Earwig on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Earwigs make up the

The scientific name for the order, "Dermaptera", is

The scientific name for the order, "Dermaptera", is

Earwigs are abundant and can be found throughout the

Earwigs are abundant and can be found throughout the

Most earwigs are flattened (which allows them to fit inside tight crevices, such as under bark) with an elongated body generally long. The largest extant species is the Australian giant earwig ('' Titanolabis colossea'') which is approximately long, while the possibly extinct

Most earwigs are flattened (which allows them to fit inside tight crevices, such as under bark) with an elongated body generally long. The largest extant species is the Australian giant earwig ('' Titanolabis colossea'') which is approximately long, while the possibly extinct

Earwigs are

Earwigs are

File:Nesting Earwig Chester UK 1.jpg, Female earwig in her nest, with eggs

File:Nesting Earwig Chester UK 2.jpg, Female earwig in her nest with newly hatched young

The eggs hatch in about seven days. The mother may assist the nymphs in hatching. When the nymphs hatch, they eat the egg casing and continue to live with the mother. The nymphs look similar to their parents, only smaller, and will nest under their mother and she will continue to protect them until their second molt. The nymphs feed on food regurgitated by the mother, and on their own molts. If the mother dies before the nymphs are ready to leave, the nymphs may eat her.

After five to six

The common earwig is an omnivore, eating plants and ripe fruit as well as actively hunting

The common earwig is an omnivore, eating plants and ripe fruit as well as actively hunting

The fossil record of the Dermaptera starts in the

The fossil record of the Dermaptera starts in the

Google Books

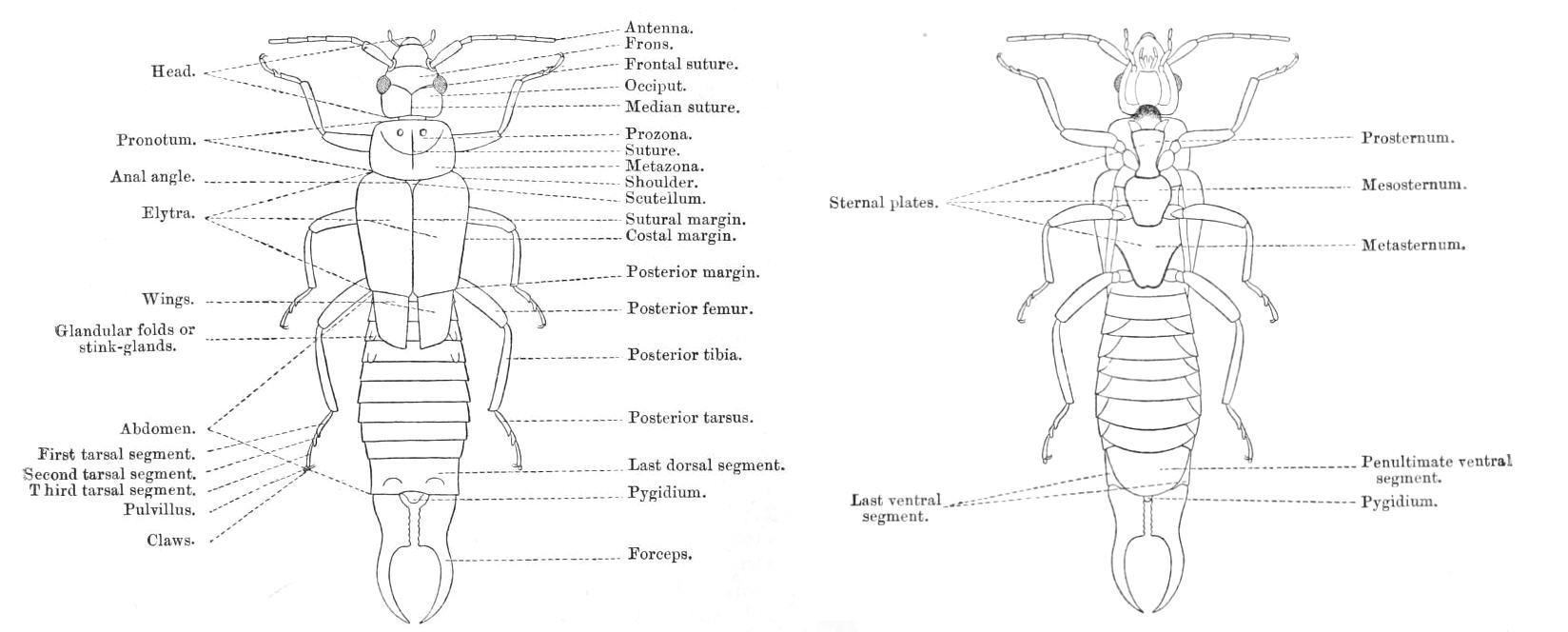

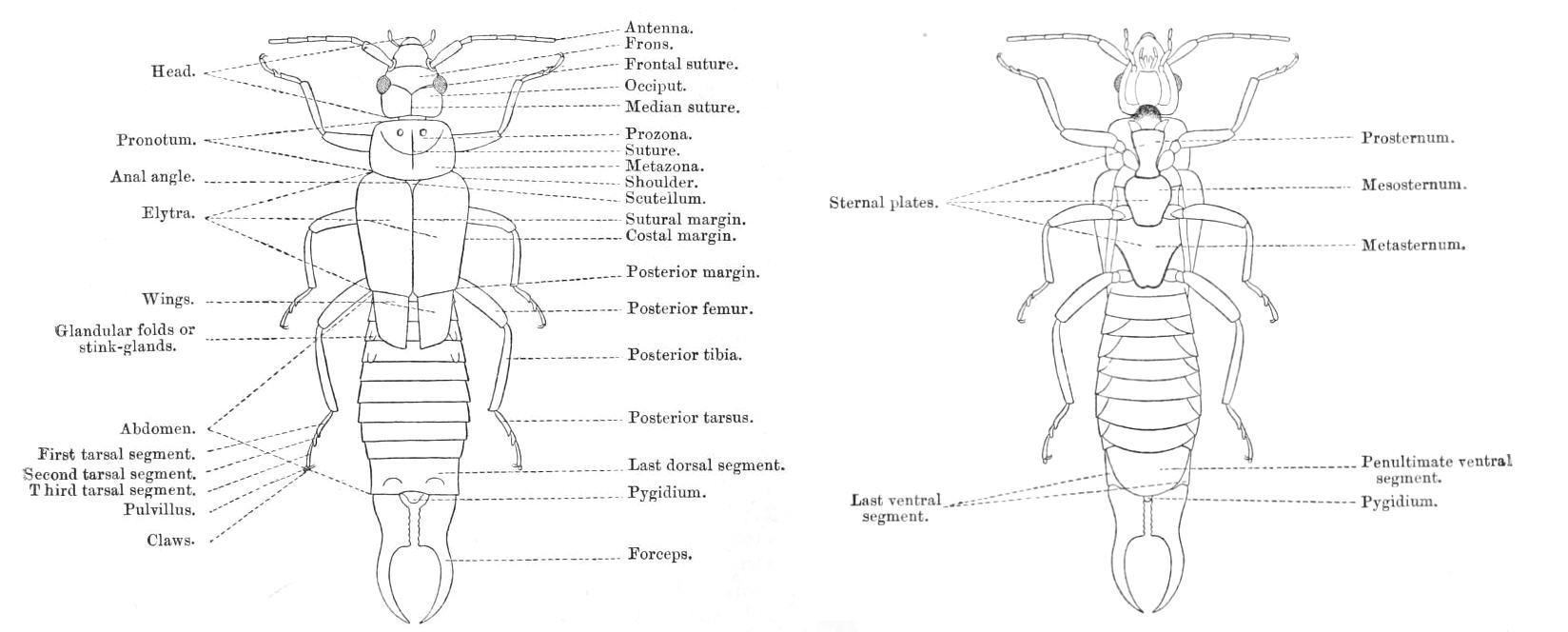

on 25 November 2009. * ''General body shape'': Elongate; dorso-ventrally flattened. * ''Head'': Prognathous. Antennae are segmented. Biting-type mouthparts.

Dermaptera is relatively small compared to the other orders of

Dermaptera is relatively small compared to the other orders of

Earwig Research Center

by Fabian Haas, Heilbronn

Dermaptera Species File

by Heidi Hopkins, Michael D. Maehr, Fabian Haas, and Lesley S. Deem

on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures website * Langston RL & JA Powell (1975

The earwigs of California (Order Dermaptera)

Bulletin of the California Insect Survey. 20

Earwigs

from What's That Bug? {{DEFAULTSORT:Earwig Rhaetian first appearances Extant Late Triassic first appearances Exopterygota Polyneoptera

insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three ...

order Dermaptera. With about 2,000 species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

in 12 families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideal ...

, they are one of the smaller insect orders. Earwigs have characteristic cerci, a pair of forcep-like pincer Pincer may refer to:

* Pincers (tool)

*Pincer (biology), part of an animal

*Pincer ligand

In chemistry, a transition metal pincer complex is a type of coordination complex with a pincer ligand. Pincer ligands are chelating agents that binds tig ...

s on their abdomen, and membranous wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expre ...

folded underneath short, rarely used forewings

Insect wings are adult outgrowths of the insect exoskeleton that enable insects to fly. They are found on the second and third thoracic segments (the mesothorax and metathorax), and the two pairs are often referred to as the forewings and hindwi ...

, hence the scientific order name, "skin wings". Some groups are tiny parasites on mammals and lack the typical pincers. Earwigs are found on all continents except Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

.

Earwigs are mostly nocturnal and often hide in small, moist crevices during the day, and are active at night, feeding on a wide variety of insects and plants. Damage to foliage, flowers, and various crops is commonly blamed on earwigs, especially the common earwig ''Forficula auricularia

''Forficula auricularia'', the common earwig or European earwig, is an omnivorous insect in the family Forficulidae. The European earwig survives in a variety of environments and is a common household insect in North America. The name ''earwig'' ...

.''

Earwigs have five molts in the year before they become adults. Many earwig species display maternal care, which is uncommon among insects. Female earwigs may care for their eggs, and even after they have hatched as nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label= Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ...

s will continue to watch over offspring until their second molt. As the nymphs molt, sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

such as differences in pincer shapes begins to show.

Extant Dermaptera belong to the suborder Neodermaptera

Neodermaptera, sometimes called Catadermaptera,BioLib.cz

suborder Catadermaptera Steinmann, 1986 (retrieved 16 Se ...

, which first appeared during the suborder Catadermaptera Steinmann, 1986 (retrieved 16 Se ...

Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

. Some earwig specimen fossils are placed extinct suborders Archidermaptera

Archidermaptera is an extinct suborder of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. It is one of two extinct suborders of earwigs, and contains two families (Protodiplatyidae and Dermapteridae) known only from Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous fossils.Fa ...

or Eodermaptera

Eodermaptera is an extinct suborder of earwigs known from the Middle Jurassic to Mid Cretaceous. Defining characteristics include " tarsi three-segmented, tegmina retain venation, 8th and 9th abdominal tergite in females are narrowed, but separ ...

, the former dating to the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch of the Triassic Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch and followed by the Early Jurassic Epoch. ...

and the latter to the Middle Jurassic. Dermaptera belongs to the major grouping Polyneoptera

The cohort Polyneoptera is a proposed taxonomic ranking for the Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets, etc.) and all other Neopteran insects believed to be more closely related to Orthoptera than to any other insect orders. These winged insects, no ...

, and are amongst the earliest diverging members of the group, alongside angel insects (Zoraptera

The insect order Zoraptera, commonly known as angel insects, contains small and soft bodied insects with two forms: winged with wings sheddable as in termites, dark and with eyes (compound) and ocelli (simple); or wingless, pale and without eyes ...

), and stoneflies ( Plecoptera), the exact relationship between the three groups is uncertain.

Etymology

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

in origin, stemming from the words ''derma'', meaning skin, and ''pteron'' (plural ''ptera''), wing. It was coined by Charles De Geer in 1773. The common term, ''earwig,'' is derived from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

'','' which means "ear", and '','' which means "insect", or literally, "beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

". Entomologists suggest that the origin of the name is a reference to the appearance of the hindwings, which are unique and distinctive among insects, and resemble a human ear when unfolded. The name is more popularly thought to be related to the old wives' tale

An old wives' tale is a supposed truth which is actually spurious or a superstition. It can be said sometimes to be a type of urban legend, said to be passed down by older women to a younger generation. Such tales are considered superstition, fol ...

that earwigs burrowed into the brains of humans through the ear and laid their eggs there. Earwigs are not known to purposefully climb into ear canals, but there have been anecdotal reports of earwigs being found in the ear.

Distribution

Earwigs are abundant and can be found throughout the

Earwigs are abundant and can be found throughout the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago ...

. The common earwig was introduced into North America in 1907 from Europe, but tends to be more common in the southern and southwestern parts of the United States. The only native species of earwig found in the north of the United States is the spine-tailed earwig (''Doru aculeatum''), found as far north as Canada, where it hides in the leaf axils of emerging plants in southern Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The p ...

s. However, other families can be found in North America, including Forficulidae

Forficulidae is a family of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. There are more than 70 genera and 490 described species in Forficulidae.

Species in this family include ''Forficula auricularia'' (the European earwig or common earwig) and '' Apterygi ...

('' Doru'' and '' Forficula'' being found there), Spongiphoridae

Spongiphoridae is a family of little earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. There are more than 40 genera and 510 described species in Spongiphoridae.

Genera

These 43 genera belong to the family Spongiphoridae:

* '' Auchenomus'' Karsch, 1886

* ...

, Anisolabididae, and Labiduridae

Labiduridae, whose members are known commonly as striped earwigs, is a relatively large family of earwigs in the suborder Forficulina.See first entry in external links section for reference.

Taxonomy

The family contains a total of approximatel ...

.

Few earwigs survive winter outdoors in cold climates. They can be found in tight crevices in woodland, fields and gardens. Out of about 1,800 species, about 25 occur in North America, 45 in Europe (including 7 in Great Britain), and 60 in Australia.

Morphology

Most earwigs are flattened (which allows them to fit inside tight crevices, such as under bark) with an elongated body generally long. The largest extant species is the Australian giant earwig ('' Titanolabis colossea'') which is approximately long, while the possibly extinct

Most earwigs are flattened (which allows them to fit inside tight crevices, such as under bark) with an elongated body generally long. The largest extant species is the Australian giant earwig ('' Titanolabis colossea'') which is approximately long, while the possibly extinct Saint Helena earwig

The Saint Helena earwig or Saint Helena giant earwig (''Labidura herculeana'') is an extinct species of very large earwig endemism, endemic to the oceanic island of Saint Helena in the south Atlantic Ocean.

Description

Growing as large as lon ...

(''Labidura herculeana'') reached . Earwigs are characterized by the cerci, or the pair of forceps

Forceps (plural forceps or considered a plural noun without a singular, often a pair of forceps; the Latin plural ''forcipes'' is no longer recorded in most dictionaries) are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Fo ...

-like pincers on their abdomen; male earwigs generally have more curved pincers than females. These pincers are used to capture prey, defend themselves and fold their wings under the short tegmina

A tegmen (plural: ''tegmina'') designates the modified leathery front wing on an insect particularly in the orders Dermaptera ( earwigs), Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets and similar families), Mantodea (praying mantis), Phasmatodea (stick an ...

. The antennae are thread-like with at least 10 segments.

Males in the six familes Karschiellidae, Pygidicranidae, Diplatyidae, Apachyidae, Anisolabisidae and Labiduridae have paired penises, while the males in the remaining groups have a single penis. Both penises are symmetrical in Pygidicranidae and Diplatyidae, but in Karschiellidae the left one is strongly reduced. Apachyidae, Anisolabisidae, and Labiduridae have an asymmetrical pair, with left and right one pointing on opposite directions when not in use. The females have just a single genital opening, so only one of the paired penises is ever used during copulation.

The forewings are short oblong leathery plates used to cover the hindwings like the elytra

An elytron (; ; , ) is a modified, hardened forewing of beetles (Coleoptera), though a few of the true bugs (Hemiptera) such as the family Schizopteridae are extremely similar; in true bugs, the forewings are called hemelytra (sometimes alterna ...

of a beetle, rather than to fly. Most species have short and leather-like forewings with very thin hindwings, though species in the former suborders Arixeniina and Hemimerina (epizoic species, sometimes considered as ectoparasites) are wingless and blind with filiform segmented cerci (today these are both included merely as families in the suborder Neodermaptera). The hindwing is a very thin membrane that expands like a fan, radiating from one point folded under the forewing. Even though most earwigs have wings and are capable of flight, they are rarely seen in flight. These wings are unique in venation and in the pattern of folding that requires the use of the cerci.

Internal

Theneuroendocrine system

Neuroendocrinology is the branch of biology (specifically of physiology) which studies the interaction between the nervous system and the endocrine system; i.e. how the brain regulates the hormonal activity in the body. The nervous and endocrine ...

is typical of insects. There is a brain, a subesophageal ganglion, three thoracic ganglia, and six abdominal ganglia. Strong neuron connections connect the neurohemal corpora cardiaca to the brain and frontal ganglion, where the closely related median corpus allatum produces juvenile hormone III in close proximity to the neurohemal dorsal arota. The digestive system of earwigs is like all other insects, consisting of a fore-, mid-, and hindgut, but earwigs lack gastric caecae which are specialized for digestion in many species of insect. Long, slender (excretory) malpighian tubules

The Malpighian tubule system is a type of excretory and osmoregulatory system found in some insects, myriapods, arachnids and tardigrades.

The system consists of branching tubules extending from the alimentary canal that absorbs solutes, water ...

can be found between the junction of the mid- and hind gut.

The reproductive system of females consist of paired ovaries, lateral oviducts, spermatheca

The spermatheca (pronounced plural: spermathecae ), also called receptaculum seminis (plural: receptacula seminis), is an organ of the female reproductive tract in insects, e.g. ants, bees, some molluscs, oligochaeta worms and certain other in ...

, and a genital chamber. The lateral ducts are where the eggs leave the body, while the spermatheca is where sperm is stored. Unlike other insects, the gonopore

A gonopore, sometimes called a gonadopore, is a genital pore in many invertebrates. Hexapods, including insects have a single common gonopore, except mayflies, which have a pair of gonopores. More specifically, in the unmodified female it is t ...

, or genital opening is behind the seventh abdominal segment. The ovaries are primitive in that they are polytrophic (the nurse cell In general biology or reproductive physiology the term nurse cell is defined as a cell which provides food, helps other cells and provides stability to their neighboring cells. The term nurse cell is used in several unrelated ways in different scien ...

s and oocyte

An oocyte (, ), oöcyte, or ovocyte is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The femal ...

s alternate along the length of the ovariole

An ovariole is a tubular component of the insect ovary, and the basic unit of egg production. Each ovariole is composed of a germarium (the germline stem cell niche) at the anterior tip, a set of developing oocytes contained within follicles, a ...

). In some species these long ovarioles branch off the lateral duct, while in others, short ovarioles appear around the duct.

Life cycle and reproduction

hemimetabolous

Hemimetabolism or hemimetaboly, also called incomplete metamorphosis and paurometabolism,McGavin, George C. ''Essential Entomology: An Order-by-Order Introduction''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. pp. 20. is the mode of development of certa ...

, meaning they undergo incomplete metamorphosis, developing through a series of 4 to 6 molt

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

s. The developmental stages between molts are called instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'', "form", "likeness") is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, between each moult (''ecdysis''), until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to grow or ...

s. Earwigs live for about a year from hatching. They start mating in the autumn, and can be found together in the autumn and winter. The male and female will live in a chamber in debris, crevices, or soil deep. After mating, the sperm may remain in the female for months before the eggs are fertilized. From midwinter to early spring, the male will leave, or be driven out by the female. Afterward the female will begin to lay 20 to 80 pearly white eggs in two days. Some earwigs, those parasitic in the suborders Arixeniina and Hemimerina, are viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the ...

(give birth to live young); they would be fed by a sort of placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste exchange between the physically separate mate ...

. When first laid, the eggs are white or cream-colored and oval-shaped, but right before hatching they become kidney-shaped and brown. Each egg is approximately tall and wide.

Earwigs are among the few non-social insect species that show maternal care. The mother will pay close attention to the needs of her eggs, such as warmth and protection, though studies have shown that the mother does not pay attention to the eggs as she collects them. The mother has been shown to pick up wax balls by accident, but they would eventually be rejected as they do not have the proper scent. The mother will also faithfully defend the eggs from predators, not leaving them to eat unless the clutch goes bad. Another distinct maternal care unique to earwigs is that the mother continuously cleans the eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

to protect them from fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

. Studies have found that the urge to clean the eggs persists for days after they are removed; when the eggs were replaced after hatching, the mother continued to clean them for up to 3 months.

instars

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'', "form", "likeness") is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, between each moult (''ecdysis''), until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to grow or ass ...

, the nymphs will molt into adults. The male's forceps will become curved, while the females' forceps remain straight. They will also develop their natural color, which can be anything from a light brown (as in the tawny earwig) to a dark black (as in the ringlegged earwig). In species of winged earwigs, the wings will start to develop at this time. The forewings of an earwig are sclerotized to serve as protection for the membranous hindwings.

Behaviour

Most earwigs are nocturnal and inhabit small crevices, living in small amounts of debris, in various forms such as bark and fallen logs. Species have been found to be blind and living in caves, or cavernicolous, reported to be found on the island of Hawaii and in South Africa. Food typically consists of a wide array of living and dead plant and animal matter. For protection from predators, the species ''Doru taeniatum

''Doru taeniatum'', the lined earwig, is a species of earwig in the family Forficulidae. It is found in Central America, North America, and South America.

References

Further reading

*

External links

*

Forficulidae

Articles created ...

'' of earwigs can squirt foul-smelling yellow liquid in the form of jets from scent glands on the dorsal side of the third and fourth abdominal segment. It aims the discharges by revolving the abdomen, a maneuver that enables it simultaneously to use its pincers in defense.

Under exceptional circumstances, earwigs form swarms and can take over significant areas of a district. In August 1755 they appeared in vast numbers near Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK, especially in the cracks and crevices of "old wooden buildings...so that they dropped out oftentimes in such multitudes as to literally cover the floor." A similar "plague" occurred in 2006, in and around a woodland cabin near the Blue Ridge Mountains, U.S.; it persisted through winter and lasted at least two years.

Ecology

Earwigs are mostly scavengers, but some are omnivorous or predatory. The abdomen of the earwig is flexible and muscular. It is capable of maneuvering as well as opening and closing the forceps. The forceps are used for a variety of purposes. In some species, the forceps have been observed in use for holdingprey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

, and in copulation

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal penetra ...

. The forceps tend to be more curved in males than in females.

The common earwig is an omnivore, eating plants and ripe fruit as well as actively hunting

The common earwig is an omnivore, eating plants and ripe fruit as well as actively hunting arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s. To a large extent, this species is also a scavenger, feeding on decaying plant and animal matter if given the chance. Observed prey include largely plant lice, but also large insects such as bluebottle flies and woolly aphids. Plants that they feed on typically include clover

Clover or trefoil are common names for plants of the genus ''Trifolium'' (from Latin ''tres'' 'three' + ''folium'' 'leaf'), consisting of about 300 species of flowering plants in the legume or pea family Fabaceae originating in Europe. The genus ...

, dahlia

Dahlia (, ) is a genus of bushy, tuberous, herbaceous perennial plants native to Mexico and Central America. A member of the Asteraceae (former name: Compositae) family of dicotyledonous plants, its garden relatives thus include the sunflower, ...

s, zinnia

''Zinnia'' is a genus of plants of the tribe Heliantheae within the family Asteraceae. They are native to scrub and dry grassland in an area stretching from the Southwestern United States to South America, with a centre of diversity in Mexico ...

s, butterfly bush, hollyhock

''Alcea'' is a genus of over 80 species of flowering plants in the mallow family Malvaceae, commonly known as the hollyhocks. They are native to Asia and Europe. The single species of hollyhock from the Americas, the streambank wild hollyhock, ...

, lettuce

Lettuce (''Lactuca sativa'') is an annual plant of the family Asteraceae. It is most often grown as a leaf vegetable, but sometimes for its stem and seeds. Lettuce is most often used for salads, although it is also seen in other kinds of food, ...

, cauliflower, strawberry, blackberry

The blackberry is an edible fruit produced by many species in the genus ''Rubus'' in the family Rosaceae, hybrids among these species within the subgenus ''Rubus'', and hybrids between the subgenera ''Rubus'' and ''Idaeobatus''. The taxonomy ...

, sunflowers

''Helianthus'' () is a genus comprising about 70 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the daisy family Asteraceae commonly known as sunflowers. Except for three South American species, the species of ''Helianthus'' are native to N ...

, celery

Celery (''Apium graveolens'') is a marshland plant in the family Apiaceae that has been cultivated as a vegetable since antiquity. Celery has a long fibrous stalk tapering into leaves. Depending on location and cultivar, either its stalks, ...

, peach

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, non-f ...

es, plums, grapes

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began perhaps 8,000 years ago, ...

, potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

es, rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

s, seedling beans and beet

The beetroot is the taproot portion of a beet plant, usually known in North America as beets while the vegetable is referred to as beetroot in British English, and also known as the table beet, garden beet, red beet, dinner beet or golden beet ...

s, and tender grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns a ...

shoots and roots; they have also been known to eat corn silk, damaging the corn.

Species of the suborders Arixeniina and Hemimerina are generally considered epizoic, or living on the outside of other animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s, mainly mammals. In the Arixeniina, family Arixeniidae

Arixeniidae is a family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. Arixeniidae was formerly considered a suborder, Arixeniina, but was reduced in rank to family and included in the new suborder Neodermaptera.

Arixeniidae is represented by two gene ...

, species of the genus ''Arixenia

''Arixenia'' is a genus of earwigs, one of only two genera in the family Arixeniidae, and contains two species.

See also

* Earwig

Earwigs make up the insect order Dermaptera. With about 2,000 species in 12 families, they are one of th ...

'' are normally found deep in the skin folds and gular pouch of Malaysian hairless bulldog bats (''Cheiromeles torquatus''), apparently feeding on bats' body or glandular secretions. On the other hand, species in the genus '' Xeniaria'' (still of the suborder Arixeniina) are believed to feed on the guano and possibly the guanophilous arthropods in the bat's roost, where it has been found. Hemimerina includes '' Araeomerus'' found in the nest of long-tailed pouch rats (''Beamys''), and '' Hemimerus'' which are found on giant '' Cricetomys'' rats.

Earwigs are generally nocturnal, and typically hide in small, dark, and often moist areas in the daytime. They can usually be seen on household walls and ceilings. Interaction with earwigs at this time results in a defensive free-fall to the ground followed by a scramble to a nearby cleft or crevice. During the summer they can be found around damp areas such as near sinks and in bathrooms. Earwigs tend to gather in shady cracks or openings or anywhere that they can remain concealed during daylight. Picnic tables, compost and waste bins, patios, lawn furniture, window frames, or anything with minute spaces (even artichoke

The globe artichoke ('' Cynara cardunculus'' var. ''scolymus'' ),Rottenberg, A., and D. Zohary, 1996: "The wild ancestry of the cultivated artichoke." Genet. Res. Crop Evol. 43, 53–58. also known by the names French artichoke and green artich ...

blossoms) can potentially harbour them.

Predators and parasites

Earwigs are regularly preyed upon by birds, and like many other insect species they are prey for insectivorous mammals, amphibians, lizards, centipedes, assassin bugs, and spiders.Arnold, Richard A. "Earwigs." ''Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World.'' Vol. 4. Eds. Anne Hildyard, Paul Thompson and Amy Prior. (Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2001) 497. European naturalists have observed bats preying upon earwigs. Their primary insect predators are parasitic species ofTachinidae

The Tachinidae are a large and variable family of true fly, flies within the insect order Fly, Diptera, with more than 8,200 known species and many more to be discovered. Over 1,300 species have been described in North America alone. Insects in t ...

, or tachinid flies, whose larvae are endoparasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s. One species of tachinid fly, '' Triarthria setipennis'', has been demonstrated to be successful as a biological control of earwigs for almost a century. Another tachinid fly and parasite of earwigs, ''Ocytata pallipes'', has shown promise as a biological control agent as well. The common predatory wasp, the yellow jacket

Yellowjacket or yellowjacket is the common name in North America for predatory social wasps of the genera ''Vespula'' and ''Dolichovespula''. Members of these genera are known simply as "wasps" in other English-speaking countries. Most of these ...

(''Vespula maculifrons''), preys upon earwigs when abundant. A small species of roundworm, ''Mermis nigrescens

''Mermis nigrescens'' is a species of nematode known commonly as the grasshopper nematode.Capinera, JGrasshopper nematode, ''Mermis nigrescens''.EENY-500. University of Florida, IFAS. 2011.Cranshaw, WColorado State University Extension. 2008. Rev ...

'', is known to occasionally parasitize earwigs that have consumed roundworm eggs with plant matter. At least 26 species of parasitic fungus from the order Laboulbeniales

The Laboulbeniales is an order of Fungi within the class Laboulbeniomycetes. They are also known by the colloquial name beetle hangers or labouls. The order includes around 2,325 species of obligate insect ectoparasites that produce cellular ...

have been found on earwigs. The eggs and nymphs are also cannibalized by other earwigs. A species of tyroglyphoid mite, ''Histiostoma polypori'' ( Histiostomatidae, Astigmata), are observed on common earwigs, sometimes in great densities; however, this mite feeds on earwig cadavers and not its live earwig transportation. Hippolyte Lucas

Pierre-Hippolyte Lucas (17 January 1814 – 5 July 1899) was a French entomologist.

Lucas was an assistant- naturalist at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. From 1839 to 1842 he studied fauna as part of the scientific commission on the e ...

observed scarlet acarine mites on European earwigs.

Evolution

The fossil record of the Dermaptera starts in the

The fossil record of the Dermaptera starts in the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch of the Triassic Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch and followed by the Early Jurassic Epoch. ...

to Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-J ...

period about in England and Australia, and comprises about 70 specimens in the extinct suborder Archidermaptera

Archidermaptera is an extinct suborder of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. It is one of two extinct suborders of earwigs, and contains two families (Protodiplatyidae and Dermapteridae) known only from Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous fossils.Fa ...

. Some of the traits believed by neontologists to belong to modern earwigs are not found in the earliest fossils, but adults had five-segmented tarsi (the final segment of the leg), well developed ovipositors, veined tegmina (forewings) and long segmented cerci; in fact the pincers would not have been curled or used as they are now. The theorized stem group of the Dermaptera are the Protelytroptera

Protelytroptera is an extinct order of insects thought to be a stem group from which the modern Dermaptera evolved. These insects, which resemble modern Blattodea, or Cockroaches, are known from the Permian of North America, Europe and Austral ...

, which are similar to modern Blattodea

Blattodea is an order of insects that contains cockroaches and termites. Formerly, termites were considered a separate order, Isoptera, but genetic and molecular evidence suggests they evolved from within the cockroach lineage, cladistically ...

(cockroaches) with shell-like forewings and the large, unequal anal fan, are known from the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last ...

of North America, Europe and Australia. No fossils from the Triassic — during which Dermaptera would have evolved from Protelytroptera — have been found. Amongst the most frequently suggested order of insects to be the closest relatives of Dermaptera is Notoptera

The wingless insect order Notoptera, a group first proposed in 1915, had been largely unrecognized since its original conception, until resurrected in 2004. As now defined, the order comprises five families, three of them known only from fossils ...

, theorized by Giles in 1963. However, other arguments have been made by other authors linking them to Phasmatodea, Embioptera

The order Embioptera, commonly known as webspinners or footspinners, are a small group of mostly tropical and subtropical insects, classified under the subclass Pterygota. The order has also been called Embiodea or Embiidina. More than 400 ...

, Plecoptera, and Dictyoptera

Dictyoptera (from Greek δίκτυον ''diktyon'' "net" and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing") is an insect superorder that includes two extant orders of polyneopterous insects: the order Blattodea (termites and cockroaches together) and the o ...

. A 2012 mitochondrial DNA study suggested that this order is the sister to stoneflies of the order Plecoptera.Wan X, Kim MI, Kim MJ, Kim I (2012) Complete mitochondrial genome of the free-living earwig, ''Challia fletcheri'' (Dermaptera: Pygidicranidae) and phylogeny of Polyneoptera. PLoS One 7(8):e42056. A 2018 phylogenetic analysis found that their closest living relatives were angel insects of the order Zoraptera

The insect order Zoraptera, commonly known as angel insects, contains small and soft bodied insects with two forms: winged with wings sheddable as in termites, dark and with eyes (compound) and ocelli (simple); or wingless, pale and without eyes ...

, with very high support.

Archidermaptera is believed to be sister to the remaining earwig groups, the extinct Eodermaptera and the living suborder Neodermaptera (= former suborders Forficulina, Hemimerina, and Arixeniina). The extinct suborders have tarsi with five segments (unlike the three found in Neodermaptera) as well as unsegmented cerci. No fossil Hemimeridae and Arixeniidae are known. Species in Hemimeridae were at one time in their own order, Diploglassata, Dermodermaptera, or Hemimerina. Like most other epizoic species, there is no fossil record, but they are probably no older than late Tertiary

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

.

Some evidence of early evolutionary history is the structure of the antennal heart, a separate circulatory organ consisting of two ampulla

An ampulla (; ) was, in Ancient Rome, a small round vessel, usually made of glass and with two handles, used for sacred purposes. The word is used of these in archaeology, and of later flasks, often handle-less and much flatter, for holy water or ...

e, or vesicles, that are attached to the frontal cuticle near the bases of the antennae. These features have not been found in other insects. An independent organ exists for each antenna, consisting of an ampulla

An ampulla (; ) was, in Ancient Rome, a small round vessel, usually made of glass and with two handles, used for sacred purposes. The word is used of these in archaeology, and of later flasks, often handle-less and much flatter, for holy water or ...

, attached to the frontal cuticle medial to the antenna base and forming a thin-walled sac with a valved ostium on its ventral side. They pump blood by elastic connective tissue, rather than muscle.

Taxonomy

Distinguishing characteristics

The characteristics which distinguish the order Dermaptera from other insect orders are:Gillot, C. ''Entomology'' 2nd Ed. (1995) Springer, , . Accessed oGoogle Books

on 25 November 2009. * ''General body shape'': Elongate; dorso-ventrally flattened. * ''Head'': Prognathous. Antennae are segmented. Biting-type mouthparts.

Ocelli

A simple eye (sometimes called a pigment pit) refers to a form of eye or an optical arrangement composed of a single lens and without an elaborate retina such as occurs in most vertebrates. In this sense "simple eye" is distinct from a multi-l ...

absent. Compound eyes in most species, reduced or absent in some taxa.

* ''Appendages'': Two pairs of wings normally present. The forewings are modified into short smooth, veinless tegmina

A tegmen (plural: ''tegmina'') designates the modified leathery front wing on an insect particularly in the orders Dermaptera ( earwigs), Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets and similar families), Mantodea (praying mantis), Phasmatodea (stick an ...

. Hindwings are membranous

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. ...

and semicircular with veins

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated b ...

radiating outwards.

* ''Abdomen'': Cerci are unsegmented and resemble forceps

Forceps (plural forceps or considered a plural noun without a singular, often a pair of forceps; the Latin plural ''forcipes'' is no longer recorded in most dictionaries) are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Fo ...

. The ovipositor in females is reduced or absent.

The overwhelming majority of earwig species are in the former suborder Forficulina, grouped into nine families of 180 genera, including ''Forficula auricularia

''Forficula auricularia'', the common earwig or European earwig, is an omnivorous insect in the family Forficulidae. The European earwig survives in a variety of environments and is a common household insect in North America. The name ''earwig'' ...

'', the common European Earwig. Species within Forficulina are free-living, have functional wings and are not parasites. The cerci are unsegmented and modified into large, forceps-like structures.

The first epizoic

An epibiont (from the Ancient Greek meaning "living on top of") is an organism that lives on the surface of another living organism, called the basibiont ("living underneath"). The interaction between the two organisms is called epibiosis. An ep ...

species of earwig was discovered by a London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

taxidermist

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body via mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proc ...

on the body of a Malaysian hairless bulldog bat in 1909, then described by Karl Jordan. By the 1950s, the two suborders Arixeniina and Hemimerina had been added to Dermaptera. These were subsequently demoted to family Arixeniidae

Arixeniidae is a family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. Arixeniidae was formerly considered a suborder, Arixeniina, but was reduced in rank to family and included in the new suborder Neodermaptera.

Arixeniidae is represented by two gene ...

and superfamily Hemimeroidea (with sole family Hemimeridae

Hemimeridae is a family of earwigs in the suborder Neodermaptera. Hemimeridae was formerly considered a suborder, Hemimerina, but was reduced in rank to family and included in the new suborder Neodermaptera.

Hemimeridae is represented by two gen ...

), respectively. They are now grouped together with the former Forficulina in the new suborder Neodermaptera

Neodermaptera, sometimes called Catadermaptera,BioLib.cz

suborder Catadermaptera Steinmann, 1986 (retrieved 16 Se ...

.

Arixeniidae represents two genera, ''suborder Catadermaptera Steinmann, 1986 (retrieved 16 Se ...

Arixenia

''Arixenia'' is a genus of earwigs, one of only two genera in the family Arixeniidae, and contains two species.

See also

* Earwig

Earwigs make up the insect order Dermaptera. With about 2,000 species in 12 families, they are one of th ...

'' and '' Xeniaria'', with a total of five species in them. As with Hemimeridae, they are blind and wingless, with filiform segmented cerci. Hemimeridae are viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the ...

ectoparasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

, preferring the fur of African rodents in either '' Cricetomys'' or ''Beamys

''Beamys'' is a genus of rodent in the family Nesomyidae.

It contains the following species:

* Lesser hamster-rat (''Beamys hindei'')

* Greater hamster-rat

The greater hamster-rat, greater long-tailed pouched rat, or long-tailed pouched rat ( ...

'' genera. Hemimerina also has two genera, '' Hemimerus'' and '' Araeomerus'', with a total of 11 species.

Phylogeny

Dermaptera is relatively small compared to the other orders of

Dermaptera is relatively small compared to the other orders of Insecta

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs o ...

, with only about 2,000 species, 3 suborders and 15 families, including the extinct suborders Archidermaptera

Archidermaptera is an extinct suborder of earwigs in the order Dermaptera. It is one of two extinct suborders of earwigs, and contains two families (Protodiplatyidae and Dermapteridae) known only from Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous fossils.Fa ...

and Eodermaptera with their extinct families Protodiplatyidae, Dermapteridae, Semenoviolidae, and Turanodermatidae

Turanodermatidae is an extinct family of earwigs in the order Dermaptera

Earwigs make up the insect order Dermaptera. With about 2,000 species in 12 families, they are one of the smaller insect orders. Earwigs have characteristic cerci, ...

. The phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spe ...

of the Dermaptera is still debated. The extant Dermaptera appear to be monophyletic and there is support for the monophyly of the families Forficulidae, Chelisochidae, Labiduridae and Anisolabididae, however evidence has supported the conclusion that the former suborder Forficulina was paraphyletic through the exclusion of Hemimerina and Arixeniina which should instead be nested within the Forficulina. Thus, these former suborders were eliminated in the most recent higher classification.

Relationship with humans

Earwigs are fairly abundant and are found in many areas around the world. There is no evidence that they transmit diseases to humans or other animals. Their pincers are commonly believed to be dangerous, but in reality, even the curved pincers of males cause little or no harm to humans. Earwigs have been rarely known to crawl into the ears of humans, but they do not lay eggs inside the human body or human brain as is often claimed. There is a debate whether earwigs are harmful or beneficial to crops, as they eat both the foliage and the insects eating such foliage, such asaphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A t ...

s, though it would take a large population to do considerable damage. The common earwig eats a wide variety of plants, and also a wide variety of foliage, including the leaves and petals. They have been known to cause economic losses in fruit and vegetable crops. Some examples are the flowers, hops, red raspberries, and corn crops in Germany, and in the south of France, earwigs have been observed feeding on peach

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, non-f ...

es and apricots. The earwigs attacked mature plants and made cup-shaped bite marks in diameter.

In literature and folklore

* One of the primary characters of James Joyce's experimental novelFinnegans Wake

''Finnegans Wake'' is a novel by Irish writer James Joyce. It is well known for its experimental style and reputation as one of the most difficult works of fiction in the Western canon. It has been called "a work of fiction which combines a bod ...

is referred to by the initials "HCE," which primarily stand for "Humphrey Chadwick Earwicker," a reference to earwigs. Earwig imagery is found throughout the book, and also occurs in the author's Ulysses

Ulysses is one form of the Roman name for Odysseus, a hero in ancient Greek literature.

Ulysses may also refer to:

People

* Ulysses (given name), including a list of people with this name

Places in the United States

* Ulysses, Kansas

* Ulysse ...

in the Laestrygonians chapter.

* Oscar Cook wrote the short story (appearing in ''Switch On The Light'', April, 1931; ''A Century Of Creepy Stories'' 1934; ''Pan Horror 2'', 1960) ''Boomerang'', which was later adapted by Rod Serling for the Night Gallery

''Night Gallery'' is an American anthology television series that aired on NBC from December 16, 1970, to May 27, 1973, featuring stories of horror and the macabre. Rod Serling, who had gained fame from an earlier series, ''The Twilight Zone ...

TV-series episode, ''The Caterpillar''. It tells the tale of the use of an earwig as a murder instrument applied by a man obsessed with the wife of an associate.

* Robert Herrick in ''Hesperides'' describes a feast attended by Queen Titania through writing: "Beards of mice, a newt's stew'd thigh, A bloated Earwig and a fly".

* Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 – 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humorist, best known for poems such as " The Bridge of Sighs" and " The Song of the Shirt". Hood wrote regularly for ''The London Magazine'', '' Athenaeum'', and ''Punch' ...

discusses the myth of earwigs finding shelter in the human ear in the poem "Love Lane" by saying the following: 'Tis vain to talk of hopes and fears, / And hope the least reply to wing, / From any maid that stops her ears / In dread of earwigs creeping in!"

* In some parts of rural England the earwig is called "battle-twig", which is present in Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem ''The Spinster's Sweet-Arts'': 'Twur as bad as battle-twig 'ere i' my oan blue chamber to me."

* In some regions of Japan, earwigs are called "Chinpo-Basami" or "Chinpo-Kiri", which means "penis cutter". Kenta Takada, a Japanese cultural entomologist, has inferred that these names may be derived from the fact that earwigs were seen around old Japanese-style toilets.

*In Roald Dahl's children's book ''George's Marvellous Medicine

''George's Marvellous Medicine'' (known as ''George's Marvelous Medicine'' in the US) is a book written by Roald Dahl and illustrated by Quentin Blake. First published by Jonathan Cape in 1981, it features George Kranky, an eight-year-old boy ...

'', George's Grandma encourages him to eat unwashed celery with beetles and earwigs still on them. A big fat earwig is very tasty,' Grandma said, licking her lips. 'But you've got to be very quick, my dear, when you put one of those in your mouth. It has a pair of sharp nippers on its back end and if it grabs your tongue with those, it never lets go. So you've got to bite the earwig first, chop chop, before it bites you.

References

External links

Earwig Research Center

by Fabian Haas, Heilbronn

Dermaptera Species File

by Heidi Hopkins, Michael D. Maehr, Fabian Haas, and Lesley S. Deem

on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures website * Langston RL & JA Powell (1975

The earwigs of California (Order Dermaptera)

Bulletin of the California Insect Survey. 20

Earwigs

from What's That Bug? {{DEFAULTSORT:Earwig Rhaetian first appearances Extant Late Triassic first appearances Exopterygota Polyneoptera