Culture of Gwynedd during the High Middle Ages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Culture and Society in Gwynedd during the

/ref> Population increase was common throughout Europe in the 13th century, but in Wales it was more pronounced. By Llywelyn II's reign as much as 10 per cent of the population were town-dwellers. Additionally, "unfree slaves... had long disappeared" from within ''Pura Wallia'' due in large part form the social upheavals of the 11th century," argued Davies. The increase in free men allowed the prince to call on and field a far more substantial and professional army.

The increase in population in Gwynedd, and in the Principality of Wales as a whole, allowed a greater diversification of the economy. The Meirionnydd tax rolls evidence the thirty-seven various professions present in Meirionnydd immediately before the Edwardian Conquest of 1282.

Of these professions, there were eight

Population increase was common throughout Europe in the 13th century, but in Wales it was more pronounced. By Llywelyn II's reign as much as 10 per cent of the population were town-dwellers. Additionally, "unfree slaves... had long disappeared" from within ''Pura Wallia'' due in large part form the social upheavals of the 11th century," argued Davies. The increase in free men allowed the prince to call on and field a far more substantial and professional army.

The increase in population in Gwynedd, and in the Principality of Wales as a whole, allowed a greater diversification of the economy. The Meirionnydd tax rolls evidence the thirty-seven various professions present in Meirionnydd immediately before the Edwardian Conquest of 1282.

Of these professions, there were eight

The more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffudd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffudd I as reforming the orders of

The more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffudd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffudd I as reforming the orders of

By the 11th century, the Welsh Church consisted of three dioceses which were tied closely together by a strong sense of community and a shared sentiment in religious practice, but were independent of each other and whose boundaries were somewhat indeterminate. Central to this organisational approach was the rural nature of Welsh settlements which favoured localised and autonomous

By the 11th century, the Welsh Church consisted of three dioceses which were tied closely together by a strong sense of community and a shared sentiment in religious practice, but were independent of each other and whose boundaries were somewhat indeterminate. Central to this organisational approach was the rural nature of Welsh settlements which favoured localised and autonomous

Aberffraw's traditional sphere of influence in north Wales included the

Aberffraw's traditional sphere of influence in north Wales included the

''The emergence of the principality of Wales''

extracted 26 March 2008 * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Culture Of Gwynedd During The High Middle Ages Kingdom of Gwynedd Gwynedd High Middle Ages Culture High Middle Ages Culture Gwynedd, Culture

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

refers to a period in the History of Wales

The history of what is now Wales () begins with evidence of a Neanderthal presence from at least 230,000 years ago, while ''Homo sapiens'' arrived by about 31,000 BC. However, continuous habitation by modern humans dates from the period after ...

spanning the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries (AD 1000–1300). The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

and followed by the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

. Gwynedd is located in the north

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

.

Distinctive achievements in Gwynedd during this period include further development of Medieval Welsh literature

Medieval Welsh literature is the literature written in the Welsh language during the Middle Ages. This includes material starting from the 5th century AD, when Welsh was in the process of becoming distinct from Common Brittonic, and continuing to ...

, for instance in the poetry of those of the '' Beirdd y Tywysogion'' ( Welsh for ''Poets of the Princes'') associated with the court of Gwynedd, the reformation of bardic schools, and the continued development of ''Cyfraith Hywel

''Cyfraith Hywel'' (; ''Laws of Hywel''), also known as Welsh law ( la, Leges Walliæ), was the system of law practised in medieval Wales before its final conquest by England. Subsequently, the Welsh law's criminal codes were superseded by ...

'' (''The Law of Hywel'', or Welsh law); all three of which further contributed to the development of a Welsh national identity

Welsh national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity, as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture, languages and traditions, of the Welsh people.

History

Celtic era

The Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons wer ...

in the face of Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

encroachment of Wales and the threat of conquest by the Crown of England.

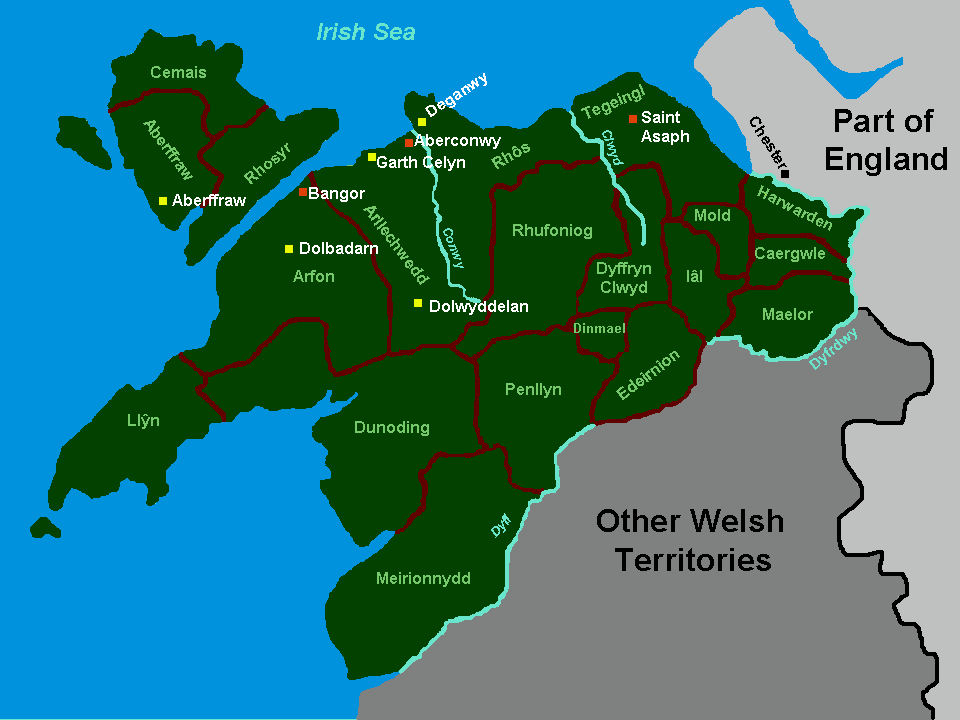

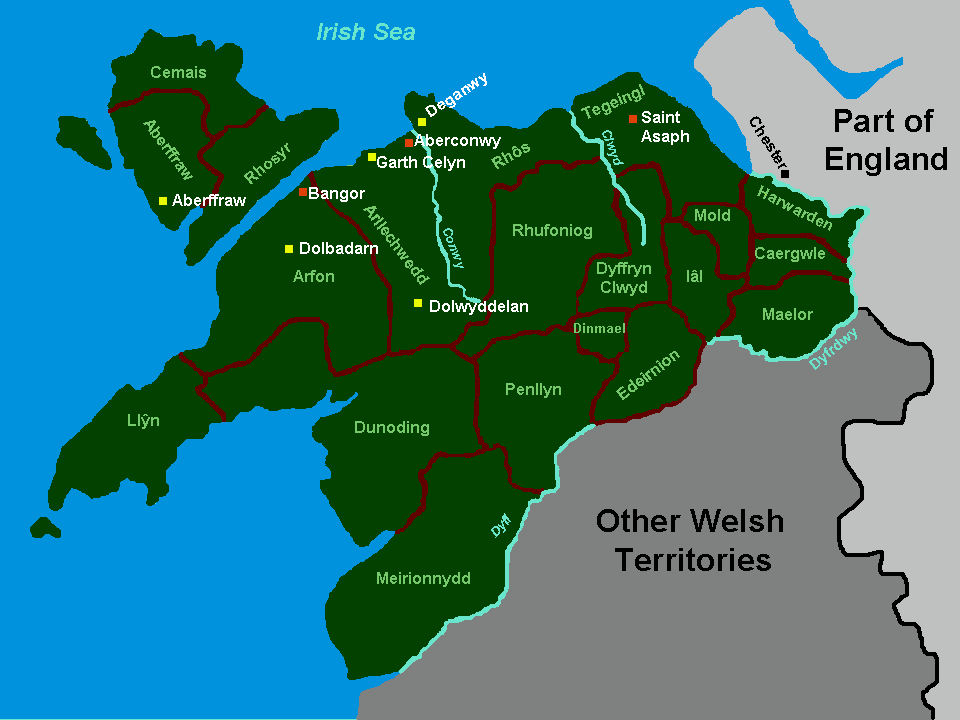

Gwynedd's traditional territory included Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

(''Ynys Môn'') and all of north Wales

North Wales ( cy, Gogledd Cymru) is a region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders Mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdonia N ...

between the River Dyfi

The River Dyfi ( cy, Afon Dyfi; ), also known as the River Dovey (; ), is an approximately long river in Wales.

Its large estuary forms the boundary between the counties of Gwynedd and Ceredigion, and its lower reaches have historically been c ...

in the south and River Dee ('' Welsh Dyfrdwy'') in the northeast.Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''foundations of'' pgs 50–51, 54–55 The Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

lies to the north and west, and lands formerly part of the Powys

Powys (; ) is a county and preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh successor state, petty kingdom and principality that emerged during the Middle Ages following the end of Roman rule in Britain.

Geog ...

border the south-east. Gwynedd's strength was due in part to the region's mountainous geography which made it difficult for foreign invaders to campaign in the country and impose their will effectively.Lloyd, J.E., ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'', Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. 2004, ''Recovers Gwynedd'', ''Norman invasion'', ''Battle of Anglesey Sound'', pgs 21–22, 36, 39, 40, ''later years'' 76–77

Gwynedd emerged from the Early Middle Ages having suffered from increasing Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raids and various occupations by rival Welsh princes, causing political and social upheaval. With the historic Aberffraw family displaced, by the mid 11th century Gwynedd was united with the rest of Wales by the conquest of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn ( 5 August 1063) was King of Wales from 1055 to 1063. He had previously been King of Gwynedd and Powys in 1039. He was the son of King Llywelyn ap Seisyll and Angharad daughter of Maredudd ab Owain, and the great-gre ...

, followed by the Norman invasions between 1067 and 1100.

After the restoration of the Aberffraw family in Gwynedd, a series of successful rulers such as Gruffudd ap Cynan

Gruffudd ap Cynan ( 1137), sometimes written as Gruffydd ap Cynan, was King of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137. In the course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh resistance to Norman rule, and was rememb ...

and Owain Gwynedd

Owain ap Gruffudd ( 23 or 28 November 1170) was King of Gwynedd, North Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called Owain the Great ( cy, Owain Fawr) and the first to be ...

in the late 11th and 12th centuries, and Llywelyn the Great and his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

in the 13th century, led to the emergence of the Principality of Wales

The Principality of Wales ( cy, Tywysogaeth Cymru) was originally the territory of the native Welsh princes of the House of Aberffraw from 1216 to 1283, encompassing two-thirds of modern Wales during its height of 1267–1277. Following the co ...

, based on Gwynedd.

The emergence of the principality in the 13th century showed that all the elements necessary for the growth of Welsh statehood were in place, and that Wales was independent ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'', according to historian Dr John Davies.Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''emerging defacto statehood'' pg 148 As part of the Principality of Wales, Gwynedd retained Welsh laws and customs and home rule until the Edwardian Conquest of Wales

The conquest of Wales by Edward I took place between 1277 and 1283. It is sometimes referred to as the Edwardian Conquest of Wales,Examples of historians using the term include Professor J. E. Lloyd, regarded as the founder of the modern academi ...

of 1282.

Settlements, architecture, and economy

When Gruffudd ap Cynan died in 1137 he left a more stable realm than had existed in Gwynedd for more than 100 years.Lloyd, J.E. ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'', Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. 2004, ''Gruffyd's legacy'' pg 79, 80 No foreign army was able to cross the Conwy into upper Gwynedd. The stability in upper Gwynedd provided by Gruffudd and his son Owain Gwynedd, between 1101 and 1170, allowed Gwynedd's inhabitants to plan for the future without fear that home and harvest would "go to the flames" from invaders. Settlements in Gwynedd became more permanent, with buildings of stone replacing timber structures. Stone churches in particular were built across Gwynedd, with so many limewashed that "Gwynedd was bespangled with them as is thefirmament

In biblical cosmology, the firmament is the vast solid dome created by God during his creation of the world to divide the primal sea into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear. The concept was adopted into the subsequent ...

with stars". Gruffudd had built stone churches at his princely manors, and Lloyd suggests that his example led to the rebuilding of churches in stone in Penmon, Aberdaron, and Towyn

Towyn ( cy, Tywyn) is a seaside resort in the Conwy County Borough, Wales. It is also an electoral ward to the town and county councils.

Location

It is located between Rhyl, in Denbighshire, and Abergele in Conwy.

Demography

According to th ...

in the Norman fashion.

By the 13th century, Gwynedd was the cornerstone of the Principality of Wales (that is ''Pura Wallia''), which came to encompass three-quarters of the area of modern Wales: "from Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

to Machen

Machen (from Welsh ' "place (of)" + ', a personal name) is a large village three miles east of Caerphilly, south Wales. It is situated in the Caerphilly borough within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire. It neighbours Bedwas and Trethom ...

, from the outskirts of Chester to the outskirts of Cydweli".Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''Aberffraw stability'' and ''effects on population'', ''town-dwellers'', ''decline in slavery'', page 151Lloyd, J.E., ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'', ''Aberffraw stability'' pg 219, 220 By 1271, Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd could claim a growing population of about 200,000: a little less than three-quarters of the total Welsh population.The emergence of the principality of Wales/ref>

Population increase was common throughout Europe in the 13th century, but in Wales it was more pronounced. By Llywelyn II's reign as much as 10 per cent of the population were town-dwellers. Additionally, "unfree slaves... had long disappeared" from within ''Pura Wallia'' due in large part form the social upheavals of the 11th century," argued Davies. The increase in free men allowed the prince to call on and field a far more substantial and professional army.

The increase in population in Gwynedd, and in the Principality of Wales as a whole, allowed a greater diversification of the economy. The Meirionnydd tax rolls evidence the thirty-seven various professions present in Meirionnydd immediately before the Edwardian Conquest of 1282.

Of these professions, there were eight

Population increase was common throughout Europe in the 13th century, but in Wales it was more pronounced. By Llywelyn II's reign as much as 10 per cent of the population were town-dwellers. Additionally, "unfree slaves... had long disappeared" from within ''Pura Wallia'' due in large part form the social upheavals of the 11th century," argued Davies. The increase in free men allowed the prince to call on and field a far more substantial and professional army.

The increase in population in Gwynedd, and in the Principality of Wales as a whole, allowed a greater diversification of the economy. The Meirionnydd tax rolls evidence the thirty-seven various professions present in Meirionnydd immediately before the Edwardian Conquest of 1282.

Of these professions, there were eight goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and servicea ...

s, four professional bards (poets), 26 shoemakers

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or cobblers (also known as ''cordwainers''). In the 18th century, dozens or even hundreds of masters, journeymen an ...

, a doctor in Cynwyd and an hotel keeper in Maentwrog

Maentwrog () is a village and community in the Welsh county of Merionethshire (now part of Gwynedd), lying in the Vale of Ffestiniog just below Blaenau Ffestiniog, within the Snowdonia National Park. The River Dwyryd runs alongside the vi ...

, and 28 priests, two of whom were university graduates. Also present were a significant number of fishermen

A fisher or fisherman is someone who captures fish and other animals from a body of water, or gathers shellfish.

Worldwide, there are about 38 million commercial and subsistence fishers and fish farmers. Fishers may be professional or recreati ...

, administrators and clerics, professional men and craftsmen.

With the average temperature of Wales a degree or two higher than it is today, more Welsh lands were arable: "a crucial bonus for a country like Wales", wrote historian Dr John Davies.Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''agriculture'' pg 150

Important for Gwynedd and ''Pura Wallia'' were more developed trade routes

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

, which allowed the introduction of the windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

, the fulling-mill, and the horse collar

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to whi ...

(which doubled the useful power of the horse).

Gwynedd exported cattle, skins, cheese, timber, horses, wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

, dogs, hawks, and fleeces

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

, and also flannel

Flannel is a soft woven fabric, of various fineness. Flannel was originally made from carded wool or worsted yarn, but is now often made from either wool, cotton, or synthetic fiber. Flannel is commonly used to make tartan clothing, blankets, ...

(with the growth of fulling mills). Flannel was second only to cattle among the principality's exports. In exchange, the principality imported salt, wine, wheat, and other luxuries from London and Paris. But most importantly for its defence, Gwynedd also imported iron and specialised weaponry

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

.

England exploited Welsh dependence on foreign imports to wear down Gwynedd and the Principality of Wales in times of conflict between the two countries.

Poetry, literature, and music

The more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffudd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffudd I as reforming the orders of

The more stable social and political environment provided by the Aberffraw administration allowed the natural development of Welsh culture, particularly in literature. Tradition originating from ''The History of Gruffudd ap Cynan'' attributes Gruffudd I as reforming the orders of bards

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

and musicians. Welsh literature of the High Middle Ages demonstrated "vigour and a sense of commitment" as new ideas reached Wales, even in "the wake of the invaders", according to historian John Davies.Lloyd, J.E. ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'', Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. 2004, ''Aberffraw primacy'' pg 220 Additionally, contacts with continental Europe "sharpened Welsh pride", argues Davies.Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''Aberffraw primacy'' pg 116, ''patron of bards

In Celtic cultures, a bard is a professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's ancestors and to praise t ...

'' 117, ''Aberfraw relations with English crown'' pg 128, 135

In Welsh the poets of this period are known as ''Beirdd y Tywysogion'' (Poets of the Princes) or ''Y Gogynfeirdd'' (The Less Early Poets). The main source for the poetry of the 12th and 13th centuries is the Hendregadredd manuscript, an anthology of court poetry brought together at the Cistercian Strata Florida Abbey

Strata Florida Abbey ( cy, Abaty Ystrad Fflur) () is a former Cistercian abbey situated just outside Pontrhydfendigaid, near Tregaron in the county of Ceredigion, Wales. The abbey was founded in 1164. is a Latinisation of the Welsh ; 'Valley o ...

from about 1282 until 1350.

The bards of this period were schooled professionals and members of a guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

of poets, a kind of bardic guild whose rights and responsibilities were enshrined in native Welsh law. Members of this guild worked within a developed literary culture and with prescribed literary and oral syntax. Bardic families were common—the poet Meilyr Brydydd

Meilyr Brydydd ap Mabon ( fl. 1100–1137) is the earliest of the Welsh Poets of the Princes or ''Y Gogynfeirdd'' (The Less Early Poets) whose work has survived.

Meilyr was the court poet of Gruffudd ap Cynan (ca. 1055–1137), king of Gwynedd. ...

had a poet son and at least two poet grandsons—but it was also usual for the craft of poetry to be taught formally in bardic schools, which might only be run by the ''pencerdd'' (chief poet).

According to Welsh law, the prince retained the skills of several bards at court, the chief of which were the '' pencerdd'' and the '' bardd teulu''. The ''pencerdd'', the head bard, was the top of his profession and a special chair was set aside for him in the princely court in an honoured position next to the heir, the ''edling''. When the ''pencerdd'' performed he was expected to sing twice: once in honour of God, and once in honour of the prince. The ''bardd teulu'' was part of the prince's ''teulu'', or household guard, and was responsible for singing for the military retinue before going into battle, and also for successful military campaigns. The ''bardd teulu'' also composed for and sang to the princess, often privately at her leisure. A private performance by a bard was a sign of high status and prestige. The '' clêr'' were itinerant poet-musicians, considered the lowest tier of the poetic tradition, and often disparaged by the court poets as mere "minstrels".

The poetry praises the military prowess of the prince in a language that is deliberately antiquarian and obscure, echoing the earlier praise poetry tradition of Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the '' Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to have sung at the courts ...

. There are also some religious poems and poetry in praise of women.

With the death of the last native prince of Wales in 1282 the tradition gradually disappears. In fact, the elegy by Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch

Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch ( fl. 1277–1282) was a Welsh court poet.

Gruffudd composed a number of poems on the theme of religion. His greatest fame however, lies with his moving elegy for Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Wales

Prince of Wa ...

( fl. 1277–83) on the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

is one of the most notable poems of the era. Other prominent poets of this period associated with the court of Gwynedd include:

*Meilyr Brydydd

Meilyr Brydydd ap Mabon ( fl. 1100–1137) is the earliest of the Welsh Poets of the Princes or ''Y Gogynfeirdd'' (The Less Early Poets) whose work has survived.

Meilyr was the court poet of Gruffudd ap Cynan (ca. 1055–1137), king of Gwynedd. ...

, fl. ca. 1100–1137; the earliest of the ''Gogynfeirdd''

*Llywarch ap Llywelyn

Llywarch ap Llywelyn ( fl. 1173–1220) was an important medieval Welsh poet. He is also known by his bardic name, "Prydydd y Moch" ("poet of the pigs").

Llywarch was a poet at the court of the kingdom of Gwynedd in the reigns of Dafydd ab Owa ...

, fl. 1174/5-1220,Lloyd, J.E. ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'' ''Hywel's succession and overthrow by Cristen and Dafydd'', pg 134 ''Dafydd takes Gwynedd by 1074'', pg 135, ''Gwynedd between 1175–1188'', pg 145 (c. 1195) sang of Llywelyn the Great's victory over Dafydd ab Owain

* Bleddyn Fardd, fl. ca. 1258–1284

*Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr

Cynddelw Brydydd Mawr ("Cynddelw the Great Poet"; wlm, Kyndelw Brydyt or ; 1155–1200), was the court poet of Madog ap Maredudd, Owain Gwynedd (Owen the Great), and Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd, and one of the most prominent Welsh poets of the 12 ...

; fl. ca. 1155–1200

* Dafydd Benfras, fl. ca. 1220–58

A rather different poet of this period was Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd

Hywel ab Owain Gwynedd (circa 11201170), Prince of Gwynedd in 1170, was a Welsh poet and military leader. Hywel was the son of Owain Gwynedd, prince of Gwynedd, and an Irishwoman named Pyfog. In recognition of this, he was also known as ''Hyw ...

(d. 1170), known as the Poet-Prince. As the son and heir of Prince Owain Gwynedd

Owain ap Gruffudd ( 23 or 28 November 1170) was King of Gwynedd, North Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called Owain the Great ( cy, Owain Fawr) and the first to be ...

, he was not a professional poet.

The Welsh Church in Gwynedd

Celtic Christian traditions

Prior to the Norman invasions between 1067–1101, Christians of Gwynedd shared many of the spiritual traditions and ecclesiastical institutions found throughout Wales and otherCeltic nations

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a people who shar ...

, customs inherited from the Celtic Christianity of the Early Middle Ages.Lloyd, J. E., ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'', Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. 2004, ''Subjection of the Welsh Church'', pgs 64–74Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''Celtic Church'', 72–79 ''Welsh Church'' pg 118Davies, John, The Celts, pg 126–155

However, Welsh ecclesiastics questioned to what degree the Papacy could impose Canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

upon them, especially with regard to the marriage of priests, the role of women both in the Church and in society, and the status of "illegitimate" children in society, with canon law conflicting with native Welsh law

Welsh law ( cy, Cyfraith Cymru) is an autonomous part of the English law system composed of legislation made by the Senedd.Law Society of England and Wales (2019)England and Wales: A World Jurisdiction of Choice eport(Link accessed: 16 March 20 ...

and customs. Welsh bishops also denied that the Archbishop of Canterbury held authority over them. Professor John Davies argued that there were dangers inherent in Welsh bishops submitting to an ecclesiastical authority "that would, by necessity, be heavily under the influence ... of an English king".

monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

communities called '' clasau'' (sing. ''clas'').

''Clasau'' were administered by an ''abod'' (abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

) and contained a number of small timber-built churches and dormitory huts.The Normans disliked Welsh timber-built churches, and this was one of their critiques of the Welsh Church to justify the Norman invasion of Wales. The Normans considered timber-built structures unworthy to house places of worship, preferring stone built churches. Welsh monasticism highly valued asceticism, and the most celebrated Welsh ascetic was the 6th century St. David, who developed a monastic rule

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set apart from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practic ...

which emphasised hard work, encouraged vegetarianism, and promoted temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

. Women, who held a higher status in Welsh law and custom than elsewhere in Europe, could hold quasi-sacerdotal (semi-priestly) roles in the Welsh Church, noted Davies. As celibacy was not an important aspect of the Welsh Church, many priests married and had children; some monasteries were single or extended family endeavours, and some ecclesiastical offices became hereditary. For many Welsh people, monasticism was a familial way of life spent in devotion to Christ. As marriage was viewed as a secular social contract and governed by well-established Welsh law, divorce was recognised by the Welsh Church.

The Diocese of Bangor

The Diocese of Bangor is a diocese of the Church in Wales in North West Wales. The diocese covers the counties of Anglesey, most of Caernarfonshire and Merionethshire and the western part of Montgomeryshire.

History

The diocese in the Welsh kingd ...

was the episcopal see for all of Upper and Lower Gwynedd.

Latin Christianity

Post-Norman Invasion Gruffydd I of Gwynedd promoted the primacy of the episcopal see of Bangor in Gwynedd, and funded the building of Bangor Cathedral during the episcopate ofDavid the Scot

David the Scot (died c. 1138) was a Welsh or Irish cleric who was Bishop of Bangor from 1120 to 1138.

There is some doubt as to David's nationality, as he is variously described as Welsh or Irish. Many Irish men living outside Ireland at this t ...

, Bishop of Bangor

The Bishop of Bangor is the ordinary of the Church in Wales Diocese of Bangor. The see is based in the city of Bangor where the bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Cathedral Church of Saint Deiniol.

The ''Report of the Commissioners appointed ...

, between 1120–1139. Gruffydd's remains were interred

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

in a tomb in the presbytery of Bangor Cathedral.

Government and law

Aberffraw's traditional sphere of influence in north Wales included the

Aberffraw's traditional sphere of influence in north Wales included the Isle of Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island, ...

as their early seat of authority, and Gwynedd Uwch Conwy (Gwynedd above the Conway, or Upper Gwynedd), and the Perfeddwlad

Perfeddwlad or Y Berfeddwlad was an historic name for the territories in Wales lying between the River Conwy and the River Dee. comprising the cantrefi of Rhos, Rhufoniog, Dyffryn Clwyd and Tegeingl. Perfeddwlad thus was also known as the Four ...

("the Middle Country"), also known as Gwynedd Is Conwy (Gwynedd below the Conwy, or Lower Gwynedd). Additional lands were acquired through vassalage or conquest, and by regaining lands lost to Marcher lords

A Marcher lord () was a noble appointed by the king of England to guard the border (known as the Welsh Marches) between England and Wales.

A Marcher lord was the English equivalent of a margrave (in the Holy Roman Empire) or a marquis (in F ...

, particularly those of Ceredigion

Ceredigion ( , , ) is a county in the west of Wales, corresponding to the historic county of Cardiganshire. During the second half of the first millennium Ceredigion was a minor kingdom. It has been administered as a county since 1282. Cer ...

, Powys Fadog

Powys Fadog (English: ''Lower Powys'' or ''Madog's Powys'') was the northern portion of the former princely realm of Powys, which split in two following the death of Madog ap Maredudd in 1160. The realm was divided under Welsh law, with Madog's ...

, and Powys Wenwynwyn

Powys Wenwynwyn or Powys Cyfeiliog was a Welsh kingdom which existed during the high Middle Ages. The realm was the southern portion of the former princely state of Powys which split following the death of Madog ap Maredudd of Powys in 1160: the ...

. However these areas were always considered additions to Gwynedd, never as part of Gwynedd itself.

The extent of the kingdom varied with the strength of the current ruler. The kingdom was administered under Welsh custom through 13 '' cantrefi'' (hundreds, plural of ''cantref''), each containing, in theory, one hundred settlements or ''trefi''. Most ''cantrefi'' were divided further into cymydau (English: commote

A commote (Welsh ''cwmwd'', sometimes spelt in older documents as ''cymwd'', plural ''cymydau'', less frequently ''cymydoedd'')''Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru'' (University of Wales Dictionary), p. 643 was a secular division of land in Medieval Wales ...

s).

Gwynedd at war

According to Sir John Edward Lloyd, the challenges of campaigning in Gwynedd and Wales as a whole were exposed during the Norman invasions between 1081 and 1101. If a defender could bar any road, control any river crossing or mountain pass, and control the coastline around Wales, then the risks of extended campaigning in Wales were too great. With control of the Menai, an army could regroup onAnglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

; without control of the Menai an army could be stranded there, and any occupying force on Anglesey could deny the vast harvest of that island to the Welsh. And the Welsh throughout Wales could lead retaliatory strikes from mountain strongholds or remote forested glens.Davies, John, ''A History of Wales'', Penguin, 1994, ''Gruffydd ap Cynan''; ''Battle of Mynydd Carn, Norman Invasion'', pg 104–108, ''reconstructing Gwynedd'' pg 116,

The Welsh were revered for the skills of their bowmen; and they learned from the Normans. During the generations of warfare and close contact with the Normans, Gruffydd I and other Welsh leaders learned the arts of knighthood and adapted them for Wales. By Gruffydd's death in 1137, Gwynedd could field hundreds of heavy well-armed cavalry as well as their traditional bowmen and infantry.

In the end Wales was defeated militarily by the improved ability of the English navy to blockade or seize areas essential for agricultural production, such as Anglesey. Lack of food would force the disbandment of any large Welsh force besieged in the mountains. Following the occupation, Welsh soldiers were conscripted to serve in the English army. During the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr the Welsh adapted the new skills they had learnt to guerilla tactics and lightning raids. Owain reputedly used the mountains to such advantage that many of the exasperated English soldiery suspected him of being a magician able to control the natural elements.

Notes

References

* BBC Wales/History''The emergence of the principality of Wales''

extracted 26 March 2008 * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Culture Of Gwynedd During The High Middle Ages Kingdom of Gwynedd Gwynedd High Middle Ages Culture High Middle Ages Culture Gwynedd, Culture