Ernest Joyce on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Edward Mills Joyce AM ( – 2 May 1940) was a Royal Naval seaman and explorer who participated in four

Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

expeditions during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often ci ...

, in the early 20th century. He served under both Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

and Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

. As a member of the Ross Sea party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the pola ...

in Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

, Joyce earned an Albert Medal for his actions in bringing the stricken party to safety, after a traumatic journey on the Great Ice Barrier

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between hi ...

. He was awarded the Polar Medal

The Polar Medal is a medal awarded by the Sovereign of the United Kingdom to individuals who have outstanding achievements in the field of polar research, and particularly for those who have worked over extended periods in harsh climates. It ...

with four bars, one of only two men to be so honoured, the other being his contemporary, Frank Wild

John Robert Francis Wild (18 April 1873 – 19 August 1939), known as Frank Wild, was an English sailor and explorer. He participated in five expeditions to Antarctica during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, for which he was awar ...

.

Joyce came from a humble seafaring background and began his naval career as a boy seaman in 1891. His Antarctic experiences began 10 years later, when he joined Scott's Discovery Expedition

The ''Discovery'' Expedition of 1901–1904, known officially as the British National Antarctic Expedition, was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic regions since the voyage of James Clark Ross sixty years earlier (1839–18 ...

as an Able Seaman. In 1907 Shackleton recruited Joyce to take charge of dogs and sledges

A sled, skid, sledge, or sleigh is a land vehicle that slides across a surface, usually of ice or snow. It is built with either a smooth underside or a separate body supported by two or more smooth, relatively narrow, longitudinal runners s ...

on the Nimrod Expedition

The ''Nimrod'' Expedition of 1907–1909, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, was the first of three successful expeditions to the Antarctic led by Ernest Shackleton and his second expedition to the Antarctic. Its main target, ...

. Subsequently, Joyce was engaged in a similar capacity for Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson OBE FRS FAA (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Sir Ernest Shackleton, he was a key expedition leader duri ...

's Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a 1911–1914 expedition headed by Douglas Mawson that explored the largely uncharted Antarctic coast due south of Australia. Mawson had been inspired to lead his own venture by his experiences on Ernest ...

in 1911, but left the expedition before it departed for the Antarctic. In 1914 Shackleton recruited Joyce for the Ross Sea party; despite his heroics this expedition marked the end of Joyce's association with the Antarctic, and of his exploring career, although he made repeated attempts to join other expeditions.

Throughout his career Joyce was known as an abrasive personality who attracted adverse as well as positive comments. His effectiveness in the field was widely acknowledged by many of his colleagues, but other aspects of his character were less appreciated – his capacity for bearing grudges, his boastfulness and his distortions of the truth. Joyce's diaries, and the book he wrote based on them, have been condemned as self-serving and the work of a fabulist. He made no significant material gains from his expeditions, living out his post-Antarctic life in humble circumstances before dying in 1940.

Early years

Joyce's Naval Service Record show his place and date of birth at Felpham, Sussex, 22 December 1875. Kelly Tyler-Lewis, in her account of theRoss Sea party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the pola ...

, quotes a newspaper report giving Joyce's age as 64 in 1939, indicating birth year as 1875 – although she also gives his age as 29 in 1901, suggesting an earlier birth year. Joyce's father and grandfather had both been sailors, his father probably within the coastguard service. After the father's early death his widow, with three children to support on her limited earnings as a seamstress, sent the young Ernest to the Lower School of Greenwich Royal Hospital School for Navy Orphans at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

. Here, in austere surroundings, he received a vocational education that would prepare him for a lower-deck career in the Royal Navy. After leaving the school in 1891, he joined the navy as a boy seaman, progressing over the next ten years to Ordinary Seaman

__NOTOC__

An ordinary seaman (OS) is a member of the deck department of a ship. The position is an apprenticeship to become an able seaman, and has been for centuries. In modern times, an OS is required to work on a ship for a specific amount ...

and then Able Seaman

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination o ...

.Tyler-Lewis, p. 55–57 Joyce had blue eyes and a fair complexion, with a tattoo on his left forearm and a scar on his right cheek. He was not a tall man, only 5' 7" in height.McOrist, p. 11

British Naval Archive Records at Portsmouth – No: 160823 – provide full details on Joyce's early naval service. This commenced in May 1891 as a Boy Second Class on the St. Vincent, and over the following ten years he served on a number of ships; the Boscawen, Alexandra, Victory 1, Duke of Wellington, etc. In 1891 he was serving on in Cape Town where, in September, Scott's expedition ship stopped on the way to the Antarctic. Scott was short-handed, and requested volunteers; from a response of several hundreds, Joyce was one of four seamen chosen to join ''Discovery''. He sailed south with her on 14 October 1901.

Discovery Expedition, 1901–1904

The ''Discovery'' Expedition was Joyce's Antarctic baptism, although for the next three years he kept a relatively low profile; Scott scarcely mentions him in ''The Voyage of the Discovery'', andEdward Wilson Edward Wilson may refer to:

*Ed Wilson (artist) (1925–1996), African American sculptor

* Ed Wilson (baseball) (1875–?), American baseball player

* Ed Wilson (singer) (1945–2010), Brazilian singer-songwriter

* Ed Wilson, American television ex ...

's diaries not at all. It seems that he took readily to Antarctic life, gaining experience in sledging and dog-driving techniques and other aspects of Antarctic exploration. He did not figure in the main journeys of the expedition, although towards the end he joined Arthur Pilbeam and Frank Wild

John Robert Francis Wild (18 April 1873 – 19 August 1939), known as Frank Wild, was an English sailor and explorer. He participated in five expeditions to Antarctica during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, for which he was awar ...

in an attempt to climb Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a sum ...

, ascending to some . Joyce was at times badly affected by frostbite

Frostbite is a skin injury that occurs when exposed to extreme low temperatures, causing the freezing of the skin or other tissues, commonly affecting the fingers, toes, nose, ears, cheeks and chin areas. Most often, frostbite occurs in t ...

; on one occasion two officers, Michael Barne

Michael Barne (15 October 1877 – 31 May 1961) was an officer of the 1901-04 Discovery Expedition and was the last survivor of the expedition.

Early life

Barne was born at Sotterley Park, Suffolk, the son of Frederick Barne and his wife, La ...

and George Mulock

Captain George Francis Arthur Mulock, DSO, RN, FRGS (7 February 1882 – 26 December 1963) was an Anglo-Irish Royal Navy officer, cartographer and polar explorer who participated in an expedition to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedi ...

, held Joyce's frostbitten foot against the pits of their stomachs and kneaded the ankle for several hours to save it from amputation. However, such experiences left Joyce undaunted; the polar historian Beau Riffenburgh

Beau Riffenburgh (born 1955) is an author and historian specializing in polar exploration. He is also an American football coach and author of books on football history.

Early career

A native of California, Riffenburgh was the Senior Writer and ...

writes that Joyce was repeatedly drawn to the Antarctic by "a curious combination of affection and antipathy" that "impelled imto return again and again".Riffenburgh, p. 126

During the expedition Joyce encountered several men who would feature prominently in Antarctic polar history during the following years, including Scott, Wilson, Frank Wild, Tom Crean Tom or Thomas Crean may refer to:

*Thomas Crean (1873–1923), Irish rugby union player, British Army soldier and doctor

*Tom Crean (explorer) (1877–1938), Irish seaman and Antarctic explorer

*Tom Crean (basketball)

Thomas Aaron Crean (born Ma ...

, William Lashly, Edgar Evans

Petty Officer Edgar Evans (7 March 1876 – 17 February 1912) was a Royal Navy officer and member of the "Polar Party" in Robert Falcon Scott's ill-fated ''Terra Nova'' Expedition to the South Pole in 1911–1912. This group of five me ...

and, most significantly, Ernest Shackleton. Joyce made several sledging trips with ShackletonRiffenburgh, p. 125 and created an impression of competence and reliability. He also impressed Scott as "sober, honest, loyal and intelligent", and expedition organiser Sir Clements Markham later described him as "an honest and trustworthy man". His reward, at the conclusion of the expedition, was promotion to Petty Officer 1st Class

Petty officer first class (PO1) is a rank found in some navies and maritime organizations.

Canada

Petty officer, 1st class, PO1, is a Naval non-commissioned member rank of the Canadian Forces. It is senior to the rank of petty officer 2nd-clas ...

on Scott's recommendation. However, he had been bitten by the bug of Antarctic exploration, and ordinary naval duty no longer appealed. He left the navy in 1905 but found shore life unsatisfying and re-enlisted in 1906. When the chance came a year later to join Shackleton's ''Nimrod'' Expedition, he took it immediately.

British Antarctic Expedition (''Nimrod'') 1907–1909

When Shackleton was selecting the crew for his Antarctic expedition in ''Nimrod'', Joyce was one of his earliest recruits. Most accounts tell the story that Shackleton saw Joyce on a bus that was passing his expedition offices, sent someone out to fetch him, and recruited him on the spot.Huntford, p. 194 To join the expedition, Joyce bought his release from the Navy; in later years he would claim that Shackleton had failed to recompense him for this, despite a promise to do so, one of several disputes over money and recognition which would strain his relations with Shackleton.Riffenburgh, p. 126 Joyce, Shackleton and Frank Wild were the only members of the expedition with previous Antarctic experience, and on the basis of his ''Discovery'' exploits, Joyce was put in charge of the new expedition's general stores, sledges and dogs. Before departure in August 1907, he and Wild took a crash course in printing at Sir Joseph Causton's printing firm in Hampshire, as Shackleton intended to publish a book or magazine while in the Antarctic. ''Nimrod'' left New Zealand on 1 January 1908, and as a fuel-saving measure was towed towards the Antarctic pack ice by the tug ''Koonya''. On 23 January, by now under her own power, she reached theRoss Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between h ...

(then known as the "Great Ice Barrier", or "Barrier"), where Shackleton planned to base his headquarters in an inlet discovered during the ''Discovery'' voyage. This proved impossible; the inlet, where Scott and Shackleton had taken balloon flights in February 1902, had greatly expanded to become an open bay, christened the "Bay of Whales". Shackleton was convinced that the ice was not secure enough as a landing ground, and could find no feasible alternative site on nearby King Edward VII Land

King Edward VII Land or King Edward VII Peninsula is a large, ice-covered peninsula which forms the northwestern extremity of Marie Byrd Land in Antarctica. The peninsula projects into the Ross Sea between Sulzberger Bay and the northeast corne ...

. Before leaving for the Antarctic Shackleton had promised Scott that he would not base his expedition in or near Scott's former headquarters in McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica. It is the southernmost navigable body of water in the world, and is about from the South Pole.

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound in February 1841, and named it after Lt. Archibald McMurdo ...

. Shackleton was now forced to break this agreement, and take ''Nimrod'' to the safer waters of McMurdo Sound. The site finally chosen as a base was at Cape Royds

Cape Royds is a dark rock cape forming the western extremity of Ross Island, facing on McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. It was discovered by the Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) and named for Lieutenant Charles Royds, Royal Navy, who acted as meteor ...

, some north of Scott's old ''Discovery'' headquarters at Hut Point. During the extended and often difficult process of unloading the ship Joyce remained ashore, looking after the dogs and ponies, and helping to build the expedition hut. Joyce was witness to an incident during unloading, where a crate hook attached to a barrel swung across and struck one of the watching officers – Aeneas Mackintosh

Aeneas Lionel Acton Mackintosh (1 July 1879 – 8 May 1916) was a British Merchant Navy officer and Antarctic explorer, who commanded the Ross Sea party as part of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917. ...

– on the face. (Mackintosh's right eye was virtually destroyed and later that day the expedition doctor operated to remove the eye.) In March Joyce assisted the party that made the first successful ascent of Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a sum ...

, although he did not make the climb himself.

During the following winter Joyce, with Wild's help, printed copies of the expedition book ''Aurora Australis

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

'', edited by Shackleton. About 25 or 30 copies of the book were printed, sewn and bound. Otherwise Joyce was busy preparing equipment and stores for the next season's journey to the Pole in which, in view of his experience, he fully expected to be included. However, various mishaps had reduced the number of ponies to four, so Shackleton cut the southern party to that number. One of those dropped was Joyce, on advice from expedition doctor Eric Marshall

Lieutenant Colonel Eric Marshall (29 May 1879 – 26 February 1963) was a British Army doctor and Antarctic explorer with the Nimrod Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton in 1907–09, and was one of the party of four men (Marshall, Shackleton, ...

, who noted that Joyce had a liver problem and the early stages of heart disease. Frank Wild, who along with Marshall and Jameson Adams was selected for the southern journey, wrote in his diary after the party's bid to reach the Pole had fallen short: "If we only had Joyce and Marston here instead of these two useless grub-scoffing beggars"—Marshall and Adams—"we would have done it easily." Joyce showed no particular resentment at his exclusion; he assisted the preparatory work and accompanied the polar party on the southward march for the first seven days. In the following months he took charge of enhancing the depots, to ensure adequate supplies for the returning southern party. He deposited a special cache of luxuries at Minna Bluff, together with life-saving food and fuel, earning Wild's spontaneous praise when the cache was discovered.

Shackleton and his party returned safely from their polar journey, on ''Nimrod's'' last feasible date for sailing home. They had established a new Farthest South

Farthest South refers to the most southerly latitude reached by explorers before the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captai ...

at 88°23′S, only from the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

. Joyce had been ready to remain at the base with a rearguard, to wait for the party or to establish its fate if it did not return in time to catch the ship. ''Nimrod'' finally reached London in September 1909 and was prepared, under Joyce's direction, as a floating exhibition of polar artefacts. Shackleton paid him a salary of £250 a year, , a generous amount for the time.

Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911

Joyce was not invited to join Scott'sTerra Nova Expedition

The ''Terra Nova'' Expedition, officially the British Antarctic Expedition, was an expedition to Antarctica which took place between 1910 and 1913. Led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott, the expedition had various scientific and geographical objec ...

, although several of Shackleton's men were, including Frank Wild who declined. Instead, Joyce and Wild both signed up for Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson OBE FRS FAA (5 May 1882 – 14 October 1958) was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer, and academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Sir Ernest Shackleton, he was a key expedition leader duri ...

's Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a 1911–1914 expedition headed by Douglas Mawson that explored the largely uncharted Antarctic coast due south of Australia. Mawson had been inspired to lead his own venture by his experiences on Ernest ...

. In 1911 Joyce travelled to Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

to acquire dogs for this expedition, and took them on to Tasmania. Joyce did not subsequently sail with Mawson. According to one account he was "dismissed" before the expedition left Australia, while another suggests that Joyce was dropped when Mawson reduced his expedition from three shore parties to two.Mills, pp. 127–128 Whatever the reason, it appears that there was a falling-out; Mawson reportedly distrusted Joyce, saying that "he spent too much time in hotels", which suggests that drink was an issue.Mills, p. 128 Joyce remained in Australia, obtaining work with the Sydney Harbour Trust.Tyler-Lewis, p. 57

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917

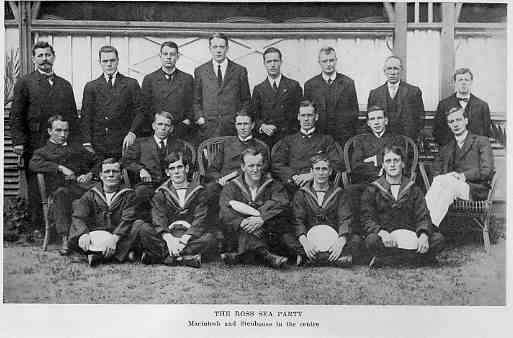

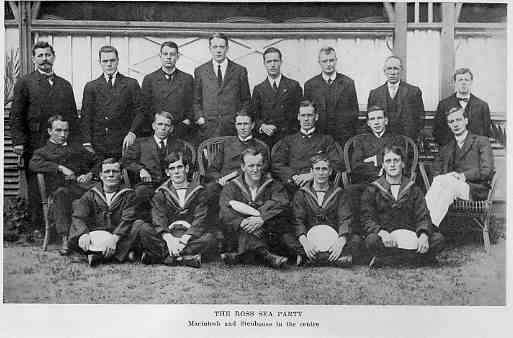

Membership of Ross Sea party

In February 1914 Joyce, still in Australia, was contacted by Shackleton. who outlined plans for hisImperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

. Shackleton wanted Joyce in the expedition's supporting Ross Sea party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the pola ...

; should the plans change to a one-ship format, Shackleton promised to find a different role for Joyce within the expedition. Joyce would later claim without justification that Shackleton had offered him a place on the main transcontinental party.Tyler-Lewis, p. 260 In his subsequent book, ''The South Polar Trail'' published in 1929, Joyce also misrepresented the nature of his appointment to the Ross Sea party, omitting Shackleton's order that placed him under an officer and claiming that he had been given sole authority over dogs and sledging.

The task of the Ross Sea party, under the command of another ''Nimrod'' veteran, Aeneas Mackintosh

Aeneas Lionel Acton Mackintosh (1 July 1879 – 8 May 1916) was a British Merchant Navy officer and Antarctic explorer, who commanded the Ross Sea party as part of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917. ...

, was to establish a base in McMurdo Sound and then lay a series of supply depots across the Ross Ice Shelf to assist the transcontinental party. Shackleton saw this task as routine; he wrote: "I had not anticipated that the work would present any great difficulties". However, the party had been assembled rather hurriedly, and was inexperienced. Only Joyce and Mackintosh had been to the Antarctic before, and Mackintosh's participation in polar work had been brief; he had been invalided from the Nimrod Expedition before the initial landing, after an accident led to the loss of his right eye and had returned only for the final stages of the expedition

Major setbacks

''Aurora''s departure from Australia was delayed by a series of organisational and financial setbacks, and the party did not arrive in McMurdo Sound until 16 January 1915—very late in the season for depot-laying work. Mackintosh, who believed that Shackleton might attempt to cross the continent in that first season, insisted that sledging work should begin without delay, with a view to laying down supply depots at 79° and 80°S. Joyce opposed this; more time, he maintained, should be set aside to acclimatise and train men and dogs. However he was over-ruled by Mackintosh, who was unaware that Shackleton had ruled out a crossing that season. Joyce's diary notes of 24 January detail his frustrations:After breakfast Skipper + I discussed several details. I could not get him to see that we were jeopardizing the dogs + I cannot quite understand why Shacks should alter his plan of campaign. As for wintering the ship – this to my mind is the silliest damn rot that could have possibly occurred. The wintering of the Discovery was quite alright in its way, but then we had no experience of Antarctic conditions. If I had Shacks here I would make him see my way of arguing.Mackintosh further vexed Joyce by deciding to lead this depot-laying party himself, unmoved by Joyce's claim to have independent authority over this area. The party was divided into two teams, and the journey began on 24 January, in an atmosphere of muddle. Initial attempts at travelling on the Barrier were thwarted by the condition of the surface, and Mackintosh's team got lost on the sea ice between Cape Evans and Hut Point. Joyce privately gloated over this evidence of the captain's inexperience.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 69–74 The teams eventually reached the 79° mark, and laid the "Bluff depot" there (

Anyway Mack is my Boss + I must uphold him until I find that he is not fit to carry out the hard tedious work that is in front of us. Having one eye will play merry hell with him in the extreme temperatures. As he will not take my advice about the dogs I must let him have his way.

Minna Bluff Minna Bluff is a rocky promontory at the eastern end of a volcanic Antarctic peninsula projecting deep into the Ross Ice Shelf at . It forms a long, narrow arm which culminates in a south-pointing hook feature (Minna Hook), and is the subject of re ...

was a prominent visible landmark at this latitude) on 9 February. It seemed that Joyce's party had enjoyed the easier journey.Tyler-Lewis, p. 83–92 Mackintosh's plan to take the dogs on to the 80° mark led to more words between him and Joyce,Tyler-Lewis, p. 83 who argued that several dogs had already died and that the remainder needed to be kept for future journeys, but again he was over-ruled. On 20 February the party reached the 80° latitude and laid their depot there.Tyler-Lewis, p. 92 The outcome of this journey was of provisions and fuel at 80°S and at 79°S. But a further , intended for the depots, had been dumped on the journey, to save weight.

By this time men and dogs were worn out. On the return journey, in appalling Barrier weather, all the dogs perished, as Joyce had predicted, and the party returned to Hut Point on 24 March exhausted and severely frostbitten. After being delayed for ten weeks at Hut Point by the condition of the sea ice, the party finally got back to their base at Cape Evans on 2 June. They then learned that ''Aurora'', with most of the shore party's stores and equipment still aboard, had been torn from its moorings in a gale, and blown far out to sea with no prospect of swift return. Fortunately, the rations for the next season's depot-laying had been landed before the ship's involuntary departure.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 128–131 However, the shore party's own food, fuel, clothing and equipment had been largely carried away; replacements would have to be improvised from supplies left at Cape Evans after Scott's 1910–13 Terra Nova expedition, augmented by seal meat and blubber. In these circumstances Joyce proved his worth as a "master scavenger" and improviser, unearthing from Scott's abandoned stores, among other treasures, a large canvas tent from which he fashioned roughly tailored clothing. He also set about stitching 500 calico bags, to hold the depot rations.

Depot-laying journey

The party set out on 1 September 1915. The men were under-trained and half-fit, in primitive clothing and with home-made equipment.Tyler-Lewis, p. 148 With only five dogs remaining from the previous season's debacle, the task would mostly be one ofmanhauling

Manhauling or man-hauling is the pulling forward of sledges, trucks or other load-carrying vehicles by human power unaided by animals (e.g. huskies) or machines. The term is used primarily in connection with travel over snow and ice, and was commo ...

. Before beginning the march south—a return distance of —approximately of stores had to be taken to the base depot at Minna Bluff Minna Bluff is a rocky promontory at the eastern end of a volcanic Antarctic peninsula projecting deep into the Ross Ice Shelf at . It forms a long, narrow arm which culminates in a south-pointing hook feature (Minna Hook), and is the subject of re ...

. This phase of the task lasted until 28 December. Mackintosh had divided his forces into two parties, himself in charge of one and Joyce of the other. The two men continued to disagree over methods; finally, Joyce confronted Mackintosh with incontrovertible evidence that his party's methods were much the more effective, and Mackintosh capitulated. "I never came across such an idiot in charge of men", Joyce wrote in his diary.

The weaker members of the party—Arnold Spencer-Smith

Arnold Patrick Spencer-Smith (17 March 1883 – 9 March 1916) was an English clergyman and amateur photographer who joined Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition as chaplain on the Ross Sea party, who were ...

and Mackintosh himself—were by this time showing signs of physical breakdown, as the long march south began from Bluff Depot towards Mount Hope at 83°30′S, where the final depot was to be laid. The party was reduced to six when three men were forced to turn back because of a Primus stove failure. With Mackintosh and Joyce in the final party were Spencer-Smith, Ernest Wild

Henry Ernest Wild AM (10 August 1879 – 10 March 1918), known as Ernest Wild, was a British Royal Naval seaman and Antarctic explorer, a younger brother of Frank Wild. Unlike his more renowned brother, who went south on five occasions, Ernes ...

(younger brother of Frank), Dick Richards and Victor Hayward

Victor George Hayward (23 October 1887 – 8 May 1916) was a London-born accounts clerk whose taste for adventure took him to Antarctica as a member of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–17. He had previo ...

. With four dogs they trekked southward, increasingly afflicted by frostbite, snow blindness

Photokeratitis or ultraviolet keratitis is a painful eye condition caused by exposure of insufficiently protected eyes to the ultraviolet (UV) rays from either natural (e.g. intense sunlight) or artificial (e.g. the electric arc during welding) ...

and, eventually, scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease, disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, ch ...

. Spencer-Smith collapsed, and thereafter had to be carried on the sledge. Mackintosh, barely able to walk, fought on until the final depot was laid at Mount Hope. On the homeward journey the effective leadership of the party fell increasingly to Joyce, as Mackintosh's condition deteriorated until, like Spencer-Smith, he had to be carried on the sledge. The journey became a protracted struggle which eventually cost the life of Spencer-Smith and took the others to the limits of their endurance. Mackintosh suffered further physical and mental collapse, and had to be left in the tent while Joyce, himself suffering from severe snow blindness,Tyler-Lewis, pp. 190–193 led the rest to the safety of Hut Point. He, Dick Richards and Ernest Wild then returned for Mackintosh, reaching his tent on March the 16th. Joyce wrote that evening "Good going passed Smith's grave 10.45 + had lunch at Depot. Saw Skippers camp just after + looking through the glasses found him outside the tent much to the joy of all hands as we expected him to be down."McOrist, p. 298 The five survivors were all back at Hut Point on 18 March 1916.Tyler-Lewis, p. 193

Rescue

All five men were showing symptoms of scurvy with varying severity. However, a diet of fresh seal meat, rich inVitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits and vegetables, also sold as a dietary supplement and as a topical 'serum' ingredient to treat melasma (dark pigment spots) ...

, enabled them to recover slowly. By mid-April they were ready to consider travelling the final across the frozen sea to the base at Cape Evans.Bickel, pp. 208–209

Joyce tested the sea-ice on 18 April and found it firm, but the following day a blizzard from the south swept all the ice away.Bickel, p. 209 The ambience at Hut Point was gloomy, and the unrelieved diet of seal was depressing. This seemed particularly to affect Mackintosh, and on 8 May, despite the urgent pleadings of Joyce, Richards and Ernest Wild, he decided to risk the re-formed ice and walk to Cape Evans. Victor Hayward volunteered to accompany him. Joyce recorded in his diary: "I fail to understand how these people are so anxious to risk their lives again". Shortly after their departure a blizzard descended, and the two were never seen again.

Joyce and the others learned the fate of Mackintosh and Hayward only when they were finally able to reach Cape Evans in July. Joyce immediately set about organising searches for traces of the missing men; in the subsequent months parties were sent to search the coasts and the islands in McMurdo Sound, but to no avail. Joyce also organised journeys to recover geological samples left on the Barrier and to visit the grave of Spencer-Smith, where a large cross was erected. In the absence of the ship, the seven remaining survivors lived quietly, until on 10 January 1917, the refitted ''Aurora'' arrived with Shackleton aboard to take them home. They learned then that their depot-laying efforts had been futile, Shackleton's ship ''Endurance'' having been crushed by the Weddell Sea ice nearly two years previously.

Later life

Post-expedition career

After his return to New Zealand Joyce was hospitalised, mainly from the effects of snow blindness, and according to his own account had to wear dark glasses for a further 18 months. During this period he married Beatrice Curtlett from Christchurch. He was now probably unfit for further polar work, although he attempted, unsuccessfully, to rejoin the Navy in 1918.Tyler-Lewis, p. 253 In September 1919 he was seriously injured in a car accident, which led to months of convalescence followed by a return to England.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 254–255 In 1920 he signed up for a new Antarctic expedition to be led by John Cope of the Ross Sea party, but this venture proved abortive.Tyler-Lewis, p. 256 He continued to maintain his claims to financial compensation from Shackleton, which caused a breach between them, and he was not invited to join Shackleton's ''Quest'' expedition which departed in 1921. He applied to join the British Mount Everest expedition of 1921–22, but was rejected.Tyler-Lewis, pp. 257–258 He was in the public eye again in 1923 when he was awarded the Albert Medal for his efforts to save the lives of Mackintosh and Spencer-Smith during the 1916 depot-laying journey. Richards received the same award; Hayward, and Ernest Wild, who had died of typhoid during naval service in the Mediterranean in 1918, received the award posthumously. In 1929 Joyce published a contentious version of his diaries under the title ''The South Polar Trail'', in which he boosted his own role, played down the contributions of others, and incorporated fictitious colourful details.Tyler-Lewis, p. 259 Thereafter he indulged in various schemes for further expeditions, and wrote numerous articles and stories based on his exploits before settling into a quiet life as a hotel porter in London. Bickel's assertion that Joyce lived into his eighties, beyond the date (1958) of the first Antarctic crossing byVivian Fuchs

Sir Vivian Ernest Fuchs ( ; 11 February 1908 – 11 November 1999) was an English scientist-explorer and expedition organizer. He led the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition which reached the South Pole overland in 1958.

Biography

Fuc ...

and his party, is not supported by any other source. Joyce died from natural causes, aged about 65, on 2 May 1940.Tyler-Lewis, p. 263 He is commemorated in Antarctica by Mount Joyce

Mount Joyce is a prominent, dome-shaped mountain, high, standing on the south side of David Glacier, northwest of Mount Howard in the Prince Albert Mountains of Victoria Land, Antarctica. It was first mapped by the British Antarctic Expedit ...

at .

Assessment

The polar historian Roland Huntford sums up Joyce as a "strange mixture of fraud, flamboyance and ability". This mixed assessment is endorsed in the assortment of views expressed by those associated with him. Dick Richards of the Ross Sea party described him as "a kindly soul and a good pal", and others shared the favourable opinions expressed by Scott and Markham, confirming Joyce as a "jolly good sort", though unsuited for command. On the other hand, Eric Marshall of the Nimrod Expedition had found him "of limited intelligence, resentful and incompatible", whileJohn King Davis

John King Davis (19 February 1884 – 8 May 1967) was an English-born Australian explorer and navigator notable for his work captaining exploration ships in Antarctic waters as well as for establishing meteorological stations on Macquar ...

, when refusing to join the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, told Shackleton: "I absolutely decline to be associated with any enterprise with which people of the Joyce type are connected".

Joyce's versions of events recorded in his published diaries have been described as unreliable and sometimes as outright invention—a "self-aggrandizing epic". Specific examples of this "fabulism" include his self-designation as "Captain" after the Ross Sea expedition; his invented claim to have seen Scott's death tent on the Barrier; the misrepresentation of his instructions from Shackleton regarding his sledging role, and his assertion of independence in the field; his claim to have been offered a place on the transcontinental party when Shackleton had made it clear he did not want him there; and his habit, late in life, of writing anonymously to the press praising "the famous Polar Explorer Ernest Mills Joyce".Tyler-Lewis, p. 262 This self-promotion neither surprised nor upset his former comrades. "It is what I would have expected", said Richards. "He was bombastic ..but true-hearted and a staunch friend". Alexander Stevens, the party's chief scientist, concurred. They knew that Joyce, for all his swaggering style, had the will and determination to "drag men back from certain death". Lord Shackleton

Edward Arthur Alexander Shackleton, Baron Shackleton, (15 July 1911 – 22 September 1994) was a British geographer, Royal Air Force officer and Labour Party politician.

Early life and career

Born in Wandsworth, London, Shackleton was the you ...

, the explorer's son, named Joyce (with Mackintosh and Richards) as "one of those who emerge from the (Ross Sea party) story as heroes".Bickel, p. vii

See also

*List of Antarctic expeditions

This list of Antarctic expeditions is a chronological list of expeditions involving Antarctica. Although the existence of a southern continent had been hypothesized as early as the writings of Ptolemy in the 1st century AD, the South Pole was ...

Notes and references

Notes ReferencesSources

*Bickel, Lennard: ''Shackleton's Forgotten Men'' Random House, London, 2000 *Fisher, M and J: ''Shackleton'' (biography) James Barrie Books, London, 1957 *Huxley, Elspeth: ''Scott of the Antarctic'' Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1977 * Huntford, Roland: ''Shackleton'' (biography) Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1985 * *McOrist, Wilson ''Shackleton's Heroes'' The Robson Press, an imprint of Biteback Publishing, London, 2015 * Riffenburgh, Beau: ''Nimrod'' Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2004 * Scott, Robert Falcon:''The Voyage of the Discovery'' Smith, Elder & Co, London, 1905 * Shackleton, Ernest: ''South'' Century Limited edition, ed. Peter King, London, 1991 * Tyler-Lewis, Kelly: ''The Lost Men'' Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2007 * Wilson, Edward: ''Diary of the Discovery Expedition'' Blandford Press, London, 1975 *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Joyce, Ernest 1875 births 1940 deaths English explorers Explorers of Antarctica Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition People educated at the Royal Hospital School People from Bognor Regis Recipients of the Albert Medal (lifesaving) Recipients of the Polar Medal Royal Navy sailors