Dunsterforce on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dunsterforce was an Allied military force, established in December 1917 and named after its commander, Major-General

Russian policy towards Iran in 1914 was based on assurances that Iranian territorial integrity would be respected. Tsarist expansion in northern Iran and opposition to the emergence of a stable modern state, led to suspicion that its policy was really to keep Iran as a dependency or to absorb more of its northern provinces. Britain traditionally sought to maintain commercial interests in the country and the use of naval power to protect India. The geographical position of Iran, between Europe and India and the ancient west–east trade routes through Iranian provinces, had led the British in the nineteenth century to follow a policy of using Iran as a buffer state.

The British in practice preferred inaction, although it enabled Russian expansionism until the Anglo-Russian Convention (Anglo-Russian Entente) of 1907. The Russian sphere ran from Meshed in the east to Tabriz in the west and as far south as

Russian policy towards Iran in 1914 was based on assurances that Iranian territorial integrity would be respected. Tsarist expansion in northern Iran and opposition to the emergence of a stable modern state, led to suspicion that its policy was really to keep Iran as a dependency or to absorb more of its northern provinces. Britain traditionally sought to maintain commercial interests in the country and the use of naval power to protect India. The geographical position of Iran, between Europe and India and the ancient west–east trade routes through Iranian provinces, had led the British in the nineteenth century to follow a policy of using Iran as a buffer state.

The British in practice preferred inaction, although it enabled Russian expansionism until the Anglo-Russian Convention (Anglo-Russian Entente) of 1907. The Russian sphere ran from Meshed in the east to Tabriz in the west and as far south as

The commander of Dunsterforce, Major-General

The commander of Dunsterforce, Major-General  After contemplating the hijack of a ship to run the gauntlet of Bolshevik-operated coastal craft, Dunsterville decided not to risk alienating local opinion and turned back, intending to meet the party en route from Europe and make arrangements in Iran, while waiting for another chance to reach Tiflis. On 20 February, the party dodged the local authorities and returned to Hamadan, where it could use MEF and Russian army wireless stations, to keep in touch with Baghdad. It had become clear that there was little chance that the Russians formerly under Baratov could be induced to remain on service and that only Colonel Lazar Bicherakov and some of his Cossacks were willing to continue. On 11 February, Bicherakov flew to Baghdad and told Marshall that the Cossacks were willing to act as rearguard for the Russians before leaving and that the Tiflis initiative was doomed to failure. Marshall wanted an advance on Mosul to protect the Persian road but was over-ruled, in preference for operations in Palestine and at Hamadan, Dunsterville claimed that the Iranian public welcomed British protection and requested that he might wait at Hamadan to try again.

To gain the support of the Iranian public, Dunsterville made an effort to relieve the famine, caused partly by a drought and partly by Russian and Ottoman military operations in north-west Iran. The Dunsterville Mission had plenty of money and recruited local labour to repair roads. By a ruse, Dunsterville got the local grain merchants, mostly supporters of the Democratic Party and in the pay of the Germans, to stop hoarding, which proved very popular. The Democrats retaliated by claiming that the British had poisoned the wheat and sniped at the British in Hamadan but public support for the British increased as the famine relief measures took effect. The Dunsterville Mission was also able to establish an intelligence organisation that saw all telegrams and letters concerning the mission. After the Bicherakov Cossack detachment moved from Kermanshah to Kazvin and blocked the Jangalis from using the Teheran road, the mission was able to arrest the passage of German and Ottoman agents with local levies of Christian Assyrians for local order and security duties. The prisoners were guarded a party of the 1/4th Hampshire and the "Irregulars", a military force was raised from the hill peoples of the north-west closer to the Ottoman border, to oppose an Ottoman move against the Persian road from Armenia.

Baratov sold Dunsterville most of the weapons and supplies of the Russian Army but some were also traded by Russian soldiers to the Persian locals and the Kurdish hill peoples, leaving them exceptionally well armed. By the end of March, all but the Bicherakov Cossack detachment at Kazvin had withdrawn and the MEF extended its hold on the road to Kermanshah, with the 36th Brigade. Dunsterville borrowed some infantry and cavalry and Bicherakov agreed to remain at Kazvin, until British troops could take over. Twenty officers and twenty NCOs of Dunsterforce arrived by Ford car on 3 April, the rest of the force making their way on foot with a mule train, all arriving by 25 May. By the time that the rest of Dunsterforce had arrived, the local and international situation had changed; the success of the German spring offensive in France leading the Georgians to bid for German support; in May the Germans took over part of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. The Ottomans repudiated the treaty of Brest Litovsk and began to organise Tartars into the

After contemplating the hijack of a ship to run the gauntlet of Bolshevik-operated coastal craft, Dunsterville decided not to risk alienating local opinion and turned back, intending to meet the party en route from Europe and make arrangements in Iran, while waiting for another chance to reach Tiflis. On 20 February, the party dodged the local authorities and returned to Hamadan, where it could use MEF and Russian army wireless stations, to keep in touch with Baghdad. It had become clear that there was little chance that the Russians formerly under Baratov could be induced to remain on service and that only Colonel Lazar Bicherakov and some of his Cossacks were willing to continue. On 11 February, Bicherakov flew to Baghdad and told Marshall that the Cossacks were willing to act as rearguard for the Russians before leaving and that the Tiflis initiative was doomed to failure. Marshall wanted an advance on Mosul to protect the Persian road but was over-ruled, in preference for operations in Palestine and at Hamadan, Dunsterville claimed that the Iranian public welcomed British protection and requested that he might wait at Hamadan to try again.

To gain the support of the Iranian public, Dunsterville made an effort to relieve the famine, caused partly by a drought and partly by Russian and Ottoman military operations in north-west Iran. The Dunsterville Mission had plenty of money and recruited local labour to repair roads. By a ruse, Dunsterville got the local grain merchants, mostly supporters of the Democratic Party and in the pay of the Germans, to stop hoarding, which proved very popular. The Democrats retaliated by claiming that the British had poisoned the wheat and sniped at the British in Hamadan but public support for the British increased as the famine relief measures took effect. The Dunsterville Mission was also able to establish an intelligence organisation that saw all telegrams and letters concerning the mission. After the Bicherakov Cossack detachment moved from Kermanshah to Kazvin and blocked the Jangalis from using the Teheran road, the mission was able to arrest the passage of German and Ottoman agents with local levies of Christian Assyrians for local order and security duties. The prisoners were guarded a party of the 1/4th Hampshire and the "Irregulars", a military force was raised from the hill peoples of the north-west closer to the Ottoman border, to oppose an Ottoman move against the Persian road from Armenia.

Baratov sold Dunsterville most of the weapons and supplies of the Russian Army but some were also traded by Russian soldiers to the Persian locals and the Kurdish hill peoples, leaving them exceptionally well armed. By the end of March, all but the Bicherakov Cossack detachment at Kazvin had withdrawn and the MEF extended its hold on the road to Kermanshah, with the 36th Brigade. Dunsterville borrowed some infantry and cavalry and Bicherakov agreed to remain at Kazvin, until British troops could take over. Twenty officers and twenty NCOs of Dunsterforce arrived by Ford car on 3 April, the rest of the force making their way on foot with a mule train, all arriving by 25 May. By the time that the rest of Dunsterforce had arrived, the local and international situation had changed; the success of the German spring offensive in France leading the Georgians to bid for German support; in May the Germans took over part of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. The Ottomans repudiated the treaty of Brest Litovsk and began to organise Tartars into the  The Bolsheviks asked for British assistance to reorganise the Black Sea Fleet and it appeared possible that a rapprochement with the Bolsheviks and the Armenians could be arranged, in return for British protection of Baku. Control of the port and shipping on the Caspian Sea might still achieve British and Allied objectives, despite the Ottoman push eastwards into the vacuum left by the decline of the Tsarist army. The War Office and the British command in India considered that the good campaigning weather of a Caucasian summer should be exploited by augmenting Dunsterforce as much as possible. Operations on the Euphrates by the

The Bolsheviks asked for British assistance to reorganise the Black Sea Fleet and it appeared possible that a rapprochement with the Bolsheviks and the Armenians could be arranged, in return for British protection of Baku. Control of the port and shipping on the Caspian Sea might still achieve British and Allied objectives, despite the Ottoman push eastwards into the vacuum left by the decline of the Tsarist army. The War Office and the British command in India considered that the good campaigning weather of a Caucasian summer should be exploited by augmenting Dunsterforce as much as possible. Operations on the Euphrates by the

The Dunsterforce parties moved off via Zenjan, with their destinations secret until they were on their way, just after the fourth group of Dunsterforce arrived. Soon after the party for Zenjan arrived it was sent on another to Mianeh about from Tabriz and the Bijar party pressed on, using a track last reported on by British intelligence in 1842, arriving on 18 June. The Ottoman advance further north on Baku, was opposed by about and Bolshevik troops with about and pieces. Dunsterville proposed to reconnoitre, regardless of the reluctance of the Russian Bolshevik government to allow British interference. On 12 June, the Bicherakov Cossacks advanced from Kazvin and defeated the Jangai at Manjil bridge, reaching Bandar-e Anzali a few days later. Bicherakov took ship for Baku, styled himself a Bolshevik, was appointed commander of the Red Army in Caucasus, then returned to Bandar-e Anzali. In June, the

The Dunsterforce parties moved off via Zenjan, with their destinations secret until they were on their way, just after the fourth group of Dunsterforce arrived. Soon after the party for Zenjan arrived it was sent on another to Mianeh about from Tabriz and the Bijar party pressed on, using a track last reported on by British intelligence in 1842, arriving on 18 June. The Ottoman advance further north on Baku, was opposed by about and Bolshevik troops with about and pieces. Dunsterville proposed to reconnoitre, regardless of the reluctance of the Russian Bolshevik government to allow British interference. On 12 June, the Bicherakov Cossacks advanced from Kazvin and defeated the Jangai at Manjil bridge, reaching Bandar-e Anzali a few days later. Bicherakov took ship for Baku, styled himself a Bolshevik, was appointed commander of the Red Army in Caucasus, then returned to Bandar-e Anzali. In June, the

In 1918, Urmia was defended by Christian (

In 1918, Urmia was defended by Christian (

Baku was attacked on 29 July and again the local troops ran away, leaving the Bicherakov Cossacks in the lurch. On 31 July, the Ottomans attacked Hill 905 north-west of Baku at and continued until 2 August. The 10th Caucasian Infantry Division, the 51st Infantry Division, several batteries of artillery and a cavalry regiment arrived but another attack on 5 August failed, with casualties. The 10th Caucasian Infantry Division was withdrawn to rest and the 15th Infantry Division took over. When the Ottomans were about from the docks, Bicherakov decided to retreat to

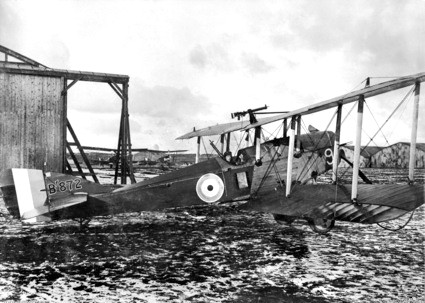

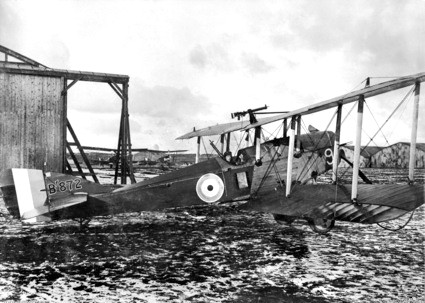

Baku was attacked on 29 July and again the local troops ran away, leaving the Bicherakov Cossacks in the lurch. On 31 July, the Ottomans attacked Hill 905 north-west of Baku at and continued until 2 August. The 10th Caucasian Infantry Division, the 51st Infantry Division, several batteries of artillery and a cavalry regiment arrived but another attack on 5 August failed, with casualties. The 10th Caucasian Infantry Division was withdrawn to rest and the 15th Infantry Division took over. When the Ottomans were about from the docks, Bicherakov decided to retreat to  Without the support of local troops, Dunsterforce could not defend Baku and so the locals were reorganised into brigades of three Baku battalions, each with Dunsterforce advisers and one British battalion. Dunsterville had ordered two Martinsyde Elephants of 72 Squadron RAF to Baku, to encourage the population and on 18 August, the aeroplanes flew from Kazvin to Bandar-e Anzali. The aircraft flew on to Baku and by 20 August, the Martinsydes were ready for operations.

The Armenians attempted bravado but during Ottoman attacks, tended to hang back or melt away; a Bolshevik crew of a ship reported to Dunsterville that,

On 26 August, the Ottomans captured Mud Volcano and inflicted many casualties on the British battalion. The British repulsed the Ottomans four times but the local troops melted away; a Canadian captain commanding an Armenian battalion suddenly found himself alone and the fifth attack succeeded.

In another attack on 31 August, a Russian battalion joined in and assisted the British during a retirement but Dunsterville threatened the Baku authorities, that he would order more withdrawals of British troops, rather than leave them to be killed. Next day he told the Dictators that he would evacuate Baku that night, at which the Dictators replied that the British could only go after women and children had left and at the same time as the local troops; Russian gunboats were ordered to fire on the British if their ships tried to leave. Dunsterville took no notice but had second thoughts and the situation improved, when Bicherakov sent reinforcements, with a promise of in two weeks. Another Russian controlled settlement was at

Without the support of local troops, Dunsterforce could not defend Baku and so the locals were reorganised into brigades of three Baku battalions, each with Dunsterforce advisers and one British battalion. Dunsterville had ordered two Martinsyde Elephants of 72 Squadron RAF to Baku, to encourage the population and on 18 August, the aeroplanes flew from Kazvin to Bandar-e Anzali. The aircraft flew on to Baku and by 20 August, the Martinsydes were ready for operations.

The Armenians attempted bravado but during Ottoman attacks, tended to hang back or melt away; a Bolshevik crew of a ship reported to Dunsterville that,

On 26 August, the Ottomans captured Mud Volcano and inflicted many casualties on the British battalion. The British repulsed the Ottomans four times but the local troops melted away; a Canadian captain commanding an Armenian battalion suddenly found himself alone and the fifth attack succeeded.

In another attack on 31 August, a Russian battalion joined in and assisted the British during a retirement but Dunsterville threatened the Baku authorities, that he would order more withdrawals of British troops, rather than leave them to be killed. Next day he told the Dictators that he would evacuate Baku that night, at which the Dictators replied that the British could only go after women and children had left and at the same time as the local troops; Russian gunboats were ordered to fire on the British if their ships tried to leave. Dunsterville took no notice but had second thoughts and the situation improved, when Bicherakov sent reinforcements, with a promise of in two weeks. Another Russian controlled settlement was at  In early September, an evacuation was considered and the War Office agreed with Marshall, that British troops should be withdrawn. The Ottoman success had been costly and it was only after the arrival of reinforcements that the attack could be resumed on 14 September, a plan disclosed to the defenders by a deserter on 12 September. The Ottoman plan for the final assault on Baku, was for the 15th Infantry Division to attack from the north and the 5th Caucasian Infantry Division to attack from the west, with the main attack on the north-west corner of the Baku defence line. The attack began at along a road through Wolf's Gap in the ridge. In clouds and mist, the two British pilots

In early September, an evacuation was considered and the War Office agreed with Marshall, that British troops should be withdrawn. The Ottoman success had been costly and it was only after the arrival of reinforcements that the attack could be resumed on 14 September, a plan disclosed to the defenders by a deserter on 12 September. The Ottoman plan for the final assault on Baku, was for the 15th Infantry Division to attack from the north and the 5th Caucasian Infantry Division to attack from the west, with the main attack on the north-west corner of the Baku defence line. The attack began at along a road through Wolf's Gap in the ridge. In clouds and mist, the two British pilots

Persia becomes Iran

Medman, L. Dunsterforce's top ranking Canadian officer, Lieutenant-Colonel John Weightman Warden

Newsreel of Dunsterforce, Australian War Memorial

Imperial War Museums. Video footage: Baku - The Occupation by 'Dunsterforce' 17th August to 14th September 1918

{{Use dmy dates, date=June 2017 History of the British Isles Ad hoc units and formations of the British Army Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War 20th century in Armenia Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations 20th-century military history of the United Kingdom Military history of Azerbaijan Military units and formations established in 1917 1910s in Iran Military history of Qajar Iran

Lionel Dunsterville

Major General Lionel Charles Dunsterville, (9 November 1865 – 18 March 1946) was a British Army officer, who led Dunsterforce across present-day Iraq and Iran towards the Caucasus and Baku during the First World War.

Early life

Lionel Ch ...

. The force comprised fewer than 350 Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal A ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, British and Canadian officers and NCOs, who were drawn from the Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

fronts. The force was intended to organise local units in northern Iran (Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

) and South Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

, to replace the Tsarist army that had fought the Ottoman armies in Armenia. The Russians had also occupied northern Iran in co-operation with the British occupation of southern Iran, to create a cordon to prevent German and Ottoman agents from reaching Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

.

In July 1918, Captain Stanley Savige

Lieutenant General Sir Stanley George Savige, (26 June 1890 – 15 May 1954) was an Australian Army soldier and officer who served in the First World War and Second World War.

In March 1915, after the outbreak of the First World War, Savi ...

, five officers and fifteen NCOs of Dunsterforce, set out towards Urmia

Urmia or Orumiyeh ( fa, ارومیه, Variously transliterated as ''Oroumieh'', ''Oroumiyeh'', ''Orūmīyeh'' and ''Urūmiyeh''.) is the largest city in West Azerbaijan Province of Iran and the capital of Urmia County. It is situated at an al ...

and were caught up in an exodus of Assyrians, after the town had been captured by the Ottoman army. About fled and the Dunsterforce party helped hold off the Ottoman pursuit and attempts by local Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian peoples, Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Ir ...

to get revenge on the Assyrians for their earlier plundering. By the time the rearguard reached Bijar Bijar may refer to:

* Bijar (city), a city in Kordestan Province, Iran

** Bijar County

Bijar County ( fa, شهرستان بیجار; ku, شارستانی بیجاڕ) is in Kurdistan province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic R ...

on 17 August, the Dunsterforce party was so worn out that only four men recovered before the war ended. A combined infantry and cavalry brigade was raised from the Assyrian survivors to re-capture Urmia and the rest of the civilians were sent to refugee camps at Baqubah

Baqubah ( ar, بَعْقُوبَة; BGN: Ba‘qūbah; also spelled Baquba and Baqouba) is the capital of Iraq's Diyala Governorate. The city is located some to the northeast of Baghdad, on the Diyala River. In 2003 it had an estimated populat ...

near Baghdad.

Dunsterville and the rest of the force, with reinforcements from the 39th Infantry Brigade, drove in and armoured cars about from Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') (Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ham ...

across Qajar Iran

Qajar Iran (), also referred to as Qajar Persia, the Qajar Empire, '. Sublime State of Persia, officially the Sublime State of Iran ( fa, دولت علیّه ایران ') and also known then as the Guarded Domains of Iran ( fa, ممالک م ...

to Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world an ...

. Dunsterforce fought in the Battle of Baku

The Battle of Baku ( az, Bakı döyüşü, tr, Bakü Muharebesi, russian: Битва за Баку) was a battle in World War I that took place between August–September 1918 between the Ottoman–Azerbaijani coalition forces led by Nuri Pas ...

from 26 August to 14 September 1918 and retreated from the city on the night of to be disbanded two days later. North Persia Force

North Persia Force (Norper force) was a British military force that operated in Northern Persia from 1918–1919.

Composition

The force was a large brigade which consisted of:

* 1st Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers

* 1st Battalion, 42nd Deoli Regi ...

(Norper Force, Major-General William Thomson) took over command of the troops in northern Iran. Troops diverted from Dunsterforce in Sweet's Column opposed an Ottoman diversion from Tabriz, on the Persian road, during September; the situation was transformed by news of the great British victory in the Battle of Megiddo in Palestine The army in Caucasus was the only source of Ottoman reinforcements and had to give up divisions, ending offensive operations in the theatre.

Background

North-West Frontier

Britain and Russia had playedThe Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

for influence in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

from the early nineteenth century but in the 1880s, Russian absorption of the local Khanate

A khaganate or khanate was a polity ruled by a khan, khagan, khatun, or khanum. That political territory was typically found on the Eurasian Steppe and could be equivalent in status to tribal chiefdom, principality, kingdom or empire.

Mo ...

s and Emirate

An emirate is a territory ruled by an emir, a title used by monarchs or high officeholders in the Muslim world. From a historical point of view, an emirate is a political-religious unit smaller than a caliphate. It can be considered equivalen ...

s restricted British influence. The Anglo-Russian Convention

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 (russian: Англо-Русская Конвенция 1907 г., translit=Anglo-Russkaya Konventsiya 1907 g.), or Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet (; ...

of 1907 ended the rivalry by defining spheres of influence in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

. Early in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, British and Indian forces set up the East Persia Cordon with Seistan Force

The Seistan Force, originally called East Persia Cordon, was a force of British Indian Army troops set up to prevent infiltration by German and Ottoman agents from Persia (Iran) into Afghanistan during World War I. The force was established to pro ...

assembled from the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the Land warfare, land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Arm ...

. The force was created to counter German, Austrian and Ottoman subversion in Afghanistan and the North West Frontier of British India. Two squadrons of the 28th Cavalry Regiment

The 28th Cavalry Regiment (Horse) (Colored) was a short-lived African-American unit of the United States Army. The 28th Cavalry was the last horse-mounted cavalry regiment formed by the U.S. Army. The regiment was formed as part of the 2nd Ca ...

and the locally raised South Persia Rifles

The South Persia Rifles (Persian: تپانچهداران جنوب پارس), also known as SPR, was a Persian military force recruited by the British in 1916 and under British command.Fromkin, p. 209 They participated in the Persian Campaign ...

patrolled the border of Baluchistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western Asia, Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian S ...

and the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest emp ...

. The Russian Revolution of 1917 led to the collapse of the convention; the dissolution of the Tsarist armies from March 1917 left open the Caspian Sea and the route from Baku to Krasnovodsk and Central Asia to the Central Powers. In the spring of 1918, German and Ottoman forces advanced into Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

and Central Asia.

Iran

Russian policy towards Iran in 1914 was based on assurances that Iranian territorial integrity would be respected. Tsarist expansion in northern Iran and opposition to the emergence of a stable modern state, led to suspicion that its policy was really to keep Iran as a dependency or to absorb more of its northern provinces. Britain traditionally sought to maintain commercial interests in the country and the use of naval power to protect India. The geographical position of Iran, between Europe and India and the ancient west–east trade routes through Iranian provinces, had led the British in the nineteenth century to follow a policy of using Iran as a buffer state.

The British in practice preferred inaction, although it enabled Russian expansionism until the Anglo-Russian Convention (Anglo-Russian Entente) of 1907. The Russian sphere ran from Meshed in the east to Tabriz in the west and as far south as

Russian policy towards Iran in 1914 was based on assurances that Iranian territorial integrity would be respected. Tsarist expansion in northern Iran and opposition to the emergence of a stable modern state, led to suspicion that its policy was really to keep Iran as a dependency or to absorb more of its northern provinces. Britain traditionally sought to maintain commercial interests in the country and the use of naval power to protect India. The geographical position of Iran, between Europe and India and the ancient west–east trade routes through Iranian provinces, had led the British in the nineteenth century to follow a policy of using Iran as a buffer state.

The British in practice preferred inaction, although it enabled Russian expansionism until the Anglo-Russian Convention (Anglo-Russian Entente) of 1907. The Russian sphere ran from Meshed in the east to Tabriz in the west and as far south as Teheran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

and the British sphere ran west of the North-West Frontier of India and the Afghan border, west to the vicinity of Bandar Abbas

Bandar Abbas or Bandar-e ‘Abbās ( fa, , , ), is a port city and capital of Hormozgān Province on the southern coast of Iran, on the Persian Gulf. The city occupies a strategic position on the narrow Strait of Hormuz (just across from Musand ...

on the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

. Only the Ottoman Empire remained as a possible field for German diplomatic and economic influence. Traditional Ottoman hostility to Iran on religious grounds meant that the Pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism ( ar, الوحدة الإسلامية) is a political movement advocating the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Pan-Islamism wa ...

of Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

of the Ottoman Empire failed to gain much of a following in Iran, until the Young Persians took it up as a political tool. The Young Turks in the Ottoman Empire evolved into Pan-Turanists, seeking to renew the Ottoman Empire by expanding into Trans-Caucasia, Turkestan

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan ( fa, ترکستان, Torkestân, lit=Land of the Turks), is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and Xinjiang.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turk ...

and at least the north-west of Iran. By 1914 little attention had been paid to the Pan-Turanists, mainly due to the power of the Russian Empire; Ottoman encroachments on Iran were seen as defensive moves against Russia.

In 1914, British forces from India occupied Iranian territory east of the Shatt al-Arab

The Shatt al-Arab ( ar, شط العرب, lit=River of the Arabs; fa, اروندرود, Arvand Rud, lit=Swift River) is a river of some in length that is formed at the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the town of al-Qurnah in ...

waterway, to guard oil concessions in Iran and in 1915 advanced up the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

river to Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon ( ; Middle Persian: 𐭲𐭩𐭮𐭯𐭥𐭭 ''tyspwn'' or ''tysfwn''; fa, تیسفون; grc-gre, Κτησιφῶν, ; syr, ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢThomas A. Carlson et al., “Ctesiphon — ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modi ...

near Baghdad, before being defeated by the Ottoman army and forced to retreat to Kut. During the Siege of Kut

The siege of Kut Al Amara (7 December 1915 – 29 April 1916), also known as the first battle of Kut, was the besieging of an 8,000 strong British Army garrison in the town of Kut, south of Baghdad, by the Ottoman Army. In 1915, its population ...

the Ottomans defeated three relief attempts and refused an offer of £2,000,000 to ransom the garrison, which surrendered at the end of April. Hopes of a Russian relief force from the Caspian Sea through Kermanshah

Kermanshah ( fa, کرمانشاه, Kermânšâh ), also known as Kermashan (; romanized: Kirmaşan), is the capital of Kermanshah Province, located from Tehran in the western part of Iran. According to the 2016 census, its population is 946,68 ...

and Khanaqin

Khanaqin ( ar, خانقين; ku, خانەقین, translit=Xaneqîn) is the central city of Khanaqin District in Diyala Governorate, Iraq, near the Iranian border (8 km) on the Alwand tributary of the Diyala River. The town is populate ...

(Khanikin) to Baghdad failed to materialise. From May–November 1916, the British consolidated a hold on Ottoman territory to the west of Iran around Basra and the confluence of the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

and Tigris at the head of the Persian Gulf. In 1917 the British campaign in Mesopotamia continued, with advances to Baghdad and towards the oilfields of Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second larg ...

as the campaign in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

led to the occupation of Palestine. A Russian invasion of 1915 from Caucasus established bases at Resht, Kazvin and Teheran and led to inconclusive operations between the Russians and Ottomans further west, closer to the Iranian–Ottoman border.

Caucasia

In January 1915, the British Cabinet had canvassed possible diversionary attacks against the Ottoman Empire after appeals for support from the Russian Empire. The British planned operations against the Ottoman Empire in theAegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

, eastern Mediterranean and a land invasion of the Levant from Egypt, combined with a Russian invasion from Caucasus towards Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

. In 1917, the Eastern Committee of the War Cabinet considered that British India had been drained of troops and decided to avoid committing more troops to Iran from Europe, by sending a mission of picked men to train local recruits at Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

(now Tbilisi), the capital of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. The War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

undertook to send officers and to organise local forces and replace the Russian Caucasus Army. Another force was to be raised in north-western Iran by Lieutenant-General W. R. Marshall, commander of the III (Indian) Corps of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force (MEF, Lieutenant-General Frederick Stanley Maude

Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude KCB CMG DSO (24 June 1864 – 18 November 1917) was a British Army officer. He is known for his operations in the Mesopotamian campaign during the First World War and for conquering Baghdad in 19 ...

); the French took responsibility for the area north of Caucasus.

In Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

, the local Christians had been sympathetic to the Russians and feared that a revival of Ottoman power would lead to more atrocities. It was believed in London that they would be willing recruits and that some Russian soldiers in the region might fight on for pay, despite the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

. On 13 April 1918, the Baku Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

Commune, a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and Left Socialist Revolutionary (SR) faction led by Stepan Shahumyan, was established in Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world an ...

, having come to power after the March Days. On 26 July, the Centrocaspian Dictatorship

The Centro-Caspian Dictatorship, also known as the Central-Caspian Dictatorship (russian: Диктатура Центрокаспия, ''Diktatura Tsentrokaspiya'') (Azerbaijani: Sentrokaspi Diktaturası), was a short-lived anti-Soviet administr ...

, an anti-Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

alliance of Russian Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

(Dashnaks), overthrew the Baku Commune in a bloodless coup. All the factions involved tried to gain support from about and Austro-Hungarian former prisoners of war. Those men willing to fight tended to be sympathetic to the Bolsheviks based in Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the ...

and at Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

, the terminus of the Trans-Caspian railway

The Trans-Caspian Railway (also called the Central Asian Railway, russian: Среднеазиатская железная дорога) is a railway that follows the path of the Silk Road through much of western Central Asia. It was built by ...

(Central Asian Railway). German and Ottoman armies in eastern Ukraine and Caucasus sent troops and diplomatic missions to Baku and further afield. By September 1918, the Ottoman force in Caucasus was the Eastern Army Group with the 3rd Army, comprising the 3rd Division, 10th Division and the 36th Caucasian Division, the 9th Army with the 9th Division, 11th Caucasian Division, 12th Division and the Independent Cavalry Brigade and the Army of Islam, with the 5th Caucasian Division and the 15th Division.

Prelude

Raising of Dunsterforce

Dunsterforce was formed in December 1917, to organise local replacements for the Russian Caucasus Army, that had collapsed in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the BolshevikOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

in the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years d ...

) and the Armistice of 15 December. If the new force managed to pass the Persian road from Baghdad to the Caspian Sea and through Baku to Tiflis, it might be impossible to keep the route open and so men of dash and intelligence were sought. About and were raised by quota from the various national and Dominion contingents in France, the largest number coming from the Australians. From and about twenty NCOs each, was requested from the First Australian Imperial Force

The First Australian Imperial Force (1st AIF) was the main expeditionary force of the Australian Army during the First World War. It was formed as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) following Britain's declaration of war on Germany on 15 Au ...

(AIF) and the Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December ...

, twelve officers and about ten NCOs from the New Zealand Expeditionary Force

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was the title of the military forces sent from New Zealand to fight alongside other British Empire and Dominion troops during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). Ultimately, the NZE ...

(NZEF) and several South Africans. The Canadians sent and of

to London by 13 January 1918. Until the "Hush-Hush Party" sailed for the Middle East on 29 January, the War Office kept the men incognito at the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, with no knowledge of their destination. Eleven Russians and an Iranian accompanied the party and in Egypt, another quota of twenty officers and forty NCOs joined from the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning o ...

, the group arriving in Basra on 4 March. The force moved up the Tigris to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

by 28 March and began training, having already begun learning Russian and Iranian on the voyage.

Dunsterville Mission

The commander of Dunsterforce, Major-General

The commander of Dunsterforce, Major-General Lionel Dunsterville

Major General Lionel Charles Dunsterville, (9 November 1865 – 18 March 1946) was a British Army officer, who led Dunsterforce across present-day Iraq and Iran towards the Caucasus and Baku during the First World War.

Early life

Lionel Ch ...

, had arrived in Baghdad from India, with his staff and the quota of officers and NCOs drawn from India and Mesopotamia on 18 January, carrying orders to proceed to Tiflis, as the British representative to the Trans-Caucasian Government. The MEF had occupied Baghdad since March 1917 and Marshall, who had taken over the MEF after Maude died in November 1917, sent parties forward to guard the section of the Persian road vacated by the Russian army. Marshall had severe doubts about Dunsterforce, calling it a "mad enterprise" concocted by the War Cabinet against an imagined threat, which would obstruct the main campaign in Mesopotamia. Dunsterville, on arrival at Baghdad, decided that due to the unsettled conditions in the region, he should confer urgently with the British representatives in Tiflis. On 27 January, Dunsterville had set off with eleven officers, four NCOs, four batmen, two clerks and in Ford cars and vans, through the advanced parties of the MEF guarding the road.

The decline of the Russian Army led the Ottomans to advance towards the Caspian Sea, where the Germans and Ottomans intended to capture Baku. Internal disagreements made their progress very slow and in the south after April, Armenians, Assyrians and some Russian troops, managed to stop the advance near Urmia

Urmia or Orumiyeh ( fa, ارومیه, Variously transliterated as ''Oroumieh'', ''Oroumiyeh'', ''Orūmīyeh'' and ''Urūmiyeh''.) is the largest city in West Azerbaijan Province of Iran and the capital of Urmia County. It is situated at an al ...

in north-west Iran, about from the Persian road. Iran was politically unstable and agents of the Central Powers attempted to exacerbate British problems in India; Dunsterforce intended to be an extension of the "cordon" in Iran, intended to prevent the unrest spreading to India. From the British railhead in Mesopotamia to the Caspian shore was about and the motor-column passed through the last British outpost at Pai Tak (also Pai Taq), then drove through Kermanshah on, Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') (Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ham ...

and then Kazvin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

further, to the Elburz

The Alborz ( fa, البرز) range, also spelled as Alburz, Elburz or Elborz, is a mountain range in northern Iran that stretches from the border of Azerbaijan along the western and entire southern coast of the Caspian Sea and finally runs nort ...

mountains, over the Bulagh Pass and into the jungle lowlands of Gilan Province, home of the Jungle Movement of Gilan (Jangali) led by Kuchik Khan Around Resht

Rasht ( fa, رشت, Rašt ; glk, Rəšt, script=Latn; also romanized as Resht and Rast, and often spelt ''Recht'' in French and older German manuscripts) is the capital city of Gilan Province, Iran. Also known as the "City of Rain" (, ''Ŝahre B ...

and Bandar-e Anzali

Bandar-e Anzali ( fa, بندرانزلی, also Romanized as Bandar-e Anzalī; renamed as Bandar-e Pahlavi during the Pahlavi dynasty) is a city of Gilan Province, Iran. At the 2011 census, its population was 144,664.

Anzali is one of the mos ...

on the Caspian coast, German and Austrian agents had established a measure of influence with the Jangali. Dunsterville discovered that thousands of Russian troops, formerly part of the occupation force in northern Iran, under General Nikolai Baratov

Nikolai Nikolaevich Baratov (russian: Николай Николаевич Баратов) (February 1, 1865 – March 22, 1932) was an Imperial Russian Army general during World War I and the Russian Civil War.

Early career

Baratov was born i ...

, were being allowed free passage and on 17 February, the Dunsterville party reached Bandar-e Anzali.

After contemplating the hijack of a ship to run the gauntlet of Bolshevik-operated coastal craft, Dunsterville decided not to risk alienating local opinion and turned back, intending to meet the party en route from Europe and make arrangements in Iran, while waiting for another chance to reach Tiflis. On 20 February, the party dodged the local authorities and returned to Hamadan, where it could use MEF and Russian army wireless stations, to keep in touch with Baghdad. It had become clear that there was little chance that the Russians formerly under Baratov could be induced to remain on service and that only Colonel Lazar Bicherakov and some of his Cossacks were willing to continue. On 11 February, Bicherakov flew to Baghdad and told Marshall that the Cossacks were willing to act as rearguard for the Russians before leaving and that the Tiflis initiative was doomed to failure. Marshall wanted an advance on Mosul to protect the Persian road but was over-ruled, in preference for operations in Palestine and at Hamadan, Dunsterville claimed that the Iranian public welcomed British protection and requested that he might wait at Hamadan to try again.

To gain the support of the Iranian public, Dunsterville made an effort to relieve the famine, caused partly by a drought and partly by Russian and Ottoman military operations in north-west Iran. The Dunsterville Mission had plenty of money and recruited local labour to repair roads. By a ruse, Dunsterville got the local grain merchants, mostly supporters of the Democratic Party and in the pay of the Germans, to stop hoarding, which proved very popular. The Democrats retaliated by claiming that the British had poisoned the wheat and sniped at the British in Hamadan but public support for the British increased as the famine relief measures took effect. The Dunsterville Mission was also able to establish an intelligence organisation that saw all telegrams and letters concerning the mission. After the Bicherakov Cossack detachment moved from Kermanshah to Kazvin and blocked the Jangalis from using the Teheran road, the mission was able to arrest the passage of German and Ottoman agents with local levies of Christian Assyrians for local order and security duties. The prisoners were guarded a party of the 1/4th Hampshire and the "Irregulars", a military force was raised from the hill peoples of the north-west closer to the Ottoman border, to oppose an Ottoman move against the Persian road from Armenia.

Baratov sold Dunsterville most of the weapons and supplies of the Russian Army but some were also traded by Russian soldiers to the Persian locals and the Kurdish hill peoples, leaving them exceptionally well armed. By the end of March, all but the Bicherakov Cossack detachment at Kazvin had withdrawn and the MEF extended its hold on the road to Kermanshah, with the 36th Brigade. Dunsterville borrowed some infantry and cavalry and Bicherakov agreed to remain at Kazvin, until British troops could take over. Twenty officers and twenty NCOs of Dunsterforce arrived by Ford car on 3 April, the rest of the force making their way on foot with a mule train, all arriving by 25 May. By the time that the rest of Dunsterforce had arrived, the local and international situation had changed; the success of the German spring offensive in France leading the Georgians to bid for German support; in May the Germans took over part of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. The Ottomans repudiated the treaty of Brest Litovsk and began to organise Tartars into the

After contemplating the hijack of a ship to run the gauntlet of Bolshevik-operated coastal craft, Dunsterville decided not to risk alienating local opinion and turned back, intending to meet the party en route from Europe and make arrangements in Iran, while waiting for another chance to reach Tiflis. On 20 February, the party dodged the local authorities and returned to Hamadan, where it could use MEF and Russian army wireless stations, to keep in touch with Baghdad. It had become clear that there was little chance that the Russians formerly under Baratov could be induced to remain on service and that only Colonel Lazar Bicherakov and some of his Cossacks were willing to continue. On 11 February, Bicherakov flew to Baghdad and told Marshall that the Cossacks were willing to act as rearguard for the Russians before leaving and that the Tiflis initiative was doomed to failure. Marshall wanted an advance on Mosul to protect the Persian road but was over-ruled, in preference for operations in Palestine and at Hamadan, Dunsterville claimed that the Iranian public welcomed British protection and requested that he might wait at Hamadan to try again.

To gain the support of the Iranian public, Dunsterville made an effort to relieve the famine, caused partly by a drought and partly by Russian and Ottoman military operations in north-west Iran. The Dunsterville Mission had plenty of money and recruited local labour to repair roads. By a ruse, Dunsterville got the local grain merchants, mostly supporters of the Democratic Party and in the pay of the Germans, to stop hoarding, which proved very popular. The Democrats retaliated by claiming that the British had poisoned the wheat and sniped at the British in Hamadan but public support for the British increased as the famine relief measures took effect. The Dunsterville Mission was also able to establish an intelligence organisation that saw all telegrams and letters concerning the mission. After the Bicherakov Cossack detachment moved from Kermanshah to Kazvin and blocked the Jangalis from using the Teheran road, the mission was able to arrest the passage of German and Ottoman agents with local levies of Christian Assyrians for local order and security duties. The prisoners were guarded a party of the 1/4th Hampshire and the "Irregulars", a military force was raised from the hill peoples of the north-west closer to the Ottoman border, to oppose an Ottoman move against the Persian road from Armenia.

Baratov sold Dunsterville most of the weapons and supplies of the Russian Army but some were also traded by Russian soldiers to the Persian locals and the Kurdish hill peoples, leaving them exceptionally well armed. By the end of March, all but the Bicherakov Cossack detachment at Kazvin had withdrawn and the MEF extended its hold on the road to Kermanshah, with the 36th Brigade. Dunsterville borrowed some infantry and cavalry and Bicherakov agreed to remain at Kazvin, until British troops could take over. Twenty officers and twenty NCOs of Dunsterforce arrived by Ford car on 3 April, the rest of the force making their way on foot with a mule train, all arriving by 25 May. By the time that the rest of Dunsterforce had arrived, the local and international situation had changed; the success of the German spring offensive in France leading the Georgians to bid for German support; in May the Germans took over part of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. The Ottomans repudiated the treaty of Brest Litovsk and began to organise Tartars into the Islamic Army of the Caucasus

The Islamic Army of the Caucasus ( az, Qafqaz İslam Ordusu; Turkish: ''Kafkas İslâm Ordusu'') (also translated as ''Caucasian Army of Islam'' in some sources) was a military unit of the Ottoman Empire formed on July 10, 1918. The Ottoman Mi ...

on 25 May, to attack Baku and Iran, making a British move to Tiflis even less likely.

15th Indian Division

The 15th Indian Division was an infantry division of the British Indian Army that saw active service in the First World War. It served in the Mesopotamian Campaign on the Euphrates Front throughout its existence. It did not serve in the Second ...

of the MEF, surrounded an Ottoman force in the action of Khan Baghdadi

The action of Khan Baghdadi was an engagement during the Mesopotamian campaign in World War I.

Khan Baghdadi

The 15th Indian Division had been at Ramadi since its capture of the town in September 1917. On 9 March 1918, it advanced and occup ...

and took In April, the 2nd Ottoman Division was forced back from the Persian road, after which the MEF advanced into Kurdistan and tried to block the Ottoman retreat towards Kirkuk

Kirkuk ( ar, كركوك, ku, کەرکووک, translit=Kerkûk, , tr, Kerkük) is a city in Iraq, serving as the capital of the Kirkuk Governorate, located north of Baghdad. The city is home to a diverse population of Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds ...

. Marshall was ordered to advance to Kirkuk, to divert Ottoman forces from their advance through Armenia to the Caspian Sea. The MEF took the town unopposed on 7 May, then retired to Tuz Khormato

Tuz Khurmatu ( ar, طوزخورماتو, tr, Tuzhurmatu, ku, دووزخورماتوو, translit=Duz Xurmatû, also spelled as Tuz Khurma and Tuz Khormato) is the central city of Tooz District in Saladin Governorate, Iraq, located 55 miles (88 ...

and Kifiri, due a shortage of troops and supplies.

The War Office urged Marshall to send a brigade to Dunsterville but he claimed that mounted in Fords and a force of armoured cars, would be sufficient to get beyond Kermanshah. The force could to the Caspian Sea by June and then the waters could be controlled by arming ships; if he was wrong, reinforcements could be sent later. During the discussions, the Bolsheviks in Caucasus requested that Bicherakov attack the Jangalis to protect Baku, to which he agreed, in return for their acquiescence in British involvement. Dunsterville wanted to depart on 30 May but was delayed by the War Office until 1 June and allowed to move on, provided that the road was adequately guarded. Ottoman forces were west of the road at Tabriz and the Jangalis held the road at Manjil

Manjil ( fa, Manjil, also Romanized as Manjīl and Menjīl ; derived from Manzil) is a city in the Central District of Rudbar County, Gilan Province, Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 16,028, in 4,447 families.

Geography

Manjil is k ...

. Just after the fourth party of Dunsterforce had arrived, Dunsterville sent parties of his Officers and NCOs with pack-wireless stations, to Zenjan and Bijar, about north-west of Kazvin and Hamadan. Their objective was to recruit local Kurds, to bar the two tracks through Kurdistan against an Ottoman advance. Sehneh, on a southern track from Urmia to Kermanshah, was left until July, when Marshall sent troops to occupy the town.

Operations

Dunsterforce

The Dunsterforce parties moved off via Zenjan, with their destinations secret until they were on their way, just after the fourth group of Dunsterforce arrived. Soon after the party for Zenjan arrived it was sent on another to Mianeh about from Tabriz and the Bijar party pressed on, using a track last reported on by British intelligence in 1842, arriving on 18 June. The Ottoman advance further north on Baku, was opposed by about and Bolshevik troops with about and pieces. Dunsterville proposed to reconnoitre, regardless of the reluctance of the Russian Bolshevik government to allow British interference. On 12 June, the Bicherakov Cossacks advanced from Kazvin and defeated the Jangai at Manjil bridge, reaching Bandar-e Anzali a few days later. Bicherakov took ship for Baku, styled himself a Bolshevik, was appointed commander of the Red Army in Caucasus, then returned to Bandar-e Anzali. In June, the

The Dunsterforce parties moved off via Zenjan, with their destinations secret until they were on their way, just after the fourth group of Dunsterforce arrived. Soon after the party for Zenjan arrived it was sent on another to Mianeh about from Tabriz and the Bijar party pressed on, using a track last reported on by British intelligence in 1842, arriving on 18 June. The Ottoman advance further north on Baku, was opposed by about and Bolshevik troops with about and pieces. Dunsterville proposed to reconnoitre, regardless of the reluctance of the Russian Bolshevik government to allow British interference. On 12 June, the Bicherakov Cossacks advanced from Kazvin and defeated the Jangai at Manjil bridge, reaching Bandar-e Anzali a few days later. Bicherakov took ship for Baku, styled himself a Bolshevik, was appointed commander of the Red Army in Caucasus, then returned to Bandar-e Anzali. In June, the Malleson mission

The Malleson mission was a military action by a small autonomous force of British troops, led by General Wilfrid Malleson, operating against Bolshevik forces over large distances in Transcaspia (modern Turkmenistan) between 1918 and 1919.

Backg ...

, an Indian Army force under General Wilfrid Malleson

Major-General Sir Wilfrid Malleson (8 September 1866 – 24 January 1946) was a major-general in the British Indian Army who led a mission to Turkestan during the Russian Civil War.

Life

Malleson born in Baldersby, Yorkshire. was commissi ...

, established a base to the east of Bandar e-Anzali in Mashhad

Mashhad ( fa, مشهد, Mašhad ), also spelled Mashad, is the second-most-populous city in Iran, located in the relatively remote north-east of the country about from Tehran. It serves as the capital of Razavi Khorasan Province and has a po ...

, to counter German and Ottoman encroachments in Transcaspia

The Transcaspian Oblast (russian: Закаспійская область), or just simply Transcaspia (russian: Закаспія), was the section of Russian Empire and early Soviet Russia to the east of the Caspian Sea during the second half of ...

(now Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

).

Dunsterville was in contact with the Armenian National Council in Baku and urged Marshall in Mesopotamia to send infantry and artillery but Marshall refused and in June sent only the already promised, two companies each of the 1st/4th Hampshire and 1st/2nd Gurkhas, two mountain guns of the 21st Battery and supplies in the vans; the troops took over guarding the road up to Resht. The War Office and the War Cabinet questioned Marshall's judgement and asked Dunsterville directly, what it would take to control the Caspian Sea and destroy the oilfields. Dunsterville urged a forward policy but not the sabotage of the oil as this was inimical to the interests of the populations he was trying to recruit against the Ottomans. Marshall then offered the 39th Infantry Brigade of the 13th (Western) Division

The 13th (Western) Division was one of the Kitchener's Army divisions in the First World War, raised from volunteers by Lord Kitchener. It fought at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia (including the capture of Baghdad) and Persia.

War service 1914� ...

and artillery, provided that it could be supplied locally. (The brigade was detached on 1 July and set off in stages from the Brigade HQ arriving five days later.) Along with training and leadership, Dunsterforce was to occupy the Baku oil fields

The petroleum industry in Azerbaijan produces about of oil per day and 29 billion cubic meters of gas per year as of 2013. Azerbaijan is one of the birthplaces of the oil industry.

The State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (known as SOCAR) i ...

, to deny oil and the local cotton crop to the Germans and Ottomans. Dunsterforce was to operate against the Ottomans in the west and hold a line from Batum

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of t ...

to Tiflis, Baku and Krasnovodsk (on the opposite side of the Caspian Sea) to Afghanistan.

Bicherakov and the Cossacks left for Baku and were replaced by British troops at Bandar e-Anzali, as Dunsterville waited for news from Baku of the local factions and changes in their views about British involvement. Although Dunsterville and the British consul at Baku wanted to conciliate the Bolsheviks at Bandar e-Anzali, the War Cabinet wanted him to suppress them but communication was difficult, with the Bolsheviks in control of the transmitter at the port. On 25 July about attacked the British garrison of at Resht and were repulsed; ten days later, Dunsterville gained proof of Bolshevik involvement, arrested the committee in Bandar e-Anzali, seized the wireless and installed Australian signallers. At Baku the situation had changed when the Ottoman advance on the oilfields began. Bicherakov and the Cossacks, with help from four Dunsterforce armoured cars, tried to stop the advance but the local troops ran away. Also on 25 July, Bicherakoff and a few British officers with the four Dunsterforce armoured cars, staged another coup d'état in Baku. A Centrocaspian Dictatorship was installed, Bicherakoff appealed for British aid and sent ships to Bandar-e Anzali to pick up the first troops. Dunsterville sent his intelligence officer, Lieutenant-Colonel C. B. Stokes and all the available to Baku, with news that the brigade and artillery he had requested were on the way.

Urmia Crisis

In 1918, Urmia was defended by Christian (

In 1918, Urmia was defended by Christian (Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

) Assyrians of the Urmia villages, that had endured a siege by local Muslim rivals, until the Russian army reached Urmia in May 1915. About Assyrians from the Hakkiari Mountains south of Lake Van, declared war on the Ottomans in 1915 and then retreated towards the Russians, when they were unable to break through. These refugees settled at Salmas

Salmas ( fa, سلماس; ; ; ; syr, ܣܵܠܵܡܵܣ, Salamas) is the capital of Salmas County, West Azerbaijan Province in Iran. It is located northwest of Lake Urmia, near Turkey. According to the 2019 census, the city's population is 127,86 ...

, north of Urmia and attacked the local population, who began to call them Jelus. After the Russian armies collapsed, the Ottomans drove another from around Lake Van, who joined the earlier fugitives. Tsarist officers reorganised the two groups defending Salmas until June, when they retreated to the group at Urmia. A British officer had been sent from Tiflis with offers of organisation and help but the assurances were not honoured, which reduced British prestige. A local teacher-turned-general, Agha Petros, managed to unite the three factions and repulse fourteen Ottoman attacks.

On 8 July, before Dunsterforce set off for Baku, Lieutenant K. M. Pennington flew to the Jelus at Urmia, who were under siege by the 5th Ottoman Division and the 6th Ottoman Division of the Ottoman army. Dunsterville offered to send money, machine-guns and ammunition north from Bijar, if Petross pushed a force through the Ottoman siege lines around Lake Urmia, to meet the column and escort it in. The column departed from Bijar on 19 July, commanded by Major J. C. More, carrying £45,000 in Iranian silver Dinar

The dinar () is the principal currency unit in several countries near the Mediterranean Sea, and its historical use is even more widespread.

The modern dinar's historical antecedents are the gold dinar and the silver dirham, the main coin ...

, twelve Lewis guns and of ammunition, accompanied by Captain Stanley Savige

Lieutenant General Sir Stanley George Savige, (26 June 1890 – 15 May 1954) was an Australian Army soldier and officer who served in the First World War and Second World War.

In March 1915, after the outbreak of the First World War, Savi ...

, five Dunsterforce officers and fifteen NCOs, escorted by a squadron of the 14th (King's) Hussars (Colonel Bridges). The British reached the rendezvous at Sain Kala on 23 July as arranged but there was no reception party waiting. After a couple of days, Bridges decided that he must return before the grain supply for the horses ran out.

Savige and the Dunsterforce party got permission to go on alone, when the column had retired to Takan Tepe, where his party and the convoy was allowed to remain, with a squadron of cavalry. Savige judged that the Assyrians could still reach them and in the meantime, they would raise a local force to get to Urmia if necessary. Recruitment began and on 1 August, news arrived of a battle south of Lake Urmia, that Savige took to be the Assyrian break out attempt and the party moved north the next day. Aga Petros and the Assyrians arrived on 3 August and next day the march to Urmia began; at dusk near Sain Kala, Petros was aghast to see Assyrian women on the road. The Ottomans had captured Urmia in his absence and the had fled. On 5 August, the British saw a multitude on the road from Urmia, who said that the far end was some miles back, with a rear-guard commanded by Dr W. A. Shedd an American missionary, trying to protect the refugees from local Kurdish and Iranian attacks. The Dunsterforce party went to join the rearguard, while the cavalry protected the main body. A hundred men promised by Petros had already gone to find their families, when the rearguard moved at dawn on 6 August.

The Savige party (two officers and six NCOs), found the tail of the refugee column up the road, with Mrs Shedd encouraging wounded refugees to keep going and the Doctor and men on a ridge, waiting for the next attack. Savige took over the refugee guard and pressed on for about to a village that was being looted by local mounted irregulars. Savige and his exiguous force forced the horsemen out of the village and held them off until later the next day and then retreated, finding that the Assyrians had pillaged the villages in the past, as ruthlessly as the survivors had been taking reprisals against them as they fled from Urmia. Soon after dawn the next day, advanced down the road and others moved past on the flanks. Savige and the party hurried back to a ridge behind a village and commenced a rear-guard action with some of the refugees, while the others ran away. Many well-armed Assyrians pushed to the head of the column, seizing the best horses and leaving women and children to the bandits; having fought in the defence of Urmia, Petros lost control of them once they were under British protection. During the first day, Savige and a local leader got several Assyrians (at gunpoint) to charge the pursuers, as a message was got back to the Hussars asking for support.

After seven hours of fighting, having been pressed back to the tail of the column, twelve British cavalry appeared on the next ridge back, having heard of the request for help and arriving just in time, as the rearguard was exhausted. The cavalry held off the attackers and then fifty men sent by Aga Petros arrived and relieved Savige and the Dunsterforce party. Dr Shedd reached the British encampment but during the night died of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

and was buried nearby. Attacks on the refugee column by Ottoman troops and local Kurds diminished but for the rest of the march there were frequent attempts to take loot and rustle cattle before the escort could intervene. The cavalry guarded the money and the Dunsterville party provided the rearguard but was not able to protect wounded or exhausted women and children, who had been abandoned by their men, from being murdered. Short of Bijar, an attack by hillmen was deterred, by a show of force by Agha Petros and on 17 August, the rearguard entered Bijar, by when the Dunsterforce members were so worn out that only four regained their fitness before the end of the war. Of about who fled from Urmia, perhaps the Persian road.

Urmia Brigade

At Bijar, Lieutenant-Colonel McCarthy tried with Agha Petros to recruit from the Assyrians a force to recapture Urmia but found that the best men were leading the retreat and would not stop. McCarthy returned to Hamadan ready to stop them with machine-guns if necessary and the best men were press-ganged at bayonet-point by a platoon of the 1st/4th Hampshire. The "recruits" were formed at Abshineh, into the Urmia Brigade (Major G. S. Henderson) of and , trained and commanded through a small Dunsterforce detachment. The remaining Assyrians were sent on to a refugee camp atBaqubah

Baqubah ( ar, بَعْقُوبَة; BGN: Ba‘qūbah; also spelled Baquba and Baqouba) is the capital of Iraq's Diyala Governorate. The city is located some to the northeast of Baghdad, on the Diyala River. In 2003 it had an estimated populat ...

near Baghdad and the Dunsterforce personnel attempted to prevent the Assyrians from getting into Baghdad and plundering local Iranians. The Dunsterforce officers and NCOs were unscrupulous, using training methods like "young sheepdogs practising on the fowls" but had made little progress, when two of the new battalions were sent to counter the threat of an Ottoman advance towards the Persian road; the third battalion moved to Bijar in October. (Eventually the Urmia Brigade returned to Mesopotamia to prepare to recapture Urmia, when the armistice made the attempt unnecessary and the brigade disbanded)

Baku