Egypt under Muhammad Ali on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Acknowledging the sovereignty of the Ottoman Sultan, and at the commands of the

Acknowledging the sovereignty of the Ottoman Sultan, and at the commands of the

The reign of Ismail, from 1863 to 1879, was initially hailed as a new era of bringing Egypt into modernity. He completed vast development schemes and attempted positive administrative reforms, but this progress, coupled with his personal extravagance led to

The reign of Ismail, from 1863 to 1879, was initially hailed as a new era of bringing Egypt into modernity. He completed vast development schemes and attempted positive administrative reforms, but this progress, coupled with his personal extravagance led to

Egyptian Royalty

— by Ahmed S. Kamel, Hassan Kamel Kelisli-Morali, Georges Soliman and Magda Malek

L'Egypte D'Antan... Egypt in Bygone Days

— by Max Karkegi

Early Photos: Egypt in the 1800s

— slideshow by

Collection: Egypt in the 19th Century Photography

from the

online

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Egypt Under The Muhammad Ali Dynasty Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty + + Egyptian families Egyptian pashas Egyptian nobility 19th century in Egypt 20th century in Egypt

history of Egypt

The history of Egypt has been long and wealthy, due to the flow of the Nile River with its fertile banks and delta, as well as the accomplishments of Egypt's native inhabitants and outside influence. Much of Egypt's ancient history was a myste ...

under the Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

dynasty (1805–1953) spanned the later period of Ottoman Egypt

The Eyalet of Egypt (, ) operated as an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 to 1867. It originated as a result of the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by the Ottomans in 1517, following the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–17) and the ...

, the Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which br ...

under British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

occupation, and the nominally independent Sultanate of Egypt

The Sultanate of Egypt () was the short-lived protectorate that the United Kingdom imposed over Egypt between 1914 and 1922.

History

Soon after the start of the First World War, Khedive Abbas II of Egypt was removed from power by the British ...

and Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt ( ar, المملكة المصرية, Al-Mamlaka Al-Miṣreyya, The Egyptian Kingdom) was the legal form of the Egyptian state during the latter period of the Muhammad Ali dynasty's reign, from the United Kingdom's recog ...

, ending with the Revolution of 1952 and the formation of the Republic of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

.

Muhammad Ali's rise to power

The process of Muhammad Ali's seizure of power was a long three way civil war between the Ottoman Turks, EgyptianMamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s, and Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

n mercenaries. It lasted from 1803 to 1807 with the Albanian Muhammad Ali Pasha taking control of Egypt in 1805, when the Ottoman Sultan acknowledged his position. Thereafter, Muhammad Ali was the undisputed master of Egypt, and his efforts henceforth were directed primarily to the maintenance of his practical independence.

Egypt under Muhammad Ali

Campaign against the Saudis

The Ottoman-Saudi war in 1811–18 was fought betweenEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

under the reign of Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

(nominally under Ottoman rule) and the Wahabbis of Najd

Najd ( ar, نَجْدٌ, ), or the Nejd, forms the geographic center of Saudi Arabia, accounting for about a third of the country's modern population and, since the Emirate of Diriyah, acting as the base for all unification campaigns by the ...

who had conquered Hejaz from the Ottomans.

When Wahabis captured Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

in 1802, the Ottoman sultan ordered Muhammad Ali of Egypt to start moving against Wahabbis to re-conquer Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

and return the honour of the Ottoman Empire.

First Arabian campaign

Acknowledging the sovereignty of the Ottoman Sultan, and at the commands of the

Acknowledging the sovereignty of the Ottoman Sultan, and at the commands of the Ottoman Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

, in 1811 Muhammad Ali dispatched an army of 20,000 men (and 2,000 horses) under the command of his son Tusun, a youth of sixteen, against the Saudis in the Ottoman–Saudi War

The Ottoman-Saudi War ( ar, الحرب العثمانية-السعودية, translit=al-ḥarb al-ʿUthmānīyah-al-Saʿūdīyah, ) also known as the Ottoman/Egyptian-Saudi War (1811–1818) was fought from early 1811 to 1818, between the Ot ...

. After a successful advance this force met with a serious repulse at the Battle of Al-Safra

The Battle of Al-Safra, took place in 1812 when Tusun Pasha's forces with its artillery and equipment moved forward trying to recapture Medina and met with Saud Al-Kabeer forces in a Valley of Al-Safra (the yellow Valley). Saud's army started a ...

, and retreated to Yanbu

Yanbu ( ar, ينبع, lit=Spring, translit=Yanbu'), also known simply as Yambu or Yenbo, is a city in the Al Madinah Province of western Saudi Arabia. It is approximately 300 kilometers northwest of Jeddah (at ). The population is 222,360 (2 ...

. In the end of the year Tusun, having received reinforcements, again assumed the offensive and captured Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

after a prolonged siege. He next took Jeddah

Jeddah ( ), also spelled Jedda, Jiddah or Jidda ( ; ar, , Jidda, ), is a city in the Hejaz region of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and the country's commercial center. Established in the 6th century BC as a fishing village, Jeddah's pro ...

and Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

, defeating the Saudi beyond the latter and capturing their general.

But some mishaps followed, and Muhammad Ali, who had determined to conduct the war in person, left Egypt in the summer of 1813—leaving his other son Ibrahim

Ibrahim ( ar, إبراهيم, links=no ') is the Arabic name for Abraham, a Biblical patriarch and prophet in Islam.

For the Islamic view of Ibrahim, see Abraham in Islam.

Ibrahim may also refer to:

* Ibrahim (name), a name (and list of people w ...

in charge of the country. He encountered serious obstacles in Arabia, predominantly stemming from the nature of the country and the harassing mode of warfare adopted by his adversaries, but on the whole his forces proved superior to those of the enemy. He deposed and exiled the Sharif of Mecca and after the death of the Saudi leader Saud he concluded a treaty with Saud's son and successor, Abdullah I in 1815.

Following reports that the Turks, whose cause he was upholding in Arabia, were treacherously planning an invasion of Egypt, and hearing of the escape of Napoleon from Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano Nationa ...

and fearing danger to Egypt from France or Britain, Muhammad Ali returned to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

by way of Kosseir and Kena, reaching the capital on the day of the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

.

Second Arabian campaign

Tusun returned to Egypt on hearing of the military revolt atCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, but died in 1816 at the early age of twenty. Muhammad Ali, dissatisfied with the treaty concluded with the Saudis, and with the non-fulfillment of certain of its clauses, determined to send another army to Arabia, and to include in it the soldiers who had recently proved unruly.

This expedition, under his eldest son Ibrahim Pasha, left in the autumn of 1816. The war was long and arduous but in 1818 Ibrahim captured the Saudi capital of Diriyah

Diriyah ( ar, الدِرْعِيّة), formerly romanized as Dereyeh and Dariyya), is a town in Saudi Arabia located on the north-western outskirts of the Saudi capital, Riyadh. Diriyah was the original home of the Saudi royal family, and served ...

. Abdullah I, their chief, was made prisoner and with his treasurer and secretary was sent to Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

(in some references he was sent to Cairo), where, in spite of Ibrahim's promise of safety and of Muhammad Ali's intercession in their favor, they were put to death. At the close of the year 1819 Ibrahim returned having subdued all opposition in Arabia.

Reforms

While the process had begun in 1808, Muhammad Ali's representative at Cairo had completed the confiscation of almost all the lands belonging to private individuals, while he was absent in Arabia (1813–15). The former owners were forced to accept inadequate pensions instead. By this revolutionary method of land nationalization Muhammad Ali became proprietor of nearly all the soil of Egypt. During Ibrahim's engagement in the second Arabian campaign, the pasha turned his attention to further strengthening the Egyptian economy, and his control over it. He created state monopolies for the chief products of the country, and created a number of factories. In 1819 he began digging the new Mahmoudiyah Canal to Alexandria, named after the reigning Sultan of Turkey. The old canal had long fallen into decay, and the necessity of providing a safe channel between Alexandria and theNile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

was much felt. The conclusion of the commercial Treaty of Balta Liman

The 1838 Treaty of Balta Liman, or the Anglo-Ottoman Treaty, is a formal trade agreement signed between the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain. The trade policies imposed upon the Ottoman Empire, after the Treaty of Balta Lima ...

in 1838 between Turkey and Britain, negotiated by Sir Henry Bulwer (Lord Darling), struck the death knell to the system of monopolies, though its application regarding Egypt was delayed for some years, and finally included foreign intervention.

Another notable addition to the economic progress of the country was the development of cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

cultivation in the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

starting in 1822. The cotton seed for the new crop had been brought from the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

by Maho Bey Maho may refer to:

Term

* Maho, tropical hibiscus tree common throughout the Caribbean (thespesia populnea, Hibiscus elatus, or Hibiscus Tilaceus)

* Maho, a West Indian Caribbean slang term for a man who spends too much time drinking beer and fishi ...

, and with the organization of the new irrigation and industry, Muhammad Ali was able to extract considerable revenue in a few years time.

Other domestic efforts were made to promote education and the study of medicine. Muhammad Ali showed much favor, to European merchants, on whom he was dependent for the sale of his monopoly exports, and under his influence the port of Alexandria again rose into importance. It was also under Muhammad Ali's encouragement that the overland transit of goods from Europe to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

via Egypt was resumed.

The Pasha also attempted to reorganize his troops along European lines, but this led to a formidable mutiny in Cairo. Muhammad Ali's life was endangered, and he sought refuge by night in the citadel, while the soldiers committed many acts of plunder. The effects of the revolt were reduced by gifts to the insurgent's leaders; Muhammad Ali also ordered that those who suffered from the disturbances should receive compensation from the state treasury. The conscription portion of the Nizam-ı Cedid

The Nizam-i Cedid ( ota, نظام جديد, Niẓām-ı Cedīd, lit=new order) was a series of reforms carried out by Ottoman Sultan Selim III during the late 18th and the early 19th centuries in a drive to catch up militarily and politically wi ...

(New System) was temporarily abandoned, as consequence of this mutiny.

Economy

Egypt under Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century had the fifth most productive cotton industry in the world, in terms of the number of spindles per capita. The industry was initially driven by machinery that relied on traditional energy sources, such asanimal power

A working animal is an animal, usually domesticated, that is kept by humans and trained to perform tasks instead of being slaughtered to harvest animal products. Some are used for their physical strength (e.g. oxen and draft horses) or for t ...

, water wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

s, and windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

s, which were also the principle energy sources in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

up until around 1870. While steam power

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be tra ...

had been experimented with in Ottoman Egypt by engineer Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf

Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf ash-Shami al-Asadi ( ar, تقي الدين محمد بن معروف الشامي; ota, تقي الدين محمد بن معروف الشامي السعدي; tr, Takiyüddin 1526–1585) was an Ottoman poly ...

in 1551, when he invented a steam jack driven by a rudimentary steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

, it was under Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century that steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

s were introduced to Egyptian industrial manufacturing. While there was a lack of coal deposits in Egypt, prospectors searched for coal deposits there, and manufactured boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central ...

s which were installed in Egyptian industries such as ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloomer ...

, textile manufacturing

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

, paper mill

A paper mill is a factory devoted to making paper from vegetable fibres such as wood pulp, old rags, and other ingredients. Prior to the invention and adoption of the Fourdrinier machine and other types of paper machine that use an endless belt ...

s and hulling

Husk (or hull) in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. In the United States, the term husk often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize (corn) as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protect ...

mills. Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

was also imported from overseas, at similar prices to what imported coal cost in France, until the 1830s, when Egypt gained access to coal sources in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus lie ...

, which had a yearly coal output of 4,000 tons. Compared to Western Europe, Egypt also had superior agriculture and an efficient transport network through the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

. Economic historian Jean Batou argues that the necessary economic conditions for rapid industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

existed in Egypt during the 1820s–1830s, as well as for the adoption of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

as a potential energy source for its steam engines later in the 19th century.

Invasion of Libya and Sudan

In 1820 Muhammad Ali gave orders to commence the conquest of easternLibya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

. He first sent an expedition westward (Feb. 1820) which conquered and annexed the Siwa oasis

The Siwa Oasis ( ar, واحة سيوة, ''Wāḥat Sīwah,'' ) is an urban oasis in Egypt; between the Qattara Depression and the Great Sand Sea in the Western Desert, 50 km (30 mi) east of the Libyan border, and 560 km (348&nbs ...

. Ali's intentions for Sudan was to extend his rule southward, to capture the valuable caravan trade bound for the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

, and to secure the rich gold mines which he believed to exist in Sennar

Sennar ( ar, سنار ') is a city on the Blue Nile in Sudan and possibly the capital of the state of Sennar. It remains publicly unclear whether Sennar or Singa is the capital of Sennar State. For several centuries it was the capital of the ...

. He also saw in the campaign a means of getting rid of his disaffected troops, and of obtaining a sufficient number of captives to form the nucleus of the new army.

The forces destined for this service were led by Ismail, his youngest son. They consisted of between 4000 and 5000 men, being Turks and Arabs. They left Cairo in July 1820. Nubia

Nubia () ( Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sud ...

at once submitted, the Shaigiya tribe

The Shaigiya, Shaiqiya, Shawayga or Shaykia () are an Arab or Arabised Nubian tribe. They are part of the Sudanese Arabs and are also one of the three prominent Sudanese Arabs tribes in North Sudan, along with the Ja'alin and Danagla. The tribe ...

immediately beyond the province of Dongola were defeated, the remnant of the Mamluks dispersed, and Sennar was reduced without a battle.

Mahommed Bey, the defterdar This is a list of the top officials in charge of the finances of the Ottoman Empire, called ( Turkish for bookkeepers; from the Persian , + ) between the 14th and 19th centuries and ''Maliye Naziri'' (Minister of Finance) between 19th and 20th ...

, with another force of about the same strength, was then sent by Muhammad Ali against Kordofan

Kordofan ( ar, كردفان ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory ...

with like result, but not without a hard-fought engagement. In October 1822, Ismail, with his retinue, was burnt to death by Nimr, the mek (king) of Shendi

Shendi or Shandi ( ar, شندي) is a small city in northern Sudan, situated on the southeastern bank of the Nile River 150 km northeast of Khartoum. Shandi is also about 45 km southwest of the ancient city of Meroë. Located in the ...

; following this incident the defterdar, a man infamous for his cruelty, assumed the command of those provinces, and exacted terrible retribution from the inhabitants. Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

was founded at this time, and in the following years the rule of the Egyptians was greatly extended and control of the Red Sea ports of Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

and Massawa

Massawa ( ; ti, ምጽዋዕ, məṣṣəwaʿ; gez, ምጽዋ; ar, مصوع; it, Massaua; pt, Maçuá) is a port city in the Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahla ...

obtained.

Ahmad Revolt

In 1824 a native rebellion broke out in Upper Egypt headed by one Ahmad, an inhabitant of al-Salimiyyah, a village situated a few miles above Thebes. He proclaimed himself a prophet, and was soon followed by between 20,000 and 30,000 insurgents, mostly peasants, but some of them deserters from the Nizam Gedid, for that force was yet in a half-organized state. The peasants were angered by many of Ali's reforms, especially the introduction ofconscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

and the increase in taxes and forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

.

The insurrection was crushed by Muhammad Ali, and about one fourth of Ahmad's followers perished, but he himself escaped and was never heard of again. Few of these unfortunates possessed any other weapon than the long staff (''nabbut'') of the Egyptian peasant; still they offered an obstinate resistance, and the combat in which they were defeated resembled a massacre. This movement was the last internal attempt to destroy the pasha's authority.

The subsequent years saw an imposition of order across Egypt and Ali's new highly trained and disciplined forces spread across the nation. Public order was rendered perfect; the Nile and the highways were secure to all travelers, Christian or Muslim; the Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

tribes were won over to peaceful pursuits.

Greek campaign

Muhammad Ali was fully conscious that the empire which he had so laboriously built up might at any time have to be defended by force of arms against his master SultanMahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

, whose whole policy had been directed to curbing the power of his too ambitious vassals, and who was under the influence of the personal enemies of the pasha of Egypt, notably of Hüsrev Pasha, the Grand Vizier

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first ...

, who had never forgiven his humiliation in Egypt in 1803.

Mahmud also was already planning reforms borrowed from the West, and Muhammad Ali, who had plenty of opportunity of observing the superiority of European methods of warfare, was determined to anticipate the sultan in the creation of a fleet and an army on European lines, partly as a measure of precaution, partly as an instrument for the realization of yet wider schemes of ambition. Before the outbreak of the War of Greek Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

in 1821, he had already expended much time and energy in organizing a fleet and in training, under the supervision of French instructors, native officers and artificers; though it was not till 1829 that the opening of a dockyard and arsenal at Alexandria enabled him to build and equip his own vessels. By 1823, moreover, he had succeeded in carrying out the reorganization of his army on European lines, the turbulent Turkish and Albanian elements being replaced by Sudanese and ''fellah

A fellah ( ar, فَلَّاح ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller". ...

in''. The effectiveness of the new force was demonstrated in the suppression of an 1823 revolt of the Albanians in Cairo by six disciplined Sudanese regiments; after which Mehemet Ali was no more troubled with military mutinies.

His foresight was rewarded by the invitation of the sultan to help him in the task of subduing the Greek insurgents, offering as reward the pashaliks of the Morea

The Morea ( el, Μορέας or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used for the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the Ottom ...

and of Syria. Mehemet Ali had already, in 1821, been appointed by him governor of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, which he had occupied with a small Egyptian force. In the autumn of 1824 a fleet of 60 Egyptian warships carrying a large force of 17,000 disciplined troops concentrated in Suda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akrotiri ...

, and, in the following March, with Ibrahin as commander-in-chief landed in the Morea

The Morea ( el, Μορέας or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used for the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the Ottom ...

.

His naval superiority wrested from the Greeks the command of a great deal of the sea, on which the fate of the insurrection ultimately depended, while on land the Greek irregular bands, having largely soundly beaten the Porte's troops, had finally met a worthy foe in Ibrahim's disciplined troops. The history of the events that led up to the battle of Navarino

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O. S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–29), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied f ...

and the liberation of Greece is told elsewhere; the withdrawal of the Egyptians from the Morea was ultimately due to the action of Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, who early in August 1828 appeared before Alexandria and induced the pasha, by no means sorry to have a reasonable excuse, by a threat of bombardment, to sign a convention undertaking to recall Ibrahim and his army. But for the action of European powers, it is suspected by many that the Ottoman Empire might have defeated the Greeks.

War with the Sultan

Ali went to war against the sultan on in order to obtain raw materials lacking in Egypt (especially timber for his navy) and a captive market for Egypt's new industrial output. From fall 1831 to December 1832 Ibrahim led the Egyptian army through Lebanon and Syria and across the Taurus Mountains into Anatolia where he defeated the Ottoman forces and pushed on to Kutahya, only 150 miles from Istanbul. For the next ten years relations between the Sultan and the Pasha remained in the forefront of the questions which agitated the diplomatic world. It was not only the very existence of the Ottoman empire that seemed to be at stake, but Egypt itself had become more than ever the object of international attention, to British statesmen especially, and in the issue of the struggle were involved the interests of Britain in the two routes to India by the Isthmus of Suez and the valley of theEuphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

. Ibrahim, who once more commanded in his father's name, launched another brilliant campaign beginning with the storming of Acre on May 27, 1832, and culminating in the rout and capture of Reshid Pasha at Konya

Konya () is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium (), although the Seljuks also called it D ...

on December 21.

Soon after he was blocked by the intervention of Russia, however. As the result of endless discussions between the representatives of the powers, the Porte and the pasha, the Convention of Kütahya

The Convention of Kütahya, also known as the Peace Agreement of Kütahya, ended the Egyptian–Ottoman War (1831–1833)

The First Egyptian–Ottoman War or First Syrian War (1831–1833) was a military conflict between the Ottoman Empir ...

was signed on May 14, 1833, by which the sultan agreed to bestow on Muhammad Ali the pashaliks of Syria, Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

and Itcheli, together with the district of Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

. The announcement of the pasha's appointment had already been made in the usual way in the annual ''firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman co ...

'' issued on May 3. Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

was bestowed on Ibrahim under the style of muhassil, or collector of the crown revenues, a few days later.

Muhammad Ali now ruled over a virtually independent empire, stretching from the Sudan to the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

, subject only to a moderate annual tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conq ...

. However the unsound foundations of his authority were not long in revealing themselves. Scarcely a year from the signing of the Convention of Kutaya the application by Ibrahim of Egyptian methods of government, notably of the monopolies and conscription, had driven Syrians, Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

and Arabs, into revolt, after first welcoming him as a deliverer. The unrest was suppressed by Muhammad Ali in person, and the Syrians were terrorized, but their discontent encouraged the Sultan Mahmud to hope for revenge, and a renewal of the conflict was only staved off by the anxious efforts of the European powers.

In the spring of 1839 the sultan ordered his army, concentrated under Reshid in the border district of Bir on the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

, to advance over the Syrian frontier. Ibrahim, seeing his flank menaced, attacked it at Nezib

Nizip ( gkm, Nisibis or Nisibina; ota, نزيب) is a town and district of Gaziantep Province of southeastern Turkey.

As of 2010, the population of the city is 96,229. It is located 45 km from the city of Gaziantep, 95 km from Şanlıu ...

on the 24th of June. Once more the Ottomans were utterly routed. Six days later, before the news reached Constantinople, Mahmud died.

Now, with the defeat of the Ottomans and the conquest of Syria, Muhammad Ali had reached the height of his power. For one brief moment in time, he had become the envy of the Egyptian kings of antiquity, controlling Egypt, the Sudan, and Syria (which alone would have made him their better in power) he saw the Ottoman armies collapse or fall into disorganization after their defeat in Syria, and it looked like the Middle East and Anatolia were his for the taking. It looked like he could march all the way to Istanbul, in the minds of some, and place himself on the Sultan's throne.

With the Ottoman Empire at the feet of Muhammad Ali, the European powers were greatly alarmed and issued the Convention of London of 1840, designed to end the war and deal with the likely contingency of Muhammad Ali's refusal. Their intervention during the Oriental Crisis of 1840 was prompt, launching an invasion by a primarily British force (with some French and Greek elements), they made short work of Muhammad Ali's pride and joy: Egypt's modern Armed forces. However, while his army was being defeated, Muhammad saw the possibility of victory in France's unwillingness to participate (it having some warm feelings to the Khedive, and mainly participating with what was considered a token force to try to block a British expansion in North Africa.) However, in spite of France's dislike of an Egypt dominated by the British, it was equally unwilling to allow the ambitious Governor to upset the balance of power, and thus, by waiting for the hope of a better chance at victory, Muhammad Ali had to suffer a harder defeat.

However, though he had lost Syria and his position of great power, the war with the West had not been a complete disaster by any means. For though humiliated and defeated by the Western Powers, the West had no intention of removing him and the block he placed on Ottoman Power. Thus, though the peace treaty was harsh, it achieved one of Muhammad Ali's greatest dreams: to place his family firmly in the reigns of Egyptian power. It was far from all that the crafty Pasha had wanted, but it was what he had to live with, for even in the ending days of the Syrian War, Muhammad was starting to show his age, and would find that he did not have much time left in the world.

End of Muhammad Ali's rule

The end was reached early in 1841. New 'firmans' were issued which confined the pasha's authority to Egypt, including theSinai peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a ...

and certain places on the Arabian side of the Red Sea, and to the Sudan. The most important of these documents is dated February 13, 1841.

The government of the pashalik of Egypt was made hereditary within the family of Muhammad Ali. A map showing the boundaries of Egypt accompanied the firman granting Muhammad Ali the pashalik, a duplicate copy being retained by the Porte. The Egyptian copy is supposed to have been lost in a fire which destroyed a great part of the Egyptian archives. The Turkish copy has never been produced and its existence now appears doubtful. The point was of importance, as in 1892 and again in 1906 boundary disputes arose between Ottoman Empire and the Egyptian Khiedevate.

Various restrictions were laid upon Muhammad Ali, emphasizing his position as vassal. He was forbidden to maintain a fleet and his army was not to exceed 18,000 men. The pasha no longer a disrupting figure in European politics, but he continued to occupy himself with his improvements in Egypt. But times were not all good; the long wars combined with murrain of cattle in 1842 and a destructive Nile flood made matters worse. In 1843 there was a plague of locusts where whole villages were depopulated. Even the sequestered army was a strain enough for a population unaccustomed to the rigidities of the conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

service. Florence Nightingale, the famous British nurse, recounts in her letters from Egypt written in 1849–50, that many an Egyptian family thought it be enough to "protect" their children from the inhumanities of the military service by blinding them in one eye or rendering them unfit by cutting off their limb. But Muhammad Ali was not to be confounded by such tricks of bodily non-compliance, and with that view he set up a special corps of disabled musketeers declaring that one can shoot well enough even with one eye.

Meantime the uttermost farthing was wrung from the wretched ''fellah

A fellah ( ar, فَلَّاح ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller". ...

in'', while they were forced to the building of magnificent public works by unpaid labor. In 1844–45 there was some improvement in the condition of the country as a result of financial reforms the pasha executed. Muhammad Ali, who had been granted the honorary rank of grand vizier in 1842, paid a visit to Istanbul in 1846, where he became reconciled to his old enemy Khosrev Pasha, whom he had not seen since he spared his life at Cairo in 1803.

In 1847 Muhammad Ali laid the foundation stone of the great bridge across the Nile at the beginning of the Delta. Towards the end of 1847, the aged pasha's previously sharp mind began to give way, and by the following June he was no longer capable of administering the government. In September 1848 Ibrahim was acknowledged by the Porte as ruler of the pashalik, but he died in the following November.

Muhammad Ali survived another eight months, dying on August 2, 1849. He had done a great work in Egypt, the most permanent being the weakening of the tie binding the country to Turkey, the starting of the great cotton industry, the recognition of the advantages of European science, and the conquest of the Sudan.

Muhammad Ali's successors

On Ibrahim's death in November 1848 the government of Egypt fell to his nephew Abbas I, the son of Tusun Abbasad. Abbas put an end to the system of commercial monopolies, and during his reign the railway from Alexandria to Cairo was begun at the instigation of the British government. Opposed to European ways, Abbas lived in great seclusion. After a reign of less than six years he was murdered in July 1854 by two of his slaves. He was succeeded by his uncle Said Pasha, the favorite son of Muhammad Ali, who lacked the strength of mind or physical health needed to execute the beneficent projects which he conceived. His endeavour, for instance, to put a stop to the slave raiding which devastated theSudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

was wholly ineffectual. He had a genuine regard for the welfare of the ''fellah

A fellah ( ar, فَلَّاح ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller". ...

in'', and a land law of 1858 secured for them an acknowledgment of freehold

Freehold may refer to:

In real estate

*Freehold (law), the tenure of property in fee simple

* Customary freehold, a form of feudal tenure of land in England

* Parson's freehold, where a Church of England rector or vicar of holds title to benefice ...

as against state ownership.

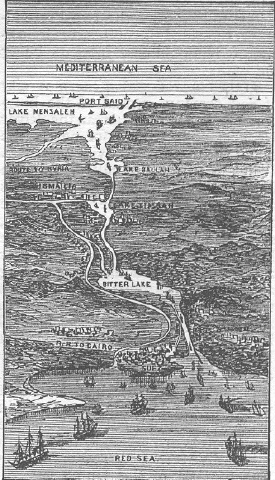

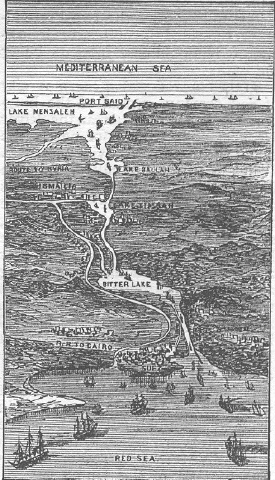

The pasha was much under French influence, and in 1854 was induced to grant to the French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

a concession "to form a financial company to pierce the isthmus" and operate a canal for 99 years. Lord Palmerston was opposed to this project, and the British opposition delayed the ratification of the concession by the Porte for two years. This prompted a second concession in 1856 that obligated the Egyptian government to provide 80% of the labour for the canal's construction. Said also made concessions to the British, for the Eastern Telegraph Company

Cable & Wireless plc was a British telecommunications company. In the mid-1980s, it became the first company in the UK to offer an alternative telephone service to British Telecom (via subsidiary Mercury Communications). The company later of ...

, and another in 1854 allowing the establishment of the Bank of Egypt

Banque Misr ( ar, بنك مصر) is an Egyptian bank co-founded by industrialist Joseph Aslan Cattaui Pasha and economist Talaat Harb Pasha in 1920. The government of the United Arab Republic nationalized the bank in 1960. The bank has branch ...

. He also began the national debt by borrowing £3,293,000 from Messrs Fruhling & Goschen, the actual amount received by the pasha being £2,640,000. In January 1863 Said Pasha died and was succeeded by his nephew Ismail

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

, a son of Ibrahim Pasha.

Ismail the Magnificent

The reign of Ismail, from 1863 to 1879, was initially hailed as a new era of bringing Egypt into modernity. He completed vast development schemes and attempted positive administrative reforms, but this progress, coupled with his personal extravagance led to

The reign of Ismail, from 1863 to 1879, was initially hailed as a new era of bringing Egypt into modernity. He completed vast development schemes and attempted positive administrative reforms, but this progress, coupled with his personal extravagance led to bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debto ...

. The later part of his reign is historically and nationally important simply for its result, which brought European intervention deeply into Egyptian finances and development, and led to the British occupation of Egypt

The history of Egypt under the British lasted from 1882, when it was occupied by British forces during the Anglo-Egyptian War, until 1956 after the Suez Crisis, when the last British forces withdrew in accordance with the Anglo-Egyptian agree ...

shortly thereafter.

In his earlier years of reign, much was changed regarding Egypt's sovereignty, which seemed likely to give Ismail a more important place in history. In 1866 the Ottoman Sultan granted him a ''firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman co ...

'', obtained on condition that he increase his annual tribute from £376,000 to £720,000. This made the succession to the throne of Egypt descend to the eldest of the male children and in the same manner to the eldest sons of these successors, instead of to the eldest male of the family, following the practice of Turkish law. In the next year another ''firman'' bestowed upon him the title of khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"K ...

in lieu of that of ''vali'', borne by Mehemet Ali and his immediate successors. In 1873 a further ''firman'' placed the khedive in many respects in the position of an independent sovereign.

Ismail re-established and improved Muhammad Ali's administrative system, which had fallen into decay under Abbas's uneventful rule. This included a thorough revamping of the customs system which was anarchic, and remodeled on British lines and by English officials. In 1865, he established the Egyptian post office; he reorganized the military schools of his grandfather, and gave some support to the cause of education. Railways, telegraphs, irrigation projects, lighthouses, the harbour works at Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

, and the breakwater at Alexandria, were carried out during his reign, by some of the best contractors of Europe. Most important of all, was Egypt's support for the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

, which finally opened in 1869. Not only did the government buy many shares in the venture, initially intended for British investors, it provided the corvee labour to dig the canal, as well as digging a canal to bring Nile water to the new city of Ismailia

Ismailia ( ar, الإسماعيلية ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city has a population of 1,406,699 (or approximately 750,000, includi ...

at the Suez's midpoint. When Khedive Ismail sought to terminate Egypt's corvee labour obligation, because he needed it for cotton production to take advantage of vastly inflated cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

prices, caused by the loss of American exports during its Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, Egypt was compelled to pay more than £3 million in compensation to the Canal Company. The funds helped pay for the elaborate dredging equipment brought in to replace the labour and needed to complete the canal.

Once that conflict ended Ismail had to find new sources of funding to keep his development and reform efforts alive. Thus the funds required for these public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, sc ...

, as well as the actual labor, were remorselessly extorted from a poverty-stricken population. A striking picture of the condition of the people at this period is given by Lady Duff Gordon in ''Last Letters from Egypt''. Writing in 1867 she said: "I cannot describe the misery here now every day some new tax. Every beast, camel, cow, sheep, donkey and horse is made to pay. The fellaheen can no longer eat bread; they are living on barley-meal mixed with water, and raw green stuff, vetches, &c. The taxation makes life almost impossible: a tax on every crop, on every animal first, and again when it is sold in the market; on every man, on charcoal, on butter, on salt. . . . The people in Upper Egypt are running away by wholesale, utterly unable to pay the new taxes and do the work exacted. Even here (Cairo) the beating for the years taxes is awful."

In the late 1860s Egypt attempted to build a modern navy and ordered several armored ironclads, two each of the "Nijmi Shevket" class and the "Lutfi Djelil" class. Although intended for the Egyptian Navy, these ironclads had to be delivered to the Ottoman Navy in 1869. Egypt was able to keep a navy with a few unarmored warships including the iron steam frigate ''Ibrahim'' and a large yacht, the "Mahroussa" which survives in rebuilt form to the present day.

In the years that followed the condition of things grew worse. Thousands of people died and large sums expended in extending Ismail's dominions in the Sudan and in futile conflicts with Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

. In 1875, the impoverishment of the ''fellah'' had reached such a high point that the ordinary resources of the country no longer sufficed for the most urgent necessities of administration; and the khedive Ismail, having repeatedly broken faith with his creditors, could not raise any more loans on the European market. The taxes were habitually collected many months in advance, and the colossal floating debt was increasing rapidly. In these circumstances Ismail had to realize his remaining assets, and among them sold 176,602 Suez Canal shares to the British government for £976,582, which surrendered Egyptian control of the waterway.

These crises induced the British government to inquire more carefully into the financial condition of the country, where Europeans had invested much capital. In December 1875, Stephen Cave

Sir Stephen Cave (28 December 1820 – 6 June 1880) was a British lawyer, writer and Conservative politician. He notably served as Paymaster-General between 1866 and 1868 and again between 1874 and 1880 and as Judge Advocate General between 187 ...

, MP, and Colonel (later Sir) John Stokes, RE, were sent to Egypt to inquire into Egypt's financial situation. Mr Cave's report, made public only in April 1876, showed that under the existing administration national bankruptcy

A sovereign default is the failure or refusal of the

government of a sovereign state to pay back its debt in full when due. Cessation of due payments (or receivables) may either be accompanied by that government's formal declaration that it wi ...

was inevitable. With no alternatives, European powers used Egypt's indebtedness to extract concessions regarding how the debts would be repaid. Other commissions of inquiry followed, and each one brought Ismail increasingly under European control. The establishment of the Mixed Tribunals in 1876, in place of the system of consular jurisdiction in civil actions, made some of the courts of justice international.

The Caisse de la Dette The Caisse de la Dette Publique ("Public Debt Commission") was an international commission established by a decree issued by Khedive Ismail of Egypt on 2 May 1876 to supervise the payment by the Egyptian government of the loans to the European gove ...

, instituted in May 1876 as a result of the Cave mission, led to international control over a large portion of the government's revenue. In November 1876, the mission of Mr (afterwards Lord) Goschen and M. Joubert on behalf of the British and French bondholders, one result being the establishment of Dual Control, in which an English official would superintend the revenues and a French official would superintend the expenditures of the country. Another result was the international control of the railways and the port of Alexandria, to balance these items. Then, in May 1878, a commission of inquiry of which the principal members were Sir Charles Rivers Wilson, Major Evelyn Baring (afterwards Lord Cromer) and MM. Kremer-Baravelli and Monsieur de Blignières. One result of that inquiry was the extension of international control to the enormous property of the khedive himself.

Driven to desperation in September 1878, Ismail made a virtue of necessity and, in lieu of the Dual Control, accepted a constitutional ministry, under the presidency of Nubar Pasha

Nubar Pasha ( ar, نوبار باشا hy, Նուպար Փաշա (January 1825, Smyrna, Ottoman Empire - 14 January 1899, Paris) was an Egyptian-Armenian politician and the first Prime Minister of Egypt. He served as Prime Minister three times ...

; Rivers Wilson became minister of finance and de Blignières became minister of public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, sc ...

. Professing to be quite satisfied with this arrangement, he announced that Egypt was no longer in Africa but a part of Europe. Within seven months however, he found his constitutional position intolerable, got rid of his irksome cabinet by means of a secretly organized military riot in Cairo, and reverted to his old autocratic methods of government.

Britain and France, anxious about losing influence under this affront, decided to administer chastisement by the hand of the suzerain power, which was delighted to have an opportunity of asserting its authority. The Europeans and the Sublime Porte

Porte may refer to:

*Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman empire

*Porte, Piedmont, a municipality in the Piedmont region of Italy

*John Cyril Porte, British/Irish aviator

*Richie Porte, Australian professional cyclist who competes ...

decided to force Ismail out of office. On the June 26, 1879 Ismail suddenly received from the sultan a curt telegram, addressed to him as ex-khedive of Egypt, informing him that his son Tewfik was appointed his successor. Surprised, he made no attempt at resistance, and Tewfik was at once proclaimed khedive.

Dual control

After a short period of inaction, when it seemed as if the change might be for the worse, Britain and France in November 1879, re-established the Dual Control in the persons of Major Baring and Monsieur de Blignières. For two years the Dual Control governed Egypt. Discontent within various sectors of the elite and among elements of the population at large led to a reaction against European interference. Without any efficient means of self-protection and coercion at its disposal, it had to interfere with the power, privileges and perquisites of the local elite. This elite, so far as its civilian members were concerned, was not very formidable, because these were not likely to go beyond the bounds of intrigue and passive resistance; but it contained a military element who had more courage, and who had learned their power when Ismail employed them for overturning his constitutional ministry. Among the mutinous soldiers on that occasion was an officer calling himselfAhmed Urabi

Ahmad ( ar, أحمد, ʾAḥmad) is an Arabic male given name common in most parts of the Muslim world. Other spellings of the name include Ahmed and Ahmet.

Etymology

The word derives from the root (ḥ-m-d), from the Arabic (), from the ve ...

. He was a charismatic leader who was followed by a group of fellow army officers and many among the lower classes. He became the centre of a protest aimed at protecting the Egyptians from their Turkish and European oppressors. The movement began among the Arab officers, who complained of the preference shown to the officers of Turkish origin; it then expanded into an attack on the privileged position and predominant influence of foreigners; finally, it was directed against all Christians, foreign and native. The government, being too weak to suppress the agitation and disorder, had to make concessions, and each concession produced fresh demands. Urabi was first promoted, then made under-secretary for war, and ultimately a member of the cabinet.

The danger of a serious rising brought the British and French fleets in May 1882 to Alexandria. Because of concerns over the safety of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

and massive British investments in Egypt the Europeans looked to intervene. The French hesitated, however, and the British alone tried to suppress the revolt. On July 11, 1882, after widespread revolts in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, the British fleet bombarded the city. The leaders of the national movement prepared to resist further aggression by force. A conference of ambassadors was held in Constantinople, and the sultan was invited to quell the revolt; but he hesitated to employ his troops against what was far more a threat to European interests.

Egypt occupied by the British

The British government decided to employ armed force, and invited France to cooperate. The French government declined, and a similar invitation toItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

met with a similar refusal. Britain therefore, acting alone, landed troops at Ismailia

Ismailia ( ar, الإسماعيلية ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city has a population of 1,406,699 (or approximately 750,000, includi ...

under Sir Garnet Wolseley

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, (4 June 183325 March 1913), was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became one of the most influential and admired British generals after a series of successes in Canada, W ...

, and suppressed the revolt by the battle of Tel-el-Kebir on September 13, 1882. While it had been claimed this was meant to be only a temporary intervention, British troops would remain in Egypt until 1956.

The landing in Ismailia happened due to the British failure to perform the original plan to destroy defences in Alexandria, then march to Cairo.

With no fleet to protect the city, British battleships easily bombarded the city, forcing many civilians to migrate. Uraby, the Egyptian army commander, was not allowed to have troopers exceeding 800 men strong. Defeated in Alexandria, he decided to fight the British on ground he gathered the 2,200 men at Kafr-el-sheikh and constructed strong base which he held against a force of 2,600 British who were trying to advance on Cairo from the north. The battle took place between an Egyptian army, headed by Ahmed ‘Urabi

Ahmad ( ar, أحمد, ʾAḥmad) is an Arabic male given name common in most parts of the Muslim world. Other spellings of the name include Ahmed and Ahmet.

Etymology

The word derives from the root (ḥ-m-d), from the Arabic (), from the v ...

, and British forces headed by Sir Archibald Alison. As a result, the British abandoned any hope they may have had of reaching Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

from the north, and shifted their base of operations to Ismailia

Ismailia ( ar, الإسماعيلية ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city has a population of 1,406,699 (or approximately 750,000, includi ...

instead. The British forces retreating to their main base at Alexandria. The British then transported a large force of Ismailia where 13,000 of them engaged 16,000 Egyptians. They met Uraby at El-Tal El-Kebier which was weakly prepared comparing with the defence lines at Kafr- El- Shiekh to withstand heavy artillery, so the fort was taken and Uraby was exiled to India.

The khedive, who had taken refuge in Alexandria, returned to Cairo, and a ministry was formed under Sherif Pasha, with Riaz Pasha as one of its leading members. On assuming office, the first thing it had to do was to bring to trial the chiefs of the rebellion. Urabi pleaded guilty, was sentenced to death, the sentence being commuted by the khedive to banishment; and Riaz resigned in disgust. This solution of the difficulty was brought about by Lord Dufferin

Frederick Temple Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (21 June 182612 February 1902) was a British public servant and prominent member of Victorian society. In his youth he was a popular figure in the court of Queen Vict ...

, then British ambassador at Istanbul, who had been sent to Egypt as high commissioner to adjust affairs and report on the situation.

One of his first acts, after preventing the application of capital punishment to the ringleaders of the revolt, was to veto the project of protecting the khedive and his government by means of a Praetorian guard recruited from Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, and to insist on the principle that Egypt must be governed in a truly liberal spirit. Passing in review all the departments of the administration, he laid down the general lines on which the country was to be restored to order and prosperity, and endowed, if possible, with the elements of self-government for future use.

Demographic changes during the reign of Muhammad Ali and his successors

During this period the stagnation of the Egyptian population that had been fluctuating at about 4 million level for many centuries prior to 1805 was changed by the start of a rapid population growth. This growth was quite slow till the 1840s, but since then the Egyptian population grew up to about 7 million by the 1880s, and the first modern census registered 9,734,405 people in Egypt in 1897. This was achieved by a radical decrease in mortality rates and concomitant growth of life expectancy by 10–15 years, which, of course, indicates that Muhammad Ali and his successors in fact achieved impressive success in the effective modernization of Egypt and that the actual quality of life of the majority of the Egyptian population significantly increased in the 19th century.; In Egypt in the 19th century the overall pattern of the population growth was explicitly non-Malthusian

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, ...

and can be characterized as hyperbolic

Hyperbolic is an adjective describing something that resembles or pertains to a hyperbola (a curve), to hyperbole (an overstatement or exaggeration), or to hyperbolic geometry.

The following phenomena are described as ''hyperbolic'' because they ...

, whereby the increase in population was accompanied not by decreases of the relative population growth rates, but by their increases.

Rulers of the Dynasty

Eleven rulers spanned the 148 years of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty from 1805 to 1953. * Muhammad Ali Dynasty family treeSee also

* :Muhammad Ali dynasty *History of Modern Egypt

According to most scholars the history of modern Egypt dates from the start of Muhammad Ali's rule in 1805 and his launching of Egypt's modernization project that involved building a new army and suggesting a new map for the country, though t ...

*Al-Nahda

The Nahda ( ar, النهضة, translit=an-nahḍa, meaning "the Awakening"), also referred to as the Arab Awakening or Enlightenment, was a cultural movement that flourished in Arabic-speaking regions of the Ottoman Empire, notably in Egypt, ...

References

External links

Egyptian Royalty

— by Ahmed S. Kamel, Hassan Kamel Kelisli-Morali, Georges Soliman and Magda Malek

L'Egypte D'Antan... Egypt in Bygone Days

— by Max Karkegi

Early Photos: Egypt in the 1800s

— slideshow by

Life magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

Collection: Egypt in the 19th Century Photography

from the

University of Michigan Museum of Art

The University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor, Michigan with is one of the largest university art museums in the United States. Built as a war memorial in 1909 for the university's fallen alumni from the Civil War, Alumni Memorial Hall ori ...

Further reading

* Daly, M.W. ''The Cambridge History Of Egypt Volume 2 Modern Egypt, from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century'' (1998online

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Egypt Under The Muhammad Ali Dynasty Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty + + Egyptian families Egyptian pashas Egyptian nobility 19th century in Egypt 20th century in Egypt