Annamese kowtowing to French soldiers.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

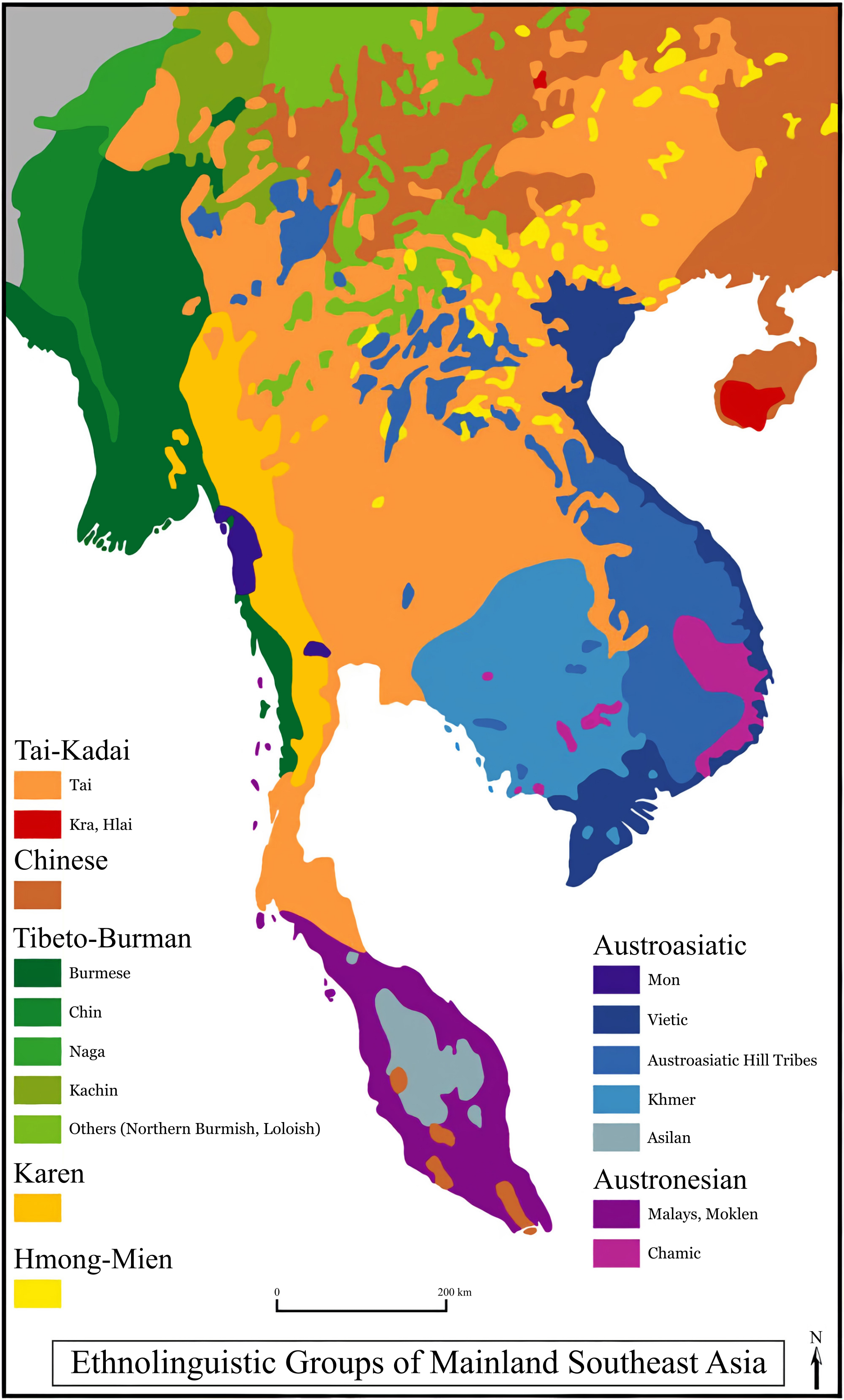

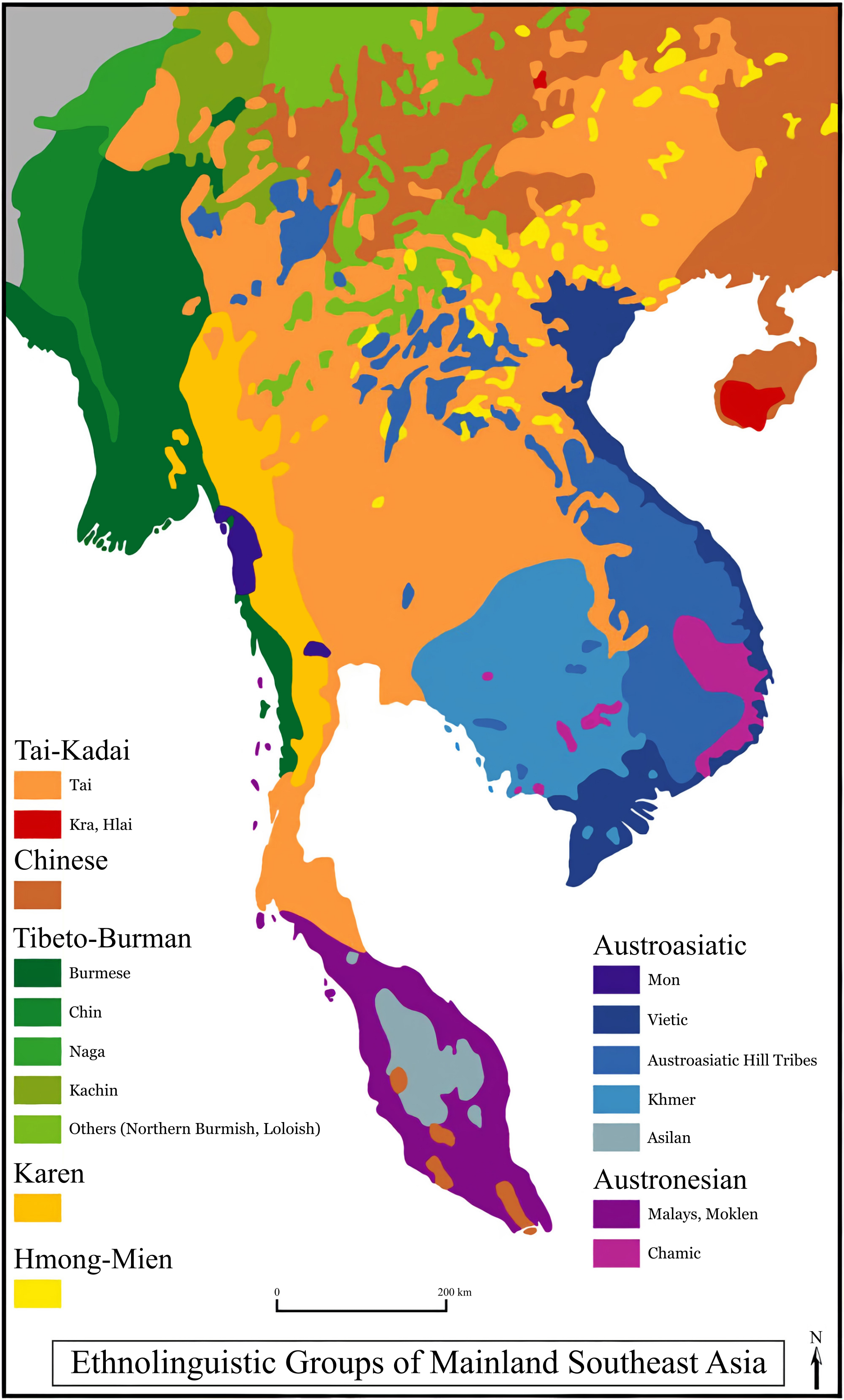

The Vietnamese people ( vi, người Việt, lit=Viet people) or Kinh people ( vi, người Kinh) are a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to modern-day Northern Vietnam and Dongxing, Guangxi, Southern China (Jing Islands, Dongxing, Guangxi). The native language is Vietnamese language, Vietnamese, the most widely spoken Austroasiatic language.

Vietnamese Kinh people account for just over 85.32% of the population of Vietnam in the 2019 census, and are officially known as Kinh people () to distinguish them from the other ethnic groups in Vietnam, minority groups residing in the country such as the Hmong people, Hmong, Chams, Cham, or Muong people, Mường. The Vietnamese are one of the four main groups of Vietic languages, Vietic speakers in Vietnam, the others being the Muong people, Mường, Thổ people, Thổ, and Chứt people. They are related to the Gin people, Gin people, a Vietnamese ethnic group in China.

"Shang Dynasty - Political History"

in ''ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art''. quote: "Enemies of the Shang state were called fang 方 "regions", like the Tufang 土方, which roamed the northern region of Shanxi, the Guifang, Guifang 鬼方 and Gongfang 𢀛方 in the northwest, the Qiang (historical people), Qiangfang 羌方, Suifang 繐方, Yuefang 戉方, Xuanfang 亘方 and Zhou dynasty, Zhoufang 周方 in the west, as well as the Dongyi, Yifang 夷方 and Renfang 人方 in the southeast." In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yangyue, a term later used for peoples further south. Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC Yue/Việt referred to the Yue (state), State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people. From the 3rd century BC the term was used for the non-Chinese populations of south and southwest China and northern Vietnam, with particular ethnic groups called Minyue, Ouyue (Vietnamese: Âu Việt), Luoyue (Vietnamese: Lạc Việt), etc., collectively called the Baiyue (Bách Việt, ; ). The term Baiyue/Bách Việt first appeared in the book ''Lüshi Chunqiu'' compiled around 239 BC. According to Ye Wenxian (1990), apud Wan (2013), the ethnonym of the Yuefang in northwestern China is not associated with that of the Baiyue in southeastern China. The late medieval period saw the rise of Vietnamese elites identified themselves with the ancient Yue in order to incline with 'an ancient origin', and that identity might have born by constructing traditions. By the 17th and 18th centuries AD, educated Vietnamese apparently referred to themselves as ''người Việt'' 𠊛越 (Viet people) or ''người Nam'' 𠊛南 (southern people).

Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic

In ''Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics'', 174-193. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Special Publication No. 3. University of Hawaii Press.Blench, Roger. 2017.

Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic

'. Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.Sidwell, Paul. 2015b. ''Phylogeny, innovations, and correlations in the prehistory of Austroasiatic''. Paper presented at the workshop ''Integrating inferences about our past: new findings and current issues in the peopling of the Pacific and South East Asia'', 22–23 June 2015, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany. Some linguists (James Chamberlain, Joachim Schliesinger) suggested that the Vietic-speaking people migrated from North Central Coast, North Central Region to the Red River Delta, which had originally been inhabited by Tai languages, Tai-Tai peoples, speakers. However, Michael Churchman found no records of population shifts in Jiaozhi (centered around the Red River Delta) in Chinese sources, indicating that a fairly stable population of Austroasiatic speakers, ancestral to modern Vietnamese, inhabited in the delta during the Han dynasty, Han-Tang dynasty, Tang periods. Other proposes that Northern Vietnam and Southern China were never homogeneous in term of ethnicity and languages, but peoples shared some customs. These ancient tribes did not have any kind of defined ethnic boundary and could not be described as "Vietnamese" (Kinh) in any satisfactory sense. Any attempt of identify an ethnic group in ancient Vietnam is problematized inaccurate. Another theory, based on linguistic diversity, locates the most probable homeland of the Vietic languages in modern-day Bolikhamsai Province and Khammouane Province in Laos as well as parts of Nghệ An Province and Quảng Bình Province in Vietnam. In the 1930s, clusters of Vietic-speaking communities were discovered in the hills of eastern Laos, are believed to be the earliest inhabitants of that region. Archaeogenetics demonstrated that before the Đông Sơn culture, Dong Son period, the Red River Delta's inhabitants were predominantly Austroasiatic: genetic data from Phùng Nguyên culture's Mán Bạc burial site (dated 1,800 BC) have close proximity to modern Austroasiatic speakers such as the Khmer people, Khmer and Mlabri people, Mlabri; meanwhile, "mixed genetics" from Đông Sơn culture's Núi Nấp site showed affinity to "Dai people, Dai from China, Kra-Dai languages, Tai-Kadai speakers from Thailand, and Austroasiatic speakers from Vietnam, including the Kinh people, Kinh". According to Vietnamese legend ''The Tale the Hồng Bàng Clan'' (''Hồng Bàng'' thị truyện) written in the 15th century, the first Vietnamese descended from the Vietnamese dragon, dragon lord Lạc Long Quân and the fairy Âu Cơ. They married and had one hundred eggs, from which hatched one hundred children. Their eldest son ruled as the Hùng king. The Hùng kings were claimed to be descended from the mythical figure Shen Nong.

The earliest reference of the proto-Vietnamese in Chinese annals was the ''Lạc'' (Chinese: Luo), ''Lạc Việt'', or the Dongsonian, an ancient tribal confederacy of perhaps polyglot Austroasiatic language, Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai language, Kra-Dai speakers occupied the Red River Delta. The Lạc developed the metallurgical Dong Son Culture, Đông Sơn Culture and the Văn Lang chiefdom, ruled by the semi-mythical Hùng kings. To the south of the Dongsonians was the Sa Huỳnh culture, Sa Huỳnh Culture of the Austronesian people, Austronesian Chamic language, Chamic people. Around 400–200 BC, the Lạc came to contact with the Âu Việt (a splinter group of Tai people) and the Sinitic people from the north. According to a late third or early fourth century AD Chinese chronicle, the leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, conquered Văn Lang and deposed the last Hùng Duệ Vương, Hùng king. Having submissions of Lạc lords, Thục Phán proclaimed himself King An Dương of Âu Lạc kingdom.

In 179 BC, Zhao Tuo, a Chinese general who has established the Nanyue state in modern-day Southern China, annexed Âu Lạc, and began the Sino-Vietic interaction that lasted in a millennium. In 111 BC, the Han dynasty, Han Empire conquered Nanyue, brought the Northern Vietnam region under Han rule.

By the 7th century to 9th century AD, as the Tang Empire ruled over the region, historians such as Henri Maspero proposed that Vietnamese-speaking people became separated from other Vietic groups such as the Muong people, Mường and Chut people, Chứt due to heavier Chinese influences on the Vietnamese. Other argue that a Vietic migration from north central Vietnam to the Red River Delta in the seventh century replaced the original Tai-speaking inhabitants. In the mid-9th century, local rebels aided by Nanzhao tore the Tang Chinese rule to nearly collapse. The Tang reconquered the region in 866, causing half of the local rebels to flee into the mountains, which historians believe that was the separation between the Muong people, Mường and the Vietnamese took at the end of Tang rule in Vietnam. In 938, the Vietnamese leader Ngô Quyền who was a native of Thanh Hoa, Thanh Hóa, led Viet forces defeated the Chinese Southern Han armada at Battle of Bạch Đằng (938), Bạch Đằng River and proclaimed himself king, became the first Viet king of polity that now could be perceived as "Vietnamese".

The earliest reference of the proto-Vietnamese in Chinese annals was the ''Lạc'' (Chinese: Luo), ''Lạc Việt'', or the Dongsonian, an ancient tribal confederacy of perhaps polyglot Austroasiatic language, Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai language, Kra-Dai speakers occupied the Red River Delta. The Lạc developed the metallurgical Dong Son Culture, Đông Sơn Culture and the Văn Lang chiefdom, ruled by the semi-mythical Hùng kings. To the south of the Dongsonians was the Sa Huỳnh culture, Sa Huỳnh Culture of the Austronesian people, Austronesian Chamic language, Chamic people. Around 400–200 BC, the Lạc came to contact with the Âu Việt (a splinter group of Tai people) and the Sinitic people from the north. According to a late third or early fourth century AD Chinese chronicle, the leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, conquered Văn Lang and deposed the last Hùng Duệ Vương, Hùng king. Having submissions of Lạc lords, Thục Phán proclaimed himself King An Dương of Âu Lạc kingdom.

In 179 BC, Zhao Tuo, a Chinese general who has established the Nanyue state in modern-day Southern China, annexed Âu Lạc, and began the Sino-Vietic interaction that lasted in a millennium. In 111 BC, the Han dynasty, Han Empire conquered Nanyue, brought the Northern Vietnam region under Han rule.

By the 7th century to 9th century AD, as the Tang Empire ruled over the region, historians such as Henri Maspero proposed that Vietnamese-speaking people became separated from other Vietic groups such as the Muong people, Mường and Chut people, Chứt due to heavier Chinese influences on the Vietnamese. Other argue that a Vietic migration from north central Vietnam to the Red River Delta in the seventh century replaced the original Tai-speaking inhabitants. In the mid-9th century, local rebels aided by Nanzhao tore the Tang Chinese rule to nearly collapse. The Tang reconquered the region in 866, causing half of the local rebels to flee into the mountains, which historians believe that was the separation between the Muong people, Mường and the Vietnamese took at the end of Tang rule in Vietnam. In 938, the Vietnamese leader Ngô Quyền who was a native of Thanh Hoa, Thanh Hóa, led Viet forces defeated the Chinese Southern Han armada at Battle of Bạch Đằng (938), Bạch Đằng River and proclaimed himself king, became the first Viet king of polity that now could be perceived as "Vietnamese".

Ngô Quyền died in 944 and his kingdom collapsed into chaos and disturbances between twelve warlords and chiefs. In 968, a leader named Đinh Bộ Lĩnh united them and established the Đại Việt (Great Việt) kingdom. With assistance of powerful Buddhist monks, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh chose Hoa Lư in the southern edge of the Red River Delta as the capital instead of Tang-era Dai La, Đại La, adopted Chinese-style imperial titles, coinage, and ceremonies and tried to preserve the Chinese administrative framework. The independence of Đại Việt, according to Andrew Chittick, allows it "to develop its own distinctive political culture and ethnic consciousness." In 979 Dinh Bo Linh was assassinated, and Queen Duong Van Nga married with Dinh's general Le Hoan, appointed him as king. Disturbances in Đại Việt attracted attentions from neighbouring Chinese Song dynasty and Champa Kingdom, but they were defeated by Lê Hoàn. A Khmer inscription dated 987 records the arrival of Vietnamese merchants (Yuon) in Angkor. Chinese writers, Song Hao, Fan Chengda and Zhou Qufei, both reported that the inhabitants of Đại Việt "tattooed their foreheads, crossed feet, black teeth, bare feet and blacken clothing." The early 11th century Cham language, Cham inscription of Chiên Đàn, My Son, erected by king of Champa Harivarman IV (r. 1074–1080), mentions that he had offered Khmer (Kmīra/Kmir) and Viet (Yvan) prisoners as slaves to various local gods and temples of the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon.

Successive Vietnamese royal families from the Đinh, Lê, Lý dynasties and (Hoa people, Hoa)/Chinese ancestry Trần and Hồ dynasties ruled the kingdom peacefully from 968 to 1407. Emperor Lý Thái Tổ (r. 1009–1028) relocated the Vietnamese capital from Hoa Lư to Hanoi, the center of the Red River Delta in 1010. They practiced elitist marriage alliances between clans and nobles in the country. Mahayana Buddhism became state religion, Vietnamese music instruments, dancing and religious worshipping were influenced by both Cham, Indian and Chinese styles, while Confucianism slowly gained attention and influence. The earliest surviving corpus and text in Vietnamese language dated early 12th century, and surviving ''chữ nôm'' script inscriptions dated early 13th century, showcasing enormous influences of Chinese culture among the early Vietnamese elites.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty unsuccessful invaded Đại Việt in the 1250s and 1280s, though they sacked Hanoi. The Ming dynasty of China conquered Đại Việt in 1406, brought the Vietnamese under Chinese rule for 20 years, before they were driven out by Vietnamese leader Lê Lợi. The fourth grandson of Lê Lợi, king Lê Thánh Tông (r. 1460–1497), is considered one of the greatest monarchs in Vietnamese history. His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, military, education, and fiscal reforms he instituted, and a cultural revolution that replaced the old traditional aristocracy with a generation of literati scholars, adopted Confucianism, and transformed a Đại Việt from a Southeast Asian style polity to a bureaucratic state, and flourished. Thánh Tông's forces, armed with gunpowder weapons, overwhelmed the long-term rival Champa in 1471, then launched an unsuccessful invasion against the Laotian and Lan Na kingdoms in the 1480s.

Ngô Quyền died in 944 and his kingdom collapsed into chaos and disturbances between twelve warlords and chiefs. In 968, a leader named Đinh Bộ Lĩnh united them and established the Đại Việt (Great Việt) kingdom. With assistance of powerful Buddhist monks, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh chose Hoa Lư in the southern edge of the Red River Delta as the capital instead of Tang-era Dai La, Đại La, adopted Chinese-style imperial titles, coinage, and ceremonies and tried to preserve the Chinese administrative framework. The independence of Đại Việt, according to Andrew Chittick, allows it "to develop its own distinctive political culture and ethnic consciousness." In 979 Dinh Bo Linh was assassinated, and Queen Duong Van Nga married with Dinh's general Le Hoan, appointed him as king. Disturbances in Đại Việt attracted attentions from neighbouring Chinese Song dynasty and Champa Kingdom, but they were defeated by Lê Hoàn. A Khmer inscription dated 987 records the arrival of Vietnamese merchants (Yuon) in Angkor. Chinese writers, Song Hao, Fan Chengda and Zhou Qufei, both reported that the inhabitants of Đại Việt "tattooed their foreheads, crossed feet, black teeth, bare feet and blacken clothing." The early 11th century Cham language, Cham inscription of Chiên Đàn, My Son, erected by king of Champa Harivarman IV (r. 1074–1080), mentions that he had offered Khmer (Kmīra/Kmir) and Viet (Yvan) prisoners as slaves to various local gods and temples of the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon.

Successive Vietnamese royal families from the Đinh, Lê, Lý dynasties and (Hoa people, Hoa)/Chinese ancestry Trần and Hồ dynasties ruled the kingdom peacefully from 968 to 1407. Emperor Lý Thái Tổ (r. 1009–1028) relocated the Vietnamese capital from Hoa Lư to Hanoi, the center of the Red River Delta in 1010. They practiced elitist marriage alliances between clans and nobles in the country. Mahayana Buddhism became state religion, Vietnamese music instruments, dancing and religious worshipping were influenced by both Cham, Indian and Chinese styles, while Confucianism slowly gained attention and influence. The earliest surviving corpus and text in Vietnamese language dated early 12th century, and surviving ''chữ nôm'' script inscriptions dated early 13th century, showcasing enormous influences of Chinese culture among the early Vietnamese elites.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty unsuccessful invaded Đại Việt in the 1250s and 1280s, though they sacked Hanoi. The Ming dynasty of China conquered Đại Việt in 1406, brought the Vietnamese under Chinese rule for 20 years, before they were driven out by Vietnamese leader Lê Lợi. The fourth grandson of Lê Lợi, king Lê Thánh Tông (r. 1460–1497), is considered one of the greatest monarchs in Vietnamese history. His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, military, education, and fiscal reforms he instituted, and a cultural revolution that replaced the old traditional aristocracy with a generation of literati scholars, adopted Confucianism, and transformed a Đại Việt from a Southeast Asian style polity to a bureaucratic state, and flourished. Thánh Tông's forces, armed with gunpowder weapons, overwhelmed the long-term rival Champa in 1471, then launched an unsuccessful invasion against the Laotian and Lan Na kingdoms in the 1480s.

With the death of Thánh Tông in 1497, the Đại Việt kingdom swiftly declined. Climate extremes, failing crops, regionalism and factionism tore the Vietnamese apart. From 1533 to 1790s, four powerful Vietnamese families: Mạc, Lê, Trịnh and Nguyễn, each ruled on their own domains. In northern Vietnam (Đàng Ngoài–outer realm), the Lê Emperors barely sat on the throne while the Trịnh lords held power of the court. The Mạc controlled northeast Vietnam. The Nguyễn lords ruled the southern polity of Đàng Trong (inner realm). Thousands of ethnic Vietnamese migrated south, settled on the old Cham lands. European missionaries and traders from the sixteenth century brought new religion, ideas and crops to the Vietnamese (Annamese). By 1639, there were 82,500 Catholic converts throughout Vietnam. In 1651, Alexandre de Rhodes published a 300-pages catechism in Latin and romanized-Vietnamese (''chữ Quốc Ngữ'') or the Vietnamese alphabet.

The Vietnamese Fragmentation period ended in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, who was aided by French mercenaries defeated the Tay Son dynasty, Tay Son kingdoms and reunited Vietnam. Through assimilation and brutal subjugation in the 1830s by Minh Mang, a large chunk of indigenous Cham people, Cham had been assimilated into Vietnamese. By 1847, the Vietnamese state under Emperor Thieu Tri, Thiệu Trị, people that identified them as "người Việt Nam" accounted for nearly 80 percent of the country's population. This demographic model continues to persist through the French Indochina, French Indochina in World War II, Japanese occupation and modern day.

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the French Cochinchina, French colony of Cochinchina. By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated into the two protectorates of Annam (French protectorate), Annam and Tonkin (French protectorate), Tonkin. The three Vietnamese entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887. The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society. A Western-style system of modern education introduced new humanism, humanist values into Vietnam.

With the death of Thánh Tông in 1497, the Đại Việt kingdom swiftly declined. Climate extremes, failing crops, regionalism and factionism tore the Vietnamese apart. From 1533 to 1790s, four powerful Vietnamese families: Mạc, Lê, Trịnh and Nguyễn, each ruled on their own domains. In northern Vietnam (Đàng Ngoài–outer realm), the Lê Emperors barely sat on the throne while the Trịnh lords held power of the court. The Mạc controlled northeast Vietnam. The Nguyễn lords ruled the southern polity of Đàng Trong (inner realm). Thousands of ethnic Vietnamese migrated south, settled on the old Cham lands. European missionaries and traders from the sixteenth century brought new religion, ideas and crops to the Vietnamese (Annamese). By 1639, there were 82,500 Catholic converts throughout Vietnam. In 1651, Alexandre de Rhodes published a 300-pages catechism in Latin and romanized-Vietnamese (''chữ Quốc Ngữ'') or the Vietnamese alphabet.

The Vietnamese Fragmentation period ended in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, who was aided by French mercenaries defeated the Tay Son dynasty, Tay Son kingdoms and reunited Vietnam. Through assimilation and brutal subjugation in the 1830s by Minh Mang, a large chunk of indigenous Cham people, Cham had been assimilated into Vietnamese. By 1847, the Vietnamese state under Emperor Thieu Tri, Thiệu Trị, people that identified them as "người Việt Nam" accounted for nearly 80 percent of the country's population. This demographic model continues to persist through the French Indochina, French Indochina in World War II, Japanese occupation and modern day.

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the French Cochinchina, French colony of Cochinchina. By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated into the two protectorates of Annam (French protectorate), Annam and Tonkin (French protectorate), Tonkin. The three Vietnamese entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887. The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society. A Western-style system of modern education introduced new humanism, humanist values into Vietnam.

Despite having a long recorded history of the Vietnamese language and people, the identification and distinction of 'ethnic Vietnamese' or ethnic Kinh, as well as other ethnic groups in Vietnam, were only begun by colonial administration in the late 19th and early 20th century. Following colonial government's efforts of ethnic classificating, nationalism, especially ethnic nationalism, ethnonationalism and eugenic Social Darwinism were encouraged among the new Vietnamese intelligentsias discourse. Ethnic tensions sparked by Vietnamese ethnonationalism peaked during the late 1940s at the beginning phase of the First Indochina War (1946–1954), which resulted in violences between Khmer and Vietnamese in the Mekong Delta. Further North Vietnam's Soviet-style social integrational and ethnic classification, tried to build an image of Diversity under the harmony of Socialism, promoting the idea of the Vietnamese nation as a 'great single family' comprised by many different ethnic groups, and Vietnamese ethnic chauvinism was officially discouraged.

Despite having a long recorded history of the Vietnamese language and people, the identification and distinction of 'ethnic Vietnamese' or ethnic Kinh, as well as other ethnic groups in Vietnam, were only begun by colonial administration in the late 19th and early 20th century. Following colonial government's efforts of ethnic classificating, nationalism, especially ethnic nationalism, ethnonationalism and eugenic Social Darwinism were encouraged among the new Vietnamese intelligentsias discourse. Ethnic tensions sparked by Vietnamese ethnonationalism peaked during the late 1940s at the beginning phase of the First Indochina War (1946–1954), which resulted in violences between Khmer and Vietnamese in the Mekong Delta. Further North Vietnam's Soviet-style social integrational and ethnic classification, tried to build an image of Diversity under the harmony of Socialism, promoting the idea of the Vietnamese nation as a 'great single family' comprised by many different ethnic groups, and Vietnamese ethnic chauvinism was officially discouraged.

Originally from northern Vietnam and southern China, the Vietnamese have expanded south and conquered much of the land belonging to the former Champa Kingdom and Khmer Empire over the centuries. They are the dominant ethnic group in most provinces of Vietnam, and constitute a small percentage of the population in neighbouring Cambodia.

Beginning around the sixteenth century, groups of Vietnamese migrated to Cambodia and China for commerce and political purposes. Descendants of Vietnamese migrants in China form the Gin people, Gin ethnic group in the country and primarily reside in and around Guangxi Province. Vietnamese form the largest ethnic minority group in Cambodia, at 5% of the population. Under the Khmer Rouge, they were heavily persecuted and survivors of the regime largely fled to Vietnam.

During French Indochina, French colonialism, Vietnam was regarded as the most important colony in Asia by the French colonial powers, and the Vietnamese had a higher social standing than other ethnic groups in French Indochina. As a result, educated Vietnamese were often trained to be placed in colonial government positions in the other Asian French colonies of Laos and Cambodia rather than locals of the respective colonies. There was also a significant representation of Vietnamese students in France during this period, primarily consisting of members of the elite class. A large number of Vietnamese also migrated to France as workers, especially during World War I and World War II, when France recruited soldiers and locals of its colonies to help with war efforts in Metropolitan France. The wave of migrants to France during World War I formed the first major presence of Vietnamese people in France and the Western world.La Diaspora Vietnamienne en France un cas particulier

Originally from northern Vietnam and southern China, the Vietnamese have expanded south and conquered much of the land belonging to the former Champa Kingdom and Khmer Empire over the centuries. They are the dominant ethnic group in most provinces of Vietnam, and constitute a small percentage of the population in neighbouring Cambodia.

Beginning around the sixteenth century, groups of Vietnamese migrated to Cambodia and China for commerce and political purposes. Descendants of Vietnamese migrants in China form the Gin people, Gin ethnic group in the country and primarily reside in and around Guangxi Province. Vietnamese form the largest ethnic minority group in Cambodia, at 5% of the population. Under the Khmer Rouge, they were heavily persecuted and survivors of the regime largely fled to Vietnam.

During French Indochina, French colonialism, Vietnam was regarded as the most important colony in Asia by the French colonial powers, and the Vietnamese had a higher social standing than other ethnic groups in French Indochina. As a result, educated Vietnamese were often trained to be placed in colonial government positions in the other Asian French colonies of Laos and Cambodia rather than locals of the respective colonies. There was also a significant representation of Vietnamese students in France during this period, primarily consisting of members of the elite class. A large number of Vietnamese also migrated to France as workers, especially during World War I and World War II, when France recruited soldiers and locals of its colonies to help with war efforts in Metropolitan France. The wave of migrants to France during World War I formed the first major presence of Vietnamese people in France and the Western world.La Diaspora Vietnamienne en France un cas particulier

(in French) When Vietnam gained its independence from France in 1954, a number of Vietnamese loyal to the colonial government also migrated to France. During the partition of Vietnam into North Vietnam, North and South Vietnam, South, a number of South Vietnamese students also arrived to study in France, along with individuals involved in commerce for trade with France, which was a principal economic partner with South Vietnam.

When Vietnam gained its independence from France in 1954, a number of Vietnamese loyal to the colonial government also migrated to France. During the partition of Vietnam into North Vietnam, North and South Vietnam, South, a number of South Vietnamese students also arrived to study in France, along with individuals involved in commerce for trade with France, which was a principal economic partner with South Vietnam.

Forced repatriation in 1970 and deaths during the Khmer Rouge era reduced the Vietnamese Cambodian, Vietnamese population in Cambodia from between 250,000 and 300,000 in 1969 to a reported 56,000 in 1984.

The Fall of Saigon and end of the Vietnam War prompted the start of the Vietnamese diaspora, which saw millions of Vietnamese fleeing the country from the new communist regime. Recognizing an international humanitarian crisis, many countries accepted Vietnamese refugees, primarily the United States, France, Australia and Canada. Meanwhile, under the new communist regime, tens of thousands of Vietnamese were sent to work or study in Eastern Bloc countries of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe as development aid to the Vietnamese government and for migrants to acquire skills that were to be brought home to help with development. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a vast majority of these overseas Vietnamese decided to remain in their host nations.

Forced repatriation in 1970 and deaths during the Khmer Rouge era reduced the Vietnamese Cambodian, Vietnamese population in Cambodia from between 250,000 and 300,000 in 1969 to a reported 56,000 in 1984.

The Fall of Saigon and end of the Vietnam War prompted the start of the Vietnamese diaspora, which saw millions of Vietnamese fleeing the country from the new communist regime. Recognizing an international humanitarian crisis, many countries accepted Vietnamese refugees, primarily the United States, France, Australia and Canada. Meanwhile, under the new communist regime, tens of thousands of Vietnamese were sent to work or study in Eastern Bloc countries of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe as development aid to the Vietnamese government and for migrants to acquire skills that were to be brought home to help with development. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a vast majority of these overseas Vietnamese decided to remain in their host nations.

link to the article's abstract.

/ref> Kim Wook et al. (2000) said that, genetically, Vietnamese people more probably clustered with East Asians of which the study analyzed DNA samples of Chinese people, Chinese, Japanese people, Japanese, Koreans and Mongols, Mongolians rather than with Southeast Asians of which the study analyzed DNA samples of Indonesians, Filipinos, Thai people, Thais and Vietnamese. The study said that Vietnamese people were the only population in the study's Phylogenetics, phylogenetic analysis that did not reflect a sizable genetic difference between East Asian and Southeast Asian populations. The study said that the likely reason for Vietnamese people more probably clustering with East Asians was genetic drift and distinct Founder effect, founder populations. The study said that the alternative reason for Vietnamese people more probably clustering with East Asians is a recent Colonisation (biology), range expansion from South China. The study mentioned that the majority of its Vietnamese DNA samples were from Hanoi which is the closest region to South China. Schurr & Wallace (2002) said that Vietnamese people display genetic similarities with certain peoples from Malaysia. The study said that the aboriginal groups from Malaysia, the Orang Asli, are somewhat genetically intermediate between Malay people and Vietnamese. The study said that Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup, mtDNA haplogroup Haplogroup F (mtDNA), F is present at its highest frequency in Vietnamese and a high frequency of this haplogroup is also present in the Orang Asli, a people with whom Vietnamese have a linguistic connection (Austroasiatic languages).Schurr, Theodore G. & Wallace, Douglas C. (2002). Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Southeast Asian Populations. ''Human Biology (journal), Human Biology, 74''(3). Pages 433, 439, 446, 447 & 448. Retrieved January 7, 2018, fro

link.

/ref> Jung Jongsun et al. (2010) said that genetic structure analysis found significant admixture in "''Vietnamese (or Khmer people, Cambodian) with unknown Southern original settlers.''" The study said that it used Cambodians and Vietnamese to represent "Southern people," and the study used Cambodia (Khmer people, Khmer) and Vietnam (Kinh) as its populations for "South Asia." The study said that Chinese people are located between Koreans, Korean and Vietnamese people in the study's Gene mapping, genome map. The study also said that Vietnamese people are located between Chinese and Cambodian people in the study's genome map. He Jun-dong et al. (2012) did a principal component analysis using the Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, NRY haplogroup distribution frequencies of 45 populations, and the second principal component showed a close affinity between Kinh and Vietnamese who were most likely Kinh with populations from mainland South China, southern China because of the high frequency of NRY haplogroup Haplogroup O-K18, O-M88. The study said that Kinh often have NRY haplogroup Haplogroup O-M122, O-M7 which is the characteristic Chinese haplogroup. Out of the study's Sample (statistics), sample of seventy-six Kinh NRY haplogroups, twenty-three haplogroups (30.26%) were O-M88 and eight haplogroups (10.53%) were O-M7. The study said that, in ancient northern Vietnam, it is suggested that there has been considerable assimilation of inhabitants from present-day southern China through immigration into the Kinh people.He, Jun-dong et al. (2012). Patrilineal Perspective on the Austronesian Diffusion in Mainland Southeast Asia. In ''PLOS One, PLoS 7''(5), Page 7. Retrieved December 14, 2017, fro

link.

A 2015 study revealed that Vietnamese (Kinh) test subjects showed more genetic variants in common with Chinese compared to Japanese. Sara Pischedda et al. (2017) stated that modern Vietnamese have a major component of their ethnic origin coming from the now-called southern China region and a minor component from a Thai-Indonesian composite. The study said that admixture analysis indicates that Vietnamese Kinh have a major part which is most common in Han Chinese, Chinese and two minor parts which have the highest prevalence in the Bidayuh of Malaysia and the Proto-Malay. The study said that multidimensional scaling analysis indicates that Vietnamese Kinh have a closeness to Malay people, Thai and Chinese, and the study said that Malays and Thai are the samples which could be admixed with Chinese in the Vietnamese gene pool. The study said that Vietnamese Human mitochondrial genetics, mtDNA genetic variation matches well with the pattern seen in Southeast Asia, and the study said that most Vietnamese people had mtDNA haplotypes that clustered in clades Haplogroup M (mtDNA), M7 (20%) and Haplogroup R (mtDNA), R9’F (27%) which are clades that also dominate maternal lineages in Southeast Asia more generally.Pischedda, S. et al. (2017). Phylogeographic and genome-wide investigations of Vietnam ethnic groups reveal signatures of complex historical demographic movements. ''Scientific Reports, 7''(1). Pages 4, 6, 11, 13, & 14. Digital object identifier, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12813-6 Retrieved January 6, 2018, fro

link.

/ref>

link to the article.

/ref> However, such a theory is not within the mainstream genetic study of most historians and scholars due to the lack of evidence of any such migration path ever occurring.

''The Making of South East Asia''

(illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. . Retrieved 7 August 2013. * * * * *Contributor: Far-Eastern Prehistory Associatio

''Asian Perspectives, Volume 28, Issue 1''

(1990) University Press of Hawaii. Retrieved 7 August 2013. * *Hall, Kenneth R., ed. (2008)

''Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, C. 1400–1800''

Volume 1 of Comparative urban studies. Lexington Books. . Retrieved 7 August 2013. * * * * * * * * * * *Marr, David G. (2010). Vietnamese, Chinese, and Overseas Chinese during the Chinese Occupation of Northern Indochina (1945-1946), ''Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies'', Vol. 4: 129–139. * * * * * * * *Ungar, E. S. (1988). The Struggle Over the Chinese Community in Vietnam, 1946–1986, ''Pacific Affairs'', Vol. 60, Issue 4: 596–614. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Terminology

According to Churchman (2010), all endonyms and exonyms referring to the Vietnamese such as ''Viet'' (related to ancient Chinese geographical imagination), ''Kinh'' (related to medieval administrative designation), or ''Keeu'' and ''Kæw'' (derived from Jiāo 交, ancient Chinese toponym for Northern Vietnam, Old Chinese ''*kraw'') by Kra-Dai speaking peoples, are related to political structures or have common origins in ancient Chinese geographical imagination. Most of the time, the Austroasiatic-speaking ancestors of the modern Kinh under one single ruler might have assumed for themselves a similar or identical social self-designation inherent in the modern Vietnamese first-person pronoun ''ta'' (us, we, I) to differentiate themselves with other groups. In the older colloquial usage, ''ta'' corresponded to "ours" as opposed to "theirs", and during colonial time they were "''nước ta''" (our country) and "''tiếng ta''" (our language) in contrast to "''nước tây''" (western countries) and "''tiếng tây''" (western languages).Việt

The term "" (Yue) () in Early Middle Chinese was first written using the logogram, logograph "戉" for an axe (a homophone), in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty ( BC), and later as "越". At that time it referred to a people or chieftain to the northwest of the Shang.Theobald, Ulrich (2018"Shang Dynasty - Political History"

in ''ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art''. quote: "Enemies of the Shang state were called fang 方 "regions", like the Tufang 土方, which roamed the northern region of Shanxi, the Guifang, Guifang 鬼方 and Gongfang 𢀛方 in the northwest, the Qiang (historical people), Qiangfang 羌方, Suifang 繐方, Yuefang 戉方, Xuanfang 亘方 and Zhou dynasty, Zhoufang 周方 in the west, as well as the Dongyi, Yifang 夷方 and Renfang 人方 in the southeast." In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yangyue, a term later used for peoples further south. Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC Yue/Việt referred to the Yue (state), State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people. From the 3rd century BC the term was used for the non-Chinese populations of south and southwest China and northern Vietnam, with particular ethnic groups called Minyue, Ouyue (Vietnamese: Âu Việt), Luoyue (Vietnamese: Lạc Việt), etc., collectively called the Baiyue (Bách Việt, ; ). The term Baiyue/Bách Việt first appeared in the book ''Lüshi Chunqiu'' compiled around 239 BC. According to Ye Wenxian (1990), apud Wan (2013), the ethnonym of the Yuefang in northwestern China is not associated with that of the Baiyue in southeastern China. The late medieval period saw the rise of Vietnamese elites identified themselves with the ancient Yue in order to incline with 'an ancient origin', and that identity might have born by constructing traditions. By the 17th and 18th centuries AD, educated Vietnamese apparently referred to themselves as ''người Việt'' 𠊛越 (Viet people) or ''người Nam'' 𠊛南 (southern people).

Kinh

Beginning in the 10th and 11th centuries, a strand of Viet-Muong (northern Vietic language) with influence from a hypothetic Chinese dialect in northern Vietnam, dubbed as Annamese Middle Chinese, started to become what is now the Vietnamese language. Its speakers called themselves the "Kinh" people, meaning people of the "metropolitan" centered around the Red River Delta with Hanoi as its capital. Historic and modern Chữ Nôm scripture classically uses the Han character '京', pronounced "Jīng" in Mandarin, and "Kinh" with Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation. Other variants of Proto-Viet-Muong were driven from the lowlands by the Kinh and were called ''Trại'' (寨 Mandarin: ''Zhài''), or "outpost" people," by the 13th century. These became the modern Muong people, Mường people. According to Victor Lieberman, ''người Kinh'' (Chữ Nôm: 𠊛京) may be a colonial-era term for Vietnamese speakers inserted anachronistically into translations of pre-colonial documents, but literature on 18th century ethnic formation is lacking.History

Origins and pre-history

The forerunners of the ethnic Vietnamese were Vietic languages, Proto-Vietic people who descended from Proto-Austroasiatic people who may have originated from somewhere in Southern China, Yunnan, the Lingnan, or the Yangtze River, or mainland Southeast Asia, together with the Mon people, Monic, who settled further to the west and the Khmer people, Khmeric migrated further south. Most archaeologists and linguists, and other specialists like Sinologists and crop experts, believe that they arrived no later than 2000 BC bringing with them the practice of riverine agriculture and in particular the cultivation of wet rice.Blench, Roger. 2018Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic

In ''Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics'', 174-193. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Special Publication No. 3. University of Hawaii Press.Blench, Roger. 2017.

Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic

'. Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.Sidwell, Paul. 2015b. ''Phylogeny, innovations, and correlations in the prehistory of Austroasiatic''. Paper presented at the workshop ''Integrating inferences about our past: new findings and current issues in the peopling of the Pacific and South East Asia'', 22–23 June 2015, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany. Some linguists (James Chamberlain, Joachim Schliesinger) suggested that the Vietic-speaking people migrated from North Central Coast, North Central Region to the Red River Delta, which had originally been inhabited by Tai languages, Tai-Tai peoples, speakers. However, Michael Churchman found no records of population shifts in Jiaozhi (centered around the Red River Delta) in Chinese sources, indicating that a fairly stable population of Austroasiatic speakers, ancestral to modern Vietnamese, inhabited in the delta during the Han dynasty, Han-Tang dynasty, Tang periods. Other proposes that Northern Vietnam and Southern China were never homogeneous in term of ethnicity and languages, but peoples shared some customs. These ancient tribes did not have any kind of defined ethnic boundary and could not be described as "Vietnamese" (Kinh) in any satisfactory sense. Any attempt of identify an ethnic group in ancient Vietnam is problematized inaccurate. Another theory, based on linguistic diversity, locates the most probable homeland of the Vietic languages in modern-day Bolikhamsai Province and Khammouane Province in Laos as well as parts of Nghệ An Province and Quảng Bình Province in Vietnam. In the 1930s, clusters of Vietic-speaking communities were discovered in the hills of eastern Laos, are believed to be the earliest inhabitants of that region. Archaeogenetics demonstrated that before the Đông Sơn culture, Dong Son period, the Red River Delta's inhabitants were predominantly Austroasiatic: genetic data from Phùng Nguyên culture's Mán Bạc burial site (dated 1,800 BC) have close proximity to modern Austroasiatic speakers such as the Khmer people, Khmer and Mlabri people, Mlabri; meanwhile, "mixed genetics" from Đông Sơn culture's Núi Nấp site showed affinity to "Dai people, Dai from China, Kra-Dai languages, Tai-Kadai speakers from Thailand, and Austroasiatic speakers from Vietnam, including the Kinh people, Kinh". According to Vietnamese legend ''The Tale the Hồng Bàng Clan'' (''Hồng Bàng'' thị truyện) written in the 15th century, the first Vietnamese descended from the Vietnamese dragon, dragon lord Lạc Long Quân and the fairy Âu Cơ. They married and had one hundred eggs, from which hatched one hundred children. Their eldest son ruled as the Hùng king. The Hùng kings were claimed to be descended from the mythical figure Shen Nong.

Early history and Chinese rule

The earliest reference of the proto-Vietnamese in Chinese annals was the ''Lạc'' (Chinese: Luo), ''Lạc Việt'', or the Dongsonian, an ancient tribal confederacy of perhaps polyglot Austroasiatic language, Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai language, Kra-Dai speakers occupied the Red River Delta. The Lạc developed the metallurgical Dong Son Culture, Đông Sơn Culture and the Văn Lang chiefdom, ruled by the semi-mythical Hùng kings. To the south of the Dongsonians was the Sa Huỳnh culture, Sa Huỳnh Culture of the Austronesian people, Austronesian Chamic language, Chamic people. Around 400–200 BC, the Lạc came to contact with the Âu Việt (a splinter group of Tai people) and the Sinitic people from the north. According to a late third or early fourth century AD Chinese chronicle, the leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, conquered Văn Lang and deposed the last Hùng Duệ Vương, Hùng king. Having submissions of Lạc lords, Thục Phán proclaimed himself King An Dương of Âu Lạc kingdom.

In 179 BC, Zhao Tuo, a Chinese general who has established the Nanyue state in modern-day Southern China, annexed Âu Lạc, and began the Sino-Vietic interaction that lasted in a millennium. In 111 BC, the Han dynasty, Han Empire conquered Nanyue, brought the Northern Vietnam region under Han rule.

By the 7th century to 9th century AD, as the Tang Empire ruled over the region, historians such as Henri Maspero proposed that Vietnamese-speaking people became separated from other Vietic groups such as the Muong people, Mường and Chut people, Chứt due to heavier Chinese influences on the Vietnamese. Other argue that a Vietic migration from north central Vietnam to the Red River Delta in the seventh century replaced the original Tai-speaking inhabitants. In the mid-9th century, local rebels aided by Nanzhao tore the Tang Chinese rule to nearly collapse. The Tang reconquered the region in 866, causing half of the local rebels to flee into the mountains, which historians believe that was the separation between the Muong people, Mường and the Vietnamese took at the end of Tang rule in Vietnam. In 938, the Vietnamese leader Ngô Quyền who was a native of Thanh Hoa, Thanh Hóa, led Viet forces defeated the Chinese Southern Han armada at Battle of Bạch Đằng (938), Bạch Đằng River and proclaimed himself king, became the first Viet king of polity that now could be perceived as "Vietnamese".

The earliest reference of the proto-Vietnamese in Chinese annals was the ''Lạc'' (Chinese: Luo), ''Lạc Việt'', or the Dongsonian, an ancient tribal confederacy of perhaps polyglot Austroasiatic language, Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai language, Kra-Dai speakers occupied the Red River Delta. The Lạc developed the metallurgical Dong Son Culture, Đông Sơn Culture and the Văn Lang chiefdom, ruled by the semi-mythical Hùng kings. To the south of the Dongsonians was the Sa Huỳnh culture, Sa Huỳnh Culture of the Austronesian people, Austronesian Chamic language, Chamic people. Around 400–200 BC, the Lạc came to contact with the Âu Việt (a splinter group of Tai people) and the Sinitic people from the north. According to a late third or early fourth century AD Chinese chronicle, the leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, conquered Văn Lang and deposed the last Hùng Duệ Vương, Hùng king. Having submissions of Lạc lords, Thục Phán proclaimed himself King An Dương of Âu Lạc kingdom.

In 179 BC, Zhao Tuo, a Chinese general who has established the Nanyue state in modern-day Southern China, annexed Âu Lạc, and began the Sino-Vietic interaction that lasted in a millennium. In 111 BC, the Han dynasty, Han Empire conquered Nanyue, brought the Northern Vietnam region under Han rule.

By the 7th century to 9th century AD, as the Tang Empire ruled over the region, historians such as Henri Maspero proposed that Vietnamese-speaking people became separated from other Vietic groups such as the Muong people, Mường and Chut people, Chứt due to heavier Chinese influences on the Vietnamese. Other argue that a Vietic migration from north central Vietnam to the Red River Delta in the seventh century replaced the original Tai-speaking inhabitants. In the mid-9th century, local rebels aided by Nanzhao tore the Tang Chinese rule to nearly collapse. The Tang reconquered the region in 866, causing half of the local rebels to flee into the mountains, which historians believe that was the separation between the Muong people, Mường and the Vietnamese took at the end of Tang rule in Vietnam. In 938, the Vietnamese leader Ngô Quyền who was a native of Thanh Hoa, Thanh Hóa, led Viet forces defeated the Chinese Southern Han armada at Battle of Bạch Đằng (938), Bạch Đằng River and proclaimed himself king, became the first Viet king of polity that now could be perceived as "Vietnamese".

Medieval and early modern period

Ngô Quyền died in 944 and his kingdom collapsed into chaos and disturbances between twelve warlords and chiefs. In 968, a leader named Đinh Bộ Lĩnh united them and established the Đại Việt (Great Việt) kingdom. With assistance of powerful Buddhist monks, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh chose Hoa Lư in the southern edge of the Red River Delta as the capital instead of Tang-era Dai La, Đại La, adopted Chinese-style imperial titles, coinage, and ceremonies and tried to preserve the Chinese administrative framework. The independence of Đại Việt, according to Andrew Chittick, allows it "to develop its own distinctive political culture and ethnic consciousness." In 979 Dinh Bo Linh was assassinated, and Queen Duong Van Nga married with Dinh's general Le Hoan, appointed him as king. Disturbances in Đại Việt attracted attentions from neighbouring Chinese Song dynasty and Champa Kingdom, but they were defeated by Lê Hoàn. A Khmer inscription dated 987 records the arrival of Vietnamese merchants (Yuon) in Angkor. Chinese writers, Song Hao, Fan Chengda and Zhou Qufei, both reported that the inhabitants of Đại Việt "tattooed their foreheads, crossed feet, black teeth, bare feet and blacken clothing." The early 11th century Cham language, Cham inscription of Chiên Đàn, My Son, erected by king of Champa Harivarman IV (r. 1074–1080), mentions that he had offered Khmer (Kmīra/Kmir) and Viet (Yvan) prisoners as slaves to various local gods and temples of the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon.

Successive Vietnamese royal families from the Đinh, Lê, Lý dynasties and (Hoa people, Hoa)/Chinese ancestry Trần and Hồ dynasties ruled the kingdom peacefully from 968 to 1407. Emperor Lý Thái Tổ (r. 1009–1028) relocated the Vietnamese capital from Hoa Lư to Hanoi, the center of the Red River Delta in 1010. They practiced elitist marriage alliances between clans and nobles in the country. Mahayana Buddhism became state religion, Vietnamese music instruments, dancing and religious worshipping were influenced by both Cham, Indian and Chinese styles, while Confucianism slowly gained attention and influence. The earliest surviving corpus and text in Vietnamese language dated early 12th century, and surviving ''chữ nôm'' script inscriptions dated early 13th century, showcasing enormous influences of Chinese culture among the early Vietnamese elites.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty unsuccessful invaded Đại Việt in the 1250s and 1280s, though they sacked Hanoi. The Ming dynasty of China conquered Đại Việt in 1406, brought the Vietnamese under Chinese rule for 20 years, before they were driven out by Vietnamese leader Lê Lợi. The fourth grandson of Lê Lợi, king Lê Thánh Tông (r. 1460–1497), is considered one of the greatest monarchs in Vietnamese history. His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, military, education, and fiscal reforms he instituted, and a cultural revolution that replaced the old traditional aristocracy with a generation of literati scholars, adopted Confucianism, and transformed a Đại Việt from a Southeast Asian style polity to a bureaucratic state, and flourished. Thánh Tông's forces, armed with gunpowder weapons, overwhelmed the long-term rival Champa in 1471, then launched an unsuccessful invasion against the Laotian and Lan Na kingdoms in the 1480s.

Ngô Quyền died in 944 and his kingdom collapsed into chaos and disturbances between twelve warlords and chiefs. In 968, a leader named Đinh Bộ Lĩnh united them and established the Đại Việt (Great Việt) kingdom. With assistance of powerful Buddhist monks, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh chose Hoa Lư in the southern edge of the Red River Delta as the capital instead of Tang-era Dai La, Đại La, adopted Chinese-style imperial titles, coinage, and ceremonies and tried to preserve the Chinese administrative framework. The independence of Đại Việt, according to Andrew Chittick, allows it "to develop its own distinctive political culture and ethnic consciousness." In 979 Dinh Bo Linh was assassinated, and Queen Duong Van Nga married with Dinh's general Le Hoan, appointed him as king. Disturbances in Đại Việt attracted attentions from neighbouring Chinese Song dynasty and Champa Kingdom, but they were defeated by Lê Hoàn. A Khmer inscription dated 987 records the arrival of Vietnamese merchants (Yuon) in Angkor. Chinese writers, Song Hao, Fan Chengda and Zhou Qufei, both reported that the inhabitants of Đại Việt "tattooed their foreheads, crossed feet, black teeth, bare feet and blacken clothing." The early 11th century Cham language, Cham inscription of Chiên Đàn, My Son, erected by king of Champa Harivarman IV (r. 1074–1080), mentions that he had offered Khmer (Kmīra/Kmir) and Viet (Yvan) prisoners as slaves to various local gods and temples of the citadel of Tralauṅ Svon.

Successive Vietnamese royal families from the Đinh, Lê, Lý dynasties and (Hoa people, Hoa)/Chinese ancestry Trần and Hồ dynasties ruled the kingdom peacefully from 968 to 1407. Emperor Lý Thái Tổ (r. 1009–1028) relocated the Vietnamese capital from Hoa Lư to Hanoi, the center of the Red River Delta in 1010. They practiced elitist marriage alliances between clans and nobles in the country. Mahayana Buddhism became state religion, Vietnamese music instruments, dancing and religious worshipping were influenced by both Cham, Indian and Chinese styles, while Confucianism slowly gained attention and influence. The earliest surviving corpus and text in Vietnamese language dated early 12th century, and surviving ''chữ nôm'' script inscriptions dated early 13th century, showcasing enormous influences of Chinese culture among the early Vietnamese elites.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty unsuccessful invaded Đại Việt in the 1250s and 1280s, though they sacked Hanoi. The Ming dynasty of China conquered Đại Việt in 1406, brought the Vietnamese under Chinese rule for 20 years, before they were driven out by Vietnamese leader Lê Lợi. The fourth grandson of Lê Lợi, king Lê Thánh Tông (r. 1460–1497), is considered one of the greatest monarchs in Vietnamese history. His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, military, education, and fiscal reforms he instituted, and a cultural revolution that replaced the old traditional aristocracy with a generation of literati scholars, adopted Confucianism, and transformed a Đại Việt from a Southeast Asian style polity to a bureaucratic state, and flourished. Thánh Tông's forces, armed with gunpowder weapons, overwhelmed the long-term rival Champa in 1471, then launched an unsuccessful invasion against the Laotian and Lan Na kingdoms in the 1480s.

16th century – Modern period

With the death of Thánh Tông in 1497, the Đại Việt kingdom swiftly declined. Climate extremes, failing crops, regionalism and factionism tore the Vietnamese apart. From 1533 to 1790s, four powerful Vietnamese families: Mạc, Lê, Trịnh and Nguyễn, each ruled on their own domains. In northern Vietnam (Đàng Ngoài–outer realm), the Lê Emperors barely sat on the throne while the Trịnh lords held power of the court. The Mạc controlled northeast Vietnam. The Nguyễn lords ruled the southern polity of Đàng Trong (inner realm). Thousands of ethnic Vietnamese migrated south, settled on the old Cham lands. European missionaries and traders from the sixteenth century brought new religion, ideas and crops to the Vietnamese (Annamese). By 1639, there were 82,500 Catholic converts throughout Vietnam. In 1651, Alexandre de Rhodes published a 300-pages catechism in Latin and romanized-Vietnamese (''chữ Quốc Ngữ'') or the Vietnamese alphabet.

The Vietnamese Fragmentation period ended in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, who was aided by French mercenaries defeated the Tay Son dynasty, Tay Son kingdoms and reunited Vietnam. Through assimilation and brutal subjugation in the 1830s by Minh Mang, a large chunk of indigenous Cham people, Cham had been assimilated into Vietnamese. By 1847, the Vietnamese state under Emperor Thieu Tri, Thiệu Trị, people that identified them as "người Việt Nam" accounted for nearly 80 percent of the country's population. This demographic model continues to persist through the French Indochina, French Indochina in World War II, Japanese occupation and modern day.

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the French Cochinchina, French colony of Cochinchina. By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated into the two protectorates of Annam (French protectorate), Annam and Tonkin (French protectorate), Tonkin. The three Vietnamese entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887. The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society. A Western-style system of modern education introduced new humanism, humanist values into Vietnam.

With the death of Thánh Tông in 1497, the Đại Việt kingdom swiftly declined. Climate extremes, failing crops, regionalism and factionism tore the Vietnamese apart. From 1533 to 1790s, four powerful Vietnamese families: Mạc, Lê, Trịnh and Nguyễn, each ruled on their own domains. In northern Vietnam (Đàng Ngoài–outer realm), the Lê Emperors barely sat on the throne while the Trịnh lords held power of the court. The Mạc controlled northeast Vietnam. The Nguyễn lords ruled the southern polity of Đàng Trong (inner realm). Thousands of ethnic Vietnamese migrated south, settled on the old Cham lands. European missionaries and traders from the sixteenth century brought new religion, ideas and crops to the Vietnamese (Annamese). By 1639, there were 82,500 Catholic converts throughout Vietnam. In 1651, Alexandre de Rhodes published a 300-pages catechism in Latin and romanized-Vietnamese (''chữ Quốc Ngữ'') or the Vietnamese alphabet.

The Vietnamese Fragmentation period ended in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, who was aided by French mercenaries defeated the Tay Son dynasty, Tay Son kingdoms and reunited Vietnam. Through assimilation and brutal subjugation in the 1830s by Minh Mang, a large chunk of indigenous Cham people, Cham had been assimilated into Vietnamese. By 1847, the Vietnamese state under Emperor Thieu Tri, Thiệu Trị, people that identified them as "người Việt Nam" accounted for nearly 80 percent of the country's population. This demographic model continues to persist through the French Indochina, French Indochina in World War II, Japanese occupation and modern day.

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the French Cochinchina, French colony of Cochinchina. By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated into the two protectorates of Annam (French protectorate), Annam and Tonkin (French protectorate), Tonkin. The three Vietnamese entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887. The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society. A Western-style system of modern education introduced new humanism, humanist values into Vietnam.

Despite having a long recorded history of the Vietnamese language and people, the identification and distinction of 'ethnic Vietnamese' or ethnic Kinh, as well as other ethnic groups in Vietnam, were only begun by colonial administration in the late 19th and early 20th century. Following colonial government's efforts of ethnic classificating, nationalism, especially ethnic nationalism, ethnonationalism and eugenic Social Darwinism were encouraged among the new Vietnamese intelligentsias discourse. Ethnic tensions sparked by Vietnamese ethnonationalism peaked during the late 1940s at the beginning phase of the First Indochina War (1946–1954), which resulted in violences between Khmer and Vietnamese in the Mekong Delta. Further North Vietnam's Soviet-style social integrational and ethnic classification, tried to build an image of Diversity under the harmony of Socialism, promoting the idea of the Vietnamese nation as a 'great single family' comprised by many different ethnic groups, and Vietnamese ethnic chauvinism was officially discouraged.

Despite having a long recorded history of the Vietnamese language and people, the identification and distinction of 'ethnic Vietnamese' or ethnic Kinh, as well as other ethnic groups in Vietnam, were only begun by colonial administration in the late 19th and early 20th century. Following colonial government's efforts of ethnic classificating, nationalism, especially ethnic nationalism, ethnonationalism and eugenic Social Darwinism were encouraged among the new Vietnamese intelligentsias discourse. Ethnic tensions sparked by Vietnamese ethnonationalism peaked during the late 1940s at the beginning phase of the First Indochina War (1946–1954), which resulted in violences between Khmer and Vietnamese in the Mekong Delta. Further North Vietnam's Soviet-style social integrational and ethnic classification, tried to build an image of Diversity under the harmony of Socialism, promoting the idea of the Vietnamese nation as a 'great single family' comprised by many different ethnic groups, and Vietnamese ethnic chauvinism was officially discouraged.

Religions

According to the 2019 Census, the religious demographics of Vietnam are as follows: *86.32% Vietnamese folk religion or non religious *6.1% Catholic Church in Vietnam, Catholicism *4.79% Buddhism (mainly Mahayana) *1.02% Hòa Hảo, Hoahaoism *1% Protestantism *<1% Caodaism *0.77 Others It is worth noting here that the data is highly skewered, as a large majority of Vietnamese may declare themselves atheist, yet practice forms of traditional folk religion or Mahayana Buddhism. Estimates for the year 2010 published by the Pew Research Center: *Vietnamese folk religion, 45.3% *Unaffiliated, 29.6% *Buddhism, 16.4% *Christianity, 8.2% *Other, 0.5%Diaspora

Originally from northern Vietnam and southern China, the Vietnamese have expanded south and conquered much of the land belonging to the former Champa Kingdom and Khmer Empire over the centuries. They are the dominant ethnic group in most provinces of Vietnam, and constitute a small percentage of the population in neighbouring Cambodia.

Beginning around the sixteenth century, groups of Vietnamese migrated to Cambodia and China for commerce and political purposes. Descendants of Vietnamese migrants in China form the Gin people, Gin ethnic group in the country and primarily reside in and around Guangxi Province. Vietnamese form the largest ethnic minority group in Cambodia, at 5% of the population. Under the Khmer Rouge, they were heavily persecuted and survivors of the regime largely fled to Vietnam.

During French Indochina, French colonialism, Vietnam was regarded as the most important colony in Asia by the French colonial powers, and the Vietnamese had a higher social standing than other ethnic groups in French Indochina. As a result, educated Vietnamese were often trained to be placed in colonial government positions in the other Asian French colonies of Laos and Cambodia rather than locals of the respective colonies. There was also a significant representation of Vietnamese students in France during this period, primarily consisting of members of the elite class. A large number of Vietnamese also migrated to France as workers, especially during World War I and World War II, when France recruited soldiers and locals of its colonies to help with war efforts in Metropolitan France. The wave of migrants to France during World War I formed the first major presence of Vietnamese people in France and the Western world.La Diaspora Vietnamienne en France un cas particulier

Originally from northern Vietnam and southern China, the Vietnamese have expanded south and conquered much of the land belonging to the former Champa Kingdom and Khmer Empire over the centuries. They are the dominant ethnic group in most provinces of Vietnam, and constitute a small percentage of the population in neighbouring Cambodia.

Beginning around the sixteenth century, groups of Vietnamese migrated to Cambodia and China for commerce and political purposes. Descendants of Vietnamese migrants in China form the Gin people, Gin ethnic group in the country and primarily reside in and around Guangxi Province. Vietnamese form the largest ethnic minority group in Cambodia, at 5% of the population. Under the Khmer Rouge, they were heavily persecuted and survivors of the regime largely fled to Vietnam.

During French Indochina, French colonialism, Vietnam was regarded as the most important colony in Asia by the French colonial powers, and the Vietnamese had a higher social standing than other ethnic groups in French Indochina. As a result, educated Vietnamese were often trained to be placed in colonial government positions in the other Asian French colonies of Laos and Cambodia rather than locals of the respective colonies. There was also a significant representation of Vietnamese students in France during this period, primarily consisting of members of the elite class. A large number of Vietnamese also migrated to France as workers, especially during World War I and World War II, when France recruited soldiers and locals of its colonies to help with war efforts in Metropolitan France. The wave of migrants to France during World War I formed the first major presence of Vietnamese people in France and the Western world.La Diaspora Vietnamienne en France un cas particulier(in French)

When Vietnam gained its independence from France in 1954, a number of Vietnamese loyal to the colonial government also migrated to France. During the partition of Vietnam into North Vietnam, North and South Vietnam, South, a number of South Vietnamese students also arrived to study in France, along with individuals involved in commerce for trade with France, which was a principal economic partner with South Vietnam.

When Vietnam gained its independence from France in 1954, a number of Vietnamese loyal to the colonial government also migrated to France. During the partition of Vietnam into North Vietnam, North and South Vietnam, South, a number of South Vietnamese students also arrived to study in France, along with individuals involved in commerce for trade with France, which was a principal economic partner with South Vietnam.

Forced repatriation in 1970 and deaths during the Khmer Rouge era reduced the Vietnamese Cambodian, Vietnamese population in Cambodia from between 250,000 and 300,000 in 1969 to a reported 56,000 in 1984.

The Fall of Saigon and end of the Vietnam War prompted the start of the Vietnamese diaspora, which saw millions of Vietnamese fleeing the country from the new communist regime. Recognizing an international humanitarian crisis, many countries accepted Vietnamese refugees, primarily the United States, France, Australia and Canada. Meanwhile, under the new communist regime, tens of thousands of Vietnamese were sent to work or study in Eastern Bloc countries of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe as development aid to the Vietnamese government and for migrants to acquire skills that were to be brought home to help with development. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a vast majority of these overseas Vietnamese decided to remain in their host nations.

Forced repatriation in 1970 and deaths during the Khmer Rouge era reduced the Vietnamese Cambodian, Vietnamese population in Cambodia from between 250,000 and 300,000 in 1969 to a reported 56,000 in 1984.

The Fall of Saigon and end of the Vietnam War prompted the start of the Vietnamese diaspora, which saw millions of Vietnamese fleeing the country from the new communist regime. Recognizing an international humanitarian crisis, many countries accepted Vietnamese refugees, primarily the United States, France, Australia and Canada. Meanwhile, under the new communist regime, tens of thousands of Vietnamese were sent to work or study in Eastern Bloc countries of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe as development aid to the Vietnamese government and for migrants to acquire skills that were to be brought home to help with development. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a vast majority of these overseas Vietnamese decided to remain in their host nations.

DNA and genetics analysis

Anthropometry

Stephen Pheasant (1986), who taught anatomy, biomechanics and Human factors and ergonomics, ergonomics at the Royal Free Hospital and the University College London, University College, London, said that East Asians, East Asian and Southeast Asian people have proportionately shorter lower limbs than White people, European and black people, black African people. Pheasant said that the proportionately short lower limbs of East Asian and Southeast Asian people is a difference that is most characterized in Japanese people, less characterized in Koreans, Korean and Han Chinese, Chinese people, and least characterized in Vietnamese and Thai people. Nguyen Manh Lien (1998) of the Vietnam Atomic Energy Commission indicated the average sitting height to body height ratios of Vietnamese 17-19 year olds to be 52.59% for males and 52.57% for females. Neville Moray (2005) indicated that modifications in basic cockpit geometry are required to accommodate Genetic and anthropometric studies on Japanese people, Japanese and Vietnamese Aircraft pilot, pilots. Moray said that the Japanese have longer torsos and a higher shoulder point than the Vietnamese, but the Japanese have about similar arm lengths to the Vietnamese, so the Aircraft flight control system, control stick would have to be moved 8 cm closer to the pilot for the Japanese and 7 cm closer to the pilot for the Vietnamese. Moray said that, due to having shorter legs than Americans (of European Americans, European and African Americans, African descent), Aircraft flight control system, rudder pedals must be moved closer to the pilot by 10 cm for the Japanese and 12 cm for the Vietnamese.Craniometry

Ann Kumar (1998) said that Michael Pietrusewsky (1992) said that, in a craniometric study, Borneo, Vietnam, Sulu, Java, and Sulawesi are closer to Japan, in that order, than Mongols, Mongolian and Han Chinese, Chinese populations are close to Japan. In the craniometric study, Michael Pietrusewsky (1992) said that, even though Japanese people Cluster analysis, cluster with Mongolians, Chinese and Southeast Asians in a larger Asian cluster, Japanese people are more closely aligned with several Mainland Southeast Asia, mainland and Maritime Southeast Asia, island Southeast Asian samples than with Mongolians and Chinese. Hirofumi Matsumura et al. (2001) and Hideo Matsumoto et al. (2009) said that the Japanese people, Japanese and Vietnamese people are regarded to be a mix of Northeast Asians and Southeast Asians who are related to today Austronesian peoples. But the amount of northern genetics is higher in Japanese people compared to Vietnamese who are closer to other Southeast Asians (Thai people, Thai or Bamar people). Bradley J. Adams, a forensic anthropology, forensic anthropologist in the Office of Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York, said that Vietnamese people could be classified as Mongoloid. A 2009 book about forensic anthropology said that Vietnamese skulls are more Gracility, gracile and less Sexual dimorphism, sexually dimorphic than the skulls of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans. Matsumura and Hudson (2005) said that a broad comparison of dental traits indicated that modern Vietnamese and other modern Southeast Asians derive from a northern source, supporting the Two layer hypothesis, immigration hypothesis, instead of regional continuity hypothesis, as the model for the origins of modern Southeast Asians.Genetics

Vietnamese show a close genetic relationship with other Southeast Asians. The reference population for Vietnamese (Kinh) used in the Genographic Project#Geno 2.0 Next Generation, Geno 2.0 Next Generation is 83% Southeast Asia & Oceania, 12% Eastern Asia and 3% Southern Asia. Jin Han-jun et al. (1999) said that the Human mitochondrial genetics, mtDNA 9‐Base pair, bp deletion frequencies in the wikt:intergenic, intergenic ''Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II, COII/Transfer RNA, tRNALysine, Lys'' region for Vietnamese (23.2%) and Indonesians (25.0%), which are the two populations constituting Southeast Asians in the study, are relatively high frequencies when compared to the 9-bp deletion frequencies for Mongols, Mongolians (5.1%), Han Chinese, Chinese (14.2%), Japanese people, Japanese (14.3%) and Koreans (15.5%), which are the four populations constituting East Asians in the study. The study said that these 9-bp deletion frequencies are consistent with earlier surveys which showed that 9-bp deletion frequencies increase going from Japan to mainland Asia to the Malay Peninsula, which is supported by the following studies: Horai et al. (1987); Hertzberg et al. (1989); Stoneking & Wilson (1989); Horai (1991); Ballinger et al. (1992); Hanihara et al. (1992); and Chen et al. (1995). The Genetic distance#Cavalli-Sforza chord distance, Cavalli-Sforza's chord genetic distance (4D), from Cavalli-Sforza & Bodmer (1971), which is based on the allele frequencies of the intergenic ''COII/tRNALys'' region, between Vietnamese and other East Asian populations in the study, from least to greatest, are as follows: Vietnamese to Indonesians, Indonesian (0.0004), Vietnamese to Han Chinese, Chinese (0.0135), Vietnamese to Japanese people, Japanese (0.0153), Vietnamese to Koreans, Korean (0.0265) and Vietnamese to Mongols, Mongolian (0.0750).Jin, Han-jun et al. (1999). Distribution of length variation of the mtDNA 9‐bp motif in the intergenic COII/tRNALys region in East Asian populations. ''Korean Journal of Biological Sciences 3''(4). Pages 395 & 396. Retrieved March 2, 2018, frolink to the article's abstract.

/ref> Kim Wook et al. (2000) said that, genetically, Vietnamese people more probably clustered with East Asians of which the study analyzed DNA samples of Chinese people, Chinese, Japanese people, Japanese, Koreans and Mongols, Mongolians rather than with Southeast Asians of which the study analyzed DNA samples of Indonesians, Filipinos, Thai people, Thais and Vietnamese. The study said that Vietnamese people were the only population in the study's Phylogenetics, phylogenetic analysis that did not reflect a sizable genetic difference between East Asian and Southeast Asian populations. The study said that the likely reason for Vietnamese people more probably clustering with East Asians was genetic drift and distinct Founder effect, founder populations. The study said that the alternative reason for Vietnamese people more probably clustering with East Asians is a recent Colonisation (biology), range expansion from South China. The study mentioned that the majority of its Vietnamese DNA samples were from Hanoi which is the closest region to South China. Schurr & Wallace (2002) said that Vietnamese people display genetic similarities with certain peoples from Malaysia. The study said that the aboriginal groups from Malaysia, the Orang Asli, are somewhat genetically intermediate between Malay people and Vietnamese. The study said that Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup, mtDNA haplogroup Haplogroup F (mtDNA), F is present at its highest frequency in Vietnamese and a high frequency of this haplogroup is also present in the Orang Asli, a people with whom Vietnamese have a linguistic connection (Austroasiatic languages).Schurr, Theodore G. & Wallace, Douglas C. (2002). Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Southeast Asian Populations. ''Human Biology (journal), Human Biology, 74''(3). Pages 433, 439, 446, 447 & 448. Retrieved January 7, 2018, fro

link.

/ref> Jung Jongsun et al. (2010) said that genetic structure analysis found significant admixture in "''Vietnamese (or Khmer people, Cambodian) with unknown Southern original settlers.''" The study said that it used Cambodians and Vietnamese to represent "Southern people," and the study used Cambodia (Khmer people, Khmer) and Vietnam (Kinh) as its populations for "South Asia." The study said that Chinese people are located between Koreans, Korean and Vietnamese people in the study's Gene mapping, genome map. The study also said that Vietnamese people are located between Chinese and Cambodian people in the study's genome map. He Jun-dong et al. (2012) did a principal component analysis using the Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, NRY haplogroup distribution frequencies of 45 populations, and the second principal component showed a close affinity between Kinh and Vietnamese who were most likely Kinh with populations from mainland South China, southern China because of the high frequency of NRY haplogroup Haplogroup O-K18, O-M88. The study said that Kinh often have NRY haplogroup Haplogroup O-M122, O-M7 which is the characteristic Chinese haplogroup. Out of the study's Sample (statistics), sample of seventy-six Kinh NRY haplogroups, twenty-three haplogroups (30.26%) were O-M88 and eight haplogroups (10.53%) were O-M7. The study said that, in ancient northern Vietnam, it is suggested that there has been considerable assimilation of inhabitants from present-day southern China through immigration into the Kinh people.He, Jun-dong et al. (2012). Patrilineal Perspective on the Austronesian Diffusion in Mainland Southeast Asia. In ''PLOS One, PLoS 7''(5), Page 7. Retrieved December 14, 2017, fro

link.