The Constitutional Act of the Realm of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Riges Grundlov), also known as the Constitutional Act of the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply the Constitution ( da, Grundloven, fo, Grundlógin, kl, Tunngaviusumik inatsit), is the

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

of the

Kingdom of Denmark, applying equally in the Realm of Denmark:

Denmark proper

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, established ...

,

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

and the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

. The first democratic constitution was adopted in 1849, replacing the 1665 absolutist constitution. The current constitution is from 1953. It is one of the oldest constitutions in the world.

The Constitutional Act has been changed a few times. The wording is general enough to still apply today.

The constitution defines Denmark as a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, governed through a

parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

. It creates

separations of power between the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

, which enact laws,

the government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

, which implements them, and

the courts, which makes judgment about them. In addition it gives a number of

fundamental rights

Fundamental rights are a group of rights that have been recognized by a high degree of protection from encroachment. These rights are specifically identified in a constitution, or have been found under due process of law. The United Nations' Susta ...

to people in Denmark, including

freedom of speech,

freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freed ...

,

freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline mem ...

, and

freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

. The constitution applies to all persons in Denmark, not just

Danish citizens.

Its adoption in 1849 ended an

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism (European history), Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute pow ...

and introduced

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

. Denmark celebrates the adoption of the Constitution on 5 June—the date in which the first Constitution was ratified—every year as

Constitution Day

Constitution Day is a holiday to honour the constitution of a country. Constitution Day is often celebrated on the anniversary of the signing, promulgation or adoption of the constitution, or in some cases, to commemorate the change to constitut ...

(Danish: ''Grundlovsdag'').

The main principle of the Constitutional Act was to limit the King's power (section 2).

[The Constitution of Denmark](_blank)

Accessed 14 April 2016. It creates a comparatively weak constitutional monarch who is dependent on Ministers for advice and Parliament to draft and pass

legislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolling, enacting, or promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law it may be known as a bill, and may be broadly referred to ...

. The Constitution of 1849 established a

bicameral parliament, the , consisting of the

Landsting and the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

. The most significant change in the Constitution of 1953 was the abolishment of the Landsting, leaving the

unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

Folketing. It also enshrined fundamental

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

, which remain in the current constitution: such as ''

habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' (section 71),

private property rights

Property rights are constructs in economics for determining how a resource or economic good is used and owned, which have developed over ancient and modern history, from Abrahamic law to Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Re ...

(section 72) and

freedom of speech (section 77).

The

Danish Parliament

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands an ...

() cannot make any laws which may be repugnant or contrary to the Constitutional Act. While Denmark has no

constitutional court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ...

, laws can be declared unconstitutional and rendered void by the

Supreme Court of Denmark

The Supreme Court (, lit. ''Highest Court'', , ) is the supreme court and the third and final instance in all civil and criminal cases in the Kingdom of Denmark. It is based at Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen which also houses the Danish Pa ...

.

Changes to the Act must be passed by the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

in two consecutive parliamentary terms and then approved by the electorate through a national

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

.

History

Background

During the

late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

and the

renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

, the power of the king was tempered by a

håndfæstning, a coronation charter each king had to sign before being accepted as king by the

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

. This tradition was abandoned in 1665 when King

Frederick III of Denmark managed to establish a

hereditary absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism (European history), Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute pow ...

by Lex Regia (''The Law of The King'', da, Kongeloven). This was Europe's only formal absolutist constitution. Under Lex Regia, absolute power was inherited for almost 200 years.

In the beginning of the 19th century, there was a growing democratic movement in Denmark and

King Frederick VI

Frederick VI (Danish and no, Frederik; 28 January 17683 December 1839) was King of Denmark from 13 March 1808 to 3 December 1839 and King of Norway from 13 March 1808 to 7 February 1814, making him the last king of Denmark–Norway. From 1784 ...

only made some small concessions, such as creation of ''Consultative Estate Assemblies'' () in 1834. But these only served to help the political movements, of which the

National Liberals and the

Friends of Peasants were the forerunners. When

Christian VIII became king in 1839, he continued the political line of only making small democratic concessions, while upholding the absolute monarchy.

At this time Denmark was in a

personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

between kingdom of Denmark and the duchies of

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

,

Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

, and

Lauenburg

Lauenburg (), or Lauenburg an der Elbe ( en, Lauenberg on the Elbe), is a town in the state of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is situated on the northern bank of the river Elbe, east of Hamburg. It is the southernmost town of Schleswig-Holstein ...

called ''The Unitary State'' (Danish: ''Helstaten''), but the

Schleswig-Holstein question

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Schl ...

was causing tension. Under the slogan ''Denmark to the

Eider

Eiders () are large seaducks in the genus ''Somateria''. The three extant species all breed in the cooler latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

The down feathers of eider ducks, and some other ducks and geese, are used to fill pillows and quil ...

'', the National Liberals campaigned for Schleswig to become an integral part of Denmark, while separating Holstein and Lauenburg from Denmark. Holstein and Lauenburg were then part of the

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

, while Schleswig was not. On the other side, German nationalists in Schleswig were keen to keep Schleswig and Holstein together, and wanted Schleswig to join the German Confederation.

Christian VIII had reached the conclusion that, should the Unitary State survive, a constitution covering both Denmark, Schleswig and Holstein was necessary. Before his death in January 1848, he advised his

heir Frederick VII to create such a constitution.

In March 1848 following a

series of European revolutions, the Schleswig-Holstein question became increasingly tense. Following an ultimatum from Schleswig and Holstein, political pressure from the National Liberals intensified, and Frederick VII replaced the sitting government with the

March Cabinet, where four leaders of the Friends of Peasants and the National Liberals served, among those

D.G. Monrad and

Orla Lehmann

Peter Martin Orla Lehmann (15 May 1810 – 13 September 1870) was a Danish statesman, a key figure in the development of Denmark's parliamentary government.

He was born in Copenhagen, son of (1775–1856), assessor, later conference councillo ...

, both National Liberals. The ultimatum from Schleswig and Holstein was rejected, and the

First Schleswig War

The First Schleswig War (german: Schleswig-Holsteinischer Krieg) was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig-Holstein Question, contesting the issue of who should control the Duchies of Schleswi ...

started.

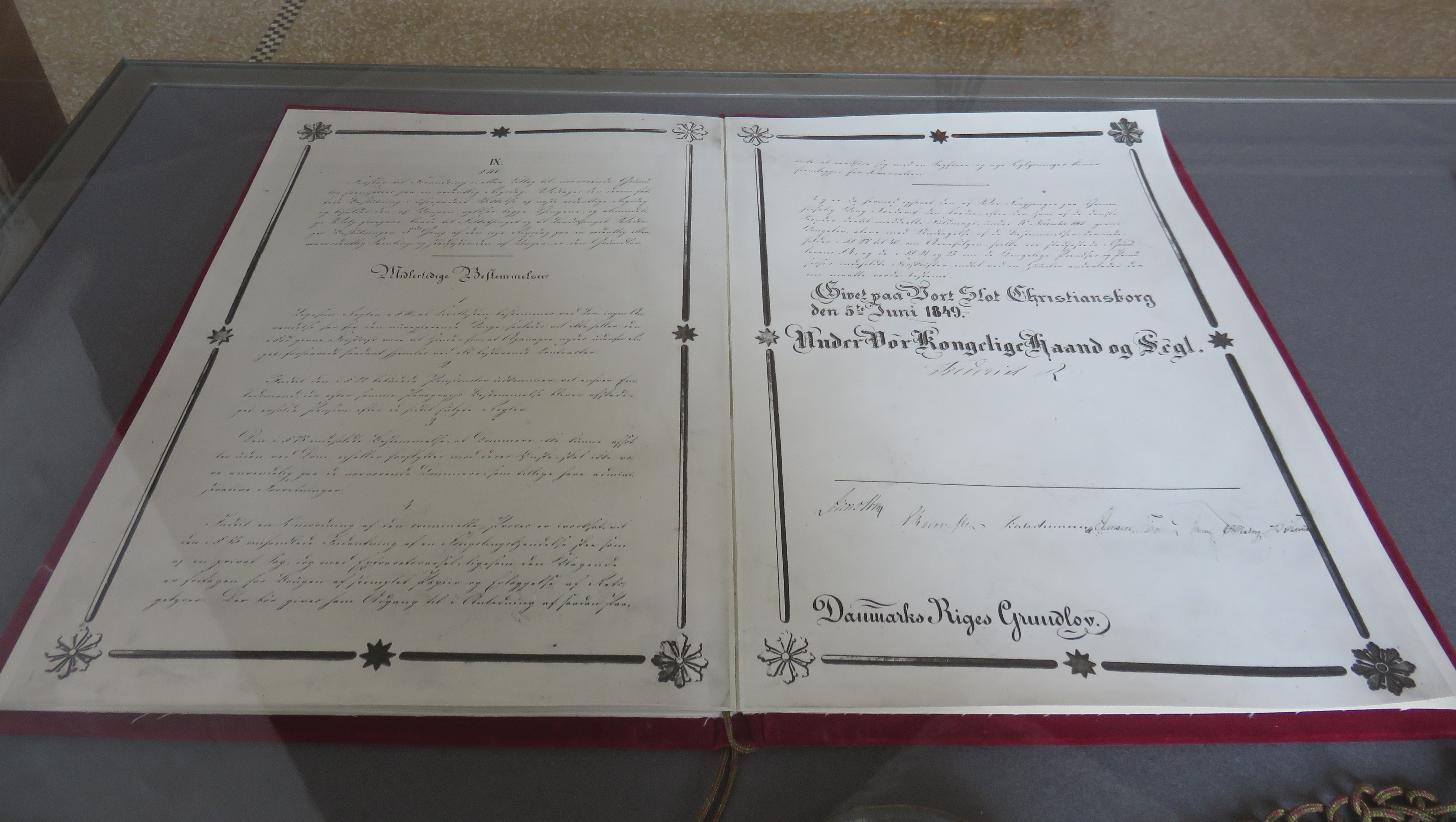

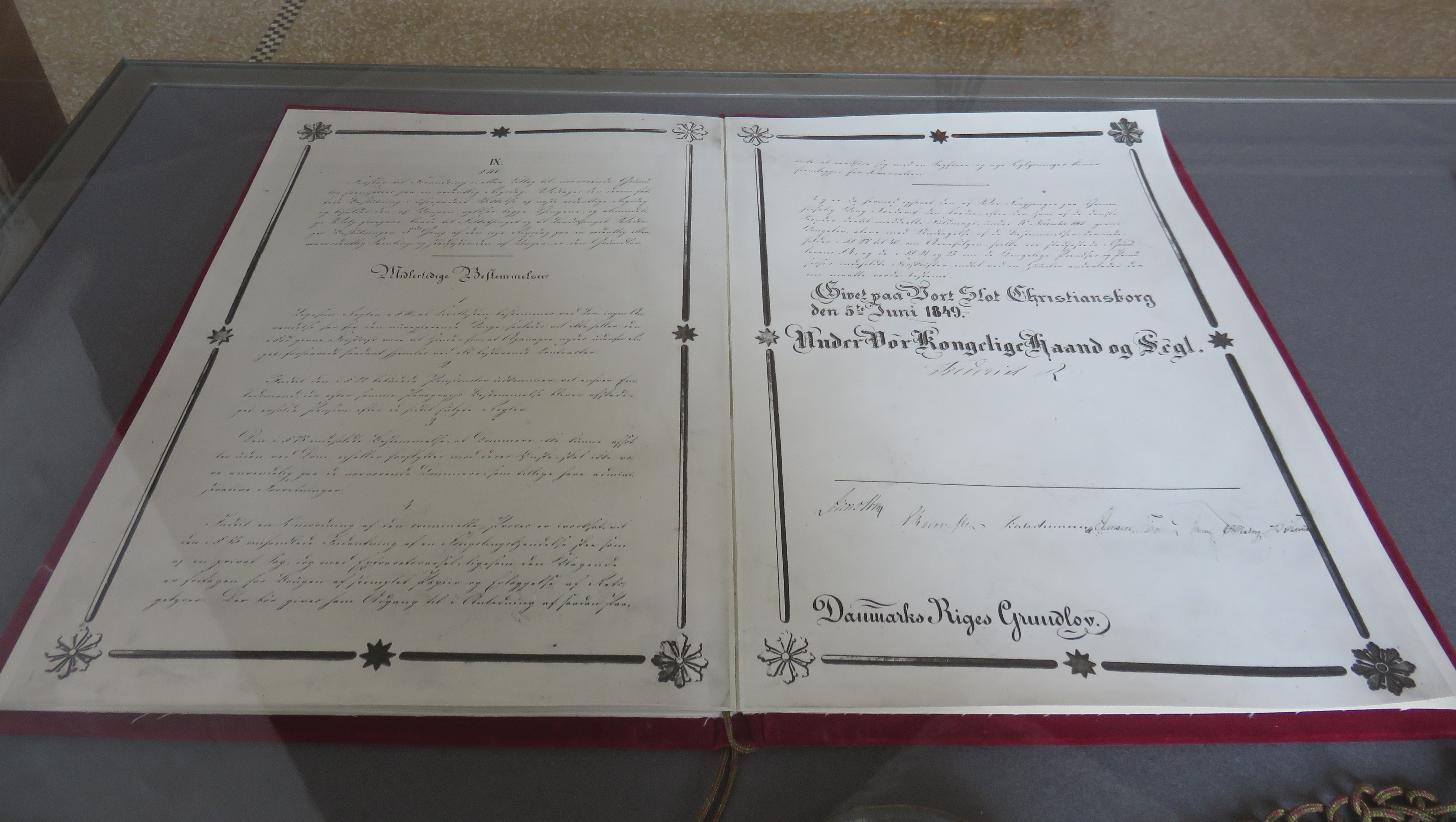

Drafting and signing of the first constitution (1849)

Monrad drafted the first draft of the Constitution, which was then edited by Lehmann. Sources of inspiration included the

Constitution of Norway of 1814 and the

Constitution of Belgium

The Constitution of Belgium ( nl, Belgische Grondwet, french: Constitution belge, german: Verfassung Belgiens) dates back to 1831. Since then Belgium has been a parliamentary monarchy that applies the principles of ministerial responsibility ...

.

The draft was laid before the ''Constitutional Assembly of the Realm'' (). This assembly, which consisted of 114 members directly elected in October 1848, and 38 members appointed by Frederick VII, was overall split in three different groupings: the National Liberals, the Friends of Peasants, and the Conservatives. A key topic for discussion was the political system, and the rules governing elections.

On 25 May 1849, the Constitutional Assembly approved the new constitution, and on 5 June 1849 it was signed by Frederick VII. For this reason, it is also known as the ''June constitution''.

Today, 5 June is known as

Constitution Day

Constitution Day is a holiday to honour the constitution of a country. Constitution Day is often celebrated on the anniversary of the signing, promulgation or adoption of the constitution, or in some cases, to commemorate the change to constitut ...

.

The new constitution establish the

Rigsdag

Rigsdagen () was the name of the national legislature of Denmark from 1849 to 1953.

''Rigsdagen'' was Denmark's first parliament, and it was incorporated in the Constitution of 1849. It was a bicameral legislature, consisting of two houses, the ...

, a

bicameral parliament, with an upper house called the

Landsting, and a lower house called the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

. While the voting rights for both chambers were the same, the elections to the Landsting was indirect, and the eligibility requirements harder. The constitution gave voting rights to 15% of the Danish population. Due to the First Schleswig war, the constitution was not put into force for Schleswig; instead this question was postponed to after the war.

Parallel constitution for the Unitary State (1855–1866)

Following the First Schleswig war, which ended in Danish victory in 1852, the

London Protocol reaffirmed the territorial integrity of the Unitary State, and solved an impending succession issue, since Frederick VII was childless. Since the June constitution was not put into force in Schleswig, the Schleswig-Holstein question remained unsolved. Work for creating a common constitution for the Unitary State started, and in 1855 the rigsdag accepted ''Helstatsforfatning (Constitution for The Unitary State),'' which covered affairs common to Denmark, Schleswig and Holstein. At the same time, the June constitution was limited to only be applicable in Denmark.

In 1863 this constitution was changed, the new one was called ''Novemberforfatningen''. This was shortly before

Second Schleswig war

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. ...

, where Denmark lost control of Schleswig and Holstein, rendering the parallel constitution void.

The Revised Constitution (1866)

In 1866, the defeat in the

Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. ...

, and the loss of

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sc ...

led to tightened election rules for the Upper Chamber, which paralyzed legislative work, leading to provisional laws.

The conservative

Højre

Højre (, ''Right'') was the name of two Danish political parties of Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The c ...

had pressed for a new constitution, giving the upper chamber of parliament more power, making it more exclusive and switching power to the conservatives from the original long standing dominance of the

National Liberals, who lost influence and was later disbanded. This long period of dominance of the Højre party under the leadership of

Jacob Brønnum Scavenius Estrup

Jacob Brønnum Scavenius Estrup, (16 April 1825 – 24 December 1913), was a Danish politician, member of the Højre party. He was Interior Minister from 1865 to 1869 in the Cabinet of Frijs and Council President as well as Finance Minist ...

with the backing of the king

Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein- ...

was named the ''provisorietid'' (provisional period) because the government was based on provisional laws instead of parliamentary decisions. This also gave rise to a conflict with the Liberals (farm owners) at that time and now known as

Venstre (Left). This constitutional battle concluded in 1901 with the so-called systemskifte (change of system) with the liberals as victors. At this point the king and Højre finally accepted

parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

as the ruling principle of Danish political life. This principle was not

codified until the 1953 constitution.

Universal suffrage (1915)

In 1915, the tightening from 1866 was reversed, and women were given the right to vote. Also, a new requirement for changing the constitution was introduced. Not only must the new constitution be passed by two consecutive parliaments, it must also pass a referendum, where 45% of the electorate must vote yes. This meant that Prime Minister

Thorvald Stauning

Thorvald August Marinus Stauning (; 26 October 1873 in Copenhagen – 3 May 1942) was the first social democratic Prime Minister of Denmark. He served as Prime Minister from 1924 to 1926 and again from 1929 until his death in 1942.

Under Stauni ...

's attempt to change the Constitution in 1939 failed.

Reunion with Schleswig (1920)

In 1920, a

new referendum was held to change the Constitution again, allowing for the reunification of Denmark following the defeat of Germany in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. This followed a

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

held in the former Danish territories of Schleswig-Holstein regarding how the new border should be placed. This resulted in upper Schleswig becoming Danish, today known as

Southern Jutland

Southern Jutland ( da, Sønderjylland; German: Südjütland) is the name for the region south of the Kongeå in Jutland, Denmark and north of the Eider (river) in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. The region north of the Kongeå is called da, Nør ...

, and the rest remained German.

Current Constitution (1953)

In 1953, the

fourth constitution abolished the Upper Chamber (the

Landsting), giving Denmark a

unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

parliament. It also enabled females to inherit the throne (see ''

Succession''), but the change still favored boys over girls (this was changed by a

referendum in 2009 so the first-born inherits the throne regardless of sex). Finally, the required number of votes in favor of a change of the Constitution was decreased to the current value of 40% of the electorate.

Summary of the constitution

The Danish constitution consists of 89 sections, structured into 11 chapters. The Folketing have published the constitution with explanatory annotations; it is available in both Danish and English through their website.

Constitutional institutions

The Constitution establishes Denmark as a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, where the

monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority and power i ...

serves as a

ceremonial Head of state. The title of monarch is

hereditary and passed on to the firstborn child, with

equal rights for sons and daughters.

The political system of Denmark can be described as a

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

with a

parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

of governance. The powers of the state is

separated into 3 different branches. The

legislative branch

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known ...

held by the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

, the

executive branch held by the

Danish government

The Cabinet of Denmark ( da, regering) has been the chief executive body and the government of the Kingdom of Denmark since 1848. The Cabinet is led by the Prime Minister. There are around 25 members of the Cabinet, known as "ministers", all of ...

, and the

judicial branch

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

held by the

Courts of Denmark

The Courts of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Domstole, fo, Danmarks Dómstólar, kl, Danmarkimi Eqqartuussiviit) is the ordinary court system of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Courts of Denmark as an organizational entity was created with the Polic ...

.

The monarchy

The Danish monarch, as the

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

, holds great ''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' power, but ''

de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' only serves as a figurehead who is not interfering in politics. The monarch formally holds

executive power

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems b ...

and, co-jointly with the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

,

legislative power

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known a ...

, since each new law requires

royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in oth ...

. By article 12, 13 and 14, the powers vested in the monarch can only be exercised through the ministers, who are responsible for all acts, thus removing any political or legal liability from the monarch.

[Grundloven, Mikael Witte 1997 ] The monarch appoints the ministers after advice from the

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

. The Prime Minister is itself appointed after advice from the leaders of the political parties of the Folketing, a process known as a ''Queen's meeting'' (). The monarch and the Cabinet attend regular meetings in the

Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

, where royal assent is given, and the monarch is regularly briefed on the political situation by the Prime Minister and Foreign minister.

The Constitution requires the monarch to be a member of the

Evangelical Lutheran Church, though not necessary the

Church of Denmark

The Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Denmark or National Church, sometimes called the Church of Denmark ( da, Folkekirken, literally: "The People's Church" or unofficially da, Den danske folkekirke, literally: "The Danish People's Church"; kl, ...

.

The government

The Government holds executive power, and is responsible for carrying out the acts of the Folketing. The Government does not have to pass a

vote of confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

before taking the seat, but any minister can be subject to a motion of no confidence. If a vote of no confidence is successfully passed against the Prime Minister, the government must resign or call a

snap election

A snap election is an election that is called earlier than the one that has been scheduled.

Generally, a snap election in a parliamentary system (the dissolution of parliament) is called to capitalize on an unusual electoral opportunity or to ...

.

The Folketing

The Folketing is the legislative branch of Denmark, and is located at

Christiansborg. It consists of 179 members, of which 2 members are elected in

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

, and 2 in the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

.

General elections is nominally held every 4 years, but the Prime Minister can at any point call a snap election. All Danish citizens over the age of 18 years who are living permanently within Denmark is eligible to vote, except those placed under

legal guardianship

A legal guardian is a person who has been appointed by a court or otherwise has the legal authority (and the corresponding duty) to make decisions relevant to the personal and property interests of another person who is deemed incompetent, call ...

. The same group of people is able to run for office. The electoral system is characterized as a

party-list proportional representation

Party-list proportional representation (list-PR) is a subset of proportional representation electoral systems in which multiple candidates are elected (e.g., elections to parliament) through their position on an electoral list. They can also be us ...

system, with an

election threshold

The electoral threshold, or election threshold, is the minimum share of the primary vote that a candidate or political party requires to achieve before they become entitled to representation or additional seats in a legislature. This limit can ...

on 2%. As a result, Denmark has a

multi-party parliamentary system, where no single party has an absolute majority.

The session starts anew each year on the first Tuesday in October, and when interrupted by a general election; all previously unfinished business is cancelled. The Folketing then elects a

speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** I ...

, who is responsible for convening meetings. The Folketing lay down their own

rules of procedure

Parliamentary procedure is the accepted rules, ethics, and customs governing meetings of an assembly or organization. Its object is to allow orderly deliberation upon questions of interest to the organization and thus to arrive at the sense or ...

, subject to the requirements in the Constitution. Among those, the required

quorum of 90 members of the Folketing, and the rule that every

proposed law requires three

readings in the Folketing, before it can be passed into law.

The Folketing also have the responsibility of holding the government accountable for the governance. The members of the Folketing does this by submitting questing to the ministers and convene them to explanatory hearings. In addition, the Folketing elect a number of ''State Auditors'' (), who has the responsibility to look through the public accounts, and check that everything is okay, and that the government only spend money approved by the Folketing. Furthermore, the Folketing also appoints an

ombudsman, who investigates wrongdoings by the public administrative authorities on behalf of the public.

The courts

The

Courts of Denmark

The Courts of Denmark ( da, Danmarks Domstole, fo, Danmarks Dómstólar, kl, Danmarkimi Eqqartuussiviit) is the ordinary court system of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Courts of Denmark as an organizational entity was created with the Polic ...

are independent of the other two branches. The Constitution does not stipulate how the courts are to be organized. Instead, this is regulated by statute. In the normal court system, there are 24 District Courts, High Courts and the

Supreme Court. In addition to these, there is some special courts. There are certain rights in the Constitution with respect to the judiciary system.

There is a special

Court of Impeachment, which can prosecute ministers for their official acts.

The court system is

able to perform judicial review of laws, i.e. check

if they are constitutional. This right is not included in the constitution, but was established by the Supreme Court in the beginning of the 20th century, when it decided to hear cases about the constitutionality of

land laws. While this right was contested in the beginning, the political system eventually accepted it. The Supreme Court have been reluctant to rule laws unconstitutional; the only time it have done so was in 1999, when it found that the

Tvind

Tvind is the informal name of a confederation of private schools, humanitarian organizations, and businesses, founded as an alternative education school in Denmark circa 1970. The organization is controversial in Denmark, where it runs a numb ...

law breached the principle of separations of power. Cases about the constitutionality of laws can only be initiated by people directly affected by the laws. All can do this with respect to the Danish relation to EU, because of its wide effects on society.

The Church of Denmark

The Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Denmark is the

state church established by the Constitution. The queen have a number of duties in the Church of Denmark, and is often considered its head, but this is not a formal role in any way.

The State Auditors

The state auditors are responsible for checking the public accounts. They are supported by

Rigsrevisionen

Rigsrevisionen is the national audit agency of the Kingdom of Denmark and an independent institution of the Folketing.

It is responsible for auditing the expenditure of Danish central government, and also public-sector bodies in which the governme ...

.

The Parliamentary Ombudsman

The Parliamentary

Ombudsman is an independent institution under the Folketing, in charge of investigating and inspecting public authorities.

It is inspired by

Swedish example, and was established in 1955, following its inclusion in the 1953 constitution. The ombudsman is both appointed by and can be dismissed by the Folketing. The ombudsman cannot be a member of the Folketing themselves. While the constitution allows the Folketing to appoint two ombudsmen, by law it only appoints one.

The current ombudsman, , is

Niels Fenger.

The ombudsman handles 4,000-5,000 complains annually from the general public, and can also open cases on its own accord. In addition to that, the ombudsman have a monitoring division that inspects prisons, psychiatric institutions and social care homes. Since 2012 it has also had a children's division.

The ombudsman cannot demand any action from the administration. It can only voice criticism and make recommendations, but these carry a lot of weight, and its recommendations are usually followed by the administration.

Civil rights

The Constitution of Denmark outlines fundamental rights in sections 71–80. Several of these are of only limited scope and thus serve as a sort of lower bar. The

European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is an international convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by ...

was introduced in Denmark by law on 29 April 1992 and supplements the mentioned paragraphs.

Personal liberty

The constitution guarantees the personal liberty. No citizen can be held in detention based on their race, religion or political views, and detention can only be used if prescribed by law. People arrested need to be put before a judge within 24 hours, known in Danish as a ''grundlovsforhør'' (lit. constitutional interrogation), who decides if the

provisional detention should be continued, and this decision can always be appealed. Special rules can apply in Greenland. Detention outside the criminal system or the immigration system, say due to

mental illness, can be brought before the courts.

Right to property

The constitution guarantees the

right to property. A

search warrant

A search warrant is a court order that a magistrate or judge issues to authorize law enforcement officers to conduct a search of a person, location, or vehicle for evidence of a crime and to confiscate any evidence they find. In most countries, ...

is needed to enter private property, confiscate things, or break the

secrecy of correspondence

__NOTOC__

The secrecy of correspondence (german: Briefgeheimnis, french: secret de la correspondance) or literally translated as secrecy of letters, is a fundamental legal principle enshrined in the constitutions of several European countries. It ...

, though general exemptions can be made by law.

Expropriations

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

must be for the public good, with full compensation, and as allowed by law. Bills regarding expropriations can by 1/3 of the Folketing be delayed until passed again after a general election. All expropriations can be brought before the courts.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press

Denmark have

freedom of speech and

freedom of press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

, but some things, say

libel or breaking

confidentiality

Confidentiality involves a set of rules or a promise usually executed through confidentiality agreements that limits the access or places restrictions on certain types of information.

Legal confidentiality

By law, lawyers are often required ...

, can still be brought before a judge.

Censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

is forbidden. §77: "Anyone is entitled to in print, writing and speech to publish his or hers thoughts, yet under responsibility to the courts. Censorship and other preventive measures can never again be introduced."

There's widespread agreement in Danish legal theory that § 77 protects what is called "formal freedom of speech" (formel ytringsfrihed), meaning that one cannot be required to submit one's speech for review by authorities before publishing or otherwise disseminating it. However, there is disagreement about whether or not § 77 covers "material freedom of speech" (materiel ytringsfrihed), the right to not be punished for one's speech. There is agreement that the phrasing "under responsibility to the courts" gives legislators some right to restrict speech, but conversely there have been several court decisions implying that some material freedom of speech does exist. The discussion is about whether the material speech has limits or not, and if so, what those limits are.

Freedom of association

All citizens have

freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline mem ...

, but associations who use violence or other illegal means can be temporarily banned by the government, while dissolution is tested in court. Dissolution of political association can always be appealed to the Supreme Court.

In 1941, during the

occupation by Nazi Germany, the Rigsdag banned the

Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

through the

communist law. The law also legalized existing internments of Danish communists, including members of the Folketing. Both the internments and the law broke rights in the constitution, but was justified by the

necessity of the situation.

The Supreme Court found the law constitutional; a decision that was criticized as the Supreme Court President had been involved in its creation. The case illustrated how long Danish politicians was willing to go to ensure Danish control of law enforcement, and that democracy can be stretched to ensure its continued existence.

In addition to the communist law, on only two occasions have an association been forcefully dissolved. In 1874, the International Workers Organization, a precursor to the

Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

, was dissolved for being revolutionary, and in 1924, the organization Nekkab was dissolved for being a meeting place for

homosexuals

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

.

In 2020, the gang

Loyal to Familia was dissolved by the Copenhagen City Court; a judgment that has been appealed. The gang was temporarily banned in 2018, and the court case – the first dissolution case against a criminal gang – was initiated. Prior to this, it has been investigated if

Hells Angels

The Hells Angels Motorcycle Club (HAMC) is a worldwide outlaw motorcycle club whose members typically ride Harley-Davidson motorcycles. In the United States and Canada, the Hells Angels are incorporated as the Hells Angels Motorcycle Corporati ...

,

Bandidos

The Bandidos Motorcycle Club, also known as the Bandido Nation, is an outlaw motorcycle club with a worldwide membership. Formed in San Leon, Texas in 1966, the Bandidos MC is estimated to have between 2,000 and 2,500 members and 303 chapters, l ...

and

Hizb ut-Tahrir

Hizb ut-Tahrir (Arabicحزب التحرير (Translation: Party of Liberation) is an international, political organization which describes its ideology as Islam, and its aim the re-establishment of the Islamic Khilafah (Caliphate) to resume Isl ...

could be banned, but the conclusions was that it would be difficult to win the cases.

Freedom of assembly

Citizens have

freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

when unarmed, though danger to public order can lead to outdoor assemblies being banned. In case of riots, the police can forcefully dissolve assemblies when they have requested the crowd to disperse "in the name of the King and the law" three times.

Freedom of religion

Section 4 establishes that the

Evangelical Lutheran Church is "the people's church" (), and as such is

supported by the state. Freedom of religion is granted in section 67, and official discrimination based on faith is forbidden in section 70.

Other rights

All children have the right to free

public education, though no duty to use it;

home schooling

Homeschooling or home schooling, also known as home education or elective home education (EHE), is the education of school-aged children at home or a variety of places other than a school. Usually conducted by a parent, tutor, or an onlin ...

and

private school

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

s are allowed. The political system shall seek to make sure that all able to work can find a job. Those unable to support themselves have the right to public support, if they submit to the related requirements. Access to professions shall only be regulated for the public good, so

trade guilds cannot regulate this themselves.

Other themes

National sovereignty

Section 20 of the current constitution establishes that the delegation of specified parts of national sovereignty to international authorities requires either a 5/6

supermajority in Parliament or an ordinary majority in both Parliament and the electorate. This section has been debated heavily in connection with Denmark's membership of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

(EU), as critics hold that changing governments have violated the Constitution by surrendering too much power.

In 1996, Prime Minister

Poul Nyrup Rasmussen

Poul Oluf Nyrup Rasmussen (, informally Poul Nyrup, born 15 June 1943) is a retired Danish politician. Rasmussen was Prime Minister of Denmark from 25 January 1993 to 27 November 2001 and President of the Party of European Socialists (PES) from ...

was sued by 12

Eurosceptics

Euroscepticism, also spelled as Euroskepticism or EU-scepticism, is a political position involving criticism of the European Union (EU) and European integration. It ranges from those who oppose some EU institutions and policies, and seek refor ...

for violating this section. The

Supreme Court acquitted Rasmussen (and thereby earlier governments dating back to 1972) but reaffirmed that there are limits to how much sovereignty can be surrendered before this becomes unconstitutional. In 2011, Prime Ministers

Lars Løkke Rasmussen

Lars Løkke Rasmussen (; born 15 May 1964) is a Danish politician who has served as Minister of Foreign Affairs since 2022. He previously served as the 25th Prime Minister of Denmark from 2009 to 2011 and again from 2015 to 2019. He was the le ...

faced a similar challenge when he was sued by 28 citizens for having adopted the European

Lisbon Treaty

The Treaty of Lisbon (initially known as the Reform Treaty) is an international agreement that amends the two treaties which form the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU). The Treaty of Lisbon, which was signed by the EU member sta ...

without a referendum. The group of professors, actors, writers and Eurosceptic politicians argued that the Lisbon Treaty hands over parts of national sovereignty to the EU and therefore a referendum should have taken place. The case was later dismissed.

Section 20 was used in 1972 when Denmark, after a

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, joined the

EEC (now

EU). More recently, in 2015 an (unsuccessful)

referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

was held on one of its EU-opt-outs.

Greenland and the Faroe Islands

As section one of the constitution states that it "shall apply to all parts of the Kingdom of Denmark", is also applies in Faroe Islands and Greenland. The Faroe Island and Greenland each elect two members to the parliament; the remaining 175 members are elected in Denmark.

The Folketing have by law given the Faroe Island and Greenland extensive autonomy; the Faroe Island was given "home rule" in 1948, and Greenland was too in 1979. Greenland's home rule was in 2009 replaced by "self rule".

There is an ongoing legal debate about what constitutional weight these arrangements have. In general, there are two conflicting views: (a) the laws delegate power from the Folketing and can be revoked unilaterally by it, and (b) the laws have special status so changes require the consent of the Faroese

Løgting or the Greenlandic

Inatsisartut

The Inatsisartut ( kl, Inatsisartut; '' da, Landstinget, lit=''the land's- thing'' of Greenland''), also known as the Parliament of Greenland in English, is the unicameral parliament (legislative branch) of Greenland, an autonomous territory* ...

, respectively.

Proponent of the first interpretation include

Alf Ross

Alf Niels Christian Ross (10 June 1899 – 17 August 1979) was a Danish jurist, legal philosopher and judge of the European Court of Human Rights (1959–1971). He is best known as one of the leading figures of Scandinavian legal realism. His de ...

,

Poul Meyer,

and

Jens Peter Christensen

Jens Peter Christensen (born 1 November 1956 in Skive) is the president of the Supreme Court of Denmark.

He finished his upper secondary level education in 1975, became a Candidate of Philosophy in 1980, Candidate of Political Science in 1982 ...

.

Ross, the chief architect of the Faeroese home rule, compared it to an extended version of the autonomy of municipalities.

Meyer wrote in 1947, prior to the Faeroese home rule, that if power was delegated as extensive in other parts of the country, it would probably breach section 2 of the 1915 constitution, suggesting it did not do that here due to the Faroe Islands' separate history.

Similarly, Christensen, a

Supreme Court judge, said that due to the special circumstances, the scope of delegation need not be strictly defined.

Proponents of the second interpretation include

Edward Mitens,

Max Sørensen

Max Sørensen (February 19, 1913 in Copenhagen – October 11, 1981 in Risskov) was a Denmark, Danish diplomat, judge, and professor of international law. He holds the distinction of being the first person to have sat as a judge on both the Euro ...

and

Frederik Harhoff

Frederik Harhoff (born 27 May 1949 in Copenhagen, Denmark) is a Danish jurist.ICTY''BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: JUDGE HARHOFF''/ref> He was a member of the faculty of the University of Copenhagen and served as an ''ad litem'' judge for the International C ...

.

Mitens, a Faeroese jurist and politician, argued that the Faeroese home rule had been approved by both the Løgting and the

Rigsdag

Rigsdagen () was the name of the national legislature of Denmark from 1849 to 1953.

''Rigsdagen'' was Denmark's first parliament, and it was incorporated in the Constitution of 1849. It was a bicameral legislature, consisting of two houses, the ...

, so it was an agreement between two parties, in particular because the approval by the Løgting happened according to special rules put in place in 1940 with the consent of the Danish representative there, during the occupation by the United Kingdom.

Sørensen said the intention with the Faeroese home rule was that it should not be unilaterally changed, as stated in the preamble, so it had that effect.

Harhoff, in his 1993

Doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

dissertation, considered the home rule acts of the Faroe Islands and Greenland to be somewhere in between the constitution and a usual act by the Folketing, as it had

been treated as such.

Separation of powers

Denmark have

separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typic ...

into the three classic branches: the legislative, held by the

Folketing

The Folketing ( da, Folketinget, ; ), also known as the Parliament of Denmark or the Danish Parliament in English, is the unicameral national legislature (parliament) of the Kingdom of Denmark—Denmark proper together with the Faroe Islands ...

; the executive held by the

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

; and the judiciary, held by the

courts

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accorda ...

. The separation of powers is described in the constitution, and is there, as in many democracies, to prevent abuse of power. The Folketing enact laws, and the government implements them. The courts make judgments in disputes, either between citizens, or between authorities and citizens.

The Constitution is heavily influenced by the French philosopher

Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

, whose separation of powers was aimed at achieving mutual monitoring of each of the branches of government. However, the division between legislative and executive power in Denmark is not as sharp as in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

.

In 1999, the Supreme Court found that the

Tvind

Tvind is the informal name of a confederation of private schools, humanitarian organizations, and businesses, founded as an alternative education school in Denmark circa 1970. The organization is controversial in Denmark, where it runs a numb ...

law, a law that barred specific schools from receiving public funding, was unconstitutional, because it breached the concept of separation of powers by settling a concrete dispute between the Tvind schools and the government. The judgment is the only time the courts have found a law to be unconstitutional.

Parliamentary power

In several sections the Constitutional Act sets out the powers and duties of the Danish Parliament. Section 15 in the Act, which deals with

the parliamentary principle, lays down that "a Minister shall not remain in office after the Parliament has passed a vote of no confidence in him".

This suggests that Ministers are accountable to Parliament and even subservient to it. The Cabinet exerts executive power through its Ministers, but cannot remain in office if the majority of the Folketing goes against it. Another important feature of the Danish parliamentary system is that the Constitutional Act lays down that "the Members of the Folketing shall be elected for a period of four years", but still, "the King may at any time issue writs for a new election".

See also

*

Codified constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princi ...

*

Constitutional economics

Constitutional economics is a research program in economics and constitutionalism that has been described as explaining the choice "of alternative sets of legal-institutional-constitutional rules that constrain the choices and activities of econo ...

*

Constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

*

Constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in fe ...

*

Index of Denmark-related articles

The following outline is provided as an overview, and topical guide to Denmark.

Denmark – country located in Scandinavia of Northern Europe. It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries. The mainland is bordered to the south by Germany ...

*

Politics of Denmark

The politics of Denmark take place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democracy, a constitutional monarchy and a decentralised unitary state in which the monarch of Denmark, Queen Margrethe II, is the head of state. Denma ...

Notes

References

External links

The Constitutional Act of Denmark- The Danish Parliament

- Ministry of Education of Denmark

{{DEFAULTSORT:Constitution Of Denmark

1849 in law

Government of Denmark

Legal history of Denmark

Politics of Denmark

History of the Faroe Islands

Politics of the Faroe Islands

History of Greenland

Politics of Greenland

1849 in Denmark

Politics of the Kingdom of Denmark

June 1849 events

During the

During the

Monrad drafted the first draft of the Constitution, which was then edited by Lehmann. Sources of inspiration included the Constitution of Norway of 1814 and the

Monrad drafted the first draft of the Constitution, which was then edited by Lehmann. Sources of inspiration included the Constitution of Norway of 1814 and the  The Constitution establishes Denmark as a

The Constitution establishes Denmark as a  The Folketing is the legislative branch of Denmark, and is located at Christiansborg. It consists of 179 members, of which 2 members are elected in

The Folketing is the legislative branch of Denmark, and is located at Christiansborg. It consists of 179 members, of which 2 members are elected in