Douglas Edwards on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

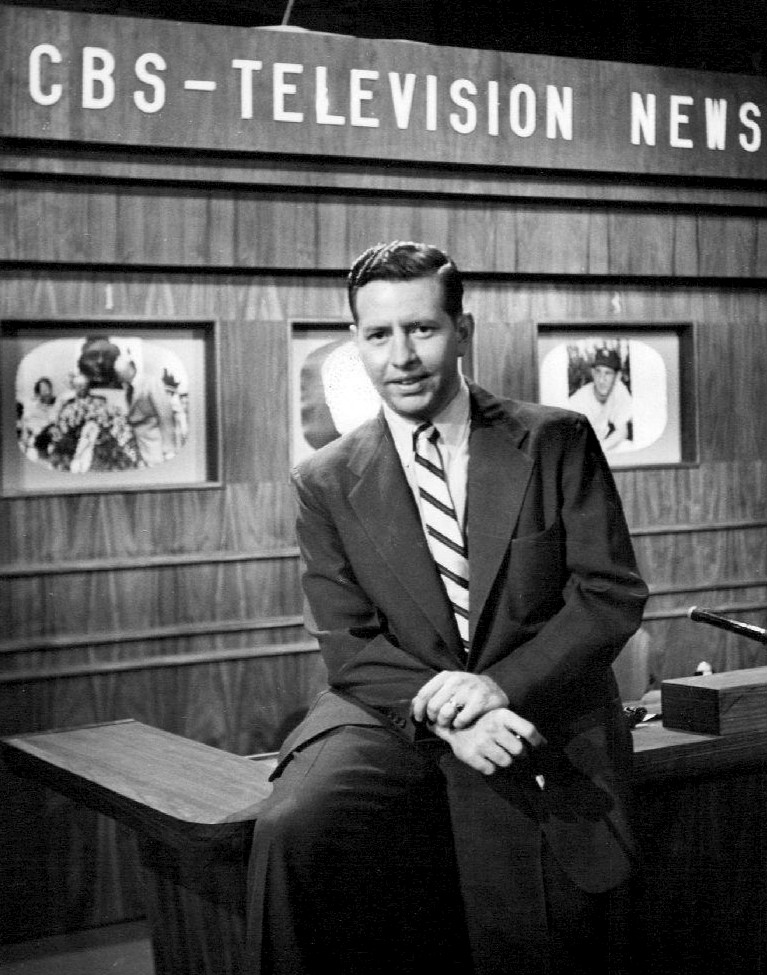

Douglas Edwards (July 14, 1917 – October 13, 1990) was an American radio and television newscaster and correspondent who worked for the

CBS News (Manhattan, New York), July 13, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2021. Initially aired as a 15-minute program under the title ''CBS Television News'', the broadcast evolved into the ''

The Douglas Edwards Archives, Friedsam Memorial Library, St. Bonaventure University, Allegany, New York. Retrieved January 11, 2021. His mother had been married previously, but her first husband died in 1906 from

"Douglas Edwards, 73; TV Pioneer"

''Los Angeles Times'', October 14, 1990, p. A37A. Using a small

Edwards returned to the United States from his overseas radio assignments in May 1946. By 1947, as CBS's top correspondents and commentators continued to shun the fledgling medium of television, Edwards was chosen by network executives to work with director Don Hewitt in presenting a televised news program every weeknight and to host CBS's televised coverage of the 1948 Democratic and Republican national conventions. While Edwards served as "anchor" of the programs, that term was actually not used within the context of newscasting, at least not consistently, until 1952, when CBS News chief Sig Mickelson reportedly applied it in describing

Edwards returned to the United States from his overseas radio assignments in May 1946. By 1947, as CBS's top correspondents and commentators continued to shun the fledgling medium of television, Edwards was chosen by network executives to work with director Don Hewitt in presenting a televised news program every weeknight and to host CBS's televised coverage of the 1948 Democratic and Republican national conventions. While Edwards served as "anchor" of the programs, that term was actually not used within the context of newscasting, at least not consistently, until 1952, when CBS News chief Sig Mickelson reportedly applied it in describing

After he retired from CBS, Edwards and his wife May left their home in

After he retired from CBS, Edwards and his wife May left their home in

MetaCafe: "Flight of Sputnik I,"

CBS News (Douglas Edwards reporting), 2 October 1957 *

Edward's farewell World Tonight radio broadcast on April 1, 1988

NPR's 1988 ''War of the Worlds'' broadcast

with Edwards coming in at about 26:03. *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edwards, Douglas 1917 births 1990 deaths CBS News people American television news anchors American television reporters and correspondents Peabody Award winners Deaths from cancer in Florida People from Ada, Oklahoma

Columbia Broadcasting System

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

(CBS) for more than four decades. After six years on CBS Radio

CBS Radio was a radio broadcasting company and radio network operator owned by CBS Corporation and founded in 1928, with consolidated radio station groups owned by CBS and Westinghouse Broadcasting/Group W since the 1920s, and Infinity Broad ...

in the 1940s, Edwards was among the first major broadcast journalists to move into the rapidly expanding medium of television. He is also generally recognized as the first presenter or "anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek á ...

" of a nationally televised, regularly scheduled newscast by an American network. Edwards presented news on CBS television every weeknight for 15 years, from March 20, 1947 until April 16, 1962."Celebrating Douglas Edwards, a CBS legend"CBS News (Manhattan, New York), July 13, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2021. Initially aired as a 15-minute program under the title ''CBS Television News'', the broadcast evolved into the ''

CBS Evening News

The ''CBS Evening News'' is the flagship evening television news program of CBS News, the news division of the CBS television network in the United States. The ''CBS Evening News'' is a daily evening broadcast featuring news reports, feature st ...

'' and in 1963 expanded to a 30-minute format under Walter Cronkite

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. (November 4, 1916 â July 17, 2009) was an American broadcast journalist who served as anchorman for the ''CBS Evening News'' for 19 years (1962â1981). During the 1960s and 1970s, he was often cited as "the mo ...

, who succeeded Edwards as anchor of the newscast. Although Edwards left the evening news in 1962, he continued to work for CBS for another quarter of a century, presenting news reports on both radio and daytime television, and editing news features, until his retirement from the network in 1988.

Early life and radio career

Born in Ada, Oklahoma in 1917, Edwards was the only child of Alice (née Donaldson) and Tony M. Edwards, both of whom were public school teachers."Douglas Edwards Chronology"The Douglas Edwards Archives, Friedsam Memorial Library, St. Bonaventure University, Allegany, New York. Retrieved January 11, 2021. His mother had been married previously, but her first husband died in 1906 from

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

. As a result of that earlier marriage, Edwards grew up with a half-brother, John W. Moore, who was 12 years older. Tragically, Alice also lost her second husband to disease. When Edwards was an infant, his father died of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. Now twice-widowed, Alice continued teaching to support herself and her two sons. By 1930, however, she left Oklahoma and moved with Edwards and John to New Mexico for a better teaching position, one as an instructor at a normal school

A normal school or normal college is an institution created to train teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. In the 19th century in the United States, instruction in normal schools was at the high school level, turni ...

in Silver City. Edwards lived in Silver City for only two years, but during that time he developed a keen interest in radio technology and programming.Oliver, Myrna"Douglas Edwards, 73; TV Pioneer"

''Los Angeles Times'', October 14, 1990, p. A37A. Using a small

crystal radio

A crystal radio receiver, also called a crystal set, is a simple radio receiver, popular in the early days of radio. It uses only the power of the received radio signal to produce sound, needing no external power. It is named for its most imp ...

set that he acquired, Edwards began to monitor each day a wide range of regular broadcasts and special events, a routine made easier by Silver City's high elevation, which allowed him to tune in to distant stations transmitting from Los Angeles, Denver, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and elsewhere. "What an experience that was", he recalled in a later interview, "transfixed by broadcasts I could bring in from faraway places."

First broadcast experience, 1932

In 1932, Douglas moved with his mother to southeastern Alabama, where she had accepted a job as a school principal in the town ofTroy

Troy ( el, ΤÏοία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: ğ«ğğ¿ğ ''TruwiÅ¡a'') or Ilion ( el, Îλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: ğ¾ğ»ğ ''WiluÅ¡a'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of à ...

. Half-brother John, now 26 years old, chose to remain in New Mexico. Douglas spent his teenage years in Troy and continued his radio hobby, which he still regarded as a "new world", still "mesmerizing". Martin Weil, a staff writer for ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' who compiled a biography on Edwards and wrote the newscaster's 1990 obituary for the newspaper, described the teenager's ongoing fascination with the medium:

At Troy's small, makeshift radio station in 1932, the teenage Edwards was paid $2.50 a week to be a "junior announcer", a disc jockey

A disc jockey, more commonly abbreviated as DJ, is a person who plays recorded music for an audience. Types of DJs include radio DJs (who host programs on music radio stations), club DJs (who work at a nightclub or music festival), mobil ...

, and to fill any lapses during broadcasts by reading poetry and even singing occasionally. Describing those formative days on radio decades later, Edwards said he found the experience thrilling, although he admitted he did not sing well, adding "but I got by, got fan mail, and the ego was nourished."

College years and hiring by CBS, 1942

Following his graduation from high school, Edwards managed to enroll briefly at theUniversity of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, or Bama) is a public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of Alabama is the oldest and largest of the publ ...

to take pre-med

Pre-medical (often referred to as pre-med) is an educational track that undergraduate students in the United States pursue prior to becoming medical students. It involves activities that prepare a student for medical school, such as pre-med course ...

courses and then attended evening classes on journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the " news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (p ...

at the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

and at Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

in Atlanta before abandoning his hopes for a college degree due to a lack of money amidst the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. He nevertheless remained intent on working in radio, and between 1935 and 1940, he found employment, first at a small station in Dothan, Alabama

Dothan () is a city in Dale, Henry, and Houston counties and the Houston county seat in the U.S. state of Alabama. It is Alabama's eighth-largest city, with a population of 71,072 at the 2020 census. It is near the state's southeastern corner ...

; then at WSB in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

; and next, much farther north in Michigan, at WXYZ in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United StatesâCanada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

, where he served as a newscaster and announcer. In 1942, shortly after returning to Atlanta to work as an assistant news editor at WSB, he accepted an offer from CBS Radio

CBS Radio was a radio broadcasting company and radio network operator owned by CBS Corporation and founded in 1928, with consolidated radio station groups owned by CBS and Westinghouse Broadcasting/Group W since the 1920s, and Infinity Broad ...

to move to New York to be an assistant announcer and understudy to journalist John Charles Daly, the presenter of the network's nightly 15-minute news program ''The World Today''. When Daly was reassigned by CBS as a war correspondent and sent overseas the following year, Edwards was promoted as his replacement on ''The World Today'', as well as host of the Sunday afternoon program ''World News Today'' and of the Sunday night program ''Report to the Nation''. Two years later, Edwards was also dispatched overseas, to London, to cover the final weeks of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countriesâincluding all of the great power ...

with CBS foreign correspondent Edward R. Murrow

Edward Roscoe Murrow (born Egbert Roscoe Murrow; April 25, 1908 â April 27, 1965) was an American broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He first gained prominence during World War II with a series of live radio broadcasts from Europe f ...

. At the end of the conflict in Europe in May 1945, Edwards was then appointed the network's news bureau chief in Paris and assigned to cover post-war elections in Germany and the start of the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

.

Anchor for televised CBS newscasts, 1947-1962

Walter Cronkite

Walter Leland Cronkite Jr. (November 4, 1916 â July 17, 2009) was an American broadcast journalist who served as anchorman for the ''CBS Evening News'' for 19 years (1962â1981). During the 1960s and 1970s, he was often cited as "the mo ...

's role in the network's political convention coverage. Such news terminology developed quickly in those early days of broadcasting daily news on television, a time fraught with uncertainties not only about the technologies required to present reports in a visual medium, but also about the most effective means of delivering those reports to viewers. Edwards' friends and CBS colleagues in the late 1940s were quick to suggest ways he could make his reports more interesting to his audience. "I remember", he stated years later, "guys coming up with brainstorms like wanting me to wear a football helmet to report the football scores."

In viewership ratings, Edwards' newscasts were soon eclipsed by NBC News

NBC News is the news division of the American broadcast television network NBC. The division operates under NBCUniversal Television and Streaming, a division of NBCUniversal, which is, in turn, a subsidiary of Comcast. The news division's v ...

with its ''Camel News Caravan

''The Camel News Caravan'' or ''Camel Caravan of News'' was a 15-minute American television news program aired by NBC News from February 16, 1949 to October 26, 1956. Sponsored by the Camel cigarette brand and anchored by John Cameron Swayze, i ...

'' presented by John Cameron Swayze

John Cameron Swayze (April 4, 1906 â August 15, 1995) was an American news commentator and game show panelist during the 1940s and 1950s who later became best known as a product spokesman.

Early life

Born in Wichita, Kansas, Swayze was the ...

. CBS, though, quickly regained its lead due in no small part to Edwards' ongoing efforts to cover major events personally. Among the many news stories that Edwards covered in those years in the dual role of newscaster-reporter were his trip to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

in 1949, the attempted assassination of Harry S. Truman in November 1950, and the coronation of Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 â 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

in June 1953. He also reported on cultural events such as the Miss America Pageant

Miss America is an annual competition that is open to women from the United States between the ages of 17 and 25. Originating in 1921 as a "bathing beauty revue", the contest is now judged on competitors' talent performances and interviews. As ...

(five times). The nightly 15-minute ''Douglas Edwards with the News'' was watched by nearly 30 million viewers by the mid-1950s, as the newscaster continued his practice of periodically covering major new stories himself. In July 1956, while stationed on a helicopter hovering over the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Massachusetts, Edwards reported the sinking of the '' SS Andrea Doria'', on-site coverage that received widespread public attention and critical praise. Despite such efforts and positive reactions to his stories, viewership of Edwards' televised newscasts began to decline by the late 1950s as NBC's new '' Huntley-Brinkley Report''âCBS News' chief competitorâbegan to attract increasingly larger audiences.

Edwards' last televised evening newscast aired on April 13, 1962 The following Monday, on April 16, Walter Cronkite officially replaced him as anchor of the telecast. The next year, on September 2, 1963, the program was retitled '' CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite''. It was also rescheduled to broadcast at 6:30 p.m. instead of its normal 7:30 time slot, and its 15-minute format was expanded to 30 minutes, a change that made it the first half-hour weeknight news show on American television.

Continuing work for CBS, 1962-1988

Edwards' departure from ''CBS Evening News'' did not end his work for the network either on television or radio. For several years, both during his time as network anchor and afterwards, he anchored the local late news team onWCBS-TV

WCBS-TV (channel 2) is a television station in New York City, serving as the flagship of the CBS network. It is owned and operated by the network's CBS News and Stations division alongside Riverhead, New Yorkâlicensed independent station W ...

, channel 2, the network's flagship station in New York City. He continued to present ''The World Tonight'' on CBS Radio, and from April 1962 into the 1980s, he presented five-minute weekday national television reports: ''The CBS Afternoon News with Douglas Edwards'', and later, after schedule adjustments, ''The CBS Mid-Day News with Douglas Edwards'', followed by ''The CBS Mid-Morning News with Douglas Edwards''. Beginning in 1979, he hosted the CBS Sunday morning news and talk show series ''For Our Times'', and in 1987 he served as co-anchor with Faith Daniels

Faith Daniels (born March 9, 1957) is an American television news anchor, reporter, and talk show host.

Early life

Daniels was born to an unwed mother and lived eight months in a Catholic orphanage before being adopted by Steven A. Skowronski, a ...

for ''CBS Morning News

The ''CBS Morning News'' is an American early-morning news broadcast presented weekdays on the CBS television network. The program features late-breaking news stories, national weather forecasts and sports highlights. Since 2013, it has been anc ...

''."Former CBS newsman Douglas Edwards dies at 73"United Press International

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 2 ...

(UPI), Boca Raton, Florida. Retrieved January 11, 2021. Edwards continued until his retirement in April 1988 to anchor ''Newsbreak'', a televised 74-second weekday segment that highlighted the day's top news stories.Douglas Edwards ChronologyNew Canaan, Connecticut

New Canaan () is a town in Fairfield County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 20,622 according to the 2020 census.

About an hour from Manhattan by train, the town is considered part of Connecticut's Gold Coast. The town is bound ...

, and relocated to Sarasota, Florida

Sarasota () is a city in Sarasota County, Florida, Sarasota County on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The area is renowned for its cultural and environmental amenities, beaches, resorts, and the Sarasota School of Architecture. The c ...

. Six months later, on October 30, 1988, he returned to radio to perform as himself in National Public Radio

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other n ...

's re-creation of Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 â October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

' 1938 CBS broadcast of ''The War of the Worlds

''The War of the Worlds'' is a science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells, first serialised in 1897 by ''Pearson's Magazine'' in the UK and by ''Cosmopolitan (magazine), Cosmopolitan'' magazine in the US. The novel's first appear ...

''. Directed by David Ossman

David Ossman (born December 6, 1936 in Santa Monica) is an American writer and comedian, best known as a member of the Firesign Theatre and screenwriter of such films as '' Zachariah''.

Early life

Ossman attended Pomona College, where he starr ...

, a member of the Firesign Theater troupe, the NPR production aired exactly 50 years after Welles' original radio presentation. It featured, in addition to Edwards, actor Jason Robards

Jason Nelson Robards Jr. (July 26, 1922 â December 26, 2000) was an American actor. Known as an interpreter of the works of playwright Eugene O'Neill, Robards received two Academy Awards, a Tony Award, a Primetime Emmy Award, and the Cannes ...

, comic writer and musician Steve Allen

Stephen Valentine Patrick William Allen (December 26, 1921 â October 30, 2000) was an American television personality, radio personality, musician, composer, actor, comedian, and writer. In 1954, he achieved national fame as the co-cre ...

, and various NPR announcers.

Personal life and death

Edwards married twice. On August 29, 1939, he wed Sara Belle Byrd, a native of North Carolina and a resident of Atlanta when Edwards resided in Georgia for several years. The couple divorced after 26 years together, during which time they had three children: Lynn Alice, Robert Anthony, and Donna Claire. Then, on May 10, 1966, Edwards married May Hamilton Dunlap inSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, California. He and May remained together until his death.

In 1990, at age 73, Edwards died of bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder. Symptoms include blood in the urine, pain with urination, and low back pain. It is caused when epithelial cells that line the bladder become ma ...

at his home in Sarasota, Florida. Following a memorial service at the Church of the Palms in Sarasota, Edwards's body was cremated.

Legacy and accolades

Many of Edwards' early CBS radio and televised newscasts are preserved, including his World War II anchoring of ''World News Today'', broadcasts onD-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

, and his coverage of the sinking of the ''Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Rep ...

'', all of which serve as important historical records of that period and of those events.

Edwards anchored the live five-minute segment ''The CBS Afternoon News'' five afternoons a week between 1962 and 1966. He began the segment immediately after the broadcast of the Goodson-Todman game show

A game show is a genre of broadcast viewing entertainment (radio, television, internet, stage or other) where contestants compete for a reward. These programs can either be participatory or demonstrative and are typically directed by a host, ...

'' To Tell the Truth''. Every moment of ''The CBS Afternoon News'' was lost due to wiping

Lost television broadcasts are mostly those early television programs which cannot be accounted for in studio archives (or in personal archives) usually because of deliberate destruction or neglect.

Common reasons for loss

A significant prop ...

.

For Edwardsâ decades of contributions to broadcast journalism, he received numerous awards and accolades from colleagues and professional organizations. The following are just some of those awards:

* 1952 Recipient of the Certificate of Merit from ''TV Guide

TV Guide is an American digital media company that provides television program listings information as well as entertainment and television-related news.

The company sold its print magazine division, TV Guide Magazine LLC, in 2008.

Corporat ...

'' for readers' poll as the East Coast's "favorite network newscaster"

* 1952 Recipient of the "Mike and Screen Press Award" from the Radio-Newsreel-Television Working Press Association for his coverage of the Missouri River floods

* 1955 Nominee for Emmy Award

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

as "Best News Reporter or News Commentator for the Year 1954"

* 1955 Top selection in ''TV Radio Mirror

Macfadden Communications Group is a publisher of business magazines. It has a historical link with a company started in 1898 by Bernarr Macfadden that was one of the largest magazine publishers of the twentieth century.

History

Macfadden Publ ...

'' readers' poll as "Favorite News Commentator"

* 1956 Recipient of the George Foster Peabody Award

The George Foster Peabody Awards (or simply Peabody Awards or the Peabodys) program, named for the American businessman and philanthropist George Peabody, honor the most powerful, enlightening, and invigorating stories in television, radio, and ...

for distinguished achievement in television journalism for "Outstanding News Program, 1955"

* 1956 Nominee for Emmy Award for "Best News Reporter or News Commentator for the Year 1955"

* 1956 Recipient of the Hamilton Time Award for his "objective and dramatic presentation of the news of the world"

* 1958 Top selection in ''TV Radio Mirror'' readers' poll as "Favorite News Commentator"

* 1960 ''Douglas Edwards with the News'' nominated for an Emmy Award for "Outstanding Program Achievement in the Field of News"

* 1961 Recipient of the Big Red Apple Award from San Jose State College for meritorious service in American journalism

* 1961 Recipient of a special service award from the Anti-Defamation League

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), formerly known as the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, is an international Jewish non-governmental organization based in the United States specializing in civil rights law. It was founded in late Septe ...

of B'nai B'rith

B'nai B'rith International (, from he, ×Ö°Ö¼× Öµ× ×ְּרִ×ת, translit=b'né brit, lit=Children of the Covenant) is a Jewish service organization. B'nai B'rith states that it is committed to the security and continuity of the Jewish peo ...

* 1961 ''Douglas Edwards with the News'' nominated for an Emmy Award for "Outstanding Program Achievement in the Field of News"

* 1975 Recipient of the first Freedom of Speech Award presented by the Georgia Association of Broadcasters

The Georgia Association of Broadcasters represents radio and television broadcasters across the U.S. state of Georgia. It is affiliated with the National Association of Broadcasters.

See also

* List of radio stations in Georgia (U.S. state)

* ...

* 1982 Recipient of the Broadcasting Service Award from the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

* 1982 Recipient of the Gold Mike Award for broadcast achievement at the CBS Radio Network Affiliates Convention

* 1986 Recipient of the Lowell Thomas Award from Marist College

Marist College is a private university in Poughkeepsie, New York. Founded in 1905, Marist was formed by the Marist Brothers, a Catholic religious institute, to prepare brothers for their vocations as educators. In 2003, it became a secular in ...

for outstanding broadcast journalism

* 1986 Inductee to the National Broadcasters Hall of Fame

* 1987 Recipient of the National Association of Broadcasters Radio Award

* 1988 Recipient of the Paul White Award from the Radio Television Digital News Association

The Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA, pronounced the same as " rotunda"), formerly the Radio-Television News Directors Association (RTNDA), is a United States-based membership organization of radio, television, and online news dire ...

* 2006 Inductee to the National Radio Hall of Fame

The Radio Hall of Fame, formerly the National Radio Hall of Fame, is an American organization created by the Emerson Radio Corporation in 1988.

Three years later, Bruce DuMont, founder, president, and CEO of the Museum of Broadcast Communicati ...

References

External links

MetaCafe: "Flight of Sputnik I,"

CBS News (Douglas Edwards reporting), 2 October 1957 *

Edward's farewell World Tonight radio broadcast on April 1, 1988

NPR's 1988 ''War of the Worlds'' broadcast

with Edwards coming in at about 26:03. *

{{DEFAULTSORT:Edwards, Douglas 1917 births 1990 deaths CBS News people American television news anchors American television reporters and correspondents Peabody Award winners Deaths from cancer in Florida People from Ada, Oklahoma