Edmund Alexander Parkes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

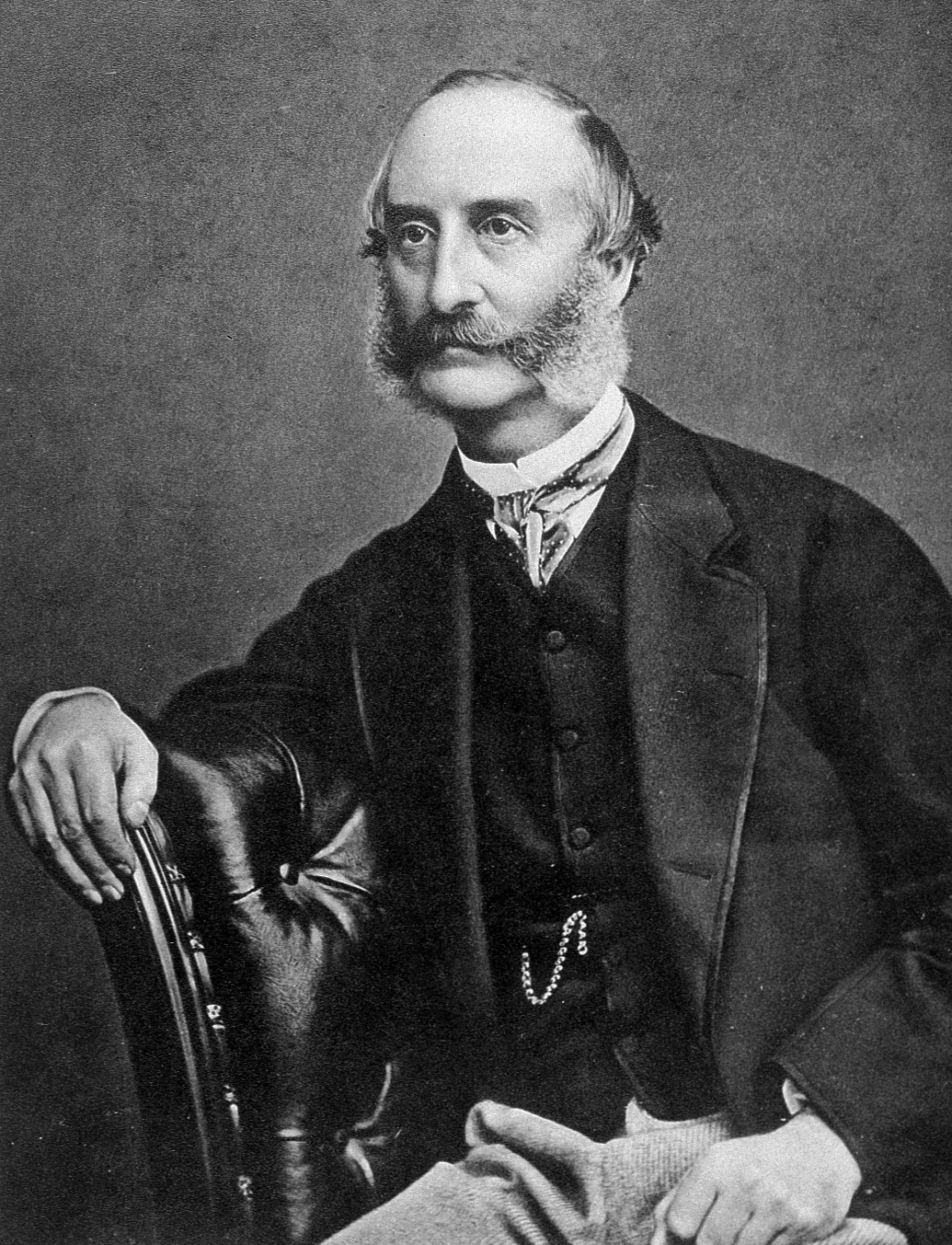

Edmund Alexander Parkes (29 December 1819 – 15 March 1876) was an English physician, known as a hygienist, particularly in the military context.

Edmund Alexander Parkes (29 December 1819 – 15 March 1876) was an English physician, known as a hygienist, particularly in the military context.

Parkes' name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.

Parkes' name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.

Edmund Alexander Parkes (29 December 1819 – 15 March 1876) was an English physician, known as a hygienist, particularly in the military context.

Edmund Alexander Parkes (29 December 1819 – 15 March 1876) was an English physician, known as a hygienist, particularly in the military context.

Early life

Parkes was born at Bloxham inOxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primaril ...

, the son of William Parkes, of the Marble-yard, Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

, and Frances, daughter of Thomas Byerley. Parkes was educated at Christ's Hospital, London, and received his professional training at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

and Hospital. In 1841 he graduated M.B. at the University of London; in 1840 he had become a member of the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

. At an early age he worked in the laboratory of his uncle, Anthony Todd Thomson

Anthony Todd Thomson (7 January 1778 – 3 July 1849) was a Scottish doctor and pioneer of dermatology.

Life

Anthony Todd Thomson was the younger son of Alexander Thomson and was born in Edinburgh, where his parents were staying temporarily, on 7 ...

, and for Thomson he later lectured on materia medica and medical jurisprudence

Medical jurisprudence or legal medicine is the branch of science and medicine involving the study and application of scientific and medical knowledge to legal problems, such as inquests, and in the field of law. As modern medicine is a legal ...

.

In April 1842 Thomson was gazetted assistant-surgeon to the 84th (York and Lancaster) Regiment, and at age 22 embarked with it for India, serving in Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

and Moulmein. During this period he obtained clinical experience of tropical diseases, particularly of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver tissue. Some people or animals with hepatitis have no symptoms, whereas others develop yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes ( jaundice), poor appetite, vomiting, tiredness, abdominal ...

, and cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

. In September 1845 he retired from the army, and, returning home, practised in Upper Seymour Street, and then Harley Street

Harley Street is a street in Marylebone, Central London, which has, since the 19th century housed a large number of private specialists in medicine and surgery. It was named after Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.

; but he never gained a large practice. In 1846 he graduated M.D. at the University of London. In 1849 he was elected special professor of clinical medicine at University College, and physician to University College Hospital. At the opening of one of the sessions of the college he delivered an introductory lecture on ''Self-training by the Medical Student''.

Renkioi Hospital

In 1855 he was selected by the government to travel to Turkey to select a site for, organise, and superintend a large civil hospital to relieve the pressure on the hospitals at Scutari during theCrimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

. He selected Renkioi, on the Asiatic bank of the Dardanelles, and remained there until the end of the war in 1856. This was the site of the 1,000 patient prefabricated

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. The term ...

timber Renkioi Hospital

Renkioi Hospital was a pioneering prefabricated building made of wood, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel as a British Army military hospital for use during the Crimean War.

Background

During 1854 Britain entered into the Crimean War, and th ...

, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

, and set up by William Eassie Jnr, whose father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

's Gloucester Docks-based firm had constructed it. The hospital was outside the orbit of Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War ...

, and had a nursing staff selected by Parkes and Sir James Clark, including as a volunteer Parkes's sister.

Later life

In 1860 anArmy Medical School

Founded by U.S. Army Brigadier General George Miller Sternberg, MD in 1893, the Army Medical School (AMS) was by some reckonings the world's first school of public health and preventive medicine. (The other institution vying for this distincti ...

was established at Fort Pitt, Chatham, and Parkes, who had been consulted on the scheme by Sidney Herbert as Secretary of State for War, accepted the chair of hygiene. University College appointed him emeritus professor, and a marble bust of Parkes was placed in the museum.

At the Army Medical School at Chatham Parkes organised a system of instruction. In 1863 the school was transferred to the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley

Netley, officially referred to as Netley Abbey, is a village on the south coast of Hampshire, England. It is situated to the south-east of the city of Southampton, and flanked on one side by the ruins of Netley Abbey and on the other by the R ...

. Parkes was constantly engaged in protracted official inquiries connected with hygiene. He was a member of General Henry Eyre's "Pack Committee", which substituted the valise equipment for the cumbrous knapsack. In 1863 he was appointed by the crown to the General Medical Council

The General Medical Council (GMC) is a public body that maintains the official register of medical practitioners within the United Kingdom. Its chief responsibility is to "protect, promote and maintain the health and safety of the public" by ...

, in succession to Sir Charles Hastings. He was a member of the council of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, where he was elected a Fellow in 1861; and he was elected to the senate of the University of London.

Death, memorials and legacy

In 1850 Parkes had married Mary Jane Chattock ofSolihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blyth ...

. She died, after severe suffering, in 1873, without issue. Parkes died on 15 March 1876 aged 56, at his residence, Sydney Cottage, Bitterne

Bitterne is an eastern suburb and ward of Southampton, England.

Bitterne derives its name not from the similarly named bird, the bittern, but probably from the bend in the River Itchen; the Old English words ''byht'' and ''ærn'' together mean ...

, near Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

, and he was buried by the side of his wife at Solihull.

Several memorials were established in Parkes's memory. At University College, London, a museum of hygiene was founded, of which the original trustees were Sir William Jenner

Sir William Jenner, 1st Baronet, GCB, QHP, FRCP, FRS (30 January 181511 December 1898) was a significant English physician primarily known for having discovered the distinction between typhus and typhoid.

Biography

Jenner was born at Ch ...

, Edward Sieveking, and George Vivian Poore. It was opened in 1877, and was formally incorporated under license of the Board of Trade; it was moved in 1882 from University College to new premises in Margaret Street, Cavendish Square. This Parkes Museum amalgamated with the Sanitary Institute in 1888, but retained its name; in 1956 it became the Health Exhibition Centre (opened 1961), closed in 1971 when the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health moved away.

At Netley, a portrait of Parkes, by Messrs. Barraud & Jerrard, was in the anteroom of the army medical staff mess; a triennial prize of seventy-five guineas, and a large gold medal bearing Parkes's portrait, was established for the best essay on a subject connected with hygiene, the prize to be open to the medical officers of the army, navy, and Indian service of executive rank, on full pay; and a bronze medal, also bearing the portrait of Parkes, was instituted, to be awarded at the close of each session to the best student in hygiene.

Works

The Manual

In 1864 Parkes published the first edition of the ''Manual of Practical Hygiene''; it reached during his lifetime a fourth edition, an eighth edition in 1891, and was translated into many languages. It used a traditional airs, waters and places structure, going back toHippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

, and this persisted for a generation. In 1896 it was revised by James Lane Notter and R. H. Firth, in a version that was a standard, through six editions, for military hygiene until 1905.

Other works

Parkes took as the subject of his thesis for M.D. the connection between dysentery and Indian hepatitis. The ''Remarks on the Dysentery and Hepatitis of India'', contained advanced views on the pathology of the diseases. In 1847 he published ''On Asiatic and Algide Cholera'', written mainly in India, where he had seen two epidemics; and in the following year a paper on ''Intestinal Discharges in Cholera'', and another on the ''Early Cases of Cholera in London''. In 1849 he wrote on ''Diseases of the Heart'' in the '' Medical Times'', to which he became frequent contributor. In 1851 Parkes completed and edited Anthony Todd Thomson's ''Practical Treatise on Diseases Affecting the Skin'' and in 1852 he published a paper on the action of ''Liquor Potassæ in Health and Disease''. He also at that time wrote much for the ''Medical Times''. From 1852 to 1855 he edited the ''British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review''. In 1855 he delivered theGulstonian lectures

The Goulstonian Lectures are an annual lecture series given on behalf of the Royal College of Physicians in London. They began in 1639. The lectures are named for Theodore Goulston (or Gulston, died 1632), who founded them with a bequest

A bequ ...

on pyrexia

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using va ...

at the Royal College of Physicians; they were published in the ''Medical Times'' of that year. The results of his hospital administration in Renkioi were recorded in his published report.

In 1860 Parkes published ''The Composition of the Urine in Health and Disease, and under the Action of Remedies''. He started in 1861, at the request of Sir James Brown Gibson, an annual ''Review of the Progress of Hygiene'', which appeared in the ''Army Medical Department Blue-Book'', to 1875. In three papers in the ''Proceedings of the Royal Society

''Proceedings of the Royal Society'' is the main research journal of the Royal Society. The journal began in 1831 and was split into two series in 1905:

* Series A: for papers in physical sciences and mathematics.

* Series B: for papers in life s ...

'' (two in 1867, and one in 1871) he described the ''Effects of Diet and Exercise on the Elimination of Nitrogen''. He confirmed independently the observations of Adolf Eugen Fick

Adolf Eugen Fick (3 September 1829 – 21 August 1901) was a German-born physician and physiologist.

Early life and education

Fick began his work in the formal study of mathematics and physics before realising an aptitude for medicine. H ...

and Johannes Wislicenus

Johannes Wislicenus (24 June 1835 – 5 December 1902) was a German chemist, most famous for his work in early stereochemistry.

Biography

The son of the radical Protestant theologian Gustav Wislicenus, Johannes was born on 24 June 1835 in Kl ...

, against Justus Liebig's theory that muscular work implies the destruction of muscular tissue by oxidation. Parkes suggested that the elimination of urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

is not dependent on the amount of muscular exercise, but on the consumption of nitrogenous food; and that muscular tissue does not consume itself as a fuel doing work. His experiments on the effects of alcohol on the human body (in which he was assisted by Cyprian Wollowicz) were in three papers (in 1870, 1872, and 1874), on the ''Effects of Brandy on the Body-temperature, Pulse, and Respiration of Healthy Men''; and he completed a ''Comparative Inquiry into the Effects of Coffee, Extract of Meat, and Alcohol on Men marching''. He also published a report, on the evidence collected during the Ashanti campaign, on the value of a spirit ration for troops.

In 1868 Parkes published a ''Scheme of Medical Tuition'' in ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal and one of the oldest of its kind. It is also the world's highest-impact academic journal. It was founded in England in 1823.

The journal publishes original research articles ...

'' (later republished and dedicated to Sir George Burrows). He placed great value on the practical study of chemistry and physiology in the laboratory, on the teaching of the methods of physical examination before starting clinical work, and on the utilisation of the out-patient department for teaching purposes. He argued the inefficiency of the examinations of the licensing bodies.

Parkes contributed freely to medical periodicals. He also published his inaugural lecture at the Army Medical School, entitled ''On the Care of Old Age'' (1862). He delivered the Croonian lectures

The Croonian Medal and Lecture is a prestigious award, a medal, and lecture given at the invitation of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians.

Among the papers of William Croone at his death in 1684, was a plan to endow a single l ...

before the College of Physicians in March 1871, selecting for his subject ''Some Points connected with the Elimination of Nitrogen from the Human Body''. For some years he delivered a short course of lectures on hygiene to the corps of Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is head ...

at Chatham. In 1871 he made, with John Scott Burdon-Sanderson, a report on the sanitary state of Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

. On 26 June 1876 Sir William Jenner delivered before the Royal College of Physicians the Harveian oration

The Harveian Oration is a yearly lecture held at the Royal College of Physicians of London. It was instituted in 1656 by William Harvey, discoverer of the systemic circulation. Harvey made financial provision for the college to hold an annual fea ...

which Parkes was engaged in writing at the time of his death.

The last work from Parkes's pen was a manual ''On Personal Care of Health'', which was published posthumously by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) is a UK-based Christian charity. Founded in 1698 by Thomas Bray, it has worked for over 300 years to increase awareness of the Christian faith in the UK and across the world.

The SPCK is t ...

. A revised edition of his work on ''Public Health'', which was a concise sketch of the sanitary considerations connected with the land, with cities, villages, houses, and individuals, was edited by Sir William Aitken, in 1876.

Recognition

Parkes' name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.

Parkes' name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.

References

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Parkes, Edmund Alexander 1819 births 1876 deaths 19th-century English medical doctors Fellows of the Royal Society