Elisha Gray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineer who co-founded the Western Electric Manufacturing Company. Gray is best known for his development of a telephone prototype in 1876 in Highland Park, Illinois. Some recent authors have argued that Gray should be considered the true inventor of the telephone because

In 1874, Gray retired to do independent research and development. Gray applied for a patent on a harmonic telegraph which consisted of multi-tone transmitters, that controlled each tone with a separate telegraph key. Gray gave several private demonstrations of this invention in New York and Washington, D.C. in May and June 1874.

Gray was a charter member of th

In 1874, Gray retired to do independent research and development. Gray applied for a patent on a harmonic telegraph which consisted of multi-tone transmitters, that controlled each tone with a separate telegraph key. Gray gave several private demonstrations of this invention in New York and Washington, D.C. in May and June 1874.

Gray was a charter member of th

Presbyterian Church in Highland Park, Illinois

At the church, on December 29, 1874, Gray gave the first public demonstration of his invention for transmitting musical tones and transmitted "familiar melodies through telegraph wire" according to a newspaper announcement. This was one of the earliest electric musical instruments using vibrating electromagnetic circuits that were single-note oscillators operated by a two-octave piano keyboard. The "Musical Telegraph" used steel reeds whose oscillations were created by electromagnets and transmitted over a telegraph wire. Gray also built a simple loudspeaker in later models consisting of a vibrating diaphragm in a magnetic field to make the oscillator tones audible and louder at the receiving end. In 1900 Gray worked on an underwater signaling device. After his death in 1901 officials gave the invention to Oberlin College. A few years later he was recognized as the inventor of the underwater signaling device. On July 27, 1875, Gray was granted for "Electric Telegraph for Transmitting Musical Tones" ( acoustic telegraphy). His experiments with transmitting musical tones went further, and on February 15, 1876 Elisha Grey was granted US Patent for electro-harmonic telegraph with piano keyboard. He was elected as a member to the

On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for

On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for  Bell's lawyer telegraphed Bell, who was still in Boston, to come to Washington, DC. When Bell arrived on February 26, Bell visited his lawyers and then visited examiner Wilber who told Bell that Gray's caveat showed a liquid transmitter and asked Bell for proof that the liquid transmitter idea (described in Bell's patent application as using mercury as the liquid) was invented by Bell. Bell pointed to an application of Bell's filed a year earlier where mercury was used in a circuit breaker. The examiner accepted this argument, although mercury would not have worked in a telephone transmitter. On February 29, Bell's lawyer submitted an amendment to Bell's claims that distinguished them from Gray's caveat and Gray's earlier application. On March 3, Wilber approved Bell's application and on March 7, 1876, 174,465 was published by the

Bell's lawyer telegraphed Bell, who was still in Boston, to come to Washington, DC. When Bell arrived on February 26, Bell visited his lawyers and then visited examiner Wilber who told Bell that Gray's caveat showed a liquid transmitter and asked Bell for proof that the liquid transmitter idea (described in Bell's patent application as using mercury as the liquid) was invented by Bell. Bell pointed to an application of Bell's filed a year earlier where mercury was used in a circuit breaker. The examiner accepted this argument, although mercury would not have worked in a telephone transmitter. On February 29, Bell's lawyer submitted an amendment to Bell's claims that distinguished them from Gray's caveat and Gray's earlier application. On March 3, Wilber approved Bell's application and on March 7, 1876, 174,465 was published by the

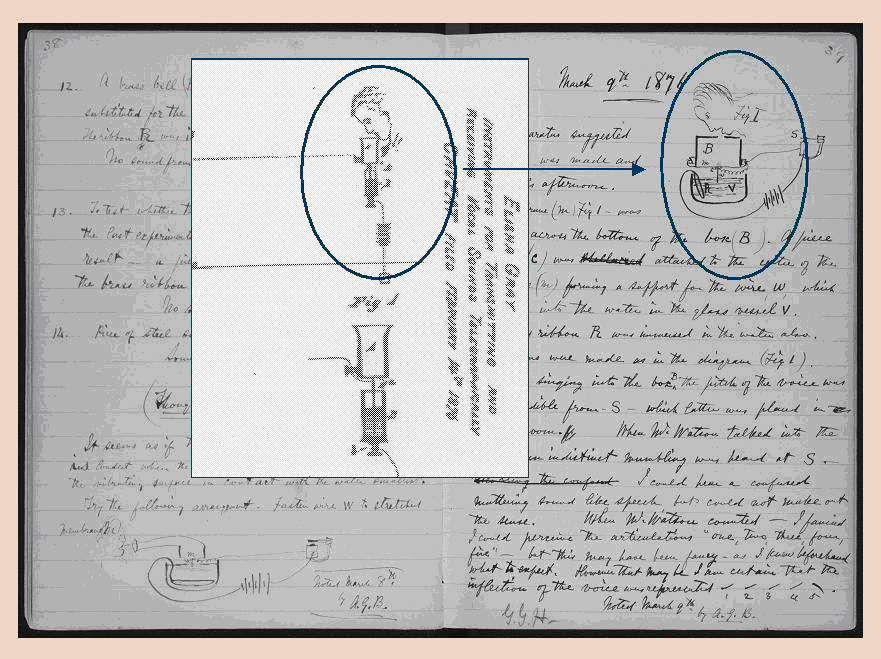

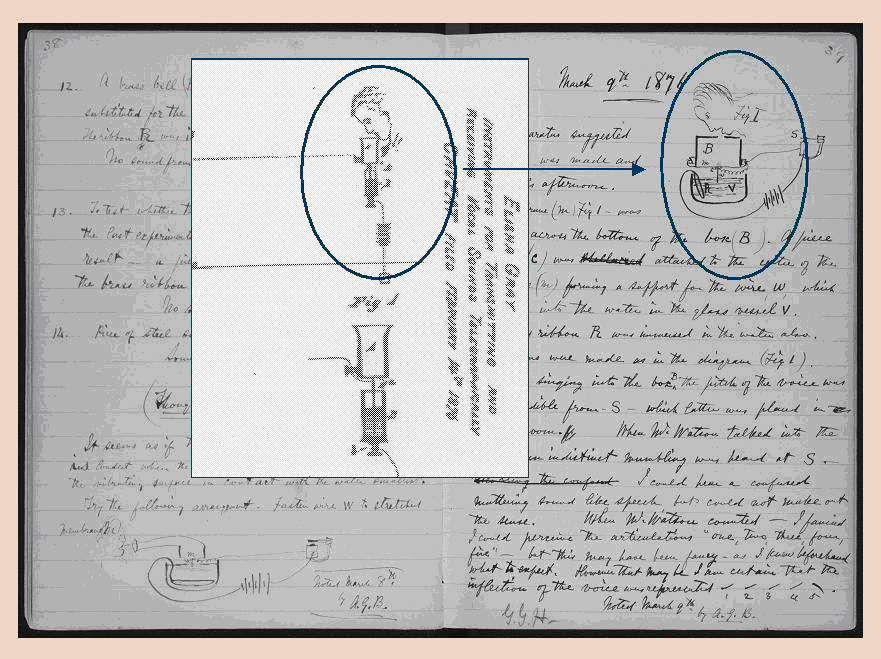

Gray's telephone caveat

filed on February 14, 1876 same day as Bell's application

with drawings, filed on February 14, 1876

Gray's "Musical Telegraph"

of 1876

* over the harmonic telegraph

description

in Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago

The Musical Telegraph

Elisha Grey's The Musical Telegraph on '120 Years of Electronic Music' {{DEFAULTSORT:Gray, Elisha 1835 births 1901 deaths 19th-century American inventors American Quakers Burials at Rosehill Cemetery Discovery and invention controversies Oberlin College alumni Oberlin College faculty People from Barnesville, Ohio Businesspeople from Boston People from Highland Park, Illinois 19th-century American businesspeople

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and T ...

allegedly stole the idea of the liquid transmitter from him. Although Gray had been using liquid transmitters in his telephone experiments for more than two years previously, Bell's telephone patent was upheld in numerous court decisions.

Gray is also considered to be the father of the modern music synthesizer, and was granted over 70 patents for his inventions. He was one of the founders of Graybar, purchasing a controlling interest in the company shortly after its inception.

Biography and early inventions

Gray was born in Barnesville, Ohio, the son of Christiana (Edgerton) and David Gray. His family were Quakers. He was brought up on a farm. He spent several years at Oberlin College where he experimented with electrical devices. Although Gray did not graduate, he taught electricity and science there and built laboratory equipment for its science departments. In 1862, while at Oberlin, Gray met and married Delia Minerva Shepard. In 1865, Gray invented a self-adjustingtelegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

relay that automatically adapted to varying insulation of the telegraph line. In 1867 Gray received a patent for the invention, the first of more than seventy.

In 1869, Elisha Gray and his partner Enos M. Barton founded Gray & Barton Co. in Cleveland, Ohio to supply telegraph equipment to the giant Western Union Telegraph Company. The electrical distribution business was later spun off and organized into a separate company, Graybar Electric Company, Inc. Barton was employed by Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company cha ...

to examine and test new products.

In 1870, financing for Gray & Barton Co. was arranged by General Anson Stager, a superintendent of the Western Union Telegraph Company. Stager became an active partner in Gray & Barton Co. and remained on the board of directors. The company moved to Chicago near Highland Park. Gray later gave up his administrative position as chief engineer to focus on inventions that could benefit the telegraph industry. Gray's inventions and patent costs were financed by a dentist, Dr. Samuel S. White of Philadelphia, who had made a fortune producing porcelain teeth. White wanted Gray to focus on the acoustic telegraph which promised huge profits instead of what appeared to be unpromising competing inventions such as the telephone. White made the decision in 1876 to redirect Gray's interest in the telephone.

In 1870, Gray developed a needle annunciator for hotels and another for elevators. He also developed a microphone printer which had a typewriter keyboard and printed messages on paper tape.

In 1871 Great Chicago Fire destroyed the city and it's telegraph infrastructure, Gray & Barton was hired to rebuild it. In 1872, Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company cha ...

, then financed by the Vanderbilts and J. P. Morgan, bought one-third of Gray and Barton Co. and changed the name to Western Electric Manufacturing Company of Chicago. Gray continued to invent for Western Electric.

In 1874, Gray retired to do independent research and development. Gray applied for a patent on a harmonic telegraph which consisted of multi-tone transmitters, that controlled each tone with a separate telegraph key. Gray gave several private demonstrations of this invention in New York and Washington, D.C. in May and June 1874.

Gray was a charter member of th

In 1874, Gray retired to do independent research and development. Gray applied for a patent on a harmonic telegraph which consisted of multi-tone transmitters, that controlled each tone with a separate telegraph key. Gray gave several private demonstrations of this invention in New York and Washington, D.C. in May and June 1874.

Gray was a charter member of thPresbyterian Church in Highland Park, Illinois

At the church, on December 29, 1874, Gray gave the first public demonstration of his invention for transmitting musical tones and transmitted "familiar melodies through telegraph wire" according to a newspaper announcement. This was one of the earliest electric musical instruments using vibrating electromagnetic circuits that were single-note oscillators operated by a two-octave piano keyboard. The "Musical Telegraph" used steel reeds whose oscillations were created by electromagnets and transmitted over a telegraph wire. Gray also built a simple loudspeaker in later models consisting of a vibrating diaphragm in a magnetic field to make the oscillator tones audible and louder at the receiving end. In 1900 Gray worked on an underwater signaling device. After his death in 1901 officials gave the invention to Oberlin College. A few years later he was recognized as the inventor of the underwater signaling device. On July 27, 1875, Gray was granted for "Electric Telegraph for Transmitting Musical Tones" ( acoustic telegraphy). His experiments with transmitting musical tones went further, and on February 15, 1876 Elisha Grey was granted US Patent for electro-harmonic telegraph with piano keyboard. He was elected as a member to the

American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1878.

Telephone

Because of Samuel White's opposition to Gray working on the telephone, Gray did not tell anybody about his invention for transmitting voice sounds until February 11, 1876 (Friday). The only remaining proof is a drawing he made on that day. Gray requested that his patent lawyer William D. Baldwin prepare a "caveat" for filing at the US Patent Office. A caveat was like a provisional patent application with drawings and description but without a request for examination.

On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for

On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and T ...

submitted Bell's patent application. Which application arrived first is hotly disputed, although Gray believed that his caveat arrived a few hours ''before'' Bell's application. Bell's lawyers in Washington, DC, had been waiting with Bell's patent application for months, under instructions not to file it in the USA until it had been filed in Britain first. (At the time, Britain would only issue patents on discoveries not previously patented elsewhere.)

According to Evenson, during the weekend of February 12–14, 1876, before either caveat or application had been filed in the patent office, Bell's lawyer learned about the liquid transmitter idea in Gray's caveat that would be filed early Monday morning February 14. Bell's lawyer then added seven sentences describing the liquid transmitter and a variable resistance claim to Bell's draft application. After the lawyer's clerk recopied the draft as a finished patent application, Bell's lawyer hand-delivered the finished application to the patent office just before noon Monday, a few hours after Gray's caveat was delivered by Gray's lawyer. Bell's lawyer requested that Bell's application be immediately recorded and hand-delivered to the examiner on Monday so that later Bell could claim it had arrived first. Bell was in Boston at this time and was not aware that his application had been filed.

Five days later, on February 19, Zenas Fisk Wilber, the patent examiner for both Bell's application and Gray's caveat, noticed that Bell's application claimed the same variable resistance feature described in Gray's caveat. Wilber suspended Bell's application for 90 days to give Gray time to submit a competing patent application. The suspension also gave Bell time to amend his claims to avoid an interference with an earlier patent application of Gray's that mentioned changing the intensity of the electric current without breaking the circuit, which seemed to the examiner to be an "undulatory current" that Bell was claiming. Such an interference would delay Bell's application until Bell submitted proof, under the first to invent rules, that Bell had invented that feature before Gray.

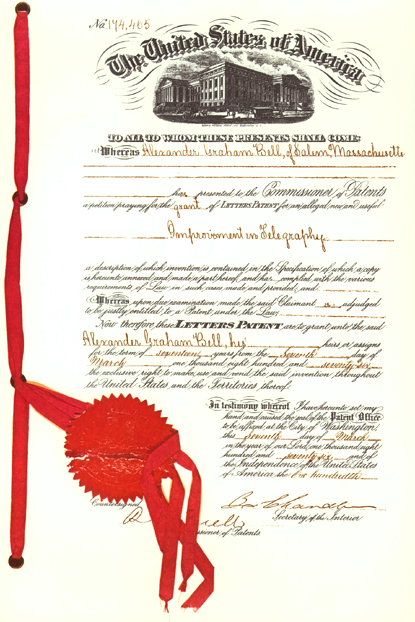

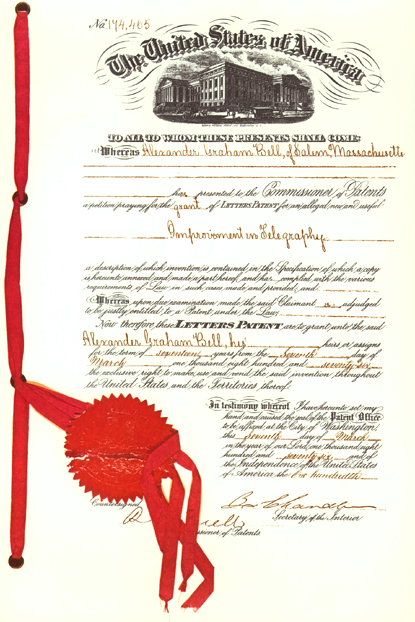

Bell's lawyer telegraphed Bell, who was still in Boston, to come to Washington, DC. When Bell arrived on February 26, Bell visited his lawyers and then visited examiner Wilber who told Bell that Gray's caveat showed a liquid transmitter and asked Bell for proof that the liquid transmitter idea (described in Bell's patent application as using mercury as the liquid) was invented by Bell. Bell pointed to an application of Bell's filed a year earlier where mercury was used in a circuit breaker. The examiner accepted this argument, although mercury would not have worked in a telephone transmitter. On February 29, Bell's lawyer submitted an amendment to Bell's claims that distinguished them from Gray's caveat and Gray's earlier application. On March 3, Wilber approved Bell's application and on March 7, 1876, 174,465 was published by the

Bell's lawyer telegraphed Bell, who was still in Boston, to come to Washington, DC. When Bell arrived on February 26, Bell visited his lawyers and then visited examiner Wilber who told Bell that Gray's caveat showed a liquid transmitter and asked Bell for proof that the liquid transmitter idea (described in Bell's patent application as using mercury as the liquid) was invented by Bell. Bell pointed to an application of Bell's filed a year earlier where mercury was used in a circuit breaker. The examiner accepted this argument, although mercury would not have worked in a telephone transmitter. On February 29, Bell's lawyer submitted an amendment to Bell's claims that distinguished them from Gray's caveat and Gray's earlier application. On March 3, Wilber approved Bell's application and on March 7, 1876, 174,465 was published by the U.S. Patent Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alexa ...

.

Bell returned to Boston and resumed work on March 9, drawing a diagram in his lab notebook of a water transmitter being used face down, very similar to that shown in Gray's caveat. Bell and Watson built and tested a liquid transmitter design on March 10 and successfully transmitted clear speech saying "Mr. Watson – come here – I want to see you." Bell's notebooks became public when they were donated to the Library of Congress in 1976.

Although Bell has been accused of stealing the telephone from Gray because his liquid transmitter design resembled Gray's, documents in the Library of Congress indicate that Bell had been using liquid transmitters extensively for three years in his multiple telegraph and other experiments. In April, 1875, ten months before the alleged theft of Gray's design, the U.S. Patent Office granted 161,739 to Bell for a primitive fax machine, which he called the "autograph telegraph." The patent drawing includes liquid transmitters.

After March 1876, Bell and Watson focused on improving the electromagnetic telephone and never used Gray's liquid transmitter in public demonstrations or commercial use.

Although Gray had abandoned his caveat, Gray applied for a patent for the same invention in late 1877. This put him in a second interference with Bell's patents. The Patent Office determined, "while Gray was undoubtedly the first to conceive of and disclose the ariable resistanceinvention, as in his caveat of February 14, 1876, his failure to take any action amounting to completion until others had demonstrated the utility of the invention deprives him of the right to have it considered." Gray challenged Bell's patent anyway, and after two years of litigation, Bell was awarded rights to the invention, and as a result, Bell is credited as the inventor.

In 1886, Wilber stated in an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a stateme ...

that he was an alcoholic and deeply in debt to Bell's lawyer Marcellus Bailey

Marcellus Bailey (1840 – January 16, 1921) was an American patent attorney who, with Anthony Pollok, helped prepare Alexander Graham Bell's patents for the telephone and related inventions.

Biography

The son of abolitionist and '' National ...

with whom Wilber had served in the Civil War. Wilber stated that, contrary to Patent Office rules, he showed Bailey the caveat Gray had filed. He also stated that he showed the caveat to Bell and Bell gave him $100. Bell testified that they only discussed the patent in general terms, although in a letter to Gray, Bell admitted that he learned some of the technical details. Wilbur's affidavit contradicted his earlier testimony, and historians have pointed out that his last affidavit was drafted for him by the attorneys for the Pan-Electric Company which was attempting to steal the Bell patents and was later discovered to have bribed the U.S. Attorney General Augustus Garland and several Congressmen.

Bell's patent was disputed in 1888 by attorney Lysander Hill who accused Wilber of allowing Bell or his lawyer Pollok to add a handwritten margin note of seven sentences to Bell's application that describe an alternate design similar to Gray's liquid microphone design. However, the marginal note was added only to Bell's earlier draft, not to his patent application that shows the seven sentences already present in a paragraph. Bell testified that he added those seven sentences in the margin of an earlier draft of his application "almost at the last moment before sending it off to Washington" to his lawyers. Bell or his lawyer could not have added the seven sentences to the application after it was filed in the Patent Office, because then the application would not have been suspended.

Further inventions

In 1887, Gray invented the telautograph, a device that could remotely transmit handwriting through telegraph systems. Gray was granted several patents for these pioneer fax machines, and the Gray National Telautograph Company was chartered in 1888 and continued in business as The Telautograph Corporation for many years; after a series of mergers it was finally absorbed byXerox

Xerox Holdings Corporation (; also known simply as Xerox) is an American corporation that sells print and digital document products and services in more than 160 countries. Xerox is headquartered in Norwalk, Connecticut (having moved from St ...

in the 1990s. Gray's telautograph machines were used by banks for signing documents at a distance and by the military for sending written commands during gun tests when the deafening noise from the guns made spoken orders on the telephone impractical. The machines were also used at train stations for schedule changes.

Gray displayed his telautograph invention in 1893 at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and sold his share in the telautograph shortly after that. Gray was also chairman of the International Congress of Electricians at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Gray conceived of a primitive closed-circuit television

Closed-circuit television (CCTV), also known as video surveillance, is the use of video cameras to transmit a signal to a specific place, on a limited set of monitors. It differs from broadcast television in that the signal is not openly tr ...

system that he called the "telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

". Pictures would be focused on an array of selenium cells and signals from the selenium cells would be transmitted to a distant station on separate wires. At the receiving end, each wire would open or close a shutter to recreate the image.

In 1899, Gray moved to Boston where he continued inventing. One of his projects was to develop an underwater signaling device to transmit messages to ships. One such signaling device was tested on December 31, 1900. Three weeks later, on January 21, 1901, Gray died from a heart attack in Newtonville, Massachusetts.

Some modern authors incorrectly attribute the Gray code to Elisha Gray, whereas it was named after Frank Gray.

Publications

Gray wrote several books including: *''Experimental Researches in Electro-Harmonic Telegraphy and Telephony, 1867–1876'' (Appleton, 1878) *''Telegraphy and Telephony'' (1878) *''Electricity and Magnetism'' (1900) and *''Nature's Miracles'' (1900) a nontechnical discussion of science and technology for the general public.See also

* Invention of the telephone * Timeline of the telephone * The Telephone Cases *Water microphone A water microphone or water transmitter is based on Ohm's law that current in a wire varies inversely with the resistance of the circuit. The sound waves from a human voice cause a diaphragm to vibrate which causes a needle or rod to vibrate up and ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * Dr. Lloyd W. Taylor, an Oberlin physics department head, began writing a Gray biography, but the book was never finished because of Taylor's accidental death in July 1948. Dr Taylor's unfinished manuscript is in the College Archives at Oberlin College.External links

* * * *Gray's telephone caveat

filed on February 14, 1876 same day as Bell's application

with drawings, filed on February 14, 1876

Gray's "Musical Telegraph"

of 1876

* over the harmonic telegraph

description

in Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago

The Musical Telegraph

Elisha Grey's The Musical Telegraph on '120 Years of Electronic Music' {{DEFAULTSORT:Gray, Elisha 1835 births 1901 deaths 19th-century American inventors American Quakers Burials at Rosehill Cemetery Discovery and invention controversies Oberlin College alumni Oberlin College faculty People from Barnesville, Ohio Businesspeople from Boston People from Highland Park, Illinois 19th-century American businesspeople