Early life of Plato on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

* For her part, Debra Nails asserts that the philosopher was born in 424/423 BC. Plato's birthplace is also disputed. Diogenes Laërtius states that Plato "was born, according to some writers, in Aegina in the house of Phidiades the son of Thales". Diogenes mentions as one of his sources the ''Universal History'' of Favorinus. According to Favorinus, Ariston and his family were sent by Athens to settle as

* Thucydides, 8.92 Therefore, Nails concludes that "perhaps Ariston was a cleruch, perhaps he went to Aegina in 431, and perhaps Plato was born on Aegina, but none of this enables a precise dating of Ariston's death (or Plato's birth)". Aegina is regarded as Plato's place of birth by Suda as well.

* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 46 Codrus himself was a

* A.E. Taylor, ''Plato'', xiv

* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 47 Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; these were two sons, Adeimantus and

2.368a

br>* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 47 Nevertheless, in his ''

* A.E. Taylor, ''Plato'', xiv When Ariston died, Athenian law forbade the legal independence of women, and, therefore Perictione was given to marriage to

158a

br>* D. Nails, "Perictione", 53 who had served many times as an ambassador to the Persian court and was a friend of

158a

br>* Plutarch, ''Pericles'', IV Pyrilampes had a son from a previous marriage, Demos, who was famous for his beauty. Perictione gave birth to Pyrilampes' second son, Antiphon, the half-brother of Plato, who appears in '' Parmenides'', where he is said to have given up philosophy, in order to devote most of his time to horses.Plato, ''Parmenides''

126c

/ref> Thus Plato was reared in a household of at least six children, where he was number five: a stepbrother, a sister, two brothers and a half-brother.D. Nails, ''The Life of Plato of Athens'', 4 In contrast to his reticence about himself, Plato used to introduce his distinguished relatives into his dialogues, or to mention them with some precision: Charmides has one named after him; Critias speaks in both '' Charmides'' and '' Protagoras''; Adeimantus and Glaucon take prominent parts in the '' Republic''.W. K. C. Guthrie, ''A History of Greek Philosophy'', IV, 11 From these and other references one can reconstruct his

For the suggestion that Plato's name being ''Aristocles'' was a fancy of the Hellenistic age, see L. Tarán, ''Plato's Alleged Epitaph'', 61

* Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 1

* Another legend related that, while he was sleeping as an infant on

6.503c

br>* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 47 According to Diogenes, Plato's education, like any other Athenian boy's, was physical as well as mental; he was instructed in grammar (that is, reading and writing), music, painting, and

* W. Smith, ''Plato'', 393 He excelled so much in physical exercises that

1.987a

/ref> According to the ancient writers, there was a tradition that Plato's favorite employment in his youthful years was

* P. Murray, ''Introduction'', 13

* D. Nails, ''The Life of Plato of Athens'', 2

324c

/ref> He was actually invited by the regime of the Thirty Tyrants (Critias and Charmides were among their leaders) to join the administration, but he held back; he hoped that under the new leadership the city would return to justice, but he was soon repelled by the violent acts of the regime.Plato (?), ''Seventh Letter''

324d

/ref> He was particularly disappointed, when the Thirty attempted to implicate Socrates in their seizure of the democratic general

324e

/ref> In 403 BC, the democracy was restored after the regrouping of the democrats in exile, who entered the city through the

325c

/ref> In 399 BC, Plato and other Socratic men took temporary refuge at Megara with

Latin Library

'. * ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * . ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * , I, ''See original text i

Latin library

'. * . * . See original text i

Perseus program

* ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * . See original text i

Perseus program

* ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * See original text i

Perseus program

* , V, VIII. ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * See original text i

Perseus program

* Xenophon, ''

Perseus program

'.

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

( grc, Πλάτων, ''Plátōn'', "wide, broad-shouldered"; c. 428/427 – c. 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

philosopher, the second of the trio of ancient Greeks including Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

said to have laid the philosophical foundations of Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

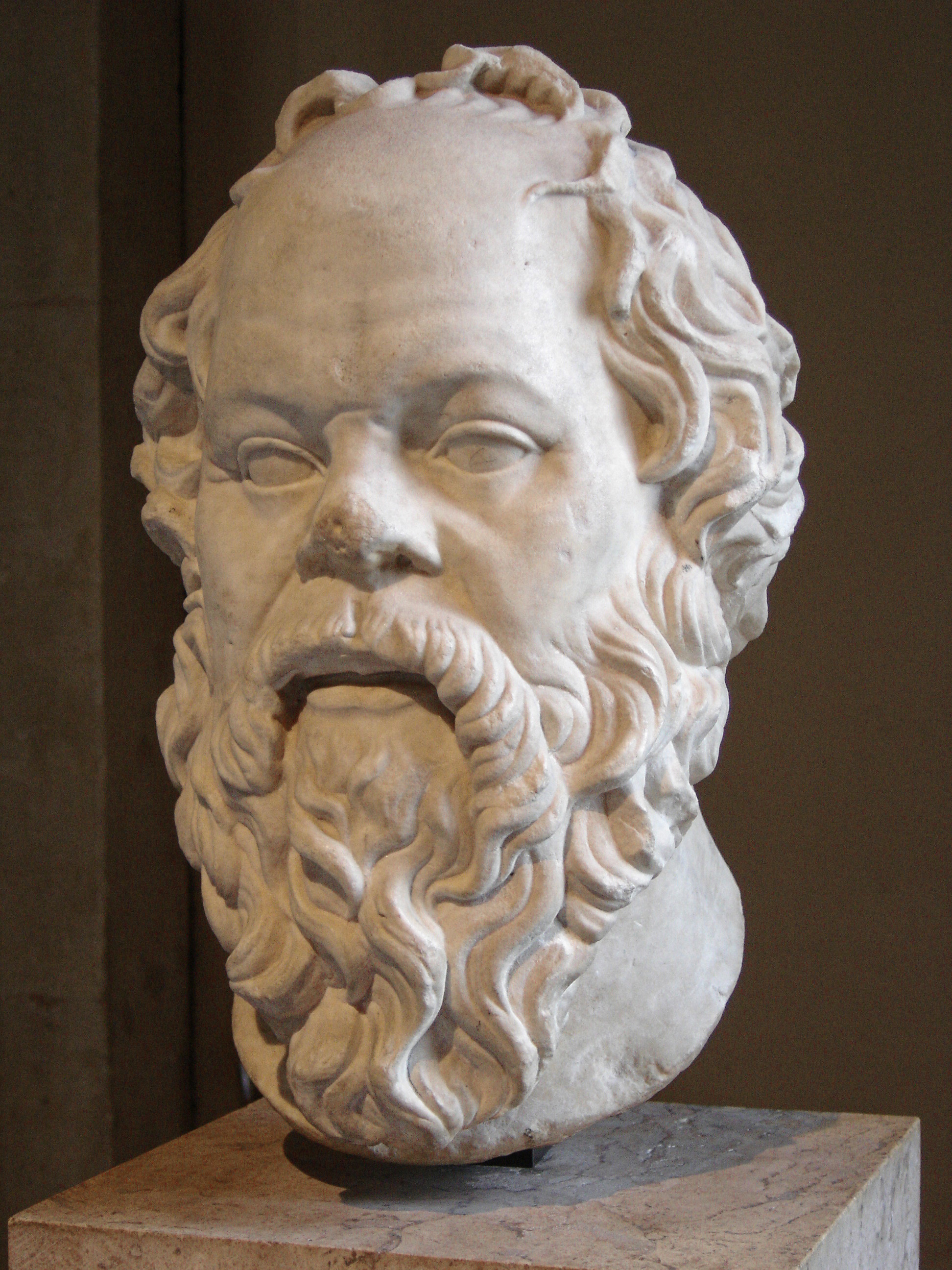

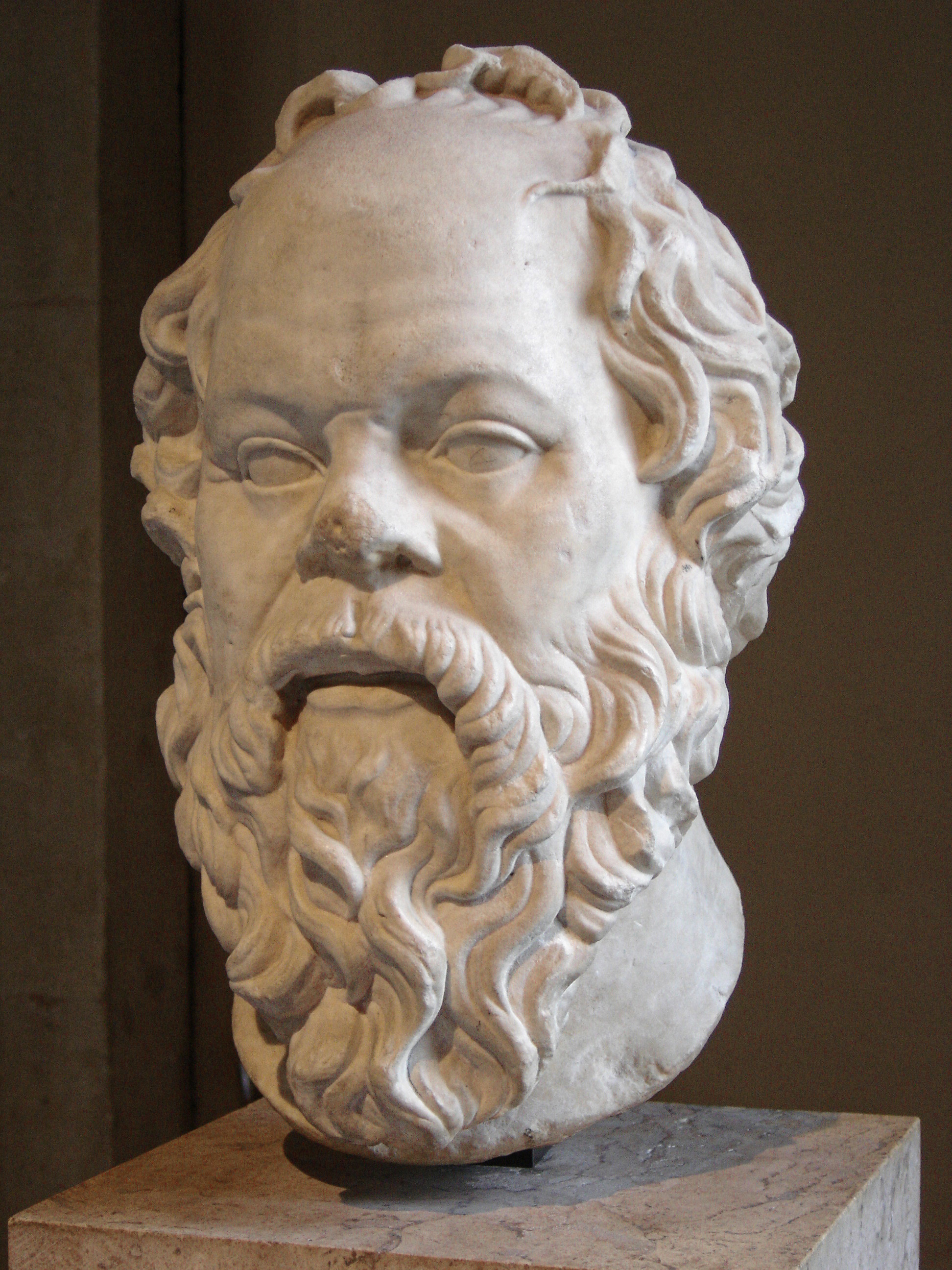

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

.

Little can be known about Plato's early life and education due to the very limited accounts. Plato came from one of the wealthiest and most politically active families in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

. Ancient sources describe him as a bright though modest boy who excelled in his studies. His father contributed everything necessary to give to his son a good education, and Plato therefore must have been instructed in grammar, music, gymnastics and philosophy by some of the most distinguished teachers of his era.

Birthdate and birthplace

The specific birthdate of Plato is not known. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars estimate that Plato was born between 428 and 427 BC. The grammarianApollodorus of Athens

Apollodorus of Athens ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος, ''Apollodoros ho Athenaios''; c. 180 BC – after 120 BC) son of Asclepiades, was a Greek scholar, historian, and grammarian. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon, P ...

argues in his ''Chronicles'' that Plato was born in the first year of the eighty-eighth Olympiad (427 BC), on the seventh day of the month Thargelion; according to this tradition the god Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

was born this day.Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 2 According to another biographer of him, Neanthes, Plato was eighty-four years of age at his death.Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 3 If we accept Neanthes' version, Plato was younger than Isocrates by six years, and therefore he was born in the second year of the 87th Olympiad

An olympiad ( el, Ὀλυμπιάς, ''Olympiás'') is a period of four years, particularly those associated with the ancient and modern Olympic Games.

Although the ancient Olympics were established during Greece's Archaic Era, it was not unti ...

, the year Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelo ...

died (429 BC).

The ''Chronicle'' of Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

names the fourth year of the 89th Olympiad as Plato's, when Stratocles was archon, while the ''Alexandrian Chronicle'' mentions the eighty-ninth Olympiad, in the archonship of Isarchus.W. G. Tennemann, ''Life of Plato'', 315 According to Suda, Plato was born in Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and ...

in the 88th Olympiad amid the preliminaries of the Peloponnesian war, and he lived 82 years. Sir Thomas Browne also believes that Plato was born in the 88th Olympiad.T. Browne, ''Pseudodoxia Epidemica'', XII Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

Platonist

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at l ...

s celebrated Plato's birth on November 7. D. Nails, ''The Life of Plato of Athens'', 1 Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff

Enno Friedrich Wichard Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (22 December 1848 – 25 September 1931) was a German classical philologist. Wilamowitz, as he is known in scholarly circles, was a renowned authority on Ancient Greece and its literature ...

estimates that Plato was born when Diotimos was archon eponymous, namely between July 29 428 BC and July 24 427 BC.U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 46 Greek philologist Ioannis Kalitsounakis believes that the philosopher was born on May 26 or 27, 427 BC, while Jonathan Barnes

Jonathan Barnes, FBA (born 26 December 1942 in Wenlock, Shropshire) is an English scholar of Aristotelian and ancient philosophy.

Education and career

He was educated at the City of London School and Balliol College, Oxford University.

He t ...

regards 428 BC as year of Plato's birth.* For her part, Debra Nails asserts that the philosopher was born in 424/423 BC. Plato's birthplace is also disputed. Diogenes Laërtius states that Plato "was born, according to some writers, in Aegina in the house of Phidiades the son of Thales". Diogenes mentions as one of his sources the ''Universal History'' of Favorinus. According to Favorinus, Ariston and his family were sent by Athens to settle as

cleruchs

A cleruchy (, ''klēroukhia'') in Classical Greece, was a specialized type of colony established by Athens. The term comes from the Greek word , ''klērouchos'', literally "lot-holder".

History

Normally, Greek colonies were politically independen ...

(colonists retaining their Athenian citizenship), on the island of Aegina, from which they were expelled by the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

ns after Plato's birth there. Nails points out, however, that there is no record of any Spartan expulsion of Athenians from Aegina between 431 and 411 BC.D. Nails, "Ariston", 54 On the other hand, at the Peace of Nicias

The Peace of Nicias was a peace treaty signed between the Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta in March 421 BC that ended the first half of the Peloponnesian War.

In 425 BC, the Spartans had lost the battles of Pylos and Sphacteria, a severe ...

, Aegina was silently left under Athens control, and it was not until the summer of 411 that the Spartans overran the island.Thucydides, 5.18* Thucydides, 8.92 Therefore, Nails concludes that "perhaps Ariston was a cleruch, perhaps he went to Aegina in 431, and perhaps Plato was born on Aegina, but none of this enables a precise dating of Ariston's death (or Plato's birth)". Aegina is regarded as Plato's place of birth by Suda as well.

Family

Plato's father was Ariston, of thedeme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside seem to have existed in the 6th century BC and ear ...

of Colytus. According to a tradition, reported by Diogenes Laërtius but disputed by Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Ariston traced his descent from the king of Athens

Before the Athenian democracy, the tyrants, and the Archons, the city-state of Athens was ruled by kings. Most of these are probably mythical or only semi-historical. The following lists contain the chronological order of the title King of Athens ( ...

, Codrus

Codrus (; ; Greek: , ''Kódros'') was the last of the semi-mythical Kings of Athens (r. ca 1089– 1068 BC). He was an ancient exemplar of patriotism and self-sacrifice. He was succeeded by his son Medon, who it is claimed ruled not as king but ...

, and the king of Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; el, Μεσσηνία ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a ...

, Melanthus In Greek mythology, Melanthus ( grc, Μέλανθος) was a king of Messenia and son of Andropompus and Henioche.

Mythology

Melanthus was among the descendants of Neleus (the Neleidae) expelled from Messenia, by the descendants of Heracles ...

.Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 1* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 46 Codrus himself was a

demigod

A demigod or demigoddess is a part-human and part-divine offspring of a deity and a human, or a human or non-human creature that is accorded divine status after death, or someone who has attained the "divine spark" ( spiritual enlightenment). A ...

fathered by the God of the sea Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ...

. These claims are not however exploited in the philosopher's dialogues.D. Nails, "Ariston", 53 Plato's mother was Perictione Perictione ( grc-gre, Περικτιόνη ''Periktiónē''; fl. 5th century BC) was the mother of the Greek philosopher Plato.

She was a descendant of Solon, the Athenian lawgiver. Her illustrious family goes back to Dropides, archon of the yea ...

, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian lawmaker

A legislator (also known as a deputy or lawmaker) is a person who writes and passes laws, especially someone who is a member of a legislature. Legislators are often elected by the people of the state. Legislatures may be supra-national (for ex ...

and lyric poet

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

. Solon's heritage can be traced back to Dropides, Archon of the year 644 b.c. Perictione was sister of Charmides and cousin of Critias

Critias (; grc-gre, Κριτίας, ''Kritias''; c. 460 – 403 BC) was an ancient Athenian political figure and author. Born in Athens, Critias was the son of Callaeschrus and a first cousin of Plato's mother Perictione. He became a leading ...

, both prominent figures of the Thirty Tyrants, the brief oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

, which followed on the collapse of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian war (404–403 BC).W. K. C. Guthrie, ''A History of Greek Philosophy, IV, 10* A.E. Taylor, ''Plato'', xiv

* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 47 Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; these were two sons, Adeimantus and

Glaucon

Glaucon (; el, Γλαύκων; c. 445 BC – 4th century BC), son of Ariston, was an ancient Athenian and Plato's older brother. He is primarily known as a major conversant with Socrates in the '' Republic''. He is also referenced briefly in ...

, and a daughter, Potone, the mother of Speusippus

Speusippus (; grc-gre, Σπεύσιππος; c. 408 – 339/8 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher. Speusippus was Plato's nephew by his sister Potone. After Plato's death, c. 348 BC, Speusippus inherited the Academy, near age 60, and remaine ...

(the nephew and successor of Plato as head of his philosophical Academy). According to the '' Republic'', Adeimantus and Glaucon were older than Plato; the two brothers distinguished themselves in the Battle of Megara

The Battle of Megara was fought in 424 BC between Athens and Megara, an ally of Sparta. The Athenians were victorious.

Megara was in the country of Megarid, between central Greece and the Peloponnese. Megara, an ally of Sparta, consisted of fa ...

, when Plato could not have been more than 5 years old.Plato, ''Republic''2.368a

br>* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 47 Nevertheless, in his ''

Memorabilia

A souvenir (), memento, keepsake, or token of remembrance is an object a person acquires for the memories the owner associates with it. A souvenir can be any object that can be collected or purchased and transported home by the traveler as a m ...

'', Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

presents Glaucon as younger than Plato.

Ariston appears to have died in Plato's childhood, although the precise dating of his death is difficult.D. Nails, "Ariston", 53* A.E. Taylor, ''Plato'', xiv When Ariston died, Athenian law forbade the legal independence of women, and, therefore Perictione was given to marriage to

Pyrilampes Pyrilampes ( grc-gre, Πυριλάμπης) was an ancient Athenian politician and stepfather of the philosopher Plato. His dates of birth and death are unknown, but Debra Nails estimates he must have been born after 480 BC and died before 413 BC ...

, her mother's brother (Plato himself calls him the uncle of Charmides),Plato, ''Charmides''158a

br>* D. Nails, "Perictione", 53 who had served many times as an ambassador to the Persian court and was a friend of

Pericles

Pericles (; grc-gre, Περικλῆς; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek politician and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Pelo ...

, the leader of the democratic faction in Athens.Plato, ''Charmides''158a

br>* Plutarch, ''Pericles'', IV Pyrilampes had a son from a previous marriage, Demos, who was famous for his beauty. Perictione gave birth to Pyrilampes' second son, Antiphon, the half-brother of Plato, who appears in '' Parmenides'', where he is said to have given up philosophy, in order to devote most of his time to horses.Plato, ''Parmenides''

126c

/ref> Thus Plato was reared in a household of at least six children, where he was number five: a stepbrother, a sister, two brothers and a half-brother.D. Nails, ''The Life of Plato of Athens'', 4 In contrast to his reticence about himself, Plato used to introduce his distinguished relatives into his dialogues, or to mention them with some precision: Charmides has one named after him; Critias speaks in both '' Charmides'' and '' Protagoras''; Adeimantus and Glaucon take prominent parts in the '' Republic''.W. K. C. Guthrie, ''A History of Greek Philosophy'', IV, 11 From these and other references one can reconstruct his

family tree

A family tree, also called a genealogy or a pedigree chart, is a chart representing family relationships in a conventional tree structure. More detailed family trees, used in medicine and social work, are known as genograms.

Representations of ...

, and this suggests a considerable amount of family pride. According to John Burnet, "the opening scene of the ''Charmides'' is a glorification of the whole amilyconnection ... Plato's dialogues are not only a memorial to Socrates, but also the happier days of his own family".C.H. Kahn, ''Plato and the Socratic Dialogue'', 186

Family tree

''Note'': John Burnet gives Glaucon as Plato's grandfather. Diogenes Laërtius gives Aristocles as Plato's grandfather.Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 4Name

According to Diogenes, the philosopher was named after his grandfather Aristocles, but hiswrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat ...

coach, Ariston of Argos, dubbed him "Platon", meaning "broad" on account of his robust figure. Diogenes mentions three sources for the name of Plato (Alexander Polyhistor

Lucius Cornelius Alexander Polyhistor ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Πολυΐστωρ; flourished in the first half of the 1st century BC; also called Alexander of Miletus) was a Greek scholar who was enslaved by the Romans during the Mithri ...

, Neanthes of Cyzicus Neanthes of Cyzicus (; el, Νεάνθης ὁ Κυζικηνός) was a Greek historian and rhetorician of Cyzicus in Anatolia living in the fourth and third centuries BC.

Biography

Neanthes was a pupil of Philiscus of Miletus ("who is reasonably ...

and unnamed sources), according to which the philosopher derived his name from the breadth (πλατύτης, ''platytēs'') of his eloquence, or else because he was very wide (πλατύς, ''platýs'') across the forehead. All these sources of Diogenes date from the Alexandrian period

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

of biography which got much of its information from its Peripatetic

Peripatetic may refer to:

*Peripatetic school, a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece

*Peripatetic axiom

* Peripatetic minority, a mobile population moving among settled populations offering a craft or trade.

*Peripatetic Jats

There are several ...

forerunners.A. Notopoulos, ''The Name of Plato'', 135 Recent scholars have disputed Diogenes, and argued that ''Plato'' was the original name of the philosopher, and that the legend about his name being ''Aristocles'' originated in the Hellenistic age

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

. W. K. C. Guthrie points out that ''Ρlato'' was a common name in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

, of which 31 instances are known at Athens alone.For the use of the name ''Plato'' in Athens, see W. K. C. Guthrie, ''A History of Greek Philosophy'', IV, 10For the suggestion that Plato's name being ''Aristocles'' was a fancy of the Hellenistic age, see L. Tarán, ''Plato's Alleged Epitaph'', 61

Legends

According to certain fabulous reports of ancient writers, Plato's mother became pregnant from a divine vision: Ariston tried to force his attentions on Perictione, but failed of his purpose; then the ancient Greek godApollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

appeared to him in a vision, and, as a result of it, Ariston left Perictione unmolested. When she had given birth to Plato, only then did her husband lie with her.Apuleius, ''De Dogmate Platonis'', 1* Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 1

* Another legend related that, while he was sleeping as an infant on

Mount Hymettus

Hymettus (), also Hymettos (; el, Υμηττός, translit=Ymittós, pronounced ), is a mountain range in the Athens area of Attica, East Central Greece. It is also colloquially known as ''Trellós'' (crazy) or ''Trellóvouno'' (crazy mountain) ...

in a bower of myrtles (his parents were sacrificing to the Muses and Nymphs

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ...

), bees had settled on the lips of Plato; an augury of the sweetness of style in which he would discourse philosophy.

Education

Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern- ...

informs us that Speusippus praised Plato's quickness of mind and modesty as a boy, and the "first fruits of his youth infused with hard work and love of study".Apuleius, ''De Dogmate Platonis'', 2 Later Plato himself would characterize as gifts of nature the facility in learning, the memory, the sagacity, the quickness of apprehension and their accompaniments, the youthful spirit and the magnificence in soul.Plato, ''Republic''6.503c

br>* U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, ''Plato'', 47 According to Diogenes, Plato's education, like any other Athenian boy's, was physical as well as mental; he was instructed in grammar (that is, reading and writing), music, painting, and

gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, s ...

by the most distinguished teachers of his time.Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 4–5* W. Smith, ''Plato'', 393 He excelled so much in physical exercises that

Dicaearchus

Dicaearchus of Messana (; grc-gre, Δικαίαρχος ''Dikaiarkhos''; ), also written Dikaiarchos (), was a Greek philosopher, geographer and author. Dicaearchus was a student of Aristotle in the Lyceum. Very little of his work remains exta ...

went so far as to say, in the first volume of his ''Lives'', that Plato wrestled at the Isthmian games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ancient Greek: Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year b ...

and did extremely well and was well known.Diogenes Laërtius, iii. 5 Apuleius argues that the philosopher went also into a public contest at the Pythian games

The Pythian Games ( grc-gre, Πύθια;) were one of the four Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece. They were held in honour of Apollo at his sanctuary at Delphi every four years, two years after the Olympic Games, and between each Nemean and ...

. Plato had also attended courses of philosophy; before meeting Socrates, he first became acquainted with Cratylus (a disciple of Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrot ...

, a prominent pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

Greek philosopher) and the Heraclitean doctrines.Aristotle, ''Metaphysics''1.987a

/ref> According to the ancient writers, there was a tradition that Plato's favorite employment in his youthful years was

poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

. He wrote poems, dithyrambs at first, and afterwards lyric poem

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

s and tragedies (a tetralogy

A tetralogy (from Greek τετρα- '' tetra-'', "four" and -λογία ''-logia'', "discourse") is a compound work that is made up of four distinct works. The name comes from the Attic theater, in which a tetralogy was a group of three tragedie ...

), but abandoned his early passion and burnt his poems when he met Socrates and turned to philosophy. There was also a story that on the day Plato was entrusted to him, Socrates said that a swan had been delivered to him. There are also some epigrams attributed to Plato, but these are now thought by some scholars to be spurious.A.E. Taylor, ''Plato'', 554 Modern scholars now believe that Plato was probably a young boy when he became acquainted with Socrates. This assessment is based on the fact that Critias and Charmides, two close relatives of Plato, were both friends of Socrates.* P. Murray, ''Introduction'', 13

* D. Nails, ''The Life of Plato of Athens'', 2

Public affairs

According to theSeventh Letter

The ''Seventh Letter of Plato'' is an epistle that tradition has ascribed to Plato. It is by far the longest of the epistles of Plato and gives an autobiographical account of his activities in Sicily as part of the intrigues between Dion and ...

, whose authenticity has been disputed, as Plato came of age, he imagined for himself a life in public affairs.Plato (?), ''Seventh Letter''324c

/ref> He was actually invited by the regime of the Thirty Tyrants (Critias and Charmides were among their leaders) to join the administration, but he held back; he hoped that under the new leadership the city would return to justice, but he was soon repelled by the violent acts of the regime.Plato (?), ''Seventh Letter''

324d

/ref> He was particularly disappointed, when the Thirty attempted to implicate Socrates in their seizure of the democratic general

Leon of Salamis

Leon of Salamis (; grc-gre, Λέων) was a historical figure, mentioned in Plato's '' Apology'', Xenophon's '' Hellenica'' and Andocides' ''On the Mysteries'' (1.94). This Leon may also be the renowned Athenian general Leon of the Peloponnesia ...

for summary execution.Plato (?), ''Seventh Letter''324e

/ref> In 403 BC, the democracy was restored after the regrouping of the democrats in exile, who entered the city through the

Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saron ...

and met the forces of the Thirty at the Battle of Munychia

The Battle of Munychia was fought between Athenians exiled by the oligarchic government of the Thirty Tyrants and the forces of that government, supported by a Spartan garrison. In the battle, a substantially superior force composed of the Sparta ...

, where both Critias and Charmides were killed.Xenophon, ''Hellenica'', 2:4:10-19 In 401 BC the restored democrats raided Eleusis and killed the remaining oligarchic supporters, suspecting them of hiring mercenaries.Xenophon, ''Hellenica'', 2:4:43 After the overthrow of the Thirty, Plato's desire to become politically active was rekindled, but Socrates' condemnation to death put an end to his plans. Plato led his voyage through Sicily, Egypt, and Italy guided by this question. Plato (?), ''Seventh Letter''325c

/ref> In 399 BC, Plato and other Socratic men took temporary refuge at Megara with

Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of ...

, founder of the Megarian school of philosophy.

According to Diogenes Laërtius, throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse. Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysius. During this first trip Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but he was sold into slavery. Anniceris

Anniceris ( grc-gre, Ἀννίκερις; fl. 300 BC) was a Cyrenaic philosopher. He argued that pleasure is achieved through individual acts of gratification which are sought for the pleasure that they produce, but he also laid great emphasis on t ...

, a Cyrenaic

The Cyrenaics or Kyrenaics ( grc, Κυρηναϊκοί, Kyrēnaïkoí), were a sensual hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BCE, supposedly by Aristippus of Cyrene, although many of the principles of the school are belie ...

philosopher, subsequently bought Plato's freedom for twenty minas

Minas or MINAS may refer to:

People with the given name Minas

* Menas of Ethiopia (died 1563)

* Saint Menas (Minas, 285–309)

* Minias of Florence (Minas, Miniato, died 250)

* Minas Alozidis (born 1984), Greek hurdler

* Minas Avetisyan (1928� ...

, and sent him home. After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's ''Seventh Letter'', Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysius expelled Dion and kept Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse. Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and ruled Syracuse for a short time before being usurped by Calippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

Death

According to Seneca, Plato died at the age of 81 on the same day he was born.Seneca, Epistulae, VI, 58, 31: ''natali suo decessit et annum umum atque octogensimum''. The Suda indicates that he lived to 82 years, while Neanthes claims an age of 84.Diogenes Laërtius, ''Life of Plato'', II A variety of sources have given accounts of his death. One story, based on a mutilated manuscript, suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a youngThracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

girl played the flute to him. Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes Laërtius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian. According to Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

, Plato simply died in his sleep.

Notes

Citations

References

Primary sources (Greek and Roman)

*Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern- ...

, ''De Dogmate Platonis'', I. ''See original text iLatin Library

'. * ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * . ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * , I, ''See original text i

Latin library

'. * . * . See original text i

Perseus program

* ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * . See original text i

Perseus program

* ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * See original text i

Perseus program

* , V, VIII. ''See original text i

Perseus program

'. * See original text i

Perseus program

* Xenophon, ''

Memorabilia

A souvenir (), memento, keepsake, or token of remembrance is an object a person acquires for the memories the owner associates with it. A souvenir can be any object that can be collected or purchased and transported home by the traveler as a m ...

''. ''See original text iPerseus program

'.

Secondary sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Plato navbox PlatoPlato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

Ancient Aegina