Dwight L. Moody on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dwight Lyman Moody (February 5, 1837 – December 26, 1899), also known as D. L. Moody, was an American

D. L. Moody "could not conscientiously enlist" in the Union Army during the Civil War, later describing himself as "a

D. L. Moody "could not conscientiously enlist" in the Union Army during the Civil War, later describing himself as "a

During a trip to the United Kingdom in the spring of 1872, Moody became well known as an evangelist. Literary works published by the

During a trip to the United Kingdom in the spring of 1872, Moody became well known as an evangelist. Literary works published by the  Moody visited Britain with

Moody visited Britain with

"Dwight Moody: evangelist with a common touch"

''Christianity Today'', August 8, 2008.

* Dorsett, L. W. ''A Passion for Souls: The Life of D. L. Moody.'' 1997 * Findlay, J. F. Jr. ''Dwight L. Moody: American Evangelist 1837–1899.'' 1969 * Gundry, S. N. ''Love them in: The Proclamation Theology of D. L. Moody.'' 1976 * Evensen, B. J. ''God's Man for Gilded Age: D. L. Moody and the Rise of Mass Evangelism.'' 2003 * Gloege, Timothy. ''Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism'' (2017) * Gustafson, David M. "D.L. Moody and the Swedish-American Evangelical Free." ''Swedish-American Historical Quarterly'' 55 (2004): 107–135

online

* Hamilton, Michael S. "The Interdenominational Evangelicalism of D.L. Moody and the Problem of Fundamentalism" in Darren Dochuk et al. eds. ''American Evangelicalism: George Marsden and the State of American Religious History'' (2014) ch 11. * Moody, Paul Dwight. ''The Shorter Life of D. L. Moody.'' 190

online

Recording of Moody reading the Beatitudes

* * * *

Glad Tidings, sermons by D. L. Moody

*

The Gospel Awakening, sermons by D. L. Moody

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moody, Dwight L. 1837 births 1899 deaths American Christian pacifists American evangelicals American evangelists American Christian hymnwriters American sermon writers Christian revivalists Founders of schools in the United States Moody Bible Institute people People from Northfield, Massachusetts YMCA leaders 19th-century American writers 19th-century American musicians Songwriters from Massachusetts Keswickianism 19th-century philanthropists

evangelist

Evangelist may refer to:

Religion

* Four Evangelists, the authors of the canonical Christian Gospels

* Evangelism, publicly preaching the Gospel with the intention of spreading the teachings of Jesus Christ

* Evangelist (Anglican Church), a co ...

and publisher connected with Keswickianism

The Higher Life movement, also known as the Keswick movement or Keswickianism, is a Protestant theological tradition within evangelical Christianity that espouses a distinct teaching on the doctrine of entire sanctification.

Its name comes fr ...

, who founded the Moody Church, Northfield School and Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts (now Northfield Mount Hermon School

Northfield Mount Hermon School, often called NMH, is a co-educational preparatory school in Gill, Massachusetts, in the United States. It is a member of the Eight Schools Association.

Present day

NMH offers nearly 200 courses, including AP a ...

), Moody Bible Institute

Moody Bible Institute (MBI) is a private evangelical Christian Bible college founded in the Near North Side of Chicago, Illinois, US by evangelist and businessman Dwight Lyman Moody in 1886. Historically, MBI has maintained positions that have ...

and Moody Publishers. One of his most famous quotes was "Faith makes all things possible... Love makes all things easy." Moody gave up his lucrative boot and shoe business to devote his life to revivalism, working first in the Civil War with Union troops through YMCA in the United States Christian Commission. In Chicago, he built one of the major evangelical centers in the nation, which is still active. Working with singer Ira Sankey

Ira David Sankey (August 28, 1840 – August 13, 1908) was an American gospel singer and composer, known for his long association with Dwight L. Moody in a series of religious revival campaigns in America and Britain during the closing decades o ...

, he toured the country and the British Isles, drawing large crowds with a dynamic speaking style.

Early life

Dwight Moody was born inNorthfield, Massachusetts

Northfield is a town in Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. Northfield was first settled in 1673. The population was 2,866 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The Connecticut R ...

, as the seventh child in a large family. His father, Edwin J. Moody (1800–1841), was a small farmer and stonemason. His mother was Betsey Moody (née Holton; 1805–1896). They had five sons and a daughter before Dwight's birth. His father died when Dwight was age four; fraternal twins, a boy, and a girl were born one month after the father's death. Their mother struggled to support the nine children but had to send some off to work for their room and board. Dwight too was sent off, where he received cornmeal, porridge, and milk three times a day. He complained to his mother, but when she learned that he was getting all he wanted to eat, she sent him back. During this time, she continued to send the children to church. Together with his eight siblings, Dwight was raised in the Unitarian church. His oldest brother ran away and was not heard from by the family until many years later.

When Moody turned 17, he moved to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

to work (after receiving many job rejections locally) in an uncle's shoe store. One of the uncle's requirements was that Moody attend the Congregational Church of Mount Vernon, where Dr. Edward Norris Kirk served as the pastor. In April 1855 Moody was converted to evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

Christianity when his Sunday school teacher, Edward Kimball, talked to him about how much God loved him. His conversion sparked the start of his career as an evangelist. Moody was not received by the church when he first applied in May 1855. He was not received as a church member until May 4, 1856.

According to Moody's memoir, his teacher, Edward Kimball, said:

Civil War

D. L. Moody "could not conscientiously enlist" in the Union Army during the Civil War, later describing himself as "a

D. L. Moody "could not conscientiously enlist" in the Union Army during the Civil War, later describing himself as "a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

" in this respect. After the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

started, he became involved with the United States Christian Commission The United States Christian Commission (USCC) was an organization that furnished supplies, medical services, and religious literature to Union troops during the American Civil War. It combined religious support with social services and recreationa ...

of YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

. He paid nine visits to the battlefront, being present among the Union soldiers after the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

(a.k.a. Pittsburg Landing) and the Battle of Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, also known as the Second Battle of Murfreesboro, was a battle fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, in Middle Tennessee, as the culmination of the Stones River Campaign in the Western Theater of the Am ...

; he also entered Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, with the troops of General Grant.

On August 28, 1862, Moody married Emma C. Revell, with whom he had a daughter, Emma Reynolds Moody, and two sons, William Revell Moody and Paul Dwight Moody

Paul Dwight Moody (April 11, 1879 – August 18, 1947), son of famed evangelical minister Dwight L. Moody, served as pastor at South Congregational Church in St. Johnsbury, Vermont from 1912 to 1917 and as the 10th president of Middlebury Co ...

.

Chicago and the postwar years

In 1858, he started a Sunday school. The growing Sunday School congregation needed a permanent home, so Moody started a church in Chicago, the Illinois Street Church in 1864. In June 1871 at an International Sunday School Convention inIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Indiana, Dwight Moody met Ira D. Sankey

Ira David Sankey (August 28, 1840 – August 13, 1908) was an American gospel singer and composer, known for his long association with Dwight L. Moody in a series of religious revival campaigns in America and Britain during the closing decades o ...

. He was a gospel singer, with whom Moody soon began to cooperate and collaborate.

Four months later, in October 1871, the Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 1 ...

destroyed Moody's church building, as well as his house and those of most of his congregation. Many had to flee the flames, saving only their lives, and ending up completely destitute. Moody, reporting on the disaster, said about his own situation that: "...he saved nothing but his reputation and his Bible."

In the years after the fire, Moody's wealthy Chicago patron John V. Farwell

John Villiers Farwell Sr. (July 29, 1825 – August 20, 1908) was an American merchant and philanthropist from New York City. Moving to Chicago, Illinois at a young age, he joined Wadsworth & Phelps, eventually rising to be senior partner at Joh ...

tried to persuade him to make his permanent home in the city, offering to build a new house for Moody and his family. But the newly famous Moody, also sought by supporters in New York, Philadelphia, and elsewhere, chose a tranquil farm he had purchased near his birthplace in Northfield, Massachusetts

Northfield is a town in Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. Northfield was first settled in 1673. The population was 2,866 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The Connecticut R ...

. He felt he could better recover in a rural setting from his lengthy preaching trips.

Northfield became an important location in evangelical Christian history in the late 19th century as Moody organized summer conferences. These were led and attended by prominent Christian preachers and evangelists from around the world. Western Massachusetts has had a rich evangelical tradition including Jonathan Edwards preaching in colonial Northampton and C.I. Scofield preaching in Northfield. A protégé of Moody founded Moores Corner Church, in Leverett, Massachusetts

Leverett is a town in Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,865 as of the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The Town of Leverett is located on the t ...

.

Moody founded two schools here: Northfield School for Girls, founded in 1879, and the Mount Hermon School for Boys, founded in 1881. In the late 20th century, these merged, forming today's co-educational, nondenominational Northfield Mount Hermon

Northfield Mount Hermon School, often called NMH, is a co-educational preparatory school in Gill, Massachusetts, in the United States. It is a member of the Eight Schools Association.

Present day

NMH offers nearly 200 courses, including AP and ...

School.

Evangelistic travels

During a trip to the United Kingdom in the spring of 1872, Moody became well known as an evangelist. Literary works published by the

During a trip to the United Kingdom in the spring of 1872, Moody became well known as an evangelist. Literary works published by the Moody Bible Institute

Moody Bible Institute (MBI) is a private evangelical Christian Bible college founded in the Near North Side of Chicago, Illinois, US by evangelist and businessman Dwight Lyman Moody in 1886. Historically, MBI has maintained positions that have ...

claim that he was the greatest evangelist of the 19th century. He preached almost a hundred times and came into communion with the Plymouth Brethren

The Plymouth Brethren or Assemblies of Brethren are a low church and non-conformist Christian movement whose history can be traced back to Dublin, Ireland, in the mid to late 1820s, where they originated from Anglicanism. The group emphasizes ...

. On several occasions, he filled stadia of a capacity of 2,000 to 4,000. According to his memoir, in the Botanic Gardens Palace, he attracted an audience estimated at between 15,000 and 30,000.

That turnout continued throughout 1874 and 1875, with crowds of thousands at all of his meetings. During his visit to Scotland, Moody was helped and encouraged by Andrew A. Bonar. The famous London Baptist preacher, Charles Spurgeon, invited him to speak, and he promoted the American as well. When Moody returned to the US, he was said to frequently attract crowds of 12,000 to 20,000 were as common as they had been in England. President Grant and some of his cabinet officials attended a Moody meeting on January 19, 1876. He held evangelistic meetings from Boston to New York, throughout New England, and as far west as San Francisco, also visiting other West Coast towns from Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. The ...

, Canada to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

.

Moody aided the work of cross-cultural evangelism by promoting "The Wordless Book

The ''Wordless Book'' is a Christian evangelistic book. Evidence points to it being invented by the famous London Baptist preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon, in a message given on January 11, 1866. to several hundred orphans regarding Psalm 51: ...

," a teaching tool developed in 1866 by Charles Spurgeon. In 1875, Moody added a fourth color to the design of the three-color evangelistic device: gold — to "represent heaven." This "book" has been and is still used to teach uncounted thousands of illiterate people, young and old, around the globe about the gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

message.

Moody visited Britain with

Moody visited Britain with Ira D. Sankey

Ira David Sankey (August 28, 1840 – August 13, 1908) was an American gospel singer and composer, known for his long association with Dwight L. Moody in a series of religious revival campaigns in America and Britain during the closing decades o ...

, with Moody preaching and Sankey singing at meetings. Together they published books of Christian hymns

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

. In 1883 they visited Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and raised £10,000 for the building of a new home for the Carrubbers Close Mission. Moody later preached at the laying of the foundation stone for what is now called the Carrubbers Christian Centre

Carrubbers Christian Centre is a church on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, Scotland.

History

Carrubbers Close Mission was founded in 1858 and its 'workers' originally met in a former Atheist Meeting House in Carrubbers Close. The Rev. James Gal ...

, one of the few buildings on the Royal Mile

The Royal Mile () is a succession of streets forming the main thoroughfare of the Old Town of the city of Edinburgh in Scotland. The term was first used descriptively in W. M. Gilbert's ''Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century'' (1901), de ...

which continues to be used for its original purpose.

Moody greatly influenced the cause of cross-cultural Christian missions

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such ...

after he met Hudson Taylor

James Hudson Taylor (; 21 May 1832 – 3 June 1905) was a British Baptist Christian missionary to China and founder of the China Inland Mission (CIM, now OMF International). Taylor spent 51 years in China. The society that he began was respons ...

, a pioneer missionary to China. He actively supported the China Inland Mission

OMF International (formerly Overseas Missionary Fellowship and before 1964 the China Inland Mission) is an international and interdenominational Evangelical Christian missionary society with an international centre in Singapore. It was founded in ...

and encouraged many of his congregation to volunteer for service overseas.

International acclaim

His influence was felt among Swedes. Being of English heritage, never visiting Sweden or any other Scandinavian country, and never speaking a word of Swedish, nonetheless, he became a hero revivalist among Swedish Mission Friends () in Sweden and America. News of Moody's large revival campaigns in Great Britain from 1873 through 1875 traveled quickly to Sweden, making "Mr. Moody" a household name in homes of many Mission Friends. Moody's sermons published in Sweden were distributed in books, newspapers, andcolporteur

Colportage is the distribution of publications, books, and religious tracts by carriers called "colporteurs" or "colporters". The term does not necessarily refer to religious book peddling.

Etymology

From French , where the term is an altera ...

tracts, and they led to the spread of Sweden's "Moody fever" from 1875 through 1880.

He preached his last sermon on November 16, 1899, in Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020, making it the List of United States cities by populat ...

. Becoming ill, he returned home by train to Northfield. During the preceding several months, friends had observed he had added some to his already ample frame. Although his illness was never diagnosed, it has been speculated that he suffered from congestive heart failure. He died on December 26, 1899, surrounded by his family. Already installed as the leader of his Chicago Bible Institute, R. A. Torrey

Reuben Archer Torrey (28 January 1856 – 26 October 1928) was an American evangelist, pastor, educator, and writer. He aligned with Keswick theology.

Biography

Torrey was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, the son of a banker. He graduated from ...

succeeded Moody as its pastor.

Works

*''Heaven'' Diggory Press *'' Prevailing Prayer—What Hinders it?'' Diggory Press *''Secret Power'' Diggory Press *''The Ten Commandments'' *Also, A Life for Christ—What a Normal Christian Life Looks Like. * ''The Way to God and How to Find it''Legacy

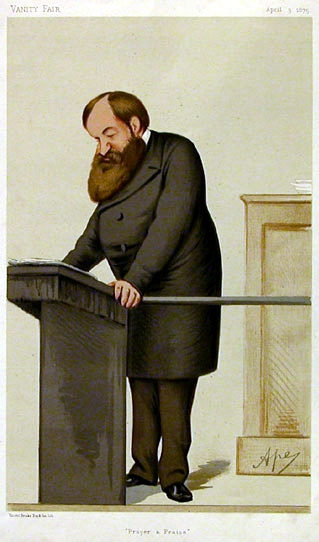

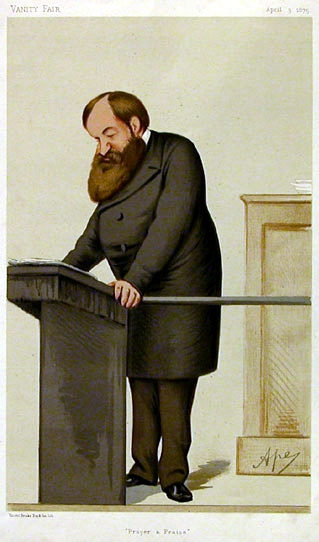

Religious historian James Findlay says that: : Speaking before thousands in the dark business suit, bearded, rotund Dwight L. Moody seemed the epitome of the "businessman in clerical garb" who typified popular religion in late 19th-century America... Earthy, unlettered, a dynamo of energy, the revivalist was very much a man of his times... Moody adapted revivalism, one of the major institutions of evangelical Protestantism, to the urban context. ... His organizational ability, demonstrated in the great revivals he conducted in England, combined to fashion his spectacular career as the creator of modern mass revivalism. Ten years after Moody's death the Chicago Avenue Church was renamed the Moody Church in his honor, and the Chicago Bible Institute has likewise renamed theMoody Bible Institute

Moody Bible Institute (MBI) is a private evangelical Christian Bible college founded in the Near North Side of Chicago, Illinois, US by evangelist and businessman Dwight Lyman Moody in 1886. Historically, MBI has maintained positions that have ...

.

During World War II the Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Ma ...

was built in Panama City, Florida

Panama City is a city in and the county seat of Bay County, Florida, United States. Located along U.S. Highway 98 (US 98), it is the largest city between Tallahassee and Pensacola. It is the more populated city of the Panama City–Lynn ...

, and named in his honor.

See also

* William Phillips Hall, a close friend that was influenced to become an evangelist and lay preacher. *Horatio Spafford

Horatio Gates Spafford (October 20, 1828, Troy, New York – September 25, 1888, Jerusalem) was a prominent American lawyer and Presbyterian church elder. He is best known for penning the Christian hymn '' It Is Well With My Soul'' following a f ...

, a friend of Moody who wrote the words to the hymn ''It Is Well With My Soul''

*Northfield Mount Hermon School

Northfield Mount Hermon School, often called NMH, is a co-educational preparatory school in Gill, Massachusetts, in the United States. It is a member of the Eight Schools Association.

Present day

NMH offers nearly 200 courses, including AP a ...

References

Sources

"Dwight Moody: evangelist with a common touch"

''Christianity Today'', August 8, 2008.

* Dorsett, L. W. ''A Passion for Souls: The Life of D. L. Moody.'' 1997 * Findlay, J. F. Jr. ''Dwight L. Moody: American Evangelist 1837–1899.'' 1969 * Gundry, S. N. ''Love them in: The Proclamation Theology of D. L. Moody.'' 1976 * Evensen, B. J. ''God's Man for Gilded Age: D. L. Moody and the Rise of Mass Evangelism.'' 2003 * Gloege, Timothy. ''Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism'' (2017) * Gustafson, David M. "D.L. Moody and the Swedish-American Evangelical Free." ''Swedish-American Historical Quarterly'' 55 (2004): 107–135

online

* Hamilton, Michael S. "The Interdenominational Evangelicalism of D.L. Moody and the Problem of Fundamentalism" in Darren Dochuk et al. eds. ''American Evangelicalism: George Marsden and the State of American Religious History'' (2014) ch 11. * Moody, Paul Dwight. ''The Shorter Life of D. L. Moody.'' 190

online

External links

Recording of Moody reading the Beatitudes

* * * *

Glad Tidings, sermons by D. L. Moody

*

The Gospel Awakening, sermons by D. L. Moody

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moody, Dwight L. 1837 births 1899 deaths American Christian pacifists American evangelicals American evangelists American Christian hymnwriters American sermon writers Christian revivalists Founders of schools in the United States Moody Bible Institute people People from Northfield, Massachusetts YMCA leaders 19th-century American writers 19th-century American musicians Songwriters from Massachusetts Keswickianism 19th-century philanthropists