Colorado Coalfield War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Colorado Coalfield War was a major labor uprising in the Southern and Central

In 1903, the

In 1903, the

The Coalfield Strikes of 1913–1914 began in the late summer of 1913 when the

The Coalfield Strikes of 1913–1914 began in the late summer of 1913 when the  General John Chase had been the leader of the National Guard units charged with the suppression of the 1903–1904 Cripple Creek Strike and was disposed positively towards the mine guards and hired detectives that would eventually supplement his ranks. CF&I vehicles and other infrastructure were regularly employed by the Guard for the duration of the strike. Chase, in his position at the head of the Colorado National Guard, embraced an aggressive stance against the strikers.

Though there were strikes in places such as Walsenburg and Trinidad, the largest of the strike colonies was in Ludlow. It had around 200 tents with 1,200 miners. The escalating situation caused

General John Chase had been the leader of the National Guard units charged with the suppression of the 1903–1904 Cripple Creek Strike and was disposed positively towards the mine guards and hired detectives that would eventually supplement his ranks. CF&I vehicles and other infrastructure were regularly employed by the Guard for the duration of the strike. Chase, in his position at the head of the Colorado National Guard, embraced an aggressive stance against the strikers.

Though there were strikes in places such as Walsenburg and Trinidad, the largest of the strike colonies was in Ludlow. It had around 200 tents with 1,200 miners. The escalating situation caused

A Colorado and Southern (C&S) route that connected the

A Colorado and Southern (C&S) route that connected the

Due to the influence of the Colorado National Guard and Greek Union leaders, such as Louis Tikas in Ludlow Colony, the strike had become relatively peaceful by the beginning of 1914. The strikers and the Guardsmen sat opposite each other at Ludlow, with brown tents for the soldiers appearing on the opposite side of the track from the white ones belonging to the colonists starting in November 1913.

There was still tension, though, and on 14 January Linderfelt was accused of hitting Tikas while at Ludlow in retaliation for Tikas not divulging the whereabouts of a boy related to an incident in which Linderfelt and his men ran into

Due to the influence of the Colorado National Guard and Greek Union leaders, such as Louis Tikas in Ludlow Colony, the strike had become relatively peaceful by the beginning of 1914. The strikers and the Guardsmen sat opposite each other at Ludlow, with brown tents for the soldiers appearing on the opposite side of the track from the white ones belonging to the colonists starting in November 1913.

There was still tension, though, and on 14 January Linderfelt was accused of hitting Tikas while at Ludlow in retaliation for Tikas not divulging the whereabouts of a boy related to an incident in which Linderfelt and his men ran into

The news of the massacre soon reached the other tent colonies, including the large group of strikers in Walsenburg. The response was a decentralized expedition throughout Southern and Central Colorado known as the "Ten Days War." At this point the union made an official "Call to Arms", a departure from their previous policy of suppressing violence on the part of the strikers. This led to widespread violence across the Southern Colorado Coalfield area, unlike the small pockets of violence that occurred in canyons in the early days of the strike.

Popular opinion began to side with the miners. Newspapers that had previously sided with the company and Ammons, such as the ''

The news of the massacre soon reached the other tent colonies, including the large group of strikers in Walsenburg. The response was a decentralized expedition throughout Southern and Central Colorado known as the "Ten Days War." At this point the union made an official "Call to Arms", a departure from their previous policy of suppressing violence on the part of the strikers. This led to widespread violence across the Southern Colorado Coalfield area, unlike the small pockets of violence that occurred in canyons in the early days of the strike.

Popular opinion began to side with the miners. Newspapers that had previously sided with the company and Ammons, such as the '' By the evening of the 22nd, Lt. Gov. Fitzgarrald was attempting to secure a ceasefire through UMWA's influential

By the evening of the 22nd, Lt. Gov. Fitzgarrald was attempting to secure a ceasefire through UMWA's influential

In the weeks following the federal intervention, the

In the weeks following the federal intervention, the

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

Front Range

The Front Range is a mountain range of the Southern Rocky Mountains of North America located in the central portion of the U.S. State of Colorado, and southeastern portion of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is the first mountain range encountered ...

between September 1913 and December 1914. Striking began in late summer 1913, organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against the Rockefeller Rockefeller is a German surname, originally given to people from the village of Rockenfeld near Neuwied in the Rhineland and commonly referring to subjects associated with the Rockefeller family. It may refer to:

People with the name Rockefeller f ...

-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) after years of deadly working conditions and low pay. The strike was marred by targeted and indiscriminate attacks from both strikers and individuals hired by CF&I to defend its property. Fighting was focused in the southern coal-mining counties of Las Animas and Huerfano, where the Colorado and Southern railroad passed through Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and Walsenburg

The City of Walsenburg is the Statutory City that is the county seat and the most populous municipality of Huerfano County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 3,049 at the 2020 census, down from 3,068 in 2010.

History

Walsenb ...

. It followed the 1912 Northern Colorado Coalfield Strikes.

Tensions climaxed at the Ludlow Colony, a tent city

A tent city is a temporary housing facility made using tents or other temporary structures.

State governments or military organizations set up tent cities to house evacuees, refugees, or soldiers. UNICEF's Supply Division supplies expandable te ...

occupied by about 1,200 striking coal miner

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

s and their families, in the Ludlow Massacre on 20 April 1914 when the Colorado National Guard

The Colorado National Guard consists of the Colorado Army National Guard and Colorado Air National Guard, forming the state of Colorado's component to the United States National Guard. Founded in 1860, the Colorado National Guard falls under th ...

attacked. In retaliation, armed miners attacked dozens of mines and other targets over the next ten days, killing strikebreakers

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the str ...

, destroying property, and engaging in several skirmishes with the National Guard along a 225-mile (362 km) front from Trinidad to Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, north of Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

. Violence largely ended following the arrival of federal soldiers in late April 1914, but the strike did not end until December 1914. No concessions were made to the strikers. An estimated 69 to 199 people died during the strike, though the total dead counted in official local government records and contemporary news reports is far lower. Described as the "bloodiest labor dispute in American history" and "bloodiest civil insurrection in American history since the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

," the Colorado Coalfield War is notable for the number of company-aligned dead in a period when strikebreaking violence typically saw fatalities exclusively among strikers.

Background

In 1903, the

In 1903, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company

The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) was a large steel conglomerate founded by the merger of previous business interests in 1892.Scamehorn, Chapter 1, "The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1892-1903" page 10 By 1903 it was mainly owned and con ...

was taken over from its founder, John C. Osgood, by a group of Colorado-based board members and investors with the support of John D. Rockefeller. Osgood was the wealthiest Coloradan at the time, and founded the Victor-American Fuel Company Victor-American Fuel Company, also styled as the Victor Fuel Company, was a coal mining company, primarily focused on operations in the US states of Colorado and New Mexico during the first half of the Twentieth Century. Prior to a 1909 reorganiza ...

later that year.

Colorado Fuel and Iron's treatment of its workers degraded after its sale to John D. Rockefeller, who gave his portion of the company to his son John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist, and the only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller.

He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in ...

as a birthday gift. The company already had a history of buying political figures and banking "graft," but Lamont Montgomery Bowers–who was hired to “untangle the mess”–caused additional issues. Bowers, made chairman of the CF&I board in 1907, admitted that company had "mighty power in the entire state." Under his leadership, every employee–regardless of citizenship status–as well as company mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two po ...

s were registered to vote. The workers were coerced to vote for the company's interests. He cut the Sociological

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation and ...

Department and embraced the idea of a hands-off approach to employee management. This caused rampant dishonesty in middle management Middle management is the intermediate management level of a hierarchical organization that is subordinate to the executive management and responsible for ‘team leading’ line managers and/or ‘specialist’ line managers. Middle management is i ...

, to the detriment of the mine workers. Despite the reduction of the Sociological Department's involvement in some aspects employees' lives, there was still enforcement of certain societal regulations. A later federal report would claim CF&I was censoring literature in the company towns, prohibiting "socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

" texts as well as books described by a CF&I spokesman as containing "erroneous ideas," including Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

''.

Miners were generally paid according to tonnage of coal produced, while so-called "dead work", such as shoring up unstable roofs, was often unpaid. The tonnage system drove many poor and ambitious colliers to gamble with their lives by neglecting precautions and taking on risk, with consequences that were often fatal. CF&I was accused by both miners and federal investigators of occasionally not assigning checkweighmen "in order that the miners might be cheated of part of their earnings."

Between 1884 and 1912, Colorado's fatality rate among miners was more than double the national average, with 6.81 miners killed for every 1,000 workers (against a national average of 3.12). In the decade preceding the 1913-1914 Strike, CF&I mines had been involved in several major accidents. These included the 31 January 1910 explosion that killed 75 at the Primero Mine and the Starkville Mine explosion that killed 56 on 8 October of that year. Both of these accidents took place in Las Animas County

Las Animas County is a county located in the U.S. state of Colorado. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,555. The county seat is Trinidad. The county takes its name from the Mexican Spanish name of the Purgatoire River, originally ...

, part of what became the strike zone and where the Ludlow Colony was established. These incidents raised the fatality rate in Colorado to above 10 deaths per 1,000 workers, three times the national average. Due to jury tampering by the companies, very few accident lawsuits were launched; between 1895 and 1915, no personal injury

Personal injury is a legal term for an injury to the body, mind or emotions, as opposed to an injury to property. In common law jurisdictions the term is most commonly used to refer to a type of tort lawsuit in which the person bringing the suit (t ...

lawsuits were launched against coal mining companies in Huerfano County. In the case of the 1910 Primero accident, a coroner's report issued after five days absolved CF&I of any civil or criminal responsibility. Additionally, a high rate of disease afflicted the minefields, with at least 151 inhabitants of CF&I company towns contracting typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

in the year preceding the 1913-1914 strike.

In April 1912, the Northern Colorado Coalfield Strikes slowly ended following several years of striking and negotiations. This strike had seen internal tensions between different districts of UMWA miners, as some members of neighboring districts were recruited as strikebreakers, leading some members of the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

, through their publication '' Industrial Worker'', to claim "autonomous district organization is on par with scabbery." In its aftermath, the National Guard prepared for additional violence by constructing fortifications, including the large cobblestone Golden Armory in June 1913.

Since the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903–1904, CF&I had spent $20,000 annually () on private detectives and security to monitor and infiltrate unions. Baldwin-Felts spy Charles Lively was among the most successful in his infiltration, rising to the position of vice-president of the UMWA local. Bowers viewed these private investigators as “grafters” and sought to cut ties with them. However, local CF&I fuel manager E. H. Weitzel retained Pinkerton detectives in the Southern Colorado coalfields to monitor the collective organizing of miners in the region. Federal investigators would later cite these armed guards and spies, as well at their utilization of "the whole machine of the law" in the "persecution of organizers and union members," as among the primary reasons for strikers taking arms against CF&I.

The Copper County Strike of copper workers in Calumet, Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and t ...

, for nine months from 1913 to 1914, ran concurrently with the Colorado strike, and both strikers and Guardsmen were aware of the events in Michigan through coverage in ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Coll ...

'' and other nationally circulating publications.

Beginning of the strike

United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

organized its regional District 15, led by John McLennan, to represent Southern Coloradan coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

field workers and put forward demands to Colorado Fuel and Iron. Demands that emphasized enforcement of new regulatory laws were not met. Among the demands unheeded was the enforcement of a mine-safety bill passed in 1913 which required better ventilation in the mines, but which had no enforcement provision. On 16 September 1913, miners with and union members with District 15 adopted demands for a seven-step improvement to the wage scale of miners and company recognition of the UMWA.

In December 1912, the UMWA had sent 21 "recruiting teams" to the Southern Colorado coalfields. These recruiting teams generally consisted of two union men: one who would embed himself among the miners and another who would find employment with the local management. Working in tandem, each pairing would locate miners who were opposed to unionization and report them to the company as union sympathizers–an offense that generally resulted in contract termination–in order to covertly replace them with genuine union members. It is possible that up to 3,000 UMWA members were introduced to the coalfields in such a manner.

In Southern Colorado, an expanded strike began on 23 September 1913 during a rainstorm. That day, the strike peaked with up to 20,000 miners and family members being evicted from company housing. Prior to the eviction, there had been plans to move them all into union supplied tents. Eight tent colonies were supposed to have been constructed with materials from the UMWA in anticipation such an eventuality, but most of the tents arrived late, leading some families to resort to using furniture as improvised shelters. Despite internal statistics at CF&I that suggested only 10 percent of miners were union-members, Rockefeller was informed soon after the strike began that between 40 and 60 percent of the miners in the strike zone had left work, which became roughly 80.5 percent–7,660 men–by the 24th.

Jesse F. Welborn, the president of CF&I, announced he would not meet with the strikers and that the confrontation “would be a strike to the finish.” The day the strike was declared, Mother Jones led a march on the Trinidad town hall, giving a brief speech outside and inside:

During this initial stage of the strike, Governor Ammons met several times with Welborn, Osgood, and David W. Brown–representing CF&I, Victor-American, and the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company The Rocky Mountain Fuel Company was a coal mining company located in Colorado, operating mines in Louisville, Lafayette, and other locations northwest of Denver. The company also operated mines in Las Animas, Routt, Garfield and Gunnison counties. D ...

respectively. Ammons intended to facilitate a summit between these corporate leaders to several of the union heads so that the strike might end quickly. However, following belligerent statements on both sides, such a conference never transpired.

Most sheriffs and deputy sheriffs in the area were affiliated in some fashion with CF&I and the other major mining companies and acted as an initial force against the strikers. Their numbers were bolstered as the strike began by recruiting of new sheriffs and deputies, including Karl Linderfelt

Karl E. Linderfelt (November 7, 1876 – June 3, 1957) was a soldier, mine worker, soldier of fortune, and officer in the Colorado National Guard. He was reported to have been responsible for an attack upon, and the ultimate death of, strike lea ...

, who later led the militia. Many of those deputized, and at least 66 in two days, were from Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, while others were from New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

.

General John Chase had been the leader of the National Guard units charged with the suppression of the 1903–1904 Cripple Creek Strike and was disposed positively towards the mine guards and hired detectives that would eventually supplement his ranks. CF&I vehicles and other infrastructure were regularly employed by the Guard for the duration of the strike. Chase, in his position at the head of the Colorado National Guard, embraced an aggressive stance against the strikers.

Though there were strikes in places such as Walsenburg and Trinidad, the largest of the strike colonies was in Ludlow. It had around 200 tents with 1,200 miners. The escalating situation caused

General John Chase had been the leader of the National Guard units charged with the suppression of the 1903–1904 Cripple Creek Strike and was disposed positively towards the mine guards and hired detectives that would eventually supplement his ranks. CF&I vehicles and other infrastructure were regularly employed by the Guard for the duration of the strike. Chase, in his position at the head of the Colorado National Guard, embraced an aggressive stance against the strikers.

Though there were strikes in places such as Walsenburg and Trinidad, the largest of the strike colonies was in Ludlow. It had around 200 tents with 1,200 miners. The escalating situation caused Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Elias Ammons to call in the Colorado National Guard in October 1913, but after six months all but two companies were withdrawn for financial reasons. However, during this six-month period, guardsmen were allowed to leave if their primary livelihood was threatened and many of the guardsmen were “new recruits”–mine guards and strikebreakers in National Guard uniforms.

As was common in mine strikes of the time, the company also brought in strikebreakers and Baldwin-Felts detectives. These detectives had experience from West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

strikes in which they had defended themselves from violent strikers. Balwin-Felts detectives George Belcher and Walker Belk had killed UMWA organizer Gerald Liappiat in Trinidad on 16 August 1913, five weeks before the strikes began. The widely-reported public killing of Liappiat in what was deemed by a coroner's jury a "justifiable homicide" during a two-sided gunfight had helped inflame tensions in the region.

Further detectives were brought into the state once the strike commenced. Upon arrival, these between 40 and 75 detectives were deputized as county sheriffs. The Baldwin-Felts were also responsible for the recruitment of mine guards meant for service directly under CF&I.

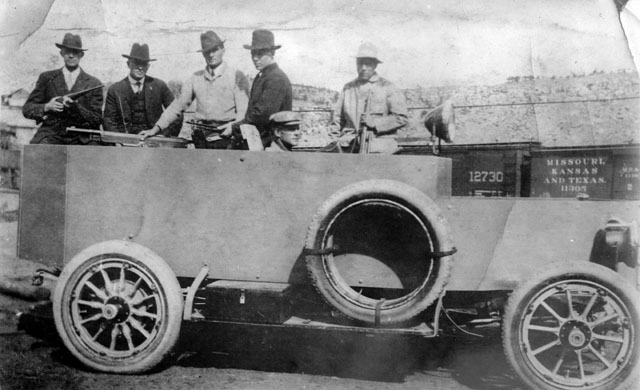

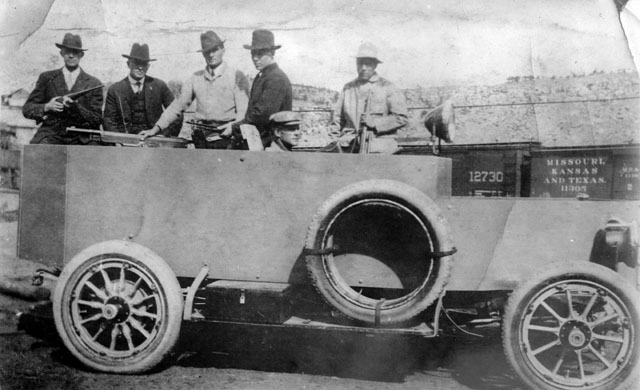

The Baldwin-Felts and CF&I had an armored car nicknamed the ''Death Special'', which was equipped with a machine gun, as well as eight machine guns purchased by CF&I from the Coal Operators' Association of West Virginia–a mining company association. Three additional machine guns reached the strike zone by the end of the conflict, though how these weapons were sourced is uncertain. ''Death Special'' was constructed at a CF&I shop in Pueblo

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

for company use against their striking workers and passed on to the militia later in the conflict. Prior to being distributed to the militia, company-employed detectives were accused of firing randomly into and above the miners' colonies from ''Death Special''.

The strikers also armed themselves through private sales, primarily through local private dealers. Colorado gun dealers are recorded as having sold to both sides in the various calibers that were commercially popular at the time–especially .45-70 and .22 Long Rifle

The .22 Long Rifle or simply .22 LR or 22 (metric designation: 5.6×15mmR) is a long-established variety of .22 caliber rimfire ammunition originating from the United States. It is used in a wide range of rifles, pistols, revolvers, smo ...

. Dealers in Walsenburg and Pueblo also sold explosives to both sides of the conflict, though the investigating congressional committee

A congressional committee is a legislative sub-organization in the United States Congress that handles a specific duty (rather than the general duties of Congress). Committee membership enables members to develop specialized knowledge of the ...

noted they did "not believe a majority of the people of Colorado such actions."

Violence early in the strike

September 1913

On 24 September, a marshal employed by CF&I named Robert Lee was attempting the arrest of four strikers accused of vandalism when he was ambushed and killed at Segundo. Another lawman later testified that Lee had been particularly hated by the strikers for his insults against their wives.October 1913

A Colorado and Southern (C&S) route that connected the

A Colorado and Southern (C&S) route that connected the Front Range

The Front Range is a mountain range of the Southern Rocky Mountains of North America located in the central portion of the U.S. State of Colorado, and southeastern portion of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is the first mountain range encountered ...

and passed near the Ludlow Colony began to be used as a firing position to harass strikers on 8 October 1913, resulting in no immediate casualties.

At roughly 1:30 PM on 9 October 1913, a striking miner who had been hired as a rancher, Mark Powell, was herding cattle near patrolling CF&I mine guards. The guards were passing near a C&S train bridge. A sudden burst of gunfire erupted, sending the guards to cover and killing Powell. His death came the same day four pieces of artillery arrived in the strike zone with a National Guard company. News of the incident resulted in a run

Run(s) or RUN may refer to:

Places

* Run (island), one of the Banda Islands in Indonesia

* Run (stream), a stream in the Dutch province of North Brabant

People

* Run (rapper), Joseph Simmons, now known as "Reverend Run", from the hip-hop group ...

on guns in Trinidad.

A mine in Dawson, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

collapsed on 22 October, killing 263 miners. The disaster was at the time the worst mining disaster in the Western United States. It served to further raise ire amongst the miners and added perceived legitimacy to the UMWA strike just north of the Colorado-New Mexico border.

On 24 October, a day after Governor Ammons left the strike zone, Walsenburg Sheriff Jeff Farr recruited 55 deputies. Later that day, while escorting a set of wagons belonging to a non-striking family on Seventh Street, the deputies fired into a hostile crowd, killing three foreign miners. Fearing a military response, an armed group of Greek strikers were sent by John Lawson to prevent troops from arriving in the area by the C&S train, and they fired with little effect on it as it passed through. Lieutenant Linderfelt, one of the first deputized into the militia, then led a group of 20 militiamen to hold a section house along the railway a half-mile south of Ludlow when at 3PM they came under fire from strikers in elevated positions on the ridges. John Nimmo, a mine guard and National Guardsman from Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, was killed early in the engagement. A relief force of 40 militia and Baldwin-Felts arrived with a machine gun after the fighting had shifted to the multiple camps in nearby Berwind Canyon. This, coupled with a snowstorm

A winter storm is an event in which wind coincides with varieties of precipitation that only occur at freezing temperatures, such as snow, mixed snow and rain, or freezing rain. In temperate continental climates, these storms are not necessar ...

, broke up the battle.

The National Guard was mobilized on 28 October and began field operations the next day. The next day, several buildings were set on fire in Aguilar, including a post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional se ...

and a mine. The Guard later arrested several strikers in relation to this arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wate ...

and handed them over to the U.S. Marshal Service

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforceme ...

.

November 1913

After an agreement between General Chase and John Lawson, on 1 November the National Guard marched between the mines and tent colonies to effect a disarmament on both sides. The military report of the incident records a warm reception by the strikers, especially those at Ludlow who created a band to herald the arrival of soldiers, though the National Guard only received a reported 20–30 weapons, including atoy gun

Toy guns are toys which imitate real guns, but are designed for recreational sport or casual play by children. From hand-carved wooden replicas to factory-produced pop guns From Gilroy Gardens and cap guns, toy guns come in all sizes, price ...

.

On the morning of 8 November, at the Oakview Mine, in the La Veta Pass

La Veta Pass is the name associated with two nearby mountain passes in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of south central Colorado in the United States, both lying on the boundary between Costilla and Huerfano counties.

Old La Veta Pass (officially ...

and near the pro-union town of the same name, pro-union men began harassing " scabs"–non-striking and strikebreaking miners. William Gambling rejected offers to join the union on his way to the local dentist

A dentist, also known as a dental surgeon, is a health care professional who specializes in dentistry (the diagnosis, prevention, management, and treatment of diseases and conditions of the oral cavity and other aspects of the craniofacial c ...

and, returning in a mail carrier

A mail carrier, mailman, mailwoman, postal carrier, postman, postwoman, or letter carrier (in American English), sometimes colloquially known as a postie (in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom), is an employee of a post ...

's car with three CF&I company men, was ambushed. Gambling was the only survivor. The militia rounded up several men after finding a pile of repeating rifle A repeating rifle is a single-barreled rifle capable of repeated discharges between each ammunition reloads. This is typically achieved by having multiple cartridges stored in a magazine (within or attached to the gun) and then fed individually in ...

s. Also that morning, strikebreaker Pedro Armijo was being escorted through a crowd of strike-supporters when he was shot in the head. The bullet wounded striker Michele Guerriero, who lost an eye and was arrested by the militia, who held him for three months on suspicion of knowing who fired the bullet. Later that day, the National Guard reported that strikers assaulted Herbert Smith, a clerk working at the McLaughlin Mine. The Military Commission held three or four men in relation to the Smith attack before releasing them to civil authorities.

The National Guard reported that on 18 November the Piedmont home of Domenik Peffello, a miner who had quit the strike, was dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

d. Peffello likely lost his home after returning to it upon abandoning the Piedmont tent colony.

Baldwin-Felts detective George Belcher was killed by Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

striker Louis Zancanelli in Trinidad on 22 November in what the National Guard's official report deemed an assassination. Zancanelli was sentenced to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes fo ...

for the murder, though this conviction was overturned in 1917 when the trial was determined to have been improperly judged.

December 1913

Mine guard Robert McMillen was shot and killed at Delagua, a mine owned by Colorado's second-largest coal company, Victor-American Fuel Company, and which had been one of the first mines to go on strike, on 2 December. On 17 December, the National Guard, under orders from Gov. Ammons from 1 December, allowed for the strikebreakers to resume entering the strike zone following a brief moratorium on any workers other than those already present in Southern Colorado working.January 1914

The return of Mother Jones to Trinidad on 11 January resulted in considerable response. She was arrested shortly thereafter by the National Guard on the orders of Ammons and taken to Mt. San Rafael Hospital. She was held repeatedly over the next nine months. Strikers attempted to liberate Jones from her first detention on the 21st by marching on the hospital but failed to secure her release after being repulsed by mounted National Guardsmen. She would remain held in Mt. San Rafael for nine weeks. On 27 January, the National Guard reported discovering an unexploded bomb near their camp at Walsenburg, estimating that it could have killed many of the troops stationed there. The Guard used this incident, which resulted in new arrests, as evidence of striker aggression towards the military in the region. The same day, theUnited States House Committee on Mines and Mining The United States House Committee on Mines and Mining is a defunct committee of the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Committee on Mines and Mining was created on December 19, 1865, for consideration of subjects relating to mining interests. It e ...

opened an investigation on both the Northern and Southern Colorado Coalfield strikes, as well as the Calumet strike. The report pertaining to the Southern Colorado strike was released on 2 March 1915. The UMWA would legally challenge the National Guard imprisonment of four strikers in Las Animas County on ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

'' grounds, while the National Guard stated the imprisonments were permitted by previous court rulings and the Posse Comitatus Act. The court sided with the National Guard on 29 January.

Events before Ludlow

Due to the influence of the Colorado National Guard and Greek Union leaders, such as Louis Tikas in Ludlow Colony, the strike had become relatively peaceful by the beginning of 1914. The strikers and the Guardsmen sat opposite each other at Ludlow, with brown tents for the soldiers appearing on the opposite side of the track from the white ones belonging to the colonists starting in November 1913.

There was still tension, though, and on 14 January Linderfelt was accused of hitting Tikas while at Ludlow in retaliation for Tikas not divulging the whereabouts of a boy related to an incident in which Linderfelt and his men ran into

Due to the influence of the Colorado National Guard and Greek Union leaders, such as Louis Tikas in Ludlow Colony, the strike had become relatively peaceful by the beginning of 1914. The strikers and the Guardsmen sat opposite each other at Ludlow, with brown tents for the soldiers appearing on the opposite side of the track from the white ones belonging to the colonists starting in November 1913.

There was still tension, though, and on 14 January Linderfelt was accused of hitting Tikas while at Ludlow in retaliation for Tikas not divulging the whereabouts of a boy related to an incident in which Linderfelt and his men ran into barbed wire

A close-up view of a barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire, is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strands. Its primary use is ...

on a path. The official report by the National Guard detachment commander at Aguilar to General Chase on 18 January denied the claim, as did a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

to Governor Ammons sent personally from Linderfelt. Lawson, however, asserted in a telegram to Ammons that Linderfelt had used the "vilest of language" towards the boy in question and had said to the strikers "I am Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

, and my men on horses are Jesus Christs, and we must be obeyed." Lawson also suggested Linderfelt had acted with the intention of provoking the strikers to violence.

On 8 March 1914 the body of a strikebreaker, Neil Smith, was found on the train tracks near the Forbes tent colony, located near the then-emptied Rocky Mountain Fuel Company town of the same name, an incident that occurred as a congressional committee

A congressional committee is a legislative sub-organization in the United States Congress that handles a specific duty (rather than the general duties of Congress). Committee membership enables members to develop specialized knowledge of the ...

was touring the area. The National Guard claimed that the colony harbored the murderers and was "so established that no workmen ouldleave the camp at Forbes without passing along or through" the colony. In retaliation, the Guard destroyed the colony on 10 March, burning it to the ground while most inhabitants were away and arresting all 16 men living in the tents, an action that indirectly resulted in the deaths of two newborn children.

Mother Jones, who had already been arrested twice by the militia, again traveled south on 22 March in an effort to reach Trinidad. Arriving in Walsenburg by train, the militia arrested her and held her in a Huerfano County jail. At 76 years old, she was held for 26 days in the subterranean cell. Pro-union publications used this detention as a rallying call, exaggerating the squalid qualities of the cell and claiming she was an even older, more fragile woman than she was.

Battle and Massacre at Ludlow

On the morning of April 20, 1914, the day after theEastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

's Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel P ...

and after months of increased tension between the armed factions, the Ludlow Massacre occurred. The withdrawal of the majority of the National Guard had left only two companies of troops in the strike area, with these soldiers spread across several encampments at Berwind, Ludlow, and Cedar Hill. On Sunday, 19 April, it was reported that a group of union-aligned women playing baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

at Ludlow exchanged insults with National Guardsmen, one of whom is reported as saying to the women, "Go ahead, have your good time to-day, and to-morrow we will get your roast." On the morning of 20 April, Tikas was summoned by soldiers claiming a woman sought to speak to her husband, a supposed resident of the Ludlow Colony. Tikas refused the initial invitation to meet in the soldiers' tent. Major Patrick Hamrock

Patrick J. Hamrock (1860-1939) was an Irish-born American soldier who served in multiple conflicts as part of the U.S. Army and Colorado National Guard. He led a portion of the militia that participated in the Ludlow Massacre, part of the 19 ...

, the Irish-born leader of the "Rocky Mountain Sharpshooters" and a veteran of the Wounded Knee Massacre, persuaded Tikas to meet at the Ludlow train stop. Tikas told his agitated fellow Greek strikers to remain calm.

Sensing the militia's intent to act that day after seeing machine guns placed above the colony and choosing to disobey Tikas, strikers took cover in hastily constructed fire positions. Accounts of who fired the first shot differ, but fighting began or escalated after the militia at Ludlow detonated warning charges to notify Linderfelt's troops stationed at Berwind Canyon and the another detachment at Cedar Hill. In total, some 177 militia and soldiers participated in the fighting.

By 9:30 AM, the gunfire had begun to reach its peak intensity. Families of the strikers sought shelter in cellars beneath their tents as the fighting raged through the morning and until past 5 PM. National Guardsmen fired a machine gun from Water Tank Hill, an elevated position above the colony that had served as an observation post

An observation post (commonly abbreviated OP), temporary or fixed, is a position from which soldiers can watch enemy movements, to warn of approaching soldiers (such as in trench warfare), or to direct fire. In strict military terminology, an ...

for much of strike. A twelve year old, Frank Snyder, left his shelter and was hit by a bullet that removed much of his head, killing him instantly. National Guardsman Pvt. Martin was fatally shot in the neck. M. G. Low, a pumpman for the Colorado & Southern train that passed through the town, witnessed the fighting and moved a train engine to protect some of those fleeing the battle and directed them towards cover.

At the end of the battle, a fire began and the colony burnt down. Soon after the gunfire ended, Tikas and other strikers were found shot in the back along with those strikers who were killed in the combat. Eleven children and two women were found suffocated by smoke in one of the subterranean cellars. All together, at least 18 of the union side had been killed–including Snyder and those seeking shelter in the cellar–while Martin is the only confirmed casualty from the Guard. Due to the fighting and chaos, Rev. John O. Ferris, Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

minister of Trinity Church in Trinidad and St. Mary's in Aguilar, and a small group of others from the nearby communities were among the few permitted into the still-smoldering tent colony. Ferris and his band would discover the dead in the cellar and extracted them to perform hasty Christian burial

A Christian burial is the burial of a deceased person with specifically Christian rites; typically, in consecrated ground. Until recent times Christians generally objected to cremation because it interfered with the concept of the resurrection o ...

s. Soon after the discoveries, a Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

party would visit and photograph the cellar.

During the 1915 Commission on Industrial Relations Congressional hearings on the massacre, Rockefeller maintained that he was not aware of any animosity among the deputized militia subsidized by CF&I, nor that had he ordered the massacre, despite accusations to the contrary from activists including Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth contro ...

. The national media lambasted Rockefeller, who had prior to the Ludlow Massacre claimed no responsibility for the strike and violence, saying "My conscience will acquit me."

The "Ten Days War"

The news of the massacre soon reached the other tent colonies, including the large group of strikers in Walsenburg. The response was a decentralized expedition throughout Southern and Central Colorado known as the "Ten Days War." At this point the union made an official "Call to Arms", a departure from their previous policy of suppressing violence on the part of the strikers. This led to widespread violence across the Southern Colorado Coalfield area, unlike the small pockets of violence that occurred in canyons in the early days of the strike.

Popular opinion began to side with the miners. Newspapers that had previously sided with the company and Ammons, such as the ''

The news of the massacre soon reached the other tent colonies, including the large group of strikers in Walsenburg. The response was a decentralized expedition throughout Southern and Central Colorado known as the "Ten Days War." At this point the union made an official "Call to Arms", a departure from their previous policy of suppressing violence on the part of the strikers. This led to widespread violence across the Southern Colorado Coalfield area, unlike the small pockets of violence that occurred in canyons in the early days of the strike.

Popular opinion began to side with the miners. Newspapers that had previously sided with the company and Ammons, such as the ''Daily Camera

The ''Daily Camera'' is a newspaper in Boulder, Colorado, United States. It is owned by Prairie Mountain Publishing, a division of Digital First Media.

History

Frederick P. Johnson and Bert Bell founded the weekly ''Boulder Camera'' in 1890, and ...

'' and ''Rocky Mountain News

The ''Rocky Mountain News'' (nicknamed the ''Rocky'') was a daily newspaper published in Denver, Colorado, United States, from April 23, 1859, until February 27, 2009. It was owned by the E. W. Scripps Company from 1926 until its closing. As ...

'', began to sympathize with the strikers and blame "dilly-dallying" on Ammons' part for the deaths. The generally anti-union ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' declared the massacre "worse than the order sent to the Light Brigade into the jaws of death, worse in its effect than the Black Hole of Calcutta

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring , in which troops of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, held British prisoners of war on the night of 20 June 1756. John Zephaniah Holwell, one of the Britis ...

."

While strikers were divided on how to respond, some sought revenge on non-striking miners, attacking Southwestern Mine Co.'s Empire Mine on Wednesday, 22 April, only to relent after a 21-hour siege. Armed strikebreakers killed two strikers at the loss of the mine's superintendent. A minister named McDonald from nearby Aguilar heard the fighting and rightly feared the strikers intended to kill all those at the Empire Mine. Following the deaths of the two strikers and the discovery of a union organizer willing to discuss terms, McDonald and the Aguilar mayor negotiated a ceasefire that resulted in the strikers withdrawing. However, before the siege broke, national news outlets began erroneously reporting that the families trapped in the Empire Mine were likely suffocated. Three mine guards were killed at Delagua, where four attempts were made by strikers to take the town, and another was killed at Tabasco. These events led the sheriff of Las Animas County to send a telegram to Ammons, declaring that he had been militarily defeated by the miners and requested federal intervention.

By the evening of the 22nd, Lt. Gov. Fitzgarrald was attempting to secure a ceasefire through UMWA's influential

By the evening of the 22nd, Lt. Gov. Fitzgarrald was attempting to secure a ceasefire through UMWA's influential Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

lawyer Horace Hawkins. The following day, John McLennan, the president of UMWA District 15 when the strike was declared, was arrested by militia at the Ludlow train stop on his way from Denver to Trinidad. Hawkins made a ceasefire conditional on McLennan's release, which was secured. Despite union anger at Hawkins for negotiating, they observed the truce along what had become a front.

At midnight on 22 April, a call went out for all National Guardsmen to head for the strike zone. Chase had claimed prior to Ludlow that he was able to muster 600 men to return to the field at a moment's notice, yet only 362 men reported for duty. Seventy-six soldiers of Troop C–nicknamed "Chase Troop" as two of the general's sons along with other family members were part of the unit– mutinied, as they had been forced to stay in an uncomfortable Guard armory on little pay since returning from their initial deployment to the strike zone. Troop C did not return to coalfields for the duration of the conflict. Two field guns and 220 rounds of shrapnel shell

Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel artillery munitions which carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell's trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almo ...

s were brought with the 23-car train of 242 soldiers going south from Denver on 23 April. Empty carts were attached to the front of the engines to protect against dynamite traps. A group of pro-strikers sought to deliver weapons by car before Chase's troops arrived in Walsenburg and, despite delays, managed to bring guns and ammunition to the strikers before the train full of troops reached the strike zone. The newly arrived troops were then spread out in attempts to bring the region under their control.

Through the day on 25 April the Chandler Mine near Cañon City was fired upon, representing the first major breach of the truce declared days before. A force of an estimated one thousand armed strikers launched a coordinated assault on the town, culminating in its capture on 26 April. A non-striking miner was killed and a mine guard seriously injured before National Guardsmen arrived.

Following the renewed violence, the majority of Walsenburg's civilian population fled and sporadic fighting began to overrun the city. Striking Greek miners, dissatisfied with a perceived lack of response from union officials to Ludlow, began organizing guerrilla attacks in the town and mustered 300 strikers to attack the McNally Mine located nearby, killing one. With the return of open hostilities came an increased formalization of military operations on both sides, with the union and militia forces each publishing communiqués reporting casualties and advances while diminishing the claimed successes of their opponents.

A sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

by over a thousand members of the Women's Peace Association–led by Alma Lafferty, Helen Ring Robinson

Helen Ring Robinson (1878–1923), was an American suffragist, writer, and political office holder. She was either the first or the second woman to serve as a state senator in the United States and the first in the Colorado State Senate. She wa ...

, and Dora Phelps–paralyzed the Capitol building on 25 April. These women forced a "drawn and haggard" Ammons to send a request for U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

to send federal troops to the strike zone. A rally attended by five to six thousand agitated protesters and Colorado senator–and later governor– Charles Thomas stood in front of the Capitol the next day. Despite the presence of dozens of police officers and a rainstorm, the crowds listened peacefully to speakers from the mines as well as the impassioned journalist, propagandist, and former Denver Police Commissioner George Creel

George Edward Creel (December 1, 1876 – October 2, 1953) was an American investigative journalist and writer, a politician and government official. He served as the head of the United States Committee on Public Information, a propaganda organ ...

. Among the demands of the crowd was the impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

of Governor Ammons.

The northernmost battle took place on 28 April at the Hecla mine in Louisville. The mine was owned by the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, which had hired the Baldwin-Felts to help protect its property between Denver and Boulder

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive.

In ...

. During the ten-hour battle, Captain Hildreth Frost

Hildreth Frost (1880–1955) was a lawyer and soldier from Colorado who commanded Company A of the 2nd Infantry Regiment during the Colorado Coalfield War. He also served as Judge Advocate for the military courts-martial for prosecuting members ...

led a small contingent of troops that had been among those rotated off the southern front. Several mine guards were seriously injured during the fighting.

Battle of Walsenburg, 27–29 April

The large 27 April funeral for Tikas in Trinidad strained the militia forces of Colonel Edward Verdeckberg of the National Guard. Verdeckberg, a veteran of the 1903-1904 Cripple Creek Strike and commanding the troops in Walsenburg and Ludlow, was concerned that the funeral might spur rioting in Trinidad and stationed his troops in anticipation of an operation to retake the town. Despite the arrival of Chase's reinforcements bringing the total militia in the southern coalfields to roughly 650, these troops were disallowed from entering Trinidad in accordance to the truce. By this point, Trinidad was thoroughly under control of the strikers and was serving as a central command hub for their armed contingents. At 7PM, with no reports of significant violence in Trinidad, Chase received word that perhaps hundreds of strikers were attacking the CF&I McNally mine near Walsenburg. Verdeckberg was ordered by Chase to take 60 men to Walsenburg to retake the town on the morning of the 29th. The National Guard and mine guards from the McNally, Walsen, and Robinson mines fought strikers in the Battle of Walsenburg for control of the town and the hogback which overlooked it. Two strikers were killed on the 28th, including one byfriendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while en ...

. Verdeckberg was ordered to hold the town until federal troops arrived then retire back. Several men of this detachment–Lieutenant Scott, Private Wilmouth, and Private Miller–were wounded by gunfire in the afternoon, while Walsenburg-native and medic

A medic is a person involved in medicine such as a medical doctor, medical student, paramedic or an emergency medical responder.

Among physicians in the UK, the term "medic" indicates someone who has followed a "medical" career path in postgra ...

Major Pliny Lester was killed tending to either Scott or Miller. At 5PM that day, an unarmed pro-union man on a motorcycle

A motorcycle (motorbike, bike, or trike (if three-wheeled)) is a two or three-wheeled motor vehicle Steering, steered by a Motorcycle handlebar, handlebar. Motorcycle design varies greatly to suit a range of different purposes: Long-distance ...

named Henry Llyod was killed by strikers in an incident of mistaken identity. This and other attacks by the strikers led some in Colorado, particularly outside of Denver, to remain opposed to the strikers, with local papers carrying editorials describing them as "bandit Greek element" supported by "yellow

Yellow is the color between green and orange on the spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a dominant wavelength of roughly 575585 nm. It is a primary color in subtractive color systems, used in painting or color printing. In th ...

" descriptions of "fictitious battles."

Battle of Forbes, 30 April

With Verdeckberg's force moved to Walsenburg and negotiations for disarmament once again underway, a group of 100 strikers moved from Trinidad in the night of 29 April, linking up with additional armed anti-militia forces to create a roughly 300-strong force. At 5AM on 30 April, they attacked the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company mine at Forbes, firing weapons into the company-aligned camp and setting buildings alight. The defenders were 18 non-union men who had with them an emplaced machine gun. Caught unprepared, the superintendent of Forbes used a phone to call for militia forces to be sent from Ludlow to relieve the outnumbered garrison. With Verdeckberg gone, Hamrock answered the call and relayed the superintendent's pleas to Ammons and Chase. Ammons and Chase refused to send militia, believing the Forbes assault afeint

Feint is a French term that entered English via the discipline of swordsmanship and fencing. Feints are maneuvers designed to distract or mislead, done by giving the impression that a certain maneuver will take place, while in fact another, or e ...

to further thin National Guard troops. Strikers were initially repulsed by machine gun fire, but the weapon quickly became jammed, encouraging the attackers to charge into the camp and set most of the structures alight. The attackers were accused of threatening to dynamite the mine entrance, as the unarmed men, women, and children took cover there. None in the cave were killed. The fighting had ceased by 10AM, only hours before federal troops began arriving in the region. In total, nine of the Forbes camp were killed, including four Japanese strikebreakers. At least three strikers were killed by returning fire, including two by the machine gun.

Conclusion of the "Ten Days War"

Part-owner John D. Rockefeller, Jr. refused President Wilson's offer of mediation, conditioned uponcollective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The ...

rights for the strikers, leading Wilson to exert pressure on Ammons and other elected officials in Colorado and threaten to deploy federal troops. The Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

meant that any deployment of an already reduced and largely deployed Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

would be a risky move. Earlier in April, the Tampico Affair

The Tampico Affair began as a minor incident involving U.S. Navy sailors and the Mexican Federal Army loyal to Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta. On April 9, 1914, nine sailors had come ashore to secure supplies and were detained by M ...

had raised tensions and on 22 April U.S. sailors fought the Mexican military at the Battle of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

. On 28 April, Wilson spoke with Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Lindley Garrison

Lindley Miller Garrison (November 28, 1864 – October 19, 1932) was an American lawyer from New Jersey who served as Secretary of War under U.S. President Woodrow Wilson between 1913 and 1916.

Biography

Early years

Lindley Miller Garrison ...

and ordered the Department of War War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

{{u ...

to begin moving units towards Colorado while preparing to federalize National Guard units. Wilson would invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807 the same day for the first time since 1894 and for only the ninth time since the law's enactment. A total of 1,590 enlisted soldiers and 61 officers of the Army would ultimately be deployed to Colorado. Garrison's stated goal for the federal troops was to "preserve ..an impartial attitude." Only after this intervention to disarm did the war end.

On 29 April, Lawson issued an order for remaining armed miners to stand down. On 2 May, a proclamation from Garrison was issued, stating that "all persons 'not in the military service of the United States'" were to disarm, although this statement was understood as only disarming the strikers, as Wilson had received assurances from Ammons that the militia was withdrawing and did not need to turn over their weapons. By the end of the Ten Days War, up to 54 people–including non-combatants–had been killed in the post-Ludlow violence.

Final months of the strike, May–December 1914

As federal troops poured into the striker region, President Wilson began drawing up his own plans for how to conclude the strike. President Wilson instructedSecretary of Labor

The United States Secretary of Labor is a member of the Cabinet of the United States, and as the head of the United States Department of Labor, controls the department, and enforces and suggests laws involving unions, the workplace, and all o ...

William B. Wilson to begin negotiations with the union and return with recommendations regarding terms to end the strike. Secretary Wilson worked with mining union heads from across the country to create a plan for concluding the strike; the President felt that federal troops could not be withdrawn until the strikers were back to work. President Wilson received the Secretary of Labor's recommendations several months later and, on 5 September 1914, sent a proposed agreement to the two sides. The agreement called for a three-year truce on the stipulation that both sides ceased acts of intimidation and that Colorado's state laws on mining were to be followed, along with contractual alterations.

The President's proposal was brought to a vote by a special convention of miners in Trinidad on 16 September which approved the agreement by a 10:1 margin. President Welborn of CF&I responded on 22 September, stating the company would agree to follow state law but dismissed the remainder of the proposals. Following this, negotiations again broke down. Another also unsuccessful effort by President Wilson to end the strike through diplomacy was launched in late November 1914, but by then the strike had begun to falter.

The strike continued until the union ran out of funds in December 1914. With the strike's end, President Wilson contacted Ammons to determine if federal troops were still needed. Ammons requested the soldiers stay in the southern part of the state but, with no further developments by 1 January 1915, Wilson authorized their withdrawal, which was completed by 10 January. While Wilson succeeded in bringing order to the situation, he had demonstrated support for the labor union and the miners' unconditional surrender to the companies was thus seen as a defeat for Wilson.

Aftermath

Fatalities during the strike are generally assumed to be under-reported, as Las Animas County coroner's office reports more bodies related to the strike than appear in contemporary news reports. The office recorded 232 violent deaths from the beginning of 1910 to March 1913 with only 30 deaths resulting in a trial, which a later congressional committee would claim demonstrated a pattern of disinterest in recording fatalities associated with the mining companies. Government and private investigations have suggested that this policy of under-reporting deaths in deference to the mining interests continued during the strike's violence. Modern and contemporary estimates of fatalities vary widely, but following the Ludlow Colony's destruction an estimated 30 strikebreakers, National Guard soldiers, and mine guards were killed while a handful of pro-union fighters are reported to have died. Clara Ruth Mozzor–a social worker who would later become the first female Assistant Attorney General of Colorado–wrote for '' International Socialist Review'' in 1914 that "waste and ruin, death and misery were the harvest of this war that was waged on helpless people. Mothers with babies at their breasts and babies at their skirts and mothers with babies yet unborn were the targets of this modern warfare." Six mines and several company towns, including the abandoned Forbes, were damaged or destroyed. TheAssociated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

estimated the financial cost of the strike at $18 million (). CF&I lost $1.6 million with $5.6 million still on hand, while the UMWA spent $870,000. By 1915, CF&I mines had reached 70 percent of their pre-strike outputs. Pro-union publications lamented the failure to secure immediate significant structural change in the relationship between miners and the CF&I and criticized the Guard and militia's response and actions at Ludlow.

Major Patrick Hamrock and Lieutenant Karl Linderfelt were tried in separate court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

s from the rest of the National Guard and militia involved in the suppression of the strike, as they faced additional charges of assault with a deadly weapon

An assault is the act of committing physical harm or unwanted physical contact upon a person or, in some specific legal definitions, a threat or attempt to commit such an action. It is both a crime and a tort and, therefore, may result in cri ...

in relation to the deaths of strikers in custody at Ludlow, including Tikas. Hamrock was charged on 13 May 1914 with arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wate ...

, manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

, and murder, for all of which he plea

In legal terms, a plea is simply an answer to a claim made by someone in a criminal case under common law using the adversarial system. Colloquially, a plea has come to mean the assertion by a defendant at arraignment, or otherwise in response ...

ded not guilty. Linderfelt admitted to striking Tikas with his Springfield rifle

The term Springfield rifle may refer to any one of several types of small arms produced by the Springfield Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts, for the United States armed forces.

In modern usage, the term "Springfield rifle" most commonly refer ...

. The military court found Linderfelt guilty of the assault on Tikas, "but attach dno criminality" to his actions.

In the weeks following the federal intervention, the

In the weeks following the federal intervention, the district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a ...

of Las Animas County opted against trying any miners with murder for the attack on Forbes that occurred during Ten Days War unless "furnished with a list of the militiamen and mine guards who took part in the battle of Ludlow, with a view of prosecuting them on charges of murder and arson." In a Trinidad court, John Lawson was found guilty of murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the ...

ing Nimmo by Judge Granby Hillyer in 1915 and sentenced to life imprisonment. The UMWA maintained Lawson's innocence, and his conviction was overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court

The Colorado Supreme Court is the highest court in the U.S. state of Colorado. Located in Denver, the Court consists of a Chief Justice and six Associate Justices.

Powers and duties

Appellate jurisdiction

Discretionary appeals

The Court ...

in 1917. Of the 408 strikers charged with a crime–many with murder–there were four convictions. All four were overturned on technicalities. Four men charged in relation to Major Lester's death were acquitted following their trial being moved from Huerfano County to Castle Rock in Douglas County.

Rockefeller hired future Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A L ...

in June 1914 to help create a system by which miners could have internal representation within CF&I. Rockefeller also hired Ivy Lee, an early practitioner and pioneer of public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

, and met with Mother Jones. This saw Rockefeller and King taking a tour of the CF&I mining communities in September 1915, notably including the miners of Valdez, who had largely not participated in the strike. These efforts would evolve into the Colorado Industrial Plan, better known as the Rockefeller Plan and the archetype for employee representation plans, as well as the creation of a CF&I company union

A company or "yellow" union is a worker organization which is dominated or unduly influenced by an employer, and is therefore not an independent trade union. Company unions are contrary to international labour law (see ILO Convention 98, Article ...

. Through his connections with the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...