Opabinia BW2.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Opabinia regalis'' is an extinct,

Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita and Merostomata

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 57: 145-228. The generic name is derived from Opabin pass between Mount Hungabee and Mount Biddle, southeast of Lake O'Hara, British Columbia, Canada. In 1966–1967, Harry B. Whittington found another good specimen, and in 1975 he published a detailed description based on very thorough dissection of some specimens and photographs of these specimens lit from a variety of angles. Whittington's analysis did not cover ''Opabinia? media'': Walcott's specimens of this species could not be identified in his collection. In 1960 Russian paleontologists described specimens they found in the Norilsky region of Siberia and labelled ''Opabinia norilica'', but these fossils were poorly preserved, and Whittington did not feel they provided enough information to be classified as members of the genus ''Opabinia''.

File:20191108 Opabinia regalis.png, Restoration

File:20210222 Opabinia size.png, Size estimation

''Opabinia'' looked so strange that the audience at the first presentation of Whittington's analysis laughed. The length of ''Opabinia regalis'' from head (excluding proboscis) to tail end ranged between and . One of the most distinctive characters of ''Opabinia'' is the hollow proboscis, whose total length was about one-third of the body's and projected down from under the head. The proboscis was :wikt:striated, striated like a vacuum cleaner's hose and flexible, and it ended with a claw-like structure whose terminal edges bore 5 spines that projected inwards and forwards. The bilateral symmetry and lateral (instead of vertical as reconstructed by Whittington 1975) arrangement of the claw suggest it represent a pair of fused frontal appendages, comparable to those of Radiodonta, radiodonts and Lobopodia#Gilled lobopodians, gilled lobopodians. The head bore five stalked eyes: two near the front and fairly close to the middle of the head, pointing upwards and forwards; two larger eyes with longer stalks near the rear and outer edges of the head, pointing upwards and sideways; and a single eye between the larger pair of stalked eyes, pointing upwards. It has been assumed that the eyes were all compound eye, compound, like other

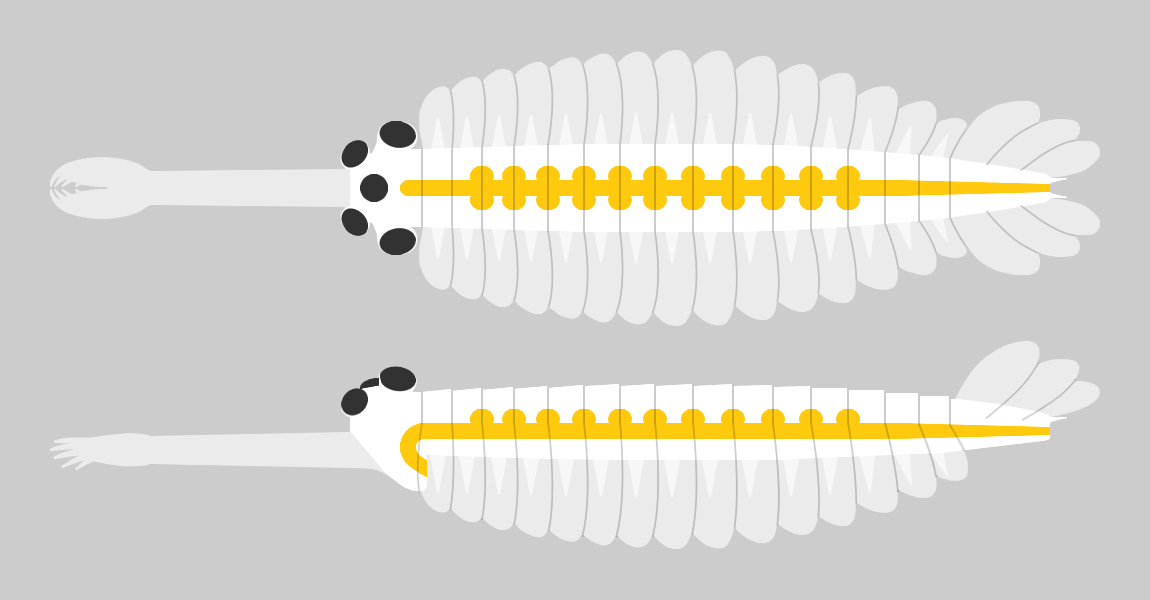

File:20210809 Opabinia regalis flap gill interpretation.png, Various interpretations on the flap and gill structures of ''Opabinia regalis''

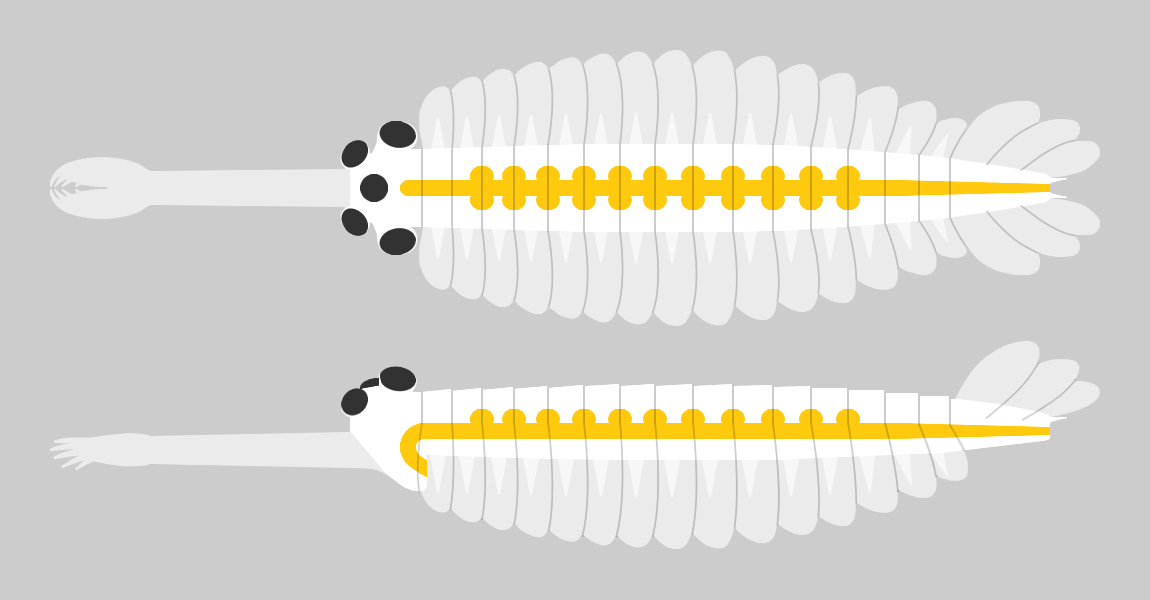

A: Whittington (1975), B: Bergström (1986), C: Budd (1996), D: Zhang & Briggs (2007), E: Budd & Daley (2011) File:20210807 Opabinia regalis trunk cross section.png, ''Opabinia'' cross-section based on Budd and Daley (2011)

Interpretations of other features of ''Opabinia'' fossils differ. Since the animals did not have biomineralization, mineralized armor nor even tough organic exoskeletons like those of other arthropods, their bodies were flattened as they were buried and fossilized, and smaller or internal features appear as markings within the outlines of the fossils.

Whittington (1975) interpreted the gills as paired extensions attached dorsally to the bases of all but the first flaps on each side, and thought that these gills were flat underneath, had overlapping layers on top. Bergström (1986) revealed the "overlapping layes" were rows of individual blades, interpreted the flaps as part of dorsal coverings (tergite) over the upper surface of the body, with blades attached underneath each of them. Graham Budd, Budd (1996) thought the gill blades attached along the front edges on the dorsal side of all except the first flaps. He also found marks inside the flaps' front edges that he interpreted as internal channels connecting the gills to the interior of the body, much as Whittington interpreted the mark along the proboscis as an internal channel. Zhang and Derek Briggs, Briggs (2007) however, interpreted all flaps have posterior spacing where the gill blades attached. Budd and Daley (2011) reject the reconstruction by Zhang & Briggs, showing the flaps have complete posteroir edges as previous reconstructions. They mostly follow the reconstruction by Budd (1996) with modifications on some details (e.g. the first flap pair also have gills; the attachment point of gill blades located more posteriorly than previously though). Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (diverticula). Chen ''et al.'' (1994) interpreted them as contained within the lobes along the sides. Budd (1996) thought the "triangles" were too wide to fit within ''Opabinia''s slender body, and that Cross section (geometry), cross-section views showed they were attached separately from and lower than the lobes, and extended below the body. He later found specimens that appeared to preserve the legs' exterior cuticle. He therefore interpreted the "triangles" as short, fleshy, conical legs (lobopods). He also found small mineralized patches at the tips of some, and interpreted these as claws. Under this reconstruction, the gill-bearing flap and lobopod were homologized to the outer gill branch and inner leg branch of arthropod biramous limbs seen in ''Marrella'', trilobites and crustaceans. Zhang and Briggs (2007) analyzed the chemical composition of the "triangles", and concluded that they had the same composition as the gut, and therefore agreed with Whittington that they were part of the digestive system. Instead they regarded ''Opabinia''s lobe+gill arrangement as an early form of the arthropod limbs before it split into a biramous structure. However, this similar chemical composition is not only associated with the digestive tract; Budd and Daley (2011) suggest that it represents mineralization forming within fluid-filled cavities within the body, which is consistent with hollow lobopods as seen in unequivocal lobopodian fossils. They also clarify that the gut diverticula of ''Opabinia'' are series of circular gut glands individualized from the "triangles". While they agreed on the absence of terminal claws, the presence of lobopods in ''Opabinia'' remain as a plausible interpretation.

Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (diverticula). Chen ''et al.'' (1994) interpreted them as contained within the lobes along the sides. Budd (1996) thought the "triangles" were too wide to fit within ''Opabinia''s slender body, and that Cross section (geometry), cross-section views showed they were attached separately from and lower than the lobes, and extended below the body. He later found specimens that appeared to preserve the legs' exterior cuticle. He therefore interpreted the "triangles" as short, fleshy, conical legs (lobopods). He also found small mineralized patches at the tips of some, and interpreted these as claws. Under this reconstruction, the gill-bearing flap and lobopod were homologized to the outer gill branch and inner leg branch of arthropod biramous limbs seen in ''Marrella'', trilobites and crustaceans. Zhang and Briggs (2007) analyzed the chemical composition of the "triangles", and concluded that they had the same composition as the gut, and therefore agreed with Whittington that they were part of the digestive system. Instead they regarded ''Opabinia''s lobe+gill arrangement as an early form of the arthropod limbs before it split into a biramous structure. However, this similar chemical composition is not only associated with the digestive tract; Budd and Daley (2011) suggest that it represents mineralization forming within fluid-filled cavities within the body, which is consistent with hollow lobopods as seen in unequivocal lobopodian fossils. They also clarify that the gut diverticula of ''Opabinia'' are series of circular gut glands individualized from the "triangles". While they agreed on the absence of terminal claws, the presence of lobopods in ''Opabinia'' remain as a plausible interpretation.

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of animals. Preston Cloud argued in 1948 and 1968 that the process was "explosive", and in the early 1970s Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould developed their theory of punctuated equilibrium, which views evolution as long intervals of near-stasis "punctuated" by short periods of rapid change. On the other hand, around the same time Wyatt Durham and Martin Glaessner both argued that the animal kingdom had a long Proterozoic history that was hidden by the lack of fossils. Whittington (1975) concluded that ''Opabinia'', and other taxa such as ''Marrella'' and ''Yohoia'', cannot be accommodated in modern groups. This was one of the primary reasons why Gould in his book on the

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of animals. Preston Cloud argued in 1948 and 1968 that the process was "explosive", and in the early 1970s Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould developed their theory of punctuated equilibrium, which views evolution as long intervals of near-stasis "punctuated" by short periods of rapid change. On the other hand, around the same time Wyatt Durham and Martin Glaessner both argued that the animal kingdom had a long Proterozoic history that was hidden by the lack of fossils. Whittington (1975) concluded that ''Opabinia'', and other taxa such as ''Marrella'' and ''Yohoia'', cannot be accommodated in modern groups. This was one of the primary reasons why Gould in his book on the  While this discussion about specific fossils such as ''Opabinia'' and ''Anomalocaris'' was going on in late 20 century, the concept of

While this discussion about specific fossils such as ''Opabinia'' and ''Anomalocaris'' was going on in late 20 century, the concept of

Smithsonian page on ''Opabinia'', with photo of Burgess Shale fossil

{{Taxonbar, from=Q50570 Dinocarida Cambrian arthropods Burgess Shale fossils Arthropod enigmatic taxa Taxa named by Charles Doolittle Walcott Fossil taxa described in 1912 Cambrian genus extinctions

stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

found in the Middle Cambrian

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ...

Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fo ...

Lagerstätte (505 million years ago) of British Columbia. ''Opabinia'' was a soft-bodied animal, measuring up to 7 cm in body length, and its segmented trunk had flaps along the sides and a fan-shaped tail. The head shows unusual features: five eyes, a mouth under the head and facing backwards, and a clawed proboscis that probably passed food to the mouth. ''Opabinia'' probably lived on the seafloor, using the proboscis to seek out small, soft food. Free abstract at Fewer than twenty good specimens have been described; 3 specimens of ''Opabinia'' are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they constitute less than 0.1% of the community.

When the first thorough examination of ''Opabinia'' in 1975 revealed its unusual features, it was thought to be unrelated to any known phylum, or perhaps a relative of arthropod and annelid ancestors. However, later studies since late 1990s consistently support its affinity as a member of basal arthropods, alongside the closely-related Radiodonta, radiodonts (''Anomalocaris'' and relatives) and Lobopodia#Gilled lobopodians, gilled lobopodians (''Kerygmachela'' and ''Pambdelurion'').

In the 1970s, there was an ongoing debate about whether multicellular, multi-celled animals appeared suddenly during the Early Cambrian, in an event called the Cambrian explosion, or had arisen earlier but without leaving fossils. At first ''Opabinia'' was regarded as strong evidence for the "explosive" hypothesis. Later the discovery of a whole series of similar lobopodian animals, some with closer resemblances to arthropods, and the development of the idea of stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

s suggested that the Early Cambrian was a time of relatively fast evolution but one that could be understood without assuming any unique evolutionary processes.

History of discovery

In 1911, Charles Doolittle Walcott found in theBurgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fo ...

nine almost complete fossils of ''Opabinia regalis'' and a few of what he classified as ''Opabinia? media'', and published a description of all of these in 1912.WALCOTT, C. D. 1912Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita and Merostomata

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 57: 145-228. The generic name is derived from Opabin pass between Mount Hungabee and Mount Biddle, southeast of Lake O'Hara, British Columbia, Canada. In 1966–1967, Harry B. Whittington found another good specimen, and in 1975 he published a detailed description based on very thorough dissection of some specimens and photographs of these specimens lit from a variety of angles. Whittington's analysis did not cover ''Opabinia? media'': Walcott's specimens of this species could not be identified in his collection. In 1960 Russian paleontologists described specimens they found in the Norilsky region of Siberia and labelled ''Opabinia norilica'', but these fossils were poorly preserved, and Whittington did not feel they provided enough information to be classified as members of the genus ''Opabinia''.

Occurrence

All the recognized ''Opabinia'' specimens found so far come from the "Phyllopod bed" of the Burgess Shale, in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia. In 1997, Briggs and Nedin reported from South Australia Emu Bay Shale a new specimen of ''Myoscolex'' that was much better preserved than previous specimens, leading them to conclude that it was a close relative of ''Opabinia''—although this interpretation was later questioned by Dzik, who instead concluded that ''Myoscolex'' was an annelid worm.Morphology

arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s' lateral eyes, but this reconstruction, which is not backed up by any evidence, is "somewhat fanciful". The mouth was under the head, behind the proboscis, and pointed ''backwards'', so that the digestive tract formed a U-bend on its way towards the rear of the animal. The proboscis appeared sufficiently long and flexible to reach the mouth.

The main part of the body was typically about wide and had 15 segments, on each of which there were pairs of flaps (lobes) pointing downwards and outwards. The flaps overlapped so that the front of each was covered by the rear edge of the one ahead of it. The body ended with what looked like a single conical segment bearing three pairs of overlapping tail fan blades that pointed up and out, forming a tail like a V-shaped double fan.

A: Whittington (1975), B: Bergström (1986), C: Budd (1996), D: Zhang & Briggs (2007), E: Budd & Daley (2011) File:20210807 Opabinia regalis trunk cross section.png, ''Opabinia'' cross-section based on Budd and Daley (2011)

Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (diverticula). Chen ''et al.'' (1994) interpreted them as contained within the lobes along the sides. Budd (1996) thought the "triangles" were too wide to fit within ''Opabinia''s slender body, and that Cross section (geometry), cross-section views showed they were attached separately from and lower than the lobes, and extended below the body. He later found specimens that appeared to preserve the legs' exterior cuticle. He therefore interpreted the "triangles" as short, fleshy, conical legs (lobopods). He also found small mineralized patches at the tips of some, and interpreted these as claws. Under this reconstruction, the gill-bearing flap and lobopod were homologized to the outer gill branch and inner leg branch of arthropod biramous limbs seen in ''Marrella'', trilobites and crustaceans. Zhang and Briggs (2007) analyzed the chemical composition of the "triangles", and concluded that they had the same composition as the gut, and therefore agreed with Whittington that they were part of the digestive system. Instead they regarded ''Opabinia''s lobe+gill arrangement as an early form of the arthropod limbs before it split into a biramous structure. However, this similar chemical composition is not only associated with the digestive tract; Budd and Daley (2011) suggest that it represents mineralization forming within fluid-filled cavities within the body, which is consistent with hollow lobopods as seen in unequivocal lobopodian fossils. They also clarify that the gut diverticula of ''Opabinia'' are series of circular gut glands individualized from the "triangles". While they agreed on the absence of terminal claws, the presence of lobopods in ''Opabinia'' remain as a plausible interpretation.

Whittington (1975) found evidence of near-triangular features along the body, and concluded that they were internal structures, most likely sideways extensions of the gut (diverticula). Chen ''et al.'' (1994) interpreted them as contained within the lobes along the sides. Budd (1996) thought the "triangles" were too wide to fit within ''Opabinia''s slender body, and that Cross section (geometry), cross-section views showed they were attached separately from and lower than the lobes, and extended below the body. He later found specimens that appeared to preserve the legs' exterior cuticle. He therefore interpreted the "triangles" as short, fleshy, conical legs (lobopods). He also found small mineralized patches at the tips of some, and interpreted these as claws. Under this reconstruction, the gill-bearing flap and lobopod were homologized to the outer gill branch and inner leg branch of arthropod biramous limbs seen in ''Marrella'', trilobites and crustaceans. Zhang and Briggs (2007) analyzed the chemical composition of the "triangles", and concluded that they had the same composition as the gut, and therefore agreed with Whittington that they were part of the digestive system. Instead they regarded ''Opabinia''s lobe+gill arrangement as an early form of the arthropod limbs before it split into a biramous structure. However, this similar chemical composition is not only associated with the digestive tract; Budd and Daley (2011) suggest that it represents mineralization forming within fluid-filled cavities within the body, which is consistent with hollow lobopods as seen in unequivocal lobopodian fossils. They also clarify that the gut diverticula of ''Opabinia'' are series of circular gut glands individualized from the "triangles". While they agreed on the absence of terminal claws, the presence of lobopods in ''Opabinia'' remain as a plausible interpretation.

Lifestyle

The way in which theBurgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fo ...

animals were buried, by a mudslide or a sediment-laden current that acted as a sandstorm, suggests they lived on the surface of the seafloor. ''Opabinia'' probably used its proboscis to search the sediment for food particles and pass them to its mouth. Since there is no sign of anything that might function as jaws, its food was presumably small and soft. The paired gut diverticula may increase the efficiency of food digestion and intake of nutrition. Whittington (1975) believing that ''Opabinia'' had no legs, thought that it crawled on its lobes and that it could also have swum slowly by flapping the lobes, especially if it timed the movements to create a wave with the metachoral movement of its lobes. On the other hand, he thought the body was not flexible enough to allow fish-like undulations of the whole body.

Classification

Considering how paleontologists' reconstructions of ''Opabinia'' differ, it is not surprising that the animal's classification was highly debated during the 20th century. Charles Doolittle Walcott, the original wikt:describer, describer, considered it to be an anostracan crustacean in 1912. The idea was followed by G. Evelyn Hutchinson in 1930, providing the first reconstruction of ''Opabinia'' as an anostracan swimming upside down. Alberto Simonetta provided a new reconstruction of ''Opabinia'' in 1970 very different to those of Hutchinson's, with lots ofarthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

feature (e.g. Tergite, dorsal exoskeleton and jointed limbs) which are reminiscent of ''Yohoia'' and ''Leanchoilia''. Leif Størmer, following earlier work by Percy Raymond, thought that ''Opabinia'' belonged to the so-called "trilobitoids" (trilobites and similar taxa). After his thorough analysis Harry B. Whittington concluded that ''Opabinia'' was not arthropod in 1975, as he found no evidence for arthropodan jointed limbs, and nothing like the flexible, probably fluid-filled proboscis was known in arthropods. Although he left ''Opabinias classification above the Family (biology), family level open, the annulated but not articulated body and the unusual lateral flaps with gills persuaded him that it may have been a representative of the ancestral stock from the origin of annelids and arthropods, two distinct animal phyla (Lophotrochozoan and Ecdysozoan, respectively) which were still thought to be close relatives (united under Articulata hypothesis, Articulata) at that time.

In 1985, Derek Briggs and Whittington published a major redescription of ''Anomalocaris'', also from the Burgess Shale. Soon after that, Swedish palaeontologist Jan Bergström in 1986 noted on the similarity of ''Anomalocaris'' and ''Opabinia'', suggested that the two animals were related, as they shared numerous features (e.g. lateral flaps, gill blades, stalked eyes and specialized frontal appendages). He classified them as primitive arthropods, although he considered that arthropods are not monophyletic, a single phylum.

In 1996, Graham Budd found what he considered evidence of short, un-jointed legs in ''Opabinia''. His examination of the gilled lobopodian ''Kerygmachela'' from the Sirius Passet lagerstätte, about and over 10M years older than the Burgess Shale, convinced him that this specimen had similar legs. He considered the legs of these two genus, genera very similar to those of the Burgess Shale lobopodian ''Aysheaia'' and the modern onychophorans (velvet worms), which are regarded as the bearers of numerous Plesiomorphy, ancestral traits shared by the ancestors with arthropods. After examining several sets of features shared by these and similar lobopodians he drew up a "broad-scale reconstruction of the arthropod stem group, stem-group", in other words of arthropods and what he considered to be their evolutionary basal members. One striking feature of this family tree is that modern tardigrada, tardigrades (water bears) may be ''Opabinia'Theoretical significance

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of animals. Preston Cloud argued in 1948 and 1968 that the process was "explosive", and in the early 1970s Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould developed their theory of punctuated equilibrium, which views evolution as long intervals of near-stasis "punctuated" by short periods of rapid change. On the other hand, around the same time Wyatt Durham and Martin Glaessner both argued that the animal kingdom had a long Proterozoic history that was hidden by the lack of fossils. Whittington (1975) concluded that ''Opabinia'', and other taxa such as ''Marrella'' and ''Yohoia'', cannot be accommodated in modern groups. This was one of the primary reasons why Gould in his book on the

''Opabinia'' made it clear how little was known about soft-bodied animals, which do not usually leave fossils. When Whittington described it in the mid-1970s, there was already a vigorous debate about the early evolution of animals. Preston Cloud argued in 1948 and 1968 that the process was "explosive", and in the early 1970s Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould developed their theory of punctuated equilibrium, which views evolution as long intervals of near-stasis "punctuated" by short periods of rapid change. On the other hand, around the same time Wyatt Durham and Martin Glaessner both argued that the animal kingdom had a long Proterozoic history that was hidden by the lack of fossils. Whittington (1975) concluded that ''Opabinia'', and other taxa such as ''Marrella'' and ''Yohoia'', cannot be accommodated in modern groups. This was one of the primary reasons why Gould in his book on the Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fo ...

, ''Wonderful Life (book), Wonderful Life'', considered that Early Cambrian life was much more diverse and "experimental" than any later set of animals and that the Cambrian explosion was a truly dramatic event, possibly driven by unusual evolutionary mechanisms. He regarded ''Opabinia'' as so important to understanding this phenomenon that he wanted to call his book ''Homage to Opabinia''.

However, other discoveries and analyses soon followed, revealing similar-looking animals such as ''Anomalocaris'' from the Burgess Shale and ''Kerygmachela'' from Sirius Passet. Another Burgess Shale animal, ''Aysheaia'', was considered very similar to modern Onychophora, which are regarded as close relatives of arthropods. Paleontologists defined a group called lobopodians to include fossil panarthropods that are thought to be close relatives of onychophorans, tardigrades and arthropods but lack jointed limbs. This group was later widely accepted as a paraphyletic grade that led to the origin of extant panarthropod phyla.

stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

s was introduced to cover evolutionary "aunts" and "cousins". A crown group is a group of closely related living animals plus their last common ancestor plus all its descendants. A stem group contains offshoots from members of the lineage earlier than the last common ancestor of the crown group; it is a ''relative'' concept, for example tardigrades are living animals that form a crown group in their own right, but Budd (1996) regarded them also as being a stem group relative to the arthropods. Viewing strange-looking organisms like ''Opabinia'' in this way makes it possible to see that, while the Cambrian explosion was unusual, it can be understood in terms of normal evolutionary processes.

See also

* *References

Further reading

* *External links

*Smithsonian page on ''Opabinia'', with photo of Burgess Shale fossil

{{Taxonbar, from=Q50570 Dinocarida Cambrian arthropods Burgess Shale fossils Arthropod enigmatic taxa Taxa named by Charles Doolittle Walcott Fossil taxa described in 1912 Cambrian genus extinctions