Ernest Hanbury Hankin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Hanbury Hankin (4 February 1865 – 29 March 1939) was an English bacteriologist, aeronautical theorist and naturalist. Working mainly in India, he studied

Hankin studied

Hankin studied

During the thirty years that he spent in India, Hankin took interest not just in tropical diseases but also the effects of opium and the action of cobra

During the thirty years that he spent in India, Hankin took interest not just in tropical diseases but also the effects of opium and the action of cobra  Hankin protested the introduction of the 1876 British Act against

Hankin protested the introduction of the 1876 British Act against

English translation of 1896 paper on bacteriophages

Hankin, E. H. (1914). Animal flight; a record of observation. Illife and sons, London

Study of Bird Flight (1911)

Nationalism and the communal mind (1937)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hankin, Ernest Hanbury English naturalists English microbiologists English non-fiction writers English male non-fiction writers Alumni of University College London People from Ware, Hertfordshire 1865 births 1939 deaths

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, cholera and other diseases. He is often considered as among the first to detect bacteriophage activity and suggested that their presence in the waters of the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

and Yamuna

The Yamuna ( Hindustani: ), also spelt Jumna, is the second-largest tributary river of the Ganges by discharge and the longest tributary in India. Originating from the Yamunotri Glacier at a height of about on the southwestern slopes of B ...

rivers may have had a role in restricting the outbreaks of cholera. Apart from his professional studies, he took considerable interest in the Islamic geometric patterns

Islamic geometric patterns are one of the major forms of Islamic ornament, which tends to avoid using figurative images, as it is forbidden to create a representation of an important Islamic figure according to many holy scriptures.

The ge ...

in Mughal architecture ("Saracenic art" in the language of his day) as well as the soaring flight of birds, culture and its impact on education. He was sometimes criticized for being overzealous in his research methods.

Early life

Ernest Hankin was born inWare, Hertfordshire

Ware is a town in Hertfordshire, England close to the county town of Hertford. It is also a civil parish in East Hertfordshire district.

Location

The town lies on the north–south A10 road which is partly shared with the east–west A414 (fo ...

, his father Rev. D. B. Hankin was later a vicar of St Jude's, Mildmay Grove in North London. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School from 1875 to 1882 and went to study medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

Medical School and matriculated from St John's College, Cambridge in 1886. He was a Hutchinson Student and Scholar who passed with first class in both parts of the Natural Science Tripos in 1888 and 1889. He took a keen interest in bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

and decided against a career in medicine. In 1890 he was elected Hutchinson Student in Pathology and by the end of the year, he was admitted as a Fellow in November. He obtained the degree of MA in 1893 and Sc.D. in 1905 before working under Professor Charles Roy at his Pathological Laboratory in Trinity College London

Trinity College London (TCL) is an examination board based in London, United Kingdom, which offers graded and diploma qualifications (up to postgraduate level) across a range of disciplines in the performing arts and English language learning and ...

. His early studies in bacteriology included a new staining technique using aniline dye

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starting m ...

s (1886), some studies on anthrax in collaboration with F.F. Wesbrook, immunity and the role of " alexins". He extracted an albumose fraction from anthrax cultures that he claimed suppressed the host immune system. Inoculation of small quantities of this albumose protein made rabbits immune to anthrax. He worked under Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the bacteri ...

for some time in Berlin and under Louis Pasteur in Paris before he accepted a position in India as Chemical Examiner, Government Analyst and Bacteriologist for the United Provinces, Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

and the Central Provinces and was posted at a laboratory in Agra

Agra (, ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital New Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra i ...

in 1892.

Even early in his undergraduate years, he gained a reputation for conducting scientific experiments on himself. He was known for overdosing himself with medication and rolling a heated cannonball

A round shot (also called solid shot or simply ball) is a solid spherical projectile without explosive charge, launched from a gun. Its diameter is slightly less than the bore of the barrel from which it is shot. A round shot fired from a lar ...

over himself to speed up digestion. While on a beach at Dunwich in 1885, he saved a girl from drowning and the local newspapers hoped that he would be awarded a gallantry medal by the Royal Humane Society

The Royal Humane Society is a British charity which promotes lifesaving intervention. It was founded in England in 1774 as the ''Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned'', for the purpose of rendering first aid in cases of near dro ...

. As a bacteriologist with associations with several others like Emanuel Edward Klein ( Charles Smart Roy also worked at the Brown Animal Sanatory Institution

The Brown Animal Sanatory Institution sometimes referred to as the Brown Institution was an institute for veterinary research laboratory founded in 1871 in London, England. It was established from a sum of £20000 left by Thomas Brown in his will. ...

) who were involved in a major public debate on vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal testi ...

, Hankin was seen by some press reporters as a "vivisector" who had "escaped" to India.

India

Bacteriophages

Arriving in India, Hankin worked on the frequent outbreaks of cholera, challenging the prevalent view that " miasmas" were responsible for them. He demonstrated to the public and the officials thatmicro-organism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s were the cause and published his notes and opinions translated into Indian languages. He noted in 1896 that boiling water supplies was a reliable protection against cholera in India. The press which was against his former association with experimenters who had been accused of vivisection noted that this implied that his services as a bacteriologist were not required. A writer ''Zoophilist'' states:- "Remarkable to state, a vivisector has made a beneficial—and common-sense discovery. The discoverer in this case is Mr Hankin an old antagonist of ours, whom we met in debate at Cambridge before he took ship and departed to serve as a bacteriologist in India, where he still remains." In 1896 he published, through the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines ...

, "''L'action bactericide des eaux de la Jumna et du Gange sur le vibrion du cholera''", a paper in which he described the antibacterial activity of a then unknown source in the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

and Jumna rivers in India. He noted that "It is seen that the unboiled water of the Ganges kills the cholera germ in less than 3 hours. The same water, when boiled, does not have the same effect. On the other hand, well water is a good medium for this microbe, whether boiled or filtered." He suggested that it was responsible for limiting the spread of cholera. While many observers have considered this as evidence of early observations of bacteriophage activity, some of his later experiments raise doubts. Hankin subsequently suggested that the bactericidal action was through a "volatile" agent. He further conducted experiments where he showed that Ganges water heated in hermetically sealed containers retained their ability to kill bacterial cultures while open one on heating lost their potency. A 2011 commentator adds that Hankin's initial results suggest extremely high phage counts which seem improbable. It was however not until twenty years later that phage activity was demonstrated without doubt by the experiments of Félix d'Herelle

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places

* Arabia Felix is the ancient Latin name of Yemen

* Felix, Spain, a municipality of the province Almería, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, ...

later described at the Pasteur Institute. This observation on the water of the Ganges

The Ganges ( ) (in India: Ganga ( ); in Bangladesh: Padma ( )). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international river to which India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China are the riparian states." is ...

became quite famous, and even found mention in Mark Twain's ''More Tramps Abroad''.

Hankin was responsible through his letters to officials in prompting the establishment of the Pasteur Institute of India at Kasauli

Kasauli is a town and cantonment, located in Solan district in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The cantonment was established by the British Raj in 1842 as a Colonial hill station,Sharma, Ambika"Architecture of Kasauli churches" ''The Tr ...

in 1904. One of Hankin's duties as a chemical examiner was to attend to court cases that required the analysis of scientific forensic evidence. He notes that about 700 to 1000 cases of supposed poisoning required tests for poisons to be conducted.

Researches in Bombay

Hankin moved to Bombay following an outbreak of plague in 1905. During this period he took some interest invulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

s at the Towers of Silence

A ''dakhma'' ( fa, دخمه), also known as a Tower of Silence, is a circular, raised structure built by Zoroastrians for excarnation (that is, the exposure of human corpses to the elements for decomposition), in order to avert contaminat ...

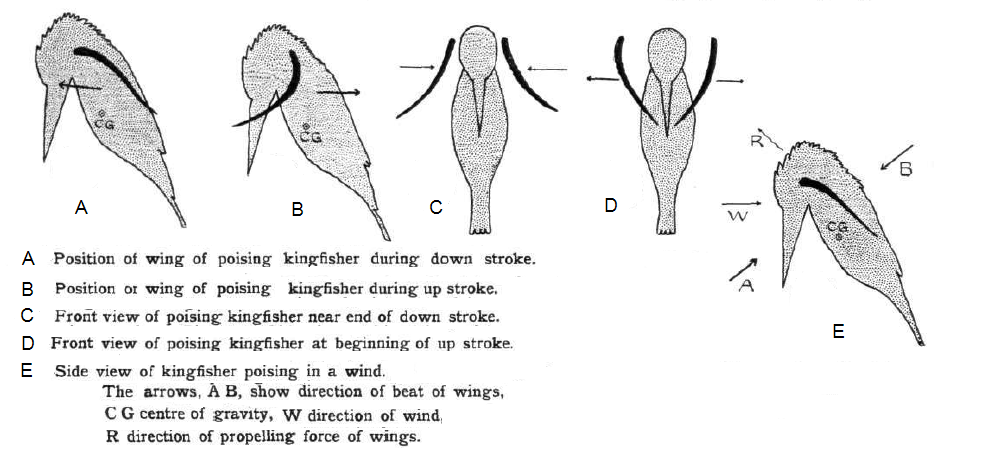

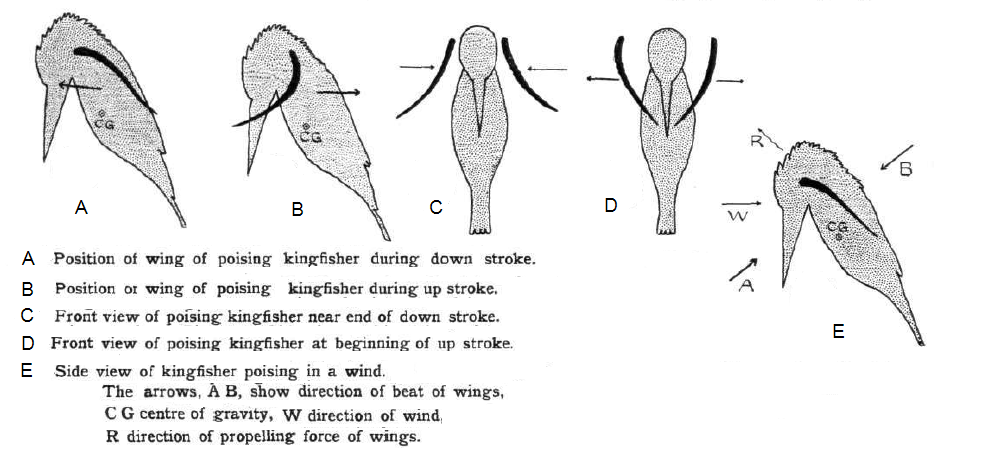

, which had apparently increased in numbers. Hankin wrote on ''the Bubonic plague'' (1899) and "On the Epidemiology of Plague" in the ''Journal of Hygiene'' in 1905, but his interests also drifted towards the subject of flight, possibly through his observations on vultures. In 1914 he published ''Animal Flight'' about soaring

Soaring may refer to:

* Gliding, in which pilots fly unpowered aircraft known as gliders or sailplanes

* Lift (soaring), a meteorological phenomenon used as an energy source by some aircraft and birds

* ''Soaring'' (magazine), a magazine produced ...

flight in birds, based on observations he made, particularly of gulls and vultures, in Agra

Agra (, ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital New Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra i ...

. He introduced a technique to plot the flight path of soaring birds by tracing their movements on a horizontal mirror. He identified thermals and currents as a requirement for soaring and dynamic soaring. His work on soaring birds caught the interest of Cambridge mathematician turned meteorologist Gilbert Walker who was also at Simla who discussed the role and nature of thermals and eddies in providing birds with the lift needed. With D. M. S. Watson

Prof David Meredith Seares Watson FRS FGS HFRSE LLD (18 June 1886 – 23 July 1973) was the Jodrell Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at University College, London from 1921 to 1951.

Biography

Early life

Watson was born in the Highe ...

, at the time a lecturer in vertebrate palaeontology at University College London, he also published a pioneering paper on the flight of pterodactyls in the ''Aeronautical Journal'' (1914).

Hankin studied

Hankin studied immune response

An immune response is a reaction which occurs within an organism for the purpose of defending against foreign invaders. These invaders include a wide variety of different microorganisms including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi which could ...

s with experiments where he injected rabbits with tetanus to induce immunity in them. He took their serum and injected them in rats to demonstrate how the immunity could be transferred. Hankin started the practice of using potassium permanganate

Potassium permanganate is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula KMnO4. It is a purplish-black crystalline salt, that dissolves in water as K+ and , an intensely pink to purple solution.

Potassium permanganate is widely used in the c ...

in wells as a means for controlling cholera. His theory was that the germs needed organic matter to survive and that permanganate would oxidize it and make it unavailable. In 1895 the press noted that Hankin had been overzealous with his experimentation and had infected himself with cholera by drinking water that he thought had been treated using potassium permanganate

Potassium permanganate is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula KMnO4. It is a purplish-black crystalline salt, that dissolves in water as K+ and , an intensely pink to purple solution.

Potassium permanganate is widely used in the c ...

. The editors of the journal ''Science Progress'' lamented that Hankin had been largely unrecognized for his contributions to human health and hygiene: "Hankin's work has been of greater importance to India than the work or no-work of many persons who have received more honours and acknowledgements. Really, in some respects the British remain barbarians to the present day, and he should write an article on the mental ability of the Indian Powers-that-Be !" The efficacy of this method of disinfecting wells was however questioned in later studies. When he retired in 1922, he was awarded a Kaisar-i-Hind Medal

The Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for Public Service in India was a medal awarded by the Emperor/Empress of India between 1900 and 1947, to "any person without distinction of race, occupation, position, or sex ... who shall have distinguished himself (o ...

of the first class.

Other areas of work

During the thirty years that he spent in India, Hankin took interest not just in tropical diseases but also the effects of opium and the action of cobra

During the thirty years that he spent in India, Hankin took interest not just in tropical diseases but also the effects of opium and the action of cobra venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a st ...

, working sometimes in collaboration with Albert Calmette

Léon Charles Albert Calmette ForMemRS (12 July 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, an attenuated for ...

and Waldemar Haffkine

Waldemar Mordechai Wolff Haffkine ( uk, Володимир Мордехай-Вольф Хавкін; russian: Мордехай-Вольф Хавкин; 15 March 1860 Odessa – 26 October 1930 Lausanne) was a Ukrainian-French bacteriologist kno ...

. Outside of his health related research he took an interest in such diverse topics as the fauna inhabiting the dome of the Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal (; ) is an Islamic ivory-white marble mausoleum on the right bank of the river Yamuna in the Indian city of Agra. It was commissioned in 1631 by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan () to house the tomb of his favourite wife, Mu ...

, insect camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

and its military application, native folklore and art.

Hankin protested the introduction of the 1876 British Act against

Hankin protested the introduction of the 1876 British Act against vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal testi ...

into India. He wrote that it came in the way of scientific research and that the legal measures should only be aimed to control cruelty imposed by traditional Indian practices noting that "so far as Englishmen of science are concerned the prevention of wanton or unnecessary cruelty to animals might safely be left to their good taste and good feeling."

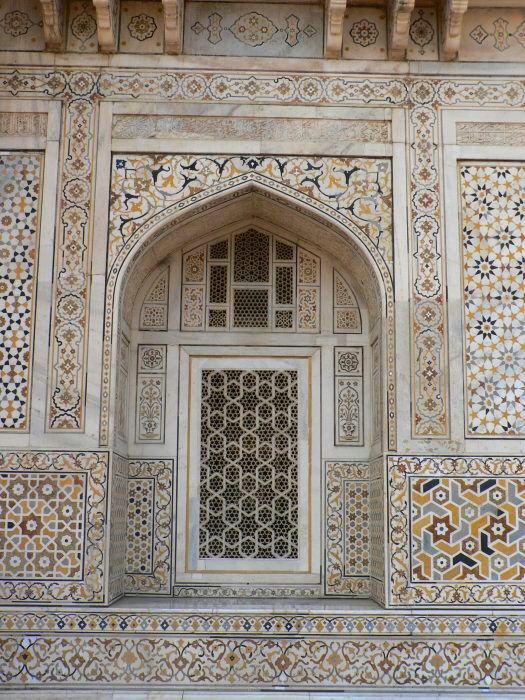

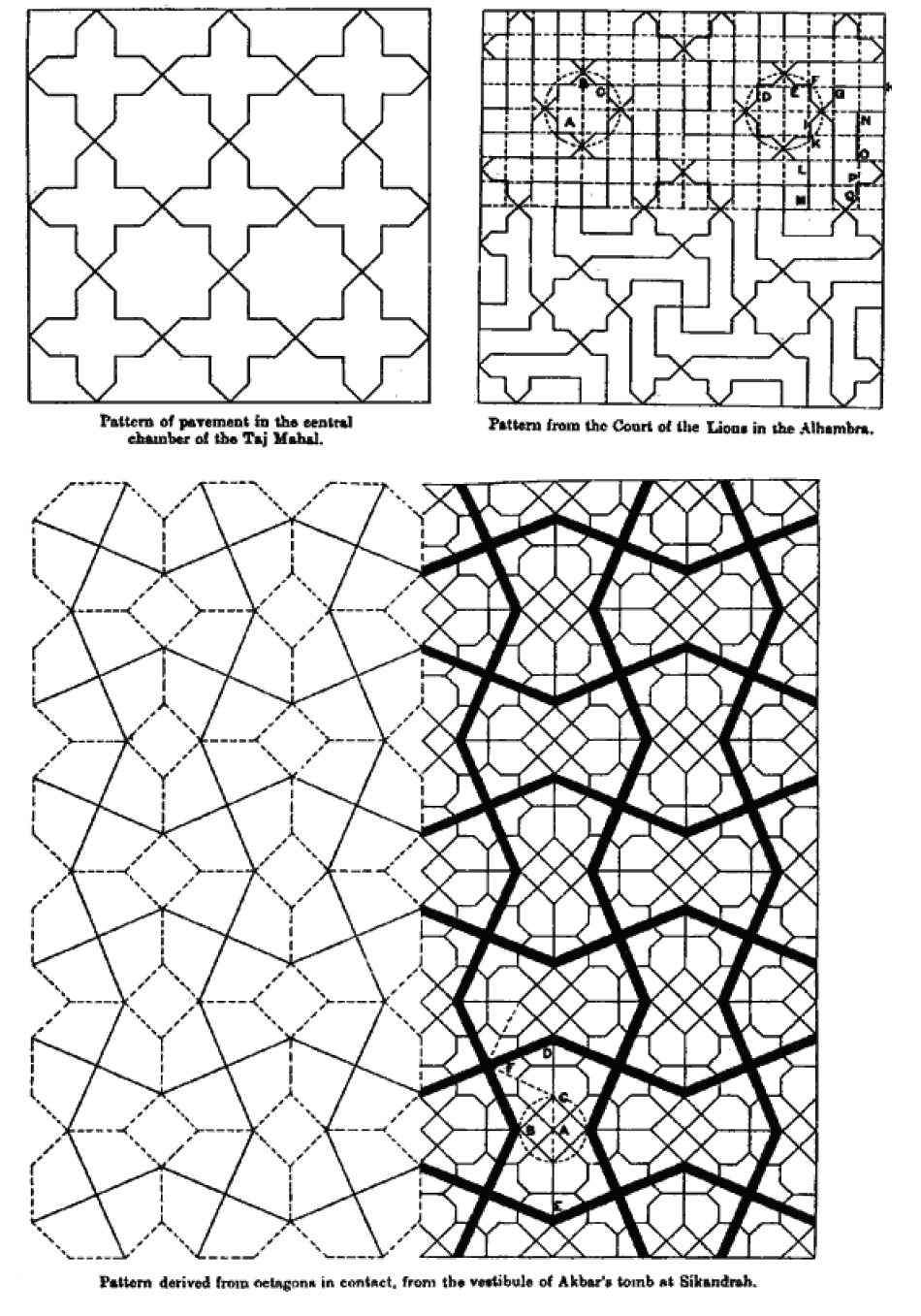

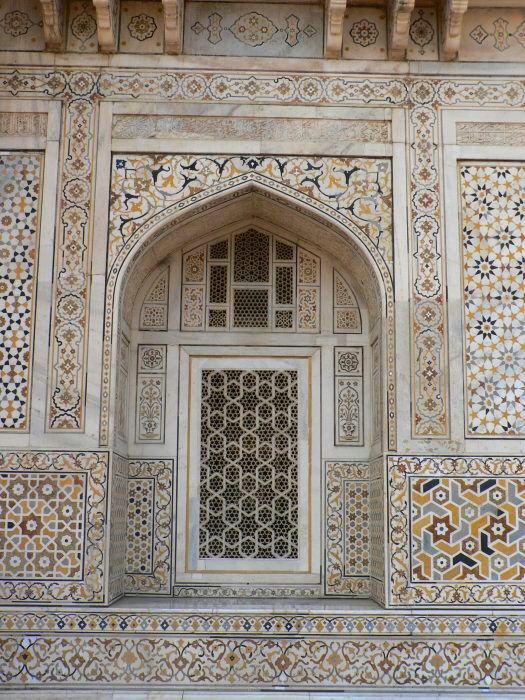

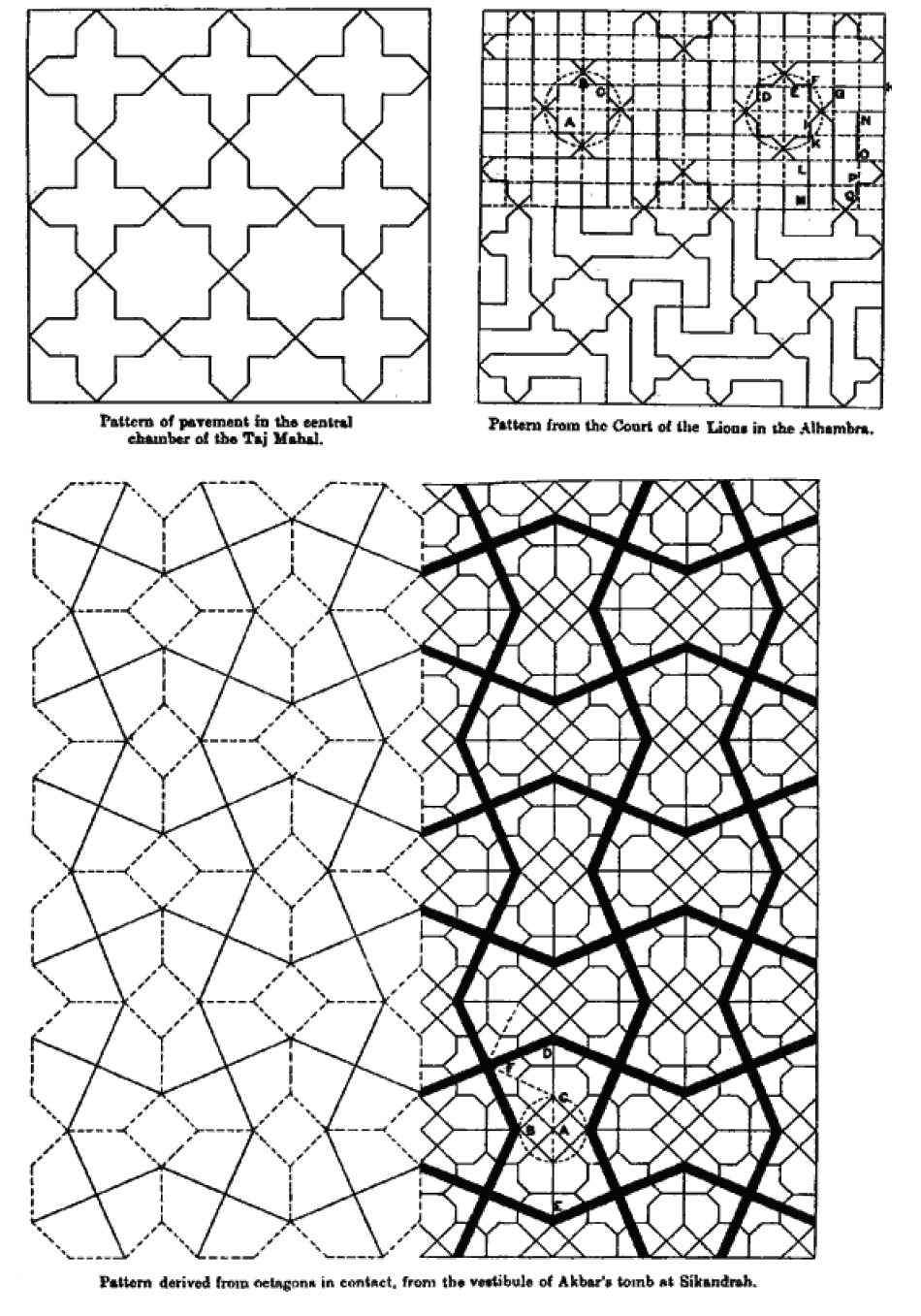

While in India, Hankin studied the Islamic geometric patterns

Islamic geometric patterns are one of the major forms of Islamic ornament, which tends to avoid using figurative images, as it is forbidden to create a representation of an important Islamic figure according to many holy scriptures.

The ge ...

that he observed, publishing some of them in 1905. His main findings only found publication from 1925, after his return to the UK, when "The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art" finally appeared in ''Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India'', under the editorship of J. F. Blakiston. This and later writings have influenced computer scientists and mathematicians in recent years, notably Craig S. Kaplan.

Return to England

Hankin returned to England in the early 1920s, living for a while in the Norfolk Broads and spending winters at Torquay or Newquay before finally moving to Brighton. He took a great interest in sailing. He experimented with new designs of sails and methods to combat sea sickness. Together with his old pathologist colleagues include Professor Roy, he built a prototype raft he dubbed ''The Bacillus'', made of kerosene tins and metal rods with an "umbrella sail" based on an idea fromPercy Pilcher

Percy Sinclair Pilcher (16 January 1867 – 2 October 1899) was a British inventor and pioneer aviator who was his country's foremost experimenter in unpowered flight near the end of the nineteenth century.

After corresponding with Otto Lilien ...

. Unfortunately, the maiden voyage at Colwyn Bay

Colwyn Bay ( cy, Bae Colwyn) is a town, community and seaside resort in Conwy County Borough on the north coast of Wales overlooking the Irish Sea. It lies within the historic county of Denbighshire. Eight neighbouring communities are incorpo ...

ended with the boat sinking, while the crew had to be rescued by onlookers.

He continued his research in the dynamics of animal flight. He was an associate fellow of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain. In 1923, ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' magazine carried a short notice on his exploits: "Much interest is taken in England in the problems of air gliding. People on a London common saw a strange sight—an elderly gentleman playing with a toy aeroplane. He was Dr. E. H. Hankin ... and he was experimenting with a model glider."

Hankin took a special interest in education and the role of intuition. He believed that modern methods of education tended to damage innate intuition. In 1922 he made a study of Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

and their education. He calculated, based on statistics for the years between 1851 and 1900, that a man had 46 times greater chance of being elected to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

if he was a Quaker or of Quaker descent. He attributed this to the superior mental ability that came out of enhancing intuition rather than the development of conscious reasoning that certain educational systems imposed. In 1920, he published a book on the subject ''The Mental Limitations of the Expert'' in which he considered examples of where intuition was correct, despite failing rational explanation. He also considered how certain castes in India, such as the money-lending Baniyas, received a training in mental arithmetic that was superior to the system of education imposed by the English in India. He suggested that logical reasoning actually comes in the way of business instinct. He expanded on this work which was published with a foreword by C. S. Myers, co-founder of the British Psychological Society, and titled it ''Common Sense and its Cultivation'' (1926). The book was reprinted as recently as 2002 by Routledge. A reviewer compared it with Francis Galton's '' Inquiry Into Human Faculty''.

In his 1928 book, ''The Cave Man's Legacy'', Hankin compares the behaviour of apes and primitive man and how they play a role in the life of modern humans. In a later book, he explored the same influences in the outbreaks of violence in his ''Nationalism and the Communal Mind'' (1937).

Publications

Hankin's publications include: ;Books * (1914) ''Animal Flight: A Record of Observation'': London: Iliffe. * (1920) ''The Mental Limitations of the Expert''. Calcutta & London: Butterworth. * (1925) ''Common Sense and its Cultivation''. London: K. Paul. * (1925) ''The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art''. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing. * (1928) ''The Cave Man's Legacy''. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. * (1937) ''Nationalism and the Communal Mind''. London: Watts & Co. ;Papers * (1885) "Some new methods of using aniline dyes for staining bacteria", ''Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science'' (new series) xxvii: 401. * (1889–92) "A new result of the injection of ferments", ''Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society'' vii: 16. * (1889) "Immunity produced by an Albumose isolated from Anthrax cultures", ''British Medical Journal'' ii: 810. * (1890) "Report on the Conflict between the Organism and the Microbe", ''British Medical Journal'' ii: 65. * (1890) "Indications for the cure of Infectious Diseases", ''Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science'', 1890: 856. * (1890) "On a Bacteria-killing Globulin", ''Proceedings of the Royal Society B'' 48:93. * (1891) "On Immunity (read before the Congress of Hygiene and Demography, London, August 1891", ''Lancet'' ii: 339. * (1892) "Remarks on Haffkine's method of Protective Inoculation against Cholera", ''British Medical Journal'' ii: 569. * (1905) "On some discoveries of the methods of design employed in the Mohammedan art", ''Journal of the Society of Arts''. 53:461–477. * (1913) "On dust-raising winds and descending currents". ''Memoirs of the India Meteorological Department'' 22(6):565-573. * (1925) "The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art". ''Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India''. * (1930/31) "The pied piper of Hamlyn and the coming of the Black Death". ''Torquay Natural History Society Transactions & Proceedings''. 6:23-31.Notes

References

External links

English translation of 1896 paper on bacteriophages

Hankin, E. H. (1914). Animal flight; a record of observation. Illife and sons, London

Study of Bird Flight (1911)

Nationalism and the communal mind (1937)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hankin, Ernest Hanbury English naturalists English microbiologists English non-fiction writers English male non-fiction writers Alumni of University College London People from Ware, Hertfordshire 1865 births 1939 deaths