Copernican Revolution (metaphor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Copernican Revolution was the

The Copernican Revolution was the

Copernicus studied at Bologna University during 1496–1501, where he became the assistant of

Copernicus studied at Bologna University during 1496–1501, where he became the assistant of

Galileo Galilei was an Italian scientist who is sometimes referred to as the "father of modern

Galileo Galilei was an Italian scientist who is sometimes referred to as the "father of modern

Andrew Motte Translation

/ref> He was a main figure in the

The Copernican Revolution was the

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift

A paradigm shift, a concept brought into the common lexicon by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn, is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. Even though Kuhn restricted ...

from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

with the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

at the center of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

. This revolution consisted of two phases; the first being extremely mathematical in nature and the second phase starting in 1610 with the publication of a pamphlet by Galileo. Beginning with the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

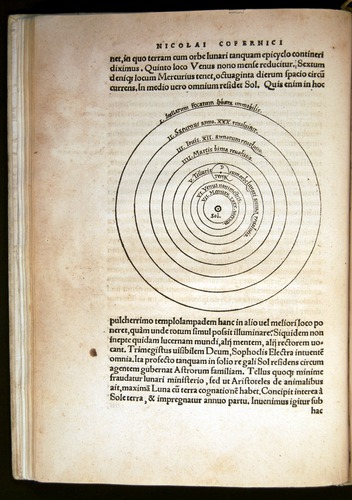

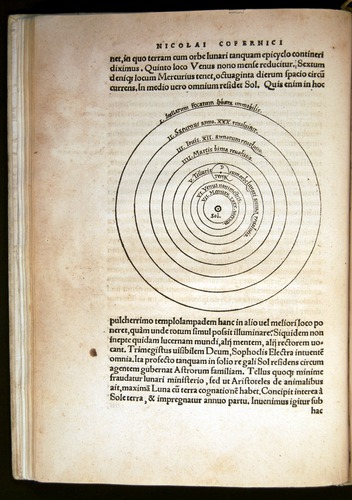

’s ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

'', contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

’s work over a century later.

Heliocentrism

Before Copernicus

The "Copernican Revolution" is named forNicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

, whose '' Commentariolus'', written before 1514, was the first explicit presentation of the heliocentric model in Renaissance scholarship.

The idea of heliocentrism is much older; it can be traced to Aristarchus of Samos, a Hellenistic author writing in the 3rd century BC, who may in turn have been drawing on even older concepts in Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

. Ancient heliocentrism was, however, eclipsed by the geocentric model presented by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

in the Almagest and accepted in Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the so ...

.

European scholars were well aware of the problems with Ptolemaic astronomy since the 13th century. The debate was precipitated by the reception

Reception is a noun form of ''receiving'', or ''to receive'' something, such as art, experience, information, people, products, or vehicles. It may refer to:

Astrology

* Reception (astrology), when a planet is located in a sign ruled by another ...

by Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

' criticism of Ptolemy, and it was again revived by the recovery of Ptolemy's text and its translation into Latin in the mid-15th century. Otto E. Neugebauer in 1957 argued that the debate in 15th-century Latin scholarship must also have been informed by the criticism of Ptolemy produced after Averroes, by the Ilkhanid

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm, ...

-era (13th to 14th centuries) Persian school of astronomy associated with the

Maragheh observatory (especially the works of Al-Urdi

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert ...

, Al-Tusi Al-Tusi or Tusi is the title of several Iranian scholars who were born in the town of Tous in Khorasan. Some of the scholars with the al-Tusi title include:

* Abu Nasr as-Sarraj al-Tūsī (d. 988), Sufi sheikh and historian.

*Aḥmad al Ṭūsī ( ...

and Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

).

The state of the question as received by Copernicus is summarized in the ''Theoricae novae planetarum'' by Georg von Peuerbach

Georg von Peuerbach (also Purbach, Peurbach; la, Purbachius; born May 30, 1423 – April 8, 1461) was an Austrian astronomer, poet, mathematician and instrument maker, best known for his streamlined presentation of Ptolemaic astronomy in the ''Th ...

, compiled from lecture notes by Peuerbach's student Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

in 1454 but printed only in 1472.

Peuerbach attempts to give a new, mathematically more elegant presentation of Ptolemy's system, but he does not arrive at heliocentrism.

Regiomontanus himself was the teacher of Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara

Domenico Maria Novara (1454–1504) was an Italian scientist.

Life

Born in Ferrara, for 21 years he was professor of astronomy at the University of Bologna, and in 1500 he also lectured in mathematics at Rome. He was notable as a Platonist ast ...

, who was in turn the teacher of Copernicus.

There is a possibility that Regiomontanus already arrived at a theory of heliocentrism before his death in 1476, as he paid particular attention to the heliocentric theory of Aristarchus in a later work, and mentions the "motion of the Earth" in a letter.

Nicolaus Copernicus

Copernicus studied at Bologna University during 1496–1501, where he became the assistant of

Copernicus studied at Bologna University during 1496–1501, where he became the assistant of Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara

Domenico Maria Novara (1454–1504) was an Italian scientist.

Life

Born in Ferrara, for 21 years he was professor of astronomy at the University of Bologna, and in 1500 he also lectured in mathematics at Rome. He was notable as a Platonist ast ...

. He is known to have studied the ''Epitome in Almagestum Ptolemei'' by Peuerbach and Regiomontanus (printed in Venice in 1496) and to have performed observations of lunar motions on 9 March 1497. Copernicus went on to develop an explicitly heliocentric model of planetary motion, at first written in his short work '' Commentariolus'' some time before 1514, circulated in a limited number of copies among his acquaintances. He continued to refine his system until publishing his larger work, ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (1543), which contained detailed diagrams and tables.

The Copernican model makes the claim of describing the physical reality of the cosmos, something which the Ptolemaic model was no longer believed to be able to provide.

Copernicus removed Earth from the center of the universe, set the heavenly bodies in rotation around the Sun, and introduced Earth's daily rotation on its axis.Osler (2010), p. 44 While Copernicus's work sparked the "Copernican Revolution", it did not mark its end. In fact, Copernicus's own system had multiple shortcomings that would have to be amended by later astronomers.

Copernicus did not only come up with a theory regarding the nature of the sun in relation to the earth, but thoroughly worked to debunk some of the minor details within the geocentric theory. In his article about heliocentrism as a model, author Owen Gingerich writes that in order to persuade people of the accuracy of his model, Copernicus created a mechanism in order to return the description of celestial motion to a “pure combination of circles.” Copernicus’s theories made a lot of people uncomfortable and somewhat upset. Even with the scrutiny that he faced regarding his conjecture that the universe was not centered around the Earth, he continued to gain support- other scientists and astrologists even posited that his system allowed a better understanding of astronomy concepts than did the geocentric theory.

Reception

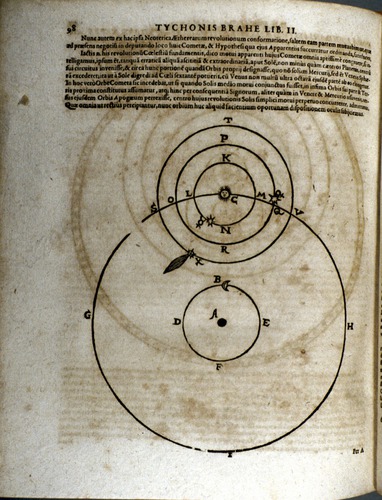

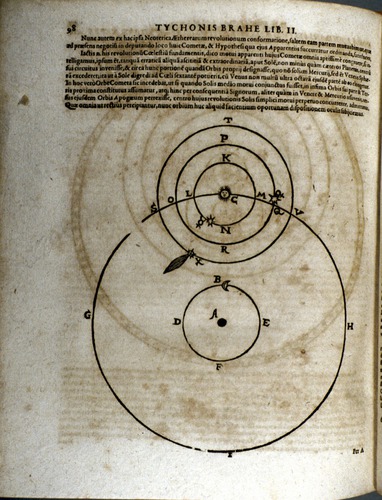

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

(1546–1601) was a Danish nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteris ...

who was well known as an astronomer in his time. Further advancement in the understanding of the cosmos would require new, more accurate observations than those that Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

relied on and Tycho made great strides in this area. Tycho formulated a geoheliocentrism, meaning the Sun moved around the Earth while the planets orbited the Sun, known as the Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

. Although Tycho appreciated the advantages of Copernicus's system, he like many others could not accept the movement of the Earth.

In 1572, Tycho Brahe observed a new star in the constellation Cassiopeia. For eighteen months, it shone brightly in the sky with no visible parallax, indicating it was part of the heavenly region of stars according to Aristotle's model. However, according to that model, no change could take place in the heavens so Tycho's observation was a major discredit to Aristotle's theories. In 1577, Tycho observed a great comet in the sky. Based on his parallax observations, the comet passed through the region of the planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s. According to Aristotelian theory, only uniform circular motion on solid spheres existed in this region, making it impossible for a comet to enter this region. Tycho concluded there were no such spheres, raising the question of what kept a planet in orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as ...

.Osler (2010), p. 53

With the patronage of the King of Denmark, Tycho Brahe established Uraniborg, an observatory in Hven.J J O'Connor and E F Robertson. Tycho Brahe biography. April 2003. Retrieved 2008-09-28 For 20 years, Tycho and his team of astronomers compiled astronomical observations that were vastly more accurate than those made before. These observations would prove vital in future astronomical breakthroughs.

Johannes Kepler

Kepler found employment as an assistant to Tycho Brahe and, upon Brahe's unexpected death, replaced him as imperial mathematician ofEmperor Rudolph II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the Hous ...

. He was then able to use Brahe's extensive observations to make remarkable breakthroughs in astronomy, such as the three laws of planetary motion. Kepler would not have been able to produce his laws without the observations of Tycho, because they allowed Kepler to prove that planets traveled in ellipses, and that the Sun does not sit directly in the center of an orbit but at a focus. Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He wa ...

came after Kepler and developed his own telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

with enough magnification to allow him to study Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

and discover that it has phases like a moon. The discovery of the phases of Venus was one of the more influential reasons for the transition from geocentrism

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, a ...

to heliocentrism.Thoren (1989), p. 8 Sir Isaac Newton's '' Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica'' concluded the Copernican Revolution. The development of his laws of planetary motion and universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the dist ...

explained the presumed motion related to the heavens by asserting a gravitational force of attraction between two objects.

In 1596, Kepler published his first book, the ''Mysterium Cosmographicum

''Mysterium Cosmographicum'' (lit. ''The Cosmographic Mystery'', alternately translated as ''Cosmic Mystery'', ''The Secret of the World'', or some variation) is an astronomy book by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler, published at Tübingen i ...

'', which was the second (after Thomas Digges

Thomas Digges (; c. 1546 – 24 August 1595) was an English mathematician and astronomer. He was the first to expound the Copernican system in English but discarded the notion of a fixed shell of immoveable stars to postulate infinitely many s ...

, in 1576) to endorse Copernican cosmology by an astronomer since 1540. The book described his model that used Pythagorean mathematics and the five Platonic solids

In geometry, a Platonic solid is a convex, regular polyhedron in three-dimensional Euclidean space. Being a regular polyhedron means that the faces are congruent (identical in shape and size) regular polygons (all angles congruent and all edges c ...

to explain the number of planets, their proportions, and their order. The book garnered enough respect from Tycho Brahe to invite Kepler to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

and serve as his assistant.

In 1600, Kepler set to work on the orbit of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, the second most eccentric of the six planets known at that time. This work was the basis of his next book, the ''Astronomia nova

''Astronomia nova'' (English: ''New Astronomy'', full title in original Latin: ) is a book, published in 1609, that contains the results of the astronomer Johannes Kepler's ten-year-long investigation of the motion of Mars.

One of the most s ...

'', which he published in 1609. The book argued heliocentrism and ellipses for planetary orbits instead of circles modified by epicycles. This book contains the first two of his eponymous three laws of planetary motion. In 1619, Kepler published his third and final law which showed the relationship between two planets instead of single planet movement.

Kepler's work in astronomy was new in part. Unlike those who came before him, he discarded the assumption that planets moved in a uniform circular motion, replacing it with elliptical motion. Also, like Copernicus, he asserted the physical reality of a heliocentric model as opposed to a geocentric one. Yet, despite all of his breakthroughs, Kepler could not explain the physics that would keep a planet in its elliptical orbit.

Kepler's laws of planetary motion

:1. The Law of Ellipses: All planets move in elliptical orbits, with the Sun at one focus. :2. The Law of Equal Areas in Equal Time: A line that connects a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times. :3. The Law of Harmony: The time required for a planet to orbit the Sun, called its period, is proportional to long axis of the ellipse raised to the 3/2 power. The constant of proportionality is the same for all the planets.Galileo Galilei

observational astronomy

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical ...

".Singer (1941), p. 217 His improvements to the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

, astronomical observations, and support for Copernicanism were all integral to the Copernican Revolution.

Based on the designs of Hans Lippershey

Hans Lipperhey (circa 1570 – buried 29 September 1619), also known as Johann Lippershey or Lippershey, was a German- Dutch spectacle-maker. He is commonly associated with the invention of the telescope, because he was the first one who tried to ...

, Galileo designed his own telescope which, in the following year, he had improved to 30x magnification.Drake (1990), pp. 133-134 Using this new instrument, Galileo made a number of astronomical observations which he published in the ''Sidereus Nuncius

''Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually ''Sidereal Messenger'', also ''Starry Messenger'' or ''Sidereal Message'') is a short Astronomy, astronomical treatise (or ''pamphlet'') published in New Latin by Galileo Galilei on March 13, 1610. It was the first ...

'' in 1610. In this book, he described the surface of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

as rough, uneven, and imperfect. He also noted that "the boundary dividing the bright from the dark part does not form a uniformly oval line, as would happen in a perfectly spherical solid, but is marked by an uneven, rough, and very sinuous line, as the figure shows."Galileo, Helden (1989), p. 40 These observations challenged Aristotle's claim that the Moon was a perfect sphere and the larger idea that the heavens were perfect and unchanging.

Galileo's next astronomical discovery would prove to be a surprising one. While observing Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandth t ...

over the course of several days, he noticed four stars close to Jupiter whose positions were changing in a way that would be impossible if they were fixed stars. After much observation, he concluded these four stars were orbiting the planet Jupiter and were in fact moons, not stars.Drake (1978), p. 152 This was a radical discovery because, according to Aristotelian cosmology, all heavenly bodies revolve around the Earth and a planet with moons obviously contradicted that popular belief.Drake (1978), p. 157 While contradicting Aristotelian belief, it supported Copernican cosmology which stated that Earth is a planet like all others.Osler (2010), p. 63

In 1610, Galileo observed that Venus had a full set of phases, similar to the phases of the moon we can observe from Earth. This was explainable by the Copernican or Tychonic systems which said that all phases of Venus would be visible due to the nature of its orbit around the Sun, unlike the Ptolemaic system which stated only some of Venus's phases would be visible. Due to Galileo's observations of Venus, Ptolemy's system became highly suspect and the majority of leading astronomers subsequently converted to various heliocentric models, making his discovery one of the most influential in the transition from geocentrism to heliocentrism.

Sphere of the fixed stars

In the sixteenth century, a number of writers inspired by Copernicus, such asThomas Digges

Thomas Digges (; c. 1546 – 24 August 1595) was an English mathematician and astronomer. He was the first to expound the Copernican system in English but discarded the notion of a fixed shell of immoveable stars to postulate infinitely many s ...

, Giordano Bruno and William Gilbert argued for an indefinitely extended or even infinite universe, with other stars as distant suns. This contrasts with the Aristotelian view of a sphere of the fixed stars. Although opposed by Copernicus and (initially) Kepler, in 1610 Galileo made his telescopic observation of the faint strip of the Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye. ...

, which he found it resolves in innumerable white star-like spots, presumably farther stars themselves. By the middle of the 17th century this new view became widely accepted, partly due to the support of René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Ma ...

.

Isaac Newton

Newton was a well known Englishphysicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

who was known for his book '' Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica''.See the ''Principia'' online aAndrew Motte Translation

/ref> He was a main figure in the

Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

for his laws of motion and universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation is usually stated as that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the dist ...

. The laws of Newton are said to be the ending point of the Copernican Revolution.

Newton used Kepler's laws of planetary motion to derive his law of universal gravitation. Newton's law of universal gravitation was the first law he developed and proposed in his book ''Principia''. The law states that any two objects exert a gravitational force

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong ...

of attraction on each other. The magnitude of the force is proportional to the product of the gravitational masses of the objects, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Along with Newton's law of universal gravitation, the ''Principia'' also presents his three laws of motion. These three laws explain inertia, acceleration, action and reaction when a net force is applied to an object.

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

in his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1787 edition) drew a parallel between the "Copernican revolution" and the epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epis ...

of his new transcendental philosophy. Kant's comparison is made in the Preface to the second edition of the ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (published in 1787; a heavy revision of the first edition of 1781). Kant argues that, just as Copernicus moved from the supposition of heavenly bodies revolving around a stationary spectator to a moving spectator, so metaphysics, "proceeding precisely on the lines of Copernicus' primary hypothesis", should move from assuming that "knowledge must conform to objects" to the supposition that "objects must conform to our a_priori''.html" ;"title="A_priori_knowledge.html" ;"title="'A priori knowledge">a priori''">A_priori_knowledge.html" ;"title="'A priori knowledge">a priori''knowledge".

Much has been said on what Kant meant by referring to his philosophy as "proceeding precisely on the lines of Copernicus' primary hypothesis". There has been a long-standing discussion on the appropriateness of Kant's analogy because, as most commentators see it, Kant inverted Copernicus' primary move.

According to Tom Rockmore, Kant himself never used the "Copernican revolution" phrase about himself, though it was "routinely" applied to his work by others.

Metaphorical usage

Following Kant, the phrase "Copernican Revolution" in the 20th century came to be used for any (supposed)paradigm shift

A paradigm shift, a concept brought into the common lexicon by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn, is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. Even though Kuhn restricted ...

, for example in reference to Freudian

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might b ...

or postmodern critical theory." Jacques Lacan's formulation that the unconscious, as it reveals itself in analytic phenomena, ‘is structured like a language’, can be seen as a Copernican revolution (of sorts), bringing together Freud and the insights of linguistic philosophers and theorists such as Roman Jakobson

Roman Osipovich Jakobson (russian: Рома́н О́сипович Якобсо́н; October 11, 1896Kucera, Henry. 1983. "Roman Jakobson." ''Language: Journal of the Linguistic Society of America'' 59(4): 871–883. – July 18,

https://www.qdl.qa/en/arabic-translations-ptolemys-almagest .

*Koyré, Alexandre (2008). ''From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe''. Charleston, S.C.: Forgotten Books. .

*Lawson, Russell M. ''Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia''. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

* Lin, Justin Y. (1995). ''The Needham Puzzle: Why the Industrial Revolution Did Not Originate in China.'' ''Economic Development and Cultural Change'', 43(2), 269–292. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1154499 .

* Metzger, Hélène (1932). Histoire des sciences. ''Revue Philosophique De La France Et De L'Étranger,'' ''114'', 143–155. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41086443 .

*

*

*Rushkin, Ilia. "Optimizing the Ptolemaic Model of Planetary and Solar Motion". ''History and Philosophy of Physics'' 1 (February 6, 2015): 1–13.

*Saliba, George (1979). "The First Non-Ptolemaic Astronomy at the Maraghah School". ''Isis''. 70 (4). https://www.maa.org/press/periodicals/convergence/mathematical-treasure-ptolemy-s-almagest .

*

See also

*History of science in the Renaissance

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, mathematics, manufacturing, anatomy and engineering. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and co ...

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * *Gillies, Donald. (2019). Why did the Copernican revolution take place in Europe rather than China?. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332320835_Why_did_the_Copernican_revolution_take_place_in_Europe_rather_than_China *Gingerich, Owen. "From Copernicus to Kepler: Heliocentrism as Model and as Reality". ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 117, no. 6 (December 31, 1973): 513–22. *Huff, Toby E. (2017). ''The Rise of Early Modern Science''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . *Huff, Toby E. (Autumn–Winter 2002). "The Rise of Early Modern Science: A Reply to George Sabila". ''Bulletin of the Royal Institute of Inter-Faith Studies (BRIIFS)''. 4, 2. * *Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions''. Chicago: Chicago University Press. . *Kunitzch, Paul. "The Arabic Translations of Ptolemy's Almagest". Qatar Digital Library, July 31, 2018.ISSN

An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) is an eight-digit serial number used to uniquely identify a serial publication, such as a magazine. The ISSN is especially helpful in distinguishing between serials with the same title. ISSNs ...

0021-1753.

*Sabila, George (Autumn 1999). "Seeking the Origins of Modern Science?". ''Bulletin of the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies (BRIIFS)''. 1, 2.

*Sabila, George (Autumn–Winter 2002). "Flying Goats and Other Obsessions: A Response to Toby Huff's "Reply"". ''Bulletin of the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies (BRIIFS)''. 4, 2.

*

*Swetz, Frank J. "Mathematical Treasure: Ptolemy's Almagest". Mathematical Treasure: Ptolemy's Almagest , Mathematical Association of America, August 2013. External links

* * {{Authority control History of astronomyRevolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

Scientific revolution