Early life and career of Ulysses S. Grant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio on April 27, 1822. Point Pleasant was located in the southwestern corner of Ohio near

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio on April 27, 1822. Point Pleasant was located in the southwestern corner of Ohio near

Rising tensions with

Rising tensions with

''September 1846'' Grant's first battle experience came at the

Although Grant received promotions during the

Although Grant received promotions during the

At age 32, with no civilian vocation, Grant began to struggle through seven financially lean years and poverty. His father, Jesse, initially offered Grant a position in the Galena, Illinois branch of the tannery business, on condition that Julia and the children, for economic reasons, stay with her parents in Missouri, or Grant's in Kentucky. Ulysses and Julia were adamantly opposed to another separation, and declined the offer. In 1854, Grant farmed on his brother-in-law's property near St. Louis, using slaves owned by Julia's father, but it did not succeed. Two years later, Grant and family moved to a section of his father-in-law's farm; to give his family a home, built a house he called "Hardscrabble". Julia hated the rustic house, which she described as an "unattractive cabin". During this time, Grant also acquired a slave from Julia's father, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones. Having met with no success farming, the Grants left the farm when their fourth and final child was born in 1858. Grant freed his slave in 1859 instead of selling him, at a time when slaves commanded a high price and Grant needed money badly. For the next year, the family took a small house in St. Louis where he worked, again without success, with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs, as a bill collector. In 1860 Jesse offered him the job in his tannery in

At age 32, with no civilian vocation, Grant began to struggle through seven financially lean years and poverty. His father, Jesse, initially offered Grant a position in the Galena, Illinois branch of the tannery business, on condition that Julia and the children, for economic reasons, stay with her parents in Missouri, or Grant's in Kentucky. Ulysses and Julia were adamantly opposed to another separation, and declined the offer. In 1854, Grant farmed on his brother-in-law's property near St. Louis, using slaves owned by Julia's father, but it did not succeed. Two years later, Grant and family moved to a section of his father-in-law's farm; to give his family a home, built a house he called "Hardscrabble". Julia hated the rustic house, which she described as an "unattractive cabin". During this time, Grant also acquired a slave from Julia's father, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones. Having met with no success farming, the Grants left the farm when their fourth and final child was born in 1858. Grant freed his slave in 1859 instead of selling him, at a time when slaves commanded a high price and Grant needed money badly. For the next year, the family took a small house in St. Louis where he worked, again without success, with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs, as a bill collector. In 1860 Jesse offered him the job in his tannery in

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

was the first born son of Jesse Root Grant

Jesse Root Grant (January 23, 1794 – June 29, 1873) was an American farmer, tanner and successful leather merchant who owned tanneries and leather goods shops in several different states throughout his adult life. He is best known as the ...

and Hannah Simpson Grant. This article lends itself to the story of this future general's ancestry, birth, and early career in and out of the United States army from 1822 to 1861. Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio and he was educated in both private and public schools or academies and was later known to be an avid reader. Grant was raised as a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

, but uncommon for his time, he was not baptized or forced to attend church by his parents. Growing up in a middle-class family and supported by his father's tanneries, he sought a different career in the military. He was appointed to West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

by Ohio Congressman Thomas L. Hamer

Thomas Lyon Hamer (July 1800December 2, 1846) was a United States Democratic congressman and soldier.

Hamer was born in July 1800 in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a school teacher before being admitted to the bar in 1821. He was a ...

. It was Hamer who gave Grant the name ''Ulysses S. Grant'' when Grant entered West Point as a plebe in 1839. After four years at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, he was stationed in Missouri, where he met his future wife, Julia Dent. In 1846, Grant served in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, where he was brevetted for bravery. There he fought in Mexico and learned under two commanders, Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

and Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

. Upon his return to the United States, he married Julia and started a family.

After the war, Grant was assigned to posts in New York and Michigan before traveling West to a posting Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of th ...

at Fort Humboldt in present-day Northern California. On his journey to California by ship, Grant compassionately aided victims of a cholera epidemic while he was traveling through Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

, arriving in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

in 1853, during the California Gold Rush. Grant's tenure in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Tho ...

included the aftermath of the Cayuse War

The Cayuse War was an armed conflict that took place in the Northwestern United States from 1847 to 1855 between the Cayuse people of the region and the United States Government and local American settlers. Caused in part by the influx of disease ...

. Grant's various attempts at speculation ventures failed in his effort to support Julia and his family. While stationed at Fort Humboldt Grant became lonely and depressed and he began to drink. After accusations of drunkenness while on duty at Fort Humboldt, Grant was compelled to resign and returned to Missouri and his family. Six years of civilian life were difficult for Grant, as he had little aptitude for business or farming, and was devastated by the Panic of 1857. In 1859, the family moved again, to Galena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in and the county seat of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, with a population of 3,308 at the 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Galena Historic District. The c ...

, where Grant had a job as a clerk in his father's leather shop. He worked there until 1861, when the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

began.

Ancestry

Grant was ofEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and Ulster Scots ancestry; his immigrant ancestor Mathew Grant arrived with Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

from England in the 1630. Grant's paternal grandmother Suzanna Delano, of French origin, was the granddaughter of Jonathan Delano (1647–1720), 7th child of Philippe de La Noye (1602–1681). Philippe was descended from the illustrious House of Lannoy, and was one of the '' Fortunes passengers who landed at Plymouth in November 1621, joining the first settlers of the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

''. The offspring of the paternal uncle of Suzanna, Thomas Delano (born 1704), gave a few decades later another president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. His mother descended from Presbyterian immigrants from County Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an administrative division for local government but retai ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

(where the ancestral family home still stands in Ballygawley) to Bucks County, Pennsylvania

Bucks County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 646,538, making it the fourth-most populous county in Pennsylvania. Its county seat is Doylestown. The county is named after the English ...

.

Early life and family

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio on April 27, 1822. Point Pleasant was located in the southwestern corner of Ohio near

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio on April 27, 1822. Point Pleasant was located in the southwestern corner of Ohio near Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

. His father Jesse Root Grant

Jesse Root Grant (January 23, 1794 – June 29, 1873) was an American farmer, tanner and successful leather merchant who owned tanneries and leather goods shops in several different states throughout his adult life. He is best known as the ...

(1794–1873) was a self-reliant tanner and businessman, and his mother was Hannah (Simpson) Grant (1798–1883). Grant was Jesse's and Hannah's first child. Both Jessie and Hanna were natives of Pennsylvania. In the fall of 1823, the family moved to the village of Georgetown in Brown County, Ohio, where they had five more children.

At the age of five, young Grant began his formal education, starting at a subscription school and later was enrolled in two private schools. In the winter of 1836–1837, Grant was a student at Maysville Seminary, and in the autumn of 1838 he attended John Rankin's academy. Raised in a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

family devoid of religious pretentiousness, Grant prayed privately and was not an official member of the church. Unlike his younger siblings, Grant was never disciplined, baptized, or forced to attend church by his parents. One of his biographers suggests that Grant inherited a degree of introversion

The traits of extraversion (also spelled extroversion Retrieved 2018-02-21.) and introversion are a central dimension in some human personality theories. The terms ''introversion'' and ''extraversion'' were introduced into psychology by Carl ...

from his reserved, even "uncommonly detached" mother (she did not visit the White House during her son's presidency). At home, Grant assumed the duties which were expected of him as a young man, and they primarily included maintenance of the firewood supply; he thereby developed a noteworthy ability to work with, and control, horses which were in his charge, and he used it to provide transportation as a vocation during his youth.

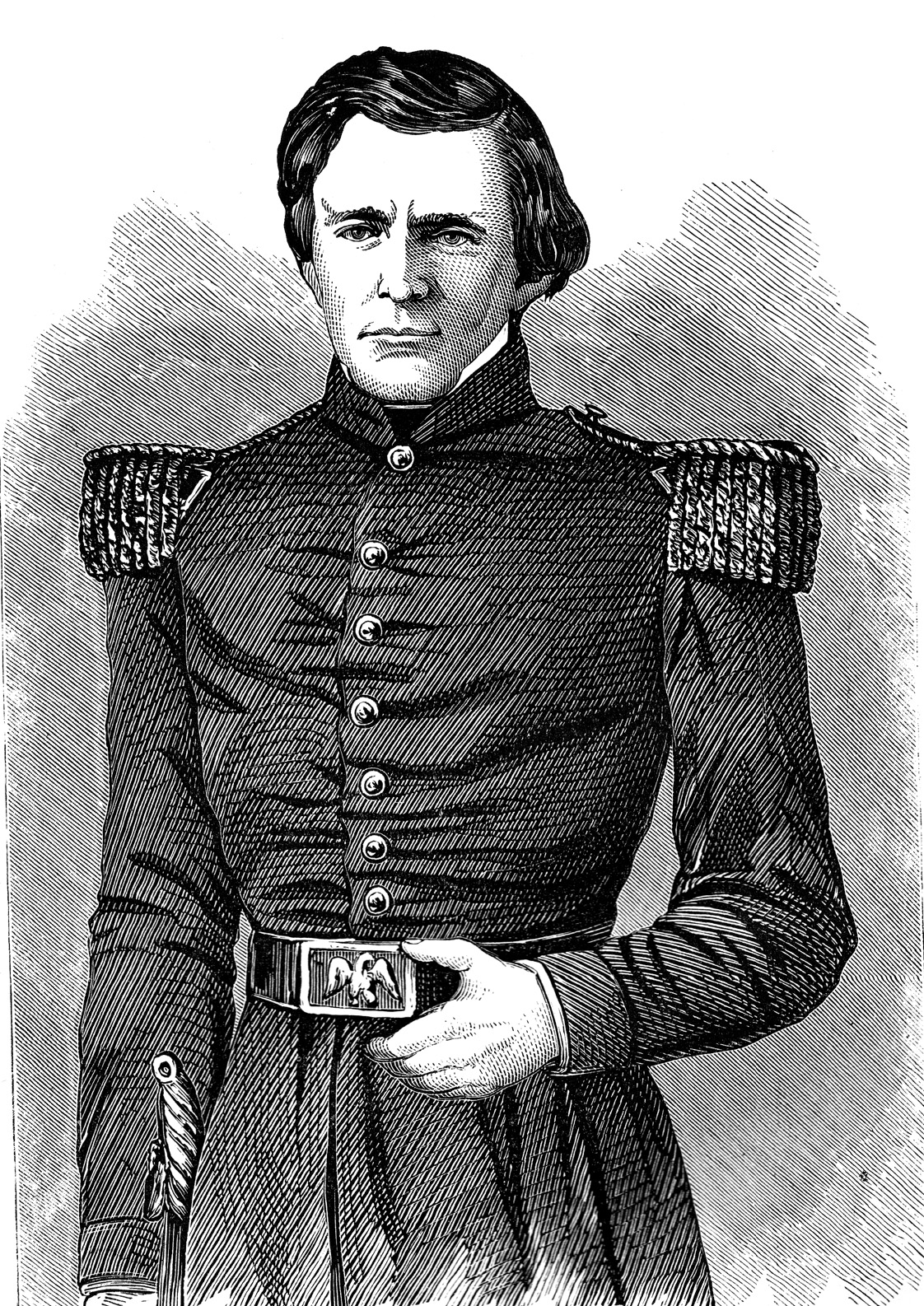

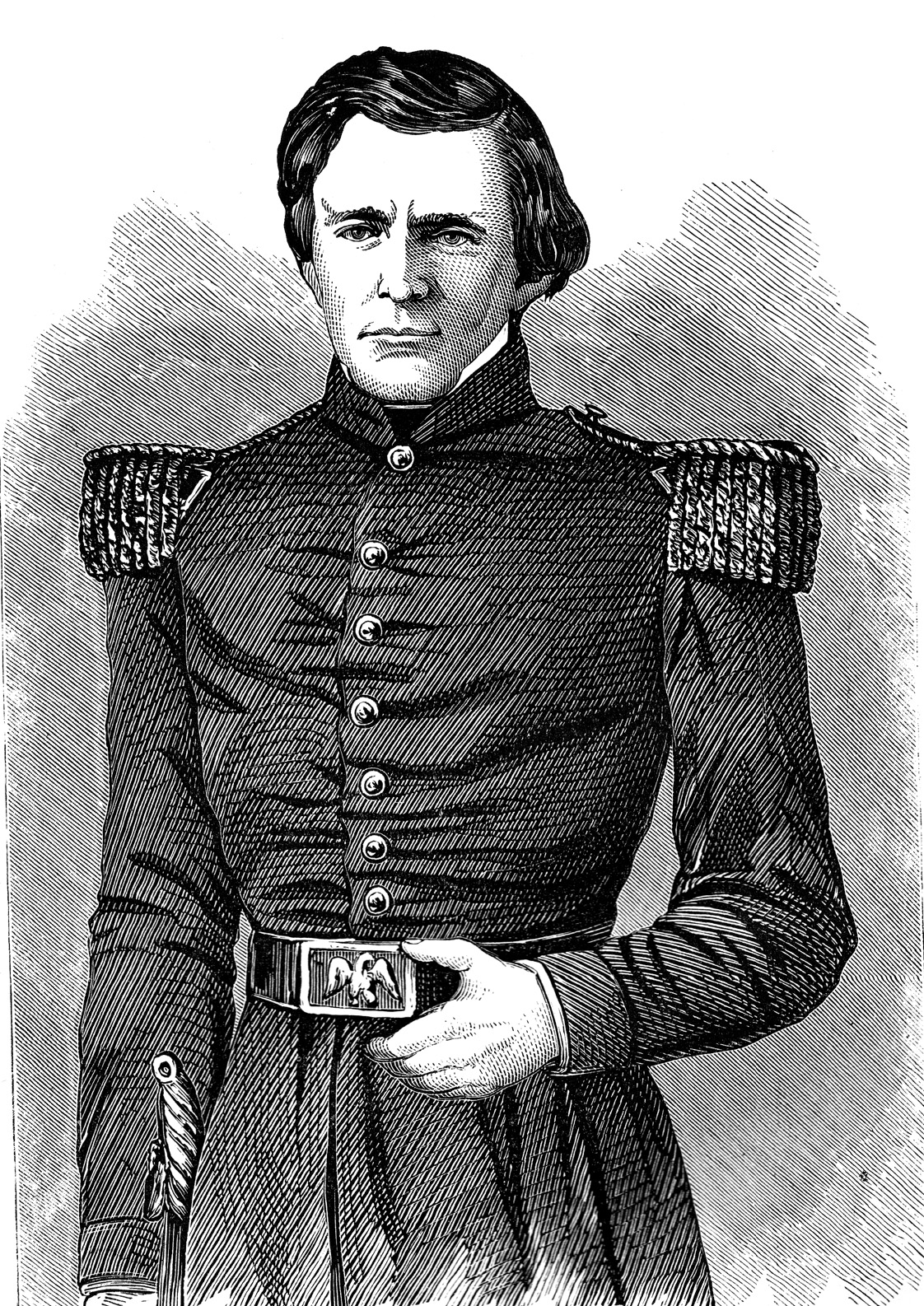

West Point (1839–1843)

180px, Congressman Thomas L. Hamer nominated Grant to West Point. At the age of 17, with the help of his father, Grant was nominated for a position at theUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

(USMA) at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

by Congressman Thomas L. Hamer

Thomas Lyon Hamer (July 1800December 2, 1846) was a United States Democratic congressman and soldier.

Hamer was born in July 1800 in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a school teacher before being admitted to the bar in 1821. He was a ...

. Hamer mistakenly nominated him as "Ulysses S. Grant of Ohio". At West Point, he adopted this name, but only with a middle initial. Among his army colleagues at the academy, his nickname became "Sam" because the initials "U.S." also stood for "Uncle Sam

Uncle Sam (which has the same initials as ''United States'') is a common national personification of the federal government of the United States or the country in general. Since the early 19th century, Uncle Sam has been a popular symbol of ...

". The "S", according to Grant, did not stand for anything, though Hamer had used it to abbreviate his mother's maiden name. The influence of Grant's family brought about the appointment to West Point, while Grant himself later recalled that "a military life had no charms for me". Grant, stood 5 feet 1 inches and weighed 117 lbs, when he entered West Point. Grant later said that he was lax in his studies, but he achieved excellent grades in mathematics and geology. Although Grant had a quiet nature, he did establish a few intimate friends at West Point, including Frederick Tracy Dent

Frederick Tracy Dent (December 17, 1820 – December 23, 1892) was an American general.

Early life

Dent was born on December 17, 1820 in White Haven, St. Louis County, Missouri. He was the son of Frederick Fayette Dent (1787–1873) and Ellen ...

and Rufus Ingalls

Rufus Ingalls (August 23, 1818 – January 15, 1893) was an American military general who served as the 16th Quartermaster General of the United States Army.

Early life and career

Ingalls was born in the village of Denmark in what is now Maine ...

. He joined a fraternity group known as the ''Twelve in One'', and was highly esteemed by his classmates. While not excelling scholastically, Grant studied under Romantic artist Robert Walter Weir

Robert Walter Weir (June 18, 1803 – May 1, 1889) was an American artist and educator and is considered a painter of the Hudson River School. Weir was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1829 and was an instructor at the United States M ...

and produced nine surviving artworks. He also established a reputation as a fearless and expert horseman, setting an equestrian high-jump record that stood almost 25 years. He graduated in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 29. Grant later recalled that his departure from West Point was of the happiest of his times and that he had intended to resign his commission after serving the minimum term of obligated duty. Despite his excellent horsemanship, he was not assigned to the cavalry, as assignments were determined by class rank, not aptitude. Grant was instead assigned as a regimental quartermaster, managing supplies and equipment in the 4th Infantry Regiment, with the rank of brevet second lieutenant.

First assignment (1843–1846)

Grant's first assignment after graduation took him to theJefferson Barracks

The Jefferson Barracks Military Post is located on the Mississippi River at Lemay, Missouri, south of St. Louis. It was an important and active U.S. Army installation from 1826 through 1946. It is the oldest operating U.S. military installation ...

near St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. After recuperating from an illness that left him thin and weak, Grant reported there in September 1843. It was the nation's largest military bastion in the West, commanded by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny. Grant was happy with his new commander, but still looked forward to the end of his military service. During this period, Grant had entertained the idea of becoming a mathematics teacher following his military service and spent much of his free time studying advanced algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. Grant spent some of his time in Missouri visiting the family of his West Point classmate, Frederick Dent, and getting to know Dent's sister, Julia

Julia is usually a feminine given name. It is a Latinate feminine form of the name Julio and Julius. (For further details on etymology, see the Wiktionary entry "Julius".) The given name ''Julia'' had been in use throughout Late Antiquity (e.g ...

; the two became secretly engaged in 1844.

Mexican–American War (1846–1848)

Rising tensions with

Rising tensions with Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

saw Grant's unit shifted to Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

that year as a part of the Army of Observation An army of observation is a military body whose purpose is to monitor a given area or enemy body in preparation for possible hostilities.

Some of the more notable armies of observation include:

* Third Reserve Army of Observation, a Russian army ta ...

under Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

. President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

ordered Taylor south to force the Mexican government to bargain over disputed territory between the United States and Mexico. Grant was in charge of securing hundreds of mules in preparation for the move south. Grant purchased the mules from Mexicans and had the mules branded, but the mules resisted being broken to wear a saddle and pack. Taylor took notice of Grant when Grant jumped in the water to help his men remove oyster beds so ships could advance from Aransas Bay to Corpus Christi, saying he wished he "had more officers like Grant." On March 11, 1846, Grant's Fourth Infantry, part of the Third Brigade, left Corpus Christi, first traveling west and then veering south. Having reached the Rio Grande, both the Mexican and American armies spied on each other. On April 25, the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

broke out when Mexican troops fired on and killed 11 American troops, commanded by Captain Seth Thornton, at Rancho de Carricitos. Defending Fort Texas on the Rio Grande, Taylor's army advanced on Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma.

200px, Monterey street fighting during the Mexican–American War.''September 1846'' Grant's first battle experience came at the

Battle of Palo Alto

The Battle of Palo Alto ( es, Batalla de Palo Alto) was the first major battle of the Mexican–American War and was fought on May 8, 1846, on disputed ground five miles (8 km) from the modern-day city of Brownsville, Texas. A force of so ...

against a substantial Mexican force that intended to flank and attack the American army. Grant did not panic and readied his 1822 musket when Taylor ordered two large artillery guns that fired on the Mexican army, who retreated. The next day the American army followed the retreating Mexican army to Resaca de la Palma. Not content with his responsibilities as a quartermaster, Grant made his way to the front lines to engage in the battle, and participated in the Battle of Resaca de la Palma

The Battle of Resaca de la Palma was one of the early engagements of the Mexican–American War, where the United States Army under General Zachary Taylor engaged the retreating forces of the Mexican ''Ejército del Norte'' ("Army of the North ...

. Grant led his company in a charge, capturing a Mexican officer and a few of his men, his first victory. Grant later realized the ground he gained and his captives had earlier been won in the battle.

Crossing the Rio Grande, the United States army continued its advance into Mexico. Thousands of American volunteers were incorporated into the U.S. military serving alongside the regular army, including Thomas Hamer, who had nominated Grant to West Point. Starting in September, Taylor and his Army of Invasion, moved south and engaged the Mexican army at the Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers an ...

. During the battle, Grant demonstrated his equestrian ability, carrying a dispatch through Monterrey's sniper-lined streets on horseback while mounted in one stirrup.

President James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

, who was wary of Taylor's growing popularity, divided his army, sending some troops (including Grant's unit) to form a new army under Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

. Scott's army landed at Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

and advanced toward Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital city, capital and primate city, largest city of Mexico, and the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North Amer ...

. The army met the Mexican forces at battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

outside Mexico City. At the latter battle, Grant dragged a howitzer into a church steeple to bombard nearby Mexican troops. Scott's army was soon into the city, and the Mexicans agreed to peace not long after.

In his memoirs, Grant indicated that he had learned extensively by closely observing the decisions and actions of his commanding officers, particularly admiring Taylor's methods, and in retrospect, he identified with Taylor's style. At the time, he felt that the war was a wrongful one because he believed that territorial gains were designed to spread slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

throughout the nation; writing in 1883, Grant said "I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day, I regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger nation against a weaker nation." He also opined that the later Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

was inflicted on the nation as punishment for its aggression in Mexico.

Marriage and family

On August 22, 1848, after a four-year engagement, Grant and Julia were married. He and Julia would go on to have four children:Frederick Dent Grant

Frederick Dent Grant (May 30, 1850 – April 12, 1912) was a soldier and United States minister to Austria-Hungary. Grant was the first son of General and President of the United States Ulysses S. Grant and Julia Grant. He was named after his ...

; Ulysses S. "Buck" Grant, Jr.; Ellen Wrenshall "Nellie" Grant; and Jesse Root Grant

Jesse Root Grant (January 23, 1794 – June 29, 1873) was an American farmer, tanner and successful leather merchant who owned tanneries and leather goods shops in several different states throughout his adult life. He is best known as the ...

. The couple corresponded during his service in Mexico; in one letter Julia shared with him a very pleasurable dream she had of him in a beard, which he was then sporting upon his return after the war.

Extended military service (1848–1854)

Although Grant received promotions during the

Although Grant received promotions during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, the peacetime army offered little for a young officer's advancement. Lieutenant Grant was assigned to several different posts over the ensuing six years. His first post-war assignments took him and Julia to Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

and Sackets Harbor, New York

Sackets Harbor (earlier spelled Sacketts Harbor) is a village in Jefferson County, New York, United States, on Lake Ontario. The population was 1,450 at the 2010 census. The village was named after land developer and owner Augustus Sackett, who ...

, the location that made them the happiest. In the spring of 1852, he traveled in to Washington, D.C. in a failed attempt to prevail upon the Congress to rescind an order that he, in his capacity as quartermaster, reimburse the military $1000 in losses incurred on his watch, for which he bore no personal guilt. He was sent west to Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of th ...

in the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. O ...

in 1852, initially landing in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

during the height of the California Gold Rush. Julia could not accompany him as she was eight months pregnant with their second child; further, a lieutenant's salary would not support a family on the frontier. The journey proved to be an ordeal due to transportation disruptions and an outbreak of cholera within the entourage while traveling overland through Panama. Grant made use of his organizational skills, arranging makeshift transportation and hospital facilities to take care of the sick. There were 150 4th Infantry fatalities including Grant's long-time friend John H. Gore. After Grant arrived in San Francisco he traveled to Fort Vancouver, continuing his service as quartermaster; the U.S. military was to keep the peace in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Tho ...

between settlers and Indians in the aftermath of the Cayuse War

The Cayuse War was an armed conflict that took place in the Northwestern United States from 1847 to 1855 between the Cayuse people of the region and the United States Government and local American settlers. Caused in part by the influx of disease ...

.

While on assignment out west and in an effort to supplement a military salary inadequate to support his family, Grant, assuming his work as quartermaster so equipped him, attempted but failed at several business ventures. The business failures in the West confirmed Jesse Grant's belief that his son had no head for business, creating frustration for both father and son. In at least one case Grant had even naively allowed himself to be swindled by a partner. These failures, along with the separation from his family, made for quite an unhappy soldier, husband and son. Rumors began to circulate that Grant was drinking in excess.

In the summer of 1853, Grant was promoted to captain, one of only fifty on active duty, and assigned to command Company F, 4th Infantry, at Fort Humboldt

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, on the northwest California coast. Without explanation, he shortly thereafter resigned from the army on July 31, 1854. The commanding officer at Fort Humboldt, brevet Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. Buchanan, a strict disciplinarian, had reports that Grant was intoxicated off duty while seated at the pay officer's table. Buchanan had previously warned Grant several times to stop his drinking. In lieu of a court-martial, Buchanan gave Grant an ultimatum to sign a drafted resignation letter. Grant resigned; the War Department stated on his record, "Nothing stands against his good name." Rumors, however, persisted in the regular army of Grant's intemperance. According to biographer McFeely, historians overwhelmingly agree that his intemperance at the time was a fact, though there are no eyewitness reports extant. Two of Grant's lieutenants corroborated this incident and Buchanan confirmed it to another officer in a conversation during the Civil War. Historian Jean Edward Smith

Jean Edward Smith (October 13, 1932 – September 1, 2019) was a biographer and the John Marshall Professor of Political Science at Marshall University. He was also professor emeritus at the University of Toronto after having served as professor ...

says, "The story rings true. Jean Edward Smith maintains Grant's resignation was too sudden to be a calculated decision. Historian William McFeely said that Grant left the army simply because he was "profoundly depressed" and that the evidence as to how much and how often Grant drank remains elusive. Buchanan never mentioned it again until asked about it during the Civil War. The effects and extent of Grant's drinking on his military and public career are debated by historians. Lyle Dorsett said Grant was an "alcoholic" but functioned amazingly well. William Farina maintains Grant's devotion to family kept him from drinking to excess and sinking into debt.

Years later after his resignation, Grant told John Eaton John Eaton may refer to:

* John Eaton (divine) (born 1575), English divine

* John Eaton (pirate) (fl. 1683–1686), English buccaneer

*Sir John Craig Eaton (1876–1922), Canadian businessman

* John Craig Eaton II (born 1937), Canadian businessman ...

, "the vice of intemperance had not a little to do with my decision to resign." Grant's father, again believing his son's only potential for success to be in the military, tried to get the Secretary of War to rescind the resignation, to no avail.

Civilian life, poverty, and struggles (1854–1861)

At age 32, with no civilian vocation, Grant began to struggle through seven financially lean years and poverty. His father, Jesse, initially offered Grant a position in the Galena, Illinois branch of the tannery business, on condition that Julia and the children, for economic reasons, stay with her parents in Missouri, or Grant's in Kentucky. Ulysses and Julia were adamantly opposed to another separation, and declined the offer. In 1854, Grant farmed on his brother-in-law's property near St. Louis, using slaves owned by Julia's father, but it did not succeed. Two years later, Grant and family moved to a section of his father-in-law's farm; to give his family a home, built a house he called "Hardscrabble". Julia hated the rustic house, which she described as an "unattractive cabin". During this time, Grant also acquired a slave from Julia's father, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones. Having met with no success farming, the Grants left the farm when their fourth and final child was born in 1858. Grant freed his slave in 1859 instead of selling him, at a time when slaves commanded a high price and Grant needed money badly. For the next year, the family took a small house in St. Louis where he worked, again without success, with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs, as a bill collector. In 1860 Jesse offered him the job in his tannery in

At age 32, with no civilian vocation, Grant began to struggle through seven financially lean years and poverty. His father, Jesse, initially offered Grant a position in the Galena, Illinois branch of the tannery business, on condition that Julia and the children, for economic reasons, stay with her parents in Missouri, or Grant's in Kentucky. Ulysses and Julia were adamantly opposed to another separation, and declined the offer. In 1854, Grant farmed on his brother-in-law's property near St. Louis, using slaves owned by Julia's father, but it did not succeed. Two years later, Grant and family moved to a section of his father-in-law's farm; to give his family a home, built a house he called "Hardscrabble". Julia hated the rustic house, which she described as an "unattractive cabin". During this time, Grant also acquired a slave from Julia's father, a thirty-five-year-old man named William Jones. Having met with no success farming, the Grants left the farm when their fourth and final child was born in 1858. Grant freed his slave in 1859 instead of selling him, at a time when slaves commanded a high price and Grant needed money badly. For the next year, the family took a small house in St. Louis where he worked, again without success, with Julia's cousin Harry Boggs, as a bill collector. In 1860 Jesse offered him the job in his tannery in Galena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in and the county seat of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, with a population of 3,308 at the 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Galena Historic District. The c ...

, without condition, which Ulysses accepted. The leather shop, "Grant & Perkins", sold harnesses, saddles, and other leather goods and purchased hides from farmers in the prosperous Galena area. He moved his family to Galena before that year.

Although unopposed to slavery at the time, Grant kept his political opinions private and never endorsed any candidate running for public office before the Civil War. His father-in-law was a prominent Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

in Missouri, a factor that helped derail Grant's bid to become county engineer in 1859, while his own father was an outspoken Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

. In the 1856 election, Grant cast his first presidential vote for the Democratic candidate James Buchanan, saying he was really voting against Fremont, the Republican candidate. In 1860, he favored the Democratic presidential candidate Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

over Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, and Lincoln over the alternate Democratic candidate, John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

. Lacking the residency requirements in Illinois at the time, he could not vote. By August 1863, during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, after the fall of Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

, Grant's political sympathies fully coincided with the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

' aggressive prosecution of the war and for the abolition of slavery.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * {{cite book , title=American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant , last=White , first=Ronald C. , author-link = Ronald C. White, publisher=Random House Publishing Group , year=2016 , isbn=978-1-5883-6992-5 , url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TPNRCwAAQBAJ Ulysses S. Grant Grant, Ulysses S Grant, Ulysses S Grant, Ulysses