Lophelia pertusa.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

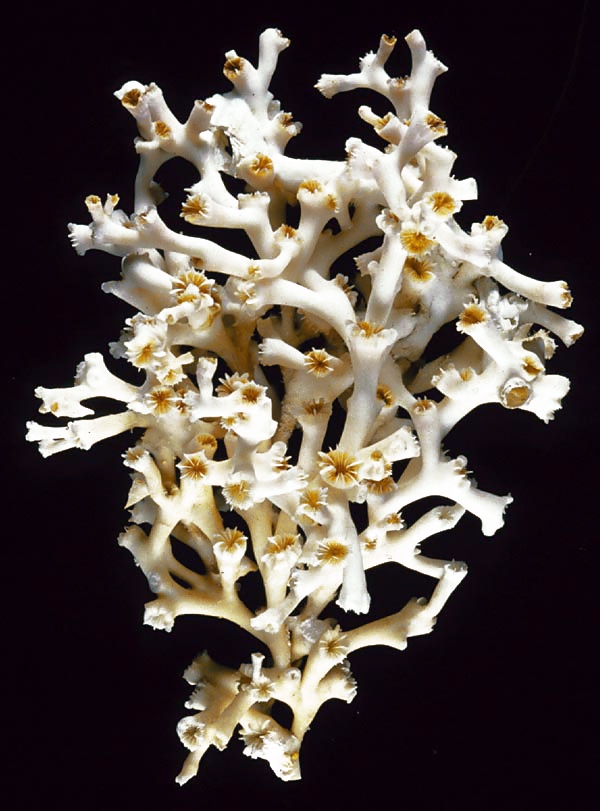

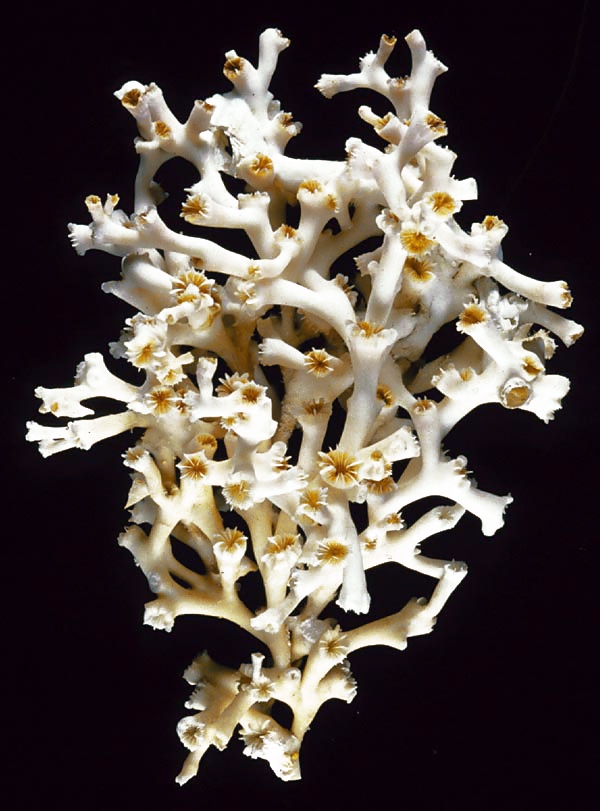

''Lophelia pertusa'', the only species in the genus ''Lophelia'', is a

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain  ''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef, Røst Reef, measures and lies at a depth of off the Lofoten Islands, Norway. When this is seen in terms of a growth rate of around 1 mm per year, the great age of these reefs becomes apparent.

Polyps at the end of branches feed by extending their tentacles and straining plankton from the seawater. They are able to ingest particles of up to 2 cm, and are able to discriminate between food and sediment using their chemoreceptors to differentiate between the two. Growth of polyps depends on environmental factors such as food availability, water quality, and how the water flows.

''L. pertusa'' are considered to be opportunistic feeders since they feed on particles of organic matter that have been broken down. Hence, the spring bloom of phytoplankton and subsequent zooplankton blooms provide the main source of nutrient input to the deep sea. This rain of dead plankton is visible on photographs of the seabed and stimulates a seasonal cycle of growth and reproduction in ''Lophelia''. This cycle is recorded in patterns of growth, and can be studied to investigate climate change, climatic variation in the recent past.

''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef, Røst Reef, measures and lies at a depth of off the Lofoten Islands, Norway. When this is seen in terms of a growth rate of around 1 mm per year, the great age of these reefs becomes apparent.

Polyps at the end of branches feed by extending their tentacles and straining plankton from the seawater. They are able to ingest particles of up to 2 cm, and are able to discriminate between food and sediment using their chemoreceptors to differentiate between the two. Growth of polyps depends on environmental factors such as food availability, water quality, and how the water flows.

''L. pertusa'' are considered to be opportunistic feeders since they feed on particles of organic matter that have been broken down. Hence, the spring bloom of phytoplankton and subsequent zooplankton blooms provide the main source of nutrient input to the deep sea. This rain of dead plankton is visible on photographs of the seabed and stimulates a seasonal cycle of growth and reproduction in ''Lophelia''. This cycle is recorded in patterns of growth, and can be studied to investigate climate change, climatic variation in the recent past.

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, the European Commission’s main scientific advisor on fisheries and environmental issues in the northeast Atlantic, recommend mapping and then closing all of Europe’s deep corals to fishing trawlers.

In 1999, the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries closed an area of at Sula, including the large reef, to bottom trawling. In 2000, an additional area closed, covering about . An area of about enclosing the Røst Reef closed to bottom trawling in 2002. Bottom trawling leads to siltation or sand deposition, which involves the disturbance of underlying sediments and nutrients. This harmful process destroys and decreases the growth of coral reefs, affecting the expansion of polyp budding.

In recent years, environmental organizations such as Greenpeace have argued that exploration for oil on the north west continental shelf slopes of Europe should be curtailed due to the possibility that is it damaging to the ''Lophelia'' reefs - conversely, ''Lophelia'' has recently been observed growing on the legs of oil installations, specifically the Brent Spar rig which Greenpeace campaigned to remove. At the time, the growth of ''L. pertusa'' on the legs of oil rigs was considered unusual, although recent studies have shown this to be a common occurrence, with 13 of 14 North Sea oil rigs examined having ''L. pertusa'' colonies. The authors of the original work suggested that it may be better to leave the lower parts of such structures in place— a suggestion opposed by Greenpeace campaigner Simon Reddy, who compared it to "[dumping] a car in a wood – moss would grow on it, and if I was lucky a bird may even nest in it. But this is not justification to fill our forests with disused cars".

Recovery of damaged ''L.pertusa'' will be a slow process not only due to its slow growth rate, but also due to its low rates of colonization and recolonization process. This is because even if ''L.pertusa'' produces a dispersive larva, a sediment free surface is required to initiate a new settlement. Moreover, excessive sedimentation and chemical contaminants will negatively impact the larvae, even when they are available in large numbers.

As ocean temperatures continue to rise due to global warming, climate change is another deadly factor that threatens the existence of ''L. pertusa''. Although ''L. pertusa'' can survive changes in oxygen levels during periods of hypoxia and anoxia, they are vulnerable to sudden temperature changes. These fluctuations in temperature affect their metabolic rate, which has detrimental consequences regarding their energy input and growth.

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, the European Commission’s main scientific advisor on fisheries and environmental issues in the northeast Atlantic, recommend mapping and then closing all of Europe’s deep corals to fishing trawlers.

In 1999, the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries closed an area of at Sula, including the large reef, to bottom trawling. In 2000, an additional area closed, covering about . An area of about enclosing the Røst Reef closed to bottom trawling in 2002. Bottom trawling leads to siltation or sand deposition, which involves the disturbance of underlying sediments and nutrients. This harmful process destroys and decreases the growth of coral reefs, affecting the expansion of polyp budding.

In recent years, environmental organizations such as Greenpeace have argued that exploration for oil on the north west continental shelf slopes of Europe should be curtailed due to the possibility that is it damaging to the ''Lophelia'' reefs - conversely, ''Lophelia'' has recently been observed growing on the legs of oil installations, specifically the Brent Spar rig which Greenpeace campaigned to remove. At the time, the growth of ''L. pertusa'' on the legs of oil rigs was considered unusual, although recent studies have shown this to be a common occurrence, with 13 of 14 North Sea oil rigs examined having ''L. pertusa'' colonies. The authors of the original work suggested that it may be better to leave the lower parts of such structures in place— a suggestion opposed by Greenpeace campaigner Simon Reddy, who compared it to "[dumping] a car in a wood – moss would grow on it, and if I was lucky a bird may even nest in it. But this is not justification to fill our forests with disused cars".

Recovery of damaged ''L.pertusa'' will be a slow process not only due to its slow growth rate, but also due to its low rates of colonization and recolonization process. This is because even if ''L.pertusa'' produces a dispersive larva, a sediment free surface is required to initiate a new settlement. Moreover, excessive sedimentation and chemical contaminants will negatively impact the larvae, even when they are available in large numbers.

As ocean temperatures continue to rise due to global warming, climate change is another deadly factor that threatens the existence of ''L. pertusa''. Although ''L. pertusa'' can survive changes in oxygen levels during periods of hypoxia and anoxia, they are vulnerable to sudden temperature changes. These fluctuations in temperature affect their metabolic rate, which has detrimental consequences regarding their energy input and growth.

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that conger eels, sharks, groupers, hake and the invertebrate community consisting of brittle stars, molluscs, Amphipoda, amphipods and crabs reside on these beds. High densities of smaller fish such as Marine hatchetfish, hatchetfish and lanternfish have been recorded in the waters over ''Lophelia'' beds, indicating they may be important prey items for the larger fish below.

''L. pertusa'' also forms a symbiosis with polychaete ''Eunice norvegica.'' It is suggested that ''E. norvegica'' positively influences ''L.pertusa'' by forming connecting tubes, which are later calcified, in order to strengthen the reef frameworks. While ''E. norvegica'' requires partial consumption of the food obtained by ''L. pertusa'', ''E. norvegica'' aids in cleaning the living coral framework and protecting it from potential predators.

Foraminiferan

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that conger eels, sharks, groupers, hake and the invertebrate community consisting of brittle stars, molluscs, Amphipoda, amphipods and crabs reside on these beds. High densities of smaller fish such as Marine hatchetfish, hatchetfish and lanternfish have been recorded in the waters over ''Lophelia'' beds, indicating they may be important prey items for the larger fish below.

''L. pertusa'' also forms a symbiosis with polychaete ''Eunice norvegica.'' It is suggested that ''E. norvegica'' positively influences ''L.pertusa'' by forming connecting tubes, which are later calcified, in order to strengthen the reef frameworks. While ''E. norvegica'' requires partial consumption of the food obtained by ''L. pertusa'', ''E. norvegica'' aids in cleaning the living coral framework and protecting it from potential predators.

Foraminiferan

Lophelia.org - Cold-water coral resource

{{Taxonbar, from1=Q1869773, from2=Q2703346 Caryophylliidae Monotypic cnidarian genera Corals described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Taxa named by Henri Milne-Edwards Taxa named by Jules Haime

cold-water coral

The habitat of deep-water corals, also known as cold-water corals, extends to deeper, darker parts of the oceans than tropical corals, ranging from near the surface to the abyss, beyond where water temperatures may be as cold as . Deep-water co ...

that grows in the deep waters throughout the North Atlantic ocean, as well as parts of the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

and Alboran Sea. Although ''L. pertusa'' reefs are home to a diverse community, the species is extremely slow growing and may be harmed by destructive fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

practices, or oil exploration and extraction.

Biology

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain zooxanthella

Zooxanthellae is a colloquial term for single-celled dinoflagellates that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including demosponges, corals, jellyfish, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthellae are in the genus '' Sym ...

e, the symbiotic algae which lives inside most tropical reef building corals. ''Lophelia'' lives at a temperature range from about and at depths between and over , but most commonly at depths of , where there is no sunlight.

As a coral, it represents a colonial organism

In biology, a colony is composed of two or more conspecific individuals living in close association with, or connected to, one another. This association is usually for mutual benefit such as stronger defense or the ability to attack bigger prey.

...

, which consists of many individuals. New polyps

A polyp in zoology is one of two forms found in the phylum Cnidaria, the other being the medusa. Polyps are roughly cylindrical in shape and elongated at the axis of the vase-shaped body. In solitary polyps, the aboral (opposite to oral) end i ...

live and build upon the calcium carbonate skeletal remains of previous generations. Living coral ranges in colour from white to orange-red; each polyp has up to 16 tentacles and is a translucent pink, yellow or white. Unlike most tropical corals, the polyps are not interconnected by living tissue. Some colonies have larger polyps while others have small and delicate -looking ones. Radiocarbon dating indicates that some ''Lophelia'' reefs in the waters off North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

may be 40,000 years old, with individual living coral bushes as much as 1,000 years old.

The colony grows by the bud

In botany, a bud is an undeveloped or embryonic shoot and normally occurs in the axil of a leaf or at the tip of a stem. Once formed, a bud may remain for some time in a dormant condition, or it may form a shoot immediately. Buds may be spec ...

ding off of new polyps. Living polyps are present on the edges of dead coral and fragmentation of coral colonies provides one form of asexual reproduction. Each colony is either male or female and sexual reproduction occurs when these liberate sperm and oocyte

An oocyte (, ), oöcyte, or ovocyte is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The femal ...

s into the sea. The larvae do not have a feeding stage, but sustain themselves on their yolks and drift with the plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

, possibly for several weeks. When settling on the seabed, they undergo metamorphosis and develop into polyps, which then potentially start new colonies.

''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef, Røst Reef, measures and lies at a depth of off the Lofoten Islands, Norway. When this is seen in terms of a growth rate of around 1 mm per year, the great age of these reefs becomes apparent.

Polyps at the end of branches feed by extending their tentacles and straining plankton from the seawater. They are able to ingest particles of up to 2 cm, and are able to discriminate between food and sediment using their chemoreceptors to differentiate between the two. Growth of polyps depends on environmental factors such as food availability, water quality, and how the water flows.

''L. pertusa'' are considered to be opportunistic feeders since they feed on particles of organic matter that have been broken down. Hence, the spring bloom of phytoplankton and subsequent zooplankton blooms provide the main source of nutrient input to the deep sea. This rain of dead plankton is visible on photographs of the seabed and stimulates a seasonal cycle of growth and reproduction in ''Lophelia''. This cycle is recorded in patterns of growth, and can be studied to investigate climate change, climatic variation in the recent past.

''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef, Røst Reef, measures and lies at a depth of off the Lofoten Islands, Norway. When this is seen in terms of a growth rate of around 1 mm per year, the great age of these reefs becomes apparent.

Polyps at the end of branches feed by extending their tentacles and straining plankton from the seawater. They are able to ingest particles of up to 2 cm, and are able to discriminate between food and sediment using their chemoreceptors to differentiate between the two. Growth of polyps depends on environmental factors such as food availability, water quality, and how the water flows.

''L. pertusa'' are considered to be opportunistic feeders since they feed on particles of organic matter that have been broken down. Hence, the spring bloom of phytoplankton and subsequent zooplankton blooms provide the main source of nutrient input to the deep sea. This rain of dead plankton is visible on photographs of the seabed and stimulates a seasonal cycle of growth and reproduction in ''Lophelia''. This cycle is recorded in patterns of growth, and can be studied to investigate climate change, climatic variation in the recent past.

Conservation status

''L. pertusa'' was listed under CITES Appendix II in January 1990, meaning that the UNEP, United Nations Environmental Programme recognizes that this species is not necessarily currently threatened with extinction but that it may become so in the future. CITES is a means of restricting international trade in endangered species, which is not a major threat to the survival of ''L. pertusa''. The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic, OSPAR Commission for the protection of the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic have recognized ''Lophelia pertusa'' reefs as a threatened habitat in need of protection. Main threats come from destruction of reefs by heavy deep-sea trawl nets, targeting Sebastes, redfish or grenadier (fish), grenadiers. The heavy metal "doors", which hold the mouth of the net open, and the "footline", which is equipped with large metal "rollers", are dragged along the sea bed, and have a highly damaging effect on the coral. Because the rate of growth is so slow, it is unlikely that this practice will prove to be sustainable. Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, the European Commission’s main scientific advisor on fisheries and environmental issues in the northeast Atlantic, recommend mapping and then closing all of Europe’s deep corals to fishing trawlers.

In 1999, the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries closed an area of at Sula, including the large reef, to bottom trawling. In 2000, an additional area closed, covering about . An area of about enclosing the Røst Reef closed to bottom trawling in 2002. Bottom trawling leads to siltation or sand deposition, which involves the disturbance of underlying sediments and nutrients. This harmful process destroys and decreases the growth of coral reefs, affecting the expansion of polyp budding.

In recent years, environmental organizations such as Greenpeace have argued that exploration for oil on the north west continental shelf slopes of Europe should be curtailed due to the possibility that is it damaging to the ''Lophelia'' reefs - conversely, ''Lophelia'' has recently been observed growing on the legs of oil installations, specifically the Brent Spar rig which Greenpeace campaigned to remove. At the time, the growth of ''L. pertusa'' on the legs of oil rigs was considered unusual, although recent studies have shown this to be a common occurrence, with 13 of 14 North Sea oil rigs examined having ''L. pertusa'' colonies. The authors of the original work suggested that it may be better to leave the lower parts of such structures in place— a suggestion opposed by Greenpeace campaigner Simon Reddy, who compared it to "[dumping] a car in a wood – moss would grow on it, and if I was lucky a bird may even nest in it. But this is not justification to fill our forests with disused cars".

Recovery of damaged ''L.pertusa'' will be a slow process not only due to its slow growth rate, but also due to its low rates of colonization and recolonization process. This is because even if ''L.pertusa'' produces a dispersive larva, a sediment free surface is required to initiate a new settlement. Moreover, excessive sedimentation and chemical contaminants will negatively impact the larvae, even when they are available in large numbers.

As ocean temperatures continue to rise due to global warming, climate change is another deadly factor that threatens the existence of ''L. pertusa''. Although ''L. pertusa'' can survive changes in oxygen levels during periods of hypoxia and anoxia, they are vulnerable to sudden temperature changes. These fluctuations in temperature affect their metabolic rate, which has detrimental consequences regarding their energy input and growth.

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, the European Commission’s main scientific advisor on fisheries and environmental issues in the northeast Atlantic, recommend mapping and then closing all of Europe’s deep corals to fishing trawlers.

In 1999, the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries closed an area of at Sula, including the large reef, to bottom trawling. In 2000, an additional area closed, covering about . An area of about enclosing the Røst Reef closed to bottom trawling in 2002. Bottom trawling leads to siltation or sand deposition, which involves the disturbance of underlying sediments and nutrients. This harmful process destroys and decreases the growth of coral reefs, affecting the expansion of polyp budding.

In recent years, environmental organizations such as Greenpeace have argued that exploration for oil on the north west continental shelf slopes of Europe should be curtailed due to the possibility that is it damaging to the ''Lophelia'' reefs - conversely, ''Lophelia'' has recently been observed growing on the legs of oil installations, specifically the Brent Spar rig which Greenpeace campaigned to remove. At the time, the growth of ''L. pertusa'' on the legs of oil rigs was considered unusual, although recent studies have shown this to be a common occurrence, with 13 of 14 North Sea oil rigs examined having ''L. pertusa'' colonies. The authors of the original work suggested that it may be better to leave the lower parts of such structures in place— a suggestion opposed by Greenpeace campaigner Simon Reddy, who compared it to "[dumping] a car in a wood – moss would grow on it, and if I was lucky a bird may even nest in it. But this is not justification to fill our forests with disused cars".

Recovery of damaged ''L.pertusa'' will be a slow process not only due to its slow growth rate, but also due to its low rates of colonization and recolonization process. This is because even if ''L.pertusa'' produces a dispersive larva, a sediment free surface is required to initiate a new settlement. Moreover, excessive sedimentation and chemical contaminants will negatively impact the larvae, even when they are available in large numbers.

As ocean temperatures continue to rise due to global warming, climate change is another deadly factor that threatens the existence of ''L. pertusa''. Although ''L. pertusa'' can survive changes in oxygen levels during periods of hypoxia and anoxia, they are vulnerable to sudden temperature changes. These fluctuations in temperature affect their metabolic rate, which has detrimental consequences regarding their energy input and growth.

Ecological significance

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that conger eels, sharks, groupers, hake and the invertebrate community consisting of brittle stars, molluscs, Amphipoda, amphipods and crabs reside on these beds. High densities of smaller fish such as Marine hatchetfish, hatchetfish and lanternfish have been recorded in the waters over ''Lophelia'' beds, indicating they may be important prey items for the larger fish below.

''L. pertusa'' also forms a symbiosis with polychaete ''Eunice norvegica.'' It is suggested that ''E. norvegica'' positively influences ''L.pertusa'' by forming connecting tubes, which are later calcified, in order to strengthen the reef frameworks. While ''E. norvegica'' requires partial consumption of the food obtained by ''L. pertusa'', ''E. norvegica'' aids in cleaning the living coral framework and protecting it from potential predators.

Foraminiferan

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that conger eels, sharks, groupers, hake and the invertebrate community consisting of brittle stars, molluscs, Amphipoda, amphipods and crabs reside on these beds. High densities of smaller fish such as Marine hatchetfish, hatchetfish and lanternfish have been recorded in the waters over ''Lophelia'' beds, indicating they may be important prey items for the larger fish below.

''L. pertusa'' also forms a symbiosis with polychaete ''Eunice norvegica.'' It is suggested that ''E. norvegica'' positively influences ''L.pertusa'' by forming connecting tubes, which are later calcified, in order to strengthen the reef frameworks. While ''E. norvegica'' requires partial consumption of the food obtained by ''L. pertusa'', ''E. norvegica'' aids in cleaning the living coral framework and protecting it from potential predators.

ForaminiferanRange

''L. pertusa'' has been reported from Anguilla, Bahamas, Bermuda, Brazil, Canada, Cape Verde, Colombia, Cuba, Cyprus, Ecuador, Faroe Islands, France, French Southern Territories, Greece, Grenada, Iceland, India, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Madagascar, Mexico, Montserrat, Norway, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Saint Helena, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Senegal, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States of America, U.S. Virgin Islands and Wallis and Futuna Islands.As reported by CITES and the UNEP, and as such, is incomplete, and affected by development of marine science in that country, and effort put into surveying for it.References

External links

Lophelia.org - Cold-water coral resource

{{Taxonbar, from1=Q1869773, from2=Q2703346 Caryophylliidae Monotypic cnidarian genera Corals described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Taxa named by Henri Milne-Edwards Taxa named by Jules Haime