Conservative Jews on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a

The Conservative mainstay was the adoption of the historical-critical method in understanding Judaism and setting its future course. In accepting an evolutionary approach to the religion, as something that developed over time and absorbed considerable external influences, the movement distinguished between the original meaning implied in traditional sources and the manner they were grasped by successive generations, rejecting belief in an unbroken chain of interpretation from God's original Revelation, immune to any major extraneous effects. This evolutionary perception of religion, while relatively moderate in comparison with more radical modernizers—the scholarship of the Positive-Historical school, for example, sought to demonstrate the continuity and cohesiveness of Judaism over the years—still challenged Conservative leaders.

They regarded tradition and received mores with reverence, especially the continued adherence to the mechanism of Religious Law (''

The Conservative mainstay was the adoption of the historical-critical method in understanding Judaism and setting its future course. In accepting an evolutionary approach to the religion, as something that developed over time and absorbed considerable external influences, the movement distinguished between the original meaning implied in traditional sources and the manner they were grasped by successive generations, rejecting belief in an unbroken chain of interpretation from God's original Revelation, immune to any major extraneous effects. This evolutionary perception of religion, while relatively moderate in comparison with more radical modernizers—the scholarship of the Positive-Historical school, for example, sought to demonstrate the continuity and cohesiveness of Judaism over the years—still challenged Conservative leaders.

They regarded tradition and received mores with reverence, especially the continued adherence to the mechanism of Religious Law (''

The Conservative treatment of ''Halakha'' is defined by several features, though the entire range of its ''Halakhic'' discourse cannot be sharply distinguished from either the traditional or Orthodox one. Rabbi

The Conservative treatment of ''Halakha'' is defined by several features, though the entire range of its ''Halakhic'' discourse cannot be sharply distinguished from either the traditional or Orthodox one. Rabbi

The RA and CJLS reached many decisions through the years, shaping a distinctive profile for Conservative practice and worship. In the 1940s, when the public demanded mixed seating of both sexes in synagogue, some rabbis argued there was no precedent but obliged on the ground of dire need ( Eth la'asot); others noted that archaeological research showed no partitions in ancient synagogues. Mixed seating became commonplace in almost all congregations. In 1950, it was ruled that using electricity (that is, closure of an electrical circuit) did not constitute kindling a fire unto itself, not even in

The RA and CJLS reached many decisions through the years, shaping a distinctive profile for Conservative practice and worship. In the 1940s, when the public demanded mixed seating of both sexes in synagogue, some rabbis argued there was no precedent but obliged on the ground of dire need ( Eth la'asot); others noted that archaeological research showed no partitions in ancient synagogues. Mixed seating became commonplace in almost all congregations. In 1950, it was ruled that using electricity (that is, closure of an electrical circuit) did not constitute kindling a fire unto itself, not even in

In New York, the JTS serves as the movement's original seminary and legacy institution, along with the

In New York, the JTS serves as the movement's original seminary and legacy institution, along with the

Will Conservative Day Schools Survive?

June 5, 2008 During the first decade of the 21st century, a number of schools that were part of the Schechter network transformed themselves into non-affiliated community day schools. The USCJ also maintains the Camp Ramah system, where children and adolescents spend summers in an observant environment.

The rise of modern, centralized states in Europe by the early 19th century heralded the end of Jewish judicial autonomy and social seclusion. Their communal corporate rights were abolished, and the process of

The rise of modern, centralized states in Europe by the early 19th century heralded the end of Jewish judicial autonomy and social seclusion. Their communal corporate rights were abolished, and the process of  The rabbi of Saxony had many sympathizers, who supported a similarly moderate approach and change only on the basis of the authority of the Talmud. When Geiger began preparing a third conference in Breslau,

The rabbi of Saxony had many sympathizers, who supported a similarly moderate approach and change only on the basis of the authority of the Talmud. When Geiger began preparing a third conference in Breslau,  Hirsch succeeded, severely tarnishing Frankel's reputation among most concerned. Along with fellow Orthodox Rabbi

Hirsch succeeded, severely tarnishing Frankel's reputation among most concerned. Along with fellow Orthodox Rabbi

Jewish immigration to the United States bred an amalgam of loose communities, lacking strong tradition or stable structures. In this free-spirited environment, a multitude of forces was at work. As early as 1866, Rabbi Jonas Bondi of New York wrote that a Judaism of the "golden middleway, which was termed Orthodox by the left and heterodox or reformer by the right" developed in the new country. The rapid ascendancy of

Jewish immigration to the United States bred an amalgam of loose communities, lacking strong tradition or stable structures. In this free-spirited environment, a multitude of forces was at work. As early as 1866, Rabbi Jonas Bondi of New York wrote that a Judaism of the "golden middleway, which was termed Orthodox by the left and heterodox or reformer by the right" developed in the new country. The rapid ascendancy of  Schechter arrived in 1902, and at once reorganized the faculty, dismissing both Pereira Mendes and Drachman for lack of academic merit. Under his aegis, the institute began to draw famous scholars, becoming a center of learning on par with HUC. Schechter was both traditional in sentiment and quite unorthodox in conviction. He maintained that theology was of little importance and it was practice that must be preserved. He aspired to solicit unity in American Judaism, denouncing sectarianism and not perceiving himself as leading a new denomination: "not to create a new party, but to consolidate an old one". The need to raise funds convinced him that a congregational arm for the Rabbinical Assembly and the JTS was required. On 23 February 1913, he founded the United Synagogue of America (since 1991: United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism), which then consisted of 22 communities. He and Mendes first came to major disagreement; Schechter insisted that any alumnus could be appointed to the USoA's managerial board, and not just to serve as communal rabbi, including several the latter did not consider sufficiently devout, or who tolerated mixed seating in their synagogues (though some of those he still regarded as Orthodox). Mendes, president of the Orthodox Union, therefore refused to join. He began to distinguish between the "Modern Orthodoxy" of himself and his peers in the OU, and "Conservatives" who tolerated what was beyond the pale for him. However, this first sign of institutionalization and separation was far from conclusive. Mendes himself could not clearly differentiate between the two groups, and many he viewed as Orthodox were members of the USoA. The epithets "Conservative" and "Orthodox" remained interchangeable for decades to come. JTS graduates served in OU congregations; many students of the Orthodox

Schechter arrived in 1902, and at once reorganized the faculty, dismissing both Pereira Mendes and Drachman for lack of academic merit. Under his aegis, the institute began to draw famous scholars, becoming a center of learning on par with HUC. Schechter was both traditional in sentiment and quite unorthodox in conviction. He maintained that theology was of little importance and it was practice that must be preserved. He aspired to solicit unity in American Judaism, denouncing sectarianism and not perceiving himself as leading a new denomination: "not to create a new party, but to consolidate an old one". The need to raise funds convinced him that a congregational arm for the Rabbinical Assembly and the JTS was required. On 23 February 1913, he founded the United Synagogue of America (since 1991: United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism), which then consisted of 22 communities. He and Mendes first came to major disagreement; Schechter insisted that any alumnus could be appointed to the USoA's managerial board, and not just to serve as communal rabbi, including several the latter did not consider sufficiently devout, or who tolerated mixed seating in their synagogues (though some of those he still regarded as Orthodox). Mendes, president of the Orthodox Union, therefore refused to join. He began to distinguish between the "Modern Orthodoxy" of himself and his peers in the OU, and "Conservatives" who tolerated what was beyond the pale for him. However, this first sign of institutionalization and separation was far from conclusive. Mendes himself could not clearly differentiate between the two groups, and many he viewed as Orthodox were members of the USoA. The epithets "Conservative" and "Orthodox" remained interchangeable for decades to come. JTS graduates served in OU congregations; many students of the Orthodox

The Conservative Synagogue

', Cambridge University Press, 1987. In 1927, the RA also established its own Committee of Jewish Law, entrusted with determining ''halakhic'' issues. Consisting of seven members, it was chaired by the traditionalist Rabbi Louis Ginzberg, who already distinguished himself in 1922, drafting a responsa that allowed the use of grape juice rather than fermented wine for '' Kiddush'' on the background of

In 1927, the RA also established its own Committee of Jewish Law, entrusted with determining ''halakhic'' issues. Consisting of seven members, it was chaired by the traditionalist Rabbi Louis Ginzberg, who already distinguished himself in 1922, drafting a responsa that allowed the use of grape juice rather than fermented wine for '' Kiddush'' on the background of

In 1946, a committee chaired by Gordis issued the ''Sabbath and Festival Prayerbook'', the first clearly Conservative liturgy: references to the sacrificial cult were in the past tense instead of a petition for restoration, and it rephrased blessings such as "who hast made me according to thy will" for women to "who hast made me a woman". During the movement's national conference in

In 1946, a committee chaired by Gordis issued the ''Sabbath and Festival Prayerbook'', the first clearly Conservative liturgy: references to the sacrificial cult were in the past tense instead of a petition for restoration, and it rephrased blessings such as "who hast made me according to thy will" for women to "who hast made me a woman". During the movement's national conference in

A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice

', Isaac Klein, JTS Press, New York, 1992 *''Conservative Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook'', Pamela S. Nadell, Greenwood Press, NY 1988 *''Etz Hayim: A Torah Commentary'', Ed. David Lieber,

The Jewish Theological SeminaryThe United Synagogue of Conservative JudaismThe Masorti Foundation for Conservative Judaism in Israel

{{Authority control Jewish religious movements

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a Jewish religious movement

Jewish religious movements, sometimes called " denominations", include different groups within Judaism which have developed among Jews from ancient times. Today, the most prominent divisions are between traditionalist Orthodox movements (includi ...

which regards the authority of ''halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'' (Jewish law) and traditions as coming primarily from its people and community through the generations moreso than from any divine revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

. It therefore views ''halakha'' as both binding and subject to historical development. The Conservative rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

nate employs modern historical-critical research, rather than only traditional methods and sources, and lends great weight to its constituency when determining its stance on matters of practice. The movement considers its approach as the authentic and most appropriate continuation of ''halakhic'' discourse, maintaining both fealty to received forms and flexibility in their interpretation. It also eschews strict theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

definitions, lacking a consensus in matters of faith and allowing great pluralism.

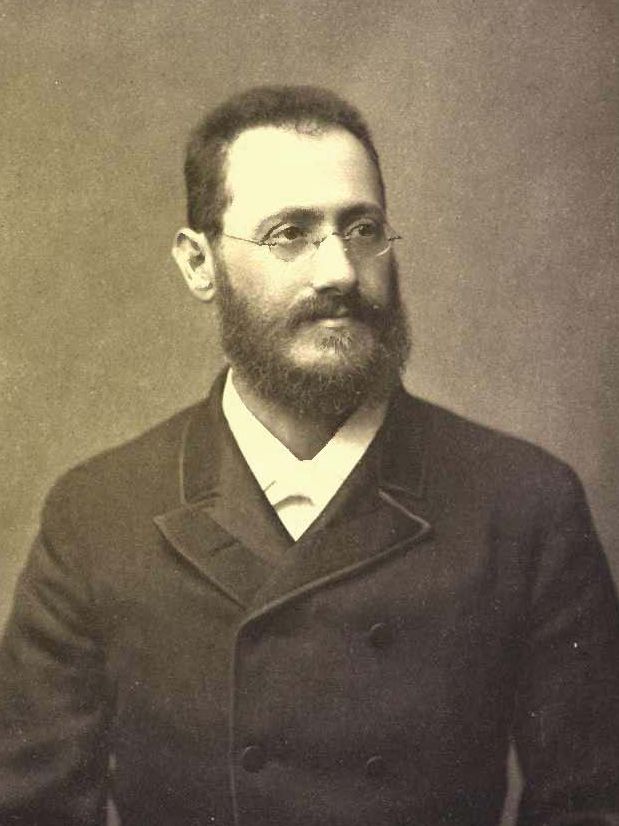

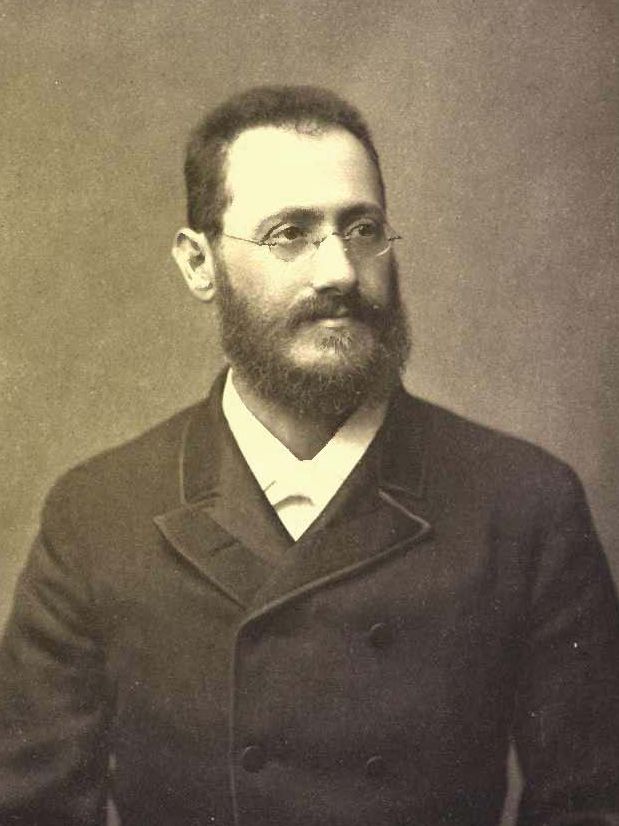

While regarding itself as the heir of Rabbi Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

's 19th-century Positive-Historical School in Europe, Conservative Judaism fully institutionalized only in the United States during the mid-20th century. Its largest center today is in North America, where its main congregational arm is the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) is the major congregational organization of Conservative Judaism in North America, and the largest Conservative Jewish communal body in the world. USCJ closely works with the Rabbinical Assembly ...

, and the New York–based Jewish Theological Seminary of America operates as its largest rabbinic seminary. Globally, affiliated communities are united within the umbrella organization Masorti Olami

Masorti Olami (also known as The World Council of Synagogues, Inc.) is the international umbrella organization for Masorti Judaism, founded in 1957 with the goal of making Masorti Judaism a force in the Jewish world. Masorti Olami is affiliated ...

. Conservative Judaism is the third-largest Jewish religious movement worldwide, estimated to represent close to 1.1 million people, including over 600,000 registered adult congregants and many non-member identifiers.

Theology

Attitude

Conservative Judaism, from its earliest stages, was marked by ambivalence and ambiguity in all matters theological. RabbiZecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

, considered its intellectual progenitor, believed the very notion of theology was alien to traditional Judaism. He was often accused of obscurity on the subject by his opponents, both Reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

and Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

. The American movement largely espoused a similar approach, and its leaders mostly avoided the field. Only in 1985 did a course about Conservative theology open in the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS). The hitherto sole major attempt to define a clear credo was made in 1988, with the Statement of Principles ''Emet ve-Emunah'' (Truth and Belief), formulated and issued by the Leadership Council of Conservative Judaism. The introduction stated that "lack of definition was useful" in the past but a need to articulate one now arose. The platform provided many statements citing key concepts such as God, revelation and Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

, but also acknowledged that a variety of positions and convictions existed within its ranks, eschewing strict delineation of principles and often expressing conflicting views. Alan Silverstein, ''Modernists vs. Traditionalists: Competition for Legitimacy within American Conservative Judaism'', in: ''Studies in Contemporary Jewry, Volume XVII'', Oxford University Press, 2001. pp. 40-43. In a 1999 special edition of '' Conservative Judaism'' dedicated to the matter, leading rabbis Elliot N. Dorff and Gordon Tucker clarified that "the great diversity" within the movement "makes the creation of a theological vision shared by all neither possible nor desirable".

God and eschatology

Conservative Judaism largely upholds thetheistic

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred t ...

notion of a personal God

A personal god, or personal goddess, is a deity who can be related to as a person, instead of as an impersonal force, such as the Absolute, "the All", or the "Ground of Being".

In the scriptures of the Abrahamic religions, God is described as b ...

. ''Emet ve-Emunah'' stated that "we affirm our faith in God as the Creator and Governor of the universe. His power called the world into being; His wisdom and goodness guide its destiny."

Concurrently, the platform also noted that His nature was "elusive" and subject to many options of belief. A naturalistic conception of divinity, regarding it as inseparable from the mundane world, once had an important place within the movement, especially represented by Mordecai Kaplan

Mordecai Menahem Kaplan (born Mottel Kaplan; June 11, 1881 – November 8, 1983), was a Lithuanian-born American rabbi, writer, Jewish educator, professor, theologian, philosopher, activist, and religious leader who founded the Reconstructionist ...

. After Kaplan's Reconstructionism fully coalesced into an independent movement, these views were marginalized.

A similarly inconclusive position is expressed toward other precepts. Most theologians adhere to the Immortality of the Soul

Christian mortalism is the Christian belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal and may include the belief that the soul is “sleeping” after death until the Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment, a time known as the inte ...

, but while references to the Resurrection of the Dead are maintained, English translations of the prayers obscure the issue. In ''Emet'', it was stated that death is not tantamount to the end of one's personality. Relating to the Messianic ideal, the movement rephrased most petitions for the restoration of the Sacrifices

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

into past tense, rejecting a renewal of animal offerings, though not opposing a Return to Zion and even a new Temple. The 1988 platform announced that "some" believe in classic eschatology, but dogmatism in this matter was "philosophically unjustified". The notions of Election of Israel and God's covenant with it were basically retained as well.

Revelation

Conservative conception ofRevelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

encompasses an extensive spectrum. Zecharias Frankel himself applied critical-scientific methods to analyze the stages in the development of the Oral Torah

According to Rabbinic Judaism, the Oral Torah or Oral Law ( he, , Tōrā šebbəʿal-pe}) are those purported laws, statutes, and legal interpretations that were not recorded in the Five Books of Moses, the Written Torah ( he, , Tōrā šebbīḵ ...

, pioneering modern study of the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tor ...

. He regarded the Beatified Sages as innovators who added their own, original contribution to the canon, not merely as expounders and interpreters of a legal system given in its entirety to Moses on Mount Sinai. Yet he also vehemently rejected utilizing these disciplines on the Pentateuch, maintaining it was beyond human reach and wholly celestial in origin. Frankel never elucidated his beliefs, and the exact correlation between human and divine in his thought is still subject to scholarly debate.Michael Meyer, ''Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism'', Wayne State, 1995. pp. 84-89, 414. A similar negative approach toward Higher Criticism, while accepting an evolutionary understanding of Oral Law, defined Rabbi Alexander Kohut

Alexander (Chanoch Yehuda) Kohut (April 22, 1842 – May 25, 1894) was a rabbi and orientalist. He belonged to a family of rabbis, the most noted among them being Rabbi Israel Palota, his great-grandfather, Rabbi Amram (called "The Gaon," who die ...

, Solomon Schechter

Solomon Schechter ( he, שניאור זלמן הכהן שכטר; 7 December 1847 – 19 November 1915) was a Moldavian-born British-American rabbi, academic scholar and educator, most famous for his roles as founder and President of the ...

and the early generation of American Conservative Judaism. When JTS faculty began to embrace Biblical criticism in the 1920s, they adapted a theological view consistent with it: an original, verbal revelation did occur at Sinai, but the text itself was composed by later authors. The latter, classified by Dorff as a relatively moderate metamorphosis of the old one, is still espoused by few traditionalist right-wing Conservative rabbis, though it is marginalized among senior leadership.

A small but influential segment within the JTS and the movement adhered, from the 1930s, to Mordecai Kaplan's philosophy that denied any form of revelation but viewed all scripture as a purely human product. Along with other Reconstructionist tenets, it dwindled as the latter consolidated into a separate group. Kaplan's views and the permeation of Higher Criticism gradually swayed most Conservative thinkers towards a non-verbal understanding of theophany

Theophany (from Ancient Greek , meaning "appearance of a deity") is a personal encounter with a deity, that is an event where the manifestation of a deity occurs in an observable way. Specifically, it "refers to the temporal and spatial manifest ...

, which has become dominant in the 1970s. This was en sync with the wider trend of lowering rates of Americans who accepted the Bible as the Word of God. Dorff categorized the proponents of this into two schools. One maintains that God projected some form of message which inspired the human authors of the Pentateuch to record what they perceived. The other is often strongly influenced by Franz Rosenzweig and other existentialists

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

, but also attracted many Objectivists

Objectivism is a philosophical system developed by Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement ...

who consider human reason paramount. The second school states that God conferred merely his presence on those he influenced, without any communication, and the experience drove them to spiritual creativity. While they differ in the theoretical level surrounding revelation, both practically regard all scripture and religious tradition as a human product with certain divine inspiration—providing an understanding that recognizes Biblical Criticism and also justifies major innovation in religious conduct. The first doctrine, advocated by such leaders as rabbis Ben-Zion Bokser and Robert Gordis, largely imparted that some elements within Judaism are fully divine but determining which would be impractical, and therefore received forms of interpretation should be basically upheld. Exponents of the latter view, among them rabbis Louis Jacobs and Neil Gillman, also emphasized the encounter of God with the Jews as a collective and the role of religious authorities through the generations in determining what it implied. The stress on the supremacy of community and tradition, rather than individual consciousness, defines the entire spectrum of Conservative thought.

Ideology

The Conservative mainstay was the adoption of the historical-critical method in understanding Judaism and setting its future course. In accepting an evolutionary approach to the religion, as something that developed over time and absorbed considerable external influences, the movement distinguished between the original meaning implied in traditional sources and the manner they were grasped by successive generations, rejecting belief in an unbroken chain of interpretation from God's original Revelation, immune to any major extraneous effects. This evolutionary perception of religion, while relatively moderate in comparison with more radical modernizers—the scholarship of the Positive-Historical school, for example, sought to demonstrate the continuity and cohesiveness of Judaism over the years—still challenged Conservative leaders.

They regarded tradition and received mores with reverence, especially the continued adherence to the mechanism of Religious Law (''

The Conservative mainstay was the adoption of the historical-critical method in understanding Judaism and setting its future course. In accepting an evolutionary approach to the religion, as something that developed over time and absorbed considerable external influences, the movement distinguished between the original meaning implied in traditional sources and the manner they were grasped by successive generations, rejecting belief in an unbroken chain of interpretation from God's original Revelation, immune to any major extraneous effects. This evolutionary perception of religion, while relatively moderate in comparison with more radical modernizers—the scholarship of the Positive-Historical school, for example, sought to demonstrate the continuity and cohesiveness of Judaism over the years—still challenged Conservative leaders.

They regarded tradition and received mores with reverence, especially the continued adherence to the mechanism of Religious Law (''Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

''), opposing indiscriminate modification, and emphasized they should be changed only with care and caution and remain observed by the people. Rabbi Louis Ginzberg, summarizing his movement's position, wrote:

This discrepancy between scientific criticism and insistence on heritage had to be compensated by a conviction that would forestall either deviation from accepted norms or laxity and apathy.

A key doctrine which was to fulfil this capacity was the collective will of the Jewish people. Conservatives lent great weight in determining religious practice, both in historical precedent and as a means to shape present conduct. Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

pioneered this approach; as Michael A. Meyer commented, "the extraordinary status which he ascribed to the ingrained beliefs and practices of the community is probably the most original element of his thought." He turned it into a source of legitimacy for both change and preservation, but mostly the latter. The basic moderation and traditionalism of the majority among the people were to guarantee a sense of continuity and unity, restraining the guiding rabbis and scholars who at his age were intent on reform but also allowing them manoeuvrability in adopting or discarding certain elements. Solomon Schechter

Solomon Schechter ( he, שניאור זלמן הכהן שכטר; 7 December 1847 – 19 November 1915) was a Moldavian-born British-American rabbi, academic scholar and educator, most famous for his roles as founder and President of the ...

espoused a similar position. He turned the old rabbinic concept of ''K'lal Yisrael'', which he translated as "Catholic Israel", into a comprehensive worldview. For him, the details of divine Revelation were of secondary significance, as historical change dictated its interpretation through the ages notwithstanding: "the centre of authority is actually removed from the Bible", he surmised, "and placed in some living body... in touch with the ideal aspirations and the religious needs of the age, best able to determine... This living body, however, is not represented by... priesthood, or Rabbihood, but by the collective conscience of Catholic Israel."

The scope, limits and role of this corpus were a matter for contention in Conservative ranks. Schechter himself used it to oppose any major break with either traditionalist or progressive elements within American Jewry of his day, while some of his successors argued that the idea became obsolete due to the great alienation of many from received forms, that had to be countered by innovative measures to draw them back. The Conservative rabbinate often vacillated on to which degree may the non-practicing, religiously apathetic strata be included as a factor within Catholic Israel, providing impulse for them in determining religious questions; even avant-garde leaders acquiesced that the majority could not serve that function. Right-wing critics often charged that the movement allowed its uncommitted laity an exaggerated role, conceding to its demands and successively stretching ''halakhic'' boundaries beyond any limit.

The Conservative leadership had limited success in imparting their worldview to the general public. While the rabbinate perceived itself as bearing a unique, original conception of Judaism, the masses lacked much interest, regarding it mainly as a compromise offering a channel for religious identification that was more traditional than Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous sear ...

yet less strict than Orthodoxy. Only a low percentage of Conservative congregants actively pursue an observant lifestyle: in the mid-1980s, Charles Liebman

Charles S. Liebman (Hebrew: ישעיהו ליבמן) (New York City October 20, 1934 – September 3, 2003) was a political scientist and prolific author on Jewish life and Israel. A professor at Bar-Ilan University, he previously served on un ...

and Daniel J. Elazar calculated that barely 3 to 4 per cent held to one quite thoroughly. This gap between principle and the public, more pronounced than in any other Jewish movement, is often credited at explaining the decline of the Conservative movement. While some 41 per cent of American Jews identified with it in the 1970s, it had shrunk to an estimated 18 per cent (and 11 per cent among those under 30) in 2013.

Jewish law

Role

Fidelity and commitment to ''Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'', while subject to criticism as disingenuous both from within and without, were and remain a cornerstone doctrine of Conservative Judaism. The movement views the legalistic system as normative and binding, and believes Jews must practically observe its precepts, like Sabbath, dietary ordinances, ritual purity, daily prayer with phylacteries and the like. Concurrently, examining Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, and their nation, religion, and culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions, and cultures. Although Judaism as a religion first appears in Greek records during the Hellenisti ...

and rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writ ...

through the lens of academic criticism, it maintained that these laws were always subject to considerable evolution, and must continue to do so. ''Emet ve-Emunah'' titled its chapter on the subject with "The Indispensability of Halakha", stating that "''Halakha'' in its developing form is an indispensable element of a traditional Judaism which is vital and modern." Conservative Judaism regards itself as the authentic inheritor of a flexible legalistic tradition, charging the Orthodox with petrifying the process and Reform with abandoning it.

The tension between "tradition and change"—which were also the motto adopted by the movement since the 1950s—and the need to balance them were always a topic of intense debate within Conservative Judaism. In its early stages, the leadership opposed pronounced innovation, mostly adopting a relatively rigid position. Mordecai Kaplan

Mordecai Menahem Kaplan (born Mottel Kaplan; June 11, 1881 – November 8, 1983), was a Lithuanian-born American rabbi, writer, Jewish educator, professor, theologian, philosopher, activist, and religious leader who founded the Reconstructionist ...

's Reconstructionism raised the demand for thoroughgoing modification without much regard for the past or ''halakhic'' considerations, but senior rabbis opposed him vigorously. Even in the 1940s and 1950s, when Kaplan's influence grew, his superiors rabbis Ginzberg, Louis Finkelstein

Louis Finkelstein (June 14, 1895 in Cincinnati, Ohio – 29 November 1991) was a Talmud scholar, an expert in Jewish law, and a leader of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS) and Conservative Judaism.

Biography

Louis (Eliezer) Fin ...

and Saul Lieberman

Saul Lieberman (Hebrew: שאול ליברמן, May 28, 1898 – March 23, 1983), also known as Rabbi Shaul Lieberman or, among some of his students, The ''Gra"sh'' (''Gaon Rabbeinu Shaul''), was a rabbi and a Talmudic scholar. He served as Professo ...

espoused a very conservative line. Since the 1970s, with the strengthening of the liberal wing within the movement, the majority in the Rabbinic Assembly opted for quite radical reformulations in religious conduct, but rejected the Reconstructionist non-''halakhic'' approach, insisting that the legalistic method be maintained. The ''halakhic'' commitment of Conservative Judaism has been subject to much criticism, from within and without. Right-wing discontents, including the Union for Traditional Judaism which seceded in protest of the 1983 resolution to ordain women rabbis—adopted at an open vote, where all JTS faculty regardless of qualification were counted—contested the validity of this description, as well as progressives like Rabbi Neil Gillman, who exhorted the movement to cease describing itself as ''halakhic'' in 2005, stating that after repeated concessions, "our original claim has died a death by a thousand qualifications... It has lost all factual meaning."

The main body entrusted with formulating rulings, responsa and statues is the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards

The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards is the central authority on halakha (Jewish law and tradition) within Conservative Judaism; it is one of the most active and widely known committees on the Conservative movement's Rabbinical Assembly. With ...

(CJLS), a panel with 25 voting legalistic specialists and further 11 observers. There is also the smaller ''Va'ad ha-Halakha'' (Law Committee) of Israel's Masorti Movement. Every responsa must receive a minimum of six voters to be considered an official position of the CJLS. Conservative Judaism explicitly acknowledges the principle of ''halakhic'' pluralism, enabling the panel to adopt more than one resolution in any given subject. The final authority in each Conservative community is the local rabbi, the ''mara d'atra'' (Lord of the Locality, in traditional terms), enfranchised to adopt either minority or majority opinions from the CJLS or maintain local practice. Thus, on the issue of admitting openly Homosexual rabbinic candidates, the Committee approved two resolutions, one in favour and one against; the JTS took the lenient position, while the Seminario Rabinico Latinoamericano

Seminario is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Diego Seminario (born 1989), Peruvian actor and industrial designer

* Juan Seminario (born 1936), Peruvian footballer

* Miguel Grau Seminario (1834–1879), Peruvian naval officer

...

still adheres to the latter. Likewise, while most Conservative synagogues approved of egalitarianism for women in religious life, some still maintain traditional gender roles and do not count females for prayer quorums.

Characteristics

The Conservative treatment of ''Halakha'' is defined by several features, though the entire range of its ''Halakhic'' discourse cannot be sharply distinguished from either the traditional or Orthodox one. Rabbi

The Conservative treatment of ''Halakha'' is defined by several features, though the entire range of its ''Halakhic'' discourse cannot be sharply distinguished from either the traditional or Orthodox one. Rabbi David Golinkin

David Golinkin (born 1955) is an American-born conservative rabbi and Jewish scholar who has lived in Jerusalem since 1972. He is President of the Schechter Institutes, Inc., President Emeritus of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies and Pr ...

, who attempted to classify its parameters, stressed that quite often rulings merely reiterate conclusions reached in older sources or even Orthodox ones. for example, in the details of preparing Sabbath ritual enclosures, it draws directly on the opinions of the ''Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulchan Aruch'' ( he, שֻׁלְחָן עָרוּך , literally: "Set Table"), sometimes dubbed in English as the Code of Jewish Law, is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Judaism. It was authored in Safed (today in I ...

'' and Rabbi Hayim David HaLevi

Hayim David HaLevi (24 January 1924 – 10 March 1998) (),

was Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv-Yafo.

Biography

Hayim David HaLevi was born in Jerusalem. He studied under Rabbi Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel at the Porat Yosef Yeshiva. When R. Uziel wa ...

. Another tendency prevalent among the movement's rabbis, yet again not particular to it, is the adoption of the more lenient positions on the matters at question—though this is not universal, and responsa also took stringent ones not infrequently.

A more distinctive characterization is a greater proclivity to base rulings on earlier sources, in the ''Rishonim

''Rishonim'' (; he, ; sing. he, , ''Rishon'', "the first ones") were the leading rabbis and '' poskim'' who lived approximately during the 11th to 15th centuries, in the era before the writing of the ''Shulchan Aruch'' ( he, , "Set Table", a ...

'' or before them, as far back as the Talmud. Conservative decisors frequently resort to less canonical sources, isolated responsa or minority opinions. They demonstrate more fluidity in regards to established precedent and continuum in rabbinic literature, mainly those by the later authorities, and lay little stress on the perceived hierarchy between major and minor legalists of the past. They are far more inclined to contend (''machloket'') with old rulings, to be flexible towards custom

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a r ...

or to wholly disregard it. This is especially expressed in less hesitancy to rule against or notwithstanding the major codifications of Jewish Law, like ''Mishne Torah

The ''Mishneh Torah'' ( he, מִשְׁנֵה תּוֹרָה, , repetition of the Torah), also known as ''Sefer Yad ha-Hazaka'' ( he, ספר יד החזקה, , book of the strong hand, label=none), is a code of Rabbinic Jewish religious law (''ha ...

'', ''Arba'ah Turim

''Arba'ah Turim'' ( he, אַרְבָּעָה טוּרִים), often called simply the ''Tur'', is an important Halakhic code composed by Yaakov ben Asher (Cologne, 1270 – Toledo, Spain c. 1340, also referred to as ''Ba'al Ha-Turim''). The f ...

'' and especially the ''Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulchan Aruch'' ( he, שֻׁלְחָן עָרוּך , literally: "Set Table"), sometimes dubbed in English as the Code of Jewish Law, is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Judaism. It was authored in Safed (today in I ...

'' with its Isserles Gloss and later commentaries. Conservative authorities, while often relying on the ''Shulchan Aruch'' themselves, criticize the Orthodox for relatively rarely venturing beyond it and overly canonizing Rabbi Joseph Karo's work. In several occasions, Conservative rabbis discerned that the ''Shulchan Aruch'' ruled without firm precedent, sometimes deriving his conclusions from the ''Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "receiver"). The defin ...

''. An important example is the ruling of Rabbi Golinkin—contrary to the majority consensus among the ''Acharonim

In Jewish law and history, ''Acharonim'' (; he, אחרונים ''Aḥaronim''; sing. , ''Aḥaron''; lit. "last ones") are the leading rabbis and poskim (Jewish legal decisors) living from roughly the 16th century to the present, and more specifi ...

'' and the more prominent ''Rishonim'', but based on many opinions of the lesser ''Rishonim'' which is derived from a minority view in the Talmud—that the Sabbatical Year

A sabbatical (from the Hebrew: (i.e., Sabbath); in Latin ; Greek: ) is a rest or break from work.

The concept of the sabbatical is based on the Biblical practice of ''shmita'' (sabbatical year), which is related to agriculture. According to ...

is not obligatory in present times at all (neither ''de'Oraita'' nor ''de'Rabanan'') but rather an act of piety.

Ethical considerations and the weight due to them in determining ''halakhic'' issues, mainly to what degree may modern sensibilities shape the outcome, are subject to much discourse. Right-wing decisors, like Rabbi Joel Roth

Joel Roth is a prominent American rabbi in the Rabbinical Assembly, which is the rabbinical body of Conservative Judaism. He is a former member and chair of the assembly's ''Committee on Jewish Law and Standards'' (CJLS) which deals with question ...

, maintained that such elements are naturally a factor in formulating conclusions, but may not alone serve as a justification for adopting a position. The majority, however, basically subscribed to the opinion evinced already by Rabbi Seymour Siegel

Seymour Siegel (September 12, 1927 - February 24, 1988), often referred to as "an architect of Conservative Jewish theology," was an American Conservative rabbi, a Professor of Ethics and Theology at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (J ...

in the 1960s, that the cultural and ethical norms of the community, the contemporary equivalents of Talmudic ''Aggadah

Aggadah ( he, ''ʾAggāḏā'' or ''Haggāḏā''; Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: אַגָּדְתָא ''ʾAggāḏəṯāʾ''; "tales, fairytale, lore") is the non-legalistic exegesis which appears in the classical rabbinic literature of Judaism ...

'', should supersede the legalistic forms when the two came into conflict and there was a pivotal ethical concern. Rabbi Elliot Dorff concluded that in contrast to the Orthodox, Conservative Judaism maintains that the juridical details and processes mainly serve higher moral purposes and could be modified if they no longer do so: "in other words, the ''Aggadah'' should control the ''Halakha''." The liberal Rabbi Gordon Tucker, along with Gillman and other progressives, supported a far-reaching implementation of this approach, making Conservative Judaism much more ''Aggadic'' and allowing moral priorities an overriding authority at all occasions. This idea became very popular among the young generation, but it was not fully embraced either. In the 2006 resolution on homosexuals, the CJLS chose a middle path: they agreed that the ethical consideration of human dignity was of supreme importance, but not sufficient to uproot the express Biblical prohibition on not to lie with mankind as with womankind (traditionally understood as banning full anal intercourse). All other limitations, including on other forms of sexual relations, were lifted. A similar approach is manifest in the great weight ascribed to sociological changes in deciding religious policy. The CJLS and the Rabbinical Assembly

The Rabbinical Assembly (RA) is the international association of Conservative rabbis. The RA was founded in 1901 to shape the ideology, programs, and practices of the Conservative movement. It publishes prayerbooks and books of Jewish interest, a ...

members frequently state that circumstances were profoundly transformed in modern times, fulfilling the criteria mandating new rulings in various fields (based on general talmudic principles like ''Shinui ha-I'ttim'', "Change of Times"). This, along with the ethical aspect, was a main argument for revolutionizing the role of women in religious life and embracing egalitarianism.

The most distinctive feature of Conservative legalistic discourse, in which it is conspicuously and sharply different from Orthodoxy, is the incorporation of critical-scientific methods into the process. Deliberations almost always delineate the historical development of the specific issue at hand, from the earliest known mentions until modern times. This approach enables a thorough analysis of the manner in which it was practiced, accepted, rejected or modified in various periods, not necessarily en sync with the received rabbinic understanding. Archaeology, philology and Judaic Studies

Jewish studies (or Judaic studies; he, מדעי היהדות, madey ha-yahadut, sciences of Judaism) is an academic discipline centered on the study of Jews and Judaism. Jewish studies is interdisciplinary and combines aspects of history (espe ...

are employed; rabbis use comparative compendiums of religious manuscripts, sometimes discerning that sentences were only added later or include spelling, grammar and transcription errors, changing the entire understanding of certain passages. This critical approach is central to the movement, for its historicist underpinning stresses that all religious literature has an original meaning relevant in the context of its formulation. This meaning may be analyzed and discerned, and is distinct from the later interpretations ascribed by traditional commentators. Decisors are also far more prone to include references to external scientific sources in relevant fields, like veterinarian publications in ''halakhic'' matters concerning livestock.

Conservative authorities, as part of their promulgation of a dynamic ''Halakha'', often cite the manner in which the sages of old used rabbinic statues (''Takkanah

A ''takkanah'' (plural ''takkanot'') is a major legislative enactment within ''halakha'' (Jewish law), the normative system of Judaism's laws. A ''takkanah'' is an enactment which revises an ordinance that no longer satisfies the requirements of t ...

'') that enabled to bypass prohibitions in the Pentateuch, like the ''Prozbul

The Prozbul ( he, פרוזבול of Greek origin; i.e. προσβολή, proz=Institution bouli= "Rich") was established in the waning years of the Second Temple of Jerusalem by Hillel the Elder. The writ, issued historically by rabbis, technical ...

'' or '' Heter I'ska''. In 1948, when employing those was first debated, Rabbi Isaac Klein argued that since there was no consensus on leadership within Catholic Israel, formulation of significant ''takkanot'' should be avoided. Another proposal, to ratify them only with a two-thirds majority in the RA, was rejected. New statues require a simple majority, 13 supporters among the 25 members of the CJLS. In the 1950s and 1960s, such drastic measures—as Rabbi Arnold M. Goodman cited in a 1996 writ allowing members of the priestly caste to marry divorcees, " Later authorities were reluctant to assume such unilateral authority... fear that invoking this principle would create the proverbial slippery slope, thereby weakening the entire ''halakhic'' structure... thus imposed severe limitations on the conditions and situations where it would be appropriate"—were carefully drafted as temporal, emergency ordinances (''Horaat Sha'ah''), grounded on the need the avoid a total rift of many nonobservant Jews. Later on, these ordinances became accepted and permanent on the practical level. The Conservative movement issued a wide range of new, thoroughgoing statues, from the famous 1950 responsum that allowed driving to the synagogue on the Sabbath and up to the 2000 decision to ban rabbis from inquiring about whether someone was a ''mamzer

In the Hebrew Bible and Jewish religious law, a ''mamzer'' ( he, ממזר, , "estranged person"; plural ''mamzerim'') is a person who is born as the result of certain forbidden relationships or incest (as it is defined by the Bible), or the de ...

'', de facto abolishing this legal category.

Rulings and policies

incandescent bulb

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxid ...

s, and therefore was not a forbidden labour and could be done on the Sabbath. On that basis, while performing banned labours is of course forbidden—for example, video recording is still constituted as writing—switching lights and other functions are allowed, though the RA strongly urges adherents to keep the sanctity of the Sabbath (refraining from doing anything that may imitate the atmosphere of weekdays, like loud noise reminiscent of work).

The need to encourage arrival at synagogue also motivated the CJLS, during the same year, to issue a temporal statue allowing driving on that day, for that purpose alone; it was supported by decreeing that the combustion of fuel did not serve any of the acts prohibited during the construction of the Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle ( he, מִשְׁכַּן, mīškān, residence, dwelling place), also known as the Tent of the Congregation ( he, link=no, אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, ’ōhel mō‘ēḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), ...

, and could therefore be classified, according to their interpretation of the Tosafists

Tosafists were rabbis of France and Germany, who lived from the 12th to the mid-15th centuries, in the period of Rishonim. The Tosafists composed critical and explanatory glosses (questions, notes, interpretations, rulings and sources) on the Ta ...

' opinion, as "redundant labour" (''Sh’eina Tzricha L’gufa'') and be permitted. The validity of this argument was heavily disputed within the movement. In 1952, members of the priestly caste were allowed to marry divorcees, conditioned on forfeiture of their privileges, as termination of marriage became widespread and women who underwent it could not be suspected of unsavory acts. In 1967, the ban on priests marrying converts was also lifted.

In 1954, the issue of ''agunot

An ''agunah'' ( he, עגונה, plural: agunot (); literally "anchored" or "chained") is a Jewish woman who is stuck in her religious marriage as determined by ''halakha'' (Jewish law). The classic case of this is a man who has left on a journey ...

'' (women refused divorce by their husbands) was largely settled by adding a clause to the prenuptial contract under which men had to pay alimony as long as they did not concede. In 1968, this mechanism was replaced by a retroactive expropriation of the bride price

Bride price, bride-dowry ( Mahr in Islam), bride-wealth, or bride token, is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the woman or the family of the woman he will be married to or is just about to marry. Bride dow ...

, rendering the marriage void. In 1955, more girls were celebrating Bat Mitzvah and demanded to be allowed ascents to the Torah, the CJLS agreed that the ordinance under which women were banned from this due to respect for the congregation (''Kvod ha'Tzibur'') was no longer relevant. In 1972 it was decreed that rennet, even if derived from unclean animals, was so transformed that it constituted a wholly new item (''Panim Chadashot ba'u l'Khan'') and therefore all hard cheese

There are many different types of cheese. Cheeses can be grouped or classified according to criteria such as length of fermentation, texture, methods of production, fat content, animal milk, and country or region of origin. The method most co ...

could be considered kosher.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the emergence of women's rights on the main agenda. Growing pressure led the CJLS to adopt a motion that females may be counted as part of a quorum, based on the argument that only the ''Shulchan Aruch'' explicitly stated that it consist of men. While accepted, this was very controversial in the Committee and heavily disputed. A more complete solution was offered in 1983 by Rabbi Joel Roth

Joel Roth is a prominent American rabbi in the Rabbinical Assembly, which is the rabbinical body of Conservative Judaism. He is a former member and chair of the assembly's ''Committee on Jewish Law and Standards'' (CJLS) which deals with question ...

, and was also enacted to allow women rabbinic ordination. Roth noted that some decisors of old acknowledged that women may bless when performing positive time-bound commandments (from which they are exempted, and therefore unable to fulfill the obligation for others), especially citing the manner in which they assumed upon themselves the Counting of the Omer

Counting of the Omer (, Sefirat HaOmer, sometimes abbreviated as Sefira or the Omer) is an important verbal counting of each of the forty-nine days starting with the Wave Offering of a sheaf of ripe grain with a sacrifice immediately following ...

. He suggested that women voluntarily commit to pray thrice a day et cetera, and his responsa was adopted. Since then, female rabbis were ordained at JTS and other seminaries. In 1994, the movement accepted Judith Hauptman

Judith Rebecca Hauptman (born 1943) is an American feminist Talmudic scholar.

Biography

She grew up in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, New York, United States.

Hauptman received a degree in Talmud from the Seminary College of Jewish S ...

's principally egalitarian argument, according to which equal prayer obligations for women were never banned explicitly and it was only their inferior status that hindered participation. In 2006, openly gay rabbinic candidates were also to be admitted into the JTS. In 2012, a commitment ceremony for same-sex couples was devised, though not defined as '' kiddushin''. In 2016, the rabbis passed a resolution supporting transgender rights.

Conservative Judaism in the United States held a relatively strict policy regarding intermarriage. Propositions for acknowledging Jews by patrilineal descent, as in the Reform movement, were overwhelmingly dismissed. Unconverted spouses were largely barred from community membership and participation in rituals; clergy are banned from any involvement in interfaith marriage on pain of dismissal. However, as the rate of such unions rose dramatically, Conservative congregations began describing gentile family members as ''K'rov Yisrael'' (Kin of Israel) and be more open toward them. The Leadership Council of Conservative Judaism stated in 1995: "we want to encourage the Jewish partner to maintain his/her Jewish identity, and raise their children as Jews."

Despite the centralization of legal deliberation on matters of Jewish law in the CJLS individual synagogues and communities must, in the end, depend on their local decision-makers. The rabbi in his or her or their community is regarded as the Mara D'atra, or the local halakhic decisor. Rabbis trained in the reading practices of Conservative Jewish approaches, historical evaluation of Jewish law and interpretation of Biblical and Rabbinic texts may align directly with the CJLS decisions or themselves opine on matters based on precedents or readings of text that shine light on congregants' questions. So, for instance, a rabbi may or may not choose to permit video streaming on Shabbat despite a majority ruling that allows for use of electronics. A local mara d'atra may rely on the reasoning found in the majority or minority opinions of the CJLS or have other textual and halakhic grounds, i.e., prioritizing Jewish values or legal concepts, to rule one way or another on matters of ritual, family life or sacred pursuits. This balance between a centralization of halakhic authority and maintaining the authority of local rabbis reflects the commitment to pluralism at the heart of the Movement.

Organization and demographics

The term ''Conservative Judaism'' was used, still generically and not yet as a specific label, already in the 1887 dedication speech of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America by RabbiAlexander Kohut

Alexander (Chanoch Yehuda) Kohut (April 22, 1842 – May 25, 1894) was a rabbi and orientalist. He belonged to a family of rabbis, the most noted among them being Rabbi Israel Palota, his great-grandfather, Rabbi Amram (called "The Gaon," who die ...

. By 1901, the JTS alumni formed the Rabbinical Assembly

The Rabbinical Assembly (RA) is the international association of Conservative rabbis. The RA was founded in 1901 to shape the ideology, programs, and practices of the Conservative movement. It publishes prayerbooks and books of Jewish interest, a ...

, of which all ordained Conservative clergy in the world are members. As of 2010, there were 1,648 rabbis in the RA. In 1913, the United Synagogue of America

The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) is the major congregational organization of Conservative Judaism in North America, and the largest Conservative Jewish communal body in the world. USCJ closely works with the Rabbinical Assembly, ...

, renamed the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism in 1991, was founded as a congregational arm of the RA. The movement established the World Council of Conservative Synagogues in 1957. Offshoots outside North America mostly adopted the Hebrew name "Masorti", traditional', as did the Israeli Masorti Movement, founded in 1979, and the British Assembly of Masorti Synagogues, formed in 1985. The World Council eventually changed its name to "Masorti Olami", Masorti International. Besides the RA, the international Cantors Assembly

Cantors Assembly (CA) is the international association of hazzanim (cantors) affiliated with Conservative Judaism. Cantors Assembly was founded in 1947 to develop the profession of the hazzan, to foster the fellowship and welfare of hazzanim, and t ...

supplies prayer leaders for congregations worldwide.

The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, covering the United States, Canada and Mexico, is by far the largest constituent of Masorti Olami. While most congregations defining themselves as "Conservative" are affiliated with the USCJ, some are independent. While accurate information of Canada is scant, it is estimated that some third of religiously affiliated Canadian Jews are Conservative. In 2008, the more traditional Canadian Council of Conservative Synagogues seceded from the parent organization. It numbered seven communities as of 2014. According to the Pew Research Center survey in 2013, 18 per cent of Jews in the United States identified with the movement, making it the second largest in the country. Steven M. Cohen calculated that as of 2013, 962,000 U.S. Jewish adults considered themselves Conservative: 570,000 were registered congregants and further 392,000 were not members in a synagogue but identified. In addition, Cohen assumed in 2006 that 57,000 unconverted non-Jewish spouses were also registered (12 per cent of member households had one at the time): 40 per cent of members intermarry. Conservatives are also the most aged group: among those aged under 30 only 11 per cent identified as such, and there are three people over 55 for every single one aged between 35 and 44. As of November 2015, the USCJ had 580 member congregations (a sharp decline from 630 two years prior), 19 in Canada and the remainder in the United States. In 2011 the USCJ initiated a plan to reinvigorate the movement.

Beyond North America, the movement has little presence—in 2011, Rela Mintz Geffen appraised there were only 100,000 members outside the U.S. (and the former figure including Canada). "Masorti AmLat", the MO branch in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

, is the largest with 35 communities in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, 7 in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, 6 in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

and further 11 in the other countries. The British Assembly of Masorti Synagogues has 13 communities and estimates its membership at over 4,000. More than 20 communities are spread across Europe, and there are 3 in Australia and 2 in Africa. The Masorti Movement in Israel incorporates some 70 communities and prayer groups with several thousand full members. In addition, while Hungarian Neolog Judaism, with a few thousands of adherents and forty partially active synagogues, is not officially affiliated with Masorti Olami, Conservative Judaism regards it as a fraternal, "non-Orthodox but halakhic" movement.

Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies

The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies, informally known as the "Ziegler School" or simply "Ziegler", is the graduate program of study, leading to ordination as a Conservative rabbi at the American Jewish University (formerly known as the Univers ...

at the American Jewish University

American Jewish University (AJU), formerly the separate institutions University of Judaism and Brandeis-Bardin Institute, is a Jewish institution in Los Angeles, California.

Its largest component is its Whizin Center for Continuing Education in ...

in Los Angeles; the Marshall T. Meyer Latin American Rabbinical Seminary (Spanish: ''Seminario Rabínico Latinoamericano Marshall T. Meyer''), in Buenos Aires, Argentina; and the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies

Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, ( he, מכון שכטר למדעי היהדות, ''Machon Schechter'') located in the Neve Granot neighborhood of Jerusalem, is an Israeli academic institution.

History

Founded in 1984 by the Jewish Theolo ...

in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. A Conservative institution that does not grant rabbinic ordination but which runs along the lines of a traditional yeshiva

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are st ...

is the Conservative Yeshiva

The Conservative Yeshiva is a co-educational institute for study of traditional Jewish texts in Jerusalem. The yeshiva was founded in 1995, and is under the

academic auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

The current Roshei Yes ...

, located in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. The Neolog Budapest University of Jewish Studies

The Budapest University of Jewish Studies ( hu, Országos Rabbiképző – Zsidó Egyetem, or Országos Rabbiképző Intézet / ''Jewish Theological Seminary – University of Jewish Studies'' / german: Landesrabbinerschule in Budapest) is a uni ...

also maintains connections with Conservative Judaism.

The current chancellor of the JTS is Shuly Rubin Schwartz Shuly Rubin Schwartz is the Chancellor and Irving Lehrman Research Professor of American Jewish History and Sala and Walter Schlesinger Dean of the Gershon Kekst Graduate School at The Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS). As Chancellor, she ...

, in office since 2020. She is the first woman elected to this position in the History of JTS. The current dean of the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies is Bradley Shavit Artson

Bradley Shavit "Brad" Artson (born 1959) is an American rabbi, author and speaker. He holds the Abner and Roslyn Goldstine Dean's Chair of the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies at the American Jewish University in Los Angeles, California, where ...

. The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards

The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards is the central authority on halakha (Jewish law and tradition) within Conservative Judaism; it is one of the most active and widely known committees on the Conservative movement's Rabbinical Assembly. With ...

is chaired by Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff, serving since 2007. The Rabbinical Assembly

The Rabbinical Assembly (RA) is the international association of Conservative rabbis. The RA was founded in 1901 to shape the ideology, programs, and practices of the Conservative movement. It publishes prayerbooks and books of Jewish interest, a ...

is headed by President Rabbi Debra Newman Kamin, as of 2019, and managed by Chief Executive Officer, Rabbi Jacob Blumenthal. Rabbi Blumenthal holds the joint position as CEO of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) is the major congregational organization of Conservative Judaism in North America, and the largest Conservative Jewish communal body in the world. USCJ closely works with the Rabbinical Assembly ...

. The current USCJ President is Ned Gladstein. In South America, Rabbi Ariel Stofenmacher serves as chancellor in the Seminary and Rabbi Marcelo Rittner as president of Masorti AmLat. In Britain, the Masorti Assembly is chaired by Senior Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg. In Israel, the Masorti movement's executive director is Yizhar Hess

Dr. Yizhar Hess (born July 5, 1967) has served as the Vice Chairman of the World Zionist Organization. He was elected to that role in 2020 as a representative of MERCAZ, the Zionist slate of the global Masorti/Conservative Movement. A long-time a ...

and chair Sophie Fellman Rafalovitz.

The global youth movement is known as NOAM, an acronym for No'ar Masorti; its North American organization is called United Synagogue Youth

United Synagogue Youth (USY) is the youth movement of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ). It was founded in 1951, under the auspices of the Youth Commission of what was then the United Synagogue of America.

USY operates in the ...

. Marom Israel is the Masorti movement's organization for students and young adults, providing activities based on religious pluralism and Jewish content. The Women's League for Conservative Judaism is also active in North America.

The USCJ maintains the Solomon Schechter Day Schools, comprising 76 day school

A day school — as opposed to a boarding school — is an educational institution where children and adolescents are given instructions during the day, after which the students return to their homes. A day school has full-day programs when compa ...

s in 17 American states and 2 Canadian provinces serving Jewish children. Many other "community day schools" that are not affiliated with Schechter take a generally Conservative approach, but unlike these, generally have "no barriers to enrollment based on the faith of the parents or on religious practices in the home".Jennifer SiegelWill Conservative Day Schools Survive?

June 5, 2008 During the first decade of the 21st century, a number of schools that were part of the Schechter network transformed themselves into non-affiliated community day schools. The USCJ also maintains the Camp Ramah system, where children and adolescents spend summers in an observant environment.

History

Positive-Historical School

The rise of modern, centralized states in Europe by the early 19th century heralded the end of Jewish judicial autonomy and social seclusion. Their communal corporate rights were abolished, and the process of

The rise of modern, centralized states in Europe by the early 19th century heralded the end of Jewish judicial autonomy and social seclusion. Their communal corporate rights were abolished, and the process of emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

and acculturation

Acculturation is a process of social, psychological, and cultural change that stems from the balancing of two cultures while adapting to the prevailing culture of the society. Acculturation is a process in which an individual adopts, acquires and ...

that followed quickly transformed the values and norms of the public. Estrangement and apathy toward Judaism were rampant. The process of communal, educational and civil reform could not be restricted from affecting the core tenets of the faith. The new academic, critical study of Judaism (''Wissenschaft des Judentums

"''Wissenschaft des Judentums''" (Literally in German the expression means "Science of Judaism"; more recently in the US it started to be rendered as "Jewish Studies" or "Judaic Studies," a wide academic field of inquiry in American Universities) ...

'') soon became a source of controversy. Rabbis and scholars argued to what degree, if at all, its findings could be used to determine present conduct. The modernized Orthodox in Germany, like rabbis Isaac Bernays

Isaac Bernays ( , , ; 29 September 1792 – 1 May 1849) was Chief Rabbi in Hamburg.

Life

Bernays was born in Weisenau (now part of Mainz). He was the son of Jacob Gera, a boarding house keeper at Mainz, and an elder brother of Adolphus Bernays. ...

and Azriel Hildesheimer

Azriel Hildesheimer (also Esriel and Israel, yi, עזריאל הילדעסהיימער; 11 May 1820 – 12 July 1899) was a German rabbi and leader of Orthodox Judaism. He is regarded as a pioneering moderniser of Orthodox Judaism in Germany an ...

, were content to cautiously study it while stringently adhering to the sanctity of holy texts and refusing to grant ''Wissenschaft'' any say in religious matters. On the other extreme were Rabbi Abraham Geiger

Abraham Geiger (Hebrew: ''ʼAvrāhām Gayger''; 24 May 181023 October 1874) was a German rabbi and scholar, considered the founding father of Reform Judaism. Emphasizing Judaism's constant development along history and universalist traits, Geig ...

, who would emerge as the founding father of Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous sear ...

, and his supporters. They opposed any limit on critical research or its practical application, laying more weight on the need for change than on continuity.

The Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

-born Rabbi Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

, appointed chief rabbi of the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony (german: Königreich Sachsen), lasting from 1806 to 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. The kingdom was formed from the Electorate of Saxo ...

in 1836, gradually rose to become the leader of those who stood at the middle. Besides working for the civic betterment of local Jews and educational reform, he displayed keen interest in ''Wissenschaft''. But Frankel was always cautious and deeply reverent towards tradition, privately writing in 1836 that "the means must be applied with such care and discretion... that forward progress will be reached unnoticed, and seem inconsequential to the average spectator." He soon found himself embroiled in the great disputes of the 1840s. In 1842, during the second Hamburg Temple controversy, he opposed the new Reform prayerbook, arguing the elimination of petitions for a future Return to Zion led by the Messiah was a violation of an ancient tenet. But he also opposed the ban placed on the tome by Rabbi Bernays, stating this was a primitive behaviour. In the same year, he and the moderate conservative S.L. Rapoport were the only ones of nineteen respondents who negatively answered the Breslau community's enquiry on whether the deeply unorthodox Geiger could serve there. In 1843, Frankel clashed with the radical Reform rabbi Samuel Holdheim

Samuel Holdheim (1806 – 22 August 1860) was a German rabbi and author, and one of the more extreme leaders of the early Reform Movement in Judaism. A pioneer in modern Jewish homiletics, he was often at odds with the Orthodox community.(Hist ...

, who argued that the act of marriage in Judaism

Marriage in Judaism is the documentation of a contract between a Jewish man and a Jewish woman in which God is involved. In Judaism, a marriage can end either because of a divorce document given by the man to his wife, or by the death of eit ...

was a civic (''memonot'') rather than sanctified () matter and could be subject to the Law of the Land. In December 1843 Frankel launched the magazine ''Zeitschrift für die Religiösen Interessen des Judenthums''. In the preamble, he attempted to present his approach to the present plight: "the further development of Judaism cannot be done through Reform that would lead to total dissipation... But must be involved in its study... pursued via scientific research, on a ''positive, historical'' basis." The term Positive-Historical became associated with him and his middle way. The ''Zeitschrift'' was, along the convictions of its publisher, neither dogmatically orthodox nor overly polemic, wholly opposing Biblical criticism and arguing for the antiquity of custom and practice.