European exploration of Australia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The European exploration of Australia first began in February 1606, when Dutch navigator

The European exploration of Australia first began in February 1606, when Dutch navigator

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, the " First Fleet", under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, to establish a new

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, the " First Fleet", under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, to establish a new

In 1798–99

In 1798–99

The European exploration of Australia first began in February 1606, when Dutch navigator

The European exploration of Australia first began in February 1606, when Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ), sometimes abbreviated to Willem Jansz., was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. Janszoon served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 16031611 and 16121616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of S ...

landed in Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupació ...

and on October that year when Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sailed through, and navigated, Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost extremity of the Australian mai ...

islands. Twenty-nine other Dutch navigators explored the western and southern coasts in the 17th century, and dubbed the continent New Holland.

Other European explorers followed until, in 1770, Lieutenant James Cook charted the east coast of Australia for Great Britain. Later, after Cook's death, Joseph Banks recommended sending convicts to Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

(now in Sydney), New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. A First Fleet of British ships arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788 to establish a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

, the first colony on the Australian mainland

Mainland Australia is the main landmass of the Australian continent, excluding the Aru Islands, New Guinea, Tasmania, and other Australian offshore islands. The landmass also constitutes the mainland of the territory governed by the Commonwea ...

. In the century that followed, the British established other colonies on the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas t ...

, and European explorers ventured into its interior.

Massive areas of land were cleared for agriculture and various other purposes in the first 100 years of European settlement. In addition to the obvious impacts this early clearing of land and importation of hard-hoofed animals had on the ecology of particular regions, it severely affected indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

, by reducing the resources they relied on for food, shelter and other essentials. This progressively forced them into smaller areas and reduced their numbers as the majority died of newly introduced diseases and lack of resources. Indigenous resistance against the settlers was widespread, and prolonged fighting between 1788 and the 1920s led to the deaths of at least 20,000 indigenous people and between 2,000 and 2,500 Europeans.

European Discovery

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

explorers, in 1606, made the first recorded European sightings and first recorded landfalls of the Australian mainland. The first ship and crew to chart the Australian coast and meet with Aboriginal people was the ''Duyfken

''Duyfken'' (; Little Dove), also in the form ''Duifje'' or spelled ''Duifken'' or ''Duijfken'', was a small ship built in the Dutch Republic. She was a fast, lightly armed ship probably intended for shallow water, small valuable cargoes, bri ...

'' captained by Dutch navigator, Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ), sometimes abbreviated to Willem Jansz., was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. Janszoon served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 16031611 and 16121616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of S ...

. He sighted the coast of Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupació ...

in early 1606, and made landfall on 26 February at the Pennefather River

The Pennefather River is a river located on the western Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland, Australia.

Location and features

Formed by the confluence of a series of waterways including the Fish Creek in the Port Musgrave Aggregation ...

near the modern town of Weipa on Cape York.. The Dutch charted the whole of the western and northern coastlines and named the island continent " New Holland" during the 17th century, but made no attempt at settlement. William Dampier

William Dampier (baptised 5 September 1651; died March 1715) was an English explorer, pirate, privateer, navigator, and naturalist who became the first Englishman to explore parts of what is today Australia, and the first person to circumnav ...

, an English explorer and privateer, landed on the north-west coast of New Holland in 1688 and again in 1699 on a return trip.

The Dutch, following shipping routes to the Dutch East Indies to trade in spices, china and silk, proceeded to contribute a great deal to Europe's knowledge of Australia's coast.Manning Clark; A Short History of Australia; Penguin Books; 2006; p. 6 In 1616, Dirk Hartog

Dirk Hartog (; baptised 30 October 1580 – buried 11 October 1621) was a 17th-century Dutch sailor and explorer. Dirk Hartog's expedition was the second European group to land in Australia and the first to leave behind an artefact to record his ...

, sailing off course, en route from the Cape of Good Hope to Batavia, landed on an island off Shark Bay, West Australia. In 1622–23 the made the first recorded rounding of the south west corner of the continent, and gave her name to Cape Leeuwin

Cape Leeuwin is the most south-westerly (but not most southerly) mainland point of the Australian continent, in the state of Western Australia.

Description

A few small islands and rocks, the St Alouarn Islands, extend further in Flinders ...

.

In 1627 the south coast of Australia was accidentally encountered by François Thijssen

François Thijssen or Frans Thijsz (died 13 October 1638?) was a Dutch-French explorer who explored the southern coast of Australia.

He was the captain of the ship t Gulden Zeepaerdt'' (''The Golden Seahorse'') when sailing from Cape of Good Ho ...

and named t Land van Pieter Nuyts'', in honour of the highest ranking passenger, Pieter Nuyts

Pieter Nuyts or Nuijts (born 1598 – 11 December 1655) was a Dutch explorer, diplomat and politician.

He was part of a landmark expedition of the Dutch East India Company in 1626–27 which mapped the southern coast of Australia. He became t ...

, extraordinary Councillor of India. In 1628 a squadron of Dutch ships was sent by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies Pieter de Carpentier

Pieter de Carpentier (19 February 1586 – 5 September 1659) was a Dutch administrator of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) who served as Governor-General there from 1623 to 1627. The Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia is named after him. ...

to explore the northern coast. These ships made extensive examinations, particularly in the Gulf of Carpentaria, named in honour of de Carpentier.

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

's voyage of 1642 was the first known European expedition to reach Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

(later Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

) and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, and to sight Fiji. On his second voyage of 1644, he also contributed significantly to the mapping of Australia proper, making observations on the land and people of the north coast below New Guinea.

A map of the world inlaid into the floor of the ''Burgerzaal'' (" Burger's Hall") of the new Amsterdam ''Stadhuis'' ("Town Hall") in 1655 revealed the extent of Dutch charts of much of Australia's coast. Based on the 1648 map by Joan Blaeu

Joan Blaeu (; 23 September 1596 – 21 December 1673) was a Dutch cartographer born in Alkmaar, the son of cartographer Willem Blaeu.

Life

In 1620, Blaeu became a doctor of law but he joined the work of his father. In 1635, they publish ...

, ''Nova et Accuratissima Terrarum Orbis Tabula'', it incorporated Tasman's discoveries, subsequently reproduced in the map, ''Archipelagus Orientalis sive Asiaticus'' published in the ''Kurfürsten Atlas (Atlas of the Great Elector).''

In 1664 the French geographer Melchisédech Thévenot published a map of New Holland in ''Relations de Divers Voyages Curieux''. Thévenot divided the continent in two, between ''Nova Hollandia'' to the west and ''Terre Australe'' to the east. Emanuel Bowen

Emanuel Bowen (1694 – 8 May 1767) was a Welsh map engraver, who achieved the unique distinction of becoming Royal Mapmaker to both to King George II of Great Britain and Louis XV of France. Bowen was highly regarded by his contemporaries for p ...

reproduced Thevenot's map in his ''Complete System of Geography'' (London, 1747), re-titling it ''A Complete Map of the Southern Continent'' and adding three inscriptions promoting the benefits of exploring and colonising the country. One inscription said:

In 1770, James Cook sailed along and mapped the east coast, which he named New South Wales and claimed for Great Britain.

Colonisation

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, the " First Fleet", under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, to establish a new

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, the " First Fleet", under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, to establish a new penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

in New South Wales. A camp was set up and the flag raised at Sydney Cove, Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman Sea ...

, on 26 January 1788, a date which became Australia's national day, Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and raising of the Union Flag by Arthur Phillip following days of exploration of Port ...

. Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils, fixed on the Parramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major Central business district, commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the ban ...

region as a promising area for expansion, and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life.

Seventeen years after Cook's landfall on the east coast of Australia, the British government decided to establish a colony at Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

. Following the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783), Britain lost most of its territory in North America and considered establishing replacement colonies. In 1779 Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James C ...

, the eminent scientist who had accompanied James Cook on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

as a suitable site for settlement, saying that "it was not to be doubted that a Tract of Land such as New Holland, which was larger than the whole of Europe, would furnish Matter of advantageous Return".

Georg Forster

Johann George Adam Forster, also known as Georg Forster (, 27 November 1754 – 10 January 1794), was a German naturalist, ethnologist, travel writer, journalist and revolutionary. At an early age, he accompanied his father, Johann Reinhold ...

, who had sailed under Lieutenant James Cook in the voyage of the (1772–1775), wrote in 1786 on the future prospects of the British colony: "New Holland, an island of enormous extent or it might be said, a third continent, is the future homeland of a new civilized society which, however mean its beginning may seem to be, nevertheless promises within a short time to become very important."

Britain claimed territory encompassing all of Australia eastward of the meridian of 135° East and all the islands in the Pacific Ocean between the latitudes of Cape York and the southern tip of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

(Tasmania). The western limit of 135° East was set at the meridian dividing ''New Holland'' from ''Terra Australis,'' as shown on Emanuel Bowen

Emanuel Bowen (1694 – 8 May 1767) was a Welsh map engraver, who achieved the unique distinction of becoming Royal Mapmaker to both to King George II of Great Britain and Louis XV of France. Bowen was highly regarded by his contemporaries for p ...

's ''Complete Map of the Southern Continent'', published in John Campbell's editions of John Harris' ''Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels'' (1744–1748, and 1764). It was a vast claim which elicited excitement at the time: the Dutch translator of First Fleet officer and author Watkin Tench

Lieutenant General Watkin Tench (6 October 1758 – 7 May 1833) was a British marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first European settlement in Australia in ...

's ''A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay'' wrote: "a single province which, beyond all doubt, is the largest on the whole surface of the earth. From their definition it covers, in its greatest extent from East to West, virtually a fourth of the whole circumference of the Globe."

A British settlement was established in 1803 in Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

, now known as Tasmania, and it became a separate colony in 1825.. The United Kingdom formally claimed the western part of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

(the Swan River Colony) in 1828.. Separate colonies were carved from parts of New South Wales: South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

in 1836, Victoria in 1851, and Queensland in 1859.. The Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory shares its borders with Western Aust ...

was founded in 1911 when it was excised from South Australia.. South Australia was founded as a "free province"—it was never a penal colony.. Victoria and Western Australia were also founded "free", but later accepted transported convicts.. A campaign by the settlers of New South Wales led to the end of convict transportation to that colony; the last convict ship arrived in 1848.

Exploration of the continent

Early days

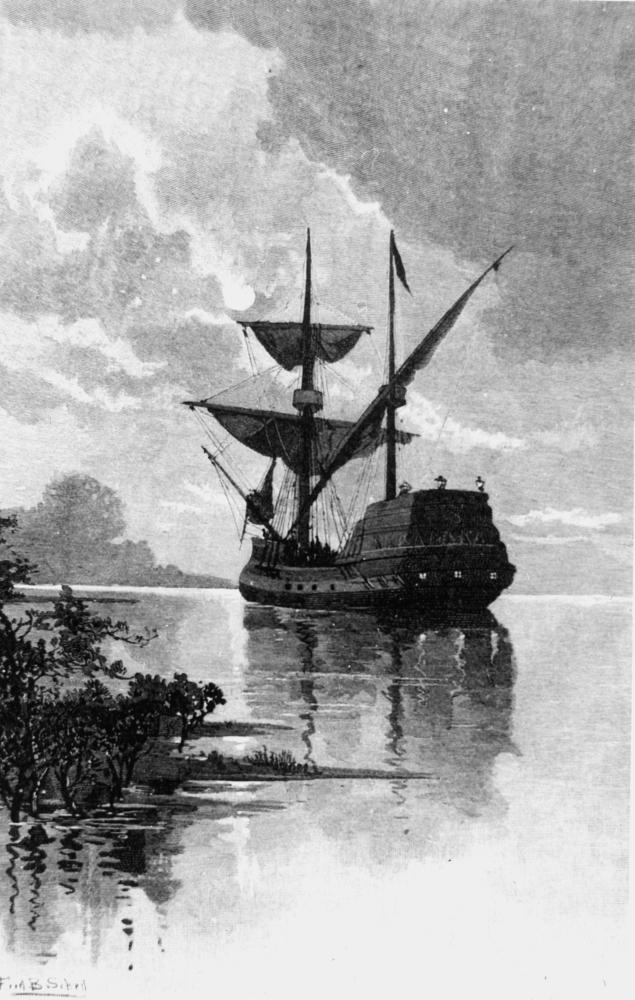

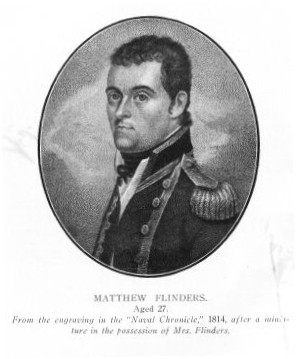

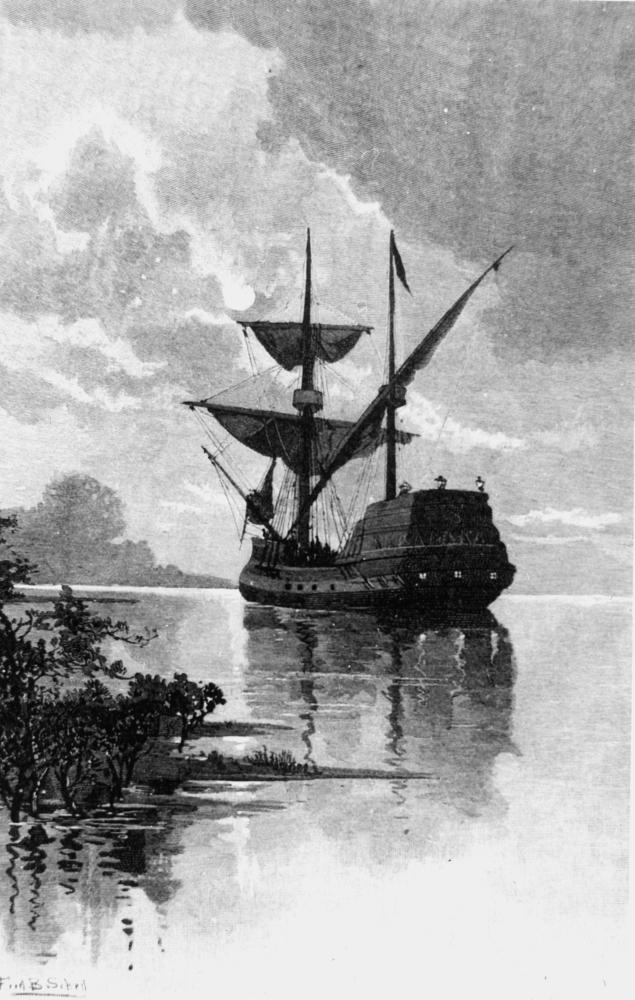

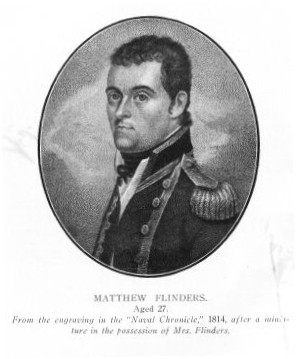

In 1798–99

In 1798–99 George Bass

George Bass (; 30 January 1771 – after 5 February 1803) was a British naval surgeon and explorer of Australia.

Early years

Bass was born on 30 January 1771 at Aswarby, a hamlet near Sleaford, Lincolnshire, the son of a tenant farmer, George ...

and Matthew Flinders set out from Sydney in a sloop and circumnavigated Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, thus proving it to be an island, following a failed attempt to settle at Sullivan Bay in what is now Victoria. In 1801–02 Matthew Flinders in led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree

Bungaree, or Boongaree ( – 24 November 1830), was an Aboriginal Australian from the Guringai people of the Broken Bay north of Sydney, who was known as an explorer, entertainer, and Aboriginal community leader.Barani (2013)Significant Aborig ...

, of the Sydney district, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Bennelong and a companion had become the first people born in the area of New South Wales to sail for Europe, when, in 1792 they accompanied Governor Phillip to England and were presented to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

.

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland

Gregory Blaxland (17 June 1778 – 1 January 1853) was an English pioneer farmer and explorer in Australia, noted especially for initiating and co-leading the first successful crossing of the Blue Mountains by European settlers.

Early life ...

, William Lawson and William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth (August 179020 March 1872) was an Australian pastoralist, explorer, newspaper editor, lawyer, politician and author, who became one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures of early colonial New South Wales.

Throug ...

succeeded in crossing the formidable barrier of forested gulleys and sheer cliffs presented by the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. At Mount Blaxland they looked out over "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years", and expansion of the British settlement into the interior could begin.

1820s–1830s

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane commissionedHamilton Hume

Hamilton Hume (19 June 1797 – 19 April 1873) was an early explorer of the present-day Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria. In 1824, along with William Hovell, Hume participated in an expedition that first took an overland rout ...

and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell

William Hilton Hovell (26 April 1786 – 9 November 1875) was an English explorer of Australia. With Hamilton Hume, he made an 1824 overland expedition from Sydney to Port Phillip (near the site of present-day Melbourne), and later explored the ...

to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales' western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824–25, Hume and Hovell journeyed to Port Phillip and back. They made many important discoveries including the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray) (Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta: ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is Australia's longest river at extent. Its tributaries include five of the next six longest ...

(which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales

Gunning is a small town on the Old Hume Highway, between Goulburn and Yass in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia, about 260 km south-west of Sydney and 75 km north of the national capital, Canberra. (Nearby towns ar ...

and Corio Bay, Port Phillip

Port Phillip ( Kulin: ''Narm-Narm'') or Port Phillip Bay is a horsehead-shaped enclosed bay on the central coast of southern Victoria, Australia. The bay opens into the Bass Strait via a short, narrow channel known as The Rip, and is com ...

.

Charles Sturt

Charles Napier Sturt (28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869) was a British officer and explorer of Australia, and part of the European exploration of Australia. He led several expeditions into the interior of the continent, starting from Sydney and la ...

led an expedition along the Macquarie River

The Macquarie River - Wambuul is part of the Macquarie– Barwon catchment within the Murray–Darling basin, is one of the main inland rivers in New South Wales, Australia.

The river rises in the central highlands of New South Wales near the ...

in 1828, becoming the first European to encounter the Darling River

The Darling River (Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka'') is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its conflu

ence with the Murray River at Wentworth, New South Wales. Including its long ...

. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River

The Murrumbidgee River () is a major tributary of the Murray River within the Murray–Darling basin and the second longest river in Australia. It flows through the Australian state of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, desce ...

into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party followed this river to its junction with the Darling River

The Darling River (Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka'') is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its conflu

ence with the Murray River at Wentworth, New South Wales. Including its long ...

, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued down river to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia. Suffering greatly, the party had to row hundreds of kilometres back upstream for the return journey.

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.

In 1836, two ships of the South Australia Land Company left to establish the first settlement on Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

. The foundation of South Australia is now generally commemorated as Governor John Hindmarsh's Proclamation of the new Province at Glenelg, on the mainland, on 28 December 1836.

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps

The Australian Alps is a mountain range in southeast Australia. It comprises an interim Australian bioregion,0042-5184 However, the moth has also been a biovector of arsenic, transporting it from lowland feeding sites over long distances int ...

in 1839. He became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko

Mount Kosciuszko ( ; Ngarigo: , ), previously spelled Mount Kosciusko, is mainland Australia's tallest mountain, at 2,228 metres (7,310 ft) above sea level. It is located on the Main Range of the Snowy Mountains in Kosciuszko National ...

in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

.

Other British settlements followed, at various points around the continent, many of them unsuccessful. The East India Trade Committee recommended in 1823 that a settlement be established on the coast of northern Australia to forestall the Dutch, and Captain J.J.G. Bremer, RN, was commissioned to form a settlement between Bathurst Island and the Cobourg Peninsula

The Cobourg Peninsula is located east of Darwin in the Northern Territory, Australia. It is deeply indented with coves and bays, covers a land area of about , and is virtually uninhabited with a population ranging from about 20 to 30 in five ...

. Bremer fixed the site of his settlement at Fort Dundas

Fort Dundas was a short-lived British settlement on Melville Island between 1824 and 1828 in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia. It was the first of four British settlement attempts in northern Australia before Goyder's survey a ...

on Melville Island in 1824. Because this was well to the west of the boundary proclaimed in 1788, he proclaimed British sovereignty over all the territory as far west as longitude 129° East.

The new boundary included Melville and Bathurst islands, and the adjacent mainland. In 1826, the British claim was extended to the whole Australian continent when Major Edmund Lockyer

Edmund Lockyer, (21 January 1784 – 10 June 1860) was a British soldier and explorer of Australia.

Born in Plymouth, Devon, Lockyer was the son of Thomas Lockyer, a sailmaker, and his wife Ann. Lockyer began his army career as an ensign in ...

established a settlement on King George Sound

King George Sound ( nys , Menang Koort) is a sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came into use ...

(the basis of the later town of Albany), but the eastern border of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

remained unchanged at longitude 129° East. In 1824, a penal colony was established near the mouth of the Brisbane River (the basis of the later colony of Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

). In 1829, the Swan River Colony and its capital of Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

were founded on the west coast proper and also assumed control of King George Sound. Initially a free colony, Western Australia later accepted British convicts, because of suffering a lack of settlers and an acute labour shortage.

The colony of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

was settled in 1836, with its western and eastern boundaries set at 132° and 141° East of Greenwich, and to the north at latitude 26° South. The western and eastern boundary points were chosen as they marked the extent of coastline first surveyed by Matthew Flinders in 1802 (Nicolas Baudin

Nicolas Thomas Baudin (; 17 February 1754 – 16 September 1803) was a French explorer, cartographer, naturalist and hydrographer, most notable for his explorations in Australia and the southern Pacific.

Biography

Early career

Born a comm ...

's priority being ignored). The British Parliament set the northern boundary at the parallel of latitude 26° South, because they believed that was the limit of effective control of territory that could be exercised by a settlement founded on the shores of Gulf St Vincent

Gulf St Vincent, sometimes referred to as St Vincent Gulf, St Vincent's Gulf or Gulf of St Vincent, is the eastern of two large inlets of water on the southern coast of Australia, in the state of South Australia, the other being the larger S ...

. The South Australian Company

The South Australian Company, also referred to as the South Australia Company, was formed in London on 9 October 1835, after the '' South Australia (Foundation) Act 1834'' had established the new British Province of South Australia, with the S ...

had proposed the parallel of 20° South, later reduced to the Tropic of Capricorn

The Tropic of Capricorn (or the Southern Tropic) is the circle of latitude that contains the subsolar point at the December (or southern) solstice. It is thus the southernmost latitude where the Sun can be seen directly overhead. It also reac ...

(the parallel of latitude 23° 37′ South).

Into the interior

European explorers made their last great, often arduous and sometimes tragic expeditions into the interior of Australia during the second half of the 19th century—some with the official sponsorship of the colonial authorities and others commissioned by private investors. By 1850, large areas of the inland were still unknown to Europeans. Trailblazers likeEdmund Kennedy

Edmund Besley Court Kennedy J. P. (5 September 1818 – December 1848) was an explorer in Australia in the mid nineteenth century. He was the Assistant-Surveyor of New South Wales, working with Sir Thomas Mitchell. Kennedy explored the interio ...

and the Prussian naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt had met tragic ends attempting to fill in the gaps during the 1840s, but explorers remained ambitious to discover new lands for agriculture or answer scientific enquiries. Surveyors also acted as explorers and the colonies sent out expeditions to discover the best routes for lines of communication. The size of expeditions varied considerably from small parties of just two or three to large, well-equipped teams led by gentlemen explorers assisted by smiths, carpenters, labourers and Aboriginal guides accompanied by horses, camels or bullocks.

From 1858 onwards, the so-called "Afghan" cameleers and their beasts played an instrumental role in opening up the outback and helping to build infrastructure.

In 1860, the ill-fated Burke and Wills

The Burke and Wills expedition was organised by the Royal Society of Victoria in Australia in 1860–61. It consisted of 19 men led by Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills, with the objective of crossing Australia from Melbourne in the ...

led the first north-south crossing of the continent from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Lacking bushcraft and unwilling to learn from the local Aboriginal people, Burke and Wills died in 1861, having returned from the Gulf to their rendezvous point at Coopers Creek only to discover the rest of their party had departed the location only a matter of hours previously. Though an impressive feat of navigation, the expedition was an organisational disaster which continues to fascinate the Australian public.

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart succeeded in traversing Central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped out the route which was later followed by the Australian Overland Telegraph Line.Tim Flannery; ''The Explorers''; Text Publishing 1998

Uluru

Uluru (; pjt, Uluṟu ), also known as Ayers Rock ( ) and officially gazetted as UluruAyers Rock, is a large sandstone formation in the centre of Australia. It is in the southern part of the Northern Territory, southwest of Alice Spring ...

and Kata Tjuta

Kata Tjuṯa / The Olgas (Pitjantjatjara: , lit. 'many heads'; ) is a group of large, domed rock formations or bornhardts located about southwest of Alice Springs, in the southern part of the Northern Territory, central Australia. Uluṟu / Aye ...

were first mapped by Europeans in 1872 during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line. In separate expeditions, Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first European explorers to this area. While exploring the area in 1872, Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga, while the following year Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honour of the Chief Secretary of South Australia The Chief Secretary of South Australia (since 1856) or Colonial Secretary of South Australia (1836–1856) was a key role in the governance of the Colony of South Australia (1836–1900) and State of South Australia (from 1901) until it was abolishe ...

, Sir Henry Ayers

Sir Henry Ayers (now pron. "airs") (1 May 1821 – 11 June 1897) was the eighth Premier of South Australia, serving a record five times between 1863 and 1873.

His lasting memorial is in the name Ayers Rock, also known as Uluru, which was en ...

. These barren desert lands of Central Australia disappointed the Europeans as unpromising for pastoral expansion, but would later come to be appreciated as emblematic of Australia.

References

Further reading

* * *Sources

* {{Authority control 1605 establishments in Australia Exploration of Australia Dutch exploration in the Age of Discovery