Arapahoe County Justice Center.JPG on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of

The Arapaho recognize five main divisions among their people, each speaking a different dialect and apparently representing as many originally distinct but cognate tribes. Through much of Arapaho history, each tribal nation maintained a separate ethnic identity, although they occasionally came together and acted as political allies.

Each spoke mutually intelligible dialects, which differed from Arapaho proper. Dialectally, the Haa'ninin, Beesowuunenno', and Hinono'eino were closely related. Arapaho elders claimed that the Hánahawuuena dialect was the most difficult to comprehend of all the dialects.

In his classic ethnographic study,

The Arapaho recognize five main divisions among their people, each speaking a different dialect and apparently representing as many originally distinct but cognate tribes. Through much of Arapaho history, each tribal nation maintained a separate ethnic identity, although they occasionally came together and acted as political allies.

Each spoke mutually intelligible dialects, which differed from Arapaho proper. Dialectally, the Haa'ninin, Beesowuunenno', and Hinono'eino were closely related. Arapaho elders claimed that the Hánahawuuena dialect was the most difficult to comprehend of all the dialects.

In his classic ethnographic study,

The

The

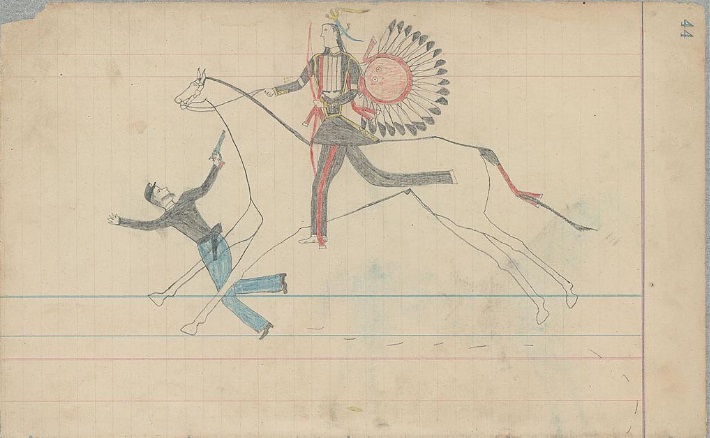

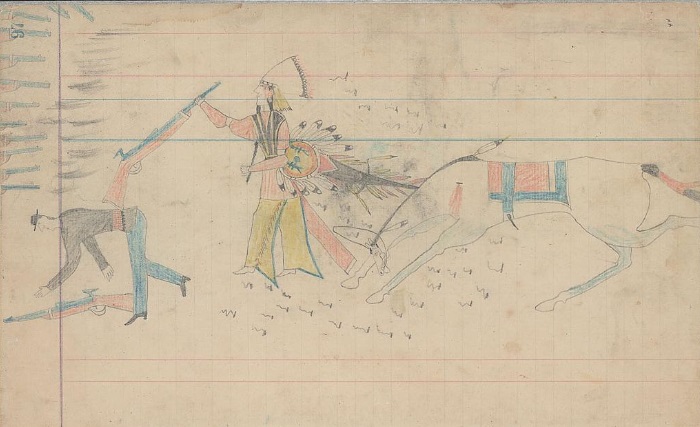

A large part of Arapaho society was based around the warrior. Most young men sought this role. After adopting use of the horse, the Arapaho quickly became master horsemen and highly skilled at fighting on horseback. Warriors had larger roles than combat in the society. They were expected to keep peace among the camps, provide food and wealth for their families, and guard the camps from attacks.

Like other plains Indians, including their Cheyenne allies, the Arapaho have a number of distinct military societies. Each of the eight Arapaho military societies had their own unique initiation rites, pre- and post- battle ceremonies and songs, regalia, and style of combat. Unlike their Cheyenne, Lakota, and Dakota allies, the Arapaho military societies were age based. Each age level had its own society for prestigious or promising warriors of the matching age. As the warriors aged, they may graduate to the next society.

Warriors often painted their face and bodies with war paint, as well as their horses, for spiritual empowerment. Each warrior created a unique design for the war paint which they often wore into battle. Feathers from birds, particularly eagle feathers, were also worn in battle as symbols of prestige and for reasons similar to war paint. Before setting out for war, the warriors organized into war parties. War parties were made up of individual warriors and a selected war chief. The title of war chief must be earned through a specific number of acts of bravery in battle known as

A large part of Arapaho society was based around the warrior. Most young men sought this role. After adopting use of the horse, the Arapaho quickly became master horsemen and highly skilled at fighting on horseback. Warriors had larger roles than combat in the society. They were expected to keep peace among the camps, provide food and wealth for their families, and guard the camps from attacks.

Like other plains Indians, including their Cheyenne allies, the Arapaho have a number of distinct military societies. Each of the eight Arapaho military societies had their own unique initiation rites, pre- and post- battle ceremonies and songs, regalia, and style of combat. Unlike their Cheyenne, Lakota, and Dakota allies, the Arapaho military societies were age based. Each age level had its own society for prestigious or promising warriors of the matching age. As the warriors aged, they may graduate to the next society.

Warriors often painted their face and bodies with war paint, as well as their horses, for spiritual empowerment. Each warrior created a unique design for the war paint which they often wore into battle. Feathers from birds, particularly eagle feathers, were also worn in battle as symbols of prestige and for reasons similar to war paint. Before setting out for war, the warriors organized into war parties. War parties were made up of individual warriors and a selected war chief. The title of war chief must be earned through a specific number of acts of bravery in battle known as

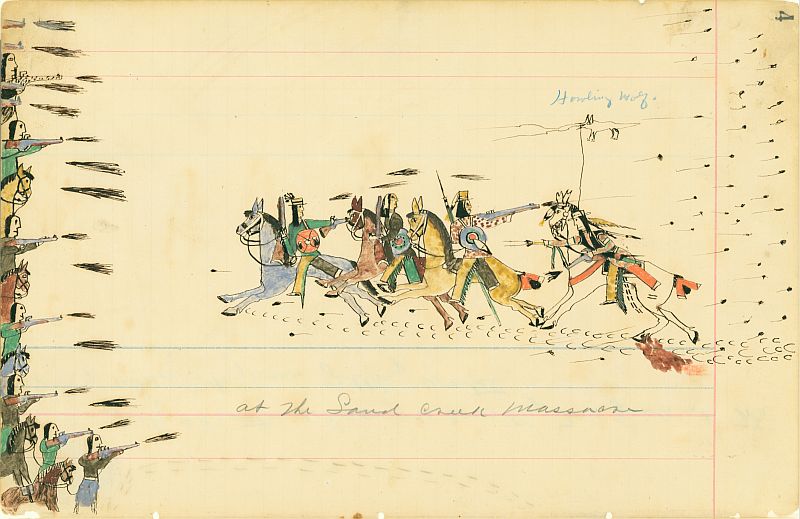

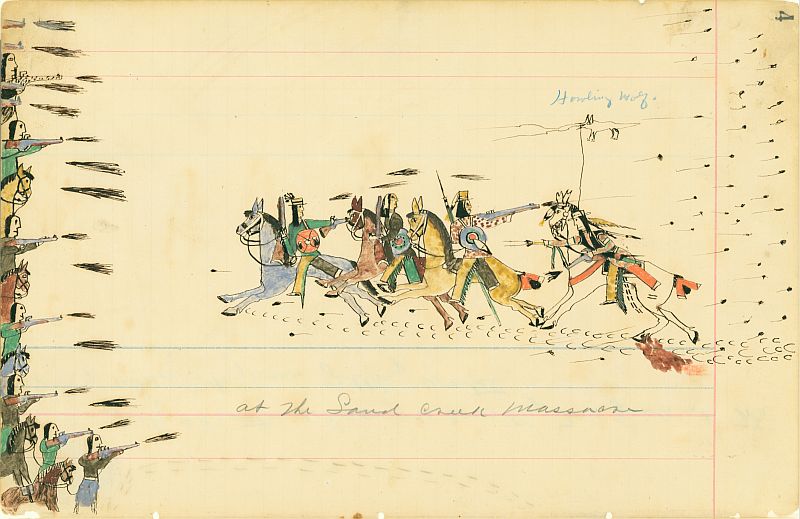

In November 1864, the Colorado militia, led by Colonel

In November 1864, the Colorado militia, led by Colonel

The events at Sand Creek sparked outrage among the Arapaho and Cheyenne, resulting in three decades of war between them and the United States. Much of the hostilities took place in Colorado, leading to many of the events being referred to as part of the so-called

The events at Sand Creek sparked outrage among the Arapaho and Cheyenne, resulting in three decades of war between them and the United States. Much of the hostilities took place in Colorado, leading to many of the events being referred to as part of the so-called

Little Raven (ca. 1810–1889).

Oklahoma Historical Society's ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture''. (accessed 2 July 2012) Among those that signed the treaty was Chief Little Raven. Those that did not sign the treaty were called "hostile" and were continually pursued by the US Army and their Indian scouts. The last major battle between the Arapaho and the US on the southern plains was the

Red Cloud's War was a war fought between soldiers of the United States and the allied

Red Cloud's War was a war fought between soldiers of the United States and the allied

The Great Sioux War of 1876–77, also known as the Black Hills War or Great Cheyenne War, was a major conflict that was fought between the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho alliance and the US Army. The war was started after miners and settlers traveled into the

The Great Sioux War of 1876–77, also known as the Black Hills War or Great Cheyenne War, was a major conflict that was fought between the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho alliance and the US Army. The war was started after miners and settlers traveled into the

The most significant battle of the war was the

The most significant battle of the war was the

/ref> Women (and ''haxu'xan'' ( Two Spirits)) are traditionally in charge of food preparation and dressing hides to make clothing and bedding, saddles, and housing materials.The Arapaho Project: Clothes

/ref> The Arapaho have historically had social and spiritual roles for those who are known in contemporary Native cultures as

2007 (retrieved February 7, 2009)

Little Raven (c. 1810–1889).

Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved February 7, 2009) *

The Northern Arapaho Tribe

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090613061905/http://www.arapahochs.com/ Arapaho Charter High School

Arapaho artwork

in the collection of the

Info Please: Arapaho

The Arapaho language: Documentation and Revitalization

{{Authority control Algonquian peoples Comanche campaign Eastern Plains Great Sioux War of 1876 Native American tribes in Colorado Native American tribes in Nebraska Native American tribes in Oklahoma Native American tribes in Wyoming Plains tribes

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

. They were close allies of the Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

and Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, ...

.

By the 1850s, Arapaho bands formed two tribes, namely the Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho. Since 1878, the Northern Arapaho have lived with the Eastern Shoshone

Eastern Shoshone are Shoshone who primarily live in Wyoming and in the northeast corner of the Great Basin where Utah, Idaho and Wyoming meet and are in the Great

Basin classification of Indigenous People. They lived in the Rocky Mountains d ...

on the Wind River Reservation

The Wind River Indian Reservation, in the west-central portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming, is shared by two Native American tribes, the Eastern Shoshone ( shh, Gweechoon Deka, ''meaning: "buffalo eaters"'') and the Northern Arapaho ( arp, ho ...

in Wyoming and are federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

as the Arapahoe Tribe of the Wind River Reservation

The Wind River Indian Reservation, in the west-central portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming, is shared by two Native American tribes, the Eastern Shoshone ( shh, Gweechoon Deka, ''meaning: "buffalo eaters"'') and the Northern Arapaho ( arp, ho ...

. The Southern Arapaho live with the Southern Cheyenne

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

History

The Cheyennes and Arapahos are two distinct tribes with distinct histories. The Cheyenne (Ts ...

in Oklahoma. Together, their members are enrolled as the federally recognized Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

Names

It is uncertain where the word 'Arapaho' came from. Europeans may have derived it from thePawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

word for "trader", ''iriiraraapuhu'', or it may have been a corruption of a Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

word for "tattoo", ''alapúuxaache''. The Arapaho autonym

Autonym may refer to:

* Autonym, the name used by a person to refer to themselves or their language; see Exonym and endonym

* Autonym (botany), an automatically created infrageneric or infraspecific name

See also

* Nominotypical subspecies, in zo ...

is or ("our people" or "people of our own kind"). They refer to their tribe as (Arapaho Nation). The Cheyenne called them or ("People of the Sky" or "Cloud People"); the Dakota as ("Blue Cloud Men"), and the Lakota and Assiniboine referred to them as ("Blue Sky People").

The Caddo ( or – "pierced nose people") called them , the Wichita () , and the Comanche , all names signifying "dog-eaters". The Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

, Ute and other tribes also referred to them with names signifying "dog-eaters".

The Northern Arapaho, who called themselves or ("white sage men"), were known as or ("red willow men") to the Southern Arapaho, whereas the latter were called by their northern kin or ("Southerners"). The Northern Arapaho were also known as ("blood-soup men").

The Cheyenne adapted the Arapaho terms and referred to the Northern Arapaho as ''Vanohetan'' or ''Vanohetaneo / Váno'étaneo'o'' ("Sage (Brush) People") and to the Southern Arapaho as ''Nomsen'nat'' or ''Nomsen'eo'' ("Southerners").

Historic political and dialect Arapaho divisions and bands

The Arapaho recognize five main divisions among their people, each speaking a different dialect and apparently representing as many originally distinct but cognate tribes. Through much of Arapaho history, each tribal nation maintained a separate ethnic identity, although they occasionally came together and acted as political allies.

Each spoke mutually intelligible dialects, which differed from Arapaho proper. Dialectally, the Haa'ninin, Beesowuunenno', and Hinono'eino were closely related. Arapaho elders claimed that the Hánahawuuena dialect was the most difficult to comprehend of all the dialects.

In his classic ethnographic study,

The Arapaho recognize five main divisions among their people, each speaking a different dialect and apparently representing as many originally distinct but cognate tribes. Through much of Arapaho history, each tribal nation maintained a separate ethnic identity, although they occasionally came together and acted as political allies.

Each spoke mutually intelligible dialects, which differed from Arapaho proper. Dialectally, the Haa'ninin, Beesowuunenno', and Hinono'eino were closely related. Arapaho elders claimed that the Hánahawuuena dialect was the most difficult to comprehend of all the dialects.

In his classic ethnographic study, Alfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber (June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the first ...

identified these five nations from south to north:

* Nanwacinaha'ana, Nawathi'neha ("Toward the South People") or Nanwuine'nan / Noowo3iineheeno' ("Southern People"). Their now-extinct language dialect – Nawathinehena – was the most divergent from the other Arapaho tribes.

* Hánahawuuena, Hananaxawuune'nan or Aanû'nhawa ("Rock Men" or "Rock People"), occupying territory adjacent to, but further north of the Nanwacinaha'ana, spoke the now-extinct Ha'anahawunena dialect.

* Hinono'eino or Hinanae'inan ("Arapaho proper") spoke the Arapaho language (Heenetiit).

* Beesowuunenno', Baasanwuune'nan or Bäsawunena ("Big Lodge People" or "Brush-Hut/Shelter People") resided further north of the Hinono'eino. Their war parties used temporary brush shelters similar to the dome-shaped shade or Sweat lodge of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

Algonquian peoples. They are said to have migrated from their former territory near the Lakes more recently than the other Arapaho tribes. (Note: many people say their name means "Great Lakes People" or "Big Water People".) They spoke the now-extinct Besawunena (''Beesoowuuyeitiit'' – "Big Lodge/Great Lakes language") dialect.

* Haa'ninin, A'aninin or A'ani ("White Clay People" or "Lime People"), the northernmost tribal group; they retained a distinct ethnicity and were known to the French as the historic Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

. In Blackfoot they were called Atsina (''Atsíína'' – "like a Cree", i.e. "enemy", or ''Piik-siik-sii-naa'' – "snakes", i.e. "enemies"). After they separated, the other Arapaho peoples, who considered them inferior, called them ''Hitúnĕna'' or ''Hittiuenina'' ("Begging Men", "Beggars", or more exactly "Spongers"). They speak the nearly extinct Gros Ventre (Ananin, Ahahnelin) language dialect (called by the Arapaho ''Hitouuyeitiit'' – "Begging Men Language"), there is evidence that the southern Haa'ninin tribal group, the ''Staetan band'', together with bands of the later political division of the Northern Arapaho, spoke the Besawunena dialect.

Before their historic geo-political ethnogenesis, each tribal-nation had a principal

headman. The exact date of the ethnic fusion or fission of each social division is not known. The elders say that the ''Hinono'eino'' ("Arapaho proper") and ''Beesowuunenno'' ("Big Lodge People" or "Brush-Hut/Shelter People") fought over the tribal symbols – the sacred pipe and lance. Both sacred objects traditionally were kept by the ''Beesowuunenno''. The different tribal-nations lived together and the ''Beesowuunenno'' have dispersed for at least 150 years among the formerly distinct Arapaho tribal groups.

By the late 18th century, the four divisions south of the ''Haa'ninin'' ("White Clay People" or "Lime People") or '' Gros Ventre (Atsina)'' consolidated into the Arapaho. Only the Arapaho and Gros Ventre (Atsina) identified as separate tribal-nations.

While living on the Great Plains, the ''Hinono'eino'' (all Arapaho bands south of the ''Haa'ninin'') divided historically into two geopolitical social divisions:

* Northern Arapaho or Nank'haanseine'nan ("Sagebrush People"), Nookhose'iinenno ("White Sage People"); are called by the Southern Arapaho ''Bo'ooceinenno'' or ''Baachinena'' ("red willow men"); the Kiowa know them as ''Tägyäko'' ("Sagebrush People"), a translation of their proper name. They keep the sacred tribal articles, and are considered the nucleus or mother tribe of the Arapaho, being indicated in the Plains Indian Sign Language

Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), also known as Hand Talk, Plains Sign Talk, and First Nation Sign Language, is a trade language, formerly trade pidgin, that was once the lingua franca across what is now central Canada, the central and weste ...

(''Bee3sohoet'') by the sign for "mother people". They absorbed the historic ''Hánahawuuena'' and ''Beesowuunenno''. An estimated 50 persons of Beesowuunenno' lineage are included among the Northern Arapaho, and perhaps a few with the other two main divisions.

* Southern Arapaho, Náwunena or Noowunenno ("Southern People"), are called by the Northern Arapaho Nawathi'neha ("Southerners"); the Kiowa know them as ''Ähayädal'', the (plural) name for the wild plum. The sign for the Southern Arapaho is made by rubbing the index finger against the side of the nose. They absorbed the historic ''Nanwuine'nan / Noowo3iineheeno'' ("Southern People") and some ''Beesowuunenno''.

Language

Arapaho language

The Arapaho (Arapahoe) language () is one of the Plains Algonquian languages, closely related to Gros Ventre and other Arapahoan languages. It is spoken by the Arapaho of Wyoming and Oklahoma. Speakers of Arapaho primarily live on the Wind Ri ...

is currently spoken in two different dialects, and it is considered to be a member of the Algonquian language family. The number of fluent speakers of Northern Arapaho dwindles at 250, most living on the Wind River Reservation

The Wind River Indian Reservation, in the west-central portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming, is shared by two Native American tribes, the Eastern Shoshone ( shh, Gweechoon Deka, ''meaning: "buffalo eaters"'') and the Northern Arapaho ( arp, ho ...

in Wyoming, while the number of Southern Arapaho speakers is even more scarce, only a handful of people speak it, all advanced in age.

According to Cowell & Moss's 2008 study of the Arapaho language, the Northern Arapaho have made a great effort to maintain the language through establishing the Language and Culture Commission. By producing audio and visual materials, they have provided ways for younger generations to learn the language. They have matched this effort with a preschool immersion program and is offered all throughout grade school. However, the number of students that take the subject is wavering and those who learn typically only retain a selection of memorized vocabulary. There is widespread interest in keeping the language alive for the Northern Arapaho, and their outlook remains positive in their endeavors to perpetuate the learning of Arapaho in schools and among their children and young people. However, this attitude is often counteracted by the lack of true commitment and willingness to really learn and become fluent, underscored by a misunderstanding of its deep roots and purpose.

For Southern Arapaho, the language is not quite as valued as it is on the Wind River Reservation. Most have lost interest in learning or maintaining it, and until recently, there were little to no efforts to preserve their dialect. There is a small number who have begun online courses conducted via video in an attempt to revitalize a desire to learn it, and popularity has increased over the past few years.

Histories

Early history

Around 3,000 years ago, the ancestral Arapaho-speaking people (''Heeteinono'eino'') lived in the western Great Lakes region along the Red River Valley in what is classified as present-dayManitoba

, image_map = Manitoba in Canada 2.svg

, map_alt = Map showing Manitoba's location in the centre of Southern Canada

, Label_map = yes

, coordinates =

, capital = Winn ...

, Canada and Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

, United States. There the Arapaho were an agricultural people who grew crops, including maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

. Following European colonization in eastern Canada, together with the early Cheyenne people (''Hitesiino), the Arapaho were forced to migrate westward onto the eastern Great Plains by the Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

. They were numerous and powerful, having obtained guns from their French trading allies.

The ancestors of the Arapaho people entered the Great Plains the western Great Lakes region sometime before 1700. During their early history on the plains, the Arapaho lived on the northern plains from the South Saskatchewan River

The South Saskatchewan River is a major river in Canada that flows through the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

For the first half of the 20th century, the South Saskatchewan would completely freeze over during winter, creating spectacular ...

in Canada south to Montana, Wyoming, and western South Dakota. Before the Arapaho acquired horses, they used domestic dogs as pack animals to pull their travois

A travois (; Canadian French, from French , a frame for restraining horses; also obsolete travoy or travoise) is a historical frame structure that was used by indigenous peoples, notably the Plains Aboriginals of North America, to drag loads ove ...

. The Arapaho acquired horses in the early 1700s from other tribes, which changed their way of life. They became nomadic people, using the horses as pack and riding animals. They could transport greater loads, and travel more easily by horseback to hunt more easily and widely, increasing their success in hunting on the Plains.

Gradually, the Arapaho moved farther south, split into the closely allied Northern and Southern Arapaho, and established a large joint territory spanning land in southern Montana, most of Wyoming, the Nebraska Panhandle, central and eastern Colorado, western Oklahoma, and extreme western Kansas. A large group of Arapaho split from the main tribe and became an independent people, commonly known as the Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

(as named by the French) or Atsina. The name Gros Ventre, meaning "Big Bellies" in French, was a misinterpretation of sign language between an Indian guide and French explorers. The Gros Ventre spoke an Algonquian language similar to Arapaho after the division; they identified as ''A'aninin'', meaning ″White Clay people″. The Arapaho often viewed the Gros Ventre as inferior and referred to them as ''Hitúnĕna'' or ''Hitouuteen'', meaning "beggars".

Expansion on the plains

Once established, the Arapaho began to expand on the plains through trade, warfare, and alliances with other plains tribes. Around 1811, the Arapaho made an alliance with the Cheyenne (''Hítesíínoʼ'' – 'scarred one'). Their strong alliance with the Cheyenne allowed the Arapaho to greatly expand their hunting territory. By 1826, the Lakota, Dakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho pushed theKiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

(''Niiciiheihiinennoʼ''; Kiowa tribe: ''Niiciiheihiiteen'') and invading Comanche to the south. Conflict with the allied Comanche and Kiowa ended in 1840 when the two large tribes made peace with the Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne and became their allies.

Chief Little Raven was the most notable Arapaho chief; he helped mediate peace among the nomadic southern plains tribes and would retain his reputation as a peace chief throughout the Indian Wars and reservation period. The alliance with the Comanche and Kiowa made the most southern Arapaho bands powerful enough to enter the Llano Estacado in the Texas Panhandle. One band of Southern Arapaho became so closely allied with the Comanche that they were absorbed into the tribe, adopted the Comanche language, and became a band of Comanche known as the ''Saria Tʉhka (Sata Teichas)'' 'dog-eaters'.

Along the upper Missouri River, the Arapaho actively traded with the farming villages of the Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

, ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Mandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still re ...

, and Hidatsa

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a parent ...

, trading meat and hides for corn, squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

, and beans. The Arikara referred to the Arapaho as the "Colored Stone Village (People)", possibly because gemstones from the Southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

were among the trade items. The Hidatsa called them ''E-tah-leh'' or ''Ita-Iddi'' ('bison-path people'), referring to their hunting of bison.

Conflict with Euro-American traders and explorers was limited at the time. The Arapaho freely entered various trading posts and trade fairs to exchange mostly bison hides and beaver furs for European goods such as firearms. The Arapaho frequently encountered fur traders in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, and the headwaters of the Platte and Arkansas. They became well-known traders on the plains and bordering Rocky Mountains. The name ''Arapaho'' may have been derived from the Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

word ''Tirapihu'' (or ''Larapihu''), meaning "he buys or trades" or "traders". The Arapaho were a prominent trading group in the Great Plains region. The term may also have come from European-American traders referring to them by their Crow (Apsáalooke aliláau) name of ''Alappahoʼ'', which meant 'people with many tattoos'. By custom the Arapaho tattooed small circles on their bodies. The name Arapaho became widespread among the white traders.

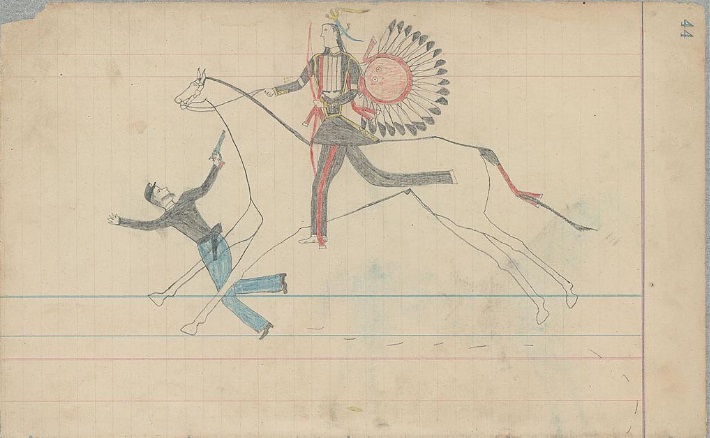

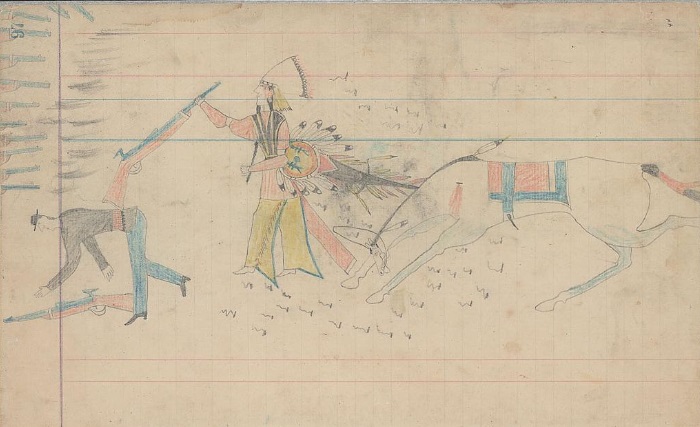

Enemies and warrior culture

A large part of Arapaho society was based around the warrior. Most young men sought this role. After adopting use of the horse, the Arapaho quickly became master horsemen and highly skilled at fighting on horseback. Warriors had larger roles than combat in the society. They were expected to keep peace among the camps, provide food and wealth for their families, and guard the camps from attacks.

Like other plains Indians, including their Cheyenne allies, the Arapaho have a number of distinct military societies. Each of the eight Arapaho military societies had their own unique initiation rites, pre- and post- battle ceremonies and songs, regalia, and style of combat. Unlike their Cheyenne, Lakota, and Dakota allies, the Arapaho military societies were age based. Each age level had its own society for prestigious or promising warriors of the matching age. As the warriors aged, they may graduate to the next society.

Warriors often painted their face and bodies with war paint, as well as their horses, for spiritual empowerment. Each warrior created a unique design for the war paint which they often wore into battle. Feathers from birds, particularly eagle feathers, were also worn in battle as symbols of prestige and for reasons similar to war paint. Before setting out for war, the warriors organized into war parties. War parties were made up of individual warriors and a selected war chief. The title of war chief must be earned through a specific number of acts of bravery in battle known as

A large part of Arapaho society was based around the warrior. Most young men sought this role. After adopting use of the horse, the Arapaho quickly became master horsemen and highly skilled at fighting on horseback. Warriors had larger roles than combat in the society. They were expected to keep peace among the camps, provide food and wealth for their families, and guard the camps from attacks.

Like other plains Indians, including their Cheyenne allies, the Arapaho have a number of distinct military societies. Each of the eight Arapaho military societies had their own unique initiation rites, pre- and post- battle ceremonies and songs, regalia, and style of combat. Unlike their Cheyenne, Lakota, and Dakota allies, the Arapaho military societies were age based. Each age level had its own society for prestigious or promising warriors of the matching age. As the warriors aged, they may graduate to the next society.

Warriors often painted their face and bodies with war paint, as well as their horses, for spiritual empowerment. Each warrior created a unique design for the war paint which they often wore into battle. Feathers from birds, particularly eagle feathers, were also worn in battle as symbols of prestige and for reasons similar to war paint. Before setting out for war, the warriors organized into war parties. War parties were made up of individual warriors and a selected war chief. The title of war chief must be earned through a specific number of acts of bravery in battle known as counting coup

Among the Plains Indians of North America, counting coup is the warrior tradition of winning prestige against an enemy in battle. It is one of the traditional ways of showing bravery in the face of an enemy and involves intimidating him, and, it ...

. Coups may include stealing horses while undetected, touching a living enemy, or stealing a gun from an enemy's grasp. Arapaho warriors used a variety of weapons, including war-clubs, lances, knives, tomahawks, bows, shotguns, rifles, and pistols. They acquired guns through trade at trading posts or trade fairs, in addition to raiding soldiers or other tribes.

The Arapaho fought with the Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

(''Hooxeihiinenno'' – "wolf people"), Omaha (''Howohoono''), Ho-chunk, Osage (''Wosootiinen'', ''Wosoo3iinen'' or ''Wosoosiinen''), Ponca

The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...

(same as Omaha: ''Howohoono''), and Kaw

Kaw or KAW may refer to:

Mythology

* Kaw (bull), a legendary bull in Meitei mythology

* Johnny Kaw, mythical settler of Kansas, US

* Kaw (character), in ''The Chronicles of Prydain''

People

* Kaw people, a Native American tribe

Places

* Kaw, Fr ...

(''Honoho'') east of their territory. North of Arapaho territory they fought with the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

(''Houunenno''), Blackfoot Confederacy

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bla ...

(''Woo'teenixteet'' or ''Woo'teenixtee3i – ″people wearing black-feet″), Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

(''Hitouunenno'', Gros Ventre tribe: ''Hitouuteen''), Flathead (''Kookee'ei3i''), Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

(''Koonoonii3i'' – ″people whose jaws break in pieces″), Iron Confederacy (Nehiyaw-Pwat) (''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

(''Nihooneihteenootineihino'' - "yellow-footed Sioux"), Plains/Woods Cree (''Nooku(h)nenno''; Plains Cree tribe: ''Nookuho'' - "rabbit people"), Saulteaux (Plains Ojibwa) and Nakoda (Stoney)). To the west they fought with eastern Shoshone (''Sosoni'ii''; Shoshone tribe: ''Sosoni'iiteen'') and the Ute (''Wo'(o)teenehi3i'' - ″cut throats″; Ute tribe: ''Wo'(o)teennehhiiteen''). South of their territory they occasionally fought with the Navajo (''Coohoh'oukutoo3i'' – ″those who tie their hair in back of the head or in bunches″), Apache (''Coo3o'' – "enemy" or ''Teebe'eisi3i'' – "they have their hair cut straight, hanging straight down", ''Ti'iihiinen'' – "killdeer people" refers especially to Jicarilla Apache) and various Pueblo people

The Puebloans or Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Currently 100 pueblos are actively inhabited, among which Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Z ...

s (''Cooh'ookutoo3i'' – "they tie their hair in a bundle").

The Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

(''Hitesiino''), Sioux (''Nootineihino''), Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

(''Niiciiheihiinenno'' – ″river people″ or ''Koh'ówuunénno – ″creek people″; Kiowa tribe: ''Niiciiheihiiteen'' or ''Koh'ówuunteen''), Plains Apache (''3oxooheinen'' – "pounder people"), and Comanche (''Coo3o'' – sg. and pl., means: "enemy", like Apache) were enemies of the Arapaho initially but became their allies. Together with their allies, the Arapaho also fought with invading US soldiers, miners, and settlers across Arapaho territory and the territory of their allies.

Sand Creek Massacre

Events Leading to the Sand Creek Massacre

Several skirmishes had ignited hatred from white settlers that lived in the area, and left Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes in constant fear of being attacked by American troops. For example, on April 12, 1864, a rancher brought troops to attack a group of 15 warriors who had asked for reward from bringing his mules back to him. The warriors acted in self-defense and sent the troops running. Word got back to Colonel John Chivington, and they had told him the Indians shot first. He also heard there were 175 cattle head stolen from the government. Chivington "ordered troops to find and 'chastise' the 'Indians'." Soldiers burned villages and sought out to kill Indians, the violence escalating months before the Sand Creek Massacre. In an effort to establish peace, John Evans attempted to extend an offer of refuge and protection to "friendly" Indians. However, these efforts were trampled by General Curtis' military expedition against tribes between the Platte and Arkansas Rivers. By this point, both Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes thought that an all out war of extermination was about to rage against them, so they quickly fled, and Curtis and his men never met them.Sand Creek Massacre

In November 1864, the Colorado militia, led by Colonel

In November 1864, the Colorado militia, led by Colonel John Chivington

John Milton Chivington (January 27, 1821 – October 4, 1894) was an American Methodism, Methodist pastor and Freemasonry, Mason who served as a colonel (United States), colonel in the United States Volunteers during the New Mexico Campaign ...

, massacred a small village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in the Sand Creek massacre. According to a historical narrative on the event titled "Chief Left Hand", by Margaret Coel, there were several events that led to the Colorado militia's attack on the village. Governor Evans desired to hold title to the resource-rich Denver-Boulder area. The government trust officials avoided Chief Left Hand, a linguistically gifted Southern Arapaho chief, when executing their treaty that transferred the title of the area away from Indian Trust. The local cavalry was stretched thin by the demands of the Civil War while Indian warriors, acting independently of Chief Left Hand, raided their supply lines. A group of Arapaho and Cheyenne elders with women and children had been denied their traditional wintering grounds in Boulder by the cavalry and were ordered to come to Fort Lyon for food and protection or be considered hostile.

On arrival at Lyon, Chief Left Hand and his followers were accused of violence by Colonel Chivington. Chief Left Hand and his people got the message that only those Indians that reported to Fort Lyon would be considered peaceful and all others would be considered hostile and ordered killed. Confused, Chief Left Hand and his followers turned away and traveled a safe distance away from the fort to camp. A traitor gave Colonel Chivington directions to the camp. He and his battalion stalked and attacked the camp early the next morning. Rather than heroic, Colonel Chivington's efforts were considered a gross embarrassment to the Cavalry since he attacked peaceful elders, women, and children. As a result of his war efforts, instead of receiving the promotion to which he aspired, he was relieved of his duties.

Eugene Ridgely, a Cheyenne–Northern Arapaho artist, is credited with bringing to light the fact that Arapahos were among the victims of the massacre. His children, Gail Ridgely, Benjamin Ridgley, and Eugene "Snowball" Ridgely, were instrumental in having the massacre site designated as a National Historic Site. In 1999, Benjamin and Gail Ridgley organized a group of Northern Arapaho runners to run from Limon, Colorado

Limon is a statutory town that is the most populous municipality in Lincoln County, Colorado, United States. The population was 1,880 at the 2010 United States Census. Limon has been called the "Hub City" of Eastern Colorado because Interst ...

, to Ethete, Wyoming

Ethete ( arp, Koonoutoseii') is a census-designated place (CDP) in Fremont County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 1,553 at the 2010 census. The town is located on the Wind River Indian Reservation. It grew up around the Episcopal St. ...

, in memory of their ancestors who were forced to run for their lives after being attacked and pursued by Colonel Chivington and his battalion. Their efforts will be recognized and remembered by the "Sand Creek Massacre" signs that appear along the roadways from Limon to Casper, Wyoming, and then to Ethete.

Why the Sand Creek Massacre Occurred

The violence that ensued was deeply rooted in the Indian-hating by American settlers in the area. Their perception was that "their nascent settlements were indeed surrounded by Indians", and their inexperience in dealing with Indians was what sparked the Sand Creek Massacre.Indian Wars on the Southern Plains

The events at Sand Creek sparked outrage among the Arapaho and Cheyenne, resulting in three decades of war between them and the United States. Much of the hostilities took place in Colorado, leading to many of the events being referred to as part of the so-called

The events at Sand Creek sparked outrage among the Arapaho and Cheyenne, resulting in three decades of war between them and the United States. Much of the hostilities took place in Colorado, leading to many of the events being referred to as part of the so-called Colorado War

The Colorado War was an Indian War fought in 1864 and 1865 between the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and allied Brulé and Oglala Sioux (or Lakota) peoples versus the U.S. army, Colorado militia, and white settlers in Colorado Territory and ad ...

. Battles and hostilities elsewhere on the southern plains such as in Kansas and Texas are often included as part of the "Comanche Wars

The Comanche Wars were a series of armed conflicts fought between Comanche peoples and Spanish, Mexican, and American militaries and civilians in the United States and Mexico from as early as 1706 until at least the mid-1870s. The Comanche were the ...

". During the wars, the Arapaho and Cheyenne allies—the Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache—would participate in some battles alongside them. The Lakota from the north came down into northern Colorado to help the Arapaho and Cheyenne there. The Battle of Julesburg

The Battle of Julesburg took place on January 7, 1865 near Julesburg, Colorado between 1,000 Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota Indians and about 60 soldiers of the U.S. army and 40 to 50 civilians. The Indians defeated the soldiers and over the next ...

resulted from a force of about 1,000 allied Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne (mostly from the Dog Soldiers warrior society), and Lakota from the Brulé

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands (sometimes called "sub-tribes") of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte (in Lakȟóta) —Sicangu Oyate—, ''Sicangu Lakota, o''r "Burnt ...

and Oglala sub-tribes. The point of the raid was retaliation for the events at the Sand Creek Massacre months earlier. The allied Indian forces attacked settlers and US Army forces around the valley of the South Platte River

The South Platte River is one of the two principal tributaries of the Platte River. Flowing through the U.S. states of Colorado and Nebraska, it is itself a major river of the American Midwest and the American Southwest/ Mountain West. It ...

near Julesburg, Colorado

Julesburg is the statutory town that is the county seat and the most populous municipality of Sedgwick County, Colorado, United States. The population was 1,225 at the 2010 United States Census.

It is close to the Nebraska border.

History

T ...

. The battle was a decisive Indian victory, resulting in 14 soldiers and four civilians dead and probably no Indian casualties. A force of around 3,000 Southern Arapaho, Northern Cheyenne, and Lakota attacked soldiers and civilians at a bridge crossing the North Platte River

The North Platte River is a major tributary of the Platte River and is approximately long, counting its many curves.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed March 21, 2011 In a ...

, known as the Battle of Platte Bridge

The Battle of Platte Bridge, also called the Battle of Platte Bridge Station, on July 26, 1865, was the culmination of a summer offensive by the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne Indians against the United States army. In May and June the Indians raid ...

. The battle was another victory for the Indians, with 29 soldiers killed and at least eight Indian casualties. Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apaches seeking peace were offered to sign the Medicine Lodge Treaty

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the overall name for three treaties signed near Medicine Lodge, Kansas, between the Federal government of the United States and southern Plains Indian tribes in October 1867, intended to bring peace to the area by re ...

in October 1867. The treaty allotted the Southern Arapaho a reservation with the Southern Cheyenne between the Arkansas and Cimarron rivers in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).May, Jon DLittle Raven (ca. 1810–1889).

Oklahoma Historical Society's ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture''. (accessed 2 July 2012) Among those that signed the treaty was Chief Little Raven. Those that did not sign the treaty were called "hostile" and were continually pursued by the US Army and their Indian scouts. The last major battle between the Arapaho and the US on the southern plains was the

Battle of Summit Springs

The Battle of Summit Springs, on July 11, 1869, was an armed conflict between elements of the United States Army under the command of Colonel Eugene A. Carr and a group of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers led by Tall Bull, who was killed during the engagem ...

in northernmost Colorado. The battle involved a force of around 450 Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota warriors and 244 US soldiers and around 50 Pawnee scouts under Frank North. The most prominent Indian leader at the battle was Tall Bull, a leader of the Dog Soldiers warrior society of the Cheyenne. The battle was a US victory with around 35 warriors killed (including Tall Bull) and a further 17 captured. The soldiers suffered only a single casualty. The death of Tall Bull was a major loss for the Dog Soldiers.

Powder River Expedition

After the Sand Creek Massacre and a number of other skirmishes, the Northern Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota moved many of their bands to the remote Powder River country in Wyoming and southern Montana. Along the way, they participated in theBattle of Mud Springs

The Battle of Mud Springs took place February 4–6, 1865, in Nebraska between the U.S. army and warriors of the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. The battle was inconclusive, although the Indians succeeded in capturing some Army horses ...

, a minor incident in the Nebraska Panhandle involving a force of between 500 and 1,000 Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota warriors and 230 US soldiers. The battle resulted in the capture of some army horses and a herd of several hundred cattle with a single US casualty. An attempt was made by the army to recapture their stolen livestock and attack the Indians, which resulted in the Battle of Rush Creek. The battle was inconclusive, resulting in only one Indian casualty and three US soldiers dead (with a further eight wounded). Lt. Col. William O. Collins, commander of the army forces, stated that pursuing the Indian forces any further through the dry Sand Hills area would be "injudicious and useless". Once in the area of the Powder River, the Arapaho noticed an increase in travelers moving along the established Bozeman trail, which led to the Montana goldfields. Settlers and miners traveling on the Bozeman Trail through the Powder River country were viewed as threats by the Indians as they were numerous and were often violent towards encountered Indians and competed for food along the trail.

Hostilities in the Powder River area led Major General Grenville M. Dodge to order the Powder River Expedition

:''This event should not be confused with the Big Horn Expedition during the Black Hills War.''

The Powder River Expedition of 1865 also known as the Powder River War or Powder River Invasion, was a large and far-flung military operation of the U ...

as a punitive campaign against the Arapaho, Lakota, and Cheyenne. The expedition was inconclusive with neither side gaining a definitive victory. The allied Indian forces mostly evaded the soldiers except for raids on their supplies which left most soldiers desperately under-equipped. The most significant battle was the Battle of the Tongue River

The Battle of the Tongue River, sometimes referred to as the Connor Battle, was an engagement of the Powder River Expedition that occurred on August 29, 1865. In the battle, U.S. soldiers and Indian scouts attacked and destroyed an Arapaho vil ...

where Brigadier General Patrick Edward Connor

Patrick Edward Connor (March 17, 1820Rodgers, 1938, p. 1 – December 17, 1891) was an American soldier who served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He is most notorious for his massacres against Native Americans during th ...

ordered Frank North and his Pawnee Scouts to find a camp of Arapaho Indians under the leadership of Chief Black Bear. Once located, Connor sent in 200 soldiers with two howitzers and 40 Omaha and Winnebago and 30 Pawnee scouts, and marched toward the village that night. Indian warriors acting as scouts for the US Army came from the Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

, Omaha, and Winnebago tribes who were traditional enemies of the Arapaho and their Cheyenne and Lakota allies. With mountain man Jim Bridger

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was known as Old ...

leading the forces, they charged the camp. Most of the Arapaho warriors were gone on a raid against the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

, and the battle was a US victory resulting in 63 Arapaho dead, mostly women and children. The few warriors present at the camp put up a strong defense and covered the women and children as most escaped beyond the reach of the soldiers and Indian scouts. After the battle, the soldiers burned and looted the abandoned tipis. Connor singled out four Winnebago, including chief Little Priest, plus North and 15 Pawnee for bravery. The Pawnee made off with 500 horses from the camp's herd as payback for previous raids by the Arapaho. The Arapaho were not intimidated by the attack and launched a counterattack resulting in the Sawyers Fight where Arapaho warriors attacked a group of surveyors, resulting in three dead and no Arapaho losses.

Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War was a war fought between soldiers of the United States and the allied

Red Cloud's War was a war fought between soldiers of the United States and the allied Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

* Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

* Lakota, Iowa

* Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

* La ...

, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho from 1866 to 1868. The war was named after the prominent Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

who led many followers into battle with the invading soldiers. The war was a response to the large number of miners and settlers passing through the Bozeman Trail

The Bozeman Trail was an overland route in the western United States, connecting the gold rush territory of southern Montana to the Oregon Trail in eastern Wyoming. Its most important period was from 1863–68. Despite the fact that the major pa ...

, which was the fastest and easiest trail from Fort Laramie

Fort Laramie (founded as Fort William and known for a while as Fort John) was a significant 19th-century trading-post, diplomatic site, and military installation located at the confluence of the Laramie and the North Platte rivers. They joined ...

to the Montana goldfields. The Bozeman Trail passed right through the Powder River Country

The Powder River Country is the Powder River Basin area of the Great Plains in northeastern Wyoming, United States. The area is loosely defined as that between the Bighorn Mountains and the Black Hills, in the upper drainage areas of the Powder, ...

which was near the center of Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota, and Dakota territory in Wyoming and southern Montana. The large number of miners and settlers competed directly with the Indians for resources such as food along the trail.

The most significant battle during Red Cloud's War was the Fetterman Fight

The Fetterman Fight, also known as the Fetterman Massacre or the Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands or the Battle of a Hundred Slain, was a battle during Red Cloud's War on December 21, 1866, between a confederation of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and ...

, also known as Battle of The Hundred in the Hand to the Indian forces fought on December 21, 1866. The Battle involved Capt. William J. Fetterman who led a force of 79 soldiers and two civilians after a group of 10 Indian decoys planning on luring Fetterman's forces into an ambush. The 10 decoys consisted of two Arapaho, two Cheyenne, and six Lakota. Fetterman was well known for his boastful nature and his inexperience fighting Indian warriors and despite orders to not pursue the decoys did so anyway. Jim Bridger

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was known as Old ...

, famous Mountain Man and guide to the soldiers stationed at Fort Laramie, commented on how the soldiers "don't know anything about fighting Indians". After about a half-mile pursuit, the decoys signaled the hidden warriors to ambush Fetterman and his forces. Warriors from both sides of the trail charged Fetterman and forced them into nearby rocks where the battle soon became hand-to-hand combat, giving the Indians the upper hand due to their skill in fighting with handheld weapons such as tomahawks and war clubs. The Indian forces killed all of Fetterman's infantry, as well as the following cavalry, with a total of 81 killed. The battle was the greatest military defeat by the US on the Great Plains until the Battle of the Little Bighorn 10 years later. Red Cloud's War ended in a victory for the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Lakota, and Dakota. The Treaty of Fort Laramie guaranteed legal control of the Powder River country to the Indians.

Great Sioux War of 1876–77

The Great Sioux War of 1876–77, also known as the Black Hills War or Great Cheyenne War, was a major conflict that was fought between the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho alliance and the US Army. The war was started after miners and settlers traveled into the

The Great Sioux War of 1876–77, also known as the Black Hills War or Great Cheyenne War, was a major conflict that was fought between the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho alliance and the US Army. The war was started after miners and settlers traveled into the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

area and found gold, resulting in increased numbers of non-Indians illegally entering designated Indian lands. A large part of Cheyenne and Arapaho territory and most of Sioux territory known as the Great Sioux Reservation

The Great Sioux Reservation initially set aside land west of the Missouri River in South Dakota and Nebraska for the use of the Lakota Sioux, who had dominated this territory. The reservation was established in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 ...

was guaranteed legally to the tribes by the Treaty of Fort Laramie after they defeated the US during Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War or the Powder River War) was an armed conflict between an alliance of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho peoples against the United States that took place in the Wyoming and Mo ...

in 1868. The Black Hills in particular are viewed as sacred to the Lakota and Dakota peoples, and the presence of settlers illegally occupying the area caused great unrest within the tribes. Instead of evicting the settlers, the US Army broke the treaty and invaded Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho territory in order to protect American settlers and put the allied tribes on smaller reservations or wiped them out.

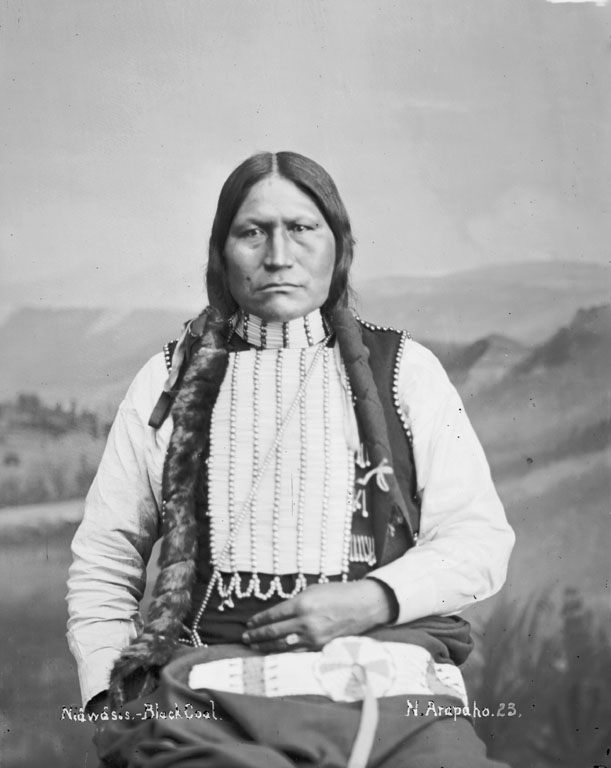

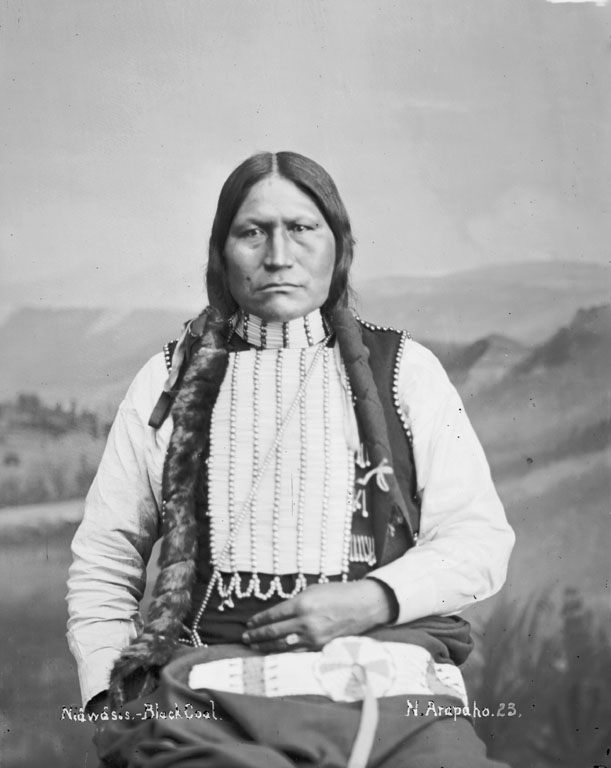

After Red Cloud's War, many Northern Arapaho moved to the Red Cloud Agency in Dakota Territory and lived among the Lakota, as well as many Cheyenne. Among the most influential and respected Arapaho chiefs living on the Agency was Chief Black Coal (Northern Arapaho)

Wo’óoseinee’, known commonly as Black Coal, (c.1840-1893) was a prominent leader of the Northern Arapaho people during the latter half of the 19th Century. Serving as an intermediary between the Northern Arapaho and the United States, he help ...

, who gained prominence as a warrior and leader against white settlers in the Powder River country. Other important Arapaho chiefs living in the area included Medicine Man, Chief Black Bear, Sorrel Horse, Little Shield, Sharp Nose, Little Wolf, Plenty Bear, and Friday

Friday is the day of the week between Thursday and Saturday. In countries that adopt the traditional "Sunday-first" convention, it is the sixth day of the week. In countries adopting the ISO-defined "Monday-first" convention, it is the fifth d ...

. The Arapaho chief Friday was well regarded for his intelligence and served as an interpreter between the tribe and the Americans. Black Coal guaranteed to the Americans that he and his people would remain peaceful during the tense times when the settlers were illegally entering Indian land in hopes of securing recognized territory of their own in Wyoming. Many of the warriors and families that disagreed with Black Coal's ideals drifted southward to join up with the southern division of Arapahos. Many Arapaho, particularly those in Chief Medicine Man's band, did not wish to reside among the Sioux "for fear of mixing themselves up with other tribes". Their peaceful stance and willingness to help American soldiers strained once strong relations between them and the Lakota and Cheyenne, who took an aggressive stance and fled the reservation. Attitudes towards the Arapaho from the "hostile" Lakota and Cheyenne were similar to the attitudes they had towards members of their own tribes which took similar peaceful stances and remained as "reservation Indians". Despite their unwillingness to take up the warpath, the Arapaho were unwilling to cede their territory, particularly the Black Hills area to which they have a strong spiritual attachment similar to the Lakota.

During this time of great unrest, the tribe found itself deteriorating in leadership with many chiefs holding little sway among their bands. In order to regain strength as leaders and further negotiations for land in Wyoming, many chiefs and their warriors enlisted as army scouts for the United States and campaigned against their allies. Chief Sharp Nose, who was considered as influential and equal to Black Coal, was noted as "the inspiration of the battlefield ... He handled men with rare judgment and coolness, and was as modest as he was brave". Despite their overall stance as allies for the Americans, a handful of Arapaho warriors fought against the United States in key battles during the war.

Like in previous wars, the US recruited Indian warriors from tribes that were enemies with the Arapaho–Cheyenne–Lakota–Dakota alliance to act as Indian scouts, most notably from the Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

, Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

, and Shoshone. Unlike previous conflicts involving the Lakota–Dakota–Cheyenne–Arapaho alliance and the United States, the Great Sioux War ended in a victory for the United States. The bison herds which were the center of life for the Indians were considerably smaller due to government-supported whole-scale slaughter in order to prevent collisions with railroads, conflict with ranch cattle, and to force nomadic plains Indians to adopt reservation life living off government handouts. Decreased resources and starvation was the major reason for the surrendering of individual Indian bands and the end of the Great Sioux War.

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

The most significant battle of the war was the

The most significant battle of the war was the Battle of The Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

on June 25–26, 1876. The battle was fought between warriors from the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho (as well as individual Dakota warriors) and the 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Irish air " Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated in some of the largest ba ...

of the US Army. The battle was fought along the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana. The soldiers attempted to ambush the large camp of Indians along the river bottom despite the warnings from the Crow Scouts who knew that Custer severely underestimated the number of warriors in the camp. The US Seventh Cavalry, including the Custer Battalion, a force of 700 men led by George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

, suffered a severe defeat. Five of the Seventh Cavalry's companies were annihilated. The total US casualty count, including scouts, was 268 dead including Custer and 55 injured. Only five Arapaho were present at the battle and their presence was by chance. The Arapaho present were four Northern Arapaho warriors named Yellow Eagle, Yellow Fly, Left Hand, and Water Man. The fifth Arapaho was a Southern Arapaho named Well-Knowing One (Sage) but also known as Green Grass. The five Arapaho set out as a war party from near Fort Robinson to raid the Shoshone, but by chance came across a small party of young Sioux warriors. The Sioux thought that the Arapaho were United States Army Indian Scouts

Native Americans have made up an integral part of U.S. military conflicts since America's beginning. Colonists recruited Indian allies during such instances as the Pequot War from 1634–1638, the Revolutionary War, as well as in War of 1812. ...

and invited them back to their camp along the Little Bighorn River, where they were captured and had their guns taken from them. The Lakota and Dakota threatened to kill the Arapaho, but the Cheyenne chief Two Moons

Two Moons (1847–1917), or ''Ishaynishus'' (Cheyenne: ''Éše'he Ôhnéšesêstse''), was one of the Cheyenne chiefs who took part in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and other battles against the United States Army.

Life

Two Moons was the son o ...

recognized the men as Arapaho and ordered their release. The next day was the battle and, despite being viewed with suspicion, the five Arapaho actively fought in the battle. Water Man wore a large eagle feather headdress

Headgear, headwear, or headdress is the name given to any element of clothing which is worn on one's head, including hats, helmets, turbans and many other types. Headgear is worn for many purposes, including protection against the elements, d ...

, a white shirt, beaded leggings, a breechcloth, and painted his face red and yellow during the battle. Water Man claimed killing one soldier while charging up the steep river banks but did not take his scalp because most Arapaho refused to take a scalp from someone with short hair. Water Man claimed to have watched Custer die.

The Arapaho warrior Left Hand accidentally killed a Lakota warrior that he mistook for an Arikara scout, and despite further anger from the Lakota, left the battle alive along with the other four Arapaho. After the battle, the five Arapaho quietly slipped away and headed back to the Fort Robinson area.

Culture

Creation myth

The creation myth of the Arapaho people shows a connection with theAlgonquian people

The Algonquian are one of the most populous and widespread North American native language groups. Historically, the peoples were prominent along the Atlantic Coast and into the interior along the Saint Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes. T ...

. Both cultures have an "earth-diver creation myth". The Arapaho myth begins with a being called Flat Pipe who exists alone upon the water. The Great Spirit suggests to Flat Pipe that he create creatures to build a world. He first conceives of ducks and other water birds who dive beneath the surface of the water but are not able to find land. With guidance from the Great Spirit, Flat Pipe creates a turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked t ...

who can live on both land or in the water. The Turtle dives and returns, spitting out a piece of land that grows into the earth. Flat Pipe then goes about creating men, women, and animals to populate the earth. The turtle is common to many "earth-diver" creation myths.

This myth is an example of "creation by thought". Flat Pipe creates the creatures by thinking of them.

Gender and division of labor

Traditionally, men are responsible for hunting.Mary Inez Hilger, ''Arapaho Child Life and Its Cultural Background'' (1952) After horses were introduced, buffalo became the main food source—the meat, organs, and the blood all being consumed. Blood was drunk or made into pudding.The Arapaho Project: Food/ref> Women (and ''haxu'xan'' ( Two Spirits)) are traditionally in charge of food preparation and dressing hides to make clothing and bedding, saddles, and housing materials.The Arapaho Project: Clothes

/ref> The Arapaho have historically had social and spiritual roles for those who are known in contemporary Native cultures as

Two Spirit

Two-spirit (also two spirit, 2S or, occasionally, twospirited) is a modern, , umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to describe Native people in their communities who fulfill a traditional third-gender (or other gender-variant ...

or third gender

Third gender is a concept in which individuals are categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither man nor woman. It is also a social category present in societies that recognize three or more genders. The term ''third'' is usuall ...

.Alfred Kroeber, ''The Arapaho'' (1902)Sabine Lang, ''Men as Women, Women as Men'' , 2010) Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber (June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the first ...

wrote about male-bodied individuals who lived as women, the ''haxu'xan'', who he says were believed to have "the natural desire to become women, and as they grew up gradually became women" (and could marry men); he further stated that the Arapaho believed that the ''haxu'xans gender was a supernatural gift from birds or other animals, that they had miraculous powers, and they were also noted for their inventiveness, such as making the first intoxicant

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical, psychoactive agent or psychotropic drug is a chemical substance, that changes functions of the nervous system, and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition or behavior.

Th ...

from rainwater.

Clothing

On the Plains, women (and ''haxu'xan'') historically wore moccasins, leggings, and ankle-length buckskin-fringed dresses, ornamented with porcupine quills, paint, elk teeth, and beads. Men have also worn moccasins, leggings, buckskin breechclothes (drawn between the legs, tied around the waist), and sometimes shirts; warriors have often worn necklaces. Many of these items are still part of contemporary dress for both casual and formal wear, or as regalia.Economic development

In July 2005, Northern Arapahos won a contentious court battle with the State of Wyoming to get into thegambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three el ...

or casino industry. The 10th Circuit Court ruled that the State of Wyoming was acting in bad faith when it would not negotiate with the Arapahos for gaming. The Northern Arapaho Tribe opened the first casinos in Wyoming. Presently, the Arapaho Tribe owns and operates high-stakes, Class III gaming at the Wind River Casino, the Little Wind Casino, and the 789 Smoke Shop and Casino. In 2012, The Wind River Hotel, which is attached to the Wind River Casino, features a cultural room called the Northern Arapaho Experience. They are regulated by a Gaming Commission composed of three tribal members.

Meanwhile, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes operate four casinos in Oklahoma: the Lucky Star Casino in Clinton, the Lucky Star Casino in Watonga, the Feather Warrior Casino in Canton, and the newest casino which opened in 2018, the Lucky Star Casino in Hammon.Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma.2007 (retrieved February 7, 2009)

Notable Arapahos

* Margaret Behan (born 1948), Arapaho-Cheyenne spiritual elder *Sherman Coolidge

Sherman Coolidge (February 22, 1862January 24, 1932), an Episcopal Church (United States), Episcopal Church priest and educator, helped found and lead the Society of American Indians (1911–1923). That first national American Indian rights organiz ...

(Runs-on-Top) (1862–1932), Episcopal minister and educator in the Wind River community who was a founding member of the Society of American Indians

The Society of American Indians (1911–1923) was the first national American Indian rights organization run by and for American Indians. The Society pioneered twentieth century Pan-Indianism, the movement promoting unity among American Indians ...

.

* Mirac Creepingbear

Mirac Creepingbear was a Kiowa / Pawnee / Arapaho painter from Oklahoma who played a pivotal role in mid-20th century Native American art.

Background

Creepingbear was born in Lawton, Oklahoma, on 8 September 8, 1947, the son of Rita Littlechie ...

(1947–1990), Arapaho–Kiowa painter

* Viola Hatch

Viola Hatch (February 12, 1930 – April 22, 2019) was a Native American activist, founding member of the National Indian Youth Council, and former Tribal Chair of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes. She successfully sued the Canton, Oklahoma schools ...

(1930-2019), Arapaho activist

* Juanita L. Learned (1930-1996), first woman chair of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma

* Chief Little Raven (c. 1810–1889), negotiated peace between the Southern Arapaho and Cheyenne and the Comanche, Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

, and Plains Apache. He secured rights to the Cheyenne–Arapaho Reservation in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

.May, Jon DLittle Raven (c. 1810–1889).

Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved February 7, 2009) *

Chief Niwot

Chief Niwot ( Hinóno'eitíít/Arapaho: Nowoo3 ɔ'wɔːθ or Left Hand(-ed) (c. 1825–1864) was a Southern Arapaho chief, diplomat, and interpreter who negotiated for peace between white settlers and the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes during the P ...

(c. 1825 – 1864), led a band in Northern Colorado and died from wounds sustained during the Sand Creek Massacre.

* Pretty Nose (c. 1851 – after 1952), a war chief who participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

* Carl Sweezy (1881–1953), early professional Native American easel artist

See also

*Arapaho language

The Arapaho (Arapahoe) language () is one of the Plains Algonquian languages, closely related to Gros Ventre and other Arapahoan languages. It is spoken by the Arapaho of Wyoming and Oklahoma. Speakers of Arapaho primarily live on the Wind Ri ...

* Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes

* Wind River Indian Reservation

The Wind River Indian Reservation, in the west-central portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming, is shared by two Native American tribes, the Eastern Shoshone ( shh, Gweechoon Deka, ''meaning: "buffalo eaters"'') and the Northern Arapaho ( arp, ...

Citations

General references

* Fowler, Loretta. ''Arapahoe Politics, 1851–1978: Symbols in Crises of Authority''. University of Nebraska Press, 1982. . * McDermott, John D. ''Circle of Fire: The Indian War of 1865''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. * Pritzker, Barry M. ''A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. . * Waldman, Carl. ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes''. New York: Checkmark Books, 2006. .Further reading

* *External links

The Northern Arapaho Tribe

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090613061905/http://www.arapahochs.com/ Arapaho Charter High School

Arapaho artwork

in the collection of the