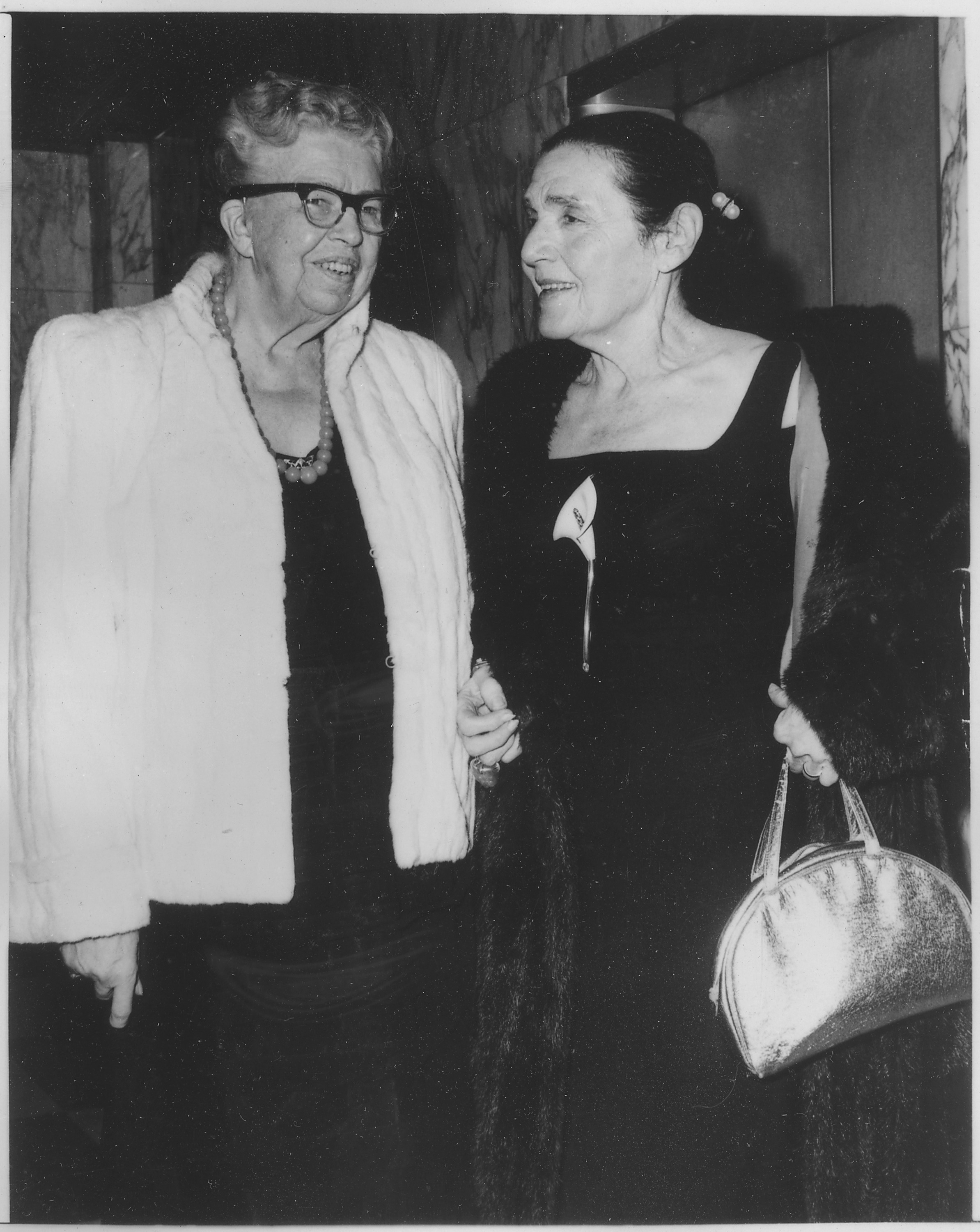

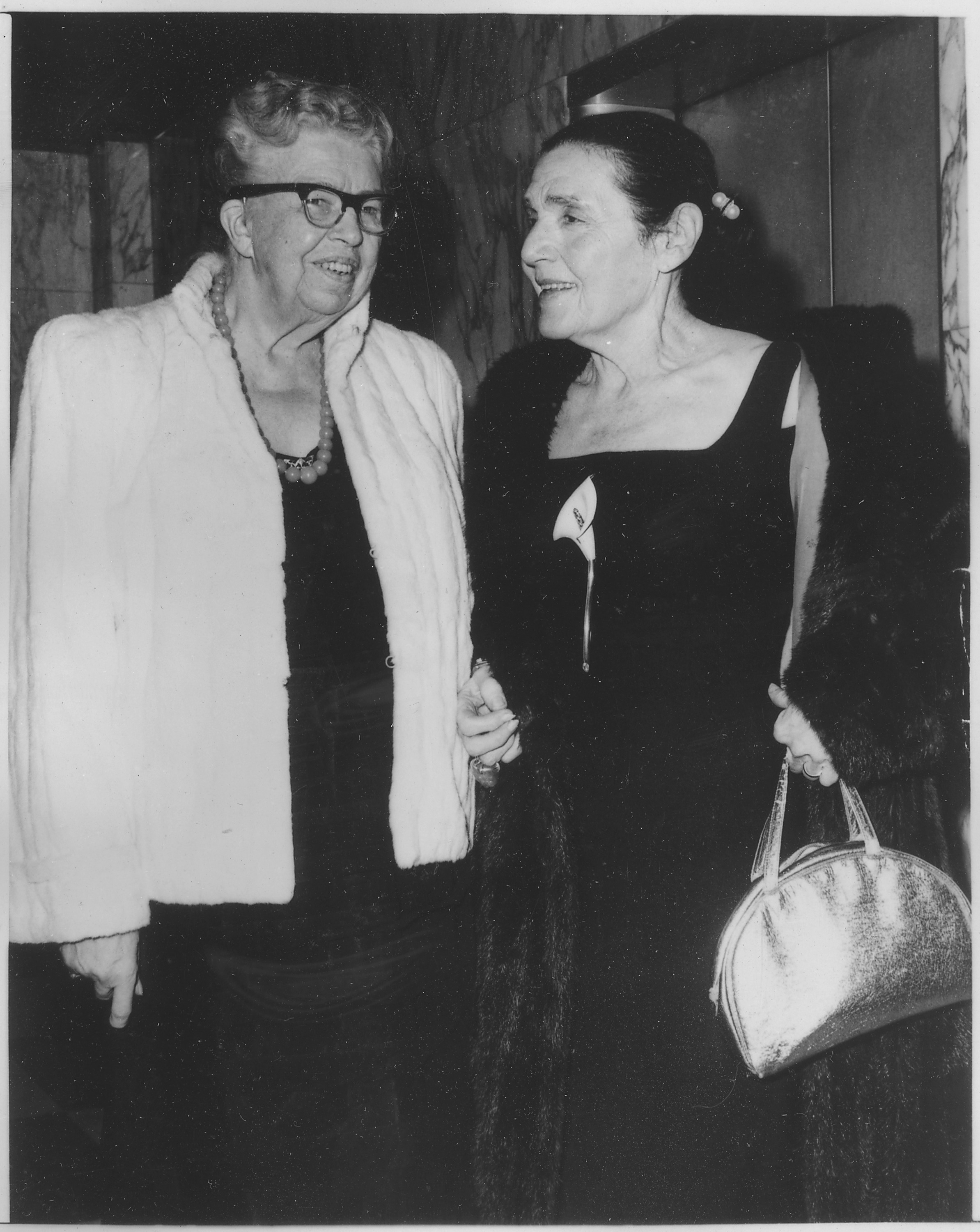

Fannie Hurst on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fannie Hurst (October 18, 1889 – February 23, 1968) was an American

Hurst was born on October 19, 1885, in

Hurst was born on October 19, 1885, in

'',_May_30,_1909,_image_8,_column_5.html" ;"title="St. Louis Post-Dispatch">Untitled, '' St._Louis_Post-Dispatch">Untitled,_''St._Louis_Post-Dispatch

'',_May_30,_1909,_image_8,_column_5/ref>Marguerite_Martyn.html" ;"title="St. Louis Post-Dispatch

'', May 30, 1909, image 8, column 5">St. Louis Post-Dispatch">Untitled, ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch

'', May 30, 1909, image 8, column 5/ref>Marguerite Martyn">Martyn, Marguerite (June 17, 1909)

"Marguerite Martyn Discovers Real College Playwright in Fannie Hurst"

''St. Louis Post-Dispatch''. image 13. After her college graduation, Hurst briefly worked in a shoe factory before moving to New York City in 1911 to pursue a writing career. Despite having already published one story while in college, she received more than 35 rejections before she was able to sell a second story and establish herself as a regularly published author. During her early years in New York she worked as a waitress at Childs and a sales clerk at

Simmons College Library

/ref>

In the years after World War I, Hurst became famous as an author of extremely popular short stories and novels, many of which were made into films. Her popularity continued for several decades, only beginning to decline after

In the years after World War I, Hurst became famous as an author of extremely popular short stories and novels, many of which were made into films. Her popularity continued for several decades, only beginning to decline after

Simmons College Library

/ref> By 1925, she had published five collections of short stories and two novels, and become one of the most highly paid authors in the United States. It was said of Hurst that "no other living American woman has gone so far in fiction in so short a time." Her works were designed to appeal primarily to a female audience, and usually had working-class or middle-class female protagonists concerned with romantic relationships and economic need (see Major themes). Her work was described in 1928 as "overwhelmingly prodigal of both feeling and language ... mix ngnaked, realistic detail with simple unrestrained emotion." Hurst was heavily influenced by the works of The great popularity of Hurst's works gave her major celebrity status. Hurst also took steps to publicize herself for purposes of promoting both her writing and the activist causes she espoused (see

The great popularity of Hurst's works gave her major celebrity status. Hurst also took steps to publicize herself for purposes of promoting both her writing and the activist causes she espoused (see

Throughout her life, Hurst was involved with many social activist groups supporting equal rights for women and African Americans, and occasionally assisting other people in need. In 1921, Hurst was among the first to join the

Throughout her life, Hurst was involved with many social activist groups supporting equal rights for women and African Americans, and occasionally assisting other people in need. In 1921, Hurst was among the first to join the

Fannie Hurst Papers

at the

Fannie Hurst Papers

at Washington University in St. Louis

Fannie Hurst Collection

at

novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire ...

and short-story writer whose works were highly popular during the post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

era. Her work combined sentimental, romantic themes with social issues of the day, such as women's rights and race relations. She was one of the most widely read female authors of the 20th century, and for a time in the 1920s she was one of the highest-paid American writers. Hurst also actively supported a number of social causes, including feminism, African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

equality, and New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

programs.

Although her novels, including ''Lummox'' (1923), '' Back Street'' (1931), and '' Imitation of Life'' (1933), lost popularity over time and were mostly out-of-print as of the 2000s, they were bestsellers when first published and were translated into many languages. She also published over 300 short stories during her lifetime. Hurst is known for the film adaptation

A film adaptation is the transfer of a work or story, in whole or in part, to a feature film. Although often considered a type of derivative work, film adaptation has been conceptualized recently by academic scholars such as Robert Stam as a dia ...

s of her works, including '' Imitation of Life'' (1934), '' Four Daughters'' (1938), '' Imitation of Life'' (1959), '' Humoresque'' (1946), and '' Young at Heart'' (1954).

Early life

Hurst was born on October 19, 1885, in

Hurst was born on October 19, 1885, in Hamilton, Ohio

Hamilton is a city in and the county seat of Butler County, Ohio, United States. Located north of Cincinnati, Hamilton is the second largest city in the Greater Cincinnati area and the 10th largest city in Ohio. The population was 63,399 at ...

, to shoe-factory owner Samuel Hurst and his wife Rose (née Koppel), who were assimilated Jewish

Jewish assimilation ( he, התבוללות, ''hitbolelut'') refers either to the gradual cultural assimilation and social integration of Jews in their surrounding culture or to an ideological program in the age of emancipation promoting confor ...

emigrants from Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

. A younger sister died of diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

at age three, leaving Hurst as her parents' only surviving child. She grew up at 5641 Cates Avenue in St. Louis, Missouri and was a student at Central High School.

She attended Washington University

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU or WUSTL) is a private research university with its main campus in St. Louis County, and Clayton, Missouri. Founded in 1853, the university is named after George Washington. Washington University is r ...

and graduated in 1909 at age 24. In her autobiography, she portrayed her family as comfortably middle-class, except for a two-year stint in a boarding house necessitated by a sudden financial downturn, which sparked her initial interest in the plight of the poor. However, this has been challenged by later researchers, including her biographer Brooke Kroeger and literary historian Susan Koppelman. According to Koppelman, while Fannie Hurst was growing up, her father changed businesses four times, never achieved much financial success, and failed in business at least once, and the Hurst family lived at 11 different boarding houses before Fannie turned 16. Kroeger wrote that while Samuel and Rose Hurst did eventually move to a house in a fashionable section of St. Louis, this did not occur until Fannie Hurst's third year of college, rather than during her childhood.

In her last term in college, Hurst wrote the book

A book is a medium for recording information in the form of writing or images, typically composed of many pages (made of papyrus, parchment, vellum, or paper) bound together and protected by a cover. The technical term for this physical ...

and lyrics

Lyrics are words that make up a song, usually consisting of verses and choruses. The writer of lyrics is a lyricist. The words to an extended musical composition such as an opera are, however, usually known as a " libretto" and their writer, ...

for a comic opera, ''The Official Chaperon'', which was given on the Washington University campus in June 1909.Untitled,_''St._Louis_Post-Dispatch'',_May_30,_1909,_image_8,_column_5.html" ;"title="St. Louis Post-Dispatch">Untitled, '' St._Louis_Post-Dispatch">Untitled,_''St._Louis_Post-Dispatch

'',_May_30,_1909,_image_8,_column_5/ref>

'', May 30, 1909, image 8, column 5">St. Louis Post-Dispatch">Untitled, ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch

'', May 30, 1909, image 8, column 5/ref>Marguerite Martyn">Martyn, Marguerite (June 17, 1909)

"Marguerite Martyn Discovers Real College Playwright in Fannie Hurst"

''St. Louis Post-Dispatch''. image 13. After her college graduation, Hurst briefly worked in a shoe factory before moving to New York City in 1911 to pursue a writing career. Despite having already published one story while in college, she received more than 35 rejections before she was able to sell a second story and establish herself as a regularly published author. During her early years in New York she worked as a waitress at Childs and a sales clerk at

Macy's

Macy's (originally R. H. Macy & Co.) is an American chain of high-end department stores founded in 1858 by Rowland Hussey Macy. It became a division of the Cincinnati-based Federated Department Stores in 1994, through which it is affiliated wi ...

and acted in bit parts on Broadway. As Hurst worked these jobs, under the name Rose Samuels, she observed her customers as well as employees. She began to take note of important social issues like unequal pay and gender inequality.

In her spare time, Hurst attended night court sessions and visited Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mil ...

and the slums, becoming in her own words "passionately anxious to awake in others a general sensitiveness to small people", and developing an awareness of "causes, including the lost and the threatened".Frederick, A. (1980). "Hurst, Fannie, Oct. 18, 1889-Feb. 23, 1968". In ''Notable American Women: The Modern Period''. Retrieved froSimmons College Library

/ref>

Career

In the years after World War I, Hurst became famous as an author of extremely popular short stories and novels, many of which were made into films. Her popularity continued for several decades, only beginning to decline after

In the years after World War I, Hurst became famous as an author of extremely popular short stories and novels, many of which were made into films. Her popularity continued for several decades, only beginning to decline after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Throughout her life, Hurst also actively worked and spoke on behalf of social justice organizations and causes supporting feminism and African-American civil rights, and occasionally supported other oppressed groups such as Jewish refugees (although she chose not to support some other Jewish causes), homosexuals, and prisoners.

She was also appointed to several committees associated with President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

programs.

Author

In 1912, after numerous rejections, Hurst finally published a story in ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely ...

'', which shortly thereafter requested exclusive release of her future writings. She went on to publish many more stories, mostly in the ''Post'' and in ''Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

'' magazine, eventually earning as much as $5,000 per story. Her first collection of short stories, ''Just Around the Corner'', was published in 1914, and her first novel, ''Star-Dust: The Story of an American Girl'', appeared in 1921.Hurst, Fannie 1885Fl - 1968. (1999). In The Cambridge guide to women's writing in English. Retrieved froSimmons College Library

/ref> By 1925, she had published five collections of short stories and two novels, and become one of the most highly paid authors in the United States. It was said of Hurst that "no other living American woman has gone so far in fiction in so short a time." Her works were designed to appeal primarily to a female audience, and usually had working-class or middle-class female protagonists concerned with romantic relationships and economic need (see Major themes). Her work was described in 1928 as "overwhelmingly prodigal of both feeling and language ... mix ngnaked, realistic detail with simple unrestrained emotion." Hurst was heavily influenced by the works of

Edgar Lee Masters

Edgar Lee Masters (August 23, 1868 – March 5, 1950) was an American attorney, poet, biographer, and dramatist. He is the author of ''Spoon River Anthology'', ''The New Star Chamber and Other Essays'', ''Songs and Satires'', ''The Great V ...

, particularly ''Spoon River Anthology

''Spoon River Anthology'' (1915), by Edgar Lee Masters, is a collection of short free verse poems that collectively narrates the epitaphs of the residents of Spoon River, a fictional small town named after the Spoon River, which ran near Masters' ...

'' (1916), and also read the works of Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

, and Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Wor ...

. Hurst considered herself to be a serious writer, and publicly disparaged the works of other popular authors such as Gene Stratton-Porter and Harold Bell Wright

Harold Bell Wright (May 4, 1872 – May 24, 1944) was a best-selling American writer of fiction, essays, and nonfiction. Although mostly forgotten or ignored after the middle of the 20th century, he had a very successful career; he is said to hav ...

, dismissing Wright as a "sentimental" author whose works people read only for "relaxation". Early in Hurst's career, critics also considered her a serious artist, admiring her sensitive portrayals of immigrant life and urban working girls. Her stories and books regularly made annual "best-of" lists, and she was called a female O. Henry

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862 – June 5, 1910), better known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American writer known primarily for his short stories, though he also wrote poetry and non-fiction. His works include "The Gift of the ...

. Her second novel, ''Lummox'' (1923), about the tribulations of an oppressed domestic servant, was praised for its insights by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, and Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

. However, some reviewers criticized her for "sappy" plots and careless writing, and F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

, in his 1920 novel '' This Side of Paradise'', had a character presciently describe Hurst as one of several authors "not producing among 'em one story or novel that will last 10 years."

Beginning in the late 1930s, critics no longer took her seriously and sometimes expressed frustration about the continued popularity of her work in the face of bad reviews. In the post-World War II era, she was regarded as merely a popular author who wrote for and about the working classes. She became a favorite target of parodists, including Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, H ...

, who parodied her racially themed novel ''Imitation of Life'' as ''Limitations of Life''. Her own editor, Kenneth McCormick, described her as a "fairly corny artist" but a "wonderful storyteller". She was also called the "Queen of the Sob Sisters", " sob sister" being a term used in the early 20th century for female reporters who wrote sentimental human interest stories designed to evoke an emotional response from female readers. Hurst herself recognized that she was "not a darling of the critics" but said, "I have a vast popular audience — it warms me, like a furnace."

The great popularity of Hurst's works gave her major celebrity status. Hurst also took steps to publicize herself for purposes of promoting both her writing and the activist causes she espoused (see

The great popularity of Hurst's works gave her major celebrity status. Hurst also took steps to publicize herself for purposes of promoting both her writing and the activist causes she espoused (see Social activism

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

). In the 1920s, news media widely covered aspects of her personal life such as her unconventional marriage (see Personal life and death) and a diet on which she lost 40 pounds. She was frequently interviewed about her views on subjects relating to love, marriage and family. For decades, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' continued to report regularly on Hurst's doings, including her walks in Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated ...

with her dogs, her travels abroad, her wardrobe, and the interior decoration of her apartment.

''Back Street'' (1931), Hurst's seventh novel, was hailed as her "magnum opus" and has been called her "best loved" work. Its main character, a confident, independent young gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

woman, falls in love with a married Jewish banker and becomes his secret mistress, sacrificing her own life in the process and ultimately meeting a tragic end. Hurst's next novel, ''Imitation of Life'' (1933), was also hugely popular, and is now considered her best known and most famous novel. It told the story of two single mothers, one white and one African American, who become partners in a successful waffle and restaurant business (modeled after Quaker Oats Company

The Quaker Oats Company, known as Quaker, is an American food conglomerate based in Chicago. It has been owned by PepsiCo since 2001.

History Precursor miller companies

In the 1850s, Ferdinand Schumacher and Robert Stuart founded oat mills. Sc ...

's "Aunt Jemima

Pearl Milling Company (formerly known as Aunt Jemima from 1889 to 2021) is an American breakfast brand for Baking mix, pancake mix, syrup, and other breakfast food products. The original version of the pancake mix for the brand was developed i ...

" pancake

A pancake (or hotcake, griddlecake, or flapjack) is a flat cake, often thin and round, prepared from a starch-based batter that may contain eggs, milk and butter and cooked on a hot surface such as a griddle or frying pan, often frying w ...

mix) and have conflicts with their teenage daughters. Hurst's inspiration for the book was her own friendship with African-American author Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (January 7, 1891 – January 28, 1960) was an American author, anthropologist, and filmmaker. She portrayed racial struggles in the early-1900s American South and published research on hoodoo. The most popular of her four n ...

. However, ''Imitation of Life'' and the two films based on it provoked controversy due to the treatment of African-American characters, including a romanticized mammy figure and a "tragic mulatto

The tragic mulatto is a stereotypical fictional character that appeared in American literature during the 19th and 20th centuries, starting in 1837. The "tragic mulatto" is a stereotypical mixed-race person (a "mulatto"), who is assumed to be dep ...

" who rejects her loving mother in order to pass for white.

Approximately 30 films were made from Hurst's fiction. ''Back Street'' was the basis for three films of the same name in 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort to assassinate Emperor Hir ...

, 1941

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January–August – 10,072 men, women and children with mental and physical disabilities are asphyxiated with carbon monoxide in a gas chamber, at Hadamar E ...

and 1961

Events January

* January 3

** United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower announces that the United States has severed diplomatic and consular relations with Cuba (Cuba–United States relations are restored in 2015).

** Aero Flight 311 (K ...

, plus a fourth film written by Frank Capra

Frank Russell Capra (born Francesco Rosario Capra; May 18, 1897 – September 3, 1991) was an Italian-born American film director, producer and writer who became the creative force behind some of the major award-winning films of the 1930s ...

, '' Forbidden'' (1932), which liberally borrowed elements from Hurst's novel without crediting her. ''Imitation of Life'' was twice adapted for film in 1934

Events

January–February

* January 1 – The International Telecommunication Union, a specialist agency of the League of Nations, is established.

* January 15 – The 8.0 Nepal–Bihar earthquake strikes Nepal and Bihar with a maxi ...

and 1959

Events January

* January 1 - Cuba: Fulgencio Batista flees Havana when the forces of Fidel Castro advance.

* January 2 - Lunar probe Luna 1 was the first man-made object to attain escape velocity from Earth. It reached the vicinity of E ...

. Both were respectively inductees for the 2005 and 2015 National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception ...

lists.

It was also adapted by Joselito Rodriguez for the 1949 Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

film '' Angelitos negros'' ("Little Black Angels"), which was remade in 1970 as both a film and a telenovela. Her short story "Humoresque", published in 1919, was made into a 1920 silent film and a 1946 film noir starring Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford (born Lucille Fay LeSueur; March 23, ncertain year from 1904 to 1908was an American actress. She started her career as a dancer in traveling theatrical companies before debuting on Broadway. Crawford was signed to a motion pict ...

. A later story, "Sister Act", published in ''Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

'' in 1937, inspired the musical films '' Four Daughters'' (1938) and the Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the " Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s, 1950s, and ...

vehicle '' Young at Heart'' (1954).

Hurst continued to write and publish until her death in 1968, although the commercial value of her work declined after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

as popular tastes changed. Her total publications over her nearly six-decade career include 19 novels, over 300 short stories (63 of which were gathered in eight short-story collections), four plays produced on Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

, a full-length autobiography and an autobiographical memoir, numerous magazine articles, personal essays, articles (often unsigned) for various organizations to which she belonged, and screenplays (both independently written and collaborations) for several films.

Social activism

Throughout her life, Hurst was involved with many social activist groups supporting equal rights for women and African Americans, and occasionally assisting other people in need. In 1921, Hurst was among the first to join the

Throughout her life, Hurst was involved with many social activist groups supporting equal rights for women and African Americans, and occasionally assisting other people in need. In 1921, Hurst was among the first to join the Lucy Stone League

The Lucy Stone League is a women's rights organization founded in 1921. Its motto is "A wife should no more take her husband's name than he should hers. My name is my identity and must not be lost."“lucystoneleague.org�Archivedfrom the original ...

, an organization that fought for women to preserve their maiden names. She was a member of the feminist intellectual group Heterodoxy

In religion, heterodoxy (from Ancient Greek: , "other, another, different" + , "popular belief") means "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position". Under this definition, heterodoxy is similar to unorthodoxy, w ...

in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, and was active in the Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

. She volunteered as a regular visitor to inmates of a women's prison in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

she raised money to help Jewish refugees fleeing Europe, but in her earlier years was less supportive of other Jewish causes, saying in a 1925 interview that Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

"segregates us, raises barriers or creates race prejudice". Her attitude changed in the 1950s, and in 1963 she received an honorary award from the Zionist women's organization Hadassah.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Hurst was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and a frequent White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

visitor. Hurst was named chair of the National Housing Commission in 1936–1937 and appointed to the National Advisory Committee to the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

in 1940. She was a delegate to the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

in 1952.

In 1958, Hurst briefly hosted a television talk show

A talk show (or chat show in British English) is a television programming or radio programming genre structured around the act of spontaneous conversation.Bernard M. Timberg, Robert J. Erler'' (2010Television Talk: A History of the TV Talk Sh ...

out of New York called ''Showcase''. ''Showcase'' was notable for presenting several of the earliest well-rounded discussions of homosexuality and was one of the few programs on which homosexual men spoke for themselves rather than being debated by a panel of "experts". Hurst was praised by early homophile

Terms used to describe homosexuality have gone through many changes since the emergence of the first terms in the mid-19th century. In English, some terms in widespread use have been sodomite, Achillean, Sapphic, Uranian, homophile, lesbian, ...

group the Mattachine Society

The Mattachine Society (), founded in 1950, was an early national gay rights organization in the United States, perhaps preceded only by Chicago's Society for Human Rights. Communist and labor activist Harry Hay formed the group with a collectio ...

, which invited Hurst to deliver the keynote address at the Society's 1958 convention.

Life and death

In 1915, Hurst secretly married Jacques S. Danielson, a Russian émigré pianist. Hurst kept her maiden name and the couple maintained separate residences and arranged to renew their marriage contract every five years, if they both agreed to do so. The revelation of the marriage in 1920 made national headlines, and ''The New York Times'' criticized the couple in an editorial for occupying two residences during a housing shortage. Hurst responded by saying that a married woman had the right to retain her own name, her own special life, and her personal liberty. Hurst and Danielson had no children, and remained married until Danielson's death in 1952. After his death, Hurst continued to write weekly letters to him for the next 16 years until she died, and regularly wore a calla lily, the first flower he had ever sent her. During the 1920s and 1930s, while she was married to Danielson, Hurst also had a long affair with Arctic explorerVilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada.

Early life

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Arnes, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. His parents had ...

.Fannie Hurst. ''Anatomy of Me: A Wonderer in Search of Herself'' (p. 219). New York: Doubleday, 1958. .Gísli Pálsson. ''Travelling Passions: The Hidden Life Of Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada.

Early life

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Arnes, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. His parents had ...

'' (pp. 187, 195). Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

: University Press of New England

The University Press of New England (UPNE), located in Lebanon, New Hampshire and founded in 1970, was a university press consortium including Brandeis University, Dartmouth College (its host member), Tufts University, the University of New Ham ...

, 2005; .Robert Shulman. ''Romany Marie

Marie Marchand (May 17, 1885, Băbeni, Vâlcea County—February 20, 1961, Greenwich Village, New York), known as Romany Marie, was a Greenwich Village restaurateur who played a key role in bohemianism from the early 1900s through the late 195 ...

: The Queen of Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

'' (p. 144). Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

: Butler Books, 2006; . They often met at Romany Marie

Marie Marchand (May 17, 1885, Băbeni, Vâlcea County—February 20, 1961, Greenwich Village, New York), known as Romany Marie, was a Greenwich Village restaurateur who played a key role in bohemianism from the early 1900s through the late 195 ...

's café

A coffeehouse, coffee shop, or café is an establishment that primarily serves coffee of various types, notably espresso, latte, and cappuccino. Some coffeehouses may serve cold drinks, such as iced coffee and iced tea, as well as other non-c ...

in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

when Stefansson was in town. According to Stefansson, at one point Hurst considered divorcing Danielson in order to marry him, but decided against it. Hurst and Stefansson ended their relationship in 1939.

Hurst was friends with many leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

, including Carl Van Vechten and Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (January 7, 1891 – January 28, 1960) was an American author, anthropologist, and filmmaker. She portrayed racial struggles in the early-1900s American South and published research on hoodoo. The most popular of her four n ...

, who during her time at Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

worked as Hurst's secretary and later traveled with her. In 1958, Hurst published her autobiography, ''Anatomy of Me'', which described many of her friendships and encounters with famous people of the era such as Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Overweight as a child and young woman, Hurst had a lifelong concern about her weight. She was known in literary circles as an avid dieter and published an autobiographical memoir about her dieting, ''No Food With My Meals'', in 1935.

Hurst died on February 23, 1968, at her Hotel des Artistes apartment in Manhattan, after a brief illness. A few weeks before she died, she sent her publishers two new novels, one untitled and the other entitled ''Lonely is Only a Word''. Her obituary appeared on the front page of ''The New York Times''.

Major themes

Combining sentimentality with social realism, Hurst's fiction focuses on American (including immigrant) working-class and middle-class women who attempt to balance societal expectations and economic needs with their own desires for fulfillment. Many Hurst characters, male and female, are working people trying to rise above their class. Abe C. Ravitz described Hurst's themes as "women's issues expressed often in myths of sacrifice, suffering, and love" and Hurst herself as "the laureate of the ghetto and theNew Woman

The New Woman was a feminist ideal that emerged in the late 19th century and had a profound influence well into the 20th century. In 1894, Irish writer Sarah Grand (1854–1943) used the term "new woman" in an influential article, to refer to ...

". For readers unfamiliar with city life, Hurst's experiences allowed her to create accurate depictions of contemporaneous New York City and, in her later works, the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. She often dealt with subject matter considered "daringly frank and earthy" for its time, including unwed pregnancy, extramarital affairs, miscegnation, and homosexuality. Hurst's work has been criticized for relying heavily on stereotypes, including "The Cad, the Alcoholic, the Egotist, the Self-Absorbed Rich Lady, the Golden-Hearted Whore, the Brave Wife, the Pure-Minded Virgin, and the Honest Burgher".

Women in Hurst's works are generally victimized in some way by preconceived attitudes or social and economic discrimination. including sexual harassment

Sexual harassment is a type of harassment involving the use of explicit or implicit sexual overtones, including the unwelcome and inappropriate promises of rewards in exchange for sexual favors. Sexual harassment includes a range of actions fr ...

, gender discrimination

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls.There is a clear and broad consensus among academic scholars in multiple fields that sexism refers primar ...

, and age discrimination

Ageism, also spelled agism, is discrimination against individuals or groups on the basis of their age. The term was coined in 1969 by Robert Neil Butler to describe discrimination against seniors, and patterned on sexism and racism. Butler def ...

. Although Hurst's women often have jobs, economic security for women is typically portrayed as coming through marriage, or sometimes through being a well-paid mistress to a wealthy man. Women whose relationships fail to meet these standards, or who pursue a type of love relationship without economic benefits, suffer deprivation or meet with tragedy. The women's situations are frequently made worse by their own passivity, a trait Hurst deplored; a happy ending

A happy ending is an ending of the plot of a work of fiction in which almost everything turns out for the best for the main protagonists and their sidekicks, while the main villains/antagonists are dead/defeated.

In storylines where the protago ...

often either does not occur, or occurs because of outside forces rather than the afflicted woman's own efforts. Hurst also focused on describing the "interior lives of women" and how the life choices of her female characters are driven by feelings and passions that they often cannot articulate or explain.

Influence and legacy

In 1964, Hurst established her archive at theHarry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

with the assistance of her friend, the noted civil rights lawyer Morris Ernst

Morris Ernst (August 23, 1888 – May 21, 1976) was an American lawyer and prominent attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In public life, he defended and asserted the rights of Americans to privacy and freedom from censorshi ...

. The collection of over 270 boxes includes extensive manuscripts of her works (short stories, novels, film scenarios, plays, articles, columns, speeches, and talks), both incoming and outgoing correspondence, notebooks, wills, contracts, interviews, and biographical material.

Upon her death in 1968, Hurst left half of her estate to her alma mater, Washington University in St. Louis, and the other half to Brandeis University

, mottoeng = "Truth even unto its innermost parts"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = NECHE

, president = Ronald D. Liebowitz

, p ...

. The universities used the money to endow professorships in their respective English departments and to create "Hurst Lounges" for writers to share their work with academics and students.

At the time of her death, and for several decades thereafter, Hurst was treated as a popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

writer, credited with having "set the style followed by Jacqueline Susann, Judith Krantz

Judith Krantz (née Tarcher; January 9, 1928 – June 22, 2019) was a magazine writer and fashion editor who turned to fiction as she approached the age of 50. Her first novel '' Scruples'' (1978) quickly became a ''New York Times'' best-seller a ...

, and Jackie Collins

Jacqueline Jill Collins (4 October 1937 – 19 September 2015) was an English romance novelist and actress. She moved to Los Angeles in 1985 and spent most of her career there. She wrote 32 novels, all of which appeared on The New York Times B ...

" and considered "one of the great trash novelists". Her works fell into obscurity and largely went out of print. In the 1990s, Hurst's life and work again started to receive serious critical attention, including the formation of a Fannie Hurst Society for interested scholars; a volume of literary criticism by Abe C. Ravitz published in 1997; and a detailed biography of Hurst by Kroeger published in 1999.

In 2004, The Feminist Press

The Feminist Press (officially The Feminist Press at CUNY) is an American independent nonprofit literary publisher that promotes freedom of expression and social justice. It publishes writing by people who share an activist spirit and a belief in ...

published a collection of her stories from between the years 1912 and 1935, seeking to "propel a long overdue revival and reassessment of Hurst's work" and praising her "depth, intelligence, and artistry as a writer."

Other aspects of Hurst's life and work examined by scholars include her American Jewish background, her friendship with and patronage of Zora Neale Hurston (which Hurston discussed in her own autobiography), the treatment of racial issues in her novel ''Imitation of Life'' and the movies based upon it, and even her well-publicized dieting. She has also been called a pioneer in the field of public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

due to her development of her own strong public persona.

In popular culture

Hurst was a huge advocate for women maintaining independence their whole lives, even after marriage. In the 1920s, after Hurst revealed her marriage to Jacques Danielson, yet retained her own name and each had their own separate homes, the term "a Fannie Hurst marriage" was coined to describe a marital arrangement similar to Hurst's, where the husband and wife each maintained their own independent lives, even to the point of living in separate residences. Hurst has been referenced in popular culture to exemplify a popular or lowbrow author, in contrast to serious, literary authors. The theme song of the 1970Mel Brooks

Mel Brooks (born Melvin James Kaminsky; June 28, 1926) is an American actor, comedian and filmmaker. With a career spanning over seven decades, he is known as a writer and director of a variety of successful broad farces and parodies. He began ...

comedy film ''The Twelve Chairs

''The Twelve Chairs'' ( rus, Двенадцать стульев, Dvenadtsat stulyev) is a classic satirical novel by the Odesan Soviet authors Ilf and Petrov, published in 1928. Its plot follows characters attempting to obtain jewelry hidden ...

'' includes the lines, "Hope for the best, expect the worst/ You could be Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

or Fannie Hurst." Hurst is mentioned in a similar vein in the song "You're So London" by Mike Nichols

Mike Nichols (born Michael Igor Peschkowsky; November 6, 1931 – November 19, 2014) was an American film and theater director, producer, actor, and comedian. He was noted for his ability to work across a range of genres and for his aptitude fo ...

and Ken Welch, written for the show ''Julie and Carol at Carnegie Hall

''Julie and Carol at Carnegie Hall'' is an American musical comedy television special starring Julie Andrews and Carol Burnett, broadcast on CBS on June 11, 1962.

Development

The special was produced by Bob Banner and directed by Joe Hamilton. ...

'' (1962): "You're so kippers

A kipper is a whole herring, a small, oily fish, that has been split in a butterfly fashion from tail to head along the dorsal ridge, gutted, salted or pickled, and cold-smoked over smouldering wood chips (typically oak).

In the United King ...

, you're so caviar

Caviar (also known as caviare; from fa, خاویار, khâvyâr, egg-bearing) is a food consisting of salt-cured roe of the family Acipenseridae. Caviar is considered a delicacy and is eaten as a garnish or a spread. Traditionally, the te ...

and I'm so liverwurst

Liverwurst, leberwurst, or liver sausage is a kind of sausage made from liver. It is eaten in many parts of Europe, including Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Polan ...

/ You're so Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, so Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

and I'm so Fannie Hurst."

Selected works

Short story collections

*''Just Around the Corner'' (1914) *''Every Soul Hath Its Song'' (1916) *''Gaslight Sonatas'' (1918) *''Humoresque: A Laugh on Life with a Tear Behind It'' (1919) *''The Vertical City'' (1922) *''Song of Life'' (1927) *''Procession'' (1929) *''We are Ten'' (1937)Novels

*''Star-Dust: The Story of an American Girl'' (1921) *''Lummox'' (1923) *''Mannequin'' (1926) *''Appassionata'' (1926) *''A President is Born'' (1928) *''Five and Ten'' (1929) *''Back Street'' (1931) *'' Imitation of Life'' (1933) *''Anitra's Dance'' (1934) *''Great Laughter'' (1936) *''Lonely Parade'' (1942) *''Hallelujah'' (1944) *''The Hands of Veronica'' (1947) *''Anywoman'' (1950) *''The Name is Mary'' (1951) *''The Man with One Head'' (1951) *''Family!'' (1960) *''God Must Be Sad'' (1961) *''Fool, Be Still'' (1964)Autobiography

*''Anatomy of Me: A Wonderer in Search of Herself'' (1958)Other books

*''No Food with My Meals'' (1935) (non-fiction autobiographical memoir about dieting) *''Today is Ladies' Day'' (1939) (Home Institute booklet, offered through newspapers) *''White Christmas'' (1942) (short fiction,Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

story)

Stage plays

* ''The Official Chaperon'' (1909) (produced at Washington University in St. Louis) *''The Land of the Free'' (1917) (co-written with Harriet Ford) *''Back Pay'' (1921) (adaptation by Hurst of her 1919 short story of the same name) *''Humoresque'' (1923) (adaptation by Hurst of her 1918 short story of the same name) *''It Is To Laugh'' (1927) (adaptation by Hurst of her short story "The Gold in Fish" (1925)) *''Four Daughters'' (1941) (story credit; stage play was adapted by Frank Vreeland from Hurst's short story "Sister Act")Film credits

*'' Humoresque'' (1920) *'' Lummox'' (1930), based on 1923 novel; also dialogue *''Symphony of Six Million

''Symphony of Six Million'' is a 1932 American Pre-Code film directed by Gregory La Cava and starring Ricardo Cortez, Irene Dunne and Gregory Ratoff. Based on the story ''Night Bell'' by Fannie Hurst, the film concerns the rise of a Jewish ph ...

'' (1932), based on story "Night Bell"

*'' Back Street'' (1932), based on novel

*'' Imitation of Life'' (1934), based on the novel

*'' Back Street'' (1941), based on novel

*'' Humoresque'' (1946), based on story

*'' Imitation of Life'' (1959), based on novel

References

Bibliography

*External links

Fannie Hurst Papers

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

Fannie Hurst Papers

at Washington University in St. Louis

Fannie Hurst Collection

at

Brandeis University

, mottoeng = "Truth even unto its innermost parts"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = NECHE

, president = Ronald D. Liebowitz

, p ...

*

*

*

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hurst, Fannie

1889 births

1968 deaths

20th-century American novelists

Screenwriters from Ohio

People from Hamilton, Ohio

Writers from St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis alumni

American women screenwriters

Novelists from Ohio

Jewish American novelists

Writers from New York City

American women novelists

20th-century American women writers

Novelists from Missouri

Novelists from New York (state)

Screenwriters from Missouri

Screenwriters from New York (state)

Members of the Society of Woman Geographers

20th-century American screenwriters