Beringia land bridge-noaagov.gif on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

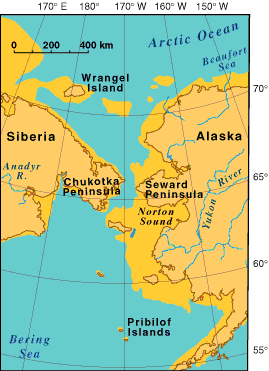

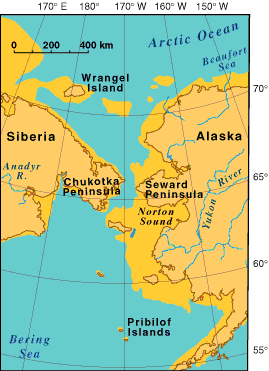

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the

The remains of

The remains of

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500 YBP and was the most recent glacial period within the current ice age, which occurred during the last years of the Pleistocene era. The Ice Age reached its peak during the

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500 YBP and was the most recent glacial period within the current ice age, which occurred during the last years of the Pleistocene era. The Ice Age reached its peak during the

Entering America, Northeast Asia and Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum (ed. Madsen DB), pp. 29–61. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press

/ref> Commencing from YBP (

File:ArtemisiaVulgaris.jpg,

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of human migration to the Americas from Asia about 20,000 years ago. An open

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of human migration to the Americas from Asia about 20,000 years ago. An open

How primates crossed continents

/ref> By 20 million years ago, evidence in North America shows a further interchange of mammalian species. Some, like the ancient saber-toothed cats, have a recurring geographical range: Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America. The only way they could reach the New World was by the Bering land bridge. Had this bridge not existed at that time, the fauna of the world would be very different.

CBC News: New map of Beringia 'opens your imagination' to what landscape looked like 18,000 years ago

Shared Beringian Heritage Program

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

includes animation showing the gradual disappearance of the Bering land bridge

Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre

The Fertile Shore

{{Authority control 1930s neologisms Historical geology Ice ages Last Glacial Maximum Pleistocene Paleo-Indian period Natural history of North America Natural history of Asia Prehistory of the Arctic Natural history of Russia Bering Sea Regions of North America North Asia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River

The Lena (russian: Ле́на, ; evn, Елюенэ, ''Eljune''; sah, Өлүөнэ, ''Ölüöne''; bua, Зүлхэ, ''Zülkhe''; mn, Зүлгэ, ''Zülge'') is the easternmost of the three great Siberian rivers that flow into the Arctic Ocean ...

in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea

Chukchi Sea ( rus, Чуко́тское мо́ре, r=Chukotskoye more, p=tɕʊˈkotskəjə ˈmorʲɪ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west b ...

; and on the south by the tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula. It includes the Chukchi Sea

Chukchi Sea ( rus, Чуко́тское мо́ре, r=Chukotskoye more, p=tɕʊˈkotskəjə ˈmorʲɪ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west b ...

, the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea (, ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Ameri ...

, the Bering Strait, the Chukchi and Kamchatka Peninsulas in Russia as well as Alaska in the United States and the Yukon in Canada.

The area includes land lying on the North American Plate and Siberian land east of the Chersky Range. At certain times in prehistory, it formed a land bridge that was up to wide at its greatest extent and which covered an area as large as British Columbia and Alberta together, totaling approximately . Today, the only land that is visible from the central part of the Bering land bridge are the Diomede Islands, the Pribilof Islands of St. Paul and St. George, St. Lawrence Island

St. Lawrence Island ( ess, Sivuqaq, russian: Остров Святого Лаврентия, Ostrov Svyatogo Lavrentiya) is located west of mainland Alaska in the Bering Sea, just south of the Bering Strait. The village of Gambell, located on t ...

, St. Matthew Island

St. Matthew Island (russian: Остров Святого Матвея) is an uninhabited, remote island in the Bering Sea in Alaska, west-northwest of Nunivak Island. The entire island's natural scenery and wildlife is protected as it is part of ...

, and King Island King Island, Kings Island or King's Island may refer to:

Australia

* King Island (Queensland)

* King Island, at Wellington Point, Queensland

* King Island (Tasmania)

** King Island Council, the local government area that contains the Tasmanian is ...

.

The term ''Beringia'' was coined by the Swedish botanist Eric Hultén in 1937, from the Danish explorer Vitus Bering. During the ice ages, Beringia, like most of Siberia and all of North and Northeast China, was not glaciated because snowfall was very light. It was a grassland steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslands, ...

, including the land bridge, that stretched for hundreds of kilometres into the continents on either side.

It is believed that a small human population of at most a few thousand arrived in Beringia from eastern Siberia during the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

before expanding into the settlement of the Americas sometime after 16,500 years Before Present (YBP). This would have occurred as the American glaciers blocking the way southward melted, but before the bridge was covered by the sea about 11,000 YBP.

Before European colonization, Beringia was inhabited by the Yupik peoples on both sides of the straits. This culture remains in the region today along with others. In 2012, the governments of Russia and the United States announced a plan to formally establish "a transboundary area of shared Beringian heritage". Among other things this agreement would establish close ties between the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

The Bering Land Bridge National Preserve is one of the most remote Protected areas of the United States, located on the Seward Peninsula. The National Preserve protects a remnant of the Bering Land Bridge that connected Asia with North America m ...

and the Cape Krusenstern National Monument in the United States and Beringia National Park

Beringia National Park (russian: Берингия) is on the eastern tip of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug ("Chukotka"), the most northeastern region of Russia. It is on the western (i.e., Asian) side of the Bering Strait.

Overview

Until 11,000 BCE ...

in Russia.

Geography

The remains of

The remains of Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of ...

mammals that had been discovered on the Aleutians and islands in the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea (, ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Ameri ...

at the close of the nineteenth century indicated that a past land connection might lie beneath the shallow waters between Alaska and Chukotka. The underlying mechanism was first thought to be tectonics, but by 1930 changes in the ice mass balance, leading to global sea-level fluctuations were viewed as the cause of the Bering land bridge. In 1937, Eric Hultén proposed that around the Aleutians and the Bering Strait region were tundra plants that had originally dispersed from a now-submerged plain between Alaska and Chukotka, which he named Beringia after the Dane Vitus Bering who had sailed into the strait in 1728. The American arctic geologist David Hopkins redefined Beringia to include portions of Alaska and Northeast Asia. Beringia was later regarded as extending from the Verkhoyansk Mountains in the west to the Mackenzie River in the east. The distribution of plants in the genera '' Erythranthe'' and '' Pinus'' are good examples of this, as very similar genera members are found in Asia and the Americas.

During the Pleistocene epoch, global cooling led periodically to the expansion of glaciers and the lowering of sea levels. This created land connections in various regions around the globe. Today, the average water depth of the Bering Strait is ; therefore the land bridge opened when the sea level dropped more than below the current level. A reconstruction of the sea-level history of the region indicated that a seaway existed from YBP, a land bridge from YBP, intermittent connection from YBP, a land bridge from YBP, followed by a Holocene sea-level rise that reopened the strait. Post-glacial rebound has continued to raise some sections of coast.

During the last glacial period, enough of the earth's water became frozen in the great ice sheets covering North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

and Europe to cause a drop in sea levels. For thousands of years the sea floors of many interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene in ...

shallow seas were exposed, including those of the Bering Strait, the Chukchi Sea

Chukchi Sea ( rus, Чуко́тское мо́ре, r=Chukotskoye more, p=tɕʊˈkotskəjə ˈmorʲɪ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west b ...

to the north, and the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea (, ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Ameri ...

to the south. Other land bridges around the world have emerged and disappeared in the same way. Around 14,000 years ago, mainland Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

was linked to both New Guinea and Tasmania, the British Isles became an extension of continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

via the dry beds of the English Channel and North Sea, and the dry bed of the South China Sea linked Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, Java, and Borneo to Indochina.

Beringian refugium

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500 YBP and was the most recent glacial period within the current ice age, which occurred during the last years of the Pleistocene era. The Ice Age reached its peak during the

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500 YBP and was the most recent glacial period within the current ice age, which occurred during the last years of the Pleistocene era. The Ice Age reached its peak during the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, when ice sheets began advancing from 33,000YBP and reached their maximum limits 26,500YBP. Deglaciation commenced in the Northern Hemisphere approximately 19,000YBP and in Antarctica approximately 14,500 yearsYBP, which is consistent with evidence that glacial meltwater was the primary source for an abrupt rise in sea level 14,500YBP and the bridge was finally inundated around 11,000 YBP. The fossil evidence from many continents points to the extinction of large animals, termed Pleistocene megafauna, near the end of the last glaciation.

During the Ice Age a vast, cold and dry Mammoth steppe stretched from the arctic islands southwards to China, and from Spain eastwards across Eurasia and over the Bering land bridge into Alaska and the Yukon where it was blocked by the Wisconsin glaciation. The land bridge existed because sea-levels were lower because more of the planet's water than today was locked up in glaciers. Therefore, the flora and fauna of Beringia were more related to those of Eurasia rather than North America. Beringia received more moisture and intermittent maritime cloud cover from the north Pacific Ocean than the rest of the Mammoth steppe, including the dry environments on either side of it. This moisture supported a shrub-tundra habitat that provided an ecological refugium for plants and animals. In East Beringia 35,000 YBP, the northern arctic areas experienced temperatures degrees warmer than today but the southern sub-Arctic regions were degrees cooler. During the LGM 22,000 YBP the average summer temperature was degrees cooler than today, with variations of degrees cooler on the Seward Peninsula to cooler in the Yukon. In the driest and coldest periods of the Late Pleistocene, and possibly during the entire Pleistocene, moisture occurred along a north–south gradient with the south receiving the most cloud cover and moisture due to the air-flow from the North Pacific.

In the Late Pleistocene, Beringia was a mosaic of biological communities.Hoffecker JF, Elias SA. 2007 Human ecology of Beringia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.Elias SA, Crocker B. 2008 The Bering land bridge: a moisture barrier to the dispersal of steppe-tundra biota? Q. Sci. Rev. 27, 2473–83Brigham-Grette J, Lozhkin AV, Anderson PM, Glushkova OY. 2004 Paleoenvironmental conditions in Western Beringia before and during the Last Glacial Maximum. IEntering America, Northeast Asia and Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum (ed. Madsen DB), pp. 29–61. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press

/ref> Commencing from YBP (

MIS

MIS or mis may refer to:

Science and technology

* Management information system

* Marine isotope stage, stages of the Earth's climate

* Maximal independent set, in graph theory

* Metal-insulator-semiconductor, e.g., in MIS capacitor

* Minimally in ...

3), steppe–tundra vegetation dominated large parts of Beringia with a rich diversity of grasses and herbs.Sher AV, Kuzmina SA, Kuznetsova TV, Sulerzhitsky LD. 2005 New insights into the Weichselian environment and climate of the East Siberian Arctic, derived from fossil insects, plants, and mammals. Q. Sci. Rev. 24, 533–69. There were patches of shrub tundra with isolated refugia of larch (''Larix'') and spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

(''Picea'') forests with birch (''Betula'') and alder (''Alnus'') trees. It has been proposed that the largest and most diverse megafaunal community residing in Beringia at this time could only have been sustained in a highly diverse and productive environment. Analysis at Chukotka on the Siberian edge of the land bridge indicated that from YBP (MIS 3 to MIS 2) the environment was wetter and colder than the steppe–tundra to the east and west, with warming in parts of Beringia from YBP. These changes provided the most likely explanation for mammal migrations after YBP, as the warming provided increased forage for browsers and mixed feeders. Beringia did not block the movement of most dry steppe-adapted large species such as saiga antelope, woolly mammoth, and caballid horses. However, from the west, the woolly rhino

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhinoceros was a me ...

went no further east than the Anadyr River, and from the east North American camel North American camel may refer to:

*Camelini, a tribe of mammals with several prehistoric genera which lived in North America, including:

**''Camelops''

**''Megatylopus

''Megatylopus'' (also known as the North American camel) is an extinct genu ...

s, the American kiang-like equids, the short-faced bear, bonnet-headed muskox

''Bootherium'' (Greek: "ox" (boos), "beast" (therion)) is an extinct bovid genus from the middle to late Pleistocene of North America which contains a single species, ''Bootherium bombifrons''.McKenna & Bell, 1997, p. 442. Vernacular names for ' ...

en, and American badger did not travel west. At the beginning of the Holocene, some mesic habitat-adapted species left the refugium and spread westward into what had become tundra-vegetated northern Asia and eastward into northern North America.

The latest emergence of the land bridge was years ago. However, from YBP the Laurentide Ice Sheet fused with the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which blocked gene flow between Beringia (and Eurasia) and continental North America. The Yukon corridor opened between the receding ice sheets YBP, and this once again allowed gene flow between Eurasia and continental North America until the land bridge was finally closed by rising sea levels YBP. During the Holocene, many mesic-adapted species left the refugium and spread eastward and westward, while at the same time the forest-adapted species spread with the forests up from the south. The arid adapted species were reduced to minor habitats or became extinct.

Beringia constantly transformed its ecosystem as the changing climate affected the environment, determining which plants and animals were able to survive. The land mass could be a barrier as well as a bridge: during colder periods, glaciers advanced and precipitation levels dropped. During warmer intervals, clouds, rain and snow altered soils and drainage patterns. Fossil remains show that spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

, birch and poplar once grew beyond their northernmost range today, indicating that there were periods when the climate was warmer and wetter. The environmental conditions were not homogenous in Beringia. Recent stable isotope studies of woolly mammoth bone collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

demonstrate that western Beringia ( Siberia) was colder and drier than eastern Beringia ( Alaska and Yukon), which was more ecologically diverse. Mastodons, which depended on shrubs for food, were uncommon in the open dry tundra landscape characteristic of Beringia during the colder periods. In this tundra, mammoths flourished instead.

The extinct pine species ''Pinus matthewsii

''Pinus matthewsii'' is an extinction, extinct species of conifer in the pine family. The species is solely known from the Pliocene sediments exposed at Ch’ijee's Bluff on the Porcupine River near Old Crow, Yukon, Canada.

Type locality

''Pinu ...

'' has been described from Pliocene sediments in the Yukon areas of the refugium.

The paleo-environment changed across time. Below is a gallery of some of the plants that inhabited eastern Beringia before the beginning of the Holocene.

Artemisia

Artemisia may refer to:

People

* Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC), queen of Halicarnassus under the First Persian Empire, naval commander during the second Persian invasion of Greece

* Artemisia II of Caria (died 350 BC), queen of Caria under th ...

File:Carex halleriana.jpg, Cyperaceae

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' w ...

( sedges)

File:Grassflowers.jpg, Gramineae ( grasses)

File:Salix-lanata-total.JPG, Salix ( willow)

Gray wolf

The earliest ''Canis lupus'' specimen was a fossil tooth discovered at Old Crow, Yukon, Canada. The specimen was found in sediment dated 1 million YBP, however the geological attribution of this sediment is questioned. Slightly younger specimens were discovered at Cripple Creek Sump,Fairbanks

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the po ...

, Alaska, in strata dated 810,000 YBP. Both discoveries point to an origin of these wolves in eastern Beringia during the Middle Pleistocene. Grey wolves suffered a species-wide population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as specicide, widespread violen ...

(reduction) approximately 25,000 YBP during the Last Glacial Maximum. This was followed by a single population of modern wolves expanding out of their Beringia refuge to repopulate the wolf's former range, replacing the remaining Late Pleistocene wolf populations across Eurasia and North America as they did so.

Human habitation

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of human migration to the Americas from Asia about 20,000 years ago. An open

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of human migration to the Americas from Asia about 20,000 years ago. An open corridor

Corridor or The Corridor may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''The Corridor'' (1968 film), a 1968 Swedish drama film

* ''The Corridor'' (1995 film), a 1995 Lithuanian drama film

* ''The Corridor'' (2010 film), a 2010 Canadia ...

through the ice-covered North American Arctic was too barren to support human migrations before around 12,600 YBP. A study has indicated that the genetic imprints of only 70 of all the individuals who settled and traveled the land bridge into North America are visible in modern descendants. This genetic bottleneck finding is an example of the founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, using ...

and does not imply that only 70 individuals crossed into North America at the time; rather, the genetic material of these individuals became amplified in North America following isolation from other Asian populations.

Seagoing coastal settlers may also have crossed much earlier, but there is no scientific consensus

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

Consensus is achieved through scholarly communication at confe ...

on this point, and the coastal sites that would offer further information now lie submerged in up to a hundred metres of water offshore. Land animals migrated through Beringia as well, introducing to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

species that had evolved in Asia, like mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s such as proboscidea

The Proboscidea (; , ) are a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. From ...

ns and American lions, which evolved into now-extinct endemic North American species. Meanwhile, equids

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus'', w ...

and camelids that had evolved in North America (and later became extinct there) migrated into Asia as well at this time.

A 2007 analysis of mtDNA found evidence that a human population lived in genetic isolation on the exposed Beringian landmass during the Last Glacial Maximum for approximately 5,000 years. This population is often referred to as the Beringian Standstill population. A number of other studies, relying on more extensive genomic data, have come to the same conclusion. Genetic and linguistic data demonstrate that at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, as sea levels rose, some members of the Beringian Standstill Population migrated back into eastern Asia while others migrated into the Western Hemisphere, where they became the ancestors of the indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere. Environmental selection on this Beringian Standstill Population has been suggested for genetic variation in the Fatty Acid Desaturase gene cluster and the ectodysplasin A receptor gene. Using Y Chromosome data Pinotti et al. have estimated the Beringian Standstill to be less than 4600 years and taking place between 19.5 kya and 15 kya.

Previous connections

Biogeographical

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, i ...

evidence demonstrates previous connections between North America and Asia. Similar dinosaur fossils occur both in Asia and in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. For instance the dinosaur ''Saurolophus

''Saurolophus'' (; meaning "lizard crest") is a genus of large hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of Asia and North America, that lived in what is now the Horseshoe Canyon and Nemegt formations about 70 million to 68 million ...

'' was found in both Mongolia and western North America. Relatives of '' Troodon'', '' Triceratops'', and even '' Tyrannosaurus rex'' all came from Asia.

Fossil evidence indicates an exchange of primates between North America and Asia around 55.8 million years ago./ref> By 20 million years ago, evidence in North America shows a further interchange of mammalian species. Some, like the ancient saber-toothed cats, have a recurring geographical range: Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America. The only way they could reach the New World was by the Bering land bridge. Had this bridge not existed at that time, the fauna of the world would be very different.

See also

* Ancient Beringian * Bering Strait crossing * Bluefish Caves *Little John (archeological site)

Little John is an archaeological site in Yukon, Canada, located northwest of the White River First Nation community of Beaver Creek, from which human artefacts and ancient animal bones have been radiocarbon dated to 14,000 years before present ...

* Geologic time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochrono ...

* Last glacial period

* Paleoshoreline

* Pleistocene

* Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre

The Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre is a research and exhibition facility located at km 1423 (Mile 886) on the Alaska Highway in Whitehorse, Yukon, which opened in 1997. The focus of the interpretive centre is the story of Beringia, the 3200&n ...

References

Further reading

* Demuth, Bathsheba (2019) '' Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait''. W. W. Norton & Company. . * * * * *Pielou, E. C.

Evelyn Chrystalla "E.C." Pielou (February 20, 1924 – July 16, 2016) was a Canadian statistical ecologist.

Biography

She began her career as a researcher for the Canadian Department of Forestry (1963–64) and the Canadian Department of Agricu ...

, ''After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 1992

*

External links

CBC News: New map of Beringia 'opens your imagination' to what landscape looked like 18,000 years ago

Shared Beringian Heritage Program

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

includes animation showing the gradual disappearance of the Bering land bridge

Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre

The Fertile Shore

{{Authority control 1930s neologisms Historical geology Ice ages Last Glacial Maximum Pleistocene Paleo-Indian period Natural history of North America Natural history of Asia Prehistory of the Arctic Natural history of Russia Bering Sea Regions of North America North Asia