Boethius father.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (;

Boethius was born in Rome to a

Boethius was born in Rome to a

Taking inspiration from Plato's ''Republic'', Boethius left his scholarly pursuits to enter the service of

Taking inspiration from Plato's ''Republic'', Boethius left his scholarly pursuits to enter the service of

Cyprianus then also accused Boethius of the same crime and produced three men who claimed they had witnessed the crime. Boethius and Basilius were arrested. First the pair were detained in the baptistery of a church, then Boethius was exiled to the ''Ager Calventianus'', a distant country estate, where he was put to death. Not long afterwards Theodoric had Boethius' father-in-law Symmachus put to death, according to

Cyprianus then also accused Boethius of the same crime and produced three men who claimed they had witnessed the crime. Boethius and Basilius were arrested. First the pair were detained in the baptistery of a church, then Boethius was exiled to the ''Ager Calventianus'', a distant country estate, where he was put to death. Not long afterwards Theodoric had Boethius' father-in-law Symmachus put to death, according to

Boethius chose to pass on the great Greco-Roman culture to future generations by writing manuals on music, astronomy, geometry and arithmetic.

Several of Boethius' writings, which were hugely influential during the Middle Ages, drew on the thinking of Porphyry and Iamblichus. Boethius wrote a commentary on the ''

Boethius chose to pass on the great Greco-Roman culture to future generations by writing manuals on music, astronomy, geometry and arithmetic.

Several of Boethius' writings, which were hugely influential during the Middle Ages, drew on the thinking of Porphyry and Iamblichus. Boethius wrote a commentary on the ''

In ''De musica'' I.2, Boethius describes 'musica instrumentis' as music produced by something under tension (e.g., strings), by wind (e.g., aulos), by water, or by percussion (e.g., cymbals). Boethius himself doesn't use the term 'instrumentalis', which was used by Adalbold II of Utrecht (9751026) in his ''Epistola cum tractatu''. The term is much more common in the 13th century and later. It is also in these later texts that ''musica instrumentalis'' is firmly associated with audible music in general, including vocal music. Scholars have traditionally assumed that Boethius also made this connection, possibly under the header of wind instruments ("administratur ... aut spiritu ut tibiis"), but Boethius himself never writes about "instrumentalis" as separate from "instrumentis" explicitly in his very brief description.

In one of his works within ''De institutione musica'', Boethius said that "music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired."

During the Middle Ages, Boethius was connected to several texts that were used to teach liberal arts. Although he did not address the subject of trivium, he did write many treatises explaining the principles of rhetoric, grammar, and logic. During the Middle Ages, his works of these disciplines were commonly used when studying the three elementary arts. The historian R. W. Southern called Boethius "the schoolmaster of medieval Europe."

An 1872 German translation of "De Musica" was the magnum opus of

In ''De musica'' I.2, Boethius describes 'musica instrumentis' as music produced by something under tension (e.g., strings), by wind (e.g., aulos), by water, or by percussion (e.g., cymbals). Boethius himself doesn't use the term 'instrumentalis', which was used by Adalbold II of Utrecht (9751026) in his ''Epistola cum tractatu''. The term is much more common in the 13th century and later. It is also in these later texts that ''musica instrumentalis'' is firmly associated with audible music in general, including vocal music. Scholars have traditionally assumed that Boethius also made this connection, possibly under the header of wind instruments ("administratur ... aut spiritu ut tibiis"), but Boethius himself never writes about "instrumentalis" as separate from "instrumentis" explicitly in his very brief description.

In one of his works within ''De institutione musica'', Boethius said that "music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired."

During the Middle Ages, Boethius was connected to several texts that were used to teach liberal arts. Although he did not address the subject of trivium, he did write many treatises explaining the principles of rhetoric, grammar, and logic. During the Middle Ages, his works of these disciplines were commonly used when studying the three elementary arts. The historian R. W. Southern called Boethius "the schoolmaster of medieval Europe."

An 1872 German translation of "De Musica" was the magnum opus of

Dates of composition:

; Mathematical works

* ''De arithmetica'' (On Arithmetic, c. 500) adapted translation of the ''Introductionis Arithmeticae'' by

Dates of composition:

; Mathematical works

* ''De arithmetica'' (On Arithmetic, c. 500) adapted translation of the ''Introductionis Arithmeticae'' by

In

In

''De Trinitate'' (On the Holy Trinity)

– Boethius, Erik Kenyon (trans.) *

Christian Classics Ethereal Library

A 10th-century manuscript of ''Institutio Arithmetica'' is available online from Lund University, Sweden

The Geoffrey Freudlin 1885 edition of the Arithmetica, from the Cornell Library Historical Mathematics Monographs

Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Codices Boethiani: A Conspectus of Manuscripts of the Work of Boethius

Works by Boethius at Perseus Digital Library

* ttp://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0028/html/ms_484_015.html MS 484/15 Commentum super libro Porphyrii Isagoge; De decim predicamentis at OPenn

Blessed Severinus Boethius

at Patron Saints Index * Blackwood, Stephen.br>''The Meters of Boethius: Rhythmic Therapy in the Consolation of Philosophy.''

* * * Phillips, Philip Edward

Boethius

at ''The Online Library of Liberty''

–

The Philosophical Works of Boethius. Editions and Translations

{{Authority control 477 births 524 deaths 5th-century Italo-Roman people 6th-century Christian saints 6th-century Christian theologians 6th-century Italo-Roman people 6th-century Italian writers 6th-century Latin writers 6th-century mathematicians 6th-century philosophers 6th-century Roman consuls Ancient Roman rhetoricians Anicii Augustinian philosophers Burials at San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro Deaths by blade weapons Executed ancient Roman people Executed philosophers Executed writers Greek–Latin translators Imperial Roman consuls Last of the Romans Latin commentators on Aristotle Magistri officiorum Manlii Music theorists People of the Ostrogothic Kingdom Philosophers of Roman Italy Catholic philosophers Neoplatonists Roman-era philosophers Italian logicians

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

, ''magister officiorum

The ''magister officiorum'' (Latin literally for "Master of Offices", in gr, μάγιστρος τῶν ὀφφικίων, magistros tōn offikiōn) was one of the most senior administrative officials in the Later Roman Empire and the early cent ...

'', historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

. He was a central figure in the translation of the Greek classics into Latin, a precursor to the Scholastic movement, and, along with Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

, one of the two leading Christian scholars of the 6th century. The local cult of Boethius in the Diocese of Pavia

The Diocese of Pavia ( la, Dioecesis Papiensis) is a see of the Catholic Church in Italy. It has been a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Milan only since 1817.Sacred Congregation of Rites

The Sacred Congregation of Rites was a congregation of the Roman Curia, erected on 22 January 1588 by Pope Sixtus V by '' Immensa Aeterni Dei''; it had its functions reassigned by Pope Paul VI on 8 May 1969.

The Congregation was charged with the ...

in 1883, confirming the diocese's custom of honouring him on the 23 October.

Boethius was born in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

a few years after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

. A member of the Anicii

The gens Anicia (or the Anicii) was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, mentioned first towards the end of the fourth century BC. The first of the Anicii to achieve prominence under the Republic was Lucius Anicius Gallus, who conducted the war a ...

family, he was orphaned following the family's sudden decline and was raised by Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus

Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus (died 526) was a 6th-century Roman aristocrat, an historian and a supporter of Nicene Christianity. He was a patron of secular learning, and became the consul for the year 485. He supported Pope Symmachus in the ...

, a later consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

. After mastering both Latin and Greek in his youth, Boethius rose to prominence as a statesman during the Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great killed and replaced Odoacer, ...

: becoming a senator by age 25, a consul by age 33, and later chosen as a personal advisor to Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy ...

.

In seeking to reconcile the teachings of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

with Christian theology, Boethius sought to translate the entirety of the Greek classics for Western scholars. He published numerous transcriptions and commentaries of the works of Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

, Porphyry, and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, among others, and wrote extensively on matters concerning music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

, mathematics, and theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

. Though his translations were unfinished following an untimely death, it is largely due to them that the works of Aristotle survived into the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

.

Despite his successes as a senior official, Boethius became deeply unpopular among other members of the Ostrogothic court for denouncing the extensive corruption prevalent among other members of government. After publicly defending fellow-consul Caecina Albinus from charges of conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agre ...

, he was imprisoned by Theodoric around the year 523. While jailed and suffering from depression, Boethius wrote ''The Consolation of Philosophy

''On the Consolation of Philosophy'' ('' la, De consolatione philosophiae'')'','' often titled as ''The Consolation of Philosophy'' or simply the ''Consolation,'' is a philosophical work by the Roman statesman Boethius. Written in 523 while he ...

''—a philosophical treatise on fortune, death, and other issues—which became one of the most influential and widely reproduced works of the Early Middle Ages. He was tortured

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts carr ...

and executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in 524, becoming a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

in the Christian faith by tradition.

Early life and education

Boethius was born in Rome to a

Boethius was born in Rome to a patrician

Patrician may refer to:

* Patrician (ancient Rome), the original aristocratic families of ancient Rome, and a synonym for "aristocratic" in modern English usage

* Patrician (post-Roman Europe), the governing elites of cities in parts of medieval ...

family around 480, but the exact date of his birth is unknown. His birth family, the Anicii

The gens Anicia (or the Anicii) was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, mentioned first towards the end of the fourth century BC. The first of the Anicii to achieve prominence under the Republic was Lucius Anicius Gallus, who conducted the war a ...

, was a notably wealthy and influential ''gens'' that included emperors Petronius Maximus

Petronius Maximus ( 39731 May 455) was Roman emperor of the West for two and a half months in 455. A wealthy senator and a prominent aristocrat, he was instrumental in the murders of the Western Roman ''magister militum'', Aëtius, and the W ...

and Olybrius

Anicius Olybrius (died 2 November 472) was Roman emperor from July 472 until his death later that same year; his rule as ''Augustus'' in the western Roman Empire was not recognised as legitimate by the ruling ''Augustus'' in the eastern Roman ...

, in addition to many consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

. However, in the years prior to Boethius' birth, the family had lost much of its influence. The grandfather of Boethius, a senator by the same name, was appointed as praetorian prefect of Italy but died in 454 during the palace plot against Flavius Aetius

Aetius (also spelled Aëtius; ; 390 – 454) was a Roman general and statesman of the closing period of the Western Roman Empire. He was a military commander and the most influential man in the Empire for two decades (433454). He managed pol ...

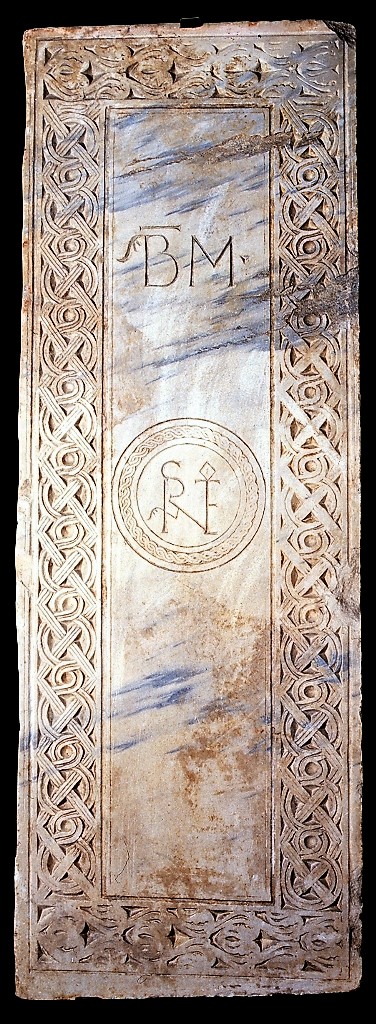

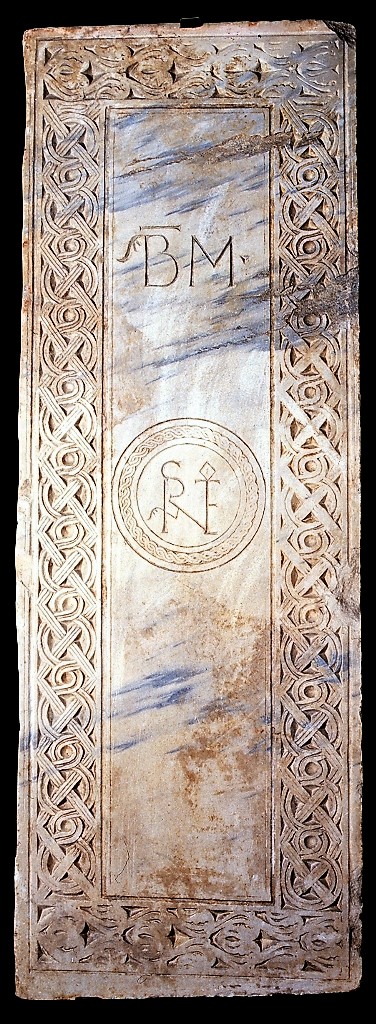

. Boethius' father, Manlius Boethius, who was appointed consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

in 487, died while Boethius was still young. Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus

Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus (died 526) was a 6th-century Roman aristocrat, an historian and a supporter of Nicene Christianity. He was a patron of secular learning, and became the consul for the year 485. He supported Pope Symmachus in the ...

, another patrician, adopted and raised him instead, introducing to him philosophy and literature. As a sign of their good relationship, Boethius would later marry his foster-father's daughter, Rusticiana, with whom he would have two children also named Symmachus and Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

.

Having been adopted into the wealthy Symmachi family, Boethius had access to tutors that would have educated him during his youth. Though Symmachus had some fluency in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Boethius achieved a mastery of the language—an increasingly rare skill in the Western regions of the Empire—and dedicated his early career to translating the entire works of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, with some of the translations that he produced being the only surviving transcriptions of Greek texts into the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. The unusual fluency of Boethius in the Greek language has led some scholars to believe that he was educated in the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

; a traditional view, first proposed by Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

, is that Boethius studied in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

for eighteen years based on the letters of Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

, though this was likely to have been a misreading by past historians.

Historian Pierre Courcelle

Pierre Courcelle (16 March 1912 – 25 July 1980) was a French historian who was a specialist of ancient philosophy and of Latin Patristics, especially of St Augustine. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philos ...

has argued that Boethius studied at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

with the Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

philosopher Ammonius Hermiae

Ammonius Hermiae (; grc-gre, Ἀμμώνιος ὁ Ἑρμείου, Ammōnios ho Hermeiou, Ammonius, son of Hermias; – between 517 and 526) was a Greek philosopher from Alexandria in the eastern Roman empire during Late Antiquity. A Neoplatonis ...

. However, Historian John Moorhead observes that the evidence supporting Boethius having studied in Alexandria is "not as strong as it may appear," adding that he may have been able to acquire his formidable learning without travelling. Whatever the case, Boethius' fluency in Greek proved useful throughout his life in translating the classic works of Greek thinkers, though his interests spanned across a variety of fields including music, mathematics, astrology, and theology.

Rise to power

Taking inspiration from Plato's ''Republic'', Boethius left his scholarly pursuits to enter the service of

Taking inspiration from Plato's ''Republic'', Boethius left his scholarly pursuits to enter the service of Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy ...

. The two had first met in the year 500 when Theodoric traveled to Rome to stay for six months. Though no record survives detailing the early relationship between Theodoric and Boethius, it is clear that the Ostrogothic king viewed him favorably: in the next few years, Boethius rapidly ascended through the ranks of government, becoming a senator by age 25 and a consul by the year 510. His earliest documented acts on behalf of the Ostrogothic ruler were to investigate allegations that the paymaster of Theodoric's bodyguards had debased the coins of their pay; to produce a waterclock for Theodoric to gift to king Gundobad of the Burgundians; and to recruit a lyre-player to perform for Clovis, King of the Franks.

Boethius writes in the ''Consolation

Consolation, consolement, and solace are terms referring to psychological comfort given to someone who has suffered severe, upsetting loss, such as the death of a loved one. It is typically provided by expressing shared regret for that loss an ...

'' that, despite his own successes, he believed that his greatest achievement came when both his sons were selected by Theodoric to be consuls in 522, with each representing the whole of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. The appointment of his sons was an exceptional honor, not only since it made conspicuous Theodoric's favor for Boethius, but also because the Byzantine emperor Justin I

Justin I ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, ''Ioustînos''; 450 – 1 August 527) was the Eastern Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial ...

had forfeited his own nomination as a sign of goodwill, thus also endorsing Boethius' sons. In the same year as the appointment of his sons, Boethius was elevated to the position of ''magister officiorum

The ''magister officiorum'' (Latin literally for "Master of Offices", in gr, μάγιστρος τῶν ὀφφικίων, magistros tōn offikiōn) was one of the most senior administrative officials in the Later Roman Empire and the early cent ...

'', becoming the head of all government and palace affairs. Recalling the event, he wrote that he was sitting "between the two consuls as if it were a military triumph, etting my

Etting (; ; Lorraine Franconian: ''Ettinge'') is a commune in the Moselle department of the Grand Est administrative region in north-eastern France.

The village belongs to the Pays de Bitche.

See also

* Communes of the Moselle department

The ...

largesse fulfill the wildest expectations of the people packed in their seats around e"

Boethius' struggles came within a year of his appointment as ''magister officiorum'': in seeking to mend the rampant corruption present in the Roman Court, he writes of having to thwart the conspiracies of Triguilla, the steward of the royal house; of confronting the Gothic minister, Cunigast, who went to "devour the substance of the poor"; and of having to use the authority of the king to stop a shipment of food from Campania which, if carried, would have exacerbated an ongoing famine in the region. These actions made Boethius an increasingly unpopular figure among court officials, though he remained in Theodoric's favor.

Fall and death

In 520, Boethius was working to revitalize the relationship between theRoman See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rom ...

and the Constantinopolitan See—though the two were then still a part of the same Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

, disagreements had begun to emerge between them. This may have set in place a course of events that would lead to loss of royal favour. Five hundred years later, this continuing disagreement led to the East–West Schism in 1054, in which communion between the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

was broken.

In 523, Boethius fell from power. After a period of imprisonment in Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the cap ...

for what was deemed a treasonable offence, he was executed in 524. The primary sources are in general agreement over the facts of what happened. At a meeting of the Royal Council in Verona, the '' referendarius'' Cyprianus accused the ex-consul Caecina Decius Faustus Albinus of treasonous correspondence with Justin I

Justin I ( la, Iustinus; grc-gre, Ἰουστῖνος, ''Ioustînos''; 450 – 1 August 527) was the Eastern Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial ...

. Boethius leapt to his defense, crying, "The charge of Cyprianus is false, but if Albinus did that, so also have I and the whole senate with one accord done it; it is false, my Lord King." Cyprianus then also accused Boethius of the same crime and produced three men who claimed they had witnessed the crime. Boethius and Basilius were arrested. First the pair were detained in the baptistery of a church, then Boethius was exiled to the ''Ager Calventianus'', a distant country estate, where he was put to death. Not long afterwards Theodoric had Boethius' father-in-law Symmachus put to death, according to

Cyprianus then also accused Boethius of the same crime and produced three men who claimed they had witnessed the crime. Boethius and Basilius were arrested. First the pair were detained in the baptistery of a church, then Boethius was exiled to the ''Ager Calventianus'', a distant country estate, where he was put to death. Not long afterwards Theodoric had Boethius' father-in-law Symmachus put to death, according to Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

, on the grounds that he and Boethius together were planning a revolution, and confiscated their property. "The basic facts in the case are not in dispute," writes Jeffrey Richards. "What is disputed about this sequence of events is the interpretation that should be put on them." Boethius claims his crime was seeking "the safety of the Senate". He describes the three witnesses against him as dishonorable: Basilius had been dismissed from Royal service for his debts, while Venantius Opilio

Venantius Opilio (''floruit'' 500–534) was a Roman politician during the reign of Theodoric the Great. Although he was Roman consul, consul as the junior colleague of emperor Justin I in 524, Opilio is best known as one of the three men who Boet ...

and Gaudentius had been exiled for fraud. However, other sources depict these men in a far more positive light. For example, Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

describes Cyprianus and Opilio as "utterly scrupulous, just and loyal" and mentions they are brothers and grandsons of the consul Opilio.

Theodoric was feeling threatened by international events. The Acacian schism

The Acacian schism, between the Eastern and Western Christian Churches, lasted 35 years, from 484 to 519 AD. It resulted from a drift in the leaders of Eastern Christianity toward Miaphysitism and Emperor Zeno's unsuccessful attempt to reconcile ...

had been resolved, and the Nicene Christian aristocrats of his kingdom were seeking to renew their ties with Constantinople. The Catholic Hilderic

Hilderic (460s – 533) was the penultimate king of the Vandals and Alans in North Africa in Late Antiquity (523–530). Although dead by the time the Vandal Kingdom was overthrown in 534, he nevertheless played a key role in that event.

Biog ...

had become king of the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area betw ...

and had put Theodoric's sister Amalafrida Amalafrida (fl. 523), was the daughter of Theodemir, king of the Ostrogoths, and his wife Erelieva. She was the sister of Theodoric the Great, and mother of Theodahad, both of whom also were kings of the Ostrogoths.

In 500, Theodoric, ruler over ...

to death, and Arians

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

in the East were being persecuted. Then there was the matter that with his previous ties to Theodahad

Theodahad, also known as Thiudahad ( la, Flavius Theodahatus , Theodahadus, Theodatus; 480 – December 536) was king of the Ostrogoths from 534 to 536.

Early life

Born at in Tauresium, Theodahad was a nephew of Theodoric the Great throu ...

, Boethius apparently found himself on the wrong side in the succession dispute following the untimely death of Eutharic

Eutharic Cilliga (Latin: ''Flavius Eutharicus Cillica'') was an Ostrogothic prince from Iberia (modern-day Spain) who, during the early 6th century, served as Roman Consul and "son in weapons" (''filius per arma'') alongside the Byzantine emperor J ...

, Theodoric's announced heir.

The method of Boethius' execution varies in the sources. He may have been behead

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

ed, clubbed to death, or hanged. It is likely that he was tortured with a rope that was constricted around his head, bludgeoned until his eyes bulged out; then his skull was cracked. Following an agonizing death, his remains were entombed in the church of San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro

San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro ( Italian for "Saint Peter in Golden Sky") is a Catholic basilica (and a former cathedral) of the Augustinians in Pavia, Italy, in the Lombardy region. Its name refers to the mosaics of gold leaf behind glass tesserae tha ...

in Pavia, also the resting place of Augustine of Hippo. His wealth was also confiscated, and his wife, Rusticiana, reduced to poverty.

Past historians have had a hard time accepting a sincere Christian who was also a serious Hellenist. These worries have largely stemmed by the lack of any mention of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

in Boethius' ''Consolation'', nor of any other Christian figure. Arnaldo Momigliano

Arnaldo Dante Momigliano (5 September 1908 – 1 September 1987) was an Italian historian of classical antiquity, known for his work in historiography, and characterised by Donald Kagan as "the world's leading student of the writing of history i ...

argues that "Boethius turned to paganism. His Christianity collapsed—it collapsed so thoroughly that perhaps he did not even notice its disappearance." However, the majority of scholarship has taken a different view, with Arthur Herman writing that Boethius was "unshakably Orthodox Catholic," and Thomas Hodgkin

Thomas Hodgkin RMS (17 August 1798 – 5 April 1866) was a British physician, considered one of the most prominent pathologists of his time and a pioneer in preventive medicine. He is now best known for the first account of Hodgkin's disease, ...

having asserted that uncovered manuscripts "prove beyond a doubt that Boethius was a Christian." Furthermore, the community that he was a part of valued equally both classical and Christian culture.

Major works

''De consolatione philosophiae''

Boethius's best known work is the ''Consolation of Philosophy

''On the Consolation of Philosophy'' ('' la, De consolatione philosophiae'')'','' often titled as ''The Consolation of Philosophy'' or simply the ''Consolation,'' is a philosophical work by the Roman statesman Boethius. Written in 523 while he ...

'' (''De consolatione philosophiae''), which he wrote at the very end of his career, awaiting his execution in prison. This work represented an imaginary dialogue between himself and philosophy, with philosophy personified as a woman, arguing that despite the apparent inequality of the world, there is, in Platonic

Plato's influence on Western culture was so profound that several different concepts are linked by being called Platonic or Platonist, for accepting some assumptions of Platonism, but which do not imply acceptance of that philosophy as a whole. It ...

fashion, a higher power and everything else is secondary to that divine Providence.

Several manuscripts survived and these were widely edited, translated and printed throughout the late 15th century and later in Europe. Beyond ''Consolation of Philosophy'', his lifelong project was a deliberate attempt to preserve ancient classical knowledge, particularly philosophy. Boethius intended to translate all the works of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

and Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

from the original Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

.

''De topicis differentiis''

His completed translations of Aristotle's works onlogic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premise ...

were the only significant portions of Aristotle available in Latin Christendom from the sixth century until the rediscovery of Aristotle in the 12th century. However, some of his translations (such as his treatment of the topoi

In mathematics, a topos (, ; plural topoi or , or toposes) is a category that behaves like the category of sheaves of sets on a topological space (or more generally: on a site). Topoi behave much like the category of sets and possess a noti ...

in ''The Topics'') were mixed with his own commentary, which reflected both Aristotelian and Platonic concepts.

Unfortunately, the commentaries themselves have been lost. In addition to his commentary on the Topics, Boethius composed two treatises on Topical argumentation, ''In Ciceronis Topica'' and ''De topicis differentiis''. The first work has six books, and is largely a response to Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

's ''Topica''. The first book of ''In Ciceronis Topica'' begins with a dedication to Patricius. It includes distinctions and assertions important to Boethius's overall philosophy, such as his view of the role of philosophy as "establish ngour judgment concerning the governing of life", and definitions of logic from Plato, Aristotle and Cicero. He breaks logic into three parts: that which defines, that which divides, and that which deduces.

He asserts that there are three types of arguments: those of necessity, of ready believability, and sophistry. He follows Aristotle in defining one sort of Topic as the maximal proposition, a proposition which is somehow shown to be universal or readily believable. The other sort of Topic, the differentiae, are "Topics that contain and include the maximal propositions"; means of categorizing the Topics which Boethius credits to Cicero.

BookII covers two kinds of topics: those from related things and those from extrinsic topics. BookIII discusses the relationship among things studied through Topics, Topics themselves, and the nature of definition. BookIV analyzes partition, designation and relationships between things (such as pairing, numbering, genus, and species, etc.). After a review of his terms, Boethius spends BookV discussing Stoic logic

Stoic logic is the system of propositional logic developed by the Stoic philosophers in ancient Greece.

It was one of the two great systems of logic in the classical world. It was largely built and shaped by Chrysippus, the third head of the Stoi ...

and Aristotelian causation. BookVI relates the nature of the Topic to causes.

''In Topicis Differentiis'' has four books; BookI discusses the nature of rhetorical and dialectical Topics together, Boethius's overall purpose being "to show what the Topics are, what their differentiae are, and which are suited for what syllogisms." He distinguishes between argument (that which constitutes belief) and argumentation (that which demonstrates belief). Propositions are divided into three parts: those that are universal, those that are particular, and those that are somewhere in between. These distinctions, and others, are applicable to both types of Topical argument, rhetorical and dialectical. BooksII and III are primarily focused on Topics of dialectic (syllogisms), while BookIV concentrates on the unit of the rhetorical Topic, the enthymeme. Topical argumentation is at the core of Boethius's conception of dialectic, which "have categorical rather than conditional conclusions, and he conceives of the discovery of an argument as the discovery of a middle term capable of linking the two terms of the desired conclusion."

Not only are these texts of paramount importance to the study of Boethius, they are also crucial to the history of topical lore. It is largely due to Boethius that the Topics of Aristotle and Cicero were revived, and the Boethian tradition of topical argumentation spans its influence throughout the Middle Ages and into the early Renaissance: "In the works of Ockham, Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the w ...

, Albert of Saxony

en, Frederick Augustus Albert Anthony Ferdinand Joseph Charles Maria Baptist Nepomuk William Xavier George Fidelis

, image = Albert of Saxony by Nicola Perscheid c1900.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = Photograph by Nicola Persch ...

, and the Pseudo-Scotus, for instance, many of the rules of consequence bear a strong resemblance to or are simply identical with certain Boethian Topics ... Boethius's influence, direct and indirect, on this tradition is enormous."

It was also in ''De Topicis Differentiis'' that Boethius made a unique contribution to the discourse on dialectic and rhetoric. Topical argumentation for Boethius is dependent upon a new category for the topics discussed by Aristotle and Cicero, and " like Aristotle, Boethius recognizes two different types of Topics. First, he says, a Topic is a maximal proposition (''maxima propositio''), or principle; but there is a second kind of Topic, which he calls the ''differentia'' of a maximal proposition. Maximal propositions are "propositions hat are

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

known per se, and no proof can be found for these."

This is the basis for the idea that demonstration (or the construction of arguments) is dependent ultimately upon ideas or proofs that are known so well and are so fundamental to human understanding of logic that no other proofs come before it. They must hold true in and of themselves. According to Stump, "the role of maximal propositions in argumentation is to ensure the truth of a conclusion by ensuring the truth of its premises either directly or indirectly."These propositions would be used in constructing arguments through the ''Differentia'', which is the second part of Boethius' theory. This is "the genus of the intermediate in the argument." So maximal propositions allow room for an argument to be founded in some sense of logic while ''differentia'' are critical for the demonstration and construction of arguments.

Boethius' definition of "differentiae" is that they are "the Topics of arguments ... The Topics which are the Differentiae of aximalpropositions are more universal than those propositions, just as rationality is more universal than man." This is the second part of Boethius' unique contribution to the field of rhetoric. ''Differentia'' operate under maximal propositions to "be of use in finding maximal propositions as well as intermediate terms," or the premises that follow maximal propositions.

Though Boethius is drawing from Aristotle's Topics, ''Differentiae'' are not the same as Topics in some ways. Boethius arranges ''differentiae'' through statements, instead of generalized groups as Aristotle does. Stump articulates the difference. They are "expressed as words or phrases whose expansion into appropriate propositions is neither intended nor readily conceivable", unlike Aristotle's clearly defined four groups of Topics. Aristotle had hundreds of topics organized into those four groups, whereas Boethius has twenty-eight "Topics" that are "highly ordered among themselves." This distinction is necessary to understand Boethius as separate from past rhetorical theories.

Maximal propositions and ''Differentiae'' belong not only to rhetoric, but also to dialectic. Boethius defines dialectic through an analysis of "thesis" and hypothetical propositions. He claims that " ere are two kinds of questions. One is that called, 'thesis' by the reek

Reek may refer to:

Places

* Reek, Netherlands, a village in the Dutch province of North Brabant

* Croagh Patrick, a mountain in the west of Ireland nicknamed "The Reek"

People

* Nikolai Reek (1890-1942), Estonian military commander

* Salme Reek ...

dialecticians. This is the kind of question which asks about and discusses things stripped of relation to other circumstances; it is the sort of question dialecticians most frequently dispute about—for example, 'Is pleasure the greatest good?' r'Should one marry?'." Dialectic has "dialectical topics" as well as "dialectical-rhetorical topics", all of which are still discussed in ''De Topicis Differentiis''. Dialectic, especially in BookI, comprises a major component of Boethius' discussion on Topics.

Boethius planned to completely translate Plato's ''Dialogues'', but there is no known surviving translation, if it was actually ever begun.

''De arithmetica''

Boethius chose to pass on the great Greco-Roman culture to future generations by writing manuals on music, astronomy, geometry and arithmetic.

Several of Boethius' writings, which were hugely influential during the Middle Ages, drew on the thinking of Porphyry and Iamblichus. Boethius wrote a commentary on the ''

Boethius chose to pass on the great Greco-Roman culture to future generations by writing manuals on music, astronomy, geometry and arithmetic.

Several of Boethius' writings, which were hugely influential during the Middle Ages, drew on the thinking of Porphyry and Iamblichus. Boethius wrote a commentary on the ''Isagoge

The ''Isagoge'' ( el, Εἰσαγωγή, ''Eisagōgḗ''; ) or "Introduction" to Aristotle's "Categories", written by Porphyry in Greek and translated into Latin by Boethius, was the standard textbook on logic for at least a millennium after his ...

'' by Porphyry, which highlighted the existence of the problem of universals

The problem of universals is an ancient question from metaphysics that has inspired a range of philosophical topics and disputes: Should the properties an object has in common with other objects, such as color and shape, be considered to exist be ...

: whether these concepts are subsistent entities which would exist whether anyone thought of them, or whether they only exist as ideas. This topic concerning the ontological

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exi ...

nature of universal ideas was one of the most vocal controversies in medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, ...

.

Besides these advanced philosophical works, Boethius is also reported to have translated important Greek texts on the topics of the quadrivium

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in the ...

His loose translation of Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

's treatise on arithmetic (''De institutione arithmetica libri duo'') and his textbook on music (''De institutione musica libri quinque'', unfinished) contributed to medieval education. ''De arithmetica'' begins with modular arithmetic, such as even and odd, evenly even, evenly odd, and oddly even. He then turns to unpredicted complexity by categorizing numbers and parts of numbers. His translations of Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

on geometry and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

on astronomy, if they were completed, no longer survive. Boethius made Latin translations of Aristotle's ''De interpretatione'' and ''Categories'' with commentaries. In his article ''The Ancient Classics in the Mediaeval Libraries'', James Stuart Beddie cites Boethius as the reason Aristotle's works were popular in the Middle Ages, as Boethius preserved many of the philosopher's works.

''De institutione musica''

Boethius' ''De institutione musica'' was one of the first musical texts to be printed in Venice between the years of 1491 and 1492. It was written toward the beginning of the sixth century and helped medieval theorists during the ninth century and onwards understandancient Greek music

Music was almost universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals, and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like reciting of epic poetry. It thus played an integral role in the lives of ancient Greek ...

. Like his Greek predecessors, Boethius believed that arithmetic and music were intertwined, and helped to mutually reinforce the understanding of each, and together exemplified the fundamental principles of order and harmony in the understanding of the universe as it was known during his time.

In ''me Musica'', Boethius introduced the threefold classification of music:

* ''Musica mundana'' – music of the spheres

The ''musica universalis'' (literally universal music), also called music of the spheres or harmony of the spheres, is a philosophical concept that regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies – the Sun, Moon, and planets – as a fo ...

/world; this "music" was not actually audible and was to be understood rather than heard

* ''Musica humana'' – harmony of human body and spiritual harmony

* ''Musica instrumentalis'' – instrumental music

In ''De musica'' I.2, Boethius describes 'musica instrumentis' as music produced by something under tension (e.g., strings), by wind (e.g., aulos), by water, or by percussion (e.g., cymbals). Boethius himself doesn't use the term 'instrumentalis', which was used by Adalbold II of Utrecht (9751026) in his ''Epistola cum tractatu''. The term is much more common in the 13th century and later. It is also in these later texts that ''musica instrumentalis'' is firmly associated with audible music in general, including vocal music. Scholars have traditionally assumed that Boethius also made this connection, possibly under the header of wind instruments ("administratur ... aut spiritu ut tibiis"), but Boethius himself never writes about "instrumentalis" as separate from "instrumentis" explicitly in his very brief description.

In one of his works within ''De institutione musica'', Boethius said that "music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired."

During the Middle Ages, Boethius was connected to several texts that were used to teach liberal arts. Although he did not address the subject of trivium, he did write many treatises explaining the principles of rhetoric, grammar, and logic. During the Middle Ages, his works of these disciplines were commonly used when studying the three elementary arts. The historian R. W. Southern called Boethius "the schoolmaster of medieval Europe."

An 1872 German translation of "De Musica" was the magnum opus of

In ''De musica'' I.2, Boethius describes 'musica instrumentis' as music produced by something under tension (e.g., strings), by wind (e.g., aulos), by water, or by percussion (e.g., cymbals). Boethius himself doesn't use the term 'instrumentalis', which was used by Adalbold II of Utrecht (9751026) in his ''Epistola cum tractatu''. The term is much more common in the 13th century and later. It is also in these later texts that ''musica instrumentalis'' is firmly associated with audible music in general, including vocal music. Scholars have traditionally assumed that Boethius also made this connection, possibly under the header of wind instruments ("administratur ... aut spiritu ut tibiis"), but Boethius himself never writes about "instrumentalis" as separate from "instrumentis" explicitly in his very brief description.

In one of his works within ''De institutione musica'', Boethius said that "music is so naturally united with us that we cannot be free from it even if we so desired."

During the Middle Ages, Boethius was connected to several texts that were used to teach liberal arts. Although he did not address the subject of trivium, he did write many treatises explaining the principles of rhetoric, grammar, and logic. During the Middle Ages, his works of these disciplines were commonly used when studying the three elementary arts. The historian R. W. Southern called Boethius "the schoolmaster of medieval Europe."

An 1872 German translation of "De Musica" was the magnum opus of Oscar Paul

Oscar Paul (8 April 183618 April 1898) was a German musicologist and a music writer, critic, and teacher.

Biography

Oscar Paul was born in Freiwaldau in Silesia (now Gozdnica in the Województwo lubuskie of the Poland). He studied at Görlitz ...

.

''Opuscula sacra''

Boethius also wrote Christian theological treatises, which supportedCatholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and condemned Arianism and other heterodox

In religion, heterodoxy (from Ancient Greek: , "other, another, different" + , "popular belief") means "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position". Under this definition, heterodoxy is similar to unorthodoxy, w ...

forms of Christianity.

Five theological works are known:

* ''De Trinitate'' – "The Trinity", where he defends the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bi ...

Trinitarian position, that God is in three persons who have no differences in nature. He argues against the Arian view of the nature of God, which put him at odds with the faith of the Arian King of Italy.

* ''Utrum Pater et filius et Spiritus Sanctus de divinitate substantialiter praedicentur'' – "Whether Father, Son and Holy Spirit are Substantially Predicated of the Divinity", a short work where he uses reason and Aristotelian epistemology to argue that the Catholic views of the nature of God are correct.

* ''Quomodo substantiae'', Boethius' claim that all substances are good.

* ''De fide catholica'' – "On the Catholic Faith"

* ''Contra Eutychen et Nestorium'' – "Against Eutyches and Nestorius," from around 513, which dates it as the earliest of his theological works. Eutyches and Nestorius were contemporaries in the early to mid-5th century who held divergent Christological theologies. Boethius argues for a middle ground in conformity with Roman Catholic faith.

His theological works played an important part during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

in philosophical thought, including the fields of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premise ...

, ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exi ...

, and metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

.

Dates of works

Dates of composition:

; Mathematical works

* ''De arithmetica'' (On Arithmetic, c. 500) adapted translation of the ''Introductionis Arithmeticae'' by

Dates of composition:

; Mathematical works

* ''De arithmetica'' (On Arithmetic, c. 500) adapted translation of the ''Introductionis Arithmeticae'' by Nicomachus of Gerasa

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

(c. 160 – c. 220).

* ''De musica'' (On Music, c. 510), based on a lost work by Nicomachus of Gerasa and on Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

's ''Harmonica''.

* Possibly a treatise on geometry, extant only in fragments.

; Logical Works

; A) Translations

* '' Porphyry's ''Isagoge

The ''Isagoge'' ( el, Εἰσαγωγή, ''Eisagōgḗ''; ) or "Introduction" to Aristotle's "Categories", written by Porphyry in Greek and translated into Latin by Boethius, was the standard textbook on logic for at least a millennium after his ...

''

* ''In Categorias Aristotelis'': Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

's ''Categories

Category, plural categories, may refer to:

Philosophy and general uses

*Categorization, categories in cognitive science, information science and generally

*Category of being

* ''Categories'' (Aristotle)

*Category (Kant)

* Categories (Peirce)

* ...

''

* ''De interpretatione vel periermenias'': Aristotle's De Interpretatione''

* ''Interpretatio priorum Analyticorum'' (two versions): Aristotle's '' Prior Analytics''

* ''Interpretatio Topicorum Aristotelis'': Aristotle's '' Topics''

* ''Interpretatio Elenchorum Sophisticorum Aristotelis'': Aristotle's ''Sophistical Refutations

''Sophistical Refutations'' ( el, Σοφιστικοὶ Ἔλεγχοι, Sophistikoi Elenchoi; la, De Sophisticis Elenchis) is a text in Aristotle's ''Organon'' in which he identified thirteen fallacies.Sometimes listed as twelve. According to A ...

''

; B) Commentaries

* ''In Isagogen Porphyrii commenta'' (two commentaries, the first based on a translation by Marius Victorinus, (c. 504–05); the second based on Boethius' own translation (507–509) ).

* ''In Categorias Aristotelis'' (c. 509–11)

* ''In librum Aristotelis de interpretatione Commentaria minora'' (not before 513)

* ''In librum Aristotelis de interpretatione Commentaria majora'' (c. 515–16)

* ''In Aristotelis Analytica Priora'' (c. 520–523)

* ''Commentaria in Topica Ciceronis'' (incomplete: the end the sixth book and the seventh are missing)

; Original Treatises

* ''De divisione'' (515–520?)

* ''De syllogismo cathegorico'' (505–506)

* ''Introductio ad syllogismos cathegoricos'' (c. 523)

* ''De hypotheticis syllogismis'' (516–522)

* ''De topicis differentiis'' (c. 522–23)

* ''Opuscula Sacra'' (Theological Treatises)

** ''De Trinitate'' (c. 520–21)

** ''Utrum Pater et Filius et Spiritus Sanctus de divinitate substantialiter praedicentur'' (Whether Father and Son and Holy Spirit are Substantially Predicated of the Divinity)

** ''Quomodo substantiae in eo quod sint bonae sint cum non sint substantialia bona'' lso known as ''De hebdomadibus''(How Substances are Good in that they Exist, when They are not Substantially Good)

** ''De fide Catholica''

** ''Contra Eutychen et Nestorium'' (Against Eutyches

Eutyches ( grc, Εὐτυχής; c. 380c. 456) or Eutyches of ConstantinopleNestorius

Nestorius (; in grc, Νεστόριος; 386 – 451) was the Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to August 431. A Christian theologian, several of his teachings in the fields of Christology and Mariology were seen as contr ...

)

* ''De consolatione Philosophiae'' (524–525).

Legacy

Edward Kennard Rand

Edward Kennard Rand FBA OCI (December 20, 1871 – October 28, 1945), known widely as E.K. Rand or to his peers as EKR, was an American classical scholar and medievalist. He served as the Pope Professor of Latin at Harvard University from 190 ...

dubbed Boethius as the "last of the Roman philosophers and the first of the scholastic theologians". Despite the use of his mathematical texts in the early universities, it is his final work, the ''Consolation of Philosophy

''On the Consolation of Philosophy'' ('' la, De consolatione philosophiae'')'','' often titled as ''The Consolation of Philosophy'' or simply the ''Consolation,'' is a philosophical work by the Roman statesman Boethius. Written in 523 while he ...

'', that assured his legacy in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

and beyond. This work is cast as a dialogue between Boethius himself, at first bitter and despairing over his imprisonment, and the spirit of philosophy, depicted as a woman of wisdom and compassion. "Alternately composed in prose and verse, the ''Consolation'' teaches acceptance of hardship in a spirit of philosophical detachment from misfortune".

Parts of the work are reminiscent of the Socratic method

The Socratic method (also known as method of Elenchus, elenctic method, or Socratic debate) is a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals, based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and to draw ou ...

of Plato's dialogues, as the spirit of philosophy questions Boethius and challenges his emotional reactions to adversity. The work was translated into Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

by King Alfred

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who ...

and later into English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

by Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

and Queen Elizabeth. Many manuscripts survive and it was extensively edited, translated and printed throughout Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

from the 14th century onwards.

"The Boethian Wheel" is a model for Boethius' belief that history is a wheel, a metaphor that Boethius uses frequently in the ''Consolation''; it remained very popular throughout the Middle Ages, and is still often seen today. As the wheel turns, those who have power and wealth will turn to dust; men may rise from poverty and hunger to greatness, while those who are great may fall with the turn of the wheel. It was represented in the Middle Ages in many relics of art depicting the rise and fall of man. Descriptions of "The Boethian Wheel" can be found in the literature of the Middle Ages from the ''Romance of the Rose'' to Chaucer.

''De topicis differentiis'' was the basis for one of the first works of logic in a western European vernacular, a selection of excerpts translated into Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

by John of Antioch in 1282.

Veneration

Boethius was regarded as a Christian martyr by those who lived in succeding centuries after his death. Currently, he is recognized as a saint and martyr for the Catholic faith. He is included within theRoman Martyrology

The ''Roman Martyrology'' ( la, Martyrologium Romanum) is the official martyrology of the Catholic Church. Its use is obligatory in matters regarding the Roman Rite liturgy, but dioceses, countries and religious institutes may add duly approved ...

, though to Watkins "his status as martyr is dubious". His cult is held in Pavia, where Boethius' status as a saint was confirmed in 1883, and in the Church of Santa Maria in Portico in Rome. His feast day is 23 October. In the current Martyrologium Romanum, his feast is still restricted to that diocese. Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the soverei ...

explained the relevance of Boethius to modern day Christians by linking his teachings to an understanding of Providence. He is also venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

In popular culture

In

In Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian people, Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', origin ...

's ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature ...

'', the spirit of Boethius is pointed out by Saint Thomas Aquinas and is mentioned further in the poem.

In the novel ''A Confederacy of Dunces

''A Confederacy of Dunces'' is a picaresque novel by American novelist John Kennedy Toole which reached publication in 1980, eleven years after Toole's death. Published through the efforts of writer Walker Percy (who also contributed a foreword) ...

'' by John Kennedy Toole

John Kennedy Toole (; December 17, 1937 – March 26, 1969) was an American novelist from New Orleans, Louisiana whose posthumously published novel, ''A Confederacy of Dunces'', won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981; he also wrote '' The N ...

, Boethius is the favorite philosopher of the main character, Ignatius J. Reilly. The "Boethian Wheel" is a theme throughout the book, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981.

C.S. Lewis

CS, C-S, C.S., Cs, cs, or cs. may refer to:

Job titles

* Chief Secretary (Hong Kong)

* Chief superintendent, a rank in the British and several other police forces

* Company secretary, a senior position in a private sector company or public se ...

references Boethius in chapter 27 of the Screwtape Letters

''The Screwtape Letters'' is a Christian apologetic novel by C. S. Lewis and dedicated to J. R. R. Tolkien. It is written in a satirical, epistolary style and while it is fictional in format, the plot and characters are used to address Chris ...

.

Boethius also appears in the 2002 film ''24 Hour Party People

''24 Hour Party People'' is a 2002 British biographical comedy-drama film about Manchester's popular music community from 1976 to 1992, and specifically about Factory Records. It was written by Frank Cottrell Boyce and directed by Michael Wint ...

'' where he is played by Christopher Eccleston.

In 1976, a lunar crater

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wor ...

was named in honor of Boethius.

The title of Alain de Botton

Alain de Botton (; born 20 December 1969) is a Swiss-born British author and philosopher. His books discuss various contemporary subjects and themes, emphasizing philosophy's relevance to everyday life. He published ''Essays in Love'' (1993) ...

's book, '' The Consolations of Philosophy'', is derived from Boethius' ''Consolation''.

A codex of Boethius' ''The Consolation of Philosophy'' is the focus of ''The Late Scholar

''The Late Scholar'' is the fourth Lord Peter Wimsey- Harriet Vane detective novel written by Jill Paton Walsh. Featuring characters created by Dorothy L. Sayers, it was written with the co-operation and approval of Sayers' estate. It was pu ...

'', a Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A dilettante who solves mysteries fo ...

novel by Jill Paton Walsh

Gillian Honorine Mary Herbert, Baroness Hemingford, (née Bliss; 29 April 1937 – 18 October 2020), known professionally as Jill Paton Walsh, was an English novelist and children's writer. She may be known best for her Booker Prize-nominated n ...

.

See also

* '' De Fide Catolica'' * '' The Consolations of Philosophy'' (by Alain de Botton) * ''The Consolation of Philosophy'' (by Boethius) *Prison literature

Prison literature is a literary genre characterized by literature that is written while the author is confined in a location against his will, such as a prison, jail or house arrest.Tony Perrottet. "Serving the Sentence", '' New York Times Book Re ...

Notes

References

Sources

;Books * * * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ; Journal articles * * * ; Weblinks * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *External links

Works

* * * *''De Trinitate'' (On the Holy Trinity)

– Boethius, Erik Kenyon (trans.) *

Christian Classics Ethereal Library

A 10th-century manuscript of ''Institutio Arithmetica'' is available online from Lund University, Sweden

The Geoffrey Freudlin 1885 edition of the Arithmetica, from the Cornell Library Historical Mathematics Monographs

Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Codices Boethiani: A Conspectus of Manuscripts of the Work of Boethius

Works by Boethius at Perseus Digital Library

* ttp://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/0028/html/ms_484_015.html MS 484/15 Commentum super libro Porphyrii Isagoge; De decim predicamentis at OPenn

On Boethius' life and works

Blessed Severinus Boethius

at Patron Saints Index * Blackwood, Stephen.br>''The Meters of Boethius: Rhythmic Therapy in the Consolation of Philosophy.''

* * * Phillips, Philip Edward

Boethius

at ''The Online Library of Liberty''

–

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the soverei ...

On Boethius' logic and philosophy

*The Philosophical Works of Boethius. Editions and Translations

{{Authority control 477 births 524 deaths 5th-century Italo-Roman people 6th-century Christian saints 6th-century Christian theologians 6th-century Italo-Roman people 6th-century Italian writers 6th-century Latin writers 6th-century mathematicians 6th-century philosophers 6th-century Roman consuls Ancient Roman rhetoricians Anicii Augustinian philosophers Burials at San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro Deaths by blade weapons Executed ancient Roman people Executed philosophers Executed writers Greek–Latin translators Imperial Roman consuls Last of the Romans Latin commentators on Aristotle Magistri officiorum Manlii Music theorists People of the Ostrogothic Kingdom Philosophers of Roman Italy Catholic philosophers Neoplatonists Roman-era philosophers Italian logicians