Death of Franklin Pierce on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

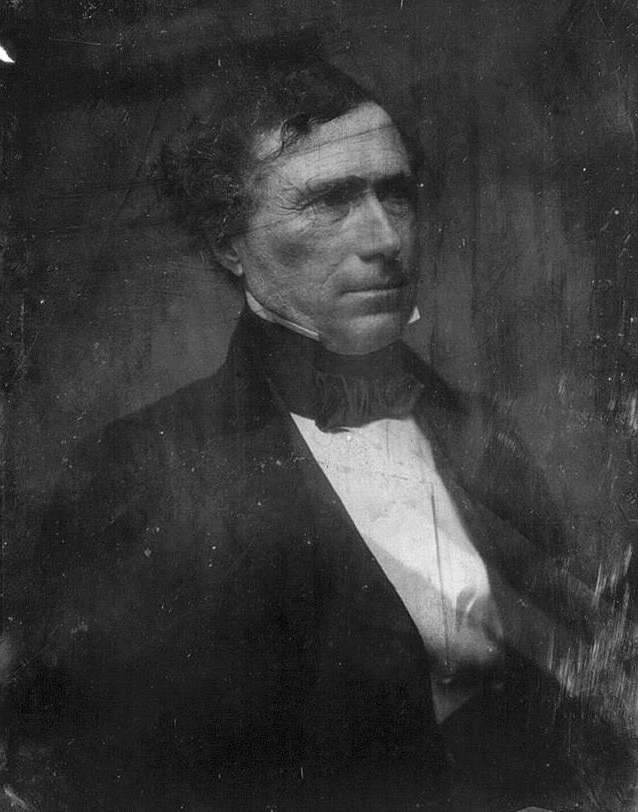

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th

In fall 1820, Pierce entered Bowdoin College in

In fall 1820, Pierce entered Bowdoin College in

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton (March 12, 1806 – December 2, 1863), a daughter of

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton (March 12, 1806 – December 2, 1863), a daughter of

The resignation in May 1836 of Senator Isaac Hill, who had been elected governor of New Hampshire, left a short-term opening to be filled by the state legislature, and with Hill's term as senator due to expire in March 1837, the legislature also had to fill the six-year term to follow. Pierce's candidacy for the Senate was championed by state Representative John P. Hale, a fellow Athenian at Bowdoin. After much debate, the legislature chose John Page to fill the rest of Hill's term. In December 1836, Pierce was elected to the full term, to commence in March 1837, and at age 32, was at the time one of the youngest members in Senate history. The election came at a difficult time for Pierce, as his father, sister, and brother were all seriously ill, while his wife also continued to suffer from chronic poor health. As senator, he was able to help his old friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who often struggled financially, procuring for him a sinecure as measurer of coal and salt at the Boston Customs House that allowed the author time to continue writing.

Pierce voted the party line on most issues and was an able senator, but not an eminent one; he was overshadowed by the

The resignation in May 1836 of Senator Isaac Hill, who had been elected governor of New Hampshire, left a short-term opening to be filled by the state legislature, and with Hill's term as senator due to expire in March 1837, the legislature also had to fill the six-year term to follow. Pierce's candidacy for the Senate was championed by state Representative John P. Hale, a fellow Athenian at Bowdoin. After much debate, the legislature chose John Page to fill the rest of Hill's term. In December 1836, Pierce was elected to the full term, to commence in March 1837, and at age 32, was at the time one of the youngest members in Senate history. The election came at a difficult time for Pierce, as his father, sister, and brother were all seriously ill, while his wife also continued to suffer from chronic poor health. As senator, he was able to help his old friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who often struggled financially, procuring for him a sinecure as measurer of coal and salt at the Boston Customs House that allowed the author time to continue writing.

Pierce voted the party line on most issues and was an able senator, but not an eminent one; he was overshadowed by the

Despite his resignation from the Senate, Pierce had no intention of leaving public life. The move to Concord had given him more opportunities for cases, and allowed Jane Pierce a more robust community life. Jane had remained in Concord with her young son Frank and her newborn Benjamin for the latter part of Pierce's senate term, and this separation had taken a toll on the family. Pierce, meanwhile, had begun a demanding but lucrative law partnership with

Despite his resignation from the Senate, Pierce had no intention of leaving public life. The move to Concord had given him more opportunities for cases, and allowed Jane Pierce a more robust community life. Jane had remained in Concord with her young son Frank and her newborn Benjamin for the latter part of Pierce's senate term, and this separation had taken a toll on the family. Pierce, meanwhile, had begun a demanding but lucrative law partnership with

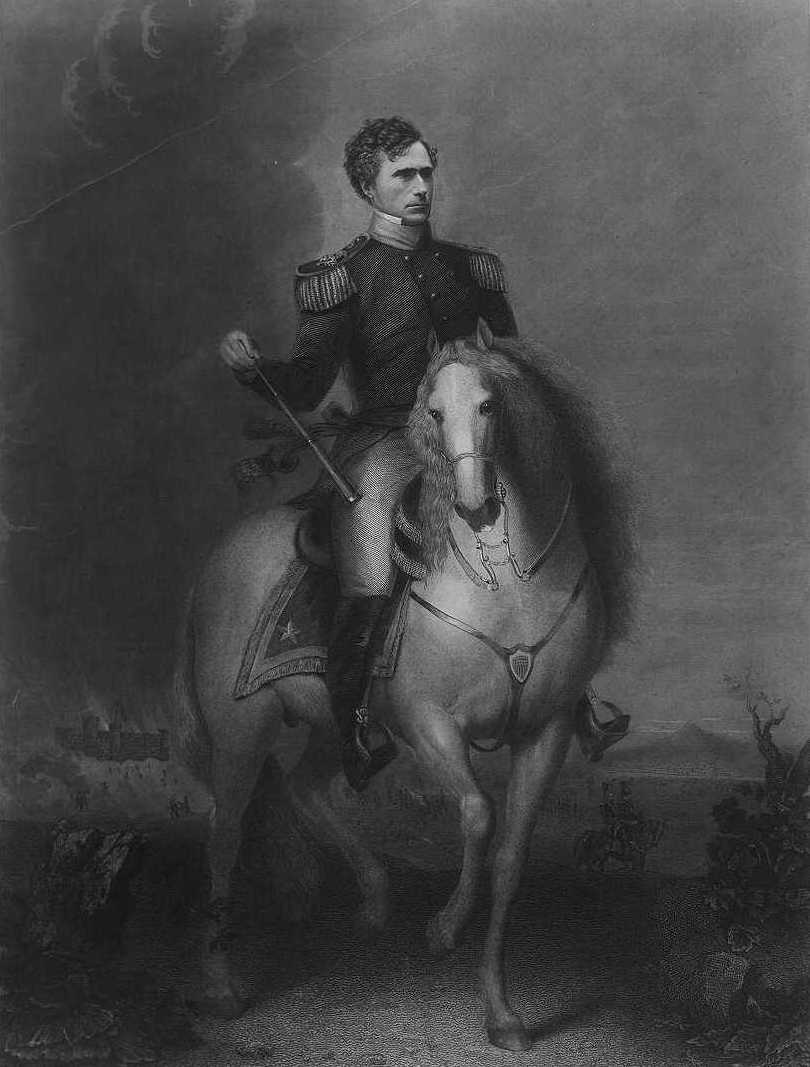

Active military service was a long-held dream for Pierce, who had admired his father's and brothers' service in his youth, particularly his older brother Benjamin's, as well as that of

Active military service was a long-held dream for Pierce, who had admired his father's and brothers' service in his youth, particularly his older brother Benjamin's, as well as that of  On March 3, 1847, Pierce was promoted to

On March 3, 1847, Pierce was promoted to

Returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law practice; in one notable case he defended the religious liberty of the Shakers, the insular sect threatened with legal action over accusations of abuse. His role as a party leader, however, continued to take up most of his attention. He continued to wrangle with Senator Hale, who was anti-slavery and had opposed the war, stances that Pierce regarded as needless agitation.

The large Mexican Cession of land divided the United States politically, with many in the North insisting that slavery not be allowed there (and offering the

Returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law practice; in one notable case he defended the religious liberty of the Shakers, the insular sect threatened with legal action over accusations of abuse. His role as a party leader, however, continued to take up most of his attention. He continued to wrangle with Senator Hale, who was anti-slavery and had opposed the war, stances that Pierce regarded as needless agitation.

The large Mexican Cession of land divided the United States politically, with many in the North insisting that slavery not be allowed there (and offering the

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided by the slavery issue, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party with Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned. It was widely expected that the

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided by the slavery issue, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party with Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned. It was widely expected that the  The Whig candidate was General Scott, Pierce's commander in Mexico; his running mate was

The Whig candidate was General Scott, Pierce's commander in Mexico; his running mate was  Pierce kept quiet so as not to upset his party's delicate unity, and allowed his allies to run the campaign. It was the custom at the time for candidates to not appear to seek the office, and he did no personal campaigning. Pierce's opponents caricatured him as an anti-Catholic coward and alcoholic ("the hero of many a well-fought bottle"). Scott, meanwhile, drew weak support from the Whigs, who were torn by their pro-Compromise platform and found him to be an abysmal, gaffe-prone public speaker. The Democrats were confident: a popular slogan was that the Democrats "will ''pierce'' their enemies in 1852 as they ''poked'' Polked.html" ;"title="James_K._Polk.html" ;"title="hat is, James K. Polk">Polked">James_K._Polk.html" ;"title="hat is, James K. Polk">Polkedthem in 1844." This proved to be true, as Scott won only Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts and Vermont, finishing with 42 electoral votes to Pierce's 254. With 3.2 million votes cast, Pierce won the popular vote with 50.9 to 44.1 percent. A sizable block of Free Soilers broke for Pierce's in-state rival, Hale, who won 4.9 percent of the popular vote. The Democrats took large majorities in Congress.

Pierce kept quiet so as not to upset his party's delicate unity, and allowed his allies to run the campaign. It was the custom at the time for candidates to not appear to seek the office, and he did no personal campaigning. Pierce's opponents caricatured him as an anti-Catholic coward and alcoholic ("the hero of many a well-fought bottle"). Scott, meanwhile, drew weak support from the Whigs, who were torn by their pro-Compromise platform and found him to be an abysmal, gaffe-prone public speaker. The Democrats were confident: a popular slogan was that the Democrats "will ''pierce'' their enemies in 1852 as they ''poked'' Polked.html" ;"title="James_K._Polk.html" ;"title="hat is, James K. Polk">Polked">James_K._Polk.html" ;"title="hat is, James K. Polk">Polkedthem in 1844." This proved to be true, as Scott won only Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts and Vermont, finishing with 42 electoral votes to Pierce's 254. With 3.2 million votes cast, Pierce won the popular vote with 50.9 to 44.1 percent. A sizable block of Free Soilers broke for Pierce's in-state rival, Hale, who won 4.9 percent of the popular vote. The Democrats took large majorities in Congress.

Pierce began his presidency in mourning. Weeks after his election, on January 6, 1853, the President-elect and his family were traveling from Boston by train when their car derailed and rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Both Franklin and Jane Pierce survived, but their only remaining son, 11-year-old Benjamin, was crushed to death in the wreckage, his body nearly decapitated. Pierce was not able to hide the gruesome sight from his wife. They both suffered severe depression afterward, which likely affected Pierce's performance as president. Jane Pierce wondered if the train accident was divine punishment for her husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office. She wrote a lengthy letter of apology to "Benny" for her failings as a mother. She avoided social functions for much of her first two years as First Lady, making her public debut in that role to great sympathy at the annual public reception held at the White House on New Year's Day, 1855.

When Franklin Pierce departed New Hampshire for the inauguration, Jane Pierce chose not to accompany him. Pierce, then the youngest man to be elected president, chose to affirm his oath of office on a law book rather than swear it on a Bible, as all his predecessors except John Quincy Adams, who swore on a book of law, had done. He was the first president to deliver his inaugural address from memory. In the address he hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and urged a vigorous assertion of U.S. interests in its foreign relations, including the "eminently important" acquisition of new territories. "The policy of my Administration", said the new president, "will not be deterred by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion." Avoiding the word "slavery", he emphasized his desire to put the "important subject" to rest and maintain a peaceful union. He alluded to his own personal tragedy, telling the crowd, "You have summoned me in my weakness, you must sustain me by your strength."

Pierce began his presidency in mourning. Weeks after his election, on January 6, 1853, the President-elect and his family were traveling from Boston by train when their car derailed and rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Both Franklin and Jane Pierce survived, but their only remaining son, 11-year-old Benjamin, was crushed to death in the wreckage, his body nearly decapitated. Pierce was not able to hide the gruesome sight from his wife. They both suffered severe depression afterward, which likely affected Pierce's performance as president. Jane Pierce wondered if the train accident was divine punishment for her husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office. She wrote a lengthy letter of apology to "Benny" for her failings as a mother. She avoided social functions for much of her first two years as First Lady, making her public debut in that role to great sympathy at the annual public reception held at the White House on New Year's Day, 1855.

When Franklin Pierce departed New Hampshire for the inauguration, Jane Pierce chose not to accompany him. Pierce, then the youngest man to be elected president, chose to affirm his oath of office on a law book rather than swear it on a Bible, as all his predecessors except John Quincy Adams, who swore on a book of law, had done. He was the first president to deliver his inaugural address from memory. In the address he hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and urged a vigorous assertion of U.S. interests in its foreign relations, including the "eminently important" acquisition of new territories. "The policy of my Administration", said the new president, "will not be deterred by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion." Avoiding the word "slavery", he emphasized his desire to put the "important subject" to rest and maintain a peaceful union. He alluded to his own personal tragedy, telling the crowd, "You have summoned me in my weakness, you must sustain me by your strength."

Buchanan had urged Pierce to consult Vice President-elect King in selecting the Cabinet, but Pierce did not do so—Pierce and King had not communicated since they had been selected as candidates in June 1852. By the start of 1853, King was severely ill with tuberculosis, and went to Cuba to recuperate. His condition deteriorated, and Congress passed a special law, allowing him to be sworn in before the American consul in Havana on March 24. Wanting to die at home, he returned to his plantation in Alabama on April 17 and died the next day. The office of vice president remained vacant for the remainder of Pierce's term, as the Constitution then had no provision for filling the vacancy. This extended vacancy meant that for nearly the entirety of Pierce's presidency the

Buchanan had urged Pierce to consult Vice President-elect King in selecting the Cabinet, but Pierce did not do so—Pierce and King had not communicated since they had been selected as candidates in June 1852. By the start of 1853, King was severely ill with tuberculosis, and went to Cuba to recuperate. His condition deteriorated, and Congress passed a special law, allowing him to be sworn in before the American consul in Havana on March 24. Wanting to die at home, he returned to his plantation in Alabama on April 17 and died the next day. The office of vice president remained vacant for the remainder of Pierce's term, as the Constitution then had no provision for filling the vacancy. This extended vacancy meant that for nearly the entirety of Pierce's presidency the

Pierce charged

Pierce charged

Pierce fully expected to be renominated by the Democrats. In reality, his chances of winning the nomination (let alone the general election) were slim. The administration was widely disliked in the North for its position on the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and Democratic leaders were aware of Pierce's electoral vulnerability. Nevertheless, his supporters began to plan for an alliance with Douglas to deny James Buchanan the nomination. Buchanan had solid political connections and had been safely overseas through most of Pierce's term, leaving him untainted by the Kansas debacle.

When balloting began on June 5 at the convention in

Pierce fully expected to be renominated by the Democrats. In reality, his chances of winning the nomination (let alone the general election) were slim. The administration was widely disliked in the North for its position on the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and Democratic leaders were aware of Pierce's electoral vulnerability. Nevertheless, his supporters began to plan for an alliance with Douglas to deny James Buchanan the nomination. Buchanan had solid political connections and had been safely overseas through most of Pierce's term, leaving him untainted by the Kansas debacle.

When balloting began on June 5 at the convention in

After leaving the White House, the Pierces remained in Washington for more than two months, staying with former Secretary of State William L. Marcy. Buchanan altered course from the Pierce administration, replacing all his appointees. The Pierces eventually moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where Pierce had begun to speculate in property. Seeking warmer weather, he and Jane spent the next three years traveling, beginning with a stay in Madeira and followed by tours of Europe and the

After leaving the White House, the Pierces remained in Washington for more than two months, staying with former Secretary of State William L. Marcy. Buchanan altered course from the Pierce administration, replacing all his appointees. The Pierces eventually moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where Pierce had begun to speculate in property. Seeking warmer weather, he and Jane spent the next three years traveling, beginning with a stay in Madeira and followed by tours of Europe and the

online

* * * pp 345–96 * * Williamson, Richard Joseph. "Friendship, politics, and the literary imagination: The impact of Franklin Pierce on Hawthorne's work" (PhD dissertation, University of North Texas, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996. 9638512).

White House biography

* * * *

Essays on Franklin Pierce and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady

from the

Franklin Pierce: A Resource Guide

from the Library of Congress

Franklin Pierce Bicentennial

"Life Portrait of Franklin Pierce"

from C-SPAN's '' American Presidents: Life Portraits'', June 14, 1999

Franklin Pierce Personal Manuscripts

* ttp://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2018/01/04/franklin-pierce-train-wreck/ 2018 article on the 14th US President {{DEFAULTSORT:Pierce, Franklin Franklin Pierce family 1804 births 1869 deaths 19th-century American Episcopalians 19th-century American politicians 19th-century presidents of the United States Alcohol-related deaths in New Hampshire American military personnel of the Mexican–American War American people of English descent Bowdoin College alumni Burials in New Hampshire Deaths from cirrhosis Democratic Party presidents of the United States Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees Democratic Party United States senators from New Hampshire 1850s in the United States Jacksonian members of the United States House of Representatives from New Hampshire Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 Military personnel from New Hampshire New Hampshire lawyers Northampton Law School alumni People from Hillsborough, New Hampshire Phillips Exeter Academy alumni Presidents of the United States Speakers of the New Hampshire House of Representatives Democratic Party members of the New Hampshire House of Representatives United States Army generals United States Attorneys for the District of New Hampshire Candidates in the 1852 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1856 United States presidential election American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity. He alienated anti-slavery groups by signing the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also kno ...

. Conflict between North and South continued after Pierce's presidency, and, after Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

was elected president in 1860, Southern states seceded, resulting in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

Pierce was born in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from 1833 until his election to the Senate, where he served from 1837 until his resignation in 1842. His private law practice was a success, and he was appointed New Hampshire's U.S. Attorney in 1845. He took part in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

as a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the Army. Democrats saw him as a compromise candidate uniting Northern and Southern interests, and nominated him for president on the 49th ballot at the 1852 Democratic National Convention

The 1852 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 1 to June 5 in Baltimore, Maryland. It was held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 electi ...

. He and running mate William R. King easily defeated the Whig Party ticket of Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

and William A. Graham in the 1852 presidential election.

As president, Pierce attempted to enforce neutral standards for civil service while also satisfying the Democratic Party's diverse elements with patronage, an effort that largely failed and turned many in his party against him. He was a Young America expansionist who signed the Gadsden Purchase of land from Mexico and led a failed attempt to acquire Cuba from Spain. He signed trade treaties with Britain and Japan and his Cabinet reformed its departments and improved accountability, but political strife during his presidency overshadowed these successes. His popularity declined sharply in the Northern states after he supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which nullified the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

, while many Southern whites continued to support him. The act's passage led to violent conflict

War is an intense armed conflict between State (polity), states, governments, Society, societies, or paramilitary groups such as Mercenary, mercenaries, Insurgency, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violenc ...

over expanding slavery in the American West. Pierce's administration was further damaged when several of his diplomats issued the Ostend Manifesto

The Ostend Manifesto, also known as the Ostend Circular, was a document written in 1854 that described the rationale for the United States to purchase Cuba from Spain while implying that the U.S. should declare war if Spain refused. Cuba's annex ...

calling for the annexation of Cuba, a document that was roundly criticized. He fully expected the Democrats to renominate him in the 1856 presidential election, but they abandoned him and his bid failed. His reputation in the North suffered further during the American Civil War as he became a vocal critic of President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

Pierce was popular and outgoing, but his family life was difficult; his three children died young and his wife, Jane Pierce

Jane Means Pierce (née Appleton; March 12, 1806 – December 2, 1863) was the wife of Franklin Pierce and the first lady of the United States from 1853 to 1857. She married Franklin Pierce, then a Congressman, in 1834 despite her family's misgiv ...

, suffered from illness and depression for much of her life. Their last surviving son was killed in a train accident while the family was traveling, shortly before Pierce's inauguration. A heavy drinker for much of his life, Pierce died in 1869 of cirrhosis of the liver

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease, is the impaired liver function caused by the formation of scar tissue known as fibrosis due to damage caused by liver disease. Damage causes tissue repai ...

. Historians and scholars generally rank Pierce as one of the worst

The Worst or Worst may refer to:

* ''The Worst'', a 1997 album by Sarcófago, or its title track

* ''The Worst'', a 2000 album by Tech N9ne, or its title track

* ''The Worst'', a 2004 EP by Lower Class Brats, or its title track

* "The Worst" (On ...

and least memorable U.S. presidents.

Early life and family

Childhood and education

Franklin Pierce was born on November 23, 1804, in a log cabin inHillsborough, New Hampshire

Hillsborough, frequently spelled Hillsboro, is a town in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 5,939 at the 2020 census. The town is home to Fox State Forest and part of Low State Forest.

The main village of the t ...

. He was a sixth-generation descendant of Thomas Pierce, who had moved to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from Norwich, Norfolk

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, w ...

, England in about 1634. His father Benjamin was a lieutenant in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

who moved from Chelmsford, Massachusetts

Chelmsford () is a town in Massachusetts that was established in 1655. It is located northwest of Boston. The Chelmsford militia played a role in the American Revolution at the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Bunker Hill. ...

to Hillsborough after the war, purchasing of land. Pierce was the fifth of eight children born to Benjamin and his second wife Anna Kendrick; his first wife Elizabeth Andrews died in childbirth, leaving a daughter. Benjamin was a prominent Democratic-Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

state legislator, farmer, and tavern-keeper. During Pierce's childhood, his father was deeply involved in state politics, while two of his older brothers fought in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

; public affairs and the military were thus a major influence in his early life.

Pierce's father ensured that his sons were educated, and placed Pierce in a school at Hillsborough Center in childhood and sent him to the town school in Hancock Hancock may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Hancock, Iowa

* Hancock, Maine

* Hancock, Maryland

* Hancock, Massachusetts

* Hancock, Michigan

* Hancock, Minnesota

* Hancock, Missouri

* Hancock, New Hampshire

** Hancock (CDP), New Hampshir ...

at age 12. Not fond of schooling, Pierce grew homesick and walked back to his home one Sunday. His father fed him dinner and drove him part of the distance back to school before ordering him to walk the rest of the way in a thunderstorm. Pierce later cited this moment as "the turning-point in my life". Later that year, he transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy to prepare for college. By this time, he had built a reputation as a charming student, sometimes prone to misbehavior.

In fall 1820, Pierce entered Bowdoin College in

In fall 1820, Pierce entered Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine

Brunswick is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The population was 21,756 at the 2020 United States Census. Part of the Portland-South Portland-Biddeford metropolitan area, Brunswick is home to Bowdoin College, the Bowdoin Intern ...

, one of 19 freshmen. He joined the Athenian Society, a progressive literary society, alongside Jonathan Cilley

Jonathan Cilley (July 2, 1802 – February 24, 1838) was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maine. He served part of one term in the 25th Congress, and died as the result of a wound sustained in a duel with another Congressman, ...

(later elected to Congress) and Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

, with whom he formed lasting friendships. He was the last in his class after two years, but he worked hard to improve his grades and graduated in fifth place in 1824 in a graduating class of 14. John P. Hale enrolled at Bowdoin in Pierce's junior year; he became a political ally of Pierce's and then his rival. Pierce organized and led an unofficial militia company called the Bowdoin Cadets during his junior year, which included Cilley and Hawthorne. The unit performed drill on campus near the president's house, until the noise caused him to demand that it halt. The students rebelled and went on strike, an event that Pierce was suspected of leading. During his final year at Bowdoin, he spent several months teaching at Hebron Academy

Hebron Academy, founded in 1804, is a small, independent, college preparatory boarding and day school for boys and girls in grades six through postgraduate in Hebron, Maine.

History

Hebron Academy is one of the nation's oldest endowed preparatory ...

in rural Hebron, Maine

Hebron is a town in Oxford County, Maine, United States. Hebron is included in the Lewiston- Auburn, Maine metropolitan New England city and town area. The town's history has always been interconnected with Hebron Academy, a co-ed college prepa ...

, where he earned his first salary and his students included future Congressman John J. Perry.

Pierce read law briefly with former New Hampshire Governor Levi Woodbury

Levi Woodbury (December 22, 1789September 4, 1851) was an American attorney, jurist, and Democratic politician from New Hampshire. During a four-decade career in public office, Woodbury served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U ...

, a family friend in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He then spent a semester at Northampton Law School in Northampton, Massachusetts, followed by a period of study in 1826 and 1827 under Judge Edmund Parker in Amherst, New Hampshire

Amherst is a town in Hillsborough County in the state of New Hampshire, United States. The population was 11,753 at the 2020 census. Amherst is home to Ponemah Bog Wildlife Sanctuary, Hodgman State Forest, the Joe English Reservation and Baboos ...

. He was admitted to the New Hampshire bar in late 1827 and began to practice in Hillsborough. He lost his first case, but soon proved capable as a lawyer. Despite never being a legal scholar, his memory for names and faces served him well, as did his personal charm and deep voice. In Hillsborough, his law partner was Albert Baker, who had studied law under Pierce and was the brother of Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy (July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author who founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, in New England in 1879. She also founded ''The Christian Science Monitor'', a Pulitzer Prize-winning se ...

.

State politics

By 1824, New Hampshire was a hotbed of partisanship, with figures such as Woodbury andIsaac Hill

Isaac Hill (April 6, 1788March 22, 1851) was an American politician, journalist, political commentator and newspaper editor who was a United States senator and the 16th governor of New Hampshire, serving two consecutive terms.

Hill was born on ...

laying the groundwork for a party of Democrats in support of General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

. They opposed the established Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

(and their successors, the National Republicans

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John Q ...

), who were led by sitting President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

. The work of the New Hampshire Democratic Party came to fruition in March 1827, when their pro-Jackson nominee, Benjamin Pierce, won the support of the pro-Adams faction and was elected governor of New Hampshire essentially unopposed. While the younger Pierce had set out to build a career as an attorney, he was fully drawn into the realm of politics as the 1828 presidential election between Adams and Jackson approached. In the state elections held in March 1828, the Adams faction withdrew their support of Benjamin Pierce, voting him out of office, but Franklin Pierce won his first election, as Hillsborough town moderator

Town meeting is a form of local government in which most or all of the members of a community are eligible to legislate policy and budgets for local government. It is a town- or city-level meeting in which decisions are made, in contrast with ...

, a position to which he would be elected for six consecutive years.

Pierce actively campaigned in his district on behalf of Jackson, who carried both the district and the nation by large margins in the November 1828 election, even though he lost New Hampshire. The outcome further strengthened the Democratic Party, and Pierce won his first legislative seat the following year, representing Hillsborough in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. Pierce's father, meanwhile, was elected again as governor, retiring after that term. The younger Pierce was appointed as chairman of the House Education Committee in 1829 and the Committee on Towns the following year. By 1831 the Democrats held a legislative majority, and Pierce was elected Speaker of the House. The young Speaker used his platform to oppose the expansion of banking, protect the state militia, and offer support to the national Democrats and Jackson's re-election effort. At 27, he was a star of the New Hampshire Democratic Party. Though attaining early political and professional success, in his personal letters he continued to lament his bachelorhood and yearned for a life beyond Hillsborough.

Like all white males in New Hampshire between the ages of 18 and 45, Pierce was a member of the state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

, and was appointed aide de camp to Governor Samuel Dinsmoor in 1831. He remained in the militia until 1847, and attained the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

before becoming a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. Interested in revitalizing and reforming the state militias, which had become increasingly dormant during the years of peace following the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, Pierce worked with Alden Partridge

Alden Partridge, (February 12, 1785 - January 17, 1854) was an American author, legislator, officer, surveyor, an early superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York and a controversial pioneer in U.S. military edu ...

, president of Norwich University, a military college in Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

, and Truman B. Ransom and Alonzo Jackman, Norwich faculty members and militia officers, to increase recruiting efforts and improve training and readiness. Pierce served as a Norwich University trustee from 1841 to 1859, and received the honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

of LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

from Norwich in 1853.

In late 1832, the Democratic Party convention nominated Pierce for one of New Hampshire's five seats in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. This was tantamount to election

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinati ...

for the young Democrat, as the National Republicans had faded as a political force, while the Whigs had not yet begun to attract a large following. Democratic strength in New Hampshire was also bolstered by Jackson's landslide re-election that year. New Hampshire had been a marginal state politically, but from 1832 through the mid-1850s became the most reliably Democratic state in the Northern United States, boosting Pierce's political career. Pierce's term began in March 1833, but he would not be sworn in until Congress met in December, and his attention was elsewhere. He had recently become engaged and bought his first house in Hillsborough. Franklin and Benjamin Pierce were among the prominent citizens who welcomed President Jackson to the state on his visit in mid-1833.

Marriage and children

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton (March 12, 1806 – December 2, 1863), a daughter of

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton (March 12, 1806 – December 2, 1863), a daughter of Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

minister Jesse Appleton and Elizabeth Means. The Appletons were prominent Whigs, in contrast with the Pierces' Democratic affiliation. Jane Pierce was shy, devoutly religious, and pro-temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

, encouraging Pierce to abstain from alcohol. She was somewhat gaunt, and constantly ill from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

and psychological ailments. She abhorred politics and especially disliked Washington, DC, creating a tension that would continue throughout Pierce's political ascent.

Jane Pierce disliked Hillsborough as well, and in 1838, the Pierces relocated to the state capital, Concord, New Hampshire. They had three sons, all of whom died in childhood. Franklin Jr. (February 2–5, 1836) died in infancy, while Frank Robert (August 27, 1839 – November 14, 1843) died at the age of four from epidemic typhus. Benjamin (April 13, 1841 – January 6, 1853) died at the age of 11 in a train accident.

Congressional career

U.S. House of Representatives

Pierce departed in November 1833 for Washington, D.C., where theTwenty-third United States Congress

The 23rd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1833 ...

convened its regular session on December 2. Jackson's second term was under way, and the House of Representatives had a strong Democratic majority, whose primary focus was to prevent the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ...

from being rechartered. The Democrats, including Pierce, defeated proposals supported by the newly formed Whig Party, and the bank's charter expired. Pierce broke from his party on occasion, opposing Democratic bills to fund internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

with federal money. He saw both the bank and infrastructure spending as unconstitutional, with internal improvements the responsibility of the states. Pierce's first term was fairly uneventful from a legislative standpoint, and he was easily re-elected in March 1835. When not in Washington, he attended to his law practice, and in December 1835 returned to the capital for the Twenty-fourth Congress

The 24th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1835, ...

.

As abolitionism grew more vocal in the mid-1830s, Congress was inundated with petitions from anti-slavery groups seeking legislation to restrict slavery in the United States. From the beginning, Pierce found the abolitionists' "agitation" to be an annoyance, and saw federal action against slavery as an infringement on southern states' rights, even though he was morally opposed to slavery itself. He was also frustrated with the "religious bigotry" of abolitionists, who cast their political opponents as sinners. "I consider slavery a social and political evil," Pierce said, "and most sincerely wish that it had no existence upon the face of the earth." Still, he wrote in December 1835, "One thing must be perfectly apparent to every intelligent man. This abolition movement must be crushed or there is an end to the Union." After the Civil War, Pierce believed that if the North had not aggressively agitated against Southern slavery, the South would have eventually ended slavery on its own and that the conflict had been "brought upon the nation by fanatics on both sides".

When Rep. James Henry Hammond

James Henry Hammond (November 15, 1807 – November 13, 1864) was an attorney, politician, and planter from South Carolina. He served as a United States representative from 1835 to 1836, the 60th Governor of South Carolina from 1842 to 1844, and ...

of South Carolina looked to prevent anti-slavery petitions from reaching the House floor, however, Pierce sided with the abolitionists' right to petition. Nevertheless, Pierce supported what came to be known as the gag rule

A gag rule is a rule that limits or forbids the raising, consideration, or discussion of a particular topic, often but not always by members of a legislative or decision-making body. A famous example of gag rules is the series of rules concernin ...

, which allowed for petitions to be received, but not read or considered. This passed the House in 1836. He was attacked by the New Hampshire anti-slavery ''Herald of Freedom'' as a "doughface

The term doughface originally referred to an actual mask made of dough, but came to be used in a disparaging context for someone, especially a politician, who is perceived to be pliable and moldable. In the 1847 ''Webster's Dictionary'' ''doughfac ...

", which had the dual meaning of "craven-spirited man" and "northerner with southern sympathies". Pierce had stated that not one in 500 New Hampshirites were abolitionists; the ''Herald of Freedom'' article added up the number of signatures on petitions from that state, divided by the number of residents according to the 1830 census, and suggested the actual number was one-in-33. Pierce was outraged when South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun read the article on the Senate floor as "proof" that New Hampshire was a hotbed of abolitionism. Calhoun apologized after Pierce replied to him in a speech which stated that most signatories were women and children, who could not vote, which therefore cast doubt on the one-in-33 figure.

U.S. Senate

The resignation in May 1836 of Senator Isaac Hill, who had been elected governor of New Hampshire, left a short-term opening to be filled by the state legislature, and with Hill's term as senator due to expire in March 1837, the legislature also had to fill the six-year term to follow. Pierce's candidacy for the Senate was championed by state Representative John P. Hale, a fellow Athenian at Bowdoin. After much debate, the legislature chose John Page to fill the rest of Hill's term. In December 1836, Pierce was elected to the full term, to commence in March 1837, and at age 32, was at the time one of the youngest members in Senate history. The election came at a difficult time for Pierce, as his father, sister, and brother were all seriously ill, while his wife also continued to suffer from chronic poor health. As senator, he was able to help his old friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who often struggled financially, procuring for him a sinecure as measurer of coal and salt at the Boston Customs House that allowed the author time to continue writing.

Pierce voted the party line on most issues and was an able senator, but not an eminent one; he was overshadowed by the

The resignation in May 1836 of Senator Isaac Hill, who had been elected governor of New Hampshire, left a short-term opening to be filled by the state legislature, and with Hill's term as senator due to expire in March 1837, the legislature also had to fill the six-year term to follow. Pierce's candidacy for the Senate was championed by state Representative John P. Hale, a fellow Athenian at Bowdoin. After much debate, the legislature chose John Page to fill the rest of Hill's term. In December 1836, Pierce was elected to the full term, to commence in March 1837, and at age 32, was at the time one of the youngest members in Senate history. The election came at a difficult time for Pierce, as his father, sister, and brother were all seriously ill, while his wife also continued to suffer from chronic poor health. As senator, he was able to help his old friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who often struggled financially, procuring for him a sinecure as measurer of coal and salt at the Boston Customs House that allowed the author time to continue writing.

Pierce voted the party line on most issues and was an able senator, but not an eminent one; he was overshadowed by the Great Triumvirate

In U.S. politics, the Great Triumvirate (known also as the Immortal Trio) refers to a triumvirate of three statesmen who dominated American politics for much of the first half of the 19th century, namely Henry Clay of Kentucky, Daniel Webste ...

of Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

, who dominated the Senate. Pierce entered the Senate at a time of economic crisis, as the Panic of 1837 had begun. He considered the depression a result of the banking system's rapid growth, amidst "the extravagance of overtrading and the wilderness of speculation". So that federal money would not support speculative bank loans, he supported newly elected Democratic president Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

and his plan to create an independent treasury

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, ...

, a proposal which split the Democratic Party. Debate over slavery continued in Congress, and abolitionists proposed its end in the District of Columbia, where Congress had jurisdiction. Pierce supported a resolution by Calhoun against this proposal, which Pierce considered a dangerous stepping stone to nationwide emancipation. Meanwhile, the Whigs were growing in congressional strength, which would leave Pierce's party with only a small majority by the end of the decade.

One topic of particular importance to Pierce was the military. He challenged a bill which would expand the ranks of the Army's staff officers in Washington without any apparent benefit to line officers at posts in the rest of the country. He took an interest in military pensions, seeing abundant fraud within the system, and was named chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Pensions in the Twenty-sixth Congress

The 26th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 183 ...

(1839–1841). In that capacity, he urged the modernization and expansion of the Army, with a focus on militias and mobility rather than on coastal fortifications, which he considered outdated.

Pierce campaigned vigorously throughout his home state for Van Buren's re-election in the 1840 presidential election. The incumbent carried New Hampshire but lost the election to the Whig candidate, military hero William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

. The Whigs took a majority of seats in the Twenty-seventh Congress. Harrison died after a month in office, and Vice President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

succeeded him. Pierce and the Democrats were quick to challenge the new administration, questioning the removal of federal officeholders, and opposing Whig plans for a national bank. In December 1841 Pierce decided to resign from Congress, something he had been planning for some time. New Hampshire Democrats insisted that their state's U. S. senators be limited to one six-year term, so he had little likelihood of re-election. Also, he was frustrated at being a member of the legislative minority and wished to devote his time to his family and law practice. His last actions in the Senate in February 1842 were to oppose a bill distributing federal funds to the states – believing that the money should go to the military instead – and to challenge the Whigs to reveal the results of their investigation of the New York Customs House, where the Whigs had probed for Democratic corruption for nearly a year but had issued no findings.

Party leader

Lawyer and politician

Asa Fowler

Asa Fowler (February 23, 1811 – April 26, 1885) was a New Hampshire politician, lawyer and jurist. He served as a justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court from August 1, 1855, until February 1, 1861, and in the New Hampshire House of Represen ...

during congressional recesses. Pierce returned to Concord in early 1842, and his reputation as a lawyer continued to flourish. Known for his gracious personality, eloquence, and excellent memory, Pierce attracted large audiences in court. He would often represent poor people for little or no compensation.

Pierce remained involved in the state Democratic Party, which was split by several issues. Governor Hill, who represented the commercial, urban wing of the party, advocated the use of government charters to support corporations, granting them privileges such as limited liability and eminent domain for building railroads. The radical " locofoco" wing of his party represented farmers and other rural voters, who sought an expansion of social programs and labor regulations and a restriction on corporate privilege. The state's political culture grew less tolerant of banks and corporations after the Panic of 1837, and Hill was voted out of office. Pierce was closer to the radicals philosophically, and reluctantly agreed to represent Hill's adversary in a legal dispute regarding ownership of a newspaper—Hill lost, and founded his own paper, of which Pierce was a frequent target.

In June 1842 Pierce was named chairman of the State Democratic Committee, and in the following year's state election he helped the radical wing take over the state legislature. The party remained divided on several issues, including railroad development and the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

, and Pierce took a leading role in helping the state legislature settle their differences. His priorities were "order, moderation, compromise, and party unity", which he tried to place ahead of his personal views on political issues. As he would as president, Pierce valued Democratic Party unity highly, and saw the opposition to slavery as a threat to that.

Democratic James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

's dark horse victory in the 1844 presidential election

The 1844 United States presidential election was the 15th quadrennial presidential election, held from Friday, November 1 to Wednesday, December 4, 1844. Democrat James K. Polk defeated Whig Henry Clay in a close contest turning on the controv ...

was welcome news to Pierce, who had befriended the former Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

while both served in Congress. Pierce had campaigned heavily for Polk during the election, and in turn Polk appointed him as United States Attorney for New Hampshire. Polk's most prominent cause was the annexation of Texas

The Texas annexation was the 1845 annexation of the Republic of Texas into the United States. Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico ...

, an issue which caused a dramatic split between Pierce and his former ally Hale, now a U.S. Representative. Hale was so impassioned against adding a new slave state that he wrote a public letter to his constituents outlining his opposition to the measure. Pierce responded by re-assembling the state Democratic convention to revoke Hale's nomination for another term in Congress. The political firestorm led to Pierce severing ties with his longtime friend, and with his law partner Fowler, who was a Hale supporter. Hale refused to withdraw, and as a majority vote was needed for election in New Hampshire, the party split led to deadlock and a vacant House seat. Eventually, the Whigs and Hale's Independent Democrat

In U.S. politics, an independent Democrat is an individual who loosely identifies with the ideals of the Democratic Party but chooses not to be a formal member of the party (chooses to be an independent) or is denied the Democratic nomination ...

s took control of the legislature, elected Whig Anthony Colby

Anthony Colby (November 13, 1792July 20, 1873) was an American businessman and politician from New London, New Hampshire. He owned and operated a grist mill and a stage line, and served as the 20th governor of New Hampshire from 1846 to 1847.

Bi ...

as governor and sent Hale to the Senate, much to Pierce's anger.

Mexican–American War

Active military service was a long-held dream for Pierce, who had admired his father's and brothers' service in his youth, particularly his older brother Benjamin's, as well as that of

Active military service was a long-held dream for Pierce, who had admired his father's and brothers' service in his youth, particularly his older brother Benjamin's, as well as that of John McNeil Jr.

John McNeil Jr. (March 25, 1784 – February 23, 1850) was an officer in the United States Army. He distinguished himself in leading the bayonet charge which secured victory in the Battle of Chippewa. For his conduct in this battle, and in tha ...

, husband of Pierce's older half-sister Elizabeth. As a legislator, he was a passionate advocate for volunteer militias. As a militia officer himself, he had experience mustering and drilling bodies of troops. When Congress declared war against Mexico in May 1846, Pierce immediately volunteered to join, although no New England regiment yet existed. His hope to fight in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

was one reason he refused an offer to become Polk's Attorney General. General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

's advance slowed in northern Mexico, and General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

proposed capturing the port of Vera Cruz and driving overland to Mexico City. Congress passed a bill authorizing the creation of ten regiments, and Pierce was appointed commander and colonel of the 9th Infantry Regiment in February 1847, with Truman B. Ransom as lieutenant colonel and second-in-command.

On March 3, 1847, Pierce was promoted to

On March 3, 1847, Pierce was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

, and took command of a brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

of reinforcements for General Scott's army, with Ransom succeeding to command of the regiment. Needing time to assemble his brigade, Pierce reached the already-seized port of Vera Cruz in late June, where he prepared a march of 2,500 men accompanying supplies for Scott. The three-week journey inland was perilous, and the men fought off several attacks before joining with Scott's army in early August, in time for the Battle of Contreras

The Battle of Contreras, also known as the Battle of Padierna, took place on 19–20 August 1847, in one of the final encounters of the Mexican–American War, as invading U.S. forces under Winfield Scott approached the Mexican capital. Americ ...

. The battle was disastrous for Pierce: his horse was suddenly startled during a charge, knocking him groin-first against his saddle. The horse then tripped into a crevice and fell, pinning Pierce underneath and debilitating his knee. The incident made it look like he had fainted, causing one soldier to call for someone else to take command, "General Pierce is a damned coward." Pierce returned for the following day's action, but re-injured his knee, forcing him to hobble after his men; by the time he caught up, the battle was mostly won.

As the Battle of Churubusco approached, Scott ordered Pierce to the rear to convalesce. He responded, "For God's sake, General, this is the last great battle, and I must lead my brigade." Scott yielded, and Pierce entered the fight tied to his saddle, but the pain in his leg became so great that he passed out on the field. The Americans won the battle and Pierce helped negotiate an armistice. He then returned to command and led his brigade throughout the rest of the campaign, eventually taking part in the capture of Mexico City in mid-September, although his brigade was held in reserve for much of the battle. For much of the Mexico City battle, he was in the sick tent, plagued with acute diarrhea. Pierce remained in command of his brigade during the three-month occupation of the city; while frustrated with the stalling of peace negotiations, he also tried to distance himself from the constant conflict between Scott and the other generals.

Pierce was finally allowed to return to Concord in late December 1847. He was given a hero's welcome in his home state, and submitted his resignation from the Army, which was approved on March 20, 1848. His military exploits elevated his popularity in New Hampshire, but his injuries and subsequent troubles in battle led to accusations of cowardice which would long shadow him. He had demonstrated competence as a general, especially in the initial march from Vera Cruz, but his short tenure and his injury left little for historians to judge his ability as a military commander.

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, who had the opportunity to observe Pierce firsthand during the war, countered the allegations of cowardice in his memoirs, written several years after Pierce's death: "Whatever General Pierce's qualifications may have been for the Presidency, he was a gentleman and a man of courage. I was not a supporter of him politically, but I knew him more intimately than I did any other of the volunteer generals."

Return to New Hampshire

Returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law practice; in one notable case he defended the religious liberty of the Shakers, the insular sect threatened with legal action over accusations of abuse. His role as a party leader, however, continued to take up most of his attention. He continued to wrangle with Senator Hale, who was anti-slavery and had opposed the war, stances that Pierce regarded as needless agitation.

The large Mexican Cession of land divided the United States politically, with many in the North insisting that slavery not be allowed there (and offering the

Returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law practice; in one notable case he defended the religious liberty of the Shakers, the insular sect threatened with legal action over accusations of abuse. His role as a party leader, however, continued to take up most of his attention. He continued to wrangle with Senator Hale, who was anti-slavery and had opposed the war, stances that Pierce regarded as needless agitation.

The large Mexican Cession of land divided the United States politically, with many in the North insisting that slavery not be allowed there (and offering the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

to ensure it), while others wanted slavery barred north of the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

line of 36°30′ N. Both proposals were anathema to many Southerners, and the controversy split the Democrats. At the 1848 Democratic National Convention

The 1848 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from Monday May 22 to Thursday May 25 in Baltimore, Maryland. It was held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for President and Vice president i ...

, the majority nominated former Michigan senator Lewis Cass for president, while a minority broke off to become the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

, backing former president Van Buren. The Whigs chose General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, a Louisianan, whose views on most political issues were unknown. Despite his past support for Van Buren, Pierce supported Cass, turning down the quiet offer of second place on the Free Soil ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

, and was so effective that Taylor, who was elected president, was held in New Hampshire to his lowest percentage in any state.

Senator Henry Clay, a Whig, hoped to put the slavery question to rest with a set of proposals that became known as the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

. These would give victories to North and South, and gained the support of his fellow Whig, Webster. With the bill stalled in the Senate, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

led a successful effort to split it into separate measures so that each legislator could vote against the parts his state opposed without endangering the overall package. The bills passed, and were signed by President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

(who had succeeded Taylor after the president's death earlier in 1850). Pierce strongly supported the compromise, giving a well-received speech in December 1850 pledging himself to "The Union! Eternal Union!" The same month, the Democratic candidate for governor, John Atwood, issued a letter opposing the Compromise, and Pierce helped to recall the state convention and remove Atwood from the ticket. The fiasco compromised the election for the Democrats, who lost several races; still, Pierce's party retained its control over the state, and was well positioned for the upcoming presidential election.

Election of 1852

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided by the slavery issue, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party with Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned. It was widely expected that the

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided by the slavery issue, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party with Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned. It was widely expected that the 1852 Democratic National Convention

The 1852 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 1 to June 5 in Baltimore, Maryland. It was held to nominate the Democratic Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1852 electi ...

would result in deadlock, with no major candidate able to win the necessary two-thirds majority. New Hampshire Democrats, including Pierce, supported his old teacher, Levi Woodbury, by then an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1 ...

, as a compromise candidate, but Woodbury's death in September 1851 opened up an opportunity for Pierce's allies to present him as a potential dark horse in the mold of Polk. New Hampshire Democrats felt that, as the state in which their party had most consistently gained Democratic majorities, they should supply the presidential candidate. Other possible standard-bearers included Douglas, Cass, William Marcy of New York, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Sam Houston of Texas, and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.

Despite home state support, Pierce faced obstacles to his nomination, since he had been out of office for a decade, and lacked the front-runners' national reputation. He publicly declared that such a nomination would be "utterly repugnant to my tastes and wishes", but given the desire of New Hampshire Democrats to see one of their own elected, he knew his future influence depended on his availability to run. Thus, he quietly allowed his supporters to lobby for him, with the understanding that his name would not be entered at the convention unless it was clear none of the front-runners could win. To broaden his potential base of southern support as the convention approached, he wrote letters reiterating his support for the Compromise of 1850, including the controversial Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also kno ...

.

The convention assembled on June 1 in Baltimore, and the deadlock occurred as expected. On the first ballot of the 288 delegates, held on June 3, Cass claimed 116, Buchanan 93, and the rest were scattered, without a single vote for Pierce. The next 34 ballots passed with no winner even close, and still no votes for Pierce. The Buchanan team then had their delegates vote for minor candidates, including Pierce, to demonstrate Buchanan's inevitability, and unite the convention behind him. This novel tactic backfired after several ballots as Virginia, New Hampshire, and Maine switched to Pierce; the remaining Buchanan forces began to break for Marcy, and Pierce was soon in third place. After the 48th ballot, North Carolina Congressman James C. Dobbin delivered an unexpected and passionate endorsement of Pierce, sparking a wave of support for the dark horse candidate. On the 49th ballot, Pierce received all but six of the votes, and thus gained the Democratic nomination for president. Delegates selected Alabama Senator William R. King, a Buchanan supporter, as Pierce's running mate, and adopted a platform that rejected further "agitation" over the slavery issue and supported the Compromise of 1850.

When word reached New Hampshire of the result, Pierce found it difficult to believe, and his wife fainted. Their son Benjamin wrote to his mother hoping that Franklin's candidacy would not be successful, as he knew she would not like to live in Washington.

The Whig candidate was General Scott, Pierce's commander in Mexico; his running mate was

The Whig candidate was General Scott, Pierce's commander in Mexico; his running mate was Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

William A. Graham. The Whigs could not unify their factions as the Democrats had, and the convention adopted a platform almost indistinguishable from that of the Democrats, including support of the Compromise of 1850. This incited the Free Soilers to field their own candidate, Senator Hale of New Hampshire, at the expense of the Whigs. The lack of political differences reduced the campaign to a bitter personality contest and helped to dampen voter turnout

In political science, voter turnout is the participation rate (often defined as those who cast a ballot) of a given election. This can be the percentage of registered voters, eligible voters, or all voting-age people. According to Stanford Univ ...

to its lowest level since 1836

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Queen Maria II of Portugal marries Prince Ferdinand Augustus Francis Anthony of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

* January 5 – Davy Crockett arrives in Texas.

* January 12

** , with Charles Darwin on board, re ...

; according to biographer Peter A. Wallner, it was "one of the least exciting campaigns in presidential history". Scott was harmed by the lack of enthusiasm of anti-slavery northern Whigs for him and the platform; ''New-York Tribune