Festival of Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian

The first idea for an exhibition in 1951 came from the Royal Society of Arts in 1943, which considered that an international exhibition should be held to commemorate the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1945, the government appointed a committee under Lord Ramsden to consider how exhibitions and fairs could promote exports. When the committee reported a year later, it was decided not to continue with the idea of an international exhibition because of its cost at a time when reconstruction was a high priority.

The first idea for an exhibition in 1951 came from the Royal Society of Arts in 1943, which considered that an international exhibition should be held to commemorate the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1945, the government appointed a committee under Lord Ramsden to consider how exhibitions and fairs could promote exports. When the committee reported a year later, it was decided not to continue with the idea of an international exhibition because of its cost at a time when reconstruction was a high priority.

Design Council's files

relating to the planning of the festival.

Festival Ship ''Campania'',: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

*Southampton (4 May – 14 May)

*Dundee (18 May – 26 May)

*Newcastle (30 May – 16 June)

*Hull (20 June – 30 June)

*Plymouth (5 July – 14 July)

*Bristol (18 July – 28 July)

*Cardiff (31 July – 11 August)

*Belfast (15 August – 1 September)

*Birkenhead (5 September – 14 September)

*Glasgow (18 September – 6 October)

Land Travelling Exhibition : England

*Manchester (5 May – 26 May)

*Leeds (23 June – 14 July)

*Birmingham (4 August — 25 August)

*Nottingham (15 September – 6 October)

Festival Ship ''Campania'',: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

*Southampton (4 May – 14 May)

*Dundee (18 May – 26 May)

*Newcastle (30 May – 16 June)

*Hull (20 June – 30 June)

*Plymouth (5 July – 14 July)

*Bristol (18 July – 28 July)

*Cardiff (31 July – 11 August)

*Belfast (15 August – 1 September)

*Birkenhead (5 September – 14 September)

*Glasgow (18 September – 6 October)

Land Travelling Exhibition : England

*Manchester (5 May – 26 May)

*Leeds (23 June – 14 July)

*Birmingham (4 August — 25 August)

*Nottingham (15 September – 6 October)

Construction of the South Bank site opened up a new public space, including a riverside walkway, where previously there had been warehouses and working-class housing. The layout of the South Bank site was intended to showcase the principles of

Construction of the South Bank site opened up a new public space, including a riverside walkway, where previously there had been warehouses and working-class housing. The layout of the South Bank site was intended to showcase the principles of

''Architect'': Misha Black

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display Design'': James Holland

The exhibits comprised:

*The Land of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Design'': V.Rotter.)

*The Natural Scene (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion)

*The Country. (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Conveners'': A. S. Thomas, Peter B. Collins. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion.)

*Minerals of the Island (''Architects'': Architects' Co-operative Partnership. ''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Beverley Pick.)

*Power and Production (''Architects'':

''Architect'': Misha Black

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display Design'': James Holland

The exhibits comprised:

*The Land of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Design'': V.Rotter.)

*The Natural Scene (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion)

*The Country. (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Conveners'': A. S. Thomas, Peter B. Collins. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion.)

*Minerals of the Island (''Architects'': Architects' Co-operative Partnership. ''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Beverley Pick.)

*Power and Production (''Architects'':

''Architect'': Ralph Tubbs

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display'': Design Research Unit

The exhibits focused on scientific discovery. They included:

*The Land. (''Theme Convener''. Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Stefan Buzas and Ronald Sandiford.)

*The Earth. (''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Robert Gutman.)

*Polar. (''Theme Convener'': Quinitin Riley and L. P. Macnair. ''Display Designer'': Jock Kinneir.)

*Sea. (''Theme Conveners'': C. Hamilton Ellis and Nigel Clayton. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Ellis Miles.)

*Sky. (''Theme Convener'': Arthur Garratt. ''Display Designer'': Ronald Sandiford.)

*Outer Space. (''Theme Convener'': Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Eric Towell.)

*The Living World. (''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Stirling Craig.)

*The Physical World. (''Theme Conveners'': Arthur Garratt and Jan Read. ''Display Designers'': Ronald Ingles and Clifford Hatts.)

''Architect'': Ralph Tubbs

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display'': Design Research Unit

The exhibits focused on scientific discovery. They included:

*The Land. (''Theme Convener''. Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Stefan Buzas and Ronald Sandiford.)

*The Earth. (''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Robert Gutman.)

*Polar. (''Theme Convener'': Quinitin Riley and L. P. Macnair. ''Display Designer'': Jock Kinneir.)

*Sea. (''Theme Conveners'': C. Hamilton Ellis and Nigel Clayton. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Ellis Miles.)

*Sky. (''Theme Convener'': Arthur Garratt. ''Display Designer'': Ronald Sandiford.)

*Outer Space. (''Theme Convener'': Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Eric Towell.)

*The Living World. (''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Stirling Craig.)

*The Physical World. (''Theme Conveners'': Arthur Garratt and Jan Read. ''Display Designers'': Ronald Ingles and Clifford Hatts.)

''Architect'': Hugh Casson

''Theme'': M.Hartland Thomas

''Display Design'': James Gardner

The exhibits comprised:

*The People of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Jacquetta Hawkes. ''Display Design'': James Gardner.)

*The Lion and the Unicorn (''Architects'': R. D. Russell, Robert Goodden. ''Theme Conveners'': Hubert Phillips and Peter Stucley. ''Display Designers'': Robert Goodden, R. D. Russell and Richard Guyatt. ''Commentary'': Laurie Lee.)

*Homes and Gardens. (''Architects'': Bronek Katz and Reginald Vaughan. ''Theme Conveners'': A.Hippisley Coxe and S. D. Cooke.)

*The New Schools. (''Architects'': Maxwell Fry and

''Architect'': Hugh Casson

''Theme'': M.Hartland Thomas

''Display Design'': James Gardner

The exhibits comprised:

*The People of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Jacquetta Hawkes. ''Display Design'': James Gardner.)

*The Lion and the Unicorn (''Architects'': R. D. Russell, Robert Goodden. ''Theme Conveners'': Hubert Phillips and Peter Stucley. ''Display Designers'': Robert Goodden, R. D. Russell and Richard Guyatt. ''Commentary'': Laurie Lee.)

*Homes and Gardens. (''Architects'': Bronek Katz and Reginald Vaughan. ''Theme Conveners'': A.Hippisley Coxe and S. D. Cooke.)

*The New Schools. (''Architects'': Maxwell Fry and

An unusual cigar-shaped aluminium-clad steel tower supported by cables, the Skylon was the "Vertical Feature" that was an abiding symbol of the Festival of Britain. The base was nearly 15 metres (50 feet) from the ground, with the top nearly 90 metres (300 feet) high. The frame was clad in aluminium louvres lit from within at night. It was designed by

An unusual cigar-shaped aluminium-clad steel tower supported by cables, the Skylon was the "Vertical Feature" that was an abiding symbol of the Festival of Britain. The base was nearly 15 metres (50 feet) from the ground, with the top nearly 90 metres (300 feet) high. The frame was clad in aluminium louvres lit from within at night. It was designed by

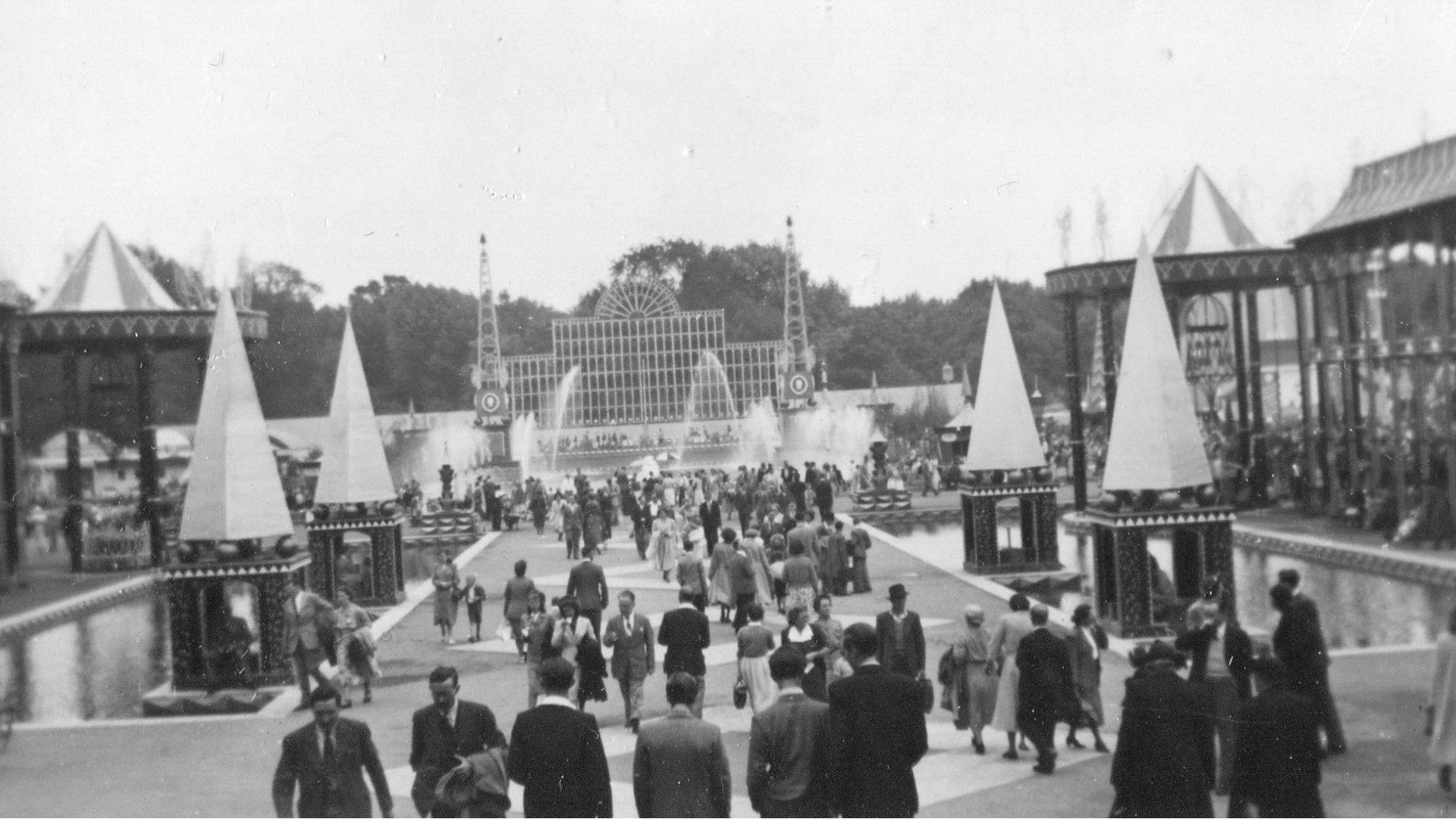

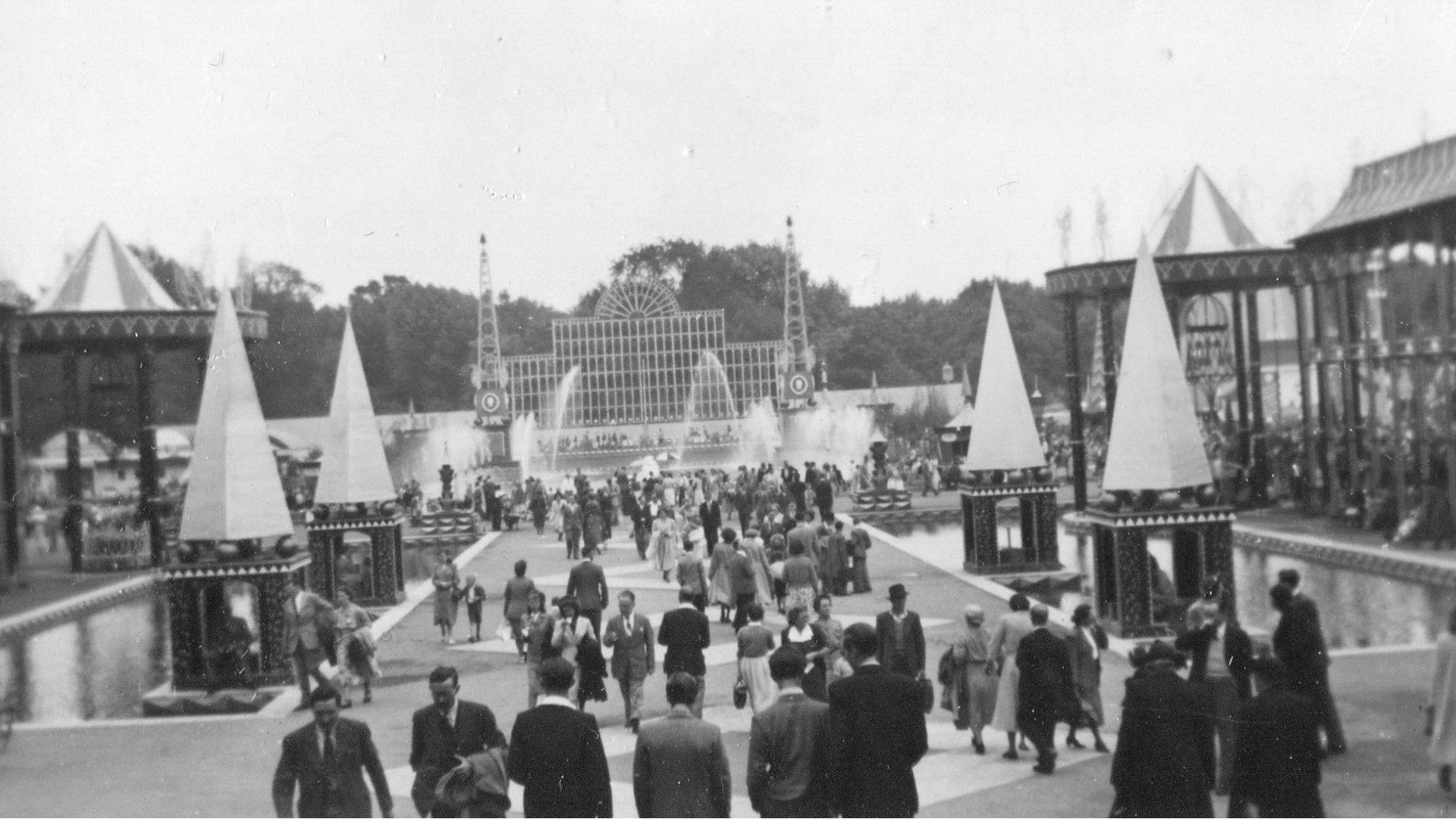

The Festival Pleasure Gardens were created to present a lighter side of the Festival of Britain. They were erected in

The Festival Pleasure Gardens were created to present a lighter side of the Festival of Britain. They were erected in

coffee bars

and office blocks of the fifties. Harlow new town and the rebuilding of There was an exhibition about building research, town planning and architecture, the "Live architecture" exhibit of buildings, open spaces and streets in the

There was an exhibition about building research, town planning and architecture, the "Live architecture" exhibit of buildings, open spaces and streets in the

''Exhibition of Science''

The first part of the exhibition showed the physical and chemical nature of matter and the behaviour of elements and molecules. The second part, "The Structure of Living Things", dealt with plants and animals. The third part, "Stop Press", showed some of the latest topics of research in science and their emergence from the ideas illustrated in the earlier sections of the exhibition. They included "the penetrating rays which reach us from outer space, what goes on in space and in the stars, and a range of subjects from the electronic brain to the processes and structures on which life is based." It has been claimed that "the Festival of Britain created a confusion at the heart of subsequent discussions amongst administrators and educationalists concerning the place science should have in British life and thought as a whole (particularly education), and its role in Britain’s post-war greatness."

There were hundreds of events associated with the Festival, some of which were:

*The selection of

There were hundreds of events associated with the Festival, some of which were:

*The selection of

60th Anniversary of the Festival of Britain 2011

Retrieved May 2015 They can be searched via th

Visual Arts Data Service

(VADS).

online

* Goodden, Henrietta. ''The Lion and the Unicorn: symbolic architecture for the Festival of Britain 1951'' (Norwich, Unicorn Press, 2011), 144 pp. * Hillier, Bevis, and Mary Banham, eds. ''A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain: 1951'' (Thames and Hudson, 1976). * Hoon, Will. ''The 1951 Festival of Britain: A Living Legacy'' (Department of History of Art and Design, Manchester Metropolitan University, 1996). * Leventhal, F. M. "'A Tonic to the Nation': The Festival of Britain, 1951." ''Albion'' 27#3 (1995): 445–453

in JSTOR

* Lew, Nathaniel G. ''Tonic to the Nation: Making English Music in the Festival of Britain'' (Routledge, 2016). * Rennie, Paul, ''Festival of Britain 1951'' (London: Antique Collectors Club, Ltd., 2007). * Richardson, R. C. "Cultural Mapping in 1951: The Festival of Britain Regional Guidebooks" ''Literature & History'' 24#2 (2015) pp 53–72. * Turner, Barry. ''Beacon for change. How the 1951 Festival of Britain shaped the modern age'' (London, Aurum Press, 2011). * Weight, Richard. ''Patriots: National Identity in Britain, 1940–2000'' (London: Pan Macmillan, 2013), pp 193–208. * Wilton, Iain. "'A galaxy of sporting events': sport's role and significance in the Festival of Britain, 1951." ''Sport in History'' 36#4 (2016): 459–476.

George Simner, "Festival of Britain", ''The Observer''

, e-learning module by the Design Council Archives

Festival of Britain

(Design Council Archive, University of Brighton)

The Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain Society

The Festival of Britain – Exploring 20th century London

https://www.flickr.com/groups/southbankcentre/

(A Flickr group dedicated to pictures of the Southbank Centre) * http://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/festival-memories/see-your-memories (Memories of the Festival of Britain compiled by the Southbank Centre)

of a talk by Robert Anderson on the development of the Exhibition of Science as part of the Festival of Britain *

Festival In London (1951)

*

Brief City (1952)

* ttp://ornamentalpassions.blogspot.com/2010/10/219-oxford-street-w1.html 219 Oxford Street, with images of the Festivalbr>Collection of fabrics inspired by crystallography held by the Science Museum, London

wit

souvenir book from the Festival.

*Archive of the Festival of Britain held by th

Archives of Art and Design

Victoria and Albert Museum, London *Assorted film reports are available via the British Pathé website http://www.britishpathe.com/workspaces/rgoldthorpe/Festival-of-Britain {{Authority control Design 1951 in the United Kingdom 1951 in London World's fairs in London History of the London Borough of Lambeth British design exhibitions Arts festivals in the United Kingdom World's fairs in Glasgow National exhibitions

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan

Kenneth Owen Morgan, Baron Morgan, (born 16 May 1934) is a Welsh historian and author, known especially for his writings on modern British history and politics and on Welsh history. He is a regular reviewer and broadcaster on radio and televisi ...

says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

Labour cabinet member Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

was the prime mover; in 1947 he started with the original plan to celebrate the centennial of the Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

. However, it was not to be another World Fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

, for international themes were absent, as was the British Commonwealth. Instead the 1951 festival focused entirely on Britain and its achievements; it was funded chiefly by the government, with a budget of £12 million. The Labour government was losing support and so the implicit goal of the festival was to give the people a feeling of successful recovery from the war's devastation, as well as promoting British science, technology, industrial design, architecture and the arts.

The Festival's centrepiece was in London on the South Bank of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

. There were events in Poplar (Architecture – Lansbury Estate

The Lansbury Estate is a large, historic council housing estate in Poplar and Bromley-by-Bow in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is named after George Lansbury, a Poplar councillor and Labour Party MP.

History

Lansbury Estate is one ...

), Battersea (the Festival Pleasure Gardens), South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

(Science) and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

(Industrial Power). Festival celebrations took place in Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

, Stratford-upon-Avon, Bath, Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

, Bournemouth, York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Aldeburgh

Aldeburgh ( ) is a coastal town in the county of Suffolk, England. Located to the north of the River Alde. Its estimated population was 2,276 in 2019. It was home to the composer Benjamin Britten and remains the centre of the international Alde ...

, Inverness, Cheltenham, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

and elsewhere,''The Festival of Britain'' (Official Book of the Festival of Britain 1951). HMSO, 1951. and there were touring exhibitions by land and sea.

The Festival became a "beacon for change" that proved immensely popular with thousands of elite visitors and millions of popular ones. It helped reshape British arts, crafts, designs and sports for a generation. Journalist Harry Hopkins highlights the widespread impact of the "Festival style". They called it "Contemporary". It was:

Conception and organisation

The first idea for an exhibition in 1951 came from the Royal Society of Arts in 1943, which considered that an international exhibition should be held to commemorate the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1945, the government appointed a committee under Lord Ramsden to consider how exhibitions and fairs could promote exports. When the committee reported a year later, it was decided not to continue with the idea of an international exhibition because of its cost at a time when reconstruction was a high priority.

The first idea for an exhibition in 1951 came from the Royal Society of Arts in 1943, which considered that an international exhibition should be held to commemorate the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1945, the government appointed a committee under Lord Ramsden to consider how exhibitions and fairs could promote exports. When the committee reported a year later, it was decided not to continue with the idea of an international exhibition because of its cost at a time when reconstruction was a high priority. Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Minis ...

took charge for the Labour government and decided instead to hold a series of displays about the arts, architecture, science, technology and industrial design,Cox, Ian, ''The South Bank Exhibition: A guide to the story it tells'', H.M.S.O., 1951 under the title "Festival of Britain 1951". Morrison insisted there be no politics, explicit or implicit. As a result, Labour-sponsored programs such as nationalisation, universal health care and working-class housing were excluded; instead, what was allowed was town planning, scientific progress, and all sorts of traditional and modern arts and crafts.Leventhal, "A Tonic to the Nation" p 447

Much of London lay in ruins, and models of redevelopment were needed. The Festival was an attempt to give Britons a feeling of recovery and progress and to promote better-quality design in the rebuilding of British towns and cities. The Festival of Britain described itself as "one united act of national reassessment, and one corporate reaffirmation of faith in the nation's future." Gerald Barry, the Festival Director, described it as "a tonic to the nation".

A Festival Council to advise the government was set up under General Lord Ismay. Responsibility for organisation devolved upon the Lord President of the Council, Herbert Morrison, the deputy leader of the Labour Party, who had been London County Council leader. He appointed a Great Exhibition Centenary Committee, consisting of civil servants, who were to define the framework of the Festival and to liaise between government departments and the festival organisation. In March 1948, a Festival Headquarters was set up, which was to be the nucleus of the Festival of Britain Office, a government department with its own budget. Festival projects in Northern Ireland were undertaken by the government of Northern Ireland.

Associated with the Festival of Britain Office were the Arts Council of Great Britain, the Council of Industrial Design, the British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery (United Kingdom), National Lot ...

and the National Book League. In addition, a Council for Architecture and a Council for Science and Technology were specially created to advise the Festival Organisation and a Committee of Christian Churches was set up to advise on religion. Government grants were made to the Arts Council, the Council of Industrial Design, the British Film Institute and the National Museum of Wales

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

for work undertaken as part of the Festival.

Gerald Barry had operational charge. A long-time editor with left-leaning, middle-brow views, he was energetic and optimistic, with an eye for what would be popular, and a knack on how to motivate others. Unlike Morrison, Barry was not seen as a Labour ideologue. Barry selected the next rank, giving preference to young architects and designers who had collaborated on exhibitions for the wartime Ministry of Information. They thought along the same lines socially and aesthetically, as middle-class intellectuals with progressive sympathies. Thanks to Barry, a collegial sentiment prevailed that minimised stress and delay.

Displays

The arts were displayed in a series of country-wide musical and dramatic performances. Achievements in architecture were presented in a new neighbourhood, the Lansbury Estate, planned, built and occupied in the Poplar district of London. The Festival's centrepiece was the South Bank Exhibition, in the Waterloo area of London, which demonstrated the contribution made by British advances in science, technology and industrial design, displayed, in their practical and applied form, against a background representing the living, working world of the day. There were other displays elsewhere, each intended to be complete in itself, yet each part of the one single conception. Festival Pleasure Gardens were set up in Battersea, about three miles up river from the South Bank. Heavy engineering was the subject of an Exhibition of Industrial Power in Glasgow. Certain aspects of science, which did not fall within the terms of reference of the South Bank Exhibition, were displayed in South Kensington. Linen technology and science in agriculture were exhibited in "Farm and Factory" in Belfast. A smaller exhibition of the South Bank story was put on in the Festival ship ''Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

'', which toured the coast of Britain throughout the summer of 1951, and on land there was a travelling exhibition of industrial design.

The University of Brighton Design Archives

The University of Brighton Design Archives centres on British and global design organisations of the twentieth century. It is located within the University of Brighton Grand Parade campus in the heart of Brighton and is an international research r ...

have digitised many of thDesign Council's files

relating to the planning of the festival.

Principal events

England

Exhibitions *South Bank, London (4 May – 30 September) *Science, South Kensington (4 May – 30 September) *Architecture, Poplar (3 May – 30 September) *Books, South Kensington (5 May – 30 September) *1851 Centenary Exhibition, South Kensington (1 May – 11 October) *Festival of British Films, London (4 June – 17 June) Festival Pleasure Gardens, Battersea Park, London (3 May – 3 November) London Season of the Arts (3 May – 30 June) Arts Festivals * Stratford-upon-Avon (24 March – 27 October) * Bath (20 May – 2 June) * Bournemouth andWessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

(3 June – 17 June)

*York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

(3 June – 17 June)

*Aldeburgh

Aldeburgh ( ) is a coastal town in the county of Suffolk, England. Located to the north of the River Alde. Its estimated population was 2,276 in 2019. It was home to the composer Benjamin Britten and remains the centre of the international Alde ...

(8 June – 17 June)

*Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

(18 June – 30 June)

* Cheltenham (2 July – 14 July)

*Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

(2 July – 16 July)

* Brighton (16 July – 25 August)

*Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

(18 July – 10 August)

*Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

(22 July – 12 August)

*Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

(30 July – 18 August)

*Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

(2 September – 7 September)

Wales

Pageant of Wales, Sophia Gardens, Cardiff St Fagan's Folk Festival, Cardiff Welsh Hillside Farm Scheme, Dolhendre Arts FestivalsScotland

Exhibitions *Industrial Power, Glasgow *Contemporary Books, Glasgow *"Living Traditions" – Scottish Architecture and Crafts, Edinburgh *18th Century Books, Edinburgh Arts Festivals Gathering of the Clans, Edinburgh Scots Poetry Competition Masque of St. Andrews, St. AndrewsNorthern Ireland

Ulster Farm and Factory, Belfast Arts FestivalTravelling Exhibitions

Festival Ship ''Campania'',: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

*Southampton (4 May – 14 May)

*Dundee (18 May – 26 May)

*Newcastle (30 May – 16 June)

*Hull (20 June – 30 June)

*Plymouth (5 July – 14 July)

*Bristol (18 July – 28 July)

*Cardiff (31 July – 11 August)

*Belfast (15 August – 1 September)

*Birkenhead (5 September – 14 September)

*Glasgow (18 September – 6 October)

Land Travelling Exhibition : England

*Manchester (5 May – 26 May)

*Leeds (23 June – 14 July)

*Birmingham (4 August — 25 August)

*Nottingham (15 September – 6 October)

Festival Ship ''Campania'',: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

*Southampton (4 May – 14 May)

*Dundee (18 May – 26 May)

*Newcastle (30 May – 16 June)

*Hull (20 June – 30 June)

*Plymouth (5 July – 14 July)

*Bristol (18 July – 28 July)

*Cardiff (31 July – 11 August)

*Belfast (15 August – 1 September)

*Birkenhead (5 September – 14 September)

*Glasgow (18 September – 6 October)

Land Travelling Exhibition : England

*Manchester (5 May – 26 May)

*Leeds (23 June – 14 July)

*Birmingham (4 August — 25 August)

*Nottingham (15 September – 6 October)

The South Bank Exhibition

Construction of the South Bank site opened up a new public space, including a riverside walkway, where previously there had been warehouses and working-class housing. The layout of the South Bank site was intended to showcase the principles of

Construction of the South Bank site opened up a new public space, including a riverside walkway, where previously there had been warehouses and working-class housing. The layout of the South Bank site was intended to showcase the principles of urban design

Urban design is an approach to the design of buildings and the spaces between them that focuses on specific design processes and outcomes. In addition to designing and shaping the physical features of towns, cities, and regional spaces, urban d ...

that would feature in the post-war rebuilding of London and the creation of the new towns. These included multiple levels of buildings, elevated walkways and avoidance of a street grid. Most of the South Bank buildings were International Modernist in style, little seen in Britain before the war.

The architecture and display of the South Bank Exhibition were planned by the Festival Office's Exhibition Presentation Panel, whose members were:

*Gerald Barry, ''Director-General, Chairman''

*Cecil Cooke, ''Director, Exhibitions, Deputy Chairman''

*Misha Black

Sir Misha Black (16 October 1910 – 11 October 1977) was a British-Azerbaijani architect and designer. In 1933 he founded with associates in London the organisation that became the Artists' International Association. In 1943, with Milner Gray ...

*G. A. Campbell, ''Director, Finances and Establishments''

*Hugh Casson

Sir Hugh Maxwell Casson (23 May 1910 – 15 August 1999) was a British architect. He was also active as an interior designer, as an artist, and as a writer and broadcaster on twentieth-century design. He was the director of architecture for t ...

, ''Director, Architecture''

*Ian Cox, ''Director, Science and Technology

*A. D. Hippisley Coxe, ''Council of Industrial Design''

* James Gardner

*James Holland

*M. Hartland Thomas, ''Council of Industrial Design''

* Ralph Tubbs

*Peter Kneebone, ''Secretary''

The theme of the Exhibition was devised by Ian Cox.

The Exhibition comprised the Upstream Circuit: "The Land", the Dome of Discovery, the Downstream Circuit: "The People", and other displays.

Upstream Circuit: "The Land"

''Architect'': Misha Black

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display Design'': James Holland

The exhibits comprised:

*The Land of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Design'': V.Rotter.)

*The Natural Scene (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion)

*The Country. (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Conveners'': A. S. Thomas, Peter B. Collins. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion.)

*Minerals of the Island (''Architects'': Architects' Co-operative Partnership. ''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Beverley Pick.)

*Power and Production (''Architects'':

''Architect'': Misha Black

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display Design'': James Holland

The exhibits comprised:

*The Land of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Design'': V.Rotter.)

*The Natural Scene (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion)

*The Country. (''Architect'': Brian O'Rorke. ''Theme Conveners'': A. S. Thomas, Peter B. Collins. ''Display Designer'': F. H. K. Henrion.)

*Minerals of the Island (''Architects'': Architects' Co-operative Partnership. ''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Beverley Pick.)

*Power and Production (''Architects'': George Grenfell Baines

Sir George Grenfell-Baines (born George Baines; 30 April 1908 – 9 May 2003) was an English architect and town planner. Born in Preston, his family's humble circumstances forced him to start work at the age of fourteen. Both George and ...

and H. J. Reifenberg. ''Theme Convener'': C. J. Whitcombe. ''Display Design'': Warnett Kennedy and Associates)

*Sea and Ships. (''Architects'': Basil Spence

Sir Basil Urwin Spence, (13 August 1907 – 19 November 1976) was a Scottish architect, most notably associated with Coventry Cathedral in England and the Beehive in New Zealand, but also responsible for numerous other buildings in the Moderni ...

and Partners. ''Theme Conveners'': C. Hamilton Ellis and Nigel Clayton. ''Display Designers: James Holland and Basil Spence.)

*Transport. (''Architects and Designers'': Arcon. ''Theme Direction'': George Williams.)

The Dome of Discovery

''Architect'': Ralph Tubbs

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display'': Design Research Unit

The exhibits focused on scientific discovery. They included:

*The Land. (''Theme Convener''. Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Stefan Buzas and Ronald Sandiford.)

*The Earth. (''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Robert Gutman.)

*Polar. (''Theme Convener'': Quinitin Riley and L. P. Macnair. ''Display Designer'': Jock Kinneir.)

*Sea. (''Theme Conveners'': C. Hamilton Ellis and Nigel Clayton. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Ellis Miles.)

*Sky. (''Theme Convener'': Arthur Garratt. ''Display Designer'': Ronald Sandiford.)

*Outer Space. (''Theme Convener'': Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Eric Towell.)

*The Living World. (''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Stirling Craig.)

*The Physical World. (''Theme Conveners'': Arthur Garratt and Jan Read. ''Display Designers'': Ronald Ingles and Clifford Hatts.)

''Architect'': Ralph Tubbs

''Theme'': Ian Cox

''Display'': Design Research Unit

The exhibits focused on scientific discovery. They included:

*The Land. (''Theme Convener''. Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Stefan Buzas and Ronald Sandiford.)

*The Earth. (''Theme Convener'': Sonia Withers. ''Display Designer'': Robert Gutman.)

*Polar. (''Theme Convener'': Quinitin Riley and L. P. Macnair. ''Display Designer'': Jock Kinneir.)

*Sea. (''Theme Conveners'': C. Hamilton Ellis and Nigel Clayton. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Ellis Miles.)

*Sky. (''Theme Convener'': Arthur Garratt. ''Display Designer'': Ronald Sandiford.)

*Outer Space. (''Theme Convener'': Penrose Angwin. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Eric Towell.)

*The Living World. (''Theme Convener'': Kenneth Chapman. ''Display Designers'': Austin Frazer and Stirling Craig.)

*The Physical World. (''Theme Conveners'': Arthur Garratt and Jan Read. ''Display Designers'': Ronald Ingles and Clifford Hatts.)

Downstream Circuit: "The People"

''Architect'': Hugh Casson

''Theme'': M.Hartland Thomas

''Display Design'': James Gardner

The exhibits comprised:

*The People of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Jacquetta Hawkes. ''Display Design'': James Gardner.)

*The Lion and the Unicorn (''Architects'': R. D. Russell, Robert Goodden. ''Theme Conveners'': Hubert Phillips and Peter Stucley. ''Display Designers'': Robert Goodden, R. D. Russell and Richard Guyatt. ''Commentary'': Laurie Lee.)

*Homes and Gardens. (''Architects'': Bronek Katz and Reginald Vaughan. ''Theme Conveners'': A.Hippisley Coxe and S. D. Cooke.)

*The New Schools. (''Architects'': Maxwell Fry and

''Architect'': Hugh Casson

''Theme'': M.Hartland Thomas

''Display Design'': James Gardner

The exhibits comprised:

*The People of Britain. (''Architect'': H. T. Cadbury-Brown. ''Theme Convener'': Jacquetta Hawkes. ''Display Design'': James Gardner.)

*The Lion and the Unicorn (''Architects'': R. D. Russell, Robert Goodden. ''Theme Conveners'': Hubert Phillips and Peter Stucley. ''Display Designers'': Robert Goodden, R. D. Russell and Richard Guyatt. ''Commentary'': Laurie Lee.)

*Homes and Gardens. (''Architects'': Bronek Katz and Reginald Vaughan. ''Theme Conveners'': A.Hippisley Coxe and S. D. Cooke.)

*The New Schools. (''Architects'': Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew

Dame Jane Drew , (24 March 1911 – 27 July 1996) was an English modernist architect and town planner. She qualified at the Architectural Association School in London, and prior to World War II became one of the leading exponents of the Modern ...

. ''Theme Convener'': B. W. Rowe. ''Display Designers'': Nevile Conder and Patience Clifford.)

*Health. (Theme Conveners: Sheldon Dudley and Nigel Clayton. Display Designer: Peter Ray.)

*Sport. (''Architects and Designers'': Gordon Bowyer and Ursula Bowyer. ''Theme Convener'': B. W. Rowe.)

*Seaside. (''Architects and Designers'': Eric Brown and Peter Chamberlain. ''Theme Convener''. A. Hippisley Coxe.)

Other Downstream Displays

*Television. (''Architect and Designer'': Wells Coates. ''Theme'': Malcolm Baker Smith.) * Telecinema. (''Architect'': Wells Coates. ''Programme and Presentation'': J. D. Ralph and R. J. Spottiswoode.) *The 1851 Centenary Pavilion. (''Architect'': Hugh Casson. ''Display Designer'': James Gardner.) *Shot Tower

A shot tower is a tower designed for the production of small-diameter shot balls by free fall of molten lead, which is then caught in a water basin. The shot is primarily used for projectiles in shotguns, and for ballast, radiation shielding, ...

. (''Architecture and Design Treatment'': Hugh Casson and James Gardner.)

*Design Review. (''Display Designers'': Nevile Conder and Patience Clifford.)

Other features of the South Bank Exhibition

The Skylon

An unusual cigar-shaped aluminium-clad steel tower supported by cables, the Skylon was the "Vertical Feature" that was an abiding symbol of the Festival of Britain. The base was nearly 15 metres (50 feet) from the ground, with the top nearly 90 metres (300 feet) high. The frame was clad in aluminium louvres lit from within at night. It was designed by

An unusual cigar-shaped aluminium-clad steel tower supported by cables, the Skylon was the "Vertical Feature" that was an abiding symbol of the Festival of Britain. The base was nearly 15 metres (50 feet) from the ground, with the top nearly 90 metres (300 feet) high. The frame was clad in aluminium louvres lit from within at night. It was designed by Hidalgo Moya

John Hidalgo Moya (5 May 1920 – 3 August 1994), sometimes known as Jacko Moya, was an American-born architect who lived and worked largely in England.

Biography

Born 5 May 1920 in Los Gatos, California, US, to an English mother and Mexican f ...

, Philip Powell and Felix Samuely

Felix James Samuely (3 February 1902 – 22 January 1959) was a Structural engineer.

Born in Vienna, he immigrated to Britain in 1933. Worked with Erich Mendelsohn on the De la Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea (1936), the British Pavilion for the B ...

, and fabricated by Painter Brothers of Hereford, England, between Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge is a road-and-foot-traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, linking Westminster on the west side and Lambeth on the east side.

The bridge is painted predominantly green, the same colour as the leather seats in the ...

and Hungerford Bridge

The Hungerford Bridge crosses the River Thames in London, and lies between Waterloo Bridge and Westminster Bridge. Owned by Network Rail Infrastructure Ltd (who use its official name of Charing Cross Bridge) it is a steel truss railway bridge ...

. It had a steel latticework frame, pointed at both ends and supported on cables slung between three steel beams. The partially constructed Skylon was rigged vertically, then grew taller ''in situ''. The architects' design was made possible by the engineer Felix Samuely who, at the time, was a lecturer at the Architectural Association

The Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, commonly referred to as the AA, is the oldest independent school of architecture in the UK and one of the most prestigious and competitive in the world. Its wide-ranging programme ...

School of Architecture in Bedford Square, Bloomsbury. The Skylon was scrapped in 1952 on the orders of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, who saw it as a symbol of the preceding Labour government. It was demolished and sold for scrap after being toppled into the Thames.

Royal Festival Hall

Designed byLeslie Martin

Sir John Leslie Martin (17 August 1908, in Manchester – 28 July 2000) was an English architect, and a leading advocate of the International Style. Martin's most famous building is the Royal Festival Hall. His work was especially influence ...

, Peter Moro

Peter Meinhard Moro (27 May 1911 – 10 October 1998) was a London-based architect whose practice developed many notable public buildings. He was the son of Austrian physician and paediatrician Ernst Moro.

Life and works

Moro was born in Heide ...

and Robert Matthew

Sir Robert Hogg Matthew, OBE FRIBA FRSE (12 December 1906 – 2 June 1975) was a Scottish architect and a leading proponent of modernism.

Early life & studies

Robert Matthew was the son of John Fraser Matthew (1875–1955) (also an archite ...

from the LCC's Architects' Department and built by Holland, Hannen & Cubitts for London County Council

London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today kno ...

. The foundation stone was laid by Prime Minister Clement Attlee in 1949, on the site of the former Lion Brewery, built in 1837. Martin was 39 when he was appointed to lead the design team in late 1948. He designed the structure as an 'egg in a box', a term he used to describe the separation of the curved auditorium space from the surrounding building and the noise and vibration of the adjacent railway viaduct. Sir Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, CH (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with th ...

used similar imagery, calling the building a "giant chicken coop". The building was officially opened on 3 May 1951. The inaugural concerts were conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent and Sir Adrian Boult. In April 1988 it was designated a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

, the first post-war building to become thus protected.

Minor features

* The Festival Administration Building, by Maxwell Fry,Jane Drew

Dame Jane Drew , (24 March 1911 – 27 July 1996) was an English modernist architect and town planner. She qualified at the Architectural Association School in London, and prior to World War II became one of the leading exponents of the Modern ...

and Edward Mills.

Festival Pleasure Gardens

The Festival Pleasure Gardens were created to present a lighter side of the Festival of Britain. They were erected in

The Festival Pleasure Gardens were created to present a lighter side of the Festival of Britain. They were erected in Battersea Park

Battersea Park is a 200-acre (83-hectare) green space at Battersea in the London Borough of Wandsworth in London. It is situated on the south bank of the River Thames opposite Chelsea and was opened in 1858.

The park occupies marshland recla ...

, a few miles from the South Bank Exhibition. Attractions included:

*An amusement park which would outlast the other entertainments. It included the Big Dipper

The Big Dipper ( US, Canada) or the Plough ( UK, Ireland) is a large asterism consisting of seven bright stars of the constellation Ursa Major; six of them are of second magnitude and one, Megrez (δ), of third magnitude. Four define a "bowl" ...

and became the Battersea Fun Fair, staying open until the mid-1970s.

*A miniature railway

A ridable miniature railway (US: riding railroad or grand scale railroad) is a large scale, usually ground-level railway that hauls passengers using locomotives that are often models of full-sized railway locomotives (powered by diesel or petro ...

designed by Rowland Emett

Frederick Rowland Emett OBE (22 October 190613 November 1990), known as Rowland Emett (with the forename sometimes spelled "Roland" s his middle name appears on his birth certificateand the surname frequently misspelled "Emmett"), was an Engl ...

. It ran for 500 yards along the south of the gardens with a station near the south east entrance and another (with snack bar) at the western end of the line;

*A "West End" Restaurant with a terrace overlooking the river and facing Cheyne Walk.

*Foaming Fountains, later restored.

*A wine garden surrounded by miniature pavilions.

*A wet weather pavilion with a stage facing two ways so that performances could take place in the open air. It had murals designed by the film set designer Ferdinand Bellan.

*An amphitheatre seating 1,250 people. The opening show featured the music hall star Lupino Lane

Henry William George Lupino (16 June 1892 – 10 November 1959) professionally Lupino Lane, was an English actor and theatre manager, and a member of the famous Lupino family, which eventually included his cousin, the screenwriter/director/actr ...

and his company. It was later turned into a circus.

The majority of the buildings and pavilions on the site were designed by John Piper. There was also a whimsical Guinness Festival Clock resembling a three dimensional version of a cartoon drawing. The Pleasure Gardens received as many visitors as the South Bank Festival. They were managed by a specially-formed private company financed by loans from the Festival Office and the London County Council. As the attractions failed to cover their costs, it was decided to keep them open after the rest of the Festival had closed.

Aspects of the Festival

Architecture

The Festival architects tried to show by the design and layout of the South Bank Festival what could be achieved by applying moderntown planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

ideas. The Festival Style, (also called "Contemporary") combining modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

with whimsy and Englishness, influenced architecture, interior design, product design and typography in the 1950s. William Feaver

William Feaver (born 1 December 1942) is a British art critic, curator, artist and lecturer. From 1975–1998 he was the chief art critic of the Observer, and from 1994 a visiting professor at Nottingham Trent University. His book ''The Pitmen P ...

describes the Festival Style as "Braced legs, indoor plants, lily-of-the valley sprays of lightbulbs, aluminium lattices, Cotswold-type walling with picture windows, flying staircases, blond wood, the thorn, the spike, the molecule."William Feaver, "Festival Star", in Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier, ''A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain 1951'', London, Thames and Hudson, 1976 , p. 54 The influence of the Festival Style was felt in the new towns

A planned community, planned city, planned town, or planned settlement is any community that was carefully planned from its inception and is typically constructed on previously undeveloped land. This contrasts with settlements that evolve ...

coffee bars

and office blocks of the fifties. Harlow new town and the rebuilding of

Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

city centre are said to show the influence of the Festival Style "in their light structures, picturesque layout and incorporation of works of art", and Coventry Cathedral (1962), designed by Basil Spence, one of the Festival architects, was dubbed "The Festival of Britain at Prayer".

There was an exhibition about building research, town planning and architecture, the "Live architecture" exhibit of buildings, open spaces and streets in the

There was an exhibition about building research, town planning and architecture, the "Live architecture" exhibit of buildings, open spaces and streets in the Lansbury Estate

The Lansbury Estate is a large, historic council housing estate in Poplar and Bromley-by-Bow in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is named after George Lansbury, a Poplar councillor and Labour Party MP.

History

Lansbury Estate is one ...

, Poplar (named after the former Labour Party leader George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31, he spe ...

. Plans for social housing in the area had commenced in 1943. By the end of the war nearly a quarter of the buildings in the area had been destroyed or badly damaged. In 1948, the Architecture Council decided that the Poplar site would make a good exhibition partly because it was near to the other Festival exhibitions. Despite funding problems, work began in December 1949 and by May 1950 was well advanced. The wet winter of 1950–51 delayed work, but the first houses were completed and occupied by February 1951. The exhibition opened on 3 May 1951 along with the other Festival exhibitions. Visitors first went to the Building Research Pavilion, which displayed housing problems and their solutions, then to the Town Planning Pavilion, a large, red-and-white striped tent. The Town Planning Pavilion demonstrated the principles of town planning and the urgent need for new towns, including a mock up of an imaginary town called "Avoncaster". Visitors then saw the buildings of the Lansbury Estate. Attendance was disappointing, only 86,426 people visiting, compared to 8 million who visited the South Bank exhibition. Reaction to the development by industry professionals was lukewarm, some criticising its small scale. Subsequent local authorities concentrated on high-rise, high-density social housing rather than the Lansbury Estate model. The estate remains popular with residents. Among the remaining 1951 buildings are Trinity Independent Chapel, and The Festival Inn and Festive Briton (now Callaghans) pubs.

Misha Black, one of the Festival architects, said that the Festival created a wide audience for architectural modernism but that it was common currency among professional architects that the design of the Festival was not innovative. The design writer Reyner Banham has questioned the originality and the Englishness of the Festival Style and indeed the extent of its influence.Reyner Banham, "The Style: 'Flimsy ... Effeminate'?" in Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier, ''A Tonic to the Nation: The Festival of Britain 1951'', London, Thames and Hudson, 1976 Young architects in 1951 are said to have despised the Festival of Britain for its architecture. "It was equated with the 'Contemporary Style', and an editorial on New Brutalism in ''Architectural Design'' in 1955 carried the epigraph, 'When I hear the word "Contemporary" I reach for my revolver.'"

Design

The South Bank Exhibition included a Design Review that presented "an illustrated record of contemporary achievement in British industry", showing "the high standard of design and craftsmanship that has been reached in a wide range of British products." The exhibits were based on the stock list of the Council of Industrial Design (CoID) and were chosen for appearance, finish, workmanship, technical efficiency, fitness for purpose and economy of production. In selecting and promoting designs in this way, the Festival was an influential advocate of the concept of "Good Design", a rational approach to product design in accordance with the principles of the Modern Movement. Its advocacy of Good Design had grown partly out of the standards of utility furniture created during the war ( Gordon Russell, the Director of the CoID, had been Chairman of the Utility Furniture Design Panel) and partly out of the CoID's Britain Can Make It exhibition of 1946. The CoiD's stock list was retained and inherited by its successor, theDesign Council

The Design Council, formerly the Council of Industrial Design, is a United Kingdom charity incorporated by Royal Charter. Its stated mission is "to champion great design that improves lives and makes things better".

It was instrumental in the prom ...

.

Design, science and industry came together in the Festival Pattern Group, which commissioned textiles, wallpaper, domestic objects and Festival exhibits based on x-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

. The idea of using the molecular patterns revealed in x-ray crystallography in surface patterns was first suggested by Dr Helen Megaw, a leading Cambridge University crystallographer. After hearing a presentation by Dorothy Hodgkin to the Society of Industrial Artists, Mark Hartland Thomas, chief industrial officer of the CoID, took up the idea and formed the Festival Pattern Group. Hartland Thomas was a member of the Festival of Britain Presentation Panel and was co-ordinating the CoID's stock list. He secured the Regatta Restaurant, one of the temporary restaurants on the South Bank, for an experiment in pattern design based on the crystal structure of haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

, insulin, wareite, china clay

Kaolinite ( ) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4. It is an important industrial mineral. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica () linked through oxygen atoms to one octahedra ...

, mica and other molecules, which were used for the surface patterns of the restaurant furnishings. The designs that were sponsored by the Festival Pattern Group chimed in with displays in the Dome of Discovery about the structure of matter and the Festival's emphasis on progress, science and technology. The Science Museum in London holds a collection of the Festival's fabrics donated by Dr Megaw; it also includes the official souvenir book by Mark Hartland Thomas.

Lettering and type design featured prominently in the graphic style of the Festival and was overseen by a typography panel including the lettering historian Nicolete Gray. A typeface for the Festival, Festival Titling, was specially commissioned and designed by Philip Boydell. It was based on condensed sans-serif capitals and had a three-dimensional form making it suitable for use in exhibition display typography

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language legible, readable and appealing when displayed. The arrangement of type involves selecting typefaces, point sizes, line lengths, line-spacing ( leading), ...

. It has been said to bear "a vague resemblance to bunting". The lettering on the Royal Festival Hall and the temporary Festival building on the South Bank was a bold, sloping slab serif

In typography, a slab serif (also called ''mechanistic'', ''square serif'', ''antique'' or ''Egyptian'') typeface is a type of serif typeface characterized by thick, block-like serifs. Serif terminals may be either blunt and angular ( Rockwell), ...

letter form, determined by Gray and her colleagues, including Charles Hasler and Gordon Cullen

Thomas Gordon Cullen (9 August 1914 – 11 August 1994) was an influential British architect and urban designer who was a key motivator in the Townscape movement. Cullen presented a new theory and methodology for urban visual analysis and design b ...

, illustrated in Gray's ''Lettering on Buildings'' (1960) and derived in part from typefaces used in the early 19th century. It has been described as a "turn to a jauntier and more decorative visual language" that was "part of a wider move towards the appreciation of vernacular arts and the peculiarities of English culture". The lettering in the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion was designed by John Brinkley.

The graphic designer for the Festival was Abram Games

Abram Games (29 July 191427 August 1996) was a British graphic designer. The style of his work – refined but vigorous compared to the work of contemporaries – has earned him a place in the pantheon of the best of 20th-century graphic desi ...

, who created its emblem, the Festival Star.

The arts

The South Bank Exhibition showed the work of contemporary artists such as William Scott, includingmural

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' is a Spani ...

s by Victor Pasmore

Edwin John Victor Pasmore, CH, CBE (3 December 190823 January 1998) was a British artist. He pioneered the development of abstract art in Britain in the 1940s and 1950s.

Early life

Pasmore was born in Chelsham, Surrey, on 3 December 1908. He ...

, John Tunnard, Feliks Topolski

Feliks Topolski RA (14 August 1907 – 24 August 1989) was a Polish expressionist painter and draughtsman working primarily in the United Kingdom.

Biography

Feliks Topolski was born on 14 August 1907 in Warsaw, Poland. He studied in the Acade ...

, Barbara Jones, and John Piper and sculptures by Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Lynn Chadwick

Lynn Russell Chadwick, (24 November 1914 – 25 April 2003) was an English sculptor and artist. Much of his work is semi-abstract sculpture in bronze or steel. His work is in the collections of MoMA in New York, the Tate in London and the ...

, Jacob Epstein

Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 21 August 1959) was an American-British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a British subject in 1911.

He often produce ...

and Reg Butler

Reginald Cotterell Butler (28 April 1913 – 23 October 1981) was an English sculptor. He was born at Bridgefoot House, Buntingford, Hertfordshire to Frederick William Butler (1880–1937) and Edith (1880–1969), daughter of blacksm ...

.

Arts festivals were held throughout the summer as part of the Festival of Britain:

*Aberdeen Festival ''30 July – 13 August''

*Aldeburgh Festival

The Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts is an English arts festival devoted mainly to classical music. It takes place each June in the Aldeburgh area of Suffolk, centred on Snape Maltings Concert Hall.

History of the Aldeburgh Festival

Th ...

of Music and the Arts ''8–17 June''

*Bath Assembly ''20 May – 2 June''

*Belfast Festival of the Arts ''7 May – 30 June''

*Bournemouth and Wessex Festival ''13–17 June''

*Brighton Regency Festival ''16 July – 25 August''

*Cambridge Festival ''30 July – 18 August''

*Canterbury Festival ''18 July – 10 August''

*Cheltenham Festival

The Cheltenham Festival is a horse racing-based meeting in the National Hunt racing calendar in the United Kingdom, with race prize money second only to the Grand National. The four-day festival takes place annually in March at Cheltenham Ra ...

of British Contemporary Music ''18 July – 10 August''

*Dumfries Festival of the Arts ''24–30 June''

*Inverness 1951 Highland Festival ''17–30 June''

*Liverpool Festival ''22 July – 12 August''

*Llangollen International Eisteddfod

The Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod is a music festival which takes place every year during the second week of July in Llangollen, North Wales. It is one of several large annual Eisteddfodau in Wales. Singers and dancers from arou ...

''3–8 July''

*Llanrwst (Royal National Eisteddfod of Wales) ''6–11 August''

*Norwich Festival ''18–30 June''

*Oxford Festival ''2–16 July''

*Perth Arts Festival ''27 May – 16 June''

*Stratford-upon-Avon (Shakespeare Festival) ''April – October''

*St David's Festival (Music and Worship) ''10–13 July''

*Swansea Festival of Music ''16–29 September''

*Worcester ( Three Choirs Festival) ''2–7 September''

*York Festival (including a revival of the York Mystery Plays

The York Mystery Plays, more properly the York Corpus Christi Plays, are a Middle English cycle of 48 mystery plays or pageants covering sacred history from the creation to the Last Judgment. They were traditionally presented on the feast day ...

)

The London Season of the Arts comprised exhibitions specially arranged for the Festival of Britain. They included:

*"An Exhibition of Sixty Large Paintings commissioned for the Festival of Britain" ("60 Paintings for '51"), Suffolk Galleries, organised by the Arts Council, prize awarded to William Gear

William Gear RA RBSA (2 August 1915 – 27 February 1997) was a Scottish painter, most notable for his abstract compositions.

Early life

Gear was born in Methil in south-east Fife, Scotland, the son of Janet (1886-1955) and Porteous Gear ...

;

*Exhibitions of the works of Hogarth and Henry Moore, Tate Gallery;

*Open-air International Exhibition of Sculpture, Battersea Park;

*"Modern British Painting", New Burlington Gallery;

*"An Exhibition of Exhibitions", Royal Society of the Arts.

*Two exhibitions at the Whitechapel Art Gallery

The Whitechapel Gallery is a public art gallery in Whitechapel on the north side of Whitechapel High Street, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The original building, designed by Charles Harrison Townsend, opened in 1901 as one of the ...

: "Black Eyes and Lemonade" and "East End 1851".

Barbara Jones and Tom Ingram organised "Black Eyes and Lemonade", an exhibition of British popular and traditional art, in association with the Society for Education in Art and the Arts Council. In the same year she surveyed the popular arts in her influential book, ''The Unsophisticated Arts'', which included taxidermy, fairgrounds, canal boats, seaside, riverside, tattooing, the decoration of food, waxworks, toys, rustic work, shops, festivals and funerals. She said of the popular arts," some of it is made for themselves by people without professional training in the arts or in the appreciation of them, and some of it has been made for those people by professionals who work to their taste."

The Festival was the occasion of the first performance of steelpan

The steelpan (also known as a pan, steel drum, and sometimes, collectively with other musicians, as a steelband or steel orchestra) is a musical instrument originating in Trinidad and Tobago. Steelpan musicians are called pannists.

Descriptio ...

music in Britain by the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra.

Film

TheBritish Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery (United Kingdom), National Lot ...

was asked by Herbert Morrison in 1948 to consider the contribution that film could make to the Festival. It set up a panel including Michael Balcon

Sir Michael Elias Balcon (19 May 1896 – 17 October 1977) was an English film producer known for his leadership of Ealing Studios in West London from 1938 to 1955. Under his direction, the studio became one of the most important British fil ...

, Antony Asquith, John Grierson, Harry Watt and Arthur Elston, which became a committee of sponsorship and distribution. Over a dozen sponsored documentary films were made for the Festival, including

*"Air Parade", sponsored by the Shell Film Unit

*"Family Portrait", made by Humphrey Jennings

*"David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

", a short film based on the life of David Rees Griffiths (and in which he appeared), made by Wide Pictures and the Welsh Committee

*"Water of Time", made by International Realist films and sponsored by the Port of London Authority

*"Forward a Century", sponsored by the Petroleum Films Bureau.

Several feature films were planned, but only one was completed in time, namely '' The Magic Box'', a biopic concerning pioneer William Friese-Greene

William Friese-Greene (born William Edward Green, 7 September 1855 – 5 May 1921) was a prolific English inventor and professional photographer. He was known as a pioneer in the field of motion pictures, having devised a series of cameras in 1 ...

, made by Festival Film Productions.

There was a purpose-built film theatre on the South Bank, the Telecinema (sometimes called the "Telekinema"), designed by Wells Coates, which showed documentary and experimental film exploiting stereophony and stereoscopy and the new invention of television. It was one of the most popular attractions of the Festival, with 458,693 visitors. When the Festival ended, the Telecinema was handed over to the BFI for use as a members-only repertory cinema club, re-opening in 1952 as the National Film Theatre

BFI Southbank (from 1951 to 2007, known as the National Film Theatre) is the leading repertory cinema in the UK, specialising in seasons of classic, independent and non-English language films. It is operated by the British Film Institute.

His ...

.

Film was integral to the South Bank Exhibition, used to explain manufacturing, science and technology. The Dome of Discovery, the Exhibition of Science in South Kensington and the travelling Festival Exhibition made extensive use of educational and explanatory film.

Film festivals, including those at Edinburgh Film Festival, Bath and Glasgow participated in the Festival of Britain, and local authorities put on film festivals, helped by a BFI pamphlet, ''How to put on a Film Show''.

Commercial cinema chains and independent cinemas also joined in, the Gaumont and Odeon chains programming seasons of British films. "And finally, if the Festival visitor had not tired of the medium, they could purchase colour 16mm film of Britain’s historic buildings and pageantry and filmstrips of the Festival of Britain and London as souvenirs."

One of the British Broadcasting Corporation #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

's contributions to the Festival was a television musical entitled '' The Golden Year'', broadcast on 23 June and 2 July.

Science

A new wing was built for theScience Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, industry and industrial machinery, etc. Modern trends in ...

to hold th''Exhibition of Science''

The first part of the exhibition showed the physical and chemical nature of matter and the behaviour of elements and molecules. The second part, "The Structure of Living Things", dealt with plants and animals. The third part, "Stop Press", showed some of the latest topics of research in science and their emergence from the ideas illustrated in the earlier sections of the exhibition. They included "the penetrating rays which reach us from outer space, what goes on in space and in the stars, and a range of subjects from the electronic brain to the processes and structures on which life is based." It has been claimed that "the Festival of Britain created a confusion at the heart of subsequent discussions amongst administrators and educationalists concerning the place science should have in British life and thought as a whole (particularly education), and its role in Britain’s post-war greatness."

Other Festival events

There were hundreds of events associated with the Festival, some of which were:

*The selection of

There were hundreds of events associated with the Festival, some of which were:

*The selection of Trowell

Trowell is a village and civil parish in Nottinghamshire, England. It lies a few miles west of Nottingham, in the borough of Broxtowe on the border with Derbyshire. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 2,568, falling to 2,378 at ...

, a Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The trad ...

village in the middle of England, as the Festival Village.

*The re-design of Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

by George Grey Wornum

George Grey Wornum (17 April 1888 – 11 June 1957) was a British architect.

Grey Wornum was born in London and educated at Bradfield College and the Slade School of Art. He studied architecture under the guidance of his uncle, Ralph Selden Wornum ...

in preparation for the Festival of Britain year.

*Commemorative postage stamps and many souvenirs, official and unofficial.

*A commemorative crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

coin (presented with a certificate in either a red or green presentation box), The crown coin featured on its reverse the St. George and the Dragon design by Benedetto Pistrucci, best known for its place on British Sovereign coins. The certificate states "The first English Silver Crown piece was minted in 1551. Four hundred years later, on the occasion of the Festival of Britain, the Royal Mint has issued a Crown piece, bearing on its edge the Latin inscription MDCCCLI CIVIUM INDUSTRIA FLORET CIVITAS MCMLI-1951 ''By the industry of its people the State flourishes'' 1951". A non-circulating cupronickel coin, about 2 million were minted, most in "prooflike" condition. It remains very inexpensive.

* The restoration of Moot Hall, Elstow by Bedfordshire County Council. The hall was opened to the public as a museum of 17th century life and the local-born author John Bunyan. The council also erected signs in several of its villages, each bearing the village name and the festival and council CC logos.

*The first performance of Robert McLellan's play ''Mary Stewart'' at the Glasgow Citizens Theatre

The Citizens Theatre, in what was the Royal Princess's Theatre, is the creation of James Bridie and is based in Glasgow, Scotland as a principal producing theatre. The theatre includes a 500-seat Main Auditorium, and has also included various ...

.

*The first performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams's opera ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christianity, Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a prog ...

'' on 26 April 1951, at the Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Ope ...

*An exhibition about Sherlock Holmes (part of which is now owned by Westminster Libraries and part by the Sherlock Holmes pub).

* '' The William Shakespeare'' and '' The Merchant Venturer'', two daily excursion trains run by the Western Region of British Railways

The Western Region was a region of British Railways from 1948. The region ceased to be an operating unit in its own right on completion of the "Organising for Quality" initiative on 6 April 1992. The Region consisted principally of ex-Great We ...

from London to sites of British history, Stratford upon Avon and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

. ''The William Shakespeare'' proved to be financially unviable and only ran for the summer of the festival, but ''The Merchant Venturer'' remained in service until 1961.

Attendance figures