Conservative Revolutionary movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Conservative Revolution (german: Konservative Revolution), also known as the German neoconservative movement or new nationalism, was a German

"Die Identitäre Bewegung Deutschland (IBD)–Bewegung oder virtuelles Phänomen"

''Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen'' 27, no. 3 (2014): 1–26.

Although terms such as ''Konservative Kraft'' ("conservative power") and ''schöpferische Restauration'' ("creative restoration") began to spread across German-speaking Europe from the 1900s to the 1920s, the ''Konservative Revolution'' ("Conservative Revolution") became an established concept in the

Although terms such as ''Konservative Kraft'' ("conservative power") and ''schöpferische Restauration'' ("creative restoration") began to spread across German-speaking Europe from the 1900s to the 1920s, the ''Konservative Revolution'' ("Conservative Revolution") became an established concept in the

Conservative Revolutionaries argued that their nationalism was fundamentally different from the precedent forms of German nationalism or conservatism, condemning the

Conservative Revolutionaries argued that their nationalism was fundamentally different from the precedent forms of German nationalism or conservatism, condemning the

"Young conservatives" were deeply influenced by 19th-century intellectual and aesthetic movements such as German romanticism and '' Kulturpessimismus'' ("cultural pessimism"). Contrary to traditional

"Young conservatives" were deeply influenced by 19th-century intellectual and aesthetic movements such as German romanticism and '' Kulturpessimismus'' ("cultural pessimism"). Contrary to traditional

Other Conservative Revolutionaries rather drew influence from their life at the front line (, "war experience") during the

Other Conservative Revolutionaries rather drew influence from their life at the front line (, "war experience") during the

„...habe ich geschwiegen“. Zur Frage eines Antisemitismus bei Martin Niemöller

' Despite having made remarks about Jews that some scholars have called

"Germany and the Conservative Revolution"

(English transl.). {{DEFAULTSORT:Conservative Revolutionary Movement Anti-communism in Germany Conservatism in Germany Far-right politics in Germany Right-wing ideologies Syncretic political movements Weimar culture Criticism of rationalism

national-conservative

National conservatism is a nationalist variant of conservatism that concentrates on upholding national and cultural identity. National conservatives usually combine nationalism with conservative stances promoting traditional cultural values, ...

movement prominent during the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, in the years 1918–1933 (between World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the Nazi seizure of power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

).

Conservative Revolutionaries were involved in a cultural counter-revolution and showed a wide range of diverging positions concerning the nature of the institutions Germany had to instate, labelled by historian Roger Woods

Roger Woods (born 1949) is a British contemporary historian who specialises on 20th-century German history.

Life and career

Woods is Emeritus Professor in the Department of German studies at the University of Nottingham

, mottoeng ...

the "conservative dilemma". Nonetheless, they were generally opposed to traditional Wilhelmine

The Wilhelmine Period () comprises the period of German history between 1890 and 1918, embracing the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the German Empire from the resignation of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck until the end of World War I and Wilhelm' ...

Christian conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

, liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

and parliamentarian democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

as well as the cultural spirit of the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

and modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the "Age of Reas ...

. Plunged into what historian Fritz Stern

Fritz Richard Stern (February 2, 1926 – May 18, 2016) was a German-born American historian of German history, Jewish history and historiography. He was a University Professor and a provost at New York's Columbia University. His work focused ...

has named a deep "cultural despair", uprooted as they felt within the rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

and scientism

Scientism is the opinion that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to render truth about the world and reality.

While the term was defined originally to mean "methods and attitudes typical of or attributed to natural scientis ...

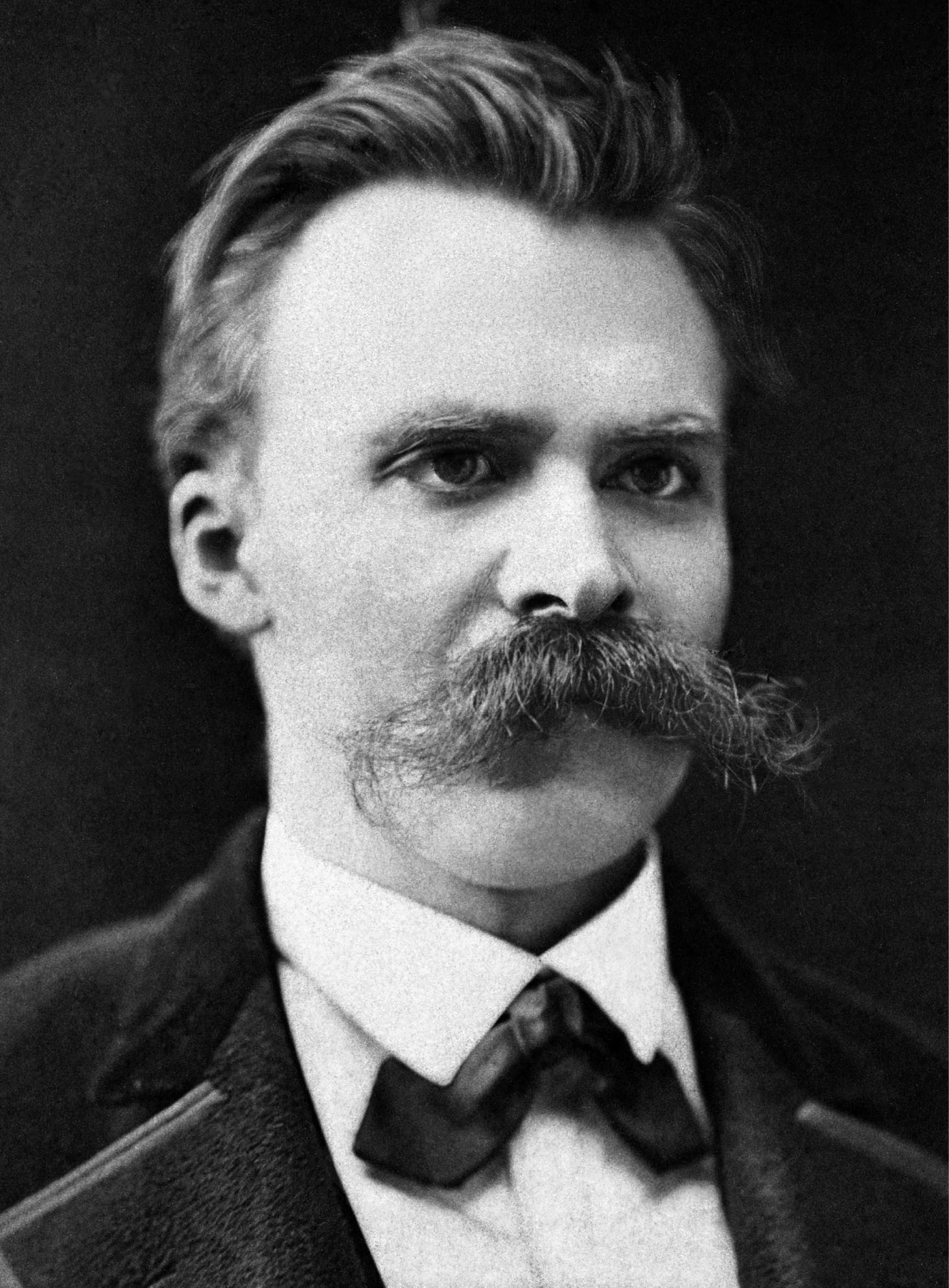

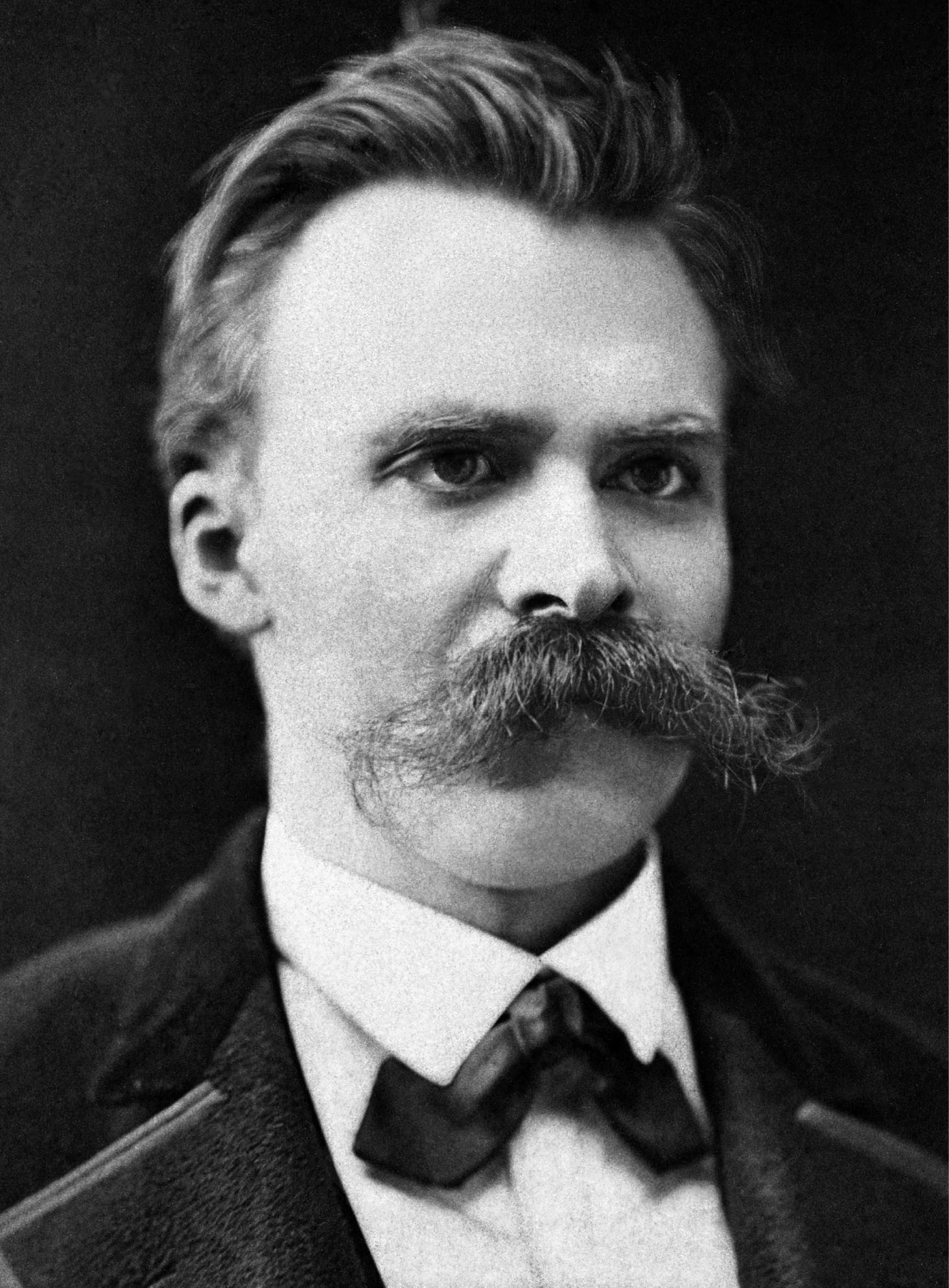

of the modern world, theorists of the Conservative Revolution drew inspiration from various elements of the 19th century, including Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

's contempt for Christian ethics

Christian ethics, also known as moral theology, is a multi-faceted ethical system: it is a virtue ethic which focuses on building moral character, and a deontological ethic which emphasizes duty. It also incorporates natural law ethics, whic ...

, democracy and egalitarianism; the anti-modern and anti-rationalist tendencies of German Romanticism; the vision of an organic and organized society cultivated by the ''Völkisch'' movement; the Prussian tradition of militaristic and authoritarian nationalism; and their own experience of comradeship and irrational violence on the front lines of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

The movement held an ambiguous relationship with Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

from the 1920s to the early 1930s which led scholars to describe the Conservative Revolution as a form of "German pre-fascism" or "non-Nazi fascism". Although they share common roots in 19th-century anti-Enlightenment

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from t ...

ideologies, the disparate movement cannot be easily confused with Nazism. Conservative Revolutionaries were not necessarily racialist as the movement cannot be reduced to its ''Völkisch'' component. If they participated in preparing the German society to the rule of the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

with their antidemocratic and organicist

Organicism is the philosophical position that states that the universe and its various parts (including human societies) ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism.Gilbert, S. F., and S. Sarkar. 2000. "Embra ...

theories, and did not really oppose their rise to power, the Conservative Revolution was brought to heel like the rest of the society when Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

seized power in 1933. Many of them eventually rejected the antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

or the totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

nature of the Nazis, with the notable exception of Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (; 11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and prominent member of the Nazi Party. Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. A conservative theorist, he is noted as ...

and a few others.

From the 1960–1970s onwards, the Conservative Revolution has largely influenced the European New Right

The European New Right (ENR) is a far-right movement which originated in France as the Nouvelle Droite in the late 1960s. Its proponents are involved in a global "anti-structural revolt" against modernity and post-modernity, largely in the form o ...

, in particular the French Nouvelle Droite

The Nouvelle Droite (; en, "New Right"), sometimes shortened to the initialism ND, is a far-right political movement which emerged in France during the late 1960s. The Nouvelle Droite is at the origin of the wider European New Right (ENR). Vario ...

and the German Neue Rechte

Neue Rechte (''New Right'') is the designation for a right-wing political movement in Germany. It was founded as an opposition to the New Left generation of the 1960s. Its intellectually oriented proponents distance themselves from Old Right Naz ...

, and through them the contemporary European Identitarian movement

The Identitarian movement or Identitarianism is a pan-European nationalist, far-right political ideology asserting the right of European ethnic groups and white peoples to Western culture and territories claimed to belong exclusively to them. ...

.Hentges, Gudrun; Kökgiran, Gürcan; Nottbohm, Kristina"Die Identitäre Bewegung Deutschland (IBD)–Bewegung oder virtuelles Phänomen"

''Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen'' 27, no. 3 (2014): 1–26.

Name and definition

If conservative essayists of the Weimar Republic likeArthur Moeller van den Bruck

Arthur Wilhelm Ernst Victor Moeller van den Bruck (23 April 1876 – 30 May 1925) was a German cultural historian, philosopher and writer best known for his controversial 1923 book ''Das Dritte Reich'' ("The Third Reich"), which promoted German ...

, Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Hugo Laurenz August Hofmann von Hofmannsthal (; 1 February 1874 – 15 July 1929) was an Austrian novelist, librettist, poet, dramatist, narrator, and essayist.

Early life

Hofmannsthal was born in Landstraße, Vienna, the son of an upper-cl ...

or Edgar Jung had already described their political project as a ''Konservative Revolution'' ("Conservative Revolution"), the name saw a revival after the 1949 doctoral thesis of Neue Rechte

Neue Rechte (''New Right'') is the designation for a right-wing political movement in Germany. It was founded as an opposition to the New Left generation of the 1960s. Its intellectually oriented proponents distance themselves from Old Right Naz ...

philosopher Armin Mohler

Armin Mohler (12 April 1920 – 4 July 2003) was a Swiss far-right political philosopher and journalist, known for his works on the Conservative Revolution. He is widely seen as the father of the Neue Rechte (''New Right''), the German branch of t ...

on the movement. Molher's post-war ideological reconstruction of the "Conservative Revolution" has been widely criticized by scholars, but the validity of a redefined concept of "neo-conservative" or "new nationalist" movement active during the Weimar period

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

(1918–1933), whose lifetime is sometimes extended to the years 1890s–1920s, and which differed in particular from the "old nationalism" of the 19th century, is now generally accepted in scholarship.

The name "Conservative Revolution" has appeared as a paradox, sometimes as a "semantic absurdity", for many modern historians, and some of them have suggested "neo-conservative" as a more easily justifiable label for the movement. Sociologist Stefan Breuer

Stefan Breuer (born 9 December 1948) is a German sociologist who specializes in the writings of Max Weber and the German political right between 1871 and 1945.

Life and career

Born in 1948, Breuer studied political science, history and philoso ...

wrote that he would have preferred the substitute "new nationalism" to name a charismatic and holistic

Holism () is the idea that various systems (e.g. physical, biological, social) should be viewed as wholes, not merely as a collection of parts. The term "holism" was coined by Jan Smuts in his 1926 book '' Holism and Evolution''."holism, n." OED On ...

cultural movement that differed from the "old nationalism" of the previous century, whose essential role was limited to the preservation of the German institutions and their influence in the world. Despite the apparent contradiction, however, the association of the terms "Conservative" and "Revolution" is justified in Moeller van den Bruck's writings by his definition of the movement as a will to preserve eternal values while favouring at the same time the redesign of ideal and institutional forms in response to the "insecurities of the modern world".

Historian Louis Dupeux regarded the movement as an intellectual project with its own consistent logic, namely the striving for an ''Intellektueller Macht'' ("intellectual power") in order to promote modern conservative and revolutionary ideas directed against liberalism, egalitarianism, and traditional conservatism. This change of attitude (''Haltung'') is labeled a ''Bejahung'' ("affirmation") by Dupeux: Conservative Revolutionaries said "yes" to their time as long as they could find the ways to facilitate the resurgence of anti-liberal and "eternal values" within modern societies. Dupeux conceded at the same time that the Conservative Revolution was rather a counter-cultural movement than a real philosophical proposition, relying more on "feeling, images and myths" than on scientific analysis and concepts. He also admitted the necessity to distinguish several leanings, sometimes with contradictory views, within its diverse ideological spectrum. Louis Dupeux, "Die Intellektuellen der konservativen Revolution und ihr Einfluß zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik", in Walter Schmitz et al., ''Völkische Bewegung – Konservative Revolution – Nationalsozialismus. Aspekte einer politisierten Kultur'', Dresden, Thelem, 2005, p. 3.

Political scientist Tamir Bar-On has summarized the Conservative Revolution as a combination of "German ultra-nationalism, defence of the organic folk community, technological modernity, and socialist revisionism, which perceived the worker and soldier as models for a reborn authoritarian state superseding the egalitarian "decadence" of liberalism, socialism, and traditional conservatism."

Origin and development

The Conservative Revolution is encompassed in a larger and older counter-movement to theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

of 1789, influenced by the anti-modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the "Age of Reas ...

and anti-rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

of early 19th-century romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, in the context of a German, especially Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n, "tradition of militaristic, authoritarian nationalism which rejected liberalism, socialism, democracy and internationalism." Historian Fritz Stern

Fritz Richard Stern (February 2, 1926 – May 18, 2016) was a German-born American historian of German history, Jewish history and historiography. He was a University Professor and a provost at New York's Columbia University. His work focused ...

described the movement as disoriented intellectuals plunged into a profound "cultural despair": they felt alienated and uprooted within a world dominated by what they saw as "bourgeois rationalism and science". Their hatred of modernity, Stern follows, led them to the naive confidence that all these modern evils could be fought and resolved by a "Conservative Revolution".

Although terms such as ''Konservative Kraft'' ("conservative power") and ''schöpferische Restauration'' ("creative restoration") began to spread across German-speaking Europe from the 1900s to the 1920s, the ''Konservative Revolution'' ("Conservative Revolution") became an established concept in the

Although terms such as ''Konservative Kraft'' ("conservative power") and ''schöpferische Restauration'' ("creative restoration") began to spread across German-speaking Europe from the 1900s to the 1920s, the ''Konservative Revolution'' ("Conservative Revolution") became an established concept in the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

(1918–1933) through the writings of essayists like Arthur Moeller van den Bruck

Arthur Wilhelm Ernst Victor Moeller van den Bruck (23 April 1876 – 30 May 1925) was a German cultural historian, philosopher and writer best known for his controversial 1923 book ''Das Dritte Reich'' ("The Third Reich"), which promoted German ...

, Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Hugo Laurenz August Hofmann von Hofmannsthal (; 1 February 1874 – 15 July 1929) was an Austrian novelist, librettist, poet, dramatist, narrator, and essayist.

Early life

Hofmannsthal was born in Landstraße, Vienna, the son of an upper-cl ...

, Hermann Rauschning

Hermann Adolf Reinhold Rauschning (7 August 1887 – February 8, 1982) was a German politician and author, adherent of the Conservative Revolution movement who briefly joined the Nazi movement before breaking with it. He was the President of the ...

, Edgar Jung and Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best k ...

.

The creation of the ''Alldeutscher Verband

The Pan-German League (german: Alldeutscher Verband) was a Pan-German nationalist organization which was officially founded in 1891, a year after the Zanzibar Treaty was signed.

Primarily dedicated to the German Question of the time, it held pos ...

'' ("Pan-German League") by Alfred Hugenberg

Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg (19 June 1865 – 12 March 1951) was an influential German businessman and politician. An important figure in nationalist politics in Germany for the first few decades of the twentieth century, Hugenbe ...

in 1891 and the '' Jugendbewegung'' ("youth movement") in 1896 are cited as conducive to the emergence of the Conservative Revolution in the following decades. Moeller van den Bruck was the dominant figure of the movement until his suicide on 30 May 1925. His ideas were initially spread through the ''Juniklub'' he had founded on 28 June 1919, on the day of the signing of Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

.

Conservative Revolutionaries frequently referred to German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

as their mentor, and as the main intellectual influence on their movement. Despite Nietzsche's philosophy being often misinterpreted, or wrongly appropriated by thinkers of the Conservative Revolution, they retained his contempt for Christian ethics, democracy, modernity and egalitarianism as the cornerstone of their ideology. Historian Roger Woods

Roger Woods (born 1949) is a British contemporary historian who specialises on 20th-century German history.

Life and career

Woods is Emeritus Professor in the Department of German studies at the University of Nottingham

, mottoeng ...

writes that Conservative Revolutionaries "constructed", in response to the war and the unstable Weimar period

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

, a Nietzsche "who advocated a self-justifying activism, unbridled self-assertion, war over peace, and the elevation of instinct over reason."

Many of the intellectuals involved in the movement were born in the last decades of the nineteenth century and experienced WWI as a formative event (''Kriegserlebnis'', "war experience") for the foundation of their political beliefs. The life on the front line, with its violence and irrationality, caused most of them to search ''a posteriori'' for a meaning to what they had to endure during the conflict. Ernst Jünger

Ernst Jünger (; 29 March 1895 – 17 February 1998) was a German author, highly decorated soldier, philosopher, and entomologist who became publicly known for his World War I memoir '' Storm of Steel''.

The son of a successful businessman and ...

is the major figure of that branch of the Conservative Revolution which wanted to uphold military structures and values in peacetime society, and saw in the community of front line comradeship (''Frontgemeinschaft'') the true nature of German socialism.

Main thinkers

According toArmin Mohler

Armin Mohler (12 April 1920 – 4 July 2003) was a Swiss far-right political philosopher and journalist, known for his works on the Conservative Revolution. He is widely seen as the father of the Neue Rechte (''New Right''), the German branch of t ...

Armin Mohler

Armin Mohler (12 April 1920 – 4 July 2003) was a Swiss far-right political philosopher and journalist, known for his works on the Conservative Revolution. He is widely seen as the father of the Neue Rechte (''New Right''), the German branch of t ...

, Karlheinz Weißmannn: ''Die konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932 – Ein Handbuch.'' 6. überarbeitete Auflage. Graz 2005, p. 379f (Spengler, Mann, Schmitt); p. 467ff (Jung, Spann); p. 472 (Hans Freyer); p. 479 (Niemöller); p. 62 (Lensch-Cunow-Henisch-Gruppe); p. 372 (Hofmannsthal, George); p. 470 (Winnig); p. 519ff (Niekisch); p. 110ff, 415 (Quabbe . Aufl. 1999; p. 465 (Stapel). and other sources, prominent members of the Conservative Revolution included:

Ideology

Despite a broad range of political positions that historian Roger Woods has labelled the "conservative dilemma", the German Conservative Revolution can be defined by its disapproval of: * the traditional conservative values of theGerman Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

(1871–1918), including the egalitarian ethics of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

; and a rejection of the project of a restoration of the defunct Wilhelmine

The Wilhelmine Period () comprises the period of German history between 1890 and 1918, embracing the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the German Empire from the resignation of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck until the end of World War I and Wilhelm' ...

empire within its historical political and cultural structures,

* the political regime and commercialist culture of the Weimar Republic; and the parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

and democracy in general, because the national community (''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'') shall "transcend the conventional divisions of left and right",

* the class analysis

Class analysis is research in sociology, politics and economics from the point of view of the stratification of the society into dynamic classes. It implies that there is no universal or uniform social outlook, rather that there are fundamental c ...

of socialism; with the defence of an anti-Marxist "socialist revisionism"; labelled by Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best k ...

the "socialism of the blood", it drew inspiration from the front line comradeship of World War I.

New nationalism and morality

Conservative Revolutionaries argued that their nationalism was fundamentally different from the precedent forms of German nationalism or conservatism, condemning the

Conservative Revolutionaries argued that their nationalism was fundamentally different from the precedent forms of German nationalism or conservatism, condemning the reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the '' status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abs ...

outlook of traditional Wilhelmine

The Wilhelmine Period () comprises the period of German history between 1890 and 1918, embracing the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the German Empire from the resignation of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck until the end of World War I and Wilhelm' ...

conservatives and their failure to fully understand the emerging concepts of the modern world, such as technology, the city and the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

.

Moeller van den Bruck defined the Conservative Revolution as the will to conserve a set of values seen as inseparable from a ''Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

'' ("people, ethnic group"). If these eternal values can hold on through the fluctuations of the ages, they are also able to survive in the world due to the same movements and changes in their history. Distant from the reactionary who, in Moeller van den Bruck's eyes, does not create (and from the pure revolutionary who does nothing but destroys everything), the Conservative Revolutionary sought to give a form to phenomena in an eternal space, a shape that could guarantee their survival among the few things that cannot be lost:

Edgar Jung indeed dismissed the idea that true conservatives wanted to "stop the wheel of history". The chivalric

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed ...

way of life they were seeking to achieve was, according to Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best k ...

, not governed by any moral code, but rather by "a noble, self-evident morality, based on that natural sense of tact which comes from good breeding". This morality was not the product of a conscious reflection, but rather "something innate which one senses and which has its own organic logic."Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best k ...

'', Untergang des Abendlandes'' ("The Decline of the West

''The Decline of the West'' (german: Der Untergang des Abendlandes; more literally, ''The Downfall of the Occident''), is a two-volume work by Oswald Spengler. The first volume, subtitled ''Form and Actuality'', was published in the summer of 19 ...

"), vol 2, 1923. pp. 891, 982 If the values of morality were deemed to be instinctive and eternal, they were logically seen as embodied in rural life. The latter became challenged, Spengler believed, by the rise of the artificial world of the city, where theories and observations were needed to understand life itself, either coming from liberal democrats or scientific socialists. What Conservative Revolutionaries were aiming to achieve was the restoration, within the modern world, of what they saw as natural laws and values:

Influenced by Nietzsche, most of them were opposed to the Christian ethics of solidarity and equality. Although many Conservative Revolutionaries described themselves as Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

or Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, they saw Christian ethical premise as structurally indenturing the strong into mandatory, rather than optional, service to the weak. On a geopolitical scale, theorists of the movement adopted a vision of the world (''Weltanschauung'') where nations would abandon moral standards in their relationship to each others, only guided by their natural self-interest.

'' Völkischen'' were involved in a racialist

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ex ...

and occultist

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

movement dating back to the middle of the 19th century and had an influence on the Conservative Revolution. Their priority was the fight against Christianity and the return to a (reconstructed) Germanic pagan faith, or the "Germanization" of Christianity to purge it from foreign (Semitic) influence.

''Volksgemeinschaft'' and dictatorship

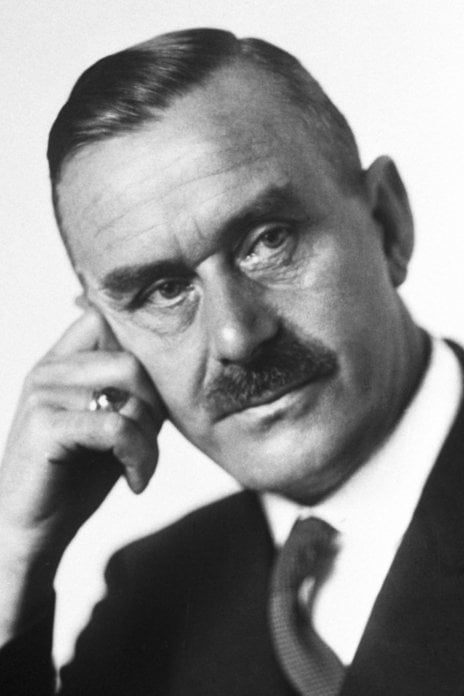

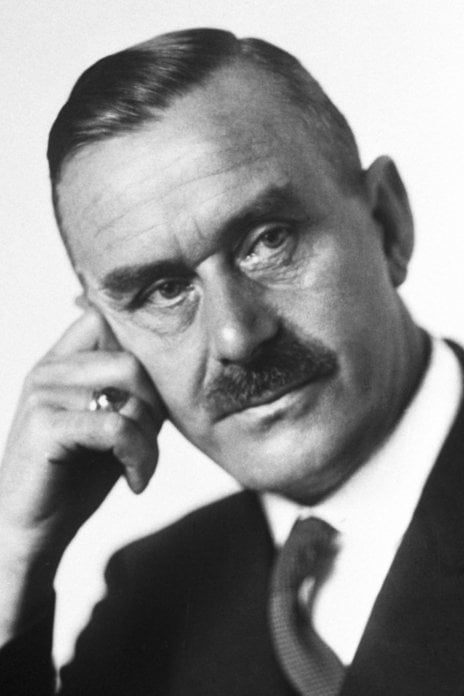

Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

believed that if German military resistance to the West during World War I was stronger than its spiritual resistance, it was primarily because the ''ethos

Ethos ( or ) is a Greek word meaning "character" that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology; and the balance between caution, and passion. The Greeks also used this word to refer to ...

'' ("character") of the German ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'' ("national community") cannot quickly express itself in words, and as a result is not able to counter effectively the solid rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

of the West. Since German culture was "of the soul, something which could not be grasped by the intellect",Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

, ''Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen, Das essayistische Werk,'' 8 vols, ed. by Hans Bürgin (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 1968), 1, p. 22-29 the authoritarian state was the natural order desired by the German people. Politics, Mann argued, was inevitably a commitment to democracy and therefore alien to the German spirit:

Mann was accused by the right of watering down his undemocratic views in 1922 after he removed some paragraphs from the republication of ''Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen'' ("Reflections of an Unpolitical Man"), originally released in 1918. If scholars have debated whether these formulations should be considered artistic and idealistic, or rather a serious attempt to draw a political analysis of that period, young Mann's writings had been influential on many Conservative Revolutionaries. In a speech pronounced in 1922 (''Von Deutscher Republik''), Mann publicly became a staunch defender of the Weimar Republic and attacked many of the figures associated with the Conservative Revolution such as Oswald Spengler, whom he depicted as intellectually dishonest and irresponsibly immoral. In 1933, he described National Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Naz ...

as the ''politische Wirklichkeit jener konservativen Revolution'', that is to say the "political reality of that Conservative Revolution".

In 1921, Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (; 11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and prominent member of the Nazi Party. Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. A conservative theorist, he is noted as ...

published his essay ''Die Diktatur'' ("The Dictatorship"), in which he studied the foundations of the recently established Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

. Comparing what he saw as the effective and ineffective elements of the new constitution, he highlighted the office of the '' Reichspräsident'' as a valuable position, essentially due to the power granted to the president to declare an ''Ausnahmezustand'' ("state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

"), which Schmitt implicitly praised as dictatorial:Deutsche Juristen-Zeitung, 38, 1934; trans. as "The Führer Protects Justice" in Detlev Vagts, ''Carl Schmitt's Ultimate Emergency: The Night of the Long Knives'' (2012) 87(2) ''The Germanic Review'' 203.

Schmitt clarified in ''Politische Theologie'' (1922) that there cannot be any functioning legal order without a sovereign authority. He defined sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

as the ''possibility'', or the power, to ''decide'' on the triggering of a "state of emergency", in other words a state of ''exception'' regarding the law. According to him, every government should include within its constitution that dictatorial possibility to allow, when necessary, for faster and more effective decisions than going through parliamentary discussion and compromise. Referring to Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, he later used the following formulation to justify the legitimacy of the Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

: ''Der Führer schützt das Recht'' ("The leader defends the law").

Front-line socialism

Conservative Revolutionaries asserted that they were not guided by the "sterile resentment of the class struggle". Many of them invoked the community of front line comradeship (''Frontgemeinschaft'') of World War I as the model for the national community (''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community", Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'') to follow in peaceful times, hoping in that project to transcend the established political categories of right and left. For that purpose, they tried to remove the concept of revolution from November 1918 in order to attach it to August 1914. Conservative Revolutionaries indeed painted the November Revolution, which led to the foundation of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, as a betrayal of the true revolution and, at best, hunger protests by the mob.

The common agreement with socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the econ ...

was the abolition of the excesses of capitalism. Jung claimed that, while the economy should remain in private hands, the "greed of capital" should at the same time be controlled, and that a community based on shared interests had to be set up between workers and employers. Another source of aversion for capitalism was rooted in the profits made from the war and inflation, and a last concern can be found in the fact that most of Conservative Revolutionaries belonged to the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

, in which they felt crushed at the centre of an economic struggle between the ruling capitalists and the potentially dangerous masses.

If they dismissed communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

as mere idealism, many thinkers showed their dependence on Marxist terminology in their writings. Jung emphasized the "historical inevitability" of conservatism taking over from the liberal era, in a mirror-image of the historical materialism

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

developed by Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

. If Spengler also wrote about the decline of the West

''The Decline of the West'' (german: Der Untergang des Abendlandes; more literally, ''The Downfall of the Occident''), is a two-volume work by Oswald Spengler. The first volume, subtitled ''Form and Actuality'', was published in the summer of 191 ...

as an ineluctable phenomenon, his intention was to provide modern readers with a "new socialism" that would enable them to realize the meaninglessness of life, contrasting with Marx's idea of the coming of paradise on earth. Above all, the Conservative Revolution drew influences from vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

and irrationalism

Irrationalism is a philosophical movement that emerged in the early 19th century, emphasizing the non-rational dimension of human life. As they reject logic, irrationalists argue that instinct and feelings are superior to the reason in the researc ...

, rather than from materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

. Spengler argued that the materialist vision of Marx was based on nineteenth-century science, while the twentieth century would be the age of psychology

Psychology is the science, scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immens ...

:

Along with Karl Otto Paetel

Karl Otto Paetel (23 November 1906 – 4 May 1975) was a German political journalist. During the 1920s, he was a prominent exponent of National Bolshevism. During the 1930s, he became a member of anti-Nazi German resistance.

Biography

Paetel wa ...

and Heinrich Laufenberg

Heinrich Laufenberg (19 January 1872 – 3 February 1932) was a leading German communist and one of the first to develop the idea of National Bolshevism. Laufenberg was a history academic by profession and was also known by the pseudonym Karl Erle ...

, Ernst Niekisch

Ernst Niekisch (23 May 1889 – 23 May 1967) was a German writer and politician. Initially a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he later became a prominent exponent of National Bolshevism.

Early life

Born in Trebnitz (Silesia), and b ...

was one of the main advocates of National Bolshevism

National Bolshevism (russian: национал-большевизм, natsional-bol'shevizm, german: Nationalbolschewismus), whose supporters are known as National Bolsheviks (russian: национал-большевики, natsional-bol'sheviki ...

, a minor branch of the Conservative Revolution, described as the "left-wing-people of the right" (''Linke Leute von rechts'').' They defended an ultra-nationalist form of socialism that took its roots in both '' Völkisch'' extremism and nihilistic

Nihilism (; ) is a philosophy, or family of views within philosophy, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning. The term was popularized by Iva ...

'' Kulturpessimismus'', rejecting any Western influence on German society: liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

and democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

, capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

and the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

, Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

and humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

. Niekisch and National Bolsheviks were even ready to build a temporary alliance with German communists

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in order to annihilate the capitalist West.

Currents

In his PhD thesis directed byKarl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (, ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. After being trained in and practicing psychiatry, Jaspe ...

, Armin Mohler

Armin Mohler (12 April 1920 – 4 July 2003) was a Swiss far-right political philosopher and journalist, known for his works on the Conservative Revolution. He is widely seen as the father of the Neue Rechte (''New Right''), the German branch of t ...

distinguished five currents inside the nebula of the Conservative Revolution: the ''Jungkonservativen'' ("young conservatives"), the ''Nationalrevolutionäre'' ("national revolutionaries"), the '' Völkischen'' (from the "folkish movement"), the ''Bündischen'' ("leaguists") and the '' Landvolksbewegung'' ("rural people's movement"). According to Mohler, the last two groups were less theory- and more action-oriented, the ''Landvolks'' movement offering concrete resistance in the form of demonstrations and tax boycotts.

French historian Louis Dupeux saw five lines of divisions that can be drawn inside the Conservative Revolutionaries: the small farmers were different from the cultural pessimists and the "pseudo-moderns", who belonged for the most part to the middle class; while the proponent of an "organic" society diverged from those of an "organized" society. A third division split the supporters of deep and lengthy political and cultural transformations from those who endorsed a quick and erupting social revolution, as far as challenging economic freedom and private property. The fourth rift resided in the question of the '' Drang nach Osten'' ("drive to the East") and the attitude to adopt towards Bolshevik Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, escorted by a debate on the place of Germany between a so-called "senile" West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

and "young and barbaric" Orient

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of '' Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

; the last division being a deep opposition between the ''Völkischen'' and the pre-fascist thinkers.

In 1995, historian Rolf Peter Sieferle described what he labelled five "complexes" in the Conservative Revolution: the "völkischen", the "national socialists", the "revolutionary nationalists" as such, the "vital-activists" (''aktivistisch-vitalen''), and, a minority in the movement, the "biological naturalists".

Building on the previous studies conducted by Mohler and Dupeux, French political scientist Stéphane François summarized the three main currents within the Conservative Revolution, this broad division being the most widely shared among analysts of the movement:

* the "young conservatives" (''Jungkonservativen'');

* the "national revolutionaries" (''Nationalrevolutionäre'');

* the ''Völkischen'' (from the ''Völkisch'' movement).

Young conservatives

"Young conservatives" were deeply influenced by 19th-century intellectual and aesthetic movements such as German romanticism and '' Kulturpessimismus'' ("cultural pessimism"). Contrary to traditional

"Young conservatives" were deeply influenced by 19th-century intellectual and aesthetic movements such as German romanticism and '' Kulturpessimismus'' ("cultural pessimism"). Contrary to traditional Wilhelmine

The Wilhelmine Period () comprises the period of German history between 1890 and 1918, embracing the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the German Empire from the resignation of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck until the end of World War I and Wilhelm' ...

conservatives, ''Jungkonservativen'' aimed at assisting the re-emergence of "persistent and fundamental structures"—authority, the state, the community, the nation, the people—while "espousing their times" in the very same movement.

Moeller van den Bruck tried to overcome the ''Kulturpessimismus'' dilemma by fighting decadency to build a new political order over it. In 1923, he published the influential book '' Das Dritte Reich'' ("The Third Reich")'','' in which he went further from theoretical analysis to introduce a practical revolutionary programme as a remedy to the political situation: a "Third Reich" that would unite all classes under an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

rule based on a combination of the nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

of the right and the socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

of the left.

Rejecting both the nation-state narrowed to one unified people and the imperialistic structure based on different ethnic groups, the goal of ''Jungkonservativen'' was to fulfil the ''Volksmission'' ("mission of the Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

") through the edification of a new Reich, i.e. "the organization of all the peoples in a supra-state, dominated by a superior principle, under the supreme responsibility of only one people" in the words of Armin Mohler. As summarized by Edgar Jung in 1933:

Although Moeller van der Bruck killed himself in despair in May 1925, his ideas continued to influence his contemporaries. Among them was Edgar Jung, who advocated the creation of a corporatist

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

organic state, free from class struggle and parliamentary democracy, which would make way for a return to the spirit of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

with a new Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

federating central Europe. The theme of a return to medieval values and aesthetics among "young conservatives" was inherited from a Romantic fascination for that period, which they believed to be simpler and more integrated than the modern world. Oswald Spengler

Oswald Arnold Gottfried Spengler (; 29 May 1880 – 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher of history whose interests included mathematics, science, and art, as well as their relation to his organic theory of history. He is best k ...

praised medieval chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

as the philosophical and moral attitude to adopt against a modern decadent spirit. Jung perceived this return as a gradual and lengthy transformation, similar to the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

of the 16th century, rather than a sudden revolutionary eruption like the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

.

National revolutionaries

Other Conservative Revolutionaries rather drew influence from their life at the front line (, "war experience") during the

Other Conservative Revolutionaries rather drew influence from their life at the front line (, "war experience") during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Far from the concern of the "young conservatives", Ernst Jünger

Ernst Jünger (; 29 March 1895 – 17 February 1998) was a German author, highly decorated soldier, philosopher, and entomologist who became publicly known for his World War I memoir '' Storm of Steel''.

The son of a successful businessman and ...

and the other "national revolutionaries" advocated total acceptance of modern technique and endorsed the use of any modern phenomena that could help them overcome modernity—such as propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

or mass organization

A mass movement denotes a political party or movement which is supported by large segments of a population. Political movements that typically advocate the creation of a mass movement include the ideologies of communism, fascism, and liberalism. Bo ...

s—and eventually achieve a new political order. The latter would have been based on life itself rather than the intellect, founded on organic, naturally structured and hierarchical communities, and led by a new aristocracy of merit and action. Historian Jeffrey Herf used the term "reactionary modernism

Reactionary modernism is a term first coined by Jeffrey Herf in the 1980s, to describe the mixture of "great enthusiasm for modern technology with a rejection of the Enlightenment and the values and institutions of liberal democracy" which was c ...

" to describe that "great enthusiasm for modern technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scien ...

with a rejection of the Enlightenment and the values and institutions of liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

":

Jünger supported the emergence of a young intellectual elite that would spring out from the trenches of WWI, ready to oppose bourgeois capitalism and to embody a new nationalist revolutionary spirit. In the 1920s, he wrote more than 130 articles in various nationalist magazines, mostly in or, less frequently, in , the National-Bolshevik publication of Ernst Niekisch

Ernst Niekisch (23 May 1889 – 23 May 1967) was a German writer and politician. Initially a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he later became a prominent exponent of National Bolshevism.

Early life

Born in Trebnitz (Silesia), and b ...

. However, as Dupeux pointed out, Jünger wanted to use nationalism as an "explosive" and not as an "absolute", to eventually let the new order arise by itself. The association of Jünger to the Conservative Revolutionaries is still a matter of debate among scholars.

The entry of Germany in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

in 1926 participated in radicalizing the revolutionary wing of the movement during the late 1920s. The event was interpreted as a "sign of a Western orientation" in a country Conservative Revolutionaries had interpreted as the future ("Empire of Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

").

''Völkischen''

The adjective '' völkisch'' derives from the German concept of ''Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

'' (cognate with English ''folk''), which has overtones of "nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by th ...

", " race" and "tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confl ...

". The ''Völkisch'' movement emerged in the mid-19th century, influenced by German Romanticism. Erected on the concept of ''Blut und Boden'' (" blood and soil"), it was a racialist

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ex ...

, populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

, agrarian, romantic nationalist and, from the 1900s, an antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

movement. According to Armin Mohler

Armin Mohler (12 April 1920 – 4 July 2003) was a Swiss far-right political philosopher and journalist, known for his works on the Conservative Revolution. He is widely seen as the father of the Neue Rechte (''New Right''), the German branch of t ...

, the ''Völkischen'' aimed at opposing the "process of desegregation" that was threatening the ''Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

'' by providing him means to generate a consciousness of itself.Armin Mohler

Armin Mohler (12 April 1920 – 4 July 2003) was a Swiss far-right political philosopher and journalist, known for his works on the Conservative Revolution. He is widely seen as the father of the Neue Rechte (''New Right''), the German branch of t ...

: ''Die konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932.'' pp. 81–83, 166–172.

Influenced by authors like Arthur de Gobineau

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau (; 14 July 1816 – 13 October 1882) was a French aristocrat who is best known for helping to legitimise racism by the use of scientific racist theory and "racial demography", and for developing the theory of the Aryan ...

(1816–1882), Georges Vacher de Lapouge (1854–1936), Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (; 9 September 1855 – 9 January 1927) was a British-German philosopher who wrote works about political philosophy and natural science. His writing promoted German ethnonationalism, antisemitism, and scientific ...

(1855–1927) or Ludwig Woltmann

Ludwig Woltmann (born 18 February 1871 in Solingen; died 30 January 1907) was a German anthropologist, zoologist and neo-Kantian.

He studied medicine and philosophy, and obtained doctorates in the two fields from the University of Freiburg in 18 ...

(1871–1907), the ''Völkischen'' had conceptualised a racialist and hierarchical definition of the peoples of the world where Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

s (or Germans) were set at the summit of the " white race". But while they used terms like ''Nordische Rasse'' ("Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming tha ...

") and ''Germanentum'' ("Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

"), their concept of ''Volk'' could also be more flexible and understood as a ''Gemeinsame Sprache'' ("common language"), or an ''Ausdruck einer Landschaftsseele'' ("expression of a landscape's soul") in the words of geographer Ewald Banse. The ''Völkischen'' indeed idealized the myth of an "original nation", that still could be found at their times in the rural regions of Germany, a form of "primitive democracy freely subjected to their natural elites." The notion of "people" (''Volk'') then turned into the idea of a birth-giving and eternal entity among the ''Völkischen''—in the same way as they would have written on "the Nature"—rather than a sociological category.

The political agitation and uncertainty that followed WWI nourished a fertile background for the renewed success of various ''Völkisch'' sects that were abundant in Berlin at the time. Although the ''Völkischen'' became significant by the number of groups during the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

, they were not so by the number of adherents. Some ''Völkischen'' tried to revive what they believed to be a true German faith ( ''Deutschglaube''), by resurrecting the cult of ancient Germanic gods. Various occult movements such as Ariosophy were connected to ''Völkisch'' theories, and artistic circles were largely present among the ''Völkischen'', like the painters Ludwig Fahrenkrog

Ludwig Fahrenkrog (20 October 1867 – 27 October 1952) was a German painter, illustrator, sculptor and writer. He was born in Rendsburg, Prussia, in 1867. He started his career as an artist in his youth, and attended the Berlin Royal Art A ...

(1867–1952) and Fidus

Fidus was the pseudonym used by German illustrator, painter and publisher Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener (October 8, 1868 – February 23, 1948). He was a symbolist artist, whose work directly influenced the psychedelic style of graphic ...

(1868–1948). By May 1924, Wilhelm Stapel

Otto Friedrich Wilhelm Stapel (27 October 1882 – 1 June 1954), was a German Protestant and nationalist essayist. He was the editor of the influential antisemitic monthly magazine ''Deutsches Volkstum'' from 1919 until its shutdown by the Nazis ...

perceived the movement as capable of embracing and reconciling the whole nation: in his view, ''Vökischen'' had an idea to spread instead of a party programme and were led by heroes, not by "calculating politicians".Wilhelm Stapel

Otto Friedrich Wilhelm Stapel (27 October 1882 – 1 June 1954), was a German Protestant and nationalist essayist. He was the editor of the influential antisemitic monthly magazine ''Deutsches Volkstum'' from 1919 until its shutdown by the Nazis ...

, "Das Elementare in der volkischen Bewegung", ''Deutsches Volkstum,'' 5 May 1924, pp. 213–15.

Mohler listed the following figures as adherents to the ''Völkisch'' movement: Theodor Fritsch, Otto Ammon, Willibald Hentschel Willibald Hentschel (7 November 1858 in Łódź – 2 February 1947 in Berg, Upper Bavaria) was a German agrarian and volkisch writer and political activist. He sought to renew the Aryan race through a variety of schemes, including selective breed ...

, Guido von List

Guido Karl Anton List, better known as Guido von List (5 October 1848 – 17 May 1919), was an Austrian occultist, journalist, playwright, and novelist. He expounded a modern Pagan new religious movement known as Wotanism, which he claimed was ...

, Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. ...

, Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, Herman Wirth

Herman may refer to:

People

* Herman (name), list of people with this name

* Saint Herman (disambiguation)

* Peter Noone (born 1947), known by the mononym Herman

Places in the United States

* Herman, Arkansas

* Herman, Michigan

* Herman, Min ...

, and Ernst Graf zu Reventlow.

Relationship to Nazism

Despite a significant intellectual legacy in common, the disparate movement cannot be easily confused withNazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

. Their anti-democratic and militaristic thoughts certainly participated in making the idea of an authoritarian regime acceptable to the semi-educated middle-class, and even to the educated youth, but Conservative Revolutionary writings did not have a decisive influence on National Socialist ideology. Historian Helga Grebing

Helga Grebing (1930–2017) was a German historian and university professor ( Göttingen, Bochum). A focus of her work is on social history and, more specifically, on the history of the labour movement.

Life

Provenance and early years

Grebi ...

indeed reminds that "the question of the susceptibility to and preparation for National Socialism is not the same as the question of the roots and ideological precursors of National Socialism". This ambiguous relationship led scholars to characterize the movement as a form of "German pre-fascism" or "non-Nazi fascism".

During the rise of power of the Nazi party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

in the 1920s and until the early 1930s, some thinkers seem to have shown, as historian Roger Woods

Roger Woods (born 1949) is a British contemporary historian who specialises on 20th-century German history.

Life and career

Woods is Emeritus Professor in the Department of German studies at the University of Nottingham

, mottoeng ...

writes, "a blindness towards the true nature of the Nazis", while their unresolved political dilemma and failure to define the content of the new regime Germany should adopt led to an absence of resistance to the eventual Nazi seizure of power. According to historian Fritz Stern

Fritz Richard Stern (February 2, 1926 – May 18, 2016) was a German-born American historian of German history, Jewish history and historiography. He was a University Professor and a provost at New York's Columbia University. His work focused ...

, "despite some misgivings about Hitler's demagogy, many conservative revolutionaries saw in the ''Führer'' the sole possibility of achieving their goal. In the sequel, Hitler's triumph shattered the illusions of most of Moeller's followers, and the twelve years of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

witnessed the separation of conservative revolution and national socialism again".

After a few months of adulation following their decisive electoral victory, the Nazis disavowed Moeller van den Bruck and denied that he had been a forerunner of National Socialism: his "unrealistic ideology", as they said in 1939, had "nothing to do with the actual historical developments or with sober ''Realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' (; ) refers to enacting or engaging in diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly binding itself to explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical ...