that he had committed suicide, controversy surrounded Allende's death, with many claiming that he had been assassinated (such theory was discarded by the Chilean Supreme Court in 2014).

In his memoirs, Pinochet said that he was the leading plotter of the coup and had used his position as commander-in-chief of the Army to coordinate a far-reaching scheme with the other two branches of the military and the national police. In later years, however, high military officials from the time have said that Pinochet reluctantly became involved only a few days before the coup was scheduled to occur, and followed the lead of the other branches (especially the Navy, under Merino) as they executed the coup.

The new government rounded up thousands of people and held them in the national stadium

Many countries have a national sport stadium, which typically serves as the primary or exclusive home for one or more of a country's national representative sports teams. The term is most often used in reference to an association football stadiu ...

, where many were killed. This was followed by brutal repression during Pinochet's rule, during which approximately 3,000 people were killed, while more than 1,000 are still missing.

In the months that followed the coup, the ''junta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

'', with authoring work by historian Gonzalo Vial and admiral Patricio Carvajal

Vice Admiral Patricio Carvajal Prado (16 July 1916 – 15 July 1994), was a Chilean admiral, several times Minister and one of the principal leaders of the 1973 Chilean coup d'état that ousted President Salvador Allende.

Military career

He jo ...

, published a book titled ''El Libro Blanco del cambio de gobierno en Chile'' (commonly known as ''El Libro Blanco'', ' The White Book on the Change of Government in Chile'), in which they said that they were in fact anticipating a self-coup (the alleged ''Plan Zeta

A plan is typically any diagram or list of steps with details of timing and resources, used to achieve an objective to do something. It is commonly understood as a temporal set of intended actions through which one expects to achieve a goal.

...

'', or Plan Z) that Allende's government or its associates were purportedly preparing. United States intelligence agencies believed the plan to be untrue propaganda. Although later discredited and officially recognized as the product of political propaganda,Comisión Nacional sobre Prisión Política y Tortura CAPÍTULO III Contexto.

Gonzalo Vial Correa

Gonzalo Vial Correa (29 August 1930 – 30 October 2009) was a Chilean historian, lawyer and journalist. He was a member of the State Defense Council and the Council on Ethics in Social Media.

insists in the similarities between the alleged Plan Z and other existing paramilitary plans of the Popular Unity parties in support of its legitimacy. Pinochet was also trained by the School of the Americas

The Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), formerly known as the School of the Americas, is a United States Department of Defense school located at Fort Benning in Columbus, Georgia, renamed in the 2001 National Defen ...

(SOA) where it is likely he first encountered the ideals of the coup.

Canadian reporter Jean Charpentier of Télévision de Radio-Canada was the first foreign journalist to interview General Pinochet following the coup. After Allende's final radio address, he shot himself rather than becoming a prisoner.

U.S. backing of the coup

The

The Church Report

The Church report on detainee interrogation and incarceration (officially ''Review of Department of Defense Detention Operations and Detainee Interrogation Techniques'') is a report completed under the direction of Vice Admiral Albert T. Church, ...

investigating the fallout of the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

stated that while the U.S. tacitly supported the Pinochet government after the 1973 coup, there was "no evidence" that the US was directly involved in it. This view has been contradicted by several academics, such as Peter Winn

Peter Winn (born 1942) is a professor of history at Tufts University specializing in Latin America. He has written several books, including ''Americas'', which he developed while serving as academic director for the 1993 PBS series of the same na ...

, who writes that the role of the CIA was crucial to the consolidation of power after the coup; the CIA helped fabricate a conspiracy against the Allende government, which Pinochet was then portrayed as preventing. He stated that the coup itself was possible only through a three-year covert operation mounted by the United States. Winn also points out that the US imposed an "invisible blockade" that was designed to disrupt the economy under Allende, and contributed to the destabilization of the regime. Author Peter Kornbluh

Peter Kornbluh (born 1956) is the director of the National Security Archive's Chile Documentation Project and Cuba Documentation Project.

He played a large role in the campaign to declassify government documents, via the Freedom of Information ...

argues in ''The Pinochet File

''The Pinochet File'' is a National Security Archive book written by Peter Kornbluh covering over approximately two decades of declassified documents, from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), White House, and ...

'' that the US was extensively involved and actively "fomented" the 1973 coup. Authors Tim Weiner

Tim Weiner (born June 20, 1956) is an American reporter and author. He is the author of five books and co-author of a sixth, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award.

Biography

Weiner graduated from Columbia University with a ...

( ''Legacy of Ashes'') and Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

('' The Trial of Henry Kissinger'') similarly argue the case that US covert actions actively destabilized Allende's government and set the stage for the 1973 coup. Despite denial of countless American agencies, current declassified documentation has proven the American involvement. Nixon and Kissinger, along with both private and public intelligence agencies were "apprised of, and even enmeshed in, the planning and executing of the military takeover." Along with this, CIA operatives directly involved, such as Jack Devine, have also come out and declared their involvement in the coup. Devine stating "I sent CIA headquarters a special type of top-secret cable known as a CRITIC, which ... goes directly to the highest levels of government."

The US provided material support to the military government after the coup, although criticizing it in public. A document released by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) in 2000, titled "CIA Activities in Chile", revealed that the CIA actively supported the military junta after the overthrow of Allende, and that it made many of Pinochet's officers into paid contacts of the CIA or U.S. military, even though some were known to be involved in human rights abuses. The CIA also maintained contacts in the Chilean DINA intelligence service. DINA led the multinational campaign known as Operation Condor

Operation Condor ( es, link=no, Operación Cóndor, also known as ''Plan Cóndor''; pt, Operação Condor) was a United States–backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence operations and assassination of op ...

, which amongst other activities carried out assassinations of prominent politicians in various Latin American countries, in Washington, D.C., and in Europe, and kidnapped, tortured and executed activists holding left-wing views, which culminated in the deaths of roughly 60,000 people. The United States provided key organizational, financial and technical assistance to the operation. CIA contact with DINA head Manuel Contreras

Juan Manuel "Mamo" Guillermo Contreras Sepúlveda (4 May 1929 – 7 August 2015) was a Chilean Army officer and the former head of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional, National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), Chile's secret police during the ...

was established in 1974 soon after the coup, during the Junta period prior to official transfer of Presidential powers to Pinochet; in 1975, the CIA reviewed a warning that keeping Contreras as an asset

In financial accounting, an asset is any resource owned or controlled by a business or an economic entity. It is anything (tangible or intangible) that can be used to produce positive economic value. Assets represent value of ownership that can ...

might threaten human rights in the region. The CIA chose to keep him as an asset, and at one point even paid him. In addition to the CIA's maintaining of assets in DINA beginning soon after the coup, several CIA assets, such as CORU Cuban exile

A Cuban exile is a person who emigrated from Cuba in the Cuban exodus. Exiles have various differing experiences as emigrants depending on when they migrated during the exodus.

Demographics Social class

Cuban exiles would come from various ec ...

militants Orlando Bosch

Orlando Bosch Ávila (18 August 1926 – 27 April 2011) was a Cuban exile militant, who headed the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations (CORU), described by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation as a terrorist or ...

and Guillermo Novo, collaborated in DINA operations under the Condor Plan in the early years of Pinochet's presidency.

Military junta

Amilitary junta

A military junta () is a government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the national and local junta organized by the Spanish resistance to Napoleon's invasion of Spain in ...

was established immediately following the coup, made up of General Pinochet representing the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, Admiral José Toribio Merino representing the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

, General Gustavo Leigh

Air General Gustavo Leigh Guzmán (September 19, 1920 – September 29, 1999) was a Chilean general, who represented the Air Force in the 1973 Chilean coup d'état and, for a time, in the ruling junta that followed. Leigh was forced out of th ...

representing the Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

, and General César Mendoza representing the ''Carabineros'' (national police). As established, the junta exercised both executive and legislative functions of the government, suspended the Constitution and the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, imposed strict censorship and curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

, banned all parties and halted all political and perceived subversive activities. This military junta held the executive role until 17 December 1974, after which it remained strictly as a legislative body, the executive powers being transferred to Pinochet with the title of President.

Military dictatorship (1973–1990)

The junta members originally planned that the presidency would be held for a year by the commanders-in-chief of each of the four military branches in turn. However, Pinochet soon consolidated his control, first retaining sole chairmanship of the military junta, and then proclaiming himself "Supreme Chief of the Nation" (''de facto'' provisional president) on 27 June 1974. He officially changed his title to "President" on 17 December 1974. General Leigh, head of the Air Force, became increasingly opposed to Pinochet's policies and was forced into retirement on 24 July 1978, after contradicting Pinochet on that year's plebiscite (officially called Consulta Nacional, or National Consultation, in response to a UN resolution condemning Pinochet's government). He was replaced by General

The junta members originally planned that the presidency would be held for a year by the commanders-in-chief of each of the four military branches in turn. However, Pinochet soon consolidated his control, first retaining sole chairmanship of the military junta, and then proclaiming himself "Supreme Chief of the Nation" (''de facto'' provisional president) on 27 June 1974. He officially changed his title to "President" on 17 December 1974. General Leigh, head of the Air Force, became increasingly opposed to Pinochet's policies and was forced into retirement on 24 July 1978, after contradicting Pinochet on that year's plebiscite (officially called Consulta Nacional, or National Consultation, in response to a UN resolution condemning Pinochet's government). He was replaced by General Fernando Matthei

Fernando Matthei Aubel (11 July 1925 – 19 November 2017) was a Chilean Air Force general who was part of the military junta that ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, replacing the dismissed Gustavo Leigh as commander-in-chief of the Chilean Air ...

.

Pinochet organized a plebiscite on 11 September 1980 to ratify a new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

, replacing the 1925 Constitution drafted during Arturo Alessandri

Arturo Fortunato Alessandri Palma (; December 20, 1868 – August 24, 1950) was a Chilean political figure and reformer who served thrice as president of Chile, first from 1920 to 1924, then from March to October 1925, and finally from 1932 to ...

's presidency. The new Constitution, partly drafted by Jaime Guzmán

Jaime Jorge Guzmán Errázuriz (June 28, 1946 – April 1, 1991) was a Chilean constitutional law professor, speechwriter and member and doctrinal founder of the conservative Independent Democrat Union party. In the 1960s he opposed the Universit ...

, a close adviser to Pinochet who later founded the right-wing party Independent Democratic Union

The Independent Democratic Union (''Unión Demócrata Independiente'', UDI) is a conservative and right-wing political party in Chile, founded in 1983. Its founder was the lawyer, politician and law professor Jaime Guzmán, a civilian allied with ...

(UDI), gave a lot of power to the President of the Republic—Pinochet. It created some new institutions, such as the Constitutional Tribunal and the controversial National Security Council (COSENA). It also prescribed an 8-year presidential period, and a single-candidate presidential referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

in 1988, where a candidate nominated by the Junta would be approved or rejected for another 8-year period. The new constitution was approved by a margin of 67.04% to 30.19% according to official figures; the opposition, headed by ex-president Eduardo Frei Montalva

Eduardo Nicanor Frei Montalva (; 16 January 1911 – 22 January 1982) was a Chilean political leader. In his long political career, he was Minister of Public Works, president of his Christian Democratic Party, senator, President of the ...

(who had supported Pinochet's coup), denounced extensive irregularities such as the lack of an electoral register

An electoral roll (variously called an electoral register, voters roll, poll book or other description) is a compilation that lists persons who are entitled to vote for particular elections in a particular jurisdiction. The list is usually broke ...

, which facilitated multiple voting, and said that the total number of votes reported to have been cast was very much larger than would be expected from the size of the electorate and turnout in previous elections. Interviews after Pinochet's departure with people involved with the referendum confirmed that fraud had, indeed, been widespread. The Constitution was promulgated on 21 October 1980, taking effect on 11 March 1981. Pinochet was replaced as President of the Junta that day by Admiral Merino. During Pinochet's reign it is estimated that some one million people had been forced to flee the country.

Armed opposition to the Pinochet rule continued in remote parts of the country. In a massive operation spearheaded by Chilean Army para-commandos, some 2,000 security forces troops were deployed in the mountains of Neltume

Neltume is a Chilean town in Panguipulli commune, of Los Ríos Region. It lies along the 203-CH route to Huahum Pass into Argentina. The town's main economic activities are forestry and, more recently, tourism since the Huilo-Huilo Biological ...

from June to November 1981, where they destroyed two MIR

''Mir'' (russian: Мир, ; ) was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. ''Mir'' was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to&n ...

bases, seizing large caches of munitions and killing a number of guerrillas.

According to author Ozren Agnic Krstulovic, weapons including C-4 plastic explosive

Plastic explosive is a soft and hand-moldable solid form of explosive material. Within the field of explosives engineering, plastic explosives are also known as putty explosives

or blastics.

Plastic explosives are especially suited for explo ...

s, RPG-7

The RPG-7 (russian: link=no, РПГ-7, Ручной Противотанковый Гранатомёт, Ruchnoy Protivotankoviy Granatomyot) is a portable, reusable, unguided, shoulder-launched, anti-tank, rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Th ...

and M72 LAW rocket launchers, as well as more than 3,000 M-16 rifles, were smuggled into the country by opponents of the government.

In September 1986, weapons from the same source were used in an unsuccessful assassination attempt against Pinochet by the FPMR. His military bodyguard was taken by surprise, and five members were killed. Pinochet's bulletproof Mercedes Benz vehicle was struck by a rocket, but it failed to explode and Pinochet suffered only minor injuries.

Suppression of opposition

Almost immediately after the military's seizure of power, the junta banned all the leftist parties that had constituted Allende's UP coalition.. Retrieved 24 October 2006. All other parties were placed in "indefinite recess" and were later banned outright. The government's violence was directed not only against dissidents but also against their families and other civilians. TheRettig Report

The Rettig Report, officially The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation Report, is a 1991 report by a commission designated by Chilean President Patricio Aylwin (from the ''Concertación'') detailing human rights abuses resulting in dea ...

concluded 2,279 persons who disappeared during the military government were killed for political reasons or as a result of political violence. According to the later Valech Report

The Valech Report (officially The National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture Report) is a record of abuses committed in Chile between 1973 and 1990 by agents of Augusto Pinochet's military regime. The report was published on November ...

approximately 31,947 were tortured and 1,312 exiled. The exiles were chased all over the world by the intelligence agencies. In Latin America, this was made in the frame of Operation Condor, a cooperation plan between the various intelligence agencies of South American countries, assisted by a United States CIA communication base in Panama. Pinochet believed these operations were necessary in order to "save the country from communism". In 2011, the commission identified an additional 9,800 victims of political repression during Pinochet's rule, increasing the total number of victims to approximately 40,018, including 3,065 killed.

Some political scientists have ascribed the relative bloodiness of the coup to the stability of the existing democratic system, which required extreme action to overturn. Some of the most infamous cases of human rights violation occurred during the early period: in October 1973, at least 70 people were killed throughout the country by the Caravan of Death. Charles Horman

Charles Edmund Lazar Horman (May 15, 1942 – September 19, 1973) was an American journalist and documentary filmmaker. He was executed in Chile in the days following the 1973 Chilean coup d'état led by General Augusto Pinochet, which overthr ...

and Frank Teruggi Frank Teruggi, Jr. (1949–1973) was an American student, journalist, and member of the Industrial Workers of the World, from Chicago, Illinois, who became one of the victims of General Augusto Pinochet's military shortly after the September 11, 197 ...

, both U.S. journalists, "disappeared

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organi ...

", as did Víctor Olea Alegría Víctor Olea Alegría (born 17 June 1950) was a member (''militante'') of Chile's Partido Socialista.

Olea lived in Santiago, Chile. He was detained by “ security agents” on 11 September 1974, and became one of the "detenidos desaparecidos". ...

, a member of the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

, and many others, in 1973. British priest Michael Woodward, who vanished within 10 days of the coup, was tortured and beaten to death aboard the Chilean naval ship, ''Esmeralda''.

Many other important officials of Allende's government were tracked down by the DINA in the frame of Operation Condor. General

Many other important officials of Allende's government were tracked down by the DINA in the frame of Operation Condor. General Carlos Prats

Carlos Prats González (; February 24, 1915 – September 30, 1974) was a Chilean Army officer and politician. He served as a minister in Salvador Allende's government while Commander-in-chief of the Chilean Army. Immediately after General August ...

, Pinochet's predecessor and army commander under Allende, who had resigned rather than support the moves against Allende's government, was assassinated in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, in 1974. A year later, the murder of 119 opponents abroad was disguised as an internal conflict, the DINA setting up a propaganda campaign to support this idea (Operation Colombo Operation Colombo was an operation undertaken by the DINA (the Chilean secret police) in 1975 to make political dissidents disappear. At least 119 people are alleged to have been abducted and later killed. The magazines published a list of 119 de ...

), a campaign publicised by the leading newspaper in Chile, El Mercurio.

Other victims of Condor included, among hundreds of less famous persons, Juan José Torres

Juan José Torres González (5 March 1920 – 2 June 1976) was a Bolivian socialist politician and military leader who served as the 50th president of Bolivia from 1970 to 1971, when he was ousted in a US-supported coup that resulted in ...

, the former President of Bolivia

The president of Bolivia ( es, Presidente de Bolivia), officially known as the president of the Plurinational State of Bolivia ( es, Presidente del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia), is head of state and head of government of Bolivia and the ca ...

, assassinated in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

on 2 June 1976; Carmelo Soria

Carmelo Soria (Madrid, 5 November 1921 – Santiago de Chile, 16 July 1976) was a Spanish-Chilean United Nations diplomat. A member of the CEPAL (United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) in the 1970s, he was assass ...

, a UN diplomat working for the CEPAL, assassinated in July 1976;

Orlando Letelier

Marcos Orlando Letelier del Solar (13 April 1932 – 21 September 1976) was a Chilean economist, politician and diplomat during the presidency of Salvador Allende. A refugee from the Military government of Chile (1973–1990), military dictato ...

, a former Chilean ambassador to the United States and minister in Allende's cabinet, assassinated after his release from internment and exile in Washington, D.C. by a car bomb on 21 September 1976. Documents confirm that Pinochet directly ordered the assassination of Letelier. This led to strained relations with the US and to the extradition of Michael Townley

Michael Vernon Townley (born December 5, 1942, in Waterloo, Iowa) is an American-born former agent of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), the secret police of Chile during the regime of Augusto Pinochet. In 1978, Townley pled guilty t ...

, a US citizen who worked for the DINA and had organized Letelier's assassination. Other targeted victims, who escaped assassination, included Christian-Democrat Bernardo Leighton

Bernardo Leighton Guzmán (August 16, 1909, Negrete, Bío Bío Province – January 26, 1995, Santiago) was a Chilean Christian Democratic Party politician and lawyer. He served as minister of state under three presidents over a 36-year care ...

, who escaped an assassination attempt in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in 1975 by the Italian terrorist Stefano delle Chiaie

Stefano Delle Chiaie (13 September 1936, Caserta – 10 September 2019, Rome) was an Italian neo-fascist terrorist. He was the founder of ''Avanguardia Nazionale'', a member of '' Ordine Nuovo'', and founder of Lega nazionalpopolare. He went on ...

; Carlos Altamirano, the leader of the Chilean Socialist Party, targeted for murder in 1975 by Pinochet, along with Volodia Teitelboim Volodia Teitelboim.

Volodia Teitelboim Volosky (originally ''Valentín Teitelboim Volosky''; March 17, 1916 – January 31, 2008) was a Chilean communist politician, lawyer, and author.

Personal life

Born in Chillán to Jewish immigrants (Ukrainia ...

, member of the Communist Party; Pascal Allende

Pascal, Pascal's or PASCAL may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Pascal (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Pascal (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** Blaise Pascal, Fren ...

, the nephew of Salvador Allende and president of the MIR, who escaped an assassination attempt in Costa Rica in March 1976; US Congressman Edward Koch

Edward Irving Koch ( ; December 12, 1924February 1, 2013) was an American politician, lawyer, political commentator, film critic, and television personality. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1977 and was mayo ...

, who became aware in 2001 of relations between death threats and his denunciation of Operation Condor, etc. Furthermore, according to current investigations, Eduardo Frei Montalva, the Christian Democrat President of Chile from 1964 to 1970, may have been poisoned in 1982 by toxin produced by DINA biochemist Eugenio Berrios

Eugenio is an Italian and Spanish masculine given name deriving from the Greek ' Eugene'. The name is Eugénio in Portuguese and Eugênio in Brazilian Portuguese.

The name's translated literal meaning is well born, or of noble status. Similar de ...

.

Protests continued, however, during the 1980s, leading to several scandals. In March 1985, the murder of three Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

members led to the resignation of César Mendoza, head of the Carabineros and member of the ''junta'' since its formation. During a 1986 protest against Pinochet, 21-year-old American photographer Rodrigo Rojas DeNegri

Rodrigo Andrés Rojas de Negri (7 March 1967 – 6 July 1986), known as Rodrigo Rojas, was a young photographer who was burned alive during a street demonstration against the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet in Chile.

Background

Rodrig ...

and 18-year-old student Carmen Gloria Quintana

Carmen Gloria Quintana Arancibia (born 3 October 1967) is a Chilean woman who suffered severe burns in an incident where she and other young people were detained by an army patrol during a street demonstration against the dictatorship of Augusto ...

were burnt alive, with only Carmen surviving.

In August 1989, Marcelo Barrios Andres, a 21-year-old member of the FPMR (the armed wing of the PCC, created in 1983, which had attempted to assassinate Pinochet on 7 September 1986), was assassinated by a group of military personnel who were supposed to arrest him on orders of Valparaíso's public prosecutor. However, they simply executed him; this case was included in the Rettig Report.Capítulos desconocidos de los mercenarios chilenos en Honduras camino de Iraq, ''

La Nación

''La Nación'' () is an Argentine daily newspaper. As the country's leading conservative newspaper, ''La Nación''s main competitor is the more liberal '' Clarín''. It is regarded as a newspaper of record for Argentina.

Its motto is: "''La Na ...

'', 25 September 2005 – URL accessed on 14 February 2007 Among the killed and disappeared during the military junta were 440 MIR guerrillas. In December 2015, three former DINA agents were sentenced to ten years in prison for the murder of a 29-year-old theology student and activist, German Rodriguez Cortes, in 1978. That same month 62-year-old Guillermo Reyes Rammsy, a former Chilean soldier during the Pinochet years, was arrested and charged with murder for boasting of participating in 18 executions during a live phone-in to the Chilean radio show "Chacotero Sentimental".

On 2 June 2017, Chilean judge Hernan Cristoso sentenced 106 former Chilean intelligence officials to between 541 days and 20 years in prison for their role in the kidnapping and murder of 16 left-wing activists in 1974 and 1975.

Economic policy

In 1973, the Chilean economy was deeply depressed for several reasons. Allende's government had expropriated many Chilean and foreign businesses, including all copper mines, and had controlled prices. Inflation had reached 606%, income per capita had contracted by 7.14% in 1973 alone and 30% compared to 1970, GDP had contracted by 5% in 1973, and public spending rose from 22.6% to 44.9% of GDP between 1970 and 1973, creating a deficit equal to 25% of GDP. While some authors like Peter Kornbluh also argue that economic sanctions by theNixon administration

Richard Nixon's tenure as the 37th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1969, and ended when he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of almost certain impeachment because of the Watergate Scanda ...

helped to create the economic crisis, others like Paul Sigmund and Mark Falcoff argue there was no blockade because aid and credit still existed (albeit in smaller quantities), and no formal trade embargo had been declared.

By mid-1975, after two years of Keynesianism

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output ...

, the government set forth an economic policy of free-market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

reforms that attempted to stop inflation and collapse. Pinochet declared that he wanted "to make Chile not a nation of proletarian

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philoso ...

s, but a nation of proprietor

Ownership is the state or fact of legal possession and control over property, which may be any asset, tangible or intangible. Ownership can involve multiple rights, collectively referred to as title, which may be separated and held by different ...

s". To formulate the economic rescue, the government relied on the so-called Chicago Boys and a text called ''El ladrillo

''El ladrillo'' (English: ''The Brick'') is a study considered the base of many of the economic policies followed by the military dictatorship that ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990. La transformación económica de chilena entre 1973-2003'. Memoria ...

,'' and although Chile grew very quickly between 1976 and 1981, it had a large amount of debt which made Chile the most affected nation by the Latin American debt crisis.

In sharp contrast to the privatization done in other areas, Chile's nationalized main copper mines remained in government hands, with the 1980 Constitution later declaring the mines "inalienable".Spanish pdf.Codelco

Codelco (''Corporación Nacional'' ''del'' ''Cobre de Chile'' or, in English, the National Copper Corporation of Chile) is a Chilean state-owned copper mining company. It was formed in 1976 from foreign-owned copper companies that were nationalise ...

was established to exploit them but new mineral deposits were opened to private investment. In November 1980, the pension system was restructured from a PAYGO-system to a fully funded capitalization system run by private sector pension funds.Joaquin Vial Ruiz-Tagle, Francisca Castro, The Chilean Pension System, OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate e ...

Ageing Working Papers, 1998, page 6 Healthcare and education were likewise privatized. These mines would ultimately help them economically; however, they would fall partly in American hands.

Wages decreased by 8%. Family allowances in 1989 were 28% of what they had been in 1970 and the budgets for education, health and housing had dropped by over 20% on average. The junta relied on the middle class, the oligarchy, foreign corporations, and foreign loans to maintain itself.Preview.Businesses recovered most of their lost industrial and agricultural holdings, for the junta returned properties to original owners who had lost them during expropriations, and sold other industries expropriated by Allende's Popular Unity government to private buyers. This period saw the expansion of business and widespread speculation. Financial conglomerates became major beneficiaries of the liberalized economy and the flood of foreign bank loans. Large foreign banks reinstated the credit cycle, as debt obligations, such as resuming payment of principal and interest installments, were honored. International lending organizations such as the

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Inte ...

, the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster glo ...

, and the Inter-American Development Bank lent vast sums anew. Many foreign multinational corporations such as International Telephone and Telegraph

ITT Inc., formerly ITT Corporation, is an American worldwide manufacturing company based in Stamford, Connecticut. The company produces specialty components for the aerospace, transportation, energy and industrial markets. ITT's three businesse ...

(ITT), Dow Chemical, and Firestone, all expropriated by Allende, returned to Chile. Pinochet's policies eventually led to substantial GDP growth, in contrast to the negative growth seen in the early years of his administration, while public debt also was kept high mostly to finance public spending which even after the privatization of services was kept at high rates (though far less than before privatization), for example, in 1991 after one year of post-Pinochet democracy debt was still at 37.4% of the GDP.

The Pinochet government implemented an economic model that had three main objectives: economic liberalization, privatization of state owned companies, and stabilization of inflation. In 1985, the government initiated a second round of privatization, revising previously introduced tariff increases and creating a greater supervisory role for the Central Bank. Pinochet's market liberalizations have continued after his death, led by Patricio Aylwin

Patricio Aylwin Azócar (; 26 November 1918 – 19 April 2016) was a Chilean politician from the Christian Democratic Party, lawyer, author, professor and former senator. He was the first president of Chile after dictator Augusto Pinochet, a ...

. According to a 2020 study in the ''Journal of Economic History'', Pinochet sold firms at below-market prices to politically connected buyers.

Critics argue the neoliberal economic policies of the Pinochet regime resulted in widening inequality

Inequality may refer to:

Economics

* Attention inequality, unequal distribution of attention across users, groups of people, issues in etc. in attention economy

* Economic inequality, difference in economic well-being between population groups

* ...

and deepening poverty as they negatively impacted the wages, benefits and working conditions of Chile's working class. According to Chilean economist Alejandro Foxley

Alejandro Tomás Foxley Rioseco (born 26 May 1939 in Viña del Mar) is a Chilean economist and politician. He was the Foreign Minister of Chile from 2006 to 2009 and previously served as Minister of Finance from 1990 to 1994 and leader of the ...

, by the end of Pinochet's reign around 44% of Chilean families were living below the poverty line. According to ''The Shock Doctrine

''The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism'' is a 2007 book by the Canadian author and social activist Naomi Klein. In the book, Klein argues that neoliberal free market policies (as advocated by the economist Milton Friedman) have ri ...

'' by Naomi Klein

Naomi A. Klein (born May 8, 1970) is a Canadian author, social activist, and filmmaker known for her political analyses, support of ecofeminism, organized labour, left-wing politics and criticism of corporate globalization, fascism, ecofascism ...

, by the late 1980s, the economy had stabilized and was growing, but around 45% of the population had fallen into poverty while the wealthiest 10% saw their incomes rise by 83%. But others disagree, Chilean economist José Piñera

José Piñera Echenique (born October 6, 1948) is a Chilean economist, one of the famous Chicago Boys, who served as minister of Labor and Social Security, and of Mining, in the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. He is the architect of Ch ...

argues that 2 years after Pinochet took power, poverty was still at 50% and the liberal reforms reduced it to 7.8% in 2013 as well as income per capita rising from US$4.000 in 1975 to US$25.000 in 2015, supporters of the reforms also argue that when Pinochet left power in 1990 poverty had fallen to 38% and some claim that since the consolidation of the neoliberal system inequality has been reducing. However, protests erupted in late 2019 in response to growing inequality in the country which can be traced back to the neoliberal policies of the Pinochet dictatorship.

American scholar Nancy MacLean, wrote that the concentration of money in the hands of the very rich and the perversion of democracy through the privatization of government was always the goal. She contends this was the effective meaning of the theoretical model known as public choice

Public choice, or public choice theory, is "the use of economic tools to deal with traditional problems of political science". Gordon Tullock, 9872008, "public choice," ''The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics''. . Its content includes the s ...

, whose architect James M. Buchanan

James McGill Buchanan Jr. (; October 3, 1919 – January 9, 2013) was an American economist known for his work on public choice theory originally outlined in his most famous work co-authored with Gordon Tullock in 1962, ''The Calculus of Consen ...

, traveled to Chile and worked closely with the Pinochet regime. MacLean's account, however, has come under scrutiny. Economist Andrew Farrant examined the Chilean constitutional clauses that MacLean attributes to Buchanan, and discovered that they pre-dated his visit. He concludes that "evidence suggests that Buchanan's May 1980 visit did not particularly influence the subsequent drafting of the Chilean Constitution" and "there is no evidence to suggest that Buchanan had any kind of audience with Pinochet or corresponded with the Chilean dictator."

1988 referendum, attempt to stay in power and transition to democracy

According to the transitional provisions of the 1980 Constitution, a referendum was scheduled for 5 October 1988, to vote on a new eight-year presidential term for Pinochet. Confronted with increasing opposition, notably at the international level, Pinochet legalized political parties in 1987 and called for a vote to determine whether or not he would remain in power until 1997. If the "YES" won, Pinochet would have to implement the dispositions of the 1980 Constitution, mainly the call for general elections, while he would himself remain in power as president. If the "NO" won, Pinochet would remain President for another year, and a joint Presidential and legislative election would be held. Another reason for Pinochet's decision to call for elections was the April 1987 visit ofPope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

to Chile. According to the US Catholic author George Weigel

George Weigel (born 1951) is a Catholic neoconservative American author, political analyst, and social activist. He currently serves as a Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. Weigel was the Founding President of the ...

, he held a meeting with Pinochet during which they discussed a return to democracy. John Paul II allegedly pushed Pinochet to accept a democratic opening of his government, and even called for his resignation.

Political advertising was legalized on 5 September 1987, as a necessary element for the campaign for the "NO" to the referendum, which countered the official campaign, which presaged a return to a Popular Unity government in case of a defeat of Pinochet. The Opposition, gathered into the '' Concertación de Partidos por el NO'' ("Coalition of Parties for NO"), organized a colorful and cheerful campaign under the slogan '' La alegría ya viene'' ("Joy is coming"). It was formed by the Christian Democracy, the

Political advertising was legalized on 5 September 1987, as a necessary element for the campaign for the "NO" to the referendum, which countered the official campaign, which presaged a return to a Popular Unity government in case of a defeat of Pinochet. The Opposition, gathered into the '' Concertación de Partidos por el NO'' ("Coalition of Parties for NO"), organized a colorful and cheerful campaign under the slogan '' La alegría ya viene'' ("Joy is coming"). It was formed by the Christian Democracy, the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

and the Radical Party, gathered in the ''Alianza Democrática'' (Democratic Alliance). In 1988, several more parties, including the Humanist Party

The Humanist International (also known as the International Humanist Party) is a consortium of political parties adhering to universal humanism (also known as Siloism, after the nickname of the movement's founder), founded in 1989 by over 40 na ...

, the Ecologist Party, the Social Democrats, and several Socialist Party splinter groups added their support.

On 5 October 1988, the "NO" option won with 55.99%Tribunal CalificadorChilean governmental website of the votes, against 44.01% of "YES" votes. In the wake of his electoral defeat, Pinochet attempted to implement a plan for an auto-coup. He attempted to implement efforts to orchestrate chaos and violence in the streets to justify his power grab, however, the Carabinero police refused an order to lift the cordon against street demonstrations in the capital, according to a CIA informant. In his final move, Pinochet convened a meeting of his junta at

La Moneda

Palacio de La Moneda (, ''Palace of the Mint''), or simply La Moneda, is the seat of the President of the Republic of Chile. It also houses the offices of three cabinet ministers: Interior, General Secretariat of the Presidency and General Secre ...

, in which he requested that they give him extraordinary powers to have the military seize the capital. Air Force General Fernando Matthei

Fernando Matthei Aubel (11 July 1925 – 19 November 2017) was a Chilean Air Force general who was part of the military junta that ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, replacing the dismissed Gustavo Leigh as commander-in-chief of the Chilean Air ...

refused, saying that he would not agree to such a thing under any circumstances, and the rest of the junta followed this stance, on grounds that Pinochet already had his turn and lost. Matthei would later become the first member of the junta to publicly admit that Pinochet had lost the plebiscite. Without any support from the junta, Pinochet was forced to accept the result. The ensuing Constitutional process led to presidential and legislative elections the following year.

The Coalition changed its name to ''Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia'' (Coalition of Parties for Democracy) and put forward Patricio Aylwin

Patricio Aylwin Azócar (; 26 November 1918 – 19 April 2016) was a Chilean politician from the Christian Democratic Party, lawyer, author, professor and former senator. He was the first president of Chile after dictator Augusto Pinochet, a ...

, a Christian Democrat who had opposed Allende, as presidential candidate, and also proposed a list of candidates for the parliamentary elections. The opposition and the Pinochet government made several negotiations to amend the Constitution and agreed to 54 modifications. These amendments changed the way the Constitution would be modified in the future, added restrictions to state of emergency dispositions, the affirmation of political pluralism, and enhanced constitutional rights as well as the democratic principle and participation to political life. In July 1989, a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

on the proposed changes took place, supported by all the parties except the right-wing Southern Party

The Southern Party (SP) was a minor political party in the United States that operated exclusively in the South. The party supported states' rights and increased Southern cultural and regionalist activism.

The party was formed by the League o ...

and the Chilean Socialist Party. The Constitutional changes were approved by 91.25% of the voters.

Thereafter, Aylwin won the December 1989 presidential election with 55% of the votes, against less than 30% for the right-wing candidate,

Thereafter, Aylwin won the December 1989 presidential election with 55% of the votes, against less than 30% for the right-wing candidate, Hernán Büchi

Hernán Alberto Büchi Buc (; born March 6, 1949) is a Chilean economist who served as minister of finance of the Pinochet government. In 1989 he ran unsuccessfully for president with support of Chilean right-wing parties.

Early life

Büchi wa ...

, who had been Pinochet's Minister of Finances A ministry of finance is a part of the government in most countries that is responsible for matters related to the finance.

Lists of current ministries of finance

Named "Ministry"

* Ministry of Finance (Afghanistan)

* Ministry of Finance and Ec ...

since 1985 (there was also a third-party candidate, Francisco Javier Errázuriz, a wealthy aristocrat representing the extreme economic right, who garnered the remaining 15%). Pinochet thus left the presidency on 11 March 1990 and transferred power to the new democratically elected president.

The ''Concertación'' also won the majority of votes for the Parliament. However, due to the "binomial" representation system included in the constitution, the elected senators did not achieve a complete majority in Parliament, a situation that would last for over 15 years. This forced them to negotiate all law projects with the Alliance for Chile