Enola Gay on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a

''Enola Gay'' was personally selected by

''Enola Gay'' was personally selected by

On 5 August 1945, during preparation for the first atomic mission, Tibbets assumed command of the aircraft and named it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, who, in turn, had been named for the heroine of a novel. When it came to selecting a name for the plane, Tibbets later recalled that:

In the early morning hours, just prior to the 6 August mission, Tibbets had a young Army Air Forces maintenance man, Private Nelson Miller, paint the name just under the pilot's window. Regularly-assigned aircraft commander Robert Lewis was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission and became furious when he arrived at the aircraft on the morning of 6 August to see it painted with the now-famous nose art.

On 5 August 1945, during preparation for the first atomic mission, Tibbets assumed command of the aircraft and named it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, who, in turn, had been named for the heroine of a novel. When it came to selecting a name for the plane, Tibbets later recalled that:

In the early morning hours, just prior to the 6 August mission, Tibbets had a young Army Air Forces maintenance man, Private Nelson Miller, paint the name just under the pilot's window. Regularly-assigned aircraft commander Robert Lewis was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission and became furious when he arrived at the aircraft on the morning of 6 August to see it painted with the now-famous nose art.

After leaving Tinian, the three aircraft made their way separately to

After leaving Tinian, the three aircraft made their way separately to  ''Enola Gay'' returned safely to its base on Tinian to great fanfare, touching down at 2:58 pm, after 12 hours 13 minutes. ''The Great Artiste'' and ''Necessary Evil'' followed at short intervals. Several hundred people, including journalists and photographers, had gathered to watch the planes return. Tibbets was the first to disembark and was presented with the

''Enola Gay'' returned safely to its base on Tinian to great fanfare, touching down at 2:58 pm, after 12 hours 13 minutes. ''The Great Artiste'' and ''Necessary Evil'' followed at short intervals. Several hundred people, including journalists and photographers, had gathered to watch the planes return. Tibbets was the first to disembark and was presented with the

On 6 November 1945, Lewis flew the ''Enola Gay'' back to the United States, arriving at the 509th's new base at

On 6 November 1945, Lewis flew the ''Enola Gay'' back to the United States, arriving at the 509th's new base at

''Enola Gay'' became the center of a controversy at the Smithsonian Institution when the museum planned to put its fuselage on public display in 1995 as part of an exhibit commemorating the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit, ''The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War,'' was drafted by the Smithsonian's

''Enola Gay'' became the center of a controversy at the Smithsonian Institution when the museum planned to put its fuselage on public display in 1995 as part of an exhibit commemorating the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit, ''The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War,'' was drafted by the Smithsonian's

Restoration work began in 1984, and eventually required 300,000 staff hours. While the fuselage was on display, from 1995 to 1998, work continued on the remaining unrestored components. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the National Air and Space Museum's

Restoration work began in 1984, and eventually required 300,000 staff hours. While the fuselage was on display, from 1995 to 1998, work continued on the remaining unrestored components. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the National Air and Space Museum's  The display of the ''Enola Gay'' without reference to the historical context of World War II, the Cold War, or the development and deployment of nuclear weapons aroused controversy. A petition from a group calling themselves the Committee for a National Discussion of Nuclear History and Current Policy bemoaned the display of ''Enola Gay'' as a technological achievement, which it described as an "extraordinary callousness toward the victims, indifference to the deep divisions among American citizens about the propriety of these actions, and disregard for the feelings of most of the world's peoples". It attracted signatures from notable figures including historian

The display of the ''Enola Gay'' without reference to the historical context of World War II, the Cold War, or the development and deployment of nuclear weapons aroused controversy. A petition from a group calling themselves the Committee for a National Discussion of Nuclear History and Current Policy bemoaned the display of ''Enola Gay'' as a technological achievement, which it described as an "extraordinary callousness toward the victims, indifference to the deep divisions among American citizens about the propriety of these actions, and disregard for the feelings of most of the world's peoples". It attracted signatures from notable figures including historian

The Smithsonian's site on ''Enola Gay'' includes links to crew lists and other details

{{Portal bar, World War II Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Individual aircraft of World War II Individual aircraft in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution Boeing B-29 Superfortress

Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Paul Tibbets

Paul Warfield Tibbets Jr. (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007) was a brigadier general in the United States Air Force. He is best known as the aircraft captain who flew the B-29 Superfortress known as the '' Enola Gay'' (named after his mot ...

. On 6 August 1945, piloted by Tibbets and Robert A. Lewis during the final stages of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, it became the first aircraft to drop an atomic bomb in warfare. The bomb, code-named "Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

", was targeted at the city of Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

, Japan, and caused the destruction of about three quarters of the city. ''Enola Gay'' participated in the second nuclear attack as the weather reconnaissance aircraft for the primary target of Kokura

is an ancient castle town and the center of Kitakyushu, Japan, guarding the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshu and Kyushu with its suburb Moji. Kokura is also the name of the penultimate station on the southbound San'yō Shinkansen li ...

. Clouds and drifting smoke resulted in a secondary target, Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, being bombed instead.

After the war, the ''Enola Gay'' returned to the United States, where it was operated from Roswell Army Air Field

Roswell may refer to:

* Roswell incident

Places in the United States

* Roswell, Colorado, a former settlement now part of Colorado Springs

* Roswell, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta

* Roswell, Idaho

* Roswell, New Mexico, known for the purported ...

, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

. In May 1946, it was flown to Kwajalein

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese: ) is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking residents (about 1,000 mostly U.S. civilia ...

for the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

s in the Pacific, but was not chosen to make the test drop at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Second ...

. Later that year, it was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

and spent many years parked at air bases exposed to the weather and souvenir hunters, before being disassembled and transported to the Smithsonian's storage facility at Suitland, Maryland

Suitland is an unincorporated community and census designated place (CDP) in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States, approximately one mile (1.6 km) southeast of Washington, D.C. As of the 2020 census, its population was 25,839. Prio ...

, in 1961.

In the 1980s, veterans groups engaged in a call for the Smithsonian to put the aircraft on display, leading to an acrimonious debate about exhibiting the aircraft without a proper historical context. The cockpit and nose section of the aircraft were exhibited at the National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, also called the Air and Space Museum, is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, it opened its main building on the Nat ...

(NASM) on the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institut ...

, for the bombing's 50th anniversary in 1995, amid controversy. Since 2003, the entire restored B-29 has been on display at NASM's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, also called the Udvar-Hazy Center, is the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM)'s annex at Washington Dulles International Airport in the Chantilly area of Fairfax County, Virginia. It holds numerous ...

. The last survivor of its crew, Theodore Van Kirk

Theodore Jerome "Dutch" Van Kirk (February 27, 1921 – July 28, 2014) was a navigator in the United States Army Air Forces, best known as the navigator of the ''Enola Gay'' when it dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Upon the death o ...

, died on 28 July 2014 at the age of 93.

World War II

Early history

The ''Enola Gay'' (Model number B-29-45-MO, Serial number 44-86292, Victor number 82) was built by the Glenn L. Martin Company (later part ofLockheed Martin

The Lockheed Martin Corporation is an American aerospace, arms, defense, information security, and technology corporation with worldwide interests. It was formed by the merger of Lockheed Corporation with Martin Marietta in March 1995. It ...

) at its bomber plant in Bellevue, Nebraska, located at Offutt Field, now Offutt Air Force Base

Offutt Air Force Base is a U.S. Air Force base south of Omaha, adjacent to Bellevue in Sarpy County, Nebraska. It is the headquarters of the U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the 557th Weather Wing, and the 55th Wing (55 WG) of the Air ...

. The bomber was one of the first fifteen B-29s built to the "Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces' participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project which enabled a B-29 Superfortress bomber to drop a ...

" specification— of 65 eventually completed during and after World War II—giving them the primary ability to function as nuclear "weapon delivery" aircraft. These modifications included an extensively modified bomb bay with pneumatic doors and British bomb attachment and release systems, reversible pitch propellers that gave more braking power on landing, improved engines with fuel injection and better cooling,March, Peter R. "Enola Gay Restored". ''Aircraft Illustrated'', October 2003. and the removal of protective armor and gun turrets.

''Enola Gay'' was personally selected by

''Enola Gay'' was personally selected by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Paul W. Tibbets Jr., the commander of the 509th Composite Group, on 9 May 1945, while still on the assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in seq ...

. The aircraft was accepted by the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) on 18 May 1945 and assigned to the 393d Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, 509th Composite Group. Crew B-9, commanded by Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Robert A. Lewis, took delivery of the bomber and flew it from Omaha to the 509th base at Wendover Army Air Field

Wendover Air Force Base is a former United States Air Force base in Utah now known as Wendover Airport. During World War II, it was a training base for B-17 and B-24 bomber crews. It was the training site of the 509th Composite Group, the B-29 ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, on 14 June 1945.

Thirteen days later, the aircraft left Wendover for Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, where it received a bomb-bay modification, and flew to North Field, Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of th ...

, on 6 July. It was initially given the Victor (squadron-assigned identification) number 12, but on 1 August, was given the circle R tail markings of the 6th Bombardment Group

Alec Trevelyan (006) is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the 1995 James Bond film '' GoldenEye'', the first film to feature actor Pierce Brosnan as Bond. Trevelyan is portrayed by actor Sean Bean. The likeness of Bean as Ale ...

as a security measure and had its Victor number changed to 82 to avoid misidentification with actual 6th Bombardment Group aircraft. During July, the bomber made eight practice or training flights and flew two missions, on 24 and 26 July, to drop pumpkin bomb

Pumpkin bombs were conventional aerial bombs developed by the Manhattan Project and used by the United States Army Air Forces against Japan during World War II. It was a close replication of the Fat Man plutonium bomb with the same ballistic an ...

s on industrial targets at Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

and Nagoya

is the largest city in the Chūbu region, the fourth-most populous city and third most populous urban area in Japan, with a population of 2.3million in 2020. Located on the Pacific coast in central Honshu, it is the capital and the most pop ...

. ''Enola Gay'' was used on 31 July on a rehearsal flight for the actual mission.

The partially assembled Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

gun-type fission weapon

Gun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another. Although this is someti ...

L-11, weighing , was contained inside a × × wooden crate that was secured to the deck of the . Unlike the six uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

target discs, which were later flown to Tinian on three separate aircraft arriving 28 and 29 July, the assembled projectile with the nine uranium-235 rings installed was shipped in a single lead-lined steel container weighing that was locked to brackets welded to the deck of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Charles B. McVay III's quarters. Both the L-11 and projectile were dropped off at Tinian on 26 July 1945.

Hiroshima mission

On 5 August 1945, during preparation for the first atomic mission, Tibbets assumed command of the aircraft and named it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, who, in turn, had been named for the heroine of a novel. When it came to selecting a name for the plane, Tibbets later recalled that:

In the early morning hours, just prior to the 6 August mission, Tibbets had a young Army Air Forces maintenance man, Private Nelson Miller, paint the name just under the pilot's window. Regularly-assigned aircraft commander Robert Lewis was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission and became furious when he arrived at the aircraft on the morning of 6 August to see it painted with the now-famous nose art.

On 5 August 1945, during preparation for the first atomic mission, Tibbets assumed command of the aircraft and named it after his mother, Enola Gay Tibbets, who, in turn, had been named for the heroine of a novel. When it came to selecting a name for the plane, Tibbets later recalled that:

In the early morning hours, just prior to the 6 August mission, Tibbets had a young Army Air Forces maintenance man, Private Nelson Miller, paint the name just under the pilot's window. Regularly-assigned aircraft commander Robert Lewis was unhappy to be displaced by Tibbets for this important mission and became furious when he arrived at the aircraft on the morning of 6 August to see it painted with the now-famous nose art.

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on 6 August, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternative targets. ''Enola Gay'', piloted by Tibbets, took off from North Field, in the Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI; ch, Sankattan Siha Na Islas Mariånas; cal, Commonwealth Téél Falúw kka Efáng llól Marianas), is an unincorporated territory and commonw ...

, about six hours' flight time from Japan, accompanied by two other B-29s, ''The Great Artiste

''The Great Artiste'' was a U.S. Army Air Forces Silverplate B-29 bomber (B-29-40-MO 44-27353, Victor number 89), assigned to the 393d Bomb Squadron, 509th Composite Group. The aircraft was named for its bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan ...

'', carrying instrumentation, and a then-nameless aircraft later called ''Necessary Evil

A necessary evil is an evil that someone believes must be done or accepted because it is necessary to achieve a better outcome—especially because possible alternative courses of action or inaction are expected to be worse. It is the "lesser evi ...

'', commanded by Captain George Marquardt, to take photographs. The director of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr.

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers Officer (armed forces), officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and di ...

, wanted the event recorded for posterity, so the takeoff was illuminated by floodlights. When he wanted to taxi, Tibbets leaned out the window to direct the bystanders out of the way. On request, he gave a friendly wave for the cameras.

After leaving Tinian, the three aircraft made their way separately to

After leaving Tinian, the three aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima (, also ), known in Japan as , is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands and lies south of the Bonin Islands. Together with other islands, they form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The highest point of Iwo Jima is Mount Suribachi at high.

...

, where they rendezvoused at and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at . Navy Captain William S. "Deak" Parsons of Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 1 ...

, who was in command of the mission, armed the bomb during the flight to minimize the risks during takeoff. His assistant, Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

Morris R. Jeppson

Morris Richard Jeppson (June 23, 1922 – March 30, 2010) was a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. He served as assistant weaponeer on the '' Enola Gay'', which dropped the first atomic bomb on the ...

, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.

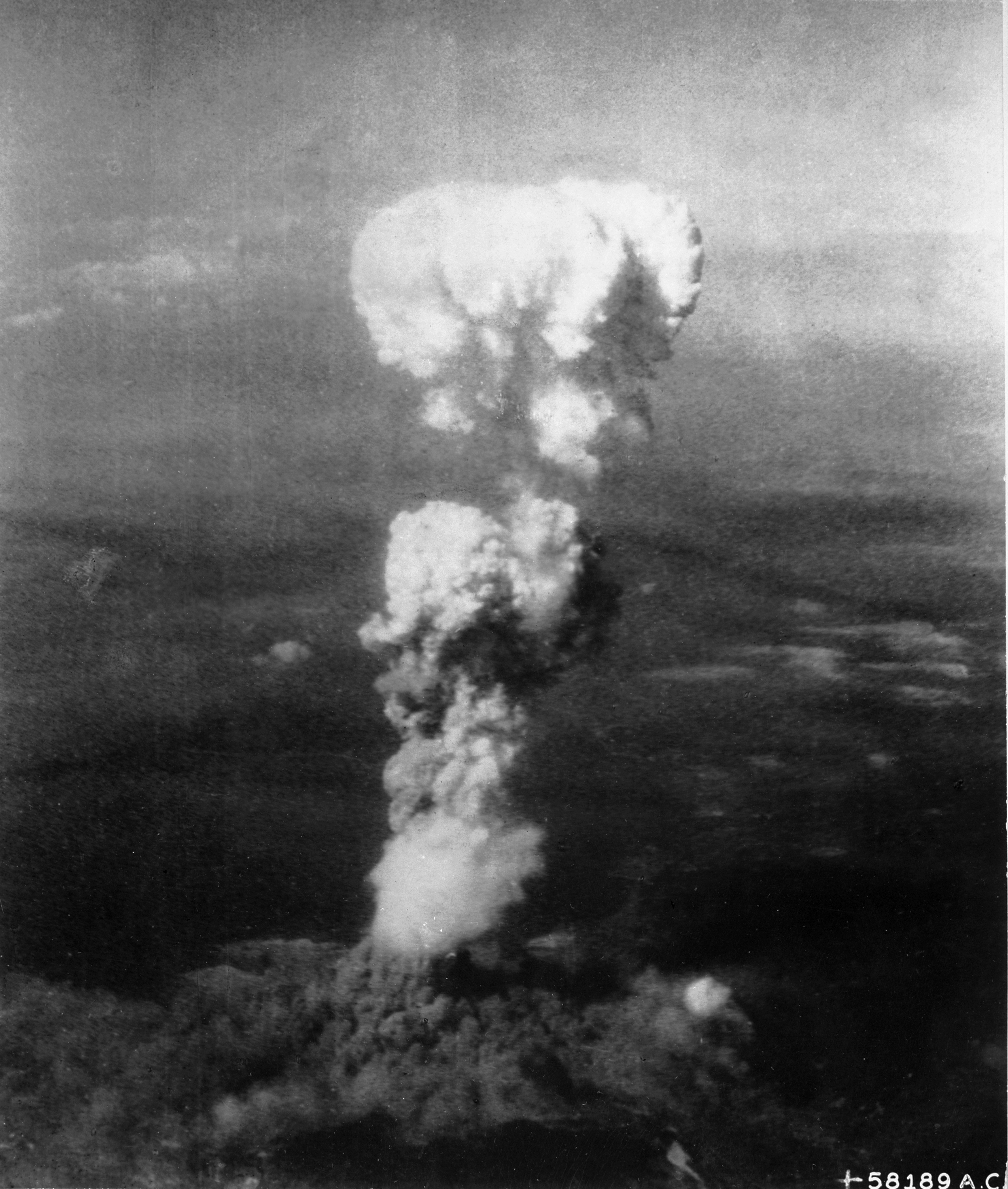

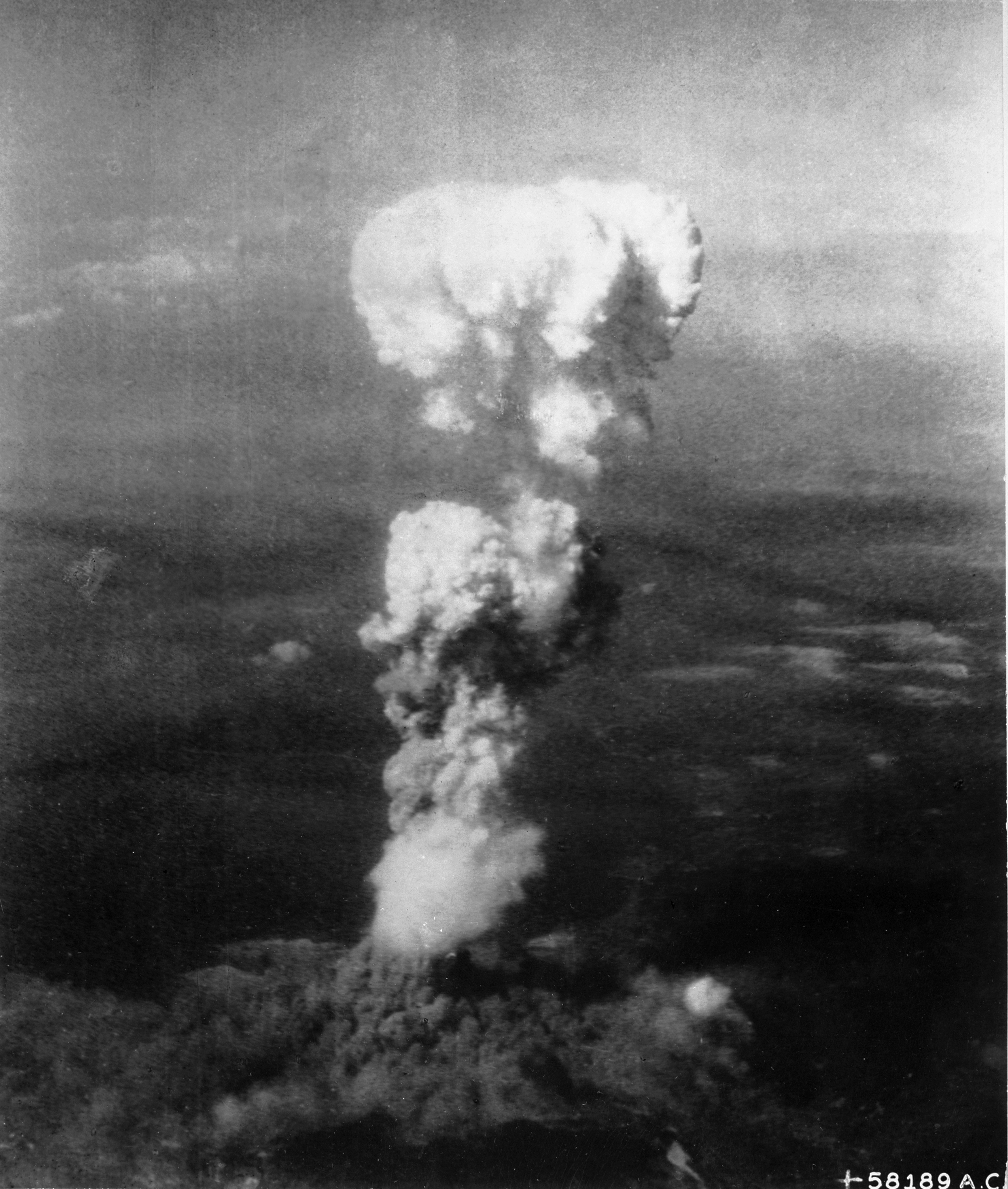

The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) went as planned, and the Little Boy took 53 seconds to fall from the aircraft flying at to the predetermined detonation height about above the city. ''Enola Gay'' traveled before it felt the shock waves from the blast. Although buffeted by the shock, neither ''Enola Gay'' nor ''The Great Artiste'' was damaged.

The detonation created a blast equivalent to . The U-235 weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.7% of its fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be ty ...

reacting. The radius of total destruction was about one mile (1.6 km), with resulting fires across . Americans estimated that of the city were destroyed. Japanese officials determined that 69% of Hiroshima's buildings were destroyed and another 6–7% damaged. Some 70,000–80,000 people, 30% of the city's population, were killed by the blast and resultant firestorm, and another 70,000 injured. Out of those killed, 20,000 were soldiers and 20,000 were Korean slave laborers.

''Enola Gay'' returned safely to its base on Tinian to great fanfare, touching down at 2:58 pm, after 12 hours 13 minutes. ''The Great Artiste'' and ''Necessary Evil'' followed at short intervals. Several hundred people, including journalists and photographers, had gathered to watch the planes return. Tibbets was the first to disembark and was presented with the

''Enola Gay'' returned safely to its base on Tinian to great fanfare, touching down at 2:58 pm, after 12 hours 13 minutes. ''The Great Artiste'' and ''Necessary Evil'' followed at short intervals. Several hundred people, including journalists and photographers, had gathered to watch the planes return. Tibbets was the first to disembark and was presented with the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

on the spot.

Nagasaki mission

The Hiroshima mission was followed by another atomic strike. Originally scheduled for 11 August, it was brought forward by two days to 9 August owing to a forecast of bad weather. This time, a nuclear bomb code-named "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

" was carried by B-29 ''Bockscar

''Bockscar'', sometimes called Bock's Car, is the name of the United States Army Air Forces B-29 bomber that dropped a Fat Man nuclear weapon over the Japanese city of Nagasaki during World War II in the secondand most recent nuclear attack in ...

'', piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney. ''Enola Gay'', flown by Captain George Marquardt's Crew B-10, was the weather reconnaissance aircraft for Kokura

is an ancient castle town and the center of Kitakyushu, Japan, guarding the Straits of Shimonoseki between Honshu and Kyushu with its suburb Moji. Kokura is also the name of the penultimate station on the southbound San'yō Shinkansen li ...

, the primary target. ''Enola Gay'' reported clear skies over Kokura, but by the time ''Bockscar'' arrived, the city was obscured by smoke from fires from the conventional bombing of Yahata by 224 B-29s the day before. After three unsuccessful passes, ''Bockscar'' diverted to its secondary target, Nagasaki, where it dropped its bomb. In contrast to the Hiroshima mission, the Nagasaki mission has been described as tactically botched, although the mission did meet its objectives. The crew encountered a number of problems in execution and had very little fuel by the time they landed at the emergency backup landing site Yontan Airfield

Yontan Airfield (also known as Yomitan Auxiliary Airfield) is a former military airfield located near Yomitan Village on the west coast of Okinawa. It was closed in July 1996 and turned over to the Japanese government in December 2006. Today it i ...

on Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

.

Crews

Hiroshima mission

''Enola Gay''s crew on 6 August 1945 consisted of 12 men. The crew was: *Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Paul W. Tibbets Jr. – pilot and aircraft commander

* Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Robert A. Lewis – co-pilot; ''Enola Gays regularly assigned aircraft commander*

* Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Thomas Ferebee

Thomas Wilson Ferebee (November 9, 1918 – March 16, 2000) was the bombardier aboard the B-29 Superfortress, ''Enola Gay'', which dropped the atomic bomb "Little Boy" on Hiroshima in 1945.

Biography

Thomas Wilson Ferebee was born on a far ...

– bombardier

* Captain Theodore "Dutch" Van Kirk – navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

* Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

William S. "Deak" Parsons, USN – weaponeer and mission commander

* First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

Jacob Beser

Jacob Beser (May 15, 1921 – June 16, 1992) was a lieutenant in the United States Army Air Forces who served during World War II. Beser was the radar specialist aboard the '' Enola Gay'' on August 6, 1945, when it dropped the Little Boy atomic ...

– radar countermeasures (also the only man to fly on both of the nuclear bombing aircraft.)

* Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

Morris R. Jeppson

Morris Richard Jeppson (June 23, 1922 – March 30, 2010) was a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. He served as assistant weaponeer on the '' Enola Gay'', which dropped the first atomic bomb on the ...

– assistant weaponeer

* Staff Sergeant

Staff sergeant is a rank of non-commissioned officer used in the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services.

History of title

In origin, certain senior sergeants were assigned to administrative, supervi ...

Robert "Bob" Caron – tail gunner*

* Staff Sergeant Wyatt E. Duzenbury – flight engineer

A flight engineer (FE), also sometimes called an air engineer, is the member of an aircraft's flight crew who monitors and operates its complex aircraft systems. In the early era of aviation, the position was sometimes referred to as the "air me ...

*

* Sergeant

Sergeant (abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other uni ...

Joe S. Stiborik – radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

operator*

* Sergeant Robert H. Shumard – assistant flight engineer*

* Private First Class

Private first class (french: Soldat de 1 classe; es, Soldado de primera) is a military rank held by junior enlisted personnel in a number of armed forces.

French speaking countries

In France and other French speaking countries, the rank (; ) ...

Richard H. Nelson – VHF radio operator*

Asterisks denote regular crewmen of the ''Enola Gay''.

Of mission commander Parsons, it was said: "There is no one more responsible for getting this bomb out of the laboratory and into some form useful for combat operations than Captain Parsons, by his plain genius in the ordnance business."

Nagasaki mission

For the Nagasaki mission, ''Enola Gay'' was flown by Crew B-10, normally assigned to '' Up An' Atom'': *Captain George W. Marquardt – aircraft commander *Second Lieutenant James M. Anderson – co-pilot *Second Lieutenant Russell Gackenbach – navigator *Captain James W. Strudwick – bombardier *Technical Sergeant James R. Corliss – flight engineer *Sergeant Warren L. Coble – radio operator *Sergeant Joseph M. DiJulio – radar operator *Sergeant Melvin H. Bierman – tail gunner *Sergeant Anthony D. Capua Jr. – assistant engineer/scannerSubsequent history

On 6 November 1945, Lewis flew the ''Enola Gay'' back to the United States, arriving at the 509th's new base at

On 6 November 1945, Lewis flew the ''Enola Gay'' back to the United States, arriving at the 509th's new base at Roswell Army Air Field

Roswell may refer to:

* Roswell incident

Places in the United States

* Roswell, Colorado, a former settlement now part of Colorado Springs

* Roswell, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta

* Roswell, Idaho

* Roswell, New Mexico, known for the purported ...

, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, on 8 November. On 29 April 1946, ''Enola Gay'' left Roswell as part of the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear weapons tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected b ...

in the Pacific. It flew to Kwajalein Atoll

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese: ) is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking residents (about 1,000 mostly U.S. civilia ...

on 1 May. It was not chosen to make the test drop at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Second ...

and left Kwajalein on 1 July, the date of the test, reaching Fairfield-Suisun Army Air Field

Travis Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base under the operational control of the Air Mobility Command (AMC), located three miles (5 km) east of the central business district of the city of Fairfield, in Solano County, California ...

, California, the next day.

The decision was made to preserve the ''Enola Gay'', and on 24 July 1946, the aircraft was flown to Davis–Monthan Air Force Base

Davis–Monthan Air Force Base (DM AFB) is a United States Air Force base southeast of downtown Tucson, Arizona. It was established in 1925 as Davis–Monthan Landing Field. The host unit for Davis–Monthan AFB is the 355th Wing (355 WG) assi ...

, Tucson, Arizona

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

, in preparation for storage. On 30 August 1946, the title to the aircraft was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

and the ''Enola Gay'' was removed from the USAAF inventory. From 1946 to 1961, the ''Enola Gay'' was put into temporary storage at a number of locations. It was at Davis-Monthan from 1 September 1946 until 3 July 1949, when it was flown to Orchard Place Air Field, Park Ridge, Illinois

Park Ridge is a city in Cook County, Illinois, Cook County, Illinois, United States, and a Chicago suburb. Per the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 39,656. It is located northwest of downtown Chicago. It is close to O' ...

, by Tibbets for acceptance by the Smithsonian. It was moved to Pyote Air Force Base

Pyote Air Force Base was a World War II United States Army Air Forces training airbase. It was on a mile from the town of Pyote, Texas, on Interstate 20, 20 miles west of Monahans and just south of U.S. Highway 80, east of El Paso.

It was ...

, Texas, on 12 January 1952, and then to Andrews Air Force Base

Andrews Air Force Base (Andrews AFB, AAFB) is the airfield portion of Joint Base Andrews, which is under the jurisdiction of the United States Air Force. In 2009, Andrews Air Force Base merged with Naval Air Facility Washington to form Joint B ...

, Maryland, on 2 December 1953, because the Smithsonian had no storage space for the aircraft.

It was hoped that the Air Force would guard the plane, but, lacking hangar space, it was left outdoors on a remote part of the air base, exposed to the elements. Souvenir hunters broke in and removed parts. Insects and birds then gained access to the aircraft. Paul E. Garber of the Smithsonian Institution became concerned about the ''Enola Gay''s condition, and on 10 August 1960, Smithsonian staff began dismantling the aircraft. The components were transported to the Smithsonian storage facility at Suitland, Maryland

Suitland is an unincorporated community and census designated place (CDP) in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States, approximately one mile (1.6 km) southeast of Washington, D.C. As of the 2020 census, its population was 25,839. Prio ...

, on 21 July 1961.

''Enola Gay'' remained at Suitland for many years. By the early 1980s, two veterans of the 509th, Don Rehl and his former navigator in the 509th, Frank B. Stewart, began lobbying for the aircraft to be restored and put on display. They enlisted Tibbets and Senator Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for presiden ...

in their campaign. In 1983, Walter J. Boyne, a former B-52

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

pilot with the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

, became director of the National Air and Space Museum, and he made the ''Enola Gay''s restoration a priority. Looking at the aircraft, Tibbets recalled, was a "sad meeting. yfond memories, and I don't mean the dropping of the bomb, were the numerous occasions I flew the airplane ... I pushed it very, very hard and it never failed me ... It was probably the most beautiful piece of machinery that any pilot ever flew."

Restoration

Restoration of the bomber began on 5 December 1984, at thePaul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility

The Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility, also known colloquially as "Silver Hill", is a storage and former conservation and restoration facility of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, located in Suitland, Ma ...

in Suitland-Silver Hill, Maryland

Suitland-Silver Hill was a census-designated place (CDP) in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States, for the 2000 U.S. Census. The census area included the separate unincorporated communities of Silver Hill and Suitland, and other smaller ...

. The propellers that were used on the bombing mission were later shipped to Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public, land-grant, research university in College Station, Texas. It was founded in 1876 and became the flagship institution of the Texas A&M University System in 1948. As of late 2021, T ...

. One of these propellers was trimmed to for use in the university's Oran W. Nicks Low Speed Wind Tunnel. The lightweight aluminum variable-pitch propeller is powered by a 1,250 kVA electric motor, providing a wind speed up to . Two engines were rebuilt at Garber and two at San Diego Air & Space Museum

San Diego Air & Space Museum (SDASM, formerly the San Diego Aerospace Museum) is an aviation and space exploration museum in San Diego, California, United States. The museum is located in Balboa Park and is housed in the former Ford Building, ...

. Some parts and instruments had been removed and could not be located. Replacements were found or fabricated, and marked so that future curators could distinguish them from the original components.

Exhibition controversy

''Enola Gay'' became the center of a controversy at the Smithsonian Institution when the museum planned to put its fuselage on public display in 1995 as part of an exhibit commemorating the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit, ''The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War,'' was drafted by the Smithsonian's

''Enola Gay'' became the center of a controversy at the Smithsonian Institution when the museum planned to put its fuselage on public display in 1995 as part of an exhibit commemorating the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit, ''The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War,'' was drafted by the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, also called the Air and Space Museum, is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, it opened its main building on the Nat ...

staff, and arranged around the restored ''Enola Gay''.

Critics of the planned exhibit, especially those of the American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is a non-profit organization of U.S. war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militi ...

and the Air Force Association

The Air & Space Forces Association (AFA) is an independent, 501(c)(3) non-profit, professional military association for the United States Air Force and United States Space Force. Headquartered in Arlington, Virginia, its declared mission is ...

, charged that the exhibit focused too much attention on the Japanese casualties inflicted by the nuclear bomb, rather than on the motives for the bombing or the discussion of the bomb's role in ending the conflict with Japan. The exhibit brought to national attention many long-standing academic and political issues related to retrospective views of the bombings. After attempts to revise the exhibit to meet the satisfaction of competing interest groups, the exhibit was canceled on 30 January 1995. Martin O. Harwit, Director of the National Air and Space Museum, was compelled to resign over the controversy. He later reflected that

The forward fuselage went on display on 28 June 1995. On 2 July 1995, three people were arrested for throwing ash and human blood on the aircraft's fuselage, following an earlier incident in which a protester had thrown red paint over the gallery's carpeting. The exhibition closed on 18 May 1998 and the fuselage was returned to the Garber Facility for final restoration.

Complete restoration and display

Restoration work began in 1984, and eventually required 300,000 staff hours. While the fuselage was on display, from 1995 to 1998, work continued on the remaining unrestored components. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the National Air and Space Museum's

Restoration work began in 1984, and eventually required 300,000 staff hours. While the fuselage was on display, from 1995 to 1998, work continued on the remaining unrestored components. The aircraft was shipped in pieces to the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, also called the Udvar-Hazy Center, is the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM)'s annex at Washington Dulles International Airport in the Chantilly area of Fairfax County, Virginia. It holds numerous ...

in Chantilly, Virginia

Chantilly is a census-designated place (CDP) in western Fairfax County, Virginia. The population was 24,301 as of the 2020 census. Chantilly is named after an early-19th-century mansion and farm, which in turn took the name of an 18th-century p ...

from March–June 2003, with the fuselage and wings reunited for the first time since 1960 on 10 April 2003 and assembly completed on 8 August 2003. The aircraft has been on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center since the museum annex opened on 15 December 2003. As a result of the earlier controversy, the signage around the aircraft provided only the same succinct technical data as is provided for other aircraft in the museum, without discussion of the controversial issues. It read:

The display of the ''Enola Gay'' without reference to the historical context of World War II, the Cold War, or the development and deployment of nuclear weapons aroused controversy. A petition from a group calling themselves the Committee for a National Discussion of Nuclear History and Current Policy bemoaned the display of ''Enola Gay'' as a technological achievement, which it described as an "extraordinary callousness toward the victims, indifference to the deep divisions among American citizens about the propriety of these actions, and disregard for the feelings of most of the world's peoples". It attracted signatures from notable figures including historian

The display of the ''Enola Gay'' without reference to the historical context of World War II, the Cold War, or the development and deployment of nuclear weapons aroused controversy. A petition from a group calling themselves the Committee for a National Discussion of Nuclear History and Current Policy bemoaned the display of ''Enola Gay'' as a technological achievement, which it described as an "extraordinary callousness toward the victims, indifference to the deep divisions among American citizens about the propriety of these actions, and disregard for the feelings of most of the world's peoples". It attracted signatures from notable figures including historian Gar Alperovitz

Gar Alperovitz (born May 5, 1936) is an American historian and political economist. Alperovitz served as a fellow of King's College, Cambridge; a founding fellow of the Harvard Institute of Politics; a founding Fellow at the Institute for Policy ...

, social critic Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

, whistle blower Daniel Ellsberg

Daniel Ellsberg (born April 7, 1931) is an American political activist, and former United States military analyst. While employed by the RAND Corporation, Ellsberg precipitated a national political controversy in 1971 when he released the ''Pent ...

, physicist Joseph Rotblat

Sir Joseph Rotblat (4 November 1908 – 31 August 2005) was a Polish and British physicist. During World War II he worked on Tube Alloys and the Manhattan Project, but left the Los Alamos Laboratory on grounds of conscience after it became ...

, writer Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American writer known for his satirical and darkly humorous novels. In a career spanning over 50 years, he published fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and ...

, producer Norman Lear

Norman Milton Lear (born July 27, 1922) is an American producer and screenwriter, who has produced, written, created, or developed over 100 shows. Lear is known for many popular 1970s sitcoms, including the multi-award winning ''All in the Famil ...

, actor Martin Sheen

Ramón Antonio Gerardo Estévez (born August 3, 1940), known professionally as Martin Sheen, is an American actor. He first became known for his roles in the films ''The Subject Was Roses'' (1968) and ''Badlands'' (1973), and later achieved wid ...

and filmmaker Oliver Stone

William Oliver Stone (born September 15, 1946) is an American film director, producer, and screenwriter. Stone won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay as writer of '' Midnight Express'' (1978), and wrote the gangster film remake '' Sc ...

.

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Smithsonian's site on ''Enola Gay'' includes links to crew lists and other details

{{Portal bar, World War II Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Individual aircraft of World War II Individual aircraft in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution Boeing B-29 Superfortress