Dactylic hexameter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dactylic hexameter (also known as heroic hexameter and the meter of epic) is a form of meter or rhythmic scheme frequently used in Ancient Greek and Latin poetry. The scheme of the hexameter is usually as follows (writing – for a long syllable, u for a short, and u u for a position that may be a long or two shorts):

:, – u u , – u u , – u u , – u u , – u u , – –

Here, ", " (pipe symbol) marks the beginning of a foot in the line.

Thus there are six feet, each of which is either a dactyl (– u u) or a spondee (– –). The first four feet can either be dactyls, spondees, or a mix. The fifth foot can also sometimes be a spondee, but this is rare, as it most often is a dactyl. The last foot is a spondee.

The hexameter is traditionally associated with classical

The hexameter came into Latin as an adaptation from Greek long after the practice of singing the epics had faded. Consequentially, the properties of the meter were learned as specific rules rather than as a natural result of musical expression. Also, because the Latin language generally has a higher proportion of long syllables than Greek, it is by nature more spondaic. Thus the Latin hexameter took on characteristics of its own.

The hexameter came into Latin as an adaptation from Greek long after the practice of singing the epics had faded. Consequentially, the properties of the meter were learned as specific rules rather than as a natural result of musical expression. Also, because the Latin language generally has a higher proportion of long syllables than Greek, it is by nature more spondaic. Thus the Latin hexameter took on characteristics of its own.

Radnóti's poems with English translations

see the Fifth, Seventh or Eighth Eclogue, the seventh being the most famous, while the eighth is translated into English in hexameters.

"Notes on the Bucolic Diaeresis".

''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' Vol. 36 (1905), pp. 111–124. * Butcher, W. G. D. (1914)

"The Caesvra in Virgil, and Its Bearing on the Authenticity of the Pseudo-Vergiliana"

''The Classical Quarterly'', Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 123–131. * Heikkinen, S. (2015). ''From Persius to Wilkinson: The Golden Line Revisited''. ''Arctos'' 49, pp. 57–77. * Raven, D. S. (1962). ''Greek Metre: An Introduction''. (Routledge) * Raven, D. S. (1965). ''Latin Metre: An Introduction''. (Routledge) * West, M. L. (1987). ''Introduction to Greek Metre''. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Introduction to dactylic hexameter

for Latin verse.

Reading dactylic hexameter

specifically Homer.

Recitation of Homer Iliad 23.62-107

(in Greek), by Stanley Lombardo.

Oral reading of Virgil's ''Aeneid''

by Robert Sonkowsky, University of Minnesota.

Greek hexameter analysis online tool

University of Vilnius.

by Dale Grote, UNC Charlotte.

Hexameter.co

practice scanning lines of dactylic hexameter from a variety of Latin authors.

Rodney Merrill reading his translation of Homer's Iliad

in English dactylic hexameter verse. {{Aeneid Types of verses Ancient Greek epic poetry Latin poetry

epic poetry

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

in both Greek and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and was consequently considered to be ''the'' grand style of Western classical poetry. Some well known examples of its use are Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

'' and ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

'', Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the '' Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and ...

's ''Argonautica'', Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of ...

'', Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his '' magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the ...

'', Lucan's '' Pharsalia'' (an epic on the Civil War), Valerius Flaccus's ''Argonautica'', and Statius's ''Thebaid''.

However, hexameters had a wide use outside of epic. Greek works in hexameters include Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

's '' Works and Days'' and '' Theogony'', Theocritus's ''Idylls'', and Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide varie ...

's hymns. In Latin famous works include Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

's philosophical , Virgil's ''Eclogues

The ''Eclogues'' (; ), also called the ''Bucolics'', is the first of the three major works of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by offer ...

'' and ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

'', book 10 of Columella's manual on agriculture, as well as Latin satirical poems by the poets Lucilius

The gens Lucilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. The most famous member of this gens was the poet Gaius Lucilius, who flourished during the latter part of the second century BC.''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology'', vo ...

, Horace, Persius

Aulus Persius Flaccus (; 4 December 3424 November 62 AD) was a Roman poet and satirist of Etruscan origin. In his works, poems and satires, he shows a Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he considered to be the stylistic abuses of hi ...

, and Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the '' Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

. The hexameter continued to be used in Christian times, for example in the of the 5th-century Irish poet Sedulius and Bernard of Cluny's 12th-century satire among many others.

Hexameters also form part of elegiac poetry in both languages, the elegiac couplet being a dactylic hexameter line paired with a dactylic pentameter line. This form of verse was used for love poetry by Propertius, Tibullus, and Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom ...

, for Ovid's letters from exile, and for many of the epigrams of Martial.

Structure

Syllables

Ancient Greek and Latin poetry is made up of long and short syllables arranged in various patterns. In Greek, a long syllable is () and a short syllable is (). In Latin the terms are and . The process of deciding which syllables are long and which are short is known as scansion. A syllable is long if it contains a long vowel or a diphthong: , . It is also long (with certain exceptions) if it has a short vowel followed by two consonants, even if these are in different words: , , . In this case a syllable like ''et'' is said to be long by position. There are some exceptions to the above rules, however. For example, ''tr'', ''cr'', ''pr'', ''gr'', and ''pl'' (and other combinations of a consonant with ''r'' or ''l'') can count as a single consonant, so that the word could be pronounced either with the first syllable short or with the first syllable long. Also the letter ''h'' is ignored in scansion, so that in the phrase the syllable ''et'' remains short. ''qu'' counts as a single consonant, so that in the word "water" the first syllable is short, not like the Italian . In certain words like , , , , and , ''i'' is a consonant, pronounced like the English ''y,'' so has three syllables and "he threw" has two. But in , the name of Aeneas's son, ''I'' is a vowel and forms a separate syllable. "Trojan" has three syllables, but "of Troy" has two. In some editions of Latin texts the consonant ''v'' is written as ''u'', in which case ''u'' is also often consonantal. This can sometimes cause ambiguity; e.g., in the word (= ) "he rolls" the second ''u'' is a consonant, but in (= ) "he wanted" the second ''u'' is a vowel.Feet

A hexameter line can be divided into six feet (Greek ἕξ ''hex'' = "six"). In strict dactylic hexameter, each foot would be adactyl

Dactyl may refer to:

* Dactyl (mythology), a legendary being

* Dactyl (poetry), a metrical unit of verse

* Dactyl Foundation, an arts organization

* Finger, a part of the hand

* Dactylus, part of a decapod crustacean

* "-dactyl", a suffix u ...

(a long and two short syllables, i.e. – u u), but classical meter allows for the substitution of a spondee

A spondee (Latin: ) is a metrical foot consisting of two long syllables, as determined by syllable weight in classical meters, or two stressed syllables in modern meters. The word comes from the Greek , , ' libation'.

Spondees in Ancient Gre ...

(two long syllables, i.e. – –) in place of a dactyl in most positions. Specifically, the first four feet can either be dactyls or spondees more or less freely. The fifth foot is usually a dactyl (around 95% of the lines in Homer).

The sixth foot can be filled by either a trochee (a long then short syllable) or a spondee. Thus the dactylic line most normally is scanned as follows:

:, – u u , – u u , – u u , – u u , – u u , – x ,

(Here "–" = a long syllable, "u" = a short syllable, "u u" = either one long or two shorts, and "x" = an '' anceps'' syllable, which can be long or short.)

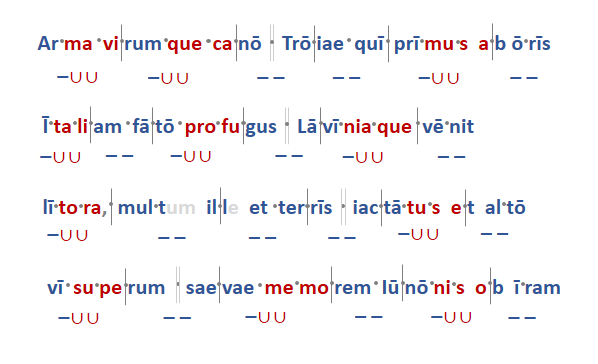

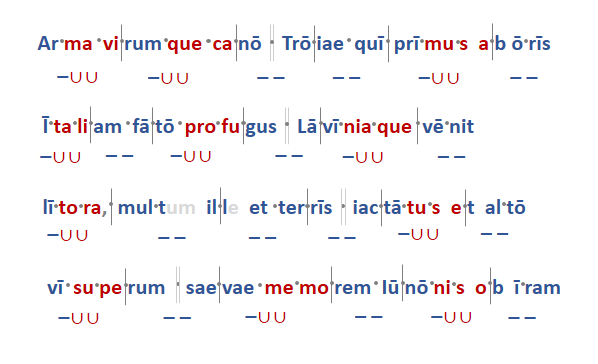

An example of this in Latin is the first line of Virgil's ''Aeneid'':

:

:"I sing of arms, and of the man who first from the shores of Troy ..."

The scansion is generally marked as follows, by placing long and short marks above the central vowel of each syllable:

– u u , – u u , – – , – – , – u u , – –

ar ma vi , rum que ca , nō Troj , jae quī , prī mu sa , bō rīs

''dactyl'' , ''dactyl'' , ''spondee'' , ''spondee'' , ''dactyl'' , ''spondee''

(Spaces mark syllable breaks)

In dactylic verse, short syllables always come in pairs, so words such as "soldiers" or "more easily" cannot be used in a hexameter.

Elision

In Latin, when a word ends in a vowel or -m and is followed by a word starting with a vowel, the last vowel is usually elided (i.e. removed or pronounced quickly enough not to add to the length of the syllable), for example, . Again, "h" is ignored and does not prevent elision: . In Greek, short vowels elide freely, and the elision is shown by an apostrophe, for example in line 2 of the ''Iliad'': () "which caused countless sufferings for the Achaeans". However, a long vowel is not elided: (). This feature is sometimes imitated in Latin for special effect, for example, "with womanly wailing" (''Aen''. 9.477). When a vowel is elided, it does not count in the scansion; so for the purposes of scansion, has four syllables.Caesura

Almost every hexameter has a word break, known as acaesura

300px, An example of a caesura in modern western music notation

A caesura (, . caesuras or caesurae; Latin for " cutting"), also written cæsura and cesura, is a metrical pause or break in a verse where one phrase ends and another phrase begin ...

, in the middle of the 3rd foot, sometimes (but not always) coinciding with a break in sense. In most cases (85% of lines in Virgil) this comes after the first syllable of the 3rd foot, as in in the above example. This is known as a strong or masculine caesura.

When the 3rd foot is a dactyl, the caesura can come after the second syllable of the 3rd foot; this is known as a weak or feminine caesura. It is more common in Greek than in Latin.Raven (1965), p. 96. An example is the first line of Homer's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

'':

:

:

:"Tell me, Muse, of the man of many wiles, who very much ..."

In Latin (but not in Greek, as the above example shows), whenever a feminine caesura is used in the 3rd foot, it is usually accompanied by masculine caesuras in the 2nd and 4th feet also:

:

:"You are bidding me, o queen, to renew an unspeakable sorrow"

Sometimes a line is found without a 3rd foot caesura, such as the following. In this case the 2nd and 4th foot caesuras are obligatory:

:

:"then from his high couch Father Aeneas began as follows"

In Greek

The hexameter was first used by early Greek poets of the oral tradition, and the most complete extant examples of their works are the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

'', which influenced the authors of all later classical epics that survive today. Early epic poetry was also accompanied by music, and pitch changes associated with the accented Greek must have highlighted the melody, though the exact mechanism is still a topic of discussion.

The first line of Homer’s ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

'' provides an example:

:

:

:"Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilles"

Dividing the line into metrical units or feet it can be scanned as follows:

:

: (-''deō'' is one syllable)

:dactyl, dactyl, spondee, dactyl, dactyl, spondee

: , – u u , – u u , –, – , – u u , – u u , – – ,

This line also includes a masculine caesura after , a break that separates the line into two parts. Homer employs a feminine caesura more commonly than later writers. An example occurs in ''Iliad'' 1.5:

:

:"... and every bird; and the plan of Zeus was fulfilled"

:

:

:, – – , – u u , – u, u , – u u , – u u , – – ,

Homer’s hexameters contain a higher proportion of dactyls than later hexameter poetry. They are also characterised by a laxer following of verse principles than later epicists almost invariably adhered to. For example, Homer allows spondaic fifth feet (albeit not often), whereas many later authors do not.

Homer also altered the forms of words to allow them to fit the hexameter, typically by using a dialectal

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that ...

form: ''ptolis'' is an epic form used instead of the Attic ''polis'' as necessary for the meter. Proper names sometimes take forms to fit the meter, for example ''Pouludamas'' instead of the metrically unviable ''Poludamas''.

Some lines require a knowledge of the digamma for their scansion, e.g. ''Iliad'' 1.108:

:

:

:"you have not yet spoken a good word nor brought one to pass"

:

:

: , – – , – u u , – – , – u u , – u u , – – ,

Here the word (''epos'') was originally (''wepos'') in Ionian; the digamma

Digamma or wau (uppercase: Ϝ, lowercase: ϝ, numeral: ϛ) is an archaic letter of the Greek alphabet. It originally stood for the sound but it has remained in use principally as a Greek numeral for 6. Whereas it was originally called ''wa ...

, later lost, lengthened the last syllable of the preceding (''eipas'') and removed the apparent defect in the meter. A digamma also saved the hiatus in the third foot. This example demonstrates the oral tradition of the Homeric epics that flourished before they were written down sometime in the 7th century BC.

Most of the later rules of hexameter composition have their origins in the methods and practices of Homer.

In Latin

The hexameter came into Latin as an adaptation from Greek long after the practice of singing the epics had faded. Consequentially, the properties of the meter were learned as specific rules rather than as a natural result of musical expression. Also, because the Latin language generally has a higher proportion of long syllables than Greek, it is by nature more spondaic. Thus the Latin hexameter took on characteristics of its own.

The hexameter came into Latin as an adaptation from Greek long after the practice of singing the epics had faded. Consequentially, the properties of the meter were learned as specific rules rather than as a natural result of musical expression. Also, because the Latin language generally has a higher proportion of long syllables than Greek, it is by nature more spondaic. Thus the Latin hexameter took on characteristics of its own.

Ennius

The earliest example of hexameter in Latin poetry is the ''Annales'' ofEnnius

Quintus Ennius (; c. 239 – c. 169 BC) was a writer and poet who lived during the Roman Republic. He is often considered the father of Roman poetry. He was born in the small town of Rudiae, located near modern Lecce, Apulia, (Ancient Calabri ...

(now mostly lost except for about 600 lines), which established it as the standard for later Latin epics; it was written towards the end of Ennius's life about 172 BC. Ennius experimented with different kinds of lines, for example, lines with five dactyls:

:

:"Then the trumpet with terrifying sound went 'taratantara!'"

or lines consisting entirely of spondees:

:

:"To him replied the king of Alba Longa"

lines without a caesura:

:

:"With scattered long spears the plain gleams and bristles"

lines ending in a one-syllable word or in words of more than three syllables:

:

:"A single man, by delaying, restored the situation for us."

:

:

:"I do not demand gold for myself nor should you give me a price:

:not buying and selling war, but waging it"

or even lines starting with two short syllables:Raven (1965), p. 92.

:

: , u u – , – – , –, u u , – – , – u u , – –

:"the blacktail, the rainbow wrasse, the bird wrasse, and the maigre" (kinds of fish)

However, most of these features were abandoned by later writers or used only occasionally for special effect.

Later writers

Later Republican writers, such asLucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

, Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His ...

, and even Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, wrote hexameter compositions, and it was at this time that the principles of Latin hexameter were firmly established and followed by later writers such as Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, Horace, Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom ...

, Lucan, and Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the '' Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

. Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's opening line for the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of ...

'' is a classic example:

:

:"I sing of arms and of the man who first from the shores of Troy ..."

In Latin, lines were arranged so that the metrically long syllables—those occurring at the beginning of a foot—often avoided the natural stress of a word. In the earlier feet of a line, meter and stress were expected to clash, while in the last two feet they were expected to coincide, as in above. The coincidence of word accent and meter in the last two feet could be achieved by restricting the last word to one of two or three syllables.

Most lines (about 85% in Virgil) have a caesura or word division after the first syllable of the 3rd foot, as above . This is known as a strong or masculine caesura. Because of the penultimate accent in Latin, this ensures that the word accent and meter will not coincide in the 3rd foot. But in those lines with a feminine or weak caesura, such as the following, there is inevitably a coincidence of meter and accent in the 3rd foot:Raven (1965), p. 98.

:

:"there follows shouting of men and rattling of ropes"

To offset this, whenever there was a feminine caesura in the 3rd foot, there was usually also a masculine caesura in the 2nd and 4th feet, to ensure that in those feet at least, the word accent and meter did not coincide.

Metrical effects

By the age ofAugustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, poets like Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

closely followed the rules of the meter and approached it in a highly rhetorical way, looking for effects that can be exploited in skilled recitation. For example, the following line from the ''Aeneid'' (8.596) describes the movement and sound of galloping horses:

:

:"with four-footed sound the hoof shakes the crumbling plain"

This line is made up of five dactyls and a closing spondee, an unusual rhythmic arrangement that imitates the described action. A different effect is found in 8.452, where Virgil describes how the blacksmith sons of Vulcan forged Aeneas' shield. The five spondees and the word accents cutting across the verse rhythm give an impression of huge effort:

:

:"They with much force raise their arms one after another"

A slightly different effect is found in the following line (3.658), describing the terrifying one-eyed giant Polyphemus, blinded by Ulysses. Here again there are five spondees but there are also three elisions, which cause the word accent of all the words but to coincide with the beginning of each foot:

:

:"A horrendous huge shapeless monster, whose eye (lit. light) had been removed"

A succession of long syllables in some lines indicates slow movement, as in the following example where Aeneas and his companion the Sibyl (a priestess of Apollo) were entering the darkness of the world of the dead:

:

:"they were going in the darkness beneath the lonely night through the shadow"

The following example (''Aeneid'' 2.9) describes how Aeneas is reluctant to begin his narrative, since it is already past midnight. The feminine caesura after without a following 4th-foot caesura ensures that all the last four feet have word accent at the beginning, which is unusual. The monotonous effect is reinforced by the assonance of ''dent ... dent'' and the alliteration of S ... S:

:

:

:"And already the moist night is falling from the sky

:and the setting constellations are inviting sleep"

Dactyls are associated with sleep again in the following unusual line, which describes the activity of a priestess who is feeding a magic serpent (''Aen.'' 4.486). In this line, there are five dactyls, and every one is accented on the first syllable:

:

:"sprinkling moist honey and sleep-inducing poppy"

A different technique, at 1.105, is used when describing a ship at sea during a storm. Here Virgil places a single-syllable word at the end of the line. This produces a jarring rhythm that echoes the crash of a large wave against the side of the ship:

:

:

:"(The boat) gives its side to the waves; there immediately follows in a heap a steep mountain of water."

The Roman poet Horace uses a similar trick to highlight the comedic irony in this famous line from his '' Ars Poetica'' (line 139):

:

:"The mountains will be in labor, but all that will be born is a ridiculous ... mouse"

Usually in Latin the 5th foot of a hexameter is a dactyl. However, in his poem 63, Catullus several times uses a 5th foot spondee, which gives a Greek flavour to his verse, as in this line describing the forested Vale of Tempe

The Vale of Tempe ( el, Κοιλάδα των Τεμπών) is a gorge in the Tempi municipality of northern Thessaly, Greece, located between Olympus to the north and Ossa to the south, and between the regions of Thessaly and Macedonia.

The ...

in northern Greece:

:

:"Tempe, which woods surround, hanging over it"

Virgil also occasionally imitates Greek practice, for example, in the first line of his 3rd Eclogue:

:

:"Tell me, Damoetas, whose cattle are these? Are they Meliboeus's?"

Here there is a break in sense after a 4th-foot dactyl, a feature known as a bucolic diaeresis, because it is frequently used in Greek pastoral poetry. In fact it is common in Homer too (as in the first line of the ''Odyssey'' quoted above), but rare in Latin epic.

Stylistic features of epic

Certain stylistic features are characteristic of epic hexameter poetry, especially as written by Virgil.Enjambment

Hexameters are frequently enjambed—the meaning runs over from one line to the next, without terminal punctuation—which helps to create the long, flowing narrative of epic. Sentences can also end in different places in the line, for example, after the first foot. In this, classical epic differs from medieval Latin, where the lines are often composed individually, with a break in sense at the end of each one.Poetic vocabulary

Often in poetry ordinary words are replaced by poetic ones, for example or for water, for sea, for ship, for river, and so on.Hyperbaton

It is common in poetry for adjectives to be widely separated from their nouns, and quite often one adjective–noun pair is interleaved with another. This feature is known ashyperbaton

Hyperbaton , in its original meaning, is a figure of speech in which a phrase is made discontinuous by the insertion of other words.Andrew M. Devine, Laurence D. Stephens, ''Latin Word Order: Structured Meaning and Information'' (Oxford: Oxford Uni ...

"stepping over". An example is the opening line of Lucan's epic on the Civil War:

:

:"Wars through the Emathian – more than civil – plains"

Another example is the opening of Ovid's mythological poem Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his '' magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the ...

where the word "new" is in a different line from "bodies" which it describes:

: (Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.1)

:"My spirit leads me to tell of forms transformed into new bodies."

One particular arrangement of words that seems to have been particularly admired is the golden line, a line which contains two adjectives, a verb, and two nouns, with the first adjective corresponding to the first noun such as:

:

:"and the barbarian pipe was strident with horrible music"

Catullus was the first to use this kind of line, as in the above example. Later authors used it rarely (1% of lines in Ovid), but in silver Latin it became increasingly popular.

Alliteration and assonance

Virgil in particular used alliteration and assonance frequently, although it is much less common in Ovid. Often more than one consonant was alliterated and not necessarily at the beginning of words, for example: : : :"But the queen, now long wounded by grave anxiety, :feeds the wound in her veins and is tormented by an unseen fire" Also in Virgil: : "places silent with night everywhere" : "those ones with oars sweep the dark shallows" Sometimes the same vowel is repeated: : :"on me, me, I who did it am here, turn your swords on me!" : :"he does not let go of the reins, but he is not strong enough to hold them back, and he does not know the names of the horses"Rhetorical techniques

Rhetorical devices such as anaphora, antithesis, and rhetorical questions are frequently used in epic poetry. Tricolon is also common: : : :"All this crowd that you see, are the poor and unburied; :that ferryman is Charon; these, that the wave is carrying, are the buried."Genre of subject matter

The poems of Homer, Virgil, and Ovid often vary their narrative with speeches. Well known examples are the speech of Queen Dido cursing Aeneas in book 4 of the ''Aeneid'', the lament of the nymph Juturna when she is unable to save her brother Turnus in book 12 of the ''Aeneid'', and the quarrel between Ajax and Ulysses over the arms of Achilles in book 13 of Ovid's ''Metamorphoses''. Some speeches are themselves narratives, as when Aeneas tells Queen Dido about the fall of Troy and his voyage to Africa in books 2 and 3 of the ''Aeneid''. Other styles of writing include vivid descriptions, such as Virgil's description of the god Charon in ''Aeneid'' 6, or Ovid's description of Daedalus's labyrinth in book 8 of the ''Metamorphoses''; similes, such as Virgil's comparison of the souls of the dead to autumn leaves or clouds of migrating birds in ''Aeneid'' 6; and lists of names, such as when Ovid names 36 of the dogs who tore their master Actaeon to pieces in book 3 of the ''Metamorphoses''.Conversational style

Raven divides the various styles of the hexameter in classical Latin into three types: the early stage (Ennius), the fully developed type (Cicero, Catullus, Virgil, and Ovid, with Lucretius about midway between Ennius and Cicero), and the conversational type, especially Horace, but also to an extent Persius and Juvenal. One feature which marks these off is their often irregular line endings (for example, words of one syllable) and also the very conversational, un-epic style. Horace in fact called his satires ("conversations"). The word order and vocabulary is much as might be expected in prose. An example is the opening of the 9th satire of book 1: : : : : :"I was walking by chance along the Sacred Way, as is my custom, :meditating on some trifle or other, completely absorbed in it, :when suddenly up ran a certain person known to me by name only. :He grabbed my hand and said 'How are you, sweetest of things?'"Silver Age and later use

The verse innovations of the Augustan writers were carefully imitated by their successors in the Silver Age ofLatin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings written in the Latin language. The beginning of formal Latin literature dates to 240 BC, when the first stage play in Latin was performed in Rome. Latin literature ...

. The verse form itself then was little changed as the quality of a poet's hexameter was judged against the standard set by Virgil and the other Augustan poets, a respect for literary precedent encompassed by the Latin word '. Deviations were generally regarded as idiosyncrasies or hallmarks of personal style and were not imitated by later poets. Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the '' Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

, for example, was fond of occasionally creating verses that placed a sense break between the fourth and fifth foot (instead of in the usual caesura positions), but this technique—known as the bucolic diaeresis—did not catch on with other poets.

In the late empire, writers experimented again by adding unusual restrictions to the standard hexameter. The rhopalic verse of Ausonius is a good example; besides following the standard hexameter pattern, each word in the line is one syllable longer than the previous, e.g.:

:

:

:

:"O God, Hope of Eternal Life, Conciliator,

:if, with chaste entreaties, hoping for pardon, we keep vigil,

:look kindly on us and grant these prayers."

Also notable is the tendency among late grammarians to thoroughly dissect the hexameters of Virgil and earlier poets. A treatise on poetry by Diomedes Grammaticus is a good example, as this work categorizes dactylic hexameter verses in ways that were later interpreted under the golden line rubric. Independently, these two trends show the form becoming highly artificial—more like a puzzle to solve than a medium for personal poetic expression.

By the Middle Ages, some writers adopted more relaxed versions of the meter. Bernard of Cluny, in the 12th century, for example, employs it in his ''De Contemptu Mundi'', but ignores classical conventions in favor of accentual effects and predictable rhyme both within and between verses, e.g.:

:

:

:

:

:"These are the last days, the worst of times: let us keep watch.

:Behold the menacing arrival of the supreme Judge.

:He is coming, he is coming to end evil, to crown just actions,

:Reward what is right, free us from anxieties, and give the heavens."

Not all medieval writers are so at odds with the Virgilian standard, and with the rediscovery of classical literature, later Medieval and Renaissance writers are far more orthodox, but by then the form had become an academic exercise. Petrarch, for example, devoted much time to his ''Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

'', a dactylic hexameter epic on Scipio Africanus, completed in 1341, but this work was unappreciated in his time and remains little read today. It begins as follows:

:

:

:

:"To me also, o Muse, tell of the man,

:conspicuous for his merits and fearsome in war,

:to whom noble Africa, broken beneath Italian arms,

:first gave its eternal name."

In contrast, Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ' ...

decided to write his epic, the ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature a ...

'' in Italian—a choice that defied the traditional epic choice of Latin dactylic hexameters—and produced a masterpiece beloved both then and now.

With the New Latin period, the language itself came to be regarded as a medium only for serious and learned expression, a view that left little room for Latin poetry. The emergence of Recent Latin

Contemporary Latin is the form of the Literary Latin used since the end of the 19th century. Various kinds of contemporary Latin can be distinguished, including the use of New Latin words in taxonomy and in science generally, and the fuller ...

in the 20th century restored classical orthodoxy among Latinists and sparked a general (if still academic) interest in the beauty of Latin poetry. Today, the modern Latin poets who use the dactylic hexameter are generally as faithful to Virgil as Rome's Silver Age poets.

In modern languages

In English

Many poets have attempted to write dactylic hexameters in English, though few works composed in the meter have stood the test of time. Most such works are accentual rather than quantitative. Perhaps the most famous isLongfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and ''Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely transl ...

's " Evangeline", whose first lines are as follows:

:"This is the / forest pri/meval. The / murmuring / pines and the / hemlocks

:Bearded with / moss, and in / garments / green, indis/tinct in the / twilight,

:Stand like / Druids of / eld, with / voices / sad and pro/phetic..."

Contemporary poet Annie Finch wrote her epic libretto ''Among the Goddesses'' in dactylic tetrameter, which she claims is the most accurate English accentual equivalent of dactylic hexameter. Poets who have written quantitative hexameters in English include Robert Bridges

Robert Seymour Bridges (23 October 1844 – 21 April 1930) was an English poet who was Poet Laureate from 1913 to 1930. A doctor by training, he achieved literary fame only late in life. His poems reflect a deep Christian faith, and he is ...

and Rodney Merrill, whose translation of part of the Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

begins as follows (see External links below):

:"Sing now, / goddess, the / wrath of A/chilles the / scion of / Peleus,

:Ruinous / rage, which / brought the A/chaeans un/counted af/flictions;

:Many the / powerful / souls it / sent to the / dwelling of / Hades..."

Although the rules seem simple, it is hard to use classical hexameter in English, because English is a stress-timed

Isochrony is the postulated rhythmic division of time into equal portions by a language. Rhythm is an aspect of prosody, others being intonation, stress, and tempo of speech.

Three alternative ways in which a language can divide time are postul ...

language that condenses vowels and consonants between stressed syllables, while hexameter relies on the regular timing of the phonetic sounds. Languages having the latter properties (i.e., languages that are not stress timed) include Ancient Greek, Latin, Lithuanian and Hungarian.

In German

Dactylic hexameter has proved more successful in German than in most modern languages. Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock's epic '' Der Messias'' popularized accentual dactylic hexameter inGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

. Subsequent German poets to employ the form include Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

(notably in his '' Reineke Fuchs'') and Schiller.

The opening lines of Goethe's ("Reynard the Fox"), written in 1793–1794 are these:

:

:

:

:

:

:"Pentecost, the lovely festival, had come; field and forest

:grew green and bloomed; on hills and ridges, in bushes and hedges

:The newly encouraged birds practised a merry song;

:Every meadow sprouted with flowers in fragrant grounds,

:The sky shone festively cheerfully and the earth was colourful."

In French

Jean-Antoine de Baïf

Jean Antoine de Baïf (; 19 February 1532 – 19 September 1589) was a French poet and member of the '' Pléiade''.

Life

Jean Antoine de Baïf was born in Venice, the natural son of the scholar Lazare de Baïf, who was at that time French a ...

(1532–1589) wrote poems regulated by quantity

Quantity or amount is a property that can exist as a multitude or magnitude, which illustrate discontinuity and continuity. Quantities can be compared in terms of "more", "less", or "equal", or by assigning a numerical value multiple of a u ...

on the Greco–Roman model, a system which came to be known as '' vers mesurés'', or ''vers mesurés à l'antique'', which the French language of the Renaissance permitted. To do this, he invented a special phonetic alphabet. In works like his ''Étrénes de poézie Franzoęze an vęrs mezurés'' (1574) or ''Chansonnettes'' he used the dactylic hexameter, and other meters, in a quantitative way.

An example of one of his elegiac couplets is as follows. The final -e of , , and is sounded, and the word is pronounced /i/:

:

:

:, – u u , – – , – u u , – – , – u u , – –

:, – u u , – u u , – , , – u u , – u u , –

:"Let the handsome Narcissus come, who never loved another except himself,

:and let him look at your eyes, and let him try not to love you."

A modern attempt at reproducing the dactylic hexameter in French is this one, by André Markowicz (1985), translating Catullus's poem 63. Again the final -e and -es of , , and are sounded:

:

:

:, – – , – u u , – u u , – u u , – u u , – – ,

:, – u u , – – , – u u , – u u , – u u , – – ,

:"Is it for this that you have snatched me from the altars of my ancestors,

:to abandon me, traitorous Theseus, on these deserted shores?"

In Hungarian

Hungarian is extremely suitable to hexameter (and other forms of poetry based on quantitative meter). It has been applied to Hungarian since 1541, introduced by the grammarianJános Sylvester

János Sylvester sometimes known as János Erdősi (1504–1552) was a 16th-century Hungarian figure of the Reformation, and also a poet and grammarian, who was the first to translate the New Testament into Hungarian in 1541.

Life

He was bo ...

.

A hexameter can even occur spontaneously. For example, a student may extricate himself from failing to remember a poem by saying the following, which is a hexameter in Hungarian:

:Itt ela/kadtam, / sajnos / nem jut e/szembe a / többi.

:"I'm stuck here, unfortunately the rest won't come into my mind."

Sándor Weöres

Sándor Weöres (; 22 June 1913 – 22 January 1989) was a Hungarian poet and author.

Born in Szombathely, Weöres was brought up in the nearby village of Csönge. His first poems were published when he was fourteen, in the influential journ ...

included an ordinary nameplate text in one of his poems (this time, a pentameter):

:Tóth Gyula / bádogos / és // vízveze/ték-szere/lő.

:"Gyula Tóth tinsmith and plumber"

A label on a bar of chocolate went as follows, another hexameter, noticed by the poet Dániel Varró:

:Tejcsoko/ládé / sárgaba/rack- és / kekszdara/bokkal

:"Milk chocolate with apricot and biscuit bits"

Due to this feature, the hexameter has been widely used both in translated (Greek and Roman) and in original Hungarian poetry up to the twentieth century (e.g. by Miklós Radnóti).see the Fifth, Seventh or Eighth Eclogue, the seventh being the most famous, while the eighth is translated into English in hexameters.

In Lithuanian

'' The Seasons'' (''Metai'') byKristijonas Donelaitis

Kristijonas Donelaitis ( la, Christian Donalitius; 1 January 1714 – 18 February 1780) was a Prussian Lithuanian poet and Lutheran pastor. He lived and worked in Lithuania Minor, a territory in the Kingdom of Prussia, that had a sizable Lithuan ...

is a famous Lithuanian poem in quantitative dactylic hexameters. Because of the nature of Lithuanian, more than half of the lines of the poem are entirely spondaic save for the mandatory dactyl in the fifth foot.

See also

*Latin rhythmic hexameter The Latin rhythmic hexameter or accentual hexameter is a kind of Latin dactylic hexameter which arose in the Middle Ages alongside the metrical kind. The rhythmic hexameter did not scan correctly according to the rules of classical prosody; instead ...

* Prosody (Greek)

* Prosody (Latin)

* Meters of Roman comedy

* Trochaic septenarius In ancient Greek and Latin literature, the trochaic septenarius or trochaic tetrameter catalectic is one of two major forms of poetic metre based on the trochee as its dominant rhythmic unit, the other being much rarer trochaic octonarius. It is us ...

* Brevis in longo

* Anceps

* Biceps

The biceps or biceps brachii ( la, musculus biceps brachii, "two-headed muscle of the arm") is a large muscle that lies on the front of the upper arm between the shoulder and the elbow. Both heads of the muscle arise on the scapula and join t ...

* Resolution (meter)

Resolution is the metrical phenomenon in poetry of replacing a normally long syllable in the meter with two short syllables. It is often found in iambic and trochaic meters, and also in anapestic, dochmiac and sometimes in cretic, bacchiac, and i ...

Notes

References

* Bassett, S. E. (1905)"Notes on the Bucolic Diaeresis".

''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'' Vol. 36 (1905), pp. 111–124. * Butcher, W. G. D. (1914)

"The Caesvra in Virgil, and Its Bearing on the Authenticity of the Pseudo-Vergiliana"

''The Classical Quarterly'', Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 123–131. * Heikkinen, S. (2015). ''From Persius to Wilkinson: The Golden Line Revisited''. ''Arctos'' 49, pp. 57–77. * Raven, D. S. (1962). ''Greek Metre: An Introduction''. (Routledge) * Raven, D. S. (1965). ''Latin Metre: An Introduction''. (Routledge) * West, M. L. (1987). ''Introduction to Greek Metre''. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

Introduction to dactylic hexameter

for Latin verse.

Reading dactylic hexameter

specifically Homer.

Recitation of Homer Iliad 23.62-107

(in Greek), by Stanley Lombardo.

Oral reading of Virgil's ''Aeneid''

by Robert Sonkowsky, University of Minnesota.

Greek hexameter analysis online tool

University of Vilnius.

by Dale Grote, UNC Charlotte.

Hexameter.co

practice scanning lines of dactylic hexameter from a variety of Latin authors.

Rodney Merrill reading his translation of Homer's Iliad

in English dactylic hexameter verse. {{Aeneid Types of verses Ancient Greek epic poetry Latin poetry