Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

No African-American candidate was given serious consideration for appointment to the Supreme Court until the election of

No African-American candidate was given serious consideration for appointment to the Supreme Court until the election of

The words "

The words "

"The Supreme Court; Conservative black judge, Clarence Thomas, is named to Marshall's court seat"

, ''The New York Times'', July 2, 1991.) was the first Hispanic judge for whom such an appointment was contemplated. Subsequently,

Senate Democrats Are Shifting Focus From Roberts to Other Seat

, ''The New York Times'', September 9, 2005. Alberto Gonzales,Specter: Gonzales Not Ready for Supreme Court

, ''Capitol Hill Blue'', September 12, 2005. and Consuelo M. Callahan were under consideration for the vacancy left by the retirement of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor's seat eventually went to Samuel Alito, however. Speculation about a Hispanic nomination arose again after the election of

Of the 116 justices, 110 (94.8 percent) have been men. All Supreme Court justices were males until 1981, when Ronald Reagan fulfilled his 1980 campaign promise to place a woman on the court, which he did with the appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor was later joined on the court by

Of the 116 justices, 110 (94.8 percent) have been men. All Supreme Court justices were males until 1981, when Ronald Reagan fulfilled his 1980 campaign promise to place a woman on the court, which he did with the appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor was later joined on the court by

Judging Women

", ''

NPR website

and transcript found a

NPR website

. Cited by Sarah Pulliam Bailey, "The Post-Protestant Supreme Court: Christians weigh in on whether it matters that the high court will likely lack Protestant representation," '' Christianity Today'', April 10, 2010, found a

Christianity Today website

. Also cited by "Does the U.S. Supreme Court need another Protestant?" ''

USA Today website

. All accessed April 10, 2010. Richard W. Garnett, "The Minority Court", ''

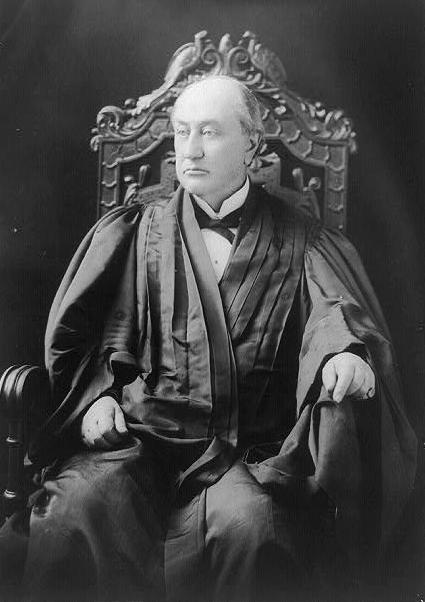

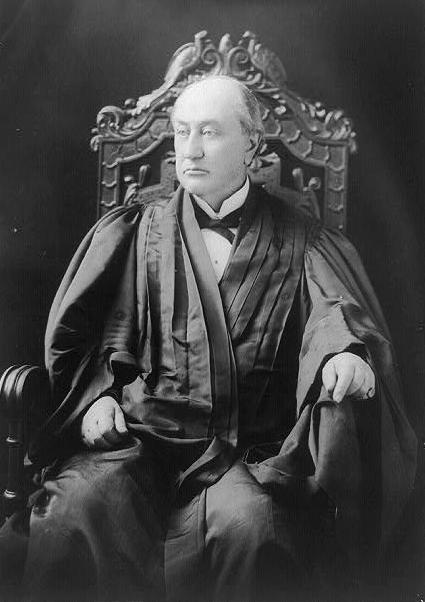

The first Catholic justice,

The first Catholic justice,

''

In 1853, President

In 1853, President

Unlike the offices of President, U.S. Representative, and U.S. Senator, there is no minimum age for Supreme Court justices set forth in the United States Constitution. However, justices tend to be appointed after having made significant achievements in law or politics, which excludes many young potential candidates from consideration. At the same time, justices appointed at too advanced an age will likely have short tenures on the court.

The youngest justice ever appointed was

Unlike the offices of President, U.S. Representative, and U.S. Senator, there is no minimum age for Supreme Court justices set forth in the United States Constitution. However, justices tend to be appointed after having made significant achievements in law or politics, which excludes many young potential candidates from consideration. At the same time, justices appointed at too advanced an age will likely have short tenures on the court.

The youngest justice ever appointed was  The average age of the court as a whole fluctuates over time with the departure of older justices and the appointment of younger people to fill their seats. , the youngest sitting Justice at the time of appointment is Clarence Thomas, who was 43 years old at the time of his confirmation in 1991. Following the appointment of

The average age of the court as a whole fluctuates over time with the departure of older justices and the appointment of younger people to fill their seats. , the youngest sitting Justice at the time of appointment is Clarence Thomas, who was 43 years old at the time of his confirmation in 1991. Following the appointment of

Although the Constitution imposes no educational background requirements for federal judges, the work of the court involves complex questions of

Although the Constitution imposes no educational background requirements for federal judges, the work of the court involves complex questions of

"Trump's pick: Gorsuch is respected jurist — and another multimillionaire"

,Court Without a Quorum

", ''The New York Times'' (May 18, 2008), Section WK; Column 0; Editorial Desk; p. 11.

Religious Affiliation of the U.S. Supreme Court

from Adherents.com

from the Cornell Law School website {{good article Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court

The demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States encompass the

the gender, race, educational background or religious views of the justices has played little documented role in their jurisprudence. For example, the opinions of the first two African-American justices reflected radically different judicial philosophies; William Brennan and Antonin Scalia shared Catholic faith and a Harvard Law School education, but shared little in the way of jurisprudential philosophies. The court's first two female justices voted together no more often than with their male colleagues, and historian Thomas R. Marshall writes that no particular "female perspective" can be discerned from their opinions.

decade of 1866–1876, there was always a southerner on the bench. Until 1867, the sixth seat was reserved as the "southern seat". Until Cardozo's appointment in 1932, the third seat was reserved for New Englanders." The westward expansion of the U.S. led to concerns that the western states should be represented on the court as well, which purportedly prompted gender

Gender is the range of characteristics pertaining to femininity and masculinity and differentiating between them. Depending on the context, this may include sex-based social structures (i.e. gender roles) and gender identity. Most cultures ...

, ethnicity, and religious, geographic, and economic backgrounds of the 116 people who have been appointed and confirmed as justices to the Supreme Court. Some of these characteristics have been raised as an issue since the court was established in 1789. For its first 180 years, justices were almost always white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

male

Male (symbol: ♂) is the sex of an organism that produces the gamete (sex cell) known as sperm, which fuses with the larger female gamete, or ovum, in the process of fertilization.

A male organism cannot reproduce sexually without access to ...

Protestants of Anglo

Anglo is a prefix indicating a relation to, or descent from, the Angles, England, English culture, the English people or the English language, such as in the term ''Anglosphere''. It is often used alone, somewhat loosely, to refer to peopl ...

or Northwestern Europe

Northwestern Europe, or Northwest Europe, is a loosely defined subregion of Europe, overlapping Northern and Western Europe. The region can be defined both geographically and ethnographically.

Geographic definitions

Geographically, North ...

an descent.

Prior to the 20th century, a few Catholics were appointed, but concerns about diversity on the court were mainly in terms of geographic diversity, to represent all geographic regions of the country, as opposed to ethnic, religious, or gender diversity. The 20th century saw the first appointment of justices who were Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

( Louis Brandeis, 1916), African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

(Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

, 1967), female ( Sandra Day O'Connor, 1981), and Italian-American

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, ...

( Antonin Scalia, 1986). The first appointment of a Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties forme ...

justice was in the 21st century with Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

in 2009, with the possible exception of Justice Benjamin Cardozo

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's th ...

, a Sephardi Jew of Portuguese descent, who was appointed in 1932.

In spite of the interest in the court's demographics and the symbolism accompanying the inevitably political appointment process, and the views of some commentators that no demographic considerations should arise in the selection process,John P. McIver, Department of Political Science, University of Colorado, Boulder ''Review of A "REPRESENTATIVE" SUPREME COURT? THE IMPACT OF RACE, RELIGION, AND GENDER ON APPOINTMENTS by Barbara A. Perry''.the gender, race, educational background or religious views of the justices has played little documented role in their jurisprudence. For example, the opinions of the first two African-American justices reflected radically different judicial philosophies; William Brennan and Antonin Scalia shared Catholic faith and a Harvard Law School education, but shared little in the way of jurisprudential philosophies. The court's first two female justices voted together no more often than with their male colleagues, and historian Thomas R. Marshall writes that no particular "female perspective" can be discerned from their opinions.

Geographic background

For most of the existence of the court, geographic diversity was a key concern of presidents in choosing justices to appoint. This was prompted in part by the early practice of Supreme Court justices also "riding circuit"—individually hearing cases in different regions of the country. In 1789, the United States was divided into judicial circuits, and from that time until 1891, Supreme Court justices also acted as judges within those individual circuits.George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

was careful to make appointments "with no two justices serving at the same time hailing from the same state". Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

broke with this tradition during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, and "by the late 1880s presidents disregarded it with increasing frequency". Segal and Spaeth (2002), quoting Richard Friedman, "The Transformation in Senate Response to Supreme Court Nominations", 5 Cardozo Law Review 1 (1983), p. 50.

Although the importance of regionalism declined, it still arose from time to time. For example, in appointing Benjamin Cardozo

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's th ...

in 1929, President Hoover was as concerned about the controversy over having three New York justices on the court as he was about having two Jewish justices. David M. O'Brien notes that "from the appointment of John Rutledge from South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

in 1789 until the retirement of Hugo Black rom_Alabama.html"_;"title="Alabama.html"_;"title="rom_Alabama">rom_Alabama">Alabama.html"_;"title="rom_Alabama">rom_Alabamain_1971,_with_the_exception_of_the_Reconstruction_era_of_the_United_States.html" "title="Alabama">rom_Alabama.html" ;"title="Alabama.html" ;"title="rom Alabama">rom Alabama">Alabama.html" ;"title="rom Alabama">rom Alabamain 1971, with the exception of the Reconstruction era of the United States">Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

to make his 1910 appointment of Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Four ...

of Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...

.

Geographic balance was sought in the 1970s, when Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

attempted to employ a "Southern strategy", hoping to secure support from Southern states by nominating judges from the region. Nixon unsuccessfully nominated Southerners Clement Haynsworth

Clement Furman Haynsworth Jr. (October 30, 1912 – November 22, 1989) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. He was also an unsuccessful nominee for the United States Supreme Court in 1969 ...

of South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and G. Harrold Carswell of Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, before finally succeeding with the nomination of Harry Blackmun of Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

. The issue of regional diversity was again raised with the 2010 retirement of John Paul Stevens, who had been appointed from the midwestern Seventh Circuit, leaving the court with all but one Justice having been appointed from states on the East Coast.

, the court has a majority from the Northeastern United States, with five justices coming from states to the north and east of Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

: two justices born in New York (two in New York City), one in New Jersey, and two from Washington D.C. itself. The remaining four justices come from Georgia, California, Colorado, and Indiana; until the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. ...

of Indiana in 2020, the most recent justice from the Midwest had been John Paul Stevens of Illinois who retired in 2010. Contemporary justices may be associated with multiple states. Many nominees are appointed while serving in states or districts other than their hometown or home state. Chief Justice John Roberts, for example, was born in Buffalo, New York, but moved to Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

at the age of five, where he grew up. After law school, Roberts worked in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

while living in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. Thus, three states may claim to be his home state. Justice Barrett is another example; although her commission identifies her as being from Indiana, she was born in , raised in the adjacent suburb of Metairie, Louisiana, and did not live in Indiana until law school.

Some states have been over-represented, partly because there were fewer states from which early justices could be appointed. New York has produced fifteen justices, three of whom have served as chief justice. Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

has produced ten justices, including two chief justices; Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

nine (including Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan); and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

eight, including three chief justices. There have been six justices each from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

(the latter including current chief justice John Roberts and current associate justice Brett Kavanaugh); and five each from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. States that have produced four justices include California, Illinois (one chief and three associates each), and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

.

Other states from which justices have been appointed

* Three justices have been appointed from Connecticut (2 chiefs and 1 associate). * Three justices have been appointed from South Carolina (1 chief, 1 chief who was earlier an associate, and 1 associate). * Three associate justices have been appointed from Alabama. * Two associate justices have been appointed from Colorado, including current associate justice Neil Gorsuch. * Two associate justices have been appointed from Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, and New Hampshire. * One associate justice has been appointed from Arizona, while another associate justice who later became chief was born there had moved to Virginia prior to their appointment. * One justice, who served both as an associate and as chief, has been appointed from Louisiana; current associate justice Amy Coney Barrett was born there but had moved to Indiana prior to her appointment. * One associate justice has been appointed from Kansas, Maine, Missouri, Mississippi, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming.States from which no justices have been appointed

Despite the efforts to achieve geographic balance, only seven justices have ever hailed from states admitted after or during theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. Nineteen states have never produced a Supreme Court justice. In order of admission to the Union

Admission may refer to:

Arts and media

* "Admissions" (''CSI: NY''), an episode of ''CSI: NY''

* ''Admissions'' (film), a 2011 short film starring James Cromwell

* ''Admission'' (film), a 2013 comedy film

* ''Admission'', a 2019 album by Florida s ...

these are:

# Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

(original state)

# Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

(original state)

# Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

(admitted in 1791)

# Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

(admitted in 1836)

# Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

(admitted in 1845)

# Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

(admitted in 1848)

# Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

(admitted in 1859)

# West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

(admitted in 1863)

# Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

(admitted in 1864)

# Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

(admitted in 1867)

# North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, So ...

(admitted in 1889)

# South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large porti ...

(admitted in 1889)

# Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

(admitted in 1889)

# Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

(admitted in 1889)

# Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyomi ...

(admitted in 1890)

# Oklahoma (admitted in 1907)

# New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

(admitted in 1912)

# Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

(admitted in 1959)

# Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

(admitted in 1959)

Foreign birth

Six justices were born outside the United States. These includedJames Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

(1789–1798), born in Ceres, Fife

Ceres is a village in Fife, Scotland, located in a small glen approximately over the Ceres Moor from Cupar and from St Andrews. The former parish of that name included the settlements of Baldinnie, Chance Inn, Craigrothie, Pitscottie and Tarvit ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

; James Iredell (1790–1799), born in Lewes, England; and William Paterson (1793–1806), born in County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population o ...

, then in the Kingdom of Ireland. Justice David J. Brewer (1889–1910) was born farthest from the U.S., in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, (now İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban aggl ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

), where his parents were missionaries at the time. George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was an English-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

(1922–1939) was born in Buckinghamshire, England. The last foreign-born justice, and the only one of these for whom English was a second language, was Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

(1939–1962), born in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

(now in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

). The Constitution imposes no citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

requirement on federal judges.

Ethnicity

All Supreme Court justices werewhite

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

and of European heritage until the appointment of Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

, the first African-American Justice, in 1967. Since then, only three other non-white justices have been appointed: Marshall's African-American successor, Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

, in 1991, Latina Justice Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

in 2009, and African-American Ketanji Brown Jackson

Ketanji Onyika Brown Jackson ( ; born September 14, 1970) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Jackson was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Joe Biden on February 25, 202 ...

in 2022.

Graphical timeline of non-white justices:

White justices

The majority of white justices have been Protestants ofBritish

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

ethnicity. There have been several justices of Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

or Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish ( ga, Gaeilig Uladh, IPA=, IPA ga=ˈɡeːlʲɪc ˌʊlˠuː) is the variety of Irish spoken in the province of Ulster. It "occupies a central position in the Gaelic world made up of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man". Ulster Ir ...

descent, with William Paterson born in Ireland to an Ulster Scots Protestant family and Joseph McKenna, Edward Douglas White, Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* P ...

, Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

, William J. Brennan Jr., Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

, and Brett Kavanaugh

Brett Michael Kavanaugh ( ; born February 12, 1965) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018, and has served since ...

being of Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

origin. There have been five justices of French ancestry in John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

, Gabriel Duval, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, Joseph Rucker Lamar

Joseph Rucker Lamar (October 14, 1857 – January 2, 1916) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court appointed by President William Howard Taft. A cousin of former associate justice Lucius Lamar, he served from 1911 until hi ...

Schmidhauser, John Richard; ‘The Justices of the Supreme Court: A Collective Portrait’; ''Midwest Journal of Political Science

The ''American Journal of Political Science'' is a journal published by the Midwest Political Science Association. It was formerly known as the ''Midwest Journal of Political Science''. According to the '' Journal Citation Reports'', the journal ...

''; vol. 3, no. 1 (February 1959), pp. 1–57 and Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. ...

, with all except the Catholic Barrett being Protestants of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

origins. Many justices – including John Jay, William Johnson, and Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Four ...

– have been of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

Protestant origin, whilst the only two Scandinavian Americans

Nordic and Scandinavian Americans are Americans of Scandinavian and/or Nordic ancestry, including Danish Americans (estimate: 1,453,897), Faroese Americans, Finnish Americans (estimate: 653,222), Greenlandic Americans, Icelandic Americans ( ...

to serve on the court have been Chief Justices Earl Warren and William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

.

Up until the 1980s, only eight justices of "central, eastern, or southern European derivation" had been appointed, and even among these justices, five of them "were of Germanic background, which includes Austrian, German-Bohemian, and Swiss origins ( John Catron, Samuel F. Miller, Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

, and Warren Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986. Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul Colleg ...

)", with Brandeis and Frankfurter being of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, while only one justice was of non-Germanic, Southern European descent (Benjamin N. Cardozo

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo (May 24, 1870 – July 9, 1938) was an American lawyer and jurist who served on the New York Court of Appeals from 1914 to 1932 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1932 until his deat ...

, of Sephardic Jewish descent).Schmidhauser, John Richard; ''Judges and justices: the Federal Appellate Judiciary'' (1979), p. 60. Cardozo, appointed to the court in 1932, was the first justice known to have non-Germanic, non-Anglo-Saxon or non-Irish ancestry and the first justice of Southern European

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alba ...

descent. Both of Justice Cardozo's parents descended from Sephardic Jews

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

from the Iberian Peninsula who fled to Holland during the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

, then to London, before arriving in New York prior to the American Revolution. At least two, Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from R ...

and Arthur Goldberg

Arthur Joseph Goldberg (August 8, 1908January 19, 1990) was an American statesman and jurist who served as the 9th U.S. Secretary of Labor, an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the 6th United States Ambassador to ...

, were of Eastern European Ashkenazi descent.

Justice Antonin Scalia, who served from 1986 to 2016, and Justice Samuel Alito, who has served since 2006, are the first justices of Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

descent to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Justice Scalia's father and both maternal grandparents as well as both of Justice Alito's parents were born in Italy. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by Presiden ...

was born to a Jewish father who immigrated from Russia at age 13 and a Jewish mother who was born four months after her parents immigrated from Poland.

Amongst white ethnicities, according to a 1959 article, there had never been a Justice with any Slavic ancestry.

African-American justices

No African-American candidate was given serious consideration for appointment to the Supreme Court until the election of

No African-American candidate was given serious consideration for appointment to the Supreme Court until the election of John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, who weighed the possibility of appointing William H. Hastie of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (in case citations, 3d Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts for the following districts:

* District of Delaware

* District of New Jersey

* East ...

.Sheldon Goldman, ''Picking Federal Judges: Lower Court Selection from Roosevelt Through Reagan'' (1999), p. 184-85. Hastie had been the first African-American elevated to a Court of Appeals when Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

had so appointed him in 1949, and by the time of the Kennedy Administration, it was widely anticipated that Hastie might be appointed to the Supreme Court. Kennedy gave serious consideration to this appointment, ensuring that this "represented the first time in American history that an African American was an actual contender for the high court".

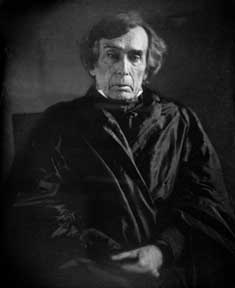

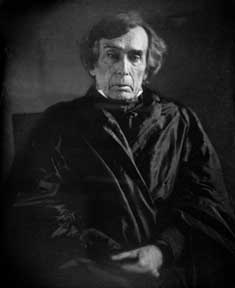

The first African-American appointed to the court was Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

, appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

in 1967. Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court following the retirement of Justice Tom C. Clark, saying that this was "the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place." Marshall was confirmed

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

as an Associate Justice by a Senate vote of 69—11 on August 31, 1967. Johnson confidently predicted to one biographer, Doris Kearns Goodwin

Doris Helen Kearns Goodwin (born January 4, 1943) is an American biographer, historian, former sports journalist, and political commentator. She has written biographies of several U.S. presidents, including ''Lyndon Johnson and the American Drea ...

, that a lot of black baby boys would be named "Thurgood" in honor of this choice (in fact, Kearns's research of birth records in New York and Boston indicates that Johnson's prophecy did not come true).

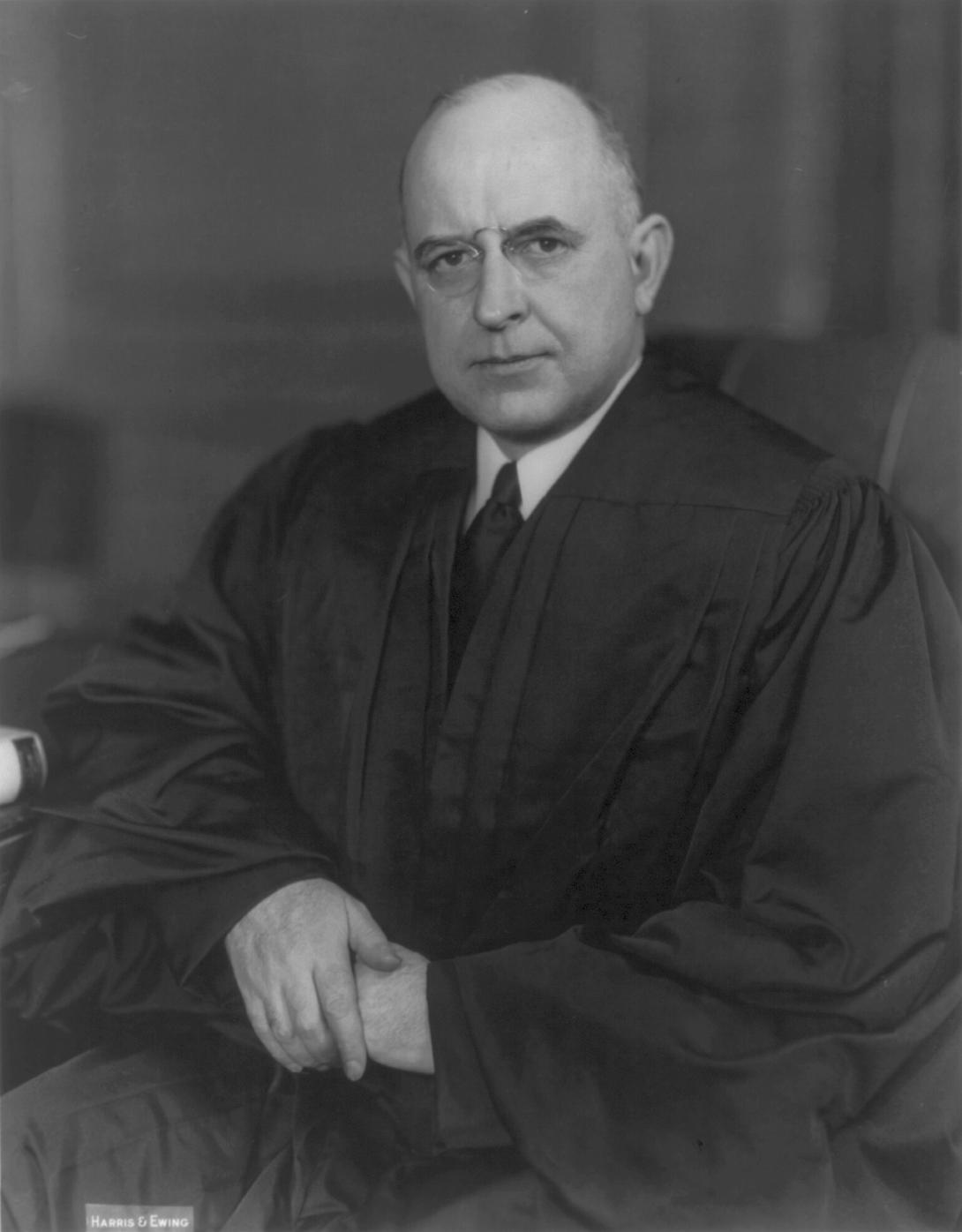

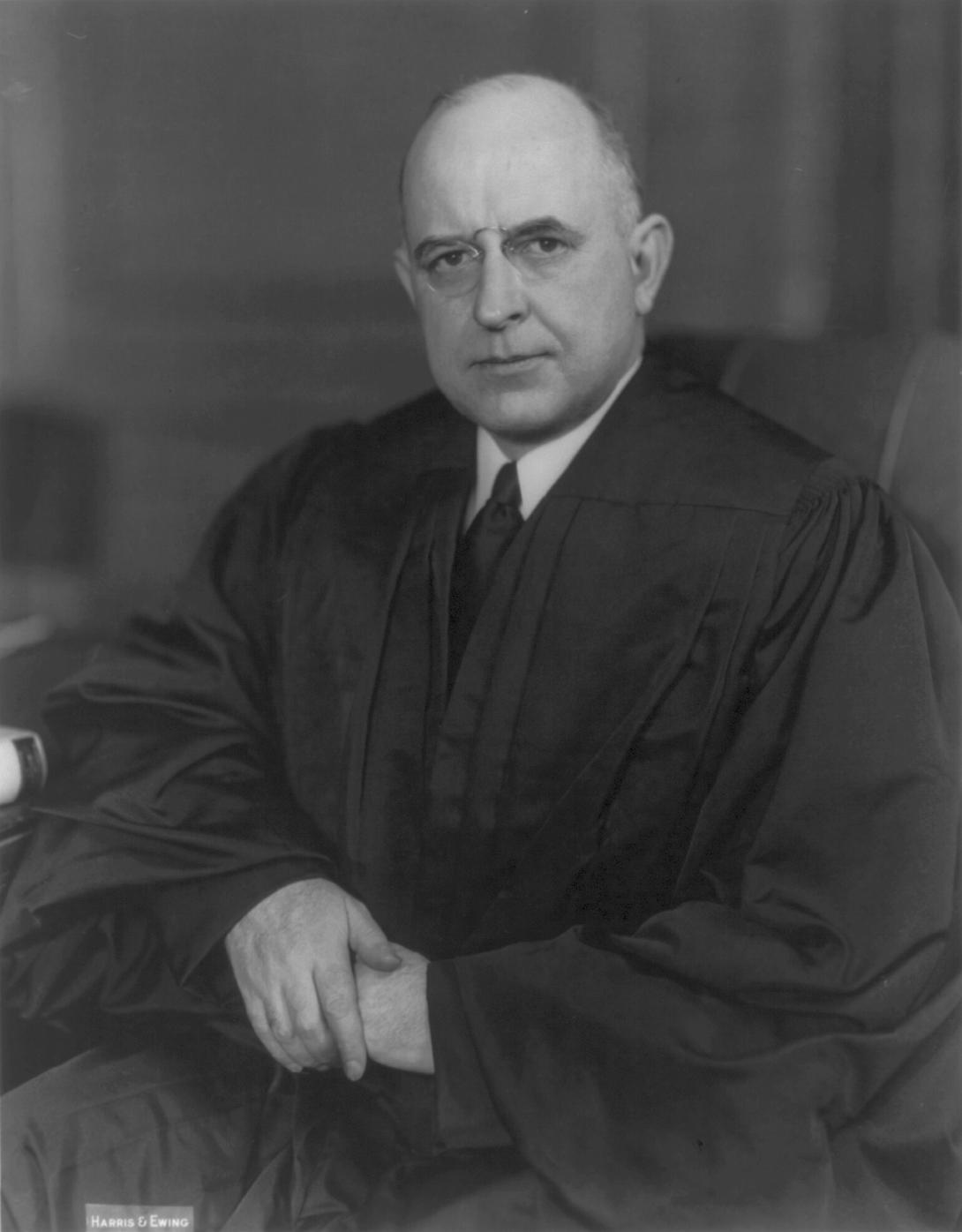

The second was Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

, appointed by George H. W. Bush to succeed Marshall in 1991. Bush initially wanted to nominate Thomas to replace William Brennan, who stepped down in 1990, but Bush decided that Thomas had not yet had enough experience as a judge after only months on the federal bench. Bush nominated New Hampshire Supreme Court judge David Souter

David Hackett Souter ( ; born September 17, 1939) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1990 until his retirement in 2009. Appointed by President George H. W. Bush to fill the seat ...

(who is not African-American) instead. When Marshall retired due to health reasons in 1991, Bush nominated Thomas, preserving the racial composition of the court.

On February 25, 2022, President Joe Biden announced the nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson

Ketanji Onyika Brown Jackson ( ; born September 14, 1970) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Jackson was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Joe Biden on February 25, 202 ...

to a seat vacated by the retirement of Stephen Breyer, making Jackson the first African-American woman to be nominated to the court. The Senate confirmed Jackson on April 7, 2022.

Hispanic and Latino justices

The words "

The words "Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

" and "Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties forme ...

" are sometimes given distinct meanings, with "Latino" referring to persons of Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

n descent, and "Hispanic" referring to persons having an ancestry, language or culture traceable to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

or to the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

as a whole, as well as to persons of Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

n descent, whereas the term "Lusitanic

Lusitanic is a term used to refer to people who share the linguistic and cultural traditions of the Portuguese-speaking nations, territories, and populations, including Portugal, Brazil, Madeira, Macau, Timor-Leste, Azores, Angola, Mozambique ...

" usually refers to persons having an ancestry, language or culture traceable to Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

specifically.

Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

– nominated by President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

on May 26, 2009, and sworn in on August 8 – is the first Supreme Court Justice of Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

n descent. Born in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

of Puerto Rican parents, she has been known to refer to herself as a "Nuyorican

Nuyorican is a portmanteau of the terms "New York" and "Puerto Rican" and refers to the members or culture of the Puerto Ricans located in or around New York City, or of their descendants (especially those raised or currently living in the N ...

". Sotomayor is also generally regarded as the first Hispanic justice, although some sources claim that this distinction belongs to former Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo

Benjamin Nathan Cardozo (May 24, 1870 – July 9, 1938) was an American lawyer and jurist who served on the New York Court of Appeals from 1914 to 1932 and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1932 until his deat ...

.

It has been claimed that "only since the George H. W. Bush administration have Hispanic candidates received serious consideration from presidents in the selection process", and that Emilio M. Garza (considered for the vacancy eventually given to Clarence Thomas

Clarence Thomas (born June 23, 1948) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George H. W. Bush to succeed Thurgood Marshall and has served since 1 ...

Dowd, Maureen"The Supreme Court; Conservative black judge, Clarence Thomas, is named to Marshall's court seat"

, ''The New York Times'', July 2, 1991.) was the first Hispanic judge for whom such an appointment was contemplated. Subsequently,

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

was reported by several sources to have considered José A. Cabranes for a Supreme Court nomination on both occasions when a court vacancy opened during the Clinton presidency. The possibility of an Hispanic justice returned during the George W. Bush Presidency, with various reports suggesting that Emilio M. Garza,Kirkpatrick, David DSenate Democrats Are Shifting Focus From Roberts to Other Seat

, ''The New York Times'', September 9, 2005. Alberto Gonzales,Specter: Gonzales Not Ready for Supreme Court

, ''Capitol Hill Blue'', September 12, 2005. and Consuelo M. Callahan were under consideration for the vacancy left by the retirement of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor's seat eventually went to Samuel Alito, however. Speculation about a Hispanic nomination arose again after the election of

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

. In 2009, Obama appointed Sonia Sotomayor, a woman of Puerto Rica

Puerto, a Spanish word meaning ''seaport'', may refer to:

Places

*El Puerto de Santa María, Andalusia, Spain

*Puerto, a seaport town in Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines

*Puerto Colombia, Colombia

*Puerto Cumarebo, Venezuela

*Puerto Galera, Orient ...

n descent, to be the first unequivocally Hispanic Justice. Both the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials and the Hispanic National Bar Association count Sotomayor as the first Hispanic justice. In 2020, President Trump included Cuban-American

Cuban Americans ( es, cubanoestadounidenses or ''cubanoamericanos'') are Americans who trace their cultural heritage to Cuba regardless of phenotype or ethnic origin. The word may refer to someone born in the United States of Cuban descent or ...

judge Barbara Lagoa on a list of potential nominees to the court, and Lagoa was reported to be one of several front-runners to fill the vacancy created by the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Ultimately, Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. ...

was nominated.

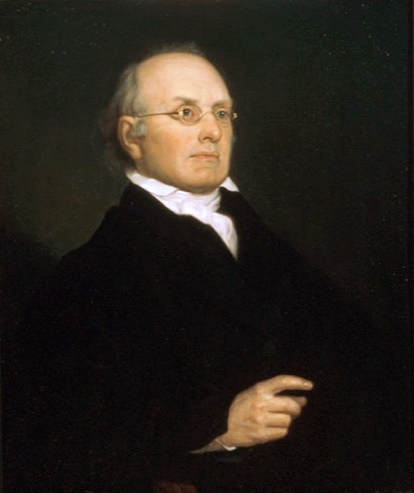

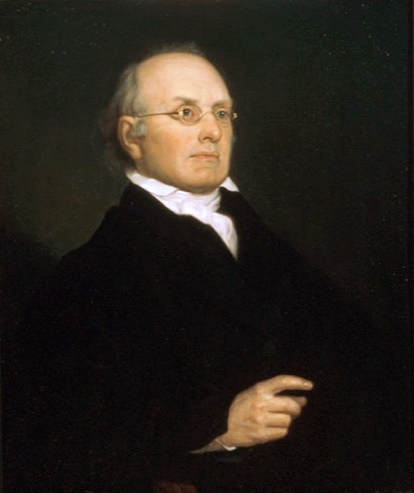

Some historians contend that Cardozo – a Sephardic Jew

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

believed to be of distant Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

descent – should also be counted as the first Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties forme ...

Justice. Schmidhauser wrote in 1979 that "among the large ethnic groupings of European origin which have never been represented upon the Supreme Court are the Italians, Southern Slavs, and Hispanic Americans." The National Hispanic Center for Advanced Studies and Policy Analysis wrote in 1982 that the Supreme Court "has never had an Hispanic Justice", and the ''Hispanic American Almanac'' similarly reported in 1996 that "no Hispanic has yet sat on the U.S. Supreme Court". However, Segal and Spaeth state: "Though it is often claimed that no Hispanics have served on the Court, it is not clear why Benjamin Cardozo, a Sephardic Jew of Spanish heritage, should not count." They identify a number of other sources that present conflicting views as to Cardozo's ethnicity, with one simply labeling him "Iberian." In 2007, the ''Dictionary of Latino Civil Rights History'' also listed Cardozo as "the first Hispanic named to the Supreme Court of the United States."F. Arturo Rosales, ''The Dictionary of Latino Civil Rights History'', Arte Publico Press (February 28, 2007). p 59

The nomination of Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

, widely described in media accounts as the first Hispanic nominee, drew more attention to the question of Cardozo's ethnicity. Cardozo biographer Andrew Kaufman questioned the usage of the term "hispanic" during Cardozo's lifetime, commenting: "Well, I think he regarded himself as Sephardic Jew whose ancestors came from the Iberian Peninsula." However, "no one has ever firmly established that the family's roots were, in fact, in Portugal". It has also been asserted that Cardozo himself "confessed in 1937 that his family preserved neither the Spanish language nor Iberian cultural traditions". By contrast, Cardozo made his own translations of authoritative legal works written in French and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

.

Asian and other ethnic groups

Asian-American jurists are poorly represented at all levels of federal judicial system, let alone being Supreme Court justices. According to the Center for American Progress (2019), among active federal judges serving on U.S. courts of appeals, only 10 were Asian Americans (5.7 percent). According to the study by the California JusticeGoodwin Liu

Goodwin Hon Liu (born October 19, 1970; Chinese: 劉弘威) is an American lawyer, educator and an associate justice of the Supreme Court of California. Before his appointment by California Governor Jerry Brown, Liu was Associate Dean and Profes ...

(2017), of the 94 U.S. attorneys, only three are Asian American; and only 4 of the 2,437 elected prosecutors are Asian American.

Public opinion on ethnic diversity

Public opinion about ethnic diversity on the court "varies widely depending on the poll question's wording". For example, in two polls taken in 1991, one resulted in half of respondents agreeing that it was "important that there always be at least one black person" on the court while the other had only 20 percent agreeing with that sentiment, and with 77 percent agreeing that "race should never be a factor in choosing Supreme Court justices".Gender

Of the 116 justices, 110 (94.8 percent) have been men. All Supreme Court justices were males until 1981, when Ronald Reagan fulfilled his 1980 campaign promise to place a woman on the court, which he did with the appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor was later joined on the court by

Of the 116 justices, 110 (94.8 percent) have been men. All Supreme Court justices were males until 1981, when Ronald Reagan fulfilled his 1980 campaign promise to place a woman on the court, which he did with the appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor. O'Connor was later joined on the court by Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg ( ; ; March 15, 1933September 18, 2020) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1993 until her death in 2020. She was nominated by Presiden ...

, appointed by Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

in 1993. After O'Connor retired in 2006, Ginsburg was joined by Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

and Elena Kagan, who were successfully appointed to the court in 2009 and 2010, respectively, by Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

. In September 2020, following Ginsburg's death, Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

nominated Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. ...

to succeed her. Barrett was confirmed the following month. Only one woman, Harriet Miers

Harriet Ellan Miers (born August 10, 1945) is an American lawyer who served as White House Counsel to President George W. Bush from 2005 to 2007. A member of the Republican Party since 1988, she previously served as White House Staff Secretary f ...

, has been nominated to the court unsuccessfully. Her nomination to succeed O'Connor by George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

was withdrawn under fire from both parties, and also marked the first time when a woman was nominated to replace another woman on the court. The nomination of Barrett was the first successful nomination for a woman to succeed another woman. Joe Biden's 2022 nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson

Ketanji Onyika Brown Jackson ( ; born September 14, 1970) is an American jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Jackson was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Joe Biden on February 25, 202 ...

to a seat vacated by the retirement of Stephen Breyer makes Jackson the first African-American woman to be nominated to the court. The Senate confirmed Jackson on April 7, 2022.

Substantial public sentiment in support of appointment of a woman to the Supreme Court has been expressed since at least as early as 1930, when an editorial in ''The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles in electronic format as well as a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 as a daily newspaper ...

'' encouraged Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

to consider Ohio justice Florence E. Allen or assistant attorney general Mabel Walker Willebrandt. Franklin Delano Roosevelt later appointed Allen to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (in case citations, 6th Cir.) is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:

* Eastern District of Kentucky

* Western District of ...

—making her "one of the highest ranking female jurists in the world at that time". However, neither Roosevelt nor his successors over the following two decades gave strong consideration to female candidates for the court. Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

considered such an appointment but was dissuaded by concerns raised by justices then serving that a woman on the court "would inhibit their conference deliberations", which were marked by informality.

President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

named Mildred Lillie

Mildred Loree Lillie (January 25, 1915 – October 27, 2002) was an American jurist. She served as a judge for 55 years in the state of California with a career that spanned from 1947 until her death in 2002. In 1958, she became the second woman t ...

, then serving on the Second District Court of Appeal of California, as a potential nominee to fill one of two vacancies on the court in 1971. However, Lillie was quickly deemed unqualified by the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

, and no formal proceedings were ever set with respect to her potential nomination. Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

were then successfully nominated to fill those vacancies.

In 1991, a poll found that 53 percent of Americans felt it "important that there always be at least one woman" on the court. However, when O'Connor stepped down from the court, leaving Justice Ginsburg as the lone remaining woman, only one in seven persons polled found it "essential that a woman be nominated to replace" O'Connor.

Graphical timeline of female justices:

Marital status and sexual orientation

Marital status

All but a handful of Supreme Court justices have been married. William H. Moody,Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

, Benjamin Cardozo

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's th ...

, and James Clark McReynolds

James Clark McReynolds (February 3, 1862 – August 24, 1946) was an American lawyer and judge from Tennessee who served as United States Attorney General under President Woodrow Wilson and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the Unite ...

were all lifelong bachelors. In addition, retired justice David Souter

David Hackett Souter ( ; born September 17, 1939) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1990 until his retirement in 2009. Appointed by President George H. W. Bush to fill the seat ...

and current justice Elena Kagan have never been married.Lisa Belkin,Judging Women

", ''

The New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine supplement included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. ...

'' (May 18, 2010). William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

was the first Justice to divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

while on the court and also had the most marriages of any Justice, with four. Justice John Paul Stevens divorced his first wife in 1979, marrying his second wife later that year. Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

was the first female justice to be appointed as an unmarried woman, having divorced in 1983, long before her nomination in 2009. Of the six women who have been appointed to the Court, O'Connor and Ginsburg were the only two military spouses, both having accompanied their spouses to their service posts, though in both cases their spouses had served for only brief periods, decades prior to their appointments.

Several justices have become widowers while on the bench. The 1792 death of Elizabeth Rutledge, wife of Justice John Rutledge, contributed to the mental health problems that led to the rejection of his recess appointment. Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

survived his wife, Anne, by twenty years. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. resolutely continued working on the court for several years after the death of his wife. William Rehnquist was a widower for the last fourteen years of his service on the court, his wife Natalie having died on October 17, 1991 after suffering from ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer is a cancerous tumor of an ovary. It may originate from the ovary itself or more commonly from communicating nearby structures such as fallopian tubes or the inner lining of the abdomen. The ovary is made up of three different c ...

. With the death of Martin D. Ginsburg in June 2010, Ruth Bader Ginsburg became the first woman to be widowed while serving on the court.

Sexual orientation

With regard tosexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

, no Supreme Court justice has identified themself as anything other than heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" ...

, and no incontrovertible evidence of a justice having any other sexual orientation has ever been uncovered. However, the personal lives of several justices and nominees have attracted speculation.

G. Harrold Carswell was unsuccessfully nominated by Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

in 1970 and was convicted in 1976 of battery for making an "unnatural and lascivious" advance to a male police officer working undercover in a Florida men's room. Some therefore claim him as the only gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

or bisexual person nominated to the court thus far. Stating of Carswell, "He's the only known homosexual to have been nominated to the Supreme Court, though he was in the closet". If so, it is unlikely that Nixon was aware of it; White House Counsel

The White House counsel is a senior staff appointee of the president of the United States whose role is to advise the president on all legal issues concerning the president and their administration. The White House counsel also oversees the Of ...

John Dean

John Wesley Dean III (born October 14, 1938) is an American former attorney who served as White House Counsel for U.S. President Richard Nixon from July 1970 until April 1973. Dean is known for his role in the cover-up of the Watergate scandal ...

later wrote of Carswell that " ile Richard Nixon was always looking for historical firsts, nominating a homosexual to the high court would not have been on his list".

Speculation has been recorded about the sexual orientation of a few justices who were lifelong bachelors, but no unambiguous evidence exists that they were gay. Perhaps the greatest body of circumstantial evidence surrounds Frank Murphy

William Francis Murphy (April 13, 1890July 19, 1949) was an American politician, lawyer and jurist from Michigan. He was a Democrat who was named to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1940 after a political career that included serving ...

, who was dogged by "rumors of homosexuality ... all his adult life".

For more than 40 years, Edward G. Kemp was Frank Murphy's devoted, trusted companion. Like Murphy, Kemp was a lifelong bachelor. From college until Murphy's death, the pair found creative ways to work and live together. ..When Murphy appeared to have the better future in politics, Kemp stepped into a supportive, secondary role.As well as Murphy's close relationship with Kemp, Murphy's biographer, historian Sidney Fine, found in Murphy's personal papers a letter that "if the words mean what they say, refers to a homosexual encounter some years earlier between Murphy and the writer." However, the letter's veracity cannot be confirmed, and a review of all the evidence led Fine to conclude that he "could not stick his neck out and say urphywas gay". Speculation has also surrounded

Benjamin Cardozo

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's th ...