Hovercraft feuerwehr steinberg 09012009.JPG on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A hovercraft, also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious

A hovercraft, also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious

In 1931, Finnish aero engineer Toivo J. Kaario began designing a developed version of a vessel using an air cushion and built a prototype ('Surface Glider'), in 1937. His design included the modern features of a lift engine blowing air into a flexible envelope for lift. However, he never received funding to build his design. Kaario's efforts were followed closely in the Soviet Union by Vladimir Levkov, who returned to the solid-sided design of the . Levkov designed and built a number of similar craft during the 1930s, and his L-5 fast-attack boat reached in testing. However, the start of

In 1931, Finnish aero engineer Toivo J. Kaario began designing a developed version of a vessel using an air cushion and built a prototype ('Surface Glider'), in 1937. His design included the modern features of a lift engine blowing air into a flexible envelope for lift. However, he never received funding to build his design. Kaario's efforts were followed closely in the Soviet Union by Vladimir Levkov, who returned to the solid-sided design of the . Levkov designed and built a number of similar craft during the 1930s, and his L-5 fast-attack boat reached in testing. However, the start of

Another discovery was that the total amount of air needed to lift the craft was a function of the roughness of the surface over which it travelled. On flat surfaces, like pavement, the required air pressure was so low that hovercraft were able to compete in energy terms with conventional systems like steel wheels. However, the hovercraft lift system acted as both a lift and a very effective suspension, and thus it naturally lent itself to high-speed use where conventional suspension systems were considered too complex. This led to a variety of "

Another discovery was that the total amount of air needed to lift the craft was a function of the roughness of the surface over which it travelled. On flat surfaces, like pavement, the required air pressure was so low that hovercraft were able to compete in energy terms with conventional systems like steel wheels. However, the hovercraft lift system acted as both a lift and a very effective suspension, and thus it naturally lent itself to high-speed use where conventional suspension systems were considered too complex. This led to a variety of " By the early 1970s, the basic concept had been well developed, and the hovercraft had found a number of niche roles where its combination of features were advantageous. Today, they are found primarily in military use for amphibious operations, search-and-rescue vehicles in shallow water, and sporting vehicles.

By the early 1970s, the basic concept had been well developed, and the hovercraft had found a number of niche roles where its combination of features were advantageous. Today, they are found primarily in military use for amphibious operations, search-and-rescue vehicles in shallow water, and sporting vehicles.

During the 1960s, Saunders-Roe developed several larger designs that could carry passengers, including the SR.N2, which operated across the

During the 1960s, Saunders-Roe developed several larger designs that could carry passengers, including the SR.N2, which operated across the  The world's first car-carrying hovercraft was made in 1968, the BHC ''Mountbatten'' class (SR.N4) models, each powered by four Bristol Proteus

The world's first car-carrying hovercraft was made in 1968, the BHC ''Mountbatten'' class (SR.N4) models, each powered by four Bristol Proteus  Hovercraft used to ply between the Gateway of India in

Hovercraft used to ply between the Gateway of India in

In Finland, small hovercraft are widely used in maritime rescue and during the rasputitsa ("mud season") as

In Finland, small hovercraft are widely used in maritime rescue and during the rasputitsa ("mud season") as  In October 2008, The Red Cross commenced a flood-rescue service hovercraft based in Inverness, Scotland. Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service received two flood-rescue hovercraft donated by

In October 2008, The Red Cross commenced a flood-rescue service hovercraft based in Inverness, Scotland. Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service received two flood-rescue hovercraft donated by

Hovercraft are still manufactured in the UK, near to where they were first conceived and tested, on the Isle of Wight. They can also be chartered for a wide variety of uses including inspections of shallow bed offshore wind farms and VIP or passenger use. A typical vessel would be a Tiger IV or a Griffon. They are light, fast, road transportable and very adaptable with the unique feature of minimising damage to environments.

Hovercraft are still manufactured in the UK, near to where they were first conceived and tested, on the Isle of Wight. They can also be chartered for a wide variety of uses including inspections of shallow bed offshore wind farms and VIP or passenger use. A typical vessel would be a Tiger IV or a Griffon. They are light, fast, road transportable and very adaptable with the unique feature of minimising damage to environments.

The first application of the hovercraft for military use was by the British Armed Forces, using hovercraft built by Saunders-Roe. In 1961, the United Kingdom set up the Interservice Hovercraft Trials Unit (IHTU) based at

The first application of the hovercraft for military use was by the British Armed Forces, using hovercraft built by Saunders-Roe. In 1961, the United Kingdom set up the Interservice Hovercraft Trials Unit (IHTU) based at

In August 2010, the Hovercraft Club of Great Britain hosted the World Hovercraft Championships at Towcester Racecourse, followed by the 2016 World Hovercraft Championships at the West Midlands Water Ski Centre in Tamworth.

The World Hovercraft Championships are run under the auspices of the World Hovercraft Federation. So far the World Hovercraft Championships had been hosted by France: 1993 in Verneuil, 1997 in Lucon, 2006 at the Lac de Tolerme; Germany: 1987 in Bad Karlshafen, 2004 in Berlin, 2012 and 2018 in Saalburg; Portugal: 1995 in Peso de la Regua; Sweden: 2008 and 2022 at Flottbro Ski Center in Huddinge; UK 1991 and 2000 at Weston Parc; US: 1989 in Troy (Ohio), 2002 in Terre Haute. The 2020 World Hovercraft Championships had to be postponed to 2022 due to restriction caused by the Covid-19 outbreak.

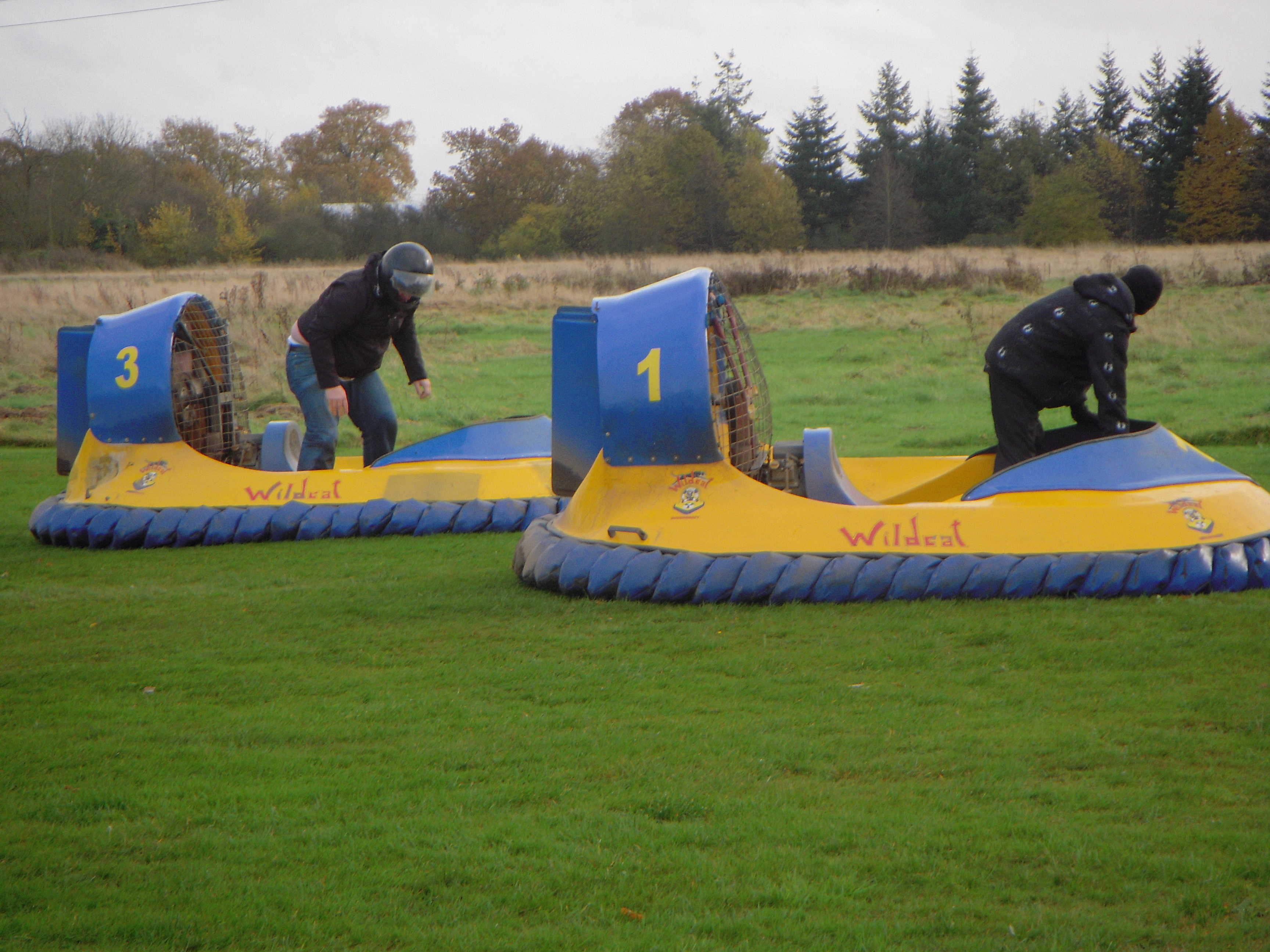

Apart from the craft designed as "racing hovercraft", which are often only suitable for racing, there is another form of small personal hovercraft for leisure use, often referred to as cruising hovercraft, capable of carrying up to four people. Just like their full size counterparts, the ability of these small personal hovercraft to safely cross all types of terrain, (e.g. water, sandbanks, swamps, ice, etc.) and reach places often inaccessible by any other type of craft, makes them suitable for a number of roles, such as survey work and patrol and rescue duties in addition to personal leisure use. Increasingly, these craft are being used as yacht tenders, enabling yacht owners and guests to travel from a waiting yacht to, for example, a secluded beach. In this role, small hovercraft can offer a more entertaining alternative to the usual small boat and can be a rival for the jet-ski. The excitement of a personal hovercraft can now be enjoyed at "experience days", which are popular with families, friends and those in business, who often see them as team building exercises. This level of interest has naturally led to a hovercraft rental sector and numerous manufacturers of small, ready built designs of personal hovercraft to serve the need.

In August 2010, the Hovercraft Club of Great Britain hosted the World Hovercraft Championships at Towcester Racecourse, followed by the 2016 World Hovercraft Championships at the West Midlands Water Ski Centre in Tamworth.

The World Hovercraft Championships are run under the auspices of the World Hovercraft Federation. So far the World Hovercraft Championships had been hosted by France: 1993 in Verneuil, 1997 in Lucon, 2006 at the Lac de Tolerme; Germany: 1987 in Bad Karlshafen, 2004 in Berlin, 2012 and 2018 in Saalburg; Portugal: 1995 in Peso de la Regua; Sweden: 2008 and 2022 at Flottbro Ski Center in Huddinge; UK 1991 and 2000 at Weston Parc; US: 1989 in Troy (Ohio), 2002 in Terre Haute. The 2020 World Hovercraft Championships had to be postponed to 2022 due to restriction caused by the Covid-19 outbreak.

Apart from the craft designed as "racing hovercraft", which are often only suitable for racing, there is another form of small personal hovercraft for leisure use, often referred to as cruising hovercraft, capable of carrying up to four people. Just like their full size counterparts, the ability of these small personal hovercraft to safely cross all types of terrain, (e.g. water, sandbanks, swamps, ice, etc.) and reach places often inaccessible by any other type of craft, makes them suitable for a number of roles, such as survey work and patrol and rescue duties in addition to personal leisure use. Increasingly, these craft are being used as yacht tenders, enabling yacht owners and guests to travel from a waiting yacht to, for example, a secluded beach. In this role, small hovercraft can offer a more entertaining alternative to the usual small boat and can be a rival for the jet-ski. The excitement of a personal hovercraft can now be enjoyed at "experience days", which are popular with families, friends and those in business, who often see them as team building exercises. This level of interest has naturally led to a hovercraft rental sector and numerous manufacturers of small, ready built designs of personal hovercraft to serve the need.

* World's Largest Civil Hovercraft – The BHC

* World's Largest Civil Hovercraft – The BHC

"The Future of Hovercraft"

Hovercraft Museum

at Lee-on-Solent, Gosport, UK

1965 film

of the Denny D2 hoverbus from the Scottish Screen Archive, National Library of Scotland

Royal Marines Super Hovercraft

Simple Potted History of the Hovercraft

Hovercraft Club of Great Britain

{{Authority control Articles containing video clips English inventions Amphibious vehicles Air-cushion vehicles

A hovercraft, also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious

A hovercraft, also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious craft

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale pro ...

capable of travelling over land, water, mud, ice, and other surfaces.

Hovercraft use blowers to produce a large volume of air below the hull, or air cushion, that is slightly above atmospheric pressure. The pressure difference between the higher pressure air below the hull and lower pressure ambient air above it produces lift, which causes the hull to float above the running surface. For stability reasons, the air is typically blown through slots or holes around the outside of a disk- or oval-shaped platform, giving most hovercraft a characteristic rounded-rectangle shape.

The first practical design for hovercraft was derived from a British invention in the 1950s. They are now used throughout the world as specialised transports in disaster relief, coastguard, military and survey applications, as well as for sport or passenger service. Very large versions have been used to transport hundreds of people and vehicles across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, whilst others have military applications used to transport tanks, soldiers and large equipment in hostile environments and terrain. Decline in public demand meant that , the only public hovercraft service in the world still in operation serves between the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

and Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre. Southsea is not a separate town as all of Portsea Island's s ...

in the UK.

Although now a generic term for the type of craft, the name ''Hovercraft'' itself was a trademark

A trademark (also written trade mark or trade-mark) is a type of intellectual property consisting of a recognizable sign, design, or expression that identifies products or services from a particular source and distinguishes them from othe ...

owned by Saunders-Roe

Saunders-Roe Limited, also known as Saro, was a British aero- and marine-engineering company based at Columbine Works, East Cowes, Isle of Wight.

History

The name was adopted in 1929 after Alliott Verdon Roe (see Avro) and John Lord took a c ...

(later British Hovercraft Corporation (BHC), then Westland Westland or Westlands may refer to:

Places

*Westlands, an affluent neighbourhood in the city of Nairobi, Kenya

* Westlands, Staffordshire, a suburban area and ward in Newcastle-under-Lyme

*Westland, a peninsula of the Shetland Mainland near Vaila ...

), hence other manufacturers' use of alternative names to describe the vehicles.

The standard plural of ''hovercraft'' is ''hovercraft'' (in the same manner that ''aircraft'' is both singular and plural).

History

Early efforts

There have been many attempts to understand the principles of high air pressure below hulls and wings. Hovercraft are unique in that they can lift themselves while still, differing from ground effect vehicles and hydrofoils that require forward motion to create lift. The first mention, in the historical record of the concepts behind surface-effect vehicles, to use the term ''hovering'' was by Swedish scientistEmanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had a ...

in 1716.

The shipbuilder John Isaac Thornycroft

Sir John Isaac Thornycroft (1 February 1843 – 28 June 1928) was an English shipbuilder, the founder of the Thornycroft shipbuilding company and member of the Thornycroft family.

Early life

He was born in 1843 to Mary Francis and Thomas ...

patented an early design for an air cushion ship / hovercraft in the 1870s, but suitable, powerful, engines were not available until the 20th century.

In 1915, the Austrian Dagobert Müller von Thomamühl

Dagobert Müller von Thomamühl (born 24 June 1880 in Trieste, died 10 January 1956 in Klagenfurt) was an Austrian naval officer and inventor.

Life

Dagobert Müller-Thomamühl attended from 1890 to 1895 the secondary school in Pula and from 189 ...

(1880–1956) built the world's first "air cushion" boat (). Shaped like a section of a large aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine. ...

(this creates a low-pressure area above the wing much like an aircraft), the craft was propelled by four aero engines driving two submerged marine propellers, with a fifth engine that blew air under the front of the craft to increase the air pressure under it. Only when in motion could the craft trap air under the front, increasing lift. The vessel also required a depth of water to operate and could not transition to land or other surfaces. Designed as a fast torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

, the had a top speed of over . It was thoroughly tested and even armed with torpedoes and machine guns for operation in the Adriatic. It never saw actual combat, however, and as the war progressed it was eventually scrapped due to a lack of interest and perceived need, and its engines returned to the air force.

The theoretical grounds for motion over an air layer were constructed by Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovskii

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (russian: Константи́н Эдуа́рдович Циолко́вский , , p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj , a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; – 19 September 1935) ...

in 1926 and 1927."

In 1929, Andrew Kucher of Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

began experimenting with the ''Levapad'' concept, metal disks with pressurized air blown through a hole in the center. Levapads do not offer stability on their own. Several must be used together to support a load above them. Lacking a skirt, the pads had to remain very close to the running surface. He initially imagined these being used in place of caster

A caster (or castor) is an undriven wheel that is designed to be attached to the bottom of a larger object (the "vehicle") to enable that object to be moved.

Casters are used in numerous applications, including shopping carts, office chairs, ...

s and wheels in factories and warehouses, where the concrete floors offered the smoothness required for operation. By the 1950s, Ford showed a number of toy models of cars using the system, but mainly proposed its use as a replacement for wheels on trains, with the Levapads running close to the surface of existing rails.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

put an end to his development work.

During World War II, an American engineer, Charles Fletcher, invented a walled air cushion vehicle, the ''Glidemobile''. Because the project was classified by the U.S. government, Fletcher could not file a patent.

In April 1958, Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

engineers demonstrated the Glide-air, a model of a wheel-less vehicle that speeds on a thin film of air only 76.2 μm ( of an inch) above its table top roadbed. An article in ''Modern Mechanix

''Mechanix Illustrated'' was an American printed magazine that was originally published by Fawcett Publications. Its title was founded in 1928 to compete against the older ''Popular Science'' and ''Popular Mechanics''. Billed as "The How-To-Do Ma ...

'' quoted Andrew A. Kucher, Ford's vice president in charge of Engineering and Research noting "We look upon Glide-air as a new form of high-speed land transportation, probably in the field of rail surface travel, for fast trips of distances of up to about ".

In 1959, Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

displayed a hovercraft concept car

A concept car (also known as a concept vehicle, show vehicle or prototype) is a car made to showcase new styling and/or new technology. They are often exhibited at motor shows to gauge customer reaction to new and radical designs which may or ...

, the Ford Levacar Mach I The Ford Mach I, also known as the Ford Levacar Mach I, is a concept car hovercraft developed by the Ford Motor Company in the 1950s. The Mach I was a single-seat automobile which rode on pressurized air, not wheels. Its name was inspired by the spe ...

.

In August 1961, '' Popular Science'' reported on the Aeromobile 35B, an air-cushion vehicle (ACV) that was invented by William Bertelsen and was envisioned to revolutionise the transportation system, with personal hovering self-driving car

A self-driving car, also known as an autonomous car, driver-less car, or robotic car (robo-car), is a car that is capable of traveling without human input.Xie, S.; Hu, J.; Bhowmick, P.; Ding, Z.; Arvin, F.,Distributed Motion Planning for S ...

s that could speed up to .

Christopher Cockerell

The idea of the modern hovercraft is most often associated withChristopher Cockerell

Sir Christopher Sydney Cockerell CBE RDI FRS (4 June 1910 – 1 June 1999) was an English engineer, best known as the inventor of the hovercraft.

Early life and education

Cockerell was born in Cambridge, where his father, Sir Sydney Cocke ...

, a British mechanical engineer. Cockerell's group was the first to develop the use of a ring of air for maintaining the cushion, the first to develop a successful skirt, and the first to demonstrate a practical vehicle in continued use. A memorial to Cockerell's first design stands in the village of Somerleyton

Somerleyton is a village and former civil parish in the north of the English county of Suffolk. It is north-west of Lowestoft and south-west of Great Yarmouth in the East Suffolk district. The village is closely associated with Somerleyto ...

.

Cockerell came across the key concept in his design when studying the ring of airflow when high-pressure air was blown into the annular area between two concentric tin cans (one coffee and the other from cat food) and a hairdryer. This produced a ring of airflow, as expected, but he noticed an unexpected benefit as well; the sheet of fast-moving air presented a sort of physical barrier to the air on either side of it. This effect, which he called the "momentum curtain", could be used to trap high-pressure air in the area inside the curtain, producing a high-pressure plenum that earlier examples had to build up with considerably more airflow. In theory, only a small amount of active airflow would be needed to create lift and much less than a design that relied only on the momentum of the air to provide lift, like a helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

. In terms of power, a hovercraft would only need between one quarter to one half of the power required by a helicopter.

Cockerell built and tested several models of his hovercraft design in Somerleyton, Suffolk, during the early 1950s. The design featured an engine mounted to blow from the front of the craft into a space below it, combining both lift and propulsion. He demonstrated the model flying over many Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

carpets in front of various government experts and ministers, and the design was subsequently put on the secret list. In spite of tireless efforts to arrange funding, no branch of the military was interested, as he later joked, "The Navy said it was a plane not a boat; the RAF said it was a boat not a plane; and the Army were 'plain not interested'."

Curtiss-Wright Model 2500 Air Car

SR.N1

This lack of military interest meant that there was no reason to keep the concept secret, and it was declassified. Cockerell was finally able to convince theNational Research Development Corporation The National Research Development Corporation (NRDC) was a non-departmental government body established by the British Government to transfer technology from the public sector to the private sector.

History

The NRDC was established by Attlee's Lab ...

to fund development of a full-scale model. In 1958, the NRDC placed a contract with Saunders-Roe

Saunders-Roe Limited, also known as Saro, was a British aero- and marine-engineering company based at Columbine Works, East Cowes, Isle of Wight.

History

The name was adopted in 1929 after Alliott Verdon Roe (see Avro) and John Lord took a c ...

for the development of what would become the SR.N1, short for "Saunders-Roe, Nautical 1".

The SR.N1 was powered by a 450 hp Alvis Leonides

The Alvis Leonides was a British air-cooled nine-cylinder radial aero engine first developed by Alvis Car and Engineering Company in 1936.

Design and development

Development of the nine-cylinder engine was led by Capt. George Thomas Smith-Cla ...

engine powering a vertical fan in the middle of the craft. In addition to providing the lift air, a portion of the airflow was bled off into two channels on either side of the craft, which could be directed to provide thrust. In normal operation this extra airflow was directed rearward for forward thrust, and blew over two large vertical rudders that provided directional control. For low-speed maneuverability, the extra thrust could be directed fore or aft, differentially for rotation.

The SR.N1 made its first hover on 11 June 1959, and made its famed successful crossing of the English Channel on 25 July 1959. In December 1959, the Duke of Edinburgh visited Saunders-Roe at East Cowes

East Cowes is a town and civil parish in the north of the Isle of Wight, on the east bank of the River Medina, next to its west bank neighbour Cowes.

The two towns are connected by the Cowes Floating Bridge, a chain ferry operated by the Isle ...

and persuaded the chief test-pilot, Commander Peter Lamb, to allow him to take over the SR.N1's controls. He flew the SR.N1 so fast that he was asked to slow down a little. On examination of the craft afterwards, it was found that she had been dished in the bow due to excessive speed, damage that was never allowed to be repaired, and was from then on affectionately referred to as the 'Royal Dent'.

Skirts and other improvements

Testing quickly demonstrated that the idea of using a single engine to provide air for both the lift curtain and forward flight required too many trade-offs. A Blackburn Marboré turbojet for forward thrust and two large vertical rudders for directional control were added, producing the SR.N1 Mk II. A further upgrade with theArmstrong Siddeley Viper

The Armstrong Siddeley Viper is a British turbojet engine developed and produced by Armstrong Siddeley and then by its successor companies Bristol Siddeley and Rolls-Royce Limited. It entered service in 1953 and remained in use with the Roya ...

produced the Mk III. Further modifications, especially the addition of pointed nose and stern areas, produced the Mk IV.

Although the SR.N1 was successful as a testbed, the design hovered too close to the surface to be practical; at even small waves would hit the bow. The solution was offered by Cecil Latimer-Needham, following a suggestion made by his business partner Arthur Ord-Hume. In 1958, he suggested the use of two rings of rubber to produce a double-walled extension of the vents in the lower fuselage. When air was blown into the space between the sheets it exited the bottom of the skirt in the same way it formerly exited the bottom of the fuselage, re-creating the same momentum curtain, but this time at some distance from the bottom of the craft.

Latimer-Needham and Cockerell devised a high skirt design, which was fitted to the SR.N1 to produce the Mk V, displaying hugely improved performance, with the ability to climb over obstacles almost as high as the skirt. In October 1961, Latimer-Needham sold his skirt patents to Westland Westland or Westlands may refer to:

Places

*Westlands, an affluent neighbourhood in the city of Nairobi, Kenya

* Westlands, Staffordshire, a suburban area and ward in Newcastle-under-Lyme

*Westland, a peninsula of the Shetland Mainland near Vaila ...

, who had recently taken over Saunders Roe's interest in the hovercraft. Experiments with the skirt design demonstrated a problem; it was originally expected that pressure applied to the outside of the skirt would bend it inward, and the now-displaced airflow would cause it to pop back out. What actually happened is that the slight narrowing of the distance between the walls resulted in less airflow, which in turn led to more air loss under that section of the skirt. The fuselage above this area would drop due to the loss of lift at that point, and this led to further pressure on the skirt.

After considerable experimentation, Denys Bliss at Hovercraft Development Ltd. found the solution to this problem. Instead of using two separate rubber sheets to form the skirt, a single sheet of rubber was bent into a U shape to provide both sides, with slots cut into the bottom of the U forming the annular vent. When deforming pressure was applied to the outside of this design, air pressure in the rest of the skirt forced the inner wall to move in as well, keeping the channel open. Although there was some deformation of the curtain, the airflow within the skirt was maintained and the lift remained relatively steady. Over time, this design evolved into individual extensions over the bottom of the slots in the skirt, known as "fingers".

Commercialization

Through these improvements, the hovercraft became an effective transport system for high-speed service on water and land, leading to widespread developments for military vehicles, search and rescue, and commercial operations. By 1962, many UK aviation and shipbuilding firms were working on hovercraft designs, including Saunders Roe/Westland Westland or Westlands may refer to:

Places

*Westlands, an affluent neighbourhood in the city of Nairobi, Kenya

* Westlands, Staffordshire, a suburban area and ward in Newcastle-under-Lyme

*Westland, a peninsula of the Shetland Mainland near Vaila ...

, Vickers-Armstrong

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

, William Denny, Britten-Norman and Folland Folland is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Alison Folland (born 1978), American actress and filmmaker

* Gerald Folland (born 1947), American mathematician

* Henry Folland (1889–1954), British aviation engineer and aircraft de ...

. Small-scale ferry service started as early as 1962 with the launch of the Vickers-Armstrong VA-3. With the introduction of the 254 passenger and 30 car carrying SR.N4

The SR.N4 (Saunders-Roe Nautical 4) hovercraft (also known as the ''Mountbatten'' class hovercraft) was a combined passenger and vehicle-carrying class of hovercraft. The type has the distinction of being the largest civil hovercraft to have ...

cross-channel ferry by Hoverlloyd

Hoverlloyd operated a cross-Channel hovercraft service between Ramsgate, England and Calais, France.

Originally registered as ''Cross-Channel Hover Services Ltd'' in 1965, the company was renamed Hoverlloyd the following year. It was initially ...

and Seaspeed

Seaspeed was a British hovercraft operator which ran services in the Solent and English Channel between 1965 and 1981, when it merged with a rival to form Hoverspeed.

Seaspeed was a jointly owned subsidiary of railway companies British Rail ( ...

in 1968, hovercraft had developed into useful commercial craft.

Another major pioneering effort of the early hovercraft era was carried out by Jean Bertin

Jean Henri Bertin (5 September 1917 – 21 December 1975) was a French scientist, engineer and inventor. He was born in Druyes-les-Belles-Fontaines and died in Neuilly-sur-Seine. He is best known as the lead engineer for the French experime ...

's firm in France. Bertin was an advocate of the "multi-skirt" approach, which used a number of smaller cylindrical skirts instead of one large one in order to avoid the problems noted above. During the early 1960s he developed a series of prototype designs, which he called "terraplanes" if they were aimed for land use, and "naviplanes" for water. The best known of these designs was the N500 Naviplane

The N500 Naviplane was a French hovercraft built by SEDAM (''Société d'Etude et de Développement des Aéroglisseurs Marins'') in Pauillac, Gironde for the cross channel route. Intended to have a large passenger and crew capacity, it was for a ...

, built for Seaspeed by the ''Société d'Etude et de Développement des Aéroglisseurs Marins'' (SEDAM). The N500 could carry 400 passengers, 55 cars and five buses. It set a speed record between Boulogne and Dover of . It was rejected by its operators, who claimed that it was unreliable.

Another discovery was that the total amount of air needed to lift the craft was a function of the roughness of the surface over which it travelled. On flat surfaces, like pavement, the required air pressure was so low that hovercraft were able to compete in energy terms with conventional systems like steel wheels. However, the hovercraft lift system acted as both a lift and a very effective suspension, and thus it naturally lent itself to high-speed use where conventional suspension systems were considered too complex. This led to a variety of "

Another discovery was that the total amount of air needed to lift the craft was a function of the roughness of the surface over which it travelled. On flat surfaces, like pavement, the required air pressure was so low that hovercraft were able to compete in energy terms with conventional systems like steel wheels. However, the hovercraft lift system acted as both a lift and a very effective suspension, and thus it naturally lent itself to high-speed use where conventional suspension systems were considered too complex. This led to a variety of "hovertrain

A hovertrain is a type of high-speed train that replaces conventional steel wheels with hovercraft lift pads, and the conventional railway bed with a paved road-like surface, known as the ''track'' or ''guideway''. The concept aims to eliminat ...

" proposals during the 1960s, including England's Tracked Hovercraft

Tracked Hovercraft was an experimental high speed train developed in the United Kingdom during the 1960s. It combined two British inventions, the hovercraft and linear induction motor, in an effort to produce a train system that would provide ...

and France's ''Aérotrain

The Aérotrain was an experimental Tracked Air Cushion Vehicle

(TACV), or hovertrain, developed in France from 1965 to 1977 under the engineering leadership of Jean Bertin (1917–1975) – and intended to bring the French rail network to the c ...

''. In the U.S., Rohr Inc.

Rohr, Inc. is an aerospace manufacturing company based in Chula Vista, California, south of San Diego. It is a wholly owned unit of the Collins Aerospace division of Raytheon Technologies; it was founded in 1940 by Frederick H. Rohr as Rohr Air ...

and Garrett both took out licenses to develop local versions of the ''Aérotrain''. These designs competed with maglev

Maglev (derived from '' magnetic levitation''), is a system of train transportation that uses two sets of electromagnets: one set to repel and push the train up off the track, and another set to move the elevated train ahead, taking advantage ...

systems in the high-speed arena, where their primary advantage was the very "low tech" tracks they needed. On the downside, the air blowing dirt and trash out from under the trains presented a unique problem in stations, and interest in them waned in the 1970s.

Design

Hovercraft can be powered by one or more engines. Small craft, such as theSR.N6

The Saunders-Roe (later British Hovercraft Corporation) SR.N6 hovercraft (also known as the ''Winchester'' class) was essentially a larger version of the earlier SR.N5 series. It incorporated several features that resulted in the type becoming ...

, usually have one engine with the drive split through a gearbox. On vehicles with several engines, one usually drives the fan (or impeller

An impeller or impellor is a rotor used to increase the pressure and flow of a fluid. It is the opposite of a turbine, which extracts energy from, and reduces the pressure of, a flowing fluid.

In pumps

An impeller is a rotating componen ...

), which is responsible for lifting the vehicle by forcing high pressure air under the craft. The air inflates the "skirt" under the vehicle, causing it to rise above the surface. Additional engines provide thrust in order to propel the craft. Some hovercraft use ducting to allow one engine to perform both tasks by directing some of the air to the skirt, the rest of the air passing out of the back to push the craft forward.

Uses

Commercial

The British aircraft and marine engineering company Saunders-Roe built the first practical human-carrying hovercraft for theNational Research Development Corporation The National Research Development Corporation (NRDC) was a non-departmental government body established by the British Government to transfer technology from the public sector to the private sector.

History

The NRDC was established by Attlee's Lab ...

, the SR.N1, which carried out several test programmes in 1959 to 1961 (the first public demonstration was in 1959), including a cross-channel test run in July 1959, piloted by Peter "Sheepy" Lamb, an ex-naval test pilot and the chief test pilot at Saunders Roe. Christopher Cockerell was on board, and the flight took place on the 50th anniversary of Louis Blériot's first aerial crossing.

The SR.N1 was powered by a single piston engine, driven by expelled air. Demonstrated at the Farnborough Airshow

The Farnborough Airshow, officially the Farnborough International Airshow, is a trade exhibition for the aerospace and defence industries, where civilian and military aircraft are demonstrated to potential customers and investors. Since its fir ...

in 1960, it was shown that this simple craft can carry a load of up to 12 marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

with their equipment as well as the pilot and co-pilot with only a slight reduction in hover height proportional to the load carried. The SR.N1 did not have any skirt, using instead the peripheral air principle that Cockerell had patented. It was later found that the craft's hover height was improved by the addition of a skirt of flexible fabric or rubber around the hovering surface to contain the air. The skirt was an independent invention made by a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

officer, C.H. Latimer-Needham

Cecil Hugh (''Chookie'') Latimer-Needham (20 February 1900 – 5 May 1975) was a British aircraft designer, inventor and aviation author. He is best remembered for the series of aircraft he designed for the Luton Aircraft company and his inventio ...

, who sold his idea to Westland (by then the parent of Saunders-Roe's helicopter and hovercraft interests), and who worked with Cockerell to develop the idea further.

The first passenger-carrying hovercraft to enter service was the Vickers VA-3, which, in the summer of 1962, carried passengers regularly along the north Wales coast from Moreton, Merseyside, to Rhyl

Rhyl (; cy, Y Rhyl, ) is a seaside town and community in Denbighshire, Wales. The town lies within the historic boundaries of Flintshire, on the north-east coast of Wales at the mouth of the River Clwyd ( Welsh: ''Afon Clwyd'').

To the we ...

. It was powered by two turboprop

A turboprop is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.

A turboprop consists of an intake, reduction gearbox, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air enters the intake and is compressed by the compressor. ...

aero-engines and driven by propellers

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

.

During the 1960s, Saunders-Roe developed several larger designs that could carry passengers, including the SR.N2, which operated across the

During the 1960s, Saunders-Roe developed several larger designs that could carry passengers, including the SR.N2, which operated across the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay t ...

, in 1962, and later the SR.N6

The Saunders-Roe (later British Hovercraft Corporation) SR.N6 hovercraft (also known as the ''Winchester'' class) was essentially a larger version of the earlier SR.N5 series. It incorporated several features that resulted in the type becoming ...

, which operated across the Solent from Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre. Southsea is not a separate town as all of Portsea Island's s ...

to Ryde

Ryde is an English seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight. The built-up area had a population of 23,999 according to the 2011 Census and an estimate of 24,847 in 2019. Its growth as a seaside resort came af ...

on the Isle of Wight for many years. In 1963 the SR.N2 was used in experimental service between Weston-super-Mare

Weston-super-Mare, also known simply as Weston, is a seaside town in North Somerset, England. It lies by the Bristol Channel south-west of Bristol between Worlebury Hill and Bleadon Hill. It includes the suburbs of Mead Vale, Milton, Oldmix ...

and Penarth under the aegis of P & A Campbell, the paddle steamer operators.

Operations by Hovertravel

Hovertravel is a ferry company operating from Southsea, Portsmouth to Ryde, Isle of Wight, UK. It is the only passenger hovercraft company currently operating in Britain since Hoverspeed stopped using its craft in favour of catamarans and sub ...

commenced on 24 July 1965, using the SR.N6, which carried 38 passengers. Two 98 seat AP1-88

The British Hovercraft Corporation AP1-88 is a medium-size hovercraft. In a civil configuration, the hovercraft can seat a maximum of 101 passengers, while as a troop carrier, it can transport up to 90 troops. When operated as a military logistic ...

hovercraft were introduced on this route in 1983, and in 2007, these were joined by the first 130-seat BHT130

{{Use British English, date=May 2017

The Griffon Hoverwork BHT130 is a medium-size hovercraft, designed by Hoverwork and fitted out in St Helens.

The type was found to be unsuitable and was withdrawn after 4 years in service (2007-2011).

As ...

craft. The AP1-88 and the BHT130 were notable as they were largely built by Hoverwork using shipbuilding techniques and materials (i.e. welded aluminium structure and diesel engines) rather than the aircraft techniques used to build the earlier craft built by Saunders-Roe-British Hovercraft Corporation. Over 20 million passengers had used the service as of 2004 – the service is still operating () and is by far the longest, continuously operated hovercraft service.

In 1966, two cross-channel passenger hovercraft services were inaugurated using SR.N6 hovercraft. Hoverlloyd

Hoverlloyd operated a cross-Channel hovercraft service between Ramsgate, England and Calais, France.

Originally registered as ''Cross-Channel Hover Services Ltd'' in 1965, the company was renamed Hoverlloyd the following year. It was initially ...

ran services from Ramsgate Harbour, England, to Calais, France, and Townsend Ferries also started a service to Calais from Dover, which was soon superseded by that of Seaspeed

Seaspeed was a British hovercraft operator which ran services in the Solent and English Channel between 1965 and 1981, when it merged with a rival to form Hoverspeed.

Seaspeed was a jointly owned subsidiary of railway companies British Rail ( ...

.

As well as Saunders-Roe and Vickers (which combined in 1966 to form the British Hovercraft Corporation (BHC)), other commercial craft were developed during the 1960s in the UK by Cushioncraft

Cushioncraft Ltd was a British engineering company, formed in 1960 as a division of Britten-Norman Ltd (manufacturer of aircraft) to develop/build hovercraft. Originally based at Bembridge Airport on the Isle of Wight, Cushioncraft later moved t ...

(part of the Britten-Norman Group) and Hovermarine based at Woolston (the latter being '' sidewall hovercraft'', where the sides of the hull projected down into the water to trap the cushion of air with normal hovercraft skirts at the bow and stern). One of these models, the HM-2, was used by Red Funnel

Red Funnel, the trading name of the Southampton Isle of Wight and South of England Royal Mail Steam Packet Company Limited,Woolston Floating Bridge

The Woolston Floating Bridge was a cable ferry that crossed the River Itchen in England between hards at Woolston and Southampton from 23 November 1836 until 11 June 1977. It was taken out of service after the new Itchen Bridge was opened.

...

) and Cowes.

The world's first car-carrying hovercraft was made in 1968, the BHC ''Mountbatten'' class (SR.N4) models, each powered by four Bristol Proteus

The world's first car-carrying hovercraft was made in 1968, the BHC ''Mountbatten'' class (SR.N4) models, each powered by four Bristol Proteus turboshaft

A turboshaft engine is a form of gas turbine that is optimized to produce shaftpower rather than jet thrust. In concept, turboshaft engines are very similar to turbojets, with additional turbine expansion to extract heat energy from the exhaust ...

engines. These were both used by rival operators Hoverlloyd

Hoverlloyd operated a cross-Channel hovercraft service between Ramsgate, England and Calais, France.

Originally registered as ''Cross-Channel Hover Services Ltd'' in 1965, the company was renamed Hoverlloyd the following year. It was initially ...

and Seaspeed

Seaspeed was a British hovercraft operator which ran services in the Solent and English Channel between 1965 and 1981, when it merged with a rival to form Hoverspeed.

Seaspeed was a jointly owned subsidiary of railway companies British Rail ( ...

(which joined to form Hoverspeed

Hoverspeed was a ferry company that operated on the English Channel from 1981 until 2005. It was formed in 1981 by the merger of Seaspeed and Hoverlloyd. Its last owners were Sea Containers; the company ran a small fleet of two high-speed Sea ...

in 1981) to operate regular car and passenger carrying services across the English Channel. Hoverlloyd operated from Ramsgate, where a special hoverport

A hoverport is a terminal for hovercraft, having passenger facilities where needed and infrastructure to allow the hovercraft to come on land. Today, only a small number of civilian hoverports remain, due to the relatively high fuel consumption ...

had been built at Pegwell Bay, to Calais. Seaspeed operated from Dover, England, to Calais and Boulogne in France. The first SR.N4 had a capacity of 254 passengers and 30 cars, and a top speed of . The channel crossing took around 30 minutes and was run like an airline with flight numbers. The later SR.N4 Mk.III had a capacity of 418 passengers and 60 cars. These were later joined by the French-built SEDAM N500 Naviplane

The N500 Naviplane was a French hovercraft built by SEDAM (''Société d'Etude et de Développement des Aéroglisseurs Marins'') in Pauillac, Gironde for the cross channel route. Intended to have a large passenger and crew capacity, it was for a ...

with a capacity of 385 passengers and 45 cars; only one entered service and was used intermittently for a few years on the cross-channel service until returned to SNCF in 1983. The service ceased on 1 October 2000 after 32 years, due to competition with traditional ferries, catamarans, the disappearance of duty-free shopping within the EU, the advancing age of the SR.N4 hovercraft, and the opening of the Channel Tunnel.

The commercial success of hovercraft suffered from rapid rises in fuel prices during the late 1960s and 1970s, following conflict in the Middle East. Alternative over-water vehicles, such as wave-piercing catamarans (marketed as the SeaCat Seacat may refer to:

* Seacat missile, a short-range surface-to-air missile system

* SeaCat (1992–2004), ferry company formerly operating from between Northern Ireland, Scotland and England

* The Sea-Cat, an imaginary monster from Flann O'Brien' ...

in the UK until 2005), use less fuel and can perform most of the hovercraft's marine tasks. Although developed elsewhere in the world for both civil and military purposes, except for the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay t ...

Ryde-to-Southsea crossing, hovercraft disappeared from the coastline of Britain until a range of Griffon Hoverwork

Griffon Hoverwork Ltd (GHL) is a British hovercraft designer and manufacturer.

It was originally founded as Griffon Hovercraft Ltd in 1976, based in Southampton. The firm set about the development of its own product range, launching its first ...

were bought by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

and CBD Belapur

The Central Business District of Belapur (C.B.D Belapur) is a node of Navi Mumbai. The Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation is headquartered in Belapur. The Reserve Bank of India maintains a branch office at CBD Belapur. This area is one of the ...

and Vashi

Juhu Vashi (Pronunciation: �aːʃiː is an upmarket residential and commercial node in Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, across the Thane Creek of the Arabian Sea on the outskirts of city of Mumbai. The Juhu Vashi is named after the largest village ...

in Navi Mumbai

Navi Mumbai (), is a planned city situated on the west coast of the Indian subcontinent, located in the Konkan division of Maharashtra state, on the mainland of India.

Navi Mumbai is part of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR). The city i ...

between 1994 and 1999, but the services were subsequently stopped due to the lack of sufficient water transport infrastructure Marine architecture is the design of architectural and engineering structures which support coastal design, near-shore and off-shore or deep-water planning for many projects such as shipyards, ship transport, coastal management or other marine and/o ...

.

Civilian non-commercial

In Finland, small hovercraft are widely used in maritime rescue and during the rasputitsa ("mud season") as

In Finland, small hovercraft are widely used in maritime rescue and during the rasputitsa ("mud season") as archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Arc ...

liaison vehicles. In England, hovercraft of the Burnham-on-Sea

Burnham-on-Sea is a seaside town in Somerset, England, at the mouth of the River Parrett, upon Bridgwater Bay. Burnham was a small fishing village until the late 18th century when it began to grow because of its popularity as a seaside resort. ...

Area Rescue Boat (BARB) are used to rescue people from thick mud in Bridgwater Bay

Bridgwater Bay is on the Bristol Channel, north of Bridgwater in Somerset, England at the mouth of the River Parrett and the end of the River Parrett Trail. It stretches from Minehead at the southwestern end of the bay to Brean Down in the nor ...

. Avon Fire and Rescue Service

Avon Fire & Rescue Service (AF&RS) is the fire and rescue service covering the unitary authorities of Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol, North Somerset, and South Gloucestershire in South West England.

The headquarters of the service is co ...

became the first Local Authority fire service in the UK to operate a hovercraft. It is used to rescue people from thick mud in the Weston-super-Mare

Weston-super-Mare, also known simply as Weston, is a seaside town in North Somerset, England. It lies by the Bristol Channel south-west of Bristol between Worlebury Hill and Bleadon Hill. It includes the suburbs of Mead Vale, Milton, Oldmix ...

area and during times of inland flooding. A Griffon rescue Hovercraft has been in use for a number of years with the Airport Fire Service at Dundee Airport in Scotland. It is used in the event of an aircraft ditching in the Tay estuary. Numerous fire departments around the US/Canadian Great Lakes operate hovercraft for water and ice rescues, often of ice fisherman stranded when ice breaks off from shore. The Canadian Coast Guard uses hovercraft to break light ice.

In October 2008, The Red Cross commenced a flood-rescue service hovercraft based in Inverness, Scotland. Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service received two flood-rescue hovercraft donated by

In October 2008, The Red Cross commenced a flood-rescue service hovercraft based in Inverness, Scotland. Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service received two flood-rescue hovercraft donated by Severn Trent Water

Severn Trent plc is a water company based in Coventry, England. It supplies 4.6 million households and business across the Midlands and Wales.

It is traded on the London Stock Exchange and a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index. Severn Trent, the ...

following the 2007 UK floods.

Since 2006, hovercraft have been used in aid in Madagascar by HoverAid, an international NGO who use the hovercraft to reach the most remote places on the island.

The Scandinavian airline SAS used to charter an AP1-88 hovercraft for regular passengers between Copenhagen Airport

Copenhagen Airport, Kastrup ( da, Københavns Lufthavn, Kastrup, ; ) is an international airport serving Copenhagen, Denmark, Zealand, the Øresund Region, and southern Sweden including Scania. It is the second largest airport in the Nordic ...

, Denmark, and the SAS Hovercraft Terminal

Terminal may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Terminal (electronics), a device for joining electrical circuits together

* Terminal (telecommunication), a device communicating over a line

* Computer terminal, a set of primary input and output dev ...

in Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal pop ...

, Sweden.

In 1998, the US Postal Service began using the British built Hoverwork AP1-88

The British Hovercraft Corporation AP1-88 is a medium-size hovercraft. In a civil configuration, the hovercraft can seat a maximum of 101 passengers, while as a troop carrier, it can transport up to 90 troops. When operated as a military logistic ...

to haul mail, freight, and passengers from Bethel, Alaska

Bethel ( esu, Mamterilleq) is a city in Bethel Census Area, Alaska, Bethel Census Area, Alaska, United States. It is the largest community on the Kuskokwim River, located approximately upriver from where the river flows into Kuskokwim Bay. It ...

, to and from eight small villages along the Kuskokwim River

The Kuskokwim River or Kusko River ( Yup'ik: ''Kusquqvak''; Deg Xinag: ''Digenegh''; Upper Kuskokwim: ''Dichinanek' ''; russian: Кускоквим (''Kuskokvim'')) is a river, long, in Southwest Alaska in the United States. It is the ninth l ...

. Bethel is far removed from the Alaska road system, thus making the hovercraft an attractive alternative to the air based delivery methods used prior to introduction of the hovercraft service. Hovercraft service is suspended for several weeks each year while the river is beginning to freeze to minimize damage to the river ice surface. The hovercraft is able to operate during the freeze-up period; however, this could potentially break the ice and create hazards for villagers using their snowmobiles along the river during the early winter.

In 2006, Kvichak Marine Industries of Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, US built, under license, a cargo/passenger version of the Hoverwork BHT130

{{Use British English, date=May 2017

The Griffon Hoverwork BHT130 is a medium-size hovercraft, designed by Hoverwork and fitted out in St Helens.

The type was found to be unsuitable and was withdrawn after 4 years in service (2007-2011).

As ...

. Designated 'Suna-X', it is used as a high speed ferry for up to 47 passengers and of freight serving the remote Alaskan villages of King Cove and Cold Bay

Cold Bay ( ale, Udaamagax,; Sugpiaq: ''Pualu'') is a city in Aleutians East Borough, Alaska, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 108, but at the 2020 census this had reduced to 50.

Cold Bay is one of the main commercial ...

.

An experimental service was operated in Scotland across the Firth of Forth (between Kirkcaldy and Portobello, Edinburgh

Portobello is a coastal suburb of Edinburgh in eastern central Scotland. It lies 3 miles (5 km) east of the city centre, facing the Firth of Forth, between the suburbs of Joppa and Craigentinny. Although historically it was a town in it ...

), from 16 to 28 July 2007. Marketed as ''Forthfast'', the service used a craft chartered from Hovertravel

Hovertravel is a ferry company operating from Southsea, Portsmouth to Ryde, Isle of Wight, UK. It is the only passenger hovercraft company currently operating in Britain since Hoverspeed stopped using its craft in favour of catamarans and sub ...

and achieved an 85% passenger load factor

Passenger load factor, or load factor, measures the capacity utilization of public transport services like airlines, passenger railways, and intercity bus services. It is generally used to assess how efficiently a transport provider fills seats ...

. , the possibility of establishing a permanent service is still under consideration.

Since the channel routes abandoned hovercraft, and pending any reintroduction on the Scottish route, the United Kingdom's only public hovercraft service is that operated by Hovertravel

Hovertravel is a ferry company operating from Southsea, Portsmouth to Ryde, Isle of Wight, UK. It is the only passenger hovercraft company currently operating in Britain since Hoverspeed stopped using its craft in favour of catamarans and sub ...

between Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre. Southsea is not a separate town as all of Portsea Island's s ...

(Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

) and Ryde

Ryde is an English seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight. The built-up area had a population of 23,999 according to the 2011 Census and an estimate of 24,847 in 2019. Its growth as a seaside resort came af ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

.

From the 1960s, several commercial lines were operated in Japan, without much success. In Japan the last commercial line had linked Ōita Airport

Oita often refers to:

*Ōita Prefecture, Kyushu, Japan

*Ōita (city), the capital of the prefecture

Oita or Ōita may also refer to:

Places

*Ōita District, Ōita, a former district in Ōita Prefecture, Japan

*Ōita Stadium, a multi-use stadium ...

and central Ōita but was shut down in October 2009.

Hovercraft are still manufactured in the UK, near to where they were first conceived and tested, on the Isle of Wight. They can also be chartered for a wide variety of uses including inspections of shallow bed offshore wind farms and VIP or passenger use. A typical vessel would be a Tiger IV or a Griffon. They are light, fast, road transportable and very adaptable with the unique feature of minimising damage to environments.

Hovercraft are still manufactured in the UK, near to where they were first conceived and tested, on the Isle of Wight. They can also be chartered for a wide variety of uses including inspections of shallow bed offshore wind farms and VIP or passenger use. A typical vessel would be a Tiger IV or a Griffon. They are light, fast, road transportable and very adaptable with the unique feature of minimising damage to environments.

Military

The first application of the hovercraft for military use was by the British Armed Forces, using hovercraft built by Saunders-Roe. In 1961, the United Kingdom set up the Interservice Hovercraft Trials Unit (IHTU) based at

The first application of the hovercraft for military use was by the British Armed Forces, using hovercraft built by Saunders-Roe. In 1961, the United Kingdom set up the Interservice Hovercraft Trials Unit (IHTU) based at RNAS Lee-on-Solent (HMS Daedalus)

Royal Naval Air Station Lee-on-Solent (HMS ''Daedalus'') was one of the primary shore airfields of the Fleet Air Arm. First established as a seaplane base in 1917 during the First World War, it later became the main training establishment and ad ...

, now the site of the Hovercraft Museum

The Hovercraft Museum, in Lee-on-the-Solent, Hampshire, England is a museum run by a registered charity dedicated to hovercraft.

The museum has a collection of over 60 hovercraft of various designs. Situated at HMS ''Daedalus'' by the larg ...

, near Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. This unit carried out trials on the SR.N1 from Mk1 through Mk5 as well as testing the SR.N2, SR.N3, SR.N5 and SR.N6

The Saunders-Roe (later British Hovercraft Corporation) SR.N6 hovercraft (also known as the ''Winchester'' class) was essentially a larger version of the earlier SR.N5 series. It incorporated several features that resulted in the type becoming ...

craft. The Hovercraft Trials Unit (Far East) was established by the Royal Navy at Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

in August 1964 with two armed hovercraft; they were deployed later that year to Tawau

Tawau (, Jawi: , ), formerly known as Tawao, is the capital of the Tawau District in Sabah, Malaysia. It is the third-largest city in Sabah, after Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan. It is located on the Semporna Peninsula in the southeast coast of t ...

in Malaysian Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and ea ...

and operated on waterways there during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation. The hovercraft's inventor, Sir Christopher Cockerell

Sir Christopher Sydney Cockerell CBE RDI FRS (4 June 1910 – 1 June 1999) was an English engineer, best known as the inventor of the hovercraft.

Early life and education

Cockerell was born in Cambridge, where his father, Sir Sydney Cocke ...

, claimed late in his life that the Falklands War could have been won far more easily had the British military shown more commitment to the hovercraft; although earlier trials had been conducted in the Falkland Islands with an SRN-6, the hovercraft unit had been disbanded by the time of the conflict. Currently, the Royal Marines use the Griffonhoverwork 2400TD hovercraft, the replacement for the Griffon 2000 TDX Class ACV, which was deployed operationally by the marines in the 2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

.

In the US, during the 1960s, Bell

A bell is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be made by an inte ...

licensed and sold the Saunders-Roe SR.N5 as the Bell SK-5. They were deployed on trial to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

as '' PACV'' patrol craft

A patrol boat (also referred to as a patrol craft, patrol ship, or patrol vessel) is a relatively small naval vessel generally designed for coastal defence, border security, or law enforcement. There are many designs for patrol boats, and the ...

in the Mekong Delta where their mobility

Mobility may refer to:

Social sciences and humanities

* Economic mobility, ability of individuals or families to improve their economic status

* Geographic mobility, the measure of how populations and goods move over time

* Mobilities, a conte ...

and speed

In everyday use and in kinematics, the speed (commonly referred to as ''v'') of an object is the magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (ma ...

was unique. This was used in both the UK SR.N5 curved deck configuration and later with modified flat deck, gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

and grenade launcher designated the 9255 PACV. The United States Army also experimented with the use of SR.N5 hovercraft in Vietnam. Three hovercraft with the flat deck configuration were deployed to Đồng Tâm in the Mekong Delta region and later to Ben Luc. They saw action primarily in the Plain of Reeds. One was destroyed in early 1970 and another in August of that same year, after which the unit was disbanded. The only remaining U.S. Army SR.N5 hovercraft is currently on display in the Army Transport Museum in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. Experience led to the proposed Bell SK-10, which was the basis for the LCAC-class air-cushioned landing craft

An air-cushioned landing craft, also called an LCAC ( landing craft, air cushioned), is a modern variation on the amphibious landing boat. The majority of these craft are small- to mid-sized multi-purpose hovercraft, also known as "over the bea ...

now deployed by the U.S. and Japanese Navy. Developed and tested in the mid-1970s, the LACV-30

The LACV-30 (Lighter Air Cushion Vehicle, 30 tons) was a hovercraft used by the U.S. Army Mobility Equipment Research and Development Command (MERADCOM) for offloading cargo from amphibious ships. For logistic transport, the Army was already usin ...

was used by the US Army to transport military cargo in logistics-over-the-shore operations from the early 1980s until the mid-1990s.

The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

was the world's largest developer of military hovercraft. Their designs range from the small Czilim class ACV

The Czilim-class ACV (Project 20910) is a small patrol hovercraft operated by the Border Guard Service of Russia.

Configuration

The Czilim class is the first new class of military hovercraft developed for the Russian military since the fall o ...

, comparable to the SR.N6, to the monstrous Zubr class LCAC

The Zubr class, Soviet designation Project 1232.2, (NATO reporting name "Pomornik") is a class of Soviet-designed air-cushioned landing craft (LCAC). The name "Żubr" is Polish for the European bison. This class of military hovercraft is, , th ...

, the world's largest hovercraft. The Soviet Union was also one of the first nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective Identity (social science), identity of a group of people unde ...

s to use a hovercraft, the Bora, as a guided missile corvette, though this craft possessed rigid, non-inflatable sides. With the fall of the Soviet Union, most Soviet military hovercraft fell into disuse and disrepair. Only recently has the modern Russian Navy begun building new classes of military hovercraft.

The Iranian Navy

, ''Daryādelān''"Seahearts"

, patron =

, motto = fa, راه ما، راه حسین است, ''Rāh-e ma, rāh-e hoseyn ast''"''Our Path, Is Hussain's Path''"

, colors =

...

operates multiple British-made and some Iranian-produced hovercraft. The Tondar or Thunderbolt comes in varieties designed for combat and transportation. Iran has equipped the Tondar with mid-range missiles, machine guns and retrievable reconnaissance drones. Currently they are used for water patrols and combat against drug smugglers.

The Finnish Navy

The Finnish Navy ( fi, Merivoimat, sv, Marinen) is one of the branches of the Finnish Defence Forces. The navy employs 2,300 people and about 4,300 conscripts are trained each year. Finnish Navy vessels are given the ship prefix "FNS", short f ...

designed an experimental missile attack hovercraft class, Tuuli class hovercraft, in the late 1990s. The prototype of the class, ''Tuuli'', was commissioned in 2000. It proved an extremely successful design for a littoral

The littoral zone or nearshore is the part of a sea, lake, or river that is close to the shore. In coastal ecology, the littoral zone includes the intertidal zone extending from the high water mark (which is rarely inundated), to coastal a ...

fast attack craft, but due to fiscal reasons and doctrinal change in the Navy, the hovercraft was soon withdrawn.

The People's Army Navy of China operates the Jingsah II class LCAC. This troop and equipment carrying hovercraft is roughly the Chinese equivalent of the U.S. Navy LCAC

LCAC may refer to:

Hovercraft

* A generic term for an air cushioned landing craft, taken from US Navy designation "Landing Craft, Air Cushion".

** Landing Craft Air Cushion, a US Navy hull classification symbol for the Landing Craft Air Cushion-c ...

.

Recreational/sport

Small commercially manufactured, kit or plan-built hovercraft are increasingly being used for recreational purposes, such as inland racing and cruising on inland lakes and rivers, marshy areas, estuaries and inshore coastal waters. The Hovercraft Cruising Club supports the use of hovercraft for cruising in coastal and inland waterways, lakes and lochs. The Hovercraft Club of Great Britain, founded in 1966, regularly organizes inland and coastal hovercraft race events at various venues across the United Kingdom. Similar events are also held in Europe and the US.Other uses

Hoverbarge

A real benefit of air cushion vehicles in moving heavy loads over difficult terrain, such as swamps, was overlooked by the excitement of the British Government funding to develop high-speed hovercraft. It was not until the early 1970s that the technology was used for moving a modular marine barge with a dragline on board for use over soft reclaimed land. Mackace (Mackley Air Cushion Equipment), now known as Hovertrans, produced a number of successful Hoverbarges, such as the 250 ton payload "Sea Pearl", which operated in Abu Dhabi, and the twin 160 ton payload "Yukon Princesses", which ferried trucks across the Yukon River to aid the pipeline build. Hoverbarges are still in operation today. In 2006, Hovertrans (formed by the original managers of Mackace) launched a 330-ton payload drilling barge in the swamps of Suriname. The Hoverbarge technology is somewhat different from high-speed hovercraft, which has traditionally been constructed using aircraft technology. The initial concept of the air cushion barge has always been to provide a low-tech amphibious solution for accessing construction sites using typical equipment found in this area, such as diesel engines, ventilating fans, winches and marine equipment. The load to move a 200 ton payload ACV barge at would only be 5 tons. The skirt and air distribution design on high-speed craft again is more complex, as they have to cope with the air cushion being washed out by a wave and wave impact. The slow speed and large mono chamber of the hover barge actually helps reduce the effect of wave action, giving a very smooth ride. The low pull force enabled a Boeing 107helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

to pull a hoverbarge across snow, ice and water in 1982.

Hovertrains

Several attempts have been made to adopt air cushion technology for use in fixed track systems, in order to use the lower frictional forces for delivering high speeds. The most advanced example of this was theAérotrain

The Aérotrain was an experimental Tracked Air Cushion Vehicle

(TACV), or hovertrain, developed in France from 1965 to 1977 under the engineering leadership of Jean Bertin (1917–1975) – and intended to bring the French rail network to the c ...

, an experimental high speed hovertrain

A hovertrain is a type of high-speed train that replaces conventional steel wheels with hovercraft lift pads, and the conventional railway bed with a paved road-like surface, known as the ''track'' or ''guideway''. The concept aims to eliminat ...

built and operated in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

between 1965 and 1977. The project was abandoned in 1977 due to lack of funding, the death of its lead engineer and the adoption of the TGV

The TGV (french: Train à Grande Vitesse, "high-speed train"; previously french: TurboTrain à Grande Vitesse, label=none) is France's intercity high-speed rail service, operated by SNCF. SNCF worked on a high-speed rail network from 1966 to 19 ...

by the French government as its high-speed ground transport solution.

A test track for a tracked hovercraft system was built at Earith