Democratic Party presidential primaries, 1924 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From March 12 to June 7, 1924, voters of the

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like

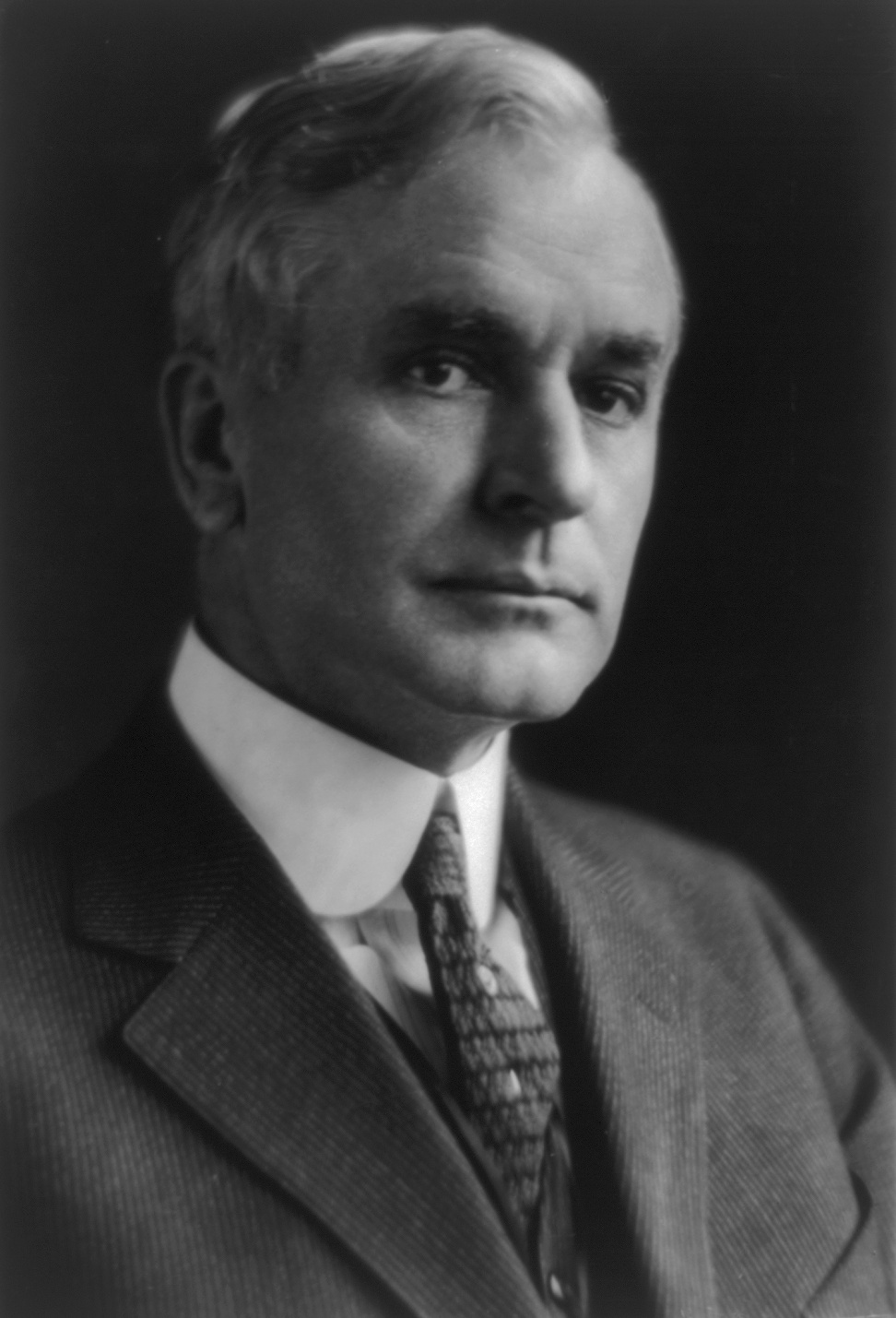

Image:John William Davis.jpg,

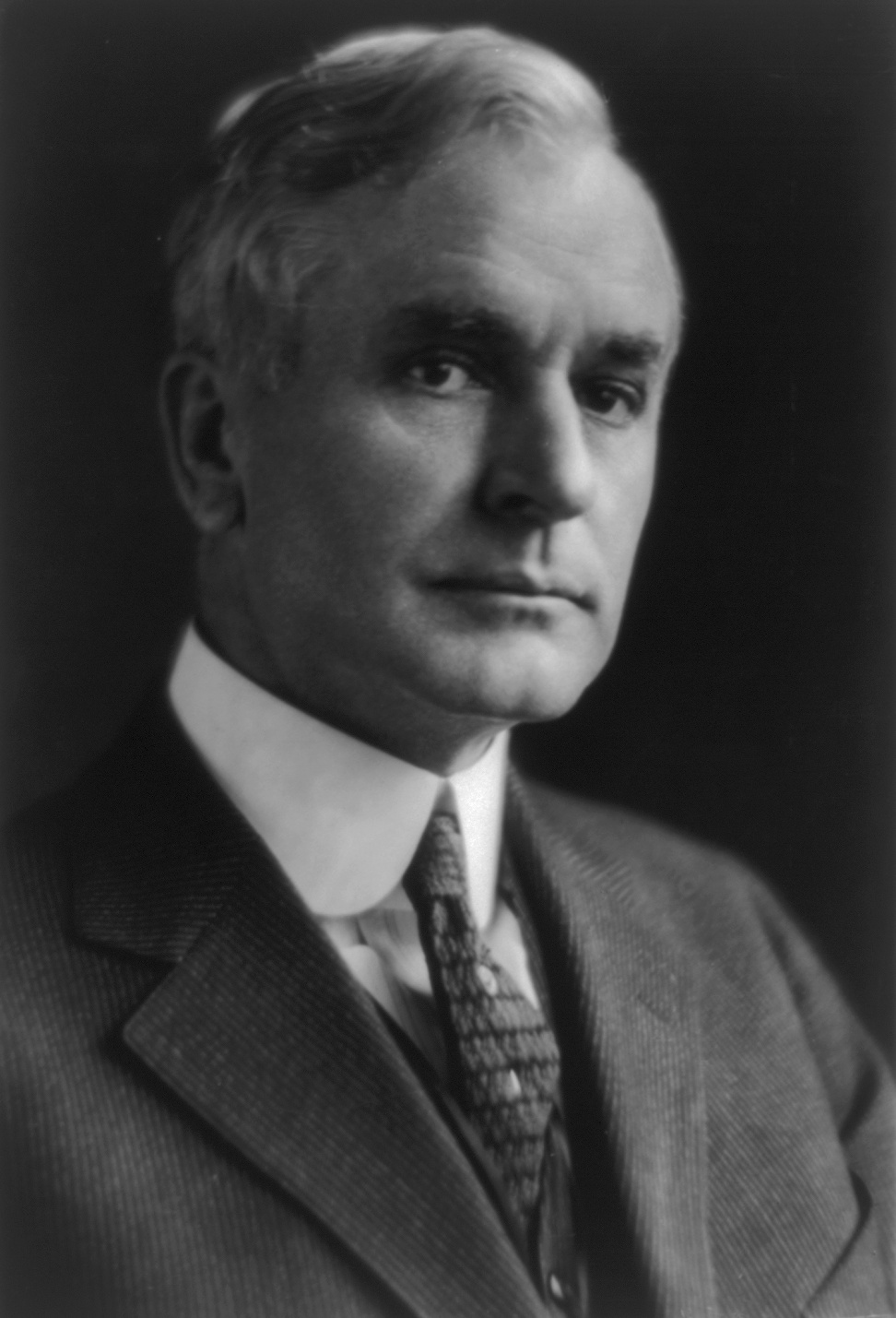

Image:William Gibbs McAdoo, formal photo portrait, 1914.jpg,

Image:AlfredSmith.png,

Image:Oscar W. Underwood.jpg,

McAdoo's connection to Dohney appeared to lessen his desirability seriously as a presidential candidate. In February, Colonel

McAdoo's connection to Dohney appeared to lessen his desirability seriously as a presidential candidate. In February, Colonel

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind that no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. However, to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population, most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party.

Now in the ostensibly-neutral hands of

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind that no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. However, to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population, most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party.

Now in the ostensibly-neutral hands of

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

chose its nominee for president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

in the 1924 United States presidential election

The 1924 United States presidential election was the 35th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 4, 1924. In a three-way contest, incumbent Republican President Calvin Coolidge won election to a full term.

Coolidge had bee ...

. The concept of a primary election

Primary elections, or direct primary are a voting process by which voters can indicate their preference for their party's candidate, or a candidate in general, in an upcoming general election, local election, or by-election. Depending on the ...

, where any registered party member would vote for a candidate, was relatively new in the American political landscape. In only 12 states were actual primaries held, and even in those the results were not universally binding for the delegates to the Democratic National Convention, where the presidential candidate would be formally chosen. In most of the country, the selection of delegates was confined to state-level conventions and caucuses, under the heavy hand of local political machine

In the politics of Representative democracy, representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a hig ...

s.

Though William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

won a vast majority of states, and almost three-fifths of the popular vote, in those twelve states that held primary elections, it meant little to his performance nationwide. Many of the delegations from states that did ''not'' hold primary elections favored his main rivals, Oscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood (May 6, 1862 – January 25, 1929) was an American lawyer and politician from Alabama, and also a candidate for President of the United States in 1912 and 1924. He was the first formally designated floor leader in the Unite ...

of Alabama and Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

of New York, neither of which won any primary elections. As well, the primaries that McAdoo did not win were won by "local sons" who stood no chance of winning the nomination, or in some cases were not even formal candidates. Once at the convention, the party was deadlocked for 102 straight ballots, before dark horse candidate

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, or a contestant that on paper should be unlikely to succeed but yet still might.

Origin

Th ...

John W. Davis

John William Davis (April 13, 1873 – March 24, 1955) was an American politician, diplomat and lawyer. He served under President Woodrow Wilson as the Solicitor General of the United States and the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom ...

, (who was not a formal candidate when he arrived at the convention) was chosen on the 103rd ballot. Davis went on to lose the election to Republican candidate Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

.

Background

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like

Sizable Democratic gains during the 1922 Midterm elections suggested to many Democrats that the nadir they experienced immediately following the 1920 elections was ending, and that a popular candidate like William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

of California, who could draw the popular support of labor and Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and p ...

s, would stand an excellent chance of winning the coming presidential election. The Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomin ...

added yet even more enthusiasm for party initially, though further disclosures revealed that the corrupt interests had been bipartisan; Edward Doheny

Edward Laurence Doheny (; August 10, 1856 – September 8, 1935) was an American oil tycoon who, in 1892, drilled the first successful oil well in the Los Angeles City Oil Field. His success set off a petroleum boom in Southern California, a ...

for example, whose name had become synonymous with that of the Teapot Dome scandal, ranked highly in the Democratic party of California, contributing highly to party campaigns, served as chairman of the state party, and was even at one point advanced as a possible candidate for vice-president in 1920. The death of Warren Harding in August 1923 and the succession of Coolidge blunted the effects of the scandals upon the Republican party, including that of Teapot Dome, but up until and into the convention many Democrats believed that the Republicans would be turned out of the White House.History of American Presidential Elections 1789–1968; Arthur M. Schlesinger, jr.; Pgs 2460–2461

Candidates

There were four candidates:McAdoo, the frontrunner

The party's immediate leading candidate of the 60-year-oldWilliam Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

, who was extremely popular with labor thanks to his wartime record as Director General of the railroads and was, as former Wilson's son-in-law, also the favorite of the Wilsonians. However, in January 1924, unearthed evidence of his relationship with Doheny discomforted many of his supporters. After McAdoo had resigned from the Wilson administration

Woodrow Wilson's tenure as the 28th president of the United States lasted from 4 March 1913 until 4 March 1921. He was largely incapacitated the last year and a half. He became president after winning the 1912 election. Wilson was a Democrat ...

in 1918, Joseph Tumulty, Wilson's secretary, had warned him to avoid association with Doheny. However, in 1919, McAdoo took Doheny as a client for an unusually large initial fee of $100,000 in addition to an annual retainer. Not the least perplexing part of the deal involved a million dollar bonus for McAdoo if the Mexican government reached a satisfactory agreement with Washington on oil lands Doheny held south of the Texas border. The bonus was never paid, and McAdoo later insisted that it was a casual figure of speech mentioned in jest. At the time, however, he had telegraphed the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

'' that he would have received "an additional fee of $900,000 if my firm had succeeded in getting a satisfactory settlement" since the Doheny companies had "several hundred million dollars of property at stake, our services, had they been effective, would have been rightly compensated by the additional fee." In fact, the lawyer received only $50,000 more from Doheny.

It was also charged that on matters of interest to his client, Republic Iron and Steel, from which he received $150,000, McAdoo neglected the regular channels dictated by propriety and consulted directly with his own appointees in the capital to obtain a fat refund.

McAdoo's connection to Dohney appeared to lessen his desirability seriously as a presidential candidate. In February, Colonel

McAdoo's connection to Dohney appeared to lessen his desirability seriously as a presidential candidate. In February, Colonel Edward M. House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

urged him to withdraw from the race, as did Josephus Daniels

Josephus Daniels (May 18, 1862 – January 15, 1948) was an American newspaper editor and publisher from the 1880s until his death, who controlled Raleigh's ''News & Observer'', at the time North Carolina's largest newspaper, for decades. A D ...

, Thomas Bell Love, and two important contributors to the Democratic party, Bernard Baruch

Bernard Mannes Baruch (August 19, 1870 – June 20, 1965) was an American financier and statesman.

After amassing a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange, he impressed President Woodrow Wilson by managing the nation's economic mobilization in ...

and Thomas Chadbourne. Some advisers hoped that McAdoo's chances would improve after a formal withdrawal. William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

, who never doubted McAdoo's honesty, thought that the Doheny affair had damaged the lawyer's chances "seriously, if not fatally." Senator Thomas Walsh, who earlier had called McAdoo the greatest Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

, informed him with customary curtness: "You are no longer available as a candidate." Breckinridge Long

Samuel Miller Breckinridge Long (May 16, 1881 – September 26, 1958) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in the administrations of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He is infamous among Holocaust historians for makin ...

, who would be McAdoo's floor manager at the June convention, wrote in his diary on February 13: "As it stands today we are beat." ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', itself convinced that McAdoo had acted in bad taste and against the spirit of the law, report the widespread opinion that McAdoo had "been eliminated as a formidable contender for Democratic nomination."

McAdoo was unpopular for reasons other than his close association with Doheny. Even in 1918, ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' was saying that "his election to the White House would be an unqualified misfortune." McAdoo, the liberal journal then believed, had wanted to go to war with Mexico and Germany and he was held responsible for segregating clerks in the Treasury Department. Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

wrote in 1920 that McAdoo "is not fundamentally moved by the simple moralities" and that his "honest" liberalism catered only to popular feeling. Liberal critics, believing him a demagogue, gave as evidence his stand for quick payment of the veterans' bonus.

Relations with the Klan

Much of the dissatisfaction with McAdoo on the part of reformers and urban Democrats sprang from his acceptance of the backing of theKu Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

. James Cox, the 1920 Democratic nominee, indignantly wrote that "there was not only tacit consent to the Klan's support, but it was apparent that he and his major supporters were conniving with the Klan." Friends insisted that McAdoo's silence on the matter hid a distaste that the political facts of life kept him from expressing, especially after the Doheny scandal when he desperately needed support. Thomas Bell Love of Texas, though at one time of a contrary opinion, advised McAdoo not to issue even a mild disclaimer of the Klan. To Bernard Baruch and others, McAdoo explained as a disavowal of the Klan his remarks against prejudice at a 1923 college commencement. However, McAdoo could not command the support of unsatisfied liberal spokesmen for ''The Nation'' and ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hum ...

'', which favored the candidacy of the Republican Senator Robert LaFollette. A further blow to McAdoo was the death on February 3, 1924, of Wilson, who had ironically outlived his successor in the White House. Father-in-law to the candidate, Wilson might have given McAdoo a welcome endorsement now that the League of Nations had receded as an issue.

William Dodd of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

wrote to his father that Wilson had been "counting on" his daughter's being in the White House. ''The New York Times'', however, reported a rumor that Wilson had written to Cox hoping he would again be a candidate in 1924.

McAdoo vs. Underwood

Those handicaps did not deter McAdoo from campaigning vigorously and effectively in presidential primaries. He won easily against minor candidates, whose success might have denied him key delegations in the South and the West, but SenatorOscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood (May 6, 1862 – January 25, 1929) was an American lawyer and politician from Alabama, and also a candidate for President of the United States in 1912 and 1924. He was the first formally designated floor leader in the Unite ...

of Alabama was no match for McAdoo. Opposed to Prohibition and to the Klan, Underwood failed to identify himself with the kind of progressivism that would have won him some compensating support. Underwood ‘s candidacy also suffered from a view that he was not a “real southerner” since he had been born in Kentucky, and his father had served as a colonel in the Union Army. "He is a New York candidate living in the South," said William Jennings Bryan. McAdoo defeated Underwood in Georgia and even split the Alabama delegation. Whatever appeal that Underwood had outside of the South was erased by the emerging candidacy of Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

.

McAdoo vs. Smith

In their immediate effects, the heated primary contests drew to McAdoo the financial support of the millionaires Thomas Chadbourne and Bernard Baruch, who was indebted to McAdoo for his appointment as head of the War Industries Board, and they strengthened the resolve of Governor Smith, ten years younger than McAdoo, to make a serious try for the nomination, which he had originally sought primarily to block McAdoo on the behalf of the eastern political bosses. The contests also hardened the antagonisms between the candidates and cut deeper divisions within the electorate. In doing so, they undoubtedly retrieved lost ground for McAdoo and broadened his previously-shrinking base of support, drawing to him rural, Klan, and dry elements awakened by the invigorated candidacy of Smith. Senator Kenneth McKellar of Tennessee wrote to his sister Nellie: "I see McAdoo carried Georgia by such an overwhelming majority that it is likely to reinstate him in the running." The Klan seemed to oppose every Democratic candidate except McAdoo. A Klan newspaper rejectedHenry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

because he had given a Lincoln car to a Catholic archbishop, flatly rejected Smith as a Catholic from "Jew York," and it called Underwood the "Jew, jug, Jesuit candidate." The primaries, therefore played, their part in crystallizing the split within the party that would tear it apart at the forthcoming convention.

City immigrants and McAdoo progressives had earlier joined to fight the Mellon tax plans in Congress since both groups represented people of small means. Deeper social animosities dissolved their alliance, and the urban-rural division rapidly supplanted all others. Frank Walsh

Francis Henry Walsh (6 July 1897 – 18 May 1968) was the 34th Premier of South Australia from 10 March 1965 to 1 June 1967, representing the South Australian Branch of the Australian Labor Party.

Early life

One of eight children, Walsh was b ...

, a progressive New York lawyer, wrote: "If his mith'sreligion is a bar, of course it is all right with me to bust up the Democratic party on such an issue."

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind that no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. However, to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population, most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party.

Now in the ostensibly-neutral hands of

More directly, the contest between McAdoo and Smith thrust upon the Democratic national convention a dilemma of a kind that no politician would wish to confront. To reject McAdoo and nominate Smith would solidify anti-Catholic feeling and rob the party of millions of otherwise certain votes in the South and elsewhere. However, to reject Smith and nominate McAdoo would antagonize American Catholics, who constituted some 16 percent of the population, most of whom could normally be counted upon by the Democrats. Either selection would affect significantly the future of the party.

Now in the ostensibly-neutral hands of Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

, the chairman of the Democratic National Convention, party machinery was expected to shift to the victor during the convention, and a respectable run in the fall election would insure the victor's continued supremacy in Democratic politics.

Despite the strong showing by McAdoo in the primaries, an argument could be made for the political wisdom of a Smith ticket. In the 1922 congressional elections, the largest gains had come in New York, New Jersey, and other urban areas where Roman Catholicism was strong. The new strength of the party, those elections seemed to indicate, lay not in the traditionalist countryside of Bryan and McAdoo but in the tenement areas of the city and the regions of rapid industrialization.

Also, as Franklin Roosevelt wrote to Josephus Daniels, Smith's followers came from states with big electoral votes that then often swung a presidential election: Massachusetts, New York, and Illinois. However, the strain of anti-Catholicism in America was a threat of proportions that could not be easily calculated.

Nevertheless, no one had gotten anywhere near the two thirds needed to win at the convention in New York.

See also

* Republican Party presidential primaries, 1924 *White primary

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South C ...

References

{{United States presidential election, 1924