Cockpit-in-Court on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cockpit-in-Court (also known as the Royal Cockpit) was an early theatre in London, located at the

The Cockpit-in-Court (also known as the Royal Cockpit) was an early theatre in London, located at the

The Cockpit ceased to be used for cockfighting in Jacobean times, and was used instead as a private theatre and as chambers for members of the Royal Household. It was redesigned in 1629 for

The Cockpit ceased to be used for cockfighting in Jacobean times, and was used instead as a private theatre and as chambers for members of the Royal Household. It was redesigned in 1629 for  In 1680, it was occupied by

In 1680, it was occupied by

Shakespearean Playhouses

', by Joseph Quincy Adams Jr. from

Plan of Whitehall

from 1680, showing the location of the tennis courts, cockpit, tiltyard on the

The Cockpit-in-Court (also known as the Royal Cockpit) was an early theatre in London, located at the

The Cockpit-in-Court (also known as the Royal Cockpit) was an early theatre in London, located at the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. ...

, next to St. James's Park

St James's Park is a park in the City of Westminster, central London. It is at the southernmost tip of the St James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St James the Less. It is the most easterly of a near-continuous ch ...

, now the site of 70 Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

, in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

.

The structure was originally built by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, after he had acquired Cardinal Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling figur ...

's York Place to the north of the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

, following the Cardinal's downfall in 1529. It was one of a number of new pleasure buildings constructed for King Henry's entertainment, including a real tennis

Real tennis – one of several games sometimes called "the sport of kings" – is the original racquet sport from which the modern game of tennis (also called "lawn tennis") is derived. It is also known as court tennis in the United Sta ...

court, a bowling alley

A bowling alley (also known as a bowling center, bowling lounge, bowling arena, or historically bowling club) is a facility where the sport of bowling is played. It can be a dedicated facility or part of another, such as a clubhouse or dwelling ...

, and a tiltyard, and was used as an actual cockpit; that is, an area for staging cockfighting

A cockfight is a blood sport, held in a ring called a cockpit. The history of raising fowl for fighting goes back 6,000 years. The first documented use of the ''word'' gamecock, denoting use of the cock as to a "game", a sport, pastime or ente ...

. Thus enlarged, the Palace of Whitehall became the main London residence of the Tudor and Stuart Kings of England, and the Palace of Westminster was relegated to ceremonial and administrative purposes only.The Location - WhitehallMinistry of Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in state ...

.

The Cockpit ceased to be used for cockfighting in Jacobean times, and was used instead as a private theatre and as chambers for members of the Royal Household. It was redesigned in 1629 for

The Cockpit ceased to be used for cockfighting in Jacobean times, and was used instead as a private theatre and as chambers for members of the Royal Household. It was redesigned in 1629 for Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

by Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

as a private venue for staging court masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

s. It was the second cockpit that Jones had redesigned as a theatre, the other being the Cockpit Theatre in Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of Camden and the southern part in the City of Westminster.

Notable landmarks

T ...

, which was renovated after a fire in 1617.

After the London theatre closure of the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, the Cockpit returned to use under Charles II, and was refitted in 1662. A new dressing room

A changing-room, locker-room, (usually in a sports, theater, or staff context) or changeroom (regional use) is a room or area designated for changing one's clothes. Changing-rooms are provided in a semi-public situation to enable people to ch ...

was added for female players, whose presence onstage was a recent theatrical innovation; its walls were decorated with green baize, one possible origin of the theatrical term " green room" for a dressing room. Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

records attending several plays at the Cockpit in his diary.

In 1680, it was occupied by

In 1680, it was occupied by Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle

Christopher Monck, 2nd Duke of Albemarle (14 August 1653 – 6 October 1688) was an English soldier and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1667 to 1670 when he inherited the Dukedom and sat in the House of Lords.

Origins

Mon ...

in his official capacity as Master of the Great Wardrobe

The King's Wardrobe, together with the Chamber, made up the personal part of medieval English government known as the King's household. Originally the room where the king's clothes, armour, and treasure were stored, the term was expanded to des ...

, and later by Ralph, 1st Duke of Montagu in the same capacity.

Charles II gave the Cockpit to Princess Anne

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950), is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of ...

, daughter of Charles's brother James, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious ...

, in 1683. Anne and her closest friend, Sarah, Lady Churchill were imprisoned here during the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

; both their husbands, Prince George of Denmark

Prince George of Denmark ( da, Jørgen; 2 April 165328 October 1708) was the husband of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. He was the consort of the British monarch from Anne's accession on 8 March 1702 until his death in 1708.

The marriage of Geor ...

and John, Baron Churchill switched their allegiances from James II to William of Orange. Sarah and Anne escaped to Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

shortly afterwards. The Palace of Whitehall was almost completely destroyed by fire in 1698. One prominent structure to survive was the Banqueting House, also designed by Inigo in 1619; another, lesser, structure to survive, was the Cockpit. After the fire, William III moved his London residence to nearby St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Alt ...

, and the site was rebuilt to be used as government offices, and residential and commercial premises. The Cockpit was used to house government officials. It was first occupied by HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of Government of the United Kingdom, His Majesty's Government ...

, whose offices elsewhere in the palace had been destroyed, until the Treasury moved to a new building on Horse Guards Road

Horse Guards Road (or just Horse Guards) is a road in the City of Westminster, London. Located in post code SW1A 2HQ, it runs south from The Mall down to Birdcage Walk, roughly parallel with Whitehall and Parliament Street.

To the west o ...

in 1734.

When Anne became queen after the death of William in 1702, she gave the residence to her loyal friends John and Sarah, now Duke and Duchess of Marlborough. They vacated the residence during Anne's reign and it became the Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

. After the Treasury moved, it was used in the late 18th century by the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

, after that government office had been founded at Cleveland Row, St James's but before it moved to Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk f ...

. Next, it was used by the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

as a council chamber, for judicial purposes. It continued to be used by the Privy Council after a new chamber was built for them in 1827. The current building on the site, at 70 Whitehall, is used by the Cabinet Office

The Cabinet Office is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for supporting the prime minister and Cabinet. It is composed of various units that support Cabinet committees and which co-ordinate the delivery of government object ...

. The reconstructed Cockpit Passage in 70 Whitehall runs along the edge of the old tennis courts and into Kent's Treasury, built on the site of the original cockpit lodgings. The minstrel's gallery

A minstrels' gallery is a form of balcony, often inside the great hall of a castle or manor house, and used to allow musicians (originally minstrels) to perform, sometimes discreetly hidden from the guests below.

Notable examples

*A rare example ...

on the ground floor is currently decorated with pictures of fighting cocks and a model of the old Whitehall palace.

It should not be confused with Cockpit Steps nearby in St James Park, which lead up from Birdcage Walk

Birdcage Walk is a street in the City of Westminster in London. It runs east–west as a continuation of Great George Street, from the crossroads with Horse Guards Road and Storey's Gate, with the Treasury building and the Institution of Mech ...

past the site of a royal cockpit in Old Queen Street

Queen Anne’s Gate is a street in Westminster, London. Many of the buildings are Grade I listed, known for their Queen Anne architecture. Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner described the Gate’s early 18th century houses as “the best of the ...

.

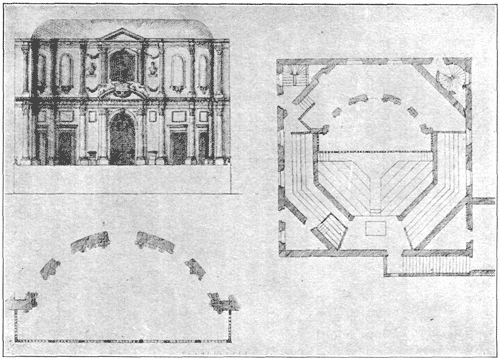

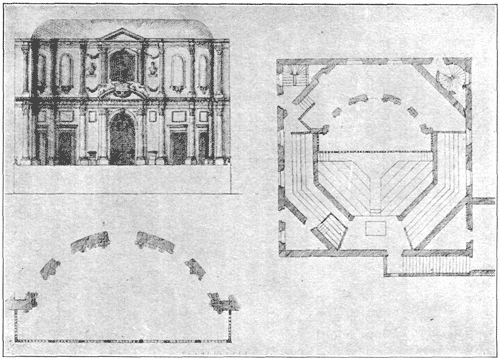

Reconstructions

A replica theatre based on Inigo Jones' 1629 plan of the Cockpit-in-Court is planned as part of theShakespeare North

The Shakespeare North Playhouse in Prescot, Merseyside, in the north of England is a cultural and educational venue that opened in 2022. The development includes a 420-seat main auditorium, a modern studio space, outdoor performance garden, exhib ...

complex in Prescot

Prescot is a town and civil parish within the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley in Merseyside, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, it lies about to the east of Liverpool city centre. At the 2001 Census, the c ...

, Merseyside. The historical Prescot Playhouse, the inspiration behind the project, existed between the mid-1590s and 1609. No plans of that theatre survive, however.

References

External links

*Shakespearean Playhouses

', by Joseph Quincy Adams Jr. from

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital libr ...

Plan of Whitehall

from 1680, showing the location of the tennis courts, cockpit, tiltyard on the

St. James's Park

St James's Park is a park in the City of Westminster, central London. It is at the southernmost tip of the St James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St James the Less. It is the most easterly of a near-continuous ch ...

side, and the configuration of buildings on the river side

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cockpit-In-Court

Buildings and structures completed in the 16th century

Buildings and structures completed in 1629

Former theatres in London

Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster

Theatres completed in 1629

16th-century architecture in England

1629 establishments in England

Henry VIII

Cockfighting

Inigo Jones buildings

Anne, Queen of Great Britain