Education during the Slave Period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the era of

During the era of

South Carolina passed the first laws prohibiting slave education in 1740. While there were no limitations on reading or drawing, it became illegal to teach slaves to write. This legislation followed the 1739

South Carolina passed the first laws prohibiting slave education in 1740. While there were no limitations on reading or drawing, it became illegal to teach slaves to write. This legislation followed the 1739

As early as the 1710s slaves were receiving Biblical literacy from their masters. Enslaved writer

As early as the 1710s slaves were receiving Biblical literacy from their masters. Enslaved writer

In the 1780s a group called the

In the 1780s a group called the  In examining the educational practices of the period, it is difficult to ascertain absolute figures or numbers. W. E. B. Du Bois and other contemporaries estimated that by 1865 as many as 9% of slaves attained at least a marginal degree of literacy. Genovese comments: "this is entirely plausible and may even be too low". Especially in cities and sizable towns, many free blacks and literate slaves had greater opportunities to teach others, and both white and black activists operated illegal schools in cities such as

In examining the educational practices of the period, it is difficult to ascertain absolute figures or numbers. W. E. B. Du Bois and other contemporaries estimated that by 1865 as many as 9% of slaves attained at least a marginal degree of literacy. Genovese comments: "this is entirely plausible and may even be too low". Especially in cities and sizable towns, many free blacks and literate slaves had greater opportunities to teach others, and both white and black activists operated illegal schools in cities such as

Mary Ellen Snodgrass, Civil Disobedience: An Encyclopedic History of Dissidence in the United States Routledge, Apr 8, 2015, p. 105

/ref> *Mother

Harvard Educational Review, SELF-TAUGHT African American Education in Slavery and Freedom by HEATHER ANDREA WILLIAMS CHAPEL HILL: UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS, 2005

*http://www.aaihs.org/rethinking-early-slave-literacy/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Education During The Slave Period Slavery in the United States Slave Period

During the era of

During the era of slavery in the United States

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Sl ...

, the education of enslaved African Americans, except for religious instruction, was discouraged, and eventually made illegal in most of the Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

states. After 1831 (the revolt of Nat Turner

Nat Turner's Rebellion, historically known as the Southampton Insurrection, was a rebellion of enslaved Virginians that took place in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831.Schwarz, Frederic D.1831 Nat Turner's Rebellion" ''American Heri ...

), the prohibition was extended in some states to free blacks as well. Even if educating Blacks was legal, they still had little access to education, in the North as well as the South.

Historical context

Slave owner

The following is a list of slave owners, for which there is a consensus of historical evidence of slave ownership, in alphabetical order by last name.

A

* Adelicia Acklen (1817–1887), at one time the wealthiest woman in Tennessee, she inh ...

s saw literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

as a threat to the institution of slavery and their financial investment in it; as a North Carolina statute stated, "Teaching slaves to read and write, tends to excite dissatisfaction in their minds, and to produce insurrection and rebellion." Literacy enabled the enslaved to read the writings of abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

s, which discussed the abolition of slavery and described the slave revolution in Haiti of 1791–1804 and the end of slavery in the British Empire in 1833. It also allowed slaves to learn that thousands of enslaved individuals had escaped, often with the assistance of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

, to safe refuges in the Northern states and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. Literacy also was believed to make the enslaved unhappy at best, insolent and sullen at worst. As put by prominent Washington lawyer Elias B. Caldwell:

Nonetheless, both free and enslaved African Americans continued to learn to read as a result of the sometimes clandestine efforts of free African Americans, sympathetic whites, and informal schools that operated furtively during this period. In addition, slaves used storytelling, music, and crafts to pass along cultural traditions and other information.

In the Northern states, African Americans sometimes had access to formal schooling, and were more likely to have basic reading and writing skills. The Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

were important in establishing education programs in the North in the years before and after the Revolutionary War.

During the U.S. colonial period, several prominent religious groups both saw the conversion of slaves as a spiritual obligation, and the ability to read scriptures was seen as part of this process for Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. The Great Awakening

Great Awakening refers to a number of periods of religious revival in American Christian history. Historians and theologians identify three, or sometimes four, waves of increased religious enthusiasm between the early 18th century and the late ...

served as a catalyst for encouraging education for all members of society.

Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

saw the spiritual aspect differently, but black nuns decisively took up the charge of educating slaves and free persons in various regions, especially Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

(Henriette DeLille

Henriette Díaz DeLille, SSF (March 11, 1813 – November 16, 1862) was a Louisiana Creole of color and Catholic nun from New Orleans. Her father was a white man from France, her mother was a "quadroon", and her grandfather came from Spain. She ...

and her Sisters of the Holy Family), Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

(Mother Mathilda Beasley Mathilda Taylor Beasley, OSF (November 14, 1832 - December 20, 1903) was a Black Catholic educator and religious leader who was the first African American nun to serve in the state of Georgia. She founded a group of African-American nuns and one o ...

), and the Washington DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

area (Mary Lange

Mary Elizabeth Lange, Oblate Sisters of Providence, OSP (born Elizabeth Clarisse Lange; c. 1789 – February 3, 1882) was a Black Catholicism, Black Catholic religious sister who founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the first African America ...

and her Oblate Sisters of Providence

The Oblate Sisters of Providence (OSP) is a Roman Catholic women's religious institute, founded by Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, OSP, and Rev. James Nicholas Joubert, SS in 1828 in Baltimore, Maryland for the education of girls of African des ...

, including Anne Marie Becraft

Anne Marie Becraft, OSP (1805 – December 16, 1833) was an American educator and nun. One of the first African-American nuns in the Catholic Church, she established a school for black girls in Washington, D.C and later joined the Oblate Sister ...

).

While reading was encouraged in religious instruction, writing often was not. Writing was seen as a mark of status, unnecessary for many members of society, including slaves. This is due to the fact that many had to learn how to read to be able to write. Runaway Wallace Turnage "learnt" how to read and write "during that time f his enslavement

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

His ...

and since eescaped the clutches of those held who held imin slavery." It is believed that he learned with the help of the slaves who helped him escape to different sites: for example, someone may have taught him how to read directions to get to the next town. Memorization, catechisms

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adult c ...

, and Scripture formed the basis of what education was available.

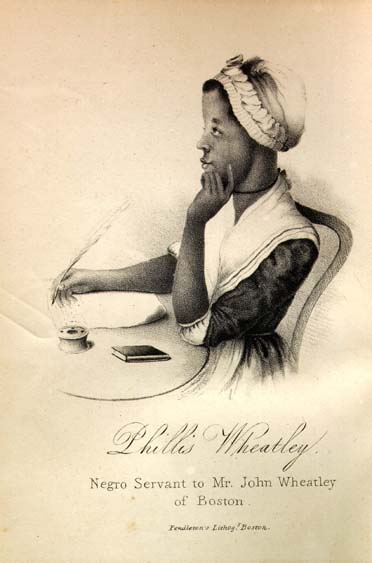

Despite the lack of importance generally given to writing instruction, there were some notable exceptions; perhaps the most famous of these was Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley Peters, also spelled Phyllis and Wheatly ( – December 5, 1784) was an American author who is considered the first African-American author of a published book of poetry. Gates, Henry Louis, ''Trials of Phillis Wheatley: Ameri ...

, whose poetry won admiration on both sides of the Atlantic.

The end of slavery and, with it, the legal prohibition of slave education did not mean that education for former slaves or their descendants became widely available. Racial segregation in schools, ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' and then ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'', and inadequate funding of schools for African Americans, if they existed at all, continued into the twenty-first century (2022).

Legislation and prohibitions

South Carolina passed the first laws prohibiting slave education in 1740. While there were no limitations on reading or drawing, it became illegal to teach slaves to write. This legislation followed the 1739

South Carolina passed the first laws prohibiting slave education in 1740. While there were no limitations on reading or drawing, it became illegal to teach slaves to write. This legislation followed the 1739 Stono Rebellion

The Stono Rebellion (also known as Cato's Conspiracy or Cato's Rebellion) was a slave revolt that began on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina. It was the largest slave rebellion in the Southern Colonies, with 25 colonists and 35 t ...

. As fears proliferated among plantation owners

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

concerning the spread of abolitionist materials, forged passes, and other incendiary writings, the perceived need to restrict slaves’ ability to communicate with one another became more pronounced. For this reason, the State Assembly enacted the following: "Be it therefore Enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That all and every Person and Persons whatsoever, who shall hereafter teach or cause any Slave to be taught to write, or shall use to employ any slave as a Scribe in any Manner of Writing whatsoever, hereafter taught to write, every such offense forfeit the Sum of One Hundred Pounds current Money." While the law does not clarify any consequences for the slaves who might attain this more highly prized form of literacy, the financial consequences for teachers are clear.

In 1759, Georgia modeled its own ban on teaching slaves to write after South Carolina's earlier legislation. Again, reading was not prohibited. Throughout the colonial era, reading instruction was tied to the spread of Christianity, so it did not suffer from restrictive legislation until much later.

The most oppressive limits on slave education were a reaction to Nat Turner's Revolt in Southampton County, Virginia

Southampton County is a county located on the southern border of the Commonwealth of Virginia. North Carolina is to the south. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,996. Its county seat is Courtland.

History

In the early 17th century ...

, during the summer of 1831. This event not only caused shock waves across the slave-holding South, but it had a particularly far-reaching impact on education over the next three decades. The fears of slave insurrections and the spread of abolitionist material and ideology led to radical restrictions on gatherings, travel, and—of course—literacy. The ignorance of the slaves was considered necessary to the security of the slaveholders. Not only did owners fear the spread of specifically abolitionist materials, they did not want slaves to question their authority; thus, reading and reflection were to be prevented at any cost.

Each state responded differently to the Turner insurrection. Virginians "immediately, as an act of retaliation or vengeance, abolished every colored school within their borders; and having dispersed the pupils, ordered the teachers to leave the State forthwith, and never more to return." While Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

already had laws designed to prevent slave literacy, in 1841 the state legislature passed a law that required all free African Americans to leave the state so that they would not be able to educate or incite the slave population. Other states, such as South Carolina, followed suit. The same legislation required that any black preacher would have to be given permission to speak before appearing in front of a congregation. Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

passed in 1831 a law that prevented the meeting of a dozen or more blacks late at night; additionally, black preachers were to petition a judge or justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

before speaking before any assembly.

While states like South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

had not developed legislation that prohibited education for slaves, other more moderate states responded directly to the 1831 revolt. In 1833, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

enacted a law that fined anyone who undertook a slave's education between $250 and $550; the law also prohibited any assembly of African Americans—slave or free—unless five slave owners were present or an African-American preacher had previously been licensed by an approved denomination.

Even North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, which had previously allowed free African-American children to attend schools alongside whites, eventually responded to fears of insurrection. By 1836, the public education of all African Americans was strictly prohibited.

The situation was not much better in the North. African Americans were frequently barred from public schools. Schools like the African Free School

The African Free School was a school for children of slaves and free people of color in New York City. It was founded by members of the New York Manumission Society, including Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, on November 2, 1787. Many of its alumni ...

were few and far between.

Education and subversion in the Antebellum Era

As early as the 1710s slaves were receiving Biblical literacy from their masters. Enslaved writer

As early as the 1710s slaves were receiving Biblical literacy from their masters. Enslaved writer Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley Peters, also spelled Phyllis and Wheatly ( – December 5, 1784) was an American author who is considered the first African-American author of a published book of poetry. Gates, Henry Louis, ''Trials of Phillis Wheatley: Ameri ...

was taught in the home of her master. She ended up using her skills to write poetry and address leaders of government on her feelings about slavery (although she died in abject poverty and obscurity). Not everyone was lucky enough to have the opportunities Wheatley had. Many slaves did learn to read through Christian instruction, but only those whose owners allowed them to attend. Some slave owners would only encourage literacy for slaves because they needed someone to run errands for them and other small reasons. They did not encourage slaves to learn to write. Slave owners saw writing as something that only educated white men should know. African-American preachers would often attempt to teach some of the slaves to read in secret, but there were very few opportunities for concentrated periods of instruction. Through spirituals

Spirituals (also known as Negro spirituals, African American spirituals, Black spirituals, or spiritual music) is a genre of Christian music that is associated with Black Americans, which merged sub-Saharan African cultural heritage with the e ...

, stories, and other forms of oral literacy, preachers, abolitionists, and other community leaders imparted valuable political, cultural, and religious information.

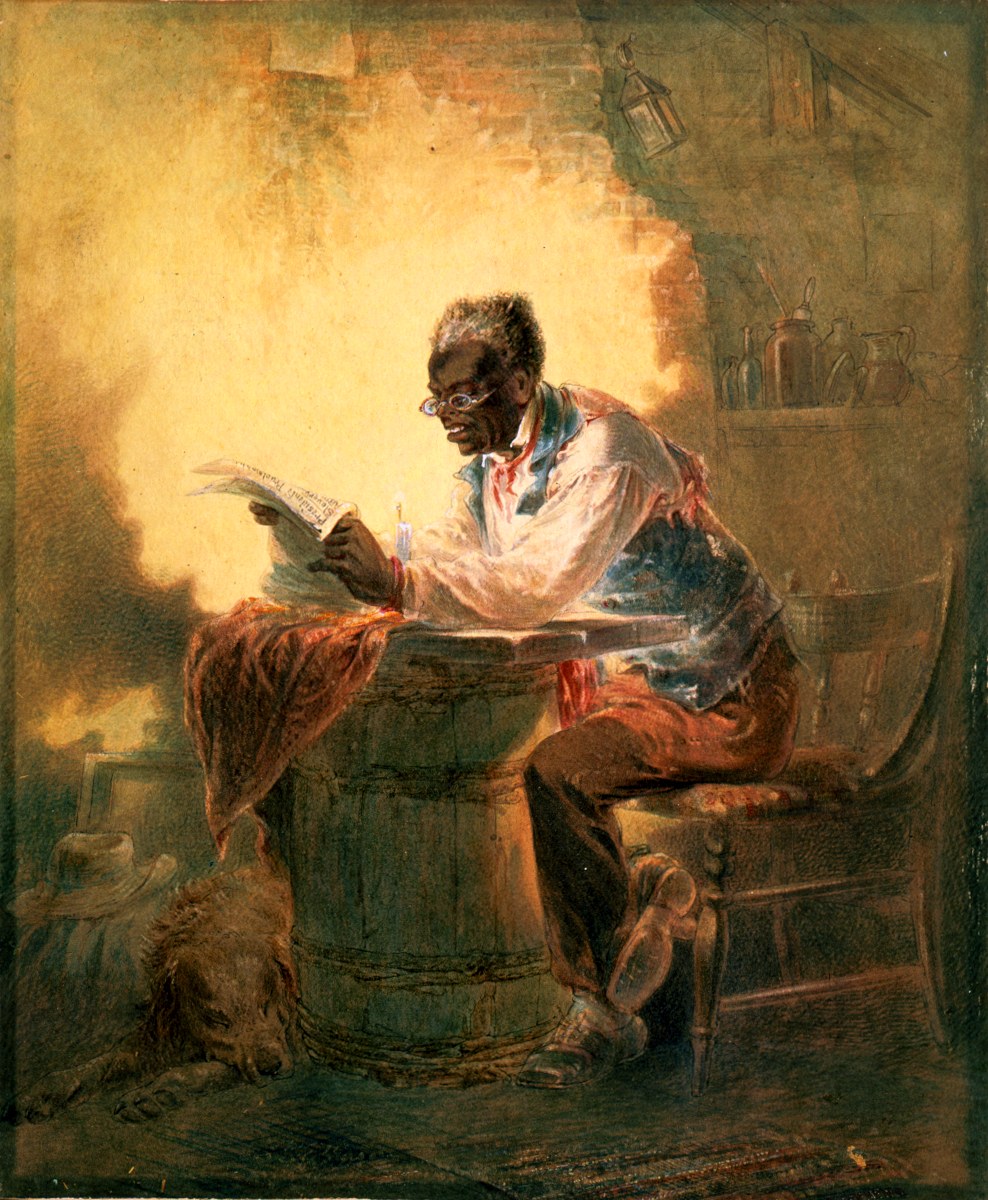

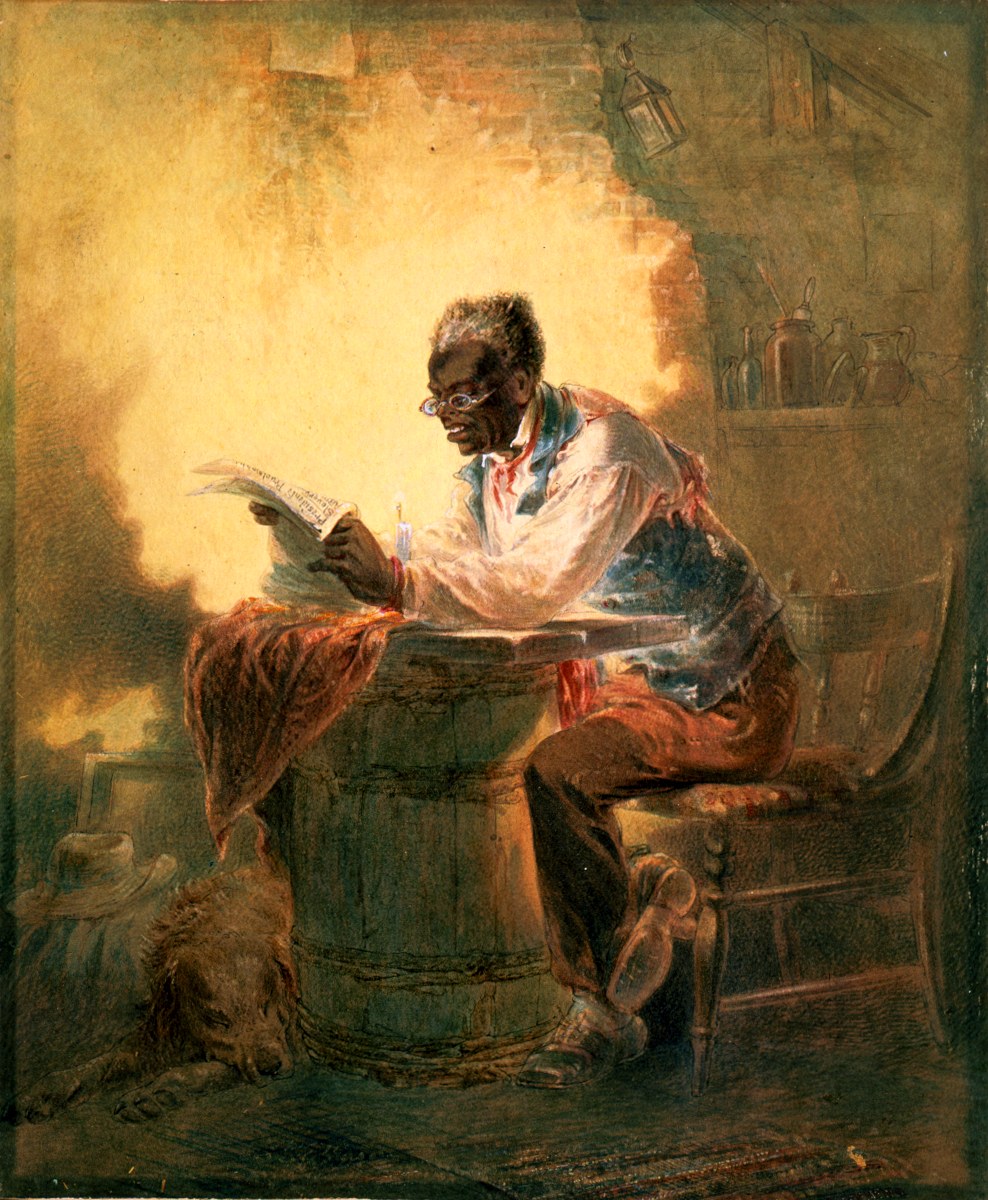

There is evidence of slaves practicing reading and writing in secret. Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

s were discovered near George Washington's estate in Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

with writings carved in them. Bly noted that "237 unidentified slates, 27 pencil leads, 2 pencil slates, and 18 writing slates were uncovered in houses once occupied by Jefferson's black bond servants." This shows that slaves were secretly practicing their reading and writing skills when they had time alone, most likely at night. They also believe slaves practiced their letters in the dirt because it was much easier to hide than writing on slates. Slaves then passed on their newly-learned skills to others.

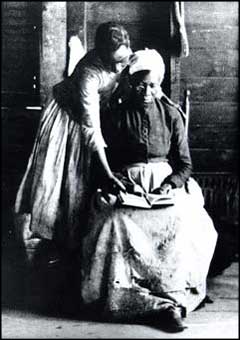

Even though mistresses were more likely than masters to ignore the law and teach slaves to read, children were by far the most likely to flout what they saw as unfair and unnecessary restrictions. While peer tutelage was limited in scope, it was common for slave children to carry the white children's books to school. Once there, they would sit outside and try to follow the lessons through the open windows.

The regular practice of hiring out slaves also helped spread literacy. As seen in Frederick Douglass's own narrative, it was common for the literate to share their learning. As a result of the constant flux, few if any plantations would fail to have at least a few literate slaves.

Douglass states in his biography that he understood the pathway from slavery to freedom and it was to have the power to read and write. In contrast, Schiller wrote: "After all, most educated slaves did not find that the acquisition of literacy led inexorably and inevitably to physical freedom and the idea that they needed an education to achieve and experience existential freedoms is surely problematic."

Free black schools

In the 1780s a group called the

In the 1780s a group called the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American abolition society. It was founded April 14, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and held four meetings. Seventeen of the 24 men who attended initia ...

(PAS) took on anti-slavery tasks. They helped former slaves with educational and economic aid. They also helped with legal obligations, like making sure they did not get sold back into slavery. Another anti-slavery group, called the New York Manumission Society

The New-York Manumission Society was an American organization founded in 1785 by U.S. Founding Father John Jay, among others, to promote the gradual abolition of slavery and manumission of slaves of African descent within the state of New York. ...

(NYMS), did many things towards the abolition of slavery; one important thing they did was establish a school for free blacks, who were usually barred from white children's schools throughout the U.S. “The NYMS established the African Free School

The African Free School was a school for children of slaves and free people of color in New York City. It was founded by members of the New York Manumission Society, including Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, on November 2, 1787. Many of its alumni ...

in 1787 that, during its first two decades of existence, enrolled between 100 and 200 students annually, registering a total of eight hundred pupils by 1822.” The PAS also instituted a few schools for free blacks and ran them with freed slaves.

They were taught reading, writing, grammar, math, and geography. The schools would have an annual examination day to show the public, parents, and donors the knowledge the students had gained. It mainly was to show the white population that African Americans could function in society. There are some surviving records of what they learned in the free schools. Some of the work showed that they were preparing the students for a middle-class standing in society. Founded in 1787, the African Free School

The African Free School was a school for children of slaves and free people of color in New York City. It was founded by members of the New York Manumission Society, including Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, on November 2, 1787. Many of its alumni ...

provided education for blacks in New York City for more than six decades.

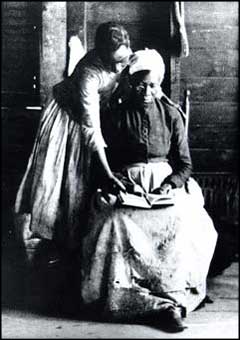

In 1863, an image of two emancipated slave children, Isaac and Rosa, who were studying at the Free School of Louisiana

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, having the ability to do something, without having to obey anyone/anything

* Freethought, a position that beliefs should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism

* Emancipate, to procure ...

, was widely circulated in abolitionist campaigns.

In examining the educational practices of the period, it is difficult to ascertain absolute figures or numbers. W. E. B. Du Bois and other contemporaries estimated that by 1865 as many as 9% of slaves attained at least a marginal degree of literacy. Genovese comments: "this is entirely plausible and may even be too low". Especially in cities and sizable towns, many free blacks and literate slaves had greater opportunities to teach others, and both white and black activists operated illegal schools in cities such as

In examining the educational practices of the period, it is difficult to ascertain absolute figures or numbers. W. E. B. Du Bois and other contemporaries estimated that by 1865 as many as 9% of slaves attained at least a marginal degree of literacy. Genovese comments: "this is entirely plausible and may even be too low". Especially in cities and sizable towns, many free blacks and literate slaves had greater opportunities to teach others, and both white and black activists operated illegal schools in cities such as Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-sma ...

, New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, Charleston, Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, and Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

.

Notable educators

*John Berry Meachum

John Berry Meachum (1789–1854) was an American pastor, businessman, educator and founder of the First African Baptist Church in St. Louis, the oldest black church west of the Mississippi River. At a time when it was illegal in the city to teac ...

, a black pastor, who created a Floating Freedom School

The Floating Freedom School was an educational facility for free and enslaved African Americans on a steamboat on the Mississippi River. It was established in 1847 by the Baptist minister John Berry Meachum. After Meachum's death in 1854, the Fre ...

in 1847 on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

to circumvent anti-literacy laws. James Milton Turner

James Milton Turner (1840 – November 1, 1915) was a Reconstruction Era political leader, activist, educator, and diplomat. As consul general to Liberia, he was the first African-American to serve in the U.S. diplomatic corps.

Early life

Turn ...

attended his school.

* Margaret Crittendon Douglass

Margaret Crittendon Douglass (born 1822; year of death unknown) was a Southern white woman who served one month in jail in 1854 for teaching free black children to read in Norfolk, Virginia. Refusing to hire a defense attorney, she defended h ...

, a white woman who published a memoir after she was imprisoned in Virginia in 1853 for teaching free black children to read.

* Catherine and Jane Deveaux, a black mother and daughter who, with the Catholic nun Mathilda Beasley Mathilda Taylor Beasley, OSF (November 14, 1832 - December 20, 1903) was a Black Catholic educator and religious leader who was the first African American nun to serve in the state of Georgia. She founded a group of African-American nuns and one o ...

, ran underground schools in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

in the early- to mid-1800s./ref> *Mother

Mary Lange

Mary Elizabeth Lange, Oblate Sisters of Providence, OSP (born Elizabeth Clarisse Lange; c. 1789 – February 3, 1882) was a Black Catholicism, Black Catholic religious sister who founded the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the first African America ...

, who with her Oblate Sisters of Providence

The Oblate Sisters of Providence (OSP) is a Roman Catholic women's religious institute, founded by Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, OSP, and Rev. James Nicholas Joubert, SS in 1828 in Baltimore, Maryland for the education of girls of African des ...

founded St. Frances Academy in 1828.

*Mother Henriette DeLille

Henriette Díaz DeLille, SSF (March 11, 1813 – November 16, 1862) was a Louisiana Creole of color and Catholic nun from New Orleans. Her father was a white man from France, her mother was a "quadroon", and her grandfather came from Spain. She ...

, who with her Sisters of the Holy Family founded schools in New Orleans in the mid- to late-1800s, including St. Mary's Academy.

References

*Albanese, Anthony. (1976.) ''The Plantation School''. New York:Vantage Books

Vantage Press was a self-publishing company based in the United States. The company was founded in 1949 and ceased operations in late 2012.

Vantage was the largest vanity press

A vanity press or vanity publisher, sometimes also subsidy publishe ...

.

*William L. Andrews, ed. (1996). ''The Oxford Frederick Douglass News''. New York: Oxford University Press.

*Bly, Antonio T. "Pretends he can read": Runaways and Literacy in Colonial America, 1730-1776." ''Early American Studies

''Early American Studies'' is a peer-reviewed history journal covering the study of the histories and cultures of North America prior to 1850. The journal is sponsored by The McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylva ...

'' 6, no. 2 (Fall 2008): 261-294. America: History & Life, EBSCOhost (accessed October 27, 2014).

*Genovese, Eugene. (1976). ''Roll, Jordan, Roll''. New York: Vintage Books

Vintage Books is a trade paperback publishing imprint of Penguin Random House originally established by Alfred A. Knopf in 1954. The company was purchased by Random House in April 1960, and a British division was set up in 1990. After Random Hous ...

.

*Monaghan, E. J. (2005). ''Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America''. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press

The University of Massachusetts Press is a university press that is part of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The press was founded in 1963, publishing scholarly books and non-fiction. The press imprint is overseen by an interdisciplinar ...

.

*

*

*

*Webber, Thomas. (1978). ''Deep Like Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community 1831-1865''. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

*Woodson, C.G.

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875April 3, 1950) was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He was one of the first scholars to study the h ...

(1915). ''The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861: A History of the Education of the Colored People of the United States from the Beginning of Slavery to the Civil War''. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

External links

Harvard Educational Review, SELF-TAUGHT African American Education in Slavery and Freedom by HEATHER ANDREA WILLIAMS CHAPEL HILL: UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS, 2005

*http://www.aaihs.org/rethinking-early-slave-literacy/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Education During The Slave Period Slavery in the United States Slave Period

Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

Underground education