Decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

For most of its history ancient Egypt had two major writing systems.

For most of its history ancient Egypt had two major writing systems.

Arab scholars were aware of the connection between Coptic and the ancient Egyptian language, and Coptic monks in Islamic times were sometimes believed to understand the ancient scripts. Several Arab scholars in the seventh through fourteenth centuries, including

Arab scholars were aware of the connection between Coptic and the ancient Egyptian language, and Coptic monks in Islamic times were sometimes believed to understand the ancient scripts. Several Arab scholars in the seventh through fourteenth centuries, including

During the

During the

Hardly anyone attempted to decipher hieroglyphs for decades after Kircher's last works on the subject, although some contributed suggestions about the script that ultimately proved correct.

Hardly anyone attempted to decipher hieroglyphs for decades after Kircher's last works on the subject, although some contributed suggestions about the script that ultimately proved correct.

When French forces under

When French forces under

Young was a British

Young was a British

Over the next few months Champollion applied his hieroglyphic alphabet to many Egyptian inscriptions, identifying dozens of royal names and titles. During this period Champollion and the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin examined the

Over the next few months Champollion applied his hieroglyphic alphabet to many Egyptian inscriptions, identifying dozens of royal names and titles. During this period Champollion and the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin examined the

The

The writing system

A writing system is a method of visually representing verbal communication, based on a script and a set of rules regulating its use. While both writing and speech are useful in conveying messages, writing differs in also being a reliable fo ...

s used in ancient Egypt were deciphered in the early nineteenth century through the work of several European scholars, especially Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion (), also known as Champollion ''le jeune'' ('the Younger'; 23 December 17904 March 1832), was a French philologist and orientalist, known primarily as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs and a founding figure in t ...

and Thomas Young. Ancient Egyptian forms of writing, which included the hieroglyphic

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

, hieratic

Hieratic (; grc, ἱερατικά, hieratiká, priestly) is the name given to a cursive writing system used for Ancient Egyptian and the principal script used to write that language from its development in the third millennium BC until the ris ...

and demotic

Demotic may refer to:

* Demotic Greek, the modern vernacular form of the Greek language

* Demotic (Egyptian), an ancient Egyptian script and version of the language

* Chữ Nôm, the demotic script for writing Vietnamese

See also

*

* Demos (disa ...

scripts, ceased to be understood in the fourth and fifth centuries AD, as the Coptic alphabet

The Coptic alphabet is the script used for writing the Coptic language. The repertoire of glyphs is based on the Greek alphabet augmented by letters borrowed from the Egyptian Demotic and is the first alphabetic script used for the Egyptian ...

was increasingly used in their place. Later generations' knowledge of the older scripts was based on the work of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

authors whose understanding was faulty. It was thus widely believed that Egyptian scripts were exclusively ideographic

An ideogram or ideograph (from Greek "idea" and "to write") is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language, and specific words or phrases. Some ideograms are comprehensible only by familiari ...

, representing ideas rather than sounds, and even that hieroglyphs were an esoteric, mystical script rather than a means of recording a spoken language. Some attempts at decipherment by Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ma ...

and European scholars in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

and early modern times acknowledged the script might have a phonetic

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

component, but perception of hieroglyphs as purely ideographic hampered efforts to understand them as late as the eighteenth century.

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Anci ...

, discovered in 1799 by members of Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in Egypt, bore a parallel text

A parallel text is a text placed alongside its translation or translations. Parallel text alignment is the identification of the corresponding sentences in both halves of the parallel text. The Loeb Classical Library and the Clay Sanskrit Libr ...

in hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. It was hoped that the Egyptian text could be deciphered through its Greek translation, especially in combination with the evidence from the Coptic language

Coptic (Bohairic Coptic: , ) is a language family of closely related dialects, representing the most recent developments of the Egyptian language, and historically spoken by the Copts, starting from the third-century AD in Roman Egypt. Copti ...

, the last stage of the Egyptian language

The Egyptian language or Ancient Egyptian ( ) is a dead Afro-Asiatic language that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts which were made accessible to the modern world following the deciphe ...

. Doing so proved difficult, despite halting progress made by Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy

Antoine Isaac, Baron Silvestre de Sacy (; 21 September 175821 February 1838), was a French nobleman, linguist and orientalist. His son, Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy, became a journalist.

Life and works

Early life

Silvestre de Sacy was born in Pa ...

and Johan David Åkerblad

Johan David Åkerblad (6 May 1763, Stockholm – 7 February 1819, Rome) was a Swedish diplomat and orientalist.

Career

In 1778 he began his studies of classical and oriental languages at the University of Uppsala. In 1782 he defended his gr ...

. Young, building on their work, observed that demotic characters were derived from hieroglyphs and identified several of the phonetic signs in demotic. He also identified the meaning of many hieroglyphs, including phonetic glyphs

A glyph () is any kind of purposeful mark. In typography, a glyph is "the specific shape, design, or representation of a character". It is a particular graphical representation, in a particular typeface, of an element of written language. A g ...

in a cartouche

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, a cartouche is an oval with a line at one end tangent to it, indicating that the text enclosed is a royal name. The first examples of the cartouche are associated with pharaohs at the end of the Third Dynasty, but the f ...

containing the name of an Egyptian king of foreign origin, Ptolemy V

egy, Iwaennetjerwymerwyitu Seteppah Userkare Sekhem-ankhamun Clayton (2006) p. 208.

, predecessor = Ptolemy IV

, successor = Ptolemy VI

, horus = '' ḥwnw-ḫꜤj-m-nsw-ḥr-st-jt.f'Khunukhaiemnisutkhersetitef'' The youth who ...

. He was convinced, however, that phonetic hieroglyphs were used only in writing non-Egyptian words. In the early 1820s Champollion compared Ptolemy's cartouche with others and realised the hieroglyphic script was a mixture of phonetic and ideographic elements. His claims were initially met with scepticism and with accusations that he had taken ideas from Young without giving credit, but they gradually gained acceptance. Champollion went on to roughly identify the meanings of most phonetic hieroglyphs and establish much of the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Egyptian. Young, meanwhile, largely deciphered demotic using the Rosetta Stone in combination with other Greek and demotic parallel texts.

Decipherment efforts languished after Young's death in 1829 and Champollion's in 1832, but in 1837 Karl Richard Lepsius

Karl Richard Lepsius ( la, Carolus Richardius Lepsius) (23 December 181010 July 1884) was a pioneering Prussian Egyptologist, linguist and modern archaeologist.

He is widely known for his magnum opus '' Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopie ...

pointed out that many hieroglyphs represented combinations of two or three sounds rather than one, thus correcting one of the most fundamental faults in Champollion's work. Other scholars, such as Emmanuel de Rougé

''Vicomte'' Olivier Charles Camille Emmanuel de Rouge (11 April 1811 – 27 December 1872) was a French Egyptologist, philologist and a member of the House of Rougé.

Biography

He was born on 11 April 1811, in Paris, the son of Charles Camil ...

, refined the understanding of Egyptian enough that by the 1850s it was possible to fully translate ancient Egyptian texts. Combined with the decipherment of cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

at approximately the same time, their work opened up the once-inaccessible texts from the earliest stages of human history.

Egyptian scripts and their extinction

Hieroglyphs

A hieroglyph (Greek for "sacred carvings") was a character of the ancient Egyptian writing system. Logographic scripts that are pictographic in form in a way reminiscent of ancient Egyptian are also sometimes called "hieroglyphs". In Neoplatonis ...

, a system of pictorial signs used mainly for formal texts, originated sometime around 3200BC. Hieratic

Hieratic (; grc, ἱερατικά, hieratiká, priestly) is the name given to a cursive writing system used for Ancient Egyptian and the principal script used to write that language from its development in the third millennium BC until the ris ...

, a cursive

Cursive (also known as script, among other names) is any style of penmanship in which characters are written joined in a flowing manner, generally for the purpose of making writing faster, in contrast to block letters. It varies in functionali ...

system derived from hieroglyphs that was used mainly for writing on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to ...

, was nearly as old. Beginning in the seventh centuryBC, a third script derived from hieratic, known today as demotic

Demotic may refer to:

* Demotic Greek, the modern vernacular form of the Greek language

* Demotic (Egyptian), an ancient Egyptian script and version of the language

* Chữ Nôm, the demotic script for writing Vietnamese

See also

*

* Demos (disa ...

, emerged. It differed so greatly from its hieroglyphic ancestor that the relationship between the signs is difficult to recognise. Demotic became the most common system for writing the Egyptian language

The Egyptian language or Ancient Egyptian ( ) is a dead Afro-Asiatic language that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts which were made accessible to the modern world following the deciphe ...

, and hieroglyphic and hieratic were thereafter mostly restricted to religious uses. In the fourth centuryBC, Egypt came to be ruled by the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; grc, Πτολεμαῖοι, ''Ptolemaioi''), sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty (Λαγίδαι, ''Lagidae;'' after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic ...

, and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and demotic were used side-by-side in Egypt under Ptolemaic rule and then that of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. Hieroglyphs became increasingly obscure, used mainly by Egyptian priests.

All three scripts contained a mix of phonetic signs, representing sounds in the spoken language, and ideographic

An ideogram or ideograph (from Greek "idea" and "to write") is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language, and specific words or phrases. Some ideograms are comprehensible only by familiari ...

signs, representing ideas. Phonetic signs included uniliteral, biliteral and triliteral signs, standing respectively for one, two or three sounds. Ideographic signs included logogram

In a written language, a logogram, logograph, or lexigraph is a written character that represents a word or morpheme. Chinese characters (pronounced '' hanzi'' in Mandarin, ''kanji'' in Japanese, ''hanja'' in Korean) are generally logograms, ...

s, representing whole words, and determinative

A determinative, also known as a taxogram or semagram, is an ideogram used to mark semantic categories of words in logographic scripts which helps to disambiguate interpretation. They have no direct counterpart in spoken language, though they may ...

s, which were used to specify the meaning of a word written with phonetic signs.

Many Greek and Roman authors wrote about these scripts, and many were aware that the Egyptians had two or three writing systems, but none whose works survived into later times fully understood how the scripts worked. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, in the first centuryBC, explicitly described hieroglyphs as an ideographic script, and most classical authors shared this assumption. Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, in the first century AD, referred to 25 Egyptian letters, suggesting he might have been aware of the phonetic aspect of hieroglyphic or demotic, but his meaning is unclear. Around AD200 Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen ...

hinted that some signs were phonetic but concentrated on the signs' metaphorical meanings. Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher wa ...

, in the third century AD, claimed hieroglyphs did not represent words but a divinely inspired, fundamental insight into the nature of the objects they depicted. Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from antiquity (preceding Procopius). His work, known as the ''Res Gestae ...

in the fourth century AD copied another author's translation of a hieroglyphic text on an obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

, but the translation was too loose to be useful in understanding the principles of the writing system. The only extensive discussion of hieroglyphs to survive into modern times was the ''Hieroglyphica Horapollo (from Horus Apollo; grc-gre, Ὡραπόλλων) is the supposed author of a treatise, titled ''Hieroglyphica'', on Egyptian hieroglyphs, extant in a Greek translation by one Philippus, dating to about the 5th century.

Life

Horapollo is ...

'', a work probably written in the fourth century AD and attributed to a man named Horapollo Horapollo (from Horus Apollo; grc-gre, Ὡραπόλλων) is the supposed author of a treatise, titled ''Hieroglyphica'', on Egyptian hieroglyphs, extant in a Greek translation by one Philippus, dating to about the 5th century.

Life

Horapollo is ...

. It discusses the meanings of individual hieroglyphs, though not how those signs were used to form phrases or sentences. Some of the meanings it describes are correct, but more are wrong, and all are misleadingly explained as allegories. For instance, Horapollo says an image of a goose means "son" because geese are said to love their children more than other animals. In fact the goose hieroglyph was used because the Egyptian words for "goose" and "son" incorporated the same consonants.

Both hieroglyphic and demotic began to disappear in the third century AD. The temple-based priesthoods died out and Egypt was gradually converted to Christianity, and because Egyptian Christians

Christianity is the second largest religion in Egypt. The history of Egyptian Christianity dates to the Roman era as Alexandria was an early center of Christianity.

Demographics

The vast majority of Egyptian Christians are Copts who belong t ...

wrote in the Greek-derived Coptic alphabet

The Coptic alphabet is the script used for writing the Coptic language. The repertoire of glyphs is based on the Greek alphabet augmented by letters borrowed from the Egyptian Demotic and is the first alphabetic script used for the Egyptian ...

, it came to supplant demotic. The last hieroglyphic text was written by priests at the Temple of Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

at Philae

; ar, فيلة; cop, ⲡⲓⲗⲁⲕ

, alternate_name =

, image = File:File, Asuán, Egipto, 2022-04-01, DD 93.jpg

, alt =

, caption = The temple of Isis from Philae at its current location on Agilkia Island in Lake Nasse ...

in AD394, and the last demotic text was inscribed there in AD452. Most of history before the first millenniumBC was recorded in Egyptian scripts or in cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge- ...

, the writing system of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

. With the loss of knowledge of both these scripts, the only records of the distant past were in limited and distorted sources. The major Egyptian example of such a source was ''Aegyptiaca

Manetho (; grc-koi, Μανέθων ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos ( cop, Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, translit=Čemnouti) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third ...

'', a history of the country written by an Egyptian priest named Manetho in the third centuryBC. The original text was lost, and it survived only in summaries and quotations by Roman authors.

The Coptic language

Coptic (Bohairic Coptic: , ) is a language family of closely related dialects, representing the most recent developments of the Egyptian language, and historically spoken by the Copts, starting from the third-century AD in Roman Egypt. Copti ...

, the last form of the Egyptian language, continued to be spoken by most Egyptians well after the Arab conquest of Egypt in AD642, but it gradually lost ground to Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

. Coptic began to die out in the twelfth century, and thereafter it survived mainly as the liturgical language

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is any language that is cultivated and used primarily in church service or for other religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

Concept

A sacr ...

of the Coptic Church

The Coptic Orthodox Church ( cop, Ϯⲉⲕ̀ⲕⲗⲏⲥⲓⲁ ⲛ̀ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲣⲑⲟⲇⲟⲝⲟⲥ, translit=Ti.eklyseya en.remenkimi en.orthodoxos, lit=the Egyptian Orthodox Church; ar, الكنيسة القبطي� ...

.

Early efforts

Medieval Islamic world

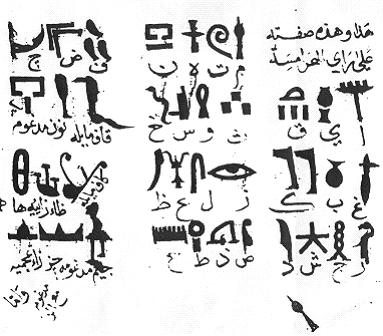

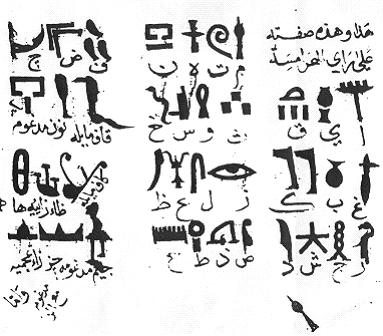

Arab scholars were aware of the connection between Coptic and the ancient Egyptian language, and Coptic monks in Islamic times were sometimes believed to understand the ancient scripts. Several Arab scholars in the seventh through fourteenth centuries, including

Arab scholars were aware of the connection between Coptic and the ancient Egyptian language, and Coptic monks in Islamic times were sometimes believed to understand the ancient scripts. Several Arab scholars in the seventh through fourteenth centuries, including Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

and Ayub ibn Maslama, are said to have understood hieroglyphs, although because their works on the subject have not survived these claims cannot be tested. Dhul-Nun al-Misri

Dhūl-Nūn Abū l-Fayḍ Thawbān b. Ibrāhīm al-Miṣrī ( ar, ذو النون المصري; d. Giza, in 245/859 or 248/862), often referred to as Dhūl-Nūn al-Miṣrī or Zūl-Nūn al-Miṣrī for short, was an early Egyptian Muslim mystic a ...

and Ibn Wahshiyya

( ar, ابن وحشية), died , was a Nabataean (Aramaic-speaking, rural Iraqi) agriculturalist, toxicologist, and alchemist born in Qussīn, near Kufa in Iraq. He is the author of the '' Nabataean Agriculture'' (), an influential Arabic work ...

, in the ninth and tenth centuries, wrote treatises containing dozens of scripts known in the Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

, including hieroglyphs, with tables listing their meanings. In the thirteenth or fourteenth century, Abu al-Qasim al-Iraqi copied an ancient Egyptian text and assigned phonetic values to several hieroglyphs. The Egyptologist Okasha El-Daly has argued that the tables of hieroglyphs in the works of Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu al-Qasim correctly identified the meaning of many of the signs. Other scholars have been sceptical of Ibn Wahshiyya's claims to understand the scripts he wrote about, and Tara Stephan, a scholar of the medieval Islamic world, says El-Daly "vastly overemphasizes Ibn Waḥshiyya's accuracy". Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu al-Qasim did recognise that hieroglyphs could function phonetically as well as symbolically, a point that would not be acknowledged in Europe for centuries.

Fifteenth through seventeenth centuries

During the

During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

Europeans became interested in hieroglyphs, beginning around 1422 when Cristoforo Buondelmonti

Cristoforo Buondelmonti (c. 1385 – c. 1430) was an Italian Franciscan priest and traveler, and a pioneer in promoting first-hand knowledge of Greece and its antiquities throughout the Western world.

Biography

Cristoforo Buondelmonti was born ar ...

discovered a copy of Horapollo's ''Hieroglyphica'' in Greece and brought it to the attention of antiquarians such as Niccolò de' Niccoli

Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364 – 22 January 1437) was an Italian Renaissance humanist.

He was born and died in Florence, and was one of the chief figures in the company of learned men which gathered around the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici. Nic ...

and Poggio Bracciolini

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), usually referred to simply as Poggio Bracciolini, was an Italian scholar and an early Renaissance humanist. He was responsible for rediscovering and recovering many clas ...

. Poggio recognised that there were hieroglyphic texts on obelisks and other Egyptian artefacts imported to Europe in Roman times, but the antiquarians did not attempt to decipher these texts. Influenced by Horapollo and Plotinus, they saw hieroglyphs as a universal, image-based form of communication, not a means of recording a spoken language. From this belief sprang a Renaissance artistic tradition of using obscure symbolism loosely based on the imagery described in Horapollo, pioneered by Francesco Colonna's 1499 book '' Hypnerotomachia Poliphili''.

Europeans were ignorant of Coptic as well. Scholars sometimes obtained Coptic manuscripts, but in the sixteenth century, when they began to seriously study the language, the ability to read it may have been limited to Coptic monks, and no Europeans of the time had the opportunity to learn from one of these monks, who did not travel outside Egypt. Scholars were also unsure whether Coptic was descended from the language of the ancient Egyptians; many thought it was instead related to other languages of the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

.

The first European to make sense of Coptic was a German Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

, Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works, most notably in the fields of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fe ...

, in the mid-seventeenth century. Basing his work on Arabic grammars and dictionaries of Coptic acquired in Egypt by an Italian traveller, Pietro Della Valle

Pietro Della Valle ( la, Petrus a Valle; 2 April 1586 – 21 April 1652), also written Pietro della Valle, was an Italian composer, musicologist, and author who travelled throughout Asia during the Renaissance period. His travels took him to the ...

, Kircher produced flawed but pioneering translations and grammars of the language in the 1630s and 1640s. He guessed that Coptic was derived from the language of the ancient Egyptians, and his work on the subject was preparation for his ultimate goal, decipherment of the hieroglyphic script.

According to the standard biographical dictionary of Egyptology, "Kircher has become, perhaps unfairly, the symbol of all that is absurd and fantastic in the story of the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs". Kircher thought the Egyptians had believed in an ancient theological tradition that preceded and foreshadowed Christianity, and he hoped to understand this tradition through hieroglyphs. Like his Renaissance predecessors, he believed hieroglyphs represented an abstract form of communication rather than a language. To translate such a system of communication in a self-consistent way was impossible. Therefore, in his works on hieroglyphs, such as ''Oedipus Aegyptiacus

''Oedipus Aegyptiacus'' is Athanasius Kircher's supreme work of Egyptology.

The three full folio tomes of ornate illustrations and diagrams were published in Rome over the period 1652–54. Kircher cited as his sources Chaldean astrology, Heb ...

'' (1652–1655), Kircher proceeded by guesswork based on his understanding of ancient Egyptian beliefs, derived from the Coptic texts he had read and from ancient texts that he thought contained traditions derived from Egypt. His translations turned short texts containing only a few hieroglyphic characters into lengthy sentences of esoteric ideas. Unlike earlier European scholars, Kircher did realise that hieroglyphs could function phonetically, though he considered this function a late development. He also recognised one hieroglyph, 𓈗, as representing water and thus standing phonetically for the Coptic word for water, ''mu'', as well as the ''m'' sound. He became the first European to correctly identify a phonetic value for a hieroglyph.

Although Kircher's basic assumptions were shared by his contemporaries, most scholars rejected or even ridiculed his translations. Nevertheless, his argument that Coptic was derived from the ancient Egyptian language was widely accepted.

Eighteenth century

Hardly anyone attempted to decipher hieroglyphs for decades after Kircher's last works on the subject, although some contributed suggestions about the script that ultimately proved correct.

Hardly anyone attempted to decipher hieroglyphs for decades after Kircher's last works on the subject, although some contributed suggestions about the script that ultimately proved correct. William Warburton

William Warburton (24 December 16987 June 1779) was an English writer, literary critic and churchman, Bishop of Gloucester from 1759 until his death. He edited editions of the works of his friend Alexander Pope, and of William Shakespeare.

Li ...

's religious treatise '' The Divine Legation of Moses'', published from 1738 to 1741, included a long digression on hieroglyphs and the evolution of writing. It argued that hieroglyphs were not invented to encode religious secrets but for practical purposes, like any other writing system, and that the phonetic Egyptian script mentioned by Clement of Alexandria was derived from them. Warburton's approach, though purely theoretical, created the framework for understanding hieroglyphs that would dominate scholarship for the rest of the century.

Europeans' contact with Egypt increased during the eighteenth century. More of them visited the country and saw its ancient inscriptions firsthand, and as they collected antiquities, the number of texts available for study increased. Jean-Pierre Rigord became the first European to identify a non-hieroglyphic ancient Egyptian text in 1704, and Bernard de Montfaucon

Dom Bernard de Montfaucon, O.S.B. (; 13 January 1655 – 21 December 1741) was a French Benedictine monk of the Congregation of Saint Maur. He was an astute scholar who founded the discipline of palaeography, as well as being an editor of works ...

published a large collection of such texts in 1724. Anne Claude de Caylus

Anne Claude de Tubières-Grimoard de Pestels de Lévis, ''comte de Caylus'', marquis d'Esternay, baron de Bransac (Anne Claude Philippe; 31 October, 16925 September 1765), was a French antiquarian, proto-archaeologist and man of letters.

Born in ...

collected and published a large number of Egyptian inscriptions from 1752 to 1767, assisted by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy

Jean-Jacques Barthélemy (20 January 1716 – 30 April 1795) was a French scholar who became the first person to decipher an extinct language. He deciphered the Palmyrene alphabet in 1754 and the Phoenician alphabet in 1758.

Early years

Barth� ...

. Their work noted that non-hieroglyphic Egyptian scripts seemed to contain signs derived from hieroglyphs. Barthélemy also pointed out the oval rings, later to be known as cartouche

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, a cartouche is an oval with a line at one end tangent to it, indicating that the text enclosed is a royal name. The first examples of the cartouche are associated with pharaohs at the end of the Third Dynasty, but the f ...

s, that enclosed small groups of signs in many hieroglyphic texts, and in 1762 he suggested that cartouches contained the names of kings or gods. Carsten Niebuhr

Carsten Niebuhr, or Karsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 Lüdingworth – 26 April 1815 Meldorf, Dithmarschen), was a German mathematician, cartographer, and explorer in the service of Denmark. He is renowned for his participation in the Royal Danish ...

, who visited Egypt in the 1760s, produced the first systematic, though incomplete, list of distinct hieroglyphic signs. He also pointed out the distinction between hieroglyphic text and the illustrations that accompanied it, whereas earlier scholars had confused the two. Joseph de Guignes, one of several scholars of the time who speculated that Chinese culture

Chinese culture () is one of the world's oldest cultures, originating thousands of years ago. The culture prevails across a large geographical region in East Asia and is extremely diverse and varying, with customs and traditions varying grea ...

had some historical connection to ancient Egypt, believed Chinese writing

Written Chinese () comprises Chinese characters used to represent the Chinese language. Chinese characters do not constitute an alphabet or a compact syllabary. Rather, the writing system is roughly Logogram, logosyllabic; that is, a character gen ...

was an offshoot of hieroglyphs. In 1785 he repeated Barthélémy's suggestion about cartouches, comparing it with a Chinese practice that set proper names apart from the surrounding text.

Jørgen Zoëga, the most knowledgeable scholar of Coptic in the late eighteenth century, made several insights about hieroglyphs in ''De origine et usu obeliscorum'' (1797), a compendium of knowledge about ancient Egypt. He catalogued hieroglyphic signs and concluded that there were too few distinct signs for each one to represent a single word, so to produce a full vocabulary they must have each had multiple meanings or changed meaning by combining with each other. He saw that the direction the signs faced indicated the direction in which a text was meant to be read, and he suggested that some signs were phonetic. Zoëga did not attempt to decipher the script, believing that doing so would require more evidence than was available in Europe at the time.

Identifying signs

Rosetta Stone

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

invaded Egypt in 1798, Bonaparte brought with him a corps of scientists and scholars, generally known as the ''savants'', to study the land and its ancient monuments. In July 1799, when French soldiers were rebuilding a Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

fort near the town of Rosetta

Rosetta or Rashid (; ar, رشيد ' ; french: Rosette ; cop, ϯⲣⲁϣⲓⲧ ''ti-Rashit'', Ancient Greek: Βολβιτίνη ''Bolbitinē'') is a port city of the Nile Delta, east of Alexandria, in Egypt's Beheira governorate. The R ...

that they had dubbed Fort Julien

Fort Julien (or, in some sources, ''Fort Rashid'') (Arabic language, Arabic: طابية رشيد) is a fort located on the left or west bank of the Nile about north-west of Rashid (Rosetta) on the north coast of Egypt. It was originally built ...

, Lieutenant Pierre-François Bouchard

Pierre-François Bouchard (29 April 1771, Orgelet – 5 August 1822, Givet) was an officer in the French Army of engineers. He is most famous for discovering the Rosetta Stone, an important archaeological find that allowed Ancient Egyptian writ ...

noticed that one of the stones from a demolished wall in the fort was covered with writing. It was an ancient Egyptian stela

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), wh ...

, divided into three registers of text, with its lower right corner and most of its upper register broken off. The stone was inscribed with three scripts: hieroglyphs in the top register, Greek at the bottom and an unidentified script in the middle. The text was a decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used ...

issued in 197BC by Ptolemy V

egy, Iwaennetjerwymerwyitu Seteppah Userkare Sekhem-ankhamun Clayton (2006) p. 208.

, predecessor = Ptolemy IV

, successor = Ptolemy VI

, horus = '' ḥwnw-ḫꜤj-m-nsw-ḥr-st-jt.f'Khunukhaiemnisutkhersetitef'' The youth who ...

, granting favours to Egypt's priesthoods. The text ended by calling for copies of the decree to be inscribed "in sacred, and native, and Greek characters" and set up in Egypt's major temples. Upon reading this passage in the Greek inscription the French realised the stone was a parallel text

A parallel text is a text placed alongside its translation or translations. Parallel text alignment is the identification of the corresponding sentences in both halves of the parallel text. The Loeb Classical Library and the Clay Sanskrit Libr ...

, which could allow the Egyptian text to be deciphered based on its Greek translation. The savants eagerly sought other fragments of the stela as well as other texts in Greek and Egyptian. No further pieces of the stone were ever found, and the only other bilingual texts the savants discovered were largely illegible and useless for decipherment. The savants did make some progress with the stone itself. Jean-Joseph Marcel

Jean-Joseph Marcel (24 November 1776 – 11 March 1854) was a French printer and engineer. He was also a ''savant'' who accompanied Napoleon's 1798 campaign in Egypt as a member of the Commission des Sciences et des Arts, a corps of 167 technical ...

said the middle script was "cursive characters of the ancient Egyptian language", identical to others he had seen on papyrus scrolls. He and Louis Rémi Raige began comparing the text of this register with the Greek one, reasoning that the middle register would be more fruitful than the hieroglyphic text, most of which was missing. They guessed at the positions of proper names in the middle register, based on the position of those names in the Greek text, and managed to identify the ''p'' and ''t'' in the name of Ptolemy, but they made no further progress.

The first copies of the stone's inscriptions were sent to France in 1800. In 1801 the French force in Egypt was besieged by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and the British and surrendered in the Capitulation of Alexandria. By its terms, the Rosetta Stone passed to the British. Upon the stone's arrival in Britain, the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

made engravings of its text and sent them to academic institutions across Europe.

Reports from Napoleon's expedition spurred a mania for ancient Egypt in Europe. Egypt was chaotic in the wake of the French and British withdrawal, but after Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

took control of the country in 1805, European collectors descended on Egypt and carried away numerous antiquities, while artists copied others. No one knew these artefacts' historical context, but they contributed to the corpus of texts that scholars could compare when trying to decipher the writing systems.

De Sacy, Åkerblad and Young

Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy

Antoine Isaac, Baron Silvestre de Sacy (; 21 September 175821 February 1838), was a French nobleman, linguist and orientalist. His son, Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy, became a journalist.

Life and works

Early life

Silvestre de Sacy was born in Pa ...

, a prominent French linguist who had deciphered the Persian Pahlavi script

Pahlavi is a particular, exclusively written form of various Middle Iranian languages. The essential characteristics of Pahlavi are:

*the use of a specific Aramaic-derived script;

*the incidence of Aramaic words used as heterograms (called '' ...

in 1787, was among the first to work on the stone. Like Marcel and Raige he concentrated on relating the Greek text to the demotic script in the middle register. Based on Plutarch he assumed this script consisted of 25 phonetic signs. De Sacy looked for Greek proper names within the demotic text and attempted to identify the phonetic signs within them, but beyond identifying the names of Ptolemy, Alexander and Arsinoe he made little progress. He realised that there were far more than 25 signs in demotic and that the demotic inscription was probably not a close translation of the Greek one, thus making the task more difficult. After publishing his results in 1802 he ceased working on the stone.

In the same year de Sacy gave a copy of the stone's inscriptions to a former student of his, Johan David Åkerblad

Johan David Åkerblad (6 May 1763, Stockholm – 7 February 1819, Rome) was a Swedish diplomat and orientalist.

Career

In 1778 he began his studies of classical and oriental languages at the University of Uppsala. In 1782 he defended his gr ...

, a Swedish diplomat and amateur linguist. Åkerblad had greater success, analysing the same sign-groups as de Sacy but identifying more signs correctly. In his letters to de Sacy Åkerblad proposed an alphabet of 29 demotic signs, half of which were later proven correct, and based on his knowledge of Coptic identified several demotic words within the text. De Sacy was sceptical of his results, and Åkerblad too gave up. Despite attempts by other scholars, little further progress was made until more than a decade later, when Thomas Young entered the field.

Young was a British

Young was a British polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

whose fields of expertise included physics, medicine and linguistics. By the time he turned his attention to Egypt he was regarded as one of the foremost intellectuals of the day. In 1814 he began corresponding with de Sacy about the Rosetta Stone, and after some months he produced what he called translations of the hieroglyphic and demotic texts of the stone. They were in fact attempts to break the texts down into groups of signs to find areas where the Egyptian text was most likely to closely match the Greek. This approach was of limited use because the three texts were not exact translations of each other. Young spent months copying other Egyptian texts, which enabled him to see patterns in them that others missed. Like Zoëga, he recognised that there were too few hieroglyphs for each to represent one word, and he suggested that words were composed of two or three hieroglyphs each.

Young noticed the similarities between hieroglyphic and demotic signs and concluded that the hieroglyphic signs had evolved into the demotic ones. If so, Young reasoned, demotic could not be a purely phonetic script but must also include ideographic signs that were derived from hieroglyphs; he wrote to de Sacy with this insight in 1815. Although he hoped to find phonetic signs in the hieroglyphic script, he was thwarted by the wide variety of phonetic spellings the script used. He concluded that phonetic hieroglyphs did not exist—with a major exception. In his 1802 publication de Sacy had said hieroglyphs might function phonetically when writing foreign words. In 1811 he suggested, after learning about a similar practice in Chinese writing, that a cartouche signified a word written phonetically—such as the name of a non-Egyptian ruler like Ptolemy. Young applied these suggestions to the cartouches on the Rosetta Stone. Some were short, consisting of eight signs, while others contained those same signs followed by many more. Young guessed that the long cartouches contained the Egyptian form of the title given to Ptolemy in the Greek inscription: "living for ever, beloved of he godPtah

Ptah ( egy, ptḥ, reconstructed ; grc, Φθά; cop, ⲡⲧⲁϩ; Phoenician: 𐤐𐤕𐤇, romanized: ptḥ) is an ancient Egyptian deity, a creator god and patron deity of craftsmen and architects. In the triad of Memphis, he is the hu ...

". Therefore he concentrated on the first eight signs, which should correspond to the Greek form of the name, ''Ptolemaios''. Adopting some of the phonetic values proposed by Åkerblad, Young matched the eight hieroglyphs to their demotic equivalents and proposed that some signs represented several phonetic values while others stood for just one. He then attempted to apply the results to a cartouche of Berenice, the name of a Ptolemaic queen, with less success, although he did identify a pair of hieroglyphs that marked the ending of a feminine name. The result was a set of thirteen phonetic values for hieroglyphic and demotic signs. Six were correct, three partly correct, and four wrong.

Young summarised his work in his article "Egypt", published anonymously in a supplement to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' in 1819. It gave conjectural translations for 218 words in demotic and 200 in hieroglyphic and correctly correlated about 80 hieroglyphic signs with demotic equivalents. As the Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith

Francis Llewellyn Griffith (27 May 1862 – 14 March 1934) was an eminent British Egyptologist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Early life and education

F. Ll. Griffith was born in Brighton on 27 May 1862 where his father, Rev. Dr. ...

put it in 1922, Young's results were "mixed up with many false conclusions, but the method pursued was infallibly leading to definite decipherment." Yet Young was less interested in ancient Egyptian texts themselves than in the writing systems as an intellectual puzzle, and his multiple scientific interests made it difficult for him to concentrate on decipherment. He achieved little more on the subject in the next few years.

Champollion's breakthroughs

Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion (), also known as Champollion ''le jeune'' ('the Younger'; 23 December 17904 March 1832), was a French philologist and orientalist, known primarily as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs and a founding figure in t ...

had developed a fascination with ancient Egypt in adolescence, between about 1803 and 1805, and he had studied Near Eastern languages, including Coptic, under de Sacy and others. His brother, Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac, was an assistant to Bon-Joseph Dacier

Bon Joseph Dacier (Valognes, 1 April 1742 – Paris, 4 February 1833) was a French historian, philologist and translator of ancient Greek. He became a Chevalier de l'Empire (16 December 1813), then Baron de l'Empire (29 May 1830). He also serve ...

, the head of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

The Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres () is a French learned society devoted to history, founded in February 1663 as one of the five academies of the Institut de France. The academy's scope was the study of ancient inscriptions (epigr ...

in Paris, and in that position provided Jean-François with the means to keep up with research on Egypt. By the time Young was working on hieroglyphs Champollion had published a compendium of the established knowledge on ancient Egypt and assembled a Coptic dictionary, but though he wrote much on the subject of the undeciphered scripts, he was making no progress with them. As late as 1821 he believed that none of the scripts were phonetic. In the following years, however, he surged ahead. The details of how he did so cannot be fully known because of gaps in the evidence and conflicts in the contemporary accounts.

Champollion was initially dismissive of Young's work, having seen only excerpts from Young's list of hieroglyphic and demotic words. After moving to Paris from Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

in mid-1821 he would have been better able to obtain a full copy, but it is not known whether he did so. It was about this time that he turned his attention to identifying phonetic sounds within cartouches.

A crucial clue came from the Philae Obelisk

The Philae obelisk is one of a pair of twin obelisks erected at Philae in Upper Egypt in the second century BC. It was discovered by William John Bankes in 1815, who had it brought to Kingston Lacy in Dorset, England, where it still stands today ...

, an obelisk bearing both a Greek and an Egyptian inscription. William John Bankes

William John Bankes (11 December 1786 – 15 April 1855) was an English politician, explorer, Egyptologist and adventurer.

The second, but first surviving, son of Henry Bankes MP, he was a member of the Bankes family of Dorset and he had Sir Ch ...

, an English antiquities collector, shipped the obelisk from Egypt to England and copied its inscriptions. These inscriptions were not a single bilingual text like that of the Rosetta Stone, as Bankes assumed, but both inscriptions contained the names "Ptolemy" and "Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

", the hieroglyphic versions being enclosed by cartouches. The Ptolemy cartouche was identifiable based on the Rosetta Stone, but Bankes could only guess based on the Greek text that the second represented Cleopatra's name. His copy of the text suggested this reading of the cartouche in pencil. Champollion, who saw the copy in January 1822, treated the cartouche as that of Cleopatra but never stated how he identified it; he could have done so in more than one way, given the evidence available to him. Bankes angrily assumed Champollion had taken his suggestion without giving credit and refused to give him any further help.

Champollion broke down the hieroglyphs in Ptolemy's name differently from Young and found that three of his conjectured phonetic signs—''p'', ''l'' and ''o''—fitted into Cleopatra's cartouche. A fourth, ''e'', was represented by a single hieroglyph in Cleopatra's cartouche and a doubled version of the same glyph in Ptolemy's cartouche. A fifth sound, ''t'', seemed to be written with different signs in each cartouche, but Champollion decided these signs must be homophone

A homophone () is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A ''homophone'' may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example ''rose'' (flower) and ''rose'' (pa ...

s, different signs spelling the same sound. He proceeded to test these letters in other cartouches, identify the names of many Greek and Roman rulers of Egypt and extrapolate the values of still more letters.

In July Champollion rebutted an analysis by Jean-Baptiste Biot

Jean-Baptiste Biot (; ; 21 April 1774 – 3 February 1862) was a French physicist, astronomer, and mathematician who co-discovered the Biot–Savart law of magnetostatics with Félix Savart, established the reality of meteorites, made an early ba ...

of the text surrounding an Egyptian temple relief known as the Dendera Zodiac. In doing so he pointed out that hieroglyphs of stars in this text seemed to indicate that the nearby words referred to something related to stars, such as constellations. He called the signs used in this way "signs of the type", although he would later dub them "determinatives".

Champollion announced his proposed readings of the Greco-Roman cartouches in his '' Lettre à M. Dacier'', which he completed on 22 September 1822. He read it to the Académie on 27 September, with Young among the audience. This letter is often regarded as the founding document of Egyptology, but it represented only a modest advance over Young's work. Yet it ended by suggesting, without elaboration, that phonetic signs might have been used in writing proper names from a very early point in Egyptian history. How Champollion reached this conclusion is mostly not recorded in contemporary sources. His own writings suggest that one of the keys was his conclusion that the Abydos King List contained the name " Ramesses", a royal name found in the works of Manetho, and that some of his other evidence came from copies of inscriptions in Egypt made by Jean-Nicolas Huyot.

According to Hermine Hartleben

Hermine Ida Auguste Hartleben (2 June 1846 – 18 July 1919) was a German Egyptologist. She was the daughter of a forest officer in Altenau. Later, she studied in Hanover and became a teacher. She studied Greek archaeology at the Sorbonne, taught ...

, who wrote the most extensive biography of Champollion in 1906, the breakthrough came on 14 September 1822, a few days before the ''Lettre'' was written, when Champollion was examining Huyot's copies. One cartouche from Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel ( ar, أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is situated on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about ...

contained four hieroglyphic signs. Champollion guessed, or drew on the same guess found in Young's ''Britannica'' article, that the circular first sign represented the sun. The Coptic word for "sun" was ''re''. The sign that appeared twice at the end of the cartouche stood for "s" in the cartouche of Ptolemy. If the name in the cartouche began with ''Re'' and ended with ''ss'', it might thus match "Ramesses", suggesting the sign in the middle stood for ''m''. Further confirmation came from the Rosetta Stone, where the ''m'' and ''s'' signs appeared together at a point corresponding to the word for "birth" in the Greek text, and from Coptic, in which the word for "birth" was ''mise''. Another cartouche contained three signs, two of them the same as in the Ramesses cartouche. The first sign, an ibis

The ibises () (collective plural ibis; classical plurals ibides and ibes) are a group of long-legged wading birds in the family Threskiornithidae, that inhabit wetlands, forests and plains. "Ibis" derives from the Latin and Ancient Greek word ...

, was a known symbol of the god Thoth

Thoth (; from grc-koi, Θώθ ''Thṓth'', borrowed from cop, Ⲑⲱⲟⲩⲧ ''Thōout'', Egyptian: ', the reflex of " eis like the Ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or ...

. If the latter two signs had the same values as in the Ramesses cartouche, the name in the second cartouche would be ''Thothmes'', corresponding to the royal name " Tuthmosis" mentioned by Manetho. These were native Egyptian kings, long predating Greek rule in Egypt, yet the writing of their names was partially phonetic. Now Champollion turned to the title of Ptolemy found in the longer cartouches in the Rosetta Stone. Champollion knew the Coptic words that would translate the Greek text and could tell that phonetic hieroglyphs such as ''p'' and ''t'' would fit these words. From there he could guess the phonetic meanings of several more signs. By Hartleben's account, upon making these discoveries Champollion raced to his brother's office at the Académie des Inscriptions, flung down a collection of copied inscriptions, cried "''Je tiens mon affaire!''" ("I've done it!") and collapsed in a days-long faint.

Over the next few months Champollion applied his hieroglyphic alphabet to many Egyptian inscriptions, identifying dozens of royal names and titles. During this period Champollion and the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin examined the

Over the next few months Champollion applied his hieroglyphic alphabet to many Egyptian inscriptions, identifying dozens of royal names and titles. During this period Champollion and the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin examined the Caylus vase

The Caylus vase is an Egyptian alabaster jar dedicated in the name of the Achaemenid king Xerxes I (c.518–465 BCE) in Egyptian hieroglyph and Old Persian cuneiform. Beyond its historical value as a dynastic artifact of Achaemenid Egypt, its quad ...

, which bore a hieroglyphic cartouche as well as text in Persian cuneiform

Old Persian cuneiform is a semi-alphabetic cuneiform script that was the primary script for Old Persian. Texts written in this cuneiform have been found in Iran (Persepolis, Susa, Hamadan, Kharg Island), Armenia, Romania ( Gherla), Turkey ( Van ...

. Saint-Martin believed the cuneiform text to bear the name of Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

, a king of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

in the fifth century BC whose realm included Egypt. Champollion confirmed that the identifiable signs in the cartouche matched Xerxes's name, strengthening the evidence that phonetic hieroglyphs were used before Greek rule in Egypt and supporting Saint-Martin's reading of the cuneiform text. This was a major step in the decipherment of cuneiform.

Around this time Champollion made a second breakthrough. Although he counted about 860 hieroglyphic signs, a handful of those signs made up a large proportion of any given text. He also came upon a recent study of Chinese by Abel Rémusat

Abel ''Hábel''; ar, هابيل, Hābīl is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He was the younger brother of Cain, and the younger son of Adam and Eve, the first couple in Biblical history. He was a shepherd ...

, which showed that even Chinese writing used phonetic characters extensively, and that its ideographic signs had to be combined into many ligatures to form a full vocabulary. Few hieroglyphs seemed to be ligatures. And Champollion had identified the name of Antinous

Antinous, also called Antinoös, (; grc-gre, Ἀντίνοος; 27 November – before 30 October 130) was a Greek youth from Bithynia and a favourite and probable lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Following his premature death before his ...

, a non-royal Roman, written in hieroglyphs with no cartouche, next to characters that seemed to be ideographic. Phonetic signs were thus not limited to cartouches. To test his suspicions, Champollion compared hieroglyphic texts that seemed to contain the same content and noted discrepancies in spelling, which indicated the presence of homophones. He compared the resulting list of homophones with the table of phonetic signs from his work on the cartouches and found they matched.

Champollion announced these discoveries to the Académie des Inscriptions in April 1823. From there he progressed rapidly in identifying new signs and words. He concluded the phonetic signs made up a consonantal alphabet

An abjad (, ar, أبجد; also abgad) is a writing system in which only consonants are represented, leaving vowel sounds to be inferred by the reader. This contrasts with other alphabets, which provide graphemes for both consonants and vowels ...

in which vowels were only sometimes written. A summary of his findings, published in 1824 as ''Précis du système hiéroglyphique'', stated "Hieroglyphic writing is a complex system, a script all at once figurative, symbolic and phonetic, in one and the same text, in one and the same sentence, and, I might even venture, one and the same word." The ''Précis'' identified hundreds of hieroglyphic words, described differences between hieroglyphs and other scripts, analysed proper names and the uses of cartouches and described some of the language's grammar. Champollion was moving from deciphering a script to translating the underlying language.

Disputes

The ''Lettre à M. Dacier'' mentioned Young as having worked on demotic and referred to Young's attempt to decipher the name of Berenice, but it did not mention Young's breakdown of Ptolemy's name nor that the feminine name-ending, which was also found in Cleopatra's name on the Philae Obelisk, had been Young's discovery. Believing that these discoveries had made Champollion's progress possible, Young expected to receive much of the credit for whatever Champollion ultimately produced. In private correspondence shortly after the reading of the ''Lettre'', Young quoted a French saying that meant "It's the first step that counts", although he also said "if hampolliondid borrow an English key, the lock was so dreadfully rusty, that no common arm would have strength enough to turn it". In 1823 Young published a book on his Egyptian work, ''An Account of Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature and Egyptian Antiquities'', and responded to Champollion's slight in the subtitle: "Including the Author's Original Hieroglyphic Alphabet, As Extended by Mr Champollion". Champollion angrily responded, "I shall never consent to recognise any other original alphabet than my own, where it is a matter of the hieroglyphic alphabet properly called". The ''Précis'' in the following year acknowledged Young's work, but in it Champollion said he had arrived at his conclusions independently, without seeing Young's ''Britannica'' article. Scholarly opinion ever since has been divided on whether Champollion was being truthful. Young would continue to push for greater acknowledgement, while expressing a mixture of admiration of Champollion's work and scepticism of some of his conclusions. Relations between them varied between cordial and contentious until Young's death in 1829. As he continued to work on hieroglyphs, making mistakes alongside many successes, Champollion was embroiled in a related dispute, with scholars who rejected the validity of his work. Among them were Edme Jomard, a veteran of Napoleon's expedition, and Heinrich Julius Klaproth, a German orientalist. Some championed Young at the same time. The scholar who held out longest against Champollion's decipherment was Gustav Seyffarth. His opposition to Champollion culminated in a public argument with him in 1826, and he continued to advocate his own approach to hieroglyphs until his death in 1885. As the nature of hieroglyphs became clearer, detractors of this kind fell away, but the argument over how much Champollion owed to Young continues. Nationalist rivalry between the English and French exacerbates the issue. Egyptologists are often reluctant to criticise Champollion, who is regarded as the founder of their discipline, and by extension can be reluctant to credit Young. The Egyptologist Richard Parkinson takes a moderate position: "Even if one allows that Champollion was more familiar with Young's initial work than he subsequently claimed, he remains the decipherer of the hieroglyphic script… Young discovered parts of an alphabet—a key—but Champollion unlocked an entire language."Reading texts

Young and demotic

Young's work on hieroglyphs petered out during the 1820s, but his work on demotic continued, aided by a fortuitous discovery. One of his sources for studying the script was a text in a collection known as the Casati papyri; Young had identified several Greek names in this text. In November 1822 an acquaintance of his, George Francis Grey, loaned him a box of Greek papyri found in Egypt. Upon examining them Young realised that one contained the same names as the demotic Casati text. The two texts were versions of the same document, in Greek and demotic, recording the sale of a portion of the offerings made on behalf of a group of deceased Egyptians. Young had long tried to obtain a second bilingual text to supplement the Rosetta Stone. With these texts in hand, he made major progress over the next few years. In the mid-1820s he was diverted by his other interests, but in 1827 he was spurred by a letter from an Italian scholar of Coptic, Amedeo Peyron, that said Young's habit of moving from one subject to another hampered his achievements and suggested he could accomplish much more if he concentrated on ancient Egypt. Young spent the last two years of his life working on demotic. At one point he consulted Champollion, then a curator at theLouvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the '' Venus de Milo''. A central ...

, who treated him amicably, gave him access to his notes about demotic and spent hours showing him the demotic texts in the Louvre's collection. Young's ''Rudiments of an Egyptian Dictionary in the Ancient Enchorial Character'' was published posthumously in 1831. It included a full translation of one text and large portions of the text of the Rosetta Stone. According to the Egyptologist John Ray, Young "probably deserves to be known as the decipherer of demotic."

Champollion's last years

By 1824 the Rosetta Stone, with its limited hieroglyphic text, had become irrelevant for further progress on hieroglyphs. Champollion needed more texts to study, and few were available in France. From 1824 through 1826 he made two visits to Italy and studied the Egyptian antiquities found there, particularly those recently shipped from Egypt to theEgyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, known commonly as the Egyptian Museum or the Cairo Museum, in Cairo, Egypt, is home to an extensive collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities. It has 120,000 items, with a representative amount on display a ...

in Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

. By reading the inscriptions on dozens of statues and stelae

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

, Champollion became the first person in centuries to identify the kings who had commissioned them, although in some cases his identifications were incorrect. He also looked at the museum's papyri and was able to discern their subject matter. Of particular interest was the Turin King List The Turin King List, also known as the Turin Royal Canon, is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus thought to date from the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II, now in the Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum) in Turin. The papyrus is the most extensive list a ...

, a papyrus listing Egyptian rulers and the lengths of their reigns up to the thirteenth centuryBC, which would eventually furnish a framework for the chronology of Egyptian history but lay in pieces when Champollion saw it. While in Italy Champollion befriended Ippolito Rosellini

Niccola Francesco Ippolito Baldassarre Rosellini, known simply as Ippolito RoselliniBardelli 1843, p. 4 (13 August 1800 – 4 June 1843) was an Italian Egyptologist. A scholar and friend of Jean-François Champollion, he is regarded as t ...

, a Pisan linguist who was swept up in Champollion's fervour for ancient Egypt and began studying with him. Champollion also worked on assembling a collection of Egyptian antiquities at the Louvre, including the texts he would later show to Young. In 1827 he published a revised edition of the ''Précis'' that included some of his recent findings.

Antiquarians living in Egypt, especially John Gardner Wilkinson

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (5 October 1797 – 29 October 1875) was an English traveller, writer and pioneer Egyptologist of the 19th century. He is often referred to as "the Father of British Egyptology".

Childhood and education

Wilkinson ...

, were already applying Champollion's findings to the texts there. Champollion and Rosellini wanted to do so themselves, and together with some other scholars and artists they formed the Franco-Tuscan Expedition to Egypt. En route to Egypt Champollion stopped to look at a papyrus in the hands of a French antiquities dealer. It was a copy of the '' Instructions of King Amenemhat'', a work of wisdom literature

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it ...

cast as posthumous advice from Amenemhat I

:''See Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat I ( Ancient Egyptian: ''Ỉmn-m-hꜣt'' meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet I, was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the first king of the Twelfth Dynas ...

to his son and successor. It became the first work of ancient Egyptian literature

Ancient Egyptian literature was written in the Egyptian language from ancient Egypt's pharaonic period until the end of Roman domination. It represents the oldest corpus of Egyptian literature. Along with Sumerian literature, it is conside ...

to be read, although Champollion could not read it well enough to fully understand what it was. In 1828 and 1829 the expedition travelled the length of the Egyptian course of the Nile, copying and collecting antiquities. After studying countless texts Champollion felt certain that his system was applicable to hieroglyphic texts from every period of Egyptian history, and he apparently coined the term "determinative" while there.

After returning from Egypt Champollion spent much of his time working on a full description of the Egyptian language, but he had little time to complete it. Beginning in late 1831 he suffered a series of increasingly debilitating strokes, and he died in March 1832.

Mid-nineteenth century

Champollion-Figeac published his brother's grammar of Egyptian and an accompanying dictionary in instalments from 1836 to 1843. Both were incomplete, especially the dictionary, which was confusingly organised and contained many conjectural translations. These works' deficiencies reflected the incomplete state of understanding of Egyptian upon Champollion's death. Champollion often went astray by overestimating the similarity between classical Egyptian and Coptic. As Griffith put it in 1922, "In reality Coptic is a remote derivative from ancient Egyptian, like French from Latin; in some cases, therefore, Champollion's provisional transcripts produced good Coptic words, while mostly they were more or less meaningless or impossible, and in transcribing phrases either Coptic syntax was hopelessly violated or the order of hieroglyphic words had to be inverted. This was all very baffling and misleading." Champollion was also unaware that signs could spell two or three consonants as well as one. Instead he thought every phonetic sign represented one sound and each sound had a great many homophones. Thus the middle sign in the cartouches of Ramesses and Thutmose was biliteral, representing the consonant sequence ''ms'', but Champollion read it as ''m''. Neither had he struck upon the concept now known as a "phonetic complement": a uniliteral sign that was added at the end of a word, re-spelling a sound that had already been written out in a different way. Most of Champollion's collaborators lacked the linguistic abilities needed to advance the decipherment process, and many of them died early deaths.Edward Hincks

Edward Hincks (19 August 1792 – 3 December 1866) was an Irish clergyman, best remembered as an Assyriologist and one of the decipherers of Mesopotamian cuneiform. He was one of the three men known as the "holy trinity of cuneiform", with S ...

, an Irish clergyman whose primary interest was the decipherment of cuneiform, made important contributions in the 1830s and 1840s. Whereas Champollion's translations of texts had filled in gaps in his knowledge with informed guesswork, Hincks tried to proceed more systematically. He identified grammatical elements in Egyptian, such as particles

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscule in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

and auxiliary verb

An auxiliary verb ( abbreviated ) is a verb that adds functional or grammatical meaning to the clause in which it occurs, so as to express tense, aspect, modality, voice, emphasis, etc. Auxiliary verbs usually accompany an infinitive verb or a ...

s, that did not exist in Coptic, and he argued that the sounds of the Egyptian language were similar to those of Semitic languages

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of West Asia, the Horn of Africa, and latterly North Africa, Malta, West Africa, Chad, and in large immigrant ...

. Hincks also improved the understanding of hieratic, which had been neglected in Egyptological studies thus far.

The scholar who corrected the most fundamental faults in Champollion's work was Karl Richard Lepsius

Karl Richard Lepsius ( la, Carolus Richardius Lepsius) (23 December 181010 July 1884) was a pioneering Prussian Egyptologist, linguist and modern archaeologist.

He is widely known for his magnum opus '' Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopie ...