Dialogorum de Trinitate libri duo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Michael Servetus (; es, Miguel Serveto as real name; french: Michel Servet; also known as ''Miguel Servet'', ''Miguel de Villanueva'', ''Revés'', or ''Michel de Villeneuve''; 29 September 1509 or 1511 – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish

For a long time, it was held that Servetus was probably born in 1511 in Villanueva de Sigena in the Kingdom of Aragon, present-day Spain. The day of 29 September has been conventionally proposed for his birth, due to the fact that 29 September is Saint Michael's day according to the Catholic

For a long time, it was held that Servetus was probably born in 1511 in Villanueva de Sigena in the Kingdom of Aragon, present-day Spain. The day of 29 September has been conventionally proposed for his birth, due to the fact that 29 September is Saint Michael's day according to the Catholic

''An Examination of the Nature of Authority''

Chapter 3. Servetus sent Calvin several more letters, to which Calvin took offense. Thus, Calvin's frustrations with Servetus seem to have been based mainly on Servetus's criticisms of Calvinist doctrine, but also on his tone, which Calvin considered inappropriate. Calvin revealed these frustrations with Servetus when writing to his friend William Farel on 13 February 1546: ).

/ref>) Nevertheless, Calvin is regarded as the author of the prosecution. At his trial, Servetus was condemned on two counts for spreading and preaching Nontrinitarianism, specifically, Modalistic Monarchianism (or Sabellianism) and anti-paedobaptism (anti-infant baptism).''Hunted Heretic'', p. 141. Of paedobaptism Servetus had said, "It is an invention of the devil, an infernal falsity for the destruction of all Christianity." In the case, the ''procureur général'' (chief public prosecutor) added some curious-sounding accusations in the form of inquiries – the most odd-sounding perhaps being, "whether he has married, and if he answers that he has not, he shall be asked why, in consideration of his age, he could refrain so long from marriage." To this oblique imputation about his sexuality, Servetus replied that rupture (inguinal hernia) had long since made him incapable of that particular sin. Another question was "whether he did not know that his doctrine was pernicious, considering that he favours Jews and Muslims, Turks, by making excuses for them, and if he has not studied the Quran, Koran in order to disprove and controvert the doctrine and religion that the Christian churches hold, together with other profane books, from which people ought to abstain in matters of religion, according to the doctrine of Paul of Tarsus, St. Paul." Calvin believed Servetus deserved death because of what Calvin termed, "execrable blasphemies". Calvin expressed these sentiments in a letter to William Farel, Farel, written about a week after Servetus' arrest, in which he also mentioned an exchange with Servetus. Calvin wrote:

Aspects of his thinking—his critique of existing trinitarian theology, his devaluation of the doctrine of original sin, and his fresh examination of biblical proof-texts—did influence those who later inspired or founded unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania. Other non-trinitarian groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, and Oneness Pentecostalism, also claim Servetus held similar non-trinitarian views as theirs. Oneness Pentecostalism particularly identifies with Servetus' teaching on the divinity of Jesus Christ and his insistence on the oneness of God, rather than a Trinity of three distinct persons: "And because His Spirit was wholly God He is called God, just as from His flesh He is called man." Oneness Pentecostal Scholar David K. Bernard has written the following in regard to the theology of Michael Servetus: "... some historians consider him to be a motivating force for the development of Unitarianism. However, he definitely was not Unitarian, for he acknowledged Jesus as God." Swedenborg wrote a systematic theology that had many similarities to the theology of Servetus.

PDF; 64,1 MiB

) *M. Hillar: "Poland's Contribution to the Reformation: Socinians/Polish Brethren and Their Ideas on the Religious Freedom," The Polish Review, Vol. XXXVIII, No.4, pp. 447–468, 1993. *M. Hillar, "From the Polish Socinians to the American Constitution," in A Journal from the Radical Reformation. A Testimony to Biblical Unitarianism, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 22–57, 1994. *José Luis Corral: ''El médico hereje'', Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, S.A., 2013 . A novel (in Spanish) narrating the publication of ''Christianismi Restitutio'', Servetus' trial by the Inquisition of Vienne, his escape to Geneva, and his disputes with John Calvin and subsequent burning at the stake by the Calvinists.

In Geneva, 350 years after the execution, remembering Servetus was still a controversial issue. In 1903 a committee was formed by supporters of Servetus to erect a monument in his honour. The group was led by a French Senator, , an author of a book on heretics and revolutionaries which was published in 1887. The committee commissioned a local sculptor, Clotilde Roch, to execute a statue showing a suffering Servetus. The work was three years in the making and was finished in 1907. However, by then, supporters of Calvin in Geneva, having heard about the project, had already erected a simple stele in memory of Servetus in 1903, the main text of which served more as an apologetic for Calvin:

In Geneva, 350 years after the execution, remembering Servetus was still a controversial issue. In 1903 a committee was formed by supporters of Servetus to erect a monument in his honour. The group was led by a French Senator, , an author of a book on heretics and revolutionaries which was published in 1887. The committee commissioned a local sculptor, Clotilde Roch, to execute a statue showing a suffering Servetus. The work was three years in the making and was finished in 1907. However, by then, supporters of Calvin in Geneva, having heard about the project, had already erected a simple stele in memory of Servetus in 1903, the main text of which served more as an apologetic for Calvin:

The two treatises of Servetus on the Trinity

', New York, Kraus Reprint Co., pp. vii–xviii *1532 ''Dialogues on the Trinity. Dialogorum de Trinitate.'' Haguenau, printed by Hans Setzer. Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city where it was printed. Signed as Michael Serveto alias Revés, from Aragon, Spanish. *1535 ''Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Claudii Ptolemaeii Alexandrinii Geographicae''. Lyon, Trechsel. Signed as Michel de Villeneuve. Servetus dedicated this work to Hugues de la Porte. The second edition was dedicated to Pierre Palmier. Michel de Villeneuve states that the basis of his edition comes from the work of Bilibald Pirkheimer, who translated this work from Greek to Latin, but Michel also affirms that he also compared it to the primitive Greek texts. The 19th-century expert in Servetus, Henri Tollin (1833–1902), considered him to be "the father of comparative geography" due to the extension of his notes and commentaries. *1536 ''The Apology against Leonard Fuchs. In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia.'' Lyon, printed by Gilles Hugetan, with Parisian prologue. Signed as Michel de Villeneuve. The physician Leonhart Fuchs and a friend of Michael Servetus, Symphorien Champier, got involved in an argument ''via'' written works, on their different Lutheran and Catholic beliefs. Servetus defends his friend in the first parts of the work. In the second part he talks of a medical plant and its properties. In the last part he writes on different topics, such as the defense of a pupil attacked by a teacher, and the origin of syphilis. *1537 ''Complete Explanation of the Syrups. Syruporum universia ratio''. Paris, printed by Simon de Colines. Signed as Michael de Villeneuve. This work consists of a prologue "The Use of Syrups", and 5 chapters: I "What the concoction is and why it is unique and not multiple", II "What the things that must be known are", III "That the concoction is always..", IV "Exposition of the aphorisms of Hippocrates" and V "On the composition of syrups". Michel de Villeneuve refers to experiences of using the treatments, and to pharmaceutical treatises and terms more deeply described in his later pharmacopeia ''Enquiridion'' or ''Dispensarium''. Michel mentions two of his teachers, Sylvius and Andernach, but above all, Galen. This work had a strong impact in those times. *1538 ''Apologetic discourse of Michel de Villeneuve in favour of Astrology and against a certain physician. Michaelis Villanovani in quedam medicum apologetica disceptatio pro Astrologia.'' Paris, unknown printer. Servetus denounces Jean Tagault, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris, for attacking astrology, while many great thinkers and physicians praised it. He lists reasonings of Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen, how the stars are related to some aspects of a patient's health, and how a good physician can predict effects by them: the effect of the moon and sun on the sea, the winds and rains, the period of women, the speed of the decomposition of the corpses of beasts, etc. *1542 ''Holy Bible according to the translation of Santes Pagnino. Biblia sacra ex Santes Pagnini tralation, hebraist.'' Lyon, edited by Delaporte and printed by Trechsel. The name Michel de Villeneuve appears in the prologue, the last time this name would appear in any of his works. *1542 ''Biblia sacra ex postremis doctorum'' (octavo). Vienne in Dauphiné, edited by Delaporte and printed by Trechsel. Anonymous. *1545 ''Holy Bible with commentaries. Biblia Sacra cum Glossis.'' Lyon, printed by Trechsel and Vincent. Called "Ghost Bible" by scholars who denied its existence. There is an anonymous work from this year that was edited in accordance with the contract that Miguel de Villeneuve made with the Company of Booksellers in 1540. The work consists of 7 volumes (6 volumes and an index) illustrated by Hans Holbein the Younger, Hans Holbein. This research was carried out by the scholar Julien Baudrier in the sixties. Recently scholar González Echeverría has graphically proved the existence of this work, and demonstrating that contrary to what experts Barón and Hillard thought, this work is also anonymous. *"Manuscript of Paris" (c. 1546). This document is a draft of the ''Christianismi Restitutio''. Written in Latin, it includes a few quotes in Greek and Hebrew. This work has paleographically the same handwriting as the "Manuscript of the Complutense". *1553 ''The Restoration of Christianity. Cristianismi Restitutio''. Vienne, Isère, Vienne, printed by Baltasar Arnoullet. Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city in which it was printed. Signed as M.S.V. at the colophon though "Servetus" name is mentioned inside, in a fictional dialog. Servetus uses Biblical quotes in Greek and in Hebrew on its cover and in the body of the text whenever he wanted to stress the original meaning of a word from Scripture.

''Miguel Servet y los impresores lioneses del siglo XVI''

pp. 116–118, 373.

Blackstone Editions

. a standard scholarly biography focused on religion. * González Echeverría, Francisco Javier (2017)

''Miguel Servet y los impresores lioneses del siglo XVI''

PhD dissertation on Modern History, Spanish National Distance University (UNED). Dissertation director: Carlos Martínez Shaw, Modern History prof. at UNED & Numerary member at the Spanish Real Academia de la Historia, Royal Academy of History, chair #32. Qualification: unanimous Cum Laude. Madrid: Spanish National Distance University (UNED) * González Ancín, Miguel & Towns, Otis. (2017)

Miguel Servet en España (1506–1527). Edición ampliada

' . 474pp. A work focused on Servetus's past in Spain, with his documents as a student and professor of arts in Saragossa. * Goldstone, Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone. ''Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World'' . 353pp * * Hughes, Peter. "Michael Servetus's Britain: Anatomy of a Renaissance Geographer's Writing." ''Renaissance & Reformation/Renaissance et Reforme'' (2016_ 39#2 pp 85–109. * Hughes, Peter. "The Face of God: The Christology of Michael Servetus." ''Journal of Unitarian Universalist History'' 2016/2017, Vol. 40, pp 16–53 * Hughes, Peter. "The Early Years of Servetus and the Origin of His Critique of Trinitarian Thought" ''Journal of Unitarian Universalist History'' (2013/2014), Vol. 37, pp 32–99. * Lovci, Radovan

''Michael Servetus, Heretic or Saint?''

Prague: Prague House, 2008. . * McNeill, John T. ''The History and Character of Calvinism'', New York: Oxford University Press, 1954. . * Nigg, Walter.''The Heretics: Heresy Through the Ages'' Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1962. (Republished b

Dorset Press, 1990

) * Pettegree, Andrew. "Michael Servetus and the limits of tolerance." ''History Today'' (Feb 1990) 40#2 pp 40–45; popular history by a scholar

''Claudii Ptolemaeii Alexandrinii Geographicae'' (1535, Lyon, Trechsel)

* Michael Servetus

''In Leonardum Fuchsium apologia'' (1536, Lyon, Hugetan)

* Michael Servetus

''Syruporum universa ratio'' (1537, Paris, Simon de Colines)

* Michael Servetus, ''Apologetica disceptatio pro astrologia'' (1538, Paris). It is completely reproduced on servetian Verdu Vicente's dissertation on such work, pp. 113–129. (Verdu Vicente

''Astrologia y hermetismo en Miguel Servet''

Directors: Mínguez Pérez, Carlos; Estal, Juan Manuel. Universitat de València, 1998). * Jean Calvin

''Defensio orthodoxae fidei de sacra Trinitate contra prodigiosos errores Michaelis Serveti...''

(Defense of Orthodox Faith against the Prodigious Errors of the Spaniard Michael Servetus...), Geneva, 1554. Calvin's ''Opere'' in the Corpus Reformatorum, vol. viii, 453–644

Ursus Books and Prints Catalogue of Scarce Books, Americana, Etc. Bangs & Co, p. 41

''Letters of John Calvin''

Carlisle, Penn

The Banner of Truth Trust

1980. .

with WorldCat. Contains seventy letters of Calvin, several of which discuss his plans for, and dealings with, Servetus. Also includes his final discourses and his last will and testament (25 April 1564). * Jules Bonnet,

Letters of John Calvin

', 2 vols., 1855, 1857, Edinburgh, Thomas Constable and Co.: Little, Brown, and Co., Boston – The Internet Archive

''The Man from Mars: His Morals, Politics and Religion''"> ''The Man from Mars: His Morals, Politics and Religion''

by William Simpson, San Francisco: E.D. Beattle, 1900. Excerpts from letters of Servetus, written from his prison cell in Geneva (1553), pp. 30–31. Google Books. * The translation of ''Christianismi Restitutio'' into English (the first ever) by Christopher Hoffman and Marian Hillar was published so far in four parts. One part still remains to be published: * ["The Restoration of Christianity. An English Translation of Christianismi restitutio, 1553, by Michael Servetus (1511–1553). Translated by Christopher A. Hoffman and Marian Hillar," (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2007). Pp. 409+xxix *"Treatise on Faith and Justice of Christ’s Kingdom" by Michael Servetus. Selected and Translated from "Christianismi restitutio" by Christopher A. Hoffman and Marian Hillar (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2008). pp. 95 +xlv *"Treatise Concerning the Supernatural Regeneration and the Kingdom of the Antichrist by Michael Servetus. Selected and Translated from Christianismi restitutio by Christopher A. Hoffman and Marian Hillar," (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2008). pp. 302+l *"Thirty Letters to Calvin & Sixty Signs of the Antichrist by Michael Servetus." Translated from Christianismi restitutio by Christopher A. Hoffman and Marian Hillar (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010). pp. 175 + lxxxvi

Michael Servetus Institute

– Museum and centre for Servetian studies in Villanueva de Sigena, Spain

Michael Servetus Center

– Research portal on Michael Servetus run by servetians González Ancín & Towns, also including multiple works and studies by servetian González Echeverría.

Center for Philosophy and Socinian Studies

*

Works

a

Open Library

''Christianismi Restitutio'' – Full text

digitalized by the Spanish National Library.

''De Trinitatis Erroribus'' – Full text

digitalized by the Spanish National Library.

Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza (Spain)

from the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography

Michael Servetus – A Solitary Quest for the Truth

PDF; 64,1 MiB on Michael Servetus in Basel & Alfonsus Lyncurius and Pseudo-Servetus

Comments and quotes.

Reformed Apologetic for Calvin's actions against Servetus

Phillip Schaff, ''History of the Christian Church'', Vol. 8, chapter 16.

Thomas Jefferson: letter to William Short, 13 April 1820

– mention of Calvin and Servetus. {{DEFAULTSORT:Servetus, Michael 1511 births 1553 deaths 16th-century apocalypticists 16th-century Christian martyrs 16th-century Spanish jurists 16th-century Latin-language writers 16th-century Spanish physicians 16th-century Spanish theologians Antitrinitarians Christologists Executed people from the Republic of Geneva Executed scientists Executed Spanish people Founders of religions People executed by burning People executed for heresy People from Monegros Spanish medical writers Spanish Unitarians University of Paris alumni Victims of the Inquisition

theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

, cartographer, and Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

. He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

, as discussed in ''Christianismi Restitutio

''Christianismi Restitutio'' (English: The Restoration of Christianity) was a book published in 1553 by Michael Servetus. It rejected the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and the concept of predestination, which had both been considered fundament ...

'' (1553). He was a polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

versed in many sciences: mathematics, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

and meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

, human anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

and pharmacology, as well as jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, translation

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

, poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

, and the scholarly study of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

in its original languages.

He is renowned in the history of several of these fields, particularly medicine. He participated in the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, and later rejected the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

doctrine and mainstream Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

. After being condemned by Catholic authorities in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, he fled to Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

where he was denounced by John Calvin himself and burned at the stake for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

by order of the city's governing council.

Life

Early life and education

For a long time, it was held that Servetus was probably born in 1511 in Villanueva de Sigena in the Kingdom of Aragon, present-day Spain. The day of 29 September has been conventionally proposed for his birth, due to the fact that 29 September is Saint Michael's day according to the Catholic

For a long time, it was held that Servetus was probably born in 1511 in Villanueva de Sigena in the Kingdom of Aragon, present-day Spain. The day of 29 September has been conventionally proposed for his birth, due to the fact that 29 September is Saint Michael's day according to the Catholic calendar of saints

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context d ...

, but there is no evidence supporting this date. Some sources give an earlier date based on Servetus' own occasional claim of having been born in 1509. However, in 2002 a paper published by Francisco Javier González Echeverría and María Teresa Ancín suggested that he was born in Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre. It has also been held that his true name was ''De Villanueva'' according to the letters of his French naturalization (Chamber des Comptes, Royal Chancellorship and Parlement of Grenoble) and the registry at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

.

The ancestors of his father came from the hamlet of Serveto, in the Aragonese Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

. His father was a notary of Christian ancestors from the lower nobility (''infanzón''), who worked at the nearby Monastery of Santa Maria de Sigena. It was long believed that Servetus had just two brothers: Juan, who was a Catholic parish priest, and Pedro, who was a notary. But, it has been recently documented that Servetus actually had two more brothers (Antón and Francisco) and at least three sisters (Catalina, Jeronima, and Juana). Although Servetus declared during his trial in Geneva that his parents were "Christians of ancient race", and that he never had any communication with Jews, his maternal line actually descended from the Zaportas (or Çaportas), a wealthy and socially relevant family from the Barbastro

Barbastro (Latin: ''Barbastrum'' or ''Civitas Barbastrensis'', Aragonese: ''Balbastro'') is a city in the Somontano county, province of Huesca, Spain. The city (also known originally as Barbastra or Bergiduna) is at the junction of the rivers Cin ...

and Monzón

Monzón is a small city and municipality in the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. Its population was 17,176 as of 2014. It is in the northeast (specifically the Cinca Medio district of the province of Huesca) and adjoins the rivers Cinca an ...

areas in Aragon. This was demonstrated by a notarial protocol published in 1999.

Servetus' family used a nickname, "Revés", according to an old tradition in rural Spain of using alternate names for families across generations. The origin of the Revés nickname may have been that a member of a (probably distinguished) family living in Villanueva with the surname Revés established blood ties with the Servet family, thus uniting both family names for the next generations.

Education

Servetus attended theGrammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domain ...

Studium in Sariñena

Sariñena is a municipality in the province of Huesca, Aragon, Spain. It is located in the Monegros comarca, near the Sierra de Alcubierre range.

The Baroque monastery of Nuestra Señora de las Fuentes is located in the municipal term.

Village ...

, Aragón, near Villanueva de Sijena, under master Domingo Manobel until 1520. From course 1520/1521 to 1522/1523, Michael Servetus was a student of the Liberal Arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term '' art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically th ...

in the primitive University of Zaragoza, a Studium Generale

is the old customary name for a medieval university in medieval Europe.

Overview

There is no official definition for the term . The term ' first appeared at the beginning of the 13th century out of customary usage, and meant a place where stud ...

of Arts. The Studium was ruled by the Archbishop of Saragossa, the Rector, the High Master ("Maestro Mayor"), and four "Masters of Arts", which resembled Art professors in the Arts Faculties of other primitive universities. Servetus studied under High Master Gaspar Lax Gaspar Lax (1487 – 23 February 1560) was a Spanish mathematician, logician, and philosopher who spent much of his career in Paris.

Biography

Lax was born in Sariñena, the son of Leonor de la Cueva and Gaspar Lax, a physician, and had two broth ...

, and masters Exerich, Ansias, and Miranda. During those years this education center had been significantly influenced by Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

's ideas. Ansias and Miranda died soon, and two new professors were appointed: Juan Lorenzo Carnicer and Villalpando. In 1523 he got his BA and next year his MA. From course 1525/1526 ahead, Servetus became one of the four Masters of Arts in the Studium, and for unknown reasons, he traveled to Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

in February 1527. But on 28 March 1527, also for unknown reasons, master Michael Servetus had a brawl with High Master (and uncle) Gaspard Lax, and this probably was the cause of his expulsion from the Studium, and his exile from Spain for the Studium of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Pa ...

, trying to avoid the strong influence of Gaspar Lax in any Spanish Studium Generale.

Near 1527 Servetus attended the University of Toulouse

The University of Toulouse (french: Université de Toulouse) was a university in the French city of Toulouse that was established by papal bull in 1229, making it one of the earliest universities to emerge in Europe. Suppressed during the Frenc ...

where he studied law. Servetus could have had access to forbidden religious books, some of them maybe Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, while he was studying in this city.

Career

In 1530 Servetus joined the retinue of EmperorCharles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

as page or secretary to the emperor's confessor, Juan de Quintana. Servetus travelled through Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and attended Charles' coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

. He was outraged by the pomp and luxury displayed by the Pope and his retinue, and so decided to follow the path of reformation.Bainton, ''Hunted Heretic'', pp. 10–11. It is not known when Servetus left the imperial entourage, but in October 1530 he visited Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius (also ''Œcolampadius'', in German also Oekolampadius, Oekolampad; 1482 – 24 November 1531) was a German Protestant reformer in the Calvinist tradition from the Electoral Palatinate. He was the leader of the Protestant ...

in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, staying there for about ten months, probably supporting himself as a proofreader for a local printer. By this time, he was already spreading his theological beliefs. In May 1531 he met Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Fabricius Capito in Strasbourg.

Two months later, in July 1531, Servetus published ''De Trinitatis Erroribus'' (''On the Errors of the Trinity''). The next year he published the work ''Dialogorum de Trinitate'' (''Dialogues on the Trinity'') and the supplementary work ''De Iustitia Regni Christi'' (''On the Justice of Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

's Reign'') in the same volume. After the persecution of the Inquisition, Servetus assumed the name "Michel de Villeneuve" while he was staying in France. He studied at the Collège de Calvi in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

in 1533.

Servetus also published the first French edition of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

's ''Geography''. He dedicated his first edition of Ptolemy and his edition of the Bible to his patron Hugues de la Porte. While in Lyon, Symphorien Champier, a medical humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, had been his patron. Servetus wrote a pharmacological

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

treatise in defence of Champier against Leonhart Fuchs ''In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia'' (''Apology against Leonard Fuchs''). Working also as a proofreader, he published several more books, which dealt with medicine and pharmacology (such as his ''Syruporum universia ratio'' (''Complete Explanation of the Syrups'')), for which he gained fame.

After an interval, Servetus returned to Paris to study medicine in 1536. In Paris, his teachers included Jacobus Sylvius, Jean Fernel

Jean François Fernel ( Latinized as Ioannes Fernelius; 1497 – 26 April 1558) was a French physician who introduced the term "physiology" to describe the study of the body's function. He was the first person to describe the spinal canal. The l ...

, and Johann Winter von Andernach, who hailed him with Andrea Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

as his most able assistant in dissections. During these years, he wrote his ''Manuscript of the Complutense'', an unpublished compendium of his medical ideas. Servetus taught mathematics and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

while he studied medicine. He predicted an occultation of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

by the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

, which along with his teaching, generated much envy among the medicine teachers. His teaching classes were suspended by the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Jean Tagault, and Servetus wrote his ''Apologetic Discourse of Michel de Villeneuve in Favour of Astrology and against a Certain Physician'' against him. Tagault later argued for the death penalty in the judgment of the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

against Servetus, who was accused of teaching '' De Divinatione'' by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

. Finally, the sentence was reduced to the withdrawal of this edition. As a result of the risks and difficulties of studying medicine at Paris, Servetus decided to go to Montpellier to finish his medical studies, maybe thanks to his teacher Sylvius who did exactly the same as a student. There Servetus became a Doctor of Medicine in 1539. After that he lived at Charlieu

Charlieu (; frp, Charluè) is a Communes of France, commune in the Loire (department), Loire Departments of France, department at the northern end of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of France. It is home to Charlieu Abbey.

Population

Twin tow ...

. A jealous physician ambushed and tried to kill Servetus, but Servetus defended himself and injured one of the attackers in a sword fight. He was in prison for several days because of this incident.

Working at Vienne

After his studies in medicine, Servetus started a medical practice. He became the personal physician to Pierre Palmier,Archbishop of Vienne

The Archbishopric of Vienne, named after its episcopal seat in Vienne in the Isère département of southern France, was a metropolitan Roman Catholic archdiocese. It is now part of the Archdiocese of Lyon.

History

The legend according to whi ...

and was the physician to Guy de Maugiron, the lieutenant governor of Dauphiné

The Dauphiné (, ) is a former province in Southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was originally the Dauphiné of Viennois.

In the 12th centu ...

. Thanks to the printer Jean Frellon II, acquaintance of John Calvin and friend of Michel, Servetus and Calvin Calvin may refer to:

Names

* Calvin (given name)

** Particularly Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States

* Calvin (surname)

** Particularly John Calvin, theologian

Places

In the United States

* Calvin, Arkansas, a hamlet

* Calvi ...

began to correspond. Calvin used the pseudonym "''Charles d'Espeville''". Servetus also became a French citizen, using his "De Villeneuve" ''persona'', by the Royal Process (1548–1549) of French Naturalization, issued by Henri II of France

Henry II (french: Henri II; 31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559) was King of France from 31 March 1547 until his death in 1559. The second son of Francis I and Duchess Claude of Brittany, he became Dauphin of France upon the death of his elder broth ...

.

In 1553 Michael Servetus published another religious work with further anti-trinitarian views entitled ''Christianismi Restitutio

''Christianismi Restitutio'' (English: The Restoration of Christianity) was a book published in 1553 by Michael Servetus. It rejected the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and the concept of predestination, which had both been considered fundament ...

'' (''The Restoration of Christianity''), a work that sharply rejected the idea of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

as the idea that God condemned souls to Hell regardless of worth or merit. God, insisted Servetus, condemns no one who does not condemn himself through thought, word, or deed. This work also includes the first published description of the pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

in Europe, though it's thought to be Ibn al-Nafis#Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon, based on work by 13th century Syrian polymath ibn al-Nafis.

Servetus had sent an early version of his book to Calvin. To Calvin, who had published his summary of Christian doctrine ''Institutio Christianae Religionis'' (''Institutes of the Christian Religion'') in 1536, Servetus' latest book was an attack on historical Nicene Creed, Nicene Christian doctrine and a misinterpretation of the biblical canon. Calvin sent a copy of his own book as his reply. Servetus promptly returned it, thoroughly annotated with critical observations. Calvin wrote to Servetus, "I neither hate you nor despise you; nor do I wish to persecute you; but I would be as hard as iron when I behold you insulting sound doctrine with so great audacity". In time, their correspondence grew more heated until Calvin ended it.Downton''An Examination of the Nature of Authority''

Chapter 3. Servetus sent Calvin several more letters, to which Calvin took offense. Thus, Calvin's frustrations with Servetus seem to have been based mainly on Servetus's criticisms of Calvinist doctrine, but also on his tone, which Calvin considered inappropriate. Calvin revealed these frustrations with Servetus when writing to his friend William Farel on 13 February 1546: ).

Imprisonment and execution

On 16 February 1553, Michael Servetus while in Vienne, Isère, Vienne, France, was denounced as a heretic by Guillaume de Trie (a rich merchant who had taken refuge in Republic of Geneva, Geneva and who was a good friend of Calvin) in a letter sent to a cousin, Antoine Arneys, who was living in Lyon. On behalf of the French inquisitor Matthieu Ory, Michael Servetus and Balthasard Arnollet, the printer of ''Christianismi Restitutio

''Christianismi Restitutio'' (English: The Restoration of Christianity) was a book published in 1553 by Michael Servetus. It rejected the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and the concept of predestination, which had both been considered fundament ...

'', were questioned, but they denied all charges and were released for lack of evidence. Ory asked Arneys to write back to De Trie demanding proof. On 26 March 1553, the letters sent by Michael to Calvin and some manuscript pages of ''Christianismi Restitutio'' were forwarded to Lyon by De Trie. On 4 April 1553, Servetus was arrested by Roman Catholic authorities and imprisoned in Vienne. He escaped from prison three days later. On 17 June, he was convicted of heresy, "thanks to the 17 letters sent by John Calvin, preacher in Geneva"''Hunted Heretic'', p. 164. and sentenced to be burned with his books. In his absence, he and his books were burned in effigy (blank paper for the books).

Meaning to flee to Italy, Servetus inexplicably stopped in Geneva, where Calvin and his Reformers had denounced him. On 13 August, he attended a sermon by Calvin at Geneva. He was arrested after the service''The Heretics'', p. 326. and again imprisoned, and all his property was confiscated. Servetus claimed during this judgment he was arrested at an inn at Geneva. French Inquisitors asked that Servetus be extradited to them for execution. Calvin wanted to show he was as firm in defense of Christian orthodoxy as his usual opponents. "He was forced to push the condemnation of Servetus with all the means at his command." Calvin's health was one possible reason he did not personally appear against Servetus. Among the possible reasons that prevented Calvin from appearing personally against Servetus there was one that must have been sufficient. The laws regulating criminal actions in Geneva required that in certain grave cases the complainant himself should be incarcerated pending the trial. Calvin's health and his great and constant usefulness in the administration of the state rendered a prolonged absence from the public life of Geneva impracticable. Therefore, Nicholas de la Fontaine had the more active role in Servetus's prosecution and the listing of points that condemned him. (Nicholas de la Fontaine was a refugee in Geneva and entered the service of Calvin, by whom he was employed as secretary.Whitcomb, Merrick. "The Complaint of Nicholas de la Fontaine Against Servetus, 14 August, 1553", ''Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History'', vol. 3 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania History Department, 1898–1912)/ref>) Nevertheless, Calvin is regarded as the author of the prosecution. At his trial, Servetus was condemned on two counts for spreading and preaching Nontrinitarianism, specifically, Modalistic Monarchianism (or Sabellianism) and anti-paedobaptism (anti-infant baptism).''Hunted Heretic'', p. 141. Of paedobaptism Servetus had said, "It is an invention of the devil, an infernal falsity for the destruction of all Christianity." In the case, the ''procureur général'' (chief public prosecutor) added some curious-sounding accusations in the form of inquiries – the most odd-sounding perhaps being, "whether he has married, and if he answers that he has not, he shall be asked why, in consideration of his age, he could refrain so long from marriage." To this oblique imputation about his sexuality, Servetus replied that rupture (inguinal hernia) had long since made him incapable of that particular sin. Another question was "whether he did not know that his doctrine was pernicious, considering that he favours Jews and Muslims, Turks, by making excuses for them, and if he has not studied the Quran, Koran in order to disprove and controvert the doctrine and religion that the Christian churches hold, together with other profane books, from which people ought to abstain in matters of religion, according to the doctrine of Paul of Tarsus, St. Paul." Calvin believed Servetus deserved death because of what Calvin termed, "execrable blasphemies". Calvin expressed these sentiments in a letter to William Farel, Farel, written about a week after Servetus' arrest, in which he also mentioned an exchange with Servetus. Calvin wrote:

...after he [Servetus] had been recognized, I thought he should be detained. My friend Nicholas de la Fontaine, Nicolas summoned him on a capital charge, offering himself as a security according to the ''lex talionis''. On the following day he adduced against him forty written charges. He at first sought to evade them. Accordingly we were summoned. He impudently reviled me, just as if he regarded me as obnoxious to him. I answered him as he deserved... of the man’s effrontery I will say nothing; but such was his madness that he did not hesitate to say that devils possessed divinity; yea, that many gods were in individual devils, inasmuch as a deity had been substantially communicated to those equally with wood and stone. I hope that sentence of death will at least be passed on him; but I desired that the severity of the punishment be mitigated.Calvin to William Farel, 20 August 1553As Servetus was not a citizen of Geneva, and legally could at worst be banished, the government in an attempt to find some plausible excuse to disregard this legal reality had consulted Cantons of Switzerland, Swiss Reformed cantons (Zürich, Bern,

Bonnet, Jules (1820–1892)

''Letters of John Calvin'', Carlisle, Penn: Banner of Truth Trust, 1980, pp. 158–159. .

Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, Schaffhausen). They universally favoured his condemnation and suppression of his doctrine, but without saying how that should be accomplished. Martin Luther had condemned his writing in strong terms. Servetus and Philip Melanchthon had strongly hostile views of each other. The party called the "Libertines", who were generally opposed to anything and everything John Calvin supported, were in this case strongly in favour of the execution of Servetus at the stake (while Calvin urged that he be beheaded instead). In fact, the council that condemned Servetus was presided over by Ami Perrin (a Libertine) who ultimately on 24 October sentenced Servetus to execution by burning, death by burning for denying the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

and paedobaptism, infant baptism. Calvin and other ministers asked that he be beheaded instead of burnt, knowing that burning at the stake was the only legal recourse. This plea was refused, and on 27 October, Servetus was burnt alive atop a pyre of his own books at the Plateau of Champel at the edge of Geneva. Historians record his last words as: "Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have mercy on me."

Legacy

Sebastian Castellio and countless others denounced this execution and became harsh critics of Calvin because of the whole affair. Some other anti-trinitarian thinkers began to be more cautious in expressing their views: Martin Cellarius, Lelio Sozzini and others either ceased writing or wrote only in private. The fact that Servetus was dead meant that his writings could be distributed more widely, though others such as Giorgio Biandrata developed them in their own names. The writings of Servetus influenced the beginnings of the Unitarian movement in Poland and Transylvania.See Stanislas Kot, "L'influence de Servet sur le mouvement atitrinitarien en Pologne et en Transylvanie", in B. Becker (Ed.), ''Autour de Michel Servet et de Sebastien Castellion'', Haarlem, 1953. Peter Gonesius's advocacy of Servetus' views led to the separation of the Polish brethren from the Calvinist Reformed Church in Poland, and laid the foundations for the Socinian movement which fostered the early Unitarianism, Unitarians in England like John Biddle (Unitarian), John Biddle.Theology

In his first two books (''De trinitatis erroribus'', and ''Dialogues on the Trinity'' plus the supplementary ''De Iustitia Regni Christi'') Servetus rejected the classical conception of theTrinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, stating that it was not based on the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

. He argued that it arose from teachings of Greek Western philosophy, philosophers, and he advocated a return to the simplicity of the Gospels and the teachings of the early Church Fathers that he believed predated the development of First Council of Nicaea, Nicene trinitarianism. Servetus hoped that the dismissal of the trinitarian dogma would make Christianity more appealing to believers in Judaism and Islam, which had preserved the unity of God in their teachings. According to Servetus, trinitarians had turned Christianity into a form of "tritheism", or belief in three gods. Servetus affirmed that the divine ''Logos'', the manifestation of God and not a separate divine Person, was incarnated in a human being, Jesus, when God's spirit came into the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Virgin Mary. Only from the moment of conception was the Son actually generated. Therefore, although the Logos from which He was formed was eternal, the Son was not Himself eternal. For this reason, Servetus always rejected calling Christ the "eternity, eternal Son of God" but rather called him "the Son of the eternal God."

In describing Servetus' view of the Logos, Andrew Dibb explained: "In 'Genesis' God reveals himself as the creator. In 'John' he reveals that he created by means of the Word, or Logos. Finally, also in 'John', he shows that this Logos became flesh and 'dwelt among us'. Creation took place by the spoken word, for God said "Let there be ..." The spoken word of Genesis, the Logos of John, and the Christ, are all one and the same."

In his "Treatise Concerning the Divine Trinity" Servetus taught that the Logos was the reflection of Christ, and "That reflection of Christ was 'the Word with God" that consisted of God Himself, shining brightly in heaven, "and it was God Himself" and that "the Word was the very essence of God or the manifestation of God's essence, and there was in God no other substance or hypostasis than His Word, in a bright cloud where God then seemed to subsist. And in that very spot the face and personality of Christ shone bright."

Unitarian scholar Earl Morse Wilbur states, "Servetus' ''Errors of the Trinity'' is hardly heretical in intent, rather is suffused with passionate earnestness, warm piety, an ardent reverence for Scripture, and a love for Christ so mystical and overpowering that [he] can hardly find words to express it ... Servetus asserted that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit were dispositions of God, and not separate and distinct beings." Wilbur promotes the idea that Servetus was a Modalism, modalist.

Servetus states his view clearly in the preamble to ''Restoration of Christianity'' (1553): "There is nothing greater, reader, than to recognize that God has been manifested as substance, and that His divine nature has been truly communicated. We shall clearly apprehend the manifestation of God through the Word and his communication through the Spirit, both of them substantially in Christ alone."

This theology, though original in some respects, has often been compared to Adoptionism, Arianism, and Sabellianism, all of which Trinitarians rejected in favour of the belief that God exists eternally in three distinct persons. Nevertheless, Servetus rejected these theologies in his books: Adoptionism, because it denied Jesus's divinity; Arianism, because it multiplied the hypostasis (Christianity), hypostases and established a rank; and Sabellianism, because it seemingly confused the Father with the Son, though Servetus himself does appear to have denied or diminished the distinctions between the Persons of the Godhead, rejecting the Trinitarian understanding of One God in Three Persons.

The incomprehensible God is known through Christ, by faith, rather than by philosophical speculations. He manifests God to us, being the expression of His very being, and through him alone, God can be known. The scriptures reveal Him to those who have faith; and thus we come to know the Holy Spirit as the Divine impulse within us.Under severe pressure from Catholics and Protestants alike, Servetus clarified this explanation in his second book, ''Dialogues'' (1532), to show the Logos coterminous with Christ. He was nevertheless accused of

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

because of his insistence on denying the dogma of the Trinity and the distinctions between the three divine Persons in one God.

Legacy

Theology

Because of his rejection of the Trinity and eventual execution by burning forheresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, Unitarianism, Unitarians often regard Servetus as the first (modern) Unitarian martyr—though he was a Unitarian in neither the 17th-century sense of the term nor the modern sense. Sharply critical though he was of the orthodox formulation of the trinity, Servetus is better described as a highly unorthodox trinitarian.Hughes, Peter. "Michael Servetus", ''Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography''Aspects of his thinking—his critique of existing trinitarian theology, his devaluation of the doctrine of original sin, and his fresh examination of biblical proof-texts—did influence those who later inspired or founded unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania. Other non-trinitarian groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, and Oneness Pentecostalism, also claim Servetus held similar non-trinitarian views as theirs. Oneness Pentecostalism particularly identifies with Servetus' teaching on the divinity of Jesus Christ and his insistence on the oneness of God, rather than a Trinity of three distinct persons: "And because His Spirit was wholly God He is called God, just as from His flesh He is called man." Oneness Pentecostal Scholar David K. Bernard has written the following in regard to the theology of Michael Servetus: "... some historians consider him to be a motivating force for the development of Unitarianism. However, he definitely was not Unitarian, for he acknowledged Jesus as God." Swedenborg wrote a systematic theology that had many similarities to the theology of Servetus.

Freedom of conscience

Widespread aversion to Servetus's death has been taken as signaling the birth in Europe of the idea of religious tolerance, a principle now more important to modern Unitarian Universalists than antitrinitarianism. The Spanish scholar on Servetus' work, Ángel Alcalá, identified the radical search for truth and the right for freedom of conscience as Servetus' main legacies, rather than his theology. The Polish-American scholar, Marian Hillar, has studied the evolution of freedom of conscience, from Servetus and the Polish Socinians, to John Locke and to Thomas Jefferson and the American Declaration of Independence. According to Hillar: "Historically speaking, Servetus died so that freedom of conscience could become a civil right in modern society."Science

Servetus was the first European to describe the function ofpulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. One was that the description appeared in a theological treatise, ''Christianismi Restitutio'', not in a book on medicine. However, the sections in which he refers to anatomy and medicines demonstrate an amazing understanding of the body and treatments. Most copies of the book were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities. Three copies survived, but these remained hidden for decades. In passage V, Servetus recounts his discovery that the blood of the pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

flows from the heart to the lungs (rather than air in the lungs flowing to the heart as had been thought). His discovery was based on the colour of the blood, the size and location of the different ventricle (heart), ventricles, and the fact that the pulmonary vein was extremely large, which suggested that it performed intensive and transcendent exchange. However, Servetus does not only deal with cardiology. In the same passage, from page 169 to 178, he also refers to the brain, the cerebellum, the meninges, the nerves, the eye, the tympanum (anatomy), tympanum, the rete mirabile, etc., demonstrating a great knowledge of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

. In some other sections of this work he also talks of medical products.

Servetus also contributed enormously to medicine with other published works specifically related to the field, such as his ''Complete Explanation of Syrups'' and his study on syphilis in his ''Apology against Leonhart Fuchs'', among others.

References in literature

*Austrian author Stefan Zweig features Servetus in ''The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin'', 1936 (original title ''Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt'') *Canadian dramatist Robert Lalonde wrote ''Vesalius and Servetus'', a 2008 play on Servetus. *Roland Herbert Bainton: ''Michael Servet. 1511–1553.'' Mohn, Gütersloh 1960 *Rosemarie Schuder: ''Serveto vor Pilatus.'' Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1982 *Antonio Orejudo: ''Feuertäufer.'' Knaus, München 2005, (Roman, Spanish original title: ''Reconstrucción.'') *Vincent Schmidt: ''Michel Servet. Du bûcher à la liberté de conscience'', Les Éditions de Paris, Collection Protestante, Paris 2009 *Albert J. Welti: ''Servet in Genf''. Genf, 1931 *Wilhelm Knappich: ''Geschichte der Astrologie''. Veröffentlicht von Vittorio Klostermann, 1998, , *Friedrich Trechsel: ''Michael Servet und seine Vorgänger''. Nach Quellen und Urkunden geschichtlich Dargestellt. Universitätsbuchhandlung Karl Winter, Heidelberg 1839 (Reprint durch: Nabu Press, 2010, ) *Hans-Jürgen Goertz: ''Religiöse Bewegungen in der Frühen Neuzeit'' Oldenbourg, München 1992, *Henri Tollin: ''Die Entdeckung des Blutkreislaufs durch Michael Servet, 1511–1553'', Nabu Public Domain Reprints *Henri Tollin: ''Charakterbild Michael Servet´s'', Nabu Public Domain Reprints *Henri Tollin: ''Das Lehrsystem Michael Servet´s Volume 1'', Nabu Public Domain Reprints *Henri Tollin: ''Das Lehrsystem Michael Servet´s Volume 2'', Nabu Public Domain Reprints *Henri Tollin: ''Michaelis Villanovani (Serveti) in quendam medicum apologetica disceptatio pro astrologia: Nach dem einzig vorhandenen echten Pariser Exemplare, mit einer Einleitung und Anmerkungen.'' Mecklenburg −1880 *Carlos Gilly: ''Miguel Servet in Basel''; ''Alfonsus Lyncurius und Pseudo-Servet''. In: Ders.: ''Spanien und der Basler Buchdruck bis 1600''. Helbing & Lichtenhahhn, Basel und Frankfurt a.M. 1985, pp. 277–298; 298–326.PDF; 64,1 MiB

) *M. Hillar: "Poland's Contribution to the Reformation: Socinians/Polish Brethren and Their Ideas on the Religious Freedom," The Polish Review, Vol. XXXVIII, No.4, pp. 447–468, 1993. *M. Hillar, "From the Polish Socinians to the American Constitution," in A Journal from the Radical Reformation. A Testimony to Biblical Unitarianism, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 22–57, 1994. *José Luis Corral: ''El médico hereje'', Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, S.A., 2013 . A novel (in Spanish) narrating the publication of ''Christianismi Restitutio'', Servetus' trial by the Inquisition of Vienne, his escape to Geneva, and his disputes with John Calvin and subsequent burning at the stake by the Calvinists.

Honours

Geneva

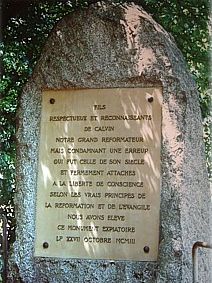

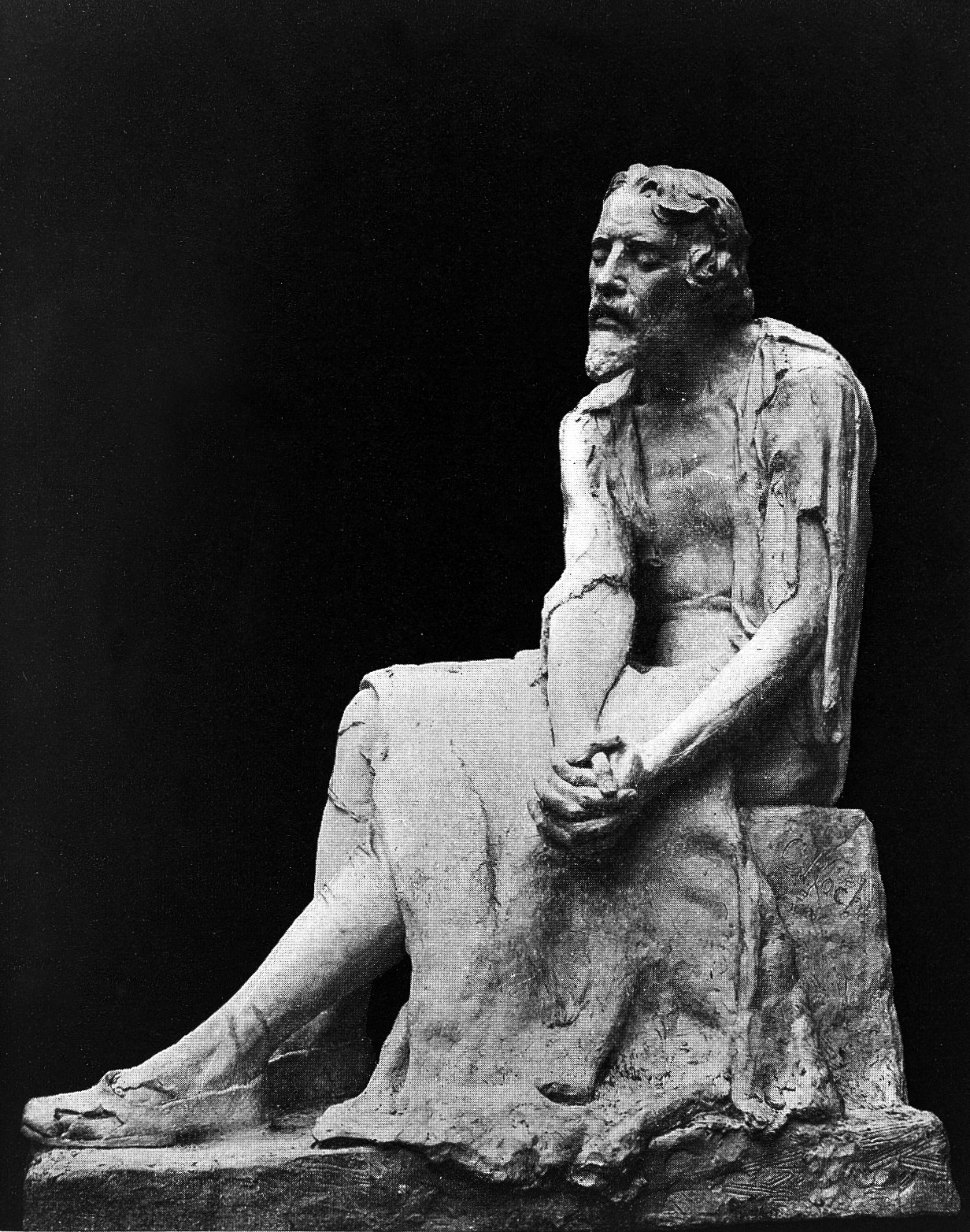

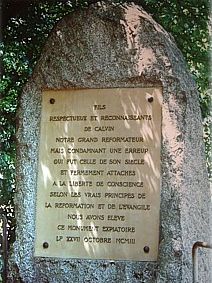

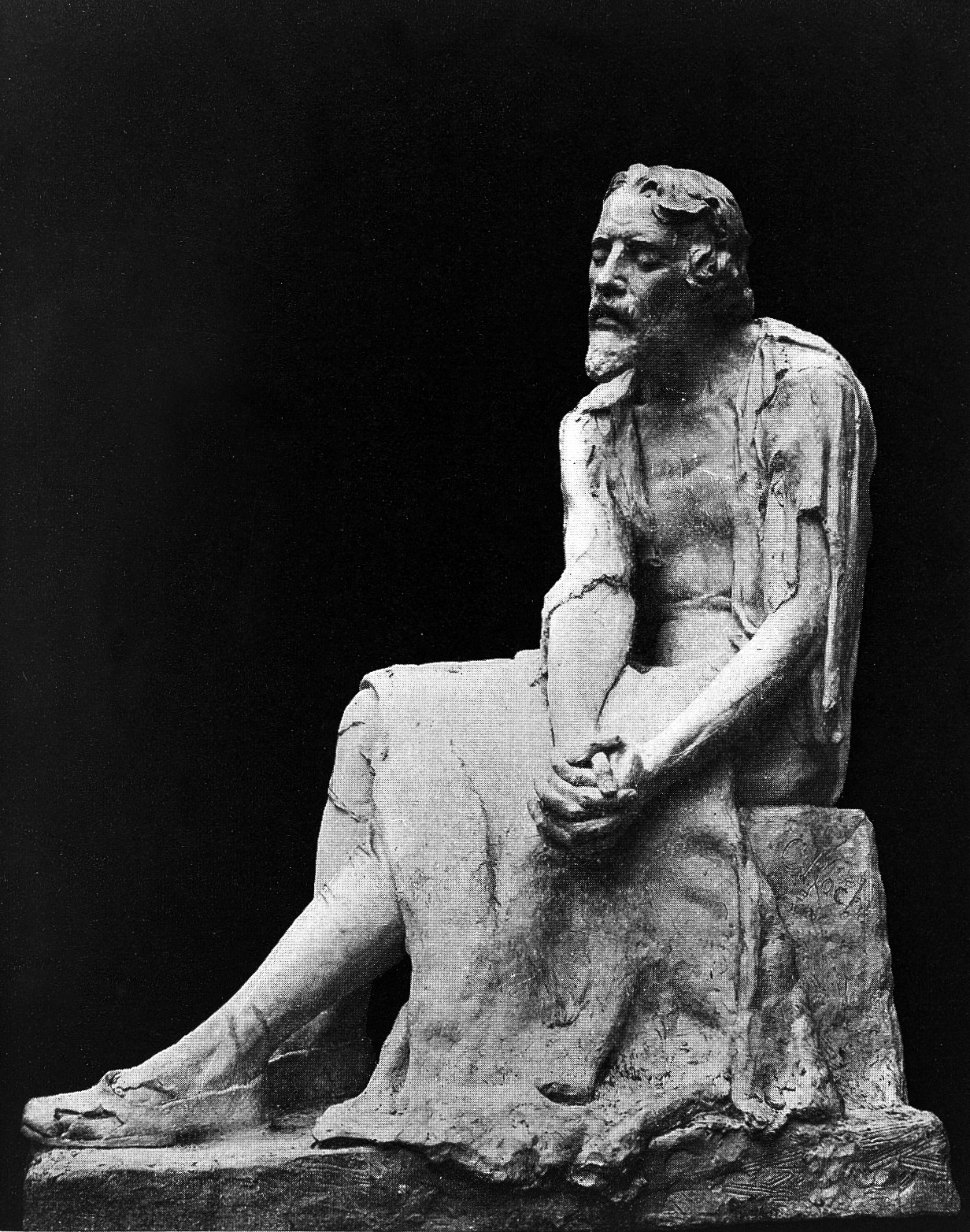

In Geneva, 350 years after the execution, remembering Servetus was still a controversial issue. In 1903 a committee was formed by supporters of Servetus to erect a monument in his honour. The group was led by a French Senator, , an author of a book on heretics and revolutionaries which was published in 1887. The committee commissioned a local sculptor, Clotilde Roch, to execute a statue showing a suffering Servetus. The work was three years in the making and was finished in 1907. However, by then, supporters of Calvin in Geneva, having heard about the project, had already erected a simple stele in memory of Servetus in 1903, the main text of which served more as an apologetic for Calvin:

In Geneva, 350 years after the execution, remembering Servetus was still a controversial issue. In 1903 a committee was formed by supporters of Servetus to erect a monument in his honour. The group was led by a French Senator, , an author of a book on heretics and revolutionaries which was published in 1887. The committee commissioned a local sculptor, Clotilde Roch, to execute a statue showing a suffering Servetus. The work was three years in the making and was finished in 1907. However, by then, supporters of Calvin in Geneva, having heard about the project, had already erected a simple stele in memory of Servetus in 1903, the main text of which served more as an apologetic for Calvin:

Duteous and grateful followers of Calvin our great Reformer, yet condemning an error which was that of his age, and strongly attached to liberty of conscience according to the true principles of his Reformation and gospel, we have erected this expiatory monument. Oct. 27, 1903About the same time, a short street close by the stele was named after him. The city council then rejected the request of the committee to erect the completed statue, on the grounds that there was already a monument to Servetus. The committee then offered the statue to the neighbouring French town of Annemasse, which in 1908 placed it in front of the city hall, with the following inscriptions:

"The arrest of Servetus in Geneva, where he did neither publish nor dogmatize, hence he was not subject to its laws, has to be considered as a barbaric act and an insult to the Right of Nations". Voltaire

"I beg you, shorten please these deliberations. It is clear that Calvin for his pleasure wishes to make me rot in this prison. The lice eat me alive. My clothes are torn and I have nothing for a change, nor shirt, only a worn out vest". Servetus, 1553In 1942, the Vichy France, Vichy Government took down the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience, and melted it. In 1960, having found the original molds, Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place. Finally, on 3 October 2011, Geneva erected a copy of the statue which it had rejected over 100 years before. It was cast in Aragon from the molds of Clotilde Roch's original statue. Rémy Pagani, former mayor of Geneva, inaugurated the statue. He previously had described Servetus as "the dissident of dissidence." Representatives from the Roman Catholic Church in Geneva and the Director of Geneva's International Museum of the Reformation attended the ceremony. A Geneva newspaper noted the absence of officials from the National Protestant Church of Geneva, the church of John Calvin.

Aragon

In 1984, the Zaragoza public hospital changed its name from ''José Antonio Primo de Rivera, José Antonio'' to ''Miguel Servet''. Since 1999, this hospital has been known as the ''Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet'', in recognition of its association with Servetus' own University of ZaragozaWorks

Only the dates of the first editions are included. *1531 ''On the Errors of the Trinity. De Trinitatis Erroribus.'' Haguenau printed by Hans Setzer. Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city in which it was printed. Signed as Michael Servete alias Revés, from Aragon, Spanish. Written in Latin, it also includes words in Greek and in Hebrew in the body of the text whenever he wanted to stress the original meaning of a word from Scripture.Wilbur, E.M. (1969)The two treatises of Servetus on the Trinity

', New York, Kraus Reprint Co., pp. vii–xviii *1532 ''Dialogues on the Trinity. Dialogorum de Trinitate.'' Haguenau, printed by Hans Setzer. Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city where it was printed. Signed as Michael Serveto alias Revés, from Aragon, Spanish. *1535 ''Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Claudii Ptolemaeii Alexandrinii Geographicae''. Lyon, Trechsel. Signed as Michel de Villeneuve. Servetus dedicated this work to Hugues de la Porte. The second edition was dedicated to Pierre Palmier. Michel de Villeneuve states that the basis of his edition comes from the work of Bilibald Pirkheimer, who translated this work from Greek to Latin, but Michel also affirms that he also compared it to the primitive Greek texts. The 19th-century expert in Servetus, Henri Tollin (1833–1902), considered him to be "the father of comparative geography" due to the extension of his notes and commentaries. *1536 ''The Apology against Leonard Fuchs. In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia.'' Lyon, printed by Gilles Hugetan, with Parisian prologue. Signed as Michel de Villeneuve. The physician Leonhart Fuchs and a friend of Michael Servetus, Symphorien Champier, got involved in an argument ''via'' written works, on their different Lutheran and Catholic beliefs. Servetus defends his friend in the first parts of the work. In the second part he talks of a medical plant and its properties. In the last part he writes on different topics, such as the defense of a pupil attacked by a teacher, and the origin of syphilis. *1537 ''Complete Explanation of the Syrups. Syruporum universia ratio''. Paris, printed by Simon de Colines. Signed as Michael de Villeneuve. This work consists of a prologue "The Use of Syrups", and 5 chapters: I "What the concoction is and why it is unique and not multiple", II "What the things that must be known are", III "That the concoction is always..", IV "Exposition of the aphorisms of Hippocrates" and V "On the composition of syrups". Michel de Villeneuve refers to experiences of using the treatments, and to pharmaceutical treatises and terms more deeply described in his later pharmacopeia ''Enquiridion'' or ''Dispensarium''. Michel mentions two of his teachers, Sylvius and Andernach, but above all, Galen. This work had a strong impact in those times. *1538 ''Apologetic discourse of Michel de Villeneuve in favour of Astrology and against a certain physician. Michaelis Villanovani in quedam medicum apologetica disceptatio pro Astrologia.'' Paris, unknown printer. Servetus denounces Jean Tagault, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris, for attacking astrology, while many great thinkers and physicians praised it. He lists reasonings of Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen, how the stars are related to some aspects of a patient's health, and how a good physician can predict effects by them: the effect of the moon and sun on the sea, the winds and rains, the period of women, the speed of the decomposition of the corpses of beasts, etc. *1542 ''Holy Bible according to the translation of Santes Pagnino. Biblia sacra ex Santes Pagnini tralation, hebraist.'' Lyon, edited by Delaporte and printed by Trechsel. The name Michel de Villeneuve appears in the prologue, the last time this name would appear in any of his works. *1542 ''Biblia sacra ex postremis doctorum'' (octavo). Vienne in Dauphiné, edited by Delaporte and printed by Trechsel. Anonymous. *1545 ''Holy Bible with commentaries. Biblia Sacra cum Glossis.'' Lyon, printed by Trechsel and Vincent. Called "Ghost Bible" by scholars who denied its existence. There is an anonymous work from this year that was edited in accordance with the contract that Miguel de Villeneuve made with the Company of Booksellers in 1540. The work consists of 7 volumes (6 volumes and an index) illustrated by Hans Holbein the Younger, Hans Holbein. This research was carried out by the scholar Julien Baudrier in the sixties. Recently scholar González Echeverría has graphically proved the existence of this work, and demonstrating that contrary to what experts Barón and Hillard thought, this work is also anonymous. *"Manuscript of Paris" (c. 1546). This document is a draft of the ''Christianismi Restitutio''. Written in Latin, it includes a few quotes in Greek and Hebrew. This work has paleographically the same handwriting as the "Manuscript of the Complutense". *1553 ''The Restoration of Christianity. Cristianismi Restitutio''. Vienne, Isère, Vienne, printed by Baltasar Arnoullet. Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city in which it was printed. Signed as M.S.V. at the colophon though "Servetus" name is mentioned inside, in a fictional dialog. Servetus uses Biblical quotes in Greek and in Hebrew on its cover and in the body of the text whenever he wanted to stress the original meaning of a word from Scripture.

Servetus's anonymous editions