Confederate Navy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the

One of the more well-known ships was the CSS ''Virginia'', formerly the sloop-of-war USS ''Merrimack'' (1855). In 1862, after being converted to an ironclad ram, she fought USS ''Monitor'' in the

One of the more well-known ships was the CSS ''Virginia'', formerly the sloop-of-war USS ''Merrimack'' (1855). In 1862, after being converted to an ironclad ram, she fought USS ''Monitor'' in the

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen had resigned or been dismissed from the United States Navy and had gone on to serve the Confederacy. The Provisional Congress meeting in Montgomery accepted these men into the Confederate Navy at their old rank. In order to accommodate them they initially provided for an officer corps to consist of four captains, four commanders, 30 lieutenants, and various other non-line officers. On 21 April 1862, the First Congress expanded this to four admirals, ten captains, 31 commanders, 100 first lieutenants, 25 second lieutenants, and 20 masters in line of promotion; additionally, there were to be 12 paymasters, 40 assistant paymasters, 22 surgeons, 15 passed assistant surgeons, 30 assistant surgeons, one engineer-in-chief, and 12 engineers. The act also provided for promotion on merit: "All the Admirals, four of the Captains, five of the Commanders, twenty-two of the First Lieutenants, and five of the Second Lieutenants, shall be appointed solely for gallant or meritorious conduct during the war."

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen had resigned or been dismissed from the United States Navy and had gone on to serve the Confederacy. The Provisional Congress meeting in Montgomery accepted these men into the Confederate Navy at their old rank. In order to accommodate them they initially provided for an officer corps to consist of four captains, four commanders, 30 lieutenants, and various other non-line officers. On 21 April 1862, the First Congress expanded this to four admirals, ten captains, 31 commanders, 100 first lieutenants, 25 second lieutenants, and 20 masters in line of promotion; additionally, there were to be 12 paymasters, 40 assistant paymasters, 22 surgeons, 15 passed assistant surgeons, 30 assistant surgeons, one engineer-in-chief, and 12 engineers. The act also provided for promotion on merit: "All the Admirals, four of the Captains, five of the Commanders, twenty-two of the First Lieutenants, and five of the Second Lieutenants, shall be appointed solely for gallant or meritorious conduct during the war."

https://lccn.loc.gov/2002019420

The Confederate Naval Historical Society

When Liverpool was Dixie

Liverpool – The Home of the Confederate Fleet

DANFS Online: Confederate States Navy

{{Authority control Military units and formations established in 1861 Disbanded navies 1861 establishments in the Confederate States of America Military history of the United States Maritime history of the United States 1865 disestablishments in the Confederate States of America

Confederate States Congress

The Confederate States Congress was both the provisional and permanent legislative assembly of the Confederate States of America that existed from 1861 to 1865. Its actions were for the most part concerned with measures to establish a new nat ...

on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

against the United States's Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

.

The three major tasks of the Confederate States Navy during its existence were the protection of Confederate harbors and coastlines from outside invasion, making the war costly for the United States by attacking its merchant ships worldwide, and running

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion allowing humans and other animals to move rapidly on foot. Running is a type of gait characterized by an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions). This i ...

the U.S. blockade by drawing off Union ships in pursuit of Confederate commerce raiders and warships.

It was ineffective in these tasks, as the coastal blockade by the United States Navy reduced trade by the South to 5 percent of its pre-war levels. Additionally, the control of inland rivers and coastal navigation by the US Navy forced the south to overload its limited railroads to the point of failure.

The surrender of the in Liverpool, England, marked the end of the Civil War and the Confederate Navy's existence.

History

The Confederate Navy could never achieve numerical equality with theUnion Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

, as its adversary had 70 years of traditions and experience. It instead sought to take advantage of technological innovation, such as ironclads, submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, torpedo boats

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of s ...

, and naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an ...

s (then known as torpedoes). In February 1861, the Confederate States Navy had 30 vessels, only 14 of which were seaworthy. The opposing Union Navy had 90 vessels. The C. S. Navy eventually grew to 101 ships to meet the rise in naval conflicts and threats to the coast and rivers of the Confederacy.

On April 20, 1861, the U.S. was forced to quickly abandon the important Gosport Navy Yard at Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth is an independent city in southeast Virginia and across the Elizabeth River from Norfolk. As of the 2020 census, the population was 97,915. It is part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area.

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Naval M ...

. In their haste, they failed to effectively burn the facility with its large depots of arms, other supplies, and several small vessels. As a result, the Confederacy captured a large supply of much-needed war materials, including heavy cannon, gunpowder, shot, and shell. Of most importance to the Confederacy was the shipyard's dry docks, barely damaged by the departing Union forces. The Confederacy's only substantial navy yard at that time was in Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal c ...

, so the Gosport Yard was sorely needed to build new warships. The most significant warship left at the Yard was the screw frigate USS ''Merrimack''

The U.S. Navy had torched ''Merrimacks superstructure and upper deck, then scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

the vessel; it would have been immediately useful as a warship to their enemy. Little of the ship's structure remained other than the hull, which was holed by the scuttling charge but otherwise intact. Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was a Democratic senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War. For much of that period, he was chairman of the Committee on Nav ...

had the idea to raise ''Merrimack'' and rebuild it. When the hull was raised, it had not been submerged long enough to have been rendered unusable; the steam engines and essential machinery were salvageable. The decks were rebuilt using thick oak and pine planking, and the upper deck was overlaid with two courses of heavy iron plate. The newly rebuilt superstructure was unusual: above the waterline, the sides sloped inward and were covered with two layers of heavy iron-plate armor, the inside course laid horizontally, the outside course laid vertically.

The vessel was a new kind of warship, an all-steam powered " iron-clad". In the centuries-old tradition of reusing captured ships, the new warship was christened CSS ''Virginia''. She later fought the Union's new ironclad USS ''Monitor''. On the second day of the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

, the two ships met and each scored numerous hits on the other. On the first day of that battle ''Virginia'', and the James River Squadron

The James River Squadron was formed shortly after the secession of Virginia during the American Civil War. The squadron was part of the Virginia Navy before being transferred to the Confederate States Navy. The squadron is most notable for its ...

, aggressively attacked and nearly broke the Union Navy's sea blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

of wooden warships, proving the effectiveness of the ironclad concept. The two ironclads had steamed forward, tried to outflank or ram the other, circled, backed away, and came forward firing again and again, but neither was able to sink or demand surrender of its opponent. After four hours, both ships were taking on water through split seams and breaches from enemy shot. The engines of both ships were becoming dangerously overtaxed, and their crews were near exhaustion. The two ships turned and steamed away, never to meet again. This part in the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

between ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' greatly overshadowed the bloody events each side's ground troops were fighting, largely because it was the first battle in history between two iron-armored steam-powered warships.

The last Confederate surrender took place in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

on November 6, 1865, aboard the commerce raider CSS ''Shenandoah'' when her flag

A flag is a piece of fabric (most often rectangular or quadrilateral) with a distinctive design and colours. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design empl ...

( battle ensign) was lowered for the final time. This surrender brought about the end of the Confederate navy. The ''Shenandoah'' had circumnavigated the globe, the only Confederate ship to do so.

Creation

The act of the Confederate Congress that created the Confederate Navy on February 21, 1861, also appointed Stephen Mallory as Secretary of the Department of the Navy. Mallory was experienced as an admiralty lawyer and had served for a time as the chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee of theUnited States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

. The Confederacy had a few scattered naval assets and looked to Liverpool, England, to buy naval cruisers to attack the American merchant fleet. In April 1861, Mallory recruited former U.S. Navy Lieutenant James Dunwoody Bulloch into the Confederate navy and sent him to Liverpool. Using Charleston-based importer and exporter Fraser Trentholm, who had offices in Liverpool, Commander Bulloch immediately ordered six steam vessels.

As Mallory began aggressively building up a formidable naval force, a Confederate Congress committee on August 27, 1862, reported:

In addition to the ships included in the report of the committee, the C.S. Navy also had one ironclad floating battery, presented to the Confederacy by the state of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, one ironclad ram

Ram, ram, or RAM may refer to:

Animals

* A male sheep

* Ram cichlid, a freshwater tropical fish

People

* Ram (given name)

* Ram (surname)

* Ram (director) (Ramsubramaniam), an Indian Tamil film director

* RAM (musician) (born 1974), Dutch

* ...

donated by the state of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, and numerous commerce raiders

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than eng ...

making war on Union merchant ships. When Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

seceded the Virginia Navy was absorbed into the Confederate Navy.

Naval flags

The practice of using primary and secondary naval flags after the British tradition was common practice for the Confederacy; the fledgling Confederate navy therefore adopted detailed flag requirements and regulations in the use of battle ensigns, naval jacks, as well as small boatensigns

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be differ ...

, commissioning pennants, designating flags, and signal flags aboard its warships. Changes to these regulations were made during 1863, when a new naval jack, battle ensign, and commissioning pennant design was introduced aboard all Confederate ships, echoing the Confederacys change of its national flag from the old " Stars and Bars" to the new "Stainless Banner

The flags of the Confederate States of America have a history of three successive designs during the American Civil War. The flags were known as the "Stars and Bars", used from 1861 to 1863; the "Stainless Banner", used from 1863 to 1865; and ...

". Despite the detailed naval regulations issued, minor variations in the flags were frequently seen, due to different manufacturing techniques employed, suppliers used, and the flag-making traditions of each southern state.

Privateers

On April 17, 1861,Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confed ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

invited applications for letters of marque and reprisal to be granted under the seal of the Confederate States, against ships and property of the United States and their citizens:

President Davis was not confident of his executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive di ...

authority to issue letters of marque and called a special session of Congress on April 29 to formally authorize the hiring of privateers in the name of the Confederate States. On 6 May the Confederate Congress passed "An act recognizing the existence of war between the United States and the Confederate States, and concerning letters of marque, prizes, and prize goods." Then, on May 14, 1861, "An act regulating the sale of prizes and the distribution thereof," was also passed. Both acts granted the president power to issue letters of marque and detailed regulations as to the conditions on which letters of marque should be granted to private vessels, the conduct and behavior of the officers and crews of such vessels, and the disposal of such prizes made by privateer crews. The manner in which Confederate privateers operated was generally similar to those of privateers of the United States or of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an nations.

The 1856 Declaration of Paris outlawed privateering for such nations as the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, but the United States had neither signed nor endorsed the declaration. Therefore, privateering was constitutionally legal in both the United States and the Confederacy, as well as Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. However, the United States did not acknowledge the Confederacy as an independent country and denied the legitimacy of any letters of marque issued by its government. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

declared all medicines to the Confederacy to be contraband and any captured Confederate privateers were to be hanged as pirates. Ultimately, no one was hanged for privateering because the Confederate government threatened to retaliate against U.S. prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

.

Initially, Confederate privateers operated primarily from , but activity was soon concentrated in the Atlantic, as the Union Navy began expanding its operations. Confederate privateers harassed Union merchant ships and sank several warships, although they were unable to relieve the blockade on Southern ports and its dire effects on the Confederate economy.

Ships

One of the more well-known ships was the CSS ''Virginia'', formerly the sloop-of-war USS ''Merrimack'' (1855). In 1862, after being converted to an ironclad ram, she fought USS ''Monitor'' in the

One of the more well-known ships was the CSS ''Virginia'', formerly the sloop-of-war USS ''Merrimack'' (1855). In 1862, after being converted to an ironclad ram, she fought USS ''Monitor'' in the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

, an event that came to symbolize the end of the dominance of large wooden sailing warships and the beginning of the age of steam and the ironclad warship.

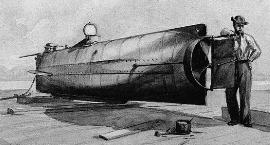

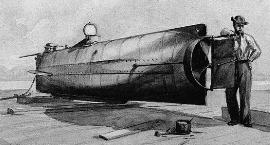

The Confederates also constructed submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, among the few that existed after the early ''Turtle'' of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Of those the ''Pioneer'' and the Bayou St. John submarine never saw action. However, ''Hunley'', built in Mobile as a privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

by Horace Hunley, later came under the control of the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

at Charleston, SC, but was manned partly by a C. S. Navy crew; she became the first submarine to sink a ship in a wartime engagement.

The ''Hunley'' later sank the sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' en ...

, resulting from the large blastwave that traveled from its exploding spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

's 500-pound black powder charge, during the sinking of USS Housatonic. The sinking of the Housatonic became the first successful submarine attack in history.

Confederate Navy commerce raiders were also used with great success to disrupt U.S. merchant shipping. The most famous of them was the screw sloop-of-war CSS ''Alabama'', a warship secretly built for the Confederacy in Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liv ...

, near Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

. She was launched as ''Enrica'' but was commissioned as CSS ''Alabama'' just off the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

by her captain, Raphael Semmes

Raphael Semmes ( ; September 27, 1809 – August 30, 1877) was an officer in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War. Until then, he had been a serving officer in the US Navy from 1826 to 1860.

During the American Civil War, Semmes ...

. She began her world-famous raiding career under his command, accounting for 65 U.S. ships, a record that still remains unbeaten by any ship in naval warfare. CSS ''Alabama'' s crew was mostly from Liverpool, and the cruiser never once dropped anchor in a Confederate port, though she sank a blockading Union gunboat off the coast of Texas. She was sunk in June 1864 by at the Battle of Cherbourg

The Battle of Cherbourg was part of the Battle of Normandy during World War II. It was fought immediately after the successful Allied landings on 6 June 1944. Allied troops, mainly American, isolated and captured the fortified port, which wa ...

outside the port of Cherbourg, France.

A similar raider, CSS ''Shenandoah'', fired the last shot of the American Civil War in late June 1865; she did not strike her colors and surrender until early November 1865, in Liverpool, England five months after the conflict had ended.

Organization

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen had resigned or been dismissed from the United States Navy and had gone on to serve the Confederacy. The Provisional Congress meeting in Montgomery accepted these men into the Confederate Navy at their old rank. In order to accommodate them they initially provided for an officer corps to consist of four captains, four commanders, 30 lieutenants, and various other non-line officers. On 21 April 1862, the First Congress expanded this to four admirals, ten captains, 31 commanders, 100 first lieutenants, 25 second lieutenants, and 20 masters in line of promotion; additionally, there were to be 12 paymasters, 40 assistant paymasters, 22 surgeons, 15 passed assistant surgeons, 30 assistant surgeons, one engineer-in-chief, and 12 engineers. The act also provided for promotion on merit: "All the Admirals, four of the Captains, five of the Commanders, twenty-two of the First Lieutenants, and five of the Second Lieutenants, shall be appointed solely for gallant or meritorious conduct during the war."

Between the beginning of the war and the end of 1861, 373 commissioned officers, warrant officers, and midshipmen had resigned or been dismissed from the United States Navy and had gone on to serve the Confederacy. The Provisional Congress meeting in Montgomery accepted these men into the Confederate Navy at their old rank. In order to accommodate them they initially provided for an officer corps to consist of four captains, four commanders, 30 lieutenants, and various other non-line officers. On 21 April 1862, the First Congress expanded this to four admirals, ten captains, 31 commanders, 100 first lieutenants, 25 second lieutenants, and 20 masters in line of promotion; additionally, there were to be 12 paymasters, 40 assistant paymasters, 22 surgeons, 15 passed assistant surgeons, 30 assistant surgeons, one engineer-in-chief, and 12 engineers. The act also provided for promotion on merit: "All the Admirals, four of the Captains, five of the Commanders, twenty-two of the First Lieutenants, and five of the Second Lieutenants, shall be appointed solely for gallant or meritorious conduct during the war."

Administration

The Department of the Navy was responsible for the administration of the affairs of the Confederate Navy and Confederate Marine Corps. It included various offices, bureaus, and naval agents in Europe. By July 20, 1861, the Confederate government had organized the administrative positions of the Confederate navy as follows: *Stephen R. Mallory

Stephen Russell Mallory (1812 – November 9, 1873) was a Democratic senator from Florida from 1851 to the secession of his home state and the outbreak of the American Civil War. For much of that period, he was chairman of the Committee on Na ...

– Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

* Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Samuel Barron – Chief of the Bureau of Orders and Detail

* Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

George Minor – Chief of Ordnance and Hydrography

* Paymaster John DeBree – Chief of Provisions and Clothing

* Surgeon W. A. W. Spottswood – Bureau of Medicine and Surgery

* Edward M. Tidball – Chief Clerk

Notable engagements

*Battle of Cherbourg

The Battle of Cherbourg was part of the Battle of Normandy during World War II. It was fought immediately after the successful Allied landings on 6 June 1944. Allied troops, mainly American, isolated and captured the fortified port, which wa ...

* Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip

* First Battle of Memphis

* Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

* Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

* Bahia incident

The Bahia incident was a naval skirmish fought in late 1864 during the American Civil War. A Confederate navy warship was captured by a Union warship in the Port of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. The engagement resulted in a United States victory ...

* Battle of the Head of Passes

* Siege of Fort Pulaski

* Battle of Plum Point Bend

* Action off Galveston Light

The action off Galveston Light was a short naval battle fought during the American Civil War in January 1863. Confederate raider encountered and sank the United States Navy steamer off Galveston Lighthouse in Texas.

Background

USS ''Hatter ...

Ranks

By 1862 regulations specified the uniforms and rank insignia for officers. Petty officers wore a variety of uniforms, or even regular clothing.Officers

Officers of the Confederate States Navy used, just like the army, a combination of several rank insignias to indicate their rank. While both hat insignia and sleeve insignia were used here the primary indicator were shoulder straps. Only line officers wore those straps shown below as officers of various staff departments (Medical, Pay, Engineering and Naval Construction) had separate ranks and different straps. Likewise the anchor symbol on the hats was substituted accordingly and they did not wear loops on the sleeve insignias. Paymasters, surgeons and chief engineers of more than twelve year's standing ranked with commanders. Paymasters, surgeons and chief engineers of less than twelve year's standing ranked with lieutenants. Assistant paymasters ranked with masters during the first five years of service, then with lieutenants. Passed assistant surgeons and professors ranked with masters. Assistant surgeons, first assistant engineers and secretaries to commanders of squadrons ranked with passed midshipmen. Second and third assistant engineers and clerks to commanding officers and paymasters ranked as midshipmen.Confederate States Navy Department (1862). ''Regulations for the Navy of the Confederate States.'' Richmond, pp. 8-9.Warrant and Petty Officers

Pay

''Annual pay for commissioned and warrant officers'' ;Notes ''Monthly pay for petty officers, men and boys''See also

* - the first Confederate ship to put to sea * Confederate States Marine Corps * Confederate States Lighthouse Bureau * List of ships of the Confederate States Navy *Blockade runners of the American Civil War

The blockade runners of the American Civil War were seagoing Steamships, steam ships that were used to get through the Union blockade that extended some along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastlines and the lower Mississippi River. The Confe ...

* Confederate army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

* Uniforms of the Confederate States military forces

* Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

* Military history of African Americans in the U.S. Civil War

* Mississippi River in the American Civil War

Notes

References

Further reading

* * Campbell, R. Thomas. ''Southern Thunder: Exploits of the Confederate States Navy'', White Maine Publishing, 1996. . * Campbell, R. Thomas. ''Southern Fire: Exploits of the Confederate States Navy'', White Maine Publishing, 1997. . * Campbell, R. Thomas. ''Fire and Thunder: Exploits of the Confederate States Navy'', White Maine Publishing, 1997. . * * Hussey, John. "Cruisers, Cotton and Confederates" (details the story of Liverpool-built ships for the Confederate Navy and a host of characters and places within the city of that era: James Dunwoody Bulloch, C. K. Prioleau, and many others). Countyvise, 2009. . * Krivdo, Michael E.''The Confederate Navy and Marine Corps'' in James C. Bradford, ed. ''A Companion to American Military History'' (2 vol 2009) 1:460-471 * Luraghi, Raymond. ''A History of the Confederate Navy'', Naval Institute Press, 1996. . * Madaus, H. Michael. ''Rebel Flags Afloat: A Survey of the Surviving Flags of the Confederate States Navy, Revenue Service, and Merchant Marine''. Winchester, MA,Flag Research Center

Whitney Smith Jr. (February 26, 1940 – November 17, 2016) was a professional vexillologist and scholar of flags. He originated the term ''vexillology'', which refers to the scholarly analysis of all aspects of flags. He was a founder of se ...

, 1986. . (An 80-page special edition of "The Flag Bulletin" magazine, #115, devoted entirely to Confederate naval flags.)

* McPherson, James M. ''War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865.'' Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2012.

*

* Stern, Philip Van Doren. ''The Confederate Navy: A Pictorial History'', Doubleday & Company, Garden City, NY, 1962.

* Still, William N., ed. ''The Confederate Navy: the ships, men and organization, 1861–65'' (Conway Maritime Pr, 1997)

*

*

* Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. ''Life in Jefferson Davis' Navy.'' Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

* Woodward, David. "Launching The Confederate Navy." ''History Today'' (Mar 1962) 12#3 pp 206–212.

* The Rebel Raiders: The Astonishing History of the Confederacy's Secret Navy (book) External links

The Confederate Naval Historical Society

When Liverpool was Dixie

Liverpool – The Home of the Confederate Fleet

DANFS Online: Confederate States Navy

{{Authority control Military units and formations established in 1861 Disbanded navies 1861 establishments in the Confederate States of America Military history of the United States Maritime history of the United States 1865 disestablishments in the Confederate States of America