Death of Hank Williams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hiram "Hank" Williams died on January 1, 1953, at the age of 29. Williams was an American singer-songwriter and musician regarded as one of the most significant country music artists of all time. Williams was born with a mild undiagnosed case of

/ref> An estimated 15,000 to 25,000 people passed by the silver coffin, and the auditorium was filled with 2,750 mourners. During the funeral four women fainted and a fifth was carried out of the auditorium in hysterics after falling at the foot of the casket. His funeral was said to have been far larger than any ever held for any other citizen of

As part of an investigation of illicit drug traffic conducted by the Oklahoma legislature, representative Robert Cunningham seized Marshall's files. During an initial hearing, Marshall insisted that he was a doctor, refusing to answer further statements. Marshall gave Cunningham a list of his patients, including Hank Williams. Defending his position, he claimed that Williams possibly committed suicide. Marshall stated that Williams told him that he had decided to "destroy the Hank Williams that was making the money they were getting". He attributed the decision to Williams' declining career: "Most of his bookings were of the honky-tonk beer joint variety that he simply hated. If he came to this conclusion (of suicide), he still had enough prestige left as a star to make a first-class production of it ... whereas, six months from now, unless he pulled himself back up into some high-class bookings, he might have been playing for nickels and dimes on skid row."

On March 10, Marshall was called again to testify. He acknowledged that in previous testimony he had falsely claimed to be a physician. Representative Cunningham presented the committee a telegram from Marshall's seized files, directed to the estate of Hank Williams for $736.39, and stated that the committee was evaluating the revocation of Marshall's parole. On March 12, 1953, Billie Jean Jones appeared before the Oklahoma committee. She stated that she received after Williams' death a bill for $800 from Marshall for the treatment. Jones refused to pay, and further stated that Marshall later intended to convince her to pay him by assuring that he would "pave her the way to collect her husband's state". Jones declared "I have never accepted the report that my husband died of a heart attack."

On March 19, Marshall declared that he felt Williams was depressed and committed suicide by taking a higher dose of the drugs he had prescribed. Marshall admitted that he had also prescribed chloral hydrate to his recently deceased wife, Faye, as a headache medicine. He denied any responsibility in both deaths. On March 21, Robert Travis of the State Crime Bureau determined that Marshall's handwriting corresponded to that of Dr. Cecil W. Lemmon on six prescriptions written for Williams. The same day, the District Attorney's office declared that after a new review of the autopsy report of Faye Marshall, toxicological and microscopic tests confirmed that her death on March 3 was not related to the medication prescribed by her husband.

As part of an investigation of illicit drug traffic conducted by the Oklahoma legislature, representative Robert Cunningham seized Marshall's files. During an initial hearing, Marshall insisted that he was a doctor, refusing to answer further statements. Marshall gave Cunningham a list of his patients, including Hank Williams. Defending his position, he claimed that Williams possibly committed suicide. Marshall stated that Williams told him that he had decided to "destroy the Hank Williams that was making the money they were getting". He attributed the decision to Williams' declining career: "Most of his bookings were of the honky-tonk beer joint variety that he simply hated. If he came to this conclusion (of suicide), he still had enough prestige left as a star to make a first-class production of it ... whereas, six months from now, unless he pulled himself back up into some high-class bookings, he might have been playing for nickels and dimes on skid row."

On March 10, Marshall was called again to testify. He acknowledged that in previous testimony he had falsely claimed to be a physician. Representative Cunningham presented the committee a telegram from Marshall's seized files, directed to the estate of Hank Williams for $736.39, and stated that the committee was evaluating the revocation of Marshall's parole. On March 12, 1953, Billie Jean Jones appeared before the Oklahoma committee. She stated that she received after Williams' death a bill for $800 from Marshall for the treatment. Jones refused to pay, and further stated that Marshall later intended to convince her to pay him by assuring that he would "pave her the way to collect her husband's state". Jones declared "I have never accepted the report that my husband died of a heart attack."

On March 19, Marshall declared that he felt Williams was depressed and committed suicide by taking a higher dose of the drugs he had prescribed. Marshall admitted that he had also prescribed chloral hydrate to his recently deceased wife, Faye, as a headache medicine. He denied any responsibility in both deaths. On March 21, Robert Travis of the State Crime Bureau determined that Marshall's handwriting corresponded to that of Dr. Cecil W. Lemmon on six prescriptions written for Williams. The same day, the District Attorney's office declared that after a new review of the autopsy report of Faye Marshall, toxicological and microscopic tests confirmed that her death on March 3 was not related to the medication prescribed by her husband.

spina bifida occulta

Spina bifida (Latin for 'split spine'; SB) is a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and the membranes around the spinal cord during early development in pregnancy. There are three main types: spina bifida occulta, m ...

, a disorder of the spinal column, which gave him lifelong pain—a factor in his later abuse of alcohol and other drugs. In 1951, Williams fell during a hunting trip in Tennessee, reactivating his old back pains and causing him to be dependent on alcohol and prescription drugs. This addiction eventually led to his divorce from Audrey Williams

Audrey Mae Sheppard Williams (February 28, 1923 – November 4, 1975) was an American musician known for being the first wife of country music singer and songwriter Hank Williams, the mother of Hank Williams Jr. and the grandmother of Hank Willia ...

and his dismissal from the Grand Ole Opry

The ''Grand Ole Opry'' is a weekly American country music stage concert in Nashville, Tennessee, founded on November 28, 1925, by George D. Hay as a one-hour radio "barn dance" on WSM. Currently owned and operated by Opry Entertainment (a divis ...

.

Williams was scheduled to perform at the Municipal Auditorium in Charleston, West Virginia

Charleston is the capital and List of cities in West Virginia, most populous city of West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Elk River (West Virginia), Elk and Kanawha River, Kanawha rivers, the city had a population of 48,864 at the 20 ...

. Williams had to cancel the concert due to an ice storm; he hired college student Charles Carr to drive him to his next appearance, a concert on New Year's Day 1953, at the Canton Memorial Auditorium in Canton, Ohio

Canton () is a city in and the county seat of Stark County, Ohio. It is located approximately south of Cleveland and south of Akron in Northeast Ohio. The city lies on the edge of Ohio's extensive Amish country, particularly in Holmes and ...

. In Knoxville, Tennessee, the two stopped at the Andrew Johnson Hotel

The Andrew Johnson Building is a high-rise building in downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. Completed in 1929 as the Andrew Johnson Hotel, at , it was Knoxville's tallest building for nearly a half-century.Ronald Childress, National Regi ...

. Carr requested a doctor for Williams, who was feeling the combination of the chloral hydrate

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula . It is a colorless solid. It has limited use as a sedative and hypnotic pharmaceutical drug. It is also a useful laboratory chemical reagent and precursor. It is derived from chloral (trichl ...

and alcohol he consumed on the way from Montgomery. A doctor injected Williams with two shots of vitamin B12 that contained morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

. Carr talked to Williams for the last time when they stopped at a restaurant in Bristol, Virginia

Bristol is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,219. It is the twin city of Bristol, Tennessee, just across the state line, which runs down the middle of its main street, State S ...

. Carr later kept driving until he reached a gas station in Oak Hill, West Virginia

Oak Hill is a city in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States and is the primary city within the Oak Hill, WV Micropolitan Statistical Area. The micropolitan area is also included in the Beckley-Oak Hill, WV Combined Statistical Area. The ...

, where Williams was discovered unresponsive in the back seat. After determining that Williams was dead, Carr asked for help from the owner of the station who notified the police. After an autopsy, the cause of death was determined to be "insufficiency of the right ventricle of the heart."

Tributes to Williams took place the day after his death. His body was initially transported to Montgomery and placed in a silver coffin shown at his mother's boarding house. The funeral took place on January 4 at the Montgomery Auditorium, where an estimated 15,000 to 25,000 attended while the auditorium was filled with 2,750 mourners.

Background

In 1951, Williams fell during a hunting trip in Tennessee, reactivating his old back pains. Later, he started to consume painkillers, including morphine, and alcohol to ease the pain. His alcoholism worsened in 1952. In June, he divorcedAudrey Williams

Audrey Mae Sheppard Williams (February 28, 1923 – November 4, 1975) was an American musician known for being the first wife of country music singer and songwriter Hank Williams, the mother of Hank Williams Jr. and the grandmother of Hank Willia ...

,Williams, Roger M. p. 96 and on August 11, Williams was dismissed from the Grand Ole Opry

The ''Grand Ole Opry'' is a weekly American country music stage concert in Nashville, Tennessee, founded on November 28, 1925, by George D. Hay as a one-hour radio "barn dance" on WSM. Currently owned and operated by Opry Entertainment (a divis ...

for habitual drunkenness. He returned to perform in KWKH

KWKH (1130 AM) is a sports radio station serving Shreveport, Louisiana. The 50-kilowatt station broadcasts at 1130 kHz. Formerly owned by Clear Channel Communications and Gap Central Broadcasting, it is now owned by Townsquare Media. Its studi ...

and WBAM

WBAM-FM/98.9 ("Bama Country 98.9") is a country music formatted radio station that serves the Montgomery Metropolitan Area, broadcasting on the FM broadcasting, FM band at a frequency of 98.9 MHz and licensed to Montgomery, Alabama. The station is ...

shows and in the ''Louisiana Hayride,'' for which he toured again. His performances were acclaimed when he was sober, but despite the efforts of his work associates to get him to shows sober, his abuse of alcohol resulted in occasions when he did not appear or his performances were poor. In October 1952, he married Billie Jean Jones

Billie Jean Horton ( née Jones; born June 6, 1933) is an American country-music singer-songwriter and former music promoter who is best known for her high profile marriages, first to iconic country musician and singer-songwriter Hank Williams in ...

.Koon, George William; p.70

Due to Williams's excesses, Fred Rose stopped working with him. Also, the Drifting Cowboys

The Drifting Cowboys were the backing group for American country legend and singer-songwriter Hank Williams. The band went through several lineups during Williams' career. The original lineup was formed in 1937, changing musicians from show to sh ...

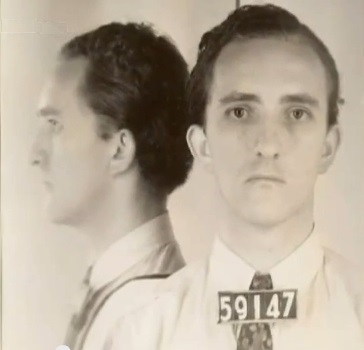

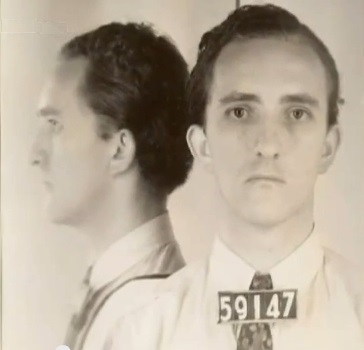

were at the time backing Ray Price, while Williams was backed by local bands. By the end of 1952, Williams had started to suffer heart problems. He met Horace Raphol "Toby" Marshall in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, a ...

, who claimed to be a doctor. Marshall had been previously convicted for forgery

Forgery is a white-collar crime that generally refers to the false making or material alteration of a legal instrument with the specific intent to defraud anyone (other than themself). Tampering with a certain legal instrument may be forbidd ...

, and had been paroled and released from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary

The Oklahoma State Penitentiary, nicknamed "Big Mac", is a prison of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections located in McAlester, Oklahoma, on . Opened in 1908 with 50 inmates in makeshift facilities, today the prison holds more than 750 male off ...

in 1951. Among other fake titles he claimed to be a Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

. He purchased the DSC title for $35 from the "Chicago School of Applied Science"; in the diploma, he requested that the DSc was spelled out as "Doctor of Science and Psychology". Under the name of Dr. C. W. Lemon he prescribed Williams with amphetamines

Substituted amphetamines are a class of compounds based upon the amphetamine structure; it includes all derivative compounds which are formed by replacing, or substituting, one or more hydrogen atoms in the amphetamine core structure with sub ...

, Seconal

Secobarbital (as the sodium salt, originally marketed by Eli Lilly and Company for the treatment of insomnia, and subsequently by other companies as described below, under the brand name Seconal) is a short-acting barbiturate derivative drug that ...

, chloral hydrate

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula . It is a colorless solid. It has limited use as a sedative and hypnotic pharmaceutical drug. It is also a useful laboratory chemical reagent and precursor. It is derived from chloral (trichl ...

, and morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

.

Williams was scheduled to perform at the Municipal Auditorium in Charleston, West Virginia

Charleston is the capital and List of cities in West Virginia, most populous city of West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Elk River (West Virginia), Elk and Kanawha River, Kanawha rivers, the city had a population of 48,864 at the 20 ...

on Wednesday, December 31 (New Year's Eve), 1952. Advance ticket sales totaled US$3,500 (equivalent to US$ in 2011). Because of an ice storm in the Nashville area that day, Williams could not fly, so he hired a college student, Charles Carr, to drive him to the concerts. Carr called the Charleston auditorium from Knoxville to say that Williams would not arrive on time owing to the ice storm and was ordered to drive Williams to Canton, Ohio

Canton () is a city in and the county seat of Stark County, Ohio. It is located approximately south of Cleveland and south of Akron in Northeast Ohio. The city lies on the edge of Ohio's extensive Amish country, particularly in Holmes and ...

for the New Year's Day concert there. Williams and Carr departed from Montgomery, Alabama at around 1:00 p.m.

The final trip

Williams arrived at theAndrew Johnson Hotel

The Andrew Johnson Building is a high-rise building in downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. Completed in 1929 as the Andrew Johnson Hotel, at , it was Knoxville's tallest building for nearly a half-century.Ronald Childress, National Regi ...

in Knoxville, Tennessee, where Carr checked in at 7:08 p.m and ordered two steaks in the lobby to be delivered to their rooms from the hotel's restaurant. He also requested a doctor for Williams, as Williams was feeling the combination of the chloral hydrate and alcohol he had drunk on the way from Montgomery to Knoxville. Dr. P.H. Cardwell injected Williams with two shots of vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in metabolism. It is one of eight B vitamins. It is required by animals, which use it as a cofactor in DNA synthesis, in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. It ...

that also contained a quarter-grain (16.2 mg) of morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

. Carr and Williams checked out of the hotel at around 10:45 p.m. Hotel porters had to carry Williams to his vehicle, an Olympic Blue 1952 Cadillac Series 62

The Cadillac Series 40-62 is a series of cars which was produced by Cadillac from 1940 through 1964. Originally designed to complement the entry level Cadillac Series 61, Series 61, it became the Cadillac Series 6200 in 1959, and remained that unt ...

convertible, as he was coughing and hiccupping. Carr and Williams headed out of Knoxville from the Andrew Johnson Hotel via Gay Street to Magnolia Ave to 11w. At around midnight on New Year's Day, Thursday, January 1, 1953, they crossed the Tennessee state line and arrived in Bristol, Virginia

Bristol is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,219. It is the twin city of Bristol, Tennessee, just across the state line, which runs down the middle of its main street, State S ...

.

Carr stopped at a small all-night restaurant and asked Williams if he wanted to eat. Williams said he did not, and those are thought to be his last words. Carr later drove on until he stopped for fuel at a gas station in Oak Hill, West Virginia

Oak Hill is a city in Fayette County, West Virginia, United States and is the primary city within the Oak Hill, WV Micropolitan Statistical Area. The micropolitan area is also included in the Beckley-Oak Hill, WV Combined Statistical Area. The ...

, where he discovered Williams seemingly asleep in the back seat. He was unresponsive and rigor mortis

Rigor mortis (Latin: ''rigor'' "stiffness", and ''mortis'' "of death"), or postmortem rigidity, is the third stage of death. It is one of the recognizable signs of death, characterized by stiffening of the limbs of the corpse caused by chemic ...

had already begun to set in. Carr immediately realized that he was dead and informed the filling station's owner, Glenn Burdette, who called the chief of the local police, O.H. Stamey. Because a corpse was involved, Stamey called in radio officer Howard Janney. Stamey and Janney found some empty beer cans and the unfinished handwritten lyrics to a song yet to be recorded in the Cadillac

The Cadillac Motor Car Division () is a division of the American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM) that designs and builds luxury vehicles. Its major markets are the United States, Canada, and China. Cadillac models are distributed i ...

convertible.

The town's coroner and mortician, Dr. Ivan Malinin, a Russian immigrant who barely spoke English, performed the autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

on Williams at the Tyree Funeral House. Malinin found hemorrhages in the heart and neck and pronounced the cause of death as "insufficiency of heright ventricle of heheart." Malinin also found that, apparently unrelated to his death, Williams had also been severely kicked in the groin during a fight in a Montgomery bar a few days earlier in which he had also injured his left arm, which had been subsequently bandaged. That evening, when the announcer at Canton announced Williams's death to the gathered crowd, they started laughing, thinking that it was just another excuse. After Hawkshaw Hawkins

Harold Franklin "Hawkshaw" Hawkins (December 22, 1921 – March 5, 1963) was an American country music singer popular from the 1950s into the early 1960s. He was known for his rich, smooth vocals and music drawn from blues, boogie and honky ...

and other performers started singing " I Saw the Light" as a tribute to Williams, the crowd, now realizing that he was indeed dead, followed them.

Controversy

The circumstances of Williams's death are still controversial. The result of the original autopsy indicated that Williams died of a heart attack. AuthorColin Escott

Colin Escott (born August 31, 1949) is a British music historian and author specializing in early U.S. rock and roll and country music. His works include a biography of Hank Williams, histories of Sun Records and The Grand Ole Opry, liner notes ...

concluded in his book ''Hank Williams: The Biography'' that the cause of death was heart failure caused by the combination of alcohol, morphine and chloral hydrate.

The investigating officer in Oak Hill declared later that Carr told him that he had pulled over at the Skyline Drive-In restaurant outside Oak Hill, and found Williams dead. Having interviewed Carr, the best that Peter Cooper of ''The Tennessean

''The Tennessean'' (known until 1972 as ''The Nashville Tennessean'') is a daily newspaper in Nashville, Tennessee. Its circulation area covers 39 counties in Middle Tennessee and eight counties in southern Kentucky. It is owned by Gannett, ...

'' could offer was that "somewhere between Mount Hope and Oak Hill", Carr noticed Williams' blanket had fallen off.

"I saw that the overcoat and blanket that had been covering Hank had slipped off," Carr told yet another reporter. "When I pulled it back up, I noticed that his hand was stiff and cold." When he tried to move his hands, they snapped back to the same position the hotel porters had arranged him in.

Carr told Cooper this happened at the side of the road six miles from Oak Hill, but investigating officer Howard Janney placed it in the Skyline Drive-In restaurant's parking lot, noting that Carr sought help from a Skyline employee. Another researcher decided it could have happened at any of the gas stations near Mount Hope.

Regardless, Carr said he next drove to "a cut-rate gas station". "I went inside and an older guy, around 50, came back out with me, looked in the back seat, and said, 'I think you've got a problem'. He was very kind, and said Oak Hill General Hospital was six miles on my left," and that would place him in Mount Hope.

They later drove to Oak Hill in search of a hospital, stopping at a Pure Oil station on the edge of town. Carr's account of how he discovered that Williams was dead outside Oak Hill is challenged by Dr. Leo Killorn, a Canadian intern at Beckley hospital, West Virginia, fifteen miles from Oak Hill, who claims that Carr drove up to the hospital and asked him to see Williams. Killorn stated that the fact that Carr told him it was Hank Williams caused him to remember the incident. Carr was exhausted and, according to the police reports, nervous enough to invite suspicion that foul play had been involved in Williams' death.

Funeral

The body was transported to Montgomery on January 2. It was placed in a silver coffin that was first shown at his mother's boarding house at 318 McDounough Street for two days. His funeral took place on January 4 at the Montgomery Auditorium, with his coffin placed on the flower-covered stage. During the ceremony,Ernest Tubb

Ernest Dale Tubb (February 9, 1914 – September 6, 1984), nicknamed the Texas Troubadour, was an American singer and songwriter and one of the pioneers of country music. His biggest career hit song, "Walking the Floor Over You" (1941), m ...

sang "Beyond the Sunset Beyond the Sunset may refer to:

* ''Beyond the Sunset'' (film), a 1989 Hong Kong film

* "Beyond the Sunset" (song), a 1950 song by Hank Williams

* '' Beyond the Sunset: The Romantic Collection'', a 2004 Blackmore's Night compilation album

{{d ...

" followed by Roy Acuff

Roy Claxton Acuff (September 15, 1903 – November 23, 1992) was an American country music singer, fiddler, and promoter. Known as the "King of Country Music", Acuff is often credited with moving the genre from its early string band and "hoedown ...

with " I Saw the Light" and Red Foley

Clyde Julian "Red" Foley (June 17, 1910 – September 19, 1968) was an American musician who made a major contribution to the growth of country music after World War II.

For more than two decades, Foley was one of the biggest stars of the gen ...

with "Peace in the Valley

"There'll Be Peace in the Valley for Me" is a 1939 song written by Thomas A. Dorsey, originally for Mahalia Jackson. It was copyrighted by Dorsey under this title on January 25, 1939, though it often appears informally as "Peace in the Valley".

...

."p.70/ref> An estimated 15,000 to 25,000 people passed by the silver coffin, and the auditorium was filled with 2,750 mourners. During the funeral four women fainted and a fifth was carried out of the auditorium in hysterics after falling at the foot of the casket. His funeral was said to have been far larger than any ever held for any other citizen of

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, and the largest event ever held in Montgomery, surpassing Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

' inauguration as President of the Confederacy

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confe ...

. Around two tons of flowers were sent. Williams's remains are interred at the Oakwood Annex in Montgomery.

Aftermath

The president ofMGM

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 a ...

told ''Billboard'' magazine that the company got only about five requests for pictures of Williams during the weeks prior to his death, but over 300 afterwards. The local record shops sold out of all of their records, and customers were asking for all records ever released by Williams. His final single released during his lifetime was ironically titled " I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive." "Your Cheatin' Heart

"Your Cheatin' Heart" is a song written and recorded by country music singer-songwriter Hank Williams in 1952. It is regarded as one of country's most important standards. Williams was inspired to write the song while driving with his fiancé ...

" was written and recorded in 1952 but released in 1953 after Williams's death. The song was number one on the country charts for six weeks. It provided the title for the 1964 biographic film of the same name, which starred George Hamilton. The Cadillac in which Williams was riding just before he died is now preserved at the Hank Williams Museum in Montgomery, Alabama.

Oklahoma investigation of Horace Marshall

As part of an investigation of illicit drug traffic conducted by the Oklahoma legislature, representative Robert Cunningham seized Marshall's files. During an initial hearing, Marshall insisted that he was a doctor, refusing to answer further statements. Marshall gave Cunningham a list of his patients, including Hank Williams. Defending his position, he claimed that Williams possibly committed suicide. Marshall stated that Williams told him that he had decided to "destroy the Hank Williams that was making the money they were getting". He attributed the decision to Williams' declining career: "Most of his bookings were of the honky-tonk beer joint variety that he simply hated. If he came to this conclusion (of suicide), he still had enough prestige left as a star to make a first-class production of it ... whereas, six months from now, unless he pulled himself back up into some high-class bookings, he might have been playing for nickels and dimes on skid row."

On March 10, Marshall was called again to testify. He acknowledged that in previous testimony he had falsely claimed to be a physician. Representative Cunningham presented the committee a telegram from Marshall's seized files, directed to the estate of Hank Williams for $736.39, and stated that the committee was evaluating the revocation of Marshall's parole. On March 12, 1953, Billie Jean Jones appeared before the Oklahoma committee. She stated that she received after Williams' death a bill for $800 from Marshall for the treatment. Jones refused to pay, and further stated that Marshall later intended to convince her to pay him by assuring that he would "pave her the way to collect her husband's state". Jones declared "I have never accepted the report that my husband died of a heart attack."

On March 19, Marshall declared that he felt Williams was depressed and committed suicide by taking a higher dose of the drugs he had prescribed. Marshall admitted that he had also prescribed chloral hydrate to his recently deceased wife, Faye, as a headache medicine. He denied any responsibility in both deaths. On March 21, Robert Travis of the State Crime Bureau determined that Marshall's handwriting corresponded to that of Dr. Cecil W. Lemmon on six prescriptions written for Williams. The same day, the District Attorney's office declared that after a new review of the autopsy report of Faye Marshall, toxicological and microscopic tests confirmed that her death on March 3 was not related to the medication prescribed by her husband.

As part of an investigation of illicit drug traffic conducted by the Oklahoma legislature, representative Robert Cunningham seized Marshall's files. During an initial hearing, Marshall insisted that he was a doctor, refusing to answer further statements. Marshall gave Cunningham a list of his patients, including Hank Williams. Defending his position, he claimed that Williams possibly committed suicide. Marshall stated that Williams told him that he had decided to "destroy the Hank Williams that was making the money they were getting". He attributed the decision to Williams' declining career: "Most of his bookings were of the honky-tonk beer joint variety that he simply hated. If he came to this conclusion (of suicide), he still had enough prestige left as a star to make a first-class production of it ... whereas, six months from now, unless he pulled himself back up into some high-class bookings, he might have been playing for nickels and dimes on skid row."

On March 10, Marshall was called again to testify. He acknowledged that in previous testimony he had falsely claimed to be a physician. Representative Cunningham presented the committee a telegram from Marshall's seized files, directed to the estate of Hank Williams for $736.39, and stated that the committee was evaluating the revocation of Marshall's parole. On March 12, 1953, Billie Jean Jones appeared before the Oklahoma committee. She stated that she received after Williams' death a bill for $800 from Marshall for the treatment. Jones refused to pay, and further stated that Marshall later intended to convince her to pay him by assuring that he would "pave her the way to collect her husband's state". Jones declared "I have never accepted the report that my husband died of a heart attack."

On March 19, Marshall declared that he felt Williams was depressed and committed suicide by taking a higher dose of the drugs he had prescribed. Marshall admitted that he had also prescribed chloral hydrate to his recently deceased wife, Faye, as a headache medicine. He denied any responsibility in both deaths. On March 21, Robert Travis of the State Crime Bureau determined that Marshall's handwriting corresponded to that of Dr. Cecil W. Lemmon on six prescriptions written for Williams. The same day, the District Attorney's office declared that after a new review of the autopsy report of Faye Marshall, toxicological and microscopic tests confirmed that her death on March 3 was not related to the medication prescribed by her husband. Oklahoma Governor

The governor of Oklahoma is the head of government of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Under the Oklahoma Constitution, the governor serves as the head of the Oklahoma executive branch, of the government of Oklahoma. The governor is the ''ex officio ...

Johnston Murray

Johnston Murray (July 21, 1902 – April 16, 1974) was an American lawyer, politician, and the 14th governor of Oklahoma from 1951 to 1955. He was a member of the Democratic Party.

Murray was the first Native American to be elected as governor ...

revoked the parole of Horace Raphol "Toby" Marshall, who returned to prison to complete his forgery sentence.

References

Cited texts

* * * * * * * * * * * {{Hank Williams 1953 in American music January 1953 events in the United States Williams, Hank Williams, Hank Williams, Hank 1953 in West Virginia Hank Williams