Antimony(III)-oxide-valentinite-xtal-2004-3D-balls.png on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Antimony is a

Antimony is a member of

Antimony is a member of

The abundance of antimony in the

The abundance of antimony in the

The pentahalides and have

The pentahalides and have

Antimony was frequently described in alchemical manuscripts, including the ''Summa Perfectionis'' of

Antimony was frequently described in alchemical manuscripts, including the ''Summa Perfectionis'' of

O34:D46-G17-F21:D4

The Greek word, στίμμι (stimmi) is used by Attic

Public Health Statement for Antimony

International Antimony Association vzw (i2a

Chemistry in its element podcast

(MP3) from the

Antimony

at ''

CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Antimony

Antimony Mineral data and specimen images

{{Authority control Chemical elements Metalloids Native element minerals Nuclear materials Pnictogens Trigonal minerals Minerals in space group 166 Materials that expand upon freezing Chemical elements with rhombohedral structure

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every ...

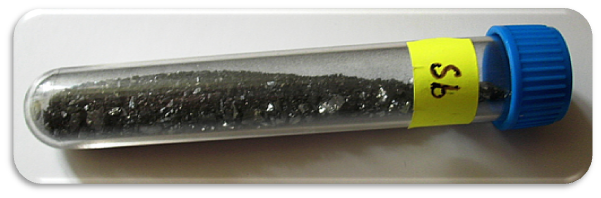

51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral

The sulfide minerals are a class of minerals containing sulfide (S2−) or disulfide (S22−) as the major anion. Some sulfide minerals are economically important as metal ores. The sulfide class also includes the selenides, the tellurides, th ...

stibnite

Stibnite, sometimes called antimonite, is a sulfide mineral with the formula Sb2 S3. This soft grey material crystallizes in an orthorhombic space group. It is the most important source for the metalloid antimony. The name is derived from the ...

(Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient times and were powdered for use as medicine and cosmetics, often known by the Arabic name kohl. The earliest known description of the metal in the West was written in 1540 by Vannoccio Biringuccio

Vannoccio Biringuccio, sometimes spelled Vannocio Biringuccio (c. 1480 – c. 1539), was an Italian metallurgist. He is best known for his manual on metalworking, '' De la pirotechnia'', published posthumously in 1540.

20th Century translation by ...

.

China is the largest producer of antimony and its compounds, with most production coming from the Xikuangshan Mine

Xikuangshan mine () in Lengshuijiang, Hunan, China, contains the world's largest deposit of antimony. It is unique in that there is a large deposit of stibnite (Sb2S3) in a layer of Devonian limestone. There are three mineral beds which are between ...

in Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi ...

. The industrial methods for refining antimony from stibnite are roasting followed by reduction with carbon, or direct reduction of stibnite with iron.

The largest applications for metallic antimony are in alloys with lead and tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

, which have improved properties for solder

Solder (; NA: ) is a fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces after cooling. Metals or alloys suitable ...

s, bullets, and plain bearing

A plain bearing, or more commonly sliding contact bearing and slide bearing (in railroading sometimes called a solid bearing, journal bearing, or friction bearing), is the simplest type of bearing, comprising just a bearing surface and no roll ...

s. It improves the rigidity of lead-alloy plates in lead–acid batteries. Antimony trioxide is a prominent additive for halogen-containing flame retardant

The term flame retardants subsumes a diverse group of chemicals that are added to manufactured materials, such as plastics and textiles, and surface finishes and coatings. Flame retardants are activated by the presence of an ignition source and ...

s. Antimony is used as a dopant

A dopant, also called a doping agent, is a trace of impurity element that is introduced into a chemical material to alter its original electrical or optical properties. The amount of dopant necessary to cause changes is typically very low. When ...

in semiconductor devices.

Characteristics

Properties

Antimony is a member of

Antimony is a member of group 15

A pnictogen ( or ; from grc, πνῑ́γω "to choke" and -gen, "generator") is any of the chemical elements in group 15 of the periodic table. Group 15 is also known as the nitrogen group or nitrogen family. Group 15 consists of the ...

of the periodic table, one of the elements called pnictogen

A pnictogen ( or ; from grc, πνῑ́γω "to choke" and -gen, "generator") is any of the chemical elements in group 15 of the periodic table. Group 15 is also known as the nitrogen group or nitrogen family. Group 15 consists of the el ...

s, and has an electronegativity

Electronegativity, symbolized as , is the tendency for an atom of a given chemical element to attract shared electrons (or electron density) when forming a chemical bond. An atom's electronegativity is affected by both its atomic number and the ...

of 2.05. In accordance with periodic trends, it is more electronegative than tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

or bismuth

Bismuth is a chemical element with the symbol Bi and atomic number 83. It is a post-transition metal and one of the pnictogens, with chemical properties resembling its lighter group 15 siblings arsenic and antimony. Elemental bismuth occurs ...

, and less electronegative than tellurium

Tellurium is a chemical element with the symbol Te and atomic number 52. It is a brittle, mildly toxic, rare, silver-white metalloid. Tellurium is chemically related to selenium and sulfur, all three of which are chalcogens. It is occasionall ...

or arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

. Antimony is stable in air at room temperature, but reacts with oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

if heated to produce antimony trioxide, Sb2O3.

Antimony is a silvery, lustrous gray metalloid with a Mohs scale

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness () is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material.

The scale was introduced in 1812 by th ...

hardness of 3, which is too soft to mark hard objects. Coins of antimony were issued in China's Guizhou

Guizhou (; formerly Kweichow) is a landlocked province in the southwest region of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Guiyang, in the center of the province. Guizhou borders the autonomous region of Guangxi to the ...

province in 1931; durability was poor, and minting was soon discontinued. Antimony is resistant to attack by acids.

Four allotropes

Allotropy or allotropism () is the property of some chemical elements to exist in two or more different forms, in the same physical state, known as allotropes of the elements. Allotropes are different structural modifications of an element: th ...

of antimony are known: a stable metallic form, and three metastable forms (explosive, black, and yellow). Elemental antimony is a brittle

A material is brittle if, when subjected to stress, it fractures with little elastic deformation and without significant plastic deformation. Brittle materials absorb relatively little energy prior to fracture, even those of high strength. Br ...

, silver-white, shiny metalloid. When slowly cooled, molten antimony crystallizes into a trigonal

In crystallography, the hexagonal crystal family is one of the six crystal families, which includes two crystal systems (hexagonal and trigonal) and two lattice systems (hexagonal and rhombohedral). While commonly confused, the trigonal crystal ...

cell, isomorphic with the gray allotrope of arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

. A rare explosive form of antimony

Explosive antimony is an allotrope of the chemical element antimony that is so sensitive to shock that it explodes when scratched or subjected to sudden heating. The allotrope was first described in 1855.

Chemists form the allotrope through elec ...

can be formed from the electrolysis of antimony trichloride

Antimony trichloride is the chemical compound with the formula SbCl3. It is a soft colorless solid with a pungent odor and was known to alchemists as butter of antimony.

Preparation

Antimony trichloride is prepared by reaction of chlorine with an ...

. When scratched with a sharp implement, an exothermic reaction occurs and white fumes are given off as metallic antimony forms; when rubbed with a pestle in a mortar, a strong detonation occurs. Black antimony is formed upon rapid cooling of antimony vapor. It has the same crystal structure as red phosphorus

Elemental phosphorus can exist in several allotropes, the most common of which are white and red solids. Solid violet and black allotropes are also known. Gaseous phosphorus exists as diphosphorus and atomic phosphorus.

White phosphorus

White ...

and black arsenic; it oxidizes in air and may ignite spontaneously. At 100 °C, it gradually transforms into the stable form. The yellow allotrope of antimony is the most unstable; it has been generated only by oxidation of stibine (SbH3) at −90 °C. Above this temperature and in ambient light, this metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability denotes an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball i ...

allotrope transforms into the more stable black allotrope.

Elemental antimony adopts a layered structure (space group

In mathematics, physics and chemistry, a space group is the symmetry group of an object in space, usually in three dimensions. The elements of a space group (its symmetry operations) are the rigid transformations of an object that leave it uncha ...

Rm No. 166) whose layers consist of fused, ruffled, six-membered rings. The nearest and next-nearest neighbors form an irregular octahedral complex, with the three atoms in each double layer slightly closer than the three atoms in the next. This relatively close packing leads to a high density of 6.697 g/cm3, but the weak bonding between the layers leads to the low hardness and brittleness of antimony.

Isotopes

Antimony has two stableisotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers (mass numb ...

s: 121Sb with a natural abundance of 57.36% and 123Sb with a natural abundance of 42.64%. It also has 35 radioisotopes, of which the longest-lived is 125Sb with a half-life

Half-life (symbol ) is the time required for a quantity (of substance) to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo radioactive decay or how long stable at ...

of 2.75 years. In addition, 29 metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability denotes an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball i ...

states have been characterized. The most stable of these is 120m1Sb with a half-life

Half-life (symbol ) is the time required for a quantity (of substance) to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo radioactive decay or how long stable at ...

of 5.76 days. Isotopes that are lighter than the stable 123Sb tend to decay by β+ decay, and those that are heavier tend to decay by β− decay, with some exceptions.

Occurrence

The abundance of antimony in the

The abundance of antimony in the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

's crust is estimated to be 0.2 to 0.5 parts per million

In science and engineering, the parts-per notation is a set of pseudo-units to describe small values of miscellaneous dimensionless quantities, e.g. mole fraction or mass fraction. Since these fractions are quantity-per-quantity measures, th ...

, comparable to thallium

Thallium is a chemical element with the symbol Tl and atomic number 81. It is a gray post-transition metal that is not found free in nature. When isolated, thallium resembles tin, but discolors when exposed to air. Chemists William Crookes an ...

at 0.5 parts per million and silver at 0.07 ppm. Even though this element is not abundant, it is found in more than 100 mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

species. Antimony is sometimes found natively (e.g. on Antimony Peak

Antimony Peak is a steep peak located in southern Kern County, in the San Emigdio Mountains of the Transverse Ranges of California. It is the taller one of two summits with that name in Kern County. The second Antimony Peak is in the Sierra Neva ...

), but more frequently it is found in the sulfide stibnite

Stibnite, sometimes called antimonite, is a sulfide mineral with the formula Sb2 S3. This soft grey material crystallizes in an orthorhombic space group. It is the most important source for the metalloid antimony. The name is derived from the ...

(Sb2S3) which is the predominant ore mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

.

Compounds

Antimony compounds are often classified according to their oxidation state: Sb(III) and Sb(V). The +5oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. C ...

is more stable.

Oxides and hydroxides

Antimony trioxide is formed when antimony is burnt in air. In the gas phase, the molecule of the compound is , but it polymerizes upon condensing.Antimony pentoxide

Antimony pentoxide (molecular formula: Sb2O5) is a chemical compound of antimony and oxygen. It contains antimony in the +5 oxidation state.

Structure

Antimony pentoxide has the same structure as the ''B'' form of niobium pentoxide and can be deri ...

() can be formed only by oxidation with concentrated nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

. Antimony also forms a mixed-valence oxide, antimony tetroxide (), which features both Sb(III) and Sb(V). Unlike oxides of phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

and arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

, these oxides are amphoteric

In chemistry, an amphoteric compound () is a molecule or ion that can react both as an acid and as a base. What exactly this can mean depends on which definitions of acids and bases are being used.

One type of amphoteric species are amphipro ...

, do not form well-defined oxoacid

An oxyacid, oxoacid, or ternary acid is an acid that contains oxygen. Specifically, it is a compound that contains hydrogen, oxygen, and at least one other element, with at least one hydrogen atom bonded to oxygen that can dissociate to produce ...

s, and react with acids to form antimony salts.

Antimonous acid is unknown, but the conjugate base sodium antimonite () forms upon fusing sodium oxide

Sodium oxide is a chemical compound with the formula Na2 O. It is used in ceramics and glasses. It is a white solid but the compound is rarely encountered. Instead "sodium oxide" is used to describe components of various materials such as glass ...

and . Transition metal antimonites are also known. Antimonic acid exists only as the hydrate , forming salts as the antimonate anion . When a solution containing this anion is dehydrated, the precipitate contains mixed oxides.

Many antimony ores are sulfides, including stibnite

Stibnite, sometimes called antimonite, is a sulfide mineral with the formula Sb2 S3. This soft grey material crystallizes in an orthorhombic space group. It is the most important source for the metalloid antimony. The name is derived from the ...

(), pyrargyrite

Pyrargyrite is a sulfosalt mineral consisting of silver sulfantimonite, Ag3SbS3. Known also as dark red silver ore or ruby silver, it is an important source of the metal.

It is closely allied to, and isomorphous with, the corresponding sulfarse ...

(), zinkenite

Zinkenite is a steel-gray metallic sulfosalt mineral composed of lead antimony sulfide Pb9 Sb22 S42. Zinkenite occurs as acicular needle-like crystals.

It was first described in 1826 for an occurrence in the Harz Mountains, Saxony-Anhalt, Germa ...

, jamesonite

Jamesonite is a sulfosalt mineral, a lead, iron, antimony sulfide with formula Pb4FeSb6S14. With the addition of manganese it forms a series with benavidesite.http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/hom/jamesonite.pdf Handbook of Mineralogy It is a ...

, and boulangerite

Boulangerite is an uncommon monoclinic orthorhombic sulfosalt mineral, lead antimony sulfide, formula Pb5Sb4S11. It was named in 1837 in honor of French mining engineer Charles Boulanger (1810–1849),http://www.mindat.org/min-738.html Mindat a ...

. Antimony pentasulfide

Antimony pentasulfide is an inorganic compound of antimony and sulfur, also known as antimony red. It is a nonstoichiometric compound with a variable composition. Its structure is unknown. Commercial samples are usually contaminated with sulfur, w ...

is non-stoichiometric

In chemistry, non-stoichiometric compounds are chemical compounds, almost always solid inorganic compounds, having elemental composition whose proportions cannot be represented by a ratio of small natural numbers (i.e. an empirical formula); m ...

and features antimony in the +3 oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to different atoms were fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. C ...

and S–S bonds. Several thioantimonides are known, such as and .

Halides

Antimony forms two series of halides: and . The trihalides , , , and are all molecular compounds havingtrigonal pyramidal molecular geometry

In chemistry, a trigonal pyramid is a molecular geometry with one atom at the apex and three atoms at the corners of a trigonal base, resembling a tetrahedron (not to be confused with the tetrahedral geometry). When all three atoms at the corne ...

.

The trifluoride is prepared by the reaction of with HF:

: + 6 HF → 2 + 3

It is Lewis acidic and readily accepts fluoride ions to form the complex anions and . Molten is a weak electrical conductor

In physics and electrical engineering, a conductor is an object or type of material that allows the flow of charge (electric current) in one or more directions. Materials made of metal are common electrical conductors. Electric current is gene ...

. The trichloride is prepared by dissolving in hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

:

: + 6 HCl → 2 + 3

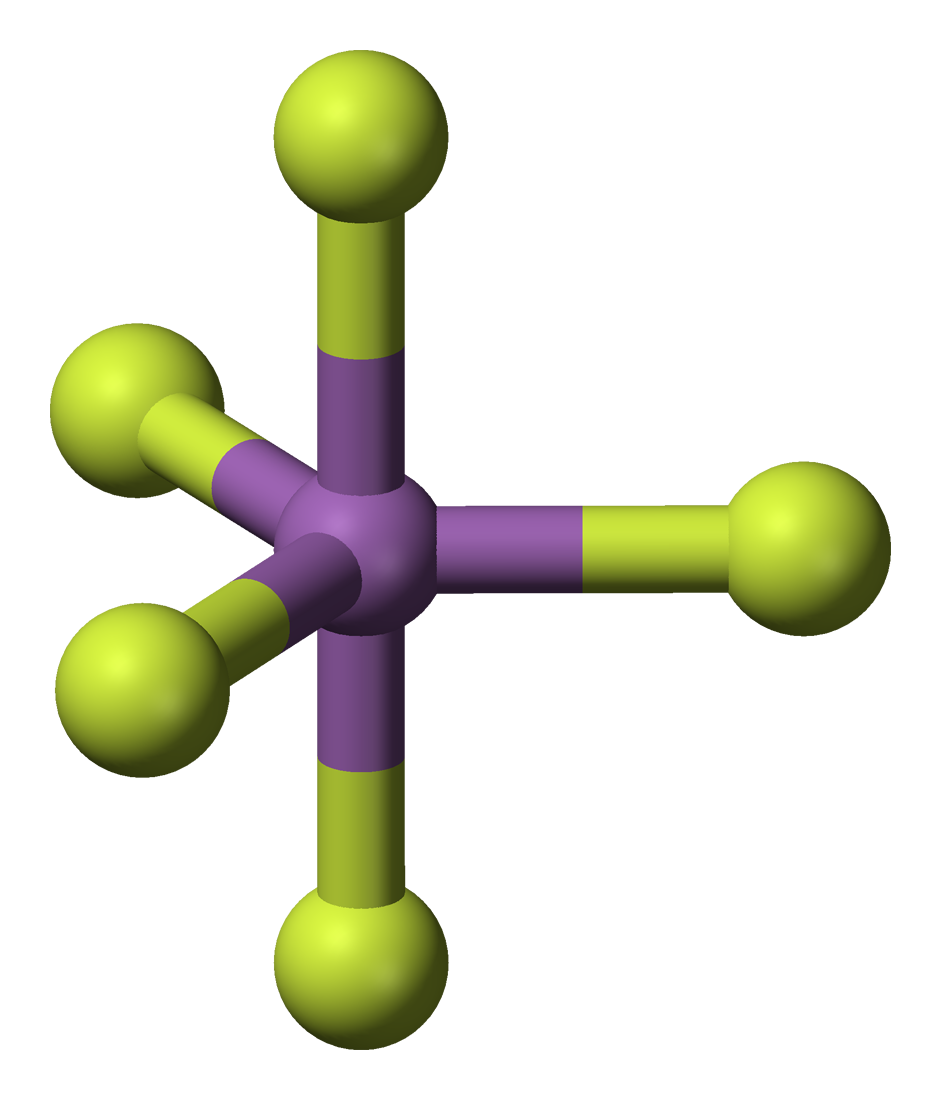

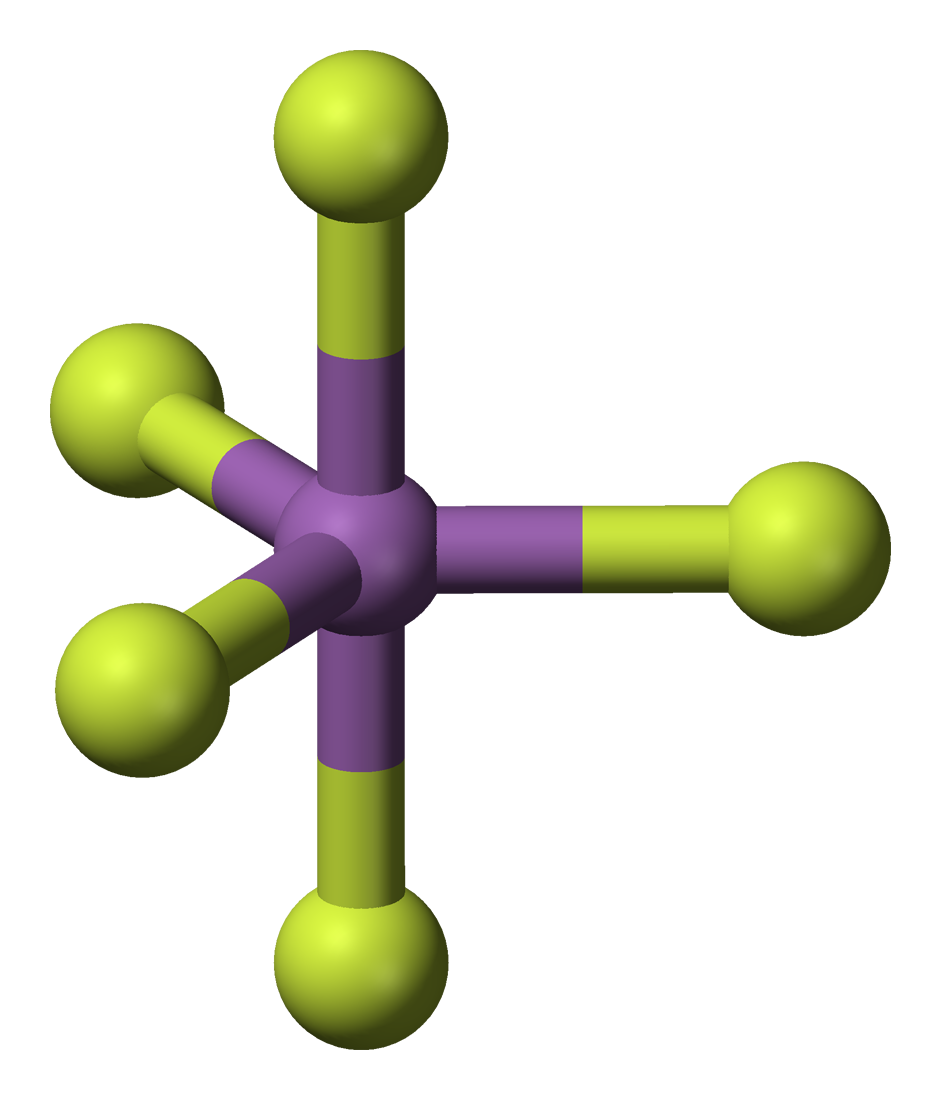

The pentahalides and have

The pentahalides and have trigonal bipyramidal molecular geometry

In chemistry, a trigonal bipyramid formation is a molecular geometry with one atom at the center and 5 more atoms at the corners of a triangular bipyramid. This is one geometry for which the bond angles surrounding the central atom are not iden ...

in the gas phase, but in the liquid phase, is polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + ''-mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

ic, whereas is monomeric. is a powerful Lewis acid used to make the superacid fluoroantimonic acid

Fluoroantimonic acid is a mixture of hydrogen fluoride and antimony pentafluoride, containing various cations and anions (the simplest being and ). This substance is a superacid that can be over a billion times stronger than 100% pure sulfuri ...

("H2SbF7").

Oxyhalides

In chemistry, molecular oxohalides (oxyhalides) are a group of chemical compounds in which both oxygen and halogen atoms are attached to another chemical element A in a single molecule. They have the general formula , where X = fluorine (F), ch ...

are more common for antimony than for arsenic and phosphorus. Antimony trioxide dissolves in concentrated acid to form oxoantimonyl compounds such as SbOCl and .

Antimonides, hydrides, and organoantimony compounds

Compounds in this class generally are described as derivatives of Sb3−. Antimony formsantimonide Antimonides (sometimes called stibnides) are compounds of antimony with more electropositive elements. The antimonide ion is Sb3−.

Reduction of antimony by alkali metals or by other methods leads to alkali metal antimonides of various types. K ...

s with metals, such as indium antimonide

Indium antimonide (InSb) is a crystalline compound made from the elements indium (In) and antimony (Sb). It is a narrow- gap semiconductor material from the III- V group used in infrared detectors, including thermal imaging cameras, FLIR systems ...

(InSb) and silver antimonide (). The alkali metal and zinc antimonides, such as Na3Sb and Zn3Sb2, are more reactive. Treating these antimonides with acid produces the highly unstable gas stibine, :

: + 3 →

Stibine can also be produced by treating salts with hydride reagents such as sodium borohydride

Sodium borohydride, also known as sodium tetrahydridoborate and sodium tetrahydroborate, is an inorganic compound with the formula Na BH4. This white solid, usually encountered as an aqueous basic solution, is a reducing agent that finds applica ...

. Stibine decomposes spontaneously at room temperature. Because stibine has a positive heat of formation

In chemistry and thermodynamics, the standard enthalpy of formation or standard heat of formation of a compound is the change of enthalpy during the formation of 1 mole of the substance from its constituent elements in their reference state, wit ...

, it is thermodynamically unstable and thus antimony does not react with hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

directly.Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. .

Organoantimony compounds Organoantimony chemistry is the chemistry of compounds containing a carbon to antimony (Sb) chemical bond. Relevant oxidation states are Sb(V) and Sb(III). The toxicity of antimony limits practical application in organic chemistry.

Organoantimony ...

are typically prepared by alkylation of antimony halides with Grignard reagents. A large variety of compounds are known with both Sb(III) and Sb(V) centers, including mixed chloro-organic derivatives, anions, and cations. Examples include Sb(C6H5)3 (triphenylstibine

Triphenylstibine is the chemical compound with the formula Sb(C6H5)3. Abbreviated SbPh3, this colourless solid is often considered the prototypical organoantimony compound. It is used as a ligand in coordination chemistry and as a reagent in o ...

), Sb2(C6H5)4 (with an Sb-Sb bond), and cyclic b(C6H5)sub>n. Pentacoordinated organoantimony compounds are common, examples being Sb(C6H5)5 and several related halides.

History

Antimony(III) sulfide

Antimony trisulfide (Sb2S3) is found in nature as the crystalline mineral stibnite and the amorphous red mineral (actually a mineraloid) metastibnite. It is manufactured for use in safety matches, military ammunition, explosives and fireworks. It ...

, Sb2S3, was recognized in predynastic Egypt

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with ...

as an eye cosmetic ( kohl) as early as about 3100 BC, when the cosmetic palette

Cosmetic palettes are archaeological artifacts, originally used in predynastic Egypt to grind and apply ingredients for facial or body cosmetics. The decorative palettes of the late 4th millennium BCE appear to have lost this function and became c ...

was invented.

An artifact, said to be part of a vase, made of antimony dating to about 3000 BC was found at Telloh, Chaldea (part of present-day Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

), and a copper object plated with antimony dating between 2500 BC and 2200 BC has been found in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

. Austen, at a lecture by Herbert Gladstone

Herbert John Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone, (7 January 1854 – 6 March 1930) was a British Liberal politician. The youngest son of William Ewart Gladstone, he was Home Secretary from 1905 to 1910 and Governor-General of the Union of South ...

in 1892, commented that "we only know of antimony at the present day as a highly brittle and crystalline metal, which could hardly be fashioned into a useful vase, and therefore this remarkable 'find' (artifact mentioned above) must represent the lost art of rendering antimony malleable."

The British archaeologist Roger Moorey

Peter Roger Stuart Moorey, (30 May 1937 – 23 December 2004) was a British archaeologist, historian, and academic, specialising in Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. He was Keeper of Antiquities at the Ashmolean Museum of the University of ...

was unconvinced the artifact was indeed a vase, mentioning that Selimkhanov, after his analysis of the Tello object (published in 1975), "attempted to relate the metal to Transcaucasian natural antimony" (i.e. native metal) and that "the antimony objects from Transcaucasia are all small personal ornaments." This weakens the evidence for a lost art "of rendering antimony malleable."

The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

described several ways of preparing antimony sulfide for medical purposes in his treatise ''Natural History'', around 77 AD. Pliny the Elder also made a distinction between "male" and "female" forms of antimony; the male form is probably the sulfide, while the female form, which is superior, heavier, and less friable, has been suspected to be native metallic antimony.

The Greek naturalist Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

mentioned that antimony sulfide could be roasted by heating by a current of air. It is thought that this produced metallic antimony.

Pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber (or "Latin pseudo-Geber") is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attributed to Jabir ...

, written around the 14th century. A description of a procedure for isolating antimony is later given in the 1540 book ''De la pirotechnia

''De la Pirotechnia'' is considered to be one of the first printed books on metallurgy to have been published in Europe. It was written in Italian and first published in Venice in 1540. The author was Vannoccio Biringuccio, a citizen of Siena, ...

'' by Vannoccio Biringuccio

Vannoccio Biringuccio, sometimes spelled Vannocio Biringuccio (c. 1480 – c. 1539), was an Italian metallurgist. He is best known for his manual on metalworking, '' De la pirotechnia'', published posthumously in 1540.

20th Century translation by ...

, predating the more famous 1556 book by Agricola

Agricola, the Latin word for farmer, may also refer to:

People Cognomen or given name

:''In chronological order''

* Gnaeus Julius Agricola (40–93), Roman governor of Britannia (AD 77–85)

* Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, Roman governor of the mi ...

, '' De re metallica''. In this context Agricola has been often incorrectly credited with the discovery of metallic antimony. The book ''Currus Triumphalis Antimonii'' (The Triumphal Chariot of Antimony), describing the preparation of metallic antimony, was published in Germany in 1604. It was purported to be written by a Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

monk, writing under the name Basilius Valentinus

Basil Valentine is the Anglicised version of the name Basilius Valentinus, ostensibly a 15th-century alchemist, possibly Canon of the Benedictine Priory of Saint Peter in Erfurt, Germany but more likely a pseudonym used by one or several 16th-ce ...

in the 15th century; if it were authentic, which it is not, it would predate Biringuccio.

The metal antimony was known to German chemist Andreas Libavius

Andreas Libavius or Andrew Libavius was born in Halle, Germany c. 1550 and died in July 1616. Libavius was a renaissance man who spent time as a professor at the University of Jena teaching history and poetry. After which he became a physician a ...

in 1615 who obtained it by adding iron to a molten mixture of antimony sulfide, salt and potassium tartrate

A tartrate is a salt or ester of the organic compound tartaric acid, a dicarboxylic acid. The formula of the tartrate dianion is O−OC-CH(OH)-CH(OH)-COO− or C4H4O62−.

The main forms of tartrates used commercially are pure crystalline ta ...

. This procedure produced antimony with a crystalline or starred surface.

With the advent of challenges to phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

, it was recognized that antimony is an element forming sulfides, oxides, and other compounds, as do other metals.

The first discovery of naturally occurring pure antimony in the Earth's crust was described by the Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

scientist and local mine district engineer Anton von Swab

Anton may refer to: People

*Anton (given name), including a list of people with the given name

*Anton (surname)

Places

*Anton Municipality, Bulgaria

**Anton, Sofia Province, a village

*Antón District, Panama

**Antón, a town and capital of th ...

in 1783; the type-sample was collected from the Sala Silver Mine

Sala Silver Mine ( sv, Sala silvergruva) is a mine in Sala Municipality, Sweden, Sala Municipality, in Västmanland County in Sweden. The mine was in continuous production from the 15th century until 1908. Additional mining occurred in 1950–1951 ...

in the Bergslagen mining district of Sala, Västmanland

Västmanland ( or ), is a historical Swedish province, or ''landskap'', in middle Sweden. It borders Södermanland, Närke, Värmland, Dalarna and Uppland.

Västmanland means "(The) Land of the Western Men", where the "western men" (''väst ...

, Sweden.

Etymology

The medieval Latin form, from which the modern languages and late Byzantine Greek take their names for antimony, is ''antimonium''. The origin of this is uncertain; all suggestions have some difficulty either of form or interpretation. The popular etymology, from ἀντίμοναχός ''anti-monachos'' or French ''antimoine'', still has adherents; this would mean "monk-killer", and is explained by many early alchemists being monks, and antimony being poisonous. However, the low toxicity of antimony (see below) makes this unlikely. Another popular etymology is the hypothetical Greek word ἀντίμόνος ''antimonos'', "against aloneness", explained as "not found as metal", or "not found unalloyed"."Antimony" in ''Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology'', 5th ed. 2004. Lippmann conjectured a hypothetical Greek word ανθήμόνιον ''anthemonion'', which would mean "floret", and cites several examples of related Greek words (but not that one) which describe chemical or biologicalefflorescence

In chemistry, efflorescence (which means "to flower out" in French) is the migration of a salt to the surface of a porous material, where it forms a coating. The essential process involves the dissolving of an internally held salt in water, or ...

.

The early uses of ''antimonium'' include the translations, in 1050–1100, by Constantine the African

Constantine the African ( la, Constantinus Africanus; died before 1098/1099, Monte Cassino) was a physician who lived in the 11th century. The first part of his life was spent in Ifriqiya and the rest in Italy. He first arrived in Italy in the ...

of Arabic medical treatises. Several authorities believe ''antimonium'' is a scribal corruption of some Arabic form; Meyerhof derives it from ''ithmid''; other possibilities include ''athimar'', the Arabic name of the metalloid, and a hypothetical ''as-stimmi'', derived from or parallel to the Greek.

The standard chemical symbol for antimony (Sb) is credited to Jöns Jakob Berzelius

Jöns is a Swedish given name and a surname.

Notable people with the given name include:

* Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848), Swedish chemist

* Jöns Budde (1435–1495), Franciscan friar from the Brigittine monastery in NaantaliVallis Grati ...

, who derived the abbreviation from ''stibium''.

The ancient words for antimony mostly have, as their chief meaning, kohl, the sulfide of antimony.

The Egyptians called antimony ''mśdmt''; quotes Meyerhof, the translator of the book he is reviewing. in hieroglyphs

A hieroglyph (Greek for "sacred carvings") was a character of the ancient Egyptian writing system. Logographic scripts that are pictographic in form in a way reminiscent of ancient Egyptian are also sometimes called "hieroglyphs". In Neoplatonis ...

, the vowels are uncertain, but the Coptic form of the word is ⲥⲧⲏⲙ (stēm).

Egyptian ''stm'': tragic

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy i ...

poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems ( oral or wri ...

s of the 5th century BC, and is possibly a loan word

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because the ...

from Arabic or from Egyptian ''stm''. Later Greeks also used στἰβι ''stibi'', as did Celsus

Celsus (; grc-x-hellen, Κέλσος, ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work, ''The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: grc-x-hellen, Λόγ� ...

and Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

, writing in Latin, in the first century AD. Pliny also gives the names ''stimi'', ''larbaris'', alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral or rock that is soft, often used for carving, and is processed for plaster powder. Archaeologists and the stone processing industry use the word differently from geologists. The former use it in a wider sense that include ...

, and the "very common" ''platyophthalmos'', "wide-eye" (from the effect of the cosmetic). Later Latin authors adapted the word to Latin as ''stibium''.

The Arabic word for the substance, as opposed to the cosmetic, can appear as إثمد ''ithmid, athmoud, othmod'', or ''uthmod''. Littré suggests the first form, which is the earliest, derives from ''stimmida'', an accusative for ''stimmi''.

Production

Process

The extraction of antimony from ores depends on the quality and composition of the ore. Most antimony is mined as the sulfide; lower-grade ores are concentrated byfroth flotation

Froth flotation is a process for selectively separating hydrophobic materials from hydrophilic. This is used in mineral processing, paper recycling and waste-water treatment industries. Historically this was first used in the mining industry, wher ...

, while higher-grade ores are heated to 500–600 °C, the temperature at which stibnite melts and separates from the gangue

In mining, gangue () is the commercially worthless material that surrounds, or is closely mixed with, a wanted mineral in an ore deposit. It is thus distinct from overburden, which is the waste rock or materials overlying an ore or mineral body ...

minerals. Antimony can be isolated from the crude antimony sulfide by reduction with scrap iron:

: + 3 Fe → 2 Sb + 3 FeS

The sulfide is converted to an oxide; the product is then roasted, sometimes for the purpose of vaporizing the volatile antimony(III) oxide, which is recovered. This material is often used directly for the main applications, impurities being arsenic and sulfide. Antimony is isolated from the oxide by a carbothermal reduction:

:2 + 3 C → 4 Sb + 3

The lower-grade ores are reduced in blast furnaces while the higher-grade ores are reduced in reverberatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgical or process furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is used here in a generic sense of ''re ...

s.

Top producers and production volumes

The British Geological Survey (BGS) reported that in 2005 China was the top producer of antimony with approximately 84% of the world share, followed at a distance by South Africa, Bolivia and Tajikistan.Xikuangshan Mine

Xikuangshan mine () in Lengshuijiang, Hunan, China, contains the world's largest deposit of antimony. It is unique in that there is a large deposit of stibnite (Sb2S3) in a layer of Devonian limestone. There are three mineral beds which are between ...

in Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi ...

province has the largest deposits in China with an estimated deposit of 2.1 million metric tons.

In 2016, according to the US Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, and ...

, China accounted for 76.9% of total antimony production, followed in second place by Russia with 6.9% and Tajikistan with 6.2%.

Chinese production of antimony is expected to decline in the future as mines and smelters are closed down by the government as part of pollution control. Especially due to an environmental protection law having gone into effect in January 2015 and revised "Emission Standards of Pollutants for Stanum, Antimony, and Mercury" having gone into effect, hurdles for economic production are higher. According to the National Bureau of Statistics in China, by September 2015 50% of antimony production capacity in the Hunan province (the province with biggest antimony reserves in China) had not been used.

Reported production of antimony in China has fallen and is unlikely to increase in the coming years, according to the Roskill report. No significant antimony deposits in China have been developed for about ten years, and the remaining economic reserves are being rapidly depleted.

The world's largest antimony producers, according to Roskill, are listed below:

Reserves

Supply risk

For antimony-importing regions such as Europe and the U.S., antimony is considered to be a critical mineral for industrial manufacturing that is at risk of supply chain disruption. With global production coming mainly from China (74%), Tajikistan (8%), and Russia (4%), these sources are critical to supply. *European Union: Antimony is considered a critical raw material for defense, automotive, construction and textiles. The E.U. sources are 100% imported, coming mainly from Turkey (62%), Bolivia (20%) and Guatemala (7%). *United Kingdom: The British Geological Survey's 2015 risk list ranks antimony second highest (afterrare earth elements

The rare-earth elements (REE), also called the rare-earth metals or (in context) rare-earth oxides or sometimes the lanthanides (yttrium and scandium are usually included as rare earths), are a set of 17 nearly-indistinguishable lustrous sil ...

) on the relative supply risk index.

*United States: Antimony is a mineral commodity considered critical to the economic and national security. In 2021, no antimony was mined in the U.S.

Applications

About 60% of antimony is consumed inflame retardant

The term flame retardants subsumes a diverse group of chemicals that are added to manufactured materials, such as plastics and textiles, and surface finishes and coatings. Flame retardants are activated by the presence of an ignition source and ...

s, and 20% is used in alloys for batteries, plain bearings, and solders.

Flame retardants

Antimony is mainly used as the trioxide for flame-proofing compounds, always in combination with halogenated flame retardants except in halogen-containing polymers. The flame retarding effect of antimony trioxide is produced by the formation of halogenated antimony compounds, which react with hydrogen atoms, and probably also with oxygen atoms and OH radicals, thus inhibiting fire. Markets for these flame-retardants include children's clothing, toys, aircraft, and automobile seat covers. They are also added topolyester resin Polyester resins are synthetic resins formed by the reaction of dibasic organic acids and polyhydric alcohols. Maleic anhydride is a commonly used raw material with diacid functionality in unsaturated polyester resins. Unsaturated polyester res ...

s in fiberglass

Fiberglass (American English) or fibreglass ( Commonwealth English) is a common type of fiber-reinforced plastic using glass fiber. The fibers may be randomly arranged, flattened into a sheet called a chopped strand mat, or woven into glass clo ...

composites for such items as light aircraft engine covers. The resin will burn in the presence of an externally generated flame, but will extinguish when the external flame is removed.Grund, Sabina C.; Hanusch, Kunibert; Breunig, Hans J.; Wolf, Hans Uwe (2006) "Antimony and Antimony Compounds" in ''Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry'', Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.

Alloys

Antimony forms a highly usefulalloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductilit ...

with lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, increasing its hardness and mechanical strength. For most applications involving lead, varying amounts of antimony are used as alloying metal. In lead–acid batteries, this addition improves plate strength and charging characteristics. For sailboats, lead keels are used to provide righting moment, ranging from 600 lbs to over 200 tons for the largest sailing superyachts; to improve hardness and tensile strength of the lead keel, antimony is mixed with lead between 2% and 5% by volume. Antimony is used in antifriction alloys (such as Babbitt metal

Babbitt metal or bearing metal is any of several alloys used for the bearing surface in a plain bearing.

The original Babbitt alloy was invented in 1839 by Isaac Babbitt in Taunton, Massachusetts, United States. He disclosed one of his alloy recip ...

), in bullets and lead shot

Shot is a collective term for small spheres or pellets, often made of lead. These were the original projectiles for shotguns and are still fired primarily from shotguns and less commonly from riot guns and grenade launchers, although shot shell ...

, electrical cable

An electrical cable is an assembly of one or more wires running side by side or bundled, which is used to carry electric current.

One or more electrical cables and their corresponding connectors may be formed into a ''cable assembly'', whic ...

sheathing, type metal

In printing, type metal refers to the metal alloys used in traditional typefounding and hot metal typesetting. Historically, type metal was an alloy of lead, tin and antimony in different proportions depending on the application, be it individ ...

(for example, for linotype printing machines), solder

Solder (; NA: ) is a fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces after cooling. Metals or alloys suitable ...

(some "lead-free

The Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive 2002/95/EC (RoHS 1), short for Directive on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment, was adopted in February 2003 by the European Unio ...

" solders contain 5% Sb), in pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. Copper and antimony (and in antiquity lead) act as hardeners, but lead may be used in lower grades ...

, and in hardening alloys with low tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

content in the manufacturing of organ pipe

An organ pipe is a sound-producing element of the pipe organ that resonates at a specific pitch when pressurized air (commonly referred to as ''wind'') is driven through it. Each pipe is tuned to a specific note of the musical scale. A set o ...

s.

Other applications

Three other applications consume nearly all the rest of the world's supply. One application is as a stabilizer and catalyst for the production of polyethylene terephthalate. Another is as a fining agent to remove microscopic bubbles inglass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling ( quenching ...

, mostly for TV screens antimony ions interact with oxygen, suppressing the tendency of the latter to form bubbles. The third application is pigments.

In the 1990s antimony was increasingly being used in semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical conductivity value falling between that of a conductor, such as copper, and an insulator, such as glass. Its resistivity falls as its temperature rises; metals behave in the opposite way. ...

s as a dopant

A dopant, also called a doping agent, is a trace of impurity element that is introduced into a chemical material to alter its original electrical or optical properties. The amount of dopant necessary to cause changes is typically very low. When ...

in n-type silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic ta ...

wafers

A wafer is a crisp, often sweet, very thin, flat, light and dry biscuit, often used to decorate ice cream, and also used as a garnish on some sweet dishes. Wafers can also be made into cookies with cream flavoring sandwiched between them. They ...

for diodes, infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from around ...

detectors, and Hall-effect devices. In the 1950s, the emitters and collectors of n-p-n alloy junction transistor

The germanium alloy-junction transistor, or alloy transistor, was an early type of bipolar junction transistor, developed at General Electric and RCA in 1951 as an improvement over the earlier grown-junction transistor.

The usual construction o ...

s were doped with tiny beads of a lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

-antimony alloy. Indium antimonide

Indium antimonide (InSb) is a crystalline compound made from the elements indium (In) and antimony (Sb). It is a narrow- gap semiconductor material from the III- V group used in infrared detectors, including thermal imaging cameras, FLIR systems ...

is used as a material for mid-infrared detector

An infrared detector is a detector that reacts to infrared (IR) radiation. The two main types of detectors are thermal and photonic (photodetectors).

The thermal effects of the incident IR radiation can be followed through many temperature depen ...

s.

Biology and medicine have few uses for antimony. Treatments containing antimony, known as antimonials, are used as emetic

Vomiting (also known as emesis and throwing up) is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis ...

s. Antimony compounds are used as antiprotozoan drugs. Potassium antimonyl tartrate, or tartar emetic, was once used as an anti- schistosomal drug from 1919 on. It was subsequently replaced by praziquantel

Praziquantel (PZQ), sold under the brandname Biltricide among others, is a medication used to treat a number of types of parasitic worm infections in mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish. In humans specifically, it is used to treat sc ...

. Antimony and its compounds are used in several veterinary

Veterinary medicine is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, management, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, disorder, and injury in animals. Along with this, it deals with animal rearing, husbandry, breeding, research on nutri ...

preparations, such as anthiomaline and lithium antimony thiomalate, as a skin conditioner in ruminant

Ruminants (suborder Ruminantia) are hoofed herbivorous grazing or browsing mammals that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microbial actions. The ...

s. Antimony has a nourishing or conditioning effect on keratinized

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, h ...

tissues in animals.

Antimony-based drugs, such as meglumine antimoniate

Meglumine antimoniate is a medicine used to treat leishmaniasis. This includes visceral, mucocutaneous, and cutaneous leishmaniasis. It is given by injection into a muscle or into the area infected.

Side effects include loss of appetite, nausea ...

, are also considered the drugs of choice for treatment of leishmaniasis in domestic animal

This page gives a list of domesticated animals, also including a list of domestication of animals, animals which are or may be currently undergoing the process of domestication and animals that have an extensive relationship with humans beyond simp ...

s. Besides having low therapeutic indices, the drugs have minimal penetration of the bone marrow, where some of the ''Leishmania'' amastigotes reside, and curing the disease – especially the visceral form – is very difficult. Elemental antimony as an antimony pill was once used as a medicine. It could be reused by others after ingestion and elimination.

Antimony(III) sulfide

Antimony trisulfide (Sb2S3) is found in nature as the crystalline mineral stibnite and the amorphous red mineral (actually a mineraloid) metastibnite. It is manufactured for use in safety matches, military ammunition, explosives and fireworks. It ...

is used in the heads of some safety match

A match is a tool for starting a fire. Typically, matches are made of small wooden sticks or stiff paper. One end is coated with a material that can be ignited by friction generated by striking the match against a suitable surface. Wooden matc ...

es. Antimony sulfides help to stabilize the friction coefficient in automotive brake pad materials. Antimony is used in bullets, bullet tracers, paint, glass art, and as an opacifier

An opacifier is a substance added to a material in order to make the ensuing system opaque. An example of a chemical opacifier is titanium dioxide (TiO2), which is used as an opacifier in paints, in paper, and in plastics. It has very high refracti ...

in enamel. Antimony-124

Antimony (51Sb) occurs in two stable isotopes, 121Sb and 123Sb. There are 35 artificial radioactive isotopes, the longest-lived of which are 125Sb, with a half-life of 2.75856 years; 124Sb, with a half-life of 60.2 days; and 126Sb, with a half-li ...

is used together with beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form m ...

in neutron source

A neutron source is any device that emits neutrons, irrespective of the mechanism used to produce the neutrons. Neutron sources are used in physics, engineering, medicine, nuclear weapons, petroleum exploration, biology, chemistry, and nuclear p ...

s; the gamma ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically ...

s emitted by antimony-124 initiate the photodisintegration

Photodisintegration (also called phototransmutation, or a photonuclear reaction) is a nuclear process in which an atomic nucleus absorbs a high-energy gamma ray, enters an excited state, and immediately decays by emitting a subatomic particle. The ...

of beryllium. The emitted neutrons have an average energy of 24 keV. Natural antimony is used in startup neutron sources.

Historically, the powder derived from crushed antimony ('' kohl'') has been applied to the eyes with a metal rod and with one's spittle, thought by the ancients to aid in curing eye infections. The practice is still seen in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

and in other Muslim countries.

Precautions

The effects of antimony and its compounds on human and environmental health differ widely. Elemental antimony metal does not affect human and environmental health. Inhalation of antimony trioxide (and similar poorly soluble Sb(III) dust particles such as antimony dust) is considered harmful and suspected of causing cancer. However, these effects are only observed with female rats and after long-term exposure to high dust concentrations. The effects are hypothesized to be attributed to inhalation of poorly soluble Sb particles leading to impaired lung clearance, lung overload, inflammation and ultimately tumour formation, not to exposure to antimony ions (OECD, 2008). Antimony chlorides are corrosive to skin. The effects of antimony are not comparable to those of arsenic; this might be caused by the significant differences of uptake, metabolism, and excretion between arsenic and antimony. For oral absorption, ICRP (1994) has recommended values of 10% for tartar emetic and 1% for all other antimony compounds. Dermal absorption for metals is estimated to be at most 1% (HERAG, 2007). Inhalation absorption of antimony trioxide and other poorly soluble Sb(III) substances (such as antimony dust) is estimated at 6.8% (OECD, 2008), whereas a value <1% is derived for Sb(V) substances. Antimony(V) is not quantitatively reduced to antimony(III) in the cell, and both species exist simultaneously. Antimony is mainly excreted from the human body via urine. Antimony and its compounds do not cause acute human health effects, with the exception ofantimony potassium tartrate

Antimony potassium tartrate, also known as potassium antimonyl tartrate, potassium antimontarterate, or tartar emetic, has the formula K2Sb2(C4H2O6)2. The compound has long been known as a powerful emetic, and was used in the treatment of schistoso ...

("tartar emetic"), a prodrug that is intentionally used to treat leishmaniasis patients.

Prolonged skin contact with antimony dust may cause dermatitis. However, it was agreed at the European Union level that the skin rashes observed are not substance-specific, but most probably due to a physical blocking of sweat ducts (ECHA/PR/09/09, Helsinki, 6 July 2009). Antimony dust may also be explosive when dispersed in the air; when in a bulk solid it is not combustible.

Antimony is incompatible with strong acids, halogenated acids, and oxidizers; when exposed to newly formed hydrogen it may form stibine (SbH3).

The 8-hour time-weighted average (TWA) is set at 0.5 mg/m3 by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists

The American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) is a professional association of industrial hygienists and practitioners of related professions, with headquarters in Cincinnati, Ohio. One of its goals is to advance worker pr ...

and by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration'' (OSHA ) is a large regulatory agency of the United States Department of Labor that originally had federal visitorial powers to inspect and examine workplaces. Congress established the agenc ...

(OSHA) as a legal permissible exposure limit

The permissible exposure limit (PEL or OSHA PEL) is a legal limit in the United States for exposure of an employee to a chemical substance or physical agent such as high level noise. Permissible exposure limits are established by the Occupational ...

(PEL) in the workplace. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, ) is the United States federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. NIOSH is part of the C ...

(NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit

A recommended exposure limit (REL) is an occupational exposure limit that has been recommended by the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The REL is a level that NIOSH believes would be protective of worker safet ...

(REL) of 0.5 mg/m3 as an 8-hour TWA.

Antimony compounds are used as catalysts for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) production. Some studies report minor antimony leaching from PET bottles into liquids, but levels are below drinking water guidelines. Antimony concentrations in fruit juice concentrates were somewhat higher (up to 44.7 µg/L of antimony), but juices do not fall under the drinking water regulations. The drinking water guidelines are:

* World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

: 20 µg/L

* Japan: 15 µg/L

* United States Environmental Protection Agency

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent executive agency of the United States federal government tasked with environmental protection matters. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970; it ...

, Health Canada and the Ontario Ministry of Environment: 6 µg/L

* EU and German Federal Ministry of Environment: 5 µg/L

The tolerable daily intake Tolerable daily intake (TDI) refers to the daily amount of a chemical that has been assessed safe for human being on long-term basis (usually whole lifetime). Originally acceptable daily intake (ADI) was introduced in 1961 to define the daily intake ...

(TDI) proposed by WHO is 6 µg antimony per kilogram of body weight. The immediately dangerous to life or health

The term immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) is defined by the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as exposure to airborne contaminants that is "likely to cause death or immediate or delayed permanent advers ...

(IDLH) value for antimony is 50 mg/m3.

Toxicity

Certain compounds of antimony appear to be toxic, particularly antimony trioxide and antimony potassium tartrate. Effects may be similar to arsenic poisoning. Occupational exposure may cause respiratory irritation, pneumoconiosis, antimony spots on the skin, gastrointestinal symptoms, and cardiac arrhythmias. In addition, antimony trioxide is potentially carcinogenic to humans. Adverse health effects have been observed in humans and animals following inhalation, oral, or dermal exposure to antimony and antimony compounds. Antimony toxicity typically occurs either due to occupational exposure, during therapy or from accidental ingestion. It is unclear if antimony can enter the body through the skin. The presence of low levels of antimony in saliva may also be associated withdental decay

Tooth decay, also known as cavities or caries, is the breakdown of teeth due to acids produced by bacteria. The cavities may be a number of different colors from yellow to black. Symptoms may include pain and difficulty with eating. Complicatio ...

.

See also

*Phase change memory

Phase-change memory (also known as PCM, PCME, PRAM, PCRAM, OUM (ovonic unified memory) and C-RAM or CRAM (chalcogenide RAM)) is a type of non-volatile random-access memory. PRAMs exploit the unique behaviour of chalcogenide glass. In PCM, heat p ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * Edmund Oscar von Lippmann (1919) Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie, teil 1. Berlin: Julius Springer (in German).Public Health Statement for Antimony

External links

International Antimony Association vzw (i2a

Chemistry in its element podcast

(MP3) from the

Royal Society of Chemistry

The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) is a learned society (professional association) in the United Kingdom with the goal of "advancing the chemical sciences". It was formed in 1980 from the amalgamation of the Chemical Society, the Royal Instit ...

's Chemistry WorldAntimony

at ''

The Periodic Table of Videos

''Periodic Videos'' (also known as ''The Periodic Table of Videos'') is a video project and YouTube channel on chemistry. It consists of a series of videos about chemical elements and the periodic table, with additional videos on other topics i ...

'' (University of Nottingham)

CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Antimony

Antimony Mineral data and specimen images

{{Authority control Chemical elements Metalloids Native element minerals Nuclear materials Pnictogens Trigonal minerals Minerals in space group 166 Materials that expand upon freezing Chemical elements with rhombohedral structure