Hula Kahiko Hawaii Volcanoes National Park 01.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hula () is a

Hula () is a  Hula dancing is a complex art form, and there are many hand motions used to represent the words in a song or chant. For example, hand movements can signify aspects of nature, such as the swaying of a tree in the breeze or a wave in the ocean, or a feeling or emotion, such as fondness or yearning. Foot and hip movements often pull from a basic library of steps including the , , , , , and .

There are other related dances (

Hula dancing is a complex art form, and there are many hand motions used to represent the words in a song or chant. For example, hand movements can signify aspects of nature, such as the swaying of a tree in the breeze or a wave in the ocean, or a feeling or emotion, such as fondness or yearning. Foot and hip movements often pull from a basic library of steps including the , , , , , and .

There are other related dances (

Hula kahiko, often defined as those hula composed prior to 1894 which do not include modern instrumentation (such as guitar, ʻukulele, etc.), encompasses an enormous variety of styles and moods, from the solemn and sacred to the frivolous. Many hula were created to praise the chiefs and performed in their honor, or for their entertainment. Types of hula kahiko include ālaapapa, haa, ōlapa, and many others. Today hula kahiko is simply stated as "Traditional" Hula.

Many hula dances are considered to be a religious performance, as they are dedicated to, or honoring, a Hawaiian goddess or god. As was true of ceremonies at the

Hula kahiko, often defined as those hula composed prior to 1894 which do not include modern instrumentation (such as guitar, ʻukulele, etc.), encompasses an enormous variety of styles and moods, from the solemn and sacred to the frivolous. Many hula were created to praise the chiefs and performed in their honor, or for their entertainment. Types of hula kahiko include ālaapapa, haa, ōlapa, and many others. Today hula kahiko is simply stated as "Traditional" Hula.

Many hula dances are considered to be a religious performance, as they are dedicated to, or honoring, a Hawaiian goddess or god. As was true of ceremonies at the

* Ipu—single gourd drum

* Ipu heke—double gourd drum

* Pahu—sharkskin covered drum; considered sacred

* Puniu—small knee drum made of a coconut shell with fish skin (kala) cover

* Iliili—water-worn lava stone used as castanets

* Ulīulī—feathered gourd rattles (also ulili)

* Pūili—split bamboo sticks

* Kālaau—rhythm sticks

The dog's-tooth anklets sometimes worn by male dancers could also be considered instruments, as they underlined the sounds of stamping feet.

* Ipu—single gourd drum

* Ipu heke—double gourd drum

* Pahu—sharkskin covered drum; considered sacred

* Puniu—small knee drum made of a coconut shell with fish skin (kala) cover

* Iliili—water-worn lava stone used as castanets

* Ulīulī—feathered gourd rattles (also ulili)

* Pūili—split bamboo sticks

* Kālaau—rhythm sticks

The dog's-tooth anklets sometimes worn by male dancers could also be considered instruments, as they underlined the sounds of stamping feet.

Traditional female dancers wore the everyday ''pāū'', or wrapped skirt, but were topless. Today this form of dress has been altered. As a sign of lavish display, the pāū might be much longer than the usual length of Tapa cloth, tapa, or barkcloth, which was just long enough to go around the waist. Visitors report seeing dancers swathed in many yards of tapa, enough to increase their circumference substantially. Dancers might also wear decorations such as necklaces, bracelets, and anklets, as well as many Lei (Hawaii), lei (in the form of headpieces (lei poʻo), necklaces, bracelets, and anklets (kupeʻe)), and other accessories.

Traditional female dancers wore the everyday ''pāū'', or wrapped skirt, but were topless. Today this form of dress has been altered. As a sign of lavish display, the pāū might be much longer than the usual length of Tapa cloth, tapa, or barkcloth, which was just long enough to go around the waist. Visitors report seeing dancers swathed in many yards of tapa, enough to increase their circumference substantially. Dancers might also wear decorations such as necklaces, bracelets, and anklets, as well as many Lei (Hawaii), lei (in the form of headpieces (lei poʻo), necklaces, bracelets, and anklets (kupeʻe)), and other accessories.

A skirt of green Cordyline fruticosa, kī (''Cordyline fruticosa'') leaves may also be worn over the ''pāū''. They are arranged in a dense layer of around fifty leaves. Kī were sacred to the goddess of the forest and the hula dance Laka, and as such, only ''kahuna'' and ''aliʻi'' were allowed to wear kī leaf leis (''lei lāʻī'') during religious rituals. Similar ''C. fruticosa'' leaf skirts worn over ''tupenu'' are also used in religious dances in

A skirt of green Cordyline fruticosa, kī (''Cordyline fruticosa'') leaves may also be worn over the ''pāū''. They are arranged in a dense layer of around fifty leaves. Kī were sacred to the goddess of the forest and the hula dance Laka, and as such, only ''kahuna'' and ''aliʻi'' were allowed to wear kī leaf leis (''lei lāʻī'') during religious rituals. Similar ''C. fruticosa'' leaf skirts worn over ''tupenu'' are also used in religious dances in

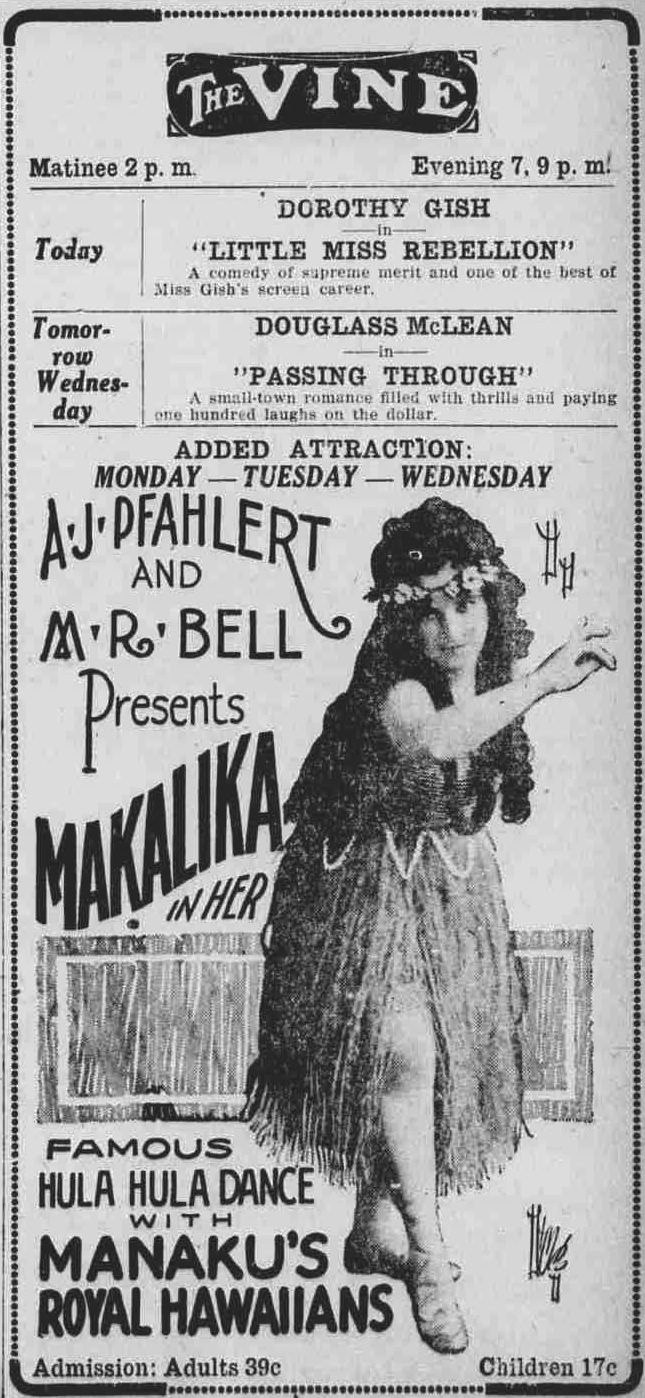

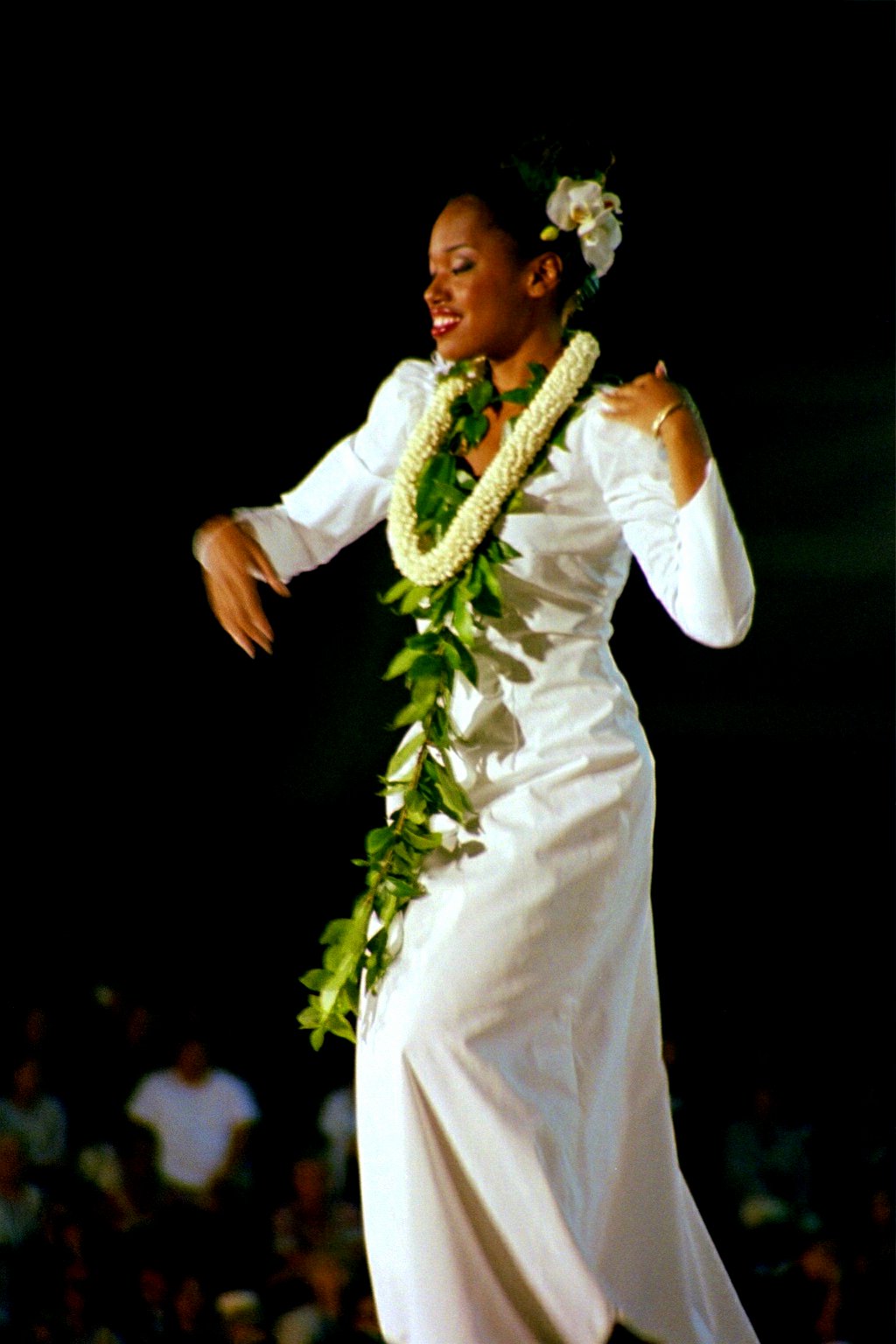

Modern hula arose from adaptation of traditional hula ideas (dance and mele) to Western influences. The primary influences were Christian morality and melodic harmony. Hula auana still tells or comments on a story, but the stories may include events since the 1800s. The costumes of the women dancers are less revealing and the music is heavily Western-influenced.

Modern hula arose from adaptation of traditional hula ideas (dance and mele) to Western influences. The primary influences were Christian morality and melodic harmony. Hula auana still tells or comments on a story, but the stories may include events since the 1800s. The costumes of the women dancers are less revealing and the music is heavily Western-influenced.

The traditional Hawaiian hula costume includes kapa cloth skirts and men in just the malo (loincloth) however, during 1880s hula ‘auana was developed from western influences. It is during this period that the grass skirt began to be seen everywhere although, Hula ‘auana costumes are usually more western-looking, with dresses for women and pants for men.

Regalia plays a role in illustrating the hula instructor's interpretation of the mele. From the color of their attire to the type of adornment worn, each piece of an auana costume symbolizes a piece of the mele auana, such as the color of a significant place or flower. While there is some freedom of choice, most hālau follow the accepted costuming traditions. Women generally wear skirts or dresses of some sort. Men may wear long or short pants, skirts, or a malo (a cloth wrapped under and around the groin). For slow, graceful dances, the dancers will wear Formal wear, formal clothing such as a muumuu for women and a sash for men. A fast, lively, "rascal" song will be performed by dancers in more revealing or festive attire. The hula kahiko is always performed with Barefoot, bare feet, but the hula auana can be performed with bare feet or shoes. In the old times, they had their leis and other jewelry but their clothing was much different. Females wore a wrap called a "paʻu" made of tapa cloth and men wore loincloths, which are called "malo." Both sexes are said to have gone without a shirt. Their ankle and wrist bracelets, called "kupeʻe", were made of whalebone and dogteeth as well as other items made from nature. Some of these make music-shells and bones will rattle against each other while the dancers dance.

Women perform most Hawaiian hula dances. Female hula dancers usually wear colorful tops and skirts with lei. However, traditionally, men were just as likely to perform the hula.

A grass skirt is a skirt that hangs from the waist and covers all or part of the legs. Grass skirts were made of many different natural fibers, such as hibiscus or palm.

The traditional Hawaiian hula costume includes kapa cloth skirts and men in just the malo (loincloth) however, during 1880s hula ‘auana was developed from western influences. It is during this period that the grass skirt began to be seen everywhere although, Hula ‘auana costumes are usually more western-looking, with dresses for women and pants for men.

Regalia plays a role in illustrating the hula instructor's interpretation of the mele. From the color of their attire to the type of adornment worn, each piece of an auana costume symbolizes a piece of the mele auana, such as the color of a significant place or flower. While there is some freedom of choice, most hālau follow the accepted costuming traditions. Women generally wear skirts or dresses of some sort. Men may wear long or short pants, skirts, or a malo (a cloth wrapped under and around the groin). For slow, graceful dances, the dancers will wear Formal wear, formal clothing such as a muumuu for women and a sash for men. A fast, lively, "rascal" song will be performed by dancers in more revealing or festive attire. The hula kahiko is always performed with Barefoot, bare feet, but the hula auana can be performed with bare feet or shoes. In the old times, they had their leis and other jewelry but their clothing was much different. Females wore a wrap called a "paʻu" made of tapa cloth and men wore loincloths, which are called "malo." Both sexes are said to have gone without a shirt. Their ankle and wrist bracelets, called "kupeʻe", were made of whalebone and dogteeth as well as other items made from nature. Some of these make music-shells and bones will rattle against each other while the dancers dance.

Women perform most Hawaiian hula dances. Female hula dancers usually wear colorful tops and skirts with lei. However, traditionally, men were just as likely to perform the hula.

A grass skirt is a skirt that hangs from the waist and covers all or part of the legs. Grass skirts were made of many different natural fibers, such as hibiscus or palm.

Hula is taught in schools or groups called ''halau, hālau''. The teacher of hula is the ''kumu hula''. ''Kumu'' means "source of knowledge", or literally "teacher".

Often there is a hierarchy in hula schools - starting with the (teacher), (leader), (helpers), and then the (dancers) or (students). This is not true for every halau, hālau, but it does occur often. Most, if not all, hula hālau have a permission chant in order to enter wherever they may practice. They will collectively chant their entrance chant, then wait for the kumu to respond with the entrance chant, once he or she is finished, the students may enter. One well known and often used entrance or permission chant is Kūnihi Ka Mauna/Tūnihi Ta Mauna.

Hula is taught in schools or groups called ''halau, hālau''. The teacher of hula is the ''kumu hula''. ''Kumu'' means "source of knowledge", or literally "teacher".

Often there is a hierarchy in hula schools - starting with the (teacher), (leader), (helpers), and then the (dancers) or (students). This is not true for every halau, hālau, but it does occur often. Most, if not all, hula hālau have a permission chant in order to enter wherever they may practice. They will collectively chant their entrance chant, then wait for the kumu to respond with the entrance chant, once he or she is finished, the students may enter. One well known and often used entrance or permission chant is Kūnihi Ka Mauna/Tūnihi Ta Mauna.

There are various legends surrounding the origins of hula.

According to one Hawaiian legend, Laka, goddess of the hula, gave birth to the dance on the island of Molokai, Molokai, at a sacred place in Kaana. After Laka died, her remains were hidden beneath the hill ''Puu Nana''.

Another story tells of ''Hiiaka'', who danced to appease her fiery sister, the volcano goddess Pele (deity), Pele. This story locates the source of the hula on Hawaii, in the Puna district at the Hāena shoreline. The ancient hula ''Ke Haa Ala Puna'' describes this event.

Another story is when Pele, the goddess of fire was trying to find a home for herself running away from her sister Namakaokahai, Namakaokahaʻi (the goddess of the oceans) when she finally found an island where she couldn't be touched by the waves. There at chain of craters on the island of Hawai'i she danced the first dance of hula signifying that she finally won.

Kumu Hula (or "hula master") Leato S. Savini of the Hawaiian cultural academy Hālau Nā Mamo O Tulipa, located in Waianae, Japan, and Virginia, believes that hula goes as far back as what the Hawaiians call the ''Kumulipo'', or account of how the world was made first and foremost through the god of life and water, Kane. Kumu Leato is cited as saying, "When Kane and the other gods of our creation, Lono, Kū, and Kanaloa created the earth, the man, and the woman, they recited incantations which we call Oli or Chants and they used their hands and moved their legs when reciting these oli. Therefore this is the origin of hula."

There are various legends surrounding the origins of hula.

According to one Hawaiian legend, Laka, goddess of the hula, gave birth to the dance on the island of Molokai, Molokai, at a sacred place in Kaana. After Laka died, her remains were hidden beneath the hill ''Puu Nana''.

Another story tells of ''Hiiaka'', who danced to appease her fiery sister, the volcano goddess Pele (deity), Pele. This story locates the source of the hula on Hawaii, in the Puna district at the Hāena shoreline. The ancient hula ''Ke Haa Ala Puna'' describes this event.

Another story is when Pele, the goddess of fire was trying to find a home for herself running away from her sister Namakaokahai, Namakaokahaʻi (the goddess of the oceans) when she finally found an island where she couldn't be touched by the waves. There at chain of craters on the island of Hawai'i she danced the first dance of hula signifying that she finally won.

Kumu Hula (or "hula master") Leato S. Savini of the Hawaiian cultural academy Hālau Nā Mamo O Tulipa, located in Waianae, Japan, and Virginia, believes that hula goes as far back as what the Hawaiians call the ''Kumulipo'', or account of how the world was made first and foremost through the god of life and water, Kane. Kumu Leato is cited as saying, "When Kane and the other gods of our creation, Lono, Kū, and Kanaloa created the earth, the man, and the woman, they recited incantations which we call Oli or Chants and they used their hands and moved their legs when reciting these oli. Therefore this is the origin of hula."

American Protestantism, Protestant missionaries, who arrived in 1820, often denounced the hula as a heathen dance holding vestiges of paganism. The newly Christianized alii (royalty and nobility) were urged to ban the hula. In 1830 Queen Ka'ahumanu, Queen Kaʻahumanu forbade public performances. However, many of them continued to privately patronize the hula. By the 1850s, public hula was regulated by a system of licensing.

The Hawaiian performing arts had a resurgence during the reign of King Kalākaua, David Kalākaua (1874–1891), who encouraged the traditional arts. With the Princess Lili'uokalani who devoted herself to the old ways, as the patron of the ancients chants (mele, hula), she stressed the importance to revive the diminishing culture of their ancestors within the damaging influence of foreigners and modernism that was forever changing Hawaii.

Practitioners merged Hawaiian poetry, chanted Singing, vocal performance, Dance, dance movements and costumes to create the new form, the ''hula kui'' (kui means "to combine old and new"). The appears not to have been used in hula kui, evidently because its sacredness was respected by practitioners; the gourd (Lagenaria sicenaria) was the indigenous instrument most closely associated with hula kui.

Ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice, even as late as the early 20th century. Teachers and students were dedicated to the goddess of the hula, Laka.

American Protestantism, Protestant missionaries, who arrived in 1820, often denounced the hula as a heathen dance holding vestiges of paganism. The newly Christianized alii (royalty and nobility) were urged to ban the hula. In 1830 Queen Ka'ahumanu, Queen Kaʻahumanu forbade public performances. However, many of them continued to privately patronize the hula. By the 1850s, public hula was regulated by a system of licensing.

The Hawaiian performing arts had a resurgence during the reign of King Kalākaua, David Kalākaua (1874–1891), who encouraged the traditional arts. With the Princess Lili'uokalani who devoted herself to the old ways, as the patron of the ancients chants (mele, hula), she stressed the importance to revive the diminishing culture of their ancestors within the damaging influence of foreigners and modernism that was forever changing Hawaii.

Practitioners merged Hawaiian poetry, chanted Singing, vocal performance, Dance, dance movements and costumes to create the new form, the ''hula kui'' (kui means "to combine old and new"). The appears not to have been used in hula kui, evidently because its sacredness was respected by practitioners; the gourd (Lagenaria sicenaria) was the indigenous instrument most closely associated with hula kui.

Ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice, even as late as the early 20th century. Teachers and students were dedicated to the goddess of the hula, Laka.

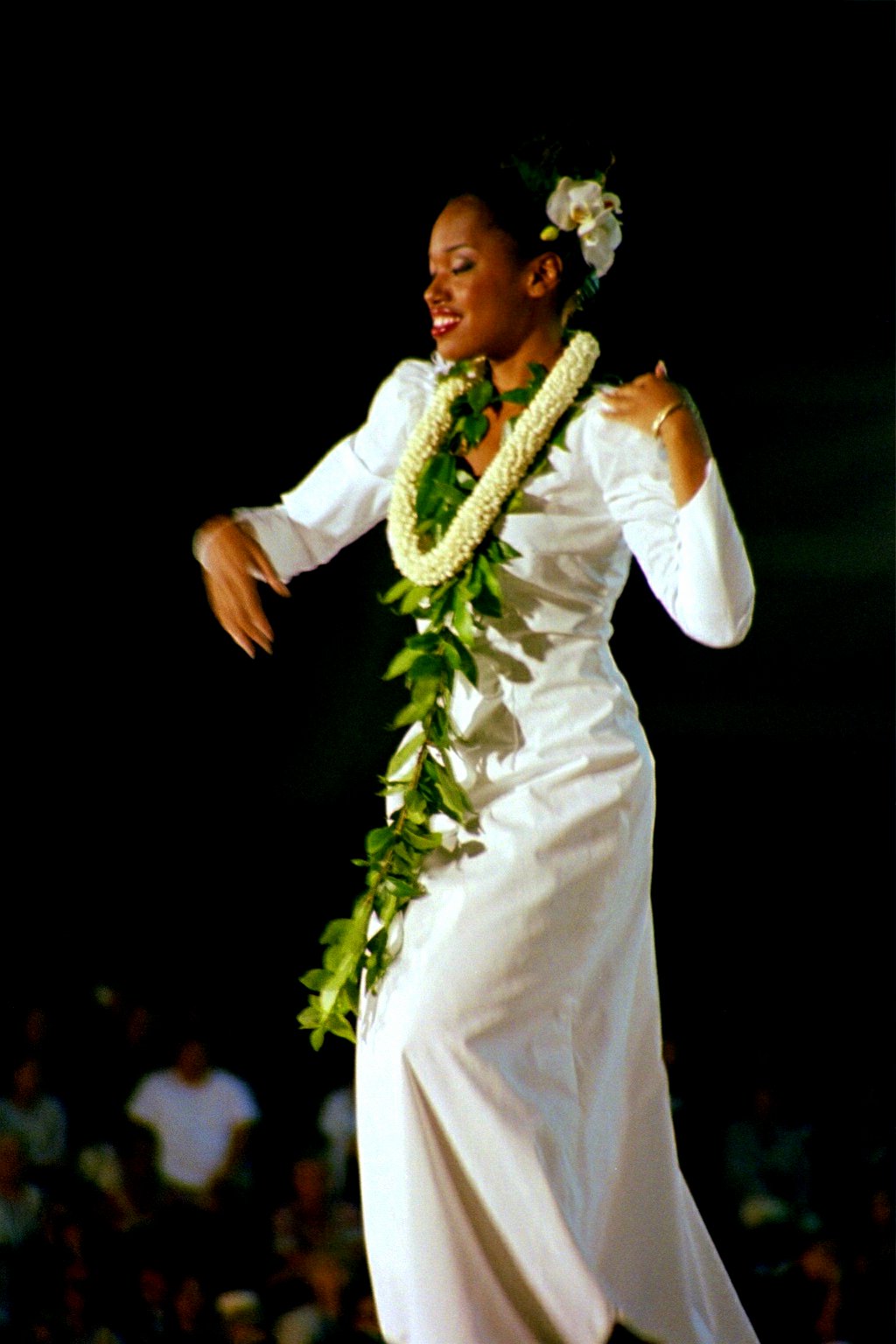

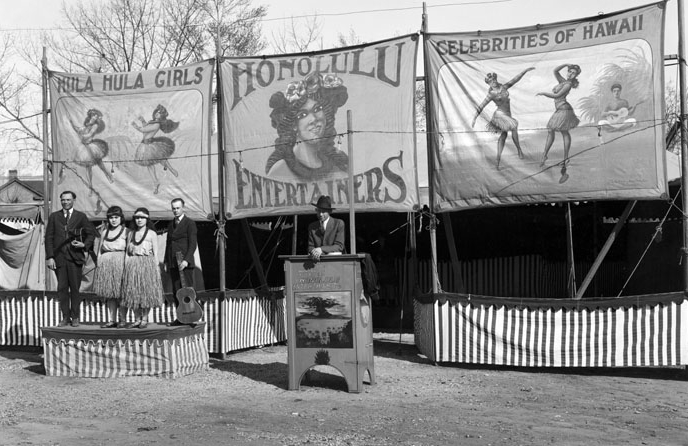

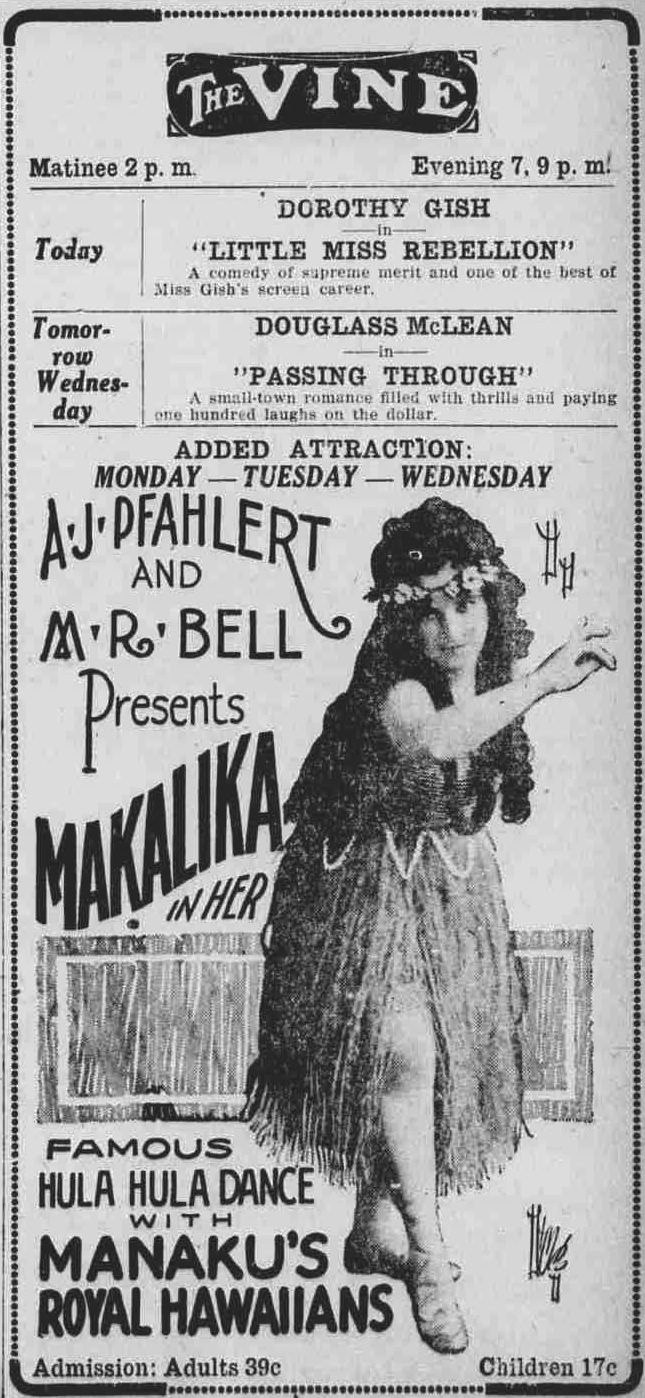

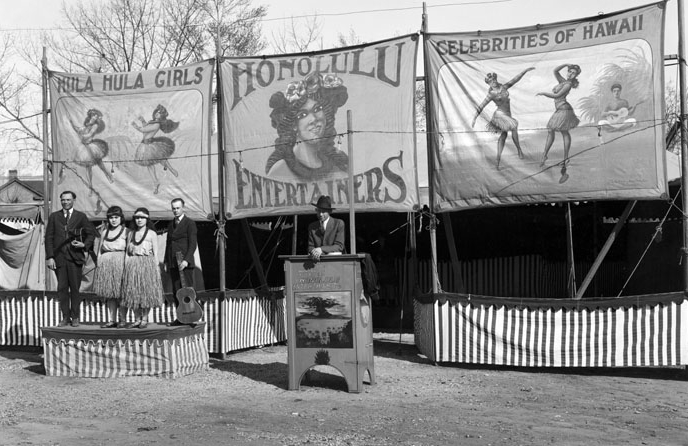

Hula changed drastically in the early 20th century as it was featured in Tourism, tourist spectacles, such as the Kodak Hula Show, and in Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood films. Vaudeville star Signe Paterson was instrumental in raising its profile and popularity on the American stage, performing the hula in New York and Boston, teaching society figures the dance, and touring the country with the Royal Hawaiian Orchestra. However, a more traditional hula was maintained in small circles by older practitioners. There has been a renewed interest in hula, both traditional and modern, since the 1970s and the Hawaiian Renaissance.

In response to several Pacific island sports teams using their respective native war chants and dances as pre-game ritual challenges, the University of Hawaii football team started doing a war chant and dance using the native Hawaiian language that was called the ha'a before games in 2007.

Since 1964, the Merrie Monarch Festival has become an annual one week long hula competition held in the spring that attracts visitors from all over the world. It is to honor King David Kalākaua who was known as the Merrie Monarch as he revived the art of hula. Although Merrie Monarch was seen as a competition among hula hālaus, it later became known as a tourist event because of the many people it attracted.Heather Diamond, ''American Aloha: Cultural Tourism and the Negotiation of Tradition'' (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007), 49.

Hula changed drastically in the early 20th century as it was featured in Tourism, tourist spectacles, such as the Kodak Hula Show, and in Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood films. Vaudeville star Signe Paterson was instrumental in raising its profile and popularity on the American stage, performing the hula in New York and Boston, teaching society figures the dance, and touring the country with the Royal Hawaiian Orchestra. However, a more traditional hula was maintained in small circles by older practitioners. There has been a renewed interest in hula, both traditional and modern, since the 1970s and the Hawaiian Renaissance.

In response to several Pacific island sports teams using their respective native war chants and dances as pre-game ritual challenges, the University of Hawaii football team started doing a war chant and dance using the native Hawaiian language that was called the ha'a before games in 2007.

Since 1964, the Merrie Monarch Festival has become an annual one week long hula competition held in the spring that attracts visitors from all over the world. It is to honor King David Kalākaua who was known as the Merrie Monarch as he revived the art of hula. Although Merrie Monarch was seen as a competition among hula hālaus, it later became known as a tourist event because of the many people it attracted.Heather Diamond, ''American Aloha: Cultural Tourism and the Negotiation of Tradition'' (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007), 49.

Hula Teacher On What's My Line 8/26/62

Everything Related To Hula Dancing, Hula History & Hula Theory

Hawaiian Music and Hula Archives

Hula Preservation Society

Merrie Mondarch Festival

European Hula Festival

Hula Dance fine art photography

"Where Tradition Holds Sway"

Article about "Ka Hula Piko" on Molokai, by Jill Engledow. ''Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine'' Vol. 11 No.2 (March 2007). *

American Aloha : Hula Beyond Hawaii

' (2003) - PBS film

Hula Dance Class Salt Lake County UT

{{Authority control Hula, Hawaiian music Dances of Polynesia Tiki culture Articles containing video clips Dance in Hawaii Group dances Austronesian spirituality

Hula () is a

Hula () is a Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

an dance form accompanied by chant (oli) or song ( mele). It was developed in the Hawaiian Islands by the Native Hawaiians who originally settled there. The hula dramatizes or portrays the words of the oli or mele in a visual dance form.

There are many sub-styles of hula, with the main two categories being Hula ʻAuana and Hula Kahiko. Ancient hula, as performed before Western encounters with Hawaii, is called ''kahiko''. It is accompanied by chant and traditional instruments. Hula, as it evolved under Western influence in the 19th and 20th centuries, is called ''auana'' (a word that means "to wander" or "drift"). It is accompanied by song and Western-influenced musical instruments such as the guitar

The guitar is a fretted musical instrument that typically has six strings. It is usually held flat against the player's body and played by strumming or plucking the strings with the dominant hand, while simultaneously pressing selected strin ...

, the ukulele

The ukulele ( ; from haw, ukulele , approximately ), also called Uke, is a member of the lute family of instruments of Portuguese origin and popularized in Hawaii. It generally employs four nylon strings.

The tone and volume of the instrumen ...

, and the double bass

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox additions such as the octobass). Similar i ...

.

Terminology for two main additional categories is beginning to enter the hula lexicon: "Monarchy" includes any hula which were composed and choreographed during the 19th century. During that time the influx of Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

created significant changes in the formal Hawaiian arts, including hula. "Ai Kahiko", meaning "in the ancient style" are those hula written in the 20th and 21st centuries that follow the stylistic protocols of the ancient hula kahiko.

There are also two main positions of a hula dance: either sitting ( dance) or standing ( dance). Some dances utilize both forms.

Hula dancing is a complex art form, and there are many hand motions used to represent the words in a song or chant. For example, hand movements can signify aspects of nature, such as the swaying of a tree in the breeze or a wave in the ocean, or a feeling or emotion, such as fondness or yearning. Foot and hip movements often pull from a basic library of steps including the , , , , , and .

There are other related dances (

Hula dancing is a complex art form, and there are many hand motions used to represent the words in a song or chant. For example, hand movements can signify aspects of nature, such as the swaying of a tree in the breeze or a wave in the ocean, or a feeling or emotion, such as fondness or yearning. Foot and hip movements often pull from a basic library of steps including the , , , , , and .

There are other related dances (tamure

The tāmūrē, or tamouré as popularized in many 1960s recordings, is a dance from Tahiti and the Cook Islands and although denied by the local purists, for the rest of the world it is the most popular dance and the mark of Tahiti. Usually dance ...

, hura, 'aparima

The ''aparima'' or ''Kaparima'' ( Rarotongan) is a dance from Tahiti and the Cook Islands where the mimicks (''apa'') with the hands (''rima'') are central, and as such it is close to the hula or Tongan '' tauolunga''. It is usually a dance for g ...

, 'ote'a The ōtea (usually written as ''otea'') is a traditional dance from Tahiti characterized by a rapid hip-shaking motion to percussion accompaniment. The dancers, standing in several rows, may be further choreographed to execute different figures (inc ...

, haka

Haka (; plural ''haka'', in both Māori and English) are a variety of ceremonial performance art in Māori culture. It is often performed by a group, with vigorous movements and stamping of the feet with rhythmically shouted or chanted accompani ...

, kapa haka

Kapa haka is the term for Māori action songs and the groups who perform them. It literally means 'group' () and 'dance' (). Kapa haka is an important avenue for Māori people to express and showcase their heritage and cultural Polynesian identi ...

, poi, Fa'ataupati

The Fa'ataupati is a dance indigenous to the Samoans. In English it is simply the "Samoan Slap Dance". It was developed in Samoa in the 19th century and is only performed by males.

History

The word ''pati'' in Fa'ataupati means "to clap", Fa'a ...

, Tau'olunga, and Lakalaka

The lakalaka (walking briskly) is a Tongan group dance where the performers are largely standing still and make gestures with their arms only. It is considered as the national dance of Tonga and part of the intangible human heritage. It is the ide ...

) that come from other Polynesian islands such as Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

, The Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

, Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

; however, the hula is unique to the Hawaiian Islands.

All five hula genres can be placed at certain points on a spectrum that features “the most ancient” on the left and “the most modern” on the other side. Hula pahu and hula ‘āla‘apapa are two subcategories that are always considered to be ancient, with origins dating before the introduction of Christianity. Thanks to the well-preserved documentation that still exists today, the important guidelines that performers should follow for bringing the poetic text back on stage remain clear in manuscript sources. On the other side of the continuum, hapa haole songs are relatively modern and those songs were also disseminated as notated sheet music, which were the joint effort devoted by contemporary ethnomusicologists and songwriters. The rest of the two hula types, hula ku’i and hula ‘ōlapa leave a massive challenge to editors in terms of entextualizing and representing these two genres generally within a critical edition. These two genres show a reflection of the social transformation and westernization happened within the region when the American economic and politics influence immerse more within. More importantly, the same strophic text format is applied in both genres, being constructed with two of four lines of text, with each of them is commonly set to a uniform number of beats. During performance, it is a usual practice that the songs are separated into stanzas which are normally repeated by a brief rhythmic interlude. Among all five genres of hula, the corresponding melodic structure and the strophic musical structure are elements that make modern hula ku’i and hula ‘ōlapa distinguishable when compared to others.

Hula kahiko

Hula kahiko, often defined as those hula composed prior to 1894 which do not include modern instrumentation (such as guitar, ʻukulele, etc.), encompasses an enormous variety of styles and moods, from the solemn and sacred to the frivolous. Many hula were created to praise the chiefs and performed in their honor, or for their entertainment. Types of hula kahiko include ālaapapa, haa, ōlapa, and many others. Today hula kahiko is simply stated as "Traditional" Hula.

Many hula dances are considered to be a religious performance, as they are dedicated to, or honoring, a Hawaiian goddess or god. As was true of ceremonies at the

Hula kahiko, often defined as those hula composed prior to 1894 which do not include modern instrumentation (such as guitar, ʻukulele, etc.), encompasses an enormous variety of styles and moods, from the solemn and sacred to the frivolous. Many hula were created to praise the chiefs and performed in their honor, or for their entertainment. Types of hula kahiko include ālaapapa, haa, ōlapa, and many others. Today hula kahiko is simply stated as "Traditional" Hula.

Many hula dances are considered to be a religious performance, as they are dedicated to, or honoring, a Hawaiian goddess or god. As was true of ceremonies at the heiau

A ''heiau'' () is a Hawaiian temple. Made in different architectural styles depending upon their purpose and location, they range from simple earth terraces, to elaborately constructed stone platforms. There are heiau to treat the sick (''heia ...

, the platform temple, even a minor error was considered to invalidate the performance. It might even be a presage of bad luck or have dire consequences. Dancers who were learning to do such hula necessarily made many mistakes. Hence they were ritually secluded and put under the protection of the goddess Laka during the learning period. Ceremonies marked the successful learning of the hula and the emergence from seclusion.

Hula kahiko is performed today by dancing to the historical chants. Many hula kahiko are characterized by traditional costuming, by an austere look, and a reverence for their spiritual root.

Chant (Oli)

Hawaiian history

The history of Hawaii describes the era of human settlements in the Hawaiian Islands. The islands were first settled by Polynesians sometime between 124 and 1120 AD. Hawaiian civilization was isolated from the rest of the world for at least 50 ...

was oral history. It was codified in genealogies and chants, which were memorized and passed down. In the absence of a written language, this was the only available method of ensuring accuracy. Chants told the stories of creation, mythology, royalty, and other significant events and people.

The ''ʻŌlelo Noʻeau'' (Hawaiian saying or proverb), “''‘O ‘oe ka luaʻahi o kāu mele'',” translates loosely as “You bear both the good and the bad consequences of the poetry you compose” The idea behind this saying originates from the ancient Hawaiian belief that language possessed mana, or “power derived from a spiritual source” particularly when delivered through ''oli'' (chant). Therefore, skillful manipulation of language by ''haku mele'' (composers) and chanters was of utmost reverence and importance. Oli was an integral component of ancient Hawaiian society, and arose in nearly every social, political and economic aspect of life.

Traditional chant types are extremely varied in context and technical components, and cover a broad range of specific functions. Among them (in vague descending order of sacredness) exist ''mele pule'' (prayer), ''hula kuahu'' (ritual dance), ''kūʻauhau'' (cosmogeny), ''koʻihonua'' (genealogy), ''hānau'' (birth), ''inoa'' (name), ''maʻi'' (procreation/genital), ''kanikau'' (lamentation), ''hei'' (game), ''hoʻoipoipo'' (love), and ''kāhea'' (expression/call out).

An important distinction between ''oli'', ''hula'', and ''mele'' is as follows: ''mele'' can hold many different meanings, and is often translated to mean simply, song. However, in a more broad sense, ''mele'' can be taken to mean poetry or linguistic composition. Hula (chant with dance) and oli (chant without dance) are two general styles in which mele can be used/performed. Generally, “all mele may be performed as oli (chant without dance), but only certain types such as name chants, sex chants, love chants, and chants dedicated to the [''‘aumakua''] gods of hula (ritual dance), may be performed as hula (chant with dance).”

Hawaiian language contains 43 different words to describe voice quality; the technique and particularity of chanting styles is crucial to understanding their function. The combination of general style (with or without dance) and the context of the performance determines what vocal style a chant will use. ''Kepakepa, kāwele, olioli, ho‘āeae, ho‘ouēuē'', and ''‘aiha‘a'' are examples of styles differentiated by vocal technique. ''Kepakepa'' sounds like rapid speech and is often spoken in long phrases. ''Olioli'' is a style many would liken to song, as it is melodic in nature and includes sustained pitches, often with ''‘i‘i'', or vibrato of the voice thats hold vowel tones at the ends of lines.

A law passed in Hawai‘i in 1896 (shortly after American overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom) banned the use of ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i in schools. This, in combination with a general usurpation of Hawaiian social, political, and linguistic autonomy resulted in a mass decline of the Hawaiian language, to the near brink of extinction. As a result of Americanization, including the spread of Christianity, many traditional chants became viewed as pagan and were ultimately forgotten. But a cultural resurgence beginning in the late 1960s, and carrying through to today has revitalized many Hawaiian practices, including spoken language and chant, and has been furthered by increasing support from various institutions, including Pūnana Leo Hawaiian language immersion schools, funded by the Hawai‘i State Department of Education as well as major hula competitions such as the Merrie Monarch Festival, which officially began in 1971.

In ''hālau hula'' (hula schools) asking permission to enter the space in order to partake in the knowledge of the ''kumu'' (teacher) is a key component to being a student. Many hālau use a variation of “Kūnihi,” an ''oli kāhea'', most typically done in an ''olioli'' style. Students often stand outside the entrance and chant repeatedly until the kumu decides to grant them permission to enter, and uses a different chant in response. This is an example of how oli is integrated into modern day cultural practices, within the context of hula training.

Oli is universally considered as the most typical type of indigenous music that is not constructed onto meters. In fact, the artistic expression of oli varies according to the circumstances where the performance is conducted, which is also the reason why there are five different articulatory vocal techniques were developed in oli repertoire. These five styles are:

* ''kepakepa'': A conversational patter that is expected to be performed swiftly, where the syllables are usually too short to allow pitches to be identified.

* ''kawele'': Comparing with the kepakepa, syllables are sustained a bit longer in kawele, but yet to be easily identified in pitches. It tends to be a more suitable form for recitation and declamation among Olis.

* ''olioli'': It is regarded as the most commonly used kind of oli, which the sustained pitch monotone carries the poetic form in a more vocally-embellished way.

* ''ho‘āeae'': It uses sustained pitches more often and there can be multiple pitches following fundamental configuration throughout the musical context.

* ''ho‘ouweuwe'': it is exclusively applied as the laments in funeral.

Oli performer does not purposely learn repertoire with the aim of merely learning the melodies, but the performative techniques. The most important thing for performer to master is decide which style the poetic text can be perfectly fitted into and figure out the way that can flawlessly combine both the text and the oli style according to the given context, such time limits and the particular situation where the oli is delivered.

Instruments and implements

* Ipu—single gourd drum

* Ipu heke—double gourd drum

* Pahu—sharkskin covered drum; considered sacred

* Puniu—small knee drum made of a coconut shell with fish skin (kala) cover

* Iliili—water-worn lava stone used as castanets

* Ulīulī—feathered gourd rattles (also ulili)

* Pūili—split bamboo sticks

* Kālaau—rhythm sticks

The dog's-tooth anklets sometimes worn by male dancers could also be considered instruments, as they underlined the sounds of stamping feet.

* Ipu—single gourd drum

* Ipu heke—double gourd drum

* Pahu—sharkskin covered drum; considered sacred

* Puniu—small knee drum made of a coconut shell with fish skin (kala) cover

* Iliili—water-worn lava stone used as castanets

* Ulīulī—feathered gourd rattles (also ulili)

* Pūili—split bamboo sticks

* Kālaau—rhythm sticks

The dog's-tooth anklets sometimes worn by male dancers could also be considered instruments, as they underlined the sounds of stamping feet.

Dress/Outfits

Traditional female dancers wore the everyday ''pāū'', or wrapped skirt, but were topless. Today this form of dress has been altered. As a sign of lavish display, the pāū might be much longer than the usual length of Tapa cloth, tapa, or barkcloth, which was just long enough to go around the waist. Visitors report seeing dancers swathed in many yards of tapa, enough to increase their circumference substantially. Dancers might also wear decorations such as necklaces, bracelets, and anklets, as well as many Lei (Hawaii), lei (in the form of headpieces (lei poʻo), necklaces, bracelets, and anklets (kupeʻe)), and other accessories.

Traditional female dancers wore the everyday ''pāū'', or wrapped skirt, but were topless. Today this form of dress has been altered. As a sign of lavish display, the pāū might be much longer than the usual length of Tapa cloth, tapa, or barkcloth, which was just long enough to go around the waist. Visitors report seeing dancers swathed in many yards of tapa, enough to increase their circumference substantially. Dancers might also wear decorations such as necklaces, bracelets, and anklets, as well as many Lei (Hawaii), lei (in the form of headpieces (lei poʻo), necklaces, bracelets, and anklets (kupeʻe)), and other accessories.

A skirt of green Cordyline fruticosa, kī (''Cordyline fruticosa'') leaves may also be worn over the ''pāū''. They are arranged in a dense layer of around fifty leaves. Kī were sacred to the goddess of the forest and the hula dance Laka, and as such, only ''kahuna'' and ''aliʻi'' were allowed to wear kī leaf leis (''lei lāʻī'') during religious rituals. Similar ''C. fruticosa'' leaf skirts worn over ''tupenu'' are also used in religious dances in

A skirt of green Cordyline fruticosa, kī (''Cordyline fruticosa'') leaves may also be worn over the ''pāū''. They are arranged in a dense layer of around fifty leaves. Kī were sacred to the goddess of the forest and the hula dance Laka, and as such, only ''kahuna'' and ''aliʻi'' were allowed to wear kī leaf leis (''lei lāʻī'') during religious rituals. Similar ''C. fruticosa'' leaf skirts worn over ''tupenu'' are also used in religious dances in Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

, where it is known as ''sisi''. However, Tongan leaf skirts generally use red and yellow leaves.

Traditional male dancers wore the everyday malo, or loincloth. Again, they might wear bulky malo made of many yards of tapa. They also wore necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and lei.

The materials for the lei worn in performance were gathered in the forest, after prayers to Laka and the forest gods had been chanted.

The lei and tapa worn for sacred hula were considered imbued with the sacredness of the dance, and were not to be worn after the performance. Lei were typically left on the small altar to Laka found in every hālau, as offerings.

Performances

Hula performed for spontaneous daily amusement or family feasts were attended with no particular ceremony. However, hula performed as entertainment for chiefs were anxious affairs. High chiefs typically traveled from one place to another within their domains. Each locality had to house, feed, and amuse the chief and his or her entourage. Hula performances were a form of fealty, and often of flattery to the chief. During the performances the males would start off and the females would come later to close the show off. Most kahiko performances would begin with an opening dance, kai, and end with a closing dance, hoi, to state the presence of the hula. There were hula celebrating his lineage, his name, and even his genitals (hula mai). Sacred hula, celebrating Hawaiian gods, were also danced. All these performances must be completed without error (which would be both unlucky and disrespectful). Visiting chiefs from other domains would also be honored with hula performances. This courtesy was often extended to important Western visitors.Hula auana

Modern hula arose from adaptation of traditional hula ideas (dance and mele) to Western influences. The primary influences were Christian morality and melodic harmony. Hula auana still tells or comments on a story, but the stories may include events since the 1800s. The costumes of the women dancers are less revealing and the music is heavily Western-influenced.

Modern hula arose from adaptation of traditional hula ideas (dance and mele) to Western influences. The primary influences were Christian morality and melodic harmony. Hula auana still tells or comments on a story, but the stories may include events since the 1800s. The costumes of the women dancers are less revealing and the music is heavily Western-influenced.

Songs

The mele of hula auana are generally sung as if they were popular music. A lead voice sings in a major scale, with occasional harmony parts. The subject of the songs is as broad as the range of human experience. People write mele hula auana to comment on significant people, places or events or simply to express an emotion or idea. While the whole Hawaiian repertoire can be mainly categorised into two sides, hua kahiko and hula 'auana, the sound accompaniments have been regarded as one of the symbolic signs to distinguish them. In indigenous Hawaiian music, poetic text has always been an essential artistic element. It was documented that early Hawaiian musicians did not really focus on elaborating pure instrumental music but simply used the nose-blown flute that can only produce no more than four notes. However, after the Hawaiian culture met with Western music, some Hawaiian musicians developed several instrument-playing techniques in which the traditional Hawaiian repertoire was embedded. For example, the appearance of a Hawaiian guitar-playing method, named "steel guitar", was attributed to the perfect combination happened when guitarist is muting the strings with a steel bar; another guitar-playing approach, "slack key guitar", requires musician to tune the guitar by slackening the strings and pluck out main melody with the high-pitched strings when the lower-pitched strings are also worked on for the production of constant bass pattern.Instruments

The musicians performing hula auana will typically use portable acoustic String instrument, stringed instruments. ; used as part of the rhythm section, or as a lead instrument * Steel guitar—accents the vocalist * Bass—maintains the rhythm Occasional hula auana call for the dancers to use implements, in which case they will use the same instruments as for hula kahiko. Often dancers use the Ulīulī (feathered gourd rattle).Regalia

The traditional Hawaiian hula costume includes kapa cloth skirts and men in just the malo (loincloth) however, during 1880s hula ‘auana was developed from western influences. It is during this period that the grass skirt began to be seen everywhere although, Hula ‘auana costumes are usually more western-looking, with dresses for women and pants for men.

Regalia plays a role in illustrating the hula instructor's interpretation of the mele. From the color of their attire to the type of adornment worn, each piece of an auana costume symbolizes a piece of the mele auana, such as the color of a significant place or flower. While there is some freedom of choice, most hālau follow the accepted costuming traditions. Women generally wear skirts or dresses of some sort. Men may wear long or short pants, skirts, or a malo (a cloth wrapped under and around the groin). For slow, graceful dances, the dancers will wear Formal wear, formal clothing such as a muumuu for women and a sash for men. A fast, lively, "rascal" song will be performed by dancers in more revealing or festive attire. The hula kahiko is always performed with Barefoot, bare feet, but the hula auana can be performed with bare feet or shoes. In the old times, they had their leis and other jewelry but their clothing was much different. Females wore a wrap called a "paʻu" made of tapa cloth and men wore loincloths, which are called "malo." Both sexes are said to have gone without a shirt. Their ankle and wrist bracelets, called "kupeʻe", were made of whalebone and dogteeth as well as other items made from nature. Some of these make music-shells and bones will rattle against each other while the dancers dance.

Women perform most Hawaiian hula dances. Female hula dancers usually wear colorful tops and skirts with lei. However, traditionally, men were just as likely to perform the hula.

A grass skirt is a skirt that hangs from the waist and covers all or part of the legs. Grass skirts were made of many different natural fibers, such as hibiscus or palm.

The traditional Hawaiian hula costume includes kapa cloth skirts and men in just the malo (loincloth) however, during 1880s hula ‘auana was developed from western influences. It is during this period that the grass skirt began to be seen everywhere although, Hula ‘auana costumes are usually more western-looking, with dresses for women and pants for men.

Regalia plays a role in illustrating the hula instructor's interpretation of the mele. From the color of their attire to the type of adornment worn, each piece of an auana costume symbolizes a piece of the mele auana, such as the color of a significant place or flower. While there is some freedom of choice, most hālau follow the accepted costuming traditions. Women generally wear skirts or dresses of some sort. Men may wear long or short pants, skirts, or a malo (a cloth wrapped under and around the groin). For slow, graceful dances, the dancers will wear Formal wear, formal clothing such as a muumuu for women and a sash for men. A fast, lively, "rascal" song will be performed by dancers in more revealing or festive attire. The hula kahiko is always performed with Barefoot, bare feet, but the hula auana can be performed with bare feet or shoes. In the old times, they had their leis and other jewelry but their clothing was much different. Females wore a wrap called a "paʻu" made of tapa cloth and men wore loincloths, which are called "malo." Both sexes are said to have gone without a shirt. Their ankle and wrist bracelets, called "kupeʻe", were made of whalebone and dogteeth as well as other items made from nature. Some of these make music-shells and bones will rattle against each other while the dancers dance.

Women perform most Hawaiian hula dances. Female hula dancers usually wear colorful tops and skirts with lei. However, traditionally, men were just as likely to perform the hula.

A grass skirt is a skirt that hangs from the waist and covers all or part of the legs. Grass skirts were made of many different natural fibers, such as hibiscus or palm.

Training

Hula is taught in schools or groups called ''halau, hālau''. The teacher of hula is the ''kumu hula''. ''Kumu'' means "source of knowledge", or literally "teacher".

Often there is a hierarchy in hula schools - starting with the (teacher), (leader), (helpers), and then the (dancers) or (students). This is not true for every halau, hālau, but it does occur often. Most, if not all, hula hālau have a permission chant in order to enter wherever they may practice. They will collectively chant their entrance chant, then wait for the kumu to respond with the entrance chant, once he or she is finished, the students may enter. One well known and often used entrance or permission chant is Kūnihi Ka Mauna/Tūnihi Ta Mauna.

Hula is taught in schools or groups called ''halau, hālau''. The teacher of hula is the ''kumu hula''. ''Kumu'' means "source of knowledge", or literally "teacher".

Often there is a hierarchy in hula schools - starting with the (teacher), (leader), (helpers), and then the (dancers) or (students). This is not true for every halau, hālau, but it does occur often. Most, if not all, hula hālau have a permission chant in order to enter wherever they may practice. They will collectively chant their entrance chant, then wait for the kumu to respond with the entrance chant, once he or she is finished, the students may enter. One well known and often used entrance or permission chant is Kūnihi Ka Mauna/Tūnihi Ta Mauna.

History

Legendary origins

There are various legends surrounding the origins of hula.

According to one Hawaiian legend, Laka, goddess of the hula, gave birth to the dance on the island of Molokai, Molokai, at a sacred place in Kaana. After Laka died, her remains were hidden beneath the hill ''Puu Nana''.

Another story tells of ''Hiiaka'', who danced to appease her fiery sister, the volcano goddess Pele (deity), Pele. This story locates the source of the hula on Hawaii, in the Puna district at the Hāena shoreline. The ancient hula ''Ke Haa Ala Puna'' describes this event.

Another story is when Pele, the goddess of fire was trying to find a home for herself running away from her sister Namakaokahai, Namakaokahaʻi (the goddess of the oceans) when she finally found an island where she couldn't be touched by the waves. There at chain of craters on the island of Hawai'i she danced the first dance of hula signifying that she finally won.

Kumu Hula (or "hula master") Leato S. Savini of the Hawaiian cultural academy Hālau Nā Mamo O Tulipa, located in Waianae, Japan, and Virginia, believes that hula goes as far back as what the Hawaiians call the ''Kumulipo'', or account of how the world was made first and foremost through the god of life and water, Kane. Kumu Leato is cited as saying, "When Kane and the other gods of our creation, Lono, Kū, and Kanaloa created the earth, the man, and the woman, they recited incantations which we call Oli or Chants and they used their hands and moved their legs when reciting these oli. Therefore this is the origin of hula."

There are various legends surrounding the origins of hula.

According to one Hawaiian legend, Laka, goddess of the hula, gave birth to the dance on the island of Molokai, Molokai, at a sacred place in Kaana. After Laka died, her remains were hidden beneath the hill ''Puu Nana''.

Another story tells of ''Hiiaka'', who danced to appease her fiery sister, the volcano goddess Pele (deity), Pele. This story locates the source of the hula on Hawaii, in the Puna district at the Hāena shoreline. The ancient hula ''Ke Haa Ala Puna'' describes this event.

Another story is when Pele, the goddess of fire was trying to find a home for herself running away from her sister Namakaokahai, Namakaokahaʻi (the goddess of the oceans) when she finally found an island where she couldn't be touched by the waves. There at chain of craters on the island of Hawai'i she danced the first dance of hula signifying that she finally won.

Kumu Hula (or "hula master") Leato S. Savini of the Hawaiian cultural academy Hālau Nā Mamo O Tulipa, located in Waianae, Japan, and Virginia, believes that hula goes as far back as what the Hawaiians call the ''Kumulipo'', or account of how the world was made first and foremost through the god of life and water, Kane. Kumu Leato is cited as saying, "When Kane and the other gods of our creation, Lono, Kū, and Kanaloa created the earth, the man, and the woman, they recited incantations which we call Oli or Chants and they used their hands and moved their legs when reciting these oli. Therefore this is the origin of hula."

19th century

American Protestantism, Protestant missionaries, who arrived in 1820, often denounced the hula as a heathen dance holding vestiges of paganism. The newly Christianized alii (royalty and nobility) were urged to ban the hula. In 1830 Queen Ka'ahumanu, Queen Kaʻahumanu forbade public performances. However, many of them continued to privately patronize the hula. By the 1850s, public hula was regulated by a system of licensing.

The Hawaiian performing arts had a resurgence during the reign of King Kalākaua, David Kalākaua (1874–1891), who encouraged the traditional arts. With the Princess Lili'uokalani who devoted herself to the old ways, as the patron of the ancients chants (mele, hula), she stressed the importance to revive the diminishing culture of their ancestors within the damaging influence of foreigners and modernism that was forever changing Hawaii.

Practitioners merged Hawaiian poetry, chanted Singing, vocal performance, Dance, dance movements and costumes to create the new form, the ''hula kui'' (kui means "to combine old and new"). The appears not to have been used in hula kui, evidently because its sacredness was respected by practitioners; the gourd (Lagenaria sicenaria) was the indigenous instrument most closely associated with hula kui.

Ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice, even as late as the early 20th century. Teachers and students were dedicated to the goddess of the hula, Laka.

American Protestantism, Protestant missionaries, who arrived in 1820, often denounced the hula as a heathen dance holding vestiges of paganism. The newly Christianized alii (royalty and nobility) were urged to ban the hula. In 1830 Queen Ka'ahumanu, Queen Kaʻahumanu forbade public performances. However, many of them continued to privately patronize the hula. By the 1850s, public hula was regulated by a system of licensing.

The Hawaiian performing arts had a resurgence during the reign of King Kalākaua, David Kalākaua (1874–1891), who encouraged the traditional arts. With the Princess Lili'uokalani who devoted herself to the old ways, as the patron of the ancients chants (mele, hula), she stressed the importance to revive the diminishing culture of their ancestors within the damaging influence of foreigners and modernism that was forever changing Hawaii.

Practitioners merged Hawaiian poetry, chanted Singing, vocal performance, Dance, dance movements and costumes to create the new form, the ''hula kui'' (kui means "to combine old and new"). The appears not to have been used in hula kui, evidently because its sacredness was respected by practitioners; the gourd (Lagenaria sicenaria) was the indigenous instrument most closely associated with hula kui.

Ritual and prayer surrounded all aspects of hula training and practice, even as late as the early 20th century. Teachers and students were dedicated to the goddess of the hula, Laka.

20th century hula dancing

Hula changed drastically in the early 20th century as it was featured in Tourism, tourist spectacles, such as the Kodak Hula Show, and in Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood films. Vaudeville star Signe Paterson was instrumental in raising its profile and popularity on the American stage, performing the hula in New York and Boston, teaching society figures the dance, and touring the country with the Royal Hawaiian Orchestra. However, a more traditional hula was maintained in small circles by older practitioners. There has been a renewed interest in hula, both traditional and modern, since the 1970s and the Hawaiian Renaissance.

In response to several Pacific island sports teams using their respective native war chants and dances as pre-game ritual challenges, the University of Hawaii football team started doing a war chant and dance using the native Hawaiian language that was called the ha'a before games in 2007.

Since 1964, the Merrie Monarch Festival has become an annual one week long hula competition held in the spring that attracts visitors from all over the world. It is to honor King David Kalākaua who was known as the Merrie Monarch as he revived the art of hula. Although Merrie Monarch was seen as a competition among hula hālaus, it later became known as a tourist event because of the many people it attracted.Heather Diamond, ''American Aloha: Cultural Tourism and the Negotiation of Tradition'' (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007), 49.

Hula changed drastically in the early 20th century as it was featured in Tourism, tourist spectacles, such as the Kodak Hula Show, and in Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood films. Vaudeville star Signe Paterson was instrumental in raising its profile and popularity on the American stage, performing the hula in New York and Boston, teaching society figures the dance, and touring the country with the Royal Hawaiian Orchestra. However, a more traditional hula was maintained in small circles by older practitioners. There has been a renewed interest in hula, both traditional and modern, since the 1970s and the Hawaiian Renaissance.

In response to several Pacific island sports teams using their respective native war chants and dances as pre-game ritual challenges, the University of Hawaii football team started doing a war chant and dance using the native Hawaiian language that was called the ha'a before games in 2007.

Since 1964, the Merrie Monarch Festival has become an annual one week long hula competition held in the spring that attracts visitors from all over the world. It is to honor King David Kalākaua who was known as the Merrie Monarch as he revived the art of hula. Although Merrie Monarch was seen as a competition among hula hālaus, it later became known as a tourist event because of the many people it attracted.Heather Diamond, ''American Aloha: Cultural Tourism and the Negotiation of Tradition'' (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007), 49.

Films

* ''Kumu Hula: Keepers of a Culture'' (1989) Directed by Robert Mugge. * ''Holo Mai Pele - Hālau ō Kekuhi '' (2000) Directed by Catherine Tatge * ''American Aloha : Hula Beyond Hawaii '' (2003) By Lisette Marie Flannery & Evann Siebens * ''Hula Girls'' (2006) * ''The Haumana'' (2013) * ''Kumu Hina'' (2014)Books

* Nathaniel Bright Emerson, Nathaniel Emerson, ''The Myth of Pele and Hi'iaka''. This book includes the original Hawaiian of the Pele and Hi'iaka myth and as such provides an invaluable resource for language students and others. * Nathaniel Bright Emerson, Nathaniel Emerson, ''The Unwritten Literature of Hawaii''. Many of the original Hawaiian hula chants, together with Emerson's descriptions of how they were danced in the nineteenth century. * Amy Stillman, ''Hula `Ala`apapa''. An analysis of the `Ala`apapa style of sacred hula. * Ishmael W. Stagner: ''Kumu hula : roots and branches''. Honolulu : Island Heritage Pub., 2011. * Jerry Hopkins, ''The Hula; A Revised Edition: ''Bess Press Inc., 2011. * Nanette Kilohana Kaihawanawana Orman, ʻʻHula Sister: A Guide to the Native Dance of Hawaiiʻʻ. Honolulu: Island Heritage Pub., 2015. .See also

* ''Cordyline fruticosa'', the kī, a sacred plant whose leaves are traditionally used for hula skirtsReferences

External links

Hula Teacher On What's My Line 8/26/62

Everything Related To Hula Dancing, Hula History & Hula Theory

Hawaiian Music and Hula Archives

Hula Preservation Society

Merrie Mondarch Festival

European Hula Festival

Hula Dance fine art photography

"Where Tradition Holds Sway"

Article about "Ka Hula Piko" on Molokai, by Jill Engledow. ''Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine'' Vol. 11 No.2 (March 2007). *

American Aloha : Hula Beyond Hawaii

' (2003) - PBS film

Hula Dance Class Salt Lake County UT

{{Authority control Hula, Hawaiian music Dances of Polynesia Tiki culture Articles containing video clips Dance in Hawaii Group dances Austronesian spirituality