Ernest Lawrence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American

Lawrence saw that such a

Lawrence saw that such a

When he returned to Berkeley, Lawrence mobilized his team to go painstakingly over the results to gather enough evidence to convince Chadwick. Meanwhile, at the Cavendish laboratory, Rutherford and Mark Oliphant found that deuterium

When he returned to Berkeley, Lawrence mobilized his team to go painstakingly over the results to gather enough evidence to convince Chadwick. Meanwhile, at the Cavendish laboratory, Rutherford and Mark Oliphant found that deuterium

In September 1941, Oliphant met with Lawrence and Oppenheimer at Berkeley, where they showed him the site for the new cyclotron. Oliphant, in turn, took the Americans to task for not following up the recommendations of the British

In September 1941, Oliphant met with Lawrence and Oppenheimer at Berkeley, where they showed him the site for the new cyclotron. Oliphant, in turn, took the Americans to task for not following up the recommendations of the British

Notwithstanding the fact that he voted for

Notwithstanding the fact that he voted for

Ernest O. Lawrence Annotated Bibliography for Ernest Lawrence from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Lawrence and the Cyclotron: AIP History Center Web Exhibit

''Lawrence and His Laboratory: A Historian's View of the Lawrence Years''

* Lawrence Livermore Lab

* * Nobel-Winners.com

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lawrence, Ernest 1901 births 1958 deaths 20th-century American physicists American Nobel laureates Accelerator physicists American nuclear physicists Enrico Fermi Award recipients Experimental physicists Manhattan Project people Nobel laureates in Physics American people of Norwegian descent People from Canton, South Dakota Scientists from South Dakota University of California, Berkeley faculty University of Chicago alumni University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering alumni University of South Dakota alumni Yale University alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Foreign Fellows of the Indian National Science Academy Medal for Merit recipients Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Mass spectrometrists American people of World War II Fellows of the American Physical Society Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Inventors from South Dakota

nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Jan ...

. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation for the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, as well as for founding the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

.

A graduate of the University of South Dakota

The University of South Dakota (USD) is a public research university in Vermillion, South Dakota. Established by the Dakota Territory legislature in 1862, 27 years before the establishment of the state of South Dakota, USD is the flagship uni ...

and University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

, Lawrence obtained a PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* '' Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. al ...

in physics at Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

in 1925. In 1928, he was hired as an associate professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant un ...

, becoming the youngest full professor there two years later. In its library one evening, Lawrence was intrigued by a diagram of an accelerator that produced high-energy particles. He contemplated how it could be made compact, and came up with an idea for a circular accelerating chamber between the poles of an electromagnet

An electromagnet is a type of magnet in which the magnetic field is produced by an electric current. Electromagnets usually consist of wire wound into a coil. A current through the wire creates a magnetic field which is concentrated in ...

. The result was the first cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Jan ...

.

Lawrence went on to build a series of ever larger and more expensive cyclotrons. His Radiation Laboratory became an official department of the University of California in 1936, with Lawrence as its director. In addition to the use of the cyclotron for physics, Lawrence also supported its use in research into medical uses of radioisotopes. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Lawrence developed electromagnetic isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" ...

at the Radiation Laboratory. It used devices known as calutron

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was deri ...

s, a hybrid of the standard laboratory mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

and cyclotron. A huge electromagnetic separation plant was built at Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's popu ...

, which came to be called Y-12. The process was inefficient, but it worked.

After the war, Lawrence campaigned extensively for government sponsorship of large scientific programs, and was a forceful advocate of " Big Science", with its requirements for big machines and big money. Lawrence strongly backed Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

's campaign for a second nuclear weapons laboratory, which Lawrence located in Livermore, California

Livermore (formerly Livermorès, Livermore Ranch, and Nottingham) is a city in Alameda County, California. With a 2020 population of 87,955, Livermore is the most populous city in the Tri-Valley. It is located on the eastern edge of Californi ...

. After his death, the Regents of the University of California

The Regents of the University of California (also referred to as the Board of Regents to distinguish the board from the corporation it governs of the same name) is the governing board of the University of California (UC), a state university sy ...

renamed the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

after him. Chemical element number 103 was named lawrencium

Lawrencium is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Lr (formerly Lw) and atomic number 103. It is named in honor of Ernest Lawrence, inventor of the cyclotron, a device that was used to discover many artificial radioactive elements. A radio ...

in his honor after its discovery at Berkeley in 1961.

Early life

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was born inCanton, South Dakota

Canton is a city in and the county seat of Lincoln County, South Dakota, United States. Canton is located 20 minutes south of Sioux Falls in southeastern South Dakota. Canton is nestled in the rolling hills of the Sioux Valley, providing an a ...

, on August 8, 1901. His parents, Carl Gustavus and Gunda (née Jacobson) Lawrence, were both the offspring of Norwegian immigrants who had met while teaching at the high school in Canton, where his father was also the superintendent of schools. He had a younger brother, John H. Lawrence

John Hundale Lawrence (January 7, 1904 – September 7, 1991) was an American physicist and physician best known for pioneering the field of nuclear medicine.

Background

John Hundale Lawrence was born in Canton, South Dakota. His parents, Carl Gu ...

, who would become a physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, and was a pioneer in the field of nuclear medicine

Nuclear medicine or nucleology is a medical specialty involving the application of radioactive substances in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. Nuclear imaging, in a sense, is " radiology done inside out" because it records radiation emi ...

. Growing up, his best friend was Merle Tuve

Merle Anthony Tuve (June 27, 1901 – May 20, 1982) was an American geophysicist who was the Chairman of the Office of Scientific Research and Development's Section T, which was created in August 1940. He was founding director of the Johns Hopkins ...

, who would also go on to become a highly accomplished physicist.

Lawrence attended the public schools of Canton and Pierre

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

, then enrolled at St. Olaf College

St. Olaf College is a private liberal arts college in Northfield, Minnesota. It was founded in 1874 by a group of Norwegian-American pastors and farmers led by Pastor Bernt Julius Muus. The college is named after the King and the Patron Saint Olaf ...

in Northfield, Minnesota

Northfield is a city in Dakota and Rice counties in the State of Minnesota. It is mostly in Rice County, with a small portion in Dakota County. The population was 20,790 at the 2020 census.

History

Northfield was platted in 1856 by John W ...

, but transferred after a year to the University of South Dakota

The University of South Dakota (USD) is a public research university in Vermillion, South Dakota. Established by the Dakota Territory legislature in 1862, 27 years before the establishment of the state of South Dakota, USD is the flagship uni ...

in Vermillion. He completed his bachelor's degree in chemistry in 1922, and his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

(M.A.) degree in physics from the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

in 1923 under the supervision of William Francis Gray Swann. For his master's thesis, Lawrence built an experimental apparatus that rotated an ellipsoid

An ellipsoid is a surface that may be obtained from a sphere by deforming it by means of directional scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

An ellipsoid is a quadric surface; that is, a surface that may be defined as th ...

through a magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

.

Lawrence followed Swann to the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, and then to Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134 ...

, where Lawrence completed his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

(PhD) degree in physics in 1925 as a Sloane Fellow, writing his doctoral thesis on the photoelectric effect

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons when electromagnetic radiation, such as light, hits a material. Electrons emitted in this manner are called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is studied in condensed matter physics, and solid sta ...

in potassium vapor. He was elected a member of Sigma Xi

Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society () is a highly prestigious, non-profit honor society for scientists and engineers. Sigma Xi was founded at Cornell University by a junior faculty member and a small group of graduate students in 1886 ...

, and, on Swann's recommendation, received a National Research Council fellowship. Instead of using it to travel to Europe, as was customary at the time, he remained at Yale University with Swann as a researcher.

With Jesse Beams

Jesse Wakefield Beams (December 25, 1898 in Belle Plaine, Kansas – July 23, 1977) was an American physicist at the University of Virginia.

Biography

Beams completed his undergraduate B.A. in physics at Fairmount College in 1921 and his mas ...

from the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

, Lawrence continued to research the photoelectric effect. They showed that photoelectrons appeared within 2 x 10−9 seconds of the photons striking the photoelectric surface—close to the limit of measurement at the time. Reducing the emission time by switching the light source on and off rapidly made the spectrum of energy emitted broader, in conformance with Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematis ...

's uncertainty principle

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle (also known as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle) is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the accuracy with which the values for certain pairs of physic ...

.

Early career

In 1926 and 1927, Lawrence received offers ofassistant professor

Assistant Professor is an academic rank just below the rank of an associate professor used in universities or colleges, mainly in the United States and Canada.

Overview

This position is generally taken after earning a doctoral degree

A docto ...

ships from the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seatt ...

in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

and the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, University of Califor ...

at a salary of $3,500 per annum. Yale promptly matched the offer of the assistant professorship, but at a salary of $3,000. Lawrence chose to stay at the more prestigious Yale, but because he had never been an instructor, the appointment was resented by some of his fellow faculty, and in the eyes of many it still did not compensate for his South Dakota immigrant background.

Lawrence was hired as an associate professor

Associate professor is an academic title with two principal meanings: in the North American system and that of the ''Commonwealth system''.

Overview

In the '' North American system'', used in the United States and many other countries, it is ...

of physics at the University of California in 1928, and two years later became a full professor, becoming the university's youngest professor. Robert Gordon Sproul, who became university president the day after Lawrence became a professor, was a member of the Bohemian Club

The Bohemian Club is a private club with two locations: a city clubhouse in the Nob Hill district of San Francisco, California and the Bohemian Grove, a retreat north of the city in Sonoma County. Founded in 1872 from a regular meeting of journ ...

, and he sponsored Lawrence's membership in 1932. Through this club, Lawrence met William Henry Crocker

William Henry Crocker I (January 13, 1861 – September 25, 1937) was an American banker, the president of Crocker National Bank and a prominent member of the Republican Party.

Early life

Crocker was born on January 19, 1861 in Sacramento, Califo ...

, Edwin Pauley, and John Francis Neylan

John Francis Neylan (November 6, 1885 - August 19, 1960) was an American lawyer, journalist, political and educational figure.

Biography

Neylan was born in New York City. After graduation from Seton Hall College in New Jersey in 1903, he wen ...

. They were influential men who helped him obtain money for his energetic nuclear particle investigations. There was great hope for medical uses to come from the development of particle physics, and this led to much of the early funding for advances Lawrence was able to obtain.

While at Yale, Lawrence met Mary Kimberly (Molly) Blumer, the eldest of four daughters of George Blumer, the dean of the Yale School of Medicine

The Yale School of Medicine is the graduate medical school at Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was founded in 1810 as the Medical Institution of Yale College and formally opened in 1813.

The primary te ...

. They first met in 1926 and became engaged in 1931, and were married on May 14, 1932, at Trinity Church on the Green

Trinity Church on the Green or Trinity on the Green is a historic, culturally and community-active parish of the Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut in New Haven, Connecticut, of the Episcopal Church. It is one of three historic churches on the Ne ...

in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134 ...

. They had six children: Eric, Margaret, Mary, Robert, Barbara, and Susan. Lawrence named his son Robert after theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experime ...

Robert Oppenheimer, his closest friend in Berkeley. In 1941, Molly's sister Elsie married Edwin McMillan

Edwin Mattison McMillan (September 18, 1907 – September 7, 1991) was an American physicist credited with being the first-ever to produce a transuranium element, neptunium. For this, he shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Glenn Seab ...

, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

in 1951.

Development of the cyclotron

Invention

The invention that brought Lawrence to international fame started out as a sketch on a scrap of a paper napkin. While sitting in the library one evening in 1929, Lawrence glanced over a journal article byRolf Widerøe

Rolf Widerøe (11 July 1902 – 11 October 1996) was a Norwegian accelerator physicist who was the originator of many particle acceleration concepts, including the ''resonance accelerator'' and the betatron accelerator.

Early life

Widerøe w ...

, and was intrigued by one of the diagrams. This depicted a device that produced high-energy particles by means of a succession of small "pushes". The device depicted was laid out in a straight line using increasingly longer electrodes. At the time, physicists were beginning to explore the atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron ...

. In 1919, the New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

had fired alpha particles into nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

and had succeeded in knocking proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

s out of some of the nuclei. But nuclei have a positive charge that repels other positively charged nuclei, and they are bound together tightly by a force that physicists were only just beginning to understand. To break them up, to disintegrate them, would require much higher energies, of the order of millions of volts.

Lawrence saw that such a

Lawrence saw that such a particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined beams.

Large accelerators are used for fundamental research in particle ...

would soon become too long and unwieldy for his university laboratory. In pondering a way to make the accelerator more compact, Lawrence decided to set a circular accelerating chamber between the poles of an electromagnet. The magnetic field would hold the charged protons in a spiral path as they were accelerated between just two semicircular electrodes connected to an alternating potential. After a hundred turns or so, the protons would impact the target as a beam of high-energy particles. Lawrence excitedly told his colleagues that he had discovered a method for obtaining particles of very high energy without the use of any high voltage. He initially worked with Niels Edlefsen. Their first cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Jan ...

was made out of brass, wire, and sealing wax and was only four inches (10 cm) in diameter—it could be held in one hand, and probably cost a total of $25.

What Lawrence needed to develop the idea was capable graduate students to do the work. Edlefsen left to take up an assistant professorship in September 1930, and Lawrence replaced him with David H. Sloan and M. Stanley Livingston

Milton Stanley Livingston (May 25, 1905 – August 25, 1986) was an American accelerator physicist, co-inventor of the cyclotron with Ernest Lawrence, and co-discoverer with Ernest Courant and Hartland Snyder of the strong focusing principle, ...

, whom he set to work on developing Widerøe's accelerator and Edlefsen's cyclotron, respectively. Both had their own financial support. Both designs proved practical, and by May 1931, Sloan's linear accelerator

A linear particle accelerator (often shortened to linac) is a type of particle accelerator that accelerates charged subatomic particles or ions to a high speed by subjecting them to a series of oscillating electric potentials along a linear ...

was able to accelerate ions to 1 MeV. Livingston had a greater technical challenge, but when he applied 1,800 V to his 11-inch cyclotron on January 2, 1931, he got 80,000-electron volt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum ...

protons spinning around. A week later, he had 1.22 MeV with 3,000 V, more than enough for his PhD thesis on its construction.

Development

In what would become a recurring pattern, as soon as there was the first sign of success, Lawrence started planning a new, bigger machine. Lawrence and Livingston drew up a design for a cyclotron in early 1932. The magnet for the $800 11-inch cyclotron weighed 2 tons, but Lawrence found a massive 80-ton magnet rusting in a junkyard in Palo Alto for the 27-inch that had originally been built during World War I to power a transatlantic radio link. In the cyclotron, he had a powerful scientific instrument, but this did not translate into scientific discovery. In April 1932, John Cockcroft andErnest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (6 October 1903 – 25 June 1995) was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate. He is best known for his work with John Cockcroft to construct one of the earliest types of particle accelerator, the Cockcroft–Walton ...

at the Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

in England announced that they had bombarded lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense soli ...

with proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

s and succeeded in transmuting it into helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic ta ...

. The energy required turned out to be quite low—well within the capability of the 11-inch cyclotron. On learning about it, Lawrence sent a wire to Berkeley and asked for Cockcroft and Walton's results to be verified. It took the team until September to do so, mainly due to lack of adequate detection apparatus.

Although important discoveries continued to elude Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory, mainly due to its focus on the development of the cyclotron rather than its scientific use, through his increasingly larger machines, Lawrence was able to provide crucial equipment needed for experiments in high energy physics

Particle physics or high energy physics is the study of Elementary particle, fundamental particles and fundamental interaction, forces that constitute matter and radiation. The fundamental particles in the universe are classified in the Standa ...

. Around this device, he built what became the world's foremost laboratory for the new field of nuclear physics research in the 1930s. He received a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

for the cyclotron in 1934, which he assigned to the Research Corporation

Research Corporation for Science Advancement (RCSA) is an organization in the United States devoted to the advancement of science, funding research projects in the physical sciences. Since 1912, Research Corporation for Science Advancement has id ...

, a private foundation that funded much of Lawrence's early work.

In February 1936, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

's president, James B. Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916. ...

, made attractive offers to Lawrence and Oppenheimer. The University of California's president, Robert Gordon Sproul, responded by improving conditions. The Radiation Laboratory became an official department of the University of California on July 1, 1936, with Lawrence formally appointed its director, with a full-time assistant director, and the University agreed to make $20,000 a year available for its research activities. Lawrence employed a simple business model: "He staffed his laboratory with graduate students and junior faculty of the physics department, with fresh Ph.D.s willing to work for anything, and with fellowship holders and wealthy guests able to serve for nothing."

Reception

Using the new 27-inch cyclotron, the team at Berkeley discovered that every element that they bombarded with recently discovereddeuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being protium, or hydrogen-1). The nucleus of a deuterium atom, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one ...

emitted energy, and in the same range. They, therefore, postulated the existence of a new and hitherto unknown particle that was a possible source of limitless energy. William Laurence

William Leonard Laurence (March 7, 1888 – March 19, 1977) was a Jewish American science journalist best known for his work at ''The New York Times''. Born in the Russian Empire, he won two Pulitzer Prizes. As the official historian of the Man ...

of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' described Lawrence as "a new miracle worker of science". At Cockcroft's invitation, Lawrence attended the 1933 Solvay Conference

The Solvay Conferences (french: Conseils Solvay) have been devoted to outstanding preeminent open problems in both physics and chemistry. They began with the historic invitation-only 1911 Solvay Conference on Physics, considered a turning point i ...

in Belgium. This was a regular gathering of the world's top physicists. Nearly all were from Europe, but occasionally an outstanding American scientist like Robert A. Millikan or Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

would be invited to attend. Lawrence was asked to give a presentation on the cyclotron. Lawrence's claims of limitless energy met a very different reception in Solvay. He ran into withering skepticism from the Cavendish Laboratory's James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

, the physicist who had discovered the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the atomic nucleus, nuclei of atoms. Since protons and ...

in 1932, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1935. In a British accent that sounded condescending to Lawrence's ears, Chadwick suggested that what Lawrence's team was observing was contamination of their apparatus.

When he returned to Berkeley, Lawrence mobilized his team to go painstakingly over the results to gather enough evidence to convince Chadwick. Meanwhile, at the Cavendish laboratory, Rutherford and Mark Oliphant found that deuterium

When he returned to Berkeley, Lawrence mobilized his team to go painstakingly over the results to gather enough evidence to convince Chadwick. Meanwhile, at the Cavendish laboratory, Rutherford and Mark Oliphant found that deuterium fuses

Fuse or FUSE may refer to:

Devices

* Fuse (electrical), a device used in electrical systems to protect against excessive current

** Fuse (automotive), a class of fuses for vehicles

* Fuse (hydraulic), a device used in hydraulic systems to protec ...

to form helium-3

Helium-3 (3He see also helion) is a light, stable isotope of helium with two protons and one neutron (the most common isotope, helium-4, having two protons and two neutrons in contrast). Other than protium (ordinary hydrogen), helium-3 is the ...

, which causes the effect that the cyclotroneers had observed. Not only was Chadwick correct in that they had been observing contamination, but they had overlooked yet another important discovery, that of nuclear fusion. Lawrence's response was to press on with the creation of still larger cyclotrons. The 27-inch cyclotron was superseded by a 37-inch cyclotron in June 1937, which in turn was superseded by a 60-inch cyclotron in May 1939. It was used to bombard iron and produced its first radioactive isotopes in June.

As it was easier to raise money for medical purposes, particularly cancer treatment, than for nuclear physics, Lawrence encouraged the use of the cyclotron for medical research. Working with his brother John and Israel Lyon Chaikoff from the University of California's Physiology Department, Lawrence supported research into the use of radioactive isotopes for therapeutic purposes. Phosphorus-32

Phosphorus-32 (32P) is a radioactive isotope of phosphorus. The nucleus of phosphorus-32 contains 15 protons and 17 neutrons, one more neutron than the most common isotope of phosphorus, phosphorus-31. Phosphorus-32 only exists in small quantiti ...

was easily produced in the cyclotron, and John used it to cure a woman afflicted with polycythemia vera

Polycythemia vera is an uncommon myeloproliferative neoplasm (a type of chronic leukemia) in which the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells. It may also result in the overproduction of white blood cells and platelets.

Most of the healt ...

, a blood disease. John used phosphorus-32 created in the 37-inch cyclotron in 1938 in tests on mice with leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia and pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and result in high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or ...

. He found that the radioactive phosphorus concentrated in the fast-growing cancer cells. This then led to clinical trials on human patients. A 1948 evaluation of the therapy showed that remissions occurred under certain circumstances. Lawrence also had hoped for the medical use of neutrons. The first cancer patient received neutron therapy from the 60-inch cyclotron on November 20. Chaikoff conducted trials on the use of radioactive isotopes as radioactive tracer

A radioactive tracer, radiotracer, or radioactive label is a chemical compound in which one or more atoms have been replaced by a radionuclide so by virtue of its radioactive decay it can be used to explore the mechanism of chemical reactions by ...

s to explore the mechanism of biochemical reactions.

Lawrence was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in November 1939 "for the invention and development of the cyclotron and for results obtained with it, especially with regard to artificial radioactive elements". He was the first at Berkeley as well as the first South Dakotan to become a Nobel Laureate, and the first to be so honored while at a state-supported university. The Nobel award ceremony was held on February 29, 1940, in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and E ...

, due to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, in the auditorium of Wheeler Hall on the campus of the university. Lawrence received his medal from Carl E. Wallerstedt, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

's Consul General

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

. Robert W. Wood wrote to Lawrence and presciently noted "As you are laying the foundations for the cataclysmic explosion of uranium ... I'm sure old Nobel would approve."

In March 1940, Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

, Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

, James B. Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916. ...

, Karl T. Compton

Karl Taylor Compton (September 14, 1887 – June 22, 1954) was a prominent American physicist and president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) from 1930 to 1948.

The early years (1887–1912)

Karl Taylor Compton was born in ...

, and Alfred Lee Loomis

Alfred Lee Loomis (November 4, 1887 – August 11, 1975) was an American attorney, investment banker, philanthropist, scientist, physicist, inventor of the LORAN Long Range Navigation System and a lifelong patron of scientific research. He estab ...

traveled to Berkeley to discuss Lawrence's proposal for a 184-inch cyclotron with a 4,500-ton magnet that was estimated to cost $2.65 million. The Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropy, philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, aft ...

put up $1.15 million to get the project started.

World War II and the Manhattan Project

Radiation Laboratory

After the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in Europe, Lawrence became drawn into military projects. He helped recruit staff for the MIT Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

, where American physicists developed the cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field whi ...

invented by Oliphant's team in Britain. The name of the new laboratory was deliberately copied from Lawrence's laboratory in Berkeley for security reasons. He also became involved in recruiting staff for underwater sound laboratories to develop techniques for detecting German submarines. Meanwhile, work continued at Berkeley with cyclotrons. In December 1940, Glenn T. Seaborg and Emilio Segrè

Emilio Gino Segrè (1 February 1905 – 22 April 1989) was an Italian-American physicist and Nobel laureate, who discovered the elements technetium and astatine, and the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle, for which he was awarded the Nobe ...

used the cyclotron to bombard uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

with deuterons producing a new element, neptunium-238

Neptunium (93Np) is usually considered an artificial element, although trace quantities are found in nature, so a standard atomic weight cannot be given. Like all trace or artificial elements, it has no stable isotopes. The first isotope to be sy ...

, which decayed by beta emission

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For exam ...

to form plutonium-238

Plutonium-238 (238Pu or Pu-238) is a fissile, radioactive isotope of plutonium that has a half-life of 87.7 years.

Plutonium-238 is a very powerful alpha emitter; as alpha particles are easily blocked, this makes the plutonium-238 isotope suit ...

. One of its isotopes, plutonium-239

Plutonium-239 (239Pu or Pu-239) is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three mai ...

, could undergo nuclear fission which provided another way to make an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

.

Lawrence offered Segrè a job as a research assistant—a relatively lowly position for someone who had discovered an element—for US$300 a month for six months. However, when Lawrence learned that Segrè was legally trapped in California, he reduced Segrè's salary further to US$116 a month. When the regents of the University of California wanted to terminate Segrè's employment owing to his foreign nationality, Lawrence managed to retain Segrè by hiring him as a part-time lecturer paid by the Rockefeller Foundation. Similar arrangements were made to retain his doctoral students Chien-Shiung Wu

)

, spouse =

, residence =

, nationality = ChineseAmerican

, field = Physics

, work_institutions = Institute of Physics, Academia Sinica University of California at Berkeley Smith College Princeton University Columbia UniversityZhejiang ...

(a Chinese national) and Kenneth Ross MacKenzie (a Canadian national) when they graduated.

In September 1941, Oliphant met with Lawrence and Oppenheimer at Berkeley, where they showed him the site for the new cyclotron. Oliphant, in turn, took the Americans to task for not following up the recommendations of the British

In September 1941, Oliphant met with Lawrence and Oppenheimer at Berkeley, where they showed him the site for the new cyclotron. Oliphant, in turn, took the Americans to task for not following up the recommendations of the British MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram fro ...

, which advocated a program to develop an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. Lawrence had already thought about the problem of separating the fissile isotope uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

from uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

, a process known today as uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

. Separating uranium isotopes was difficult because the two isotopes have very nearly identical chemical properties, and could only be separated gradually using their small mass differences. Separating isotopes with a mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

was a technique Oliphant had pioneered with lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense soli ...

in 1934.

Lawrence began converting his old 37-inch cyclotron into a giant mass spectrometer. On his recommendation, the director of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

Leslie R. Groves, Jr.

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

, appointed Oppenheimer as head of its Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

. While the Radiation laboratory developed the electromagnetic uranium enrichment process, the Los Alamos Laboratory designed and constructed the atomic bombs. Like the Radiation Laboratory, it was run by the University of California.

Electromagnetic isotope separation used devices known as calutron

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was deri ...

s, a hybrid of two laboratory instruments, the mass spectrometer and cyclotron. The name was derived from "California university cyclotrons". In November 1943, Lawrence's team at Berkeley was bolstered by 29 British scientists, including Oliphant.

In the electromagnetic process, a magnetic field deflected charged particles according to mass. The process was neither scientifically elegant nor industrially efficient. Compared with a gaseous diffusion plant or a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

, an electromagnetic separation plant would consume more scarce materials, require more manpower to operate, and cost more to build. Nonetheless, the process was approved because it was based on proven technology and therefore represented less risk. Moreover, it could be built in stages, and would rapidly reach industrial capacity.

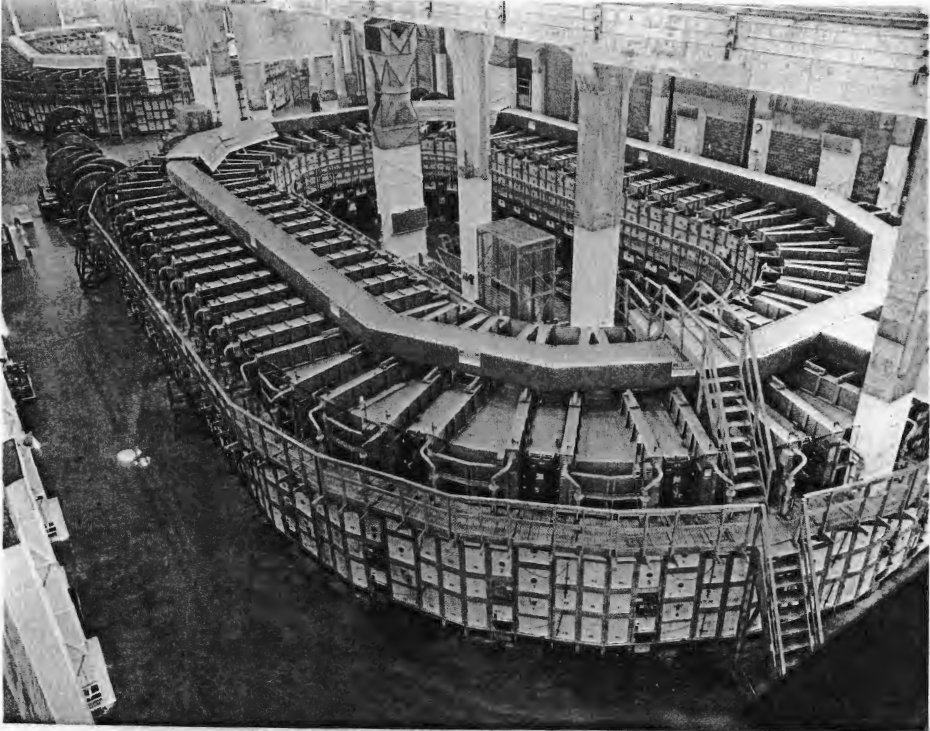

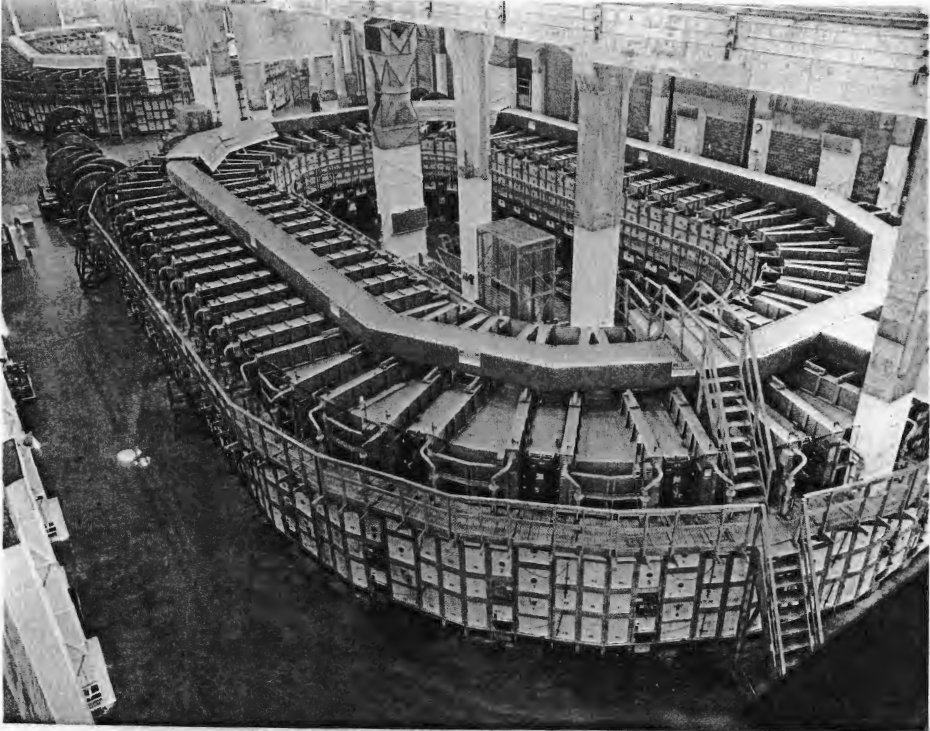

Oak Ridge

Responsibility for the design and construction of the electromagnetic separation plant atOak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's popu ...

, which came to be called Y-12, was assigned to Stone & Webster

Stone & Webster was an American engineering services company based in Stoughton, Massachusetts. It was founded as an electrical testing lab and consulting firm by electrical engineers Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster in 1889. In the earl ...

. The calutrons, using 14,700 tons of silver, were manufactured by Allis-Chalmers

Allis-Chalmers was a U.S. manufacturer of machinery for various industries. Its business lines included agricultural equipment, construction equipment, power generation and power transmission equipment, and machinery for use in industrial s ...

in Milwaukee and shipped to Oak Ridge. The design called for five first-stage processing units, known as Alpha racetracks, and two units for final processing, known as Beta racetracks. In September 1943 Groves authorized construction of four more racetracks, known as Alpha II. When the plant was started up for testing on schedule in October 1943, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely. A more serious problem arose when the magnetic coils started shorting out. In December Groves ordered a magnet to be broken open, and handfuls of rust were found inside. Groves then ordered the racetracks to be torn down and the magnets sent back to the factory to be cleaned. A pickling plant was established on-site to clean the pipes and fittings.

Tennessee Eastman

Eastman Chemical Company is an American company primarily involved in the chemical industry. Once a subsidiary of Kodak, today it is an independent global specialty materials company that produces a broad range of advanced materials, chemicals and ...

was hired to manage Y-12. Y-12 initially enriched the uranium-235 content to between 13% and 15%, and shipped the first few hundred grams of this to Los Alamos laboratory in March 1944. Only 1 part in 5,825 of the uranium feed emerged as final product. The rest was splattered over equipment in the process. Strenuous recovery efforts helped raise production to 10% of the uranium-235 feed by January 1945. In February the Alpha racetracks began receiving slightly enriched (1.4%) feed from the new S-50 thermal diffusion plant. The next month it received enhanced (5%) feed from the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant. By April 1945 K-25 was producing uranium sufficiently enriched to feed directly into the Beta tracks.

On July 16, 1945, Lawrence observed the Trinity nuclear test of the first atomic bomb with Chadwick and Charles A. Thomas. Few were more excited at its success than Lawrence. The question of how to use the now functional weapon on Japan became an issue for the scientists. While Oppenheimer favored no demonstration of the power of the new weapon to Japanese leaders, Lawrence felt strongly that a demonstration would be wise. When a uranium bomb was used without warning in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, Lawrence felt great pride in his accomplishment.

Lawrence hoped that the Manhattan Project would develop improved calutrons and construct Alpha III racetracks, but they were judged to be uneconomical. The Alpha tracks were closed down in September 1945. Although performing better than ever, they could not compete with K-25 and the new K-27, which commenced operation in January 1946. In December, the Y-12 plant was closed, thereby cutting the Tennessee Eastman payroll from 8,600 to 1,500 and saving $2 million a month. Staff numbers at the Radiation laboratory fell from 1,086 in May 1945 to 424 by the end of the year.

Post-war career

Big Science

After the war, Lawrence campaigned extensively for government sponsorship of large scientific programs. He was a forceful advocate of Big Science with its requirements for big machines and big money, and in 1946 he asked the Manhattan Project for over $2 million for research at the Radiation Laboratory. Groves approved the money, but cut a number of programs, including Seaborg's proposal for a "hot" radiation laboratory in densely populated Berkeley, and John Lawrence's for production of medical isotopes, because this need could now be better met from nuclear reactors. One obstacle was the University of California, which was eager to divest its wartime military obligations. Lawrence and Groves managed to persuade Sproul to accept a contract extension. In 1946, the Manhattan Project spent $7 on physics at the University of California for every dollar spent by the University. The 184-inch cyclotron was completed with wartime dollars from the Manhattan Project. It incorporated new ideas by Ed McMillan, and was completed as asynchrocyclotron

A synchrocyclotron is a special type of cyclotron, patented by Edwin McMillan in 1952, in which the frequency of the driving RF electric field is varied to compensate for relativistic effects as the particles' velocity begins to approach the s ...

. It commenced operation on November 13, 1946. For the first time since 1935, Lawrence actively participated in the experiments, working with Eugene Gardner

Milton Eugene Gardner (February 10, 1901 – 1986) was an American physicist who worked on radar systems at the Radiation Laboratory in Massachusetts.

Early life

He was born in Santa Cruz, California, but would have been born in China if his f ...

in an unsuccessful attempt to create recently discovered pi meson

In particle physics, a pion (or a pi meson, denoted with the Greek letter pi: ) is any of three subatomic particles: , , and . Each pion consists of a quark and an antiquark and is therefore a meson. Pions are the lightest mesons and, more ge ...

s with the synchrotron. César Lattes then used the apparatus they had created to find negative pi mesons in 1948.

Responsibility for the national laboratories passed to the newly created Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) on January 1, 1947. That year, Lawrence asked for $15 million for his projects, which included a new linear accelerator and a new gigaelectronvolt synchrotron which became known as the bevatron

The Bevatron was a particle accelerator — specifically, a weak-focusing proton synchrotron — at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, U.S., which began operating in 1954. The antiproton was discovered there in 1955, resulting in ...

. The University of California's contract to run the Los Alamos laboratory was due to expire on July 1, 1948, and some board members wished to divest the university of the responsibility for running a site outside California. After some negotiation, the university agreed to extend the contract for what was now the Los Alamos National Laboratory for four more years and to appoint Norris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbur ...

, who had replaced Oppenheimer as its director in October 1945, as a professor. Soon after, Lawrence received all the funds he had requested.

Notwithstanding the fact that he voted for

Notwithstanding the fact that he voted for Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, Lawrence was a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, who had strongly disapproved of Oppenheimer's efforts before the war to unionize the Radiation Laboratory workers, which Lawrence considered "leftwandering activities". Lawrence considered political activity to be a waste of time better spent in scientific research, and preferred that it be kept out of the Radiation Laboratory.

In the chilly Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

climate of the post-war University of California, Lawrence accepted the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, create ...

's actions as legitimate, and did not see them as indicative of a systemic problem involving academic freedom

Academic freedom is a moral and legal concept expressing the conviction that the freedom of inquiry by faculty members is essential to the mission of the academy as well as the principles of academia, and that scholars should have freedom to teach ...

or human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

. He was protective of individuals in his laboratory, but even more protective of the reputation of the laboratory. He was forced to defend Radiation Laboratory staff members like Robert Serber

Robert Serber (March 14, 1909 – June 1, 1997) was an American physicist who participated in the Manhattan Project. Serber's lectures explaining the basic principles and goals of the project were printed and supplied to all incoming scientific st ...

who were investigated by the University's Personnel Security Board. In several cases, he issued character references in support of staff. However, Lawrence barred Robert Oppenheimer's brother Frank from the Radiation Laboratory, damaging his relationship with Robert. An acrimonious loyalty oath campaign at the University of California also drove away faculty members. When hearings were held to revoke Robert Oppenheimer's security clearance, Lawrence declined to attend on account of illness, but a transcript in which he was critical of Oppenheimer was presented in his absence. Lawrence's success in building a creative, collaborative laboratory was undermined by the ill-feeling and distrust resulting from political tensions.

Thermonuclear weapons

Lawrence was alarmed by theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's first nuclear test in August 1949. The proper response, he concluded, was an all-out effort to build a bigger nuclear weapon: the hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

. He proposed to use accelerators instead of nuclear reactors to produce the neutrons needed to create the tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of ...

the bomb required, as well as plutonium, which was more difficult, as much higher energies would be required. He first proposed the construction of Mark I, a prototype $7 million, 25 MeV linear accelerator

A linear particle accelerator (often shortened to linac) is a type of particle accelerator that accelerates charged subatomic particles or ions to a high speed by subjecting them to a series of oscillating electric potentials along a linear ...

, codenamed Materials Test Accelerator (MTA). He was soon talking about a new, even larger MTA known as the Mark II, which could produce tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of ...

or plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exh ...

from depleted uranium-238. Serber and Segrè attempted in vain to explain the technical problems that made it impractical, but Lawrence felt that they were being unpatriotic.

Lawrence strongly backed Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

's campaign for a second nuclear weapons laboratory, which Lawrence proposed to locate with the MTA Mark I at Livermore, California

Livermore (formerly Livermorès, Livermore Ranch, and Nottingham) is a city in Alameda County, California. With a 2020 population of 87,955, Livermore is the most populous city in the Tri-Valley. It is located on the eastern edge of Californi ...

. Lawrence and Teller had to argue their case not only with the Atomic Energy Commission, which did not want it, and the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which was implacably opposed but with proponents who felt that Chicago was the more obvious site for it. The new laboratory at Livermore was finally approved on July 17, 1952, but the Mark II MTA was canceled. By this time, the Atomic Energy Commission had spent $45 million on the Mark I, which had commenced operation, but was mainly used to produce polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. Polonium is a chalcogen. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character ...

for the nuclear weapons program. Meanwhile, the Brookhaven National Laboratory

Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory located in Upton, Long Island, and was formally established in 1947 at the site of Camp Upton, a former U.S. Army base and Japanese internment c ...

's Cosmotron

The Cosmotron was a particle accelerator, specifically a proton synchrotron, at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Its construction was approved by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in 1948, reaching its full energy in 1953, and continuing to ru ...

had generated a 1 GeV beam.

Death and legacy

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Lawrence received theElliott Cresson Medal

The Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, was the highest award given by the Franklin Institute. The award was established by Elliott Cresson, life member of the Franklin Institute, with $1,000 granted in 1848. The ...

and the Hughes Medal

The Hughes Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of London "in recognition of an original discovery in the physical sciences, particularly electricity and magnetism or their applications". Named after David E. Hughes, the medal is awarded wit ...

in 1937, the Comstock Prize in Physics

The Comstock Prize in Physics is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "for recent innovative discovery or investigation in electricity, magnetism, or radiant energy, broadly interpreted."

Honorees must be residents of North America ...

in 1938, the Duddell Medal and Prize

The Dennis Gabor Medal and Prize (previously the Duddell Medal and Prize until 2008) is a prize awarded biannually by the Institute of Physics for distinguished contributions to the application of physics in an industrial, commercial or busines ...

in 1940, the Holley Medal The Holley Medal is an award of ASME (the American Society of Mechanical Engineers) for "outstanding and unique act(s) of an engineering nature, accomplishing a noteworthy and timely public benefit by one or more individuals for a single achievemen ...

in 1942, the Medal for Merit in 1946, the William Procter Prize in 1951, Faraday Medal

The Faraday Medal is a top international medal awarded by the UK Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) (previously called the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE)). It is part of the IET Achievement Medals collection of awards. ...

in 1952, and the Enrico Fermi Award from the Atomic Energy Commission in 1957. He was made an Officer of the Legion d'Honneur in 1948, and was the first recipient of the Sylvanus Thayer Award The Sylvanus Thayer Award is an honor given annually by the United States Military Academy at West Point to an individual whose character and accomplishments exemplifies the motto of West Point. The award is named after the 'Father of the Military ...

by the US Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1958.

In July 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked Lawrence to travel to Geneva, Switzerland

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, to help negotiate a proposed Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. AEC Chairman Lewis Strauss had pressed for Lawrence's inclusion. The two men had argued the case for the development of the hydrogen bomb, and Strauss had helped raise funds for Lawrence's cyclotron in 1939. Strauss was keen to have Lawrence as part of the Geneva delegation because Lawrence was known to favor continued nuclear testing. Despite suffering from a serious flare-up of his chronic ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum. The primary symptoms of active disease are abdominal pain and diarrhea mixed with blood (hematochezia). Weight loss, fever, and ...

, Lawrence decided to go, but he became ill while in Geneva, and was rushed back to the hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergen ...

at Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

. Surgeons removed much of his large intestine, but found other problems, including severe atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a pattern of the disease arteriosclerosis in which the wall of the artery develops abnormalities, called lesions. These lesions may lead to narrowing due to the buildup of atheromatous plaque. At onset there are usually no s ...

in one of his arteries. He died in Palo Alto Hospital on August 27, 1958, nineteen days after his 57th birthday. Molly did not want a public funeral but agreed to a memorial service at the First Congregationalist Church in Berkeley. University of California President Clark Kerr

Clark Kerr (May 17, 1911 – December 1, 2003) was an American professor of economics and academic administrator. He was the first chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley, and twelfth president of the University of California.

Bi ...

delivered the eulogy

A eulogy (from , ''eulogia'', Classical Greek, ''eu'' for "well" or "true", ''logia'' for "words" or "text", together for "praise") is a speech or writing in praise of a person or persons, especially one who recently died or retired, or as ...

.

Just 23 days after his death, the Regents of the University of California

The Regents of the University of California (also referred to as the Board of Regents to distinguish the board from the corporation it governs of the same name) is the governing board of the University of California (UC), a state university sy ...

voted to rename two of the university's nuclear research sites after Lawrence: the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

. The Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award

The Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award was established in 1959 in honor of a scientist who helped elevate American physics to the status of world leader in the field.

E. O. Lawrence was the inventor of the cyclotron, an accelerator of subatomic part ...

was established in his memory in 1959. Chemical element number 103, discovered at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 1961, was named lawrencium