Divan Japonais LACMA 59.80.19.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meaning "Oriental council of a state", comes from Turkish language, Turkish ''divan'', from Arabic ''diwan''.

It is first attested in Middle Persian spelled as ''dpywʾn'' and ''dywʾn'', itself hearkening back, via Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian language, Akkadian, ultimately to Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet. The word was borrowed into Armenian language, Armenian as well as ''divan''; on linguistic grounds this is placed after the 3rd century, which helps establish the original Middle Persian (and eventually New Persian) form was ''dīvān'', not ''dēvān'', despite later legends that traced the origin of the word to the latter form. The variant pronunciation ''dēvān'' however did exist, and is the form surviving to this day in Tajiki Persian.

In Arabic, the term was first used for the army registers, then generalized to any register, and by metonymy applied to specific government departments. The sense of the word evolved to "custom house" and "council chamber", then to "long, cushioned seat", such as are found along the walls in Middle-Eastern council chambers. The latter is the sense that entered European languages as divan (furniture).

The modern French, Dutch, Spanish, and Italian words ''douane'', ''aduana'', and ''dogana,'' respectively (meaning "customs house"), also come from ''diwan''.

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meaning "Oriental council of a state", comes from Turkish language, Turkish ''divan'', from Arabic ''diwan''.

It is first attested in Middle Persian spelled as ''dpywʾn'' and ''dywʾn'', itself hearkening back, via Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian language, Akkadian, ultimately to Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet. The word was borrowed into Armenian language, Armenian as well as ''divan''; on linguistic grounds this is placed after the 3rd century, which helps establish the original Middle Persian (and eventually New Persian) form was ''dīvān'', not ''dēvān'', despite later legends that traced the origin of the word to the latter form. The variant pronunciation ''dēvān'' however did exist, and is the form surviving to this day in Tajiki Persian.

In Arabic, the term was first used for the army registers, then generalized to any register, and by metonymy applied to specific government departments. The sense of the word evolved to "custom house" and "council chamber", then to "long, cushioned seat", such as are found along the walls in Middle-Eastern council chambers. The latter is the sense that entered European languages as divan (furniture).

The modern French, Dutch, Spanish, and Italian words ''douane'', ''aduana'', and ''dogana,'' respectively (meaning "customs house"), also come from ''diwan''.

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

A divan or diwan ( fa, دیوان, ''dīvān''; from Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet) was a high government ministry in various Islamic states, or its chief official (see ''dewan'').

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meaning "Oriental council of a state", comes from Turkish language, Turkish ''divan'', from Arabic ''diwan''.

It is first attested in Middle Persian spelled as ''dpywʾn'' and ''dywʾn'', itself hearkening back, via Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian language, Akkadian, ultimately to Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet. The word was borrowed into Armenian language, Armenian as well as ''divan''; on linguistic grounds this is placed after the 3rd century, which helps establish the original Middle Persian (and eventually New Persian) form was ''dīvān'', not ''dēvān'', despite later legends that traced the origin of the word to the latter form. The variant pronunciation ''dēvān'' however did exist, and is the form surviving to this day in Tajiki Persian.

In Arabic, the term was first used for the army registers, then generalized to any register, and by metonymy applied to specific government departments. The sense of the word evolved to "custom house" and "council chamber", then to "long, cushioned seat", such as are found along the walls in Middle-Eastern council chambers. The latter is the sense that entered European languages as divan (furniture).

The modern French, Dutch, Spanish, and Italian words ''douane'', ''aduana'', and ''dogana,'' respectively (meaning "customs house"), also come from ''diwan''.

The word, recorded in English since 1586, meaning "Oriental council of a state", comes from Turkish language, Turkish ''divan'', from Arabic ''diwan''.

It is first attested in Middle Persian spelled as ''dpywʾn'' and ''dywʾn'', itself hearkening back, via Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian language, Akkadian, ultimately to Sumerian language, Sumerian ''dub'', clay tablet. The word was borrowed into Armenian language, Armenian as well as ''divan''; on linguistic grounds this is placed after the 3rd century, which helps establish the original Middle Persian (and eventually New Persian) form was ''dīvān'', not ''dēvān'', despite later legends that traced the origin of the word to the latter form. The variant pronunciation ''dēvān'' however did exist, and is the form surviving to this day in Tajiki Persian.

In Arabic, the term was first used for the army registers, then generalized to any register, and by metonymy applied to specific government departments. The sense of the word evolved to "custom house" and "council chamber", then to "long, cushioned seat", such as are found along the walls in Middle-Eastern council chambers. The latter is the sense that entered European languages as divan (furniture).

The modern French, Dutch, Spanish, and Italian words ''douane'', ''aduana'', and ''dogana,'' respectively (meaning "customs house"), also come from ''diwan''.

Creation and development under the early Caliphates

Establishment and Umayyad period

The first ''dīwān'' was created under Caliph Umar ( CE) in 15 Anno Hegirae, A.H. (636/7 CE) or, more likely, 20 A.H. (641 CE). It comprised the names of the warriors of Medina who participated in the Muslim conquests and their families, and was intended to facilitate the payment of salary (''ʿaṭāʾ'', in coin or in rations) to them, according to their service and their relationship to Muhammad. This first army register (''dīwān jund, al-jund'') was soon emulated in other provincial capitals like Basra, Kufa and Fustat. Al-Mughira ibn Shu'ba, a statesman from the Banu Thaqif, Thaqif tribe who was versed in Middle Persian, Persian, is credited with establishing Basra's ''dīwān'' during his governorship (636–638), and the ''dīwān'' of the Caliphate's other garrison centers followed its organization. With the advent of the Umayyad Caliphate, the number of ''dīwāns'' increased. To the ''dīwān al-jund'', the first Umayyad dynasty, Umayyad caliph, Mu'awiya (r. 661–680), added the bureau of the land tax (''dīwān kharaj, al-kharāj'') in Damascus, which became the main ''dīwān'', as well as the bureau of correspondence (''dīwān al-rasāʾil''), which drafted the caliph's letters and official documents, and the bureau of the seal (''dīwān al-khātam''), which checked and kept copies of all correspondence before sealing and dispatching it. A number of more specialist departments were also established, probably by Mu'awiya: the ''dīwān al-barīd'' in charge of the Barid (caliphate), postal service; the bureau of expenditure (''dīwān al-nafaqāt''), which most likely indicates the survival of a Byzantine institution; the ''dīwān al-ṣadaqa'' was a new foundation with the task of estimating the ''zakat, zakāt'' and ''ushr (tax), ʿushr'' levies; the ''dīwān al-mustaghallāt'' administered state property in cities; the ''dīwān al-ṭirāz'' controlled the government workshops that made official banners, costumes and some furniture. Aside from the central government, there was a local branch of the ''dīwān al-kharāj'', the ''dīwān al-jund'' and the ''dīwān al-rasāʾil'' in every province. Under Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, Abd al-Malik (), the practices of the various departments began to be standardized and Arabized: instead of the local languages (Greek language, Greek in Bilad al-Sham, Syria, Coptic language, Coptic and Greek in Medieval Egypt, Egypt, Persian in the former Sasanian Empire, Sasanian lands) and the traditional practices of book-keeping, seals and time-keeping, only Arabic and the Islamic calendar were to be used henceforth. The process of Arabization was gradual: in Iraq, the transition was carried out by Salih ibn Abd al-Rahman under the auspices of the governor al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf in 697, in Syria by Sulayman ibn Sa'd al-Khushani in 700, in Egypt under Caliph al-Walid I's governor Abdallah ibn Abd al-Malik in 706, and in Greater Khorasan, Khurasan by Ishaq ibn Tulayq al-Nahshali on the orders of Yusuf ibn Umar al-Thaqafi, governor of Iraq, in 741/42.Abbasid period

Under the Abbasid Caliphate the administration, partly under the increasing influence of Sassanid Persia, Iranian culture, became more elaborate and complex. As part of this process, the ''dīwāns'' increased in number and sophistication, reaching their apogee in the 9th–10th centuries. At the same time, the office of vizier (''wazīr'') was also created to coordinate government. The administrative history of the Abbasid ''dīwāns'' is complex, since many were short-lived, temporary establishments for specific needs, while at times the sections of larger ''dīwān'' might also be termed ''dīwāns'', and often a single individual was placed in charge of more than one department. Caliph al-Saffah (r. 749–754) established a department for the confiscated properties of the Umayyads after his victory in the Abbasid Revolution. This was probably the antecedent of the later ''dīwān al-ḍiyāʿ'', administering the caliph's personal domains. Similarly, under al-Mansur (r. 754–775) there was a bureau of confiscations (''dīwān al-muṣādara''), as well as a ''dīwān al-aḥshām'', probably in charge of palace service personnel, and a bureau of petitions to the Caliph (''dīwān al-riḳāʿ''). Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785) created a parallel ''dīwān al-zimām'' (control bureau) for every one of the existing ''dīwāns'', as well as a central control bureau (''zimām al-azimma''). These acted as comptrollers as well as coordinators between the various bureaus, or between individual ''dīwāns'' and the vizier. In addition, a ''dīwān al-maẓālim'' was created, staffed by judges, to hear complaints against government officials. The remit of the ''dīwān al-kharāj'' now included all land taxes (''kharāj'', ''zakāt'', and ''jizya'', both in money and in kind), while another department, the ''dīwān al-ṣadaqa'', dealt with assessing the ''zakāt'' of cattle. The correspondence of the ''dīwān al-kharāj'' was checked by another department, the ''dīwān al-khātam''. As in Umayyad times, miniature copies of the ''dīwān al-kharāj'', the ''dīwān al-jund'' and the ''dīwān al-rasāʾil'' existed in every province, but by the mid-9th century each province also maintained a branch of its ''dīwān al-kharāj'' in the capital. The treasury department (''bayt al-māl'' or ''dīwān al-sāmī'') kept the records of revenue and expenditure, both in money and in kind, with specialized ''dīwāns'' for each category of the latter (e.g. cereals, cloth, etc.). Its secretary had to mark all orders of payment to make them valid, and it drew up monthly and yearly balance sheets. The ''dīwān al-jahbad̲ha'', responsible for the treasury's balance sheets, was eventually branched off from it, while the treasury domains were placed under the ''dīwān al-ḍiyāʿ'', of which there appear at times to have been several. In addition, a department of confiscated property (''dīwān al-musādarīn'') and confiscated estates (''dīwān al-ḍiyāʿ al-maqbūḍa'') existed. Caliph al-Mu'tadid (r. 892–902) grouped the branches of the provincial ''dīwāns'' present in the capital into a new department, the ''dīwān al-dār'' (bureau of the palace) or ''dīwān al-dār al-kabīr'' (great bureau of the palace), where "''al-dār''" probably meant the vizier's palace. At the same time, the various ''zimām'' bureaux were combined into a single ''dīwān al-zimām'' which re-checked all assessments, payments and receipts against its own records and, according to the 11th-century scholar al-Mawardi, was the "guardian of the rights of ''bayt al-māl'' [the treasury] and the people". The ''dīwān al-nafaḳāt'' played a similar role with regards to expenses by the individual ''dīwāns'', but by the end of the 9th century its role was mostly restricted to the finances of the caliphal palace. Under al-Muktafi (r. 902–908) the ''dīwān al-dār'' was broken up into three departments, the bureaux of the eastern provinces (''dīwān Mashriq, al-mashriq''), of the western provinces (''dīwān Maghrib, al-maghrib''), and of the Iraq (''dīwān Sawad, al-sawād''), although under al-Muqtadir (r. 908–932) the ''dīwān al-dār'' still existed, with the three territorial departments considered sections of the latter. In 913/4, the vizier Ali ibn Isa al-Jarrah, Ali ibn Isa established a new department for charitable endowments (''dīwān al-birr''), whose revenue went to the upkeep of holy places, the Haram (site), two holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and on volunteers fighting in the holy war against the Byzantine Empire. Under Caliph al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861), a bureau of servants and pages (''dīwān mawali, al-mawālī wa ghilman, ’l-ghilmān''), possibly an evolution of the ''dīwān al-aḥshām'', existed for the huge number of slaves and other attendants of the palace. In addition, the ''dīwān al-khātam'', now also known as the ''dīwān al-sirr'' (bureau of confidential affairs) grew in importance. Miskawayh also mentions the existence of a '' dīwān al-ḥaram'', which supervised the women's quarters of the palace.Later Islamic dynasties

As the Abbasid Caliphate began to fragment in the mid 9th century, its administrative machinery was copied by the emergent successor dynasties, with the already extant local ''dīwān'' branches likely providing the base on which the new administrations were formed.Saffarids, Ziyarid, Sajids, Buyids and Samanids

The administrative machinery of the Tahirid dynasty, Tahirid governors of Khurasan is almost unknown, except that their treasury was located in their capital of Nishapur. Ya'qub al-Saffar (r. 867–879), the founder of the Saffarid dynasty who supplanted the Tahirids, is known to have had a bureau of the army (''dīwān al-ʿarḍ'') for keeping the lists and supervising the payment of the troops, at his capital Zarang. Under his successor Amr ibn al-Layth (r. 879–901) there were two further treasuries, the ''māl-e khāṣṣa'', and an unnamed bureau under the chief secretary corresponding to a chancery (''dīwān al-rasāʾil'' or ''dīwān al-inshāʾ''). The Buyids, who took over Baghdad and the remains of the Abbasid Caliphate in 946, drew partly on the established Abbasid practice, but was adapted to suit the nature of the rather decentralized Buyid "confederation" of autonomous emirates. The Buyid bureaucracy was headed by three great departments: the ''dīwān al-wazīr'', charged with finances, the ''dīwān al-rasāʾil'' as the state chancery, and the ''dīwān al-jaysh'' for the army. The Buyid regime was a military regime, its ruling caste composed of Turkic peoples, Turkish and Daylamites, Daylamite troops. As a result, the army department was of particular importance, and its head, the ''ʿariḍ al-jaysh'', is frequently mentioned in the sources of the period. Indeed, at the turn of the 11th century, there were two ''ʿariḍs'', one for the Turks and one for the Daylamites, hence the department was often called "department of the two armies" (''dīwān al-jayshayn''). A number of junior departments, like the ''dīwān al-zimām'', the ''dīwān al-ḍiyāʿ'', or the ''dīwān al-barīd'' were directly inherited from the Abbasid government. Under Adud al-Dawla (r. 978–983), however, the ''dīwān al-sawād'', which oversaw the rich lands of lower Iraq, was moved from Baghdad to Shiraz. In addition, a ''dīwān al-khilāfa'' was established to oversee the affairs of the Abbasid caliphs, who continued to reside in Baghdad as puppets of the Buyid emirs.Seljuks

The Great Seljuks tended to cherish their nomadic origins, with their sultans leading a wikt:peripatetic, peripatetic court to their various capitals. Coupled with their frequent absence on campaign, the vizier assumed an even greater prominence, concentrating the direction of civil, military and religious affairs in his own bureau, the "supreme dīwān" (''dīwān al-aʿlā''). The ''dīwān al-aʿlā'' was further subdivided into a chancery (''dīwān al-inshāʾ wa’l-ṭughrā'', also called ''dīwān al-rasāʾil'') under the ''ṭughrāʾī'' or ''munshī al-mamālik'', an accounting department (''dīwān al-zimām wa’l-istīfāʾ'') under the ''mustawfī al-mamālik'', a fiscal oversight office (''dīwān al-ishrāf'' or ''dīwān al-muʿāmalāt'') under the ''mushrif al-mamālik'', and the army department (''dīwān al-ʿarḍ'' or ''dīwān al-jaysh'') under the ''ʿariḍ'' (further divided into the recruitment and supply bureau, ''dīwān al-rawātib'', and the salary and land grants bureau, ''dīwān al-iqṭāʾ''). A number of lesser departments is also attested, although they may not have existed at the same time: the office charged with the redress of grievances (''dīwān al-maẓālim''), the state treasury (''bayt al-māl'') and the sultan's private treasury (''bayt al-māl al-khaṣṣ''), confiscations (''dīwān al-muṣādara''), the land tax office (''dīwān al-kharāj'') and the department of religious endowments or ''waqfs'' (''dīwān al-awqāf''). A postal department (''dīwān al-barīd'') also existed but fell into disuse. The system was apparently partly copied in provincial centres as well.Ottoman Tripolitania

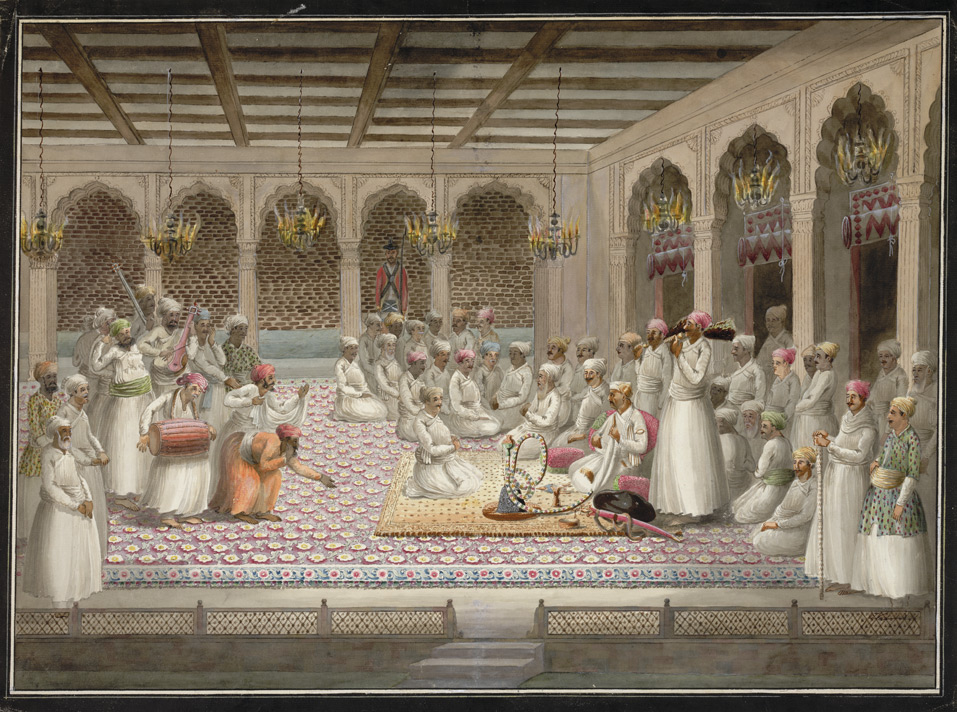

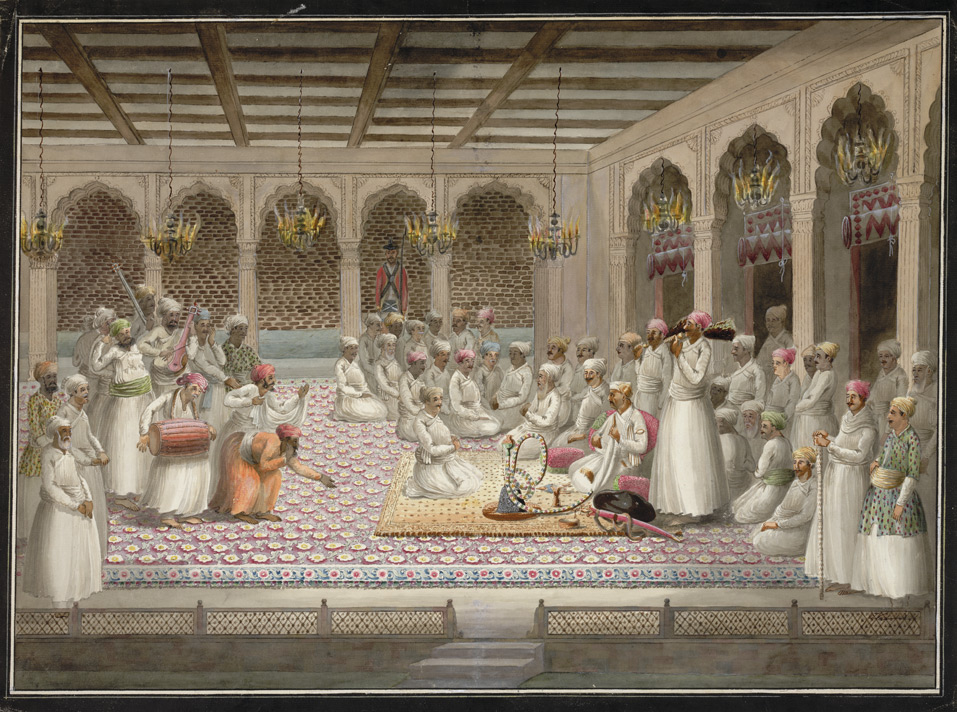

Following the Ottoman conquest of North Africa, the Greater Maghreb, Maghreb was divided into three provinces, Ottoman Algeria, Algiers, Ottoman Tunisia, Tunis, and Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli. After 1565, administrative authority in Tripoli was vested in a Pasha directly appointed by the Sultan in Constantinople. The sultan provided the pasha with a corps of Janissaries, which was in turn divided into a number of companies under the command of a junior officer or ''Bey''. The Janissaries quickly became the dominant force in Ottoman Libya. As a self-governing military guild answerable only to their own laws and protected by a ''Divan'' (in this context, a council of senior officers who advised the Pasha), the Janissaries soon reduced the Pasha to a largely ceremonial role.Government councils

The ''Divan-ı Hümayun'' or Sublime Porte was for many years the council of ministers of the Ottoman Empire. It consisted of the Grand Vizier, who presided, and the other viziers, the ''kadi'askers'', the ''nisanci'', and the ''defterdars''. The Assemblies of the Danubian Principalities under Ottoman rule were also called "divan" ("Divanuri" in Romanian) (see Akkerman Convention, ad hoc Divan). In Javanese language, Javanese and related languages, the cognate Dewan is the standard word for chamber, as in the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat or Chamber of People's Representatives..Ministerial departments

In the sultanate of Morocco, several portfolio Ministries had a title based on Diwan: *''Diwan al-Alaf'': Ministry of War. *''Diwan al-Bahr'': 'Ministry of the Sea', i.e. (overseas=) Foreign Ministry. *''Diwan al-Shikayat'' (or ''- Chikayat''): Ministry of Complaints (Ombudsman).References

Sources

* * * * * * * *{{The Arab Kingdom and its Fall Government of the Umayyad Caliphate Government of the Abbasid Caliphate Government of the Ottoman Empire Persian words and phrases Royal and noble courts